ABSTRACT

How might scholars of public memory approach the protean relationship among imperial legacies, nationalized collective memories and urban space from an ‘off-center’ perspective? In this essay, I pursue this question in relation to a monument whose political biography traverses, and troubles, the distinction between imperial and national times, sentiments, and polities. The statue in question is that of Ban Josip Jelačić, a nineteenth Century figure who was both a loyal servant of the Habsburg Empire and a personification of nascent Croatian and South Slavic national aspirations. Jelačić's monument was erected in Zagreb's central square in 1866, only seven years following his death; in the heady political context of the Dual Monarchy, his apotheosis as a figure of regional rebellion caused consternation on the part of the Hungarian authorities. Nor did the statue's controversy end with the Habsburgs. Following World War II, Jelačić's embodiment of Croat national pride proved anathema to Yugoslav socialist federalism, and the monument was dismantled in 1947, only to be re-erected following the disintegration of Yugoslavia and Croatian independence in 1991. Accordingly, the statue of Jelačić is a privileged material medium of and for nationalist memory in Croatia, even as it also conjures ghosts of the city's and state's imperial and socialist pasts. I theorize this play of hegemonic and repressed collective memories through the concepts of public affect and mana, especially in relation to several recent public events that centred on the statue: the memorial to Bosnian-Croat general Slobodan Praljak, who committed suicide during proceedings of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in November 2017, and the celebration of Croatia's achievements in the 2018 World Cup.

Introduction: halftime

Acrid smoke fills the air, lingering above the sweat-drenched heads of the crowd, static in the absence of even a mild breeze. Occasional bursts of crimson flame erupt with a crack, endowing the haze with a vague luminescence. A chorus of mingled voices, at once anxious, jubilant, and reproachful, ebbs and flows, mingles with the fumes. An already humid day becomes oppressively airless and clammy in the midst of the square. Above it all, a stern visage gazes ahead impassively. Whether the bodies below are assembled in revolution or bacchanal is a matter of indifference to this bronze-faced observer; he has witnessed both before.

The date is 15 July 2018. I am watching a live broadcast of the World Cup final between Croatia and France on a massive screen in Zagreb's central square. Halftime. A jet of beer spray refracts the light of an ignited flare; the volume of the din increases apace. Anticipation, hope, and anxiety comingle – although Croatian wing Ivan Perišić netted a brilliant equalizer in the match's 28th minute, France answered quickly on a penalty shot following a disputed hand ball call and leads 2–1 at the break. Regardless of the eventual outcome, I sense that the soiree in the square has only begun. As if to confirm my suspicion, a young man draped in a Croatian flag ascends the pedestal of the statue to my left, leading nearby revellers in an impromptu chant of the de facto anthem of the summer, ‘Igraj moja Hrvatska (Play, my Croatia): Srce mi gori! (My heart is burning!)’Footnote1 While it is difficult to imagine the ‘heart’ of the statue above igniting, the figure on horseback is nonetheless a key component of the crowd: In festive solidarity, he sports a gigantic cape embroidered with the šahovnica, the red-and-white checkerboard pattern that adorns Croatia's coat-of-arms. I cannot avoid wondering what BanFootnote2 Josip Jelačić von Bužim, the nineteenth Century military figure commemorated by both the statue and the square, might have made of this display ().

In this essay, I pursue a partial, selective genealogy of the monument to Ban Josip Jelačić that stands at the centre of his eponymous square in Zagreb, and thus occupies a focal, centripetal position for Croatia as whole. Contrary to Robert Musil's bon mot concerning the invisibility of monuments, I narrate moments in which the statue of the Ban becomes exceptionally visible, and thereby articulates collective visions of the past and present of the city, nation, and region. My aspiration is not only to account for the blatant centrality of the statue and Jelačić to Croatian national identity today, but, equally, to unsettle the monument's monolithic, monologic character by burnishing the latent imperial legacies that it embodies. In doing so, I heed our volume's call to off-center empire: ‘to examine empire in its interstitial complexity, not as a coherent whole corresponding to its own hegemonic discourse, but as a complex ensemble of contradictions, contestations, and transformations both past and present’ (Editors’ Introduction). Against essentialized images of both ‘empire’ and ‘nation,’ I foreground an interpretation of the statue's materiality and the Ban himself that defies and unravels the rigid dichotomy between imperialism and nationalism.

My argument stands at the intersection of several distinct literatures, each of which provides scaffolding for my exposition. First, I extend recent analyses and critiques of public sculpture, statuary and monuments. In the age of ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ and the toppling of marble Confederates in the American south (Rao Citation2016), the political lives of (some) statues have become dramatically public and publicly dramatic. In cities such as Moscow (Grant Citation2001), Skopje (Graan Citation2013), Trieste (Hametz and Klabjan Citation2018) and Vienna (Jovanović Citation2019), anthropologists and historians have demonstrated how monumental statues, old and new alike, serve contemporary political ends. Nor is it a coincidence that the politics of monuments is especially sharp in post-imperial cities – a point that I return to frequently below.

