Abstract

Why has there been no jihadist civil war in Southeast Asia? Although there has been a global surge in armed conflicts where at least one side fights for self-proclaimed Islamist aspirations, the region of Southeast Asia stands out by not having experienced a single jihadist civil war after 1975. Yet, so far, there have been no systematic comparisons of the frequency and nature of the Islamist violence in Southeast Asia and the rest of the world. This study therefore contributes by exploring the empirical trajectories in the region and situating Southeast Asia to global developments, utilizing new and unique data on religiously defined armed conflicts 1975–2015. We find that whereas the number of people killed in Islamist violence has increased in the rest of the world, it has decreased in Southeast Asia. We argue that Southeast Asia has prevented outbreaks of jihadist civil wars, and contained and partially resolved ongoing Islamist conflicts before they have escalated, due to three interrelated factors: the lack of internationalization of Islamist conflicts in the region, the openness of political channels for voicing Islamist aspirations, and government repression. This article suggests insights from the region that can be valuable from a global perspective.

Introduction

The Muslim areas of Southeast Asia have often been described as fertile ground for the expansion of global jihadism. Indonesia is the largest Muslim country in the world, and Southeast Asia includes two other Muslim majority countries: Malaysia and Brunei. The region also includes four countries with geographically concentrated Muslim minority populations, where armed insurgencies have emerged: Thailand's southernmost provinces (Patani), Mindanao and the Sulu islands (Bangsamoro) in the Philippines, Aceh in Indonesia, and northern Rakhine state in Myanmar, which is home to the disenfranchised Rohingya. Transnational jihadist groups have made efforts to internationalize Muslim rebellions in several of these areas and place them on the global scene. After 9/11, security analysts and scholars predicted that Southeast Asia would become a second front in the war on international jihadist terrorism (Abuza, Citation2003; Gershman, Citation2002).

Yet, as we will show, over four decades, Southeast Asia – in stark contrast to Islamist uprisings in other world regions – has not witnessed one single year of major armed conflict with a jihadist group. Although Southeast Asia has not been spared from minor armed conflicts with jihadist or nationalist-Islamist insurgents, these conflicts have been contained and prevented from further escalation. This article will substantiate the empirical fact of the absence of jihadist civil war in Southeast Asia since 1975, and try to explain it. There is a debate about the nature and context of Islamist violence in Southeast Asia, in which some focus on the risk, prevalence, and persistence of Islamist violence in the region (Abuza, Citation2003; Gershman, Citation2002; Gunaratna, Citation2005, Citation2016; Singh, Citation2007), while others point out that Islamist violence in the region tends to differ from other world regions (Liow, Citation2006a, Citation2006b; Sidel, Citation2007, Citation2009). Whereas our argument is definitely in line with the latter side of this debate, our study contributes to the debate in two ways. The debate so far has been based on thick historical analysis, but without systematic comparisons to other regions or global trends. Empirical evidence about the increase or decrease and about the character of Islamist violence has, so far, largely been anecdotal. Empirically, this study therefore contributes as the first systematic comparison that both substantiates the absence of jihadist civil war in Southeast Asia and shows the empirical differences and similarities of Southeast Asia to the global patterns of armed conflicts. Second, it offers a comprehensive explanation for the lack of jihadist civil wars, building on previous research.

Our argument presumes that decisions about civil war involve two actors: governments and insurgents. It is important to take both sides into account when attempting to explain the lack of jihadist wars in Southeast Asia. We argue that the absence of jihadist civil war in Southeast Asia can be explained by three interrelated factors. The first is the lack of internationalization of Islamist conflicts in the region. Since 1975, Southeast Asia has seen no jihadist or nationalist-Islamist conflict where external state actors have intervened with troops on one or both sides.Footnote1. Governments have retained domestic control over their counterinsurgency campaigns, and rebels have chosen, for historical and strategic reasons, to distance themselves from pan-jihadist networks and focus on their local agendas. The second is the opening of political channels for voicing Islamist aspirations. Governments have created alternative, political routes for less radical actors with Islamist aspirations to participate through the ballot-boxes and in civil society, and engaged in peace negotiations with some of the violent armed groups. The third is repressive policing by Southeast Asian regimes and transregional collaboration against the most radical and violent jihadist networks. In combination, we argue, these factors have contributed to prevent jihadist conflicts from breaking out, and to contain and resolve minor conflicts with militant Islamists before they have escalated.Footnote2. In short, this study helps to empirically substantiate the claim by Sidel (Citation2007, p. 7) that ‘not simply what little violence has occurred, but also how violence has not, cries out for explanation’. We wish to clarify that what we offer here is an explanatory framework, and we invite future research to test it empirically. Such a test would require a more thorough process-tracing method as well as a more careful comparison with other regions where jihadist civil wars have occurred and where the independent variables we propose have taken opposite values.

Our claims are based on the RELAC data (Svensson & Nilsson, Citationin press),Footnote3. which utilizes new and unique data on armed conflicts from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), focusing on the time period 1975–2015. The study presents new empirical findings regarding patterns of Islamist armed conflicts. Whereas the number of people killed in Islamist violence has increased in the rest of the world, it has decreased in Southeast Asia. In 2015, Southeast Asia stood for only 0.54 percent of all battle-related deaths in armed conflicts that include Islamist armed groups. Whereas Southeast Asia had 13 percent of all the world's armed conflicts with jihadist or nationalist-Islamist insurgents, it had no such civil wars. Globally, civil wars including Islamist rebel groups have become the most common type of major organized violence: in 2015, 73 percent of all civil wars involved an Islamist group on one side in the conflict. Meanwhile, Southeast Asia has not seen a single jihadist civil war since 1975.

It is well known and established that the clash between religious aspirations and state secularism has been the main global schism after the Cold War (Juergensmeyer, Citation1993, Citation2008; Toft et al., Citation2011). Whereas other types of conflicts have decreased in frequency over time, religiously defined conflicts have remained prevalent. The proportion of religiously framed conflicts of all conflicts has, thus, undergone a quite dramatic increase (Nordås, Citation2010; Pinker, Citation2011; Svensson, Citation2012; Toft, Citation2006). And as we will show, the majority of religious conflicts today are Islamist.

Here we distinguish between ‘jihadist’ and ‘nationalist-Islamist’ conflicts. Jihad is a complex concept: to most Muslims it is a non-violent, inner spiritual struggle, but it also has a violent interpretation which refers to military action, or ‘holy war’ (see, for instance, Cook, Citation2005). This paper focuses on the latter category – the term ‘jihadist’ is reserved for a certain type of violent conflicts. Jihadist conflicts are those where at least one side is a Sunni Muslim group which adheres to a Salafi-jihadi ideology and uses armed force, including against civilians, to achieve self-defined Islamist political ambitions which constitute its main demand at the onset of conflict. Jihadist civil wars are therefore major armed conflicts that include groups with a Salafi-jihadist ideology as their overarching worldview, rather than as an ideological component of an erstwhile nationalist or political ideology. This is an important characteristic separating jihadist from what could be called ‘nationalist-Islamist’ actors.Footnote4. For nationalist-Islamists, religious concerns of an Islamist nature may be important, but they are usually mixed with, and do not take precedence over, nationalist, political, or other ‘non-religious’ goals. Their religious aspirations, although present and explicit, thus occupy a limited space and, in contrast to jihadists, they typically have less abstract goals and worldviews.Footnote5. While this definition of jihadist conflicts is narrow in that it excludes groups that also hold Islamist political aspirations but that do not qualify as ‘jihadist’, it is in line with previous research on the subject (see, for example, Hegghammer, Citation2011; Moghadam, Citation2009; Toft & Zhukov, Citation2015). Moreover, whereas our focus is on the absence of jihadist civil wars, we still make reference to the several nationalist-Islamist conflicts in Southeast Asia. As seen in, for instance, Chechnya where the ‘Caucasus Emirate’ has replaced the ‘Chechen Republic of Ichkeria’, initially nationalist rebellions can over time take on a jihadist nature. Similarly, in Syria, the civil war first spearheaded by the secular Free Syrian Army has become increasingly jihadist of late, as groups like Islamic State (IS) and Jabhat Fateh al-Sham have emerged. Therefore, we examine why the nationalist-Islamist conflicts in Southeast Asia have not escalated in terms of intensity and aspirations, as they have elsewhere in the world.

