ABSTRACT

Bringing queer affect theory to bear on the history of fashion magazines, I track how in the 1990s Dutch – an independent fashion publication which became increasingly popular across Europe and the United States at the turn of the century – began to interrogate the visual ideologies of the fashion system. In a historical moment in which the sense of relief brought to the LGBTQ community by the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy coincided with the deflation of radical energies within gay activism and the partial integration of the community into mainstream state systems, a coterie of gay fashion editors and photographers reconceived of the fashion magazine as a platform for gay erotica and collective identification, beyond a heteronormative economy of consumption. Through its photographic spreads and feature articles, Dutch disidentified with the conventional genre of the fashion magazine, typically a mediator of fantasies of glamour and upward mobility. This article argues that Dutch was a covert archive of queer feelings that, by attuning its readership to a counter-mood of hope and pleasure, initiated the formation of fashion magazine counterpublics, ultimately reshaping the fashion mediascape for years to come.

Introduction

Fashion magazines have typically functioned as material signifiers of social status and upward mobility, shaping commercially palatable appearances as aspirational aesthetic ideals. As Angela McRobbie explained in her compelling analysis of the ‘image industry’, Vogue magazine’s ‘commitment to fashion as art and as luxury consumption for upper middle-class women’ has moulded the structure and conventions of fashion magazine production. It has done this by evoking fantasies of beauty, wealth, lifestyle, and female heterosexuality in order to ‘appeal to the features of taste and distinction by which particular readers are addressed as a means of confirming their class, status and cultural capital’ (McRobbie Citation1998, pp. 162–3). Matthias Vriens, the former editor-in-chief and fashion director of Dutch magazine, would agree. In our interview, he adamantly stated that the editorial structure of fashion magazines and advertising is still sexist, racist, and ageist, in addition to being ‘far behind’ in regard to queer culture.

But while it is true that over time the imagery published in fashion publications has remained relatively static (McRobbie Citation2008, p. 90) – in line with what has been called the ‘hegemonic fashionable ideal’, embodied by ‘young, slender, conventionally beautiful, able bodied, and, most often, a cisgender woman’ (de Perthuis and Findlay Citation2019, pp. 223, 221) – and has reiterated stagings of femininity conjuring psychic scenarios that ‘operate as a self-perpetuating regime, which refutes and disavows the asking of questions which pertain to the critique of masculinity, patriarchy, and the enforcement of norms emanating from the heterosexual matrix’ (McRobbie Citation2008, p. 99), those same scenarios have also been historically recoded by readers with a non-heterosexual sensitivity. After all, the fashion magazine is a genre that in trafficking in gossip, extravagance, desirability, and role-play has always had an affinity with queer taste and has therefore invited ‘homospectatorial’ (Fuss Citation1991) consumption and homoerotic fantasies.Footnote1 In other words, the fashion magazine may prompt ‘queer lines of desire’ (Probyn Citation1996, p. 59) that can instigate our imagination to form unexpected affective connections. The fashion magazine lends itself to a hermeneutics that thrives on the pleasure of experiencing sensuous and ambiguous relations to the magazine’s form and contents beyond a heteronormative economy of consumption.Footnote2

By casting retrospective light on queer consumption regarding fashion magazines and queer susceptibility to the moods of fashion discourse, the work of ferreting out queer subtexts of fashion magazines makes apparent the following paradox: the queerness that underpins fashion’s glamorous imaginary has been, historically, heavily disguised, and fashion magazines have ended up reproducing imaginaries with which minority subjects have had a conflicted relationship. Notwithstanding the fashion magazine’s enchantment for queer readers, the fashion magazine has generally failed to explicitly engage queer publics or to shift its thematic conventions. This scenario of camouflaged queerness, however, underwent a tangible change in the 1990s, when fashion magazines emerged as sites for the documentation of the shifts in cultural understandings and representations of gendered and sexual identities.Footnote3 Despite the historical involvement of LGBTQ creatives in the production of fashion magazines and fashion’s imbrication with the body and identity, there is still very little research into the queer contents of fashion publications. The aim of this article is to add a tassel to the covert queer mosaic that is the history of fashion magazines by recovering an archive that has not received sufficient scholarly attention; thus, it makes a contribution to queer historiography, and broadens, through a queer optic, the understanding of the affective formation of fashion print cultures.

My focus is Dutch (1994–2002), an ‘alternative’ fashion magazine rich with gay content that has left a sound legacy in fashion media cultures.Footnote4 Dutch offers insights into the under-investigated relationship between fashion print culture and queer culture, as well as between fashion politics and queer politics, revealing the challenges and contradictions of LGBTQ representation in the ad-driven fashion mediascape. Building on its history, in the context of the AIDS ‘post-crisis’ era (Kagan Citation2018), and conducting an examination of its visual content, I will theorize Dutch as a ‘queer desirous archive’ that allowed for the formation of ‘fashion magazine counterpublics’. Said publics longed for a sensual representations of subjects with whom they could identify or to whom they could cathect, and thereby find pleasure in an affective and erotic virtual engagement with their bodies. Engaging with queer and feminist affect theory, I will show how Dutch drew its publics into a queer ‘counter-mood’ within which gay readers could forge an imaginary community as a response to the stigmatization, sanitization, policing, and commercial exploitation they had been subjected to.

Dutch in the ‘post-crisis’ editorial economy

Launched in 1994 by photographer Sandor Lubbe, who had found in Mercurius an indie art publisher willing to produce a unique fashion magazine in The Netherlands, Dutch was originally aimed at the Dutch market and all its articles were written in Dutch. However, after only a few issues, it relocated its office from Amsterdam to Paris and switched its language from Dutch to English, reaching a total print run of nearly 30,000 across Europe and the United States at the end of the 1990s. Dutch surfaced on the market within a context in which casual and flexible art professionals were part of a workforce of self-employed cultural producers willing to invest in collaborative projects and generate cultural value outside of the market, while to some degree inevitably compromising with it. As Matthias Vriens recalls:

We had no money. For the first years, the magazine was made in the living room of my apartment in Paris. I paid for all the FedEx shipping myself. You know, there was hardly any money to produce, so everybody who worked for the magazine participated and donated their time and their art for free. I worked for free up until the last few years. Toward the end, that changed a little bit. We had a proper office, but finances were still miniscule.

The editorial history of Dutch magazine (1994–2002) coincides with a period of late liberalism in which politics, activism and legal changes in Europe and the United States reverberated in complex ways in the circulation of LGBTQ discourses across fashion media. The ‘post-crisis’ period in the history of AIDS, initiated by the effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy in the second half of the 1990s, brought a sense of relief to the LGBTQ community. Such relief, however, rested upon a certain disillusionment and frustration with how local governments had failed the community by dealing with the epidemic through moralizing about gay sexual practices. The period of collective emotional exhaustion coincided with the deflation of radical energies within gay activism and the consolidation of political practices reliant on civil rights arguments: this led to a domestication of LGBTQ politics, the alignment of the gay community with governments on the grounds of newly gained civil rights and, often, its integration into mainstream state systems, with major corporations looking more and more at gay and lesbian subjects as a financially exploitable constituency (Seidman and Richardson Citation2002, pp. 16–8).

