Abstract

As China’s power grows, a widespread perception is that China is more willing to respond to nationalist demands and act assertively in international incidents. In reality, China has not supported and accommodated nationalism in all events but has cooled down nationalism in some cases. An important unanswered question is, why does the Chinese government demonstrate selectivity when responding to nationalism and take different foreign policies concerning nationalism in various incidents? This article provides a coherent and testable framework to answer this question and uses five cases to test the congruence and validity of the analytical framework. The core argument is that the primary concern of the Chinese government in dealing with nationalism is its legitimacy. When policymakers perceive severe threats to China’s regime security and stability, they will open a ‘safety valve’ to embrace nationalism, allowing nationalism to unleash its anger under the government’s monitor and escalating disputes to defend national interests and appease nationalism. When there are few threats to the regime, three factors will affect China’s choice: the economic value of the diplomatic relationship, elements of China’s core interests, and the viability of reaching an agreement that sets aside the dispute.

Introduction

China has made remarkable economic achievements in the past decades, and its relative strength has increased tremendously. Meanwhile, its rise has also concerned other countries, especially its neighbours, and a critical development is the Chinese government’s increasing willingness to accommodate public sentiments (Neo & Xiang, Citation2022). Some argue that these policies embrace an assertive nationalism that has increased because of China’s enhanced power, and they can divert public attention from issues such as inequality and slowing economic growth (Moore, Citation2014; Ross, Citation2013). However, it is still unclear to what extent Chinese foreign policy is actually under pressure from nationalism (Duan, Citation2017; Johnston, Citation2013).

One significant puzzle remains when examining the Chinese government’s selectivity and different responses to nationalism in international incidents and disputes. In some cases, it has reacted to nationalism actively: voicing nationalist demands has been allowed and even supported, and the state took escalating measures in disputed incidents. Sometimes in other cases, nationalist sentiments were contained, and the state acted with great restraint externally. Therefore, a unitary and complete explanatory framework to explain the Chinese government’s handling of nationalist demands in international incidents is still obscure. Thus, the research question that this paper attempts to answer is: why and under what condition would the Chinese foreign policy be willing to embrace nationalism in some international incidents but more inclined to repress it in others? In doing so, this research helps us understand how the Communist Party of China (CPC) views nationalism and what factors affect its policymaking. This paper contributes to understanding the linkage among Chinese public opinion, domestic politics, and foreign policies by offering a clear testable analytical framework and bringing new insights into elucidating China’s decision-making process.

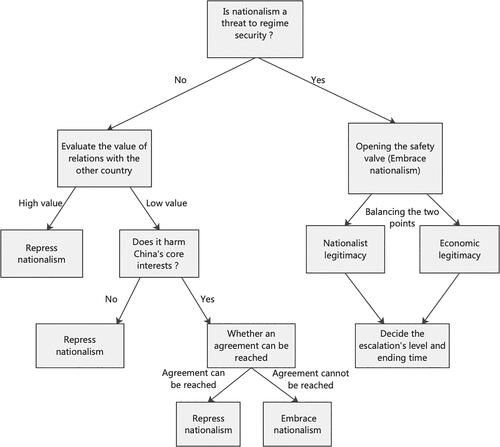

This research will specify a sequence of decision-making where the Chinese government will first assess whether nationalism associated with a specific incident threatens regime security. If yes, it would open a ‘safety valve’ to release domestic political pressure. China will embrace nationalism to appease public anger, meaning that Chinese foreign policy will actively respond to nationalist demands and take escalation measures. Examples include escalating economic sanctions, large-scale military exercises and patrols, suspension of high-level meetings and exchanges, etc. What measures to take and what time to end them primarily depend on the government’s calculation between its nationalist and economic legitimacy, which means the Chinese government would not completely follow nationalist demands when embracing nationalism. When an international incident does not affect either nationalist or economic legitimacy but undermines elements of China’s core interests, and no agreement can be reached, the Chinese government will also embrace nationalism to defend its national interests and gain public support. Under other circumstances, the Chinese government usually represses nationalism in international incidents. Repressing nationalism does not mean ‘suppressing nationalism’ internally and ‘doing nothing’ externally, as taking appropriate equal-level countermeasures targeting the other country in international incidents is expected as normal reactions. However, when repressing nationalism, China’s foreign policy will neither follow harsh nationalist demands nor take substantive and extraordinary measures to escalate the situation.

The research findings indicate that China’s foreign policy concerning nationalism is a situation-based approach rather than a doctrinal one. This means that ‘pragmatic’ may be more accurate than the widespread word ‘instrumentalist’ to describe the Chinese government’s handling of nationalism, although the two concepts overlap in terms of concrete manifestations. Such pragmatic handling of nationalism often means that the government can use nationalism as an instrument to increase domestic support or send external diplomatic signals. However, nationalism can bring risks to the government and costs to economic legitimacy. Therefore, the Chinese government usually handles nationalism pragmatically according to the specific situation.

This paper will follow a deductive analytical approach and conduct a qualitative study to reveal why China’s foreign policies towards nationalism differ in various incidents. For the time scope, this research investigates Chinese nationalism since the 1990s, when Chinese nationalism rooted in humiliation has not only appeared in the news media but also been repeatedly brought up on events like National Humiliation Day, national patriotic education, and cultural platforms (Callahan, Citation2006; Gustafsson, Citation2014). We define international incidents as unpleasant or unusual events with potentially grave consequences, especially in diplomatic matters, and they usually occur between countries or between citizens and organisations from different countries. This paper primarily examines international incidents between China and other states, as state-to-state disputes and crises are more critical in China’s foreign policies and usually have significant long-term effects.

This research employs a case study approach to test the framework. The cases included the 1999 bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade, the 2001 aircraft collision, the 2012 Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands dispute, the South China Sea arbitration, and the arrest of Huawei’s CFO, Meng Wanzhou. The above case selection is motivated by several considerations. First, to enhance the cases’ diversity, the case selection includes cases from different regions and countries that vary in power, historical relationship with China, and their economic and strategic value to China. We also choose cases of different nature and severity, including sovereignty disputes and an incident involving economic and technological competition. Also, they test different components of the comprehensive framework. Lastly, the case selection scheme uses a longitudinal timeline encompassing three generations of Chinese leadership. In doing so, the factor of time and leadership styles are considered. Furthermore, both authoritative primary and secondary sources will be used in this paper.

The primary contribution of this research is to offer China observers a clear, comprehensive, and testable analytical framework to explain what factors and conditions affect China’s handling of nationalism. Meanwhile, we also need to point out the potential limitations of the framework and the case selection. First, the framework does not seek to explain incidents between China and other non-state actors, like the ‘insulting China’ (辱华) behaviours of foreign brands and China’s sanctions against foreign individuals and non-official organisations. The Chinese government tends to behave more assertively when dealing with disputes with them because it considers such policies will not significantly harm its economic legitimacy but increase its nationalist legitimacy. Second, this paper does not include more cases due to space limitations. This paper selects representative contentious international incidents in the past decades to test the usefulness of its framework. Except for the Huawei/Meng Wanzhou incident, most include sovereignty issues, constituting a significant part of international incidents with widespread Chinese nationalism. This means the framework’s validity might be more robust in explaining sovereignty issues than non-sovereignty incidents.

This paper consists of five major sections. Following this introduction, the next section critically reviews the related literature concerning Chinese nationalism and foreign policymaking, and we give our conceptualisation of Chinese nationalism in this research. After that, we will present the analytical framework of how the Chinese government responds to nationalism when international incidents occur. Then, we will empirically analyse five incidents to test the framework. In the conclusion, potential trends in the influence of nationalism on the analytical framework and decision-making outcomes are revealed, which complements the framework proposed in this paper.

