Abstract

This study delves into the complex relationship between storytelling and historical understanding. Focused on how lower-secondary students employ narrative discourse in writing, it examines the extent to which their storytelling aids or limits historical comprehension. Drawing on systemic-functional linguistics and history education theories, the study highlights that while narratives might encourage personalized perspective-taking, thus potentially undermining objective historical analysis, they also reveal a more complex interplay between narrative form and historical insight than previously recognized. Through a comparative evaluation of student texts, it explores how certain types of narratives—descriptive, evocative, and emotive—interact with different foci of historical understanding. The analysis underscores the challenge of integrating broader historical analysis within personal narratives but also showcases successful examples of this integration. The article proposes strategies for educators to leverage storytelling more effectively, emphasizing the need for linguistic scaffolding to enhance students’ historical narratives.

Introduction

Imagine that you are a journalist at an evening newspaper with the great privilege of having a time machine at your disposal which you use to make news reports from history. Select an event from the text above [a text about Columbus’s voyage] and author a short report about it. Don’t forget the headline, as it will probably end up on the magazine’s running sheet. (Eriksson Citation2021)

This assignment – recommended by a history education online resource – engages students in imagining themselves as journalists with a time machine, tasked with reporting on historical events such as Columbus’ voyage. It provides one example of how educators leverage storytelling’s potential to, as noted by Bage (Citation2012), foster engagement with historical facts. Despite storytelling’s acknowledged value among practitioners (Hamer and Hoodless Citation1998; Hawkey Citation2004; Eliasson and Nordgren Citation2016; Stolare Citation2014), approaches like ‘the time machine assignment’ remain contentious. It has been argued that the nature of storytelling can detract from evidence-based comprehension of history (Endacott and Brooks Citation2018) and replace the interpretative processes of historical thinking with those of personal experiences (Wineburg and Martin Citation2004). While recognized for its motivational qualities (Colby Citation2008) and ability to promote intellectual reflection (Benmayor Citation2008), it has also faced criticism for fostering ‘an irresponsible and erroneous understanding of the past’ (Foster Citation1999, p. 19). In this section both sides of the argument are evaluated, setting the stage for the objective and methodology of the study presented in this paper.

A key argument for the use of student-crafted stories is that they foster emphatic response and historical perspective-taking (Garcia and Rossiter Citation2010). Skolnick et al. (Citation2004) highlighted storytelling integrated with students’ personal experiences and historical sources to develop ‘empathy, inclusion and community’ (p. 2). Echoing this position, Coleborne and Bliss (Citation2011) contended that story construction enhances students’ interest as it privileges ‘personal stories and emotion’ (p. 680). This potential for fostering affective connections is further explored in Endacott’s (Citation2010) study on eighth-grade students tasked with authoring first-person narratives from the perspective of historical characters. Although Endacott found that such exercises can facilitate historical perspective-taking, it also highlighted the challenge of overcoming ‘an egocentric approach’ (p. 32) to past events; a challenge mirrored in the findings of D’Adamo and Fallace (Citation2011). In their action research study, fourth-grade students – tasked with presenting historical perspectives through narratives – demonstrated increased awareness of the multiplicity of perspectives, but also difficulties in accurately interpreting them. Endacott and Brooks (Citation2018) suggested that the personalized perspective-taking encouraged by narrative-based instructional designs encourages presentism, defined by Wineburg (Citation1991) as historical interpretations that are unduly influenced by contemporary and personal viewpoints. In their critique, Endacott and Brooks cited earlier studies by Levstik (Citation1986) and VanSledright and Brophy (Citation1992). The latter, oft-cited study aimed to capture fourth graders’ ability to tell coherent stories about the past. It indicated that although beneficial for empathetic engagement, storytelling may result in limited and subjective interpretations due to a lack of contextual understanding.

Considering that writing from a specific historical perspective is a complex procedure, as highlighted by Christie and Derewianka (Citation2008), it is noteworthy how little attention the linguistic aspects of writing receive in educational discussions. Brooks (Citation2008) has touched on the complexity by examining how the narrative perspective impacts students’ writing and historical thinking. Her findings indicated that first-person writing tasks promote empathetic reasoning but may also encourage speculative personal interpretations. Conversely, third-person tasks tend to ensure adherence to factual accuracy but may not always engage students emotionally or experientially. Though not delving into language-related aspects, Endacott (Citation2010) recognized that varieties in students’ grasp of historical understanding ‘may be attributable to relative differences in the ability to express themselves through writing’ (p. 23). A recent study by Björk et al. (Citation2020) showcased a more pronounced focus on the language used to express historical understanding. Through linguistic analysis, they indicated that linguistic choices may affect conceptual organization. Earlier such investigations include the extensive analyses of school history discourse conducted from an SFL-informed genre-theory perspective (e.g. Coffin Citation2009; Christie and Derewianka Citation2008; Martin and Rose Citation2008). While these efforts provide valuable insights into the dynamics between linguistic form and historical understanding, the genre-based perspective tends to view narratives as only an initial ‘learning trajectory’ (Christie and Derewianka Citation2008, p. 212) step towards more complex genres – such as argumentative essays – deemed crucial for deeper historical insights.

The present study adopts a broader view of narratives but agrees with the idea – central to genre-based pedagogical approaches – that scaffolding is required for students to overcome linguistic hurdles and adequately convey their grasp of history. Through an analysis focused on both language and content within student narratives, the study aims to identify linguistic aspects of historical narratives, and how these can potentially affect historical thinking. Conducted in a secondary school setting, the study addresses the research question: What is the relationship between students’ historical fiction and their displayed historical understanding? The investigation lays the groundwork for an ensuing discussion on the instructional implications these aspects entail.

