Abstract

China’s influence in the global South has both material and ideational aspects. In the era of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), material aspects include trade in goods, infrastructure-building, and imports of raw materials and energy. Ideational aspects include political influence and attempts to diffuse Chinese norms, some of which differ from those enshrined in the so-called ‘liberal international order’. This paper posits that China’s norm diffusion in the global South is attempted via practice-based normative diplomacy which includes both discursive and non-discursive practices. In theory, Chinese norms are supposed to be co-constituted by partners in a process we call ‘earning recognition’. In practice, the Chinese government expects partner countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America to model their behaviour and discourse on the example set by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) without significant contestation. Our analysis demonstrates that the PRC’s normative diplomacy has achieved a degree of earned recognition and influence, in that actors in the global South have begun to alter their behaviour along the normative lines expected by Beijing rather than those enshrined in the Western-led liberal international order. However, Chinese discursive practices have not met with the same degree of recognition as non-discursive ones, leaving space for counter-initiatives from the Western powers.

Introduction

Since Xi Jinping became president in 2012, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been increasing its influence in the global South within the framework of Xi’s flagship foreign policy, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Investments, loans, aid, and infrastructure have been conduits for political as well as economic influence-building (Cheng & Taylor, Citation2017, p. 71). Chinese-led regional cooperation frameworks such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in Central Asia and the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) have also been significant tools for building influence (Jakóbowski, Citation2018).

However, the Chinese government’s efforts to gain influence did not begin with the introduction of the BRI, the SCO, or FOCAC, which date from 2013, 2001, and 2000 respectively. Influence attempts can be traced to the Maoist era, when China sought to enhance cooperation with African states in particular through the construction of railways, roads, and other infrastructure (Jenkins, Citation2022, p. 117). Further efforts emerged from the ‘going out’ campaign which began under President Jiang Zemin in the late 1990s (Shambaugh, Citation2013, pp. 174–175). Nevertheless, the advent of the BRI in 2013 represents an intensification of Chinese influence-building in the global South, with loans for infrastructure deals taking centre stage.

Infrastructure building can be included among the material aspects of the BRI. However, it is important not to neglect the immaterial or ideational aspects of Chinese activity. Ideational aspects are less immediately visible but are at least as significant as the material ones. China seeks to alter certain aspects of the international order within which cooperation occurs, while retaining and promoting those which already suit it (Murphy, Citation2022, p. 2). The Chinese attempt to affect the landscape of international development can thus be characterised as normative, in that it seeks to change the context of cooperation according to Chinese rather than Western norms (Moore, Citation2022, p. 28). In the process, China challenges the dominance of what has come to be called the ‘liberal international order’ (LIO). Hence, Chinese norm diffusion can be interpreted as an attempt to exert normative power in the global South (Kavalski, Citation2013).

Building on previous research into China’s norm diffusion and normative power (Garlick & Qin, Citation2023; Kavalski, Citation2013; Li, Citation2020), we posit that China uses a form of normative diplomacy to alter the development landscape in the global South in its favour. We characterise normative diplomacy as the use of both material and ideational tools and techniques of traditional diplomacy, economic diplomacy, education, propaganda, and state media to transmit Chinese norms to partner countries. Towns (Citation2012, pp. 184–185) posits that norm diffusion occurs via four processes: coercion, persuasion, education, and mimicry. However, since the Xi administration tries to portray China as a partner of global South countries, it portrays itself as diffusing norms mainly via the second, third and fourth of these processes—persuasion, education and mimicry—rather than coercion. Coercion is kept in reserve for cases where the three more subtle means of norm diffusion have failed, as in the case of economic sanctions used against Lithuania because it opened a “Taiwan Representative Office” in Vilnius (Reynolds & Goodman, Citation2022). At any rate, coercion can be ineffective in cases—such as Lithuania—where Beijing lacks sufficient economic leverage to impose its will due to insufficient trade and investment ties. The lack of leverage in the majority of cases points to the need for softer means of long-term norm diffusion.

Accordingly, it is primarily through education and example-setting that China attempts to earn recognition from partner countries for Chinese norms. Seeking to gain normative power by earning recognition for diffused norms is different from efforts to acquire soft power in that it does not necessarily depend upon cultural or other forms of attraction (Nye, Citation1990). Rather it depends on targeted actors acknowledging and adopting norms because they come to see them as useful and effective, even if they do not necessarily find them especially attractive (Manners, Citation2002). In this way, norms are diffused by a long-term process of socialisation rather than attraction (Kavalski, Citation2010). In contrast to Western actors such as the EU, China’s normative diplomacy occurs through the diffusion of practice-based rather than rules-based norms (Garlick & Qin, Citation2023). Unlike the EU, with its explicit democracy and human rights agendas—often presented as a set of requirements accompanying aid, which thus clearly constitute a form of coercion—China does not directly state that it wants partner countries to absorb and adopt Chinese norms of behaviour. Instead, it presents them as discursive and non-discursive practices to be infused into local actors—especially elite groups—via repeated exposure. Such exposure occurs over an extended period during which the targeted actor is supposed to learn from Chinese models and mimic them.

At the same time, China is careful to depict itself as respectful of local actors’ needs and traditions, leaving some space for negotiation of shared norms. To an extent a process of co-constitution takes place through a process of earned recognition which allows for input and mutual respect between China and other nations (Garlick & Qin, Citation2023). This process of earned recognition includes the adoption of normative practices which emanate from discussions between global South actors. These discussions, as will be demonstrated in due course, have produced some shared phrases—discursive practices—such as ‘South-South cooperation’, ‘mutual benefit’, and ‘support/embrace multilateralism’ which are used by China but which have appeared as a result of long-term dialogue within global South frameworks at the UN. Other phrases, most notably the expressions ‘community of shared destiny/future’, ‘people-to-people exchanges’, and ‘win-win cooperation’, can be identified as uniquely Chinese contributions to the discourse.

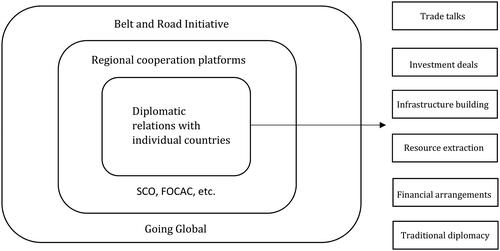

China’s normative diplomacy in the global South takes place within three intersecting frameworks (see ). First, there is the overarching framework of the BRI, built upon the foundations of its ‘going global’ predecessor and the Maoist era, which acts as a loose envelope for specific activities. Second, China uses regional cooperation platforms such as the SCO and FOCAC to try to generate influence through regionalisation. Third, Beijing promotes ties with individual countries through economic diplomacy via trade talks, investment deals, infrastructure building, resource extraction, and financial arrangements such as loans from state-owned banks, as well as more traditional diplomacy aimed at building political ties and influence.

These are the three layers of China’s normative diplomacy: like a Russian doll, the third framework is nested within the second one, which is in turn nested within the first, the BRI. The use of three interlinked layers—akin to a macro-/meso-/micro-structure—is not precisely formulated in official publications, so the degree to which such a structure is intentional on the part of the Chinese government is difficult to ascertain, especially given the lack of information about decision-making processes at the level of China’s leadership. Yet tracing the patterns of Chinese diplomacy in the global South demonstrates beyond reasonable doubt that this is how China builds its relations with countries in developing regions (Garlick, Citation2020, p. 158; Jakóbowski, Citation2018; Kavalski, Citation2009).

