Abstract

This study investigates conceptualisations of ‘good’ writing held by local education leads, primary school teachers and their pupils following the most recent iteration of England’s National Curriculum. Despite curricular changes designed to improve writing performance, significant discrepancies in ‘good’ writing constructs and priorities are recorded across stakeholder groups: leads primarily value the interpersonal and stylistic aspects of writing, pupils conceptualise writing quality as a mastery of ‘technical accuracy’ whereas teachers frame writing as an opposition between reception matters and technical accuracy. Our analysis also indicates that the latest curriculum guidelines provide less detailed information on the non-compositional aspects of writing than earlier descriptors. This is likely to influence school practice and negatively impact the development of a shared concept of ‘good’ school writing that may be foundational for substantial improvements in children’s writing outcomes.

1. Introduction

Writing is a key literacy skill, but standards of children’s writing have long been a cause for concern in England. In the 2000s, Ofsted reports highlighted that ‘despite improvements in teaching writing … many secondary-age students … find writing hard, do not enjoy it, and make limited progress’ (cited in Lines Citation2012: 167). Along the same lines, the 2012 Department for Education paper noted that writing remained ‘the subject with the worst performance compared with reading, maths and science at key stages 1 and 2’ (DfE Citation2012: 7), and the trend has been maintained in more recent reports (e.g. DfE Citation2022).

Teaching, learning and assessment policy in the last decade has accordingly been modified to address perceived issues with writing. 2014 witnessed the implementation of a new National Curriculum which, shortly after, moved away from level descriptors to age-related levels of attainment to assess pupils’ progress on writing. At the time of the change, Lines (Citation2014) observed that:

for the last two decades, level descriptors have been a common classroom currency for describing performance, providing feedback and setting targets. In their absence, presumably teachers and their students will need to find a new ‘shared language’ for evaluating writing quality. Thus it will be increasingly important to attend to teachers’ and students’ own descriptions of ‘good writing.’ (34)

This article contributes to research on school writing by examining ‘good’ writing constructs from the perspective of teachers, pupils and local policymakers, a wider set of stakeholders than in previous studies (Lambirth Citation2016; Clarkson Citation2023). The study is particularly timely, as there are now full cohorts of pupils who have completed their key stage (KS) 1 and 2 education since the removal of the National Curriculum level descriptors, and concerns about writing enjoyment and attainment are at an all-time high after COVID-19. The Juniper Education National Dataset Report (Citation2022) notes that writing has taken ‘the hardest hit’ in performance with the pandemic, a claim substantiated by the 2023 KS2 national dataset: 71% of pupils met the expected standard in writing that year, down from 78% in 2019. Similarly, recent National Literacy Trust writing surveys indicate ‘alarmingly low levels of writing enjoyment among children and young people’ (Clark et al. Citation2023: 5).

We explore the notion of ‘good’ writing and writing policies in the school context in Section 2, while Section 3 introduces the study’s methods. Section 4 is devoted to data analysis and discussion, and the study’s key findings and implications are summarised in Section 5.

2. Literature review

2.1. The concept of ‘good’ writing

Making the concept of ‘good’ writing accessible for effective learning, teaching and assessment practices requires a gold-standard for writing and a clear outline of what success looks like. Bearne and Reedy (Citation2017) observe this ‘include[s] judgements about how well the writer communicates with the reader, the organisation of the piece and how effectively it conveys meaning. It will also include marking vocabulary, spelling, punctuation and grammar’ (368). However, the choices writers face are far too variable to be neatly delineated and judged by a fixed set of criteria (Sadler Citation1989; Lines Citation2014).

Additionally, any gold-standard of writing is dependent on socio-political ideologies permeating school practice. Lines (Citation2014) observes that what English schools value has evolved over the past 75 years from ‘formal rhetorical grammar and correctness’ to ‘more emphasis on personal voice and self-expression’ and ‘an interest in multimodal communication’ (22–23). It is, therefore, likely that, within a single school, variable writing constructs are at work as teachers operationalise different quality constructs based on the writing and assessment views prevalent when they train.

Professional training and public standard criteria only constitute one side of teachers’ conceptualisations of writing: individual beliefs and subject knowledge of writing also play an important role and may not align with received criteria (Lines Citation2012; Myhill et al. Citation2013; Clarkson Citation2019, Citation2023). An additional consideration is that, while teachers’ writing quality constructs influence students’ conceptualisations of writing and written tasks, they cannot be transformed into explicit learning constructs for internalisation and use (Lines Citation2012; Mackenzie and Petriwskyj Citation2017).

Previous research notes differences between teachers’ and learners’ overall perceptions of ‘good’ writing (Lines Citation2014). Teachers’ constructs are often based on holistic views where excellence in writing is marked by an attention to aspects such as content, style and audience (Humphry and Heldsinger Citation2019). By contrast, young primary learners frequently foreground neat handwriting and punctuation because of their visual saliency on the page (Shook et al. Citation1989; Wray Citation1994). By the end of primary school, these restricted views of writing tend to give way to a more balanced view where creativity and audience aspects are also valued (Tamburrini et al. Citation1984; Wray Citation1994).

Constructs of writing in school settings have also been examined from wider, discourse analytical perspectives (Peterson et al. Citation2018). Using Ivanič’s (Citation2004) Discourses of Writing framework, Lambirth (Citation2016) highlights that primary school pupils’ dominant discourse, the ‘skills discourse’, is focused on technical accuracy: writing is ‘a means to present oneself as a writer, above all else, “correctly”’ (230). The author interprets this as a reflection of participating teachers’ perceptions of curriculum demands, understood as a need to provide children with ‘a formula for writing’ to ‘enable [them] to succeed in formal assessments’ (230). This further signals that (mis)conceptions of curriculum demands and changes have important consequences for writing quality constructs and assessment at all levels (Lines Citation2014). Recent work by Clarkson (Citation2023; see also Myhill and Clarkson Citation2021) additionally notes the existence of misalignments between teachers’ perceptions of writing and curricular demands, with curricular guidelines favouring the skills discourse while teachers’ views include a greater variety of discourses, particularly that of creativity.

