Abstract

Objective

This prospective cohort study aimed to compare the clinical efficacy and safety of goserelin 10.8 mg administered trimonthly with goserelin 3.6 mg administered monthly in premenopausal females with symptomatic adenomyosis.

Methods

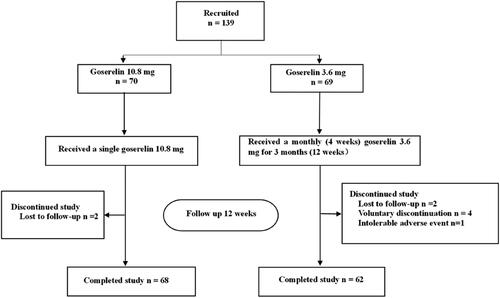

We recruited 139 premenopausal females with adenomyosis who complained of dysmenorrhea and/or menorrhagia. The first group (n = 70) received a single subcutaneous injection of goserelin 10.8 mg, and the second group (n = 69) received monthly subcutaneous goserelin 3.6 mg administered for 3 months. Follow-up was performed at the outpatient department after 12 weeks.

Results

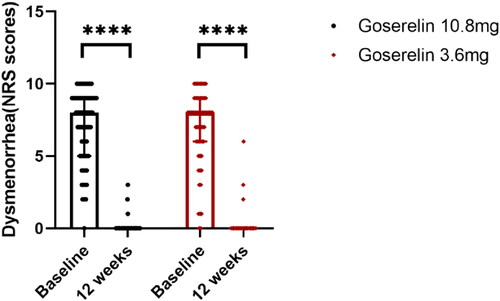

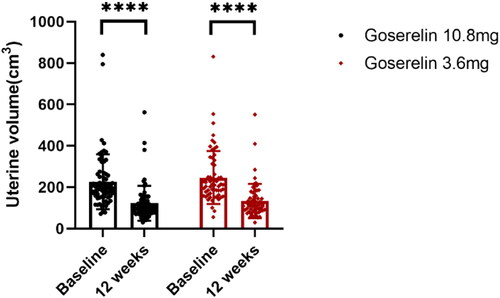

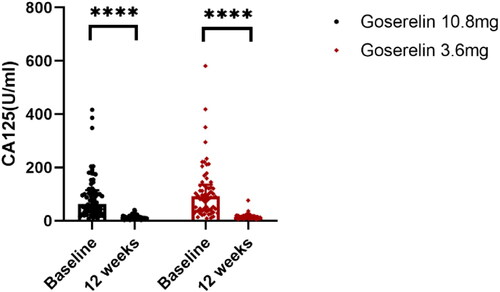

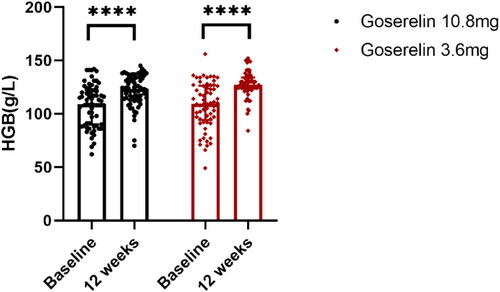

Ultimately, 130 patients completed the study, including 68 and 62 patients in the goserelin 10.8 mg (n = 70) and 3.6 mg (n = 69) groups, respectively. We observed a significant decrease in the dysmenorrhea (NRS) score, uterine volume, and cancer antigen 125 (CA125) levels, and a significant increase in hemoglobin (HGB) levels in both treatment groups. There was no significant difference between the two groups. The sum of the adverse event scores was slightly higher in the goserelin 3.6 mg than in the 10.8 mg group.

Conclusions

The clinical efficacy of trimonthly administration of goserelin 10.8 mg was equivalent to monthly 3.6 mg dosing and was non-inferior regarding safety and tolerability. Hence, it can be a more cost-effective and convenient alternative treatment option in premenopausal females with symptomatic adenomyosis.

Trial registration

ChiCTR2200059548

Introduction

Adenomyosis is a common benign gynecological disease that refers to lesions caused by invasion of the endometrium (including glands and stroma) into the myometrium. It has been traditionally labeled an ‘elusive’ disease because the exact etiology and occurrence are unknown [Citation1]. The main clinical symptoms of adenomyosis include dysmenorrhea, hypermenorrhea, and subfertility, which can seriously impact the physical and mental health of patients. Current treatments for adenomyosis include drugs, surgery, radiation, ultrasound intervention, or a combination of these approaches. Hysterectomy has traditionally been the definitive treatment for patients with adenomyosis. However, it is not suitable for patients with reproductive aspirations. Although fertility-sparing procedures such as adenomyomectomy and cytoreductive surgery are now available and may improve fertility, they may increase the risk of uterine rupture after pregnancy [Citation2, Citation3]. Moreover, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) and uterine artery embolization (UAE) are also beneficial in treating adenomyosis. However, the long-term effects of these two techniques in managing adenomyosis and their impact on pregnancy remain to be further studied [Citation4]. From the perspective of symptom relief and fertility promotion, medical treatment may be the first choice for patients with symptomatic adenomyosis.

