ABSTRACT

This article uses archival research to analyse the text, aesthetics and impact of two little poetry magazines of the early 1960s: Poetmeat edited by Dave Cunliffe and Tina Morris, and Jeff Nuttall’s My Own Mag. Building upon previous studies which show the part small press publications played in distributing innovative US verse and the influence that had upon UK poetry, it illustrates how the experimentalism of Poetmeat and My Own Mag contributed to this process. This research builds on my own book Hidden Culture, Forgotten History (2017), James Charnley’s recent Nuttall biography Anything but Dull (2022) as well as the work of art historian Andrew Wilson and academic Gillian Whiteley to argue that the production of these two journals pursued a political as well as a cultural agenda. I contend that little poetry magazines went beyond the dissemination of avant-garde verse, illustrating how the experimentalism carried by the two journals was part of a process which bridged the gap separating different artforms, the development by which conceptualism later came to the fore. Further, it proposes that the cut-ups of William Burroughs were key to this transformation. Finally, the article concludes by raising questions about the behaviour of Cunliffe and Nuttall which may explain their continuing obscurity.

Poetics

According to the poet and editor Jim Burns, the arrival of US mimeographed magazines in Britain and the consequential emergence of UK journals, was key to the development of new forms of verse on this side of the Atlantic. Writing in Geraldine Monk’s CUSP: Recollections on Poetry in Transition (2012), Burns recalls the leading little poetry magazines in which he discovered new verse, publications that he would critique in both the mainstream media and small press and which in turn influenced his own poetic approach:

In 1957 [I] … began to pick up on the new writing which began to filter through from the United States … I think it’s essential to say that the little magazines were of key importance and without them it would have been much harder to find out what was happening and who the most interesting poets were. Publications like Evergreen Review, Big Table, Yugen and The Outsider in America and Migrant, Satis, Outburst, and New Departures in Britain, had an important role to play … .Footnote1

Together with New Departures and Stand, Migrant successfully attempted to liberate British poetry from rigid national boundaries and promoted the reception of international, in particular American, avant-garde poets. These organs paved the way for experimental magazines that were to transform the situation of poetry in Great Britain … including … [Ian] Hamilton Finlay’s Poor. Old. Tired. Horse, Jeff Nuttall’s My Own Mag and Dave Cunliffe and Tina Morris’ Poetmeat.Footnote2

Politics

Born in Blackburn, Lancashire in 1941, Cunliffe was an anarchist with an interest in esoteric religions who later wrote for Total Liberty – a Journal of Evolutionary Anarchism.Footnote4 According to Morris, Cunliffe believed that the artistic and the political were entirely indivisible and it was the role of poetry to provoke readers into questioning how they live.Footnote5 Morris remains a left-leaning environmentalist who, like Cunliffe, believes in the power of humanity’s connection with nature. Morris uses verse, publishing, novels, teaching and activism to promote a message of peace and conservation. In analysing Nuttall’s more complex position, both James Charnley, in his biography Anything but Dull (2022), and Gillian Whiteley in her article ‘Sewing the Subversive Thread of Imagination’, use Nuttall’s seemingly explicit self-declaration of ‘I’m an anarchist’ in the Yorkshire Post in 1971, as evidence of his beliefs.Footnote6 However, this was in response to an accusation of being a communist by a reporter when questioned about his support for a 1971 student protest that year. When interviewed in Jonathon Green’s history of the London counterculture Days in the Life (1988), by contrast, Nuttall described his politics as ‘indecisive … but revolutionary’ and in his own text, Art & the Degradation of Awareness (2001), he recalls his rejected 1992 application to become a member of the British Communist Party.Footnote7 My reading is that Nuttall broadly subscribed to the anarchist position but mainly on the grounds that it gave the perception of complete artistic freedom although, as we shall see, this was largely an illusion. As Whiteley argues, Nuttall: ‘ … emphasised the ways that the creative powers of the imagination – particularly the irrational and affective – could catalyse new political possibilities’.Footnote8

According to Cunliffe, he was introduced to Nuttall, Michael Horovitz and Adrian Mitchell by the poet Lee Harwood and, encouraged by them, began to write his own verse and attend anti-nuclear demonstrations.Footnote9 From the late-1950s Nuttall was involved in the Aldermaston marches, CND and the radical pacifist Committee of 100 (C100) protests which attracted artists and poets who met at London’s Peace Café on Fulham Road, London.Footnote10 According to Nuttall’s account of the early British underground Bomb Culture (1968), this group included Cunliffe, Horovitz, Spike Hawkins, Harwood, Ian Vine, Neil Oram, Pete Brown, Barry Miles and presumably, Nuttall himself.Footnote11 The artist Stephen Willats, who visited the Peace Café regularly in 1959, claims that it was an ‘instrumental vehicle’ in the ‘underground culture of London’ and ‘a meeting point for anarchists, poets, pacifists, and members of the Ban the Bomb Movement’, where he first heard about the work of the artist Gustav Metzger, one of the original C100 signatories.Footnote12

Cunliffe claimed to have been part of a ‘Happening Group’, artists prepared to carry-out provocative actions within C100. Although this collective is not mentioned within histories of the anti-nuclear movement, a letter from Cunliffe in his archive, claims that one of these actions was an ‘Exorcism of War Demons’ at Wethersfield US air base in December 1961, at which he read poetry with Nuttall to summon spirits to see-off the evil of the nuclear weapons within.Footnote13 Poet and activist Richard Wilcocks was involved with the Happening Group but could not recall the involvement of either Cunliffe or Nuttall.Footnote14 However a Happening Group flyer in the Dave Cunliffe Collection at Manchester University’s John Rylands Library contains poetry by both Cunliffe and Wilcocks.Footnote15 Cunliffe and Nuttall were arrested at C100 actions and Cunliffe fled back to Lancashire after detention by the police at a large Trafalgar Square demonstration.Footnote16 The tension the trio felt from living under the threat of the cold war would spark what Nuttall called ‘Bomb Culture’, a form of creative anxiety which would emerge in the textual work of Morris, Nuttall and Cunliffe ().