Chinese nationalism

The concept of nationalism is diverse. A broad concept of nationalism can represent a distinct sense of belonging to an identity, which can be ethnic, religious, linguistic, cultural, historical, or a combination of these attributes (Modongal, Citation2016). Nationalism can have a narrower definition as an ideology that asserts the nation’s historical uniqueness, the land that a nation should occupy, and the relationship that a nation-state should have with other nations (Haas, Citation1986, pp. 726–734). Nationalism has both positive and negative effects. For example, nationalism as an ‘invented tradition’ can contribute to national unity and solidarity against colonialism (Aydin et al., Citation2022). Instead, Schrock-Jacobson (Citation2012) suggests that sometimes nationalism can lead to xenophobia, conflict, and even war.

Defining Chinese nationalism is a thorny problem because the concept of nationalism is based upon analyses of European history, which does not apply well to China (Gries, Citation2004, p. 8). This paper seeks to contribute to bridging the gap between Chinese nationalism and foreign policymaking. Current literature on this relationship dominantly regards Chinese nationalism as a popular sentiment among the Chinese people regarding China’s relationship with other countries. Accordingly, this paper defines Chinese nationalism as a self-affirming, cohesive, and irrational ideology within the Chinese public concerning the nation-state’s relationship with and foreign policy towards other countries. This conceptualisation of nationalism is close to the definition of nationalism given by Haas and the concept of popular nationalism, so this paper does not make further distinctions between nationalism and popular nationalism in the context of China.

A debate in the studies of Chinese nationalism is whether it is mainly top-down or bottom-up. Chinese nationalism developed amid internal and external troubles. Since the nineteenth century, China has been defeated repeatedly by the Western powers and Japan in the ‘century of humiliation’. Against this background, the Self-Strengthening Movement starting in the 1860s and the Reform Movement in the 1890s offered critical soil for the growth of Chinese nationalism. The elite intellectuals of the time, such as Liang Qichao, Sun Yat-sen and Feng Youlan, made efforts to replace culturalism with nationalism as a means of saving the country (Chen, Citation2005, p. 38). In this sense, Chinese nationalism came from the top down (Moore, Citation2014). Nowadays, state-led nationalism, instead of elite-led nationalism, often shares dominance in top-down nationalism in China. Suisheng Zhao (Citation1998) argues that the state’s return to nationalism as a public narrative and through patriotic educational movements was a means of resolving its legitimacy crisis. Likely, some scholars argue that nationalism is now more important than communism in mobilising people’s support for the Chinese political system (Weatherley & Zhang, Citation2017; Zhao, Citation2017, p. 77).

Bottom-up nationalism, similar to popular nationalism, has become increasingly overwhelming in China since the 1990s, with components of traditionalism, neo-conservatism, and Say No-ism (Chen, Citation2005, p. 50). As Wang (Citation2008, p. 800) notes, stories of humiliation can be learned not only in textbooks but also heard from parents and grandparents. Duan (Citation2017) also argues that nationalism is not just an elite tool but has a more complex historical and political context. The latest evidence of bottom-up nationalism comes from observations of anti-Japanese nationalism and online nationalism (Cairns & Carlson, Citation2016; Zhang, Liu, & Wen, Citation2018). Gries (Citation2004, p. 125) also argues that the Chinese government does not have a monopoly on nationalism and emphasises the co-existence of top-down nationalism and bottom-up nationalism.

Although top-down nationalism and bottom-up nationalism demonstrate different features, they are interrelated with each other. The patriotic educational movements have enhanced Chinese people’s sense of isolation between ‘self’ and ‘others’. Moreover, in recent years, the Chinese government’s external behaviours and internal efforts targeting domestic audiences regarding China’s rising power and rejuvenation greatly satisfy bottom-up popular nationalism. While our research considers the multifaceted nature of nationalism and the co-existence of both top-down and bottom-up forms within Chinese society, this paper pays more attention to the bottom-up popular nationalism that the Chinese government needs to monitor, particularly during the outbreak of international incidents.

Some enlightening studies give us insights to understand what role nationalism plays in foreign policy and when officials are willing to respond to it. Shirk (Citation2008) argues that Chinese leaders will inevitably be influenced by nationalism, as Chinese nationalism is sensitive and angry about the contempt of the US, Japan and other countries, and the concern over nationalist outbursts is real after 1989. Ross (Citation2013) reveals that political instability, internal economic inequality, and the popular pressure to adopt a more nationalistic foreign policy made China more aggressive in its actions. Zhao (Citation2013) argues that China’s leaders may be more willing to pander to nationalism while securing their ‘core interests’.

Analysis of the events surrounding China’s territorial and historical disputes with Japan has revealed a ‘safety valve’ in China’s handling of nationalism: Officials deflect people turning to criticism of the Chinese government by unleashing angry nationalism and allowing street protests against Japan (Cairns & Carlson, Citation2016; Hassid, Citation2012). Moreover, some research indicates that nationalism is also encouraged by assertive official actions, such as regularised patrols of disputed islands and the delineation of the Air Defense Identification Zone in the East China Sea (Burcu, Citation2022). Weiss (Citation2013, Citation2014) offers a more instrumental framework, arguing that tolerating or encouraging nationalism can be used to send diplomatic signals of determination or cooperative intention. Some scholars argue that the willingness of states to cater to nationalism is conditioned by the nature of the events in dispute, and officials may be more inclined to respond to nationalism if sovereignty or perception of sovereignty is at stake (Cotillon, Citation2017; Peng, Citation2022). The emphasis from Weiss and Wallace (Citation2021) on centrality and heterogeneity also suggests that sovereignty is a highly central issue.

By examining various cases of international incidents involving China, existing literature can sketch a picture of why China sometimes embraces nationalism, but not an analytical framework with continuity that examines China’s responses. Existing research on the safety valve also needs more nuanced analyses. Second, some well-established analytical paths have a post hoc illustration. For example, the Chinese government can indeed send diplomatic signals externally by treating nationalism differently. However, it would be too challenging for researchers to know what signals the Chinese government intends to send before China makes its policy choice. Thus, they could hardly fully explain China’s international behaviours. Furthermore, nationalism may have caused a significant impact on the Chinese government before it could consider what diplomatic signal to release. The following analytical framework seeks to ease the abovementioned literature gaps.

A framework of China’s foreign policymaking on nationalism

The construction of the analytical framework starts with analysing domestic legitimacy, a crucial concern for the CPC and the Chinese government (Lian & Li, Citation2023). After the end of the Mao era, the CPC’s ideological legitimacy experienced challenges (Zhao, Citation2013, p. 544). Therefore, the CPC relies on performance legitimacy that is dominantly based on economic growth, so economic legitimacy is critical for the CPC in the post-Mao era. Foreign policies in international incidents will affect the economic relationship with other states, and international trade and cooperation are significant for China’s economic growth. Therefore, decision-makers must assess the value of a diplomatic relationship when dealing with international incidents. A look at Chinese diplomacy in the post-Mao period reveals a tendency to avoid harming stable international economic cooperation (Duan, Citation2017; Shen, Citation2004). It was a pragmatic style of diplomacy based on recognising the importance of foreign investment, advanced technology, economic relations, and management experience with the West (Reardon, Citation2002, pp. 36–40), originating in the Deng period. This tradition was inherited by the following leaders, who expressed their hope to pursue a stable economic partnership with the West, especially with the US. Of course, economic value is not the only indicator of the importance of a diplomatic relationship. For example, although Russia’s economic value to China is not crucial, Sino-Russian relations have more significant political and strategic connotations. However, considering that the CPC has listed economic development as the dominating priority for the party and state, economic legitimacy is indeed critical as well as a measurable indicator when examining China’s assessment of the value of one diplomatic relationship.