Research has also considered perceptions of ‘good’ writing from an assessment-based perspective. In their exploration of assessors’ understanding and use of assessment writing criteria, Humphry and Heldsinger (Citation2019) found that the criteria markers perceive as relevant are varied, with authorial and reception issues consistently valued more highly than writing conventions. By contrast, Mariano et al. (Citation2022) evidence teachers’ tendency when assessing to focus on structural and surface-level secretarial skills. It is also worth noting here that, in England, the 2016 curricular implementations meant a change to teacher assessment modes, thus making Year 6 teachers ‘responsible for both the teaching and statutory assessment of writing at the end of primary school’ (Clarkson Citation2023: 268). In their assessor role, practitioners are expected to use teacher assessment guidance materials in combination with the National Curriculum programme of study.

The following section outlines former and current assessment materials for primary writing, focusing particularly on the changes they have undergone since the move from level descriptors to attainment bands.

2.2. Teaching writing and the national assessment criteria

Recent scholarship has commented on the gradual narrowing of the English curriculum, moving from the systemic functional linguistics genre-based pedagogy that had traditionally underpinned it toward becoming more focussed on mastery of technical skills of writing (Clarkson Citation2023). This was underlined, at the classroom level, by the introduction of the end of key stage 2 English Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling (GPS) test in 2013.

In general, the National Curriculum, along with the ‘Simple View of Writing’ (Berninger et al. Citation2009), has formed the guiding principles of teaching writing in England over the past 15 years. Transcription and composition frame The National Curriculum guidance. As a result of changes in the statutory assessments at the end of primary school (the above-mentioned GPS test), there is a consistent focus on teaching the grammar, punctuation and spelling aspects of those writing dimensions, to the extent that the recent Ofsted Review for English suggests that ‘preparation for external assessments distorts the curriculum’ (Citation2024).

Different programmes (‘schemes of work’) are available to support teaching writing. Individual schools can either buy into one of those schemes or develop their own writing curriculum, with product-oriented approaches currently being a popular option (e.g. Corbett’s Talk for Writing or similar). Other schemes of work adopt a ‘writing checklist approach’ to assessing children’s writing in each year; however, these are not widely used or standardised across schools. Those checklists often foreground aspects of spelling, punctuation and grammar. Alongside schemes of work, schools often make use of ongoing formative feedback, usually a combination of verbal and written feedback. Nevertheless, ‘this varies between schools according to individual school marking policies’ and sometimes ‘is not used well to help teachers gain a reasonable sense of what pupils have learned’ (Ofsted Review for English Citation2024).

Teachers are currently required to provide a ‘teacher assessment’ using a portfolio of each child’s writing examples. These are then assessed using the most recent teacher assessment exemplification materials and the criteria published within these to arrive at a judgement regarding whether the child is ‘working towards the expected standard’, ‘working at the expected standard’ or ‘working at greater depth’ (STA, Citation2016, Citation2017). One of the challenges for teachers is that while the published assessment criteria of the expected standard ‘represent an official construct of quality which can be used as a benchmark by teachers and students … the construct is not fixed or absolute’ (Lines Citation2014: 35). The emphasis placed on such constructs is also problematic, as it is produced as a summative judgement rather than a formative tool to support ongoing assessment of children’s writing in primary schools (which, as noted above, may also need further reassessment). This flexible, formative support is particularly important given the complexity of current classrooms, where, nationally, about one in four children are multilingual (DfE Citation2023) and may bring to the classroom different experiences and socio-cultural concepts of ‘good’ writing.

Before the shift from attainment levels in 2014, children’s writing at the end of KS2 was to be

lively and thoughtful. Ideas are often sustained and developed in interesting ways and organised appropriately for the purpose of the reader. Vocabulary choices are often adventurous and words are used for effect. Pupils are beginning to use grammatically complex sentences, extending meaning. Spelling, including that of polysyllabic words […] is generally accurate. Full stops, capital letters and question marks are used correctly, and pupils are beginning to use punctuation within the sentence. Handwriting style is fluent, joined and legible. (STA Citation2013: 6)

The use of ‘often’ and ‘generally’ indicates that, although the relevant elements were expected in the portfolios, the children were not expected to consistently use a wide range of examples of each aspect. The 2014 criteria foregrounds both the reader and the overall text production (grammar, vocabulary, spelling and punctuation) and backgrounds genre considerations (they are only mentioned in the explanations). The overall description is linguistically vague; the use of evaluative adjectives (e.g. ‘lively,’ ‘adventurous,’ ‘thoughtful’) is not helpful as regards linguistic performance. It is only basic punctuation marks that children were asked to use correctly; the mastery of other linguistic levels such as grammar and spelling is hedged in different ways: children begin to use complex sentences, polysyllabic spelling needs to be generally accurate.

In 2016, the criteria were revised to discontinue the use of level descriptors in favour of attainment levels (STA Citation2017). Notably, the number of criteria in the 2016 materials was half those in 2014 materials. The new criteria also placed greater emphasis on grammatical constructions and less detail on text-based considerations. Vocabulary descriptions emphasised matching lexis choice to context and register, although indications as to how to manipulate language for those stylistic purposes were more limited than in the 2014 guidelines. By contrast, the regulations clearly indicated the need for mastery of punctuation and spelling features, including those that were optional in the 2014 regulations, and provided clear specifications of such features to be mastered.

The materials were further revised in 2018. Subtle but significant differences to expectations were implemented (see Appendix 1 for a full comparison). In general, the continued rise in expectation is evident. For example, regarding verbs, expectations shifted from ‘mostly appropriate’ (2016) to ‘consistent and correct’ (2018). Similarly, in 2016, children could choose ‘whether or not to join specific letters’ as long as legibility, fluency and speed was maintained. However, from 2018 onwards, children are expected to ‘maintain legibility in joined handwriting when writing at speed’ (STA Citation2017: 5). The 2018 changes also show a further deemphasising of sentence-level features and greater focus on internal clause elements, even for text-cohesion. Orthographic and punctuation requirements are presented in a check list, allowing for the quantification of what is apparently valued (Moss Citation2017). Audience, style and genre-appropriateness factors associated with composition and text-related aspects are framed more generally than earlier descriptors-based frameworks, and, as noted by Clarkson (Citation2023), there is no mention of creativity.

3. Materials and methods

This study was part of a wider project on writing in primary schools conducted within Liverpool, an area often in England’s lowest 10% for writing attainment at KS2. Data were collected through a mixed-methods approach between first and fourth March 2022. Pupil data (Years 5 and 6) were collected in schools through an online questionnaire managed by teachers during class, a method dictated by COVID-19 measures. Schools ranged from two- to four-form entry. With the exception of one primary school, participating schools had a 20% higher rate of FSM pupils than the national average (DfE Citation2023). Two of these schools also had a high proportion of EAL students (34% and 49%). No participant metadata other than gender and school year were collected in order to preserve anonymity given that the questionnaire was administered via the classroom teachers. We selected 400 pupil questionnaires for analysis, ensuring even distribution across schools, years and gender.