Reflecting a new gay consumerist ethos in the context of a proclaimed social equality, gay magazines like Attitude (1994-), Têtu (1995–2015) and Instinct (1997–2015) began promoting the homonormative lifestyle of white, urban, and affluent subjects to the exclusion of people of colour, working-class subjects, and transgender folks. In the international fashion media landscape, the ‘glossies’ (e.g. Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar) were consolidating a visual field wherein neoliberal narratives of autonomy, individualism, and self-improvement fuelled the fantasy that self-actualization could be attained via the fulfilment of consumerist desires; meanwhile, independent style magazines such as the British The Face (1980–2004; 2019-), i-D (1980-), and Arena (1986–2009) had embraced from the 1980s an ‘anti-fashion’ approach that in giving expression to youth subcultures displayed an open attitude toward issues of class, race, and sexuality, but remained largely estranged from queer concerns. The Dutch market in particular was not dominated by major fashion publications: these were either completely absent or they surfaced on the editorial market only briefly and late.Footnote5 While inevitably being shaped by its local cultural coordinates, Dutch was equally responsive to the creative energies of a globalized fashion scenario.

In the Netherlands, the 1994–2002 era was a period of innovative social legislation (comprising a ban on discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in 1994, recognition of domestic partnerships for same-sex couples in 1998, and, for the first time in Europe, the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2001) brought about during the tenure of Prime Minister ‘Wim’ Kok (1994–2002). Yet, in 2002 homosexual and far-right politician Pim Fortuyn formed a populist party (LPF) which quickly became one of the largest in the country. LPF encouraged drastic positions against multiculturalism and immigration while simultaneously standing in great support of gay civil rights. As Fatima El-Tayeb (Citation2012) explained, the sociopolitical climate in the Netherlands was emblematic of a particular conjuncture in which a neoliberal restructuring of society was joined by ethno-nationalist sentiment: this was consistent with the rise of nationalism throughout the 1990s and the ascendance of populism as a political force, with right-wing populist parties becoming established in the legislatures of various western democracies. Within such a convoluted scenario, the mainstreaming of homosexuality became commonplace in Dutch popular media, where sexuality was approached as just another component of a permissive society, one with a very loose link to activism (Smelik Citation2006, pp. 420–2).Footnote6 This was part of a broader tendency in the media landscape of the 1990s, where the rise in representation of gay and lesbian content was also a way to expand the gay consumer market and cater to upscale gay audiences, particularly in light of the economic recession of the early 1990s.

A fashion magazine with no fashion

In 1998, as Matthias Vriens, with no fashions or money, was approaching Dutch's print deadline, he ‘needed to come up with a solution that would blow everybody out of the water’; finally, ‘he went with nothing and produced one of the most radical and memorable issues ever: a fashion magazine with no fashion’ (Aletti Citation2019, p. 280). The cover story of said issue was shot by Mikael Jansson in Stockholm's archipelago islands. Comprised of eighty-two pages of full nudity the story alluded, as Vriens stated in an introductory note to the photo spread, to the fantasy of ‘freedom from censure, from fashion and from fear’. While the names of fashion labels were credited on every page, their clothes were nowhere to be seen. As Vriens recalls:

What we did in the ‘Nude’ issue was a dangerous thing because at the time powerful companies like Chanel had been known for suing people for misusage of fashion or accessories in editorial structures. We could have said ‘Okay, we are in difficult times (financially), let’s play it safe’, but that's not my nature, so I turned it around. Two days later, after the magazine was dropped off, I got a letter from Karl Lagerfeld saying that it was the most beautiful and poetic thing that he'd seen in a long time.

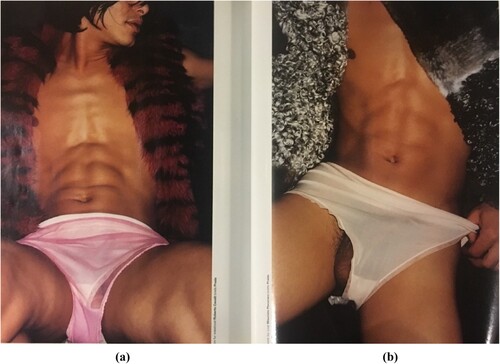

The prevalence given to nudity is also typified by the photo spread ‘Fuzz Box’ (), shot and styled by Vriens in 1999. In the intimate snapshots that compose this photographic narrative, part of an issue dedicated to animal rights activism in protest of the fashion industry’s then copious use of fur, there is no clothing except for a few pairs of see-through women's underwear, along with faux fur boleros, on male models. The fashion photographs published in Dutch were about ‘everything but clothes’ (Teunissen Citation2015), for they privileged narratives – set in unspecified and at times sordid settings that challenged what Scott Herring calls ‘visual metro norms’ (Citation2006, p. 220) and deliberately avoiding the far-flung exotic scenarios that typically helped construct the aesthetic imaginary of fashion – in which the minimal use of clothing served the shaping of the story. At the beginning, the nudity of the models in the magazine’s photo stories was primarily the result of material conditions. Indeed, due to the limited funds invested in the magazine and the initial lack of relationships with fashion companies, they could barely afford to include any designer garments in their pages. As Vriens succinctly put it:

Nudity was primarily survival gear. I could not get any great fashion whenever I would go to Michèle Montagne’s [a Paris-based PR agency representing cutting-edge international brands]. Whoever had important magazines got half of the collections to shoot in their pages and I would just get their bones. If I were to get any advertisement at all to keep the magazine running, I had to come up with something different.

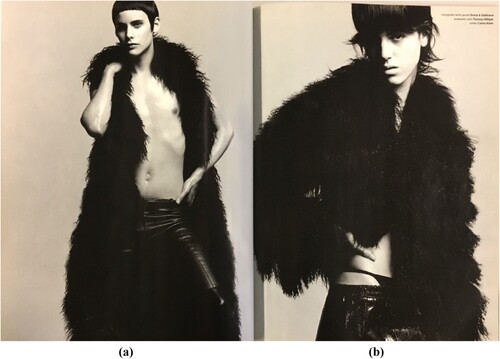

As Thomas Schenk’s photo shoot ‘Crossing’ from 1999 shows (), along with many other photographic portfolios in the history of the magazine, Dutch appeared free and daring, with a taste for non-normative performances of masculinity and femininity. Despite not advancing identitarian claims, Dutch proliferated queer visual discourses which could be understood in view of its editors’ impatience with the representational conventions of fashion and lifestyle publications. Dutch, in fact, was also reacting to the growing success of men’s lifestyle magazines: FHM (‘For Him Magazine’, 1985-), Maxim (1995-), and Loaded (1994–2015) mediated a ‘laddish’ culture of heterosexual sex, sport, and drinking (Shinkle Citation2008, p. 91), which, coupled with the postfeminist discourses of empowered femininity advocated in the glossies, provided a playground for the production of heteronormative discourses.