Historical understanding and the language of narratives

This section outlines a theoretical framework that combines theories about students’ historical understanding (Barton and Levstik Citation2004) with linguistic theories (Martin and White Citation2005; Halliday & Matthiessen).

Historical stance orientations

In the study, historical understanding is seen as the adoption of specific historical stance orientations, reflecting the types of understanding expected in educational settings. These stance orientations draw on Barton and Levstik (Citation2004) framework, which outlines four primary stances students may adopt towards the past. Barton and Levstik acknowledge that these stances can have either an individual orientation, primarily concerned with individual or local contexts, or a public orientation that emphasizes broader political, economic, and collective issues.

Identification: This stance reflects students’ ability associate themselves with the past. Its individual orientation focuses on historic persons, while the public orientation indicates an identification with collectives.

Analytical: This involves examination of historical events, specifically their causes and consequences. While the individual orientation focuses on individuals’ motives, the public orientation delves into structural factors.

Moral Response: Represents ethical or emotional reactions to historical occurrences. With an individual orientation, it might manifest as objections to individuals’ behavior, whereas with a public orientation, it addresses broader social injustices.

Exhibition of knowledge

Concerns demonstration of factual knowledge, either concerned with specific details, or with the significance of these details for contemporary contexts.

Furthermore, the study posits that students’ historical understanding is realized linguistically, aligning with the principles of systemic-functional linguistics (SFL). SFL views language as a system of lexicogrammar resources, which speakers or writers strategically select and organize according to their situational context (Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2014). This organization involves three metafunctions: the ideational (representing experiences), the interpersonal (negotiating interactions and positionings), and the textual (organizing texts cohesively). To trace the ideational metafunction, Halliday and Matthiessen highlight lexicogrammatical categories such as processes (what happens), participants (actors involved), and circumstances (contextual features). For the interpersonal metafunction, Martin and White (Citation2005) have introduced the appraisal framework, detailing how evaluative language works through networked systems like Attitude (expressing emotions and appreciation), Graduation (moderating their intensity), and Evaluation (managing authorial stance). The application of these categories is detailed in the subsequent section.

Methods

This section describes the procedures for data generation and analysis.

Context of study, data generation, and ethical considerations

This study sourced data from a case study (Kindenberg Citation2021) on genre pedagogy in history instruction at a linguistically diverse, socially disadvantaged secondary school outside Stockholm (Sweden). The case study documented a five-week instructional unit on early European colonialism (15th to 17th century C.E.) taught three times a week in three classes to a total of 48 eighth-grade students (14 years of age), by a teacher experienced in history and Swedish as a Second Language instruction. The classes primarily consisted of students who spoke Swedish as an additional language. In urban areas in Sweden, this type of educational setting is common. It is also common that teachers in these contexts incorporate models for language-focused content-area instruction, as this teacher opted for. In addition to conventional methods for content delivery, instruction was inspired by genre pedagogy following Gibbons (Citation2016).

As described by Gibbons, genre pedagogy emphasizes explicit teaching of typical school genres (e.g. narrative, explanatory, and argumentative texts), coupled with scaffolding techniques like joint analysis and co-construction of genre-typical texts. This approach was adapted by the teacher to include novel elements, such as allowing individual choice of examination format for writing, rather than the whole class working towards a ‘target genre’. Students had three format options – ‘interview’, ‘voyage journal’, and ‘argumentative text’ – which the teacher permitted students to blend and modify. In its data generation, the investigation prioritized texts showcasing storytelling characterized by a narrator (either in first or third person) sequentially relating events involving historical or fictional characters. Since some students – as encouraged by the teacher – modified the chosen writing format, the selection of texts included, but was not restricted to, those in the ‘voyage journal’ format. Out of 41 submitted texts, seven were analyzed (shown in ).

Table 1. Texts examined.

Prior to the investigation, students had given informed consent to participation, in accordance with the Swedish Research Council’s (Citation2017) ethical research conduct guidelines, including participant de-identification. The project did not require formal ethical review, as it did not involve sensitive personal data, in line with departmental procedures at the study’s inception.

Analytical procedure

The examination of how narrative and historical understanding interact unfolded in four steps. The first step involved content analysis to pinpoint various forms of historical understanding within the texts. Next, a linguistic analysis was conducted on the narratives. The third step aimed to identify relationships between linguistic features and historical understanding. Lastly, the texts were revisited for a comprehensive, comparative evaluation. The steps are detailed below.

Step 1: Historical understanding

The point of departure for the first step of the analysis was Barton and Levstik (Citation2004) framework for historical stances, classified by either an individual or a public orientation. In , which exemplifies the operationalization of these stance orientations, individual orientations are denoted as ‘1’, and public as ‘2’.

Table 2. Historical stance orientations.

The exploration entailed deductive coding of each sentence in the text for stance orientations (such as I1, I2, E1, E2), a preliminary examination that uncovered patterns of recurrent stance combinations.

Step 2: Examining the narratives

Step 2 examined the language used in the narratives, concentrating on passages central to the ‘story’. Segments with factual observations not integrated with the story – e.g. ‘The ocean is still today called Mare Pacifico’ – were not included in the linguistic analysis. Given the study’s focus on a distinct situational context – storytelling in history education – the analysis applied a tailored selection of the extensive linguistic-categories repertoire offered by Halliday and Matthiessen (Citation2014) and Martin and White (Citation2005). The selection was focused on categories with relevance to storytelling’s goal, as defined by Rothery and Stenglin (Citation1997) and Martin and Rose Citation2008), that is, to capture interest by rendering events tangible (the ideational metafunction of narrative language) and engaging (its interpersonal metafunction).