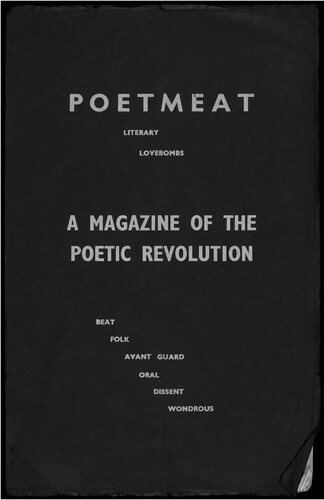

During early 1963, and in response to his feelings of poetic inspiration and nuclear dread, Cunliffe compiled the first issue of Poetmeat on a small press in the front room of his parents’ house in Blackburn, Lancashire.Footnote17 With a plain black cover, it featured the invocation: ‘Poetmeat Literary Lovebombs – A Magazine of the Poetic Revolution – Beat Folk Avant Guard (sic) – Oral Dissent Wondrous’. The editorial clearly sets out how he intended to assault the boundaries of taste in relation to the mainstream media:

Every day, thousands of grubby words, ecstatically (true) describing the sordid acts of murder & violent death, are spewed up by hysterical & irresponsible journalists. Hate words of impotent governments. Lie words of affluent & mercenary politicians. Words of violence, intolerance & exploitation. Yet the great & universal word of the set of love is branded as obscene. Are our poets to be condemned for saying “fuck” or “cunt”? Have we become a sexless & sterile people? Are we oblivious of the joys of love?Footnote18

Poetmeat issue 1 also contained an untitled poem written by Tina Morris which includes the lines:

Whereas Cunliffe’s prose and verse often pushed the boundaries of accepted language and literary convention, the poetic approach of Morris was just as subversive, albeit framed within a more traditional structure. The references here may be a description of the effect of a nuclear attack and perhaps the allusion to ‘Japanese trees’ could be a depiction of destruction in Hiroshimi or Nagasaki. It is also possible that the poem is an early indication of Morris’s more general environmental concerns which would become a core element of Poetmeat. Morris and Cunliffe led meat-free lifestyles, became animal rights activists who picketed butchers and abattoirs and smashed-up shooting lodges on the surrounding Lancashire moors.Footnote21 Morris was reading early scientific warnings about the ecological damage caused by manufacturing processes and pollutants and the fears that this generated were already clear in her poetry.Footnote22

As in Cunliffe’s Poetmeat, the idea of freedom was also central to Nuttall’s artistic practice. According to Bomb Culture, by 1963 he had ‘a hundred or so big paintings, seven novels and a number of sculptures’, all of which had been rejected by art and literary institutions.Footnote23 For Nuttall, the way forward was to bypass mainstream galleries and publishers and disseminate his own work without the refracting lens of commercialism. He would produce art free from the boundaries of conventional taste and censorship. In an extract from his previously unpublished memoir included in Better Books/Better Bookz (2019) Nuttall describes his art as:

… becoming loaded, brutalistic plaster reliefs … that attempted the vigorous crudity of iron age fertility figures, the Venus of Willendorf and the Cerne Abbas Giant … I had made a vocabulary of sexual protrusion, a quality which besides being present in the glistening, erect and intrusive penis, I found in sap-dribbling trees, in strange overnight mushroom shapes and in the nauseous profligacy of nature.Footnote24

During a delay in finding a venue for the installation Nuttall sought new ways in which the group might express their ideas and he gravitated towards the independent outlet offered by small press publishing:

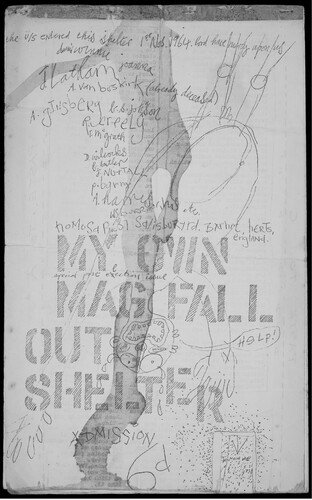

I turned out My Own Mag: a Super-Absorbant [sic] Periodical in November 1963, as an example of the sort of thing we might do. My intention was to make a paper exhibition in words, pages, spaces, holes, edges, and images which drew people in and forced a violent involvement with the unalterable facts … The magazine … used nausea and flagrant scatology as a violent means of presentation.Footnote27

On the pages of MOM, the words seem secondary to the unusual typographical settings. Text appears in forms which are very similar to those seen on the paintings Nuttall completed at this time.Footnote29 They are stain-like, paisley-shaped sexual globules; ejaculents which spread across most of the covers and many of the pages. They fit neatly alongside the provocative use of language as well as the actual stains, blots, cuts and burns which Nuttall used to give each copy its own uniqueness. Through MOM, he sought to: ‘ … make the fundamental condition of living unavoidable by nausea’.Footnote30 Nuttall wanted the reader to feel ‘dirty’, thanks to the sexualised text and drawings, as well as their organisation on the page and the very way the magazine’s paper felt to the touch.

It was intended to be a multi-sensory experience. MOM is best understood within the context of Nuttall’s multi-disciplinary approach through which he attacked the walls which separated different artforms. He was a polymath who worked simultaneously across music, performance, painting, sculpture and poetry. This is reflected in MOM, in which his experiments blur the lines between prose, verse, drawings as well as three-dimensional slashes, scorch marks and appendages ().

Sex

According to his later friend and collaborator, anarchist publisher Dr. Peter Good, Cunliffe was obsessed by sex.Footnote31 The original pornographic photographs (some with Sado-Masochist and occult themes) in Cunliffe’s archive, as well as the books in his library, about sex-magic support this assertion.Footnote32 This proclivity informs both the aesthetics and the text of the first four issues of Poetmeat, with their stark black and white covers and frank sexual language. Nuttall’s ‘aesthetics of obscenity’ were similarly central to and visible across his different artistic disciplines, even jazz (music of ‘the brothel and the speakeasy’).Footnote33 Nuttall’s use of and focus upon sex in his 1960s art speaks to the sexual repression of post-war Britain, the tension he felt within his relationships and from his concerns about the cold war. In Bomb Culture he explores the transgressive: during the late 1960s, “‘Kinky’ was a word very much in the air. Everywhere there were zippers, leathers, boots, PVC, see-through plastics, male make-up, a thousand overtones of sexual deviation, particularly sadism … ”Footnote34 Such imagery appears frequently within MOM and it is equally evident in Nuttall’s assemblages of human-like figures made from lingerie and hair (constructed from the mid-1960s) and in what became the ‘sTigma’ installation (1965).Footnote35 It was an aesthetic which Barry Miles later saw in the décor of Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s shop ‘Sex’.Footnote36

