ABSTRACT

This article explores spatial and cultural transformations that are taking place in the Ecuadorian Amazon region under an extractivist development model. Taking as a case study the Millennium Communities project Playas de Cuyabeno, it analyses from a critical perspective the origins and configurations of a space and architecture of extractivism in the Amazon forest. Discursively, the Ecuadorian legal framework and authorities claim to be distant from neoliberal tendencies and to promote the conservation of nature and the achieving of Buen Vivir (‘Good Living’). In practice, however, they are triggering and imposing an ideal of urbanity and a future city that serves political purposes and happily coexists with oil extraction. Even if Playas de Cuyabeno also reflects the elusive spirit of cultural practice and its capacity to escape homogeneity by creating new forms of inhabiting the designed spaces, it most insistently marks the complicity between the authorities’ rhetoric of modernity/progress and their intention to discipline the space and the subjects living in it.

Introduction

To conceive of a space as a produced space (Lefebvre Citation1974) implies to critically analyse the production of categories in which this space is read and decoded in specific periods of time. Accordingly, in order to understand how spatial transformations affect human interactions, it becomes necessary to assume and reveal the dialectical relationship between people and their spatial surroundings. The interstices, textures, gaps and voids of a defined space are constituted by and constitute bodies that internally replicate the external conditions of a political and social struggle (Vidler Citation1992). In that sense, every society (and also, as Lefebvre argues, each mode of production) produces its own space and material forms according to its interests and internal dynamics. From that perspective, taking as a point of departure this conceptual approach towards space and focusing on the urban and cultural transformations promoted by the State in the Ecuadorian Amazon region, the aims of this article are threefold: first, to understand the model of development and the political discourse underlying the urban planning process in the Ecuadorian Amazon region; second, to describe the origins of the project and the aesthetic of the constructions and third, to explore what I call the space and architecture of extractivism, which is the amalgamation of the political discourses sustaining the intervention, the transformation of the space reflected in the aesthetic of the buildings and residencies constructed in the Amazon region and the responses of the inhabitants to the new space.

My interest in the development of the Amazonian region started 15 years ago when, visiting as a tourist and working with international organizations, I had the opportunity to talk with ‘colonos’Footnote 1 and indigenous inhabitants of Amazon provinces. By then, their main concern was their feeling of invisibility and abandonment by the State and the continuous marginalization from any benefit of economic growth. During the following years, while working in planning and territorial development, observing the increasing presence of governmental authorities in the region finally led me to include the case of the Millennium Communities (MCs) in my doctoral research. Following an inductive model of research, I investigated the MCs project – the context, the political discourse and the ideas of development related with this region – for 15 years ago one year. I talked with key actors involved in the project and finally, combined and contrasted this information with a visit to the new houses. This case study is highly context dependent, therefore, does not seek to find explanations, but to promote a better understanding of the processes underlying spatial transformations, as well as to stimulate discussions between scholars and urban planners.

Political discourse and development

The MCs are small villages in Ecuador erected by the government of Rafael Correa Delgado, in power since 2007. The first communities inaugurated were Playas de Cuyabeno and Pañacocha, in October 2013 and January 2014. Both are located in the Amazon region (Sucumbios province), which for many decades has been considered geopolitically important due to the diversity and multiplicity of natural resources found there. The two communities were constructed on the lands of the Kichwa, which is 1 of the 10 ethnic indigenous groups coexisting in the region. Even if the physical size of the MCs is relatively small (12.2 and 14.51 hectares, respectively), they are only the first of at least 200 new communities the government plans to construct in order to build a new Amazonia in the hydrocarbon and mining zones (Andes Citation2013). Due to the magnitude of the governmental intentions, the first step to uncover the motivations and imaginaries underlying this plan is to explore the two models of ‘development’ suggested by and visible in this initiative, which overlap and interact with each other.

The first model reflected in the main characteristic of the MCs project is the new extractivist model of development. While the old or conventional model was based only on the exploitation of resources for the exportation and economic growth, in the new extractivist model the State and social aspects play a key role in the productive process. The key characteristic of the new extractivist model, which, significantly, has become the basis for policy development by both neoliberal and progressive Latin American governments (Acosta Citation2013), is to present the exploitation of natural resources as providing immediate entry to the paradigms of progress, seen as based on centralized control over the economy and on the implementation of ‘development projects’ (Gudynas Citation2013). Following this trend and focusing on the idea of social improvement, the development of infrastructure was considered as one of the main pillars for growth, progress and poverty alleviation during the first term of Correa’s presidency in Ecuador, and the exploitation of natural resources as the main source for financing this policy

Apart from the variety of facilities constructed by the government using the revenues of the exploitation of natural resources, in the Ecuadorian case, the new extractivist model is accompanied by a political discourse centred on the construction of a positive imaginary towards the oil extraction, perceiving it as a possibility for salvation. Such discourse has its basis in a long history of exploitation and exclusion of the Ecuadorian Amazon provinces. Approximately since the 1970s (the beginning of the ‘Texaco Era’), due to the detection of oil, the region has been of geopolitical interest and subject to invasion and control by oil companies and governments eager to push forward oil extraction. Nevertheless, since the extraction started until the beginning of the second millennium, the situation of the provinces in this area had not improved significantly economically, socially or politically (Bustamante and Jarrín Citation2005). The Ecuadorian population, moreover, has had little or no influence on the process of extraction, while indigenous communities have seen their livelihoods come under threat as they have been marginalized and excluded in its wake. In terms of the environment, oil spills, deforestation and epidemiological effects have been associated with oil extraction, and many conflicts have emerged in response and opposition to the continuing pollution in different parts of the Amazon region.Footnote 2 As a result, inhabitants of the Amazon provinces and intellectuals have called oil exploitation and its consequences ‘the curse of oil’.

Due to this largely negative experience with oil exploitation, the current political discourse is introducing a whole new conceptualization of oil extraction into the imaginary of Ecuadorian citizens by stressing the idea that natural resources handled well are a blessing and not a curse (Correa Citation2013), and by linking extraction with the possibility of a positive and radical change of life in the Amazon region. For example, during the inaugural speech in one of the MC’s, Correa and other authorities identified the community as an example of the wonders that oil and mining can create when managed with white hands (without corruption), while also emphasizing that ‘now [the oil] is for everybody and not only for the groups in power’ (El Telégrafo Citation2014).