Data from practitioners and education leads comes from two 90-min focus groups conducted online via an external professional focus group facilitator. The first group of nine participants included regional policymakers and representatives from local education organisations (education leads); the second was comprised of 10 teachers from the 10 schools where we collected the children’s data.

A week before convening the focus groups, the facilitator and researchers agreed a stakeholders’ agenda with the time allocated to each question. On the day, each question was asked to the whole group and the floor opened for discussion, with participants prompted if they had not voiced their opinion.

Pupil questionnaires consisted of 14 closed items that used a 4-point scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) and an open-response question on ‘good’ writing. Focus groups included open-response questions on perceptions and challenges of primary school writing. Elicitation materials included questions on what each group considered to be ‘good’ writing in the primary school context (see Appendix 2 for templates). Those questions were worded consistently, though tailored to informants’ knowledge and experience. This article is based on answers to the following questions from the focus groups (a) and the pupil survey (b):

What specific characteristics of ‘good’ writing would you expect to see in a child’s writing at the end of primary school (KS2)? (Education leads and teachers)

What makes a good piece of writing? (KS2 pupils)

We were interested in exploring each group’s quality conceptualisations as well as how those conceptualisations aligned and diverged and the potential implications in current school settings.

We read the focus group transcripts and free-comment responses from the questionnaires, transferred them to three separate Excel sheets and, in line with previous research (Lines Citation2012, Citation2014; Myhill et al. Citation2023), coded responses thematically at two levels of granularity. At the most basic level (, middle column), we categorised comments based on the writing feature described. The second-level analysis (, left column) consisted of clustering writing features into a range of thematic factors involved in producing a text.

Table 1. Thematic factors and writing features associated with ‘good’ writing.

We surveyed thematic typologies of writing for potential analytical frameworks (e.g. Dockrell et al. Citation2015; Humphry and Heldsinger Citation2019) before adopting Myhill et al.’s (Citation2023) Writing as a Craft model, which draws on professional ‘writers’ understanding about the craft of writing’ (404) and includes an extensive range of aspects central to teachers’ ‘subject content knowledge for the teaching of writing’ (409).

Adaptations we implemented concerned mapping school writing features onto Myhill et al. (Citation2023)’ thematic factors. For example, our ‘reader-writer relationship’ category includes a broader range of reception matters (and, therefore, of basic descriptive features) than Myhill et al. (Citation2023), as it recognises that a child’s piece of writing produced in a classroom will have two primary audiences: the intended audience and the teacher, as the pupil will make an explicit effort to meet the teacher’s expectations. Coding protocols (i.e. definitions for writing features and general adaptations of Myhill et al.s’ Citation2023 typology for our datasets) were agreed by the research team prior to data coding. Coding was done independently by two team members, who then agreed final theme and feature labels.

We then compared the relative quantitative presence of both thematic factors and writing features across all stakeholders’ responses. Each mention of a writing feature was computed as one token so that a single response might contain several classifiable tokens; for example, in (1), three writing features are present: writing stamina, punctuation and grammar.

(1) …the child who’s on track, should be at [sic] write an essay of two or three pages that should be properly punctuated. It should have formal grammar. (Lead)

Frequency differences of those thematic factors and writing features, as well as informants’ lexical choices when discussing them, form the basis of our writing quality constructs (Section 5). Although this type of quantitative analysis does not control for sample size (i.e. focus groups included fewer informants than the children’s questionnaire), previous research (Lines Citation2012, Citation2014; Lambirth Citation2016) suggests it constitutes a valid way of identifying trends in stakeholders’ conceptualisations.

4. Results

4.1. Writing feature analysis

summarises the frequency of each writing feature across stakeholder groups.

Table 2. Distribution of writing features across stakeholder groups.

Both teachers and leads consider reception – that is, the writer’s explicit attention to and engagement of the reader – among the most important aspects of ‘good’ writing; however, there are no further overlaps between the groups’ most frequent descriptive features. In fact, across groups, there is a noticeable difference in breadth of features considered most important: leads mostly favour discourse-related features such as genre, purpose, and reader (2), while teachers’ choices are slightly more mixed, highlighting both reception matters (3) as well as curriculum demands (i.e. features required in writing instruction) (4). Pupils’ responses mix formal and creative factors, with punctuation (5) and creative flair (6) foregrounded.

(2) …a child can write across a range of genres in and get their meaning and purpose across (Lead)

(3) …a good writer is one who engages the reader (Teacher)

(4) …we’re doing a lot of work in class on having that strong finish (Teacher)

(5) …good spelling, good punctuation, adjectives (Pupil)

(6) …include description of the surroundings and characters and have a great storyline (Pupil)

However, isolated feature analyses can only provide a partial picture of writing tendencies. Further analysis is needed of how individual features play against each other within the same thematic factor (Section 4.2) and how those operate when considered together (Section 4.3).

4.2. Thematic factor analysis

The sections below analyse the distribution of individual features within the thematic categories described in Section 3.

4.2.1. Language choices

Language choices comprise orthographical, stylistic and lexico-grammatical choices made by writers to translate ideas into written linguistic form. While aspects of transcription and composition have always been taught in KS2, they have been foregrounded since the introduction of the GPS test. At the same time, the publication of the Oxford Language Report ‘Why Closing the Word Gap Matters’ (Oxford University Press, Citation2018) and Quigley’s (Citation2018) ‘Closing the Vocabulary Gap’ refocused attention on the importance of explicit vocabulary teaching.

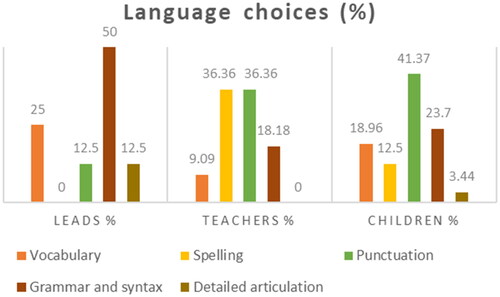

These trends are reflected in . Punctuation, grammar and vocabulary are consistently recorded in all stakeholders’ answers, although with notably different distribution across groups.