Of note within the early issues of Poetmeat is the verse of Chris Torrance whose poetry already hints at the mystical and which is at the core of his major work, The Magic Door sequence, published as a series of eight volumes, between 1973 and 2017. Likewise, the poetry of Morris connects nature with the spiritual – something which runs through all thirteen issues and much of what they called their Screeches Press output, named after Cunliffe’s first poetry pamphlet Screeches for Sounding (1962), the method by which owls fly in the darkness of night. However, within Poetmeat there is also a wider range of verse from poets as diverse in style as John Sharkey, Bill Wyatt, Penelope Shuttle and the editor of New York’s Birth Press Tuli Kupferberg. Alongside poetry Cunliffe used the magazine as a political call to arms. For example, it featured a re-print of anarchist Tony Gibson’s 1954 pamphlet ‘Youth for Freedom – Freedom for Youth’ (Issue 2, June/July 1963) along with an editorial demanding ‘Total Revolution’. There was an anti-racism edition (Issue 3, Autumn 1963) but perhaps most indicative of Cunliffe’s politics was the re-publication of Gary Snyder’s ‘Buddhist Anarchism’ in Poetmeat issue 2. Originally featured in the City Lights Journal for the Protection of All Beings issue 1 (1961), it begins, ‘Buddhism holds that the universe and all the creatures in it are intrinsically in a state of complete wisdom, love and compassion; acting in natural response and mutual interdependence’.

In the early 1960s, Morris worked with the poet and artist Adrian Henri at Manchester College of Art and volunteered in the city’s CND office at the weekends.Footnote37 By Poetmeat 4 she was announced as co-editor of Screeches Press and it is from this point that the magazine began to publish a wider range of verse alongside articles, reviews, photographs and critical essays. There is also a noticeable change in the language used in the periodical, sexual slang and references to ‘chicks’ disappear, and a more considered tone takes over.Footnote38 PM Newsletter (initially contained within Poetmeat) now included political stories and the contact addresses of left-leaning groups and they used the press to produce flyers and posters to promote their Global Tapestry animal rights group.Footnote39 Cunliffe’s poetry was often overtly political whereas the work of Morris is more subtly militant, so it is significant that Poetmeat changed at this point, from its initial Beat-influenced liberalism towards the power of collective activism. Although a search through British Poetry Magazines shows that by the early 1970s female editors were not uncommon, in 1964 Morris was just one of a handful of women publishing small press material.Footnote40

From Poetmeat issue 5 (Spring 1964) Jim Burns contributed regular small press reviews which contextualised the experimental verse of the little magazines within a much broader historical poetic perspective, and which added real value alongside the poetry to the publication. Cunliffe advertised the availability of his printer and, with Morris, published the first edition of Burns’ Move magazine and Two for Our Time, a slim pamphlet of his poetry. In turn Burns brought attention to the couple with his February 1964 Guardian article ‘The Blackburn Beats’, writing a series of small press poetry reviews for the newspaper – as Nuttall also later did.Footnote41

Cut-Ups

In early 1964 a copy of MOM 1 reached the author William S. Burroughs, then living in Tangiers, where he was working with cut-ups, a method which he had learned from the artist and writer Brion Gysin.Footnote42 At the 1962 Edinburgh Literary Festival, where he met the Scottish writer Alexander Trocchi, Burroughs explained the ‘cut-up and fold-in technique, stressing the magical powers it unleashed … and that it had once caused a plane to crash’. Barry Miles adds a further gloss, arguing that the intention behind the cut-ups was, ‘ … that of dissolving the opposites and dualities that trap humanity in time and space. He used obscenity and humour to attack control systems and saw cut-ups as a weapon to dislocate language, the main agent of power control’.Footnote43

Both Gysin and Burroughs saw beyond the artistic possibilities offered by cut-ups and believed in its occult power to reach beyond the temporal. Burroughs created many experiments using the method but found it difficult to locate a publisher able to put them out due to the technique’s unusual layout and the sheer volume of the material he produced.Footnote44 The arrival of Nuttall’s publication was therefore nicely timed. The American saw MOM as an ideal outlet due to the immediacy of the mimeograph process and Nuttall’s ability to cope with printing the extraordinary structure of his experiments.

December’s second MOM featured the first in a series of Burroughs cut-ups alongside verse by the Finnish poet and translator Anselm Hollo and more Nuttall drawings and cartoons. Although Burroughs’ work does not appear in every issue, it is at its heart; his experiments radiate outwards to encourage other contributors (including Nuttall) to engage with the process. There is something subversive and a little disturbing about what is seeping from its pages; Nuttall’s drawings and text reflect the occultism which drove Gysin and Burroughs towards the cut-up/fold-in method. By issue 4 there was a complex four column Burroughs cut-up which developed into a sub-paper entitled ‘Moving Times’. The cover has banner text which drips down onto Nuttall’s own three column cut-up experiment which, in turn, fuses a biblical sermon with a Civil Defence leaflet about surviving a nuclear strike in order to highlight the abject horror of nuclear war. The page is singed away towards the bottom as if it is a burnt offering or has perhaps been set ablaze in the cold war conflict alluded to in Nuttall’s cut-up. The second page features a disturbing short story written in a childlike Nuttall scrawl while Burroughs has a complex 32-space grid, each block containing words to be read in any direction. Soon after, Nuttall began to experiment with the cut-up idea beyond the text, mixing it with the physical ‘happenings’ (early performance art pieces) he was working on. In February 1964, he staged a party around the concept, his account of which would later appear as Mr Watkins Got Drunk and Had to be Carried Home (1968). The opportunity to use small press publishing to experiment with new techniques and to garner almost immediate feedback is key to the artistic relevance of little poetry magazines.