The second development model sustaining the construction of the MC’s is that of Buen Vivir and the ‘Rights of Nature’. From the beginning of its mandate, the president’s political party Alianza Pais openly expressed its opposition to the narrow idea of development coming from neoliberal contexts (based only in economic growth) and, after discussions with social and indigenous movements, the Rights of Nature and the concept of Buen Vivir were included in the Constitution of 2008. The notion of Buen Vivir was taken from the indigenous Kichwa concept of Sumak Kawsay, which alludes to a nonlinear notion of growth that is not based on the binary opposition of underdevelopment and development. Rather, Sumak Kawsay or Buen Vivir is based on relationships of reciprocity and strong ties of mutual trust, not only between humans but also between humans and nature (Calapucha Citation2012). Sumak Kawsay also alludes to knowledge about life that allows the person and the community to take care of the environment which is in perfect condition, well maintained, protected and free from pollution. Alongside Sumak Kawsay, the Rights of Nature are also part of the Constitution of 2008, recognizing among others, that ‘Nature, or Pacha Mama, where life is reproduced and occurs, has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes’ (Ecuador. Constitution Citation2008 art.71).

With the introduction of this model of Sumak Kawsay and the Rights of Nature, it seemed as though the relation between the government, the citizens and nature would take another route, opening up a wide range of possibilities to rethink, plan and reinhabit the Amazonian space. Moreover, the president emphasized the importance of preserving the cultural richness of the ancestral groups in the MC’s, arguing that misery and poverty are not part of the ‘folklore’ or ‘identity’ of the indigenous peoples. For him, thinking that indigenous people could not live comfortably or receive a good education represented ‘racist stereotypes disguised as a defense of ancestral peoples’ (Correa Citation2013).

What has become clear from this discussion of the Ecuadorian political discourse and the two models of development, however, is their inherent incompatibility. The main problem with new extractivism is that it is part of an ideology of development nurtured by ideas of Modernity, which, even when trying to free itself from neoliberal legacies, is still obsessed with the idea of progress (Gudynas Citation2009). Moreover, it is liable to produce environmental damages, which is one of the main reasons why this model has been contested by strikes and protests against mining and oil exploitation in biodiverse and legally protected territories in the Amazon region.Footnote 3 Consequently, it is far away from and in continuous tension with Sumak Kawsay and the Rights of Nature proposed by the Ecuadorian Constitution. In the next section, I will analyse in detail the case of Playas de Cuyabeno to characterize the spatial dimensions of this tension and the configuration of what I call the space and architecture of extractivism.

Violence and the modernity/coloniality legacy

The history behind the first MC project, Playas de Cuyabeno, is important for understanding the struggles shaping the space. Apart from the political discourse previously described, the origin of the construction of this MC was marked by an act of violence. In October 2008, heavy machinery owned by Petroamazonas (the national oil company), under military protection, entered Playas to start the oil exploration in the area. Taken by surprise, the residents of Playas contested the intrusion and confronted the military forces. Three hundred soldiers were mobilized by helicopters (El Universo Citation2008) and teargas bombs and rubber bullets were used to scatter the people. The intrusion was severely criticized by the community residents for disrespecting the procedures and rights guaranteed by the Constitution (Ecuador. Constitution Citation2008 art. 57 sec.7). Only after the military intrusion was denounced in the media by diverse Amazonian indigenous groups did the government promise to resolve the problem in consultation with the affected communities (Montesdeoca, L. Vice director of the Millennium School Victor Dávalos, personal communication, 18 Jan 2015).

Once the consultations had begun, residents of the community turned out to be divided, with some wanting oil exploitation and others not. The government suggested the construction of the MC as a compensation measure, offering for that purpose a budget of 22 million dollars. Finally, the community accepted to construct the project. According to Barcelino Noteno, the president of the Kichwa community, this was at least in part because the MC was seen as an opportunity to escape from isolation and marginalization, and also because it was understood as a ‘must’ since sooner or later the government would start to exploit the area anyway (Noteno, B., personal communication, 19 Jan 2015). As he mentions:

After a big war, finally they convinced us to construct the city. [ … ] My intention was good … I talked with the fellows and I told them: Considering that they will exploit the petroleum here … they have to build us a good infrastructure, a health center so we can die in a quality bed, otherwise only them can die in a good bed, not like us, dropped somewhere with some disease. (Italics by the author)

After the approval the government decided to build the MC in a period of one year. The new MC was erected in the former community, which implied the displacement of the inhabitants to temporal residencies until the works were finished. With the construction of the houses the government demonstrated the inhabitants that, thanks to the oil exploitation, it was producing a radical change in the living conditions of people in the Amazon region. Nevertheless, as one of the managers of the project argues (in a conversation off the record), to construct a whole new community for the Kichwa group technically was not necessary, because the Kichwa Community already had houses that could had been only remodelled and improved with the installation of basic services. According to the same key actor, the construction of the houses was realized mainly as part of a ‘Plan B’ related to the Yasuní-Ishpingo, Tambococha and Tiputini initiative (Yasuní-ITT).Footnote 4 This governmental initiative aimed at keeping the oil in the ground to protect the Amazon region, but it was put aside in 2013 as economically unaffordable, despite criticisms by citizens, indigenous groups and non-governmental organizations.Footnote 5 Since technically the construction of a whole new community was not that necessary, it could be said that the construction mainly fulfilled the political purpose of showing the benefits of the oil exploitation. At the end of 2013, the Millennium Community Playas de Cuyabeno was inaugurated. With it, in the middle of the Ecuadorian Amazon region a new model of urbanization was presented as the future of the Amazonia and as one of the most important benefits of oil extraction.

