Abstract

As an increasing number of multilingual children are enrolled in European schools, it is important to gain more insight into teachers’ attitudes towards multilingual approaches in education. The goal of this study is to investigate the attitudes of primary school teachers in Greece, Italy and the Netherlands, three countries that have a highly multilingual student population but differ with respect to the migration context and language policies. Using an online questionnaire, we assessed teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism in the school environment and their adherence to monolingual ideals. We aimed to compare the three countries and investigate which factors related to the teachers’ background and school characteristics predict teachers’ beliefs. The results suggest that teachers in Greece are significantly more positive towards multilingualism than teachers in Italy and the Netherlands, despite great individual variation. Moreover, for all three countries, we found that having received training on multilingualism had a positive effect on teachers’ attitudes. In the Netherlands, we found that teachers who taught a greater proportion of multilingual students on average showed more positive attitudes towards multilingualism. We discuss the implications of these findings for educational language policy, highlighting the importance of evidence-based training on multilingualism for all teachers.

Introduction

In many schools across Europe and in the rest of the world, the student population has become highly multilingual. Several migration processes during the last 50 years have led to culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms, with students speaking different languages at home. In the research community, the benefits of growing up with more than one language and the advantages of multilingual teaching approaches have been widely acknowledged (e.g., García and Wei Citation2015). Yet, teachers’ beliefs are often still based on a monolingual standard, and on outdated, negative views on multilingualism. These beliefs tend to be linked to persistent myths, such as the idea that bilingualism confuses children, and they lead to negative attitudes towards the use of other languages at school (see Bosch and Foppolo Citation2024; Olioumtsevits et al. Citation2024). As a result, teachers may discourage or even prohibit the use of other languages in class (e.g., De Angelis Citation2011; Pulinx et al. Citation2017).

Teachers have a fundamental role in the creation of an inclusive classroom environment that acknowledges the full identity of the students; therefore, their attitudes towards multilingualism matter. Moreover, teachers with positive views about multilingualism tend to have higher levels of trust in their multilingual students (Pulinx et al. Citation2017) and a higher sense of self-efficacy when teaching second language (L2) learners (Karabenick and Noda Citation2004). Students’ performance is positively correlated with both teachers’ expectations (Rosenthal and Jacobson Citation1968) and self-efficacy (Klassen and Tze Citation2014). As such, teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism may directly and indirectly influence their students’ well-being as well as academic outcomes.

The present study investigates primary school teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism, and specifically their ideas about the inclusion of students’ native languages at school. We conducted the study in Greece, Italy and the Netherlands, three European countries where teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism have not yet been investigated extensively. All three countries have a greatly multicultural and multilingual student population, but they differ with respect to the specific migration context, the socio-political climate and current educational language policies.

Before turning to our research questions, we will first present an overview of previous research on teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism and of the migration context and educational language policies in the three countries under investigation.

Previous research on teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism

During the past decades, several studies have investigated teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism and the inclusion of students’ native languages in the school environment, as well as the factors that influence teachers’ beliefs. Considering international comparative research, De Angelis (Citation2011) investigated the beliefs of secondary school teachers in Italy, Austria and the UK, three countries that have traditionally adhered to a monolingual habitus, despite increasingly multilingual student populations. She found that, even though teachers across countries showed some awareness of the benefits of multilingualism and the importance of first language (L1) maintenance, they still believed in some persistent misconceptions, such as the idea that using the native language will confuse students and that it will hinder the acquisition of the majority language. Perhaps as a result, a notable proportion of the respondents stated that they do not allow students to speak their native language in class (64.3% in Austria; 25.5% in Italy; 26.7% in the UK). Focusing on Italy, a more recent study found that Italian secondary school teachers held negative attitudes regarding foreign or non-standard accents, which were strongly correlated with their views on multilingualism and multiculturalism (Nodari et al. Citation2021).

Using the same materials as De Angelis (Citation2011), Mitits (Citation2018) compared the attitudes of primary and secondary school teachers in Greece, which has attracted many migrants during the last decade due to its geographical location at the border of Europe. Again, the results showed that teachers recognized the value of speaking different languages, but they were nevertheless reluctant to integrate pupils’ L1s into their own teaching practice. Primary school teachers, who tend to have a stronger pedagogical background and less pressure to follow a rigid curriculum, were significantly more likely to feel responsible for students’ L1 maintenance than secondary school teachers. Both in primary and secondary education, teachers who were working in schools targeting minority students were more likely to recognize the importance of L1 maintenance, as was the case for teachers with less teaching experience, most likely due to their more recent and presumably more up-to-date training.

Another important study on teachers’ attitudes towards multilingual and monolingual practices in secondary education was conducted by Pulinx et al. (Citation2017) in Flanders, a Dutch-speaking region in Belgium, a country where French and German are the other official languages. Recent educational language policies in Flanders tend to be based on a strictly monolingual ideology, which may at least partly be explained by processes of sub-state nation building and the region’s desire to consolidate a Flemish identity, despite the presence of an increasingly large number of people with a migration background. The results of this study showed that Flemish teachers strongly adhered to monolingual ideals, displaying very negative attitudes towards the use of other languages within the school environment. For example, 77.3% believed that multilingual students should not be allowed to use their native language at school and 29.1% even agreed that it would be in their own interest if they were punished for doing so. In contrast, only 6.8% believed that multilingual students should have the opportunity to learn their home language at school. Teachers’ beliefs were significantly related to the ethnic composition of the school, with monolingual attitudes being the strongest in schools with a mixed student population, compared to schools in which there were almost exclusively or almost no students that belonged to an ethnic minority. Furthermore, female teachers were more positive towards multilingualism than male teachers.

In a partial replication of the study by Pulinx et al. (Citation2017), Rinker and Ekinci (under review, see Baumgartner et al. Citation2018) focused on secondary school teachers in Germany, a country that has been a popular destination for migrants since the second half of the 20th century. As a result, German society is characterized by great cultural and linguistic diversity, despite the fact that German is the only official language (Adler and Beyer Citation2018). Rinker and Ekinci’s results show that German teachers adhered significantly less to monolingual ideals compared to the teachers in Flanders tested by Pulinx et al. (Citation2017), although on average they were still not very positive about multilingual practices in education. Female teachers again showed more positive attitudes than male teachers. In addition, teachers who had a multilingual background themselves tended to express more positive beliefs about multilingualism (Rinker and Ekinci, under review; see Baumgartner et al. Citation2018).

