Abstract

In 2009 ASEAN established a human rights body—the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR)—and tasked it with promoting and protecting human rights in Southeast Asia within ASEAN’s framework of cooperation and to encourage member states to ratify international human rights treaties and act in accordance with them. AICHR has ten Representatives, one for each ASEAN member, and these individuals are tasked with fulfilling AICHR’s mandate. In this article, we utilise the mechanisms and scope conditions contained in the revised Spiral Model to assess the opportunities and challenges that exist in aiding and frustrating their attempts to fulfil AICHR’s mandate to promote and protect human rights. Although routinely dismissed as irrelevant in the fight for human rights in Southeast Asia, we identify that there are reasons for cautious optimism that some Representatives are making headway in making AICHR fit-for-purpose.

Introduction

In this article we seek to address the main criticism levelled at the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) human rights body—the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR), established on the 23 October 2009—that its modus operandi, detailed in its Terms of Reference (ToR) (AICHR, Citation2009) and other guidelines, hamstrings the body from effectively promoting, let alone protecting, human rights. While we acknowledge that its modus operandi can have this effect, and AICHR’s first ten years of existence provide evidence of its limitations, we argue that there is nothing sacrosanct in how AICHR Representatives have interpreted its ToR. Instead, we contend, that by contesting how AICHR operates, its Representatives can both promote and progress the body towards protecting human rights. This contestation is possible not only because the ToR is itself subject to review and explicitly endorses an evolutionary approach to the development of human rights, but, we argue, human rights are themselves perpetually open to interpretation and reinterpretation making contestation of their meaning, and thus a human rights’ bodies interpretation of promotion/protection, an on-going process.

The article therefore addresses the challenges of adjusting AICHR to make promoting human rights more systematic, and, amenable to protecting human rights. We utilise two variables, mechanisms and scope conditions, from the revised Spiral Model to show how this can be accomplished (Risse, Ropp, & Sikkink, Citation2013). We adopt this approach because the Spiral Model is concerned with explaining state commitment to, and compliance with, human rights. The revised version of the Spiral Model was specifically concerned with why compliance did not necessarily follow commitment. This is not unlike the criticism directed at AICHR, that while its creation indicates an ASEAN commitment to human rights, its shortcomings undercut a concomitant desire amongst ASEAN member states (AMS) to comply with human rights. Abubakar Eby Hara utilises Jack Donnelly’s taxonomy of human rights’ regimes in making this point, arguing that AICHR is a promotional regime but has not progressed to an implementation regime (Hara, Citation2019). We argue that because there exist independently minded representatives in AICHR, ASEAN’s human rights body has the potential to evolve, and we contend that the variables identified in the revised Spiral Model provide a meaningful framework for addressing the challenges they face in adjusting the AICHR.

The article forms part of a literature that has applied the Spiral Model to terrorism (Shor, Citation2008), Saudi Arabia (Alhargan, Citation2012), Mongolia and North Korea (Heo, Citation2014), the Maldives (Shahid & Yerbury, Citation2014), Mexico (Muñoz, Citation2009), China (Fleay, Citation2006; Schroeder, Citation2008), and Taiwan (Cheng & Momesso, Citation2017). Specifically, the article contributes to a literature that examines AICHR (Duxbury & Tan, Citation2019; Katsumata, Citation2009; Tan, Citation2011; Wahyuningrum, Citation2021a), and further develops the application of the Spiral Model to ASEAN (Davies, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Renshaw, Citation2016), including by the co-author to AICHR that this article develops further (Collins, Citation2019a). In the previous article the regression of human rights in Southeast Asia was juxtaposed with efforts to promote human rights in AICHR, and the article interpreted the puzzle of how to turn AMS’ commitment to human rights into their compliance with human rights by examining how AICHR Representatives’ programmes and other initiatives help with this goal. In this article, we focus exclusively on AICHR and use turning a commitment into compliance to reveal structural constraints, and the extent to which they are contestable, that undercut its efficacy.

We begin with an explanation of the revised Spiral Model, revealing that argumentative discourse is essential to understanding how AICHR Representatives can problematise existing understandings of AICHR. We argue that the mechanism of persuasion is the primary one available to AICHR Representatives and we reveal how their success is dependent on the scope conditions that currently prevail. However, we do not regard the scope conditions as fixed but contestable. In the substantive part of the article, we reveal how AICHR’s scope conditions create structural obstacles that hamstring ASEAN’s human rights body, but also how some AICHR Representatives are contesting these conditions. To reveal these contestations, we draw upon the experiences of current and ex-AICHR Representatives, most notably those of the co-author. Where the material is in the public domain or an AICHR Representative has given permission for their insights to be attributed to them, they are named, otherwise we retain their anonymity to safeguard the confidentiality of information provided to us.

Spiral model

The Spiral Model first appeared in The Power of Human Rights (Risse, Ropp, & Sikkink, Citation1999) and it has been subsequently revised in the follow-up publication, The Persistent Power of Human Rights (Risse et al., Citation2013). The Spiral Model posits a five-phase progression of state engagement with human rights, from repressing human rights at one end of the spectrum through to compliance with international standards of human rights at the other end of the spectrum. Each phase is marked by a socialisation process that explains why the state is at the current stage, and its likely progression to the next. Although the authors reject the criticism that the Model posits a linear progression in which state actors become persuaded by the strength of the human rights’ argument, and consequently commit to, and then comply with, international standards, the application of the model often describes movement through these phases in sequence.Footnote1 We return to the issue of sequencing below because our argument is not that understandings of human rights follow a progressive sequence of acceptance but rather that they remain permanently contested, and that this understanding of what constitutes human rights is helpful in explaining how a human rights body evolves.

In The Persistent Power of Human Rights, the authors were interested in why states that had shown a commitment to human rights did not necessarily follow through to acting in compliance with international standards of human rights. To explain the difficulty in turning a commitment into a compliance they introduced two variables: mechanisms and scope conditions. Mechanisms are the tools available to activists to pressure and assist states in complying with human rights, scope conditions refer to the context in which these mechanisms are deployed. Scope conditions therefore refer to the conditions that establish what mechanisms are likely to be more or less successful. While the Spiral Model is primarily concerned with states as the actors to pressure, and thus the scope conditions pertain to the state, here we interpret scope conditions to be the context in which AICHR Representatives are promoting/protecting human rights. Our scope conditions are therefore those that pertain to AICHR, and we are interested in identifying which mechanisms, and what scope conditions, are pertinent for changing AICHR so that it is a more productive space for promoting/protecting human rights. We therefore concur with Risse et al that non-state actors are also possible targets (2013, p. 5), but whereas they argue that the first two scope conditions are only applicable to states (2013, p. 16) we regard all five scope conditions applicable to AICHR.Footnote2

In the Spiral Model the actor that has shown a commitment to human rights but yet to comply, and the activists seeking to change this, are distinct. However, we are using AICHR Representatives as the agents utilising the mechanisms to change the AICHR. Our agents for change are thus not separate from the target, but constitutive members of it, and we are specifically interested in the activities of those we classify as independently minded. Given that AICHR Representatives are AMS appointees and answerable to their governments, this designation requires an explanation. While it is true the AMS do appoint their own AICHR Representative (ToR Article 5.2) and can remove them before their term of office is complete (ToR Article 5.6), AMS adopt different means of selecting their Representatives. Some are selected by their governments and are either serving or ex-government officials; they see their role as representing their governments. Other AMS though, notably Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, have an accessible selection process and where applications are open to the public. This has led to non-government officials becoming AICHR Representatives, who interpret their role as representing their state rather than the incumbent government and championing the human rights of the region. This distinction is based on their interpretation of AICHR’s ToR Article 5.7, that Representatives ‘shall act impartially in accordance with the ASEAN Charter and this TOR’, and we identify these Representatives as independently minded. As will become evident, contestation arises between those that are independently minded and those that perceive their role as representing their government.

