ABSTRACT

In this article, I will explore the role of memory in the context of homosexual liberation movements. I will do this through the lens of the queer press, which will serve as a doorway for the exploration of activist mnemonic labour. Activists undertake mnemonic labour to craft narratives that weave together historical oppression and resistance with hopes for a better future. These narratives are used to motivate and sustain activists in their present struggles. The queer press helps spread narratives across borders and creates shared memoryscapes for activism. My proposal is to view memoryscapes as schemata that inform activist mnemonic labour. On one hand, memoryscapes offer a shared purpose and direction for activists spread across different countries. On the other hand, they serve as arenas for mediation and comparison, linking distinct histories from diverse social groups and revealing their shared threads. This turns memory into a resource for building alliances across borders, and among different political and social groups. I will adopt this perspective to study two Argentinian homosexual liberation groups from the 1960s-70s: Nuestro Mundo and Frente de Liberación Homosexual (FLH). I will explore activist mnemonic labour on Nuestro Mundo’s bulletins and the FLH’s periodicals: Homosexuales and Somos. I will focus on two main aspects: (1) how activists adapt transnational narratives to the local context, and (2) how Argentinian activists weave narratives that blend historical oppression and resistance with visions of a different future.

Introduction: from mnemonic capacity to activist mnemonic labourFootnote1

Every year in November, LGBT+Footnote2 activists in Buenos Aires celebrate their Marcha del Orgullo (the Pride March). While Pride Marches in the Northern Hemisphere are typically organized around the anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall Riots, the March in Buenos Aires celebrates the founding of Nuestro Mundo in 1967. Nuestro Mundo was not only the first LGBT+ organization in Argentina and Latin America but also a co-founding group of the subsequent Frente de Liberación Homosexual (FLH) of Argentina, established in 1971.

In this manner, Argentinean activists appropriate a transnational commemorative form – the pride march – and infuse it with their distinct and local memory of activism (Rigney Citation2018). By commemorating past struggles and militant groups, LGBT+ activists construct narratives that intricately connect historical resistance and oppression with aspirations for a different future. These narratives play a pivotal role in sustaining activist mobilizations and struggles in the present. In this article, I explore the ability of activists to craft these mobilizing narratives by drawing on common semiotic forms and sharing a communal space for memory- and meaning-making. I will refer to this space as the ‘activist memoryscape’, following Ann Rigney (Citationunpublished mss).

In their seminal study, Elizabeth Armstrong and Suzanna Crage (Citation2006) illustrate how the commemoration of the Stonewall riots aimed to unite people annually for protest. They term the skill of activists to draw upon the past as a resource for mobilization and social change as ‘mnemonic capacity’. Stonewall was not the inaugural LGBT+ riot nor did it mark the inception of global LGBT+ liberation movements (see also Stryker Citation2017 [Citation2008] and Bacchetta Citation2002). Nevertheless, in the case of Stonewall activists managed to skillfully construct and disseminate a compelling narrative to sustain the momentum of homosexual liberation activism.

Social groups become carriers of memory when they succeed in crafting new narratives to encapsulate their historical experiences of oppression (Alexander Citation2012, p. 17). Activists weave historical depth and future perspective into shaping new political identities and narratives, tracing and building on memoryscapes for protest and struggle. I refer to this process as ‘activist mnemonic labour’.

Activists utilized various methods to create and disseminate these narratives. However, when public spaces are difficult for LGBT+ individuals to access due to discrimination and persecution, the queer press (Davis and Guy Citation2022) becomes an invaluable resource for crafting and circulating such narratives. Produced by and for LGBT+ people, the queer press aids its once fragmented and isolated readership in forming more cohesive communities. Moreover, the queer press is not solely characterized as ‘queer’ in relation to its creators and readers, but also due to its diverse materialities. It spans from do-it-yourself mimeographs crafted for covert underground distribution to well-established newsletters, bulletins, and magazines with wider circulation. These formats also reflect the diverse socio-political conditions for activism.

In their work, Armstrong and Crage (Citation2006, p. 731) employ the circulation of queer periodicals as a metric of mnemonic capacity. They argue that the ability to reproduce and circulate narratives of police raids and homosexual resistance allows activists to anchor the meanings and memory of such events. Hence, the queer press provides a fundamental lens through which to study activist mnemonic labour. However, this article redirects the focus from Armstrong’s and Crage’s mnemonic capacity to activist mnemonic labour. With this shift, the analysis moves from examining the (mechanical) capacity to re-produce narratives of events like Stonewall to exploring the primary (and more semiotic) capacity to produce such narratives.

In order to memoryscapeFootnote3 their struggles, activists need to draw on and adapt narrative schemata and cultural codes that are already in circulation to shape their new, defiant stories (Katriel Citation2021). For this reason, I consider the queer press as a vehicle not only for in-formation but primarily for forms that enable the creation of new narratives. Mnemonic labour is about forging and transforming codes, languages and narratives ‘beneath’, ‘behind’ or ‘before’ protest (Gillan Citation2020) and often in phases of the social movement’s latency, when people experiment with changes in the systems of meaning to oppose the dominant social codes (Melucci Citation1985, p. 800). Viewed through the lens of cultural memory studies (Rigney Citation2016), this means shifting our analytical focus away from the clamour of protests to the ‘unspectacular work’ (McKinney Citation2020) of reading, adapting, and crafting narratives and texts. This shift helps overcome the ‘myopia of the visible’ that frequently characterizes the realm of social movement studies (Melucci Citation1989, p. 44).

The analysis will focus on the queer press production of Argentinian groups Nuestro Mundo and FLH, spanning from 1967 to 1976. These groups emerged during the 1966–1973 military dictatorship and navigated through shifts in power, from democratic elections to the rise of the last military dictatorship (1976–1983). In nearly a decade, Nuestro Mundo and FLH produced bulletins and declarations, including issues of periodicals such as Homosexuales (1973) and Somos (1973 to 1976). This cultural analysis unveils how the queer press facilitated cross-border connections among activists: by translating and adapting transnational narratives, Argentinian activists crafted new stories to sustain their own struggle. The structure of the article includes a preliminary discussion on the queer press as an activist network and citational field, and an exploration of the concept of memoryscape. This more theoretical part prepares the exploration of Argentinian activist mnemonic labour through the analysis of Nuestro Mundo’s and FLH’s print production.