In response to the style magazines on the market, the Dutch team wanted to carve out alternative fashion imaginings. Following Elspeth Probyn, images can carry a socio-cultural imaginary into play that manifests itself in bodies or as virtual material: they can dislodge desire from its attachment to certain objects and therefore elude normative arrangements of subjects and objects. In so doing, ‘they can carry longing: they throw us forward into other relations of becoming and belonging’ (Citation1996, p. 59). According to Probyn, images traverse the social: they can suggest forms of relationality and connections that bypass the traps of realist epistemologies, hinting at alternative, sensible ways of rethinking one’s own orientation to the world and to others. Images can indeed ‘cause different ripples and affects, effects of desire and desirous affects’ (p. 59). Dutch created unexpected and often hilarious or sexually arousing scenes in order to lure its audience into becoming alert to the strange, the ambiguous, the non-transparent and to incite them to reconceive of fashion magazine reading as a practice guided by the willingness to be reoriented, in one’s affective attachments, toward ideas and bodies that eclipsed the parameters of the fashionable. It cultivated a language of queerness by way of staging subjects and modes of relationality that troubled the ‘historical regime of fashion’ (Gaugele Citation2014, p. 166) in its delimitation of which bodies must be visualized and which feelings should be conveyed.

The personnel of Dutch was predominantly gay: a factor that explains the outstanding difference between the vocabulary of Dutch and that of other contemporary fashion magazines as well as the magazine’s aesthetic sensitivity and commitment to pushing magazine readers to engage with sexual, social, and moral discourses that neither traditional women’s magazines nor less commercial ones were accustomed to dealing with. Jop van Bennekom, the co-founder and co-editor, with Gert Jonkers, of queer zine BUTT (2001-), told me that ‘all the things that were happening in the gay scene and club scene in Amsterdam overlapped with the fashion scene. […] When you look at people who were writing for Dutch, they also appeared in BUTT a few times’.Footnote7 Amsterdam, and the Netherlands more broadly, as Anneke Smelik explained (Citation2017, p. 10), acquired a highly liberal reputation beginning in the 1960s when the country found itself particularly affected by the new youth culture and the concurrent development of a radical LGBTQ scene, both of which deeply informed the emergence of a local fashion community.

The geographical locale in which Dutch surfaced justified and inspired the formation of a young queer readership that saw in ‘style–fashion–dress’ (Tulloch Citation2010) not merely a medium of self-expression but rather a platform for mutual recognition and belonging. In Amsterdam Van Bennekom and Jonkers had created a gay network through club nights: parties like ‘Electro Clash’ became an underground connector for a cluster of LGBTQ fashion creatives who often travelled all the way from London or Paris to attend. The intermingling of queer and fashion culture in 1990s Europe did have an impact on the magazine content.

As Vriens explains:

The people, the journalists, the stylists working for the magazine were gay. Gay culture is phenomenally interesting and rich, and when you flip through the magazine those references to gay culture come across. However, if anyone dismissed the magazine as just being gay, that would be too limited. Dutch was partially a multi-cultural sexual magazine.Footnote8 What is interesting is the fact that we created that in the Nineties.

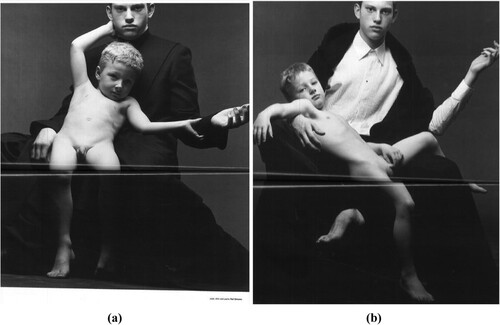

In 1998, in the fourteenth issue of the magazine, article features on Lee Williams’s post-grunge novel After Nirvana (1997), which recounted the life of young hustlers in Oregon engaging in bareback sex, provide the discursive framework for the photographic portfolio ‘U-th!’, a gallery of pictures of children and youngsters, each taken by a different photographer. The photo spread is introduced by a text, signed by Matthias Vriens, in which he argues for retaining ‘those natural emotions expressed for children […] which have come to be readily misconstrued as “unnatural” or “perverse”’. Two years later, in 2000, a photo spread titled ‘Vespers’ shot by Philippe Cometti () portrayed a naked child sprawled out on the lap of a pre-teenager dressed in clerical clothing. Cometti’s photo spread prompts the viewer to pay attention to the child-model’s ease in front of the camera as well as his pleasurable engagement with the other male body. Scenes like this probed ideas of child sexuality and intergenerational forms of kinship, and thereby forged a visual trajectory for rethinking childhood from a queer angle.Footnote10 These editorials came out just as the media panic around ‘kiddie porn’ was reaching its peak (Vänskä Citation2017, p. 13) and can thus be read as a challenge by Dutch to the polarizing rhetoric of media discourses surrounding child pornography.

The goal of Dutch as an editorial project was to extricate the fashion imagination of magazine publics from an attachment to normative fantasies and potentially envelop the readers in a collective community of queer feeling that functioned as a scene of mediation for their own tastes and desires. Dutch asked its readers to involve themselves, if only for a brief time, with scenes animated by ambiguously erotic children, fictional gay porn actors, and sexually exuberant working-class women (as in the case of a lengthy portfolio shot by Alexei Hay in 2000 in which amateur models shamelessly parade their naked bodies in a trailer park, mocking the staged performances of professional fashion models). In its pages, characters who had normally been unsuitable for fashion representation were subjectivized, and the readers were expected to join in the publicness of these subjects.

By disidentifying with aesthetic ‘regimes of the normal’ (Warner Citation1993, p. xxvii) – ‘disidentification’ being, according to Jacques Rancière, a primary tactic of ‘subjectivization’ (Rancière Citation1992, p. 61, Dasgupta Citation2008, p. 75) – alternative representations could reinscribe in the social field the subjects cast on the margins of the public sphere. While Dutch did not necessarily brim with a utopian potential to throw a spanner in the works of normativized protocols of representation, I propose that it might have been more capable of doing so than other magazines. This is because its fashion content incentivized the embodied imagining of particular styles of being in the world by confronting the readers with stylized scenes that purported to solicit a certain – queer – version of that world. After all, print cultures are historically relevant to queer politics insofar as they address a lack of representation and the need to negotiate a majoritarian public sphere that elides the existence of subjects who, to borrow from José Muñoz, ‘do not conform to the phantasm of normative citizenship’ (Citation1999, p. 4).

