ABSTRACT

How might we understand the forms of mediatized politics that are signified under the dreary heading of the ‘culture war(s)’? This article addresses this question in the form of seven theses. Informed by a distinct theoretical reading of Laclau and Mouffe’s concept of antagonism, I highlight the anti-political character of culture war discourses, particularly as amplified in a public culture dominated by the social media industry. The seven theses are prefaced by an overview of the category of ‘cancel culture’, in light of its recent prominence as an object of culture war discourse. I highlight the primary role of far-right actors in the normalization of culture-war conflicts that persecute different identities, but also critique the online left’s entanglement in sedimented antagonisms that primarily benefit reactionary actors. The theses stress the repressive effects of culture war discourses on our collective political imagination. They redescribe some of the fault lines of a familiar terrain by thematizing the differences between a moralized and radical democratic understanding of political antagonism.

Introduction

When Donald Trump gave his July 2020 Independence Day speech, he broached a topic that became a default talking point of his presidential campaign speeches for the rest of the year: the evils of so-called cancel culture. Cancel culture was framed as signifying an existential challenge to everything embodied in the mythology of the 1776 declaration of independence. Trump did not refer explicitly to the Black Lives Matter protests then taking place across the U.S., but referenced them when suggesting that ‘as we meet here tonight … [a]ngry mobs are trying to tear down statues of our founders’ (Trump Citation2020). Trump identified one of the mob’s ‘weapons’ as ‘cancel culture’, which he equated with ‘driving people from their jobs, shaming dissenters, and demanding total submission from anyone who disagrees’. This culture was framed as ‘the very definition of totalitarianism’: ‘completely alien’ to his own extraordinarily ahistorical image of a beatific, tolerant America.

Media interest in the speech partly explains why the term ‘cancel culture’ records its peak worldwide usage in July 2020. However, another significant media event three days after Trump’s speech offers a fuller explanation for why cancel culture seemed like an especially urgent topic in July 2020. When an ideologically eclectic group of academics, intellectuals and writers (including Noam Chomsky, Michael Ignatieff, J.K. Rowling and Deirdre McCloskey) published a letter in Harper’s Magazine on July 7 under the heading of ‘A Letter on Justice and Open Debate’, they made no direct reference to something called cancel culture (Ackerman et al. Citation2020). Nonetheless, the letter was widely read as critiquing the practices associated with the term (Clark Citation2020, Ng Citation2022). It lamented a censoriousness in public discourse that it suggested went beyond the ‘radical right’, manifest as a general ‘intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming, and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty’.

I begin with these observations about cancel culture because they offer a useful starting point for thinking about the current iteration of the so-called culture war(s) (Hartman Citation2018). In his 1991 book that popularized the term, James Davison Hunter (Citation1991) conceptualized the ‘culture wars’ as forms of ‘political and social hostility rooted in different systems of moral understanding’ (p. 42). He stressed the ‘polarizing impulses or tendencies’ of then distinctly American conflicts which have since been internationalized as a ‘conduit for the gradual normalization of an emerging far-right authoritarian order’ (Hlavajova Citation2020, p. 9). Hunter stressed the role of media in the staging of these conflicts because they define the atmosphere in which ‘public discussion takes place’ (p. 161). As he put it:

… the media technology that makes public speech possible gives public discourse a life and logic of its own, a life and logic separated from the intentions of the speaker or the subtleties of the argument they employ. (p. 34)

The rest of the article has three main parts. I begin with a brief overview of ‘cancelling’ talk, which metamorphosized from Black Twitter meme to political keyword in the U.S., U.K. and elsewhere. This section provides an initial empirical grounding to the argument, as an antidote to analyses that take the terms of culture war politics for granted. I then segue to a discussion of how the notion of antagonism has been developed in the work of Ernesto Laclau, Chantal Mouffe, Oliver Marchart and others. I argue that the ‘post-Marxist’ discourse theoretical tradition offers useful ethico-political resources for critiquing the anti-political logic of culture war discourses. I then move to the paper’s main section, outlining seven one-sentence theses for thinking about the current iteration of the culture war, especially their media dynamics. Each thesis is supported by fragmentary notes that try to trouble the sedimented terms of culture war conflicts. The paper ends with a brief postscript that clarifies why a radical democratic conception of political antagonism offers a useful antidote to the (anti)politics of the culture wars.

A brief overview of ‘cancel culture’ talk

‘Cancel culture’ is usually talked about judgmentally, both by people who criticize it and those who dismiss the very existence of such a notion. Eve Ng’s (Citation2020) definition captures the context in which people started to talk about ‘cancelling’ as a distinct phenomenon. She describes cancel culture as:

… the withdrawal of any kind of support (viewership, social media follows, purchases of products endorsed by the person, etc.) for those who are assessed to have said or done something unacceptable or highly problematic, generally from a social justice perspective especially alert to sexism, heterosexism, homophobia, racism, bullying, and related issues. (Ng Citation2020, p. 623)

According to Know Your Meme (Citation2021), one of the earliest references to ‘cancelling’ in a legacy media space was a January 2016 MTV article that cited it as an example of ‘new’ need-to-know teen slang. The supporting illustration captured the term’s transactional connotations in a playful way. It imagined a chat between two friends scrolling through profiles on a dating app:

Me: ‘Should I swipe right? One of his ‘interests’ is [the rock band] Nickelback.’

Friend: ‘CANCEL.’ (Trudon Citation2016)

Ng (Citation2020, Citation2022) highlights the role of fandom cultures in mainstreaming cancelling discourses. Her examples are not limited to the U.S.: her 2022 book includes Chinese examples where online antipathy to cultural products seen as denigrating the country ‘become explicitly entwined with nationalism and national-level politics’ (Ng Citation2022, p. 27). Ng (Citation2020) cites one early 2016 example when fans of the television series ‘The 100’ expressed their annoyance on Twitter at the ‘death of a lesbian character, killed off just after she and another female character had made love for the first time’ (Ng Citation2020, p. 622). Fans accused the show of ‘queerbaiting’ them (p. 622). The show’s producer, Jason Rothenberg, lost 14,000 Twitter followers and later apologized for the decision. As Ng puts it:

Rothenberg’s status as a cis straight white man, accused of exploiting mostly young, queer female viewers, was tailor-made for the dynamics of cancel culture: a collective of typically marginalized voices ‘calling out’ and emphatically expressing their censure of a powerful figure. (p. 623)

The term cancel culture partly redescribes phenomena also named as ‘call out-culture’ (Clark Citation2020, Ng Citation2022), as exemplified by the digital activism of the #MeToo movement. The sexual abuse allegations surrounding the singer R Kelly illustrated this dynamic in action, when Twitter users disseminated the hashtag #cancelRKelly. Another example of the term’s mainstreaming was Kayne West’s citation of it in a 2018 New York Times interview, when he declared himself ‘cancelled’ because of his public support for Trump (Caramanica Citation2018). The case exemplified ironies often noted by critics of cancel culture talk – of how high-profile public figures use their privileged media access to decry how they are being censored and denied media visibility.

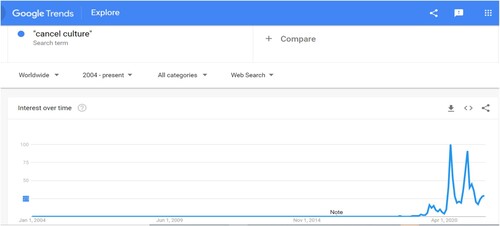

Cancelling has assumed a more pejorative meaning over time: transmuted into the ‘reductive and malignant label “cancel culture”’ (Clark Citation2020, p. 88). The reification of the term exemplifies a familiar trajectory where digital practices ‘initially embraced as empowering’ are later ‘denounced as emblematic of digital ills’ (Ng Citation2020, p. 621). A search for its worldwide use on Google Trends shows its increased cultural circulation over time. illustrates that the Google algorithm did not even register the term till late 2018, but within 18 months it had reached its moment of peak usage. The second peak month of March 2021 illustrates how the term has assumed a currency beyond the Trump presidency.