Why would we expect jihadist civil wars in Southeast Asia?

We argue that there are four major reasons for why one would expect jihadist civil wars in Southeast Asia. The first reason is the relative prevalence of significant grievances amongst Muslim minorities in the region. In southern Thailand, government efforts to impose Thai (Buddhist) language and traditions in the Malay-Muslim provinces have met violent resistance, and is one of the main drivers of the armed conflict there (Liow, Citation2006b). In Mindanao of the southern Philippines, local Muslim populations have long been marginalized by the central government. Nationally, the region has the lowest score on several key human development indicators. Furthermore, Muslims in Rakhine state in Myanmar are socially and politically marginalized, and in Aceh, the local population has long held grievances against the central government.Footnote6.

Second, there is a significant literature, written mainly by international terrorism experts and country-specialists, highlighting Southeast Asia as a potential focal point of international jihadism (see Abuza, Citation2003). Scholars and analysts in this field have long predicted the region to become an arena for jihadist groups and violent conflicts. After the 9/11 attacks, the Bali bombings in 2002, and during the hunt for the leaders of Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), many argued that Southeast Asia would emerge as the second front in the global war against violent jihadist networks (Gershman, Citation2002).

Third, Southeast Asia has experienced a rising trend of Islamism in general, and support for radical interpretations of Islam in particular. This has manifested itself in an increase in religious commitments among populations; in more explicit public expressions of Islam; and in more religiously anchored political aspirations (Hamayotsu, Citation2013). Related to this, religious minorities in the region are increasingly prosecuted on charges of blasphemy (Crouch, Citation2012).

Lastly, there have been several attempts to escalate ongoing conflicts and internationalize them into the broader, global dynamics of pan-jihadist confrontations. Al-Qaeda has had ties with several groups in the region, including JI in Indonesia and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) in the Philippines (Gunaratna, Citation2005; Liow, Citation2006b; Read, Citation2012). The leaders of these groups also sent their recruits to Afghanistan to fight the Soviets, where they encountered ideas about global jihad and gained military and terrorism experience (Oak, Citation2010). And in current times, IS attempts to gain a foothold in the region. Some of the actions taken by Southeast Asian governments have also risked escalating and internationalizing ongoing conflicts. For example, the Philippines has received training and support from the United States to boost its counterinsurgency efforts against ASG (Cronin, Citation2009). The United States, together with Australia, has also funded, equipped, and trained Indonesia's elite counterterrorism squad, Detachment 88 (D88), which was successful in capturing hundreds of JI leaders after the Bali 2002 bombings (Oak, Citation2010). Given the trajectory in other parts of the world, training and intervention by the United States and other Western countries in counterterrorism can provoke resistance against the West and thereby internationalize conflicts.

The lack of jihadist civil wars in Southeast Asia

We have outlined above the four reasons that lay behind expectations of Southeast Asia to be a particularly risk-prone region for jihadist civil wars. However, as we will now show, Southeast Asia has not seen a single jihadist civil war between 1975 and 2015. This differentiates the region from how Islamist violence has unfolded elsewhere in the world. Critics would say that the absence of jihadist civil wars in Southeast Asia is unsurprising because such wars mostly happen in Muslim-majority countries, of which there are few in this region. Yet, while jihadist civil wars are indeed most common in Muslim-majority countries, Muslim-minority or, more specifically, Sunni Muslim-minority countries have also seen jihadist civil wars (e.g. Iraq and Nigeria). Moreover, jihadist minor conflicts have occurred in several other countries where Sunnis are a minority (e.g. India and Russia). We have also listed several risk factors for jihadist civil wars in Southeast Asia. Another possible objection is that the absence of jihadist civil war is simply a consequence of the decline of civil wars in general in the region. Yet, civil wars overall have become less common also in other world regions with significant Muslim majorities or minorities, but there we have still seen a relative increase in jihadist civil wars. We thus maintain that the lack of this form of major political violence in Southeast Asia is puzzling and deserves further scrutiny.

Let us first have a brief look at some global and regional trends regarding religious and non-religious armed conflicts since 1975, utilizing the RELAC data-set (Svensson & Nilsson, Citationin press). Of these religiously defined conflicts, we zoom in on a sub-category: those armed conflicts in which at least one side has had explicit and self-proclaimed Islamist aspirations at the onset of the conflict. Moreover, this article employs the UCDP definition of ‘armed conflict’, namely ‘a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, results in at least 25 battle-related deaths in one calendar year’. ‘Civil wars’ (or ‘major armed conflicts’), then, are internal state-based conflicts with at least 1,000 battle-related deaths per calendar year (UCDP, Citation2016). A limitation of this study is thus that it does not take into account jihadist conflicts between non-state actors or attacks on civilians by jihadist groups that may have produced over 1,000 battle-deaths in one year. Another limitation is that we do not compare the pre- and post-1975 time periods, and thus do not take into account jihadist civil wars that may have occurred in Southeast Asia before 1975. Our argument is focused solely on the post-1975 time period.

The centrality of religion to the parties – whether religious aspirations are central or partial in parties’ stated demands – is important to take into account. It can be a fruitful way to classify religious conflicts (Nordås, Citation2010), and determining whether a space is perceived as indivisible (Hassner, Citation2009). The centrality of religion represents an important variation in conflicts with a religious dimension to the incompatibility.

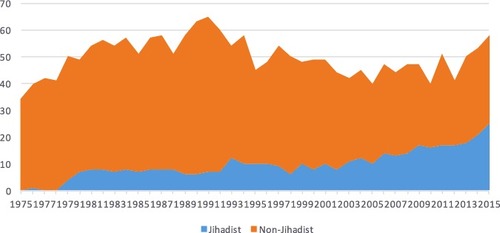

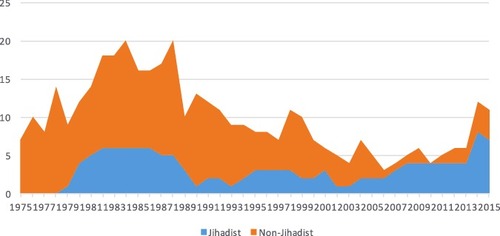

Applying these analytical categorizations, displays the number of actor-dyads globally involved in jihadist versus other types of armed conflicts 1975–2015.Footnote7. The graph illustrates how jihadist armed conflicts have in general occurred at a lower level compared to other types of conflicts. Yet, as a share of all conflicts, jihadist armed conflicts have increased significantly. In 1975, there were no jihadist conflicts. In 2015, however, their proportion had soared to 43 percent. This dramatic rise over time is mainly due to the combination of a long-term decrease in the frequency of other types of conflicts, but also, particularly during the very last years, because of an increase of jihadist armed conflicts in absolute numbers.