Critical scholarship on the perdurance of imperial legacies – what Ann Laura Stoler (Citation2016) has aptly called ‘imperial duress’ – constitutes a second inspiration for my interpretation of the Ban and his statue. In tandem with Stoler's insistence on the enduring effects of imperial knowledge/power, an array of thinkers has interrogated the present modalities of a variety of past empires, including the British (Mishra Citation2012), French (Daughton Citation2006), Habsburg (Judson Citation2016, Walton Citation2019a), Russian (Kivelson and Suny Citation2017) and Ottoman (Walton Citation2010, Citation2016, Citation2019a, Danforth Citation2016, Argenti Citation2017). Faulkner’s (Citation2011) chestnut – 'The past is never dead. It's not even past’ (p. 73) – is especially resonant in post-imperial contexts. With this in mind, I accentuate the (post)imperial logics and entailments that subtend Jelačić's monument's overt status as a national symbol. In other words, I seek to ventriloquize the ‘silenced’ imperial pasts (Trouillot Citation1995) of the Ban and his statue.

In order to burnish the statue's and the Ban's latent genealogies, I draw from recent theories of public affect in urban space (Crang and Thrift Citation2000, Thrift Citation2004, Mazzarella Citation2009, Carabelli Citation2019). More specifically, I theorize monuments as conduits for public affect, which, in Kathleen Stewart’s (Citation2007, p. 87) memorable phrase, is ‘at once abstract and concrete … both a distant, untouchable order of things and a claustrophobically close presence.’ Following William Mazzarella (Citation2017), I attend to what we might call the Ban's mana: ‘the substance … (that) infuses and radiates from the people and objects that have the capacity to mark the boundaries of worlds and, above all, to be efficacious within and between those worlds’ (19). That Jelačić and his statue are mana-full within the urban landscape of Zagreb and Croatia as a whole is beyond doubt. My task is to account for this this mana-fullness in relation to the imperial biographies and legacies of both the Ban and his statue.

In pursuit of the Ban's mana, I approach his monument as a site of memory in Pierre Nora’s (Citation1989) sense, but from a conceptually and methodologically distinct position. Beyond registering disparities between history and collective memory, I foreground the temporally-mediated forms of public affect – mana – that the Ban's statue harnesses and wields. As I argue, these modes of affect both perpetuate and mute imperial genealogies of knowledge and power, even as they also trouble the very distinction between imperial and national. Grasping the mana of the Ban therefore entails sensitivity to the multiplicity of times embodied by public objects, informed above all by Walter Benjamin’s (Citation1968, 1999) trenchant critique of historicism. Elsewhere (Walton Citation2019b) I have termed this approach ‘textured historicity,’ with an eye to ‘the distinctive, embodied encounter between the subject in the present and the objects that convey the past in the present’ (p. 5). As we will see, the monument to Ban Jelačić is the epicentre of many such encounters. My double aim is to render the temporal textures of these encounters while also troubling the hegemonic, largely national(ist) modes of public memory that they presuppose and re-inscribe.

Origins: on the imperial roots of a national icon

Ban Jelačić never had the opportunity to see the monument that honours him in central Zagreb – he was buried in the garden of his villa in the suburb of ZaprešićFootnote3 in 1859, seven years before his statue was raised in the square that already bore his name. At first blush, Jelačić is not so obvious a candidate for enshrinement as the embodiment of a nation and a state as an Atatürk, a Ho Chi Minh, a Bolívar, or a Washington – unlike this quartet, and many others, he was a counterrevolutionary rather than an insurgent. Jelačić earned his fame and, for some, infamy by commanding the Habsburg imperial forces sent to suppress the percolating revolution in Hungary in 1848–1849 (Judson Citation2016, p. 215, Newman and Scheer Citation2018, p. 152).

The future Ban was born to a family of military gentry in Petrovaradin, a fortress town on the Military Frontier (Vojna Krajina, Militärgrenze) between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, which is today incorporated as a district of the Serbian city Novi Sad. Borderlands, their contestations, and the political possibilities that accrued to them were to play a role throughout his life. In the early decades of his adulthood, Jelačić rose through the ranks of the Habsburg military – like his father and grandfather before him – while also drawing close to the emergent Illyrian Movement (Ilirski Pokret), which aspired to the political and cultural unification of the South Slavs under the canopy of the Empire (Tanner Citation1997, Hrvatski Povijesni Muzej Citation2009, p. 23). These two commitments, imperial and proto-national, did not seem to create contradictions for him (see Judson Citation2016). For Jelačić, it was precisely through the structuring, mediating force of the Empire that Croats and South Slavs might reach Herderian fullness as a nation and people.Footnote4