The MOM editor received such a large volume of work from Tangiers that Nuttall sought other outlets for its publication. The little magazine Residu edited by Daniel Richter features Burroughs cut-ups from that period. There is correspondence between Nuttall and Richter in Nuttall’s John Rylands Library archive and, although the letters are inconclusive, it is worth noting that Residu features work by Burroughs, Nuttall and Trocchi so this seems strong evidence that the Residu cut-ups also came via Nuttall.Footnote45 Letters in Nuttall’s archive also confirm that Morris and Cunliffe were offered ‘William Burroughs Time/Space experiments’ to use in Poetmeat .Footnote46 Cunliffe refused them due to a lack of space but asked for Burroughs’ address to collaborate on other projects. It seems that Cunliffe did not inform Morris about the offer, and it is probably no coincidence that this is the only letter from the Screeches editors in the archive which Morris did not co-sign ().

Conceptualism

In ‘A Poetics of Dissent: Notes on a Developing Counterculture in London in the Early Sixties’, the art historian Andrew Wilson asserts that little poetry magazines played a key role in dissolving the boundaries between art-forms, the process by which conceptualism came to the fore in the latter part of the Twentieth Century.Footnote47 As defined by the Tate gallery, conceptualism is: ‘art for which the idea (or concept) behind the work is more important than the finished art object’.Footnote48 Wilson cites as crucial to this development Trocchi’s Sigma Portfolio which he places as part of the 1960s small press revolution alongside MOM, Poetmeat, Tlaloc, Move and the little magazines of Ian Hamilton Finlay, Dom Sylvester Houédard and Cobbing. He argues that the magazines utilised avant-garde verse (particularly concrete poetry and cut-up) to collapse the walls which separated different artforms to bring about a move away from traditional praxis. The Bauhaus (1919-1933) and Black Mountain College (1933-1957) encouraged artists to think beyond their own discipline while the 1960s emergence of Fluxus reflected the desire to break the categorical chains which had prevented artists from experimenting beyond the form. Charnley highlights that Nuttall was emboldened to work across different forms of art by the tutoring he received at Bath Academy of Art, Corsham Court.Footnote49 At the prow of Nuttall’s multi-disciplinary approach was the experimentation of his poetry and, as McKenzie Wark describes in The Beach Beneath the Street (2011), Isidore Isou and the Lettrists used verse as a weapon to change culture:

Through poetry Isou pushed decomposition … the reduction of the word to the letter through a deliberate chiselling of poetry down to its bare elements. By creating a new alphabet, a new language would be possible … Isou’s mission was to gather disciples for an all-out attack on spent forms, and the creation in their place of a fresh language.Footnote50

… the cultural revolution must seize the grids of expression and the powerhouses of the mind. Intelligence must become self-conscious, release its own power [and] dare to exercise it. History will not overthrow governments; it will outflank them. The cultural revolt is the necessary underpinning, the passionate substructure of a new order of things … Footnote52

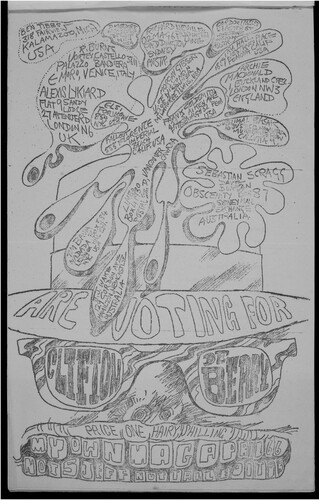

In reaction to Trocchi’s ideas the group installation became sTigma (sigma without Trocchi) and Nuttall used Better Books (where sTigma was based) and the connections that he made through MOM to develop an increasingly international network of artists to contribute to sigma. As Douglas Field has demonstrated, by mapping Nuttall’s interactions with fellow travellers from the underground scene, the poet and writer developed extensive transnational networks, which were forged through the production and dissemination of little poetry magazines.Footnote55 Cunliffe and Morris were part of this network; Cunliffe is named as a sigma participant in MOM, and he appears as a sigma member in a Nuttall letter reproduced in Better Books/Better Bookz, while correspondence from Cunliffe and Morris in the Nuttall archive shows their enthusiasm for the sigma project: ‘We’re with you all the way … ’Footnote56

According to Cunliffe a breakthrough in the development of Poetmeat came when Kupferberg sent a copy of his address book from New York, which gave access to hundreds of poets, artists and activists across the globe.Footnote57 With the help of these contacts, they began to publish experimental verse from North, South and Central America and added a sizeable readership across the Atlantic; part of the transmission of radical verse and ideas flowing in both directions between Europe and America in the early-1960s. Poetmeat now featured the work of Latin American writers Raquel Jodorowsky, Ernesto Cardenal, Octavio Paz and Gonzalo Arango alongside verse from Carol Bergé, Larry Eigner, Diane di Prima and Jack Micheline with the radicalism of the lesbian Black Panther Pat Parker, MC5 manager and White Panthers founder John Sinclair and the Black Mask anarchist Dan Georgakas. They also connected with US based artists and small press editors Margaret Randall, Mary Beach and Claude Pélieu, d a levy, Kirby Congdon and Douglas Blazek. Multiple copies of items published by Congdon, Randall and Blazek appear in the Cunliffe archive which suggests that he and Morris acted as distributor for other international small presses, further spreading verse and radical idealism from around the world.Footnote58

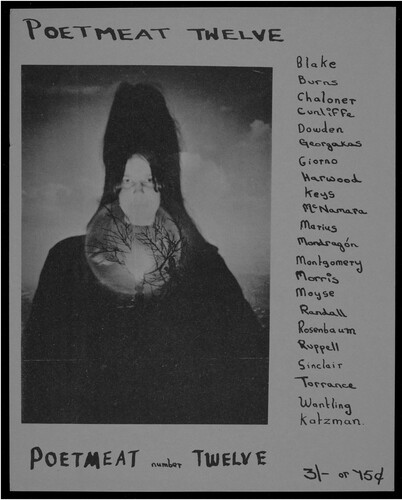

Congdon co-edited a New York Poets Poetmeat edition (issue 6, Summer 1964) which featured verse from Kupferberg, Living Theatre’s Julian Beck and East Village Other co-founder Allen Katzman. It was, however, issue 8 (April 1965) which greatly enhanced Poetmeat’s reputation within the field. The New British Poets edition was an anthology of what they considered to be the best of a new generation of writers working outside the mainstream but within a growing world of ‘underground’ publishing. In the editorial, which put the contents within the context of the wider poetry world, Cunliffe coined the now widely used term the ‘British Poetry Revival’.Footnote59 A substantial number of poets selected for this issue of Poetmeat would later appear within the Horovitz edited Children of Albion (1969), an anthology now considered the ultimate arbiter of alternative UK poetry of that era ().