Figure 1. Language choices: Distribution of writing features.

Leads’ responses place special emphasis on grammar and syntax. Example (1) in Section 3 echoes traditional associations of written language with formal domains and writing styles (Milroy and Milroy Citation2012[1985]). Comments on vocabulary are rather general, noting the importance of the lexicon in text-composition processes, particularly to facilitate a writer’s range of detailed expression but lacking a rationale for its importance:

(7) For me, vocabulary is really important (Lead)

(8) …vocabulary, a love of words…I would see as a strength (Lead)

Teachers’ responses situate spelling and punctuation as the category’s most important features. However, close reading indicates more mixed views: these features are seen as key by some teachers (9) while others mention them only to demote their importance relative to other factors (10). Vocabulary richness and grammatical competence are unanimously noted by teachers as central to a writer’s resourcefulness.

(9) … what they’re going to use in life are things like spelling and punctuation (Teacher)

(10) …if you were to read a piece of writing to me…I wouldn’t necessarily know if those words have been spelled correctly. Or whether they use paragraphs or whether they use punctuation (Teacher)

Pupils’ comments present punctuation (11) as key among writing’s language-oriented aspects (41.36%), followed at a distance (23.7%) by grammatical competence (12). Spelling and vocabulary are less prominently mentioned and focus on accuracy and lexical variation. Their detailed articulation of ideas is presented as a matter of ‘adding detail’ to the text rather than careful expression (13):

(11) [Good writing is] fronted adverbials[,] capital letters[,] comma[,] full stops[,] brackets (Pupil)

(12) …strong words in it like adjectives and adverbs, expanded noun phrases (Pupil)

(13) What makes a good piece of writing is when you add a lot of detail into the writing and use a good variety of vocabulary (Pupil)

Further qualitative differences between pupils and other stakeholders are evident in this category. First, children’s language choice descriptions employ the curriculum discourse to a greater extent than the others. Note, for instance, that ‘ambitious’ vocabulary is highlighted in the criteria for the end of KS2 (STA Citation2017: 5).

(14) Adventurous Vocabulary, Exciting Adjectives, Amazing Descriptive Paragraphs (Pupil)

(15) When it has effective vocabulary and it’s not just like said. And when its [sic] interesting. (Pupil)

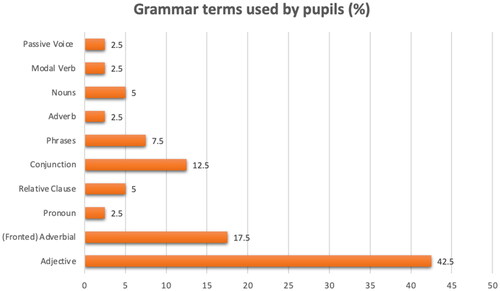

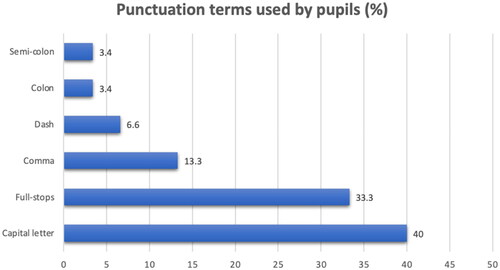

Second, pupils seem to associate linguistic choice with the deployment of specific, often isolated features. This is particularly noticeable in connection with grammar and punctuation features. As and show, pupils see adjectives, (fronted) adverbials, capital letters and full stops as key to high-quality writing.

Figure 2. Pupils’ use of grammar-related terms within the ‘grammar and syntax’ writing feature (55 tokens).

Figure 3. Pupils’ use of punctuation-related terms within the ‘punctuation’ writing feature (96 tokens).

These features are explicitly documented in National Curriculum expectations and KS2 criteria: fronted adverbials appear in Year 4 and adjectives in Years 1, 2, 4 and 5. Semi-colons, dashes, colons and commas are provided as examples of punctuation used by children ‘working at the expected standard’ in the 2016 KS2 criteria.

Third, many of these responses conceptualise linguistic finesse not as a careful stylistic deployment but as a quantification of features (see 13, 16–18):

(16) High use of adjectives and commas and joined writing (Pupil)

(17) To add a lot of good adjectives and to plan before you write (Pupil)

(18) Lots of detail, also lots of grammar and punctuation (Pupil)

This not only betrays a formulaic understanding of the value of language for writing where features are used in bulk as a way of improving or making a text more interesting (Myhill Citation2011; Chen and Myhill Citation2016) but also evidences that pupils view those easily quantifiable features from the curriculum as the most valuable in their writing (Moss Citation2017).

4.2.2. Being an author

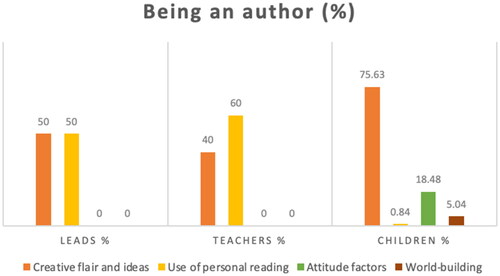

This category pays explicit attention to self-expression, or the writer’s ‘personal resources and intentions’ (Myhill et al.’s Citation2023: 409) when producing a text. Self-expression is often linked to creativityFootnote1, which in our data are consistently mentioned by all stakeholders, albeit with vastly different emphases between adults and children ().

Figure 4. Being an author: Distribution of writing features.

In teachers’ and leads’ views, creativity is mainly understood as the development of personal style:

(19) …a good piece of writing has that child’s individual creative flair (Teacher)

(20) …you should hear the child’s voice in their writing (Lead)

These groups emphasise that reading habits play an important role: aligning with a long tradition of research (Britton 1970; Cremin and Myhill Citation2012), they note that good writers often take inspiration from their reading. Interestingly, the use of reading as a scaffold for writing is only mentioned in the ‘working at a greater depth’ national criteria, whereas it is obvious these stakeholders consider it a key factor.

(21) …good readers are more likely to be good writers. And I think that’s quite an important thing because obviously what children are reading is more likely to be reflected within their writing (Lead)

Comments on creativity as part of ‘being an author’ are also strongly present in children’s data (75.6%). A ‘good’ creative text uses ‘imagination and thought’ (22–23). However, pupils’ responses single out the ability to produce ‘descriptions’ (24). These sometimes relate to world-building (24) and, in line with claims on language choices, repeatedly involve quantification (25–26). Comments on personal reading as a springboard for writing are virtually non-existent in the children’s data.