A similar, relatively moderate stance towards multilingualism in education was observed among students of teacher-education programs in the Netherlands, another European country that is characterized by immigration (Robinson-Jones et al. Citation2022). In that study, 60% of pre-service teachers believed that it made sense for teachers to encourage pupils to use their entire linguistic repertoire. Yet, 72% still believed that students should only speak Dutch in class, even among themselves. This contradictory finding suggests a difficulty in translating inclusive ideals and abstract knowledge to multilingual practices in the classroom. As suggested by Duarte and Günther-van der Meij (Citation2022), teachers might need positive practical experiences and time to engage with new ideas in order to develop truly positive beliefs about the use of students’ home languages in the classroom.

Three studies conducted in different Northern European countries which have also attracted many migrants have revealed considerably more positive teacher attitudes towards multilingualism. Søndergaard Knudsen et al. (Citation2021) found that Danish primary school teachers valued multilingualism and demonstrated awareness of the importance of L1 maintenance and a sense of responsibility for children’s bilingual development. A reason for this may be that courses addressing the education of children with different language backgrounds are a compulsory part of the teacher training curriculum. Two other studies also found relatively positive multilingual mindsets among teachers in Sweden (Lundberg Citation2019) and Finland (Alisaari et al. Citation2019). These studies showed that, overall, teachers tended to be positive about multilingualism and well-aware of recent pedagogical concepts such as translanguaging. Yet, some teachers still expressed skeptical views based on monolingual ideologies, specifically regarding the use of students’ native languages for learning, which may hinder the implementation of multilingual educational language policies (Alisaari et al. Citation2019; Lundberg Citation2019). Additionally, Lundberg (Citation2019) found more positive beliefs about multilingualism in female teachers and in teachers working in urban rather than rural areas, while Alisaari et al. (Citation2019) found more positive beliefs in teachers who had more experience teaching L2 learners and in teachers who had received training on ‘linguistically responsive teaching’.

The importance of teacher training has been confirmed by several other studies (e.g., Flores and Smith Citation2009; Mitits Citation2018; Duarte and Günther-van der Meij Citation2022; Pohlmann-Rother et al. Citation2023). These studies consistently show that teachers who have received training about multilingualism, L2 pedagogy or cultural diversity, tend to express more positive attitudes towards multilingualism as well as towards the use of students’ native languages at school and heritage language maintenance. Both pre-service training in the form of university courses and in-service professional training appear to be effective means to improve teachers’ attitudes (Pohlmann-Rother et al. Citation2023).

Altogether, the available literature suggests that teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism are related to many different factors, including individual characteristics of the teacher and of the school in which they work, as well as their students’ linguistic and cultural background. Moreover, there appear to be important differences between different national contexts, which may be related to historical and socio-political factors. Given the latter, the present study will compare the attitudes of teachers in Italy, Greece and the Netherlands. In the next section, we will provide an overview of the national context in each of the three countries under investigation, focusing on historical and current migration developments, socio-political responses and attitudes towards migration, and educational language policies.

The migration context and language policies in Greece, Italy and The Netherlands

Greece, Italy and the Netherlands are all part of the European Union (EU), which is home to 24 official languages in addition to 60 regional minority languages and a great number of non-European languages that have been introduced by migrants. Multilingualism is thus considered a top priority for the EU.Footnote1 Not only does the EU encourage all citizens to acquire at least two other European languages in addition to their native language, policies also acknowledge and value the great linguistic diversity that is present in European societies due to processes of migration. For example, the European Commission emphasizes that first- and second-generation immigrant students should maintain their native language and preferably develop literacy in this language, urging member states to invest in the education of teachers to prepare them for linguistic diversity in the classroom and in research on inclusive, multilingual pedagogy (Dendrinos Citation2018). However, besides an advisory role, the European Union only has limited influence on the development of national language policies, which remain the responsibility of individual member states. With respect to the three focal countries of this study, there are important differences in the specific migration context and current language policies in education, related to various historical and political processes. Each national context will be discussed separately, below.

Migration and language policies in Greece

Due to its position at the South-East border of Europe and its close proximity to Turkey, Greece has been described as one of the gate-ways to Europe (Lamb Citation2016). Greece has experienced a sharp increase in immigration in the last decade, which has changed the student population. Since 2015, over one million migrants and refugees have arrived in Greece, many of whom came from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)), 2022). Earlier immigration processes took place from the 1970s, and specifically during the 1990s, when many people from Albania, other Balkan countries and the former Soviet republics came to Greece (Kasimis and Kassimi Citation2004). In addition to recent immigration, it should be noted that, in the past century, Greece also experienced large-scale emigration, particularly to the U.S. (Fakiolas and King Citation1996).

Public and political narratives regarding the economic consequences of migration have been rather negative in Greece. Other concerns refer to safety issues and threats to ‘Greek identity’ (Dixon et al. Citation2019). Although some evidence suggests that attitudes towards migrants change drastically depending on whether they are expected to stay in Greece in the long term or not (Papataxiarchis Citation2022), the More in Common survey by Dixon et al. (Citation2019) suggests that the majority of the population express some degree of solidarity with migrants. In comparison with other European countries, including Italy and the Netherlands, Greeks report ‘warmer’ feelings towards them. Greek society also appears to be less polarized than other European countries when it comes to migration (Dixon et al. Citation2019).

In 2020, there were approximately 31,000 school-aged children with a migration background in Greece, 13,000 of whom were enrolled in Greek primary and secondary schools (UNICEF Citation2020). Since the first immigration peak in the 1990s, Greece has aimed to follow the EU guidelines regarding linguistic diversity and the rights of students with a migration background. During this time, Greece was still a relatively new EU member state, and educational reforms were implemented to integrate successfully within the European Union (Triandafyllidou and Gropas Citation2007). Starting from 1996, intercultural schools have offered courses on the language and culture of the home countries of students with a migration background. Newly arrived students attend reception classes to learn Greek and to be prepared for the mainstream education program, after which they may attend additional language support classes (Mertzani Citation2023). The new curriculum that was developed in 2021 emphasizes the value of multilingualism. One of the objectives is ‘Multilingual Communication’, which encompasses the use of different languages in class, including students’ home languages, for oral and written language production and comprehension (see Mertzani Citation2023). However, it has been argued that in practice multilingualism is mostly appreciated when it concerns European languages that are associated with economic power, such as English, while the languages of migrant groups continue to have low prestige (Kiliari Citation2009). As a result, ambitious plans of policy makers regarding multilingualism and multiculturalism often fail to reach classrooms (Olioumtsevits et al. Citation2024).