Meanwhile, economic growth is not the only source of legitimacy. Weiss and Wallace (Citation2021, p. 645) identify three sources of legitimacy in China today: economic growth, nationalism, and public security. While providing public security was not a long-term challenge for the Chinese government, nationalism offers the other primary source of the CPC’s domestic legitimacy. China has institutionalised the narrative of nationalism into the everyday life of the Chinese to reinforce its nationalist legitimacy (Wang, Citation2008; Zhao, Citation1998). As analysed before, top-down nationalism and bottom-up nationalism are interrelated in China. Under many situations, Chinese officialdom has been willing to be in tune with nationalist anger, and economic legitimacy can give way to nationalism (Neo & Xiang, Citation2022). For example, the Chinese government and official media frequently supported public dissatisfaction against foreign brands perceived to ‘insult China’. However, because the top-down narrative portrays the government as a staunch defender of national interests, bottom-up nationalism may be more sensitive to the state’s retreat in international incidents, and the costs of ignoring nationalism can be higher than that in Western democracies, implying that retreat and weakness sometimes are even more dangerous (Gustafsson, Citation2014; Li & Chen, Citation2021).

Nationalist legitimacy and economic legitimacy are sometimes contradictory, and the Chinese government must balance the two when making policy choices in international incidents. It is difficult to imagine China altogether abandoning nationalist legitimacy for economic legitimacy or vice-versa. China’s economic growth has slowed in recent years, and there are many hidden dangers, like government debt and real estate foam. This change makes nationalist legitimacy more critical nowadays, which explains China’s willingness to accept some minor economic sacrifice for nationalist legitimacy. However, embracing nationalism in international affairs may lead to a breakdown in relations with the other country, resulting in economic repercussions. When the costs of mobilising nationalism are high, the Chinese people are also concerned that their living conditions will stop improving (Duan, Citation2017). Therefore, it is also difficult to see China fully embracing nationalist legitimacy without caring for economic growth.

Measuring risks for the regime

Which type of legitimacy concerns the Chinese government most? This depends on to what extent the effects of one international incident may threaten China’s regime security. In other words, the Chinese government will consider the respective risks, costs, and benefits of embracing and repressing nationalism. Damages to both nationalist legitimacy and economic legitimacy may bring a critical risk to the regime’s security and stability. However, for most short-term international incidents that require rapid decision-making, the threats of harming nationalist legitimacy will usually be more prominent than those of reducing economic legitimacy.

There are two main reasons. Firstly, public anger can erupt independently of elite outbursts and become difficult to control (Dafoe, Liu, O’Keefe, & Weiss, Citation2022, p. 4), as seen in the 2012 protest marches against Japan, where nationalist anger had the potential to challenge the government and undermine social stability (Burcu, Citation2022; Pei, Citation2020). Secondly, the scope for redress when nationalist legitimacy is harmed is less flexible than when economic legitimacy is threatened. Ross (Citation2013) provides an example of policymakers turning to nationalism when China met challenges to stimulate jobs and the economy in the 2008 financial crisis. However, if nationalist legitimacy is undermined by the appearance of weakness in international affairs, it is more difficult to appease the population by shifting to economic legitimacy. As Eric Hoffer (Citation1951, pp. 97-98) has argued, when people consider themselves a tight-knit group, individual interests and responsibilities are abandoned. It would be hard to imagine that the state could have convinced the large number of rabid nationalists who attacked Japanese-branded cars and Japanese restaurants to get off the streets in 2012 by giving them promises of economic and employment benefits. Instead, the profitable response would be to escalate China’s official countermeasures and declare a diplomatic victory as soon as possible (Reilly, Citation2014). Therefore, the threat of nationalism to legitimacy may be a more urgent consideration than economic growth in an incident. Moreover, supporting nationalism and behaving more strongly in international incidents may increase the CPC’s domestic image as a solid guardian of China’s national interests.

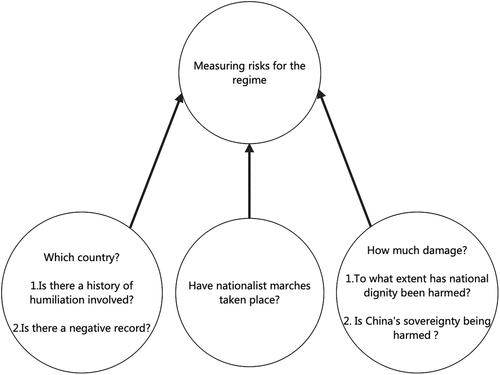

Policymakers could measure the risks of one international incident to regime security through three main elements (). These are (1) Who are the countries involved in the international incident? (2) How much damage was done to China due to the incident? (3) Have mass nationalist marches already taken place? An international incident must meet at least two points to threaten the regime’s security.

On the first point, the CPC repeatedly claims its long-standing struggles against foreign aggression and imperialism as one source of its legitimacy. Therefore, the Chinese people are educated to note who is ‘on the other side’ of history, and Chinese nationalist identity is shaped by China’s dynamic relationship with other nations and the past, including its semi-colonial historical memories (Gries, Citation2004, p. 19). The US and Japan provide the main focus of Chinese internet nationalism (Breslin & Shen, Citation2010). For example, Japan is a long-standing target of Chinese nationalism and can easily be ignited by ‘provocative’ acts, particularly near the sensitive anniversary of national humiliation (Callahan, Citation2006; Wang, Citation2008). Furthermore, a country’s negative record of international incidents with China is an influencing factor. Those countries regularly conflict with China are more likely to face a stronger Chinese nationalist reaction. For example, comments on Weibo (known as China’s Twitter) demonstrate that China’s restraint towards countries with a history of contention may lead to more significant popular discontent (Weatherley & Zhang, Citation2017, p.108). In addition, apparent weakness (or perception of weakness) of Chinese foreign policy in a previous dispute may also reduce nationalist tolerance in a current incident.

On the second point, China may have suffered in an international incident regarding intangible national dignity and tangible sovereignty. Decision-makers would measure the severity of the international incident by emotion criteria such as the extent of damage to national dignity or prestige. This relates to what Peter Gries writes about ‘saving face’ that involves efforts to preserve ‘ingroup positivity’ or ‘collective self-esteem’ and the honour of the nation (Gries, Citation2004, p. 22). Meanwhile, as international incidents involving sovereignty often challenges legitimacy, they are equally integrated into measuring the risks. For example, the sovereignty of Taiwan, Tibet, Xinjiang, and Hong Kong are issues of ‘high centrality’ since they would affect regime survival (Weiss & Wallace, Citation2021, p. 656).

On the third point, whether nationalist protests have already taken place is crucial when assessing the risks for the regime. It is far more costly to stop a nationalist protest that has already begun than to prevent it in advance (Weiss, Citation2013, p. 5). Moreover, the development of technology may have hindered China’s ability to do so. For example, blogs, online commentary, and other digital platforms may convey information beyond the official agenda (Hassid, Citation2012). Even if the government censored relevant information, it could significantly damage nationalist legitimacy and create additional risks. Thus, given the dramatic nature of an incident and the speed of information transmission, nationalist actions may spread before decision-makers take action (Dafoe et al., Citation2022, p. 4).

Opening and closing the ‘safety valve’

Nationalist anger is often transformed into resentment and criticism of the government (Cairns & Carlson, Citation2016, p. 40). When such anger is overwhelming, this resentment can be exacerbated by the government’s rejection of nationalist activities (Hassid, Citation2012). Therefore, when policymakers perceive such risks, they will need to open a safety valve through which nationalist anger can be released (Reilly, Citation2011). This is a pragmatic tool for managing nationalism. Opening the safety valve allows nationalists to ‘blow off steam’ and release their anger and discontent before it can do more damage to nationalist legitimacy and social stability (Cairns & Carlson, Citation2016). In addition, the outbreak of nationalist sentiments can be sudden, and government elites will not have time to react to and manage public opinion before people rush to the streets. Therefore, the safety valve may be forced open since the policymakers have little choice but to tolerate nationalist demonstrations. In this research, ‘opening/activating the safety valve’ means that the Chinese government supports nationalism and even allows criticism against itself to release domestic political pressure. The government will also monitor nationalism to ensure it will not turn into an anti-government movement and cause significant social instability. To defend national interests and appease public anger, it usually also embraces nationalism through appropriate escalations by seeking a balance that would appease nationalism as much as possible while avoiding a long-term deterioration of diplomatic relations with the other side. When necessary, it will select one as the priority to guarantee the regime security when the two significantly conflict with each other.