The modernist legacy is fundamental to explore the space created by the MCs project. Indeed, it would be impossible to understand the MC’s without evoking the architectural and urban projects of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in which the design of the city was seen as a vision to be fulfilled erasing any sign of the past. The modernist urban desire was ‘to construct a theoretically water-tight formula to arrive at the fundamental principles of modern town planning’ (Le Corbusier Citation1987, p. 328) and to construct rules and principles that could be used in any system of modern town planning, no matter where it was located. The new ideal city was built on a clear site, an empty space, and constructed geometrically, using predetermined constructions designed independently of the particularities of the territory, context, history or tradition.

The consequence of geometrical planning, as Le Corbusier argued, was repetition and mass production: ‘repetition dominates everything. We are unable to produce industrially at normal prices without it; it is impossible to solve the housing problem without it’ (Le Corbusier Citation1987, p. 430). The modernist house was conceived as a ‘house-machine’, which had to be practical and emotionally satisfying, while also being designed for a succession of tenants:

the idea of the ‘old home’ disappears, and with it local architecture, etc., for labor will shift about as needed, and must be ready to move, bag and baggage. The words ‘bag and baggage’ will do very well to express the kind –the ‘type’- of furniture needed. Standardized houses with standardized furniture. (Le Corbusier Citation1987, p. 444)

In the Millennium Community Playas de Cuyabeno this modernist legacy is present in different forms. The space of the MC’s, in terms of its architecture, is reduced to a fixed and neutral background acting as a ‘mere container or stage for the human drama’ in the terms Edward Soja used when talking about Western social thought concerning space during the nineteenth century (Soja Citation2006, p. xvi). As is clear from the name MCs, the project evinces anxiety about the future, implying the idea of dragging the Amazonian Region into the twenty-first century or the new millennium (which, paradoxically, was already not new anymore at the time of construction) and suggesting a desired future in which the Amazonian region is projected as an urbanized territory. The first step towards this urbanized aspiration was to destroy almost all the buildings that were previously part of the Kichwa community such as some residential houses and a communal house for meetings and social activities. In personal communication one of the managers of Petroamazonas (who prefers to stay anonymous) argues that from the beginning, the ringmaster was time and the priority was to build the new houses as rapidly as possible. Consequently, factors such as the sustainability or the aesthetics of the buildings were not considered. Modular and standardized design was used to reduce the cost and time of construction, as is characteristic of other infrastructure projects implemented by the government (Correa Citation2012; Manager Petroamazonas, personal communication, 28 Feb 2015).

The result of this complicity between a political necessity and a race against time was a new community – a new city – based on a homogenized and regimented distribution of space (). All the houses have a green roof and are located in rows. They are configured in a symmetrical pattern: the distance between the houses is about 15 meters and the main streets have right angles, giving the impression of a military camp. More specifically, the buildings evoke and follow an aesthetic and infrastructure similar to that of the Petroamazonas oil fields, which use the same colours and the same principles of rational division. This is hardly a surprise, since the people in charge of constructing the MC were Petroamazonas engineers, for whom it made sense to design the community in the image and likeness of what they already knew. The material result observed in the MC is a residential complex where, when looking at it for the first time, is difficult to determine whether the owners of the new houses are the residents, the government or the oil company. However, as I will show in the next pages, is possible to hypothesize that the inhabitants of the MC are being perceived as Petroamazonas employees (which many of them are) and that this is why they are subjected to the national oil company’s rules and spatial structuring.

Figure 1. Millennium Community Playas de Cuyabeno 1. Photo taken by the author, January, 2015 © (Alejandra Espinosa).

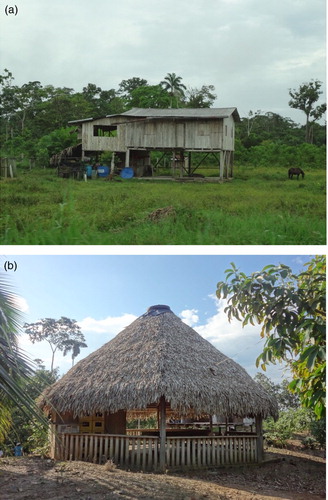

The use of materials also provides clues as to the logic underlying the MC’s use and spatial organization. The houses in the MC’s are stilt houses with white walls, made using iron rods and concreteFootnote 6 (). This is a radical departure from the traditional houses in the Ecuadorian Amazonian region, which are made from wood and palm leaves, elements capable of regulating the temperature in an environment characterized by high temperatures, frequent rain and humidity ().

Figure 2. Playas de Cuyabeno House. Photo taken by the author, January, 2015. © (Alejandra Espinosa).

Figure 3. (a) and (b). Traditional architecture in the Amazon region. Photos taken by the author, January, 2015. © (Alejandra Espinosa).

Apart from the use of different materials, the rational use of the space shown in the MCs is distant from the perceptions and concepts used by the Kichwas to understand the forest. Traditionally, the Kichwas have perceived the forest as a resource of life and spiritual energy, and many Kichwa concepts proclaim a connection between the space and spirits (Noteno, E., personal communication, 17 Jan 2015). They use, for example, the dynamic concept of llakta to designate the created space, which involves an environmental and spiritual dimension. According to this concept, the territory is shaped by the space–soil, the space–water, the space–forest and the spiritual space (Calapucha Citation2012). In other words, llakta comprises a system of social, cultural, spiritual, political and historical relationships that are part of an integrality composed of space–time–water–soil–wind and based in a physical, biodiverse territory (Calapucha Citation2012). The concept of sacha, moreover, is used to refer to the space inhabited by animals, plants and local spirits. At the same time, sacha harbours a spirit called Amazanka, which is the most important spirit of the Kichwa world. It is a masculine spirit, owner and protector of the animals of the forest, and it has the ability to appear in the shape of any animal (Calapucha Citation2012). Unfortunately, although these concepts are harmonious with a notion of an integral unity between the settlement and the environment, they are not considered at all in the MC’s project. Instead, the past is disavowed in the Millennium project, as everything is made to look new, renovated and ‘urban’.