(22) [A] perfect piece of writing would be lots of though [sic] (Pupil)

(23) I think a good piece of writing is when …you write from your heart and your own or someone else’s experience (Pupil)

(24) A good piece of writing should include description of the surroundings and characters and have a great storyline (Pupil)

(25) …a good piece of writing would include lots of description (Pupil)

(26) …a good piece of writing is when you add a lot of detail into the writing and use a good variety of vocabulary (Pupil)

This category’s other aspect that children consistently mention relates to attitude, specifically motivational and cognitive factors required to produce high-quality texts.

(27) …a good piece of writing is when you have all your punctuation and spellings correct or if you have tried really hard and put lots of effort in it (Pupil)

(28) Good vocabulary and to never give up. (Pupil)

These are indicative of wider educational rhetoric, particularly given the language. For example, motivational comments (27) echo growth mindset theory popular in the early 2000s (Dweck Citation2006).

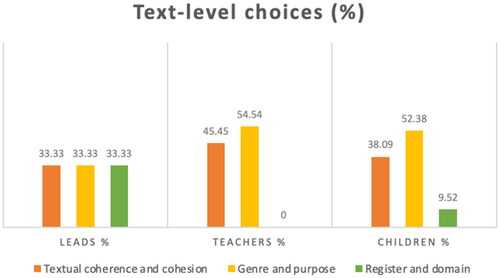

4.2.3. Text-level choices

The text-level category moves the focus away from sentence-internal aspects of text creation towards discourse-based considerations, or the choices made by authors to produce a unit of meaning that adheres to text-type expectations ().

Figure 5. Text-level choices: Distribution of writing features.

As in previous sections, differences are attested across stakeholder groups: while leads suggest a ‘good’ piece of writing balances the importance of these three discourse-related features, teachers and pupils particularly highlight the importance to adhere to genre conventions and have a clear purpose. Register and domain considerations are mentioned significantly less in these latter groups:

(29) …by the end of primary phase, we’re looking for them to be able to write in multiple genres. It’s not just storytelling at that point…they should be able to write letters, they should be able to write information texts (Teacher)

Note that children’s responses further suggest a marked association of ‘good’ writing with the fiction genre (30–32):

(30) Rhetorical questions, dashes, neat handwriting, similes, metaphores [sic]. (Pupil)

(31) When people have twists and turns in their storyline and things happen that you did not expect. (Pupil)

(32) A good piece of writing should include description of the surroundings and characters and have a great storyline. (Pupil)

Given that students write both fiction and non-fiction pieces for school, the association with fiction texts may partly reflect their reading in and out of school. Yet the trend may also be motivated by the evident emphasis on narrative writing in the current STA (Citation2017) criteria: ‘in narratives, describe settings, characters and atmosphere’ and ‘integrate dialogue in narratives to convey character and advance the action’ (5).

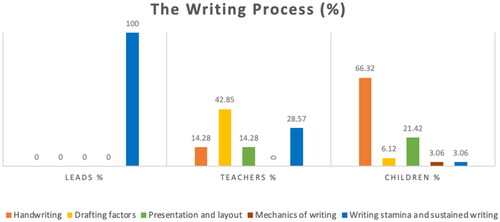

4.2.4. The writing process

This thematic category records the usual components of the writing process, together with factors that blend different types of writing skills and motivation for writing. summarises our findings. In the National Curriculum, the composition sections of the writing criteria are formed around a process-approach to writing, encouraging children to plan, draft and write, evaluate and edit, and proofread throughout KS2. This is combined with a genre-approach in the criteria, as, in the planning stage, children are expected to use similar texts as models for their own. Another particularly notable aspect of the writing process in the National Curriculum is ‘writing stamina’, the ability to write for a sustained period. Year 2 children (aged 6-7) are expected ‘to develop positive attitudes towards and stamina for writing’ (DfE Citation2013: 21). Although the end of KS2 criteria does not explicitly state the length of pieces that children should be able to write, the exemplification materials provide insight. Two portfolios exemplifying the ‘expected standard’ contain six pieces of writing, some ‘short’ pieces averaging c450 words and some ‘extended’ writings of c750 words.

Figure 6. The writing process: Distribution of writing features.

Writing stamina is the only factor noted in the leads’ responses (100%) in this category.

(33) For me, it’s an extended piece of writing (Lead)

Although teachers’ comments connect writing stamina and textual coherence (34), the most frequently highlighted feature is the need for children to actively consider drafting aspects such as editing and evaluation (42.85%).

(34) …the stamina of the handwriting and making sure that it doesn’t slip (Teacher)

(35) …being a writer is being able to go back and edit and improve your work (Teacher)

Children’s responses, however, present a different picture. Physical considerations of writing production and writing stamina feature minimally in their responses (3.06%), normally as an afterthought and, in relation to writing stamina, as a matter of textual quantity (i.e. good writing is ‘a long piece’). Drafting comments score only slightly higher (6.12%). Handwriting is, by contrast, high in pupils’ writing agenda, often in connection with producing a decodable text (36) that adheres to teachers’ presentation expectations (6.32%). Paragraphing and signposting are also included in the children’s main concerns (37-38), but these layout matters do not arise in the other groups.

(36) [N]eat writing so you can actually read it (Pupil)

(37) A good piece of writing includes neat handwriting, figrative [sic] language and paragraphs. (Pupil)

(38) …you have to focus, punctuate correctly, be creative and have a title and underlined (Pupil)

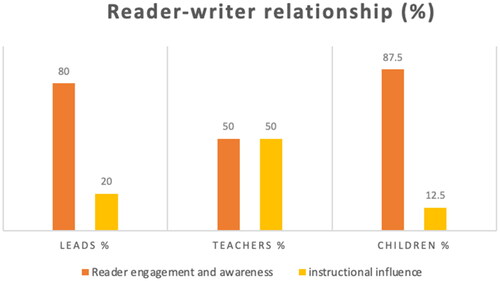

4.2.5. Reader–writer relationship

This theme addresses how the written text interacts and creates rapport between writer and audience. As noted above, our understanding of ‘reader/audience’ is more encompassing than in Myhill et al.’s (Citation2023) original model, as texts produced in the classroom try to speak to both an intended audience and the teacher ().