To assess the tangibility of descriptions five lexicogrammatical categories were applied: concrete participants, mental processes, verbal processes, material processes, and specific circumstances (see Kindenberg Citation2022 for a precedent application of the methodology). Concrete participants differentiated ‘personalized’ depictions of individual characters (e.g. ‘Magellan’ or a first-person narrator) from generalized groups (e.g. ‘European explorers’). Mental processes captured how narratives portrayed characters’ thoughts and emotions (e.g. use of verbs like ‘thought’, ‘feared’). Along with verbal processes reflecting utterances, mental processes provide insights into characters’ emotions and opinions. Material processes highlight tangible actions within the story (e.g. ‘sailed’, ‘fought’) while specific circumstances anchor the story in time and place (e.g. ‘an early morning on October 12, 1492’), ensuring the events feel immediate and relatable.

To examine how the narratives engaged readers emotionally, the use of evaluative language was analyzed through the appraisal framework (Martin and White Citation2005), specifically its Attitude and Affect systems. The Affect system identified instances where visceral descriptions were employed to elicit a physical reaction from readers, such as the statement ‘Magellan was killed with a spear.’ Additionally, the Attitude system pinpointed language that appeals to emotions by portraying characters negatively (e.g. through descriptions of cruelty) or favorably (e.g. by highlighting bravery or resourcefulness).

Mirroring the approach used to analyze historical understanding, the texts underwent an initial, deductive coding, based on the selected categories. This revealed recurrent patterns in how these categories coincided, which lead to the identification of three distinct narrative emphases in event portrayal:

Descriptive: Characterized by the simultaneous presence of concrete participants, material processes, and specific circumstances. It represents a basic and ‘neutral’ stylistic approach.

Evocative: Identified by the co-occurrence of material, mental, and verbal processes occasionally paired with evaluative language in the Affect system, this configuration reflects thoughts and emotional experiences of characters, offering deeper insights into their internal states.

Emotive: Designed to directly engage readers and foster affective responses, identified as a consistent presence of evaluative language.

Step 3: Assessing relationships between narrative and historical understanding

Building on the preceding phases, the third step cross-compared text passages to discern co-variations between narrative emphases and historical stance orientations. A ‘passage’ was identified as text segments with coherent use of a specific narrative emphases. Co-variations between narrative emphases and historical understanding were termed narrative/historical-understanding relationships. An excerpt from the data – ‘He [Magellan] sailed across the Atlantic towards South America, from there he followed the coast south trying to find a passage to the Pacific Ocean’ – is used here to illustrate the applied procedure. Linguistically, the sentence showcases a combination of material processes (‘sail’ and ‘find’), specific circumstances (‘across the Atlantic towards South America’), and concrete participants (‘he’), which corresponds to a descriptive emphasis. In terms of historical understanding, it is focused on factual presentation, indicative of the Exhibition of Knowledge stance with an individual orientation that does not extend to contemporary significance. Hence, the sentence signals a relationship between descriptive language and factual presentation. The relationships identified in students’ texts are presented initially in the ensuing Findings section.

Step 4: Comparative evaluation of texts

From the initial review (Step 1) emerged notable differences between texts. For example, some texts followed a linear narrative while others featured a bifurcated structure that blended the narrative with additional commentary. This variance was not adequately captured in the fine-grained linguistic analyses that focused on the ideational and interpersonal metafunctions of text segments. The final step of the analysis aimed at a more comprehensive evaluation of differences in whole-text organization, recognizing that narratives should be seen as coherent entities – encompassing a beginning, middle, and end – rather than as a collection of fragmented sentences. The goal was to assess and compare prominent alignments with historical interpretation in each text, along with their narrative extent and coherence, or ‘story-likeness’.

Due to the lack of a standardized, quantifiable method for evaluating a text’s narrative nature, the percentage of linguistic categories coded in each text was calculated, as well as these percentages’ median value. Each text was then ranked, with the totaled median value of the texts serving as a benchmark to gauge their relative narrative degree, or ‘story-likeness’ (refer to Appendix A for details). Further inductive analysis identified differences in text length, narrative perspective, use of stylistic devices, text organization, and other features not focused on in the previous steps of the analysis. Specifically, the analysis highlighted ‘extra narrative’ commentary sections – viewed as additions to the narrative – and their relevance to the examination of relationships between the narrative and its demonstrated historical understanding. The result of this comparative evaluation is detailed concludingly in the ensuing Findings section.

Findings

In this section, salient relationships between narrative emphases and historical stance orientations are presented.

Narrative/historical-understanding relationships

For convenience in presenting the relationships, the somewhat bulky names of the analytical categories (‘historical stance orientations with either public or individual orientation’) have been translated into labels: Factual presentation denotes a form of historical understanding primarily concerned with individual orientations of the Exhibition of knowledge stance. Agent-centered explanations are identified with the Analytical stance with individual orientation, while structural explanations represent adoptions of that stance with a focus on broader factors or collectives. Historical Empathy indicate the Moral response stances with an individual orientation, while Critique represents public orientations of this stance. This focus emphasizes understanding historical figures on a personal level, fostering emotional reactions that range from condemnation to endorsement. The Identification stance orientations tended to co-occur with either explanations or moral responses and have therefore been treated in conjunction with these orientations, as shown in the ensuing sections.