Regarding the importance of keeping traditional designs, paradoxically, during the inaugural speech president Rafael Correa pointed out that it was the government’s intention to be more demanding in relation to the design of future new projects, and that it is possible to do modern houses while also maintaining aspects of Cofán and Waorani (indigenous groups) traditional architecture. ‘In this case’ he added, ‘we will assume a little bit of a dominant role. It is not worth constructing houses made of cement everywhere with the same design if we have a beautiful tradition of housing from the Waorani, Confanes, Shuar, Achuar … ’ (Correa Citation2013, p. 20, translation by the author). Yet, according to Felipe Borman, the president of the Junta Parroquial (the administrative level of government in charge of the area where the community is located), during the process of construction of the new houses the government did not consider the culture and identity of the people. For him, what the government tried was to urbanize the people to make them lead a modern lifestyle (Borman, F., personal communication, 19 Jan 2015) ().

Figure 4. Inauguration of the Millennium Community Playas de Cuyabeno 2. President Rafael Correa with indigenous people 1. 1 October 2013. Photo by Walker Vizcarra. Reproduced by permission of Walker Vizcarra.

However, it is important to mention that the type of housing was discussed with the Kichwa residents prior to the construction, and they agreed to not use traditional designs and materials. This is understandable knowing the context and history of the region. Kichwa indigenous traditional houses have changed shape over time, and traditional concepts about Nature are rarely put in practice in Amazonian cities, mainly because of the growing introduction of a discourse that repudiates ancestral and local practices, appointing any trace of indigenous tradition as ‘undeveloped’. As a result, many of the indigenous communities have created a necessity and a self-imaginary about how their future must be, assuming the idea of living in an urbanized area as synonym of a good and better life.

This probably explains why, when the architecture of the houses was ‘discussed’ among the Kichwa, they preferred to use materials similar to cement instead of wood and palm leaves, arguing that they deserved houses made of the same materials as those in the city (perceived as a developed space). As a testimony presented in the newspaper shows: ‘[During the inauguration of the MC] Bolívar Tapou from the [indigenous] community Tarabiayo asked the president to construct the same kind of houses in his community because they also want to be part of the progress’ (El Telégrafo Citation2013, italics added). Similarly, Barcelino Noteno, the president of the Kichwa community, explains:

We took our position, we claimed our right as indigenous people with ancestral territories. We said that not only developed provinces are in need. We are also Ecuadorians, which have been living here forever, we want decent housing, decent education, decent infrastructure, as any human being. [We told the government that] we also wanted good hospitals, a school, as in any other city. And also skilled teachers so we can have a quality education. I don’t think that they [the government] will keep us, for being indigenous people, all our life marginalized. (Noteno, B., personal communication, 19 Jan 2015. Translated by the author)

Even if some residents of the MC perceive that the quality of life of the people living in the community is quite better than before (Borman, F., personal communication, 19 Jan 2015) the problem with the spatial transformations implemented by the government and their reproduction of modernity’s rhetoric is that they carry with them a darker side, which is coloniality (Mignolo Citation2007). As the dark and constitutive side of modernity, coloniality is understood as the rhetoric of salvation and newness that started to dominate in the colonial processes of the sixteenth century, and that was accompanied and articulated on the basis of ontological and epistemic differences, locating indigenous or native people as ontologically lesser human beings and, consequently, not fully rational. A whole colonial matrix of power was constructed, resulting in the dominion and control of subjectivities, authority, economy and knowledge. The reproduction of this local and internal colonial matrix is visible in the management and construction of the MC. Beginning with the use of violence as a first act, the government, mainly through the oil company, is establishing rules to control and urbanize the community, using a political discourse that reproduces the rhetoric of salvation, civilization and progress in service of its own (mis)understanding of Sumak Kawsay/Buen Vivir.

The desire to control space is combined with the desire to discipline the inhabitants of the MC, and to monitor the aesthetic of the houses in order to guarantee and promote ‘good’ habits. For example, even if the community’s main activities are agriculture and fishing (Araujo Citation2013), to have crops within the MC is forbidden by the oil company, so the inhabitants need to commute frequently (mainly by canoe) to work their lands, which are located away from the MC, some of them approximately five kilometres away but others 10 or more. In order to keep the clean appearance of the houses, it has also been prohibited to have domestic animals or to make any changes to the facades for at least two years. Alongside with this rule to keep the facades clean and homogenized, the biggest buildings (the Millennium School and the Coliseum) are decorated with the Ecuadorian ‘country logo’ (). In 2010 this logo, which ‘is based in the sun, in life, in the soil, in mega diversity, in pre-Columbian designs, flowers, fauna [ … ]’ (Ehlers in La Hora Citation2010), was created by the Ministry of Tourism to promote the country abroad and it quickly became a State brand. Together with the slogan ‘Ecuador loves life’, it intends to reflect that Ecuador is a diverse, pluricultural country, as is also stated in the Constitution, where it is noted that the country treats with respect the diversity of groups within its territory and the institutional, social and cultural differences between them. In the MC, the country logo thus appears as a brand of the State and of national identity, showing visitors that the communities were built by the government as part of its commitment to pluriculturalism that, however, finds no real expression in the way the MC is constructed and managed.

It is important to underline the way the shadow of this modernist legacy hangs over the MC’s, shaping the extractive space: The rigid spatial segregation of the MC from its environment makes it easier (and cheaper) for the planner, or in this case the government, to construct social housing, but beyond that, it facilitates the creation of a future city where Amazonian communities can live happily together with the oil camps and extractive activities. What seems to be behind this architectural transformation of the space is a clash between, on the one hand, the intention to construct a new Amazonia and to promote national development (which gestures towards the plural but also needs to bring all Ecuadorians together) and, on the other, the history of the residents and the space, which is ignored. The narrative supporting the creation of the MC’s is based on an idea of progress, spatial homogenization and rationality, which, in the communities’ architectural execution, is visible in the straight lines, the white walls and the controlled vegetation, as well as in the rules implemented to discipline the residents. Therefore, similar to the modernist project and coloniality as its darker side, the space of the MC’s represents a monopolistic interpretive power that is also diffusionist, intended to interpellate others from a centre (Pratt Citation2002). In the end, the indigenous communities are not really consulted, but interpellated into participation from the centre through a discourse of progress that they find hard to refuse.