China’s normative diplomacy is especially well suited to the global South because of the developing world’s pressing need for economic assistance. Presenting itself as the leader of the global South (or at least a senior partner), China can promote a normative agenda which stands in sharp contrast to that of the West. Unlike some Western countries, China is not encumbered by a colonial past in the eyes of its global South partner countries. This gives its normative discourse about non-interference and respect for sovereignty a relatively high degree of credibility (Jenkins, Citation2022, p. 144) since China’s economic aid constitutes an alternative to that on offer from the West. For instance, loans from Chinese state banks are easier to obtain than International Monetary Fund (IMF) loans because they have fewer strings attached. Chinese financial tools are normatively distinct from their Western counterparts, in that the Chinese do not push for the adoption of norms such as democracy and human rights when accepting loans or investments. However, Chinese aid has different strings attached: non-recognition of Taiwan, support for China in votes in the United Nations, non-support for Tibetan or Uighur independence, and non-interference in China’s internal affairs (Raess, Ren, & Wagner, Citation2022, Garlick, Citation2023, p. 71). These ‘negatives’ may not at first sight appear to be norms; but they can be classified as such because they present a different framework for economic assistance than that promoted by the Western liberal international order (LIO).

Chinese norms undermine the LIO by presenting an alternative to what the West regards as sound principles of global governance. The US has repeatedly implied that China is not a ‘responsible stakeholder’ in the international system (Etzioni, Citation2011; Taffer, Citation2020). However, beyond this simplistic depiction, the reality is that China respects some aspects of the LIO (for instance, Westphalian sovereignty and globalised capitalist economics), while offering alternatives to others: most obviously, a relativist interpretation of human rights which subverts Western universalism (Breslin, Citation2021, p. 25). China’s insistence, based on the Westphalian concept of sovereignty enshrined in the UN constitution, on the principle of ‘non-interference’—interpreted as non-criticism and non-intervention—in the internal affairs of sovereign states even in the face of obvious human rights abuses (as in its neighbour Myanmar) constitutes a normative challenge to the West. As Shaun Breslin (Citation2021, p. 117) points out, “the process of actively promoting this anti-normative national identity (and pitching it as the antithesis of the way that other great powers act) results in it becoming a normative position of sorts in itself.” This remains the case even as China is drawn into increased engagement in global South countries, since adherence to the non-criticism aspect of the non-interference principle still stands as a normative challenge to Western ideas of ‘good’ governance and ethics. Allied with China’s growing influence in the global South, the Chinese interpretation of the concept of sovereignty inherently challenges and undermines the Western rules-based approach to democracy and human rights (Breslin, Citation2021, p. 23). It does this by influencing many global South countries’ perception of what can be regarded as ‘normal’ behaviour (Kavalski & Cho, Citation2018).

At the same time, Beijing seeks to build an alternative order to the LIO via the BRICS platform (which includes Russia, now perceived as beyond the pale in the West, as well as six new members from the global South added in September 2023). Chinese-led regional platforms such as FOCAC and the SCO have also been established without reference to the LIO. China’s relational approach to the global South can be regarded as normative diplomacy in that it is an attempt to normalise Chinese ideas about how international affairs should be conducted. As Emilian Kavalski has demonstrated, this is done by earning recognition for Chinese practices, seeking to socialise partner countries in the global South into adopting these practices (Kavalski, Citation2009, Citation2010). While ‘normative power Europe’ proposes a rules-based approach to define what is ‘normal’ in international life, China utilises an influence- and recognition-based relational approach based on “networks engendered by the practice of unlimited exchange of favours and underpinned by reciprocal obligations, assurances, and mutuality” (Kavalski & Cho, Citation2018, p. 50). In other words, rather than directly challenging the LIO, Beijing seeks to transform and subvert it according to Chinese expectations.

The paper examines Chinese normative diplomacy in the global South via an analysis of attempts to diffuse discursive and non-discursive practices. China’s attempts to diffuse discursive practices presented in leaders’ speeches are analysed using critical discourse analysis (Wodak & Meyer, Citation2001). Chinese discursive practices include characteristic discursive units such as ‘community of shared destiny’ and ‘win-win cooperation’ which do not commonly occur in standard (non-Chinese) English. Further discourse analysis, supplemented by a corpus analysis, then reveals the degree of prevalence of such discursive practices in leaders’ speeches and other official and semi-official Chinese texts. We thereafter evaluate the extent to which the Chinese discursive practices have earned recognition and acceptance from elite actors in the global South. We do this by assessing the extent to which national leaders use or echo the Chinese phrases when referring to cooperation with China.

Non-discursive practices disseminated by China include non-recognition of Taiwan (the One China policy), non-interference in Chinese internal affairs (for instance, not supporting Uighur or Tibetan independence movements), and bilateral trade and investment deals negotiated according to Chinese rather than Western norms. The prevalence of such non-discursive practices in the global South will be assessed with reference primarily to countries’ ties with Taiwan or the PRC, recognition of the non-interference principle promoted by China, the extent of engagement with China-led regional cooperation platforms, and acceptance of investment deals with Chinese characteristics. It is to be anticipated that non-discursive practices will have gained more traction than discursive practices, because of China’s greater ability to exert leverage in this area. Compliance with non-discursive practices can be achieved through coercive enforcement (namely, economic leverage) which is lacking in discursive diplomacy.

The paper is organised as follows. The first section outlines our theory of normative diplomacy and earning recognition with reference to the literatures on normative power, norm diffusion, and Chinese political and economic diplomacy. The second part of the article identifies the discursive and non-discursive norms diffused within the frameworks of the BRI, Chinese-led regional cooperation platforms, and bilateral economic diplomacy in the global South. The third section assesses the extent to which examples of discursive practices used in Chinese leaders’ speeches and other official texts have come to be accepted and used by elite actors in the global South. The final sections evaluate the extent to which Chinese non-discursive practices have gained prevalence in the global South. The conclusion draws together the theoretical and empirical aspects of the argument.

Normative diplomacy and earning recognition

Interest in norm diffusion and normative power among scholars of international relations (IR) has deepened since the 1990s, especially after the introduction of social constructivist theory to the field. However, constructivists have focused primarily on ideational rather than material norms, meaning that the theory is not able to capture the full extent of power relations between actors (Landolt, Citation2004, pp. 590–591). In 2002, Ian Manners introduced the theory of normative power as a means for explaining the actorness of the EU (Manners, Citation2002). Subsequently, Thomas Diez and Emilian Kavalski critiqued the exclusive application of the concept to the EU. They demonstrated that normative power theory could also be applied to China without losing analytical strength (Diez, Citation2005; Kavalski, Citation2013). This finding also speaks to Elias Steinhilper’s critique of the Western bias in much norm diffusion research, which tends to assume that norms are transmitted from “West to rest” (Steinhilper, Citation2015, p. 537).

However, there are some difficulties inherent in trying to establish the grounds on which China (or any other international actor, including the EU) can be classified as a normative power. Attempting to diffuse norms to gain influence is not the same as holding normative power over a region or actor. Diffusion is a dynamic process, whereas the idea of having normative power—or being a normative power—appears static and monolithic. It is not even clear what it means to have normative power. It is difficult to assess whether an actor has already gained normative power, whether it is on the road to acquiring it, or whether it has failed to acquire it. From this point of view, the concept is inherently fuzzy.

In addition, scholars have not explained the relationship between normative power and norm diffusion as clearly as they might have. This is particularly the case for China, which is, broadly speaking, engaged in a complex process of partly playing within the rules of the liberal international order and partly subverting it. Some Chinese norms stand in counterpoint to Western norms rather than being independent of them, while others have an uncertain status in terms of the extent to which they can be classified as ‘Chinese norms.’ For instance, ‘non-interference’ can, on the one hand, be seen as an attempt to counter the West’s diffusion of norms such as democracy and human rights. On the other, China’s insistence on respect for sovereignty sticks to the UN rulebook, which itself is derived from the European system of respect for the territory of states, often called the Westphalian system. As a result, the extent to which China can be considered a normative power is difficult to evaluate with precision.