Migration and language policies in Italy

Similarly to Greece, Italy was a country of emigration rather than immigration for most of the previous century (Bettoni and Tamponi Citation2021). Immigration to Italy started in the 1970s, when domestic workers entered the country from Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia, and from several South Asian countries. During the last two decades, the main focus in migration policy has been on the migratory routes from Sub-Saharan and Northern African countries through the Mediterranean Sea, constituting a second important entrance to Europe. Due to the political unrest following the Arab spring movements, this type of migration strongly increased since the early 2010s (Colucci Citation2018).

The prominent media coverage of immigrants arriving in rubber boats at the Italian shores have contributed to the public perception of migration in Italy. This negative framing of migration is closely linked to the rise of the radical right and populist parties, which explicitly appeal to limit migration and foster traditional ‘Italian values’ (Binotto et al. Citation2016; Dixon et al. Citation2018). The More in Common survey conducted by Dixon et al. (Citation2018) shows that many Italians view migration as one of the most serious concerns for their country, mostly because of a fear of losing their cultural identity, perceptions of unsafety, and weak prospects on the job market. Such negative attitudes go hand in hand with ‘deeper concerns about integration’ (p. 5). Nevertheless, their results suggest that most Italians support the principle of asylum and that in Italy there is still more support for human rights groups than for extremist nationalist groups.

As a consequence of increased immigration, between 2010 and 2019 there was a 357% increase of pupils with a migration background in Italy; official records by the Italian Ministry of Education report that in the school year 2019–2020 they accounted for 12% of the student population (MIUR - Ufficio Statistica e Studi 2021). Despite the cultural and linguistic diversity that is currently present in many schools, the main legislation document of reference remains the Immigration Law released in 1998 (specifically, Law 40/1998 and legislation 286/1998, art. 38–39), which specifically addressed the right for non-Italian minors to enter the public school system. Since then, the Italian government has released very few policy statements regarding multilingualism in education. According to the guidelines released in 2014 by the Italian Ministry of Education (MIUR Citation2014), newly arrived migrant children should be fully immersed in mainstream education to favor the natural linguistic development of Italian and interaction with Italian-speaking peers, while they should be offered adaptations of didactic materials to overcome language barriers, as well as additional Italian classes. Moreover, it is emphasized that linguistic diversity should be valued, for example by giving visibility to different languages in the school environment or by teaching students’ native languages outside of school hours. Note, however, that these are considered general suggestions rather than specific protocols. It remains unclear to what extent teachers and school leaders are aware of such recommendations, and if and how they implement them in educational practice (Nodari et al. Citation2021).

Migration and language policies in The Netherlands

The Netherlands has a relatively longer recent history of immigration, starting with migration from former colonies (Indonesia during the 1950s and Surinam during the second half of the 1970s). Another important migration process consists of the ‘guest workers’ who were actively recruited from the Mediterranean area during the 1960s, and the family members of Turkish and Moroccan migrant workers who arrived due to family reunification and family formation processes in the following decades. Since the 1990s, when migration policies became more restrictive, most migrants who enter the Netherlands are citizens from other EU member states, highly skilled workers and asylum seekers (van Meeteren et al. Citation2013).

Up until the 1980s, the public opinion regarding migrants tended to be relatively positive, and the Dutch prided themselves on being tolerant and open-minded (Zwaan Citation2021). Since then, political and public narratives have gradually become more negative and more divided, as the challenges of a multicultural society became apparent. Moreover, the topic of migration became closely intertwined with concerns regarding segregation and fears about Islam posing risks to ‘Dutch cultural identity’ (Zwaan Citation2021). During the last two decades, radical right-wing politicians have successfully exploited these sentiments, and mainstream parties have become increasingly critical of migration. At the same time, however, many Dutch people still display openness to multicultural ideals. Dutch society is currently extremely polarized with respect to migration, with 16.5% expressing anti-migrant attitudes, 31.8% moderately critical attitudes, 33% moderately lenient attitudes and 18.7% pro-migrant attitudes (Albada et al. Citation2021).

At the moment, approximately 30% of Dutch primary school pupils have a migration background (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS), Citation2021). Like in Greece, newly arrived migrant students typically attend reception classes, where they learn Dutch and are prepared for mainstream education (Onderwijsraad Citation2017). However, the large majority of students with a migration background are second generation migrants (CBS, Citation2021). During the 1980s and the 1990s, language policies in education were relatively open to linguistic diversity, mirroring the multicultural and inclusive mindset that characterized the preceding decades. For example, students with a migration background had the right to receive government-funded courses in their own language and culture. Due to concerns about cultural segregation and attainment gaps between students with and without a migration background, these programs were abandoned in 2004, as the focus shifted more and more to supporting the development of Dutch language skills and a monolingual ideology became the norm (Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal Citation2004; Bjornson Citation2007).

Recently, there seems to be a new focus on multilingualism in education. Some local governments, such as the municipality of Amsterdam, actively encourage schools to embrace multilingualism (Gemeente Amsterdam Citation2023). Incorporating multilingualism in education is also one of the core objectives of the new curriculum that is currently being developed. According to these plans, linguistic diversity should be valued and incorporated in the program, so that students can develop multilingual and meta-linguistic awareness, and use their entire linguistic repertoire for learning, whilst feeling at home at school (SLO Citation2023). This ongoing ‘multilingual turn’ has not reached all classrooms, since many teachers, school leaders, politicians and policy makers remain convinced that Dutch should be the only language used at school.

Summary

The three countries under investigation all have multicultural and multilingual student populations, and they are all advised by the European Commission to support the native language development of first- and second-generation immigrant students and to prepare teachers for linguistic diversity in the classroom. In all three countries, translating policies to educational practice appears to be a challenge. Yet, there are also some important differences among the three national contexts that should be considered. Specifically, Italy and Greece are both considered ‘gateways’ to Europe, which means that large numbers of migrants have crossed their borders in the last decade, not only as a destination but also as a means to access other European countries. In contrast, the Netherlands is mostly a destination country with a longer history of immigration compared to Italy and Greece. While the socio-political debate surrounding migration is hardening in all three countries, the public opinion in Greece appears to be less polarized than in Italy and the Netherlands (although even in Greece attitudes have become more negative when the possibility that migrants remain in the country is taken into consideration).

Moreover, there are some important differences in language policy. Whereas the Netherlands and many other European countries have increasingly put more emphasis on integration and assimilation during the last decades, the tendency in Greece has been in the opposite direction, with educational language policies becoming more focused on inclusion and appreciating diversity. In comparison, Italy is mostly characterized by the limited availability of language policies in education which, in addition, mostly remain on a theoretical level, with minimal practical implementation in the classroom. Additionally, in contrast to Greece and the Netherlands, there are no reception classes for newly arrived migrant children in Italy, which means that this group is immediately integrated in the mainstream education system. All these differences in the migration context, the socio-political climate and current language policies may influence teachers’ personal attitudes towards multilingual approaches in education.