Even when faced with the angriest nationalism, the Chinese government will usually end it eventually after the initial permission of open expression of anger (Burcu, Citation2022, p. 259). This is the closure of the safety valve, which means ending strong support for nationalist sentiments, like anti-foreign parades or widespread official media coverage of the incident. Also, the government will stop permitting harsh criticism of the government. A fast closure of the safety valve would quickly gain diplomatic flexibility and reduce the damage to economic relations, but at the same time, nationalist anger may be far from over (Weiss, Citation2014), particularly without a victory. In comparison, keeping the safety valve open and using harsh escalation may ensure nationalist legitimacy (Dafoe et al., Citation2022), but there will be inevitable economic and diplomatic losses. Moreover, decision-makers will also consider the potential domestic risks of keeping opening the safety valve, including regime instability, decreasing leadership support rate, and social unrest.

External escalating measures aimed at defending national interests and satisfying public opinion will not necessarily end together with the safety valve’s closure, as the latter sometimes comes earlier when handling incidents. Except for some permanent measures, several developments may bring China’s escalation to an end: the other country retreats; an agreement is achieved; nationalism sentiments gradually fade; the economic value of the diplomatic relations rises; the Chinese government thinks there is no need to maintain the escalation measures. As the Chinese people often view diplomacy as a competition between leaders of nations to win or lose face (Wang, Citation2012, p. 190), the government can declare a victory under the first two circumstances to demonstrate that the government and its leaders are not weak. Apart from these two situations, the government’s consideration of legitimacy is still significant in explaining the time to end the external escalation ().

Table 1. Consider the escalation’s level and ending time.

Embrace it or repress it?

The above discussion on legitimacy completes the necessary groundwork for analysing the different policies adopted by China towards nationalism. Decision-makers first consider whether nationalism threatens the regime’s security. Once it is deemed a threat, China will open the safety valve and embrace nationalism. When policymakers do not perceive a significant loss of nationalist legitimacy, or when the loss is within acceptable limits, the safety valve will not be activated, and the government will consider the value of economic relations with the other state and the loss from challenging such relations. Potential indicators for measuring the value of economic relations include whether the GDP of the other country is close to or surpassing that of China and the significance of bilateral investment and trade for China. The Chinese government will repress nationalist sentiments if it recognises that economic ties with the other side are highly valued and that challenging these ties would lead to significant losses in its economic legitimacy. In comparison, when relations with the other side are seen to have relatively low value, China will have the flexibility to take the next step in considering whether the incident harms elements of China’s core interests.

China’s core interests have remained ambiguous (Zeng, Xiao, & Breslin, Citation2015, p. 247), posing challenges for academia and policy circles. However, core interests still serve as a critical factor for China’s policymakers to consider during international incidents. The Chinese government identifies the elements of China’s core interests as ‘state sovereignty, national security, territorial integrity and national reunification, China’s political system established by the Constitution and overall social stability, and the basic safeguards for ensuring sustainable economic and social development’ (State Council Information Office (SCIO), 2011). This official description of China’s core interests offers significant clues for researchers. With China’s power growing significantly in the past decades, the Chinese government has been expanding the boundary of its core interests and becoming more confident in defending them. Therefore, China is highly likely to consider embracing nationalism when it claims one issue is closely relevant to core interests or certain elements of its defined core interests are harmed.

When core interests are not harmed, there is little reason for China to echo nationalism unnecessarily, as mobilising nationalism could harm China’s overall diplomatic relations and bring domestic criticism against the government. Therefore, China is willing to seek an acceptable compromise for benefits in other issues. For example, Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping claimed several times that the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands issue should be shelved when meeting with Japanese leaders and officials, as China did not regard it as a core interest then. Similarly, China has also emphasised the ‘joint development’ of the disputed marine resources in recent decades. This, of course, does not mean that China is indifferent to maritime rights. Instead, China hopes to set aside territorial disputes and increase international cooperation in the sense that ‘sovereignty belongs to China, shelf differences, and seek joint development’ to maintain a delicate trade-off between rights protection and stability maintenance (Peng, Citation2022, p. 18).

When core interests are at stake, this research proposes that whether an agreement can be achieved is a key factor when explaining China’s different policy choices. Such agreement also includes tacit or oral consensus between China and the other country. When an agreement that China supports is reached, China has no significant motivation to encourage nationalism to ruin its efforts and harm its international reputation and diplomatic relationship. A convincing example is its land-boundary disputes. China has peacefully resolved its terrestrial disputes by signing boundary agreements with 12 neighbours, leaving only the disputes with India and Bhutan unsettled (SCIO, Citation2011). Half of the agreements were signed since the 1990s, and the Chinese government successfully cooled down nationalist sentiments opposing concessions. Therefore, China would not be ironclad on many critical issues if a fair agreement could be achieved.

On the other hand, when an agreement to set aside disputes cannot be reached, the Chinese government will often choose to embrace nationalism and escalate the situation, as elements of core interests are damaged. As shows, when the decision has reached this step in the framework, it is clear that the issue does not challenge regime security and economic legitimacy. Moreover, the Chinese government will benefit from embracing nationalism by demonstrating a domestic image of a defender of national dignity and interests. Under this situation, it will usually have solid control over the development of nationalist sentiments and avoid the potential backfire against itself.

Case studies: testing consistency

This section selects five cases to test the explanative power of the analytical framework. The United States and Japan are arguably the countries with which China has had the most numerous and dangerous international incidents. The South China Sea disputes caught global attention due to the complexity and escalation in the past decades. The Huawei/Meng Wanzhou case is a non-sovereignty issue and reflects the influence of President Xi Jinping’s personality on diplomatic issues, which is critical in understanding Chinese diplomacy in recent years. These cases could offer crucial evidence to test the validity of this framework when explaining China’s policies towards nationalism in international incidents.

The 1999 bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade

The bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade late at night on 7 May 1999 is a representative example of an international incident with an upsurge of nationalism. Bombers dropped guided bombs on the Chinese Embassy in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia during a NATO air strike, killing three Chinese and injuring 27 others (Wu, Citation2006). After the news reached China, marches broke out in over 100 cities. In Beijing, tens of thousands of people gathered around and attacked the US embassy, which was damaged despite the police’s on-site control; in Chengdu City, protesters even set ablaze at the U.S. consul’s residence (CNN, Citation1999; Weiss, Citation2013, p. 17). Chinese officials also released strong criticism and protests about the incident. On the evening of 9 May, Vice-President Hu Jintao launched a televised speech, strongly condemning the bombing and expressing the government’s support for patriotic demonstrations that ‘comply with the law’ (CCTV, Citation1999).

China recognised from the outset that the wave of nationalism could be highly threatening to the regime. First, the US had many negative precedents for the Chinese in international incidents at that time, such as the interception of the Chinese ‘Yinhe’ cargo ship in 1993 and the highly influential 1995–1996 Taiwan Strait crisis, which touched on China’s core sovereignty (He, Citation2016). Some Chinese perceived this bombing as an action by an evil America against China (Gries, Citation2001, pp. 38–41). Second, as Gries (Citation2004, p. 19) observes, ‘Chinese reactions to the 1999 Belgrade bombing were shaped in part by memories of China’s semicolonial past’. The incident resulted in such severe insult to dignity that the government had no time to make decisions about nationalist protests (Dafoe et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, President Jiang Zemin regarded this attack as a severe act of aggression against China’s sovereignty (Wong & Zheng, Citation2001, p. 337). Third, Dingxin Zhao (Citation2017, p. 245) obtained valuable details in an interview with a senior university official at the time, who said that unauthorised large-character posters with anti-American slogans were already all over Beijing’s universities when official news had just reached the country. The Chinese government was well aware of the costs and difficulties of suppressing mass nationalism. It was dangerous to ban demonstrations altogether, as people may have turned their anger against the government (Zhao, Citation2017, pp. 241–246). Against this background, not allowing the students to vent their anger and failure to respond to the bombing with tough diplomacy were likely to be labelled as unpatriotic (Wong & Zheng, Citation2001, p. 337). Therefore, after sensing a threat to the regime, the government saw fit to open the safety valve, unleash nationalist anger, and escalate against the US.