Figure 4. Poetmeat Issue 12. Image courtesy The John Rylands Library and Research Institute, University of Manchester.

As Jed Birmingham points out in his analysis of the evolution of the cut-up in MOM, this technique connects Burroughs with early twentieth century Dada and the future Fluxus methods of John Cage and Jackson Mac Low.Footnote60 By issue 5 (May 1964), Nuttall had completely succumbed to the concept of the cut-up method. The cover features his drawing of Burroughs wearing a fez and clutching Nuttall’s cut-up text. Inside issue 5 Burroughs experiments with the three-column format. According to Birmingham, MOM provided a setting which shows how Burroughs’ cut-ups developed through the 1960s. The method is not static. Within Burroughs’ own practice it progresses from when he began to experiment with the idea in the late 1950s to his development of the process across the 1960s and 70s. Mimeograph publishing techniques provided a fast turnaround which fostered feedback from writers and artists. This connected Burroughs with a growing interactive international readership many of whom engaged with the process. Alongside Nuttall, cut-ups (in a variety of forms) appeared from Germany’s Carl Weissner and, from the US Blazek, Beach, levy and Pélieu.

Final editions

MOM 10 (December 1964) features ‘The 32nd Put-Down of Two Literary Gentlemen’, a comic strip collaboration between Cunliffe and Nuttall which has the kind of transgressive epithets and sexualised images which would later cause both men difficulty in the changing attitudes of the late-Twentieth Century. It is the tale of Hard-man, a violent noirish story about rent boys and rough trade:

Manchester a.m. wet, foggy, electricity failure & no neon to illuminate black kerbs broken under the day’s systematic rape. Some boy bumps into Hard-man who pulls down his jeans half-cocked and grabs hair, ass & teeth to pump unto death his leaden eruptions; sound of screams; feet running towards it.Footnote61

Through the later issues of MOM, Nuttall combined artistic reaction to Burroughs’ experiments and Trocchi’s ideas, publishing cut-ups from other writers alongside letters from artists inspired by sigma. MOM 12 (May 1965) includes images of the sTigma installation, a sigma manifesto alongside a list of participants (updated in later issues) while issue 14 (December 1965) holds a report from the initial sigma meeting. His work with the Sigma Portfolio has bled into his own little magazine and, alongside the cut-ups, provided new theoretical and practical approaches to artists working on both sides of the Atlantic. The seventeenth and final edition of MOM was published in September 1966, by which time his focus had shifted to The People Show performance art group which he developed from his early adaptation of happenings.

In 1965, Cunliffe and Morris worked with the artist and critic Arthur Moyse on Golden Convolvulus, an anthology of sex and censorship-themed verse and drawings which contained strong language alongside explicit images. When Cunliffe posted review copies, Royal Mail staff called the police who raided the house of the Screeches editors three times. Cunliffe was charged with obscenity and pleaded ‘not guilty’ which led to a trial widely covered by the media. Cunliffe received many offers of support as the litigation was considered an attack on free speech and an attempt to set a precedent away from London; George Melly and Dom Sylvester Houédard spoke on his behalf in court. In Offensive Literature (1982) John Sutherland proposes that it was an entirely political prosecution which had little to do with the contents of the pamphlet.Footnote62 He believed that it was the first of several trials during the 1960s and 70s which were an attempt by the authorities to curb encroaching liberalisation. Despite Cunliffe being cleared of obscenity (although found guilty of another, more minor charge), the legal costs almost bankrupted the couple, and the action marked the beginning of the slow decline of Poetmeat and what would be the end of Screeches Press soon after that.

Occultism

According to Barry Miles in William S Burroughs: A Life (2014), Burroughs saw his writing techniques as a way of engaging with the occult, of tapping-into new forms of creativity for use in the everyday. Although he readily published Burroughs’ experiments, and Nuttall was influenced by the outré, he did not necessarily believe that something exists beyond reality. Rather, he viewed sexual ecstasy, magic and the occult as pathways into the avant-garde which might open-up innovative methods for his verse, drawings, installations and performances. One of the strengths of Anything but Dull is Charnley’s close reading of Nuttall’s publications in which he finds a recurring phantom figure. This ‘phallic ghost’ haunts many of his texts and appears in a variety of shapes across his different art forms embodying Nuttall’s sexual hysteria.Footnote63 Nuttall, Morris and Cunliffe saw something formative within a British tradition of the pagan and the pantheist. They drew on this tradition in their own work and it similarly informed their editorial approaches to MOM and Poetmeat in both aesthetic and textual terms. Of the trio, Cunliffe was the most serious student of the esoteric and his library contained many books about Eastern religions, witchcraft and Satanism which then featured in his poetry.Footnote64 Morris divines power from the environment and nature, believing that people can commune with plants and animals, which she explores in her verse. Her best-known poem, ‘Tree’ (1978) is an early warning of the threat of global warming:

Much of the verse written by Morris contains these features, a melancholic air: ‘the vibrant jade of spring – pale to grey death’, a sadness for the destruction of nature and the environment, ‘no amount of loving can stir our weary tree to singing’, a loss of innocence and perhaps the failure of the Sixties revolution to change the world in the ways she thought possible. ‘Tree’, published later in 1978, could be read as an ode to the defeat of small-world anti-capitalism expounded by John Papworth in Resurgence, an environmentalist magazine which Morris and Cunliffe helped to set-up with publishing advice in 1966.