The revolutionary year of 1848–1849 was the key pivot in Jelačić's life. In response to the liberal-revolutionary uprisings stirring across the Empire (and Europe generally), the Habsburg army was mobilized to quell dissent, particularly in Hungary. Jelačić was appointed Ban of the Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia and DalmatiaFootnote5 early in 1848; shortly thereafter, he also became the imperial commander on the Military Frontier. With Vienna's consent, he led an army of some 40,000 into Hungarian territories in September 1848, a manoeuvre in defence of both Croatian prerogatives and Habsburg hegemony (Hrvatski Povijesni Muzej Citation2009, pp. 43–45). Following a convoluted autumn of incursions, counter-thrusts, and partial truces, Jelačić's battalions, a hodgepodge of other Habsburg units, and a large, supplementary force sent from Russia by Tsar Nicholas I stifled the Hungarian rebellion, a counterrevolutionary victory ultimately more beneficial to Vienna than Zagreb. Nonetheless, Jelačić became a hero for Croats and other South Slavs (Newman and Scheer, p. 157), especially among the peasantry, who revered him more as the abolisher of serfdom – a reform he enacted in April 1848 – than as a paladin. Jelačić returned to Zagreb, where he spent the final decade of his life in relative quietude. While he remained Ban, he was effectively stripped of authority following the suppression of the revolution and the installation of the absolutist regime of Alexander von Bach (for whom he was a willing agent) in Vienna. Jelačić's funeral, in May 1859, was lavish and well-attended. His catafalque passed through the square already named for him, which would soon house his likeness as well.

It is at this point in our exposition that man becomes myth, and metal. Seven years following his death, the Ban rose again as an equestrian statue designed by the neo-Baroque sculptor Anton Dominik Fernkorn (1813–1878). Fernkorn's commission for the monument underscored the political and aesthetic realm that the Ban's memory was intended inhabit – the sculptor's most famous works are the statues of Archduke Charles and Prinz Eugen of Savoy, two of the Habsburg Empire's most feted military heroes, both of which stand in Vienna's Heldenplatz, in the shadow of the Hofburg Palace. As I have attempted to convey with brevity, the Ban's life was one of laminated loyalties. He was both an imperial deputy and an advocate of Croatian and south Slav ambitions, though not in a contemporary sense – he did not envision an independent Croat or Slav nation-state. To a significant degree, military strategy outweighed political ideology for the Ban. The same cannot be said of his monument, however, as we will see.

Controversies: concealment, dismantlement, return

Throughout Zagreb's modernization, Ban Jelačić Square—the city's central public space—was a barometer of political change. In the unstable political environment of Zagreb, the issue of representation was highly problematic. Whose history and what legacy should be represented and celebrated in the city? (Eve Bau and Ivan Rupnik, Citation2007, p. 46)

Controversy was coeval with the erection of the statue in 1866: Jelačić was a despised figure for many of the Empire's Hungarians, and the sculpture's northerly orientation on the square was interpreted as an act of resistance against Hungarian suzerainty (Blau and Rupnik Citation2007, p. 46).Footnote6 Despite the monument's insurrectionary stance, it stood firm throughout the final decades of the Empire, and persisted during the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (1918–1929), the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1929–1940), and the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska/NDH, 1941–1945), the Nazi puppet-state of the fascist Ustaša Movement.Footnote7 Jelačić was not so fortunate following World War II, however – soon after the arrival of Tito's partisans in Zagreb, the monument was concealed before being dismantled entirely in 1947 (Ibid., p. 53).Footnote8

The brief period between the end of World War II and the removal of the statue was a transformative time in the biography of the monument. Several ephemeral constructions encased Jelačić during these years, including a wooden statue of a Partizan and Partizanka (see ), a papier-mâché obelisk crowned by the five-pointed communist star, and a sculpture of a giant anvil to celebrate 1 May (International Workers’ Day) (Mataušić Citation2001, p. 129). Although the statue of Jelačić already embodied a certain ‘rebellious’ character as a focal point for the turbulent relationship between the Kingdom of Croatia and Hungary, it was the socialist treatment of the monument that endowed it with a powerful national character. In a classically Freudian fashion, the repression – and suppression – of the Ban's statue enhanced its potency and meaning. The act of masking the monument in socialist iconography ironically directed attention to that which had been concealed, and thereby charged the statue and the Ban as powerful, potentially dangerous sites of memory whose mana could eventually be harnessed to nationalist ends. It is unlikely that this ‘magnetization’ of the monument (Mazzarella Citation2013, p. 39) would have been as potent had Tito's partisans simply removed it upon their arrival in Zagreb in 1945.

Figure 2. A replica of the statue of a Partizanka that encased and concealed the monument to Jelačić in 1945–1947, part of the collection of the Zagreb City Museum (photograph by author).

Jelačić and his steed were dismantled in July 1947, but they were not consigned to the rubbish heap. Thanks to the foresight of several of Zagreb art historians who recognized the importance of the statue to Anton Dominik Fernkorn's oeuvre, the dismembered Ban was boxed up in the basement of the Glyptotheque of Yugoslav Academy of Arts and Sciences. Jelačić remained in darkness for the next four decades, but he was not forgotten. In 1990, the first Parliamentary elections in the Socialist Republic of Croatia were held. They resulted in an overwhelming victory for Franjo Tuđman and his nationalist Croatian Democratic Union (Hrvatska Demokratska Zajednica, HDZ), and marked one of the key episodes leading up to the disintegration of Yugoslavia. Shortly thereafter, preparations for the restoration and re-erection of the statue of Jelačić began (Milčec Citation1990). On the afternoon of 16 October 1990 – Jelačić's 189th birthday – an enthusiastic crowd gathered in Republic Square (soon to be renamed after Jelačić again) to witness the Ban's return.Footnote9

The re-erection of Jelačić's statue was clearly understood as a national, Croatian resurrection. Povratak Bana (The Return of the Ban) (1990), a decorative book by Zagreb author Zvonimir Milčec that was published in conjunction with monument's re-establishment, features the provocative subtitle, ‘A monument to Croatian pride and Croatian shame’ (Spomenik hrvatskog ponosa i hrvatskog srama). Notably Milčec's main title also elides the distinction between Jelačić and his statue – an elision that has since achieved the status of tacit, vernacular truth.Footnote10 With the re-erection of the monument 1990, Jelačić himself, his statue, and the square generally achieved consolidation as exclusively national, Croatian sites of memory, as the discourses and practices that orbit around the monument today powerfully attest.

