Abstract

A multi-layered artistic scene of site-specific urban interventions crosses the border cities of Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario. Consumption-oriented approaches to scenes as clusters of urban amenities would disqualify these cities as loci of scenes: Detroit's scattered hip enclaves have had little influence upon neighbouring acres of abandoned buildings and vacant lots, whereas Windsor has promoted a new downtown cultural district and university campus but remains dotted with empty storefronts and boarded-up structures. Yet, scenes are deeply engrained in their imaginaries – famously in Detroit's many musical scenes, but also historically in cross-border mobilities of peoples and goods. Simultaneously integrated and divided, Detroit/Windsor is riddled with tensions between cross-border circulation and the border's increasing impermeability, and between images of stasis and transformation. An experimental scene of creative collectives and site-specific projects has responded to these tensions, disordering the material character of urban spaces and the built environment, the people, things, and media that pass through them, and their legal and institutional frameworks. Empty spaces, low rents, the circulation of discarded objects, the shifting economic conditions of skilled labour and ‘making’ cultures, and the availability of academic institutions have all contributed to these creative initiatives. Projects to stabilize neighbourhoods within Detroit are complemented by projects in Windsor that address forms of urban crisis deeply linked to Detroit's future. Windsor art collectives enter into an asymmetrical dialogue with site-specific projects in Detroit as both insiders and onlookers, not in the sense of idle urban spectators but as an audience expressing its intimate knowledge of Detroit's history and current conditions. In opposition to each city's hurry to demarcate cultural districts and creative economies, the projects I describe are oriented to cautious and considered transformation grounded in dialogue, workshops, research and planning.

Detroit is attracting artists in numbers large enough to earn it a designation as another Berlin: a city with a struggling economy where creative types can live and work cheaply – and where, like [Matthew] Barney, they can realize projects that would be impossible most anywhere else. In Berlin, though, artists pursue international careers; in Detroit, they speak only to Detroit – because, they say, anywhere else they would just be making art. In Detroit, they can make a difference. (Linda Yablonsky, ‘Art Motors On’, W Magazine, November Citation2011)

This pervasive emphasis on Detroit's internal dynamics, however, also serves to overshadow its location directly on the Canadian international border and North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) trade corridor. Few cultural commentators are curious about this geography, past or present. A generation of auto industry decline in Detroit seems to have eradicated any historical sense of the origins of the city as le détroit, the narrows of the Detroit River. Across the Canada–US border, Windsor, Ontario, a city of some 200,000 residents, and its neighbouring suburbs, have developed and declined alongside Detroit's colonial and industrial history. In many ways, Detroit–Windsor is a simultaneously integrated and divided urban environment in which patterns of cross-border circulation and impermeability are integral to each city's character – conditions neglected or merely footnoted especially in the many histories of Detroit's racial, economic and infrastructural struggles. Cross-border connections mark these cities in ways that distinguish them from the globalized flows of people, materials and information that regularly pass through them. While artists have long drawn upon cross-border affinities, a multi-layered Detroit–Windsor creative scene has become evident in an array of creators and collectives that all strive to counter the cheap aestheticization of empty industrial spaces and structures through site-specific initiatives, incremental urban transformation and neighbourhood stabilization.

Prior to 9/11, the international border between Canada and the USA was relatively open; today, it appears to be ever thickening for people, even as cross-border trade is ever more urgently promoted. While Detroit has witnessed revitalization and gentrification in parts of its centre, few benefits have trickled down from these hip urban enclaves to neighbouring acres of abandoned factories, buildings and storefronts, rundown residences, and vacant lots (Sugrue Citation2005, p. xxv). Windsor, long classified as Canada's Detroit (albeit less dramatically ‘ruined’), also began promoting a new downtown Cultural District and university arts campus in 2011. It too is nonetheless dotted with empty storefronts and boarded up structures. Images of dense urban sociability are reduced in Detroit to a few blocks of tourist destinations in Corktown, Greektown, Midtown and the Sugar Hill Historic District, or the Saturday morning Eastern Market (Herron Citation1993, p. 18), and in Windsor to a number of downtown streets that for decades have been oriented to hospitality industries – bars and clubs – as a draw for young Americans. If urban scenic life only takes shape as part of the trend towards ‘creative cities’, alongside urban density and the availability of amenities (see Silver et al. Citation2010, Citation2011), then Detroit and Windsor would be largely devoid of cultural scenes. Yet scenes are deeply engrained in their imaginaries – certainly in Detroit with musical scenes including Motown, metal, techno and hip-hop, but also historically in cross-border patterns of mobility of people, labour and goods [consider, e.g. the cases of the Underground Railroad, prohibition smuggling, or early twentieth-century cross-border labour movements (see Klug Citation1998)].

The narrative of Detroit as a city of ruins provides a peculiar backdrop to creative initiatives: ruined Detroit produces an aura of stasis through which the city is characterized either as ‘dramatic’ or ‘an open canvas’. This stage-like atmosphere is often interpreted as a space for nostalgia, recalling and replaying Detroit's ‘golden era of Fordist prosperity’ (Steinmetz Citation2008, p. 211), but it also generates discussion about cultural initiatives that place Detroit on the path to urban renewal and sustainability. Site-specific urban experiments in Detroit have taken shape within this distinct ruined landscape of the city. These projects are scenic when they collectively circulate understandings of Detroit's conditions and broadcast an expanding narrative of Detroit as a model city in which creative endeavours prefigure ambitious forms of urban transformation.