Mechanisms and scope conditions

There are four mechanisms and five scope conditions in The Persistent Power of Human Rights and having previously identified which of these variables are pertinent to AICHR we provide only a summary here (Collins, Citation2019a). Of the five scope conditions the most important is regime type, and what matters for determining if the target state is susceptible to turning a commitment into compliance is if the target state’s regime is in transition. Thus, a state transitioning into a democracy is more likely to be supportive of complying with international human rights standards as a marker of its new identity. A regime that is not in transition, and has domestic support thus making it robust, is one that is capable of resisting measures to make it comply with international standards of human rights. This is true regardless of regime type. Thus, robust democracies are just as capable of resisting human rights narratives as authoritarian states. The literature makes reference to a number of strategies that can be deployed to counter human rights narratives, such as immunising the state from harmful rights that can threaten societal cohesion (see Nuñez-Mietz & Garcia Iommi, Citation2017), to defiance in which the meanings of the rights are adjusted so that they are fundamentally altered (see Terman, Citation2019). This notion that rights can be contested is significant because it reveals that if the regime type is robust then contesting the regime’s legitimacy is a precursor for creating propitious conditions for advancing human rights.

Of course, AICHR is not a state, however we contend that AICHR’s modus operandi can be equated to a regime type. That is, its regime type is its governance framework, which includes both its institutional structures and prevailing modus operandi, the latter commonly referred to as the ASEAN Way, and that much of the criticism directed at AICHR is criticising its regime type. Namely, its ToR undercuts its ability to protect human rights and cannot, in the face of AMS opposition, promote human rights. For example, the ToR does not provide mechanisms essential to protecting human rights, such as the ability to receive complaints, investigate abuses, or provide a remedy. Its promotional activities are limited both by financial constraints and the lack of authority to embed human rights in ASEAN activities. As an ASEAN body, AICHR also operates in accordance with the ASEAN Way, which means it does not interfere in the internal affairs of AMS and it reaches decisions through consultation and consensus. It is these limitations that explain why AICHR is routinely regarded as weak and not fit-for-purpose (see Cumaraswamy, Citation2021, p. 27; Hanara, Citation2019; International Federation for Human Rights, Citation2009; Limsiritong, Citation2018; Paulsen, Citation2019). We thus contend that contesting AICHR’s regime type is a vital precursor to advancing human rights.

We can include in this contestation two other scope conditions that refer to the control that states have over their territory; limited statehood and devolved political power. Essentially, for both scope conditions the more decentralised the governance structure, the harder it is for a central government to achieve compliance. Here we can interpret this control as AICHR’s relationship with other actors, so this refers to the institutional structures that permit participation with other bodies within ASEAN.

The final two scope conditions are concerned with how susceptible the state is to material incentives to comply with human rights, such as tying aid packages to an improving human rights record, and social incentives in which a state’s sense of identity is tarnished by failing to comply. In this instance, we conceive of material vulnerability equating to AICHR’s funding, and social vulnerability to AICHR’s reputation, since it embodies ASEAN’s commitment to human rights. In the section below we will draw upon AICHR Representatives’ experiences in showing how these scope conditions curtail human rights discussions, but also how they can be contested. This is different from The Persistent Power of Human Rights where the scope conditions are treated as fixed and reveal the challenges and opportunities that activists will face or exploit to engender change. In this article, we show that the scope conditions are themselves malleable via contestation. To know how they are contested requires identifying the mechanisms available to AICHR Representatives (see Collins, Citation2019a, pp. 382–385).

Of the four mechanisms, we focus on the third mechanism: persuasion and discourse. We identify this as the one available to AICHR Representatives because of ASEAN’s prerequisite for consultation and consensus in its decision-making process. This means that engaging in argumentative discourse to persuade is the most valuable tool for contesting AICHR’s modus operandi and establishing the means to progress the remit of AICHR to effectively promote and protect human rights. This is not to deny the operation of the other three mechanisms in ASEAN, but for the purpose of this article, they are not explored further here. For example, the first two mechanisms (coercion and changing incentives via sanctions and rewards) are available to some Representatives depending on how senior they are, but vis-à-vis their internal line agencies and their own country’s counterparts. Likewise, the fourth mechanism, capacity building, is the common programmatic response to requests by governments who say that they cannot comply for lack of expertise and funding.

Argumentative discourse

The critique of the Spiral Model that it sequences the progression of human rights goes further than positing progression along a spectrum as the human right in question becomes adopted. The Model is premised on contestation between those promoting and those opposing human rights. The Model proposes a process of socialisation as the contestation moves through three different interaction modes. Where the state is deflecting criticism, the contestation is called instrumental rationality, and it amounts to the state making tactical concessions (release of political prisoners for example) without being persuaded of the validity of the human right. The next mode is argumentative discourse, and this is where the human right is recognised by state and activists but what the right means in specific contexts is open to negotiation. This mode of interaction is characterised by discourses to persuade, with the goal to change an actor’s understandings and develop collective understandings. Argumentative discourse between norm entrepreneurs and antipreneurs (Bloomfield, Citation2016) is expected to be fierce, but there is the expectation that once a compliance with human rights is achieved, the compliance is underpinned, and made robust, because the state has come to believe in the human right.Footnote3 The human right in question has become safeguarded by the final mode of interaction, which as a habitual acceptance of it by the state and it is institutionalised in state practice. It has become normalised. This is the final stage of the model and is called rule-consistent behaviour.

We contend though that within rule-consistent behaviour beliefs opposed to the human right remain, and that when times are propitious to challenge the prevailing view, they can be re-energised. We therefore expect argumentative discourse to be required to resist back-tracking. It explains why it was previously contended that it is not the persistent power of human rights, but the persistent battle for human rights (see Collins, Citation2019a). This notion that beliefs remain perpetually contestable underpins our argument that contestation over how AICHR operates is an on-going process, and not restricted to an event reviewing the ToR. In essence, given the contestable nature of human rights, what constitutes promotion and protection is also contestable. There will be actors that have a privileged position for interpreting what is feasible and permissible, but depending on the scope conditions and mechanisms available, all actors can interpret and reinterpret—contest—what is possible.

Our preference for the mechanism persuasion through argumentative discourse for examining AICHR is two-fold. First, the ToR and the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD), the latter adopted November 2012, represent agreed upon norms that underpin how an ASEAN human rights body promotes and protects, and what constitutes human rights in Southeast Asia. Below we will show that, while some AMS might have seen the creation of AICHR, its ToR, and the AHRD as a tactical concession, by engaging with the provisions in the ToR and AHRD some AICHR Representatives have ensured that a process of argumentative discourse is underway. In essence, while we have agreed upon norms (ToR) and rights (AHRD), what these mean remains open to interpretation. Second, ASEAN’s mode of interaction is consultation and consensus decision-making, which promotes argumentative discourse as AICHR Representatives engage in discussion to reach a consensus.

A key component in charting the process of argumentative discourse in ASEAN is appreciating the value of precedent setting. Once certain terms, phrases, norms have been accepted they are routinely repeated in ASEAN documentation and can be used to interpret feasible follow-on actions. It is important to recognise that while there is this continuity, what is meant in this repeated terminology remains open to interpretation. Therefore, modifications are possible to adjust the meaning of the human right. A good example of this was the promotion of rights for persons with disability pursued by Seree Nonthasoot, the Thai AICHR Representative (2013–2018).

Utilising AMS commitments to the rights of disabled people, as evidenced by all AMS ratifying the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities by 2016, coupled to ASEAN commitments, such as the Bali Declaration on the Enhancement of the Role and Participation of the Persons with Disabilities in ASEAN Community and the Mobilization Framework of the ASEAN Decade of Persons with Disabilities 2011–2020 (ASEAN, Citation2013), Nonthasoot was able to achieve the adoption of the ASEAN Enabling Masterplan 2025: Mainstreaming the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in November 2018 (ASEAN, Citation2019). The Masterplan thus represents an AICHR initiative, which, in conjunction with other ASEAN bodies, provides assistance for AMS turning their commitment to the rights of the disabled into a compliance. In addition to placing this initiative within already existing specific commitments to the rights of the disabled, Nonthasoot was also able to present these rights as part of a broader ASEAN commitment to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals and gaining support from other AICHR Representatives by placing these rights into activities, such as health, education, and employment, that were of specific interest to them. As such, the Task Force on Mainstreaming the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in the ASEAN Community when drafting the Masterplan had to include sectoral bodies and experts across different fields. It also became a catalyst for other cross-cutting programmes such as a workshop on disabled children’s access to primary education.