Retweeting in the 1970s: activist communicative networks and citational fields

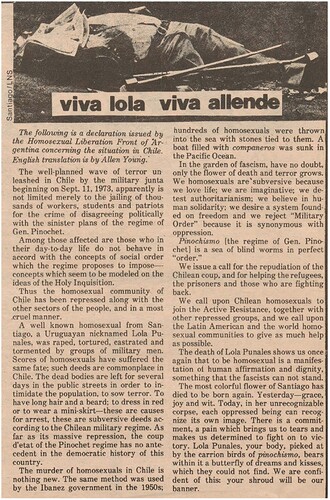

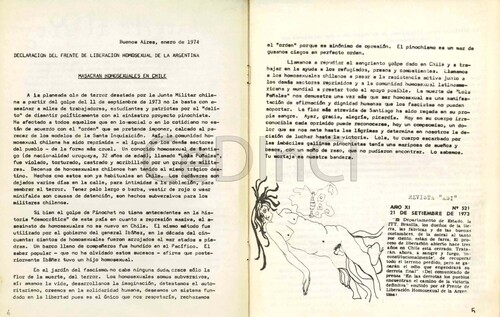

In the summer of 1974, the US periodicals Fag Rag and Gay Sunshine jointly published a special issue to mark the fifth anniversary of Stonewall, providing ‘the largest gay liberation collection’ since the riots (Fag Rag and Gay Sunshine Citation1974). Included in this collection was a piece authored by the FLH, titled ‘Viva Lola viva Allende’ (), addressing the aftermath of Pinochet’s coup d’état in Chile. Originally published in the second issue of Somos (FLH Citation1974a), the FLH’s text urged global homosexual communities to support Chilean homosexuals in their ‘Active Resistance’ ().

Figure 1. Fag Rag/Gay Sunshine, summer 1974, ‘Viva Lola Viva Allende’, translation of ‘Masacran homosexuales en Chile’ – Courtesy of IHLIA (Amsterdam). Reproduced with permission of Michael Bronski.

Figure 2. Somos, issue n° 2, the text ‘Masacran homosexuales en Chile’ – Courtesy of AméricaLee, CeDInCI (Buenos Aires).

A year later, the Canadian gay liberation journal The Body Politic republished another FLH-written text titled ‘Letter from Argentina’ (FLH Citation1975a). In reality, this was a republished letter from Australia’s Gay Liberation press, originally directed at gay groups in Australia. Accompanying the letter was a translation of a Chilean newspaper article reporting on an anti-gay squad in Santiago. This Chilean report also appeared in the fifth issue of Somos (FLH Citation1974d) and thus travelled alongside the FLH’s letter to Australia, subsequently reaching Canada.

These instances showcase the journey of transnational activist material, as it moves across various nations through translations and reprints. In his comprehensive study, Patricio Simonetto (Citation2020, p. 19) underscores the international networks that the FLH weaves with gay and feminist groups. Information republished and spread by the queer press bolster social movements (McKinney Citation2020) and forms connections among readers on local, national, and transnational scales, akin to the contemporary sharing of information on social media. The circulation of the queer press yields two effects: it creates communicative networks and constructs shared citational fields for activism. These networks amplify suppressed voices within societies, projecting them onto an international stage that can subsequently influence domestic contexts (Keck and Sikkink Citation1998, p. 3). This role proved crucial in extending support to LGBT+ individuals living under dictatorial regimes. Activist material travelled globally, often through postal services or alongside migrants, refugees, exiles, and those crossing borders for various reasons (Szulc Citation2017).Footnote4

In the letter to Australian activists, the FLH emphasized the transnational nature of the homosexual liberation struggle:

We don’t pretend to forming a gay international, but it is important to keep in contact. Every gay liberation group is connected with its own country – we never forget ours – but we know that in a way we all have a fatherland only in the abstract, since an individual who is denied the right to love and live freely needs to hold onto something mystical as a motivation to keep living rather than becoming a human scarecrow.

Memoryscaping liberation

Building on Arjun Appadurai’s concepts (Citation1996), Kendall Phillips and Michelle Reyes introduced the term ‘memoryscape’ to depict a global ‘complex landscape upon which memory and memory practices move, come into contact, are contested by and contest other forms of remembrance’ (Phillips and Reyes Citation2011, p. 13). This metaphor encapsulates the notion of memories that are mobilized and interconnected through the circulation of media and people across different locations and periods.

The concept of memoryscape has undergone diverse interpretations and has been particularly employed to examine connections between physical sites (e.g. Árvay and Foote Citation2019). Ann Rigney has employed the concept of memoryscape to explore how activists construct narratives that connect historical experiences of oppression and struggles with aspirations for the future to drive social change, what she calls the memory-activism nexus (Rigney Citation2018, Rigney Citationunpublished manuscript). Rigney’s interpretation resonates with the work of Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui on the use of memory in the peasant movements in Bolivia (Cusicanqui Citation1984). Cusicanqui analyses ‘horizons of memory’ as narrative articulations of memories of the far and near past.

Memoryscapes are thus multitemporal: they connect past and desired futures with collective struggles in the present; yet, they are also perspectival, multiscalar and relational. Memoryscapes assumes different configurations according to the local cultural, geographical, political and historical positions and dispositions of viewers. This means that activists share a common transnational memoryscape for a cause, but they configure it differently, according to their specific perspective. The multiscalarity of memoryscapes is the result of the ability of activists to trace networks on multiple scales, from the local to the transnational. Finally, memoryscapes are essentially relational, a crucial aspect for social groups. When a group of friends collectively witnesses a significant landscape and converses about it, each member might highlight distinct features. This creates diverse narratives, turning the landscape into a shared space for collective meaning-making and discourse production. Memoryscapes operate similarly. Through the circulation and mediation of the queer press, activist groups direct collective attentionFootnote5 to historical experience and future aspirations, nurturing shared significance and shaping action and intention in the present. However, each individual or subgroup may assign diverse meanings, according to their historical background, geographical and political positions.

In this perspective, memoryscapes are spaces where activists can shape, interlink and share in (mediated) dialogue their narratives and discourses. This turns memoryscapes into communal spaces for constructing meaning, with each participant contributing diverse narratives and discourses. In contrast to the dominant paradigm in memory studies, which tends to emphasize explicit content and commemorative collective memory (Erll Citation2022), this perspective suggests a more nuanced interpretation of memoryscapes. Memoryscapes should be envisaged not merely as fixed narratives or predefined landmarks, but as adaptable schematic forms that social and activist groups invest with meanings and narratives, in a way that is specific to local contexts, political sensitivities and social and historical background.

Therefore, activists adopt and adapt the underlying schematic forms that embed specific narratives of events, which circulate in the queer press, to create fresh narratives, which hold greater local relevance. This phenomenon is exemplified by the context of Pride marches in Buenos Aires, which I mentioned earlier. In that case, the focus is shifted from the commemoration of the Stonewall riots to the celebration of the founding of Nuestro Mundo. Hence, an activist commemorative form that circulates transnationally is infused with a distinct narrative local content.

In my use of the expression ‘schemata’, I draw on narratological models that conceptualize ‘stories’ as multilayered realms of meaning. From this standpoint, narratives consist of both a surface and a deeper level. In his narrative approach to national memories, located in a ‘narrative turn’ in the humanities, James Wertsch calls these two levels ‘specific narratives’ and ‘schematic narrative templates’, or ‘schemata’ (Wertsch Citation2021). Wertsch argues that social groups, before being united by specific narratives about events, are ‘bound together by schematic forms extracted out of the countless narratives’ circulating in the social space (Wertsch Citation2021, p. 146).