For Windsorites, Detroit forever looms. The panorama of the Detroit skyline beckons to Windsor, and in turn, Windsor bears witness to Detroit from the position of an observation post, a lookout connected to yet separated from the economic forces and racial tensions that engulf its larger neighbour; an observation post closely linked to the vast Detroit ‘canvas’. Through the integration of Detroit's imaginary into Windsor's sense of self, the border operates less as boundary and more as an interval of resonance, in McLuhan's sense of borderline (McLuhan Citation1977, p. 226). When it comes to Detroit, Windsorites are a particular brand of urban spectator. They are not idle, but rather intimate onlookers. The border's many spaces and forms of circulation yield creative energies that work against the overwhelming sense of stasis associated with abandoned landscapes and ruins. Within Windsor, I argue, a creative community strives to work as intermediary between Windsor and Detroit. Numerous Windsor-based artists embraced Detroit's famed Cass Corridor scene of the 1960s and 1970s, a period of artistic fomentation that took place in the district south of Wayne State University. Windsor's ArtCite, one of Canada's first artist-run collectives and an early Windsor–Detroit institution to pay an artist fee, has often reflected the depth of involvement of Windsor's creative community's within Detroit, represented, for example, in its 1986 retrospective Borderlands: Art from the Edge. Artists such as Susan Gold and Chris McNamara have long studied, practiced and taught in both cities. Acutely aware of the constant cultural trajectories of movement across the border, this community negotiates the ambiguity of the border as both porous and impermeable. In this sense, a smaller Windsor scene of site-specific projects and collectives has taken root, adapting the specificity of Detroit's internal creative scene by commenting on Windsor's asymmetrical relationship to Detroit and the international border. In Detroit, projects such as the well-established Heidelberg Project and more recently Power House Projections, the Unreal Estate Agency, ArtsCorps Detroit, among others, all work through incremental, contemplative urban interventions to counter states of dereliction and to urge neighbourhood stabilization (Rodney Citation2014, pp. 261–262). And in Windsor the Green Corridor Project, the Broken City Lab (BCL) and the Border Bookmobile have reacted to Detroit's experimental cultural activity by reconceptualizing various border spaces as places equally open to transformation. These projects underscore specificities of Detroit–Windsor that resist simple identification with other experimental urban arts scenes, perhaps most prominently because they also resist a bohemian attitude about ‘artists’ exemption from social responsibility’ (Deutsche and Ryan Citation1984, p. 105). Attentive to the minutiae of everyday life in one or both cities, this cross-border scene does not operate as a coordinated network of creators, but collectively works to circulate ideas for intervening in the underlying social, economic and political processes engulfing the region.

Will Straw has noted how the term ‘cultural scenes’ is frequently used either ‘to circumscribe highly local clusters of activity’ or ‘to give unity to practices dispersed throughout the world’ (Citation2001, p. 248). If a Detroit scene appears distinctly local, circumscribed by the city's specific political and economic conditions, the asymmetrical relationship between Detroit's scene of site-specific experimentation and a Windsor scene rooted in the cities’ border culture affords us a unique opportunity to observe the elastic, yet overlapping, boundaries of such highly localized scenic activities and energies. Detroit–Windsor provides a case study for interrogating the ways in which asymmetrical relationships between border cities, within the context of global cultural flows, are also distinctly manifested in local forms of cultural expression.

Creativity for or against the city

Fuelled by artisanal coffee, grassroots ethics, and a whole lot of elbow grease, Detroit's Arts and Crafts scene is revving up again. (Alexandra Redgrave, En Route magazine, 2013)

As with many cities, Detroit and Windsor have listened intently to the discussion in urban scholarship and popular news media about the virtues of investing in creative industries and fostering a creative class (i.e. Florida Citation2002, Citation2005). This is the image portrayed by the author of the En Route article, who describes her emotional response to walking through Detroit's Russell Industrial Centre, a post-industrial hub of artisanal and creative activity:

Walking around the cavernous space, aptly described by one artist as ‘a whole neighbourhood in a building’, gives me the sense that the RIC stands in for Detroit itself: a work-in-progress propelled by elbow grease and creative clout. (Redgrave Citation2013, p. 48)

Like larger Canadian cities such as Toronto and Montréal, Windsor has turned to cultural planning as a means to urban revitalization, adopting its Municipal Cultural Master Plan in 2010 and promoting a Cultural District through a series of development projects announced in 2011: a new Aquatics Centre; collaborations between the Art Gallery of Windsor and a new City Museum; and redevelopment of the Windsor/Detroit Tunnel Plaza. The University of Windsor has invested in this process with plans to open a downtown campus in 2016 by relocating its creative arts programming to the original Windsor Armouries and former Greyhound bus terminal. These investments acknowledge the presence of culturally expressive energies and are driven by the notion that related creative economies could be mobilized politically towards the resuscitation of struggling small-city downtowns. At the same time, both the creative city model and attendant definitions of creative labour present a selective and limited definition of what constitutes a cultural scene.

The grammar of scenes: theatricality, seeing, project

From 2001 to 2006, I participated in a study of the culture of four cities (Montréal, Toronto, Dublin and Berlin) that sought to develop comparative frameworks for examining the specificity of urban cultures. How do cities retain their distinctiveness in an age of global and transnational cultural flows? One area of cross-disciplinary interest that emerged from this Culture of Cities Project was the notion of the ‘urban cultural scene’, one of the foci among the contributions to this special issue of Cultural Studies. At the time the project's director, Alan Blum, suggested that ‘scenes’ are:

recurrences envisioned as master categories that organize the very description of the city – the gay scene, the music scene, the drug scene, the art scene, the tango scene, the rave scene. Here, it sounds as if scenes, like commodities, circulate in ways that might bring them to some cities rather than others or to all cities in varying degrees. (Citation2003, p. 166)

if the scene points to a recurring feature of all cities, or of any city worth its name (imagine a city that could not claim any scenes), then this universal function is distributed differently. Scene resonates with some concerted activity, an activity to a degree specialized, at least differentiated, but not necessarily covert. (Citation2003, pp. 166–167)

scenes may be distinguished according to their location … the genre of cultural production which gives them coherence (a musical style, for example, as in references to the electroclash scene) or the loosely defined social activity around which they take shape (as with urban outdoor chess-playing scenes). Scene invites us to map the territory of the city in new ways while, at the same time, designating certain kinds of activity whose relationship to territory is not easily asserted. (Citation2004, p. 412)

in the struggle to do seeing and to being seen – to be seen seeing, and so, to be absorbed in the action rather than an idle onlooker – [which] marks its subject as exhibitionistic rather than voyeuristic, that is, as one who is actively seen seeing and so, as engaged by the reciprocity of seeing as an act of mutual recognition. (Blum Citation2003, p. 172)

A scene, as it gathers strength, makes those who are idle and detached, appear out of place. This reminds us that a scene is always a project, and as such, makes the encounter with place a test for all those who fall under its spell. (Blum Citation2003, p. 188)

Detroit ruinscapes

The vast population decline in [Detroit] has created a scene that looks as if it has never left the year 1968, kept in an eternal freeze frame, while nature grows over it. (Mitch Cope Citation2004, p. 11)

What could potentially be a community of individuals working collaboratively to give a city a voice and restore its vitality, is overrun by a network of isolated, narcissistic individuals shouting, ‘Look at me! Look at this dangerous place I visited! Make me your hero!’ (Citation2007)