Nonthasoot was thus able to persuade other AICHR Representatives, and other ASEAN officials, by framing the discussion within already existing commitments, and coupling these rights to their specific concerns. The rights of the disabled initiative is also important in establishing more broadly that human rights’ abuses stem from discrimination. Nonthasoot used this precedent to promote the virtues of legal aid, by linking discrimination and inequity of treatment to ASEAN’s commitment to creating caring societies. He framed it as a prerequisite for creating an inclusive, people-centred and people-oriented community (See Collins, Citation2019a, pp. 383–385).

While the experience of mainstreaming the rights of the disabled is helpful in revealing how precedent setting can assist argumentative discourse, it also reveals that success was dependent on the conviction, dedication, and resolve of an individual AICHR Representative, and thus not necessarily indicative of an on-going, and broader, human rights contestation in AICHR. What would be helpful, is an institutional endorsement of discussion and dialogue with the stated aim of member states exchanging their views on, for example, how human rights are promoted in their jurisdictions and their progress in implementing international human rights’ law, how to implement recommendations from the United Nations Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review, and/or their interpretation of the AHRD. Institutionalising this in AICHR practice creates the expectation that AMS, via their AICHR Representatives, will explain and justify their interpretation, thus providing a platform for argumentative discourse. In this respect, the hosting by Indonesia of the ASEAN Human Rights Dialogue 2021 on the 21 September, is potentially significant (AICHR, Citation2021a). It utilises precedent setting in two specific ways. First, it builds upon the precedent set in 2013 when the government of Indonesia initiated a human rights dialogue with AICHR representatives as an acknowledgment of the growing role of AICHR in the region (AICHR, Citation2013; Mazni, Citation2013). In 2017, in an activity jointly led by Representatives of Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia, AICHR hosted CSOs and ASEAN bodies to discuss the state of the AHRD and its implementation in the region (AICHR, Citation2017a) and subsequently in 2018, Thailand’s CSO symposium saw CSOs raising human rights cases before the Representatives (AICHR, Citation2018a). Dialogues on difficult and sensitive human rights issues are thus not new, but an attempt to initiate a consistent practice for member states to be comfortable talking about human rights. Second, the use of the word ‘dialogue’ is deliberate; dialogue is used 35 times in ASEAN Community’s Forging Ahead Together blueprint for 2016–2025, and thus by naming it the ASEAN Human Rights Dialogue it is presented as a component supporting the blueprint; ‘dialogue’ is even presented as part of ASEAN’s DNA (Wahyuningrum, Citation2021b). In 2022, the Indonesian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Retno Marsudi, associated dialogue with protecting human rights, confirmed that in November another ASEAN Human Rights Dialogue would be co-hosted by Cambodia and Indonesia, and expressed her desire that it would become an annual event (ANTARA, Citation2022; AICHR, Citation2022). If this ensures the Dialogue becomes institutionalised in AICHR practice, it has the potential to become a significant platform for argumentative discourse.

We now turn to examining instances of contestation in AICHR and will reveal the opportunities and the obstacles that exist in utilising persuasion. We divide the section into the scope conditions identified above: Regime Change; (De)centralised Governance; Social Vulnerability, and Material Vulnerability.

Contestation in AICHR

Regime change

Our argument is that if there exists an agreed interpretation amongst AICHR Representatives of AICHR’s ToR and the ASEAN Way, then AICHR’s governance structure (its regime) is robust, and thus AICHR, and more broadly member states, will be able to deflect, or even ignore, criticisms levelled at it. However, if AICHR’s governance structure is contested by AICHR Representatives then, depending on how successful they are, we can equate it to a regime that is in transition. To identify these acts of contestation we turn first to the ASEAN Way, and then the ToR. In the case of the ASEAN Way, since this applies to ASEAN as a whole and not AICHR specifically, contestation comes from Heads of State and/or foreign ministers.

ASEAN Way

The ASEAN Way provides the overarching framework for how ASEAN operates, and it is therefore appropriate that AICHR is guided by its core principles, notably non-interference in the internal affairs of AMS (ToR Article 2.1) and that decision-making shall be based on consultation and consensus (ToR Article 6.1). Given that human rights abuses occur within states and can be perpetrated by state authorities, it is hardly surprising that many critics contend these principles undermine AICHR’s ability to safeguard human rights. We argue though that these principles are not fixed in their meaning, but open to interpretation (Collins, Citation2019b). The ASEAN Way has evolved during the Association’s more than fifty years of existence, what is meant by non-interference was adjusted via ‘flexible engagement’ to include ‘enhanced interaction’, while equating consensus with unanimity ignores the long-standing principle of ASEAN Minus-X, which ensures no one member state can impose its views on others by wielding a veto. What the ASEAN Way means in any particular context is thus open to contestation, and, as the decision to exclude Myanmar’s junta chief, Min Aung Hlaing, from ASEAN’s 38th and 39th ASEAN Summits in October 2021 reveals, it has been and continues to be.

The decision taken at an emergency meeting of ASEAN foreign ministers on 15 October 2021 to replace Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, who headed Myanmar’s government and ruling military council, with a non-political representative from Myanmar, raised questions about ASEAN’s commitment to non-interference and consensus (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Citation2021). Malaysia’s Foreign Minister, Saifuddin Abdullah, for example, urged ASEAN to do some ‘soul-searching’ on its non-interference policy (Reuters, Citation2021). We contend that the unprecedented step taken by ASEAN’s heads of state to exclude one of their own from their summit, which continued throughout 2022, creates the conditions to problematise the ASEAN Way, thus enabling a reinterpretation that is more conducive for promoting/protecting human rights.

A reinterpretation is not a dismissal of these core principles, it is a framing that promotes a particular understanding of them. Thus, with consensus it is worth noting that Myanmar’s objection to the decision was dismissed in the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Chair’s statement as ‘noting the reservations from the Myanmar representative’ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Citation2021). In other words, reaffirming that consensus does not equate to providing each member a veto. It is also worth noting that replacing a junta representative with a non-political representative was done to assuage the concerns of Thailand, Laos and Vietnam and achieve the consensus needed to reach a decision (Robinson, Citation2021). As such, the outcome was a consensus minus Myanmar, which is the epitome of ASEAN Minus-X.

The willingness of Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and the Philippines to publicly suggest disinviting Min Aung Hlaing also reaffirms that non-interference is not indifference. The continuing levels of political violence in Myanmar following the 1 February coup—by the time of the October meeting civilian deaths were reportedly 1000—coupled to the refusal to allow ASEAN’s special envoy to meet with detained members of the National League for Democracy, including Aung San Suu Kyi, was sufficient evidence for these four members that Myanmar’s leadership was making insufficient progress in implementing ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus agreed in April. The consequence for ASEAN was that its credibility as an institution capable of resolving the latest Myanmar crisis would be damaged if it did nothing, and with its credibility lessened this would have the knock-on effect of lessening its significance and thus its much-vaunted centrality in wider East Asian affairs. Not for the first time, Myanmar’s future and ASEAN’s future are inextricably tied. ASEAN cannot afford to be indifferent.