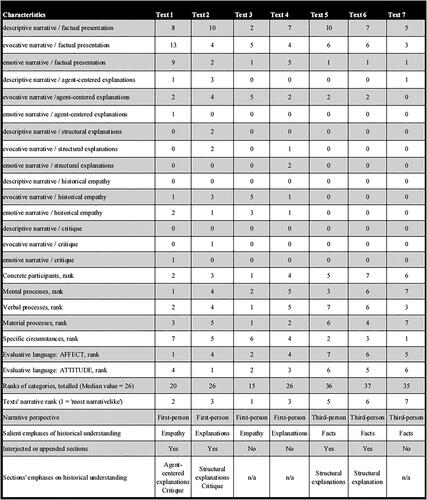

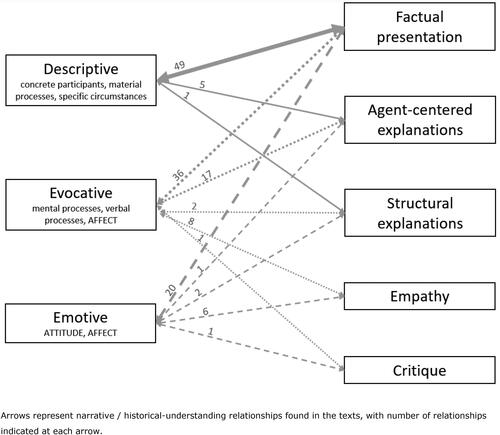

shows the identified narrative/historical understanding relationships. The numbers and arrow-width provide a broad estimate of the salience of each relationship. Evocative and emotive narrative emphases were linked to all highlighted orientations, whereas descriptive ones were more closely tied to presentation of facts.

Figure 1. Identified relationships between narrative emphases and historical understanding.

Arrows represent narrative/historical-understanding relationships found in the texts, with number of relationships indicated at each arrow.

The ensuing sections detail how these relationships manifested in various text segments. Most relationships were concerned with – but not limited to – factual presentation. Text segments that adopted public stance orientations (structural explanations and critique) exhibited fewer relationships, indicating the challenge of conveying this type of understanding in narratives. However, many texts included commentary segments. The impact of these segments, along with other textual characteristics, are compared and evaluated in the concluding section of this presentation. In all excerpts in the following sections, lexicogrammatical and evaluative language categories are highlighted in bold while historical stance orientations are underlined.

Narratives for factual presentation

The factual presentation – emphasizing historical knowledge and individual experiences – was associated with an array of narrative emphases. These Descriptive-narrative/Factual-presentation relationships conveyed information about individuals, locations, and dates, as illustrated in an excerpt from Text 5:

In November 1520 [specific circumstance] … Magellan [concrete participant] sailed [material process] to ‘the Pacific Ocean’ [specific circumstance] and there [specific circumstance] he [concrete participant] sailed for months [specific circumstance].

Instances of Emotive-narrative/Factual-presentation relationships, further enlivening the depictions, were also discerned in the analysis, as exemplified in this excerpt from Text 2, where narrator Juan refers to experiences onboard Columbus ship:

I took a deep breath and tasted the salty sea breeze. My mouth was dry and my body was all weak. I felt like I was about to die.

Narrative for historical empathy

Historical empathy is concerned with condemnation or appreciation of historical characters through the eyes of people in the past. In the examined texts, this focus was not achieved through descriptive narrative emphasis. Conversely, the empathy focus was frequently related to evocative narrative emphases, such as in this example: ‘The sailors were becoming sulky and wanted to go back. They believed Magellan was lying’ (Text 5). Here, processes highlight the sailors’ thoughts and desires to convey distrust for historic individual Magellan. In the following excerpt from Text 1, this evocative narrative/historical empathy relationship is further illustrated in a scene depicting Atahualpa’s encounter with a Bible:

I lifted the book and began to open it. Was this some kind of joke? Nothing happened? Was this their power and how would that make me change my mind? I heard no voice coming from the book.

The following excerpt from Text 3 illustrates how an emotive narrative pictures a vivid scene:

The morning after our guests [the Spanish Conquistadors] had arrived, I heard screams, a scream of fear and pain. I run towards where the scream came from. I arrived at Happy’s house. I run onto the floor. I see a lot of blood on the floor. It’s a big pool and I realize it’s from her left foot. Then I realize her toes have been severed. I run to her and asks her what happened – ‘The newcomers [the Conquistadors]’, she replies.

Narratives for critique

Critique, distinguished from historical empathy by being oriented towards political rather than localized contexts, requires that the narrative transcends the narrative’s individual focus in a pronounced manner. Only one instance was found, which showcased an evocative narrative/critique relationship:

The inhabitants presented Columbus with a golden mask, then he was finally convinced that he had arrived at the gold-rich lands he sought. The encounter between Europeans and natives was peaceful and harmonious.

Narratives for agent-centred explanations

All types of narrative emphases were linked to agent-centred explanations in students’ texts. A passage from Text 7 exemplifies a descriptive approach ‘In 1518, the Spanish king gave Magellan five ships and 270 men to find new trade routed’. The economic motivations are presented in a neutral manner. In contrast, narratives which incorporated not only actions and circumstantial details but also utterances and thoughts offered explanations in a more evocative manner, as illustrated in the following excerpt:

‘Magellan asked the Portuguese king Manuel for a boat, money, and pirates to go around the world. Manuel and his advisers did not want to support him because they did not believe that the earth is round (Text 6)’

Emotive narrative also served to further agent-centered explanations, as illustrated in the following excerpt from Text 4, where narrator Juan, crew member on Magellan’s voyage, observes factors influencing trade:

These spices were incredibly hard to find and now that we’ve found them, joy spreads throughout my body. Magellan had had some help from da Gama and Columbus, that’s why he could trade with so many people, but not so at the Spice Islands.