Research questions

This study aims to investigate the attitudes of primary school teachers in Italy, Greece and the Netherlands. As discussed in the previous section, all three countries have a highly multilingual student population, but they differ with respect to some crucial factors. We consider a wide range of possible individual variables that may predict teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism. We employ a close adaptation of the survey that has been used by Pulinx et al. (Citation2017) and by Rinker and Ekinci (under review, see Baumgartner et al. Citation2018), so that our results can be compared to other studies conducted in different countries. Since most studies on this topic have focused on secondary schools, we have decided to shift our attention to primary schools.

Our research questions are as follows:

How do teachers in Italy, Greece and the Netherlands view multilingualism and more specifically the inclusion of students’ native languages in the school environment?

Which factors influence teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism? Are attitudes affected by country, teachers’ age, (L2) teaching experience, the proportion of multilingual students in the classroom, the size of the city the teachers work in, training on multilingualism, and whether teachers are multilingual themselves or not?

Methods

Participants

We recruited our respondents online by contacting schools directly, through teacher training programs and through social media platforms (e.g., Facebook groups for teachers). All participants were primary school teachers from different areas in Italy, Greece and the Netherlands, excluding bilingual regions. Teachers who had experience working in bilingual or international schools were not included in the sample.

The final sample consisted of 421 respondents in total (165 in Greece, 143 in Italy and 113 in the Netherlands). Most teachers in Italy were from the North (35% Lombardy, 19% Piedmont, 14% Veneto), most teachers in Greece were from Central Macedonia (79%), and most teachers in the Netherlands were from the South-Holland (46%) and North-Holland (20%) regions. Our sample included teachers working in urban as well as rural areas (45% in Greece, 35% in Italy and 49% in the Netherlands were working in cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants). In all three countries, the large majority of our respondents were working in public schools (96% in Italy, 99% in Greece and 99% in the Netherlands). We observed some differences between the three countries with respect to teachers’ level of education: in Greece and the Netherlands, almost almost all of the teachers that responded to our questionnaire had a degree in higher education, while only about half of the Italian respondents did. This difference is mainly due to different teaching prerequisites in the three countries: in Italy, a university diploma was not required for teaching in primary schools prior to 1990.

Based on the teachers’ responses, in each of the three countries the presence of multilingual students in their classrooms varied greatly; on average, 27% of the pupils in Greece (SD = 32%, Range = 0–100%), 28% in Italy (SD = 27%, Range = 0–98%) and 26% in the Netherlands (SD = 23%, Range = 0–100%) were multilinguals. When teachers were asked about the most common native languages of their multilingual students, the languages that were mentioned most often were Albanian and Arabic in Greece, Arabic and Spanish in Italy, and Moroccan (i.e., Arabic or Berber) and Turkish in the Netherlands. A total of 91% of the teachers in Italy, 81% of the teachers in the Netherlands and 58% of the teachers in Greece indicated that they had experience teaching L2 learners. In contrast, only 30% in Italy, 53% in the Netherlands and 58% in Greece reported having received professional training on multilingualism. Note that 20% of the teachers in Greece and 5% of the teachers in the Netherlands were teaching in reception classes for newly arrived migrant children, in which they provide intensive language support to prepare children for the mainstream education system. presents additional background information about our participants.

Table 1. Background data of participants.

Materials and procedure

For the purposes of the current study, participants completed an online survey in which they were asked to respond to a set of seven statements, aiming to examine their attitudes towards multilingualism within the school environment and their potential adherence to monolingual ideals. These statements, which can be found in “Results” section (), were taken from Pulinx et al. (Citation2017) and slightly adapted to make them more suitable for the primary school context. The seven items yielded an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha of .72. Teachers were also asked several background questions regarding properties of the school in which they were working, as well as their personal characteristics (including their age, gender, language background, teaching experience, education and training on multilingualism). The background questions were based on the survey by Rinker and Ekinci (under review, see Baumgartner et al. Citation2018).

Table 2. The proportion of teachers that responded ‘agree’ or ‘completely agree’ to the seven statements.

The survey was translated into Italian, Greek and Dutch, and for each language, the translation was checked by at least two other native speakers. The survey was distributed between February 2021 and May 2022 using the online platforms Qualtrics (in Italy and the Netherlands) and LimeSurvey (in Greece). The project has been approved by the ethics committee of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the University of Milan-Bicocca. Before starting the survey, which took approximately 15–20 minutes, respondents were asked for their informed consent.

Analysis

Firstly, we analyzed the responses to the statements addressing attitudes towards multilingualism at school. For each statement we calculated the proportion of teachers that responded ‘agree’ or ‘completely agree’, in order to descriptively compare the three countries, also in relation to the results reported by Pulinx et al. (Citation2017) and Rinker and Ekinci (under review, see Baumgartner et al. Citation2018). Secondly, we calculated a ‘Multilingual-Monolingual Attitude Index’ (henceforth, MMAI), following the procedure described in Pulinx et al. (Citation2017). Based on the seven statements (), two of which were reverse-coded, we computed an average score from 1 to 5 for each participant. A score of 1 referred to extremely positive attitudes towards multilingualism (i.e., a fully multilingual mindset), while a score of 5 referred to extremely negative attitudes towards multilingualism (i.e., a fully monolingual mindset).

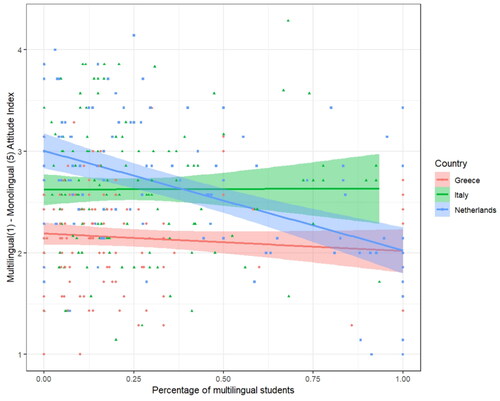

Using a stepwise regression model comparison, we then aimed to test whether attitudes towards multilingualism (i.e., the MMAI) could be predicted by country, teachers’ age, teaching experience, experience teaching L2 learners, whether teachers had received training on multilingualism or not, whether teachers were multilingual or monolingual themselves, the proportion of multilingual students in the classroom, and the size of the city in which the school was located (more or less than 100,000 inhabitants). Continuous predictors were rescaled and centered around the mean. When testing the main effect of country, Greece was coded as −2/3 and Italy and the Netherlands were each coded as 1/3, since a visual inspection of the data revealed that teachers in Greece overall patterned differently from teachers in the other two countries. When testing the interaction with the proportion of multilingual students, the Netherlands was coded as 2/3 while Italy and Greece were each coded as −1/3, because the plotted data suggested that this variable had an effect only in the Netherlands. For training on multilingualism, ‘yes’ was coded as −1/2 and ‘no’ was coded as +1/2. The statistical analysis was conducted in R (R Core Team Citation2022).