As Lee Rodney (whose Border Bookmobile project I discuss below) writes, ‘ruin porn simultaneously offends and appeals as we see something of ourselves in the theatricalized, extreme scenarios pictured in the glossy, large format photographs’ (Citation2014, p. 263). But an alternative sense of the city's creative scene is emerging against the backdrop provided by such theatricalized accounts of Detroit as a scene of ruins. In contrast to the image of Detroit as a stagnant stage for ‘ruin exploration’, urban interventions by artists with both local and international roots – some supported, others contested by local communities – attempt to engage with the city as a site of change, where empty spaces are characterized by constant movement: the circulation of waste and abandoned artefacts, and the gradual transformation of the built environment's material character, either by the process of decay or by intervention. By highlighting the transformational character of ruins (Edensor Citation2005) and inviting spectators to be visible as engaged participants, these projects dislocate the commonplace narrative of Detroit's cultural implosion, shifting our attention to the ways in which we might re-construct disconnected stories and individual lived experiences whose traces are discernible only in fragments.

Scenes of Detroit

The rumors are true: Detroit's contemporary art scene thrives. (Colin Darke Citation2011)

My love for Detroit began with the hearty souls who occupy the city because they are reminiscent of the rural farming families among whom I spent my childhood. Their inventiveness, individualism, persistence, and ability to deal with enormous daily frustrations are a constant wonderment. The ‘frontier’ mentality that dominates large areas of Detroit is illustrative of great opportunity. It is also a mentality that is less concerned with race than with individual fortitude. There are a host of creative urban experiments taking place throughout the city that illustrate this individualism. These include large-scale urban farming enterprises, guerrilla gardening, ad hoc public transportation systems, green building experiments, ‘found object’ constructions, food cooperatives, co-housing enclaves, and vigorous art and music installations and performances. The city is ripe with opportunities for cultural experimentation – with or without the approbation of government. (Vogel Citation2005, p. 19)

peeling back of Detroit's scarred past to reveal its bucolic but tragic destiny is an exercise inspired not from mainstream academia but from a subversive counter-tendency involving artists, artist collectives, curators, cross-disciplinary researchers, writers, film directors, and disillusioned professionals all hot-wired together into an expansive global network. (Lang Citation2005, p. 11)

The heterogeneity of these creative urban experiments is itself one of the central characteristics of such a scene. Their proponents may have little contact with one another, but they share a commitment to Detroit as a place for experimentation.

Herscher's Unreal Estate Guide itself started as a project, the Unreal Estate Agency: an ‘open-access platform for research on urban crisis, using Detroit as a focal point’ (Citation2012, p. 2). Launched in 2008 as a collaboration between Herscher, fellow University of Michigan architectural scholar Mireille Roddier, Dutch curator Femke Lutgerink, as well as Christian Ernsten and Joost Janmaat of the Amsterdam-based collective Partizan Publik, the Agency's founding principle was to regard ‘Detroit as a site where new ways of imagining, inhabiting and constructing the contemporary city are being invented, tested and advanced’ (p. 2). Working with Power House Projections founders Gina Reichert and Mitch Cope (discussed below), the Agency hosted a residency for the Dutch artists. As Lee Rodney reports, the collaboration at first:

proved an awkward clash of worlds and ideals. […] Many of the visiting artists expressed their discomfort and ambivalence about responding aesthetically to Detroit as outsiders. However, in spite of the uneasy situation they produced a makeshift outdoor chandelier that ran from electrical wires of a vacant lot without street lights. (Citation2009, p. 11)

Detroit's primary site-specific venture that seeks vitality in ruins is the Heidelberg Project, initiated by artist Tyree Guyton in 1986. Over nearly three decades, Guyton has adapted and appropriated abandoned properties along a block of Heidelberg Street in his childhood neighbourhood on Detroit's Eastside. Heidelberg is a curious amalgam of artefacts both made and found that Guyton has assembled out of the detritus that circulates through the neighbourhood. Houses, cars, trees and streetscapes are decorated with coloured polka dots. By imposing patterns of regularity to the display of decaying stuffed animals, rotary telephones, shoes, vacuum cleaners, tires and other objects of everyday urban life, Guyton's project is a ‘defamiliarization of what was conventionally perceived to be mere garbage’ (Herscher Citation2012, p. 286). The Heidelberg Project has appropriated both objects and adjacent properties, opening a debate with the city about its status as art or a form of squatting. Partly in response to community anger over the project's transformation of the site, the City of Detroit has twice endeavoured to demolish the project in 1991 and 1999. In 2013 and 2014, a number of the project's main houses burned down in apparent acts of arson – but if the Heidelberg Project is representative of Detroit's site-specific cultural scene, we glimpse the scene's capacities not only to reflect upon its own mortality but also to extend itself into the narrative of the city as a whole. As an article in the Detroit Free Press declared ‘the art, like Detroit, will survive’ (Stryker Citation2013).

Heidelberg's focus on neighbourhood stabilization is often compared with Power House Projections, a collective on the edge of the city of Hamtramck (a stand-alone municipality within Detroit) that has also won international acclaim. Initiated by artists Gina Reichert and Mitch Cope, who together had previously established the collective Design 99, the project is centred on the renovation of one particular property, the Power House, but has expanded to a number of neighbouring houses and spaces. Hamtramck, a more densely populated, diverse (including a substantial Bangladeshi population), and comparatively more affluent district than Heidelberg's Eastside, has nonetheless experienced its share of abandonment, criminality and vandalism. Cope, an artist by training, and Reichert, an architect and designer, bought the Power House – ‘a former foreclosed drug house’ for $1,900 in 2008, and soon purchased adjacent lots valued even less (Power House ProductionsCitation2013). Renovated with solar and wind power, the Power House represents a self-sustainable urban enclave, aiming to power adjacent properties, as well as a process of neighbourhood empowerment through participatory action. While Cope and Reichert do not hail from this area, unlike Guyton who grew up on Heidelberg Street, they nonetheless envisage the project as equally invested in the neighbourhood. As the Power House has transformed into Power House Productions, an artist-run, neighbourhood-based non-profit organization funded through grants from local and national foundations, nearby houses have been purchased and transformed into, or proposed as, such concepts as the Sound House, the Skate House, the Play House, the Squash House, the Jar House Office & Guest Home, and the Ride-It Sculpture Park, a skate park where you ride the art. All these ‘concepts’ aim to increase neighbourhood participation through meeting and performance spaces for community members and youth. In each of these instantiations of the project, slow and considered architectural processes, focused on sustainable activity and resourced through local and found materials, are themselves primary performative acts (Herscher Citation2012, p. 246). The Power House unfolds as living architecture, in which contemplative process resists and counters the demand for efficiency and haste in a housing market that so badly failed at the height of the 2008 financial crisis.