Conjugations: military men and miniatures

In early December 2017, I was hurrying through Ban Jelačić Square on my way to an appointment when a crowd at the base of the monument caught my eye. I paused, then approached. Gazing past the assembled onlookers, I absorbed the scene: Hundreds of candles in red plastic casing huddled at the base of the statue, just beneath a black-and-white image of a bearded man in uniform emblazoned with the simple slogan, ‘Hero!’ (Junak) (). The poster had been taped to the base of Jelačić's statue; it also included a message: ‘Thank you, General! Croatia will never forget you … ’ (Generale Hvala! Hrvatska vam zaboraviti neće … ). Two Croatian flags, a silken honour guard, hung on either side of the poster, completing the tableau. Other passers-by paused in curiosity, and, in some cases, offered mournful salutes or prayers.

Figure 3. Ban Jelačić hosts a spontaneous memorial to Slobodan Praljak, December 2017 (photograph by author).

On 29 November 2017, Slobodan Praljak, a Bosnian-Croat general and convicted war criminal, appeared in court in The Hague to receive judgment on his appeal to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). After hearing that his conviction for war crimes during the war in Bosnia in the 1990s had been upheld, Praljak expostulated: ‘General Praljak is not a war criminal, and I reject your judgment with contempt’ (General Praljak nije ratni zločinac i s prijezirom odbacujem vašu presudu) (Vijesti Citation2017). He then imbibed a vial of poison and died shortly thereafter. Praljak's spectacular suicide immediately dominated headlines in Croatia, the Balkans, and around the globe; soon, candles and tributes began to appear at the base of the statue of Jelačić in Zagreb.

It would be wrong to suggest that Praljak's morbid insurrectionary gesture was welcomed as a defence of ‘national’ pride by all Croats – indeed, most of my left-wing friends in Zagreb responded with disdain and disgust. Nonetheless, it is striking that his suicide was interpreted by many as an act of national resistance and retaliation that warranted commemoration at the feet of the Ban. Any simple historical comparison between the political and military activities of Ban Jelačić in the mid-nineteenth Century Habsburg Empire and the actions of Praljak and the Croatian Defence Council (Hrvatsko vijeće obrane, HVO) in Bosnia–Herzegovina in the 1990s would be transparently absurd. Yet Parljak was immediately assimilated to the Ban's memory. Praljak's image was literally laminated onto Jelačić's; the looming figure of the Ban sanctioned and ratified the general's induction into nationalist collective memory. Here, we visibly witness the contagious power of the Ban's mana – the statue is not merely a ‘symbol’ of Croatian history, but a mechanism for (re)producing national(ist) memory. Immediately after his death, Praljak was invigorated by the mana of the monument.

This has happened before. In 2005, Jelačić's statue briefly found itself at the centre of an escalating political dispute between Croatia and the European Union, focused on Ante Gotovina, another notorious figure from the wars of the 1990s.Footnote11 When membership negotiations with the EU stalled due to Gotovina's truancy from the ICTY, protesters amassed in the square and draped the monument to the Ban with photographs of the general (Pavlaković Citation2010, p. 1723).Footnote12 The cases of Praljak and Gotovina both powerfully illustrate the role of Ban Jelačić's statue as a focus of and conduit for nationalist sentiment in Croatia today. In Lefebvre’s (Citation1991) terms, the spatial practices that surround the monument produce and reiterate a representation of the space of the square as a distinctively national site of memory. At critical moments, the mana of the Ban suffuses the square, lending itself to protest and exuberance alike. Jelačić solemnizes the persecutions and deaths of ‘national’ martyrs, but also joins in nation-wide euphoria, as he did on the evening of the World Cup Final in 2018. And given its potency, it is no surprise that the mana of the monument also migrates in curious ways.