In narratological approaches, schemata are cognitive knowledge representations that guide us in the process of understanding the world and acting in it. Umberto Eco (Citation1984, p. 73; see also Salerno Citation2021) argues that different theories postulate a schematic level of analysis, focused on a ‘deep’ narrative level. For example, Vladimir Propp’s analysis of fairy tales (Citation1968 [Citation1928]) was one of the first to show how schemata can travel, generating new narrations and gathering together groups of readers and texts. Propp proved that different fairy tales – or what Wertsch would call ‘specific narratives’ – are actually different instantiations of the same underpinning schematic form in which we have similar emplotments, schematic storylines, character archetypes and transformations – what Wertsch calls ‘schemata’.

It is with the same logic that I look at memoryscapes for queer liberation as common spaces for activist meaning-making. Texts travel and schematic forms and narrative are extracted and adapted by activists, giving rise to other narratives that are different in content but underpinned by similar underlying schemata. In this sense, memoryscapes bind activists together not simply because they remember, narrate and reproduce the same specific events, but because they share the same schematic forms, that is, a common way of looking at and shaping the past, present and future – what Erll (Citation2022) recently called ‘implicit memory’.

This idea is already present in Appadurai’s original framework. By disseminating information, the queer press offers ‘a series of elements (such as characters, plots, and textual forms) out of which scripts can be formed of imagined lives, their own as well as those of others living in other places’ (Appadurai Citation1996, p. 35). The queer press allows for the connection of different stories and the circulation and adaptation of schemata from one domain to another, from one geopolitical context to another, from one social group to another and from one cause to another. This circulation provides activists spread globally with ‘rudimentary plot structures’ (Erll Citation2011, p. 17) to be filled with new stories for activism.

In the aforementioned letter to Australian gay activists, we read that ‘an individual who is denied the right to love and live freely needs to hold onto something mystical as a motivation to keep living’. These words echo Kenneth Burke’s idea – one of the theorists who worked on ‘schematic forms’ that underpin texts – about narratives being ‘equipment for living’. In what follows, we will see how exactly Nuestro Mundo and the FLH shaped narratives with their mnemonic labour, building on activist memoryscapes as ‘equipment for living’ and struggling.

From Nuestro Mundo to the FLH: discovering the past as a resource for liberation

Nuestro Mundo was created in 1967 by the postal trade unionist and communist militant Héctor Anabitarte (Encarnación Citation2016). Anabitarte started to organize informal meetings with comrades marginalized by left-wing organizations due to their sexual orientation. Their goal was to eliminate the edictos policiales [police edicts] that enabled authorities to arrest LGBT+ individuals without judicial oversight for ‘offenses against public morality’ (Insausti Citation2015).

Initially, the group had no contact with activist networks abroad (Modarelli and Rapisardi Citation2019 [Citation2001], p. 160) but followed local dynamics. In 1966, the military dictatorship banned political parties and the participation of civilians in politics: Trotskyists, Maoists, Christian Third Worldists, Peronists and feminists all found themselves operating in the shadows (Ben and Insausti Citation2017, p. 303). Nuestro Mundo, alongside subsequent LGBT+ groups within the FLH, adopted these models to resist repression.

From 1968 to 1970, Nuestro Mundo issued four bulletins but just one survived (Nuestro Mundo Citation1970). It is composed of five pages with selection of excerpts from mainstream media in Argentina and abroad, primarily focused on ‘scientific’ content. The voices of homosexual people are scarcely present in the bulletin, mainly appearing in the opening editorial, a brief reportage in the middle, and a closing remark.

The bulletin promoted the scientific discourse that depicted homosexuality as a disease. For example, we read that ‘homosexuals would be as unworthy to be punished for their conditions as people with tuberculosis or cancer’. Thus, the use of a pill to suppress sexual urges is described as a good solution; elsewhere, an interviewee described his homosexuality as a natural predisposition for unhappiness. These texts are presented as accurate representations of homosexuality.

Insausti (Citation2019) interprets the self-loathing approach in the publication as a strategic choice rather than a genuine belief among homosexual activists. Public opinion oscillated between perceiving homosexuality as a crime or a disease. By supporting the disease perspective, activists aimed to avoid imprisonment, asking for medical treatment and social pity.

Whether the activists were sincere or not, the public representation of homosexuality as a disease translates into a real discursive impairment: the homosexual as a speaking subject needs to leave room for the homosexual as an object of scientific discourse and social pity. To bolster the credibility of this self-representation as a ‘sick’ subject, activists delegate mainstream media and science to speak on behalf of homosexuals and mediate their voices. Journalists and scientists have to perform those speech acts – to persuade, to claim and to ask – which a self-represented ‘sick’ subject may appear incapable of doing on its own, especially in the eyes of the public opinion.

This discursive dynamic affects the homosexual activists’ capacity to speak out and does not lend itself to the idea that homosexuals are a social or political group and a carrier of memory. Consequently, a memoryscape of liberation is not even conceivable.

However, less than two years later, the very first bulletin of the FLH presented a quite different position: the idea that homosexuals do indeed have a history of oppression and resistance. As described in the ‘aclaración’ that opens the bulletin, homosexuals have to free themselves not from the disease of homosexuality but from social oppression:

In August 1971, somewhere in the city of Buenos Aires, a group of homosexuals of both sexes decided to form the Homosexual Liberation Front. The movement recognizes as [its] antecedents the analogous organizations of Europe and the United States, with some of whom it maintains fraternal relations, and the publication Nuestro Mundo. The source of doctrinal inspiration for the Front is its integration with the national and social liberation movements that operate in the country. […] The movement has adopted as its emblem the pink triangle used in Nazi concentration camps to identify homosexual prisoners. This symbol has been chosen because it constitutes a synthesis of the ideals at stake: human liberation in the struggle against a classist, authoritarian, repressive society. (FLH Citation1972)

The FLH established in its printed material connections between texts, stories, and the causes of local homosexual and non-homosexual militant groups, at local and transnational level. This effort in textual connection empowered Argentinean activists to draw from and be inspired by memories of other social groups, countries, and histories, with the goal of shaping and sharing memoryscapes of liberation for the LGBT+ community in Argentina.

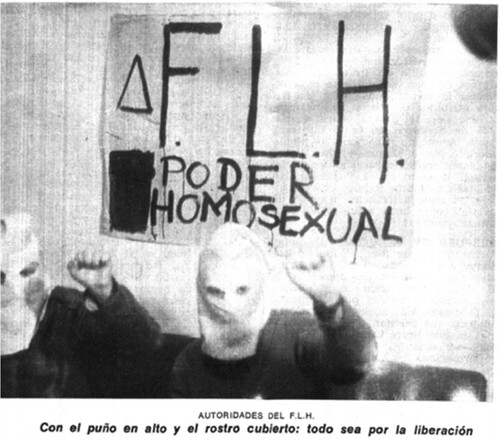

Joining FLH, various activist groups started to use memory as a resource for positive, militant LGBT+ narratives and identities. This shift is evident in an image () that circulated in mainstream press, where FLH adopts symbols from different histories and groups, like the triangle, raised fist and the expression ‘Poder Homosexual’, echoing the ‘Black Power’ slogan.

Figure 3. Magazine Panorama, August 24, 1972, p. 34 – Courtesy of AméricaLee, CeDInCI (Buenos Aires).