The disavowal of affective and aesthetic belonging can be operationalized, from Muñoz’s vantage, through practices of disidentification. Indeed, in his theorization, disidentification exceeds what both Judith Butler and Sara Ahmed construe as an experience of misrecognition:Footnote11 for him, to disidentify with a dominant aesthetic means to reshuffle its codes in a way that both exposes its exclusionary logic and gives voice to those individuals who are excluded from that logic. In Muñoz’s own words, ‘[…] disidentification is a step further than cracking open the code of the majority; it proceeds to use this code as raw material for representing a disempowered politics or positionality that has been rendered unthinkable by the dominant culture’ (Citation1999, p. 31). Thus, disidentification is an aesthetic performative strategy of queer insurrection that seeks to challenge and transform a cultural logic from the inside by rerouting its codes towards the empowerment of a minority group. Dutch re-coded the visual language of fashion by staging countercultural ideas and images within the boundaries of the fashion magazine, ultimately stretching those boundaries and revealing the saturation of fashion media with canonically desirable looks. Throughout the remainder of the article, the disidentificatory ethos of Dutch will be dissected.

Fashioning gay erotic pleasures

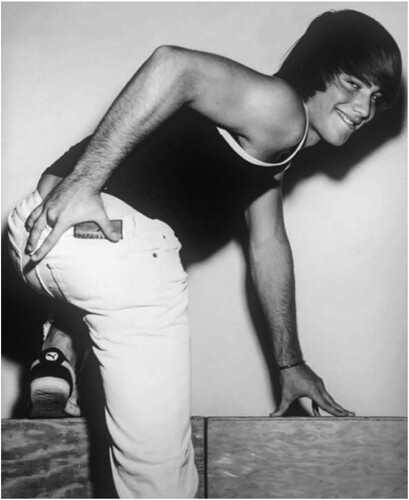

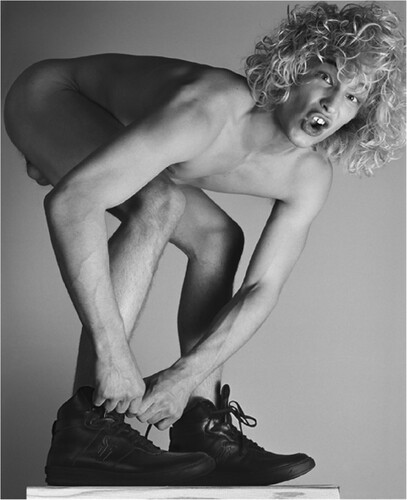

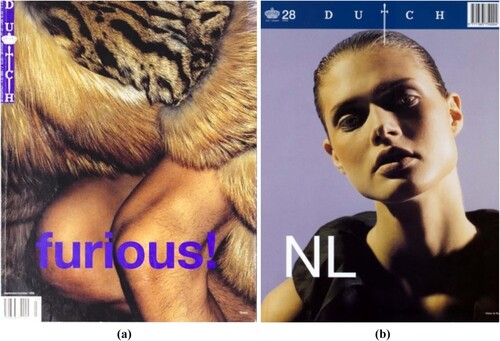

Matthias Vriens commissioned and shot some of the most visually confrontational and humorous stories in the history of Dutch. In a black and white editorial titled ‘Plug of flesh’ ( and ), which blatantly references Robert Mapplethorpe’s portraits, young men play with their butts and expose their genitalia while sneering or giggling. The spread demonstrates Vriens’s commitment to introducing into the magazine gay visual material that was outside of the domain of fashion without either dissimulating it or elevating it to the status of art: the nonsensical exhibitionism of his subjects was an experiment in testing how humour could be used to abdicate fashion modelling scripts as well as the expectations of formal perfection placed on a fashion magazine. Bawdy humour is a frequent register in the pages of Dutch, especially in the sex-themed articles and softcore photo spreads. In the portfolio ‘Pony boy’ shot by Andrew McKim in 1998 (), we flick through a sequence of nearly identical slim male bodies shot from the side on all fours. The handkerchiefs in the back pockets nod at the semiotics of 1970s gay self-fashioning, while the saddles placed on their arched backs suggest that in the fiction of the scene those man-ponies are waiting to be ridden.

Dutch expanded the spectrum of who and what could be included in a fashion magazine by tapping into a wide range of visual forms and sources, such as queer photography, sex zines, and indie cinema. The photo spread ‘Rentboys’, shot by David Zanes in 1996, follows young ‘trade’ men parading their bodies in front of the camera, and is accompanied by an article on the history of male strippers.Footnote12 ‘Lone star’, shot by Steven Klein in 2000, follows the fictional day of a frustrated amateur porn actor who hangs out, bored, in unglamorous settings, stroking his flaccid penis. Such an emphasis on gay eroticism in the magazine was symptomatic of developments in the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the late 1990s.

In the 1980s the fashion industry had been decimated and the AIDS crisis had triggered a paranoia that reverberated in an anxious, compensatory cult of hypermasculine ‘impenetrable’ men in the pages of fashion magazines (Wilson Citation1992, p. 36). In the mid-1990s, although the stigmatization and moralization of gay sex persisted, a new genre of softer, feminine masculinity – what Richard Dyer called the ‘typification’ of ‘queer masculinity as white sensitivity’ (Citation1993, p. 80) – timidly percolated, with its erotic ebullience, into the pages of Dutch. In them, we witness a renewed sexual openness in the representation of gay men who deliberately exhibit their sexual desire. By inserting gay eroticism into the orbit of fashion editorial publishing, Dutch asserted a certain freedom from the taboo of gay sexuality in the pages of fashion magazines. As Vriens recounts:

I lost many of my gay friends to AIDS in the 1980s and early 1990s. It was a devastating time. But within the stretch of this horrible time, as things got more on their way with medication, there was also a desperation for freedom. As we were starting to come out of the AIDS crisis, I was so desperate to create freedom. And I think that if you flip through the pages of Dutch that sense of freedom is definitely there. We were starved for pleasure. Starved for freedom. How could we transmit to people that sense of liberation from fear and repression within the structure of a magazine? That’s what we tried to accomplish.

Vriens seem(ed) to be deliberately pushing the boundaries of what can be published in a magazine. […] For him it is a means of contributing to the gradual dissolution of all manner of habitual and prejudiced ideas about sex and corporeality. (Citation2015, pp. 64–6)

The fashion media discourse that Dutch constructed was a queer one in which the photographic work of Wolfgang Tillmans, Catherine Opie and Collier Schorr was reproduced in reportages such as that on the 1998 Gay Games held in Amsterdam, or in which pieces on ‘dyke style’, drag queens and animal activism were featured alongside rather formulaic reports on runway shows. Looking at Dutch through an intertextual lens, it is noticeable that, in keeping with the semiotic schizophrenia that characterized postmodern fashion discourse, glossy and trashy, fashion and anti-fashion, were enmeshed. Additionally, the sexually exuberant content was packaged in a large-format magazine with an elegant graphic that stood out for its sharp, polished layout, largely informed by Dutch modernist graphic design.