In , the analysis is narrowed down to focus on the number of jihadist civil wars versus other types of civil wars in the world between 1975 and 2015. This graph shows a similar development as that in , but a more dramatic one. Since 2000, the majority of civil wars in the world have been jihadist. Of the 11 civil wars active in 2015, 7 (or 64 percent) included a jihadist insurgent group.

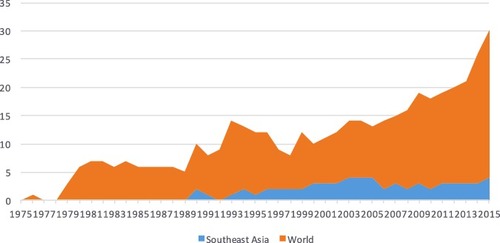

These global patterns create a useful context for situating the development of armed conflicts in Southeast Asia. Given that Islamist conflicts have come to dominate the global scene of major political violence, what is the situation in Southeast Asia? Whereas jihadist and nationalist-Islamist conflicts have occurred at a relatively constant frequency over time in the region – varying mostly between 2 and 4 per year since 1990 – they have not increased as dramatically there as in the rest of the world over the last decade. illustrates the development in Southeast Asia in relation to the rest of the world. The two curves display the number of jihadist and nationalist-Islamist conflicts – essentially, all conflicts over Islamist claims – per region.

Thus, Southeast Asia stands out from the global trajectory of Islamist violence. In fact, the region has not witnessed a single jihadist civil war since 1975, although there have been five conflicts over Islamist claims. The Philippine conflict with ASG (the Southeast Asian insurgents which may come closest to the ‘jihadist’ label) has remained at minor intensity. MILF, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Movement (BIFM), the Free Aceh Movement (GAM), and the Patani insurgents of southern Thailand have all fought with their governments, but these conflicts have never – except for the year 2000 in the Philippines-MILF conflict when fighting produced an estimated 1,055 battle-deaths (UCDP, Citation2016) – escalated to civil war. These groups are not ‘jihadist’ in the sense that we use the concept here. They may have contained some radical elements but their Islamist-styled demands (while never trivial) are best understood as one component in larger nationalist-Islamist struggles, rather than as the only or foremost demand such as for groups like IS and Al-Qaeda. This distinction is illustrated by Piazza (Citation2009), who separates between ‘universal/abstract’ and ‘strategic’ armed groups. In his view, the former have highly abstract goals driven primarily by ideology. Their constituent communities, to which they often have more symbolic ties, are typically transnational and ideologically constructed. Strategic groups instead have more limited and concrete goals, such as creating an independent homeland for a specific ethnic group. They have coherent and narrowly defined constituents, on whose behalf they fight and upon whom they depend for support. Using this distinction, he categorizes GAM and MILF as strategic groups. Similarly, Abuza (Citation2016a) describes GAM, MILF, and Malay-Muslim groups in southern Thailand as mainly ethno-nationalist, but with strains of Islamist ideology. They all claim to represent the interests of very specific populations, within and outside the context of negotiations.Footnote8.

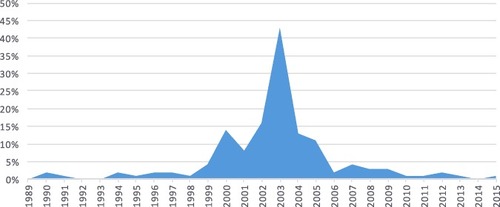

Despite a number of violent terrorist attacks in Southeast Asia, most notably the October 2002 blasts in Bali and the February 2004 ferry bombing in Manila Bay, jihadist groups relying mainly on terrorism have not challenged Southeast Asian governments through more conventional warfare. JI is a case in point. Once Southeast Asia's most violent jihadist terrorist network with a regional presence, it has not carried out any major violent attacks since the 2009 assaults on the Ritz Carlton and J. W. Marriott hotels in Jakarta. Hundreds of JI leaders and members have been arrested and the group's current strength is unclear (Oak, Citation2010). There is, however, growing concern over the possible reach of IS into Indonesia, embodied most notably by the attack in Jakarta on 14 January 2016, perpetrated by militants loyal to IS (Abuza, Citation2016b). It is also feared that IS is setting up a province of the caliphate in Southeast Asia (Gunaratna, Citation2016). Yet, the alarmist accounts can be balanced with empirical patterns. We can discern (see ) that Southeast Asia's share of all Islamist violence worldwide has decreased over time. In 2015, the region stood for only 0.54 percent (457 battle-deaths) of all Islamist violence in state-based armed conflicts.

Explaining the absence of jihadist civil war in Southeast Asia

This study offers an explanation for the absence of jihadist civil wars in Southeast Asia. What is puzzling here is that religion has, on the whole, played a very different role in Southeast Asian religious conflicts compared to those in other world regions. The relative peacefulness of Southeast Asia in terms of avoiding jihadist civil wars requires an explanation. We suggest an explanation for the absence of jihadist civil wars in the region based on three components: the lack of internationalization of Islamist conflicts; the creation of political channels for Islamist aspirations; and the repressive counterterrorism tactics of the governments in the region.

Lack of internationalization

None of the religious armed conflicts in Southeast Asia since 1975 has been internationalized. While there may have been some low-scale government-to-government collaboration, the region has seen no religious conflict where at least one of the belligerents has received troop support from an external state. This is illustrated in below, and differs from the experiences of several other world regions. It also stands out from the global trend of recent years which displays an increase in internationalized armed conflicts (Melander et al., Citation2016).

Table 1. Internationalized religious conflicts, conflict-dyads by region, 1975–2015.

Whereas one third of all religious conflicts in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East have been internationalized, the seven religious conflicts in Southeast Asia during the time period (all but one Islamist) have remained non-internationalized. Had Southeast Asia instead followed the pattern of these other three regions, it would have seen two internationalized religious conflicts. Unlike Central and South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, Southeast Asia has had no major military interventions by external powers in religiously defined conflicts, through air- and drone strikes, ground troops, etc. Governments in the region have largely retained domestic control over their counterinsurgency campaigns.Footnote9.

There has been no internationalization on the rebel side either. This concerns an additional variable to the absence of troop support from an external state, namely so-called ‘trans-jihadization’. Despite internal and external efforts to link Islamist conflicts in Southeast Asia to transnational jihadist networks, militants in the region have largely resisted trans-jihadization. Armed rebellions in Muslim-minority countries in the region have remained focused on their local contexts. Even though the conflict in southern Thailand has become increasingly marked by religion, there is little evidence of links to either radical pan-Islamic ideologies or global jihadist networks. The southern Thai insurgency remains distinct from transnational jihadist movements, anchored in Malay-Muslim nationalism and separatism as well as in Bangkok's misguided responses to the violence (International Crisis Group, Citation2015; Liow, Citation2006a). Likewise, although Osama bin Laden once referred to the southern Philippines as an arena in which the international jihad should be pursued, major Muslim insurgent groups in the area have remained focused on their local agendas. For example, after 9/11 MILF leaders sought to distance their group from Al-Qaeda and JI. In 2003, then MILF leader Salamat Hashim authored a private letter to President George W. Bush, stressing his group's repeated renunciation of terrorism and its principal aim of ‘securing safety of the life and properties of the Bangsamoro people’ (Liow Citation2006b, p. 21).