However, rather than viewing this as evidence that non-interference no longer holds (Pongsudhirak, Citation2021) or is being foregone (Lintner, Citation2021), we should instead interpret it as evidence of how non-interference as practised continues to evolve. The AICHR meeting shortly after the coup saw one of the Representatives request an update on the situation in Myanmar. While the chairperson did not allow a full-blown discussion, Representatives were asked to have bilateral discussions with Myanmar if they were interested in knowing more. In this instance, non-interference did not preclude AICHR Representatives seeking information. Requesting for an ‘update’ or seeking ‘more information’ are commonly made by AICHR Representatives in meetings to politely signify their concerns about a particular pressing human rights issue. The language used makes it difficult for governments to argue that the ASEAN rule of non-interference is being breached. Crucially, it is becoming an institutionalised form of discussing controversial topics. Just as flexible engagement altered non-interference to enable states to better assist one another when facing transboundary problems, we can interpret ASEAN’s actions as seeking to assist Myanmar’s junta implement the agreed Five-Point Consensus. In this respect, ASEAN’s outgoing chair’s 38th and 39th summit statement is particularly revealing. Speaking on behalf of ASEAN, Brunei’s Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah stated:

While respecting the principle of non-interference, we reaffirmed our adherence to the rule of law, good governance, the principles of democracy and constitutional government as well as the need to strike an appropriate balance to the application of ASEAN principles on the situation in Myanmar. We agreed to reaffirm the decision reached by the Emergency ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting (EAMM) on 15 October 2021. We reiterated that Myanmar remains a member of the ASEAN family and recognised that Myanmar needs both time and political space to deal with its many and complex challenges. We expressed the view that Myanmar’s national preoccupation should not affect ASEAN Community building process and decision making. In this regard, we remain committed to support Myanmar in its efforts to return to normalcy in accordance with the will of the people of Myanmar (ASEAN, Citation2021).

Non-interference has never meant no interference. It is designed to assist member states, and where the problem has regional implications providing a means for the incumbent regime to solve the problem in such a manner that the regional implications are also resolved. What is new today seems to be that support for the regime has been made conditional on how it assumed power or how it exercises that power vis-à-vis its domestic constituents. The decision to disinvite Min Aung Hlaing was, in part, because of these considerations, and in 2022 continued with the junta barred from attending ASEAN meetings because of insufficient progress in implementing the Five-Point Consensus, and its resumption of the death penalty after three decades (ASEAN, Citation2022a). What is pertinent for AICHR is that concern about Myanmar’s abuse of human rights was just as prevalent as the junta’s refusal to allow ASEAN’s special envoy to meet detained president Win Myint and Aung San Suu Kyi. In the wake of the executions of four political prisoners in July 2022, ASEAN called the junta’s actions ‘reprehensible’, and while denouncing the executions noted how ASEAN was ‘strongly disappointed’ and takes the issue ‘seriously’ (ASEAN, Citation2022b). In other words, non-interference does not mean ASEAN is indifferent. Saifuddin’s invitation to do some ‘soul-searching’ about non-interference in the wake of the violence meted out by the regime towards its own people, provides AICHR Representatives with an opportunity to problematise the core principles that underpin its regime type and initiate a process of transition. Following Myanmar’s resumption of the death penalty, five AICHR Representatives (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand) issued a joint statement condemning the executions (Fernandez, Citation2022). Non-interference, and indeed consensus, are thus both ripe for reinterpretation.

Review of the ToR

One opportunity to reconsider the modus operandi that underpins AICHR is the provision within its ToR for the ToR to be reviewed (ToR Article 9.6). This was supposed to take place five years after the ToR’s entry into force, but such a review has not happened. Nevertheless, the process of conducting a review has begun. The first step was taken in 2019 when ASEAN foreign ministers agreed to establish a Panel of Experts. According to Eric Paulsen, the Malaysian AICHR Representative (2019–2021),

It is vital that the TOR review reconsiders how the consensus and non-interference principles are applied within the AICHR and how this can be done in a way that enhances its ability to advance human rights. Ensuring that alternative decision-making is available to the AICHR, in agreed circumstances and where there is no unanimous vote, would increase its capacity to do important work while remaining true to the founding principles of ASEAN (Paulsen, Citation2020).

Establishing an alternative decision-making procedure, we consider unlikely, but reconsidering, or contesting, the understandings of consensus and non-interference is important for specific recommendations to function effectively. Thus, Paulsen recommends that a review should include giving AICHR such powers and features as ‘receiving, investigating and deciding upon communications, carrying out on-site visits to investigate concerns, and being composed of members who are independent from government’ (2020). Recommendations designed to strengthen AICHR’s protection mandate. This desire for the transition of AICHR’s regime type towards a stronger, protection, body has continued.

On 23 July 2021, AICHR Thailand organised a regional dialogue on ‘Self-Assessment of AICHR Progress after 10 years’. One of the sessions, entitled ‘Summary and Ways Forward to Strengthen AICHR’s Protection Mandates’, had some government representatives as discussants. They agreed there was a need to review the ToR and address the imbalance between the promotion and protection mandates. In concert, the members were of like mind: that the ToR lacks mandate on protection. They shared the view that: (1) a complaint mechanism or a correspondence procedure to receive, investigate and address complaints from individuals and groups on human rights violations should be established; (2) protection can be advanced through the establishment of a complaint resolving mechanism, country visits and making recommendations regarding a human rights violation of a member state; (3) AICHR’s engagement with CSOs in the region should be conducted annually through consultations; and (4) since the activities of the AICHR involves different ASEAN sectoral bodies, AICHR could develop a list of recommendations from each activity and identify recommendations that are feasible for implementation and adoption. This last suggestion is significant for AICHR’s relationship with ASEAN sectoral bodies, a relationship we examine in the following section on governance structures. For now, what is evident is that governmental experts recognise that AICHR’s ToR needs to adjust and increase its protection mandate, thus rectifying the most serious criticism that it is not fit for purpose. This would represent a regime transition for AICHR. That is, a scope condition favourable for AICHR Representatives to assist AMS’ turn a commitment to human rights into complying with their human rights obligations. Although painfully slow, there is progress on enhancing protection within a revised ToR.

There remains another deficiency with AICHR’s governance structure, which could be addressed in the revision of its ToR or the Guidelines on the Operations of the AICHR, which is also subject to review once the ToR is revised (Guidelines Article 15.4) (AICHR, Citation2012). This deficiency concerns the transition arrangements for AICHR Representatives, which hinders their opportunity to turn commitments into compliance because of the lack of programme continuity when a new Representative is appointed. Representatives serve for three years and can be reappointed for another three years. Each year, or within the span of a Representative’s term of appointment, the Representatives individually can propose at least one priority programme.Footnote6 The Representatives have the freedom to propose—and subsequently implement—activities in any area of human rights, so long as the programmes are aligned with the ToR and supplements recommendations for the implementation of the AHRD. AICHR Representatives are not though bound, by norms and procedures, to continue the works of their predecessor. A change in Representative causes AICHR to lose chunks of its institutional memory. Recommendations in the implementation of the AHRD will face discontinuity when there is no build up from the previous AICHR activities or programmes. The sustainability of these initiatives is reliant on future Representatives taking the initiative to carry on activities based on previous recommendations but there is no requirement for them to do so. There have been institutional arrangements adopted to help with the transition of new Representatives, but the continuation of AICHR activities to help turn a commitment into a compliance remains contingent on the whim of newly appointed Representatives.Footnote7 The success noted earlier regarding the rights of persons with disabilities is in no small measure a consequence of Seree Nonthasoot holding two consecutive terms in office, and his successor, Amara Pongsapich, continuing to undertake a series of priority programmes in support of ASEAN’s Enabling Masterplan 2025. However, other programmes relating to the right to safe drinking water and sanitation, the rights of accused persons in criminal cases, and matters relating to trafficking-in-persons have stalled because of Representative change. A striking example of this is the Philippines Representative, Rosario Gonzales Manalo (2009–2015)—who was widely considered to have led AICHR on women’s rights programmes—proposal to establish an ASEAN Inter-Sectoral (Bodies) Technical Working Group on Women and Girls Human Rights (TWGWHR) in her final year on the commission. The TWGWHR was to be a platform for the numerous ASEAN mechanisms to work together in partnership to protect women rights and overcome the practice of working in silos. Reservations were expressed by some Representatives that AICHR had no power to set up the working group. A common way of assuaging doubting members was to offer to detail the initiative for further discussions and thus AICHR Philippines was tasked with it. After Manalo left the commission, there was no follow up action taken to move ahead with the TWGWHR by her successors. Therefore, a strong momentum of AICHR initiatives even on cross-cutting issues can be foiled when there is a turnover of Representatives. To ensure the continuity of AICHR’s activities and programmes, and thereby enhance the prospects of turning commitments into compliance, requires systemic change to AICHR’s governance structure so that its activities and programmes are retained when AICHR Representatives change.