A search for the term on the Factiva news database also captures its quick rise to prominence. ‘Cancel culture’ recorded a mere 26 results in 2018. By 2019 it featured 1246 times, rising to 6576 in 2020, 14764 results in 2021, and dropping to 9947 results in 2022.

Highlighting the term’s quantitative circulation only reveals so much: the term is used in diverse ways (Ng Citation2022) that cannot be adequately mapped here. The right may have been relatively successful in hegemonizing its meaning. But many people on Twitter refer to the term ironically or reappropriate it to highlight the hypocrisy of right-wing rhetoric. For example, when the U.K. government signalled plans to introduce ‘free speech’ legislation for universities in early 2021, the move was reported as a ‘crackdown on woke and cancel culture’ (Varga Citation2021). The plans were announced at a time when the University of Leicester signalled its intention (later carried out) to sack nine critical management scholars, on the grounds that their scholarship was incompatible with the strategy of the Business School (Halford Citation2021). This prompted some Twitter users to cite the Leicester case as a real example of cancel culture in the neoliberal university. The ‘war on critical race theory’ (Goldberg Citation2021) has brought the political hypocrisy to an obscene level in the U.S., with indignation about left-wing cancel culture somehow reconciled with the passing of decrees determining what teachers can and cannot say about race (and gender) in the classroom.

Cancel culture is used mainly as a pejorative by an alliance of far right, conservative, libertarian, and neoliberal identities to attack the left. ‘The left’ is so loosely defined that it can potentially incorporate everything from the ‘progressive neoliberalism’ (Fraser Citation2017) of the U.S. Democratic Party establishment, the street politics of Antifa, Marxist-Leninist communism, to Ben and Jerry’s ice cream. This collapsing of political differences is given a scientific gloss in analyses of ‘cancel culture’ that treat ‘left’ and ‘liberal’ identities as interchangeable (Norris Citation2021, p. 28). Nonetheless, the meaning of cancel culture cannot be adequately grasped through a simple left/right binary, because of its capacity to act as a ‘floating signifier’ (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001). It is also used by some self-described leftists to critique other leftists for propagating a ‘merely’ performative idea of social justice.

When contextualized as part of the longer history of the culture wars, cancel culture talk offers a new inflexion on familiar antagonisms. We see antecedents in earlier denunciations of ‘political correctness’ (Weigel Citation2016), conservative critiques of 1960s ‘adversary culture’ (Hartman Citation2018), and the paranoia of cold war anti-communism (Singh Citation1998). It is part of a post-Gamergate vocabulary for naming heterogenous political enemies: articulated as part of a ‘chain of equivalence’ (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001) that renders it interchangeable with other signifiers like ‘woke culture’ and ‘social justice warriors’ (Phelan Citation2019). This vocabulary is shaped by a political aesthetic that turns the violent, comedic disparaging of the left into a form of popular entertainment, energized by the ‘libidinal and affective aspects’ of social media (Gilroy Citation2019, p. 3). Rebecca Lewis (Citation2018) highlights the role played by an assemblage of U.S. far right, conservative and libertarian political identities in the mainstreaming of reactionary discourses, enabling ideological resonances between ‘alt-tech’ platforms like Reddit and 4chan and more popular platforms like YouTube (Finlayson Citation2022). One important node in this ‘alternative influence network’ is the ideologically heterogenous grouping dubbed the ‘intellectual dark web’ (Lewis Citation2018). Here figures like Joe Rogan and Dave Rubin affirm the cultural vitality of their own media platforms, in contrast to the platitudinous conventions of legacy media (Phelan Citation2019). These discourses are then amplified in other media spaces; much like the rapid ascent of ‘political correctness’ talk in the 1990s (Weigel Citation2016), the indignation of traditional media gatekeepers (Clark Citation2020) plays a key role in making cancel culture a target of contempt and ridicule. Right-wing news outlets depict other corporate media institutions as ‘woke leftists’, giving new life to old critiques of the ‘liberal media’. Left-liberal media hype and amplify the news value of far-right actors (Phillips Citation2018, Mondon and Winter Citation2020). Twitter becomes a key theatre of culture war, driven by algorithms that privilege right-wing talking points (Milmo Citation2021).

The Trump campaign’s fixation on cancel culture inevitably made its imprint in other political cultures (McAuley Citation2021). Hansard’s (Citation2021) record of U.K. parliamentary transcripts shows that the term was first used on October 20, 2020. A few months on, it had become a keyword for legitimizing the Tory government’s legislative plans to protect ‘free speech’. It was later cited in Boris Johnston’s 2021 party conference speech, in what The Guardian described as culture war ‘red meat’ for his supporters (Allegretti Citation2021).

Cancel culture has also become an object of moral panic among French political elites (McAuley Citation2021). The context was shaped by a speech Emmanuel Macron gave in October 2020, when he criticized ‘certain social science theories entirely imported from the US’ for ‘ideologizing’ discussions of Islam in France (Onishi Citation2021). The speech ‘was widely praised by the French establishment’ (McAuley Citation2021), and animated contemptuous talk about ‘cancel culture’ (Onishi Citation2021). The questions it raised were recontextualized after the brutal beheading of the schoolteacher Samuel Paty a few weeks later, by an assailant who reportedly justified murder in the name of Islam. Macron’s gesture of linking the condition of the French polity to the country’s universities was reinforced by a letter published in Le Monde by over 100 academics (Dawes Citation2020). The letter reaffirmed the suggestion of one government Minister that ‘l’islamo-gauchisme is wreaking havoc’ at French universities (Durand Citation2020). It articulated a heightened public crisis about a distinctly French iteration of the culture wars which textured the atmosphere of a 2022 presidential election campaign that registered strong support for different far-right candidates.

Elsewhere, it is not hard to find random examples of the transnational weaponization of cancel culture talk. In July 2020, the Dutch far-right MP, Thierry Baudet, wondered – with mock sincerity – if a reporting centre needed to be established for concerned citizens to report ‘cancel culture’ activists (Jongeneel Citation2021). The term was used knowingly on the RT television channel in February 2022, during a discussion of the relationship between Russia and the West that denounced ‘wokeism’ (Crosstalk Citation2021). Eight months on, it was cited in a Putin speech that generated headlines about how ‘Putin slams “cancel culture” and trans rights’ (Cheng Citation2021). Putin has continued to trade in culture war motifs since the start of the 2022 Ukrainian war, in one instance comparing Western boycotts of Russian artists to the ‘cancelling’ of JK Rowling (Sauer Citation2022).

The term is primarily used by the right to critique the left. However, as the Harper’s controversy suggests, ‘cancel culture’ is also an object of critique for people who self-identify as progressive or left-wing. These critiques have one antecedent in a left-wing critique of political correctness (Hall Citation1994, Denvir Citation2021). For example, Barack Obama critiqued ‘woke’ activism in 2019, in comments that were reported as an intervention on ‘cancel culture’ (Rueb and Taylor Citation2020). Conversely, cancel culture is also denounced by people on the radical left who would have little time for Obama’s politics. These critiques sometimes take the form of antagonism to everything incarnated in a chain of equivalence linking the signifiers ‘liberalism’, ‘identity politics’ and ‘woke capitalism’. For example, in an article titled ‘The contradictions of ‘cancel culture’: Where elite liberalism goes to die’, Chris Hedges (Citation2021) decries the smug ‘moral absolutism’ of cancel culture: what he describes as culture war ‘fodder’ that turns ‘anti-politics into politics’.