Counterculture

After the final issue of My Own Mag (issue 17, Sept 1966), Nuttall was commissioned by Tony Richardson at new publishing imprint Paladin to write the story of the UK underground. Notwithstanding its flaws, Bomb Culture, authored in 1967 and published the following year, remains the template for most work on the beginnings of the British counterculture. Although Morris is mentioned, very few women receive serious attention, while factual errors and misspellings abound in the first edition.Footnote66 Nuttall explicitly connects activists, artists, poets and little magazine editors as the source of the underground and he specifically names Morris, Cunliffe and Poetmeat as a key part of that movement.Footnote67 Stewart Home finds this underground spark a little earlier in 1950s London.Footnote68 He draws attention to the Bohemian scene around Victor Musgrave’s Gallery One where Musgrave lived in an open relationship with the photographer Ida Kar and held contemporary art exhibitions which included a 1957 show which featured Nuttall’s paintings.Footnote69 Kar’s archive holds images of people central to that scene which include Metzger, fellow artist John Latham and author Colin MacInnes alongside Kar’s assistant (and lover) Terry Taylor.Footnote70 In ‘A Poetics of Dissent’, Wilson emphasises as significant to the beginnings of an artistic counterculture, the 1962 Festival of the Misfits, an early London Fluxus action at Gallery One (photographs of which feature in Kar’s collection), and the later (September 1966) Destruction in Art Symposium organised by Metzger with concrete poet John Sharkey and which featured a Nuttall lecture.Footnote71

In Days in the Life, Green’s interviews outline the influence US verse had on inspiring the poets and UK little magazine editors who then sparked the early British counterculture. But Green also saw beyond the transatlantic stimulus giving credit to the impact of surrealism, Dada and Situationism on the formation of the British underground and to Nuttall’s part in passing on its flame. As he puts it, ‘A Further stimulant of the counter-culture had long played an important role in Twentieth-Century life: the European avant-garde [and] … it was appreciated by most of those, who, like Jeff Nuttall, were processed through the art schools’.Footnote72

There is scholarly disagreement about how pivotal sigma and Trocchi were to the beginnings of the British underground. The sigma concept, the initial meeting of radical artists and psychiatrists (organised by Nuttall) and the Sigma Portfolio were a nexus which connected disparate elements which later combined within the counterculture. Trocchi’s part in the June 1965 Albert Hall International Poetry Incarnation, which served to bring the underground to the attention of the mainstream for the first time, is cited as important by Green, for instance. But some commentators saw sigma as merely a cover for the fact that Trocchi’s heroin addiction made it increasingly difficult for him to produce novels. Miles dismisses sigma as a ‘magnificent junkie idea’, merely an attempt to take credit for the work of other writers.Footnote73 Although also rather contemptuous of sigma, Green did see that the ideas of Trocchi, as part of the Situationist European avant-garde, had a part in sparking the British underground, ‘Trocchi’s plans for a revolution could be said to have reached some fruition in the counter-culture over the next few years … ’Footnote74 Although nebulous, my analysis is that Trocchi’s impact on the 1960s counterculture – through his experimental novels, the sigma concept and via his force in creating new networks – is now difficult to dismiss.

Conclusion

If MOM, Poetmeat and the work of Nuttall, Cunliffe and Morris is important, why are they and their publications not more widely known? One answer might be that Nuttall and Cunliffe remain problematic figures. There is evidence that in his later role as art lecturer Nuttall transgressed normal behavioural boundaries and abused his position. According to the singer Marc Almond, who was taught performance art by Nuttall at Leeds Polytechnic in the late-1970s, Nuttall showed his penis during lectures and even urinated on a student held down by another member of staff.Footnote75 Another student of Nuttall, who attended the launch of the re-edited Bomb Culture (2018) at Hebden Bridge, claimed that: ‘he tried it on with most of his female students’ while Charnley records that Nuttall had at least two affairs with his students.Footnote76 Nuttall’s anti-feminism was later exposed through his contribution to and correspondence within Reality Studios magazine in which he compared feminism to Nazism.Footnote77 More troubling were claims in Jeff Cloves’ Nuttall obituary ‘The Case of the Histrionic Flasher’ published in Cunliffe’s later magazine Global Tapestry Journal, that Nuttall’s verse showed his ‘underage pash’ and that when Cloves and his partner visited the Nuttall family in Norwich: ‘we found Jeff’s sexual interest in his 15 year old daughter now barely disguised and very disturbing’.Footnote78

Cunliffe’s writing and behaviour in the 1970s and 1980s led to him being shunned by activist groups and Freedom newspaper. As a provocateur he attended protests wearing fancy dress and was accused of not taking political action seriously, he wrote pieces considered sexist for Peter Good’s Anarchism Lancastrium and used Global Tapestry to attack the feminist anti-pornography movement led by Andrea Dworkin. Cunliffe corresponded with the US Sexual Freedom League, letters in which he supported a convicted paedophile, and two images (clipped from magazines) of children in compromising positions were removed from his archive and destroyed on advice from the police.Footnote79

On the other hand, in the early 2000s the poetry of Morris was re-discovered and championed by Professor Robert Sheppard which encouraged her to begin writing, publishing and publicly reading verse again after a gap of many years. Her young adult fiction also gained some success, carrying subtle messages of humanity’s inherent connection with the natural world, bringing her voice to a new generation of readers who were sometimes surprised to hear about her activities in the 1960s underground.

In the final chapters of Anything but Dull Charnley discusses how what he describes as ‘political correctness’ constrained Nuttall and his art while Cunliffe used later editions of Global Tapestry to attack the same concept.Footnote80 Both Cunliffe and Nuttall felt inhibited by the liberal consensus which ironically many considered to be the result of the very counterculture of which both men had played a central part. In Hidden Culture, Forgotten History (2017), a study of Morris, Cunliffe and Jim Burns, my research highlighted the lasting impact of their poetic small press activities. My work proposed that the power of verse and the avant-garde had gone beyond literature and art to bring about the social change of the late 1960s and I contended that little magazines were the tools of this revolution: ‘This new wave of poetry broke down not only the previously rigid structures of verse, it infected the wider literary canon and then went beyond that to mutate other art forms, collapsing cultural boundaries … ’Footnote81

MOM and Poetmeat had released a dangerous and unpredictable spark over which the editors quickly realised they had absolutely no control and which returned to haunt them in later life while the warnings of ecological disaster by Morris turned out to be horribly prescient. Nuttall and Cunliffe used the space created by little poetry magazines to experiment both textually and culturally, pushing the boundaries of acceptability, refusing any notion of censorship – either governmental or from the cultural norms generated by the ideals of the wider underground movement. However, when the radical social changes occurred, in part because of the 1960s counterculture of which they played a role, they were caught unaware by the shift towards a more collaborative, lateral politics leaving both men now largely outside mainstream academic consideration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Geraldine Monk (ed.), CUSP: Recollections of Poetry in Transition (Bristol: Shearsman Books, 2012), p. 15.