ASG may be distinguished from other Muslim insurgent groups in Southeast Asia in this regard. Its fight for an Islamic state in the southern Philippines has had a transnational character, as part of a global struggle for Islam. ASG is thought to have received funding and training by Al-Qaeda in the 1990s, and later on it may have benefited from operational and monetary support by jihadist terrorist group JI (Fellman, Citation2011). Most recently, ASG has pledged allegiance to IS. The group may thus be an exception from the larger Southeast Asian pattern of absent trans-jihadization. It should though be noted that ASG is nowadays often portrayed as a criminal rather than jihadist group following its growing emphasis on kidnappings-for-ransom and other criminal activities.

Trans-jihadization has been largely absent from conflicts in Muslim-majority countries as well. The conflict in Aceh, Indonesia, remained localized and never reached the intensity of civil war. Although some GAM guerrillas received military training in Libya in the late 1980s and returned home to educate other recruits, the group never swayed from its local focus and goal: Acehnese independence, rather than building a transnational Islamic state. Important characteristics of its mainly national liberation ideology, then, were Acehnese ethnic nationalism but also Islam (Schulze, Citation2004).

The section above has outlined the lack of internationalized religious conflicts in Southeast Asia. But does internationalization matter for conflict intensity? In , we compare the intensity levels of internationalized versus non-internationalized religious conflicts. Here we distinguish between minor and major armed conflict. The table covers all religious conflicts in the world since 1975.

Table 2. Conflict intensity in religious conflicts, conflict-dyad-years by region, 1975–2015.

Judging by these global figures, non-internationalized religious conflicts are very unlikely to escalate to war. In the vast majority (81 percent) of those years where belligerents were engaged in non-internationalized religious conflicts, the conflicts were of minor intensity. Internationalized religious conflicts, on the other hand, were as likely to be major as minor. This supports our argument that the lack of internationalization of jihadist and nationalist-Islamist conflicts in Southeast Asia has played a role in preventing them from escalating to jihadist civil wars. The figures also resonate with findings that conflicts tend to be more severe when they are internationalized (see Lacina, Citation2006).

Political channels for Islamist aspirations

The second explanation for the absence of jihadist civil war in Southeast Asia is institutional openness for both civil society and political organizations to raise Islamist aspirations. Manifested most clearly in Muslim-majority countries in the region, this has created alternative channels to pursue political ambitions, helped to moderate demands, and given stakes to Islamist political actors, who then have had incentives to challenge too radical interpretations of Islam. Political parties but also civil society organizations have been given space to participate (Freedman, Citation2009). The constitutional frameworks of particularly Malaysia and Indonesia have created democratic space in which Islamist movements have been able to mobilize and channel their political ambitions, which has reduced the appeal of militant movements. This separates the contextual environment and incentive structures for Islamists in Southeast Asia from, for example the Middle East, Central Asia and North Africa (Liow, Citation2015). Southeast Asian states may have preempted the emergence of strong jihadist groups by becoming far more Islamist themselves, adopting certain Islamic laws and targeting alleged heretics (such as the Ahmadya minority).

Liow describes how Islam has played an important role in Indonesian politics since independence in 1945. While political Islam was largely marginalized by Presidents Sukarno (1959–1965) and Suharto (1966–1998), it was gaining influence by the end of Suharto's era, when the regime began collaborating with Muslim leaders (Liow, Citation2015). During the last decade of Suharto, he even started encouraging political Islam. He supported the creation of an Islamic bank, gave greater power to Muslim courts, removed the prohibition on the veil in schools, increased funding to Muslim schools, and recruited conservative Muslims as leaders in the military. Suharto also accommodated Muslim civil society organizations, such as the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) (Hefner, Citation2000). As the world's largest Muslim organization, with an estimated 50 million members, NU has promoted democracy and tolerance and strongly opposed extremist ideologies (Cochraneov, Citation2015). The space given to social movements such as the NU may be an important factor to understanding why jihad has, in relative terms, failed in Indonesia.

The introduction of free elections in 1999 allowed Islamist parties access to the political process. For example, the Justice and Prosperity Party (PKS), the Crescent and Star Party, and the United Development Party, have all participated in elections since. With the arrival of democracy in Indonesia after 1998 the country has made greater strides to incorporate sharia principles into national laws.Footnote10. In 2003, religious teaching was made compulsory in schools. In 2006, religious courts were granted expanded jurisdiction over economic issues. And in 2008, an anti-pornography law was passed (Matesan, Citation2014).

Malaysia has a narrower range of Islamist parties. Islamist activism in Malaysian politics took off early after World War II and was long spearheaded by the Pan-Malayan Islamic Party (PAS). PAS has been the traditional representative of political Islam in Malaysia and maintains major influence over the current Islamist agenda (Hamid & Razali, Citation2016). In recent times, although in opposition, PAS has become increasingly popular. It has gained more votes in elections and expanded the number of seats held in parliament (Liow, Citation2015).

The ruling party in Malaysia since 1949, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), has also pursued Islamist policies. Liow (Citation2015, p. 11) even argues that: ‘After all, there is […] little that differentiates between PAS and UMNO today insofar as an Islamic agenda is concerned’. Notably, many of its members have supported initiatives to introduce sharia law in Malaysia. UMNO was quick to take advantage of a rising Islamic consciousness in the Malay-Muslim community in the early 1980s, triggered by major external events such as the war in Afghanistan and the Iranian revolution, to strengthen its grip on power. It expanded the religious bureaucracy, introduced Islamic banking institutions, and established an Islamic university. These accommodating policies were very different from the actions of regimes elsewhere in the Muslim world, which moved to discredit the Islamist agenda (Liow, Citation2015).

The Islamization process in Malaysia has not only manifested itself politically but was always anchored in an Islamic social movement known as dakwah, which emerged after the May 1969 race riots, and has played an important role in facilitating Islamization in Malaysia and in transforming the state and society (Liow, Citation2009). Successive Malaysian administrations have since given increasing space to Islamic programs and policies and opened up avenues for Islamist parties to pursue their political-religious ambitions.

Although not wholly in the category of institutional openness to political Islam, both the Philippine and Thai governments have committed to political dialogue with armed insurgents, and to varying success made efforts to achieve negotiated solutions to violent conflict. These efforts may have played a role in reducing levels of violence and making sure conflicts have not escalated to war.

In March 2014, the Philippine government and MILF signed the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB), aiming to bring an end to a destructive and protracted armed conflict. Cementing previous agreements struck in 2012 and 2013, the CAB stipulates the creation of an autonomous Bangsamoro entity in Mindanao. The peace process, which began in the latter half of the 1990s, contributed to substantially reduce levels of violence between the warring parties until the signing of the CAB in 2014 (Pettersson & Wallensteen, Citation2015).