Results

presents a descriptive overview of teachers’ responses to the seven statements exploring their attitudes towards multilingualism at school. The data are presented for each country separately, showing the percentage of teachers that responded ‘agree’ or ‘completely agree’.

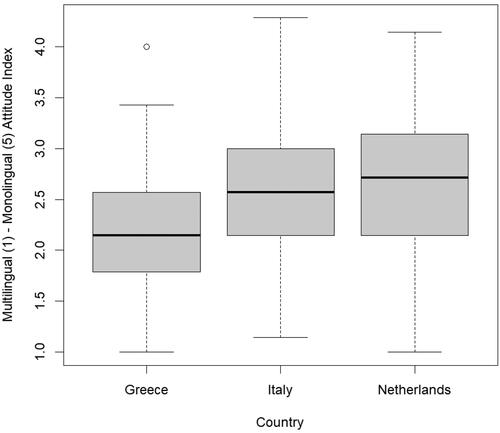

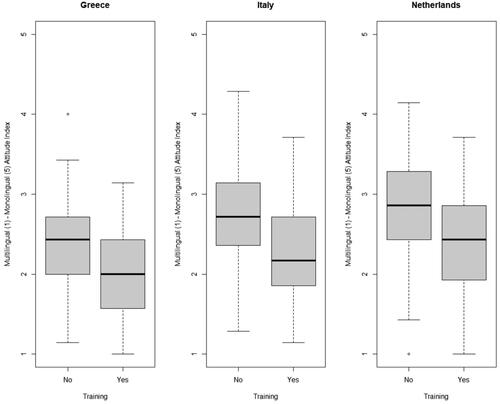

The best regression model to predict teachers’ MMAI included an interaction and main effects of country and proportion of multilingual students, as well as a main effect of training on multilingualism, while the other predictors (i.e., age, teaching experience, experience in L2 teaching, personal language background, and city size) did not improve the model fit.

The results of the model (R2Adjusted = 23.5) showed that respondents in Greece on average had a significantly lower MMAI, indicating more positive attitudes towards multilingualism, compared to respondents in Italy and the Netherlands (β = .448, p < .0001). This is illustrated by . There was also a significant main effect of training, indicating that, in all three countries, teachers who had received training on multilingualism had more positive attitudes (β = .328, p < .0001). The effect of training per country is shown in .

Figure 1. The MMAI per country. A lower index indicates more positive attitudes towards multilingualism.

Figure 2. The MMAI per country for teachers who received training on multilingualism versus teachers who did not receive such training. A lower index indicates more positive attitudes towards multilingualism.

We also found a significant interaction between country and proportion of multilingual students (β = −.222, p = .0005), showing that in the Netherlands, but not in Italy and Greece, teachers who had more multilingual students in their classroom tended to have more positive attitudes than teachers with less multilingual students. This is illustrated by .

Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate primary school teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism and the use of different languages in the school environment. We compared the beliefs of teachers living and working in Italy, Greece and the Netherlands, three countries in which a high proportion of pupils grow up with more than one language. Moreover, our goal was to investigate which individual factors are related to teachers’ attitudes, considering their age, teaching experience, experience in L2 teaching, professional or academic training on multilingualism, personal language background, the proportion of multilingual students in the classroom, and the size of the town in which the school was located.

Our results showed great variation in teachers’ attitudes. On the one hand, some teachers are fully supportive of multilingual approaches. They believe that native language development should be supported, for example by giving students the opportunity to study their native language at school or by providing books in different languages. On the other hand, there is still a substantial number of teachers who take a much more negative stance. These teachers tend to believe that multilingualism is a difficulty to overcome, and some of them even prohibit the use of students’ native languages at school. This large variation was present in all three countries, reflecting high levels of polarization in the current socio-political climate. While previous research found more positive attitudes for teachers working in cities (Lundberg Citation2019 in Sweden), teachers who belong to an ethnic or linguistic minority themselves (Flores and Smith Citation2009 in the US; Rinker & Ekinci, under review in Germany), and teachers who have less teaching experience and thus more recent training (Mitits Citation2018 in Greece), we found no such effects in our study.

However, we observed some interesting differences among the countries under investigation. Teachers in Greece showed overall more positive attitudes towards multilingualism than teachers in Italy and the Netherlands. This might be related to several factors. Firstly, our results could be explained in terms of differences in the current socio-political climate in the three countries. Whilst the radical right has become dominant in both Italy and the Netherlands, with high levels of polarization and increasing resistance against multiculturalism, the public opinion appears to be less sharply divided in Greece, where levels of interpersonal trust remain relatively high (Dixon et al. Citation2018, Citation2019; Zwaan Citation2021). Moreover, Greeks tend to have warmer feelings towards migrants compared to people in many other European countries, including Italy and the Netherlands (Dixon et al. Citation2019). During the last decades, educational language policies in Greece have also put more emphasis on the value of multilingualism and multiculturalism (Mertzani Citation2023). Secondly, the population of multilingual children may differ across the three countries. In Greece, this group consists, for a large part, of children with a recent migration background, which means that teachers may be more willing to make space for students’ native languages. This may not hold to the same extent for Italy and the Netherlands, where a greater proportion of multilingual students is likely to be born and raised in the country of residence and therefore expected to be able to use the majority language at school. Many teachers in Greece were also teaching in reception classes for children with a migration background. As a result, they may have more direct experience with newly arrived L2 learners, and they may have a better idea of how both students and teachers can benefit from the use of various native languages at school. Teachers working in reception classes may also have received more specific and perhaps more up-to-date training regarding multilingualism. Thirdly, the observed difference between Greece and the other two countries may be related to a difference in the teachers’ level of education. Teachers in Greece were more highly educated than teachers in the other two countries; all of them had attended university and over two thirds had obtained a postgraduate degree. This might also be correlated with training on multilingualism; it is possible that the topic of multilingualism is addressed more frequently or more profoundly in post-graduate courses compared to undergraduate courses.