As a scope condition, regime transition is critical because a robust regime can ward-off pressures to comply with human rights, which in this instance would equate to AICHR Representatives being hamstrung in their efforts to fulfil AICHR’s mandate by its modus operandi. The on-going human rights crisis in Myanmar has though provided an opportunity to contest ASEAN’s modus operandi—its ASEAN Way—and by implication AICHR’s regime. The specifics of which will be revealed in the deliberations over the review of its ToR. While it is evident that some progress towards a more robust protect mandate is being pursued, which would require a form of reinterpretation of non-interference and consensus decision-making, it is important that functional considerations, such as transition arrangements for new AICHR Representatives that can currently derail activities and stymie efforts to turn commitments into compliance, are also reviewed. Such functional considerations are also evident in the next scope condition, which is concerned with ASEAN’s human rights’ governance structure as it pertains to AICHR.

(De)centralised governance structure

This scope condition concerns the difficulty state authorities can have in achieving compliance when the authority to institutionalise international standards for human rights rests with provincial authorities because political power is devolved. AICHR is the ‘overarching human rights institution in ASEAN with overall responsibility for the promotion and protection of human rights in ASEAN’ (ToR Article 6.8). To achieve this it will, ‘work with all ASEAN sectoral bodies dealing with human rights to expeditiously determine the modalities for their ultimate alignment with the AICHR’ (ToR Article 6.9). The extent to which AICHR Representatives have been able to fulfil this mandate depends on how ‘alignment’ has been understood, and specifically how it relates to the hierarchy alluded to by ‘overarching’. This matters, because AICHR cannot turn commitments into compliance without the support of the domestic line agencies of each country. The agencies are represented by their nominated members in the ASEAN sectoral bodies. In effect, these regional sectoral bodies consist of national governmental officials from every AMS. We are thus interested in the understandings that AICHR Representatives have of these institutional structures, and the degree to which they are malleable as this gives important insight into what AICHR can accomplish.

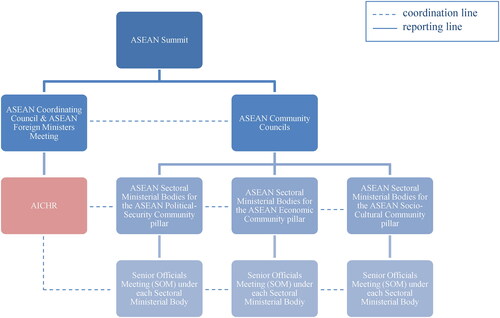

The constraints in ASEAN’s human rights’ governance structure can be clearly discerned in the working relationship AICHR has with other ASEAN bodies. As shown in , ASEAN has three community pillars dealing with political-security, economic and socio-cultural matters. Each pillar is administered by a Sectoral Ministerial Body. Ministers from the ten AMS constitute the body. Reporting to the Sectoral Ministerial Body is the respective Senior Official Meetings (SOMs) representing the relevant areas of activity. For example, the Senior Official Meeting on Transnational Crime (SOMTC) reports to the ASEAN Political-Security Community Sectoral Ministerial Body, which in this example is the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime (AMMTC). AICHR, as indicated in , acquires a level of independence and power as the overarching human rights mechanism in the region. Aside from reporting to the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting (AMM), coordinating with their respective Ministry of Foreign Affairs and aligning with their country’s foreign policies and position on human rights issues, AICHR Representatives have the liberty to express their opinions concerning human rights issues in the region and ‘develop strategies for the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms to complement the building of the ASEAN Community’ (ToR Article 4.1).

The challenge, however, lies along the dotted lines of coordination between AICHR and the ASEAN sectoral bodies (both at the ministerial and senior official levels) that has contributed to the discordance in practice. Insofar for AICHR’s role to be effective in turning a commitment into compliance, its relationship with its stakeholders, especially the ASEAN sectoral bodies, is critical. However, the guidance on this coordination undercuts AICHR’s authority. The specifics governing the engagement between AICHR and the sectoral bodies are contained in section 10 of the Guidelines on the Operations of the AICHR. The language does not authorise AICHR to require conformity by sectoral bodies, instead the working relationship is couched in phrases such as ‘recommend’, ‘request’, and AICHR can only attend sectoral bodies meetings by invitation. The line of authority between AICHR and ASEAN’s sectoral bodies is ambiguous: ‘The format and level of participation of such engagement will be determined through consultations by AICHR and relevant sectoral bodies’ (Guidelines Article 10.3) (AICHR, Citation2012). In practice, this has led to AICHR having difficulties in implementing its activities involving other ASEAN sectoral bodies with coordination challenging and inconsistent. At times, these mechanisms are hazed by their respective functions and mandate, thus leading to the duplication of work and uncertainty of ‘who leads what’.

In an example of ‘who leads what’, Dinna Wisnu, the Indonesian Representative to AICHR (2016–2018), recounted the difficulties she faced when organising AICHR’s second consultation in 2017 on the ASEAN Convention Against Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (ACTIP) with SOMTC.Footnote8 Because the ACTIP’s implementation is considered by ASEAN to be ‘owned’ by SOMTC, AICHR will be stymied if it wanted to work on anti-trafficking issues without SOMTC’s approval. Internally, AICHR Representatives knew that, and one member refused to approve Wisnu’s concept note and budget unless and until SOMTC had agreed to the programme. Essentially, a new prerequisite for collaboration was attempted to be set within AICHR before AICHR could engage external bodies such as SOMTC. It became a chicken-and-egg situation. Which was to come first: Seek SOMTC’s comments and then revert to AICHR or have AICHR’s approval before approaching SOMTC? To satisfy the sole dissenting voice in AICHR, Wisnu took the necessary steps to secure SOMTC’s collaboration in principle including fixing tentative dates and sharing the draft concept note for SOMTC’s comments. SOMTC requested several time extensions in reverting back to AICHR about the collaboration, and while AICHR agreed to these extensions it delayed AICHR’s decision on the programme. Then, in the middle of 2017, SOMTC’s chairperson changed and negotiations for collaboration had to be started again. One month before the scheduled programme, SOMTC wrote to say that it was not ready to collaborate on the activity and did not feel compelled to provide a reason. Undeterred, because by now AICHR did not voice objections to Wisnu’s programme and with preparations already underway, the venue booked, and budget sourced, it would not have shown AICHR in a good light if it withdrew the programme from its calendar, Wisnu proceeded to initiate the programme but not as a joint AICHR-SOMTC activity (AICHR, 2017c) as originally contemplated. SOMTC members were invited, and some did attend, however without formal SOMTC engagement, the implementation of the programme did not meet its full potential. It is easy to see how at two levels—within ASEAN and within the commission—AICHR’s work can in practice stall because it does not have a presence in, or control over, the sectoral agencies. In fact, the reverse is true. AICHR can be outflanked by sectoral bodies while internal Representative manoeuvres can be used to reduce its efficacy. Whether a precedent has been established that AICHR must obtain the prior consent of ASEAN sectoral bodies before joint programmes can be actualised, remains to be seen.