Be all this as it may, scholars have pointed out that China is attempting to diffuse norms through a range of mechanisms, including regional cooperation platforms, bilateral diplomacy, economic diplomacy, official state media, and people-to-people contact: all of these now tend to be subsumed under the overarching label of the BRI (Benabdallah, Citation2019; Jakóbowski, Citation2018; Vangeli, Citation2018). Socialisation is also used as a constructivist explanation of how China persuades targeted actors to adopt its norms over an extended period. For instance, Kavalski posits that the Shanghai Cooperation Organization has socialised Central Asian states into Chinese norms of regional cooperation (Kavalski, Citation2010). Thus, the question of whether China is diffusing norms and socialising states has been affirmed by scholars, even as there is a degree of controversy and uncertainty concerning the application of normative power theory to China.

Given the difficulties surrounding the somewhat blurry relationship between normative power and norm diffusion, this paper uses the concepts of normative diplomacy and earning recognition to approach the problem from a different angle. By examining the material and ideational means by which China attempts to exert normative influence and diffuse norms, the extent to which China either has or is a normative power becomes a moot point. The emphasis is instead on how China is attempting to diffuse norms and evaluating the degree of impact (‘success’) of these attempts. It thereby becomes unnecessary to evaluate the degree to which China is or is not a normative power. The focus instead is on the dynamic process of attempts to diffuse norms and gain political influence. Normative diplomacy and earning recognition are useful as conceptual tools for analysing two important questions. The first, analysed through the concept of normative diplomacy, concerns the means by which China diffuses norms. The second, analysed through the concept of earning recognition (Garlick & Qin, Citation2023), analyses the extent to which China’s normative diplomacy can be considered successful in terms of influencing targeted actors.

We propose that China attempts to earn recognition for its practice-based norms through a range of both material and ideational methods. We summarise these under the label normative diplomacy. China’s normative diplomacy is conducted above all through its leaders and commercial actors (but also through state media and other state institutions). It includes both discursive and non-discursive practices. Discursive practices are forms of words (such as fixed slogans, customary phrases or often-used expressions), while non-discursive practices are forms of behaviour.

As far as the theory and methodology of critical discourse analysis is concerned, discourse can be perceived as a form of social practice (Fairclough & Wodak, Citation1997). At the same time, it can be understood as emerging from the exercise of power (Jäger, Citation2001, p. 34). Discourses, according to Foucault’s definition, are “practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak” (Foucault, Citation1972, p. 49). Such ‘objects’ can take the form of both discursive and non-discursive social practices, both of which emerge from social relations of power. Discursive and non-discursive practices are co-constitutive, intertwining within discourses of power (Wodak, Citation2001, p. 66). They act as conduits of power by shaping the language (discursive practices) and behaviour (non-discursive practices) of those who are the targets of influence attempts (Jäger, Citation2001, p. 37). To put it another way, discourses of power steer and sustain the linguistic and behavioural social practices from which the exercise of power emerges.

In China’s case, discursive practices consist of slogans and phrases used by Chinese leaders as speech acts designed to encourage target actors to take up a pro-Chinese position and accept cooperation with the PRC. For example, Chinese discursive practices have included frequently used phrases such as ‘community of shared destiny’, ‘win-win cooperation’, and ‘harmonious world’ (the first two were introduced by the Xi administration and the last is associated with the Hu Jintao era). It is important to note that such phrases are not intended to promote specific, concrete actions, but rather to encourage positive attitudes towards China. Non-discursive practices include Chinese approaches to regionalisation, investment, and trade deals that are often subsumed under the labels of economic diplomacy (Heath, Citation2016; Zhang, Citation2016) or economic statecraft (Norris, Citation2016). They are practices which expect a specific form of behaviour favourable to China and in cooperation with China. Both types of practices, discursive and non-discursive, are here included in the overarching term normative diplomacy.

Through its normative diplomacy, China attempts to earn recognition for Chinese practice-based norms in a ‘show not tell’ fashion. Chinese normative diplomacy contains elements of both ‘do-as-I-do’ (non-discursive practices) and ‘say-as-I-say’ (discursive practices). In a Foucauldian sense, the discursive practices create an ideational platform upon which the non-discursive practices can be situated. The Chinese approach to norm diffusion contrasts with the rule-based approach of the EU, which attempts to attach explicit, written conditions concerning human rights and democracy to its interactions with countries in the global South. It is for this reason that some developing countries accuse the EU of trying to impose its values at the expense of local ones (Hima, Citation2022, p. 46) and of lecturing about its “values and norms while showing hypocrisy” (Fitriani, Citation2022, p. 32). In contrast, through its official insistence on non-interference and mutual respect, China is regarded by some in the global South as a less didactic, hypocritical, and intrusive partner (Hima, Citation2022, p. 46). In the next section, we shall examine the characteristics of China’s normative diplomacy to reveal how it is distinct from the EU’s approach to norm diffusion.

The characteristics of China’s practice-based normative diplomacy

China attempts to diffuse two sets of interlinked practices in the global South, within the framework of the BRI: discursive and non-discursive practices. As stated above, discursive practices are forms of words—slogans and phrases—that are used repeatedly to project ideational norms to targeted actors. The implicit assumption is that the targeted actors will, over time, demonstrate their understanding and acceptance of the slogans and phrases by beginning to use them (or mutated forms of them adapted to the local context). The use of political slogans (tifa, 提法) by Chinese leaders and officials to generate support for a regime and its policies is a well-established practice dating back centuries (Karmazin, Citation2020). It is therefore natural for Chinese leaders to introduce slogans into discourse aimed at international actors.

Non-discursive practices are forms of behaviour which targeted actors are expected to adopt or accept. They are often accompanied by a verbal equivalent but are also sometimes promoted without an official verbal formulation on a ‘do-as-I-do’ basis. Non-discursive practices with distinctively Chinese characteristics include the use of regional cooperation platforms as a tool for diplomacy (Jakóbowski, Citation2018) and the utilisation of commercial actors—both state and private—as conduits of economic statecraft (Norris, Citation2016). Another characteristically Chinese non-discursive practice is the use of bilateral deals based on loans from state banks for infrastructure built by Chinese construction companies, often in exchange for access to natural resources or for the purpose of generating long-term support. Importantly, non-discursive practices promoted by the Chinese state also include what one might dub negative norms. These include norms such as the principle of non-interference in domestic affairs by external actors and the non-recognition of Taiwan, both of which are expected to be adopted as conditions of cooperation with China.

China tries to earn recognition and acceptance for the two interlinked sets of practices—discursive and non-discursive—through its normative diplomacy. This utilises speeches, articles in official media, summit diplomacy, economic diplomacy, people-to-people contact at the elite level, and other discursive and non-discursive tools. The following two sections will examine the characteristics of the discursive and non-discursive practices which together constitute China’s normative diplomacy in the global South.

Discursive practices

China’s discursive practices consist of specific phrases and slogans which are used to promote a Chinese approach to international interactions at regional and bilateral levels. They occur consistently and repeatedly in Chinese leaders’ discourse and in official media both domestically and internationally. They are clearly meant to be understood, accepted, and used by targeted actors overseas, in a similar process of diffusion as occurs within the territory of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

Here we identify six of the most significant interconnected discursive practices which are commonly used to diffuse and co-constitute Chinese norms in the global South in the BRI era. Three of these terms—’community of shared destiny/future’, ‘win-win cooperation’, and ‘people-to-people exchanges’—originate with the Xi Jinping administration in connection with the promotion of the BRI. The three others—’support/embrace multilateralism’, ‘South-South cooperation’, and ‘mutual benefit’—date back to discussions concerning cooperation between developing countries in the latter decades of the twentieth century and have therefore been adopted into Chinese discourse via a process of co-constitution. We have selected these six on the grounds that they are representative of Chinese discursive practice used to promote relations with actors in the global South. They occur frequently in Chinese leaders’ speeches and other official texts, indicating a conscious and concerted effort to socialise targeted actors in the use of practices emanating from or accepted as part of China’s overall normative agenda vis-à-vis the global South.

presents the results of a corpus analysis of the use of the six discursive practices by China’s president and other prominent government officials in BRI era speeches directed towards elite audiences in Central Asia and Africa. This corpus was selected because Central Asia and Africa are key regions included in the BRI and discourse towards them can therefore be evaluated as a representative sample of the discourse directed towards regions in the global South. The two regions are both vital partner regions for China due to their rich deposits of natural resources. As such, they have been consistent targets for Chinese economic and normative diplomacy since the 1990s (Brautigam, Citation2009; Kavalski, Citation2010). Importantly for the connectivity rationale of the BRI, both regions are also geographically on the trade route to Europe: Central Asia is positioned on the land route (the ‘Belt’) and East Africa is on the maritime route (the ‘Road’). We decided to restrict the analysis to just these two regions due to limitations of time and space. This limitation implies that the results of the analysis are likely to be suggestive rather than conclusive: further research concerning other global South regions will need to be conducted in future projects.