Figure 7. Reader–writer relationship: Distribution of writing features.

Unsurprisingly, it is in teachers’ responses where both audiences are fully recognised: a ‘good’ text engages the audience and follows the teacher’s instructions. Qualitative analyses, however, indicate that those two factors may not always be linearly aligned (39–40) and highlight the importance of a writer’s personal resources over classroom instruction in producing a successful text.

(39) …you can teach formulaic writing, but to be a really good writer. I think that’s [creativity] what obviously sets it apart.

(40) …you can teach children the formula, you can teach them what they need to have…But it’s that style…that flair for writing.

Leads’ and pupils’ responses by contrast foreground the importance of the general reader over teacher instruction:

(41) …a good writer is one who engages the reader… if you were to read a piece of writing to me, you would see my enjoyment through my face (Lead)

(42) A text which hooks the reader but doesn’t tell the story line to [sic] quick (Pupil)

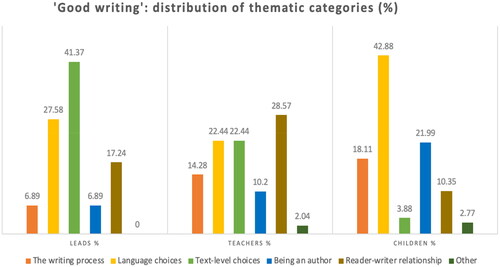

4.3. Discussion: Thematic factors and writing constructs

The sections above provided a fine-grain analysis of specific writing features and the thematic factors within which they can be couched. This section explores the distributional profile of thematic factors, as they instantiate stakeholders’ constructs of writing quality ().

Figure 8. Summary of thematic factors.

It is important to highlight that all stakeholder groups feature different repertoires of writing quality constructs. The following analyses simply highlight the main trends in the data. For instance, literary-oriented views that foreground ‘being an author’ and creative meaning-making are attested in all stakeholder groups. However, they account for 10% or less of the leads’ and teachers’ responses (). As such, they are considered to complement and expand on more salient quality constructs for those groups, described below in more detail.

Education leads primarily value interpersonal and stylistic aspects of writing associated with text-level choices such as how ‘fit for purpose’ the text is (over 40%). Ivanič (Citation2004) argues such conceptualisations produce discourses that foreground ‘appropriacy’ of styles and ‘efficacy’ ‘in achieving social goals’ over linguistic correctness (234, 237). Along these lines, comments on ‘confidence, effectiveness, and enjoyment’ are rife in stakeholders’ comments. But note that leads also mention ‘formality’, a feature associated with standard written language in traditional normative views as part of the ‘fit for purpose’ construct. This suggests that appropriacy and efficacy of writing need to work within the parameters of standard written English:

(43) It should have formal grammar. (Lead)

(44) Levels of formality, so command over the register of language…a skilled writer might be able to make confident shifts within one piece of writing (Lead)

In comparison to the other groups, leads’ responses include fewer descriptive features of writing. This is likely the result of their limited day-to-day classroom experience compared with teachers and pupils, since classroom activities are concerned with establishing the processes that support the final product. Overall, their results suggest a traditional view of ‘good’ writing that favours reception matters and, at the language-specific level, highlights the centrality of areas associated with ‘linguistic control’ such as grammar and syntax (Michael Citation1987). In this respect, leads’ responses can be said to align with the end of KS2 expectation about ‘writ[ing] effectively for a range of purposes and audiences’ (STA Citation2017: 5).

Pupils overwhelmingly conceptualise writing quality as mastery of ‘technical accuracy’ (42.88%), achieved through an adept manipulation of language choices and particularly, as noted in section 5.2.1, accuracy in orthographical and grammatical considerations. Linguistic choices clearly align with the skills discourse’s emphasis on ‘correct use’ across the features under consideration (Ivanič Citation2004; Lambirth Citation2016). Note, in this respect, the frequent use of evaluative adjectives: for example, ‘correct’ grammar (16 tokens) and punctuation (14 tokens), ‘good’ punctuation (18 tokens), and ‘good’ vocabulary (16 tokens). This is unsurprising, as these composition features are often described and codified in standard grammars of written English and are telling of standard language-cultures. They also feature in many of the National Curriculum descriptors, often with similar adjectival/adverbial collocations (e.g. ‘correct/correct(ly)’, ‘adequate(ly)’/’appropriate(ly)’). More generally, pupils’ responses mirror the criteria foregrounded and increased in expectation in recent years, both quantitatively through frequency of mentions and qualitatively in their lexicon that resembles policy documents. Of particular note is children’s emphasis on punctuation and handwriting, which closely matches the writing aspects where expectations were raised in 2018 materials.

(47) …you have all your punctuation and spellings correct (Pupil)

(48) A good piece of writing is one with paragraphs and correct grammar. I especially like pieces of writing that use correct punctuation too (Pupil)

Children’s responses also record the widest variety of ‘good’ writing features across stakeholder groups, including a range of behavioural aspects not generally considered part of the writing process per se (e.g. the importance of a growth mindset).

Teachers have a more rounded view that considers linguistic, text and reception choices as key elements of ‘good’ writing. No thematic factor reaches over 40% of teachers’ responses, with most being near 20%. However, this balanced middle-ground of both ‘technical accuracy’ and ‘fit for purpose’ writing constructs seems unstable in several respects. First, as example (49) below shows, teachers self-identify as teachers and readers. This reflects a common issue in England, that ‘teachers…do not see themselves as writers’ (Gardner Citation2018: 11) or ‘writing teachers’ (Clarkson Citation2023: 272) even if educational research has long demonstrated the benefits of ‘teacher-as-writers’ classroom pedagogy. This often relates to perceptions of writing as a ‘problem’ teaching area and the preference for narrow writing concepts that mainly rely on standard, narrative genres (Clarkson Citation2023).

(49) I give one response as a teacher, or perhaps another response as a reader. And perhaps what we’re looking for now because of how the curriculum guides us…if you asked us socially, and we weren’t under these constraints, perhaps our answers will be different. So for me, a good writer is one who engages the reader…And on a teacher level I’ve been looking for…composition and effect, punctuation (Teacher)

Second, the dual self-identification also evidences a struggle between the teacher as an ‘average writer-reader subject’ who conceptualises writing quality as text-level and audience-driven, and the teacher as a ‘formal’ educator constrained by curricular needs to develop pupils’ transcription and composition skills, leaving little room for children’s creative experimentation. Note that ‘being an author’ features the lowest thematic scores (10%) in teachers’ responses.