Against this background, China acquiesced to the protest marches and even transported students to the US Embassy (Zhao, Citation2017, p. 247). China also increased its diplomatic pressure as an escalation measure to appease nationalism. Chinese Foreign Minister Tang Jiaxuan wrote in his memoirs that he summoned the US Ambassador to China, James Sasser, on 10 May and made four demands: (1) apologise to the Chinese government, the people and the families of the victims; (2) investigate the incident thoroughly; (3) publish the results promptly; (4) severely punish those responsible (Tang, Citation2009, p. 177). At the same time, China announced the suspension of bilateral exchanges with the US, including high-level talks on human rights, non-proliferation, arms control, and international security. To demonstrate China’s anger and resolve, President Jiang Zemin also declined President Clinton’s requests for a hotline call.

Nonetheless, Chinese policymakers knew China’s tremendous economic growth after the reforms benefited from its close ties with the US (Shambaugh, Citation2001). Therefore, China’s embracing of nationalism remained relatively restrained. For example, Weatherley and Zhang (Citation2017, p. 50) assessed China’s official response as merely a fierce protest and not a reality, and Kai He (Citation2016, p. 75) also described China’s actions as a form of ‘limited diplomatic coercion’. Diplomatically, China did not respond to extreme nationalist demands, including sending the People’s Liberation Army to Yugoslavia to take part in the fighting or taking the US to the International Court of Justice in The Hague (Shen, Citation2004). China neither recalled its ambassador nor terminated its economic cooperation with the US, restarting its negotiations on China’s accession to the WTO (Wu, Citation2006, p. 362). Chinese officials also lowered their voices of criticising the US after Clinton formally announced his apology, and by 11 May, demonstrations near the embassy were over (Shen, Citation2004).

Domestically, Zhao (Citation2017, p. 245) found that the government was concerned that excessive use of violence by protesters would affect China’s foreign relations and economic development, and officially organised marches were more peaceful than spontaneous ones. Meanwhile, the control of protests was also gradually increasing, with one student had participated saying that it was significantly more difficult to throw stones at the US Embassy the next day (Shen, Citation2004, p. 126). On the third day, the scale of the protests shrunk, and Ambassador Sasser at the US embassy said, ‘We may go to bed early and get a good night’s sleep’ (Weiss, Citation2014, p. 48). Therefore, China gradually closed the safety valve after the US announced their regret, apology, and compensation to China and the family of the casualties. The Chinese government protected its dignity by gaining moral high ground through such a resolution (Wang, Citation2012, p. 190).

The 2001 aircraft collision incident (Hainan Island incident)

On 1 April 2001, a US EP-3 reconnaissance plane collided with a Chinese fighter in the South China Sea, resulting in the death of the Chinese pilot Wang Wei, while the American plane made an emergency landing at Lingshui on China’s Hainan Island. The 24 crew members of the US plane were detained after landing. On 2 and 3 April, President Bush issued two statements calling for the immediate release of all crew members and warning that the incident could affect the fruitful relationship that had just been established between the two countries (Keefe, Citation2002). Chinese officials responded firmly that the collision was caused by the US plane illegally intruding into Chinese airspace and operating incorrectly and demanded an apology from the US. China also asked the US to compensate for the American pilots’ accommodation in China and the cost of the aircraft’s downtime. Lastly, China demanded that the aircraft not be flown back but dismantled and shipped back from China.

Apart from these demands, China did not open the safety valve this time. Why was the upswelling of nationalism in this incident, unlike the incident in 1999, not identified as a severe threat to the regime’s security? Indeed, both incidents are aimed at the same target state, the US, with a negative record of international incidents. The first reason for the difference is that the harm of this incident to China was not as severe as in 1999 (He, Citation2016, p. 83). Furthermore, China had 24 de facto ‘hostages’ in possession and an aircraft of great value. Therefore, China has taken a certain initiative in dealing with the US, which could satisfy nationalists by saving dignity. Secondly, the Chinese government reacted before the outbreak of nationalist protests. Despite forcefully seeking an apology, China repressed extensive domestic media coverage and called on the masses to mourn the pilots rather than take to the streets in protest, even taking control of the organisers preparing for protest marches (Weiss, Citation2013, p. 25). In addition, 2001 was not a period as sensitive as 1999, the tenth anniversary of the 1989 student movements. Therefore, the 2001 incident did not pose a challenge to the regime.

Clearly, when it came to identifying the next element of the framework, the economic value of the relationship, it was clear that relations with the US were rated as having high value. This was not only because President Jiang adopted a pragmatic style of diplomacy but also because he did not want to undermine the progress made in relations with the Bush administration. According to the writings of veteran Chinese diplomat Wu Jianmin, the incident occurred against the backdrop of a period of adjustment in the then-new US Bush administration’s policy towards China, and during his visit to the US in March, Vice Premier Qian Qichen also had reached some consensus with the US concerning the situation on the Korean peninsula and the Taiwan issue. Against this backdrop, prospects for US-China relations were good (Wu, Citation2007, p. 324). Based on this judgement, policymakers chose to ensure stable relations with the US by repressing nationalism. Therefore, China did not escalate this incident as required by domestic nationalists.

The core of the Sino-American contention was the apology issue. To resolve the crisis and bring back its crew detained in China, the US made concessions on 11 April, delivering a message from President Bush for being ‘very sorry’, which was translated into ‘深表歉意’ in Chinese, meaning deep apology or regret (Wang, Citation2012, pp. 178–179). This concession was crucial to China, and China decided to release the 24 crew on the same day. On 3 July, the EP-3 aeroplane was finally disassembled and sent back to the US. This reconnaissance plane could have flown away from China after repair, but its dismantling greatly saved China’s face and dignity. As for the compensation, the two countries did not reach an agreement, but this did not affect this incident’s peaceful resolution as China’s primary demands were met.

‘Nationalisation’ of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in 2012

Japan is probably more often considered by the Chinese as an ‘evil other’ than the United States (Kim, Kim, & Kim, Citation2016, p. 141). This is because of not only the CPC’s repeated reminders of history in the lives of the Chinese people but also the image of the Japanese ‘devil’ (鬼子) in the stories of Chinese elders after tea (Gries, Citation2004, p. 10; Wang, Citation2008). Friction between China and Japan over historical issues and sovereignty has not ceased, and aversion to each other has been perpetuated, reaching a historic peak in 2012. It is valuable to test the framework when examining the 2012 Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands incident between China and Japan.

In April 2012, the right-wing Japanese politician Shintaro Ishihara, then governor of Tokyo, announced his plan to use public funds to purchase three disputed islands from ‘private sellers’. Although, at the time, a Japanese government spokesman said he was unaware of the plan and declined further comments, China saw it as a provocative act that did not ease previous tense confrontations. In response to this provocation, anti-Japanese marches broke out in more than 30 Chinese cities, most of which took place peacefully. Nevertheless, in August, the US and Japan launched joint military exercises near the Islands, which China saw as an even greater provocation (Weatherley & Zhang, Citation2017, p. 100). In September, despite earlier denials, the Japanese government officially ‘nationalised’ the three disputed islands, bringing Chinese patriotic sentiments to a peak, and anti-Japanese marches erupted in 180 cities across the country, with some turning into widespread violence on 18 September. The violence included attacks on drivers and their Japanese cars, vandalism of Japanese restaurants, and even attempts to occupy Japanese department stores (Duan, Citation2017).