Activists began incorporating and adapting insights from past and ongoing struggles of diverse origins into their actions and rhetoric. This transnational material not only influenced their discourse and protests but also provided schemata that could be adapted to the Argentinian context.

This allowed activists to forge new stories in support of the homosexual liberation movement in Argentina and opened up new possibilities for political identification. In particular, in 1972, access to material from Black anti-racist activism offered new perspectives on memory as a resource for driving social change.

Homosexuals as oppressed people and revolutionaries: envisioning the future from the past

Black anti-racist material reached Argentina through Juan José Hernández, who visited New York in the early 1970s. Activists were most influenced by the ‘Letter of Huey P. Newton, Black Panther Party Minister of Defence, to the revolutionary brothers and sisters on the homosexual liberation and woman liberation movements’ (Newton Citation1970; see also Ben and Insausti Citation2017, pp. 309–310; Modarelli and Rapisardi Citation2019 [Citation2001], pp. 161–162), translated and circulated by Nuestro Mundo (Nuestro Mundo Citation1972). Nuestro Mundo added a statement to the translated text, advocating for the release of homosexuals from Buenos Aires prison and the abolition of police edicts. Moreover, the group expressed solidarity with all victims of the dictatorial government. How and why did Nuestro Mundo activists translate and circulate Newton’s letter and link it to their own causes in Argentina? To answer, we must reconstruct the history, content, and circulation of Newton’s letter.

Huey Newton was co-founders, with Bob Seale, of the Black Panthers and were both in prison at the end of the 1960s. A few days after his release in August 1970, Newton published the letter in the movement’s periodical, The Black Panther, in support of the gay and women’s liberation movements (Newton Citation1970). In the letter, Newton compared white people’s racism against Black and poor people with Black people’s violence against gay people and women; he furthermore criticized the use of words like ‘faggot’ to attack ‘enemies of the people’ like Nixon. He argued that homosexuals and women are ‘the most oppressed people’ in society and therefore potentially the ‘most revolutionary’ of all. For this reason, Newton supported an alliance between the Black Panther Party and the homosexual and women’s liberation movements.

A complete analysis of the letter’s genesis is beyond the aim of this article, but we can say that viewing police as a common enemy and prisons as shared sites of oppression brought movements closer (Leighton Citation2019). Edmund White (Citation1993) suggests that Newton’s letter resulted from dialogue and tension between the French homosexual writer Jean Genet and the Panthers, possibly explaining Newton’s critique of the derogatory references to homosexuality used to attack Nixon. In 1970, Genet toured the USA for the Panthers and published two texts in The Black Panther. In the first, he emphasized his privileged white status and presents Black movements as key ‘carriers of revolutionary thought and actions’; he also invited Black militants ‘to use new vocabulary’ (Genet Citation1970a). In the second, Genet supported a coalition between Black movements and the Left(s), tracing an analogy between Seale’s detention and Alfred Dreyfus’s case (Genet Citation1970b). Drawing such equivalences between the European memory of anti-Semitism and anti-Black racism in the USA, Genet argues that a coalition between the Black Panthers and comparable ‘White movements’ is necessary.

Newton’s letter aligns conceptually and rhetorically with Genet’s texts. Like Genet, Newton recognizes that he is a potential oppressor of women and gay people and continues the chains of equivalences started by Genet. If Genet finds similarities in Jewish and Black oppression, Newton likens Black oppression to that of women and homosexuals. Genet’s and Newton’s writings embody a concept described by Michael Rothberg (Citation2009) as multidirectional configuration. In multidirectional memories, social groups note analogous narrative roles across varied historical accounts that start mapping onto each other. Viewing shared oppressed nature as a ‘deep’ narrative similarity ties and connect Black, Jewish, homosexual and women. This turns historical memory into a medium for building alliances and forging new common identities across diverse social groups. Activists begin to borrow from various groups’ cultural repertoires and identify with the forward-looking figure of the revolutionary.

Through these republications in the activist and queer press in the Americas and Europe, homosexual liberation militants linked gay and Black oppression, reshaping their identity as ‘most oppressed’ and ‘most revolutionary’. By expanding comparisons, homosexual militants connected anti-colonialist, anti-racist and sexual liberation causes to one another, enabling cross references (e.g. ‘Black Power’, which turns into ‘Poder Homosexual’ in ). However, these processes remain context-sensitive, guiding activist mnemonic labour based on the specific social, political, and historical contexts.

In France, for instance, Newton’s letter appeared in the Maoist magazine Tout! via Guy Hocquenghem’s initiative, who later founded the Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire (FHAR). Hocquenghem (Citation1977, p. 145) said that Newton’s ‘association of the words “homosexuality” and “revolution”’ had a demystifying function and persuaded him to adopt a revolutionary attitude. In Italy, the letter is cited in the text ‘Ai compagni rivoluzionari’, authored by Luciano Massimo Consoli (Consoli Citation1971, ‘To the revolutionary comrades’) and published in the inaugural issue of the Homosexual Italian Revolutionary Front’s periodical, FUORI!. Consoli observed that numerous European magazines had published Huey’s letter, and it had inspired and legitimized the homosexual liberation movements internationally. Consoli addresses Italian homosexual militants as ‘revolutionary comrades’, employing Newton’s rhetorical strategies and political identifications. This further displays Newton’s cultural impact on the movement.

Argentina is no exception. The letter reshaped Nuestro Mundo’s perspective, reframing the struggle and fostering coalitions. Moreover, it was republished in Homosexuales, FLH’s one-time periodical. Within this four-page publication, FLH envisioned a liberated future and the path to achieve it, building on the two available identifications for 1970s homosexual activists: that of past and present oppressed subjects and, consequently, revolutionaries aiming for a liberated future.

Homosexuales: building activist memoryscapes

The FLH produced the periodical Homosexuales in July 1973 (FLH Citation1973a). At that moment, the fall of the military dictatorship and the victory of the presidential candidate Héctor Cámpora in the democratic elections radically changed the political situation. After a long exile, Perón himself returned to Argentina in June 1973.

At this point, the FLH was composed of different groups, covering a very large spectrum of social classes and ideologies: a group of intellectuals called Profesionales; Eros, a group composed of left-wing militant students; the lesbian group Safo; the anarchists of Bandera negra; and Alborada, a group created to spread more general ‘awareness’ of homosexuality. In addition, three religious groups joined: a Catholic group, one inspired by the Theology of Liberation movement and Third Worldism, and a group of Christian Protestants.

Homosexuales was edited and printed as a ‘proper’ newspaper and counted fifteen items. The FLH aimed to benefit from the new democratic conditions to obtain public visibility. If we look at the front page, we can see that more than half is taken up by two letters: at the top, there is a ‘Carta abierta a todos los homosexuales’ [Open letter to all homosexuals], in which the FLH lists the reasons for its constitution; at the centre of the page, Newton’s letter has been reproduced. The other two items that fill the front page are a petition for the abolition of anti-homosexual edicts addressed to the government and the ‘Puntos básicos del acuerdo del Frente de Liberación Homosexual’ [Basic points of agreement of the Homosexual Liberation Front].