Table 1. The frequency of the six discursive practices in 26 speeches/reports given by Chinese leaders.

Bearing these limitations in mind, we analysed a total of 26 public speeches given by the Chinese president, prime minister, and foreign ministers at FOCAC, the meeting of the Council of Heads of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member states, and meetings of Chinese and African leaders between 2012 and 2023. Using the corpus analysis toolkit software AntConc, we extracted the usage frequency of the six discourse units from the speeches, which contained a total of 5025 word-types and 36622 word-tokens.

The results of the analysis reveal that two of the three originally Chinese discursive practices (‘community of shared destiny/future’ and ‘win-win cooperation’) are the most frequently used, while the third one (‘people-to-people exchanges’) places fourth. Somewhat surprisingly, given its evident importance for China’s relations with the global South, the expression ‘South-South cooperation’ is used the least frequently, occurring only nine times in 26 texts. However, this result is readily explicable by the fact that it emanates from the UN’s 1978 Buenos Aires Plan of Action for Promoting and Implementing Technical Cooperation among Developing Countries (BAPA).Footnote1 It thereafter began to be used in scholarly and other texts, with the earliest incidence occurring in an article by Xu Mei (Xu, Citation1981). The term has thus been co-constituted by China over the long-term rather than being an innovation in which China seeks to socialise its partners. It dates from long before the BRI era, is already known to actors in the global South, and is therefore not in need of further promotion.

Similarly, the expressions ‘support/embrace multilateralism’ and ‘mutual benefit’ arise from the historical evolution of Chinese engagement with other countries in the developing world. Although the term ‘multilateralism’ occurred in Chinese academic texts in the 1990s (Liu, Citation1995; Shi, Citation1996; Wang, Citation1995), Chinese leaders only began to introduce the idea of building an international order based on multilateralism around 2004. The notion of embracing multilateralism began to be used for diplomatic purposes when the Chinese Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing called for a deepening of Asia-Europe cooperation (Liu & Ma, Citation2004). Likewise, after previously being used mainly in discussions of domestic economic affairs during the 1980s (Zhang, Citation1986), ‘mutual benefit’ began to be used in connection with Chinese foreign policy in the mid-2000s (Huang & Li, Citation2005). Interestingly, from 2004 it began to be used in conjunction with the expression ‘win-win’, especially in the collocation ‘mutual benefit and win-win results’ (Chen, Citation2004; Du & Xie, Citation2006). By 2015, the phrase ‘mutual benefit and win-win’ had come to be associated with the BRI (Long, Citation2015). This juxtaposition suggests a close equivalence between ‘mutual benefit’ and the newly-coined expression ‘win-win cooperation.’

The analysis reveals that as far as China’s normative diplomacy is concerned, the most significant discursive practices for which Beijing seeks to earn recognition are the ones which were introduced in the BRI/Xi Jinping era. The analysis reveals that these expressions understandably tend to be repeated more by Chinese leaders than the ones which have been absorbed and co-constituted by China from discussions in the UN. Repetition is necessary to drum home the quintessentially Chinese discursive practices which are the product of Xi’s attempts to promote long-term Chinese normative agendas, while the other expressions are used to indicate China’s recognition and acceptance of terms arising from long-term discussions about cooperation between economically developing countries. The borrowed terms, when integrated with the uniquely Chinese expressions, drive home the point that co-constitution, mutual respect, and earned recognition are intended to be seen as central to Chinese normative diplomacy in the global South.

Among China’s discursive practices in the BRI era, ‘community of shared destiny/future’ is generally the most prominent and significant. It appears not only in the texts of leaders’ speeches but also in official documents, including in their titles. For instance, official government publications concerning relations with Africa and Latin America are entitled Beijing Declaration—Toward an Even Stronger China-Africa Community with a Shared Future (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, Citation2018) and Build a Community of Shared Destiny for Common Progress (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, Citation2014). Another example is the use of the expression in an article in the Jakarta Post by the PRC’s ambassador to the Association of Southeast Asian countries (ASEAN), which is entitled ‘Building community with shared future’ (Deng, Citation2020). The prominence of the ‘community of shared future/destiny’ discursive practice in Chinese discourse concerning relations with all regions of the global South indicates that it is regarded as foundational by Chinese leaders. It is intended to convey the idea that China will treat all its partners in the global South with respect while acting in a leadership role. However, such respect must be mutual, which implies that cooperation is also dependent on Chinese practices (norms) being recognised and accepted. The roots of the ‘community of shared future/destiny’ go back to the Maoist era of South-South cooperation when China financed and constructed infrastructure in Africa and Asia despite not being in a strong economic position itself. The foundation for China’s cooperation with the global South is the Eight Principles for Economic Aid and Technical Assistance to Other Countries outlined by Premier Zhou Enlai during a visit to Ghana in 1964 (Cheng & Taylor, Citation2017, p. 26). The Eight Principles provide a normative blueprint for China’s cooperation with the global South, providing continuity from the Maoist past to the present era in which Xi’s BRI dominates Chinese foreign policy towards the global South.

The other five discursive practices are intrinsically linked to ‘community of shared destiny/future’ and subsumed under it. However, their origins and implications vary subtly. For instance, the phrase ‘mutual benefit’ occurs in the first of Zhou’s Eight Principles, which also emphasises equality between partners. On the other hand, its close relative (or synonym) ‘win-win cooperation’ clearly has a more contemporary tone based in late twentieth-century Western business discourse. The two can therefore be seen as a discursive pair linking early attempts at normative diplomacy in the global South with the present-day BRI.

‘People-to-people exchanges’ is intended as an indication of how the ‘community of shared destiny/future’ will be established in practice. At the same time, the precise characteristics of the ‘exchanges’ are not specified, meaning that it is not clear what form they are supposed to take. The term suggests an even flow of personnel and ideas between partners of equal status. However, as Lina Benabdallah demonstrates in her detailed study of Sino-African relations, in practice ‘people-to-people exchanges’ tend to involve the unidirectional transfer of knowledge, expertise, and norms from China to the global South (Benabdallah, Citation2020). For this reason, ‘people-to-people exchanges’ can also be classified as a non-discursive practice which is nevertheless connected to a specific discursive practice with a rather different normative content than the discursive unit would suggest.

The other two discursive practices need more unpacking. The discursive units ‘support/embrace multilateralism’ and ‘South-South cooperation’ refer normatively to Chinese attempts to establish modes of cooperation which stand as alternatives to the US-dominated Western liberal international order (Callahan, Citation2016, p. 237). For the West, they may be perceived as symbols of a challenge to the liberal international order. Without doubt, there is substance to these suspicions since China’s normative diplomacy is clearly intended to diffuse Chinese rather than Western norms over the long-term, thus attempting to replace the Western menu of norms with a Chinese one. However, as far as Chinese leaders are concerned, they are also intended to persuade partners in the global South that there is a possible future free of structural inequalities arising from US and European global hegemony, economic disparities, Eurocentrism, and the historical legacy of colonialism.