Dutch managed to embed its pages with raw content that could not have been found either in a mainstream gay title or in a glossy fashion magazine. Take for instance the nineteenth issue, which came out in 1999. The monographic title of the issue is ‘Sport’. As a lengthy photographic portfolio of public toilets shows, ‘water sports’ is what the issue is about. The magazine mocked fashion media’s increased attention to fitness and wellness culture as much as its focus on fashion itself. Public toilets have been, historically, spaces for gay encounters, albeit less and less so in the late 1990s when a project of sexual repression and sanitization of urban public spaces enforced by a number of European and American administrations led to the disappearance of informal spaces of sexual and social relations between strangers of different classes and races.Footnote13 Alert to the sociocultural evolution of the LGBTQ community and its concerns, Dutch used its pages to encode queerness into fashion media discourse, showing the inextricable relationship between queer cultures and alternative fashion print cultures, whose audiences were to be found, in both cases, outside of ‘the official publics of the state’ (Berlant and Warner Citation1998, p. 554).

Fashion magazine counterpublics

Jonathan Flatley writes that

in seeing how a particular formal practice addresses itself to a collective of readers whom it is trying to affect, we can also see how it contains a theory of those readers and the historical situation they find themselves in. (Citation2017, p. 144)

According to Michael Warner, books and journals always address an imaginary public: one that is not ‘unreal’ but whose existence depends on the experience of recognizing oneself as being addressed by a text while also sensing that one is not the only addressee (Citation2002, p. 58). From this vantage, a public comes into being only insofar as it finds itself being addressed by a certain discourse: a discourse that is proffered with the presupposition of knowledge of previously existing discourses. The public is not the passive recipient of speech; instead, its members volitionally join in a shared affective atmosphere, or, with Warner’s words, a ‘lifeworld’. Insofar as a public is composed of strangers who share membership by virtue of their affiliation on the level of belief, identity, vocation, or taste, they participate in a social imaginary and therefore come to share a sense of commonality as strangers (Warner, p. 56). Such ‘stranger-relationality’ is predicated on the background assumption of having ‘something’ – usually a sensibility – in common. They involve themselves as strangers in the imaginary uptake of a social world, thereby bringing about a hope for social transformation.

Dutch invited oblique or polemic dispositions towards conventions of beauty, gender, and sexuality by presenting its readers with scenes of disaffiliation from the parameters of the fashionable (i.e. the noteworthy in the context of fashion magazine publishing). Through its queer taxonomy of the anti-fashionable, Dutch made it possible to think of fashion magazine-making and fashion magazine-reading as practices of visual critique towards, and disattachment from, the fantasies of glamour and wealth fostered by the culture of fashion. In this sense, it queered the genre of the fashion magazine. Following Lauren Berlant’s understanding of genre as ‘an aesthetic structure of affective expectation’ (Citation1998, p. 4), I argue that while the fashion magazine has traditionally distinguished itself by making a ‘cruelly optimistic’ (Berlant Citation2011) promise of improvement and transformation to its readers, the affective bind that a magazine like Dutch established with its readers was one of a shared desire to relinquish any promise of self-amelioration and, instead, to expand the discursive field of fashion through a sexually promiscuous attitude.

As Berlant further explained, genres are distinguished by the affective contract they implicitly make with their readers (what Fredric Jameson pessimistically defined a ‘fantasy bribe’ [Citation1979, p. 145]). Dutch created its own ‘minor’ genre: a genre that unsettled the hegemonic fashion imaginary without remaining foreign to it. It promised an intimacy through a shared attunement to, or affiliation with, aesthetic styles and genres of living that did not circulate across fashion culture, while simultaneously winking at and often mocking said culture. The ‘intimate public’ (Berlant Citation2008, p. 19) in which the gay magazine producers and readers of Dutch participated was one in which the life scenarios of usually chastised figures (such as the sex worker, who returns in multiple gender variations throughout the magazine issues) finally appeared as ‘real’ and legitimate, if not desirable or relatable.

While it would not be feasible to prove to what extent Dutch’s publics – which encapsulate what I would refer to as ‘fashion counterpublics’ – discovered a sense of belonging and mutuality in the affective experience of engaging with the magazine, I argue that Dutch had a certain ‘affect theory’ of how its potential audience would consume the magazine. By constructing visual narratives that magnetized a positive attachment to its models-characters, without over-spectacularizing them (i.e. what Guy Debord would have called a process of ‘recuperation’ wherein the capitalist spectacle absorbs and repurposes revolutionary culture to its own ends), it conveyed, in Kantian terms, ‘sensual enjoyment’, and thereby aimed to foster a ‘community of feeling subjects’ which, according to Dana Seitler, reveals a desire for openness, relationality and freedom that grounds queer social collective formations (Citation2014, p. 49). The identification with, or sexual desire for, subjects that had been treated harshly, silenced, or exploited by the state (whether in politics or by the official media channels), offered a space in which to temporarily estrange themselves and their readers from the circuit of ‘national belonging’ (Berlant and Warner Citation1998, p. 550) and make available alternative versions of the present, thereby legitimizing queer experiences and pleasures. It is in this sense that I refer to Dutch as a ‘queer desirous archive’: a repertoire of feeling-images activated through immaterial, affective encounters with the bodies of the readers; a repository of desiring and desirable images that connected models-characters with readers as well as readers with other readers.

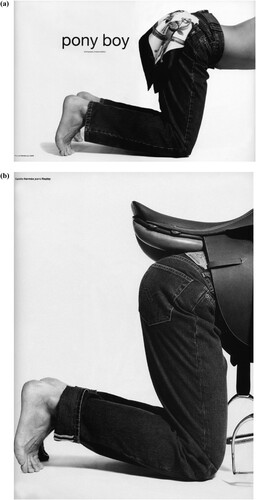

To the extent that Dutch yielded queer energies as a strategy for reconfiguring the visual sphere of fashion, perhaps its success would not have been possible had it completely disavowed the same commercial and institutional frameworks it sought to oppose. As Rita Felski (Citation1998) wrote, books, journals, and magazines can become key instruments in the project of disseminating oppositional ideas and values in the dominant culture; but due to the intermingling of state and society in late capitalism, they cannot fully operate outside commercial and institutional structures if they want to reach a vast audience and alter norms and social patterns. The vernacular style of many of Dutch’s photo stories was frequently in conflict with that of the more traditional pictures often chosen for its covers. By way of example, cover pictures such as of a man’s bare legs wrapped in a faux fur coat for an issue dedicated to animal rights titled ‘Furious!’ ((a)) or of British-Sudanese model-activist Alek Wek shot from the back, on all fours, for the issue ‘Wet wet wet!’ (no. 22, 1999), alternate with standard close-up portraits of popular models (such as Carolyn Murphy and Guinevere Van Seenus) ((b)). Dutch found itself continuously engaging with and reshuffling dominant visual codes: this encapsulates the tension between an oppositional impetus and the institutional market constraints that both Felski and Warner deem integral to the formation of counterpublics. In view of this tension, the editors of Dutch could be seen as having transferred their anxiety about their own relationship with mainstream fashion culture into the very making of the magazine. The friction between a countercultural energy and a desire for broader recognition is managed through what occasionally appears as a contradiction in the visual discourse of the magazine.