If Nuestro Mundo’s bulletin sidelined the voices and viewpoints of homosexual people, Homosexuales adopted a ‘homosexual identity’. Activists use the first person plural and every text is signed by activist groups or ‘the Front’. This reveals a capacity to also use discursive genres that mark the author’s identity and point of view: ‘declarations’, ‘letters’ and ‘petitions’. The FLH addresses ‘all homosexuals’, turning them into a social group and movement, and invites them to acknowledge their oppression and assume a revolutionary, political identity.

Drawing on the conceptualization of memoryscape as a schema, we can see how Homosexuales offers its readers visions of the past, present and future that support homosexuals’ new identity as an oppressed and revolutionary social group; this allows activists to adapt homosexual transnational struggles to the Argentinian local context.

Three articles point to the far past to explain the mechanisms of oppression: ‘Homosexualid historica. Mesopotamia y Judea’ [Historical homosexuality. Mesopotamia and Judaea], ‘Homosexualidad masculina y machismo’ [Male homosexuality and machismo] and a short quotation from the Kinsey report, ‘Del informe Kinsey’. These texts identify the patriarchal Judaeo-Christian civilization as the origin of homosexual oppression and describe how homosexuality was permitted in pre-Christian civilizations and even considered a sign of social distinction. The brief reference to the Kinsey report supported the idea of homosexuality as an important part of human history and the expression of natural faculties of the ‘human animal’.

Conversely, the article ‘La legislación antihomosexual en la Argentina’ [Anti-homosexual legislation in Argentina] – published on the last page alongside the text ‘Los oprimidos no se convertirán en opresores’ [The oppressed shall not become oppressors] – points in another direction. It parallels ‘discriminatory legislation against Black people’ during Spanish colonization with twentieth-century anti-homosexual police edicts. By linking anti-Black and colonial racism in Argentina and anti-homosexual laws, the FLH urges solidarity between anti-racist movements and homosexual movements. ‘The oppressed shall not become oppressors’ is signed by the ‘’New York-based group of Black and Latino homosexuals’, Third World Gay Revolution (TWGR) and sourced from Come out!Footnote6 issue five (Come Out Citation1970), where it was published in a special section that included Newton’s letter and texts by Néstor Latrónico and Martha Ferro.Footnote7 The TWGR stressed the triple oppression of Black and Latino homosexuals as working-class, non-white and homosexual people. They accused the so-called ‘revolutionaries’ of turning into oppressors when they attacked women and gays, thus echoing Newton’s line of reasoning. Published next to each other, ‘Anti-homosexual legislation in Argentina’ and ‘The oppressed shall not become oppressors’ connect anti-gay, anti-Black and anti-Latino racism, drawing on the historical memory of multiple sites and temporalities (i.e. Spanish colonization, the American North and South and Africa) to build acts of solidarity and political coalitions.

A third group of texts points at the near past and present and, in particular, the political context of 1973, with the return of democracy and Peronism and the general idea of a ‘national liberation’ from imperialist and capitalist forces. In a declaration and press release, militants envision sexual liberation as part of the popular struggle for national liberation. As Ben and Insausti (Citation2017) have argued, in 1973 the discourse on national and social liberation heralded by Peronism was a promising point of entry into a broader political alliance for the FLH.

Homosexuales vividly demonstrates how queer periodicals offered a diverse array of narratives, which readers may engage with and connect. These narratives span from the ancient civilizations of Europe, Asia, Africa and the pre-Columbian Americas and extend to the recent political history of Argentina. This weaving of historical levels and multiple geographical scales through textual contiguity facilitates the emergence of a shared memoryscape from the printed pages. This shared space becomes a fertile ground for collective memory and identity formation and interpretation, wherein disparate and profoundly diverse social groups can intersect.

I argue that viewing memoryscapes as schematic forms for meaning-making could explain the co-existence of differing and even contrasting ideological positions in Homosexuales and the FLH. For example, Homosexuales published articles with anti-Christian sentiments alongside a declaration from Catholic homosexuals defining themselves as ‘members of Christ’s body’, all on the same page. I argue that the archetypical roles of ‘oppressed’ and ‘revolutionary’ provided each activist group in the Front with a common identification to map their different histories onto each other. This allowed diverse groups to create analogies among their different stories, which helped overarch ideological and social differences and form alliances across diverse groups. Although divergences emerge in this dynamic, they always rely on a common narrative schema and identification of a common antagonist.

Somos: shifting memoryscapes

From December 1973 to January 1976, the FLH published eight issues of the periodical Somos: issues 1–6 were composed, on average, of 40 pages (FLH Citation1973b; FLH Citation1974a; FLH Citation1974b; FLH Citation1974c; FLH Citation1974d; FLH Citation1975b), whereas the last two issues were again published in a bulletin format (FLH Citation1975c and FLH Citation1976), owing to the material difficulty of publishing under the threat of growing military repression.

As emphasized by the title – Somos (We are) – the focus of the publication was the discourse on identity.Footnote8 After the enthusiasm for the return to democracy, the country was heading towards another, more violent military dictatorship. If Homosexuales also addressed non-homosexual readers, Somos presented a dialogue that was internal to the movement, documenting the return to underground publishing. In particular, Somos showed that any ambition to build alliances with Peronist forces was gone. The political strategy’s failure prompted shifts in how FLH chose past events in Somos. For example, the fifth issue commemorated the twentieth anniversary of one of the largest raids against homosexual people in Buenos Aires, which happened in 1954 under Perón’s government. This reflects FLH’s disappointment with Peronism, which was also emphasised in the press release for Perón’s death (issue four, August–September 1974) (FLH Citation1974c). While honouring him, the FLH recalled the repression of homosexuality during his last year in power (1973–1974). The conceptualization of memoryscapes as schemata allows us to trace, in the recollection of events that position Peronism as an oppressive force, a reorganization of memories according to the mutable political contexts and position of activists. What changes is, however, the position of discrete elements and not the underlying schema used to narrate the past: if in 1972–1973, Peronism appeared to activists as a promise of future liberation, by 1974, it had become a political disappointment and part of an oppressive past.

Somos features diverse texts: fiction, poetry, theory, translated documents from other homosexual groups, letters to FLH from organizations abroad, and news from Europe and the USA. Two key themes emerge across the issues: first, ‘the change in the social structure’ requires ‘a change in our interiority’ (see also FLH's manisfesto Sexo y Revolución, FLH Citation1974e); second, ‘los homosexuales somos hermosos’ – homosexuals are beautiful. This expression, which is the title of the opening text of the third issue (FLH Citation1974b), reverses prior self-loathing. It shows that the FLH was also adapting in its own terms metaphors and perspectives that were circulating transnationally. In particular, the coming-out-of-the-closet metaphor would be used in Argentina as a schema for sustaining homosexual liberation, even in the face of cultural, social, and political differences with the USA.