The production of the uncanny and new dynamics of the use of space

Walking through the streets of Playas de Cuyabeno in 2015, a little more than a year after the MC’s inauguration, it was already possible to see the effects of weather conditions and daily use on the buildings, which seemed to be waging a constant battle with nature. In the Coliseum for instance, some of the lights did not work and the basketball hoops were in very poor condition. In the boarding school, damages caused by moisture were visible. The oil company also had to build an expensive barrier to prevent the river from flooding the MC. While the decay was not as evident thanks to ongoing maintenance performed by the oil company, it was clear that the moment these efforts stop, a process of rapid degradation will commence. As such, it was possible to see an interesting replication of temporality: the community was constructed at extreme speed, but had also started to deteriorate almost immediately.

The temporality of constant change observed in the MC seems to be in harmony with the temporality of the oil company, which is one where oil needs to be kept flowing at all times. In the Petramazonas ‘Corporate Magazine’ in 2009, José López, the company’s manager of social responsibility and community relations, explained that Petroamazonas aims to always work with efficiency because in the oil industry any hesitation or mistake could be very expensive. Paraphrasing López, the article explains that ‘because it is a company of the State, the oil company measures the results in terms of the oil obtained, that is to say, time is measured in oil barrels’ (Petroamazonas Citation2009, p. 13, italics by the author). As long as the company is in charge of the MC’s maintenance, the buildings will remain standing, but once oil extraction finishes in the region, who knows. Given the problems with infrastructure and the high maintenance costs, Barcelino Noteno, the president of the Kichwa community, admitted in January 2015 that he would not recommend starting a similar project in other communities in the area (Noteno, B., personal communication, 19 Jan 2015).

Alongside the threat of rapid degradation, empty spaces are showing up in different forms as a reminder that this is an artificial community. The residents of Playas de Cuyabeno, for example, are only partially living in the houses. Many of them prefer to spend most of their time on the farms (fincas) where they have animals and crops. This is why many of the houses are only partially occupied and some even uninhabited. The uninhabited houses are being used for storage or simply stand there, like Lego houses dropped on a carpet. Other examples of empty spaces are the cemetery and the market. The cemetery is located in the most remote part of the community; made from cement, it exudes emptiness and degradation. Its walls (once white) are already becoming grey and mildewed. In 2015, residents mentioned that so far only two bodies have been placed in the niches. Even the manager of Petroamazonas interviewed mentioned that the cemetery had not been used because, in Kichwa tradition, the deceased are buried near to the houses where they lived (Manager Petroamazonas, personal communication, 28 Feb 2015). In other words, the cemetery is a space for the dying that is itself dead. In the case of the market, it was built according to desk plans made by the oil company; the community never had a space designated as a market and consequently has no use for it. All these dying and empty spaces contribute to a sense of walking through a community maintained by force at constant risk of vanishing. It is an artificial space, built to be an example of new urbanization and development, but not lived as such.

Analysing the whole project and specifically the empty and dying spaces in the community, a hypothesis arises that a sort of extractive-uncanny space and structures are emerging as a result of the government’s radical spatial and architectural intervention. Following the Freudian concept of Unheimlich, which literally means unhomely and refers to ‘something that is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated’ (Freud cited in Lindner Citation2009, p. 94), in his book The Architectural Uncanny (Citation1992), Anthony Vidler defines the uncanny as a concept that evokes nostalgia and the ‘unhomely’, notions that are connected with a sense of estrangement, alienation, exile and homelessness reflected in architectural shapes. The concept of the uncanny opens up dilemmas about the self in terms of the relation between the body and space, the psyche and the dwelling; it is a movement, a transformation that is a product of modern and modernist imaginaries ‘of something that once seemed homely into something decidedly not so … ’ (Citation1992, p. 6). In the uncanny spectrum, unhomely houses are described as houses that generate a non-specific feeling, a sense of abandonment, real or imaginary, nostalgia, fear, among others. The structures of the MCs are evoking precisely this sense of estrangement. For the inhabitants of the MC, the entire space they knew became new, it was planned and imagined following parameters from outside, other realities, and changed drastically their living conditions. In the empty and dying spaces of Playas de Cuyabeno, it is possible to perceive something disturbing and strange, a sense of lurking unease, an uncomfortable sense of haunting (Citation1992, p. 23), which, in this case, would be the haunting of a desire for progress imposed from the outside, but also appropriated by the community.

The implications of this irruptive urbanization and production of uncanny space and structures are not only visible in the disused parts of the infrastructure, but also in what the residents do with the spaces they do use. Even if the desire to be part of the country’s ‘progress’ is transversally present in the whole community, in its bodies, practices and statements, some gestures and actions reflect a need to resist this model and to reconfigure it in a distinctive way. Infinitesimal and more comprehensive transformations are wrought in order to adapt the new spatiality to their own interests and their own conventions, generating a particular culture of everyday life within the dominant cultural model (De Certeau Citation1984, pp. xiii–xiv). Everyday life emerges as a sphere of resistance, taking shape not as overt opposition but as a process that slowly develops and that includes both preservative and inventive forms of appropriation (Highmore Citation2002). It evidences an ‘inventiveness’ through acts of appropriation and through the redeployment of materials, procedures and tactics, which, together, compose the network of an antidiscipline (De Certeau Citation1984, p. xv). This is exactly what can be observed in Playas de Cuyabeno; the residents, consciously or unconsciously, refuse in different ways to be fully interpellated by the domineering modernist vision.