Queer counter-moods

The creative personnel of Dutch developed a hybrid discourse, presuming knowledge of and interest in fashion while staging scenes in which the principal actors were those very subjects who had been cast out by the infrastructures of that system. In so doing, it looped its readers into the collective negotiation of their shared ambivalent relationship with the fashion industry and, by extension, with consumer culture. The visual discourse of Dutch could, thus, also be understood as transposing the anxiety about battling the norms of the market onto its photographed subjects. By giving a platform to characters who were, in varied ways, disenfranchized from the world of capital, the magazine enticed its readers to actively contest bodily constraints and moral expectations as well as to consider new modes of socialization and ideo-affective postures. That this was done in the context of a magazine which did not entirely renounce engagement with the fashion system warranted the actual possibility of channelling its messages into society as a whole. The fashion scenes in Dutch could be used by its readers to imagine the world queerly, that is, to envision a world presupposed on an affective dissenting relationship with normativity. Its photo narratives prompted action on the side of the audience: through characters captured in disidentificatory acts, the reader-viewer was called to reimagine the world on alternative groundings.

While disidentification, theoretically (and following Muñoz), consists in non-conventional aesthetic practices leading to ‘otherwise’ modes of being in the world, in practice it also runs the risk of being devoured by the normative, ad-driven, forces of the fashion magazine. In other words, disidentification does not prevent alternative magazines from the constitution of new sets of conventionalities in which subjects can end up trapped. This applies to plenty of allegedly ‘radical’ or ‘anti-fashion’ contemporary fashion magazines; however, I believe it was not the case with Dutch, which, over time, occupied a position of ambivalence in the fashion media market – neither rigidly fixing itself at the margins of the fashion industry nor antagonizing it to the point of becoming obliterated; it thus kept its countercultural potential alive, remained immune to facile categorizations and, with its queer ebullience, crystallized into the fashion mediascape at the turn of the century.

Ben Highmore’s statement that the feelings that drive fashion ‘articulate modes of identity and forms of dis-identification; and they render gender and sexuality as a form of visibility and as shared sets of sensitivities’ (Citation2016, pp. 145–6) applies well in the case of Dutch. The editors and image makers behind the magazine used fashion photo stories and their textual apparatus as tools for mobilizing queer outlooks on the world: they orchestrated scenes of retreat from habitual ways of conforming one’s demeanour to middle-class expectations and from the social imperative to be legible. Dutch embraced and attuned its readers to what Flatley, following Heidegger, calls a ‘counter-mood’: a shift in mood over which the subject can exert a certain degree of agency and which it can intentionally deploy to activate and express a social or political stance (Citation2012, pp. 503–4).

For Heidegger, we are constantly engulfed in moods (that is, in fact, how we affectively move in the world and go about our lives); however, moods are not static: they can be altered as we enter a new situation or when a particular affect impinges upon our bodies generating reactions that, as we cognitively process them, change our mood. Moods are also collective, for affects can be transmitted and can circulate in ways that impact our soma and therefore our social relations.Footnote14 Flatley explains that ‘one way to bring counter-moods into being is by way of what Daniel Stern calls an affective attunement, his term for the way that people share affective states with others’ (Citation2012, p. 504). Whereas the counter-mood I refer to in relation to Dutch is not tantamount to the militant, revolutionary movements that Flatley has in mind, a counter-mood constitutes a sensory shift which causes new attachments to object-worlds: through a mood change we can cathect, and instantiate a relation, to objects (psychoanalytically understood) that disclose an alternative, perhaps utopian, view or experience of ourselves in the world.

I am deploying the concept of counter-mood to argue that while the (queer) readers of Dutch were presumably immersed in a feeling-structure of disaffection from the state apparatus and the visual public sphere due to the harsh treatment they had been likely been subjected to during the (especially early days of) the AIDS epidemic, Dutch facilitated an inversion of their mood, from disillusioned (or even depressed) to hopeful (and joyful).Footnote15 I wager that while the a/political impetus of the magazine was not coherently and consistently oppositional, the mood in which its creators operated, and into which they sought to pull their readers, was. Counter-moods, as Flatley elaborated, can be volitional (for we can make sense of affects, ultimately turning their impact into action). I suggest that in the production of Dutch, its creative entourage affectively attuned the readers to scenes and texts through which they could imagine the formation of a fashion magazine counterpublic: by feeling viscerally drawn to bodies and scenes discarded from fashion and culture at large, they could potentially see themselves as part of a fringe public of critical fashion readers, as well as hope for a different sensitivity, and, ultimately, sensible imaginary. Put differently, Dutch attuned its public to moods of resistance against the neoliberal turn taken by queer politics and championed by the mainstream gay and fashion media, ultimately providing a platform of expression to as well as reflecting an affective community of dissenting queers.

Dutch also encoded a mode of spectatorship that was removed from the viewing-reading habits that are typically associated with the practice of reading fashion magazines (e.g. the desire to embody an ideal image iconized by the models or to achieve a certain status by means of purchasing the products advertised); instead, it enticed the reader to be receptive to the scene’s affective impact, to be curious, to become disoriented, and ultimately to ‘change their mood’ and have fun. Dutch took an important step toward offsetting the fashion magazine’s safeguarding of heterosexual and middle-class values by inspiring a dissenting relationship with those very objects and aesthetics in which the culture of fashion had been historically invested. By developing a language inspired by queer zines, pornography, and documentary photography, and devising rhetorical strategies through which to humorously spotlight the photographic stories, the magazine became an outlet for queer creative expression among international fashion photographers, stylists, and writers.

Conclusion

Its interweaving of seemingly conflicting elements shows how Dutch was both a cultural product and a producer implicated in the negotiation of a social and artistic impetus with commercial demands. With the economic conditions militating against the production of properly independent art and popular culture, engaging with commerce was inevitable for Dutch. Its combination of the highest technical standards of design and photography and a rather ‘trashy’ creative content became recognizable among fashion magazine readers in the 2000s, with numerous contemporary magazines attempting to emulate its aesthetic. Situated as it was in a ‘publishing region located in-between the world of underground zines and that of mass-marketed magazines’ (Andersson Citation2002, p. 8), Dutch managed to become an original point of reference in print fashion cultures.Footnote16

After eight years, due to disagreements between the editor and the publisher tasked with expanding their market, the magazine folded. When Dutch was bought by print media company Audax, the pressure to secure advertisements shrank the creative freedom of the magazine’s editors and contributors. The distinctively awkward eroticism of Dutch was put in jeopardy by the urge to satisfy the expectations of the luxury conglomerates which were encroaching on the fashion editorial publishing market, and the magazine was discontinued just in time, before it could morph into a sanitized, straightened version of itself. In a time of late capitalism in which individuality, choice, and self-determination were promoted as imperative values for progressive fashionability, Dutch offered itself as a repository of queer gestures that pushed the boundaries of fashion representation and connected its readers in their shared disidentification with the dominant fashion imaginary, in the process attuning them to a counter-mood of joyful and humorous resistance.