The role of the coming-out-of-the-closet metaphor for the memoryscaping of liberation

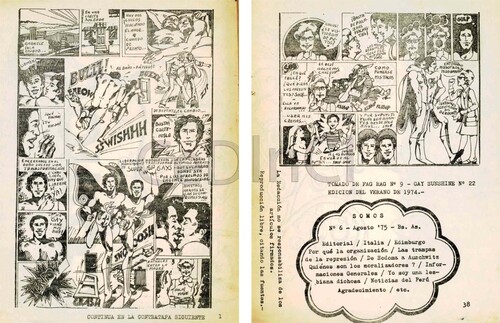

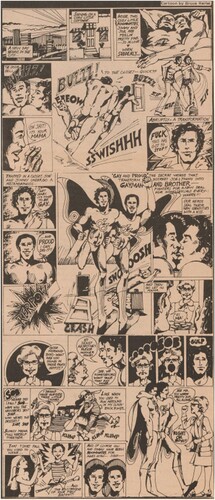

Translations is especially enlightening for exploring activists’ mnemonic labour. In particular, the translation and adaptation of a comic for Somos issue number 6 (August 1975, FLH Citation1975b) demonstrates how ‘deep’ narrative schemata travelled and are adapted across different cultural and linguistic contexts. The comic () opened and closed the number, thus framing the issue. It tells the story of two gay men who are surprised by one’s mother while lying in bed. After abandoning the idea of hiding in the toilet, the two men transform themselves into superheroes and decide to declare their homosexuality to the woman in support of the collective struggle for homosexual liberation.

Figure 4. Somos, issue n° 6: the translation of the US comic – Courtesy of AméricaLee, CeDInCI (Buenos Aires).

The comic was taken from the aforementioned Fag Rag and Gay Sunshine commemorative issue, which was published for the fifth anniversary of the Stonewall riots (). summarizes key divergences between the North American and Argentinian comic versions due to translation choices (literal translation in square brackets).

Figure 5. Fag Rag/Gay Sunshine, summer 1974. The original comic – Courtesy of IHLIA (Amsterdam). Reproduced with permission of Michael Bronski.

Table 1. The main differences between the version of Fag Rag/Gay Sunshine and that published in Somos.

The original comic builds on the coming out of the closet metaphor, which shapes the homosexual liberation discourse in the USA. The metaphor visualizes the transition of homosexuals from hiding to visibility, providing a general ‘image–schema structure’ (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1980) for producing and connecting different stories across different domains (Plummer Citation1995). Both the ‘closet’ and the ‘out-of-the-closet’ are turned into topological and conceptual spaces that can be invested with different specific narratives. Drawing from Propp’s approach, Plummer analyzed coming-out stories as turning negative experiences into positive identity and private pain into political or therapeutic language (Plummer Citation1995, p. 50). According to Appadurai, metaphors and scripts of the ‘coming-out-of-the-closet’ type ‘help to constitute narratives of the Other and protonarratives of possible lives, fantasies that could become prolegomena to the desire for acquisition and movement’ (Appadurai Citation1996, p. 35). The ‘coming out of the closet’ metaphor allows activists and homosexual readers to reshape their different stories, as individuals and collectives, inscribing them within a similar narrative arc that spans from a past of suffering to liberation. In the perspective of this research, the schema offered by the ‘coming out of the closet’ metaphor is part of the LGBT+ movements’ memoryscape, since it allows to reshape and relate different specific narratives to each other through a common and recognizable form.

However, upon reaching Argentina through the comic, the Spanish calque ‘salir del armario’ (literal ‘coming out of the closet’) was not yet available in the 1970s. Argentinian activists translated ‘closet’ as ‘baño’ (toilet), adapting the comic to local practices and linking it with Somos texts. For example, in the fifth issue, the text ‘Los baños publicos son nuestros salones de fiesta’ (Public toilets are our party room) compares public toilets to the first Christians’ catacombs and describes them as a space of oppression, resistance and pleasure for homosexuals. The second issue includes a poem by Nestor Perlongher, ‘Defensa de los homosexuales de Tenochtitlan y Tlatlexlolco’ (Defence of the homosexuals of Tenochtitlan and Tlatlexlolco), set in an imaginary Mexican, pre-Columbian Aztec empire, where the toilet is the place where homosexuals ‘caress each other’ as they wait for a future in which ‘the right to caress will be recognized’. The space of the public toilet is infused with past temporalities through analogies with other stories of oppression. It is also a space of both sexual pleasure and political resistance. Comparing it to imaginary, precolonial times or the catacombs of the first Christians makes the homosexual reader see the persistence of oppression and the possibility of future emancipation.

If in the translation of closet into ‘baño’/toilet we lose track of the original metaphor, this translation choice does not change the ‘deep story’ (Eco Citation2003) of the ‘coming out of the closet’ metaphor. In fact, although they represent two different empirical spaces, the ‘closet’ and the ‘baño’ have the same meaning because they occupy the same position in the metaphorical schema (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1980), both in English and Spanish. Replacing ‘closet’ with ‘baño’ makes the metaphorical ‘coming out of the closet’ schema locally readable, leaving its political meanings unaltered. In so doing, despite linguistic divergences, the local memoryscape builds on the transnational schema of the ‘coming out of the closet’ narrative.

Instead, the translations of ‘it’s time to be gay’ as ‘hay que liberarse’ and ‘gay and proud’ as ‘liberación homosexual’ signify a more pronounced ideological difference from the material originating in the USA. Although the ‘coming out of the closet’ metaphor is part of LGBT+ ‘pride politics’, the corresponding Spanish word ‘orgullo’ did not resonate with the historical experience of Argentinian homosexual activists for almost two decades (Bellucci Citation2020 [Citation2010], p. 73). By contrast, the FLH uses the signifier ‘liberación’, which is much more ideologically resonant with the Argentinian context. However, in this case, too, we see that the underpinning narrative schema does not change when it is invested with different linguistic and ideological content.

As Warner emphasizes, discourse establishes a public by addressing it. Yet, this is only achievable if readers recognize in texts a shared social and semiotic realm composed of elements such as ‘habitus, topical concerns, intergeneric references, and circulating intelligible forms’ (Warner Citation2005, p. 106). The translation of ‘closet’ to ‘baño’ and ‘gay and proud’ as ‘liberación homosexual’ makes metaphors and stories readable at a local level. Warner overlooks translation in his theory because he focuses on historical experiences in the USA. However, in cross-border circulation, translations become crucial in grounding language in a concrete manner, by adopting the ‘vernaculars’ of circulatory spaces (Warner Citation2005, p. 108) and enabling local readers to embed themselves within the narratives. The case of the FLH shows how local activists embrace transnational memoryscapes and position themselves within movements that transcend national and linguistic boundaries. They do this by modifying transnational narratives to ground them in the new local social realities of circulation.

By conceptualizing memoryscapes as schemata, we can thus see how activists are part of the same movement despite ideological, historical, linguistic, and narrative divergences. In this sense, the tension between the North American and Argentinian homosexual liberation activists is very informative. Various studies on the FLH have emphasized that the Stonewall riots are never mentioned in the FLH’s publication, even if it is evident that material republished in Argentina might have been taken from publications commemorating Stonewall. Argentinian activists, mostly from the radical Left, did not see Stonewall as a seminal event and/or were reluctant to refer to the USA identity because of their ideological position (Fernández Galeano Citation2019, Insausti Citation2019). However, the analysis of the comic’s translation shows that schemata are transferred from one context to another, underpinning new stories that resonate with the local activist viewpoints. In sum, memoryscapes as schemata become spaces of mediation in which stories connect with and map onto each other, where deeper similarities are recognized despite the possibility of geopolitical tensions and ideological antagonisms between groups at a more ‘visible’ level. Convergences and divergences are thus inscribed and contained in a space of mutual translation and intelligibility.