***

The souvenir reduces the public, the monumental, and the three-dimensional into the miniature, that which can be enveloped by the body, or into the two-dimensional representation, that which can be appropriated within the privatized view of the individualized subject. (Stewart Citation1993, pp. 137–138)

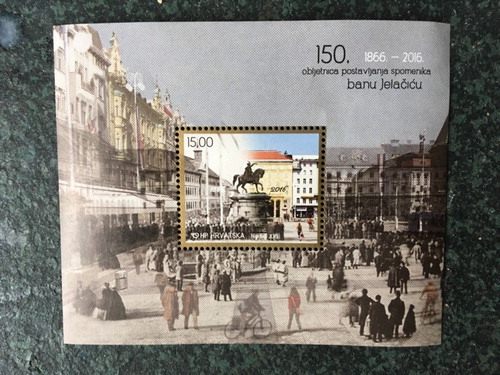

As Susan Stewart (ibid.) has memorably argued, souvenirs and other miniatures transform the semiotic properties of public monuments by rendering them suitable to ‘privatized’ consumption. In this light, it is telling that Jelačić's statue has been the object of frequent miniaturization in Zagreb and Croatia. Miniatures, unlike monuments, are markedly mobile, in ways that are always mediated by social and political logics. The magnets sold in Zagreb's airport leave the city and country with their new owners, conveying the Ban's mana to unanticipated destinations where it becomes dispersed and denatured, no longer reinforced by spatial and political practices that centre on the monument itself. By contrast, another miniature, a stamp that was issued in 2016 by the Croatian Post to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the statue's erection (), potentially shuttles through both national and international space. Graced by the imprimatur of the state, the stamp is not a souvenir, but a placeholder for the monument that bolsters the Ban's mana by integrating it into a broader domain of nationally-ratified signs.Footnote13

Figure 4. A photograph of the stamp commemorating the 150th anniversary of the erection of Ban Jelačic's statue (photograph by author).

The stamp is more than an iteration of the Ban's mana, however – it also collapses the distinction between past and present through the lamination of two distinct photographs. While this layering is difficult to perceive at a first glance, a closer inspection of the stamp and the illustrated ‘frame’ that surrounds its perforated edge reveals the visual trick. A black-and-white photograph depicts a crowd surrounding the monument in the late nineteenth or early twentieth Century; a second colour photograph shows a contemporary scene. The fulcrum between the two laminated images is the statue of the Ban itself.Footnote14 In this subtle manner, the stamp asserts an unbroken, homogeneous image of the nation, oriented toward and united by the monument in both past and present. Conveniently, the forty-odd years of the Ban's absence are glossed over entirely, while the imperial genealogy of Jelačić, the square and the city are seamlessly woven into the fabric of a national narrative.

As I fine-tuned an initial draft of this essay, further miniatures of the monument pursued me. In May 2019, a joint initiative on the part of Zagreb's museums to bring art into non-institutional public space constructed a temporary pavilion on the central square. Among the highlights of this exhibition was a collection of Jelačić memorabilia from the Croatian History Museum, including a scale model of the square as it appeared in the late nineteenth Century. Visitors to the pavilion could experience the vertiginous sensation of gazing down at a miniature version of the very statue that loomed beside them, only a few meters away.Footnote15 Even more startlingly, another miniature of the monument saluted me on a recent morning as I dropped my son Benjamin off at his Kindergarten in our Zagreb neighbourhood. To commemorate the City of Zagreb Day, his group had constructed a diorama of Ban Jelačić Square, complete with a paper-and-marker version of Jelačić and his horse at its centre (see ). Through miniaturization, the monument to the Ban and its mana not only circulate through national space, they also make an entry into the earliest years of Croatia's youngest residents, already hailed as the next generation of guards and stewards for nationalized collective memory.

Conclusion: France 4, Croatia 2, or, nation and empire off-centred

Croatia was ultimately outmatched by France in Moscow, but, as I anticipated, the festivities in the square had only begun. Collective effervescence bubbled and burst forth throughout the night and continued unabated when the team returned to Zagreb the following day. The team's open-top party bus required several hours to deliver them from the airport to Ban Jelačić Square – the entirety of the 18 kilometre route was clogged with fans and well-wishers. Once there, the Vatreni – the familiar name for the national team – took the stage just opposite the monument to the Ban to celebrate, and be celebrated, for hours to come.Footnote16

How to interpret this extraordinary mass celebration of defeat? Perhaps the public affect that coursed through the square and the crowd, complemented and supplemented by the Ban's mana, was simply too potent to dissipate, regardless of the match's outcome. Or perhaps the loss resonated with a longer genealogy of martyrdom and defeat that has become integral to certain national myths in Croatia.Footnote17

As I stared up at the bronze Ban outfitted in the iconic red-and-white cape, however, different thoughts came to mind. To celebrate in defeat is, in a sense, to salute incompletion, to acknowledge the failure of ambition to achieve its object and, therefore, to accommodate a lack of closure, to reconcile oneself to alterity as a condition of identity. Although the Ban's mana is a wellspring of nationalist affect and identity in Croatia today, it is not difficult to open lines of flight away from the foreclosures of nationalism in both Jelačić's biography and the statue itself. For instance: A pervasive rumour in Zagreb insists that a bottle of brandy (rakija) is hidden in the belly of Jelačić's bronze steed, suggesting that the smooth, adamantine surfaces of public commemoration always contain more intoxicating, destabilizing possibilities. And about that horse: It was given to Jelačić by an admiring Ottoman grandee from Bihać, a city in north-western Bosnia near the Jelačić family's ancestral homeland of Bužim. Its name was Emir. What more might we learn from the fact that the preeminent national monument in Croatia was created by a German sculptor and features a Turkish horse?