The moralizing dimensions of cancel culture have also been critiqued from an agonistic left perspective (see Maddox and Creech Citation2020), which questions the excesses of cancel culture, while expressing greater sympathy for the practices delegitimized under that heading. One exemplar was a January 2020 video produced by the Left YouTuber ContraPoints, aka Natalie Wynn, titled ‘Cancelling’ (ContraPoints Citation2020) The video reflected on Wynn’s painful experience as a transwoman who (in her own words) was ‘cancelled’ by trans activists, but also offered rich theoretical insights on the workings of cancel culture. Similarly, Richard Seymour questions the familiar left-wing argument that cancel culture is merely a fantasmatic object created by the far right (Seymour Citation2019a, Citation2019b). His work explores how all of us can be complicit in the censorious, even fascistic, aspects of what he calls the ‘social industry’ (Seymour Citation2019a).

Antagonism and political conflict

The previous section described how ‘cancel culture’ has become a culture war keyword that circulates in universes well beyond its origins in Black Twitter memes. The objective was to give an empirical context to the discussion of the seven theses, and to track the dynamics of how culture war objects of discourse are brought into being. I now need to make the ‘necessary detour’ (Hall Citation2019, p. 81) through theory, to clarify why the notion of antagonism is central to my analysis.

Laclau and Mouffe’s discourse theory is informed by a distinction between ‘politics’ and ‘the political’ (Laclau Citation1990, Citation2004, Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001, Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). ‘Politics’ signifies the everyday social practices that shape, and circumscribe, how we think about politics and political differences. Conversely, ‘the political’ signifies an ontological-level perspective on politics that would question the assumptions underpinning those sedimented norms. It highlights the politicality of all social practices, not just those conventionally named as ‘political’.

Laclau and Mouffe equate the political with antagonism. Antagonism is often invoked to affirm the necessity of political conflict. Some scholars blame Laclau and Mouffe’s valorization of populist politics for legitimizing the kind of polarized politics (Waisbord Citation2018) associated with the culture wars. From this perspective, it might even be argued that the proposition that any social practice can be politicized has become an entirely banal feature of a culture war imaginary where anything can potentially be weaponized as a marker of political difference.

It’s not hard to find passages in Laclau (the main theorist of antagonism) that affirm this stereotypical image of antagonism: his work, after all, is aversive to discourses that repress the conflictual logic of the political. Moreover, ever since their landmark 1985 book Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, both Laclau and Mouffe (Citation2001) engaged with the question of how to articulate a left-wing counter-hegemonic formation that would bring together an alliance of different identities in opposition to a hegemonic neoliberal antagonist (Phelan Citation2021). However, antagonism should not be reduced to a friend/enemy conception of the political (Marchart Citation2018, Mouffe Citation2005a), and it is unhelpful to conflate a nihilistic understanding of political conflict with Laclau’s ontological account of antagonism. When Laclau describes ‘the social’ as antagonistic (and frames all identities as marked by antagonism) he means something different from the everyday use of antagonism as a signifier of interactions that are obnoxious or unrelentingly conflictual. Rather, antagonism signifies the ‘limits’ of every empirical attempt to construct a fully objective or positive identity. As Oliver Marchart (Citation2018) puts it, antagonism names an ontological condition ‘which undermines the very positivity of “positive facts”’ (p. 10).

In the context of this paper, this understanding of antagonism has two key implications. First, it sensitizes us to everyday cultural identities that obscure their contingency (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007) by presenting themselves in performatively certain ways. This should not be misconstrued as an aberrant social condition. On the contrary, it is the mode of being that inflects most of our everyday routines; to live in a manner that would constantly acknowledge the contestability of everything we do would be to internalize ‘the discourse of the psychotic’ (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001, p. 112). Nonetheless, this point is important to any conjunctural critique of how politics is done on platforms like Twitter that incentivize the consistent performance of an online identity (Seymour Citation2019a, Nguyen Citation2021, Törnberg and Uitermark Citation2022). In a world of the ‘branded self’ (Hearn Citation2008), we might say that the architecture of social media platforms plays an anchoring role in normalizing the expectation that the self be presented in an ‘on-brand’ fashion.

Second, this perspective sensitizes us to the depoliticizing aspects of cultural conflicts that are articulated in the empirical form of a seemingly essential antagonism between a naturalized ‘us’ and ‘them’. Put another way, it highlights heterogenous discursive possibilities (Thomassen Citation2019, Phelan Citation2021) that are repressed by the ritualistic performance of self/other conflicts that are represented as ‘unbridgeable’ (Gilroy Citation2019, p. 2). This way of thinking about antagonism calls into question the assumed purity of any friend/enemy dualism, and goes against a simplistic reading of Laclau that sees little more than a legitimation of ‘permanent conflict between irreconcilable actors’ (Waisbord Citation2018, p. 23). Antagonism is instead reframed as a matter of degree or tendency (Thomassen Citation2019). The notion of a ‘pure antagonism’ becomes ‘impossible’ (p. 56), even when the habitual staging of actually existing social antagonisms can suggest pure differences between the self and other. The assumption that political antagonism must take the form of unrelenting us/them conflicts is reconceptualized as one ideological rendering of antagonism that should not exhaust our capacity to think of political conflict in other ways.

How might this understanding of antagonism offer a productive theoretical lens for thinking about culture war conflicts? The next section explores this question in a more concrete way. But the primary theoretical benefit is that antagonism becomes an ethico-political resource for critiquing the ‘anti-political’ (Phelan Citation2022) and ‘post-political’ (Mouffe Citation2005a, Glynos Citation2021) valences of cultural war discourses. The notion of antagonism may suggest parallels with the metaphor of politics as a ‘perpetual war of all against all’ (Marchart Citation2018, p. 64). In Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, Laclau and Mouffe (Citation2001) developed their understanding of antagonism with reference to Gramsci’s concept of ‘war of position’ (p. 21), while Mouffe (Citation2022) also invokes the concept in her most recent book. Yet Marchart (Citation2018) suggests it would be a mistake to conflate a Laclauian understanding of antagonism with a ‘polemological understanding of antagonism’ as a ‘war’ against an ‘enemy’ that needs to be ‘destroyed’ (p. 79). In the sense valorized here, antagonism is not identical with the endless reproduction of the ‘ontic’ (p. 73) terms of an existing political conflict, but rather prefigures a radical democratic and agonistic imaginary (Connolly Citation2005, Mouffe Citation2005a, Glynos Citation2021) that denaturalizes an existing constellation of identities, alliances, enmities and divisions, It cultivates a form of critique that says ‘“yes” and “no” at one and the same time’ (Hall Citation2019, p. 82). Yes, to the antagonistic condition of the social. But no to the social forms that political antagonism takes in a culture war imaginary.

This approach reframes the culture wars as a horizon of ‘sedimented antagonisms’ (Marchart Citation2018, p. 123) that locks political conflict into a repressive imaginary, and inhibits discourses that do not cohere with the affective force of absolute us/them conflicts. The notion of a sedimented antagonism is somewhat contradictory for discourse theorists, as the sedimented logic of ‘the social’ is usually opposed to the antagonistic logic of ‘the political’ (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007). However, for our purposes here, it can be correlated with the role played by media rituals (Couldry Citation2003) in representing the social world through the lexicon and imagery of culture war – a world where laments about the ‘toxic’ nature of today’s public culture are commonplace (Phelan Citation2022).

Conversely, my critique of the culture wars is motivated by a desire to break from the rituals that stage the sedimented antagonisms of the present (MacKenzie Citation2021), while also recognizing the inevitability of political conflict and disagreement. Instead of succumbing to a bleak political imaginary where human beings have no choice but reproduce hegemonic identity/difference (Connolly Citation2005) dualisms, critique becomes a practice of illuminating ‘the contingent nature of the given’ (Marchart Citation2018, p. 33). Analysing the culture wars means critiquing the primary role of authoritarian forces in producing a ‘society of enmity’ (Mbembe Citation2019, p. 1) and their desire to normalize a ‘particularist’ vision of society marked by fixed conflicts between different fixed identities (McGowan Citation2020). Yet, it also means confronting the entanglement of different progressive identities in conflicts that can impede the best universalizing, and solidarity-building, values of the left (McGowan Citation2020, Adler-Bell Citation2022). Put another way, it means formulating a radical democratic left analysis of the culture wars that doesn’t let one’s own side ‘off the hook’ (Hall Citation2019, p. 83).