Conclusions

On 24 March 1976, a coup d’état installed a military dictatorship that would claim the lives of tens of thousands of militants and citizens over the next six years. The FLH was disbanded and some of its most prominent figures moved abroad. Yet, the memory of this group is still vibrant and visible. The stories that were shaped by the FLH, and the FLH itself as a story and memory of activism (Rigney Citation2018), live on in archivesFootnote9, in exhibitions, demonstrations, on walls and in activists’ paraphernalia and slogans.

Through an exploration of the Argentinian queer press, I have shown that memory becomes a medium for building coalitions among people who have discovered a common condition of oppression. This happened because a common transnational memoryscape emerged and allowed activists to map their different histories onto each other. Appadurai emphasizes the role of metaphors in providing schemata for imagining new stories and lives. What emerged from my analysis of the FLH’s texts and mnemonic labour is the adaptation of metaphors and analogies that are ‘based on cross-domain correlations’ (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1980, p. 245). These correlations allow for the circulation and exchange of cultural and symbolic repertoires among different social groups. This is evident in the adaptation of the ‘coming out of the closet’ metaphor as well as in the use of Newton’s letter by LGBT+ movements.

Schemata circulate transnationally and support the creation of new stories. They orient the mnemonic labour of activists, who will invest schemata with specific content adapted to local contexts and situations. For example, schemata provide activists with archetypical roles (i.e. the oppressed and the revolutionary) and sequences that enable them to build on the past to nurture aspirations and envision new futures.

The focus on underlying schemata rather than on specific events makes the multidirectional logic that informs the memory–activism nexus in LGBT+ social movements (Rothberg Citation2009, Rigney Citation2018) even more evident: mnemonic labour is the activists’ ability to build new worlds out of the debris of older ones, and this means also borrowing and adapting stories coming from other social groups, historical experiences and parts of the world. Transnational memoryscapes open up ‘the separate containers of memory and identity’ (Rothberg Citation2009): this reveals how social groups and collective memory result from dialogical co-constitutions in which stories move within a shared space of meaning.

On one hand, with regard to the history of LGBT+ activism, the multidirectional approach outlined in this article may help overcome the ‘from-Stonewall-diffusion-fantasy’ (Bacchetta Citation2002). On the other hand, the prism of cultural memory studies offers the potential to transcend the ‘myopia of the visible’ (Melucci Citation1989) that often characterizes social movement studies. To realize this potential requires shifting the analytical focus from the visibility of events to the semiotic labour that underpins all activist narratives, sustaining their struggles to come.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The elaboration of this article benefited from discussions within the research group of the European Research Council-funded project Remembering Activism: The Cultural Memory of Protest in Europe – ReAct, based at Utrecht University under the direction of Ann Rigney. I would like to express my gratitude to Tashina Blom, Duygu Erbil, Ann Rigney, Sophie van den Elzen, and Clara Vlessing for their valuable suggestions and comments on an early version of this article.

2 In this article, for the sake of simplicity, I will interchangeably use the terms ‘LGBT+’, ‘homosexual’, and ‘gay’ activism. These expressions are not synonyms or entirely co-extensive. Nevertheless, the 1960–70s homosexual liberation movements are historically part of the genealogies of the contemporary LGBT+ movements.

3 In this article, I use the term ‘memoryscape’ both as a noun and as a verb, because I view it as a doing rather than an object. ‘Memoryscaping’ struggles means to sustain activism by crafting narratives that encompass past, present, and future. My gratitude goes to Tashina Blom for aiding me in developing this perspective.

4 Practical knowledge of the production and circulation of typographical material seemed to be strategic for establishing homosexual organizations. Notably, the founding figures of homosexual organizations in the Americas – Henry Gerber in the 1920s USA and Héctor Anabitarte in 1960s Argentina – both had roles as postal workers or typographers (Insausti Citation2019, Streitmatter Citation1995). This allowed them to understand circulation dynamics and, in some instances, evade correspondence control (Insausti and Fernández Galeano Citation2020).

5 As Warner recalls, attention is the cognitive force that sustains group-building, serving as ‘the principal sorting category by which members and nonmembers are discriminated’ (Warner Citation2005, p. 87).

6 Come out! was the newspaper of the Gay Liberation Front in the USA, published from 1969 to 1972.

7 Ferro and Latrónico were two key Argentinian activists who lived in the USA in the 1960s-70s. For a reconstruction of the history of the TWGR and the role of migrant LGBT+ activists in connecting gay liberation movements in the USA and Argentina, in a bidirectional way, see Latrónico Citation2009, Queiroz Citation2020, Garrido Citation2021.

8 For a thorough analysis of Somos see Patricio Simonetto (Citation2017).

9 For example in the Sexo y Revolución collection of the Centro de Documentación e investigación de la cultura de izquierdas or the Archivo desviados, both based in Buenos Aires.

References

- Alexander, J.C., 2012. Trauma: a social theory. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Appadurai, A., 1996. Modernity at large: cultural dimensions of globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Armstrong, E.A., and Crage, S.M., 2006. Movements and memory: the making of the Stonewall myth. American sociological review, 71 (5), 724–751.

- Árvay, A., and Foote, K., 2019. The spatiality of memoryscapes, public memory, and commemoration. In: S. De Nardi, H. Orange, S. High, and E. Koshiven-Koivisto, eds. The Routledge handbook of memory and place. London-New York: Routledge, 129–137.

- Bacchetta, P., 2002. Rescaling transnational ‘queerdom’: Lesbian and ‘Lesbian’ identitary-positionalities in Delhi in the 1980s. Antipode, 34, 947–973.

- Bellucci, M., 2020 [2010]. Orgullo. Carlos Jáuregui, una biografía política. Buenos Aires: Finale Abierto.

- Ben, P., and Insausti, S.J., 2017. Dictatorial rule and sexual politics in Argentina: The case of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual, 1967–1976. Hispanic American historical review, 97 (2), 297–325.

- Consoli, L.M., 1971. Ai compagni rivoluzionari. FUORI!, 0, 8.

- Cusicanqui, S.R., 1984. Oprimidos pero no vencidos. Luchas del campesinado Aymara y Qhechwa, 1900–1980. La Paz: Hisbol - CSUTCB.

- Davis, G., and Guy, L., eds., 2022. Queer print in Europe. London: Bloomsbury.

- Eco, U., 1979. Lector in fabula. La cooperazione interpretativa nei testi narrativi. Milano: Bompiani.

- Eco, U., 1984. Semiotics and philosophy of language. London: Macmillan.

- Eco, U., 2003. Experiences in translation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Encarnación, O., 2016. Out in the periphery: Latin America’s gay rights revolution. London-New York: Oxford University Press.