One of such anti-disciplinary responses can be discerned in the attitude taken by the residents to the monthly payment for services. When the MC was being constructed, neither the residents nor the engineers-planners considered the sustainability of the buildings and of the way of life they imposed upon the families living in them. As mentioned by an employee of Petroamazonas who was working with the community:

No prior social assessment was carried out before the constructions. The government sold an idea … how could I say? It sold an idea to start oil activities … but without prior social assessment. We should know that the Kichwa people have been all their lives hunters, gatherers (… .). If you ask the people about how they see the new community … you will see that the infrastructure has generated needs. Needs. Now the people will need to work to pay the basic services. (Employee Petroamazonas, personal communication, 19 Jan 2015. Translated by the author)

… when they were building the Comunidad del Milenio they didn’t think in a long term how was it going to sustain itself and that is a big problem. Just sustainability in the whole community like the public infrastructure, they didn’t take into consideration that. And most important is that they didn’t take into consideration the sustainability of the families, how they were going to sustain their houses. Now they have electricity, pumping water, which the government started to charge, you know, like everybody else. (Borman, F., personal communication, 19 Jan 2015)

Another response in the sphere of inventiveness is the creation of neighbourhoods with their own identity. The MC is formally divided into blocks and each block has a number. Nonetheless, as mentioned by some residents, the blocks have become neighbourhoods and each neighbourhood has a name and celebrates certain festivities. For example, there is the neighbourhood ‘January 12’ and the neighbourhood ‘May 2’, recalling dates of importance to the inhabitants. Significantly, there are no signs on the streets or on the houses showing the name of the neighbourhood (in accordance with the prohibition of changes to the facades). Yet as an invisible dynamic, the creation of neighbourhoods disrupts the homogeneity and the visual repetition of the MC. The neighbourhoods also participate in the minga, a collective activity for the benefit of the community. Following Kichwa tradition, once a month, all the families gather to clean the streets and other public places. Before the communal minga, each neighbourhood must ensure the cleanliness of its block, and families that do not follow this rule are punished with a fine. The consumption of chicha (a typical Kichwa drink) is also part of the minga.

Besides the creation of neighbourhoods and the maintenance of the minga tradition, some changes have been made in the structure of the houses, mainly on the ground floor. Few families have closed off the ground floor, adapting the area as a business (), storage room or place of leisure. The businesses are primarily grocery stores (there are seven in the MC), with the space modified to welcome customers, who can also take a seat outside. Other types of businesses construct canoes or carry out mechanical repairs (). There are also bars (two or three), which are deliberately made difficult to distinguish, since not all of them are currently legal ().

Figure 6. Store ‘Gaby’ – Millennium Community Playas de Cuyabeno, February 2015. Photo by author. © (Alejandra Espinosa).

Figure 7. Family business – Millennium Community Playas de Cuyabeno, February 2015. Photo by author. © (Alejandra Espinosa).

Figure 8. Bar – Millennium Community Playas de Cuyabeno, February 2015. Photo by author. © (Alejandra Espinosa).

Changes to the prescribed use of time can be also pointed to as part of the MC inhabitants’ anti-disciplinary conduct. Since traditional activities (such as having crops or raising animals) are restricted in the community, the new infrastructure has led to an expansion of leisure time and some of the residents interviewed said they feel bored and prefer to stay in the fincas (Noteno, B., personal communication, 19 Jan 2015; Yumbo, R., personal communication,16 Jan 2015). To fill the time, it is common for families to organize parties that can last for more than 12 hours; an activity that is far removed from the oil company’s mantra of time is money.

The latter example of anti-disciplinary practice also opens up the discussion of the reverse situation, as the changes enforced in the use of time reveal that disciplining is taking place, effectively, and that the residents are being affected in a way that is favourable to the pursuit of oil exploitation. The expansion of leisure time is not only an effect of the restrictions imposed inside the community in order to keep the residents organized, but also an effect of the economic changes caused by the presence of the oil company in the area. Many residents work, directly or indirectly, for the oil company and most of the families receive monetary ‘bonuses’ every time it needs to conduct the seismic explorations to find oil. This has created an economic dependency on the oil company, causing them to prefer to stay in good terms with it. Economically speaking, when the head of the family works for the oil company, the family income surpasses the amount needed to fill basic needs. Consequently, many inhabitants have plenty of free time. Almost every house in the community has the television on for the whole day, showing North American movies, morning shows and governmental announcements. The residents express that more and more, the younger generation prefers to stay in Playas de Cuyabeno to use the computer or watch television instead of going to the fincas. They no longer want to fish or farm like their parents, and are also not interested in speaking the Kichwa language (Noteno, B., personal communication, 19 Jan 2015). The high consumption of alcohol is also a growing problem.

As has been shown, the modernist planning of the houses, the rejection of the past and the local dynamics have led to the emergence of, on the one hand, uncanny dead and empty spaces and, on the other, disciplining practices. Faced with this new urban reality, the responses of the inhabitants waver between resistance, boredom and dependency on the oil company (and, with it, the State), a situation that raises doubts and opens questions about the meaning of Buen Vivir, in the eyes of the State, and the role of the inhabitants in the future Amazonia.

Conclusions

As was mentioned at the beginning of this article, to conceive of a space as a produced space (Lefebvre Citation1974) implies to critically analyse the production of categories in which this space is read and decoded in specific periods of time. Having described the architecture and aesthetics of the Millennium Community Playas de Cuyabeno, and the dynamic interaction between spatial planning and the residents’ ways of living there, what I have called a space and architecture of extractivism can be summarized as follows.

The space and architecture of extractivism are based on a mode of production and model of development known as new extractivism. As was mentioned at the beginning of the analysis, in this model, unlike traditional extractivism, the exploitation of resources is accompanied by a stronger presence of the State. Among other characteristics, this stronger presence of the State comes along with a new conception of the exploitation of resources, which is now perceived as necessary to combat poverty and promote development, keeping intact the ‘myth of progress’ (Gudynas Citation2009, p. 221). Constructions such as the MC’s are created with revenues from the exploitation of natural resources and are justified to public opinion as a step towards the social and economic progress of the Ecuadorian nation. The constructions are embedded in a discourse that heralds the extraction of natural resources as the main source of wealth and modernization. As the case of the MCs shows, the State is even willing to resort to violence (through military intervention) to achieve its purposes. Thus, one of the main characteristics of the space and architecture of extractivism is that the spatial changes are violently imposed rather than in dialogue with the communities concerned.

Another characteristic of the space and architecture of extractivism in Ecuador is that it is the product of a discursive tension between the new extractivist model of development and the discourse of Sumak Kawsay and the Rights of Nature. While the government emphasizes the idea of respecting social and cultural differences, it simultaneously homogenizes Ecuadorian society by constructing uniform infrastructures and buildings. Thus, the MCs are far from being a representation of Ecuadorian pluriculturalism or of a harmonious relation with Amazonian flora and fauna. Instead, they reproduce a modernist narrative that perpetuates ideals of modernity, progress and national development. This modernist narrative is accompanied by a colonial narrative which is reflected in the use of violence (at the beginning of the extractivist project leading to the construction of the MCs), the establishment of rules to control and urbanize the community, the community’s economic dependence on the oil company and the political discourse that reproduces the rhetoric of salvation, civilizing mission and progress in service of its own understanding of Sumak Kawsay/Buen Vivir.