We conclude this section with an example of an attempt to establish a procedure for overcoming coordination problems caused by decentralisation. In 2015, AICHR organised a programme titled ‘Workshop on Strengthening AICHR’s Protection Mandate by Exploring Mechanisms and Strategies to Protect Women and Girls from Violence’, which was spearheaded by the Philippines AICHR Representative, Rosario Gonzales Manalo (2009–2015). As noted previously, AICHR’s agreement to establish TWGWHR came to nought after a change of the Philippine’s Representative. If TWGWHR had been formed, it would institutionalise cooperation between AICHR and other relevant bodies and align their programmes to protect women and girls’ human rights. Significantly, because AICHR cannot function without the support of the ASEAN sectoral bodies, this institutionalisation would tacitly draw these agencies closer towards AICHR. Although it was not established, the TWGWHR’s story reveals two significant findings. First, because ASEAN’s three pillar structure silos discussions and hinders AICHR’s ability to carry out its mandate, there is a need to create intersectoral bodies to align the activities of sectoral bodies on cross-cutting issues. Second, while there was stern opposition from some AICHR Representatives about AICHR’s authority to create an intersectoral body, Manalo’s status—she was undersecretary of Foreign Affairs in charge of International Economic Relations (1997–2001), served as a Philippine Ambassador, and chaired the High Level Task Force to draft the ASEAN Charter in 2007 and was also a member of the High Level Panel that drafted AICHR’s ToR—coupled with her strong personality, gave her sufficient authority to overcome the resistance. This also suggests that the stature of the Representatives, particularly those who hold, or held, senior roles in their government bureaucracy, plays a part in them being able to overcome objections to their proposals.

The decentralised governance structure therefore means AICHR’s status as a Charter body that has overarching responsibility for the promotion and protection of human rights in the region is not as empowering as it appears to be. It disconnects AICHR’s ambitions for human rights from their implementation and the behavioural change needed from enforcement agencies. Despite its Charter-body status as the first among the rest, AICHR’s decentralisation has instead become a handicap as it cannot work without the cooperation of the other agencies. The TWGWHR and the ACTIP consultation are concrete illustrations of this. AICHR cannot take any initiative on human rights unless there is inter-sectoral support in place. Thus, while the structure in theory appears straightforward and feasible for a smooth, direct coordination to occur between AICHR and the sectoral bodies, practice reveals otherwise, and while there is evidence of contestation to overcome these co-ordination problems, it remains problematic.

Social vulnerability

The scope condition social vulnerability captures the ability to shame an actor into altering their behaviour by accusing them of failing to uphold international standards of human rights. The more an actor is sensitive to its image being tarnished the more susceptible it is to this type of pressure. Since AICHR is a representation of ASEAN’s commitment to human rights, actions and inactions by AICHR carry reputational costs for the Association and its member states.

For this scope condition we are therefore interested in discerning the extent to which AICHR Representatives can establish standards by which AMS can be held accountable for their (in)actions. That is, and here we are explicitly ascribing to the Representatives the agency to alter a scope condition, establish the criteria for the scope condition, social vulnerability. In essence, it is only possible to engage in argumentative discourse to promote/protect human rights if there is consensus, albeit one subject to contestation, as to what constitutes human rights and what constitutes promotion and protection of them. AICHR silence in the face of human rights abuse indicates that no AMS reputational harm comes from either ignoring abuses committed or being culpable for the abuse. We are thus interested in both AICHR action and inaction.

AICHR action

We begin with an action, the AHRD that AICHR drafted and was adopted by AMS on the 18 November 2012. This was widely decried as inadequate, and even counterproductive, with a focus on Articles 6, 7, and 8, which were specifically criticised for undermining rather than reaffirming international standards of human rights by stating: rights must be balanced with duties; rights were subject to many limitations including public morality; and rights were not universal but dependent on national particularities (OHCHR, Citation2012; Petcharamesree, Citation2013). We have detailed elsewhere the then Malaysian AICHR Representative, Edmund Bon Tai Soon’s, purposive interpretation of Articles 6, 7, and 8, so that the AHRD can be interpreted as upholding minimum international standards of human rights (Bon, Citation2016; Collins, Citation2019a, pp. 386–387). We contend that evidence of AICHR Representatives making recourse to the AHRD in defending human rights is critical for two reasons. First, given the AHRD is regarded as inadequate by human rights activists, interpreting its provisions and framing abuses as contravening the AHRD affirms its value in establishing what constitutes breaches of human rights. In other words, the AHRD can be used to draw attention to abuses and even shame member states, rather than, as feared by human rights activists, excuse or even exonerate member states. Second, as an ASEAN declaration it cannot be dismissed by AMS as inapposite.

There have been several recent examples of AICHR Representatives utilising the AHRD to promote human rights. For example, in 2017, Bon sought to push for a joint general comment-like document from AICHR on the right to water and sanitation protected by Article 28 of the AHRD (AICHR, Citation2017b) while Wisnu in 2018 hosted a workshop titled ‘AICHR Capacity Building Workshop on Article 14 of ASEAN Human Rights Declaration’ to establish a common understanding of Article 14 of the AHRD and explore ways to prevent torture (AICHR, Citation2018b). In December 2020, Yuyun Wahyuningrum, the Indonesian AICHR Representative (2019-present), organised an activity focusing on the same Article 14 provision (AICHR, Citation2020). The goal of the consultation, which remains ongoing, is to develop what an ASEAN torture-free Community should look like. In essence, Indonesia was, by utilising the AHRD, attempting to establish what actions constitute torture and thus what actions, if undertaken, is a breach of human rights law.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the AHRD was utilised by Wahyuningrum to support the provision of appropriate health care by highlighting three provisions concerned with the right to health: (a) the right to medical care and necessary social services as part of an adequate standard of living (Article 28.d), (b) basic and affordable health care services and medical facilities (Article 29.1), and (c) countering discrimination for the victims of communicable disease (Article 29.2) (Wahyuningrum, Citation2020a). In so doing, Wahyuningrum is reaffirming the obligations of governments to ensure rights are safeguarded during the pandemic, and what would constitute a breach of human rights. Wahyuningrum has also gone as far as to use the AHRD to shame a member state when she deplored the signing of the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 by Philippine President Duterte. She noted how this legislation contravened rights guaranteed in the AHRD, such as freedom from arbitrary arrest or detention (Article 12), and the guarantee of freedom of opinion, expression, and peaceful assembly (Articles 23 and 24) (Wahyuningrum, Citation2020b).

By utilising the AHRD to promote and protect human rights these assertions reveal how AICHR Representatives can draw attention to AMS commitments, and implicitly/explicitly reveal instances where compliance is inadequate and could be better. The utilisation of the AHRD with recourse to its provisions is evidence of argumentative discourse, and confirms the aspiration that Marty Natalegawa, the former Indonesian foreign minister, had of the AHRD that it ‘must contain in-built adaptive features’ (Natalegawa, Citation2018, p. 209). It could be argued that the lack of a counter to these public interpretations of the AHRD does not reveal agreement, but a preference to stymie discussion by simply dismissing them as the position of one Representative, and thus not representative of AICHR as a whole. This is true, but we contend that by making a public stance AICHR can be forced to engage. This is evident in what begins as an example of AICHR inaction.

AICHR inaction

The social vulnerability that arises from inaction has been palpable, with considerable criticism levelled at AICHR, the institution of ASEAN, and AMS in their response to the crises that have afflicted Myanmar (Thamrin, Citation2018). These crises range from the accusation of genocide levelled at Myanmar’s military for the violence perpetrated against the Rohingya, to the military junta’s crackdown on protestors following the military coup in February 2021. A failure to act decisively can do reputational harm to ASEAN and consequently, as Malaysia’s former AICHR Representative, Eric Paulsen notes, lead actors to seek solutions via alternative bodies, such as the International Court of Justice (ICJ).Footnote9

In April 2021, AICHR issued its first comments on the violence in Myanmar, expressing its concern about the escalation of violence and its ‘readiness to assist Myanmar in any tasks as may be assigned by the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting’ (AICHR, Citation2021b). To understand how AICHR reached this position we need to begin three years previously, when on 23 April 2018 two AICHR Representatives, the then Indonesian Representative, Dinna Wisnu and Malaysian Representative, Edmund Bon Tai Soon, issued a joint statement on the refugee and human rights crisis occurring in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. Utilising the AHRD, specifically Article 2 on rights and freedoms, they recommended a ‘whole-of-ASEAN’ approach as a solution, with AICHR ‘tasked to lead the initiative’ (Wisnu & Bon, Citation2018). What was particularly revealing was they concluded by expressing frustration with AICHR’s unwillingness to act, and how this inaction damaged the body’s reputation. They wrote:

We have exhausted the possible avenues presently available within the AICHR. Time is precious. We can no longer sit by idly even for one day while the crisis continues, or we will eventually have to account for the AICHR’s collective silence. As Representatives of the AICHR tasked by the AICHR’s Terms of Reference, we, as individual Representatives, make this joint statement in furtherance of our impartial discharge of our duties to promote and protect human rights in the region. With this, we sincerely hope that the ASEAN Leaders will consider our recommendations, and keep the AICHR informed and aligned on the inside track with plans to handle the crisis in Rakhine (Wisnu & Bon, Citation2018).