- Erll, A., 2011. Travelling memory. Parallax, 17 (4), 4–18.

- Erll, A., 2022. The hidden power of implicit collective memory. Memory, mind & media, 1 (e14), 1–17.

- Fernández Galeano, J., 2019. Cartas desde Buenos Aires: El movimiento homosexual argentino desde una perspectiva transnacional. Latin American research review, 54 (3), 608–622.

- Garrido, G., 2021. The world in question: a cosmopolitical approach to gay/homosexual liberation movements in/and the ‘Third World’ (from Argentina to the United States). GLQ: A journal of Lesbian and gay studies, 27 (3), 379–406.

- Genet, J. 1970a. Bobby Seale, the Black Panthers and us white people. The Black Panther. Black Community News Service, 28 Mar, p. 7.

- Genet, J. 1970b. I must begin with an explanation of my presence in the United States. The Black Panther. Black Community News Service, 9 May, p. 6.

- Gillan, K., 2020. Temporality in social movement theory: vectors and events in the neoliberal timescape. Social movement studies, 19 (5–6), 516–536.

- Hocquenghem, G., 1977. Le désir homosexuel. Paris: Jean-Pierre Delarge.

- Insausti, S.J., 2015. Los cuatrocientos homosexuales desaparecidos: memorias de la represión estatal a las sexualidades disidentes en Argentina. In: D. D’Antonio, ed. Deseo y represión: sexualidad, género y estado en la historia argentina reciente. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Imago Mundi, 63–82.

- Insausti, S.J., 2019. Una historia del Frente de Liberación Homosexual y la Izquierda en Argentina. Revista estudos feministas, 27 (2), 1–17.

- Insausti, S.J., and Fernández Galeano, J. 2020. Archivos digitales queer. Moléculas Malucas, 29 Apr. Available from: https://www.moleculasmalucas.com/post/archivos-digitales-queer [Accessed 7 Dec 2022].

- Katriel, T., 2021. Defiant discourse: speech and action in grassroots activism. London-New York: Routledge.

- Keck, M.E., and Sikkink, K., 1998. Activists beyond borders: advocacy networks in international politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Lakoff, G., and Johnson, M., 1980. Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Latrónico, N., 2009. My memories as a gay militant in NYC. In: T. Aviccoli-Mecca, ed. Smash the church, smash the State! San Francisco: City Lights, 48–55.

- Leighton, J., 2019. ‘All of us are unapprehended felons’: gay liberation, the Black Panther Party, and intercommunal efforts against police brutality in the Bay Area. Journal of social history, 52 (3), 860–885.

- McKinney, C., 2020. Information activism: A queer history of Lesbian media technologies. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Melucci, A., 1985. The symbolic challenge of contemporary movements. Social research, 52 (4), 789–816.

- Melucci, A., 1989. Nomads of the present: social movements and individual needs in contemporary society. Edited by P. Mier and J. Keane. London: Hutchinson Radius.

- Modarelli, A., and Rapisardi, F., 2019 [2001]. Fiestas, baños y exilios. Los gays porteños en la última dictadura. Buenos Aires: Página 12.

- Newton, H.P. 1970. A letter from Huey to the revolutionary brothers and sisters about the Women’s liberation and gay liberation movements. The Black Panther. Black Community News Service, 22 Aug, p. 5.

- Phillips, K.R., and Reyes, G.M., 2011. Introduction. Surveying global memoryscapes: The shifting terrain of public memory studies. In: K.R. Phillips, and G.M. Reyes, eds. Global memoryscapes: contesting remembrance in a transnational age. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1–26.

- Plummer, K., 1995. Telling sexual stories: power, change and social worlds. London-New York: Routledge.

- Propp, V., 1968 [1928]. Morphology of the Folktale. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Queiroz, J. 2020. Third world gay revolution. Moléculas Malucas, 22 Aug. Available from: https://www.moleculasmalucas.com/post/el-third-world-gay-revolution [Accessed 15 Oct 2022].

- Rigney, A., 2016. Cultural memory studies: mediation, narrative, and the aesthetic. In: A.L. Tota, and T. Hagen, eds. Routledge international handbook of memory studies. London-New York: Routledge, 65–76.

- Rigney, A., 2018. Remembering hope: transnational activism beyond the traumatic. Memory studies, 11 (3), 368–380.

- Rigney, A. unpublished. Memoryscapes in activism: the Commonweal, 1885–1894.

- Rothberg, M., 2009. Multidirectional memory: remembering the Holocaust in the age of decolonization. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Salerno, D., 2021. A semiotic theory of memory: between movement and form. Semiotica, 241, 87–119.

- Simonetto, P., 2017. Entre la injuria y la revolución: el Frente de Liberación Homosexual Argentina, 1967–1976. Buenos Aires: Universidad de Quilmes.

- Simonetto, P., 2020. La otra internacional. Prácticas globales y anclajes nacionales de la liberación homosexual en Argentina y México (1967–1984). Secuencia, 107, 1–37.

- Streitmatter, R., 1995. Unspeakable: The rise of the gay and lesbian press in America. Boston: Faber and Faber.

- Stryker, S., 2017 [2008]. Transgender history. New York: Seal Press.

- Szulc, L., 2017. Transnational homosexuals in communist Poland: cross-border flows in gay and Lesbian magazines. Cham: Springer.

- Warner, M., 2005. Publics and counterpublics. New York: Zone Books.

- Wertsch, J.V., 2021. How nations remember: a narrative approach. London-New York: Oxford University Press.

- White, E., 1993. Genet: a biography. London-New York: Vintage Books.

List of primary sources and archives

- Come Out!, vol. 1 n. 5, September 1970. The Come out! archive – https://outhistory.org/exhibits/show/come-out-magazine-1969-1972/the-come-out-archive [Accessed 4 September 2023].

- Fag Rag - Gay Sunshine, Summer 1974. IHLIA – Amsterdam.

- FLH. 1972. Boletín Del Frente de Liberación Homosexual de Argentina, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- FLH. 1973a. Homosexuales, July, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- FLH. 1973b. Somos, 1, December, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- FLH. 1974a. Somos, 2, February, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- FLH. 1974b. Somos, 3, May, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- FLH. 1974c. Somos, 4, August-September, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- FLH. 1974d. Somos, 5, s/d, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- FLH. 1974e. Sexo y Revolución, 2° ed., with Somos, 5, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- FLH. 1975a. Letter from Argentina. The Body Politic. Gay Liberation Journal, January/February 1975. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/bodypolitic17toro [Accessed 4 September 2023].

- FLH. 1975b. Somos, 6, August, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- FLH. 1975c. Somos, 7, December, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- FLH. 1976. Somos, 8, January, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- Nuestro Mundo. 1970. Nuestro ‘Mundo’ – Boletín Editado Por Homosexuales de Buenos Aires, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.

- Nuestro Mundo. 1972. Carta Del Comandante Supremo Del Partido de La Panteras Negras a Los Hermanos y Hermanas Revolucionarios Sobre Los Movimientos de Liberación Femenina y de Liberación Homosexual, CeDinCi – Colleción Sexo y Revolución – Buenos Aires.