Chinese leaders responded positively to nationalist outrage in this incident and expressed a tough stance toward Japan. ‘The Diaoyu Islands are Chinese territory, and the Chinese government and people will never back down’, said then-Premier Wen Jiabao at an event at China Foreign Affairs University in Beijing (Xinhua, Citation2012). An official statement from the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) said that the ‘nationalisation’ of the islands was wrong and unacceptable, and Japan should return to the negotiating table. Otherwise, Japan would be responsible for the consequence. In August 2012, a group of private ‘Defending Diaoyu Islands’ (保钓) groups were permitted to travel to the islands and plant the Chinese flag. This was even broadcast live on the official Chinese media, which was rare considering China used to block these actions in the past (Weiss, Citation2014, pp. 199–201). This incident was the most prominent and prolonged anti-Japanese protest since the normalisation of Sino-Japanese relations in 1972 and saw an unprecedented escalation by China, militarily, diplomatically, and even economically (He, Citation2016, pp. 128–131).

Policymakers recognised the possibility of nationalist sentiment as an existential threat to the regime soon after the events began. Researchers may compare this incident with the 1996 lighthouse incident that also involved the sovereignty of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, and China chose to repress nationalism in 1996. Several developments pushed the Chinese government to open the safety valve in 2012. First, the relationship between Japan and China was no longer like that during the 1996 lighthouse incident. In 1996, despite Chinese nationalist dissatisfaction with Japan’s handling of the Yasukuni Shrine issue, Japan did not have a severe negative record on the principle of ‘setting aside the Diaoyu Islands dispute’ that was established at the time of the establishment of diplomatic relations (Reilly, Citation2014). Second, as Todd Hall reveals, after 2010, the islands’ significance and salience have increased ‘as a symbol, as a domestic political football, and as an object of ongoing, competitive jockeying’ (Hall, Citation2019, p. 12). Third, relations with Japan in 2012 were less valuable and important to China than at the time of the 1996 lighthouse incident. Fourth, compared with the Japanese right-wing forces’ construction of the lighthouse in 1996, the Japanese government’s official ‘nationalisation’ of the three islands sounded more humiliating for China’s dignity. Japan’s completion of the ‘nationalisation’, just one day after the top Chinese leader Hu Jintao had warned against it and one week before the anniversary of the 18 September Incident/Mukden Incident in 1931, was seen as an intention to insult China. Therefore, with the negative record of the 1996 and 2010 incidents, together with the Yasukuni Shrine issue since the 2000s, Chinese public anger against Japan soared in 2012. Moreover, the indication that protesters were already unhappy with the government could be seen on the street (He, Citation2016, p. 132). All these circumstances gave policymakers the indication that nationalism could crisis the regime security, so the Chinese government activated the safety valve.

The outbreak of this incident has also been widely discussed on the internet, including calls for offline rallies and more extreme statements. In the run-up to the events and at the height of anti-Japanese sentiment, China’s censorship was remarkably relaxed to unleash nationalist anger, not only allowing a large number of anti-Japanese and even extreme statements but also criticism of the government (Cairns & Carlson, Citation2016). As Moore (Citation2014, p. 231) observed, most of the abovementioned substantial anti-Japanese marches in 2012 would not have happened without official support, and most were done under government supervision. However, as the number of violent incidents rose during the protests, large-scale anti-Japanese marches were later controlled and called off by the public security authorities (Reilly, Citation2014, p. 221).

On the diplomatic front, China cancelled various celebrations for the 40th anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and Japan and suspended high-level contacts (Jie, Citation2023, p. 200). Moreover, once the Japanese government purchased the disputed islands in September, China sent maritime law enforcement ships to patrol within the 12 nautical miles of disputed islands, averaging 17 ships a month from September 2012 to September 2013 (Jie, Citation2023, p. 202). Apart from the repeatedly appearing official Chinese aircraft above the islands’ airspace, China declared the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone on 23 November 2013 (Hall, Citation2019, p. 13). Economically, travel agents were asked to postpone and cancel tours to Japan. Twenty-three thousand tickets to Japan were cancelled in the three months following the incident (He, Citation2016, p. 130). In addition, Japanese car brands, including Toyota, Honda, and others, lost $250 million in one month of the crisis (Qi, Citation2012).

After choosing to open the safety valve, policymakers need to balance nationalist anger and economic costs to decide the escalation’s level and ending time. It was clear that China’s escalation measures were more punitive and long-lasting than those taken during opening the safety valve in the 1999 embassy bombing incident. As analysed before, Chinese leaders did not want the 1999 incident to ruin the Sino-American cooperation, as a positive relationship with the US was significant for China’s economy. In comparison, China’s GDP surpassed that of Japan in 2010. Against this background, China gradually stopped treating Japan as a major power in the world (Global Times, Citation2015). For the Chinese government, the need to appease nationalism and protect nationalist legitimacy prevailed over the need to consider the economic value of relations with Japan. Meanwhile, patrolling regularly surrounding the islands increased China’s leverage on the issue. Therefore, China had no intention of ending some punitive measures very soon. The Chinese MFA did not announce the resumption of high-level consultations on maritime affairs between China and Japan until September 2014. Moreover, China’s patrols surrounding the islands have become routine after the 2012 incident.

South China Sea arbitration

Although the Chinese foreign policy also embraced nationalism in the South China Sea (SCS) arbitration incident, this case differed from the 2012 Diaoyu/Senkaku incident, where the safety valve was opened. The SCS arbitration had a close link with the standoff between China and the Philippines over the Huangyan Island/Scarborough Shoal in 2012. In that incident, China claimed that a Philippine naval gunboat was harassing fishermen who were fishing legally, while the Philippines claimed that the Chinese maritime law enforcement agencies had organised a fleet of fishing boats into the waters of Island/Shoal and stopped the entry of Philippine vessels (Buszynski, Citation2018; Peng, Citation2022). This incident resulted in a Chinese victory by firmly controlling the Island/Shoal. Ultimately the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs announced that it had exhausted ‘almost all political and diplomatic avenues for a peaceful negotiated settlement of its maritime dispute with China’ (Buszynski, Citation2018, p. 125). This confrontation led to the subsequent SCS arbitration initiated by the Philippine Government of Benigno Aquino III. China had announced its rejection of the verdict and consistently called for a bilateral diplomatic solution rather than resorting to a third-party platform, which it claimed was not conducive to resolving this dispute.

The arbitration concluded on 12 July 2016, ruling favouring the Philippines and rejecting many of China’s claims. However, this incident did not challenge China’s regime security. The Philippines was not a traditional target of Chinese nationalism. The 2012 standoff at the Huangyan Island/Scarborough Shoal increased the Chinese people’s dissatisfaction with the Philippines, but China’s solid control over the Island/Shoal increased the Chinese people’s support for the government. In addition, the SCS does not contain a humiliating narrative like the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, and Chinese people were more concerned about the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands than the SCS (Chubb, Citation2014, pp. 9–10). Furthermore, China has a superior sentiment toward the multiple countries involved in the SCS (Cotillon, Citation2017, p. 66), because of its ancient and present status as a more powerful state. In the wake of the arbitration case, there was widespread online dissatisfaction towards the Philippines, the US, and Japan. Nevertheless, no protests broke out in China concerning this issue.

There was, therefore, no strong reason for China to activate the safety valve; instead, it turned to an evaluation of the economic value of its relationship with the other side. China did not rely on its relationship with the Philippines for economic and technological access. The Philippines was of no critical economic value to China, which could be seen in China’s sanctions tactics. During the incident in 2012, China detained Philippine bananas on the grounds of quarantine issues, which later spread to several other Philippine-produced tropical fruits. In July 2012, China also announced the establishment of the Sansha City to consolidate its control over the SCS.