Although not to equal success, the government of Thailand has participated in negotiations with Islamist rebels, notably Barisan Revolusi Nasional Coordinate (BSN-C), in southern Thailand. Negotiations have often been facilitated by Malaysia, and the first high-profile, official talks were held in Kuala Lumpur in 2013, where the parties agreed on a formal peace process dialogue. Prior to the 2013 negotiations, government officials had been in contact with insurgent group representatives since 2005. Informal talks were allegedly ongoing in 2006 but broke down soon after. And what may have been an emerging ceasefire agreement in 2008 never materialized (Wheeler, Citation2014).

Counterterrorism by Southeast Asian regimes

The third explanation lies in effective, albeit repressive, government counter-measures against jihadist terrorist groups, most notably, JI. Since 2000, Southeast Asian regimes have coordinated their efforts and made a series of targeted arrests undercutting the organizational capabilities of JI, the most established jihadist organization in the region. These arrests severely undermined the group's attempts to establish itself comprehensively in Southeast Asia (Sidel, Citation2009, p. 275). As such, government counterterrorism against JI may have played an important role in preventing jihadist civil wars in the region.

Inspired by Qutbist notions of fighting apostasy and overthrowing the state, and aiming, ultimately, to establish an Islamic caliphate, JI became world-renowned on 12 October 2002 when it bombed two night clubs in Bali, killing over 200 people and wounding more than 300. This was followed by one major attack every year between 2003 and 2005: against the Marriot hotel (2003) and Australian Embassy (2004) in Jakarta and another assault on Bali (2005). After Bali II, the next major JI attacks came against the Marriot and Ritz Carlton hotels in Jakarta in 2009, which resulted in 7 dead and 53 wounded (Matesan, Citation2014; Oak, Citation2010).

Indonesia began stepping up its efforts against JI after Bali I. In the years after the attack, Indonesia carried out 466 arrests (at the time almost 25 percent of the group's known membership) and numerous successful raids and weapons confiscations, which contributed to severely cripple JI. The formation of the special police force D88 was crucial: it proved highly effective in identifying and capturing JI leaders and key operatives. For example, JI founder and emir Abu Bakar Ba'asyir was apprehended only a week after Bali I and his replacement, Abu Rasdan, six months later (Oak, Citation2010).

Important arrests then took place in each year between 2002 and 2005 and beyond. In summer 2005, police arrested a group of JI militants involved in the 2004 Australian Embassy attack, and located materials used in Bali I (Abuza, Citation2007). And in 2007, two of JI's most senior leaders were caught (Matesan, Citation2014). When Indonesia began cracking down on JI, the group had already been targeted by Singapore and Malaysia one year earlier – underscoring the regional spread of JI. In December 2001, Singaporean authorities apprehended large numbers of terrorist suspects after learning that top JI operative Hambali had been plotting with Al-Qaeda (Matesan, Citation2014). Singapore was successful in preventing numerous JI attacks and dissolving the jihadist network in the country. Also in 2001, the Malaysian government carried out a host of arrests and interrogations leading to the capture of key JI figures, including Hambali who was suspected of having led planning and operations in Malaysia (Oak, Citation2010). This was a good example of Southeast Asian counterterrorism collaboration, which materialized through the cooperation of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, under US coordination (Byman, Citation2015).

In general, increased intelligence sharing between, primarily, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore has helped unveil the structures and networks of radical Islamist groups in Southeast Asia and thus improved the states’ abilities to track down terrorist suspects across the region. Indonesia and Australia have also used their strong security ties to disrupt communication between extremists in the two countries (Oak, Citation2010).

Through intelligence gathering, control over the media, and collaboration with neighboring states, Malaysia has disrupted the networks and structure of JI and countered attempts by the group to establish itself in the country (Liow, Citation2009). Counterterrorism collaboration between Malaysia, Singapore, and other regional states has been particularly important as it has targeted and dissolved Mantiqi I – the regional command responsible for JI's finances and an important source of leadership. This has dealt the group a severe blow. At an early stage it also restricted opportunities for JI personnel to travel across the region and contributed to isolate hubs in JI's regional network. JI's operational capacity was then further reduced when Australia dismantled Mantiqi IV, a fundraising body of JI (Oak, Citation2010, p. 1000).

Governments in Southeast Asia have responded to the JI threat with restraint, keeping in mind that a key motivation for terrorists can be anger at coercive government policies (Abuza, Citation2007, p. 56). For example, Indonesian counterterrorism has been respectful of human rights and the rule of law, trying terrorist suspects in open legal proceedings (Jones, Citation2012). Intelligence gathered in hearings with arrested JI members and by undercover agents have led to a greater understanding of the group, including its recruitment methods and in-group social networks (Abuza, Citation2007, p. 60).

JI was Southeast Asia's largest and most potent jihadist organization, with regional ambitions beyond Indonesia. It had a physical presence in several countries in the region and enough resources and support to infiltrate and escalate ongoing local conflicts, and use them to spread its jihadist ideology. Yet, by 2007 JI had virtually lost its hold in Mantiqi I and IV – due to the counterterrorism efforts of Malaysia, Singapore, and Australia – and the operational capacity of Mantiqi III was very much in doubt. JI's administrative structure had essentially been reduced to Mantiqi II and the group was shifting away from militancy (International Crisis Group, Citation2007). More recently, JI has been described as ‘a decentralized organization with no clear leader’ (Oak, Citation2010, p. 990). This is not to say that JI has ended. Most agree that the group is still alive and active, albeit in a different way than before. Yet, had JI not been as effectively countered and undermined, it would have been better able to pursue its regional ambitions and empower local militant movements in a greater, transnational jihad. An important factor that may thus help to account for the lack of jihadist civil wars in Southeast Asia is government repression of JI.

Toward an understanding of the ‘Southeast Asian Jihadist Peace’

It is now time to develop the links between the three elements of the explanation for why Southeast Asia has avoided jihadist civil war: (1) lack of internationalization; (2) political channels for Islamist aspirations; and (3) repression. We argue that these three components – weighing differently across the cases – have worked in combination to both prevent the outbreak of jihadist conflicts and hinder significant violent escalation of ongoing jihadist and nationalist-Islamist conflicts.

The lack of internationalization of Southeast Asian Islamist conflicts has kept them from undergoing significant escalation. An external state actor providing troops to parties in conflict has been shown to make conflicts more violent (see Lacina, Citation2006). Our data show that 81 percent of non-internationalized religious conflicts 1975–2015 were of minor intensity. In other words, if conflicts can avoid internationalization, they seem very likely to avoid major escalation. This lends support to the notion that absent internationalization of jihadist and nationalist-Islamist conflicts in Southeast Asia may have prevented them from escalating to civil war.