Material vulnerability

The final scope condition refers to how offering material inducements can persuade a state to comply with human rights, such as tying aid packages to an improving human rights’ record. Material vulnerability is thus the condition that makes the state more susceptible to persuasion; the poorer they are, the more vulnerable they are to external pressure. In this instance, we are adjusting this scope condition and equating it to AICHR’s funding to reveal how limitations on its funding can constrain how AICHR Representatives can turn a commitment into a compliance. In essence, a cap on its budget and limitations to what it can use the funding for, reveals a material vulnerability that can undermine or negate AICHR Representatives’ activities.

AICHR conducts its activities and programmes with revenue from the AICHR Fund and ASEAN dialogue partners.Footnote10 The funding from dialogue partners depends on the areas of human rights the proponent aims to carry out, although it is important to note that AICHR retains ownership of the programmes or activities regardless of the source of funding, and that the AMM approves the utilisation of the funding.

In terms of limitations, the ToR restricts funding from non-ASEAN member states solely for human rights promotion, capacity building and education (ToR article 8.6). Therefore, funds from external dialogue partners cannot be used for ‘protection’ activities, although it is unclear what protection means in this context as the lines between promotion and protection have not been spelt out. The issue of funding as a constraint on AICHR activities arose in 2018 when there was a growing concern about the increasing number of activities AICHR was doing. Such activities could not have been done had it not been for external donor support. If such funding is capped, there would be a smaller budget available to AICHR for its activities. There would be fewer programmes. In ASEAN diplomacy, blocking an initiative on substance for the flimsiest of reasons causes one to ‘lose face’ in front of other member states. Hence an alternative tactic is to attack the procedure through budget control under the pretext of ‘streamlining’ the operations of AICHR and ‘tightening’ its financial management. Some Representatives wanted to revise AICHR’s rules. They proposed, among others, a limit to the number of AICHR meetings and activities a year, and a cap on how much of external funds may be used. This move was heavily contested. Each AICHR activity on average costs upwards of USD60,000. If a funding cap is placed, it meant that some countries were in no position to organise any activities because they had to self-fund the same. Further, some Representatives were leading AICHR on more than one thematic issue and with a cap, they had to give up on important issues. The proposal, to some, was unrealistic. It would impede the progress AICHR was making since its inception. There was no consensus within AICHR.

AICHR’s ‘non-consensus’ was subsequently bypassed, when in early 2018 AMM agreed to cap external funding for AICHR’s programmes. The argument made for the cap was to ‘assert’ ASEAN’s ownership over AICHR’s activities. Taken aback by the decision, several Representatives voiced their disquiet and raised the matter with their respective foreign ministries and ministers. It was apparent that the matter was escalated to AMM to push through the proposal even after AICHR disagreed with it. The contestation over the decision continued until the last month of 2018 when AICHR was informed that there would be no such cap.

In spite of the much-vaunted centrality and consultation practice of ASEAN, the bypassing of AICHR to directly seek AMM’s decision tells us something about AICHR’s vulnerability. By appealing directly to AMM, which is the body AICHR is answerable to, it not only sets a precedent but illustrates how a position that does not have consensus support in AICHR can be foisted on it in the name of good governance. Also, for our purposes, it reveals that some governments will not hesitate to capitalise on an AICHR vulnerability—limited resources—to handicap AICHR even in the face of resistance from others within the body. Whether the matter is reconsidered by AMM will therefore be an important indicator of whether this scope condition remains a hindrance to AICHR Representatives. Its significance cannot be understated. The capping proposal came about only because AICHR’s activities dramatically increased, and thus the proposal was designed by those who wanted to limit AICHR’s ability to turn commitments into compliance.

Conclusion

Writing before her appointment as Indonesia’s AICHR Representative, Wahyuningrum had argued that because AICHR has no formal mechanisms to evolve as its ToR stipulates, the onus falls on the Representatives ‘to creatively interpret their functions, explain the complexity of decision-making, and establish practices towards protecting human rights in the region’ (Wahyuningrum, 2018). It is a mantra she has pursued with vigour as an AICHR Representative, albeit often, at least publicly, alone with the occasional public support from other AICHR Representatives, notably Malaysia.

In the original Spiral Model, the authors assert, ‘Actors’ identities may…be reshaped through discursive processes of argumentation and persuasion’ (Risse et al., Citation1999, p. 236). We concur but note that because identities are always subject to change and human rights are perpetually contested, reshaping actors’ identities through discourses of persuasion is itself never-ending. It begins by gaining support for a particular interpretation of a human right and the modes to promote and protect it. In the case of AICHR, identifying the scope conditions is essential for revealing what structural obstacles exist that impede discourses of persuasion, and recognising that these scope conditions are not necessarily fixed but open to alteration via discourses of persuasion.

We have shown in this article that for Representatives to succeed in enabling AICHR to evolve we must appreciate the context (scope conditions) that prevail. There are reasons to be optimistic. Regime transition is critical, it provides the opportunity to contest the prevailing structures (the ToR) and modus operandi (ASEAN Way), and we have shown that both are being contested as argumentative discourse has called for soul searching about non-interference and for its structure to adopt alternative decision-making procedures. It is evident that AICHR, and AMS more broadly, are socially vulnerable to the accusation of inaction in the face of human suffering, resulting in AICHR publicly expressing its concern about the violence in Myanmar and its willingness to be part of an ASEAN solution. We have though also revealed that there exist scope conditions that hinder AICHR. ASEAN’s human rights governance structure resembles a decentralised governing framework, in which AICHR has no authority to require the implementation of its decisions. The embedding and mainstreaming of human rights practice into ASEAN activities via ASEAN sectoral bodies, which manifests turning a commitment into compliance, is dependent on the willingness of sectoral bodies to engage AICHR. As we have shown, while Representatives have contested it, such coordination is challenging and inconsistent. Finally, material vulnerability, has revealed the difficulties AICHR Representatives face in securing sufficient funds to carry out their activities. The conflating of AICHR’s sources of funding with its independence is an example of successful argumentative discourse to constrain the activities of AICHR Representatives. However, this example revealed that because not all of the Representatives were persuaded to set a budgetary cap, an appeal was mobilised directly to AMM. This sets a precedent. The budgetary cap was not popular with several AICHR Representatives and thus could be challenged by recourse to AMM. More broadly, it could indicate that deadlock in AICHR over any interpretation of what AICHR can (or not) do may be overcome by recourse to the AMM. With a new cohort of Representatives beginning in 2022, including Wahyuningrum for a second term, AICHR’s future direction will be determined by their ability to creatively interpret and mould AICHR’s scope conditions.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Umavathni Vathanaganthan of the Collective of Applied Law & Legal Realism (CALR) for her research assistance and contribution to this article. We are also grateful to comments from Dr Matthew Wall.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alan Collins

Alan Collins is a Professor of International Relations in the Department of Politics, Philosophy, and International Relations at Swansea University, UK. He is the author of four single-authored books, including Building a People-Oriented Security Community the ASEAN Way, and his 18 writings on ASEAN and Southeast Asian security have appeared in International Relations, The Pacific Review, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, and the Australian Journal of International Affairs.

Edmund Bon Tai Soon

Edmund Bon Tai Soon was the former Representative of Malaysia to the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (2016–2018) and is currently a doctoral candidate in human rights and peace studies at the Institute of Human Rights and Peace Studies, Mahidol University, Thailand. He is the co-author of the Halsbury’s Laws of Malaysia on ‘Citizenship, Immigration, National Security and the Police’ (Volume 27, 2010), and is the co-founder of the well-known law blog, LoyarBurok.com, and two organisations: the Malaysian Centre for Constitutionalism & Human Rights (MCCHR) and the Collective of Applied Law & Legal Realism (CALR).