Seven theses about the so-called culture war(s)

Below I outline seven theses about the culture wars that are especially attuned to the topics of media and cancel culture. The number of theses is something of a conceit. More could have been added, some could have been sub-divided, and each invites further elaboration. They can hardly claim to be a comprehensive account of everything that might be said about the culture wars. Instead, they are presented as fragmentary, digressive, and sometimes contradictory lines of thought that explore the contours of a familiar terrain. The pluralized ‘culture wars’ is more accurate, but for the sake of grammatical clarity I sometimes refer to the singular.

Thesis 1: The culture war signifies forms of politics that are paradoxically anti-political and energized primarily by the far right, but mainstreamed by their resonances with the anti-political tendencies of neoliberal and centrist discourses.

Those who are most committed to fighting the culture wars tend to be aligned to the political right and especially the far right. Think about how much of the rhetoric used to disparage the left is incubated in online far right sub-cultures (Nagle Citation2017). These forces internalize a political imaginary that paradoxically hates politics (Hay Citation2007): politics and politicization are framed as dirty words (‘vote for Trump, he’s not a politician’), even as they simultaneously articulate hyper-reactionary forms of politicization. Affirmation of the values of nation, Whiteness, Christian Heritage, gender norms, and constitutional originalism are rearticulated as offering their own legitimate claims to ideological ‘diversity’ and protection within a political culture controlled by censorious lefties (Tebaldi Citation2021). The moral panic about cancel culture exemplifies these (de)politicizing tendencies. Supporters of the political right recast themselves as persecuted victims in a public culture where previously marginalized identities (black, brown, people of colour, queer, trans) have claimed greater visibility (Ng Citation2022). The potentially profound differences between democratic and anti-democratic, combative and vicious, playful and humourless, forms of online criticism are annihilated under the impression of a singular phenomenon produced by a homogenous ‘left mob’. Describing something as an example of ‘cancel culture’ becomes a rote way of dismissing it out of hand: subsuming it into the horizon of the already known. However, this culture of hyper-reactionary anti-politics must be contextualized with reference to decades of neoliberal hegemony, and neoliberals’ own paradoxical articulation of a political rationality that is simultaneously hostile to politics (Brown Citation2019, Phelan Citation2019). The stereotypical centrist is likewise implicated, by their own post-political fantasy of a reasonable centre that could really hold if people would only see through the hallucinations of right and left ‘populists’. This anti-political doxa is internalized in practices aligned to an older mythical image of the ‘mediated centre’: Nick Couldry’s (Citation2003) term for media institutions that act as if their own value systems cohere with a mythical idea of society’s centre. A professional fidelity to hand-me-down journalistic values of objectivity, balance, neutrality, impartiality, and free speech endures, without adequately recognizing their role in the ‘mainstreaming’ of far-right discourses (Mondon and Winter Citation2020, Titley Citation2020). A doctrinaire interpretation of these values starts to be most stridently affirmed by the far right, as a foil to the hysteria of ‘the woke’.

Thesis 2: The culture war is sustained primarily by an anti-politics of the right and centre but also finds expression in an anti-politics of the left.

Much has been written since the 1990s about the rise of a ‘post-political’ culture (Hay Citation2007, Brown Citation2019). This is usually explained with reference to neoliberalism, for reasons noted in Thesis 1. Chantal Mouffe blames neoliberalism, particularly its Third Way iteration, for its ‘moralization of political discourse’ (Mouffe Citation2005b, p. 57). The moralization of politics cultivates a culture of moralized antagonism that demonizes opponents, at the expense of what see describes as a ‘properly political’ (Mouffe Citation2005a, p. 10) understanding of social conflict. Mouffe’s coupling of moralizing and depoliticizing logics is suggestive here, because it invites us to reframe the culture wars as a horizon of moralized (Hunter Citation1991) anti-politics. The far right represents the left as demonic (and simultaneously ridiculous). Centrist neoliberals represent the (radical) left as dangerous and polarizing because of its reliance on hopelessly antiquated ideologies. Jodi Dean’s (Citation2009) notion of ‘communicative capitalism’ offers one way of conceptualizing left anti-politics in a social-media driven public culture. We think we are doing politics when we tweet about injustice, but we are really enacting our assigned role as instrumentalized data points of Silicon Valley. The notion of sedimented antagonism offers another. One would not need to be a prolific Twitter user to be aware of its significance as a site of political identity work (Törnberg and Uitermark Citation2022) for strands of the contemporary left. These identities are articulated in opposition to various reactionary identities, in critical idioms that are justifiably moral, but often closer to a friend/enemy image of the political than the agonistic values commended by Mouffe. In the world of the Twitter left, much psychic energy can be expended in the sometimes obscure staging of various intra-left antagonisms, often performed as if they are intensely political or matters of great intellectual import. However, read through a radical democratic lens, these rituals might be characterized as anti-political because of how they serve to reinscribe sedimented antagonisms. Think of those parts of the online left that seem to get as much enjoyment from ‘owning the libs’ as the far right, sometimes appealing to a no-bullshit class politics that is expressed as a moralized antipathy to ‘identity politics’ and bourgeois ‘cancel culture’. Conversely, other strands of the online left can turn totalizing signifiers like ‘class reductionism’ into political weapons to dismiss other left identities or cast them as morally problematic in ways that illustrate the censorious stereotypes associated with cancel culture. To put the argument hyperbolically (and in a way that brackets out any critique of the limitations of Mouffe’s own argument – (see Phelan Citation2022)): all these sedimented forms of online politics might be described as anti-political because they involve a repetitive performance of given identities in a platform capitalist infrastructure that just wants all of us to keep performing our identities and differences online. If ‘identity politics’ (Seymour Citation2019a, McGowan Citation2020) is an impediment to a stronger left, we might therefore suggest it is a problem that implicates all of us, not just those who are represented – in a derisory fashion – as its exemplars. The messy thing called ‘the left’ badly needs to cultivate a culture of ‘agonistic respect’ (Connolly Citation2005) in its media practices if it is to be disentangled from the most corrosive aspects of culture war politics, both in how it acknowledges its own internal differences, but also in how it comports itself towards the elements of a universal public who are indifferent to the latest Twitterstorm.

Thesis 3: The culture wars normalize a culture of everyday online critique but in an antagonistic atmosphere that troubles an emancipatory conception of critique.