‘South-South cooperation’ refers to the potential advantages of formerly colonised countries working together to build a better future at least somewhat free of exploitation by the nations of the global North (DeHart, Citation2012, p. 1368). Although the expression has also been used by other actors, it has been promoted by Chinese policy makers “to emphasise China’s goal of a harmonious world order based on nation-state sovereignty and mutual benefits” (DeHart, Citation2012, p. 1359). It is officially regarded by the Chinese government as “an important component of Deng Xiaoping theory” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2022a). Nevertheless, reveals that ‘South-South cooperation’ is the least used of the five discursive practices, implying that it is probably intended primarily as a theoretical underpinning to China’s normative diplomacy and less as a discursive unit that needs to earn recognition from targeted actors.

The ‘support/embrace multilateralism’ discursive practice represents China’s opposition to the perceived global hegemony of the United States and is linked to Beijing’s promotion of Chinese-led regional forums for cooperation. The collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War transformed the existing bipolar international system into a unipolar one dominated by the US. Consequently, in the 1990s Chinese leaders increasingly feared that US alliances with Asian countries would lead to the encirclement of China. Their solution was to establish new multilateral institutions which would blunt US power and reassure partners that China had peaceful intentions (Doshi, Citation2021, pp. 107–108; Zhang and Tang, Citation2005, p. 52). Accordingly, the ‘support/embrace multilateralism’ discursive practice is intended to promote Chinese influence at the expense of the US. It is intended to be an ideational foundation for Chinese regional cooperation initiatives which do not include the US. Hence, ‘support/embrace multilateralism’ connects to the non-discursive practice of establishing multilateral regional cooperation platforms in the global South such as the SCO and FOCAC. These, as we shall demonstrate in the next section, are based on a ‘N + 1′ structure where ‘N’ represents a group of regional actors and ‘1′ represents China.

A closer inspection of the texts of the speeches reveals precisely how frequently and meticulously China’s president uses the discursive units in orations directed at global South elites. Xi’s speech at the Second Belt and Road Forum in April Citation2019 contained five of the six discursive practices, with only “South-South cooperation” not used (Belt & Road Forum, 2019). Three years later, in a speech at the 14th BRICS summit, Xi used all six discursive practices (CGTN, Citation2022). In a 2021 speech at the FOCAC summit, Xi again used all the discursive units except “South-South cooperation” (FOCAC, Citation2021a).

Other senior government officials also use the discursive units heavily. For example, in a 2014 speech foreign minister Wang Yi used variations on “win-win cooperation” eleven times, “mutual benefit” five times, and added variations on “community of shared destiny” three times (China Daily, Citation2014). In 2021, at the eighth ministerial conference of FOCAC, Wang used all the discursive units except “South-South cooperation” (FOCAC, Citation2021b). In November 2022, Premier Li Keqiang’s speech at the 21st meeting of the SCO Council included variations on “win-win cooperation”, “mutual benefit”, and “people-to-people exchanges” (Xinhua, Citation2022).

Thus, it is evident that during the BRI era from 2013-2023 the six discursive practices were extensively used by China’s president and other prominent government officials in speeches directed towards elite audiences in the global South. The degree of recognition earned for these practices can be evaluated by analysing the extent to which global South leaders use, echo, or acknowledge the discursive units and practices in their own speeches. Thus, the speeches of prominent global South elites will be analysed in a subsequent section, after first outlining and analysing China’s non-discursive practices.

Non-discursive practices

China’s normative diplomacy in the global South promotes a range of non-discursive practices. Some of these can be classified as positive norms, in that a new type of relationship dynamic is constructed in which the targeted actor is expected to participate. Other non-discursive practices can be classified as negative norms, in that the targeted actor is encouraged not to take a certain action. Positive norms include the use of group cooperation diplomacy to promote regional integration and bilateral investment deals based on loans from state banks for infrastructure built by Chinese companies, sometimes also involving access to natural resources as part of the deal. Negative norms include the non-recognition of Taiwan (the One China policy) and non-interference in the internal affairs of other states (especially China’s internal affairs). While discursive practices are intended to earn recognition for China’s normative diplomacy as forms of words reproduced by targeted actors, non-discursive practices are supposed to be accepted and implemented as forms of behaviour. Essentially, discursive practices such as ‘win-win cooperation’, ‘people-to-people exchanges’, and ‘community of shared destiny/future’ pave the way for non-discursive practices to be adopted.

Group cooperation diplomacy takes the form of regional cooperation platforms. In the global South, the most significant of these are the SCO, FOCAC, the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF), and the China-CELAC Forum for cooperation between China and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States. All of these take the form of N + 1, where ‘N’ represents the group of regional member states and ‘1′ represents China (Hu, Citation2015). In some cases, such as China-CELAC, the regional grouping (‘N’) existed before the ‘N + 1′ grouping was introduced by China. In others, such as the SCO, the grouping was instigated by China. Regional cooperation platforms of this type, with annual or bi-annual meetings, are not generally a feature of US or European diplomacy in the global South, so can be considered a distinctive feature of Chinese normative diplomacy (Jakóbowski, Citation2018). Regional cooperation platforms are used as facilitating mechanisms for developing bilateral ties with individual countries included in the regionalisation structure. Bilateral relations are nested within the regional cooperation platform, which are in turn included in the BRI (see ). Within regions, China actively pursues bilateral trade and investment deals with individual states (often those with more natural resources).

Clearly, developing bilateral ties is not a uniquely Chinese activity. However, Chinese investment deals have characteristics which are not a standard aspect of Western economic diplomacy. In particular, the Chinese use of state-backed loans to fund infrastructure construction by Chinese commercial actors is not a common Western practice. As Moore (Citation2022, p. 220) puts it: “While in China close coordination between state, corporate, and sub-state entities is common, it is less typical in the West.” In addition, sending large numbers of the nation’s own citizens overseas to work on infrastructure projects is not normal for Western countries in the contemporary era. Access to natural resources as part payment is also sometimes included in the conditions attached to Chinese investments (Jenkins, Citation2022, p. 108). Since these characteristics are not typical of Western investment in the global South, China’s approach to investment deals can be considered to constitute a distinctively Chinese non-discursive practice (norm) which China is normalising in the global South. More detail concerning the implementation of this non-discursive practice will be presented later in the article.

The two negative norms promoted by China as non-discursive practices—non-interference and the One China policy—are well known and therefore do not need much explanation. With regard to the former, Chinese leaders have consistently promoted respect for sovereignty and non-interference in the internal affairs of other states since 1964: this norm is included as the second of Zhou Enlai’s Eight Principles (Cheng & Taylor, Citation2017, p. 27). There are many references to respect for sovereignty and non-interference in Chinese leaders’ speeches. Although respect for sovereignty is a Westphalian norm which emerged from Europe and is enshrined in the UN charter, the emphasis on non-interference is a Chinese addition which is a response to Western promotion of democratic and human rights norms. Thus, the non-interference principle can be considered a Chinese norm or non-discursive practice.

Both non-interference and the One China policy constitute key aspects of China’s normative diplomacy in the global South. All the same, unlike the case of the rules-based norms advocated by the EU, the PRC government does not necessarily completely cut off all cooperation with countries which do not respect these norms; rather, it continues actively to promote its full range of normative diplomacy as it attempts to win back the uncooperative countries’ favour. On this basis, like the other non-discursive practices, the non-interference principle and One China policy cannot be classified as strictly rules-based norms but should instead be classified as practices which the targeted actor is expected to recognise and follow over the long term.