2 Wolfgang Görtschacher, Little Magazine Profiles: The Little Magazines in Great Britain 1939–1993 (Salzburg: University of Salzburg, 1993), p. 123.

3 David Miller and Richard Price (eds), British Poetry Magazines 1914–2000: A History and Bibliography of ‘Little Magazines’ (London: The British Library and Oak Knoll Press, 2006), pp. 114–215.

4 The journal Total Liberty was published in Derby, UK between 1997 and 2009.

5 T. Morris (2021) interviewed by Bruce Wilkinson 5 October.

6 James Charnley, Anything but Dull: The Life & Art of Jeff Nuttall (London: Academica Press, 2022). Gillian Whiteley, ‘Sewing the Subversive Thread of Imagination’: Jeff Nuttall, Bomb Culture and the Radical Potential of Affect’, The Sixties, 4.2 (January 2012), pp. 109–33. Both quote the Yorkshire Evening Post 18 Feb 1971 in which Nuttall declares: ‘I’m an anarchist!’.

7 Jeff Nuttall, Art & the Degradation of Awareness (London: Calder, 2001), pp. 30–1. Nuttall says that his application to join the British Communist Party was rejected on the grounds of ‘being most unlikely to be sufficiently obedient’.

8 Whiteley, ‘Sewing the Subversive Thread of Imagination’, p. 111.

9 D. Cunliffe (2015) Interviewed by Bruce Wilkinson, 24 February.

10 George McKay, ‘Just a Closer Walk with Thee: New Orleans-Style Jazz and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1950s Britain’, Popular Music, 22.3 (2003), pp. 261–81. Accompanying the article are photographs which show Nuttall playing in the ‘Aldermaston Brass Band’ sourced from the family collection.

11 Nuttall, Bomb Culture, p. 191.

12 Stephen Willats, ‘Gustav Metzger’, Artforum website: Gustav Metzger – Artforum [Date accessed: 15 April 2020].

13 See Richard Taylor and Colin Pritchard, Protest Makers: British Nuclear Disarmament Movement 1958–65 (London: Pergamon Press, 1980). Samantha Jane Carroll, ‘Fill the Jails’: Identity, Structure and Method in the Committee of 100, 1960–1968 [MPhil Thesis] (University of Sussex, 2010). Neither mention a C100 ‘Happening Group’. John Rylands Library & Research Institute University of Manchester. Dave Cunliffe Collection. Box C5. Letter from Cunliffe to unnamed recipient dated 16 October 1977 discusses his ‘Exorcism of War Demons’ with Nuttall.

14 R. Wilcocks (2021) Email to the author from Richard Wilcocks 20th April.

15 Dave Cunliffe Collection. Flyer from ‘The Happenings Group Committee of 100’ for Alconbury protest 3rd July 1966 which includes poems by both Cunliffe and Wilcocks. File BBB6 Box C18.

16 Jonathon Green, Days in the Life: Voices from the English Underground 1961–1971 (London: Pimlico, 1998), p. 24. Nuttall recalls his arrest at a C100 demonstration. A letter to the author from Dave Cunliffe 28 May 2014, confirms he was arrested and bound over at C100 actions and risked a lengthy prison sentence after arrest at a Trafalgar Square protest. Cunliffe claimed that at earlier arrests he gave a false name and address which weren’t checked but which were after the Trafalgar Square protest.

17 Bruce Wilkinson, Hidden Culture, Forgotten History: A Northern Poetic Underground and its Countercultural Impact (Warrington: Penniless Press, 2017), p. 197.

18 Poetmeat issue 1 publication date: April/May 1963 – unpaginated.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 See Dave Cunliffe article about their Global Tapestry group in Peace News 3rd October 1969.

22 T. Morris (2021) interviewed by Bruce Wilkinson 5 October.

23 Jeff Nuttall, Bomb Culture (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1968), p. 149.

24 Rozemin Keshvani, Axel Heil and Peter Weibel (eds), Better Books/Better Bookz: Art, Anarchy, Apostasy, Counter-Culture & the New Avant-Garde (London: Koenig Books, 2019), p. 311.

25 Peace News, July 13, 1962. A letter from Peter Currell Brown sought artists ‘to work together to form an explosive power for peace, love and individualism’.

26 Peter Mayer (ed.), Bob Cobbing & Writers Forum (London: Writers Forum, 2010), p. 63. See ‘Checklist of Writers Forum Publications’. Wolfgang Görtschacher, Contemporary Views on the Little Magazine Scene (Salzburg: Poetry Salzburg, 2000), p. 302. Interview with Bob Cobbing.

27 Nuttall, Bomb Culture, p. 151.

28 Ibid., p. 152.

29 See image of his ‘globular’ artwork in a photograph of a Group H exhibition in Birmingham dated ‘early 1960s’: Images (webarchive.org.uk) [Date accessed: March 2018].

30 Nuttall, Bomb Culture, p. 150.

31 Good, P. (2021) Email to the author from Dr Peter Good 2 March.

32 Dave Cunliffe Collection. File marked ‘Porn’, Box 101. Sets of uncatalogued pornographic photographs taken by ‘Jim Lehman’. Author spreadsheet listing Dave Cunliffe’s book collection.

33 Nuttall, Bomb Culture, p. 13.

34 Ibid., p. 37.

35 G. Whiteley (2021) Email to the author dating Nuttall assemblages from Dr Gillian Whiteley 8 October.

36 Barry Miles, London Calling: A Counterculture History of London Since 1945 (London: Atlantic, 2010), p. 333.

37 Correspondence with Tina Morris 7 October 2015.

38 For instance, Poetmeat 1 contains a Cunliffe attack upon Conservative Home Secretary Henry Brooke in which the terms ‘cunthood’, ‘chicks’ and ‘dry withered cock’ feature. Brooke was accused of racism in his unwillingness to prevent the 1962 deportation of Jamaican Carmen Jones, convicted of shoplifting goods valued at just £2.