Moreover, absence of internationalization has likely played an important role in keeping rebel demands moderate. By maintaining domestic control over their counterinsurgency campaigns, governments in the region have made it more difficult for jihadist ‘entrepreneurs’ seeking to frame their struggle as part of a global jihad against foreign intruders waging war on Islam. Rather than giving them opportunities to justify this worldview, non-internationalization has contributed to keeping conflicts at a relatively low level of visibility from a global perspective. The perception that the opponent is the central government, not an international coalition of ‘infidel armies’, may well be an important reason to why rebels have largely refrained from articulating too extreme demands, such as creating a transnational Islamic state, and instead sought autonomy or independence for a certain territory within established national borders.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, the generous space provided to political Islamism has created alternative, legitimate channels for Islamist organizations to raise political ambitions. Calls for Islamic law have been supported by these governments, and to various extents even been implemented. In this context, jihad has been a relative failure as most Islamist political organizations have abstained from revolutionary approaches and violent means. We hold that, in these two countries, this variable has primarily played a role in preventing the outbreak of violent conflict. The logic of this argument is that if groups can participate in, and exert influence through, the political process, they should have weaker incentives to fight since violence is a costlier means of struggle than political participation (Elman, Citation2008; Hafez, Citation2003).

A concrete Indonesian example of accommodating political Islamism is represented by the 2001 special autonomy status granted to Aceh, which allowed application of Islamic law in the province. Since the religious issue in the conflict between GAM and the Indonesian government was the former's demand for an Islamic state governed by sharia law, the special autonomy act likely played an important role in taking religion out of the conflict (Svensson & Harding, Citation2011). It should be noted that the special autonomy act did not put an end to the conflict. It continued to escalate after 2001, but over other issues than religion.

In the Philippines and Thailand, governments have shown a willingness to engage in dialogue and peace negotiations with militant Islamists. In the Philippines, the peace process between the government and MILF contributed to reduce the intensity of their conflict, and eventually led to the signing of a peace agreement. Importantly, within the framework of peace negotiations, MILF moderated its demands. Upon returning to the negotiation table in 2011 MILF's objective was autonomy, not separation (Podder, Citation2012).

Interestingly, the Philippine government has shown openness to the new Bangsamoro Autonomous Region (BAR) taking on Muslim legislation, in that its Muslim population can abide by the sharia. This could be interpreted as the kind of institutional openness to Islamist political aspirations, albeit less comprehensive, as that offered in Indonesia and Malaysia.

Political dialogue in Thailand has not been as successful as in the Philippines. Yet, that does not mean it has been useless. By creating space for political procedures, crucial information about the other's interests and intentions can be revealed, leading parties to re-evaluate their stance. Even though negotiations between Bangkok and Malay Muslim insurgents have yet to make significant progress, attempts to establish talks signals willingness to compromise, which may be behind the insurgents’ relatively moderate demands – in terms of being nationalist-Islamist rather than trans-jihadist. In the early stages of the formal talks in Malaysia in 2013, the leading BRN representative, Hassan Taib, demanded the government to recognize his group as a liberation rather than separatist movement (Wheeler, Citation2014). Also, levels of violence in the conflict have consistently been lower after 2006, when the first attempts at informal talks were made. And barring an increase in violence between 2010 and 2013, after the formal negotiations held that same year, violence levels dropped to their lowest point since 2003.

Peace dialogue has also taken place in Indonesia, between the government and GAM. In 2005, they struck a peace agreement, facilitated by Finnish diplomat Martti Ahtisaari, which put an end to their conflict. Peace negotiations in Indonesia may have been an important complement to the state's constitutional openness to Islamist political aspirations.

The third explanatory factor to the absence of jihadist civil war in Southeast Asia is governments’ counterterrorism, which severely undermined the operational capacity of JI, the largest jihadist organization in the region. Between 2000 and 2005, JI was at its operational height: its membership numbered in the thousands; ties with Al-Qaeda were at their strongest; and the frequency and severity of its attacks highest. JI developed into an international terrorist group, setting up specialized regional divisions across Southeast Asia and beyond (Oak, Citation2010). The group had the resources and connections to escalate and tap into local conflicts to pursue and spread its trans-jihadist agenda.

Yet, the individual and concerted efforts of regional governments in the 2000s struck a severe blow to JI and hindered its attempts to really establish itself in Southeast Asia. Over time, JI's administrative structure was reduced to the Indonesian mantiqi, and the group was forced to abandon militancy.

While JI may have stuck to terrorism as its primary means of violent struggle, the group still had the resources and connections to sustain and step up its own terrorist campaign and to empower and collaborate with groups across the region. Had it not been targeted by such effective counterterrorism measures, it would have had greater opportunities to radicalize local Islamist militant groups across Southeast Asia and link their struggles to the international jihadist scene. Such a development would have increased the risk of minor conflicts to escalate and become internationalized, and reduced the prospects for peace negotiations in Thailand and the Philippines.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have shown that between 1975 and 2015, Southeast Asia did not experience a single year of jihadist civil war. This is remarkable considering several factors that make the region at risk for jihadist violence. We have proposed a comprehensive, hypothetical explanation for this ‘missing jihad’, composed of three inter-related factors: the lack of internationalization of religious armed conflicts; the opening of political channels for voicing Islamist-styled aspirations; and effective and collaborative counterterrorism against the region's largest jihadist terrorist group. Together, we suggest, they have worked to prevent jihadist civil wars from breaking out and contained ongoing minor conflicts from escalating in terms of both intensity and ideology. We argue that the Southeast Asian experience provides important insights for conflict prevention and resolution efforts also outside the region.

The absence of internationalization of Islamist conflicts in Southeast Asia may hold important lessons for managing similar crises elsewhere. Judging by the Southeast Asian experience, when external states do not insert troops into conflict to support the warring parties, the risk of conflicts undergoing major escalation decreases significantly. Without this inflow of extra resources, parties may be incapable of prolonging or intensifying conflict. And without the presence of, for example, Western forces in Muslim lands, jihadist ‘entrepreneurs’ will have a much harder time framing local struggles as part of a global jihadi war. This may prevent rebel demands from escalating and keep local conflicts local. Southeast Asia has been spared from the forms of transnational violent jihadism witnessed in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia, where powerful external states have often intervened with troops in Islamist conflicts. Non-internationalization of Islamist conflicts in Southeast Asia may thus entail lessons for combatting the rise and spread of violent jihadism.

The available political channels (and certain legislative concessions) to Islamist political actors in Indonesia and Malaysia illustrate how the existence of non-violent alternatives for exerting political influence weakens support for actors who promote the use of violence to change the status quo. Allowing Islamist parties to participate in the political process – rather than banning and persecuting them – can thus be part of a strategy to limit the lure of violent jihadist groups, as potential supporters are more likely to back non-violent groups if they feel that these have the opportunity to influence politics. This is not to say that giving room to political Islamism is unproblematic. It may have negative human rights consequences, including for women's, LGBT, and religious minorities’ rights. However, by gaining access to politics and the processes of negotiation and compromise it comprises, Islamist parties may be forced to moderate and modernize their policies – perhaps also in order to remain relevant and appealing.

Peace processes in the Philippines and Thailand are other examples of opening political channels to raise Islamist ambitions. The Philippine experience best illustrates how peace negotiations can contribute to reduce levels of violence in conflict, reveal crucial information about the other's interests, and lead parties to moderate their demands. In the ideal scenarios, talks produce peace agreements and governments win new partners in dealing with the most radical groups. Should the 2014 peace deal between MILF and the Philippine government be thoroughly implemented, this peace process could serve as an inspiration for handling similar conflicts around the world.