The produced space in the Amazonia region, therefore, is the reflection of a political struggle or, better, the result of contradictory political intentions in which the Foucaultian triad of space–knowledge–power is clearly visible: it is based on the construction of a political discourse proclaiming the benefits of oil extraction, resulting in the construction of a planned community within which the State tries to promote order and homogenization through a disciplining that is not just spatial, but also affects the inhabitants’ bodies and minds. The MC’s were constructed in a space treated as a tabula rasa, with no room for traces or residues of former dwellings, or for memories and traditional practices. The result of the disconnect between new extractivism, Sumak Kawsay and the Rights of Nature is a corresponding disconnect between the standardized, sterile way in which the MC’s are constructed architecturally, their natural surroundings and the traditional livelihoods and practices of the inhabitants.

The third aspect of the space and architecture of extractivism is the seeming discord between the time of the authorities’ interests, the time of the physical structures and the time of the inhabitants, each of which seems to follow a different temporality. The first, privileging speed, are continuously running against time (needing to construct the MC as quick as possible, needing to sell oil barrels); the structures, which were rapidly constructed, are experiencing accelerating degradation; and, finally, the residents are wavering between the expansion of leisure time and boredom.

The possible effects of the space and architecture of extractivism on culture and identity are vast and harmful. Since space, culture and identity are inseparable terms, it is important to ask what kind of identities and cultural practices are promoted and pre-empted by these projects? As I have tried to show, the extractive space and architecture are transforming elements of the Kichwa ways of life. In turn, the inhabitants are adapting to the space while also manifesting some anti-disciplinary actions. Nonetheless, it is not possible to say if these actions are really escaping the authorities’ narrative of modernity/progress and their intention of disciplining the space and the subjects living in it. To gain a fuller picture than can be given here, it would be important to analyse in depth the possible implications of these space transformations for the construction and formation of an extractive cultural identity. What can be said on the basis of the present analysis, however, is that urban projects with the characteristics described above devalue the everyday activities and historical practices of inhabitants of the Amazon territory, irrespective of whether they are indigenous people or mestizos settlers; as a result, the communities in the Amazonian Region are being moulded, by means of the rearrangement of the spaces they live in, into the shape of a national identity/way of being constructed on the basis of the interests of the government and the oil companies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributor

Alejandra Espinosa Andrade studied social psychology in the Diego Portales University (Chile) and obtained a Master Degree in Political Science in the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO Ecuador). She has worked as a researcher and lecturer of topics related with human rights, participative methodologies, social movements, project management and territorial planning in national and international organizations (UNICEF, UNHCR, FLACSO Ecuador). Currently she is working in her Ph.D. at the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (ASCA). In her research she analyses, from a critical and multidisciplinary perspective, governmental urban projects and its relation with Ecuadorian cultural identity. Her Ph.D. Research is financed by the Secretariat of Higher Education, Science, Technology and Innovation of Ecuador.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Name given in the region to people that have lived there for decades but come from other provinces of Ecuador.

2. The Kichwa Sarayaku-case presented to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights exemplifies the antagonistic relation between some of the communities and the government and oil companies (see Inter-American Court of Human Rights, Citation2012).

3. See, for example, the Chevron case and reports published by organizations such as Observatorio de derechos colectivos del Ecuador CDES (http://www.observatorio.cdes.org.ec/), Oil Watch (http://www.oilwatch.org/), the Fundación Regional de Asesoría en Derechos Humanos – INREDH (www.inredh.org), Acción Ecológica (www.accionecologica.org), and the United Nations Human Rights Council, among others. Significantly, the Ecuadorian State has also targeted some indigenous groups and environmental organizations opposed to its mining, oil and water policies by accusing them of terrorism. See, for example, the cases of Carlos Pérez Guartambel and Javier Ramírez, who were accused by the Ecuadorian government of being terrorists in 2010 and 2014, respectively, when participating in activities against water policies and mining exploitation (Articles El Comercio, 10 June 2014 and El Mercurio, 22 January 2013).

4. For more information about the Yasuni ITT initiative see: Ministry of Environment (Citation2010).

5. For more information about the critics against the closure of this initiative see the information collected by the group Yasunidos, a group of the civil society created to protect the Yasuní forest and the governmental initiative. http://sitio.yasunidos.org/es/yasunidos/crononologia-de-hechos.html

6. Each house comprises 96.04 sqm and has three rooms: a kitchen, a living room and a bathroom. The latter is situated in the empty space below the main floor. The houses, including basic furniture and household appliances, were given for free to the inhabitants of the communities (Araujo Citation2013).

References

- Acosta, A. , 2013. Extractivism and neoextractivism: two sides of the same curse. In: M. Lang and D. Mokrani , eds. Beyond development: alternative visions from Latin America , 61–86. Available from: http://www.tni.org/sites/www.tni.org/files/download/beyonddevelopment_extractivism.pdf [Accessed 20 June 2014].

- Andes , 2013. La comunidad del milenio Playas del Cuyabeno abre una nueva relación del Ecuador con el uso de sus recursos no renovables [The Millennium Community Playas de Cuyabeno opens a new relation between Ecuador and the use of non-renewable natural resources]. Andes, 4 Oct. Available from: http://www.andes.info.ec/es/actualidad/comunidad-milenio-playas-cuyabeno-abre-nueva-relacion-ecuador-uso-sus-recursos-no [Accessed 10 May 2014].

- Araujo, A. , 2013. Una ciudadela moderna en el Cuyabeno [A modern citadel in Cuyabeno]. El Comercio, 2 Oct. Available from: http://www.elcomercio.com/negocios/ciudadela-Cuyabeno-Correa-vivienda-escuela_0_1003699703.html [Accessed 17 June 2014].