39 Dave Cunliffe Collection. Folder BBB1, Box C17. Flyers: ‘Happy Birthday Jesus: Happy Deathday Turkey’ and ‘Would Christ Have Wrung the Neck of a Turkey?’.

40 Miller and Price (eds), British Poetry Magazines, pp. 125–215. Using the listings within Section D: 1960–1975, the only other identifiable UK female editors in the early 1960s were Diane Troy (Carcanet), Vera Rich (Manifold), Maureen Duffy (The Sixties), Lynn Carlton (Viewpoints) and Angela Carter (Vision).

41 In 1963–64 Jim burns contributed 11 small press poetry focused articles to the Guardian and then wrote about verse for a variety of other publications. From July 1979 to July 1981 Nuttall’s ‘Poetry in Print’ column featured in 20 issues of the Guardian. Nuttall later wrote for the Independent newspaper along similar lines.

42 Barry Miles, William S Burroughs: A Life (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2014), pp. 362–3. According to Miles Gysin began experimenting with cut-ups in 1959 when resident at the ‘Beat Hotel’ in Paris where he passed-on the idea to Burroughs.

43 Ibid., pp. 424–5.

44 Ibid., p. 426.

45 Jeff Nuttall Papers John Rylands Library and Research Institute. JNP/2/43. Letters from Dan and Jill Richter.

46 Jeff Nuttall Papers. JNP/2/11. Correspondence with Dave Cunliffe and Tina Morris.

47 Andrew Wilson, ‘A Poetics of Dissent: Notes on a Developing Counterculture in London in the early Sixties’, in Chris Stephens and Katherine Stout (eds), Art & The 60s: This Was Tomorrow (London: Tate, 2004), pp. 93–111.

48 Tate website: Conceptual art | Tate [Date accessed: 09 March 2024].

49 Charnley, Anything but Dull, pp. 54–7.

50 McKenzie Wark, The Beach Beneath the Street (London: Verso, 2011), p. 13.

51 Nuttall, Bomb Culture, p. 166.

52 Ibid., p. 167.

53 Sigma Portfolio issue 16. I first found this reference via James Riley’s Trocchi blog: residual-noise.blogspot.com [Date accessed: 29 Jan 2019].

54 Miles, London Calling, p. 139. Jonathon Green, All Dressed Up: The Sixties and the Counterculture (London: Pimlico, 1998), p. 135. Wark, The Beach Beneath the Street, p. 183.

55 Douglas Field, ‘Mapping the International Underground: Jeff Nuttall and the Global Counterculture’, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, 93.1 (2017), pp. 1–21.

56 My Own Mag issue 12 (May 1965). Photographs of the sTigma installation, a sigma manifesto and a list of sigma participants which includes Poetmeat/Dave Cunliffe p.9. Letter to sigma participants from Nuttall dated 5 November 1965. Keshvani et al. (eds), Better Books/Better Bookz, p. 154. Jeff Nuttall Papers. JNP/2/11. Correspondence with Cunliffe and Morris.

57 D. Cunliffe (2015) Interviewed by Bruce Wilkinson, 24 February.

58 Dave Cunliffe Collection. Multiple copies of El Corno Emplumado (Boxes 34–36); Congdon and Crank Press/Interim Books (Box 28); Blazek and Open Skull Press (Box 29).

59 Until the publication of Robert Sheppard’s The Poetry of Saying (Liverpool University, 2005) most believed that Eric Mottram had coined the term British Poetry Revival in a 1974 conference paper. Sheppard was the first to point out that the phrase was used in the editorial of Poetmeat 8 which he credited to both Morris and Cunliffe. However, Morris confirmed to the author that it was Cunliffe who wrote the editorial of that issue.

60 Reality Studio Website, Jed Birmingham article: https://realitystudio.org/bibliographic-bunker/my-own-mag/the-evolution-of-the-cut-up-technique-in-my-own-mag/ [Date accessed: 24 March 2019].

61 My Own Mag Issue 10 December 1964 unpaginated.

62 John Sutherland, Offensive Literature: Decensorship in Britain 1960–1982 (London: Junction Books, 1982), pp. 61–4.

63 Charnley, Anything but Dull, p. 168.

64 The author has an Excel spreadsheet which contains a list of books in Cunliffe’s library.

65 Tina Morris, Mirrors and Moonshine (Preston: Freebird, 2016). The poem originally featured in Tree (London: Court Poetry Press, 1978). Permission to reproduce here kindly granted by Tina Morris.

66 Nuttall, Bomb Culture, p. 187.

67 Ibid., p. 187.

68 Terry Taylor, Baron’s Court, All Change (London: Cripplegate, 2021). Stewart Home Introduction.

69 Research by Gillian Whiteley on the website lists Nuttall’s art exhibitions: https://bricolagekitchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Text-by-Gillian-Whiteley-for-Jeff-Nuttall-exhibition-Burnley-2005.pdf [Date accessed: 23 November 2022].

70 Ida Kar Archive at the National Portrait Gallery. Digitised at: https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp07861/ida-kar?role=art [Date accessed: 28 October 2021].

71 Keshvani et al. (eds), Better Books/Better Bookz, pp. 216–22.

72 Green, All Dressed Up, p. 122.

73 Miles, London Calling, p. 136.

74 Green, All Dressed Up, p. 135.

75 Marc Almond, Tainted Life: The Autobiography (London: Pan, 2000), p. 61.

76 Charnley, Anything but Dull, pp. 345–6. Liverpool Polytechnic alumni Bob Scriven and David Clapham accuse Nuttall of having affairs with students while a lecturer there.

77 Reality Studios Vol 3 (1981) and Vol 4 (1982).

78 Jeff Cloves, ‘The Case of the Histrionic Flasher’, Global Tapestry Journal, 29 (undated), pp. 2–13.

79 Dave Cunliffe Collection. Sexual Freedom League correspondence (Box C35).

80 For example, see Cunliffe’s Arthur Moyse obituary: Global Tapestry Journal, 26 (undated), p. 25.

81 Wilkinson, Hidden Culture, Forgotten History, pp. 91–2.