If the Heidelberg Project and Power House Productions each instantiate a project (in the theory of scenes) of living and surviving in Detroit, they diverge from another initiative that received widespread media attention: the Ice House, a proposal to encase an abandoned Detroit house in ice. Undertaken in 2010 as a commentary on the housing crisis, the Ice House appeared to some to be another venture by artists who appear in Detroit ready to take advantage of the ‘open canvas’. Instead, the project recalled rather than criticized the aestheticizing tendencies of ‘ruin porn’, which, as John P. Leary has lamented, ‘dramatizes spaces but never seeks out the people that inhabit and transform them’ (Citation2011). As one Detroiter remarks in Mark Binellli's book, Detroit City is the Place to Be:

People don't understand how offensive ‘urban exploration’ is to us. Just the arrogance of it. What do you think would happen if four black kids went into one of those buildings? They'd be arrested. White kids? All right, go home son. Freezing houses. Detroit isn't some kind of abstract art project. It's real for people. These are real memories. Every one of these houses has a story (Binelli Citation2012, p. 285)

Close ties between creative initiatives and cultural institutions in art education and exhibition are also a notable feature of the experimental art scene of Detroit. According to Straw, ‘scenes take shape, much of the time, on the edges of cultural institutions which can only partially absorb and channel the clusters of expressive energy which form within urban life’ (Citation2004, p. 416). All of the artists discussed either studied at local art colleges or are affiliated as instructors and curators with local institutions. Guyton studied at the private College for Creative Studies, one of the central incubators for design culture in Detroit's manufacturing history. Reichert and Cope each undertook art degrees at Detroit's Cranbrook Academy of Art, through which Cope participated in the Detroit-leg of the international Shrinking Cities Project that investigated conditions of population decline and restructuring facing urban regions in Berlin, Detroit and other cities. Reichert has taught university and college students at local universities, and Cope also served as one of the first curators at the up-and-coming Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, located in a former auto dealership, which is now emerging as a hub of creative experimentation in urban settings. Marion Jackson, former Chair of Art and Art History at Wayne State University, served on the Board of the Heidelberg Project for 12 years and is one of the key organizers of Arts Corps Detroit, a Wayne State-affiliated ‘service-learning’ course and art project that has partnered with local community groups, including Heidelberg. Working with neighbourhood groups, Arts Corps’ ‘LOTS of Art!’ project invites Wayne State affiliates to repurpose selected underutilized parcels of land as interactive, community art spaces. Closely affiliated with local institutions, Heidelberg and Power House offer their own youth internships and training programmes, and thus serve as hubs for the dissemination of creative energies outward from the internal dynamics of their neighbourhood projects.

If these dispersed site-specific creative initiatives give shape to a Detroit experimental art scene, it is nonetheless a scene that contemplates the particularities of Detroit without overtly extending itself to other cities. Detroit's scene appears unusual and unique, as with Detroit itself, paralleled only by select shrinking cities such as Berlin in the 1990s with their own specific economic and political histories (Forkert Citation2013). Nevertheless, a related experimental scene has emerged in Windsor through its bordering relationship with Detroit (as both local suburb and transnational neighbour), a scene that invites us to consider Windsor as a site of both spectating and participating. The asymmetrical relationship between Detroit and Windsor is mirrored in the flow of cultural energies between their scenes as spaces of integrated cross-border cultural activity, and simultaneously throws into relief the constant transnational movement of capital, goods and people that characterizes the border culture of the greater Detroit metropolitan area.

Onlooking Detroit: cross-border circulation

The border with Detroit yields a magnetism that is central to Windsor's imaginary. My first impression of Windsor was of a thin strip of land opposite an entrancing skyline, a city built as a lookout. Travelling at dusk from the train station along Riverside Drive, I realized that I had never fully grasped the proximity of Windsor to Detroit. Only in subsequent visits did I begin to take in how Windsor was organized, stretching away from the river along numerous arteries oriented to industrial infrastructure. Detroit's skyline is embedded in Windsor's visual identity (a student once commented that Windsor ‘owns’ the Detroit skyline). Similarly, tour guide images of Detroit frequently portray the city from the vantage point of Windsor, as if Detroit's best view is from outside the city (Rodney Citation2014, p. 268). When Detroit Emergency Financial Manager Kevin Orr held a press conference regarding the city's filing for bankruptcy (19 July 2013), he stood in front of an image entitled ‘Reinventing Detroit’ depicting a view of the Detroit skyline taken from Windsor.

Faced with Detroit's epic history, and witnessing parallel economic and infrastructural downturns, Windsor is in many ways its little cousin. At other times, Windsor operates as an additional suburb of Detroit alongside established suburban centres such as Grosse Pointe and Royal Oak. Yet as a city on the other side of the border, Windsor retains an individuality that also sets it apart from the greater Detroit area. While Windsor's population has declined by 2.6 percent since the economic downturn of 2008, Detroit City has lost some 20 percent of its population since 2000. In real numbers, Windsor's last census population count of 210,891 (in 2011) is not wildly smaller than Detroit City's last count of 684,799 (in 2012; City of Detroit, Office of the Emergency Manager Citation2013, p. 1), acknowledging of course that the ethnic composition of these cities remains very different. However, these numbers do not capture the population of the greater metropolitan area surrounding both cities: including Detroit's many suburbs, the population of greater Detroit–Windsor is close to 6 million. To consider this greater urban region requires attending to cross-border patterns of circulation and impermeability that are constitutive of the simultaneously integrated and divided environment of the Detroit–Windsor borderlands.

Cross-border mobilities – of populations and media forms, of invasive species and industrial materials – have long underscored the ambiguity of this border as a physical boundary, its status as both a permeable waterway and a political obstacle. This point was driven home by international media attention in 2013 on a three-story pile of petroleum coke, covering one city block, that built up unannounced on underused railway spurs on the Detroit side of the river, reviving fears of environmental cross-border contamination and galvanizing local community groups on each side to coordinate resistance efforts (Austen Citation2013). Standing opposite the greened landscape of Windsor's Odette Sculpture Park, the petcoke piles brought into relief marked distinctions between values associated with urban space: while Windsor's parkland is built on former industrial sites, similar spaces in Detroit to be zoned for industrial use merely hundreds of metres away.