Intergovernmental counterterrorism collaboration against the largest and most powerful jihadist terrorist networks happens everywhere. We do not argue that this variable alone explains the absence of jihadist civil war in Southeast Asia, but rather that it has contributed to the outcome in combination with the other two main components of our model. Yet, we should remember that counterterrorism can be practiced in different ways and to different effect, and this is where Southeast Asian nations’ concerted efforts to dismantle the JI network may hold important lessons. While not without its faults and oversteps, regional counterterrorism cooperation against JI was highly effective and, importantly, largely conducted with respect for the rule of law. Terrorist suspects were arrested and tried in open legal procedures: counterterrorism was treated as a matter for the criminal justice system – not the military. This is important because it signals the state's dedication to upholding the democratic values that come under attack by violent extremists. Failure to comply with the rule of law in dealing with suspected terrorists may instead put into question the legitimacy of the state and increase support for the extremists and their cause. Southeast Asian counterterrorism collaboration against JI thus included key tactics that other states may look to and employ in battling contemporary terrorist threats.

Southeast Asia has not witnessed a single jihadist civil war since 1975. This is impressive for several reasons. The region's experiences over the past forty years contain important lessons for how to handle religiously charged armed conflicts. Accordingly, a combination of de-internationalization of religious conflicts, opening non-violent channels for political-religious actors, and effective counterterrorism collaboration with respect for the rule of law, could be important components in a larger contemporary strategy to prevent and resolve jihadist wars.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was generously supported by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, The Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences, through grants NHS14-1701:1 and M10-0100:1. Work on this article began within the framework of the research program ‘The East Asian Peace Since 1979: How Deep? How Can It Be Explained?’, led by Professor Stein Tönnesson at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University. The authors would like to thank Professor Tönnesson and the other members of the research program's Core Group (Holly Guthrey, Elin Bjarnegård, Kristine Eck, Erik Melander, and Joakim Kreutz) for their comments on an early draft of the article. The authors would also like to thank the editorial team of The Pacific Review for its support as well as the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniel Finnbogason

Daniel Finnbogason received his MA degree in social sciences, specializing in peace and conflict studies, at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research (DPCR), Uppsala University, in Summer 2015. His research interests include religion and violence, terrorism studies, conflict resolution. He currently works as a research assistant in ‘Resolving Jihadist Conflicts? Religion, Civil War, and Prospects for Peace’, led by Professor Isak Svensson at the DPCR.

Isak Svensson

Isak Svensson is a professor at the DPCR, Uppsala University, Sweden. His research focuses on international mediation, nonviolent conflict, religion and conflict. He has published in journals such as the Journal of Conflict Resolution, Journal of Peace Research, International Negotiation, and European Journal of International Relations. He is author of International Mediation Bias and Peacemaking: Taking Sides in Civil Wars (2015), Ending Holy Wars: Religion and Conflict Resolution in Civil Wars (2012), The Go-Between: Jan Eliasson and the Styles of Mediation (2010) with Peter Wallensteen, and co-editor of International Relations and Religion, Vol. I–IV (2016) with Ron E. Hassner. He is the project leader of the international research project ‘Resolving Jihadist Conflicts? Religion, Civil War, and Prospects for Peace’.

Notes

1. We employ the UCDP's definition of internationalized conflict, that is ‘conflicts where at least one of the parties is supported with troops from an external state’ (Melander et al., Citation2016, p. 729–30).

2. One of the authors of this study makes a similar argument in his contribution to a forthcoming book on the so-called ‘East Asian Peace’, yet in a different form and with a broader geographical focus (see Elin Bjarnegård and Joakim Kreutz (eds), Debating the East Asian Peace: What it is. How it Came About. Will it last? NIAS Press. Forthcoming, 2017).

3. The RELAC data-set codes religious dimensions in all state-based armed conflicts in the world since 1975. It has been developed within the research project ‘Resolving Jihadist Conflicts? Religion, Civil War, and Prospects for Peace’ at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, Sweden. The RELAC data are set to be released in 2017.

4. In the RELAC data-set, for Islamist militant groups, the term ‘Revolutionary Islamist’ is used for those that seek government control, ‘Separatist Islamist’ for those that want secession for a certain territory, and ‘Transnational Islamist’ for those that aim to establish a transnational state entity. The latter category is most distinct from the other two because it contains most jihadist groups, such as IS and Al-Qaeda, whereas nationalist-Islamist groups are found in the former two categories.

5. Variations over time in the centrality of parties’ religious demands are not measured. Instead it is the onset of conflict that is utilized for determining whether a conflict should be seen as jihadist or not. Moreover, because we define conflicts based on their incompatibility, conflicts are labeled ‘jihadist’ although only one conflict party makes such claims. This is in line with the language used in previous literature.

6. While Indonesia is a Muslim majority country, Aceh as a region has still partly distinguished itself in terms of religious piousness, and the uprising had, at the onset of the conflict, partly religious aspirations and made use of religious rhetoric (Aspinall, Citation2007). For a debate on how to conceptualize the religious dimensions of the Aceh-region, see Svensson (Citation2016) and Barter and Zatkin-Osburn (Citation2016).

7. The ‘Non-Jihadist’ curve also includes conflicts that do not qualify as jihadist, but that involve at least one actor with partly Islamist political aspirations. That is, conflicts where the religious issue has low salience, e.g. the Philippines-MILF conflict. Jihadist conflicts are instead coded as ‘high salience’ in the RELAC data-set, because religion is central to the incompatibility.

8. Revolutionary ideologies can shift over time. For example, in Aceh, an originally Islamist uprising took a more nationalist character (Aspinall, Citation2007). And in southern Thailand the conflict has gone from ‘ethnic’/nationalist to being more religiously framed (Harish, Citation2006).

9. Ours is not the first study to suggest a link between non-interference and non-escalation of armed conflicts in Southeast Asia. Kivimäki (Citation2015) looks at the greater East Asian region and shows that non-interference has been a key to the near-disappearance of battle-related deaths in East Asia since 1979. Unlike us, however, he uses a wider geographical scope and does not focus on a certain type of conflict, but rather conflicts more generally.

10. Sidel (Citation2007) notes that the Indonesian Islamist militancy was driven to a large extent by the disappointment of the lack of impact and influence for Islamists in parliamentary politics.

References

- Abuza, Z. (2003). Militant Islam in Southeast Asia: Crucible of Terror. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Abuza, Z. (2007). Political Islam and Violence in Indonesia. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Abuza, Z. (2016). Forging Peace in Southeast Asia: Insurgencies, Peace Processes, and Reconciliation. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Abuza, Z. (2016a). Beyond bombings: the Islamic state in Southeast Asia. Retrieved from http://www.thediplomat.com//2016/01/beyond-the-bombings-assessing-the-islamic-state-threat-in-southeast-asia/

- Aspinall, E. (2007). From Islamism to nationalism in Aceh, Indonesia. Nations and Nationalism, 13(2), 245–263.

- Barter, S. J., & Zatkin-Osburn, I. (2016). Measuring religion in war: a response. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 55(1), 190–193.

- Byman, D. (2015). Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and the Global Jihadist Movement: What Everyone Needs to Know. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Cochraneov, J. (2015). From Indonesia, a Muslim challenge to the ideology of the Islamic state. New York Times, 26 November. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/27/world/asia/indonesia-islam-nahdlatul-ulama.html?_r=0

- Cook, D. (2005). Understanding Jihad. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Cronin, A. K. (2009). How Terrorism Ends: Understanding the Decline and Demise of Terrorist Campaigns. New Jersey, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Crouch, M. A. (2012). Law and religion in Indonesia: the constitutional court and the Blasphemy Law. Asian Journal of Comparative Law, 7(1), 1–46.