Policymakers will then turn to the next step to gauge the harm to China’s core interests. China had stressed the arbitration as an issue of sovereignty, and the CPC had less room for manoeuvre than in the 2014 HYSY-981 Oil Rig incident (Peng, Citation2022). The arbitration’s rejections of China’s claims included the nine-dash line surrounding the SCS and China’s claims of historical rights in this region. Furthermore, the award by the arbitral tribunal stated that the maritime features occupied by China in the Nansha/Spratly Islands could not generate the 200 nautical miles exclusive economic zone, and some of China’s activities in the SCS had violated the rights of the Philippines (Permanent Court of Arbitration, Citation2016). These arbitration results have challenged China’s core positions on the SCS issue. Whether the SCS issue is part of China’s core interests has been debated. However, this incident offered further evidence that China’s core interests have been expanding. On 18 July 2016, the commander of the People’s Liberation Army Navy, Admiral Wu Shengli, explicitly told the US Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral John Richardson, that the SCS was China’s core interest and concerned the foundation of the CPC’s governance, the country’s security and stability, and the Chinese nation’s basic interests (Xinhua, Citation2016). Wu’s words indicated Beijing’s resolve on this issue, and this was the first time that the statement concerning the SCS as a core interest had been made very openly and clearly and reported widely in the Chinese media (GovInfo, Citation2016, p. 3).

When it went to the international tribunal, the Philippines’ actions turned a bilateral matter into a multilateral issue under the international community’s spotlight. The relationship between Beijing and the Philippine Government of Benigno Aquino III had broken down, eliminating the hope for a bilateral agreement to set aside this issue. Therefore, the Chinese government chose to embrace nationalism to defend its national interests and increase its nationalist legitimacy before and after the announcement of the arbitration results. Chinese official media have intensively published critical news and comments, claiming this arbitration violated international law and China’s rights. Externally, Chinese diplomats refuted the award as illegal and invalid. Furthermore, China has conducted military exercises around the disputed islands before and after the arbitration results were announced (Buszynski, Citation2018, p. 134), although China claimed that these exercises had no direct link with the arbitration.

It was remarkable that China’s escalation against the Philippines was short and moderate compared with the Huangyan Island/Scarborough Shoal and Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands incidents in 2012. The primary reason for this difference was that the Chinese government hoped to achieve a consensus to set aside this issue with the Philippine government under the new President Rodrigo Duterte. President Duterte had delivered a series of friendly signals to China before and after his inauguration on 30 June 2016: he publicly expressed a willingness to ‘explore joint development agreements with China’ during the presidential campaign and continued to emphasise the importance of economic cooperation with China; he claimed that he had no intention to ‘taunt’ Beijing or ‘flaunt’ the arbitration ruling just days before the decision was released; he also announced that he would designate former president Fidel V. Ramos as special envoy to break the diplomatic stalemate with China (Hsu, Citation2018, pp. 17–21).

The visit of Ramos in August 2016 pushed the improvement of the China-Philippine relationship and paved the way for President Duterte’s state visit with high courtesy to China in October. China finally lifted its restrictions on importing Philippine fruits since 2012 before Duterte’s arrival. Philippine Foreign Minister Perfecto Yasay declared that dialogue with China based on the ruling ‘may not happen in our lifetime’, and the ruling would be placed on the ‘backburner’ (Buszynski, Citation2018, p. 137). Through this visit, China has achieved an agreement with the Philippines to set aside their disputes and the arbitration award. Therefore, China cancelled its unilateral sanction measures. Soon after Duterte’s visit, Filipino fishermen got permission from China Coast Guard to fish in the disputed waters near the Huangyan Island/Scarborough Shoal. During Duterte’s tenure, China provided the Philippines with various assistance, including infrastructure development, loans, and other assistance. The topic of SCS also cooled down, and China has refrained from taking assertive escalation actions against the Philippines. This shift from embracing nationalism to repressing nationalism demonstrates that whether an agreement can be reached is essential to explain China’s policy choice.

The Huawei/Meng Wanzhou incident

With a large number of patented 5 G technologies, Huawei is one of the world’s most influential technology companies. Before the US banned selling chips to Huawei, this company also had one of the largest smartphone sales in the world. Its leading technology and market share in telecommunication have been a crucial part of China’s expanding influence. Despite being a private company, the US believes that Huawei has close ties to the Chinese government due to founder Ren Zhengfei’s military experience and China’s domestic regulations. Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s CFO and the daughter of Ren Zhengfei, was arrested by Canadian authorities in Vancouver on 1 December 2018 on a warrant issued by a New York court for Huawei’s alleged violation of US laws and policies banning trade with Iran and cheating the HSBC Bank, and the US wanted Canada to extradite her to the US. This long-lasting incident significantly impacted China’s relations with Canada and the US, and it could test the framework regarding China’s foreign policies towards these two countries in this incident.

Meng’s arrest immediately sparked a significant reaction in China. President Xi and President Trump were meeting in Argentina on 1 December 2018, the same day as Meng’s arrest. At that time, the US-China relations were already severely damaged due to an ongoing trade war. Additionally, Huawei has been a famous brand in China, and many of its consumers hold patriotic feelings towards this Chinese company. Therefore, the public was acutely aware of Meng’s detention. However, this incident did not involve the sensitive sovereignty issue or historical humiliations. The arrest of Meng was not as intense or humiliating as the other cases mentioned in this article, and Chinese nationalists did not rush to the streets. Furthermore, this incident was regarded as evidence of America’s containment of China, which would increase the public’s support of the Chinese government under the effects of ‘rally around the flag’. Consequently, the Chinese decision-makers have not seen threats to the regime, so there was no need to activate the safety valve.

In this situation, the Chinese government will first evaluate the economic value of the target countries involved in this incident. The first was the US, the initiator of this incident. The US had the world’s highest GDP, and it has been China’s largest trading partner country. Although China was experiencing a trade war against the US then, it still did not change the fact that the US was a country of high economic value for China, and the Chinese government hoped to achieve an agreement with the US to ease their tensions on trade. Therefore, our framework suggests that Chinese foreign policy would not follow nationalist demands to escalate this issue against the US.

China’s policy towards the US verified the framework’s predictions. In theory, the Canadian government’s arrest of Meng was to follow its extradition treaty with the US, so China should have punished the US for this incident to satisfy nationalism and push the US to retreat. Initially, China’s MFA Spokesman Geng Shuang said China had made stern representations to the Canadian and US sides, demanding an explanation for Meng’s arrest and her immediate release. However, Geng also clarified that this incident should not affect the Sino-American negotiations on the trade war (MFA, Citation2018). Meanwhile, China has not taken particular escalation measures against the US other than to continue to express its anger over the matter and its demand for Meng’s immediate release.

In comparison, China’s policy calculation towards Canada took a different approach. With the trade between China and Canada accounting for only 2.43% of China’s total foreign trade in 2018, ranking eleventh among China’s trading partners (General Administration of Customs, Citation2018), Canada was clearly a relatively weaker target compared with the US, and the economic costs of escalation were acceptable for China. Following this indicator, it remained for the Chinese government to continue to identify whether the incident was detrimental to China’s core interests.

The Chinese government has listed national security and sustainable social & economic development as elements of its core interests (SCIO, Citation2011). Since taking office, President Xi Jinping has continuously emphasised that technological innovation is the strategic support for improving social productivity and comprehensive national strength and must be placed at the ‘core’ of the country’s overall development. For example, in his address to top Chinese scientists and engineers in May 2018, half year before Meng’s arrest, he included mobile communication as one of China’s world-leading technological achievements. He also pointed out directly, ‘Only by holding the critical core technology in our own hands can we fundamentally safeguard national economic security, national defence security, and other security’ (Xi, Citation2018). President Xi’s recognition of the achievement and strategic significance of the mobile communication industry explained his determination to save Meng. According to Chinese MFA Spokesperson Hua Chunying, ‘President Xi Jinping gave personal attention’ to this issue, and he raised this issue and ‘asked the US to properly resolve it as soon as possible’ in his phone call with President Biden (MFA, Citation2021).