Pitched as a fashion magazine and dependent on the economy of brand sponsorship but operating on a low or zero budget, replete with references to alternative culture, Dutch sat between queer zine culture and the fashion industry, to which it remained ideologically marginal yet not fully antagonistic. Produced by gay men, the magazine gave expression to some elements of transgressive, explicitly sexual, gay culture that counteracted – although from a not properly minoritarian space, i.e. not delineated and self-promoted as specifically ‘queer’ – the gender and sexual normativity of the 1990s. However, in trafficking in queer aesthetics and attuning its readership to a queer counter-mood of hope for social transformation, it anticipated the contemporary rise of genderqueer, queer-affirmative, and trans representation in the visual culture of fashion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 As Reina Lewis explained, while flicking through fashion magazines ‘queer pleasure’ may arise either in the sensitive act of decoding potentially gay or lesbian subcultural hints offered by the editorials or in the sense of transgression derived from constructing an alternative narrative to what is denoted by the photo spread (Citation1997, pp. 94–6). These identificatory gestures operate by means of recognizing and navigating a certain ambivalence in the images (pp. 107–108). See also Lewis and Rolley (Citation1996). On queer taste and representation in fashion magazines, see Reed (Citation2006). On fashion images and homoerotic fantasies, see Marcus (Citation2003) and Clark (Citation1991).

2 Thanks to the large presence of gay and lesbian creative intermediaries in the production of fashion magazines, these have often managed to attune their non-straight readers to queer sensitivities that go unpicked by the larger readership. As Elspeth H. Brown (Citation2019) has recently brought to the fore, queer networks of photographers, editors, and models have been crucial in shaping the visual culture of fashion.

3 The preoccupation with sexuality in 1990s fashion magazines and their emphasis on erotic content can be read in view of phenomena such as post-feminism, the AIDS crisis, the proliferation of gay and sexuality studies, the correlation between a new male consumerist ethos and the redefinition of masculinities, and the ‘culture wars’ that created further polarization on matters of abortion, immigration, privacy, censorship, gay and lesbian rights and drug use. On fashion and sexuality in the 1990s, see Jobling (Citation1999) and Craik (Citation1994).

4 With ‘alternative’ fashion magazines, I refer to magazines that are not owned by global mass media companies and that are often, at least partly, self-funded but not fully independent of the fashion industry, from which they receive advertisements.

5 By way of example, the Dutch edition of Harper's Bazaar ran from 1986 to 1990, and Vogue Nederland has been published only since 2012. Avenue was the leading women's magazine (and one of very few) in the Netherlands. It was founded in 1965 as a lifestyle magazine that would inject an attitude of carefreeness in the post-war years by paying attention to art, fashion, literature, travel, food, and social and political developments. Within a context of sweeping social changes such as economic growth, reduction in family size, democratization, and secularization, Avenue was an important channel through which ‘the stuffy, hidebound and thrifty Netherlands of the post-war reconstruction years was introduced to more modern customs and traditions’ (Lamoree Citation2015, p. 29).

6 On Dutch LGBTQ activism and the normalization of sexual discourse in the Netherlands, see Hekma (Citation2004).

7 The ‘Dutch gay-interest fashion magazine printed on pink paper’ BUTT (2001-), founded by Jop van Bennekom and Gert Jonkers, ‘aimed to make a virtue of the number of gay creatives involved in the fashion world, promoting a European aesthetic for making queer sensibilities visible in fashion photography that veered away from the look of American hetero “porno chic”’ (O’Neill Citation2017, p. 89). Grittily displaying the naked bodies of scruffy and average-looking men of all ages (be they well-known artists, designers, porn actors, or strangers met in a club), accompanied by amusingly raunchy interviews revolving around personal sex anecdotes, BUTT absorbed Dutch’s queering of the fashion editorial genre to create a kink anthology that trespassed editorial genres.

8 As Vriens accurately states, it was only ‘partially’ ‘multi-cultural’, insofar as despite its intersectionality on the level of class and sexuality, its visual narratives remained predominantly white. Models of colour are featured in Dutch more frequently than in other fashion magazines from the same period; nevertheless, like 1990s queer popular culture as a whole, it did not offer a major platform of expression to racialized minorities. On the whiteness of 1990s queer popular culture, see Cavalcante (Citation2018).

9 This is testified by the emergence of Paris-based publications like Purple (1992-) and Self Service (1993-), which depicted ‘models in simpler poses, often frankly naked instead of sculpturally nude […] and often in an everyday setting instead of a photographer’s backdrop’ (Rian Citation2002, p. 124).

10 As Gayle Rubin notably explained (Citation2011), the panic surrounding children's sexuality served the purpose of moralizing sexual object; in other words, the public affective mobilization in defense of children's innocence mirrored the state's intervention to normalize sexuality.

11 On ‘misrecognition’, see Butler (Citation1996) and Ahmed (Citation2004).

12 On ‘trade’, i.e. the stereotype of men who do not identify as gay but are open to having sex with other men (often in exchange for money) see Chauncey (Citation1995) and Muñoz (Citation1998).

13 It is not a coincidence that Samuel Delany’s queer classic Time Square Red, Time Square Blue (Citation1999) had been published a few months before the release of this issue.

14 On fashion and mood, see Findlay (Citation2022), Parkins (Citation2021); Sheehan (Citation2018).

15 On ‘structure of feeling’, see Williams (Citation1977, p. 134). In my understanding, this concept describes how a set of social changes in a precise historical situation can manifest itself in the attitudes of a given group of people, formally registering as (shifts in) manners, language, dress, or style. Jonathan Flatley glosses Williams’ ‘structure of feeling’ as

the mediating structure – one just as socially produced as ideology – that facilitates and shapes our affective attachment to different objects in the social order. […] When certain objects produce a certain set of affects in certain contexts for certain groups of people – that is a structure of feeling. (Citation2008, p. 26)

16 Its legacy is evidenced in a plethora of fashion magazines that emerged in the early 2000s. These range from the more ‘niche’ Northern-European fashion publications, such as the Danish Dansk, whose name is a direct reference to Dutch (Lynge-Jorlén Citation2017), to the more profit-oriented French and British ones (such as Vogue Hommes International and Love).

References

- Ahmed, S., 2004. The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Aletti, V., 2019. Issues: a history of photography in fashion magazines. London: Phaidon Press.

- Andersson, P., 2002. Beyond magazines. In: P. Andersson and J. Steedman, eds. Inside magazines: independent popular culture magazines. London: Thames & Hudson, 14–19.

- Berlant, L., 2008. The female complaint: the unfinished business of sentimentality in American culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Berlant, L., 2011. Cruel optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Berlant, L. and Warner, M., 1998. Sex in public. Cultural inquiry, 24 (2), 547–566.