Narratives for structural explanations

Structural explanations concentrate on social and political factors. The following excerpt from Text 2 illustrates a descriptive narrative/structural explanation relationship:

[Columbus] sought money from Portugal and Spain. Spain gave Columbus support (money, boat, etc.) and he was then able toconquer riches but eventually conquer lands in Spain’s name.

What we did not know, as we fought our way out into the Pacific, was that many hundreds of European ships, many decades later, would follow in our footsteps, loaded with trade goods.

Comparative evaluation of texts

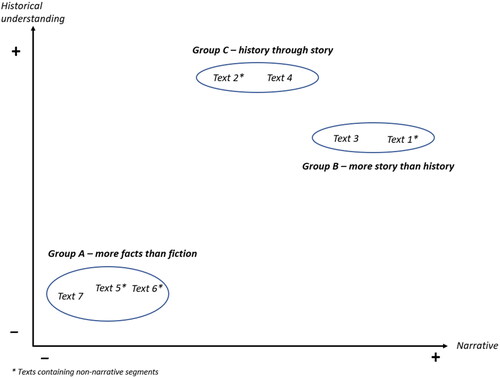

This section compares and discusses the examined texts, focusing on their overall structure, narrative techniques, and emphasis in historical understanding. The evaluation further considers the impact of extra-narrative text segments on the demonstration of historical understanding. visualizes salient differences between Texts 1-7 by plotting them in a bi-dimensional diagram.

Figure 2. Texts grouped by range of narrative execution and historical understanding.

While the x-axis in indicates the degree to which narrative resources were employed in the texts (i.e. their ‘storylike-ness’; see Appendix A for details), the y-axis indicates their demonstrated breadth and depth, reflective of the range of historical stance orientations in the texts. The clustered texts (Groups A, B, and C; descriptively labeled in the figure) do not represent a mathematically exact placement. Instead, it attempts to indicate how different degree of narrative correlated with historical understanding.

Group a texts: More facts than fiction

Group A texts 5–7, all chronicled Magellan’s expedition and shared several other characteristics as well: they were relatively short in length, utilized a third-person narrative perspective to summarize and recount events, with sparse employment of stylistic elements. In terms of narrative/historical understanding relationships, there was a robust presence of descriptive – and occasionally evocative – narrative emphasis coupled with a focus on either factual presentation, or the occasional demonstration of empathy concerned with the hardships endured by the crew. In other words, these narratives’ focus was on facts rather than fiction. While the texts primarily aimed to report facts, the authors’ intent to craft narratives was apparent. For instance, Text 6 commenced with a traditional storytelling introduction – ‘Once upon a time there was a boy named Magellan’ – and organized the narrative into chapters. Moreover, all texts incorporated detailed accounts of the hardships faced during Magellan’s expedition, such as the note in Text 7, that ‘the crew had to eat rats’. Hence, the employment of emotive narrative emphasis occasionally enhanced the demonstration of factual knowledge. The relationship to explanations remained subdued and centered on individuals. For example, a passage in Text 6, ‘[Magellan] wanted to find a new and better way to trade goods and so in 1514 he went and asked the king for ships’, alludes to, but does not elaborate on, complex trade routes as a motivation for colonialism.

The texts did not delve into more profound, structural explanations nor into evaluations of the characters, events, or contexts they portrayed. However, the narratives were occasionally disrupted by authorial interjections, such as the comment in Text 6 that ‘Magellan became the first person to pass all meridians’. Such remarks were crucial as they enabled the authors to demonstrate historical knowledge beyond factual presentation. For instance, in Text 5, the inclusion of a section titled ‘My opinion’ – where the author reflects on Magellan’s contributions to expanding human knowledge – exemplifies how events descriptively portrayed in the narrative could be subjected to historical interpretation.

Group B: More story than history

Texts 1 and 3 – both re-imagining the Spanish Conquistadors’ invasion of the Inca Empire – presented stylistically sophisticated narratives structured around ‘scenes’ such as the arrival of the Conquistadors, the capture of Atahualpa, his death sentence, and so forth. Text 1 adopted the perspective of Inca Emperor Atahualpa, portrayed in a modern interview format by a talk show host. Text 3, conversely, offered the viewpoint of ‘Pagie’, a young female Inca resident. Utilizing both figurative and affective language, these texts were marked by a robust prevalence of evocative or emotive narrative emphases. These were paired with a broad spectrum of stance orientations, though with an emphasis on Historical empathy. Particularly in Text 3, the alternation between evocative and emotive emphases accentuated the brutality enacted by the Conquistadors, as demonstrated when the narrative recounts the maiming of Pagie’s friend Happy (shown in the previous section), leading Pagie to react with tears, panic, and curses. This narrative’s focus on youthful characters with contemporary names suggests a personalized connection to historical events. While the story about young Pagie was indeed dramatic and engaging, it was also ‘more story than history’ with relatively few connections to facts and explanations.

Incorporation of explanations into narratives poses challenges for authors, requiring a depth of knowledge and sometimes hindsight that may not be readily available to a character like young Pagie. In Text 3, this challenge was occasionally met, such as when Pagie overhears utterances by (presumably more knowledgeable) Inca residents attributing the rapid conquest by the Spanish soldiers to their superior strength, thereby incorporating an explanation within the narrative. However, Pagie’s personalized perspective provided the author with limited opportunities for structural explanations addressing broader political contexts.