For all its faults, Twitter produces many examples of everyday critique that belie the image, habitually cultivated by users themselves, of the platform as a ‘hell-site’. Critique is articulated in playful ways that attest to the popularization of different critical theory vocabularies (Holm Citation2020), whether articulated on Academic Twitter, Black Twitter, Irish Twitter, or any other imagined Twitter public. At its best, this culture of popular critique enacts forms of creative public pedagogy that democratize the relationship between academic knowledge and public knowledge (Carrigan Citation2022). Theories once largely confined to the classroom or dismissed by the gatekeepers of an earlier media system become part of an everyday critical vocabulary for enacting a radical democratic vision of political antagonism. The moral panic about ‘woke culture’ can be partly read as a reactionary response to the mainstreaming of forms of public communication where concepts like ‘intersectionality’ and ‘white privilege’ have become everyday objects of discourse. At the same time, if we agree with Rita Felski’s (Citation2015) shorthand description of critique as a ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’ (a term borrowed from Paul Ricoeur), it is worth asking what being suspicious looks like in the current conjuncture. The increased visibility of reactionary forms of suspicion, partly enabled by the affordances of digital culture, is a marked feature of the current iteration of the culture wars that was accentuated during the COVID crisis. Claims made by governments, corporations, media organizations, and pharmaceutical companies are often justifiably regarded with suspicion. However, public criticisms of these and other targets is now habitually articulated in a hyper-reactionary register, as if to dramatize Bruno Latour’s (Citation2004) concerns about how ‘the weapons of social critique’ (p. 230) can be appropriated by authoritarian forces. To even speak of ‘critique’ in this context means disembedding the term from any normative conception of critique, but to focus instead on its capacity to morph in ways that produce unpredictable political antagonisms. Felski’s argument about the limits of a hermeneutics of suspicion suggests another angle on Thesis 3 that speaks to criticisms of how ‘left cancel culture’ is enacted online. Consider, for instance, the dynamic that plays out everyday on Twitter when someone (usually someone with a high profile on the platform) posts a tweet that others deem to be ‘problematic’ (Kaplan Citation2021). The charge is often entirely justified, which is one reason why it is disingenuous when dismissive meta-commentary about the reaction to the tweet explains everything with a prefabricated argument about ‘cancel culture’. However, whether it is or isn’t justified, if the tweet gets enough attention, a kind of market is created online that incentives others to produce their own critiques of the problematic tweet. The excesses of these cultural practices are illustrated by ContraPoint’s (2020) ‘cancelling’ video. Some people might engage in a detective-like trawl of the specific Twitter account looking for more problematic tweets to further exploit its ephemeral currency as a nodal point of online attention. Some might extend the scrutiny to accounts that expresses sympathy with the criticized target, with extra rewards accumulating when these accounts have a significant profile of their own. C. Thi Nguyen (Citation2021) reads these dynamics as illustrating a ‘gamification’ of communication that is built into Twitter’s design. The game ‘invite[s] us to instrumentalize our moral beliefs’ (p. 36), encouraging performances of moral outrage that can be wildly disproportionate to the nature of the initial wrongdoing. The ability to diagnose the moral failings of others becomes its own form of reward, flattering our capacity for ‘savvy critique’ (Andrejevic Citation2003, p. 185) in the process. There can be a class dynamic to these rituals (Finlayson Citation2021). The ability to label some statements as ‘problematic’ becomes, to some extent, a trained, cultivated skill that is disproportionately possessed by those with the ‘critical capital’ (Holm Citation2020) that comes from a university education in the humanities and social sciences. Nick Holm suggests that the popularization of critique attests to the relative success of cultural studies pedagogy in increasing public awareness about the reproduction of racist, sexist, classist, ableist, homophobic and transphobic discourses. Yet, he wonders if these clearly positive developments might make the possession of the requisite critical capital a more salient vector of social inequality (and social antagonism), particularly in a skills-oriented academic economy where a degree in the humanities and social sciences becomes a more high-end commodity. Catherine Liu (Citation2021) offers a polemical account of these class dynamics, castigating a ‘virtue hoarding’ educated elite for normalizing the hypervigilant gaze associated with social media cultures.

Thesis 4 The culture war is the site of a power struggle between different media cultures and universes, mediated in part by radically different articulations of accountability.

The culture of online critique discussed in Thesis 3 is often directed towards media and journalistic targets, but from an increasingly diverse range of ideological perspectives. The sedimented antagonisms of the culture wars paradoxically spawn an atmosphere of ‘“wild” antagonism’ (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001, p. 171), as discourses are recontextualized in unpredictable ways from one universe to another (Krzyżanowski Citation2020, Corcuff Citation2021). In a fragmented media ecology, asserting antagonistic opposition to some media cultures becomes an important psychic element in shaping the identity of other media cultures, whether in the form of far-right critiques of a demonic image of ‘the mainstream media’ (Figenschou and Ihlebæk Citation2019), radical left critiques of how mainstream media normalize far right discourses (Mondon and Winter Citation2020), or elite journalistic dismissals of the media critiques produced by different online publics. The dynamics of culture war politics in a ‘hybrid media system’ (Chadwick Citation2013) are exemplified by the antagonisms between traditional journalistic identities and the value systems of Twitter publics that shape cancel culture stereotypes (Clark Citation2020). We might think of it as a conflict over how democratic accountability work should be done and conceptualized (Montgomery Citation2008), as agents in both media universes justify their practices in the name of ‘accountability’. It is a conflict that takes place within elite journalistic institutions themselves, as illustrated by journalistic differences over how Black Lives Matter protests should be covered in The New York Times (Smith Citation2020). The image of the journalist-watchdog holding power to account, in the name of ‘the public’, has long been the mythical ideal centring journalism’s commitment to a liberal democratic credo. But the signifier ‘accountability’ also does important discursive work for Twitter publics when they rename stigmatized ‘cancel culture’ practices as forms of ‘accountability culture’ (Ng Citation2022, p. 272). The mythos of the journalistic watchdog is to some extent generalized in the networked subjectivities of Twitter publics. Even anodyne criticisms of a news story attest to the normalization of a civic impulse to ‘watch the watchdog’. When done at scale and intensity, the collectivization of this watchdog subjectivity might be described as cancelling in action. For Twitter publics acting in the name of social justice, these forms of online accountability work are justifiable, necessary and the very expression of a democratic ethos. Conversely, we might point to the normalization of a rather less flattering vision of accountability work that is exemplified by reactionary watchdogs who fixate on holding left-wing culture war targets to account. It is a form of media-politics that is articulated by far-right media outlets like Breitbart (Roberts and Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020). And it takes a sharp anti-democratic form in a culture of online abuse and hatred that disproportionally targets women and racial minorities (Waisbord Citation2020, Shringarpure Citation2021).

Thesis 5: The culture war becomes its own kind of economy that creates ‘market’ opportunities and risks for different actors.

It is impossible to talk about the culture wars without talking about the ‘attention economy’(Citton Citation2021) or the ‘outrage economy’ (Phipps Citation2020). The logic of what we might conceptualize as a distinct kind of culture war economy (supported its own networks of patrons, funders, investors, wholesalers and retailers) is articulated in the figure of the right-wing grifter. Think of someone like Toby Young in the U.K. who strives to regain the cultural standing he had in an earlier media age through a theatrical commitment to free speech and taglines that ‘Question Everything’ (Young Citation2021). Or think of an exemplar like Jordan Peterson, who found fame and notoriety by giving a scholarly legitimacy to the mocking of ‘social justice warriors’ (Phelan Citation2019). Alan Finlayson (Citation2022) captures this mix of commercial and political motivations in his notion of the ‘ideological entrepreneur’: archetypal culture war figures who are able to use the affordances of digital culture ‘to flourish apart from a political party or regulated journalistic outlet, earning a living directly from the promotion of a political world-view’ (p. 75). Conversely, we can point to another kind of culture war economy that is critiqued by the left (and sometimes the right) under headings like ‘woke capitalism’ and ‘woke neoliberalism’ (Kanai and Gill Citation2021, Sobande et al. Citation2022). Deploying such terms from the left is fraught, given the extent to which anti-wokeness has become a potent nodal point of reactionary politics. Nonetheless, they capture something socially real that is identifiable in how different institutions now brand their identities. These developments have a clear capitalist rationale, and perhaps we should not be entirely dismissive of the cultural significance of corporations aligning themselves with different progressive causes (see Feher and Callison Citation2019). At the same time, these marketing strategies can be deeply opportunistic, particularly when used as rhetorical cover for anti-worker policies. Consider the University of Leicester example mentioned earlier. University managers initially sought to give a progressive gloss to the decision to close medieval literature courses by invoking the notion of ‘decolonization’ (Regan Citation2021). Most egregiously, the university continued to market itself as a progressive ‘citize[n] of change’ (University of Leicester Citation2021) while sacking critical management studies scholars on the grounds that research programmes in ‘political economy’ and ‘sociology’ were at odds with the strategy of the Business School (Halford Citation2021). In keeping with the earliest use of the term, ‘cancelling’ signifies the potential damage that can be done to any brand in a precarious attention economy, not least ‘brand me’ (Hearn Citation2008). Some discussions of cancel culture link it to mental health issues such as ‘depression [and] anxiety’ (Spelman Citation2021), as if to dramatize how everyone is just a tweet away from the risk of public humiliation. The notion of the branded self may be aversive to the left. But the architecture of social media platforms incentivizes all of us to play a version of Foucault’s entrepreneurial self, even when we spend our time crafting witty tweets denouncing the imperatives of neoliberal selfhood. Yves Citton (Citation2021) questions the strategic effectiveness of much of the political identity work done within the ‘attention economy’, because of how the ritual of ‘[t]rumping the enemy’ (Seymour Citation2019a, p. 171) online fails to grasp the simple truism that ‘there is no such thing as bad publicity’ (Citton Citation2021, p. 774). Instead of a politics of ‘self-defeating’ righteousness’, he advocates ‘a radically post-critical stance: Never criticize what your opponent says (no matter how outrageous it may be!)’. ‘Choose your tensions – don’t let anybody entrap you in theirs’ (p. 809).