Such questions clearly ‘off-center’ nationalist narratives and premises, both methodological and otherwise, by highlighting the porousness, contradictions and contingencies of nationalist enclosures of history and territory. They equally off-center hegemonic visions of imperial pasts. Whether in relation to the Habsburgs (e.g. Judson Citation2016) or other imperia (e.g. Barkey Citation2008), recent histories of empire tend to remain locked in an oscillating, binary circuit of criticism and nostalgic ovation. With its labile, mobile mana, Zagreb's monument to Ban Jelačić defies this dichotomy, precisely because its vigour is irreducible to the instrumental designs of either empire or nation-state. By seizing the ‘textured historicity’ (Walton Citation2019b) of the statue as it has taken shape over the past century-and-a-half, I have gestured to an architectonic feature of collective memory of the Ban that, I hope, will resonate across a plethora of (post)imperial contexts: Imperial pasts and national presents are neither contradictory nor fully continuous. Rather, both pasts and presents are ‘constellations’ (Benjamin Citation1968, 263) of the imperial and the national – like the Ban's mana itself. When viewed from off-centre, these constellations, and the powers radiate from them, appear in the flash of startling new analytical and political light.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Dragan Damjanović, Zvonko Maković, Željka Miklošević, Andrea Smetko, Vjeran Pavlaković and, especially, Karin Doolan for their generous assistance with the research for this essay, and to Giulia Carabelli, Miloš Jovanović, Thomas Meaney and John Paul Newman for their insightful, eagle-eyed comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributor

Jeremy F. Walton is a cultural anthropologist whose research resides at the intersection of memory studies, urban studies and the new materialism. He leads the Max Planck Research Group, “Empires of Memory: The Cultural Politics of Historicity in Former Habsburg and Ottoman Cities,” at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity. Dr. Walton received his Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Chicago in 2009. His first book, Muslim Civil Society and the Politics of Religious Freedom in Turkey (Oxford University Press, 2017), is an ethnography of Muslim NGOs, state institutions, and secularism in contemporary Turkey. “Empires of Memory,” which he designed, is an interdisciplinary, multi-sited project on post-imperial memory in post-Habsburg and post-Ottoman realms.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The official video of the song, by the pop group Zaprešić Boys, is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FgMi9xsY-Ew (accessed 14 May 2019).

2 Ban, roughly translated as ‘Count’ or ‘Viceroy’, was the title of the military ruler of Croatia, appointed by the Hungarian and later Habsburg sovereign. For background, see Tanner Citation2001, 7 ff.

3 A serendipitous resonance: The name of the pop-rock group responsible for the Croatian 2018 World Cup anthem, the Zaprešić Boys (see footnote 1 above), celebrates the town in which Jelačić's schloss, Novi Dvori, is located.

4 As John Paul Newman and Tamara Scheer aptly note, ‘Jelačic … embodied a variety of identifications in mid-nineteenth century Habsburg society: an imperial loyalist, a soldier and a politician, an avatar of South Slav cultural reciprocity, and a champion of Croatian nationalism’ (Citation2018, p. 154).

5 This ‘Triune Kingdom’ (Trojedna Kraljevina), consisting of Croatia (here specifically meaning the territories surrounding Zagreb), Slavonia and Dalmatia, was more notional than real, an object of aspiration for the Illyrian Movement that sought to unite Croats and South Slavs within the Empire on the model of a Medieval Croat polity. Among the many difficulties facing practical realization of the Triune Kingdom was its division between Hungarian sovereignty (Croatia and Slavonia) and Austrian sovereignty (Dalmatia) within the Empire. Nonetheless, in the ferment of 1848–1849, Jelačić briefly exerted titular authority over the three Croat realms. See Korunić Citation1998 for further context.

6 Only a year later, the 1867 Austro-Hungarian Compromise established the structure of dual sovereignty that persisted until the Empire's collapse in 1918, and Hungarian rule over the Kingdoms of Croatia and Slavonia recommenced. Jelačić's status as an embodiment of Croat and South Slav political identity and resistance waxed during this era – in 1901, for instance, Ognjeslav Utješinović Ostrožinski composed the patriotic hymn ‘Ustani, Bane’ (‘Rise, Ban’), which remains a touchstone among Croats today.

7 In her appropriately monumental tome, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, Rebecca West describes the monument to Jelačić as she encountered it during her travels in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia: ‘[T]his is one of the strangest statues in the world. It represents Yellatchitch (sic) as leading his troops on horseback and brandishing a sword in the direction of Budapest, in which direction he had indeed led them to victory against the Hungarians in 1848, and this is not a new statue erected since Croatia was liberated from Hungary. It stood in the market-place, commemorating a Hungarian defeat, in the days when Hungary was master of Croatia, and the explanation does not lie in Hungarian magnanimity’ (West Citation1994 [Citation1940], p. 48, quoted in Blau and Rupnik Citation2007, p. 46).

8 The statue was a particular abomination for Tito and his comrades because Marx himself had excoriated Jelačić as a reactionary in a contemporary reflection on the revolutions and counterrevolutions of 1848–1849 (Povijest.hr Citation2019).