The author of Text 1 took a different – potentially productive – approach by interspersing ‘interviewee’ Atahualpa’s story with comments from ‘history expert’ Mike Byers. Unlike Atahualpa’s emotionally charged narrative, Byers’ comments maintained a formal tone, reflective of his expert status. For example, Byers clarified the motivations behind Pizarro’s decision to send forth a Catholic priest to meet Atahualpa: ‘Pizarro wanted Atahualpa to convert to Catholicism/…/But the real reason for attacking was that they wanted Atahualpa’s riches, being gold, silver, and money.’ In this way, Byers recast Atahualpa’s narrative to provide broader context. Through these interjected remarks, ‘extra-narrative relationships’ were established, linking the Atahualpa’s personal narrative to structural explanations and broad critique. For instance, one of Byers’ comments framed the Spanish treatment of the Incas as contrary to contemporary principles of universal rights. Nevertheless, this innovative technique of incorporating commentary was not fully employed, as Byers’ contributions often reiterated Atahualpa’s account without significantly deepening the historical interpretation of events. The result of this lack of contextualization was that Atahualpa’s account, similar to that of Pagie, remained more story than exploration of history.

Group C: History through story

In Group C, Texts 2 and 4, had fewer stylistic devices compared to Group B but featured well-constructed narratives detailing Columbus’ and Magellan’s voyages respectively, settings While the narratives were occasionally marked by brief summaries of events – particularly towards the end of the journeys they portrayed – the texts were predominantly organized into scenes that included dialogues and described settings. The authors utilized first-perspective narration, which made the event portrayal both accessible and relatable without being excessive personalization. Specifically, the first-person account enabled descriptive language – otherwise predominantly associated with factual orientation – to be linked to explanations. For instance, in Text 2, Sebastian – a sailor on Columbus’ ship – reflected on the limitations of contemporary shipbuilding and how these exacerbated the hazards of exploration. Nevertheless, first-person narratives, as previously noted, present challenges due to the narrator’s limited awareness of broader historical contexts. Text 2 overcame this hurdle through narrator Sebastian revisiting his experiences of Columbus’ expedition three decades later, blending his account with insights into the motivations and outcomes of European colonial ventures. This technique enabled various relationships between narrative and explanation. For example, Sebastian passingly observed that ‘ships in those days were often small’ to illustrate the dangers Columbus faced, integrating narrative and explanation. Text 4’s narrator. Manuel, lacked hindsight, yet the author (as demonstrated in the preceding section) effectively used Manuel’s internal monologues to delve into historical backgrounds and structural explanations.

In addition to its retrospective narration, Text 2 included a concluding section at the end, titled ‘Personal comment’, which enabled authorial observations beyond Sebastian’s knowledge, as illustrated in this excerpt:

Columbus was thus an intelligent man who was seen as a hero when he came back/…/But 95% of the natives died because they had either been infected by the Europeans or shot.

Through the employment of various narrative configurations, scene descriptions, and the adoption of first-person perspective, these narratives effectively interpreted history through crafting immersive stories; stories that managed to maintain a critical distance to the events they portrayed. presents a summary of the evaluative comparison of texts detailed in this section. Appendix A provides details for the quantitative estimation of narrative degree, found in the ‘Narrative rank’ column in .

Table 3. Summary of the comparative evaluation of texts.

Discussion

This investigation has explored the linguistic intersection of narrative execution and historical comprehension in texts written by students. While previous research has acknowledged the intersection as complex and potentially troublesome (Endacott and Brooks Citation2018), the current study highlights that not all facets of this complexity are necessarily problematic. The study also questions the claims of genre-based theories suggesting that narratives, as a genre, hinder historical explanations and analyses. Importantly, despite their complexities, the study suggests that narratives can effectively foster engagement with historical content, as noted by Skolnick et al. (Citation2004), among others. Though students’ experiences of writing were not directly observed, the narratives – especially those characterized by evocative and emotive language – reflected a sense of eagerness among the authors to explore historical events. This resonates with previous demonstrations of how storytelling can prompt students to engage with historical facts (Bage Citation2012) and spark interest in past occurrences (Coleborne and Bliss Citation2011). Nevertheless, the investigation acknowledges the risk that the intrinsic human aspect of storytelling (Gottschall Citation2012), might encourage overly personalized interpretations of historical events, as noted by VanSledright and Brophy (Citation1992). While this study recognizes rather than resolves the dichotomy between personal engagement and personalized interpretations, it does proceed to discuss educational strategies for addressing the tension, focusing particularly on the linguistic scaffolding required.

Texts 5–7 exhibited a notable lack of stylistic devices, alongside a restricted engagement with historical interpretations beyond factual knowledge. This association between sparse, descriptive language, third-person perspective, and fact recounting aligns with Brook’s (Citation2008) observation that such narratives favor factual presentations, sometimes at the expense of emotional involvement with historical events. The present investigation’s fine-grained analysis expands on Brook’s observation by pinpointing linguistic aspects within these narratives that could benefit from targeted instructional support. Conversely, the links found in Texts 1–4 between historical explanations and language that reflects characters’ utterances and emotional experiences suggest the importance of encouraging dialogue, inner monologues, evaluative language, and other strategies to incorporate thoughts and feelings. Moreover, the use of first-person perspective ensured these narratives conveyed a sense of immediacy and proximity to events, whether the emphasis was on descriptive, evocative, or emotive narrative expression. Notably, organizing narratives into distinct ‘scenes’ seemed to allow for the use of stylistically ‘neutral’ event descriptions that set the stage for subsequent analysis and critique of events.