Thesis 6: ‘Cancel culture’ is a monstrous ideological abstraction but insisting it ‘doesn’t exist’ is a political dead end.

I do not like the term ‘cancel culture’ much, because of how it subsumes heterogenous experiences under a single weaponized heading that primarily benefits the far right. I also think the possibility of strong progressive alliances is undermined when people who self-identify as left amplify the mockery of left-liberal culture-war stereotypes, as if the only means of authenticating a radical left and socialist credo is through a lampooning of anything that might be branded as bourgeois or liberal. At the same time, I am not convinced by a refrain often heard on Twitter – that ‘cancel culture doesn’t exist’ and is nothing more than the fantasmatic creation of a fascistic right. It’s an entirely understandable response in one respect, because of the monstrous way the signifier is used. Yet the refrain can sometimes sound too much like the kind of argument you often hear on the right about the use of the term neoliberal – that ‘neoliberalism’ is a concept invented by paranoid leftists (Phelan Citation2021). By drawing the parallel, I do not mean to suggest that the concept of neoliberalism is as shaky as the folk concept of cancel culture. However, I think that any authentic radical democratic politics requires us to sometimes engage with concepts that we might think are incoherent or ideologically contaminated, as well as engage with (which is not the same thing as agreeing with or indulging) at least some political antagonists who might be labelled far right. The discourse theorist in me also wants to respond with the retort: ‘well, of course “cancel culture” exists: it exists as an object of discourse, much like everything else that creates social meaning’. To put the point less haughtily, the refrain that cancel culture doesn’t exist can suggest a left political culture that turns away from a mediatized social reality where signifiers like ‘cancel culture’ are being used to construct potent ideological antagonisms, as if the left can reassure itself that it has already found ‘an adequate answer’ (Gilroy Citation2019, p. 3) to the far right. But perhaps the main reason why I am averse to the refrain is that it can mean dismissing everything that is signified under the best faith interpretation of the term, even when we are clearly taking about a term where a good faith interpretation can feel impossible because of its bad faith uses. The figure of the moralizing, hypocritical or ‘do gooder’ leftist is unlikely to be an otherworldly figure in the life experiences of many people (Hall Citation1994), so it should not surprise us that denunciations of (left) cancel culture seem to resonate, including with those who would loathe the suggestion that they are simply recycling far right talking points. Saying that should be banal, but in the affective atmosphere of culture war, it can feel like a taboo observation that is open to being interpreted as a misguided (or worse ‘reactionary’) concession to the ‘other’ side. Maybe the left needs forms of media politics that could concede such points in a carefree way, not to indulge reactionary arguments or obscure real anti-democratic threats, but to enable a strategy that undermines the fantasmatic image of ‘the left’ that gives those arguments their power. Maybe we need to cultivate forms of left communication that are both ‘[un]burdened by the tone of earnestness’ (Vijay Prashad cited in Nowak Citation2016), yet wary of the ‘irony poisoning’ (O’Connell Citation2021) of public discourse in a social media age.

Thesis 7: The university is at the heart of the culture wars and we need to think more creatively and strategically about its political place in it.

When the right denounces ‘cancel culture’ and ‘wokeness’, this is routinely articulated as part of a chain of equivalences that turns signifiers like ‘critical theory’, ‘critical race theory’, ‘gender theory’, ‘cultural Marxism’, ‘the Frankfurt School’, ‘postmodernism’, ‘social constructionism’ into political weapons. The story is an old one (Hartman Citation2018). The origins of just about every contemporary malaise are attributed to the insidious influence of names like Adorno, Foucault, Derrida, Gramsci, Said, and Butler, and their idiot followers lower down the scholarly hierarchy. Publicizing these associations, as if to disclose long hidden secrets, has becomes its own niche outrage economy, in what is dramatized as a perverse form of public pedagogy. The university (followed by the publicly funded school) becomes the most pleasurable target of reactionary watchdogs, solidifying the impression that the critical humanities and social sciences have become the most dangerous threat to reason, enlightenment and freedom of thought and speech. This strategy has reaped political dividends in different countries including France and Denmark (Dawes Citation2020, ECREA Citation2021), and how those of us working in universities should respond to specific cases is not always clear. But perhaps the challenge facing a university that must defend itself against these attacks can be usefully framed as a choice between a moralized and radical democratic response to the political antagonisms that now texture public perceptions of the university’s work. To speak of a university of moralized antagonism is to invoke the cultural war figure of the ‘well credentialed radical’ (Adler-Bell Citation2022), a rather glib stereotype perhaps but also not an implausible stereotype particularly in the most elite universities. To adapt Sam Adler-Bell’s (Citation2022) analysis, it’s a world where ‘morally burdensome political norms and ideas’ can be taught in a manner that is presented as ‘self-evident’, as if any questioning of consecrated truths invites the reproach that is then potentially named and experienced as ‘cancelling’. In contrast, a radical democratic vision of the university would recognize that the fight to defend the best critical idea of the university must take place on a wider public stage where radically different ideas of what the university is for encounter each other, both outside and inside the neoliberal university. To the radical democrat, this fight cannot be just another restaging of war. Instead, it demands creative forms of collective intellectual praxis (Carrigan Citation2022) that can appeal to different constituencies, forge persuasive equivalences with workers elsewhere, and sometimes engage with people who would be more easily condemned and disparaged.

Postscript

The seven theses represented an attempt to counter the repressive effects of the so-called culture wars on our collective political imagination – to articulate a critical distance from a topic that feels already pre-determined and accounted for, as if writing about it will only add to the noise and exhaustion. I framed the argument as a critique of the sedimented antagonisms of the culture wars, but conceptualized from a theoretical perspective that, rather than renouncing images of political conflict, appealed to a radical democratic conception of political antagonism. The implications of the argument are not arcane. It suggests we will not transcend the media-driven, but nonetheless real, social conflicts signified under the heading of culture wars by appealing to a post-political horizon where the basic fact of political disagreement becomes the problem to be overcome. Nor will we transcend them by pining for absolute hegemonic victory or moral supremacy over an expansive catalogue of enemies. Instead, we need to reimagine questions of political and cultural difference within an emancipatory horizon that affirms the image of a common flawed humanity (Gilroy Citation2019, McGowan Citation2020), not to legitimize far right ideologies and discourses that annihilate the differences between left and right (or good and bad), but in the hope of enacting ‘a relation with others based on the reciprocal recognition of our common vulnerability and finitude’ (Mbembe Citation2019, p. 3). Making grand political proclamations in an academic essay is easy. But how to give meaningful collective expression to new forms of human, planetary and inter-species solidarity, in an ecology of culture war distraction, is not a trivial political challenge. It will necessitate a politics that can act and intervene on different scales, including the everyday media and cultural practices that sustain a culture war imaginary.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the reviewers and editors for their thoughtful comments. An early version of this paper was presented to the Centre for Media Research at the University of Ulster in March 2021; thanks to Robert Porter and his colleagues for inviting me to speak and engaging so wholeheartedly. A short version of the paper was presented at the International Communication Association conference in Paris in May 2022; thanks to Jayson Harsin for his feedback. Although very different articles in some respects, this article can be read as a sister piece to Phelan (Citation2022).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackerman, E., et al., 2020. A letter on justice and open debate. Harper’s Magazine. Available from: https://harpers.org/a-letter-on-justice-and-open-debate/.