Indeed, training on multilingualism turned out to be a robust predictor of teachers’ attitudes. In all three countries, teachers who had received specific training on multilingualism at university or during their career turned out to be more positive towards the use of other languages at school than teachers who had received no such training. This corroborates previous findings that show the effectiveness of teacher training, coming from studies conducted in the U.S. (Flores and Smith Citation2009), Greece (Mitits Citation2018), Finland (Alisaari et al. Citation2019), Germany (Pohlmann-Rother et al. Citation2023) and the Netherlands (Duarte and Günther-van der Meij Citation2022).

In the Netherlands, we also found that greater proportions of multilingual students in a classroom were associated with more positive attitudes towards multilingualism, possibly because positive experiences with diversity might increase inclusive perspectives and appreciation of differences (Shim and Perez Citation2018). Moreover, working in highly multilingual classrooms may allow teachers to develop the necessary tools and skills to deal with linguistic diversity, which may in turn make them less apprehensive about multilingual approaches in education. However, we did not find this effect in Italy and Greece, which might be related to the distribution of our data (see ). While in the Netherlands the proportion of multilingual students in a teachers’ classroom was quite evenly distributed between 0% and 100%, in Italy and Greece the majority of our participants clustered below 50%. As such, an effect of linguistic diversity of the student population might have surfaced only in the data collected in the Netherlands.

A similar correlation between the degree of cultural and ethnic diversity of the students and teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism was found by Flores and Smith (Citation2009), who focused on primary, secondary and high school teachers in Texas in the U.S. Pulinx et al. (Citation2017) also found that Flemish secondary school teachers’ attitudes were related to the ethnic composition of the school, although this relationship was less straightforward. In their study, teachers working in schools with a mixed student population had more negative views about multilingualism than teachers working in schools in which most students belonged to an ethnic minority as well as in schools in which there were almost no ethnic minority students. The authors argue that feelings of threat are most intense in contexts in which there are different ethnic groups of similar sizes without the presence of a dominant group. Our findings, however, do not show the same pattern; in the Netherlands, more linguistic diversity was associated with more positive attitudes, while in Italy and Greece we found no relationship between teachers’ attitudes and the linguistic background of the student population.

When comparing our results to the findings of Pulinx et al. (Citation2017) in Flanders, Belgium, and Rinker and Ekinci (under review) in Germany (see Baumgartner et al. Citation2018), we also observe some other notable differences. Firstly, the attitudes of the Greek teachers in the present study were considerably more positive with respect to multilingualism and the use of other languages in the school environment. As discussed above, the current migration processes taking place in Greece may have positively affected teachers’ attitudes, since many of them are teaching in reception classes and because the topic of multilingualism may have received more attention in their recent training. Secondly, the attitudes of the Dutch and Italian teachers were comparable to those of the German teachers in the study by Rinker and Ekinci (under review), while their attitudes were on average more positive than those of the Flemish teachers in Pulinx et al. (Citation2017).

This could partially be explained by sociocultural, political and historical differences in the national contexts of these countries. In the context of Flanders, for example, multilingual approaches and the inclusion of students’ native languages in education were relatively common during the last decades of the 20th century, but over time a policy shift has been taking place, in which such multilingual programs have gradually been abandoned (Pulinx et al. Citation2017). A similar process has been taking place in the Netherlands (Bjornson Citation2007). As Pulinx et al. (Citation2017) point out, one important factor influencing such policy shifts may be the recent attention to international comparative assessments of learning outcomes, such as the PISA or PIRLS research programs, which increased the emphasis on improving students’ proficiency in the language of schooling. Another factor may be the need to consolidate a national identity, including a common language and culture, in response to societies that are becoming more and more multicultural. This desire may be even stronger in Flanders than in the Netherlands, due to historical linguistic tensions between the Dutch- and French-speaking parts of Belgium, as well as the continuous efforts to increase the region’s autonomy at a cultural, economic and political level (see Pulinx et al. Citation2017). As a result, teachers in Flanders might be more likely to adhere to monolingual ideals, compared to the teachers in the current study.

However, the differences between our findings and the results of previous research may also be explained by the fact that our participants worked in primary schools, while Pulinx et al. (Citation2017) and Rinker and Ekinci (under review) tested secondary school teachers. Focusing on Greece, Mitits (Citation2018) found that primary school teachers were significantly more likely to feel responsible for the L1 development of their students than secondary school teachers. A reason for this may be that teachers in secondary schools often have received less pedagogical training than their colleagues in primary schools, while at the same time they usually are under greater pressure to follow a fixed curriculum and meet specific learning objectives. Moreover, any differences between primary and secondary school teachers might be intertwined with an effect of gender, since female teachers are overrepresented in primary schools in these countries, while the gender division tends to be more equal in secondary schools. Several studies have shown that on average female teachers have more positive attitudes towards multilingualism than male teachers (Pulinx et al. Citation2017; Lundberg Citation2019; Rinker and Ekinci, under review), which might be related to the well-attested observation that men are more likely to vote for (radical) right-wing and populist parties than women, possibly due to differences in socialization between boys and girls (Spierings and Zaslove Citation2017). In order to make a better and more complete comparison with previous research, future studies could therefore focus on both primary and secondary school teachers, aiming for a more equal distribution of men and women, possibly also including questions on political orientations and general attitudes towards migration.

It should be noted that teachers’ beliefs about the inclusion of students’ home languages at school may also be related to socio-political hierarchies of languages, social status and stereotypes about the speakers of those languages. Several studies taking a qualitative approach have shown that teachers in European contexts tend to view multilingualism as an asset when it concerns prestigious European languages, appreciating the benefits of bilingual education, while they often fail to value linguistic diversity when considering minority languages that are spoken by their students with a migration background (Young Citation2014; Putjata and Koster Citation2023). In a related project, largely based on the same participants as in the current study, we presented teachers in the Netherlands (Bosch and Doedel Citation2024) and in Italy and Greece with a fictional scenario in which we manipulated the name, country of origin and native language of a child, aiming to test whether teachers would be more accepting of high-prestige European languages compared to the languages of immigrants. Whilst we found great variation among teachers in all three countries, we did not find a significant effect of language status. However, we observed some interesting differences among the three countries. Teachers in Greece were most likely to allow L1 use at school, both during class time and during the break, followed by teachers in Italy, while teachers in the Netherlands were most apprehensive. In the Netherlands, there was a positive correlation with the degree of linguistic diversity in the student population, and in both Italy and the Netherlands, teachers who had received training on multilingualism were more open towards L1 use at school. These results largely align with the findings of the current study, highlighting the importance of providing teachers with adequate training on multilingualism.