The impact of China’s discursive practices

China’s leaders have applied the six discursive practices identified above quite consistently across regions in their speeches and other discourse. However, the extent to which the three uniquely Chinese and three co-constituted discursive units have earned recognition from and been co-constituted by local actors may be low or limited. Reactions will, for example, depend on whether it is expedient for targeted elites to reproduce Chinese discursive practices. Media and the general population in some countries may find such discourse repellent or even risible. Elites in some countries may not wish to be associated with phrases commonly used by Chinese leaders if doing so negatively affects their popularity with the citizenry. However, in nations where China is more popular leaders may elect to reproduce Chinese leaders’ discursive practices at times, particularly in discourse directed back at Chinese interlocutors. For instance, this may occur in leaders’ speeches in countries where opinion polls show China to be relatively popular (Lekorwe et al, Citation2016).

One study examining the impacts of Chinese discursive practices is Garlick and Qin (Citation2023). The authors found that China’s discursive practices failed to gain traction in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) after the introduction of the 16 + 1 cooperation platform in 2012. There were relatively few instances of reproduction of the practices by CEE elites. Reluctance to accept Chinese discourse can be explained with reference to phenomena such as European human rights and democratic agendas, pro-Taiwan sentiments, the understandable tendency to link China with Russia (especially after the Russian invasion of Ukraine), and CEE’s wholesale rejection of communism in 1989 (Turcsányi & Qiaoan, Citation2019). On the other hand, these factors may be less applicable to developing regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia where such issues may be of lower importance to citizens and economic issues are likely to be of more significance.

In order to evaluate the impact of Chinese discursive practices in the global South, we conducted an analysis of speeches and interviews by the leaders of four countries in sub-Saharan Africa and four in Central Asia (Turkmenistan is excluded on the grounds that it is not a full member of the SCO and tends to isolationism). To limit the selection to four sub-Saharan African countries in order to facilitate a regional comparison based on an identical n-value, we focused on speeches and interviews by the leaders of the two largest sub-Saharan economies by gross domestic product (Nigeria and South Africa), plus two others which have smaller economies but possess significant natural resources and are thus also likely to be the targets of Chinese normative diplomacy (Zambia and Angola). Since there was a need for speeches aimed at an international audience, we analysed speeches at the 2022 and 2023 United Nations General Assembly sessions, where a representative of each country spoke once on each occasion.Footnote2 This means that two speeches per country were analysed, one for each year. Within these speeches, we searched for the six discursive units outlined above.

The sample obtained is intended to correspond roughly to the analysis of Chinese leaders’ speeches earlier in this paper targeted specifically at audiences in Central Asia and Africa. The intention is to evaluate the impact of the six discursive practices identified earlier in this paper on leaders in these two regions of the global South after almost a decade of China’s BRI normative discourse under President Xi. Impact was assessed in terms of the degree of recognition earned for these practices reflected in their presence or absence in the speeches in a form which is identical with or close to the Chinese original phrase.

The analysis reveals that of the six Chinese discursive practices listed above, two—“mutual benefit” and “support/embrace multilateralism”—occurred frequently in the sixteen speeches analysed, albeit sometimes in somewhat different forms of words. The other four discursive units did not appear at all in any of the speeches. Thus, the only two which were used at all were discursive units which originated before the Xi presidency and which have been co-constituted by China rather than being originally Chinese. The Xi era discursive units were not used at all by Central Asian and sub-Saharan African leaders (see ). This is in spite of the fact that the Central Asian and sub-Saharan African leaders frequently talked about their vision of the future in general terms, in a similar vein to the Chinese discourse. Although they frequently used words and phrases such as “cooperation” and “international community”, they did not use the Chinese discursive units.

Table 2. Results of the analysis of 16 Central Asian and sub-Saharan African leaders’ speeches.

Based on this analysis, it would appear that the Xi era discursive practices have made little or no impression on global South leaders. However, in a further internet search we discovered some evidence of reproduction or close reproduction by some global South leaders in some speeches and texts directed at Chinese leaders as well as those from other global South countries.

The most notable example of close reproduction comes from Cyril Ramaphosa, President of South Africa. At the FOCAC summit in 2018, Ramaphosa used five of the discursive practices in his speech: “mutual benefit”, “south-south cooperation”, “shared commitment to multilateralism”, “people-to-people cooperation”, and “community of shared future” (The Presidency, Citation2018). It should be noted that the last two of these are uniquely Chinese discursive units, while the first three are ones which originate from discussions between global South actors and have been co-constituted by China. The only discursive practice which he did not reproduce was the third uniquely Chinese discursive unit “win-win cooperation.” This speech reveals a degree of recognition of Chinese discursive practices. This may, however, mainly be due to the fact that he knew he was addressing Chinese interlocutors and consciously chose to demonstrate some good will in this instance.

Another case of a degree of earned recognition and co-constitution comes from the former Ethiopian President Mulatu Teshome, who was educated in China. In a 2022 interview with Chinese state media, he used the following discursive practices: “multilateralism, openness and cooperation”, and “community with a shared future” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, Citation2022b). Here the uniquely Chinese ‘community with a shared destiny/future’ discursive unit is noticeable. However, the value of this finding is limited due to the fact that he was aware he was talking to Chinese state media and thus may have been reflecting back at them the type of discourse they expected to hear.

On the other hand, we did not find the discursive units in any Central Asian presidents’ speeches. Although Chinese media repeatedly used them when reporting on meetings between Chinese and Central Asian leaders, we could find no instances of faithful reproduction in direct quotations. Instead, the discursive units were used in official Chinese media reports to describe in indirect quotation what had been discussed, or were used in quotations of what had been said by Chinese rather than Central Asian leaders. This finding reveals the extent to which the Chinese discourse persistently employed the phrases, demonstrating the consistent effort to earn recognition for them. However, it also reveals an absence of direct reproduction by the target actors.

Two factors probably contribute to the lack of co-constitution in Central Asian discourse. The first is the Sinophobia which tends to be prevalent in the region, especially in neighbouring Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (Kyzy, Citation2021; Owen, Citation2017). Many people in Central Asian countries have a deeply-rooted mistrust of Chinese intentions and being ‘flooded’ by Chinese, partly based on historical experience of cross-border conflicts. The second factor is the fact that Central Asian countries were part of the Soviet Union. Their identities are thus closely entwined with Russia’s, including having sizeable Russian minorities and many people speaking Russian. Due to both factors, it is therefore likely that leaders do not wish to be seen by the public and their Russian counterpart as aligning themselves too closely with China, even at the same time that their countries’ economic fortunes become increasingly dependent on trade and investment with China.

In short, we find that Chinese discursive practices were reproduced only by some global South leaders, and only when they knew they were addressing Chinese interlocutors. Often, even in these cases, the discursive units appeared as echoes of the original phrases rather than faithful reproductions. This finding demonstrates that while Chinese efforts to earn “say-as-I-say” recognition for the discursive practices were consistent (and persistent), the results in terms of co-constitution in the discourse of global South leaders were generally limited. However, it is to be expected that while Chinese discursive practices have achieved limited traction in the global South, the story is likely to be different with non-discursive practices, which contain a degree of coercive process.

The impact of China’s non-discursive practices

To evaluate the impact of China’s non-discursive practices, one needs to acknowledge not only what global South actors are doing, but also what they are not doing. In other words, recognition of China’s negative norms is as important as acceptance and participation in practices which constitute an alternative to Western expectations of international cooperation. Accordingly, this section will outline some examples of global South countries’ recognition and acceptance of both positive and negative norms originating from China. Inevitably, given space restrictions, this section can present only a brief exploratory overview of the impacts, indicating the need for further book-length studies of China’s relations with the global South along the lines of Murphy (Citation2022) and Doshi (Citation2021).