- Adler-Bell, S., 2022. Unlearning the language of ‘wokeness’. Intelligencer, 10 June. Available from: https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2022/06/unlearning-the-language-of-wokeness.html.

- Allegretti, A., 2021. Boris Johnson’s conference speech: what he said and what he meant. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2021/oct/06/boris-johnsons-conference-speech-what-he-said-and-what-he-meant.

- Andrejevic, M., 2003. Reality TV: the work of being watched. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bromwich, J.E., 2018. Everyone is canceled. The New York Times. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/28/style/is-it-canceled.html.

- Brown, W., 2019. In the ruins of neoliberalism: the rise of antidemocratic politics in the west. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Caramanica, J., 2018. Into the wild with Kanye West. The New York Times. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/25/arts/music/kanye-west-ye-interview.html.

- Carrigan, M., 2022. Public scholarship in the platform university: social media and the challenge of populism. Globalisation, societies and education, 20, 193–207.

- Chadwick, A., 2013. The hybrid media system: politics and power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cheng, A., 2021. Putin slams ‘cancel culture’ and trans rights, calling teaching gender fluidity ‘crime against humanity’. Washington Post. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/10/22/putin-valdai-speech-trump-cancel-culture/.

- Citton, Y., 2021. Politics in tensions. counter-currents for a post-critical age. In: Daniel Benson, ed. Domination and emancipation: remaking critique. London: Rowman & Littlefield. E-book edition, 763–846.

- Clark, M.D., 2020. DRAG THEM: a brief etymology of so-called ‘cancel culture’. Communication and the public, 5 (3–4), 88–92.

- Connolly, W.E., 2005. Pluralism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- ContraPoints, 2020. Canceling. ContraPoints [YouTube]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjMPJVmXxV8.

- Corcuff, P., 2021. La grande confusion. Paris: Editions Textual.

- Couldry, N., 2003. Media rituals: a critical approach. London: Routledge.

- Crosstalk, 2021. Russia’s liberals in crisis. RT International. Available from: https://www.rt.com/shows/crosstalk/516344-russian-liberals-western-values/.

- Dawes, S., 2020. The Islamophobic witch-hunt of Islamo-leftists in France. OpenDemocracy. Available from: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/islamophobic-witch-hunt-islamo-leftists-france/.

- Dean, J., 2009. Democracy and other neoliberal fantasies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Denvir, D., 2021. ‘Cancel culture’ w/ Moira Weigel, Nikhil Pal Singh, Patrick Blanchfield. The Dig. Available from: https://www.thedigradio.com/podcast/cancel-culture-w-moira-weigel-nikhil-pal-singh-patrick-blanchfield/.

- Durand, M., 2020. ‘Ce qu’on appelle l’islamo-gauchisme fait des ravages’, dénonce Jean-Michel Blanquer. Europe 1. Available from: https://www.europe1.fr/politique/ce-quon-appelle-lislamo-gauchisme-fait-des-ravages-denonce-jean-michel-blanquer-4000366.

- ECREA, 2021. Public statement on situation in Denmark, ECREA. European Communication and Research Association. Available from: https://ecrea.eu/news/10713131.

- Feher, M. and Callison, W., 2019. Los Angeles review of books. Available from: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/movements-of-counter-speculation-a-conversation-with-michel-feher/.

- Felski, R., 2015. The limits of critique. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Figenschou, T.U. and Ihlebæk, K.A., 2019. Challenging journalistic authority. Journalism studies, 20 (9), 1221–1237. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1500868.

- Finlayson, A., 2021. Neoliberalism, the alt-right and the intellectual dark web. Theory, culture & society, 38 (6), 167–190.

- Finlayson, A., 2022. YouTube and political ideologies: technology, populism and rhetorical form. Political studies, 70 (1), 62–80.

- Fraser, N., 2017. From progressive neoliberalism to Trump—and beyond. American Affairs Journal. Available from: https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2017/11/progressive-neoliberalism-trump-beyond/.

- Gilroy, P., 2019. Agonistic belonging: the banality of good, the ‘alt right’ and the need for sympathy. Open cultural studies, 3 (1), 1–14.

- Glynos, J., 2021. Theorizing society post-Marxistly: an ecosystemic-materialist perspective. Hegemony, crisis, intervention: new perspectives on emancipatory & radical democratic discourses. University of Bremen. 25 September.

- Glynos, J. and Howarth, D., 2007. Logics of critical explanation in social and political theory. London: Routledge.

- Goldberg, D.T., 2021. The war on critical race theory. Boston Review. Available from: https://bostonreview.net/race-politics/david-theo-goldberg-war-critical-race-theory.

- Halford, S., 2021. BSA President writes to Leicester VC on the proposed closure of critical management studies and political economy. Available from: https://es.britsoc.co.uk/bsa-president-writes-to-leicester-vc-on-the-proposed-closure-of-critical-management-studies-and-political-economy/.

- Hall, S., 1994. Some ‘politically incorrect’ pathways through PC. In: S. Durant, ed. The war of the words: the political correctness debate, 164–183.

- Hall, S., 2019. Essential essays, volume 1: foundations of cultural studies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hansard, 2021. Search for ‘cancel culture’. Hansard: UK Parliament. Available from: http://localhost:54806/search/ContributionsendDate=2021-12-01&partial=False&searchTerm=%22cancel+culture%22&startDate=2016-12-01.

- Hartman, A., 2018. A war for the soul of America. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Hay, C., 2007. Why we hate politics. Cambridge: Polity.

- Hearn, A., 2008. 'Meat, mask, burden': probing the contours of the branded 'self'. Journal of consumer culture, 8 (2), 197–217.

- Hedges, C., 2021. The contradictions of ‘cancel culture’: Where elite liberalism goes to die. Salon. Available from: https://www.salon.com/2021/02/18/the-contradictions-of-cancel-culture-where-elite-liberalism-goes-to-die/.

- Hlavajova, M., 2020. Foreword. In: M. Hlavajova and S. Lütticken, eds. Deserting from the culture wars. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 9–21.

- Holm, N., 2020. Critical capital: cultural studies, the critical disposition and critical reading as elite practice. Cultural studies, 34 (1), 143–146.

- Hunter, J.D., 1991. Culture wars: the struggle to control the family, art, education, law, and politics in America. Reprint ed. Memphis, TN: Basic Books.

- Jongeneel, C., 2021. Baudet wil meldpunt cancel culture. Joop. Available from: https://joop.bnnvara.nl/opinies/baudet-wil-meldpunt-cancel-culture.

- Kanai, A. and Gill, R., 2021. Woke? Affect, neoliberalism, marginalised identities and consumer culture. New formations: a journal of culture/theory/politics, 102 (102), 10–27.

- Kaplan, L., 2021. My year of grief and cancellation. The New York Times. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/25/style/your-fave-is-problematic-tumblr.html.

- Know Your Meme, 2021. Cancel culture. Know Your Meme. Available from: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/cancel-culture.

- Krzyżanowski, M., 2020. Normalization and the discursive construction of ‘new’ norms and ‘new’ normality: discourse in the paradoxes of populism and neoliberalism. Social semiotics, 30 (4), 431–448.

- Laclau, E., 1990. New reflections on the revolution of our time. London: Verso.

- Laclau, E., 2004. Glimpsing the future. In: S. Critchley and O. Marchart, eds. Laclau: a critical reader. London: Routledge. Available from: https://www.routledge.com/Laclau-A-Critical-Reader/Critchley-Marchart/p/book/9780415238441.