This study has two limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, our samples are relatively small and not fully representative. Most of the responses to our survey came from a few regions, so we should be cautious when generalizing our findings. For example, in Italy, there are considerable cultural and political differences between the North and the South, which may influence attitudes towards multilingualism. This issue could be addressed by carefully balancing the regional distribution of participants or by defining more specific target regions, as well as by recruiting participants on a large scale in close collaboration with (regional) governments or educational institutions to reach a wider range of teachers. Secondly, teachers’ beliefs do not equal their practices. Even if teachers have positive attitudes and up-to-date knowledge, they may not have the necessary tools or institutional support to implement multilingual approaches in their own teaching. Future research should address this ‘knowledge-action gap’, by investigating teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in relation to educational policies and their actual teaching practices.

Conclusions and implications

Due to various migration processes, European schools have become more multicultural and multilingual. Yet, teachers are not always prepared for teaching in diverse classrooms, as monolingual ideals often still serve as the starting point. Focusing on primary school teachers in Greece, Italy and the Netherlands, this study found great individual variation in all three countries. While some teachers were very positive about multilingual approaches and native language support at school, others showed more negative attitudes, maintaining that the use of minority languages at school should be avoided. On average, teachers in Italy and the Netherlands adhered more strongly to monolingual ideals than teachers in Greece. In the Netherlands, teachers who taught more multilingual students tended to express more positive attitudes towards multilingualism, suggesting that in some cases exposure to diversity might increase openness to multilingual approaches. Moreover, in all three countries, we found that teachers who had received training on multilingualism showed significantly more positive attitudes towards multilingualism, corroborating previous findings on the effectiveness of training.

Thus, whilst there is a lot of individual variation among teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism, which may be influenced by the socio-political context and educational language policies of the country in which they work, our results underline that teacher training on multilingualism may be an effective way to create more openness to inclusive approaches in education. Training opportunities on multilingualism, L2 learning and translanguaging should be implemented both as obligatory pre-service courses at university and as continuous education courses for in-service teachers. It is important that these programs are offered at all schools, including schools in which multilingual children are a minority. Finally, there should be a close collaboration between the education field and researchers, to create evidence-based training programs and educational language policies that are informed by up-to-date knowledge about multilingualism.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of our respondents for their participation, the attendants of the final conference of the MultiMind project for their valuable comments, and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on an earlier version of this paper.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data set on which this study is based is openly available on: https://osf.io/4bc3k/?view_only=33e22a3e71da4653946a9147caadd24d.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Adler A, Beyer R. 2018. Languages and language policies in Germany/Sprachen und Sprachenpolitik in Deutschland. In G. Stickel, editor. National language institutions and national languages. Contributions to the EFNIL Conference 2017 in Mannheim. Hungarian Academy of Sciences; p. 221–242.

- Albada K, Hansen N, Otten S. 2021. Polarization in attitudes towards refugees and migrants in the Netherlands. Eur J Soc Psychol. 51(3):627–643. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2766.

- Alisaari J, Heikkola LM, Commins N, Acquah EO. 2019. Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities: Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teach Teach Educ. 80:48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.003.

- Baumgartner R, Fuchshuber F, Rinker T. 2018. Multilingual classrooms and monolingual mindsets? [Conference presentation]. ECSPM Symposium, Darmstadt. https://ecspm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Vortrag-Rinker_Baumgartner_Fuchshuber-1.pdf.

- Bettoni G, Tamponi I. 2021. Internal geopolitics and migration policies in Italy. In J. Franzke, J. M. Ruano de la Fuente, editors. Local integration of migrants policy: European experiences and challenges. London: Palgrave MacMillan; p. 261–283.

- Binotto M, Bruno M, Lai V. 2016. Tracciare confini. L’immigrazione nei media italiani. Milan: Franco Angeli.

- Bjornson M. 2007. Speaking of citizenship: Language ideologies in Dutch citizenship regimes. Focaal. 2007(49):65–80. https://doi.org/10.3167/foc.2007.490106.

- Bosch JE, Doedel J. 2024. Teachers’ beliefs about multilingual students and their language choice: Exploring the effect of language hierarchies. Dutch J Appl Linguist. https://osf.io/t5uxg/?view_only=b381b23fd80142ee85ce8fd235fad75e.

- Bosch JE, Foppolo F. 2024. Fostering multilingualism to support children’s school success. In J. Franck, F. Faloppa, T. Marinis, editors. Myths and facts about multilingualism. New York: CALEC; p. 139–151.

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS). 2021. Jaarrapport landelijke jeugdmonitor. https://longreads.cbs.nl/jeugdmonitor-2021/jongeren-in-nederland/.

- Colucci M. 2018. Storia dell’immigrazione straniera in Italia. Dal 1945 ai giorni nostri. Rome: Carocci Editore.

- De Angelis G. 2011. Teachers’ beliefs about the role of prior language knowledge in learning and how these influence teaching practices. Int J Multiling. 8(3):216–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2011.560669.

- Dendrinos B. 2018. Multilingualism language policy in the EU today: a paradigm shift in language education. TLC. 2(3):9–28. https://doi.org/10.29366/2018tlc.2.3.1.

- Dixon T, Hawkins S, Heijbroek L, Juan-Torres M, Demoures F. 2018. Attitudes towards national identity, immigration and refugees in Italy. More in Common. https://www.moreincommon.com/media/3hnhssh5/italy-en-final_digital_2b.pdf.

- Dixon T, Hawkins S, Juan-Torres M, Kimaram M. 2019. Attitudes towards national identity, immigration, and refugees in Greece. More in Common. https://refugeeobservatory.aegean.gr/sites/default/files/0535%2BMore%2BIn%2BCommon%2BGreece%2BReport_FINAL-4_web_lr_0.pdf.

- Duarte J, Günther-van der Meij M. 2022. ‘Just accept each other, while the rest of the world doesn’t’–teachers’ reflections on multilingual education. Lang Educ. 36(5):451–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2022.2098678.

- Fakiolas R, King R. 1996. Emigration, return, immigration: a review and evaluation of Greece’s postwar experience of international migration. Int J Popul Geogr. 2(2):171–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1220(199606)2:2<171::AID-IJPG27>3.0.CO;2-2.

- Flores BB, Smith HL. 2009. Teachers’ characteristics and attitudinal beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity. Biling Res J. 31(1–2):323–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235880802640789.

- García O, Wei L. 2015. Translanguaging, bilingualism, and bilingual education. In W. E. Wright, S. Boun, and O. García, editors. The handbook of bilingual and multilingual education. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; p. 223–240.

- Gemeente Amsterdam. 2023. Initiatiefvoorstel voor de raadsvergadering van Blom, Yilmaz en De Fockert, 22 November 2021. https://openresearch.amsterdam/image/2021/12/6/initiatiefvoorstel_d_d_22_november_2021_van_de_leden_yilmaz_denk_blom_en_de.pdf.