The escalating rivalry between China and US has further made the Huawei issue closely related to China’s core interests. In August 2018, the Trump administration took action to ban the use of telecommunication equipment from Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE. In May 2019, it added Huawei to its Entity List, blocking the trade between Huawei with US tech companies. Meanwhile, the US has been exerting tremendous pressure on its allies to ban Huawei’s 5 G network equipment (Krolikowski & Hall, Citation2023). Meng’s arrest happened in the middle of these issues. As a result of these stiff sanctions, Huawei, once the world’s second-largest producer of smart mobile devices, became unable to produce mobile 5 G telephones. The US series of sanctions against China’s chip industry offered China further evidence that the US was containing China’s technology development, represented by Huawei’s 5 G and other industries listed in the strategic plan of Made in China 2025. Therefore, the Chinese government regarded Meng’s arrest as a political incident that abused the extradition treaty, and the arrest was a microcosm of the crackdown by the US on China’s development in the science and technology sectors, which are critical to China’s social and economic development.

At this stage, an agreement is important on how China will finally deal with nationalism and whether there will be an escalation. It was clear that China had asked Canada to terminate the extradition and release Meng but had been refused. Therefore, China quickly embraced nationalism and escalated against Canada. On 10 December 2018, two Canadian citizens, Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig, were arrested in China for endangering national security and conducting espionage activities. This action was considered a form of ‘hostage diplomacy’ by the Canadian side, despite China’s claim that it was in line with judicial procedures and had no connection with Meng’s arrest. Apart from the ‘Two Michaels’, China sentenced Canadian citizen Robert Lloyd Schellenberg to death for his crimes of smuggling drugs in China. China also refused to arrange a meeting between President Xi and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Moreover, China also issued economic punishment threats against Canada. At a press conference in January 2019, then-Chinese ambassador Lu Shaye contended that the ongoing negotiation concerning China-Canada free trade agreement would undoubtedly be affected, and Canada should take responsibility for the incident’s significant damage to their bilateral trade (PRC Embassy in Canada, Citation2019).

The incident has received long-standing nationalist and public attention, and developments in Meng’s arrest have regularly topped Weibo platform searches in the more than 1,000 days since her arrest. China’s quick arrest of two Canadian citizens was seen as a justified retaliation supported by nationalism (Koetse, Citation2018). It was not until Meng’s release that the patriotic pride climaxed with Meng’s high-profile welcome ceremony at Shenzhen Airport. Meng thanked the Chinese government, notably President Xi, for saving her. Her words, ‘If faith had a colour, it would be Chinese red’, once again reached the top of Weibo searches. By achieving this agreement, China declared its diplomatic victory. There was no need to maintain its harsh punitive measures against Canada, so, in a low-key manner, China had allowed the ‘Two Michaels’ to leave China on the same day of Meng’s return. This international incident finally declared an end.

This long-lasting incident involved China’s relations and foreign policies towards the US and Canada, with different economic values for China, and the ending of the incident demonstrated the importance of reaching an agreement in international incidents. More importantly, this case helps researchers understand how leadership personality and policy preference affect policymaking. As analysed before, President Xi Jinping has paid close attention to China’s technological innovation against the background of Sino-American strategic competition. Therefore, the Huawei issue relates more closely to China’s core interests under his influence. Moreover, as he regards China has become a powerful country in the world, the economic value of China’s relationship with some middle powers is not as important as defending China’s national interests and dignity, which could have a critical effect on China’s foreign policy.

Conclusion

Based on the theoretical analyses and empirical case studies, this research believes that China is not helplessly in the grip of nationalist sentiment in international incidents, and nationalism remains pragmatically judged according to a continuum of decision-making patterns. It cannot be said that the Chinese government is immune to nationalism, but it has indeed demonstrated proficiency in dealing with nationalism. Decision makers will first assess whether the international incident threatens the regime’s security, and if so, a safety valve can be opened to allow for the release of nationalist anger and escalate the situation to appease nationalism. If there are few threats to regime security, the next step will be to assess the economic value of a positive diplomatic relation, whether elements of core interests are damaged, and whether China can reach an agreement to set aside or resolve the disputes. This means that when nationalism in international incidents does not threaten regime security, it often plays a secondary role in China’s decision-making process, compared with economic legitimacy and a valid and fair international agreement.

This paper used five cases to test different elements of its analytical framework. Like two sides of one coin, the framework’s falsifiability is its achievement, while future research and developments in Chinese politics and foreign policy may find negative cases that this framework does not explain or predict. However, this paper has contributed to bridging the literature gap concerning the relationship between nationalism and Chinese foreign policy. Further research will need to follow some developments that may require the revision of this framework. First, it may become increasingly difficult for the CPC to govern nationalism and public opinion because the internet and media are diversifying. Moreover, internet nationalism has demonstrated more signs of agenda-setting in China (Breslin & Shen, Citation2010). Second, the Chinese government is likely to be more active in accommodating public sentiments in the future with a slowing down economic growth. Third, as China’s relative power continues to grow, even at a slower speed, consideration of the economic value of its relations with other states may become less important, as demonstrated in China’s escalation measures against Japan, the Philippines, and Canada.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers of The Pacific Review for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions for this paper. We are also grateful for the suggestions from Jinhong Li for this research. Both authors contributed equally to this final paper with authors listed alphabetically. Of course, all mistakes and oversights are our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chenchao Lian

Chenchao Lian is a DPhil (PhD) candidate in International Relations at the University of Oxford. He has research experience in China’s research institutions and think tanks. His research focuses on Chinese politics and foreign policy, territorial & maritime issues, foreign policy analysis, and global governance. He has published in several academic journals and media covering these topics, with his latest research investigating China’s legitimacy-seeking published in Third World Quarterly. Apart from his official email address, he can also be reached at [email protected].

Jianing Wang

Jianing Wang is a postgraduate from the Lau China Institute, part of the School of Global Affairs at King’s College London. His research interests focus on Chinese nationalism, Chinese foreign policy, and East Asian international relations. His master’s thesis research offered a foundation for this paper. He can be reached at [email protected].

References

- Aydin, C., Ballor, G., Conrad, S., Cooper, F., CuUnjieng Aboitiz, N., Drayton, R., … Walker, L. (2022). Rethinking nationalism. The American Historical Review, 127(1), 311–371. doi:10.1093/ahr/rhac133

- Breslin, S., & Shen, S. (2010). Online chinese nationalism. Asia Programme Paper: ASP, 3. Retrieved from https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Asia/0910breslin_shen.pdf

- Burcu, O. (2022). The Chinese government’s management of anti-Japan nationalism during Hu-Wen era. International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, 22(2), 237–266. doi:10.1093/irap/lcab002

- Buszynski, L. (2018). Law and realpolitik: The Arbitral tribunal’s ruling and the South China Sea. In S. Lee, H. E. Lee, & L. Bautista (Eds.), Asian yearbook of international law (Vol. 21, pp. 121–140).Leiden: Brill.

- Cairns, C., & Carlson, A. (2016). Real-world Islands in a Social Media Sea: Nationalism and Censorship on Weibo during the 2012 Diaoyu/Senkaku Crisis. The China Quarterly, 225, 23–49. doi:10.1017/S0305741015001708

- Callahan, W. A. (2006). History, identity, and security: Producing and consuming nationalism in China. Critical Asian Studies, 38(2), 179–208. doi:10.1080/14672710600671087

- CCTV. (1999). 北约袭击我使馆相关报道 [Reports of NATO attacks on the Chinese embassy]. Retrieved from https://sports.cctv.com/specials/kosovo/990509/wjn1.htm.

- Chen, Z. (2005). Nationalism, internationalism and Chinese foreign policy. Journal of Contemporary China, 14(42), 35–53. doi:10.1080/1067056042000300772

- Chubb, A. (2014). Exploring China’s ‘maritime consciousness’: Public opinion on the South and East China Sea disputes. Retrieved from https://perthusasia.edu.au/getattachment/fdba7508-e152-46b8-b770-a0aa34f27559/2014_Exploring_Chinas_Maritime_Consciousness_Final.pdf.