- Laclau, E. and Mouffe, C., 2001. Hegemony and socialist strategy: towards a radical democratic politics. 2nd ed. London: Verso Books.

- Latour, B., 2004. Why has critique run out of steam? From matters of fact to matters of concern. Critical inquiry, 30, 225–248.

- Lewis, R., 2018. Broadcasting the reactionary right on YouTube. New York: Data & Society.

- Liu, C., 2021. Virtue hoarders. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lockwood, P., 2018. How do we write now? Tin House. Available from: https://tinhouse.com/how-do-we-write-now/.

- MacKenzie, I., 2021. What’s the point of critique, today? The Paris Institute. Available from: https://parisinstitute.org/depictions-article-whats-the-point-of-critique-today/.

- Maddox, J. and Creech, B., 2020. Interrogating LeftTube: ContraPoints and the possibilities of critical media praxis on YouTube. Television & new media, 22 (6), 595–615.

- Marchart, O., 2018. Thinking antagonism: political ontology after Laclau. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Mbembe, A., 2019. Necropolitics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- McAuley, J., 2021. Europe’s war on woke. Available from: https://www.thenation.com/article/world/woke-europe-structural-racism/.

- McGowan, T., 2020. Universality and identity politics. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Milmo, D., 2021. Twitter admits bias in algorithm for rightwing politicians and news outlets. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/oct/22/twitter-admits-bias-in-algorithm-for-rightwing-politicians-and-news-outlets.

- Mondon, A. and Winter, A., 2020. Reactionary democracy: How racism and the populist far right became mainstream. London: Verso.

- Montgomery, M., 2008. The discourse of the broadcast interview: A typology. Journalism studies, 9 (2), 260–277.

- Mouffe, C., 2005a. On the political. London: Routledge.

- Mouffe, C., 2005b. The ‘end of politics’ and the challenge of right-wing populism. In: F. Panizza, ed. Populism and the mirror of democracy. London: Verso.

- Mouffe, C., 2022. Towards a green democratic revolution: left populism and the power of affects. London: Verso Books.

- Nagle, A., 2017. Kill all Normies. Alresford: Zero Books.

- Ng, E., 2020. No grand pronouncements here … : reflections on cancel culture and digital media participation. Television & new media, 21 (6), 621–627.

- Ng, E., 2022. Cancel culture: a critical analysis. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. E-book edition.

- Nguyen, C.T., 2021. How Twitter gamifies communication. In: J. Lackey, ed. Applied epistemology. Oxford University Press, 410–436. Available from: https://philpapers.org/archive/NGUHTG.pdf.

- Norris, P., 2021. Cancel culture: myth or reality? Political studies, 71, 145–174.

- Nowak, M., 2016. The essentials of socialist writing: an interview with Vijay Prashad, Jacobin. Available from: https://jacobinmag.com/2016/12/socialist-writing-publishing-books-reading/.

- O’Connell, M., 2021. No one is talking about this by Patricia Lockwood review – life in the Twittersphere. The Guardian, 12 February. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/feb/12/no-one-is-talking-about-this-by-patricia-lockwood-review-life-in-the-twittersphere.

- Onishi, N., 2021. ‘Woke’ American ideas are a threat, French leaders say. The New York Times. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/09/world/europe/france-threat-american-universities.html.

- Phelan, S., 2019. Neoliberalism, the far right, and the disparaging of ‘social justice warriors’. Communication, culture & critique, 12 (4), 455–475.

- Phelan, S., 2021. What’s in a name? Political antagonism and critiquing ‘neoliberalism’. Journal of political ideologies, 27, 148–167.

- Phelan, S., 2022. Friends, enemies, and agonists: politics, morality and media in the COVID-19 conjuncture. Discourse & society, 33 (6), 744–757.

- Phillips, W., 2018. The oxygen of amplification: better practices for reporting on extremists, antagonists, and manipulators. Available from: https://datasociety.net/library/oxygen-of-amplification/.

- Phipps, A., 2020. Me, not you: the trouble with mainstream feminism. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Regan, A., 2021. Anger at University of Leicester’s ‘decolonised curriculum’ plans. BBC News. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-leicestershire-55860810.

- Roberts, J. and Wahl-Jorgensen, K., 2020. Breitbart’s attacks on mainstream media: victories, victimhood, and vilification. In: M. Boler and E. Davis, eds. Affective politics of digital media: propaganda by other means. Routledge, 170–185.

- Rueb, E.S. and Taylor, D.B., 2020. Obama on call-out culture: ‘that’s not activism’. The New York Times. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/31/us/politics/obama-woke-cancelculture.html.

- Sauer, P., 2022. Putin says west treating Russian culture like ‘cancelled’ JK Rowling. The Guardian, 25 March. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/25/putin-says-west-treating-russian-culture-like-cancelled-jk-rowling.

- Seymour, R., 2019a. The twittering machine. London: The Indigo Press.

- Seymour, R., 2019b. What harm did mobs ever do? Patreon. Available from: https://www.patreon.com/posts/what-harm-did-do-24809960.

- Shringarpure, B., 2021. A demanding relationship with history: a conversation with Priyamvada Gopal. Los Angeles Review of Books. Available from: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/a-demanding-relationship-with-history-a-conversation-with-priyamvada-gopal/.

- Singh, N.P., 1998. Culture/wars: recoding empire in an age of democracy. American quarterly, 50 (3), 471–522.

- Smith, B., 2020. Inside the revolts erupting in America’s big newsrooms. The New York Times. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/07/business/media/new-york-times-washington-post-protests.html.

- Sobande, F., Kanai, A., and Zeng, N., 2022. The hypervisibility and discourses of ‘wokeness’ in digital culture. Media, culture & society. doi:10.1177/01634437221117490.

- Spelman, B., 2021. The effects of cancel culture on mental health. Private Therapy Clinic. Available from: https://theprivatetherapyclinic.co.uk/blog/the-effects-cancel-culture-has-on-mental-health/.

- Tebaldi, C., 2021. Speaking post-truth to power. Review of education, pedagogy, and cultural studies, 43 (3), 205–225.

- Thomassen, L., 2019. Discourse and heterogeneity. In: T. Marttila, ed. Discourse, culture and organization: inquiries into relational structures of power. Cham: Springer Verlag, 43–62.

- Titley, G., 2020. Is free speech racist? Cambridge: Polity.

- Törnberg, P. and Uitermark, J., 2022. Tweeting ourselves to death: the cultural logic of digital capitalism. Media, culture & society, 44 (3), 574–590.

- Trudon, T., 2016. Say goodbye to ‘on fleek,’ ‘basic’ and ‘squad’ in 2016 and learn these 10 words instead. MTV News. Available from: http://www.mtv.com/news/2720889/teen-slang-2016/.

- Trump, D., 2020. Donald Trump Mount Rushmore speech transcript at 4th of July event. Available from: https://www.rev.com/blog/transcripts/donald-trump-speech-transcript-at-mount-rushmore-4th-of-july-event.

- University of Leicester, 2021. We are citizens of change. Available from: https://le.ac.uk/study/change.

- Varga, J., 2021. Woke wars: Boris to announce new measures to combat ‘cancel culture’ at universities. Express.co.uk. Available from: https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/1398338/boris-johnson-news-prime-minister-free-speech-champion-woke-cancel-culture-latest-ont.

- Waisbord, S., 2018. Why populism is troubling for democratic communication. Communication, culture and critique, 11 (1), 21–34.

- Waisbord, S., 2020. Mob censorship: online harassment of US journalists in times of digital hate and populism. Digital journalism, 8 (8), 1030–1046.

- Weigel, M., 2016. Political correctness: how the right invented a phantom enemy. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/30/political-correctness-how-the-right-invented-phantom-enemy-donald-trump.

- Young, T., 2021. About. The Daily Sceptic. Available from: https://dailysceptic.org/about/.