9 Notably, a triumphal video detailing both the restoration process and the ceremonial return of the statue to the square is featured in the exhibition on socialist-era Zagreb in the City Museum. The placement of the screen on which the video plays is telling: It is mounted on the replica of the Partizanka statue (see ) that covered the monument to Jelačić in 1945–1947.

10 A Google image search confirms this: The results of a search for ‘Ban Jelačić’ are, overwhelmingly, photographs of the monument and square.

11 Gotovina was indicted by the ICTY in 2001 to stand trial for war crimes that occurred during ‘Operation Storm’ (Oluja), one of the final major battles of the Homeland War (Domovinski Rat) between Croatian military forces and those of the breakaway Republic of Serbian Krajina (Republika Srpska Krajina) (Pavlaković Citation2010, p. 1707). I thank Vjeran Pavlaković for alerting me to the role of the monument to Jelačić in what he calls the ‘construction of the Gotovina symbol’ (ibid., p. 1716).

12 Nor is susceptibility to the nationalist potency of the statue limited to those on the rightwing of the Croatian political spectrum. In 2012, an ‘international conference of nationalists’ was held in Zagreb, including members of Hungary's far-right Jobbik party. In response, an online editorial in a leftwing publication, titled ‘The Hungarians are Coming, Rise Ban Jelačić!’ (Stižu Mađari ustani bane Jelačiću!), satirically proposed that the ‘conference’ should convene beneath the statue itself (Gavlović Citation2012). The headline also echoed the famous hymn to Jelačić, ‘Ustani, Bane’ (‘Rise, Ban’) (see footnote 6 above).

13 It is worth noting that another iconic representation of Ban Jelačić, an 1849 portrait by Viennese artist Josef Kriehuber, is featured on the obverse of the 20 kuna Croatian banknote. In a striking gesture of anachronism, the banknote pairs Jelačić with another national(ized) icon, the Vučedol Dove (vučedolska golubica), dating from the 3rd millennium BCE and associated especially with the Slavonian city of Vukovar. The banknote, a consummate quotidian object, is an even more ubiquitous miniaturization of the Ban than the stamp.

14 The laminated image of the stamp cleverly unites and reconciles two opposite perspectives on the monument, one from the east and one from the west. When the Ban returned to the square in 1990, his orientation was shifted 180 degrees, from north to south, evidently for aesthetic reasons (Damjanović Citation2016, p. 116). On the stamp, we see an impossible arrangement of structures: a neoclassical building that once stood on the southwest corner of the square appears to abut the City Savings Bank, on the east side of the square.

15 For comparison, see my remarks on the aesthetics and politics of miniaturization in Istanbul's miniature theme park, Miniatürk, especially in relation to the miniature of version of the iconic statue of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk that stands in Istanbul's Taksim Square (Walton Citation2017, p. 202 ff.).

16 A sour note in the celebration for many (including me) was the decision to invite Marko Perković ‘Thompson’, an infamous far-rightwing Croatian troubadour, onto the bus and, later, stage. For many friends and interlocutors, this incorporation of extreme nationalist sentiment politicized the collective ‘Croatian’ triumph.

17 While beyond my purview here, a pantheon of other political and military figures, including Matija Gubec, Nikola Subić Zrinski (Walton Citation2019c), Fran Krsto Frankopan and Petar Zrinski, and Stjepan Radić, as well as Gotovina and Praljak in recent years, embody this genealogy and public culture of martyrdom in Croatia. See also Pavlaković Citation2010, 1725.

References

- Argenti, N., ed., 2017. Post-Ottoman topologies. A special issue of Social Analysis 61 (1), 1–25.

- Barkey, K., 2008. Empire of difference: the Ottomans in comparative perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Benjamin, W., 1968. Theses on the philosophy of history. In: H. Zohn, trans., Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books, 253–264.

- Blau, E. and Rupnik, I., 2007. Project Zagreb. Transition as condition, strategy, practice. Barcelona: Actar.

- Carabelli, G., 2019. Habsburg coffeehouses in the shadow of the empire: revisiting nostalgia in Trieste. History and Anthropology, 30 (4), 382–392. DOI:10.1080/02757206.2019.1611574.

- Crang, M. and Thrift, N., eds., 2000. Thinking space. London: Routledge.

- Damjanović, D., 2016. Zagreb architectural atlas. Zagreb: AGM.

- Danforth, N., 2016. The Ottoman Empire from 1923 to today: in search of a usable past. Mediterranean Quarterly, 27 (2), 5–27.

- Daughton, J.P., 2006. An empire divided: religion, republicanism, and the making of French colonialism, 1880-1914. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Durkheim, E., 1995. The Elementary forms of religious life. K.E. Fields, trans. New York: Free Press.

- Faulkner, W., 2011 [1950]. Requiem for a nun. New York: Vintage International.

- Gavlović, T., 2012. Stižu Mađari ustani bane Jelačiću! Dalje.com, 11 April. Available from: http://arhiva.dalje.com/hr-zagreb/stiu-maari-ustani-bane-jelaiu/429244 [Accessed 17 May 2019].

- Graan, A., 2013. Counterfeiting the nation?: Skopje 2014 and the politics of nation branding in Macedonia. Cultural Anthropology, 28 (1), 161–179.