Cross-border trade and traffic has of course always been integral to the borderland economies, regardless of the US Department of Homeland Security's attempts to redefine North American border control and security. When Ford established assembly plants in Windsor, he quickly had access to the tariff-free zones of the British Commonwealth and thereby established one of the earliest international trade corridors. Thomas Klug has documented the complexity of the Detroit Labour Movement throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, where daily commuters and strikebreakers from Canada were perceived as a threat to Detroit labour-market security (Klug Citation1998, Citation2008). Prohibition era and post-war economies deriving from illicit industries flourished through cross-border relationships and shifting discrepancies between USA and Canadian currencies, while fomenting moralistic debates about legal and illegal forms of vice. In both cities, these debates extended into the late twentieth century with regard to the legalization of gambling (see Karibo Citation2012).

Just as thousands of Windorites today cross the border daily to work in manufacturing, health and other NAFTA-regulated industries, agricultural goods and industrial materials – especially within the automotive sector – circulate regularly across the border. Bill Anderson describes a ‘distinctive pattern of US–Canada automotive trade whereby Canada exports a larger share of vehicles to the US and the US exports a larger share of parts to Canada’, but as many smaller automotive parts are required for major components, ‘it is possible for the same part to cross the border several times’ before arriving at an assembly plant (Citation2012, p. 493). At the same time, the rise of free trade in the 1990s and the increasing implementation of more stringent border security in the 2000s have contributed to the transformation of Windsor and Detroit's border spaces from local points of contact to corridors of global trade, favouring flows of products over people (Rodney Citation2014, pp. 267–269). Stricter identification requirements – passports or enhanced ID cards – introduced through the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative in 2009 have not only slowed cross-border tourism but also blocked the passage of undocumented people who might well contribute to local labour markets on both sides of the border. And while economic linkages through the automotive sector have long defined the cities and neighbouring regions, political cooperation between local authorities has curiously remained distant (Nelles Citation2011). Thus, a peculiar condition of economic interpenetration and political separation contribute to the cultural landscape of the Windsor–Detroit borderlands.

Arguably, one generative cross-border literary and artistic scene evolved in the early years of the renowned Christian Culture Series, initiated in 1934 by Father J. Stanley Murphy at Windsor's then Assumption College (now Assumption University, an institution federated with the University of Windsor), which brought dozens of writers, artists, philosophers and Catholic labour activists to the border cities. In the late 1960s and 1970s, notably throughout Detroit's tumultuous uprisings during the Civil Rights Movement, Windsor-based radio station CKLW's The Big 8 Top 40 show claimed the number one spot in Detroit ratings, introducing numerous Motown and other performers to cross-border audiences. Describing the 1990s Detroit techno scene, Marcel O'Gorman (himself a Windsorite who has worked in both cities) captures the intimacy of the border cities in the clandestine movements of Richie Hawtin, or Plastikman:

For a long stretch of Saturday nights in the mid-1990s, young suburbanites crossed 8-mile road and headed into Detroit's East side, packing themselves like lemmings into the long-abandoned Packard automotive plant. They went there to get high on inner-city danger, ecstasy washed down with Evian, and the thumping sensorium of Detroit's king of darkno, Richie Hawtin, a.k.a. Plastikman. When all the feel-good was rubbed off on the dance floor, and the sun began to rise, they returned to the safety of their homes in So-and-So Woods and Something Hills. Plastikman was the pied piper of apocalypse tourism. Even in 1995, after being banned from the US for 18 months for working without a permit, Hawtin bootlegged himself into Detroit to mix and spin at underground raves. As always, beckoned by word of mouth, deftly designed flyers, and electronic airwaves, the suburban crowds swarmed the abandoned Packard Plant. There is a certain poetry in the scene of a techno DJ working the crowd at an automotive assembly plant. Plastikman, ‘mashing together’ (an expression I have come to despise) deep strings, subsonic base, and an outer-space plink-plonk backbeat, is at home on the assembly line. (O'Gorman Citation2007)

Windsor: border scenes

While Detroit's contemporary experimental art scene engages with abandoned, demolished or ruined spaces in specific neighbourhoods, creative communities in Windsor are challenging states of dereliction by reminding us that the border city is part of a greater urban environment that has constantly experienced spatial transformations. Windsor-based projects on their own may not constitute a scene, in Barry Shank's sense of an ‘overproductive signifying community’ (Citation1994, p. 122). Yet in the context of Windsor's onlooker relationship with Detroit, these projects mobilize local energies in multiple directions. On one hand, they constitute a form of cross-border circulation, a local instantiation of what Gaonkar and Povinelli (Citation2003) have called the movement of the ‘edges of forms’ (p. 391). On the other hand, within Windsor, creative collectives draw on their position as intimate onlookers to propose new forms of connection between Windsor and Detroit, negotiating the ambiguity of the border as simultaneously porous and impermeable.

As with the Detroit-based projects discussed in this paper, creative communities in Windsor are directly and indirectly connected to educational institutions and respond, in Lee and LiPuma's (Citation2002, p. 192) sense, to ‘the interactions between specific types of circulating forms and the interpretive communities built around them’. Straw notes that ‘universities everywhere generate forms of learning and expressive practices that are in excess of their intended function as places for the imparting of formal, disciplinary knowledge. Predictably, universities are important sites for the accumulation of social and cultural capital’ (Citation2004, p. 414). The University of Windsor's School of Creative Arts (merged in 2013 out of the schools of visual arts and music, and programming in cinema) is the locus of creative initiatives that engage border spaces in critical art education and of collectives that have emerged from this school and extended themselves into the scenic life of the city. Border spaces in part generate the school's cultural capital, and allow the school to connect to concentrations of subcultural capital (e.g. through cross-border teaching faculty and local sessional instructors). The overall proximity of the university to the border – the Ambassador Bridge's infrastructure and the university's central campus are integrated within the same geographical space – has fostered on-going student interest in understanding these weird spaces.