- Karabenick SA, Noda PAC. 2004. Professional development implications of teachers’ beliefs and attitudes toward English language learners. Biling Res J. 28(1):55–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2004.10162612.

- Kasimis C, Kassimi C. 2004. Greece: A history of migration. Migration Information Source. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/greece-history-migration.

- Kiliari A. 2009. Language practice in Greece: the effects of European policy on multilingualism. Eur J Lang Policy. 1(1):21–28. https://doi.org/10.3828/ejlp.1.1.3.

- Klassen RM, Tze VMC. 2014. Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: a meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev. 12:59–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001.

- Lamb IA. 2016. The gates of Greece: REFUGEES and policy choices. Mediterranean Q. 27(2):67–88. https://doi.org/10.1215/10474552-3618072.

- Lundberg A. 2019. Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism: Findings from Q method research. Curr Issues Lang Plan. 20(3):266–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2018.1495373.

- Meeteren M, van, van de Pol S, Dekker R, Engbersen G, Snel E. 2013. Destination Netherlands: History of immigration and immigration policy in the Netherlands. In J. Ho, editor. Immigrants: acculturation, socio-economic challenges and cultural psychology. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; p. 113–170.

- Mertzani M. 2023. Linguistic policy in Greece and teacher’s training in question. RDE. 15(37):e15115. https://doi.org/10.28998/2175-6600.2023v15n37pe15115.

- Ministero dell’Istruzione (MIUR) - Ufficio Statistica e studi. 2021. Gli alunni con cittadinanza non italiana A.S. 2019/2020. https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/0/Alunni±con±cittadinanza±non±italiana±2019-2020.pdf/f764ef1c-f5d1-6832-3883-7ebd8e22f7f0?version=1.1&t=1633004501156.

- Ministero dell’Istruzione (MIUR). 2014. Linee guida per l’accoglienza e l’integrazione degli alunni stranieri (prot. 4233). https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/2223566/linee_guida_integrazione_alunni_stranieri.pdf/5e41fc48-3c68-2a17-ae75-1b5da6a55667?t=1564667201890.

- Mitits L. 2018. Multilingual students in Greek schools: Teachers’ views and teaching practices. J Educ e-Learning Res. 5(1):28–36. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2018.51.28.36.

- Nodari R, Calamai S, Galatà V. 2021. Italian school teachers’ attitudes towards students’ accented speech. A case study in Tuscany. Italiano LinguaDue. 13(1):72–102. https://doi.org/10.13130/2037-3597/15857.

- Olioumtsevits K, Franck J, Papadopoulou D. 2024. Breaking the language barrier: why embracing native languages in second/foreign language teaching is key. In J. Franck, F. Faloppa, T. Marinis, editors. Myths and facts about multilingualism. New York: CALEC; p. 164–172.

- Onderwijsraad. 2017. Vluchtelingen en onderwijs; Naar een efficiëntere organisatie, betere toegankelijkheid en hogere kwaliteit. https://www.onderwijsraad.nl/publicaties/adviezen/2017/02/23/vluchtelingen-en-onderwijs.

- Papataxiarchis E. 2022. An ephemeral patriotism: The rise and fall of “Solidarity to Refugees. In M. Kousis, A. Chatzidaki, K. Kafetsios, editors. Challenging mobilities in and to the EU during times of crises: The case of Greece. Berlin: IMISCOE, Springer; p. 163–184.

- Pohlmann-Rother S, Lange SD, Zapfe L, Then D. 2023. Supportive primary teacher beliefs towards multilingualism through teacher training and professional practice. Lang Educ. 37(2):212–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2021.2001494.

- Pulinx R, Van Avermaet P, Agirdag O. 2017. Silencing linguistic diversity: the extent, the determinants and consequences of the monolingual beliefs of Flemish teachers. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 20(5):542–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1102860.

- Putjata G, Koster D. 2023. ‘It is okay if you speak another language, but…’: Language hierarchies in mono- and bilingual school teachers’ beliefs. Int J Multiling. 20(3):891–911. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1953503.

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Rinker T, Ekinci E. under review. Multilingual classrooms and monolingual mindsets? A study on teacher’s beliefs towards migration-related multilingualism.

- Robinson-Jones C, Duarte J, Günther-van der Meij M. 2022. ‘Accept all pupils as they are. Diversity!’–pre-service primary teachers’ views, experiences, knowledge, and skills of multilingualism in education. Sustain Multiling. 20(1):94–128. https://doi.org/10.2478/sm-2022-0005.

- Rosenthal R, Jacobson L. 1968. Pygmalion in the classroom. Urban Rev. 3(1):16–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02322211.

- Shim W-J, Perez RJ. 2018. A multi-level examination of first-year students’ openness to diversity and challenge. J Higher Educ. 89(4):453–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1434277.

- SLO. 2023. Conceptkerndoelen Nederlands en toelichtingsdocument. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2023/09/28/bijlage-2-conceptkerndoelen-nederlands-en-toelichtingsdocument.

- Søndergaard Knudsen HB, Donau PS, Mifsud CL, Papadopoulos TC, Dockrell JE. 2021. Multilingual classrooms—Danish teachers’ practices, beliefs and attitudes. Scand J Educ Res. 65(5):767–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1754903.

- Spierings N, Zaslove A. 2017. Gender, populist attitudes, and voting: Explaining the gender gap in voting for populist radical right and populist radical left parties. West Eur Polit. 40(4):821–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1287448.

- Triandafyllidou A, Gropas R. 2007. European Immigration: a sourcebook. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal. 2004. Wijziging van de Wet op het primair onderwijs, de Wet op de expertisecentra en de Wet op het voortgezet onderwijs, onder meer in verband met de beëindiging van de bekostiging van onderwijs in allochtone levende talen. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/dossier/kst-29019-5.pdf.

- UNICEF. 2020. Access to formal education for refugee and migrant children in Greece. January 2020. https://www.unicef.org/eca/media/12271/file.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. Greece sea arrivals dashboard–June 2022, July 27. https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/94433.

- Young AS. 2014. Unpacking teachers’ language ideologies: Attitudes, beliefs, and practiced language policies in schools in Alsace, France. Lang Aware. 23(1–2):157–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2013.863902.

- Zwaan LJ. 2021. Migration in the Netherlands: threats and opportunities. In J. Franzke, J. M. Ruano de la Fuente, editors. Local integration of migrants policy: European experiences and challenges. London: Palgrave MacMillan; p. 87–105.