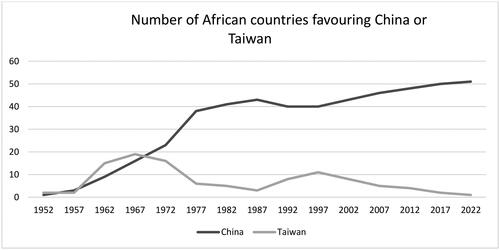

Evidence of the steadily growing impact of China’s non-discursive practices in the global South comes from a range of empirical data. Examples include the general lack of support for condemnation of the PRC’s actions in Xinjiang province, most notably in Muslim countries, and the steady increase in countries establishing ties with the PRC at the expense of the ROC over the seventy years from 1952-2002. As an illustration of the latter point, reveals that by 2022 only one out of 52 African countries still had formal ties with Taiwan; the number of ROC supporters had been as high as nineteen in the mid-1960s. In the 1990s, after the end of the Cold War and the advent of US unipolarity, there was a return to Taiwan by some African nations. A factor in this was probably the reduction in the levels of aid during the post-Mao era (Cheng & Taylor, Citation2017, p. 100). Alarmed by the rise in support for the ROC, Beijing worked to reverse the trend after 1997, leading to a steady drift of countries back to the PRC’s side. Overall, across the global South, by 2022 only thirteen economically developing nations still had full diplomatic relations with Taiwan. It is therefore clear that the ‘One China’ negative norm had been accepted by the vast majority of nations in the global South.

Figure 2. Number of African countries favouring China or Taiwan.

Source: authors, based on data obtained from Rich and Banerjee (Citation2015) and Panda (Citation2020)

In the global South, most countries have joined Chinese regional cooperation mechanisms and actively participate in meetings. These are held at regular intervals and at different levels (for instance, summit and ministerial). FOCAC contains 53 out of 54 African countries; Eswatini (which officially recognises Taiwan) is the only non-participant.Footnote3 The China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF) includes 21 out of 22 Arab states; Syria, which was suspended from the Arab League in 2011, is the only absentee.Footnote4 The China-CELAC Forum contains 33 members apart from China (China-CELAC Forum, Citation2016). The SCO has seven members apart from China, while four more states (Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran, and Mongolia) are interested in gaining full membership and nine more states (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Egypt, Nepal, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, and Turkey) are ‘dialogue partners.’Footnote5 The only notable state in the Central Asian region which rejects membership of the SCO is Turkmenistan. In short, well over one hundred economically developing countries participate in these four Chinese-led regional cooperation platforms, with very few non-participants. This indicates that China’s regionalising group cooperation norm has been recognised and accepted by the majority of nations in the global South.

Active participation in BRI meetings is also high. Leaders of over 120 countries, predominantly from the global South, attended the BRI Forum in Beijing in October 2023, even in the absence of representatives from the global North. The only European leader to attend was Viktor Orbán of Hungary. Similarly, the BRICS summit in September saw the admittance of six new members: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Attendance at these meetings can be interpreted as showing deference to Beijing as a benefactor of the global South simply in order to obtain more BRI benefits. Be that as it may, the presence and enthusiastic participation of global South leaders at China-led or China-dominant summits is indicative of general acceptance of Chinese normative practices concerning international cooperation which present an alternative and a challenge to the Western-led LIO. Simultaneously, Xi Jinping’s non-participation in the Western-led G20 summit in September, shortly after the BRICS meeting, sent a ‘do-as-I-do’ signal to the global South, even while no intention was overtly communicated.

As already stated, China’s BRI economic diplomacy has different characteristics to anything attempted by Western countries: most notably, state-backed loans on Chinese terms for infrastructure construction by Chinese companies. Many global South countries have opted to accept Chinese loan-for-infrastructure deals. For instance, they are the backbone of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which tends to be enthusiastically accepted and promoted by Pakistani leaders, scholars, and official media (Garlick, Citation2022, p. 3). By 2017, China was the largest supplier of finance for infrastructure in Africa (Sun, Jayaram, & Kassiri, Citation2017, p. 14). Loans for transport and energy infrastructure construction by Chinese companies in Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 55 per cent of total Chinese lending between 2000 and 2018 (Jenkins, Citation2022, p. 128). Chinese projects completed increased twenty-fold between 2003 and 2019, with almost 90,000 Chinese workers employed on projects in sub-Saharan Africa in 2019 (Jenkins, Citation2022, p. 124). As discussed above, the presence of large numbers of Chinese workers in Africa is another indication that these projects are being conducted according to Chinese norms; the use of large numbers of the nation’s own workers on overseas projects conducted by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is not generally a standard practice for Western countries.

People-to-people exchanges, in the form of fully-funded training trips to China for selected military, journalistic, and civil service elites, as well as funded scholarships for selected students, constitute another significant aspect of China’s norm diffusion (Benabdallah, Citation2020, p. 7). As we have seen, such “exchanges”, which are primarily unidirectional, connect to a key discursive practice initiated by Chinese leaders. Their inclusion as one of the main goals of the BRI, with a non-discursive aspect linked to the uniquely Chinese discursive practice, means that they can be classified as a non-discursive practice which is consistently used as part of China’s BRI normative diplomacy. Examples of people-to-people exchanges include annual delegations of military officers from Angola and Botswana being sent to China for training (Benabdallah, Citation2020, p. 76).

In short, despite the fact that impacts of Chinese norms are often uneven, there is evidence to demonstrate that distinctively Chinese non-discursive practices have been accepted by many countries in the global South. The PRC has earned a high degree of recognition for this portion of its normative diplomacy without attaching explicit conditions to it in the way that the West tends to do. At the same time, China expects its partner countries to adopt and follow Chinese practice-based norms in a ‘do-as-I-do’ manner. The use of practice-based norms which targeted actors are expected to observe and adopt (as opposed to the EU’s use of written conditions attached to aid) is in itself a characteristic of China’s normative diplomacy.

Conclusion

This article posits that Chinese norm diffusion in the global South has a different character to that of the West. Rather than a rules-based approach which attaches conditions to aid and investment, the PRC uses a practice-based approach which is based on earning recognition and acceptance for Chinese norms. Instead of focusing on the somewhat blurry concept of normative power, we posit that China’s norm diffusion in the global South can be conceptualised as normative diplomacy, involving the intertwined use of both discursive and non-discursive practices. Discursive practices consist of forms of words and can be found in Chinese leaders’ speeches, to which global South leaders are supposed to respond by reproducing them in their own discourse. Non-discursive practices consist of forms of behaviour such as non-interference or engagement with Chinese-led regional cooperation platforms. In essence, the Chinese approach is ‘do as I do’ and ‘say as I say’, rather than the West’s ‘do as I say’.

Although China’s discursive practices appear to have far less impact than the non-discursive practices, it is important to understand that the two are used to promote China’s normative diplomacy as a package. Discursive practices provide a rhetorical and ideational groundwork upon which non-discursive practices are established. Thus, evidence of the apparent failure of Chinese normative discourse has to be set against the considerable degree of success the Chinese government has achieved in earning recognition for non-discursive practices across much of the global South. This finding has implications for interpretations of China’s normative power and norm diffusion, adding to the body of literature in these areas.

In looking at discourse produced by the leaders of sub-Saharan African and Central Asian countries, we found that there is limited or low reproduction of Chinese discursive practices. With regard to non-discursive practices, there is more evidence of earned recognition and acceptance for Chinese norms. For instance, most global South countries participate in China-led regional cooperation platforms. As a case in point, almost all African countries have established formal partnerships with the PRC at the expense of Taiwan. Overall, Chinese non-discursive practices are becoming established and emulated in much of the global South.

However, the overall picture of China’s normative diplomacy is not all plain sailing for China. There is mistrust of China’s intentions in some parts of the global South—notably, in Central Asia—and a reluctance in some quarters to participate in Chinese practices or to reproduce Chinese norms. Such evidence of Sinophobic suspicion indicates that China’s practice diffusion via normative diplomacy still has a long way to go if it is to earn recognition in the global South, and that there is still an opportunity for the West to promote rival initiatives to the BRI.