Border spaces in Windsor are thus an arena for experimentation in which artists and students work with and against the urban environment. The Green Corridor project, initiated in 2004 by artists Noel Harding and Rod Strickland, a University of Windsor visual arts professor, has sought to reclaim 2 km of the Windsor–Detroit gateway along Huron Church Road approaching the Ambassador Bridge. In its various manifestations as both an undergraduate course and an urban research forum, Green Corridor has challenged the fragmentation of the border environment into seemingly disconnected spaces: the Ambassador Bridge's vast customs and security zone focused on cycles of trade and travel, industrial zones, surrounding communities with a high proportion of low-income residents, and the campus of the University of Windsor itself. This area includes the adjacent blocks of Indian Road, a street of boarded-up houses owned by the American Ambassador Bridge Company as a part of its bid to twin the bridge's span but which Windsor's City Council listed as a designated heritage area in 2007 due in part to a First Nations settlement that once stood nearby. In contrast to these disconnected spaces, Green Corridor treats the entire border region as a total and harmonious environment facing related manifestations of urban crisis.

As Kim Nelson and I have argued (Citation2010), Green Corridor challenges us to rethink the urban spaces of the border in terms of circulation rather than the linear metaphors of corridors or crossings. The project engages the border environment as a fluid space open to innovations in urban design and in so doing shifts the spatial bias of the border from an edge to an environment or field. The complexity of Detroit and its material conditions are not external to this field, but rather are necessarily part of an expanded understanding of borderline spaces as points of resonance. In 2009, for example, Green Corridor staged its Open Corridor intervention: an interactive and site-specific festival of arts, science, performance and community. Designed as a drive-through, open-air gallery along Huron Church Road running south of the Ambassador Bridge, Open Corridor staged public art projects and performances to engage both local and international travellers in seeing and listening. In keeping with Windsor's bid to be seen seeing, this border space was thus momentarily redefined and re-coded as an experience of the local rather than a transnational passageway. A ‘Drive-Thru Symphony’ relied on the participation of car and truck drivers in an interactive performance, a call-and-response exchange activating the corridor through visual projections, text and time-delayed images. Music ensembles performed sound works ‘created in response to the themes of environment, traffic, and shifting time (the time it takes for sound to travel long distances, mobile audiences, and the streaming delay to the FM signal)’ (Green Corridor Project Citation2009). The two-day performance proposed ‘a “sensorial” approach to urbanism that explores how we use sight, sound, and even smell as a means of navigating and understanding the city’ (Green Corridor Project Citation2009).

Much like Detroit's Heidelberg and Power House Projections, Green Corridor is motivated by the same logic of gradual and contemplative transformation, drawing our attention to the integrated material conditions of Detroit–Windsor and the ‘challenges posed by living and working in places that are in critical condition’ (Rodney Citation2014, p. 262). This practice of urban self-reflection is furthered by the BCL, an artist-led creative research collective working to promote civic change by acknowledging and disrupting Windsor's state of crisis. Initiated by local artist Justin Langlois as a research-creation project for his MFA in Visual Arts, the BCL includes a number of student artists with backgrounds in various fields.Footnote1 Since its inception, the BCL has undertaken a range of urban interventions: environmental awareness and ‘self-help’ slogans for Windsorites (e.g. biodegradable, seed-filled balloons emblazoned with ‘You Are Worth It’ for the Open Corridor Festival); the Text-in-Transit project in partnership with Transit Windsor, featuring 100 statements and stories posted as bus advertisements (‘The automobile can only take us so far’ and ‘There is a future here’); and Scavenge the City, ‘algorithmic walks’ based on randomly generated sets of instructions for navigating Windsor. As with Green Corridor, the BCL calls for new ways of mapping Windsor in relation to its own past, articulating a need ‘to create the foundation upon which new border relations can be imagined and enacted in both Windsor and Detroit’ (BCL Citation2011, p. 7). Having obtained an Ontario Trillium Foundation grant in 2012, the group established the Civic Space, a storefront meeting, research and gallery space in an under-populated stretch of Pelissier Street. As with Detroit's Design 99 (which previously established a storefront workshop gallery in Hamtramck) and subsequent Power House Projections, the BCL's success in obtaining a variety of arts funding grants has allowed it to pursue activities ranging from pop-up urban interventions, local workshops, international conferences such as Homework: Infrastructures and Collaboration in Social Practices (2011), and artist residencies such as Storefront Residencies for Social Innovation (2010) and Neighbourhood Spaces: Windsor & Region Artist-in-Residence Program (2013–2014). These residencies have invited multi-disciplinary artists and designers to occupy spaces in Windsor as interventions into the everyday realities of high rates of vacancy and underused properties. The movement of motivated young artists through the university and into the city indicates the intimacy of the local arts community (e.g. Langlois also served as the Director of the municipal Arts Council). The BCL's activities have thus crossed the boundaries between student project, social collective, professional organization and academic think tank. As Straw contends:

the knowledges required for a career in artistic fields are acquired in the movement into and through a scene, as individuals gather around themselves the sets of relationships and behaviours that are the preconditions of acceptance. Here, as in scenes more generally, the lines between professional and social activities are blurred, as each kind of activity becomes the alibi for the other. The ‘vertical’ relationship of master to student is transformed, in scenes, into the spatial relationship of outside to inside; the neophyte advances ‘horizontally’, moving from the margins of a scene towards its centre. A variety of urban media (from alternative weekly newspapers to Internet-based friendship circles) now act as way-finding aids in this process. (Citation2004, p. 413)

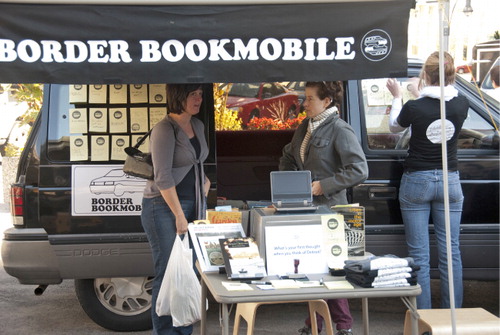

The Bookmobile is an art-research project organized and curated by Rodney, a scholar of urban and visual cultures at the University of Windsor who also leads a senior undergraduate seminar on ‘Border Culture’. Since 2009, the Bookmobile has been housed in a 1993 Plymouth minivan, an emblem of Detroit design made in Windsor's Chrysler Minivan Assembly Plant (). Drawing on Detroit's neglect of its border city status as a starting point, Rodney describes the project as a ‘mobile exhibition of books, photographs, maps, and ephemera on this border region’ as well as USA–Mexico border relations, a ‘memory project’ that seeks to ‘chart the changing relationship between Detroit and Windsor as border cities’ by inviting ‘viewers and participants to produce new narratives about the region that speak to the interrelationship between Windsor and Detroit’ (Lee Rodney Citation2014, p. 255; ).