Consequently, educators are encouraged to introduce and support a broad spectrum of narrative techniques, stylistic devices, and organizational strategies in text creation. Adopting SFL-informed genre-based approaches provides tools for structured support through metalanguage for text analysis and co-construction (Christie and Derewianka Citation2008). Ideally, this support should present specific guidelines, such as mandating a minimum number of dialogues or inner monologues or provide vocabulary lists that highlight expressive and cognitive verbs as well as language for establishing and picturing scenes. Such support systems, which are advocated for in content-based instruction frameworks (Grabe and Stoller Citation1997), are crucial.

Considerable effort should be invested in proper task design, as this type of pre-planned scaffolding influences the finer points of scaffolding that occur during classroom interactions as students engage with the task (Walqui Citation2006). Persaud (Citation2019) underscores the value of reflexively questioning personal narratives to give them public validity through activities that juxtaposes insider and outsider perspectives. As a rule, scaffolding should aim to highlight – and facilitate the integration of – such ‘narrative insider’ and ‘analytical outsider’ perspectives. The stage for a reflexive integration can be set in task design – and subsequent instruction – that combines linguistic aspects with features that facilitate the expression of expected historical understanding. The latter might include mandating students to include certain characters, authentic persons of figures otherwise emblematic of the significance of the historical period, with whom the characters of their story should interact to enrich the narrative’s historical context.

This recommendation stems from data observations indicating that first-person narratives, coupled with a broad range of narrative emphases (descriptive, evocative, emotive), enhanced deeper historical understanding. The use of first-person viewpoints, particularly evident in Texts 1–4, correlated with a more pronounced connection between characters’ internal states, as well as with historical explanations and empathy. Yet, this tentative recommendation to adopt a first-person perspective invites consideration, as such viewpoints are also prone to biased perspective-taking (VanSledright and Brophy Citation1992). For instance, Text 3’s narrative, influenced by the author’s emotional bond to the protagonist, prioritized emotional engagement over a broader contextualization of historical events. To mitigate such bias, assignments could promote critical engagement, requiring dialogue that critiques the wider political motivations of historical figures. For example, a reimagined assignment of the type initiating this article – where a reporter is sent back in time to interview Columbus about his voyage – could prompt students to confront him with long-term outcomes of his expeditions and solicit his response. Engaging with conflicting historical perspectives is key to developing historical empathy through writing (Endacott and Brooks Citation2018). Prior research further highlights the effectiveness of furnishing students with targeted questions to enhance historical reasoning and perspective-taking (Kohlmeier Citation2006; Cunningham Citation2007), suggesting that such the writing task should encourage first-person narratives to address such questions.

Since employment of a first-person perspective in historical narratives effectively enhances the immediacy of events (Conroy et al. Citation2022), the technique should not be hastily dismissed despite concerns, voiced by Brooks (Citation2008) among others, that it favors presentism. However, the varied success among students in balancing first-person narration with analytical depth highlights the need for teacher guidance. This guidance should cover linguistic aspects that help bridge personal experiences with structural explanations. For instance, the use in Text 2 of collective pronoun ‘we’ and indications of thoughts permitted the author to connect the narrator’s specific situation with broader collective experiences. Similarly, the inner monologues in Text 4 enabled reflections on the political landscape of the time. Though these devices were sometimes employed incidentally, they represent valuable techniques that teachers should encourage students to explore. It is further advisable to clarify the limitations of first-person narratives, ideally, through task design that present alternative narrative structures to the linear beginning-middle-end format. Such approaches not only broaden students’ narrative skills but also enhance their ability to convey historical complexities effectively.

The study proposes several alternatives for text organization. For instance, incorporating reflective comments or asides can underscore the narrative’s broader significance. While the lack of seamless integration of such commentary segments within the examined texts suggests a challenge, Text 2’s retrospective narration offered a technique for expanding the narrative’s scope beyond immediate events and incorporate long-term consequences of Columbus’ expeditions. Another technique was highlighted in Text 1, where ‘expert commentator’ Mike Byers provided additional explanations to Atahualpa’s personal account. Such examples underscore the importance of extra-narrative commentary, ideally seamlessly integrated with the narrative, to enable contrasts between insider and outsider perspectives, as described by Persaud (Citation2019). However, in this example, the limited engagement of Byers’ comments with structural or critical analysis underlines the importance that narrative writing assignments clearly communicate expectations regarding both conceptual understanding and linguistic form.

In summary, the study sheds light on the complexity of employing narratives in history education, including the concern that the eyewitness’s account co-opts the analytical gaze. To address such concerns, it has suggested some guidelines for deliberate scaffolding of narrative writing tasks, where history educators’ content knowledge is coupled with linguistic awareness. While the research’s exploratory nature and initial application of its analytical framework, combined with a relatively small sample size, warrant caution in generalization, the study’s novel cross-disciplinary approach contributes to discourse on the dynamics between narrative form and historical understanding. The study advocates for further empirical research in history classrooms to develop design principles for writing tasks that encourage narratives to go beyond mere recount of events to broader historical analyses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bage G. 2012. Narrative matters: teaching history through story. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Barton KC, Levstik LS. 2004. Teaching history for the common good. New York: Routledge.

- Benmayor R. 2008. Digital storytelling as a signature pedagogy for the new humanities. Arts Humanit High Educ. 7(2):188–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022208088648.