Again, polarised views of writing quality and the dual sociolinguistic position of teachers as language users versus ‘official’ language providers/models have been amply discussed in previous research (Myhill Citation2001; Lines Citation2012; Clarkson Citation2019). In the context of our work, these dualities are likely to influence students’ understanding of not just what features are expected in their writing but also how they can be effectively used to produce ‘good’ writing.

5. Conclusions and educational implications

These analyses crucially show that, despite recent curricular changes, there are noteworthy differences in what ‘good’ school writing means for our three stakeholder groups. Divergences in writing constructs were anticipated given that quality constructs are attitudinal in nature; however, greater alignment in the stakeholders’ writing priorities within those constructs was expected in the current curricular context, which aims to raise writing achievement outcomes.

Leads and teachers highlight the importance of ‘quality choices’—be it grammatical, lexical, or stylistic—as the baseline of ‘good’ writing. By contrast, children’s writing quality appears to rely on quantification, i.e. adding lots of features. This trend has been discussed in connection to lexico-grammatical choices in school writing (see, among others, Myhill et al. Citation2011; Myhill et al. Citation2013). Nevertheless, our data suggests its pervasiveness across all thematic factors. While this phenomenon needs further investigation, the implication of this is that recent emphasis on developing children’s writing stamina, observed in our leads’ responses and, more widely, in publications adhering to writing-gap ideologies (Quigley Citation2022), might play a part in these quantitative conceptualisations of writing quality: repetition and/or addition are, for pupils, effective ways of writing ‘longer’.

Pupils also associate ‘good’ writing with technical accuracy. Previous research (Wray Citation1994) has shown that, by the end of primary school, pupils develop a more balanced view of writing which, in line with other stakeholders’ views, values aspects of creativity and audience alongside secretarial skills. Interestingly, although our data does record creative and reception factors in pupils’ responses, it does not reflect this balanced view. Instead, mastery of ‘correct’ punctuation is still the predominant writing priority for the pupils involved in this study. This has implications for the way in which practitioners frame, communicate and scaffold conceptualisations of ‘good’ writing in the classroom.

The recent foregrounding of transcriptional elements in English in KS2 has been mentioned as a factor influencing pupils’ technically focussed writing priorities, yet an equally important consideration is teachers’ conflicted views about which writing features and factors are central in ‘good’ writing. In these situations, school writing tends to become a fragmentary activity that demotes the importance of less quantifiable aspects of writing (Mariano et al. Citation2022), which, as our data shows, are those that leads and teachers value. This is further compounded by (a) a lack of statutory guidance to support ongoing formative assessments of children’s writing in primary schools and (b) the limited detail provided in the new curriculum guidelines on non-compositional aspects of writing. This is likely to impact teachers’ practices, making it more difficult to effectively assess discourse-based aspects and, consequently, devote greater attention to features that can be confidently isolated and commented on (Mariano et al. Citation2022).

In this way, teaching practices perpetuate the predominance of writing as the ‘development of technical skills’, which teachers and leads clearly do not prioritise. They may also disregard our current plurilingual and multicultural classroom landscape. As discussed above, writing is a complex process that involves technical skills as much as the conveyance of ideas, styles and cultural norms. Multilingual students may bring diverse narratives and styles to their writing, which enrich the classroom but also pose challenges for standard assessment practices that may not always value this diversity.

The education leads’ conceptual dis-alignment with the (perceived) curricular emphasis on the technical aspects of writing (Section 4.3) is particularly notable given their role as enactors of national curriculum and pedagogic guidelines. This raises further questions on whose curriculum preferences the most recent frameworks represent and has implications for policymakers in terms of the potential future direction of guidance for teachers.

Further research is needed to confirm and expand the findings described here. However, we hope this study raises awareness of the still-pervasive differences in stakeholders’ conceptualisation of ‘good’ writing and begins explorations of how curriculum guidelines may impact on the much-needed development of a quality-based, holistic and shared concept of ‘good’ writing.

UK Research and Innovation (Grant 177997);

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We understand creativity as ‘recognising and using the infinite possibilities of language’ (Cremin and Myhill Citation2012: 23). This supersedes more traditional associations with ‘artistry’ or ‘inventiveness’.

References

- Bearne E, Reedy D. 2017. Teaching primary English: subject knowledge and classroom practice. London: Routledge.

- Berninger V, Garcia N, Abbott R. 2009. Multiple processes that matter in the writing instruction and assessment. In G. Troia (Ed.), Instruction and assessment for struggling writers: Evidence based practices (p. 15–50). New York: Guildford Press.

- Chen H, Myhill D. 2016. Children talking about writing: Investigating metalinguistic understanding. Linguistics and Education. 35:100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2016.07.004.

- Clark C, Bonafede F, Picton I, Cole A. 2023. Children and young people’s writing in 2023. National Literacy Trust Research Report. London: National Literacy Trust. https://cdn.literacytrust.org.uk/media/documents/Writing_in_2023.pdf.

- Clarkson R. 2023. A shared understanding of good writing? Exploring teachers’ perspectives. WAP. 14(3):267–295. https://doi.org/10.1558/wap.23446.

- Clarkson RJ. 2019. Key stage 2 teacher assessment of writing: exploring aspects of validity. [PhD thesis]. University of Exeter.

- Cremin T, Myhill D. 2012. Writing voices: creating communities of writers. London: Routledge.

- DfE. 2012. What is the research evidence on writing? https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_d ata/file/183399/DFE-RR238.pdf.

- DfE. 2013. The national curriculum in England: Key stages 1 and 2 framework document. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/425601/PRIMARY_national_curriculum.pdf.

- DfE. 2022. Key stage 2 attainment. https://exploreeducation-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/key-stage-2-attainment-nationalheadlines#releaseHeadlines-summary.

- DfE. 2023. Schools, pupils and their characteristics, Academic year 2022/23: June 2023. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics

- Dockrell JE, Connelly V, Walter K, Critten S. 2015. Assessing children’s writing products: The role of curriculum-based measures. Br Educ Res J. 41(4):575–595. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3162.

- Dweck CS. 2006. Mindset: the new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

- Gardner P. 2018. Writing and writer identity: the poor relation and the search for voice in ‘personal literacy’. Literacy. 52(1):11–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12119.