In its most recent manifestation as the Border Bookmobile Public Archive and Reading Room (2013), an exhibition at the Art Gallery of Windsor alongside contemporary art curator Srimoyee Mitra's program Border Cultures: Part 1 (Homes, Land), the mobile library was turned inside-out allowing visitors to browse the plethora of materials and border memorabilia (from pencils and badges to stamps and playing cards), read and view the many narratives of border crossings that the project has collected, and finally make copies of materials. As with Green Corridor and the BCL, the Bookmobile highlights the border's capacity to facilitate flows of products while often hindering flows of people.

By reifying the otherwise abstract border into specific visual spaces on which to project acts of resistance to the borderland's fragmented character, the Green Corridor, the BCL and the Border Bookmobile all draw attention to strategies for reimagining abandoned structures and underused spaces bound together by the Detroit–Windsor gateway. If each initiative appears staunchly local in orientation, their joint commitment to imagining a different cross-border urban experience is part of the scene's project. As Rodney puts it, ‘if Detroit and Windsor prove to be resistant to gentrification, it is not merely because of the blue-collar legacy; it is because the critical issue facing neighbourhoods is stabilization’ (Rodney Citation2014, p. 262). These initiatives are simultaneously connected to and separate from Detroit's aesthetic community, a community which thus exceeds its own perceived local boundaries.

Conclusion: Detroit ± Windsor

Detroit and Windsor have emerged as sites of a multi-layered experimental art scene deeply embedded in each city's cultural landscape and educational institutions, where ‘collaborative projects aim at neighbourhood stabilization against the tide of foreclosures, abandonment, and arson’ (Rodney Citation2014, p. 262). Inhabiting the space between images of stasis and change, and between patterns of cross-border circulation and impermeability, the activities transpiring within the many projects discussed in this paper work to disorder the material character of urban spaces and the built environment, the people, things and media that pass through them, and even their legal and institutional frameworks. Yet to identify these many projects as a scene also invites us to consider what Straw identifies as the notion's ‘elusive slipperiness’ (2001, p. 252). The diversity of strategies and approaches they employ exceed more tightly circumscribed activities suggested by terms such as art world or movement. Moreover, the very slipperiness of scenes affords us the opportunity to consider cross-border affinities in cultural expression which cannot easily be identified in terms of class, community, or subculture, nor in terms of national strategies for fostering cultural citizenship. Blum's assertion that since ‘the city breeds the celebration of intimacy […] the culture of the city is located as much in its topography of scenes as in its formal institutions of “high art” such as the ballet, opera, theatre district, museums, and galleries’ (Citation2003, p. 183) is applicable to Detroit–Windsor: as cross-border cooperation between political, cultural and even educational institutions is severely limited, scene arguably describes the intimate relationship between site-specific projects afforded by Windsor's onlooker status with Detroit more efficiently.

Yet if a multi-layered art scene connects Detroit and Windsor, it also serves to highlight the distinctiveness of these cities. While Windsor's border-oriented collectives make forays into central Detroit with some frequency, neither city's projects have attempted to maintain a longer-term presence in the other city. And although the projects described on either side of the border are all overtly oriented to civic change or community transformation, their dispersal across multiple sites of encounter and their connections to educational and professional institutions may, arguably, also slow the pace of the systemic change they desire. Against each city's hurry to embed scenic life within officially demarcated cultural districts and economies, the projects I have described are oriented to cautious and considered transformation grounded in dialogue, workshops, research and planning. The sense of intimacy fostered within efforts to stabilize Detroit neighbourhoods is complemented by forms of intimacy between Windsor and Detroit generated through Windsor-based projects that address forms of urban crisis all deeply linked to Detroit's future. Windsor art collectives thus enter into a dialogue with site-specific projects in Detroit as both insiders and onlookers – not in the sense of idle onlookers, as with most ruin tourists, but rather as an audience expressing its deep knowledge and appreciation of Detroit's history and current conditions. In the gradual nature of transformation that these projects espouse, as they contemplate a perhaps unattainable future, the scene is afforded time to contemplate its coming-to-be and its potential perishing.

Notes on Contributor

Michael Darroch is an Associate Professor of Media Art Histories and Visual Culture at the University of Windsor and Director of the IN/TERMINUS Creative Research Collective. He has published essays on art, media, language, and urban culture and is co-editor of the anthology Cartographies of Place: Navigating the Urban (McGill-Queens, 2014). He is completing a book manuscript on transatlantic and interdisciplinary influences on Canadian media studies and the journal Explorations (1953–1959).

Notes

1 The BCL includes Justin Langlois, Danielle Sabelli, Michelle Soulliere, Josh Babcock, Rosina Riccardo, Cristina Naccarato, Hiba Abdallah, Kevin Echlin and Sara Howie.

References

- Anderson, W. P. (2012) ‘Public policy in a cross-border economic region’, International Journal of Public Sector Management, vol. 25, no. (6/7), pp. 492–499.

- Austen, I. (2013) ‘From Canadian oil, a black pile rises in Detroit’, New York Times, 18 May, p. A1.

- Binelli, M. (2012) Detroit City is the Place to Be, New York, Metropolitan Books.

- Blum, A. (2003) The Imaginative Structure of the City, Montréal and Kingston, McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Broken City Lab (2011) How to Forget the Border Completely, Windsor, Broken City Lab.

- Carducci, V. (2012) Envisioning Real Utopias in Detroit [online] Available at: http://motownreviewofart.blogspot.ca/2012/02/envisioning-real-utopias-in-detroit.html (accessed 28 April 2014).

- City of Detroit, Office of the Emergency Manager (2013) Proposal for Creditors [online] Available at: http://www.detroitmi.gov/Portals/0/docs/EM/Reports/City%20of%20Detroit%20Proposal%20for%20Creditors1.pdf (accessed 28 December 2013).

- Cope, M. (2004) ‘In Detroit time’, in Shrinking Cities Working Papers, Volume III: Detroit, ed. P. Oswald, Halle an der Saale, Kulturstiftung des Bundes, pp. 11–12.

- Darke, C. (2011) An Insider's Guide to Detroit's Contemporary Art Scene. Hyperallergic: Sensitive to Art & Its Discontents [online] Available at: http://hyperallergic.com/39737/detroit-contemporary-art-scene/ (accessed 28 December 2013).

- Darroch, M. & Nelson, K. (2010) ‘Windsoria: border/screen/environment’, Public, vol. 40, pp. 56–64.