- Ayala, S. , 2014. Mandatario reitera críticas al ecologismo radical que dificulta el desarrollo [President criticizes radical ecologism that makes difficult the development of the country]. El Ciudadano, 18 Jan. Available from: http://www.elciudadano.gob.ec/mandatario-reitera-criticas-al-ecologismo-radical-que-dificulta-el-desarrollo/ [Accessed 30 June 2014].

- Bustamante, T. and Jarrín, M.C. , 2005. Impactos sociales de la actividad petrolera en Ecuador: un análisis de los indicadores’ [ Social impacts of oil activity in Ecuador: analysis of indicators]. Iconos, revista de ciencias sociales , 21, 19–34.

- Calapucha, C. , 2012. Los modelos de desarrollo: Su repercusión en las prácticas culturales de construcción y del manejo del espacio en la cultura Kichwa Amazónica [ Models of development: their impact in cultural practices related with management and construction of space in Kichwa-Amazonian culture]. Cuenca : Universidad de Cuenca, DINEB and UNICEF. Available from: http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/5286 [Accessed 10 March 2015].

- Correa, R. , 2012. Enlace ciudadano 271, 12 de Mayo 2012 [Citizens outreach 271, May 12, 2012] [video online]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lmIipIrc9mM [Accessed 20 April 2014].

- Correa, R. , 2013. Comunidad del milenio Playas de Cuyabeno- Discurso Inaugural [Millennium Community Playas de Cuyabeno inaugural speech]. Presidencia de la República del Ecuador, 1 Oct. Available from: http://www.presidencia.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2013/10/2013-10-01-ComunidadMilenioCuyabeno.pdf [Accessed 21 April 2014].

- De Certeau, M. , 1984. The practice of everyday life . Berkeley : University of California Press.

- Ecuador, Constitution , 2008. Quito : Presidency of the Republic Office.

- El Telégrafo , 2013. Comuneros acceden gratuitamente a viviendas [People from communities have access to free houses]. El Telégrafo, 2 Oct. Available from: http://www.eltelegrafo.com.ec/noticias/politica/2/comuneros-acceden-gratuitamente-a-viviendas [Accessed 28 June 2014].

- El Telégrafo , 2014. Pañacocha se abre al futuro [Pañacocha is open to the future]. El Telégrafo, 17 Jan. Available from: http://www.eltelegrafo.com.ec/noticias/politica/2/panacocha-se-abre-al-futuro [Accessed 15 June 2014].

- El Universo , 2008. Disputa de indígenas y militares [Dispute between indigenous people and militaries]. El Universo, 12 Oct. Available from: http://www.eluniverso.com/2008/10/12/0001/9/2AC41FEC0F304043A51A78217C3E0017.html [Accessed 12 March 2015].

- Gudynas, E. , 2009. Diez tesis urgentes sobre el nuevo extractivismo [Ten urgent theses about new extractivism]. In: CAAP (Centro Andino de Acción Popular) and CLAES (Centro Latinoamericano de Ecología Social), eds. Extractivismo, política y sociedad. Quito. Available from: http://www.ambiental.net/publicaciones/GudynasNuevoExtractivismo10Tesis09×2.pdf [Accessed 20 June 2014].

- Gudynas, E. , 2013. Extracciones, extractivismos y extrahecciones: un marco conceptual sobre la apropiación de recursos naturales [Extractions, extractivism and extrahecciones: a conceptual framework about the appropriation of natural resources]. In: Centro Latino Americano de Ecologia Social CLAES, Observatorio del Desarrollo, N° 18. Available from: http://www.extractivismo.com/documentos/GudynasApropiacionExtractivismoExtraheccionesOdeD2013.pdf [Accessed July 15 2014].

- Highmore, B. , 2002. Everyday life and cultural theory, an introduction . London : Routledge.

- Inter-American Court of Human Rights , 2012. Case of the Kichwa indigenous people of Sarayaku v. Ecuador Judgment of June 27, Merits and Reparations. Available from: http://corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_245_ing.pdf [Accessed September 15 2014].

- La Hora , 2010. Ecuador Ama la Vida es el nuevo lema turístico de la nación andina [Ecuador loves life is the new touristic slogan of the Andean nation]. La Hora, 16 Oct. Available from: http://www.lahora.com.ec/index.php/noticias/show/1101034318/-1/'Ecuador_ama_la_vida’,_es_el_nuevo_lema_tur%C3%ADstico_de_la_naci%C3%B3n_andina.html [Accessed 9 November 2014].

- Le Corbusier , 1987. The city of tomorrow and its planning . Translated from the 8th French Edition of URBANISME (1929). New York : Dover Publications.

- Lefebvre, H. , 1974. The production of space . Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith in 1991 from the original version (1974). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

- Lindner, C. , 2009. London undead: screening/branding the empty city. In: S. Hemelryk , E. Kofman , and C. Kevin , eds. Branding cities: cosmopolitanism, parochialism, and social change . Chapter Seven. London : Routledge, 91–104.

- Mignolo, W. , 2007. Coloniality: the darker side of modernity. Cultural Studies , 21 (2–3), 155–167. doi: 10.1080/09502380601162498

- Ministry of Environment , 2010. Yasuni-ITT initiative: a big idea from a small country. Available from: http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/Yasuni_ITT_Initiative1009.pdf. [Accessed August 2014].

- Petroamazonas , 2009. Revista Corporativa Trimestral. [Corporate Magazine] [Online]. April, Year 1 N°2. Available from: http://issuu.com/petroamazonasep/docs/revistapamabril09 [Accessed 12 May 2015].

- Pratt, M.L ., 2002. Modernity and periphery: toward a global and relational analysis. In: E. Mudimbe-Boy , ed. Beyond dichotomies: histories, identities, cultures, and the challenge of globalization . Albany : State University of New York Press, 21–49.

- Soja, E. , 2006. Foreword cityscapes as cityspaces. In: C.H. Lindner , ed. Urban space and cityscapes . New York : Ed. Routledge, xv–xviii.

- Vidler, A. , 1992. The architectural uncanny . Cambridge, MA : The MIT Press.