- Grant, B., 2001. New Moscow monuments, or, states of innocence. American Ethnologist, 28 (2), 332–362.

- Hametz, M. and Klabjan, B., 2018. A place for Sissi in Trieste. In: M. E. Hametz and H. Sclipphacke, eds. Sissi’s world: the Empress Elisabeth in memory and myth. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 103–130.

- Hrvatski Povijesni Muzej, 2009. Uspomene na Jednog Bana / Memories of a Ban. Ostavština Jelačić u Hrvatskom Povijesnom Muzeju / The Jelačić Legacy in the Croatian History Museum. ( Museum Exhibition Catalogue). Zagreb: Hrvatski Povijesni Muzej.

- Jovanović., 2019. Whitewashed Empire: historical narrative and place marketing in Vienna. History and Anthropology, 30 (4), 460–476. DOI:10.1080/02757206.2019.1617709.

- Judson, P.M., 2016. The Habsburg Empire: A new history. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Kivelson, V.A. and Suny, R., eds., 2017. Russia’s empires. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Korunić, P., 1998. Hrvatski nacionalni program i društvene promjene za revolucije 1848/49. godine. Radovi – Zavod za hrvatsku povijest, 31, 9–39.

- Lefebvre, H., 1991. The production of space. D. Nicholson-Smith, trans. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Mataušić, N., 2001. A Gdje je Spomenki Banu? Iz Muzejske Teorije i Prakse, 32 (1-2), 127–129.

- Mazzarella, W., 2009. Affect: what is it good for? In: S. Dube, ed. Enchantments of modernity: empire, nation, globalization. London: Taylor & Francis, 291–309.

- Mazzarella, W., 2013. Censorium: cinema and the open edge of mass publicity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mazzarella, W., 2017. The mana of mass society. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Milčec, Z., 1990. Povratak Bana. Spomenik hrvatskog ponosa i hrvatskog srama. Zagreb: Bookovac.

- Mishra, P., 2012. From the ruins of empire: the intellectuals who remade Asia. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Newman, J.P., and Scheer, T., 2018. The Ban Jelačić trust for disabled soldiers and their families: Habsburg dynastic loyalty beyond national boundaries, 1849–51. Austrian history yearbook, 49, 152–165.

- Nora, P., 1989. Between memory and history: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Representations, 26 (Spring), 7–24.

- Pavlaković, V., 2010. Croatia, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and General Gotovina as a political symbol. Europe-Asia studies, 62 (10), 1707–1740.

- Povijest.hr, 2019. Zašto Karl Marx i komunisti nisu voljeli bana Josipa Jelačića? – 1849. Available from: https://povijest.hr/nadanasnjidan/zasto-karl-marx-i-komunisti-nisu-voljeli-bana-josipa-jelacica-1849/ [Accessed 17 May 2019].

- Rao, R., 2016. On statues. The Disorder of Things [online], 2 April. Available from: https://thedisorderofthings.com/2016/04/02/on-statues/ [Accessed 14 May 2019].

- Stewart, S., 1993. On longing: narratives of the miniature, the gigantic, the souvenir, the collection. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Stewart, K., 2007. Ordinary affects. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Stoler, A.L., 2016. Duress: imperial durabilities in our times. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Tanner, M., 1997. Illyrianism and the Croatian Quest for Statehood. Daedalus, 126 (3), 47–62.

- Tanner, M., 2001. Croatia: a nation forged in war. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Thrift, N., 2004. Intensities of feeling: towards a spatial politics of affect. Geografiska Annaler, 86 (1), 57–78.

- Trouillot, M.R., 1995. Silencing the past. Power and the production of history. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Vijesti, H.R.T., 2017. Na izricanju presude Slobodan Praljak popio otrov i preminuo. Available from: https://vijesti.hrt.hr/417745/sudac-agius-ovo-je-bio-vrlo-dug-i-slozen-postupak [Accessed 17 May 2019].

- Walton, J.F., 2010. Practices of neo-Ottomanism: making place and space virtuous in Istanbul. In: D. Göktürk, L. Soysal, and İpek Türeli, eds. Orienting Istanbul: cultural capital of Europe? New York: Routledge, 88–103.

- Walton, J.F., 2016. Geographies of revival and erasure: neo-Ottoman sites of memory in Istanbul, Thessaloniki, and Budapest. Die Welt Des Islams, 56 (3–4), 511–533. DOI:10.1163/15700607-05634p11.

- Walton, J.F., 2017. Muslim civil society and the politics of religious freedom in Turkey. New York: Oxford.

- Walton, J.F., ed., 2019a. Ambivalent legacies: political cultures of memory and amnesia in former Habsburg and Ottoman lands. A special issue of History and Anthropology, vol. 30 (4).

- Walton, J.F., 2019b. Introduction: textured historicity and the ambivalence of imperial legacies. History and Anthropology, 30 (4), 353–365. DOI:10.1080/02757206.2019.1612387.

- Walton, J.F., 2019c. Sanitizing Szigetvár: on the post-imperial fashioning of national memory. History & Anthropology, 30 (4), 434–447. DOI:10.1080/02757206.2019.1612388.

- West, R., 1994 [1940]. Black lamb and grey falcon. New York: Penguin Books.