- Detroit–Berlin Connection [online] (2014) Available at: http://detroitberlin.de (accessed 23 May 2014).

- Deutsche, R. & Ryan, C. (1984) ‘The fine art of gentrification’, vol. 31, October, pp. 91–111.

- Edensor, T. (2005) ‘Waste matter – the Debris of industrial ruins and the disordering of the material world’, Journal of Material Culture, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 311–332.

- Florida, R. (2002) The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It's Transforming Work, Leisure and Everyday Life, New York, Basic Books

- Florida, R. (2005) Cities and the Creative Class, London, Routledge.

- Forkert, K. (2013) ‘The persistence of bohemia’, City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 149–163.

- Gaonkar, D. P. & Povinelli, E. A. (2003) ‘Technologies of public forms: circulation, transfiguration, recognition’, Public Culture, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 385–397.

- Green Corridor Project. (2009) Open City Festival, Windsor, ON, Green Corridor Project.

- Herron, J. (1993) After Culture: Detroit and the Humiliation of History, Detroit, Wayne State University Press.

- Herron, J. (2005) ‘Not from Detroit’, in Urban ecology: Detroit and beyond, ed. K. Park, Hong Kong, MAP Book Publishers, pp. 155–156.

- Herscher, A. (2012) The Unreal Estate Guide to Detroit, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press.

- Karibo, H. M. (2012) Ambassadors of Pleasure: Illicit Economies in the Detroit–Windsor Borderland, 1945–1960. Unpublished doctoral diss., Toronto, University of Toronto.

- Klug, T. A. (1998) ‘The Detroit labor movement and the United States–Canada border, 1885–1930’, Mid-America, vol. 80, pp. 209–234.

- Klug, T. A. (2008) ‘Residents by day, visitors by night: the origins of the alien commuter on the US–Canadian border during the 1920s’, Michigan Historical Review, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 75–98.

- Lang, P. (2005) ‘Over my dead city’, in Urban Ecology: Detroit and beyond, ed. K. Park, Hong Kong, MAP Book Publishers, pp. 10–16.

- Leary, J. P. (2011) Detroitism. Guernica: A Magazine of Art and Politics [online] Available at: http://www.guernicamag.com/features/leary_1_15_11/ (accessed 28 December 2013).

- Lee, B. & LiPuma, E. (2002) ‘Cultures of circulation: the imaginations of modernity’, Public Culture, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 191–213.

- Marchand, Y. & Meffre, R. (2010) The Ruins of Detroit, Göttingen, Steidl.

- McLuhan, M. (1977) ‘Canada: the borderline case’, in The Canadian Imagination: Dimensions of a Literary Culture, ed. D. Staines, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, pp. 226–248.

- Nelles, J. (2011) ‘Cooperation in crisis? An analysis of cross-border intermunicipal relations in the Detroit–Windsor region’, Articulo: Journal of Urban Research, vol. 6 [online] Available at: http://articulo.revues.org/2097 (accessed 28 December 2013).

- O'Gorman, M. (2007) ‘Digital Detroit: tourists in the apocalypse’, CTheory [online] Available at: http://ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=586 (accessed 28 December 2013).

- Park, B. (2005) ‘Going to Detroit’, New York Times, 28 August, travel section, pp. D13.

- Park, K., ed. (2005) Urban Ecology: Detroit and Beyond, Hong Kong, MAP Book Publishers.

- Power House Productions [online] (2013) Available at: http://www.powerhouseproductions.org (accessed 28 December 2013).

- Redgrave, A. (2013) ‘Motor skills/Les moteurs du changement’, enRoute, April, pp. 45–52.

- Rice, J. (2005) ‘Detroit taggin’, CTheory [online] Available at: http://ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=484 (accessed 28 December 2013).

- Rodney, L. (2009) ‘Detroit is our future’, Fuse Magazine, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 6–12.

- Rodney, L. (2014) ‘Art and the post-urban condition’, in Cartographies of Place: Navigating the Urban, eds. M. Darroch & J. Marchessault, Montréal and Kingston, McGill-Queen's University Press, pp. 253–269.

- Rosler, M. (2011) ‘Culture class: art, creativity, urbanism, part III’, E-flux Journal, vol. 25 [online] Available at: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/culture-class-art-creativity-urbanism-part-iii/ (accessed 28 December 2013).

- Shank, B. (1994) Dissonant Identities: The Rock'n'roll Scene in Austin, Texas, Hanover, NH, Wesleyan University Press.

- Silver, D., Clark, T. N. & Graziul, C. (2011) ‘Scenes, innovation, and urban development’, in Handbook of Creative Cities, eds. D. E. Andersson, Å. E. Andersson, & C. Mellander, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, pp. 229–258.

- Silver, D., Clark, T. N., & Yanez, C. J. N. (2010) ‘Scenes: social context in an age of contingency’, Social Forces, vol. 88, no. 5, pp. 2293–2324.

- Steinmetz, G. (2008) ‘Harrowed landscapes: white ruingazers in Namibia and Detroit and the cultivation of memory’, Visual Studies, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 211–237.

- Straw, W. (2001) ‘Scenes and sensibilities’, Public, vol. 22/23, pp. 245–257.

- Straw, W. (2004) ‘Cultural scenes’, Loisir et société [Society and Leisure], vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 411–422.

- Stryker, M. (2013) ‘Fire claims part of Heidelberg Project, but the art, like Detroit, will survive’, Detroit Free Press, [online] Available at: http://www.freep.com/article/20130503/COL17/305030120/heidelberg-project-guyton-fire-detroit (accessed 4 May 2013).

- Sugrue, T. (2005) The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press.

- Vergara, C. J. (1995) ‘Downtown Detroit: American Acropolis or vacant land?’ Metropolis, April, 33–38.

- Vogel, S. (2005) ‘Surviving to create’, in Urban Ecology: Detroit and Beyond, ed. K. Park, Hong Kong, MAP Book Publishers, pp. 16–19.

- Yablonsky, L. (2010) ‘Artists in residence’, New York Times, 22 September [online] Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/26/t-magazine/26remix-detroit-t.html?_r=2&adxnnl=1&adxnnlx=1285758007-VD4winfKUrKGnXhLddn9+w (accessed 28 April 2013).

- Yablonsky, L. (2011). ‘Art motors on’, W magazine, November [online]. Available at: http://www.wmagazine.com/culture/art-and-design/2011/11/detroit-art-scene (accessed 28 April 2014).