As a practice-based form of norm diffusion, China’s normative diplomacy has achieved a degree of success in the global South, especially in its non-discursive aspects. Observers in the West would be wise to acknowledge this success if they genuinely intend to establish initiatives which compete with China’s BRI. The success of the EU’s Global Gateway and the USA’s B3W initiatives will depends in large part on their ability to diffuse Western norms effectively. Understanding the reasons behind China’s success in diffusing its non-discursive norms through a practice-based normative diplomacy should be the first step in constructing a solid foundation for a more effective engagement with the countries of the global South.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jeremy Garlick

Jeremy Garlick is the Director of the Jan Masaryk Centre for International Studies, a research centre within Prague University of Economics and Business, at which he is an associate professor. He specialises in China’s international relations and international relations theory. He has published numerous peer-reviewed articles on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and related topics. He has also published two books on the BRI and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (both published by Routledge). A third book entitled Advantage China: Agent of Change in an Era of Global Disruption will be published by Bloomsbury in November 2023.

Fangxing Qin

Fangxing Qin teaches Czech language and Czech studies at the School of European Languages and Cultures of Beijing Foreign Studies University. She obtained her PhD in 2022 from Prague University of Economics and Business under Jeremy Garlick’s supervision. She has co-authored three impact articles on China’s normative power in Central and Eastern Europe and related topics with Dr Garlick and is currently writing a book based on her PhD thesis to be published by Routledge. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/intergovernmental-coordination/south-south-cooperation-2019.html

2 Speeches obtained from the archive at the UN General Assembly General Debate website. Available at: https://gadebate.un.org/en/sessions-archive.

3 See FOCAC website at http://www.focac.org/eng/ltjj_3/ltffcy/.

4 See BRICS Policy Center website at https://bricspolicycenter.org/en/forum-de-cooperacao-china-paises-arabes/#_ftn1.

5 See United Nations website, ‘Shanghai Cooperation Organization’, at https://dppa.un.org/en/shanghai-cooperation-organization.

References

- Belt and Road Forum. (2019, April 26). Working together to deliver a brighter future for Belt and Road cooperation. Available at: http://www.beltandroadforum.org/english/n100/2019/0426/c22-1266.html.

- Benabdallah, L. (2019). Contesting the international order by integrating it: The case of China’s Belt and Road initiative. Third World Quarterly, 40(1), 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1529539

- Benabdallah, L. (2020). Shaping the future of power: Knowledge production and network-building in China-Africa relations. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Brautigam, D. (2009). The Dragon’s gift: The real story of China in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Breslin, S. (2021). China risen? Studying Chinese global power. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Callahan, W. A. (2016). China’s “Asian dream”: The Belt and Road Initiative and the new regional order. Asian Journal of Comparative Politics, 1(3), 226–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057891116647806

- CGTN. (2022, June 24). Full text: Xi Jinping’s speech at the 14th BRICS summit. Available at: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2022-06-24/Full-text-Xi-Jinping-s-speech-at-the-14th-BRICS-Summit-1b6CYOtRtja/index.html.

- Chen, S. (2004). Strengthen regional cooperation and achieve mutual benefit and win-win results: Effectively handle several relationships in regional economic cooperation. Guangdong Economy, (11), 31–32.

- Cheng, Z., & Taylor, I. (2017). China’s aid to Africa: Does friendship really matter? Abingdon: Routledge.

- China Daily. (2014, December 26). Full text of Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s speech on China’s diplomacy in 2014. Available at: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2014-12/26/content_19173138.htm.

- China-CELAC Forum. (2016). Basic information about China-CELAC forum. Beijing: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China, Department of Latin American and Caribbean Affairs, p. 5. Available at: http://www.chinacelacforum.org/eng/ltjj_1/201612/P020210828094665781093.pdf.

- DeHart, M. (2012). Remodelling the global development landscape: The China Model and South–South cooperation in Latin America. Third World Quarterly, 33(7), 1359–1375. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2012.691835

- Deng, X. (2020, March 9). Building community with shared future. The Jakarta Post. Available at: http://asean.china-mission.gov.cn/eng/dshd/202003/t20200311_8235451.htm.

- Diez, T. (2005). Constructing the Self and Changing Others: Reconsidering `Normative Power Europe’. Millennium - Journal of International Studies, 33(3), 613–636.

- Doshi, R. (2021). The long game: China’s grand strategy to displace American order. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Du, F., & Xie, L. (2006). The relationship between China and the world: Seeking mutual benefit and win-win results: Summary of arguments from the international academic symposium China and the World: Strength, Role and Strategy. Journal of the Party School of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, (01), 110–112.

- Etzioni, A. (2011). Is China a responsible stakeholder? International Affairs, 87(3), 539–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2011.00989.x

- Fairclough, N., & Wodak, R. (1997). Critical discourse analysis. In van Dijk, T. (Ed.), Discourse studies: A multidisciplinary introduction (Vol. 2). London: SAGE.

- Fitriani, E. (2022). Indonesia: Hoping for more active EU relations. In R. Balfour, L. Bomassi, & M. Martinelli (Eds.), The southern mirror: Reflections on Europe from the Global South (pp. 31–39). Brussels: Carnegie Europe.

- FOCAC. (2021a, December 2). Full text: Keynote speech by Chinese president Xi Jinping at opening ceremony of 8th FOCAC ministerial conference. Available at: http://www.focac.org/eng/gdtp/202112/t20211202_10461080.htm.

- FOCAC. (2021b, December 6). Report by State Councillor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the Eighth Ministerial Conference of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. Available at: http://www.focac.org/eng/zywx_1/zyjh/202201/t20220124_10632451.htm.

- Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge. New York, NY: Harper Colophon.

- Garlick, J. (2020). The impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: From Asia to Europe. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Garlick, J. (2022). Reconfiguring the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Geo-economic pipe dreams versus geopolitical realities. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Garlick, J. (2023). Advantage China: Agent of change in an era of global disruption. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Garlick, J., & Qin, F. (2023). China’s normative power in Central and Eastern Europe: ‘16/17 + 1’ cooperation as a tale of unfulfilled expectations. Europe-Asia Studies, 75(4), 583–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2023.2179601

- Heath, T. R. (2016). China’s evolving approach to economic diplomacy. Asia Policy, 1(1), 157–191. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2016.0020

- Hima, M. B. G. (2022). Niger: Mixed perceptions amid varying awareness of the EU. In R. Balfour, L. Bomassi, & M. Martinelli (Eds.) The southern mirror: Reflections on Europe from the Global South (pp. 41–49). Brussels: Carnegie Europe.

- Hu, D. (2015). Analysis of the group cooperation diplomacy of China, with discussion of China-CEEC cooperation [zhongguo zhengti hezuo waijiao ingxi jiantan zhongguo zhongdongou guojia hezuo]. International Studies, 6, 75–88.

- Huang, J., & Li, L. (2005). Mutual benefit and common prosperity—Memory of the Second China-ASEAN Expo and Business and Investment Summit. Contemporary Guangxi, (21), 30–32.

- International Monetary Fund. (2023, October). World economic outlook database. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/October/.

- Jäger, S. (2001). Discourse and knowledge: Theoretical and methodological aspects of a critical discourse and dispositive analysis. In Wodak, R. & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis. London: SAGE.

- Jakóbowski, J. (2018). Chinese-led regional multilateralism in Central and Eastern Europe, Africa and Latin America: 16 + 1, FOCAC, and CCF. Journal of Contemporary China, 27(113), 659–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1458055

- Jenkins, R. (2022). How China is reshaping the global economy: Development impacts in Africa and Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Karmazin, A. (2020). Slogans as an organizational feature of Chinese politics. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 25(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-019-09651-w