- Brown, E.H., 2019. Work! A queer history of modeling. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Butler, J., 1996. Bodies that matter: on the discursive limits of sex. London and New York: Routledge.

- Cavalcante, A., 2018. Struggling for ordinary: media and transgender belonging in everyday life. New York: NYU Press.

- Chauncey, G., 1995. Gay New York: gender, urban culture, and the making of the gay male world, 1890–1940. New York: Basic Books.

- Clark, D., 1991. Commodity lesbianism. Camera obscura, 9 (1–2), 181–201.

- Craik, J., 1994. The face of fashion: cultural studies in fashion. London: Routledge.

- Dasgupta, S., 2008. Art is going elsewhere and politics has to catch it: an interview with Jacques Rancière. Krisis: journal for contemporary philosophy, 9 (1), 70–76.

- de Perthuis, K. and Findlay, R., 2019. How fashion travels: the fashionable ideal in the age of Instagram. Fashion theory, 23 (2), 219–242.

- Delany, S.R., 1999. Times square red, times square blue. New York: NYU Press.

- Dyer, R., 1993. The matter of images: essays on representation. London: Routledge.

- El-Tayeb, F., 2012. Gays who cannot properly be gay: queer Muslims in the neoliberal European city. European journal of women’s studies, 19 (9), 79–95.

- Felski, R., 1998. Beyond feminist aesthetics: feminist literature and social change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Findlay, R., 2022. Fashion as mood, style as atmosphere: literary non-fiction fashion writing on SSENSE and in London Review of Looks. In: R. Findlay and J. Reponen, eds. Insights on fashion journalism. London: Routledge, 146–159.

- Flatley, J., 2008. Affective mapping: melancholia and the politics of modernism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Flatley, J., 2012. How a revolutionary counter-mood is made. New literary history, 43 (3), 503–504.

- Flatley, J., 2017. Reading for mood. Representations, 140 (1), 137–158.

- Fuss, D., 1991. Fashion and the homospectatorial look. Critical inquiry, 18 (4), 713–737.

- Gaugele, E., 2014. Alternative aesthetic politics. In: E. Gaugele, ed. Aesthetic politics in fashion. Berlin: Sternberg, 10–17.

- Hekma, G., 2004. Queer: the Dutch case. GLQ, 10 (2), 276–280.

- Herring, S., 2006. Caravaggio's rednecks. GLQ, 12 (2), 217–236.

- Highmore, B., 2016. Formations of feelings, constellations of things. Cultural studies review, 22 (1), 145–146.

- Highmore, B., 2017. Cultural feelings: mood, mediation and cultural politics. London: Routledge.

- Jameson, F., 1979. Reification and utopia in mass culture. Social text, 1, 130–148.

- Kagan, D., 2018. Positive images: gay men & HIV/AIDS in the culture of ‘post-crisis’. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Jobling, P., 1999. Fashion spreads: word and image in fashion photography since 1980. Oxford: Berg.

- Lamoree, J., 2015. The future on a string: how Dutch fashion photographers went from being trailers to trailblazers. In: J. Teunissen, ed. Everything but clothes: the connection between fashion photography and magazines. Arnhem: ArtEZ Press and Terra Lannoo, 27–33.

- Lewis, R., 1997. Looking good: the lesbian gaze and fashion imagery. Feminist review, 55 (1), 94–96.

- Lewis, R. and Rolley, K., 1996. Ad(dressing) the dyke: lesbian looks and lesbian looking. In: P. Horne and R. Lewis, eds. Outlooks: lesbian and gay sexualities and visual cultures. London: Routledge, 392–418.

- Lynge-Jorlén, A., 2017. Niche fashion magazines: changing the shape of fashion. London: Bloomsbury.

- Marcus, S., 2003. Reflections on victorian fashion plates. Differences, 14 (3), 4–33.

- McRobbie, A., 1998. British fashion design: rag trade or image industry? London: Routledge.

- McRobbie, A., 2008. The aftermath of feminism: gender, culture and social change. London: Sage.

- Muñoz, J.E., 1998. Rough boy trade: queer desire/straight identity in the photography of Larry Clark. In: D. Bright, ed. The passionate camera: photography and bodies of desire. New York: Routledge, 167–177.

- Muñoz, J.E., 1999. Disidentifications: queers of color and the performance of politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- O’Neill, A., 2017. The cult of walter pfeiffer. Aperture, 228, 85–94.

- Parkins, I., 2021. You’ll never regret going bold’: the moods of wedding apparel on a practical wedding. Fashion theory, 25 (6), 799–817.

- Probyn, E., 1996. Outside belongings. London: Routledge.

- Rancière, J., 1992. Politics, identification, and subjectivization. October, 61, 58–64.

- Reed, C., 2006. Design for (queer) living: sexual identity, performance, and décor in British vogue, 1922–1926. GLQ, 12 (3), 377–403.

- Rian, J., 2002. Close to you. In: P. Andersson and J. Steedman, eds. Inside magazines: independent popular culture magazines. London: Thames & Hudson, 120–129.

- Rubin, G.S., 2011. Thinking sex: notes for a radical theory of the politics of sexuality. In: G. Rubin, ed. Deviations: a Gayle Rubin reader. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 137–181.

- Seidman, S. and Richardson, D., 2002. Introduction. In: S. Seidman and D. Richardson, eds. Handbook of lesbian & gay studies. London: Sage, 1–12.

- Seitler, D., 2014. Making sexuality sensible: Tammy Rae Carland and Catherine Opie’s queer aesthetic forms. In: E.H. Brown and T. Phu, eds. Feeling photography. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 47–70.

- Sheehan, E., 2018. Modernism à la mode: fashion and the ends of literature. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Shinkle, E., 2008. Interview with Rankin. In: E. Shinkle, ed. Fashion as photograph: viewing and reviewing images of fashion. London: I. B. Tauris, 87–99.

- Smelik, A., 2006. The Netherlands: filmmaking and television. In: D.A. Gerstner, ed. The Routledge international encyclopedia of queer culture. London: Routledge, 420–422.

- Smelik, A., 2017. Introduction: the paradoxes of Dutch fashion. In: A. Smelik, ed. Delft blue to denim blue: contemporary Dutch fashion. London: I. B. Tauris, 2–26.

- Teunissen, J., 2015. Introduction. In: J. Teunissen, ed. Everything but clothes: the connection between fashion photography and magazines. Arnhem: ArtEZ Press and Terra Lannoo, 6–15.

- Tulloch, C., 2010. Style–fashion–dress: from black to post-black. Fashion theory, 14 (3), 273–303.

- Vänskä, A., 2017. Fashionable childhood: children in advertising. London: Bloomsbury.

- Warner, M., 2002. Publics and counterpublics. Public culture, 14 (1), 49–90.

- Warner, M., 1993. Fear of a queer planet: queer politics and social theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Williams, R., 1977. Marxism and literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, E., 1992. Are you man enough? Independent on Sunday review, 29 March, p. 36.