- Elman, M. (2008). Does democracy tame the radicals? Lessons from Israel's Jewish religious political parties. Asian Security, 4(1),79–99.

- Fellman, Z. (2011). Abu Sayyaf Group. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

- Freedman, A. L. (2009). Civil society, moderate Islam, and politics in Indonesia and Malaysia. Journal of Civil Society, 5(2),107–127.

- Gershman, J. (2002). Is Southeast Asia the second front ?Foreign Affairs, 81(4),60–74.

- Gunaratna, R. (2005). Ideology in Terrorism and Counter Terrorism: Lessons from combating Al-Qaeda and Al Jemaah Al Islamiyah in Southeast Asia. Shrivenham, Oxfordshire: Conflict studies research centre.

- Gunaratna, R. (2016). The Islamic state's eastward expansion. The Washington Quarterly, 39(1),49–67.

- Hafez, M. M. (2003). Why Muslims Rebel: Repression and Resistance in the Islamic World. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Hamayotsu, K. (2013). Towards a more democratic regime and society? The politics of faith and ethnicity in a transitional multi-ethnic Malaysia. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 32(2),61–88.

- Hamid, A. F. A., & Razali, C. H. C. M. (2016). Middle Eastern influences on Islamist organizations in Malaysia: the cases of ISMA, IRF and HTM. Singapore: ISEAS – Yushof Ishak Institute.

- Harish, S. (2006). Ethnic or religious cleavage? Investigating the nature of the conflict in Southern Thailand. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 28(1),48–69.

- Hassner, R. E. (2009). War on Sacred Grounds. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Hefner, R. W. (2000). Civil Islam: Muslims and Democratization in Indonesia. New Jersey, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hegghammer, T. (2011). The rise of Muslim foreign fighters: Islam and the globalization of jihad. International Security, 35(3), 53–94.

- International Crisis Group. (2007). Indonesia: Jemaah Islamiyah's current status. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/indonesia/indonesia-jemaah-islamiyah-s-current-status

- International Crisis Group. (2015). Southern Thailand: dialogue in doubt. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/thailand/southern-thailand-dialogue-doubt

- Jones, S. (2012). Changing terrain of terrorism in South-East Asia https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/changing-terrain-terrorism-south-east-asia. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/changing-terrain-terrorism-south-east-asia

- Juergensmeyer, M. (1993). The New Cold War? Religious Nationalism Confronts the Secular State. Berkeley, Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

- Juergensmeyer, M. (2008). Global Rebellion: Religious Challenges to the Secular State from Christian Militias to Al-Qaeda. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Kivimäki, T. (2015). How does the norm on non-interference affect peace in East Asia? Asian Survey, 55(6), 1146–1169.

- Lacina, B. (2006). Explaining the severity of civil wars. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 50(2), 276–289.

- Liow, J. C. (2006a). International jihad and Muslim radicalism in Thailand? Toward an alternative interpretation. Asia Policy 2(July), 89–108.

- Liow, J. C. (2006b). Muslim Resistance in Southern Thailand and Southern Philippines: Religion, Ideology, and Politics. Washington, DC: East-West Center.

- Liow, J. C. (2009). Piety and Politics: Islamism in Contemporary Malaysia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Liow, J. C. (2015). The Arab Spring and Islamist activism in Southeast Asia: Much ado about nothing? Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Matesan, I. E. (2014). The dynamics of violent escalation and de-escalation: explaining change in Islamist strategies in Egypt and Indonesia (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, NY.

- Melander, E., Pettersson, T., & Themnér, L. (2016). Organized violence, 1989–2015. Journal of Peace Research, 53(5), 727–742.

- Moghadam, A. (2009). Motives for martyrdom: Al-Qaida, Salafi Jihad, and the spread of suicide attacks. International Security, 33(3), 46–78.

- Nordås, R. (2010). Beliefs and bloodshed: understanding religion and intrastate conflict ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim.

- Oak, G. S. (2010). Jemaah Islamiyah's fifth phase: the many faces of a terrorist group. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 33(11), 989–1018.

- Pettersson, T., & Wallensteen, P. (2015). Armed conflicts, 1946–2014. Journal of Peace Research, 52(4), 536–550.

- Piazza, J. A. (2009). Is Islamist terrorism more dangerous?: An empirical study of group ideology, organization, and goal structure. Terrorism and Political Violence, 21(1), 62–88.

- Pinker, S. (2011). The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined. New York, NY: Viking Press.

- Podder, S. (2012). Legitimacy, loyalty, and civilian support for the moro Islamic liberation front: changing dynamics in Mindanao, Philippines. Politics, Religion & Ideology, 13(4), 495–512.

- Read, M. (2012). Abu Sayyaf crime, ideology, autonomy movement? The complex evolution of a militant Islamist group in the Philippines. Small Wars Journal, 8(10). Retrieved from http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/abu-sayyaf-crime-ideology-autonomy-movement-the-complex-evolution-of-a-militant-islamist-gr

- Schulze, K. E. (2004). The Free Aceh Movement (GAM): Anatomy of a Separatist Organization. Washington, DC: East-West Center.

- Sidel, J. T. (2007). The Islamist threat in Southeast Asia: a reassessment. Washington, DC: East-West Center.

- Sidel, J. T. (2009). Jihad and the specter of transnational Islam in contemporary Southeast Asia: a comparative historical perspective. In E. Tagliacozzo (Ed.), Southeast Asia and the Middle East: Islam, Movement and the Longue Durée (pp. 75–318). Singapore: NUS Press.

- Singh, B. (2007). The Talibanization of Southeast Asia: Losing the War on Terror to Islamist Extremists. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Security International.

- Svensson, I. (2012). Ending Holy Wars: Religion and Conflict Resolution in Civil Wars. Brisbane: Unversity of Queensland Press.

- Svensson, I. (2016). Conceptualizing the religious dimensions of armed conflicts: a response to “Shrouded: Islam, war, and holy war in Southeast Asia”. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 55(1), 185–189.

- Svensson, I., & Harding, E. (2011). How holy wars end: exploring the termination patterns of conflicts with religious dimensions in Asia. Terrorism and Political Violence, 23(2), 133–149.

- Svensson, I. & Nilsson, D. (in press). Disputes over the divine: introducing the religion and armed conflict (RELAC) data, 1975–2015. Journal of Conflict Resolution.

- Toft, M. D. (2006). Issue indivisibility and time horizons as rationalist explanations for war. Security Studies, 15(1), 34–69.

- Toft, M. D., Philpott, D., & Shah, T. S. (2011). God's Century: Resurgent Religion and Global Politics. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

- Toft, M. D., & Zhukov, Y. M. (2015). Islamists and nationalists: rebel motivation and counterinsurgency in Russia's North Caucasus. American Political Science Review, 109(2), 222–238.

- UCDP (Uppsala Conflict Data Program). (2016). Definitions. Retrieved from http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/definitions/.

- Wheeler, M. (2014). Thailand's Southern insurgency. Southeast Asian Affairs, 2014, 319–335.