Notes

1 For the authors’ rejection of linear progression in the Spiral Model see Risse, Ropp, & Sikkink (Citation2013, p. 33). For the sequencing, see Sikkink (Citation2013).

2 The first two scope conditions are (1) regime type and (2) consolidated/limited statehood. For the purposes of this article, we conflate (2) with their third scope condition, which is centralized vs decentralized rule implementation (Risse, Ropp, & Sikkink, Citation2013, pp. 16–19) and label it (de)centralised governance structure.

3 For their recognition of their error of thinking that the unidirectional travel for human rights is based on the strength that arguing in favour of human rights was inherently stronger than arguing against, see Risse, Ropp, & Sikkink (Citation2013, p. 15).

4 A good example of including the will of the people can be seen in Malaysia’s Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah’s promotion of talks with the National Unity Government (NUG), which is the opposition “shadow” government of Myanmar, made up of elected leaders who were overthrown by the military coup in February 2021. Saifuddin held talks with the NUG leader, Zin Mar Aung, on the sidelines of the US-ASEAN Summit held in May 2022 and called for ASEAN to hold “informal” talks with the NUG. Saifuddin also called for the role of the special envoy to be enhanced in June 2022. See Sim (Citation2022).

5 This support can be seen in ASEAN rejecting Saifuddin’s request to hold informal talks with the NUG.

6 AICHR Representatives are not obligated to propose a programme. Over the years, a few of the Member States are found to be less keen in proposing to implement a priority programme.

7 The AICHR had conducted three transition workshops for newly appointed Representatives: on 3 February 2016 in Vientiane, Lao PDR, 19 March 2019 in Bangkok, Thailand, and a virtual workshop because of COVID restrictions on 29 March 2022.

8 Interview with Dinna Prapto Raharja (then known as Dinna Wisnu), 18 July 2022.

9 When Malaysia regarded ASEAN’s response to the Rohingya crisis in 2017 inadequate, Malaysia turned to the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) to pursue a solution. The OIC subsequently supported Gambia in bringing the case of genocide against Myanmar to the ICJ. Eric Paulsen warned that if ASEAN failed to respond to the ICJ’s measures, it risks, ‘becoming a bystander while the resolution to the Rohingya crisis is sought elsewhere’ (Barber & Teitt, Citation2020, p. 44).

10 Dialogue partners include the European Union, China, Japan, Canada, Australia, the United States of America, and the United Kingdom.

References

- AICHR. (2009). ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (Terms of Reference). ASEAN Secretariat, October. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TOR-of-AICHR.pdf

- AICHR. (2012). Guidelines on the Operations of the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR). ASEAN Secretariat. 12 March. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Guidelines_on_the_Operations_of_AICHR.pdf

- AICHR. (2013). ASEAN Human Rights Dialogue with the Government of Indonesia, 25 June. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/news/asean-human-rights-dialogue-with-the-government-of-indonesia/

- AICHR. (2017a). AICHR reviews ASEAN’s implementation of the AHRD with partners, SOMs and CSOs, 30 November. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/news/aichr-reviews-aseans-implementation-of-the-ahrd-with-partners-soms-and-csos/

- AICHR. (2017b). Press Release: ASEAN meets to develop a common approach and position on the right to safe drinking water & sanitation under Article 28(e) of the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration 2012 (AHRD), 27 October. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/news/press-release-asean-meets-to-develop-a-common-approach-and-position-on-the-right-to-safe-drinking-water-sanitation-under-article-28e-of-the-asean-human-rights-declaration-2012-ahrd/

- AICHR. (2017c). Press Release: AICHR Cross-Sectoral Consultation on the human rights based instruments related to the implementation of the ASEAN Convention Against Trafficking in Person, especially Women and Children, 29-30 August 2017, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. 30 August. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/news/press-release-aichr-cross-sectoral-consultation-on-the-human-rights-based-instruments-related-to-the-implementation-of-the-asean-convention-against-trafficking-in-person-especially-women-and-childre/

- AICHR. (2018a). Press Release: AICHR CSO Symposium, 13-15 October 2018, Chiang Rai, Thailand, 15 October. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/news/press-release-aichr-cso-symposium-13-15-october-2018-chiang-rai-thailand/

- AICHR. (2018b). AICHR Capacity Building Workshop on Article 14 of ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, 14-15 August 2018, Semarang, Indonesia, 15 August. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/news/aichr-capacity-building-workshop-on-article-14-of-asean-human-rights-declaration-14-15-august-2018-semarang-indonesia/

- AICHR. (2020). AICHR holds another consultation on the prevention and countering torture in ASEAN. 3 December. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/news/aichr-holds-another-consultation-on-the-prevention-and-countering-torture-in-asean/

- AICHR. (2021a). ASEAN Human Rights Dialogue 2021 was convened successfully. 21 September. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/news/asean-human-rights-dialogue-2021-was-convened-successfully/.

- AICHR (2021b). Press Release 33rd Meeting of the AICHR, 6-8 April 2021, Video Conference. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/news/press-release-33rd-meeting-of-the-aichr-6-8-april-2021-video-conference/

- AICHR. (2022). ASEAN member states reaffirm their commitment to human rights dialogue, 19 November. Retrieved from https://aichr.org/news/asean-member-states-reaffirm-their-commitment-to-human-rights-dialogue/

- AICHR Indonesia. (2021). The 11th AMM-AICHR Interface Meeting was completed today, 02.08.2021. 2 August. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/IndonesiaAICHR

- Alhargan, R. A. (2012). The impact of the UN human rights system and human rights INGOs on the Saudi Government with special reference to the spiral model. The International Journal of Human Rights, 16(4), 598–623. doi:10.1080/13642987.2011.626772

- ANTARA. (2022). Foreign Minister underscores importance of strengthening AICHR’s work. ANTARA Indonesian News Agency, 10 August. Retrieved from https://en.antaranews.com/news/242581/foreign-minister-underscores-importance-of-strengthening-aichrs-work

- ASEAN. (2013). Bali Declaration on the Enhancement of the Role and Participation of the Persons with Disabilities in ASEAN Community and the Mobilisation Framework of the ASEAN Decade of Persons with Disabilities 2011-2020. ASEAN Secretariat. Retrieved from https://cil.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/formidable/18/2011-Bali-declaration-on-persons-with-disabilities.pdf

- ASEAN. (2019). ASEAN Enabling Masterplan 2025: Mainstreaming the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, February. ASEAN Secretariat. Retrieved from https://asean.org/storage/2019/03/Publication-ASEAN-Enabling-Masterplan-2025-1.pdf

- ASEAN. (2021). Chairman’s Statement of the 38th And 39th ASEAN summits. 26 October. ASEAN Secretariat. Retrieved from https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/FINAL-Chairmans-Statement-of-the-38th-and-39th-ASEAN-Summits-26-Oct….pdf

- ASEAN. (2022a). Joint Communiqué of the 55th ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting. 3 August. Retrieved from https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Joint_Communique-of-the-55th-AMM-FINAL.pdf

- ASEAN. (2022b). ASEAN Chairman’s Statement on the Execution of Four Opposition Activists in Myanmar. 25 July. Retrieved from https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/final-2-Eng-Chairmans-statement-on-execution.pdf

- Barber, R., & Teitt, S. (2020). The Rohingya crisis: Can ASEAN salvage its credibility? Survival, 62(5), 41–54. doi:10.1080/00396338.2020.1819642

- Bloomfield, A. (2016). Norm antipreneurs and theorising resistance to normative change. Review of International Studies, 42(2), 310–333. doi:10.1017/S026021051500025X

- Bon, E. T. S. (2016). General observation no. 1/2016: Interpretation of Articles 6, 7 & 8 of the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration 2012. 23 September. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/aichrmalaysia/posts/2014433755460940