- Björk O, Nolgård O, Nygren T. 2020. Barn skriver historia: en studie av fjärdeklassares skrivande i historieämnet. Nord: J Humanit Soc Sci Educ. 2:73–106.

- Brooks S. 2008. Displaying historical empathy: What impact can a writing assignment have? Soc Stud Res Pract. 3(2):130–146. https://doi.org/10.1108/SSRP-02-2008-B0008.

- Christie F, Derewianka B. 2008. School discourse: learning to write across the years of schooling. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Coffin C. 2009. Historical discourse: the language of time, cause and evaluation. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Colby SR. 2008. Energizing the history classroom: historical narrative inquiry and historical empathy. Soc Stud Res Pract. 3(3):60–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/SSRP-03-2008-B0005.

- Coleborne C, Bliss E. 2011. Emotions, digital tools and public histories: digital storytelling using windows movie maker in the history tertiary classroom. Hist Compass. 9(9):674–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2011.00797.x.

- Conroy T, Grochowicz J, Sanders C. 2022. Interpreting history through fiction: three writers discuss their methods. Public Hist Rev. 29:195–206. https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v29i0.8241.

- Cunningham DL. 2007. Understanding pedagogical reasoning in history teaching through the case of cultivating historical empathy. Theory Res Soc Educ. 35(4):592–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2007.10473352.

- D’Adamo L, Fallace T. 2011. The multigenre research project: an approach to developing historical empathy. Soc Stud Res Pract. 6(1):75–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/SSRP-01-2011-B0005.

- Eliasson P, Nordgren K. 2016. Vilka är förutsättningarna i svensk grundskola för en interkulturell historieundervisning? Nord: J Humanit Soc Sci Educ. 6(2):47–68.

- Endacott JL, Brooks S. 2018. Historical empathy: perspectives and responding to the past. In: Metzger SA & Harris LM, editors. The Wiley International Handbook of history teaching and learning. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; p. 203–225.

- Endacott JL. 2010. Reconsidering affective engagement in historical empathy. Theory Res Soc Educ. 38(1):6–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2010.10473415.

- Eriksson B. 2021. Christofer Columbus upptäckt av Amerika. SO-Rummet. https://www.so-rummet.se/fakta-artiklar/christofer-columbus-upptackt-av-amerika#.

- Foster S. 1999. Using historical empathy to excite students about the study of history: can you empathize with Neville Chamberlain? Soc Stud. 90(1):18–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377999909602386.

- Garcia P, Rossiter M. 2010. Digital storytelling as narrative pedagogy. Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference. p. 1091–1097.

- Gibbons P. 2016. Stärk språket stärk lärandet—Språk- och kunskapsutvecklande arbetssätt för och med andraspråkselever i klassrummet. 4th ed. Stockholm: Hallgren & Fallgren.

- Gottschall J. 2012. The storytelling animal: how stories make us human. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Grabe W, Stoller FL. 1997. Content-based instruction: research foundations. the content-based classroom. Perspect Integr Lang Content. 1:5–21.

- Halliday MAK, Matthiessen MIM. 2014. Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar. 4th ed. London: Routledge.

- Hamer J, Hoodless P. 1998. History and english in the primary school: exploiting the links. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203014028.

- Hawkey K. 2004. Narrative in classroom history. Curric J. 15(1):35–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/1026716032000189461.

- Kindenberg B. 2021. Fixed and fluid: negotiating genre metastability in instructional practice [licentiate thesis]. Stockholms universitets förlag [Stockholm University Press].

- Kindenberg B. 2022. Narrative and analytical interplay in history texts: recalibrating the historical recount genre. J Curric Stud. 54(1):85–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2021.1919763.

- Kohlmeier J. 2006. “Couldn’t she just leave?”: the relationship between consistently using class discussions and the development of historical empathy in a 9th grade world history course. Theory Res Soc Educ. 34(1):34–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2006.10473297.

- Levstik LS. 1986. The relationship between historical response and narrative in a sixth-grade classroom. Theory Res Soc Educ. 14(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.1986.10505508.

- Martin J, Rose D. 2008. Genre relations: mapping culture. London: Equinox.

- Martin JR, White PRR. 2005. The language of evaluation: appraisal in English. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Persaud I. 2019. Insider and outsider analysis: constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing narratives of seychelles’ geography education. int j qual methods. 18:160940691984243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919842436.

- Rothery J, Stenglin M. 1997. Genre and institutions: Social processes in the workplace and school. In: Martin JR & Christie F, editors. Entertaining and instructing: Exploring experience through history. London: Continuum; p. 231-263.

- Skolnick J, Dulberg N, Maestre T. 2004. Through other eyes: developing empathy and multicultural perspectives in the social studies (Stokes S, editor). Ontario: Pippin Publishing Corporation.

- Stolare M. 2014. På tal om historieundervisning: Perspektiv på undervisning i historia på mellanstadiet. ADNO. 8(1):9–19. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.1101.

- Swedish Research Council. 2017. Good research practice. Stockholm: Swedish Research Council.

- VanSledright B, Brophy J. 1992. Storytelling, imagination, and fanciful elaboration in children’s historical reconstructions. Am Educ Res J. 29(4):837–859. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312029004837.

- Walqui A. 2006. Scaffolding instruction for English language learners: a conceptual framework. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 9(2):159–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050608668639.

- Wineburg S, Martin D. 2004. Reading and rewriting history. Educ Leadersh. 61(1):42–45.

- Wineburg S. 1991. On the reading of historical texts: notes on the breach between school and academy. Am Educ Res J. 28(3):495–519. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312028003495.