- Humphry S, Heldsinger S. 2019. Raters’ perceptions of assessment criteria relevance. Assess Writing. 41:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2019.04.002.

- Ivanič R. 2004. Discourses of writing and learning to write. Lang Educ. 18(3):220–245. https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/3948/1/ivanic1.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780408666877.

- Juniper Education. 2022. National Dataset Report 2022: The impact of the covid-19 pandemic on primary school children’s learning. https://junipereducation.org/resource/downloads/national-dataset-report/.

- Lambirth A. 2016. Exploring children’s discourses of writing. English in Education. 50(3):215–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/eie.12111.

- Lines H, et al. 2012. A matter of personal taste”: Teachers’ constructs of writing quality in the secondary school English classroom. In C. Bazerman, editors. International advances in writing research. Anderson, South Carolina: Parlor Press; 167–189.

- Lines HE. 2014. It’s a matter of individual taste, I guess”: Secondary school English teachers’ and students’ conceptualisations of quality in writing. [PhD Dissertation]. University of Exeter.

- Mackenzie NM, Petriwskyj A. 2017. Understanding and supporting young writers: Opening the school gate. Aust J Early Childhood. 42(2):78–87. https://doi.org/10.23965/AJEC.42.2.10.

- Mariano E, Campbell-Evans G, Hunter J. 2022. Writing assessment in early primary classrooms: Thoughts from four teachers. AJLL. 45(1):85–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-022-00007-1.

- Michael I. 1987. The teaching of English from the sixteenth century to 1870. Cambridge: CUP.

- Milroy J, Milroy L. 2012[1985]. Authority in language. Investigating Standard English. London: Routledge.

- Moss G. 2017. Assessment, accountability and the literacy curriculum: Reimagining the future in the light of the past. Literacy. 51(2):56–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12104.

- Myhill D, Clarkson R. 2021. School writing in England. In J.V. Jefrey and J. J. Parr, editor. International perspectives on curricula and development: a cross-case comparison. London: Routledge.

- Myhill D, Cremin T, Oliver L. 2023. Writing as a craft: re-considering teacher subject content knowledge for teaching writing. Res Pap Educ. 38(3):403–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2021.1977376.

- Myhill D, Jones S, Watson A. 2013. Grammar matters: How teachers’ grammatical knowledge impacts on the teaching of writing. Teach Teach Educ. 36:77–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.07.005.

- Myhill D, Lines H, Watson A. 2011. Making meaning with grammar: a repertoire of possibilities. Metaphor. 2:1–10.

- Myhill D. 2001. Writing: crafting and creating. English Educ. 35(3):13–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-8845.2001.tb00744.x.

- Ofsted Review for English. 2024. Telling the story: the English education subject report. Ofsted.

- Oxford University Press. 2018. Why closing the Word Gap matters: Oxford Language Report. Oxford University Press.

- Peterson SS, Parr J, Lindgren E, Kaufman D. 2018. Conceptualizations of writing in early years curricula and standards documents: International perspectives. Curricul J. 29(4):499–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2018.1500489.

- Quigley A. 2018. Closing the vocabulary gap. London: Routledge.

- Quigley A. 2022. Closing the writing gap. London: Routledge.

- Sadler R. 1989. Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instr Sci. 18(2):119–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00117714.

- Scull J, Mackenzie NM, Bowles T. 2020. Assessing early writing: a six-factor model to inform assessment and teaching. Educ Res Policy Prac. 19(2):239–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-020-09257-7.

- Shook S, Marrion L, Ollila L. 1989. Primary children’s concepts about writing. J Educ Res. 82(3):133–139. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40539583. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1989.10885882.

- STA. 2013. 2013 Key stage 2 writing – moderation. Exemplification materials for teacher assessment. Level 4 (annotated). https://bso.bradford.gov.uk/userfiles/file/sta-ks2-writemod-un-l4.pdf.

- STA. 2016. 2016 teacher assessment exemplification: end of key stage 2, English writing: working at the expected standard: Leigh. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/653138/2018_exemplification_materials_KS2-EXS__Leigh_.pdf.

- STA. 2017. 2018 key stage 2 teacher assessment exemplification materials, English writing: working at the expected standard: Morgan. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/653133/2018_exemplification_materials_KS2-EXS__Morgan_.pdf.

- STA. 2018. KS2 teacher assessment moderation training. http://www.lancsngfl.ac.uk/curriculum/assessment/download/file/01%20KS2%20standard isation%20training%20presentation1.pdf.

- Tamburrini J, Willig J, Butler C. 1984. Children’s conceptions of writing. In H. Cowie, editor. The Development of Children’s Imaginative Writing. London: Croom Helm.

- Wray D. 1994. What do children think about writing? Educational Review. 45(1):67–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191930450106.

Appendix 1

Table 1.1. Comparison of 2016 and 2018 criteria for meeting the expected standard.

Appendix 2.

Data elicitation materials

1. Focus groups questions

[NB: The Focus groups included questions on writing and the ‘gender-gap’ in schools; only the questions specific to writing constructs have been included here]

Education leads’ focus group questions

GENERAL QUESTIONS ABOUT WRITING

Can you tell us what ‘good writing’ means for you in a primary school context?

What specific characteristics of ‘good writing’ would you expect to see in a child’s writing at the end of primary school (key stage 2)?

What are your key concerns about children’s writing in primary schools at the moment, particularly in Liverpool schools? How are these being addressed/how do you think these should be addressed?

Teachers’ focus group questions

GENERAL QUESTIONS ABOUT WRITING

What characteristics of ‘good writing’ would you expect to see in a child’s writing at the end of primary school (key stage 2)?

What are the aspects of writing do year 6/primary school children find most difficult? How do you attempt to address these challenges in your school?

What are the aspects that you think need to be given more emphasis in the teaching and learning of writing in school?

How much emphasis do you place on handwriting vs computer-based writing in your school? Are there any issues with this in terms of children’s writing?

2. Children’s survey questions

Children’s thoughts about writing

We are interested in what you think about writing. Please complete the following questions about your writing.

Whose class are you in?

Teacher 1

Teacher 1 Teacher 2

Teacher 2Which gender are you?

Girl

Girl Boy

Boy Prefer not to say

Prefer not to sayWhat makes a good piece of writing?

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

4.

6. What is your favourite genre of writing?

Fiction

Fiction Poetry

Poetry Non- fiction

Non- fiction7.

8. Is there anything you find challenging when writing? Please explain below.

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________