The drugs now commonly used to relieve pain and reduce bleeding in adenomyosis mainly include oral contraceptives, progestins, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a), levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), and non-hormone drugs such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) [Citation5, Citation6]. GnRH-a is generally not the drug of choice for therapy due to its hypoestrogenic side effects [Citation7], but it is popular among Chinese patients due to its effective and rapid pain relief, treatment of menorrhagia, and reduction of uterine volume. Goserelin acetate (Zoladex, AstraZeneca, England) is a synthetic decapeptide analogue of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH); clinical therapy formulations include subcutaneous goserelin with sustained-release over 1 (3.6 mg) or 3 (10.8 mg) months. The monthly form is commonly used in the clinical treatment of adenomyosis and endometriosis. The trimonthly form, mainly used for treating prostate cancer, is now gradually used for treating breast cancer and several benign gynecological diseases. In treating premenopausal patients with early estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer, administration of the trimonthly form showed the same clinical efficacy and tolerability as administration of the monthly one [Citation8]. In patients with uterine leiomyomas, trimonthly administration of goserelin resulted in a more significant reduction in uterine size than monthly administration over 3 months and the same improvement in anemia level [Citation9]. Still, there are currently no valid clinical studies using goserelin 10.8 mg to treat adenomyosis. Therefore, we conducted this prospective cohort study to compare the clinical efficacy and safety of administering trimonthly and monthly goserelin forms to premenopausal females with symptomatic adenomyosis.

Materials and methods

Study population

This prospective cohort study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital of Shandong University (number 2021, 280) and mainly recruited premenopausal patients complaining of dysmenorrhea and/or menorrhagia who visited the gynecological outpatient department of Qilu Hospital of Shandong University from July 2021 to February 2022. Conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, all patients provided written informed consent before participating in the study. Eligible patients for this study were female patients aged 18–50 years with dysmenorrhea and/or menorrhagia, and were diagnosed with adenomyosis by ultrasound. The ultrasonographic features include globular uterine enlargement, asymmetric myometrial thickening, heterogeneous myometrium, translesional vascularity, myometrial cysts, presence of thin ‘venetian blind’ shadows, subendometrial lines and buds, echogenic islands within the myometrium, and irregular or interrupted junctional zone [Citation10, Citation11]. All ultrasonographic examinations were performed by the same professional. Exclusion criteria included patients who were currently pregnant or breastfeeding; received hormone therapy within 3 months before starting treatment; had undergone adenomyosis-related surgical or interventional therapy; were currently treated with a LNG-IUS; were diagnosed with myoma or other forms of endometriosis (e.g. deep endometriosis, endometrioma); were suspected or diagnosed with uterine malignancy, coagulation disorders, or other endocrine diseases.

Study design

This was a prospective open-label study. The patients were alternately assigned to one of the two groups according to the enrollment order in this trial. The first group (n = 70) received a single subcutaneous injection of goserelin 10.8 mg, and the second group (n = 69) received a monthly (4 weeks) subcutaneous injection of goserelin 3.6 mg for 3 months (12 weeks). The patients’ general demographics and disease characteristics were collected at trial enrollment. The degree of dysmenorrhea was assessed using the numerical rating scale (NRS) ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 representing ‘no pain’ and 10 representing ‘intolerable pain’. HGB levels were primarily used to assess hypermenorrhea. Hematologic analysis for HGB levels and CA125, and gynecologic ultrasonography to assess uterine size were performed in each patient within one week before the initiation of treatment. The formula length × anteroposterior diameter × transverse diameter × 0.523 was used to calculate the uterine volume [Citation12]. Follow-up, including gynecological ultrasonography, hematological data, and NRS score, was performed in the outpatient department after 12 weeks of treatment. Adverse events reported by the patients throughout the study were recorded at 12-week follow-up. The adverse events were scored on a 4-point scale: 0 = none, 1 = mild (mild symptom that does not require medical intervention), 2 = moderate (obvious but tolerable symptom that does not affect normal life and work nor require medical intervention), 3 = severe (serious, intolerable symptom that affects normal life and work, and requires medical intervention), and the total score was calculated. Finally, the therapeutic efficacy of the two different forms of goserelin was mainly evaluated by the changes in uterine volume, NRS score, HGB and CA125 levels before and after treatment, and safety and tolerability were evaluated by the adverse event score and incidence.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 26 was used to analyze the general information and clinical data of the patients who completed the study. Independent samples t-tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare pretreatment values, treatment outcomes, and adverse event scores between the two groups. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the treatment effects within the two groups. p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

We alternately assigned 139 females who met the study selection criteria to the two treatment groups; 70 and 69 patients were assigned to the goserelin 10.8 mg and 3.6 mg groups, respectively. Two patients in the trimonthly and monthly group each were lost to follow-up. Treatment was discontinued in five patients in the monthly group, four of which discontinued voluntarily while one for intolerable adverse events of hot flashes. Ultimately, 130 females with adenomyosis (goserelin 10.8 mg group = 68, goserelin 3.6 mg group = 62) who enrolled in the study completed the follow-up period (). The baseline and disease characteristics were generally similar between the two groups (), with no significant differences in age, body mass index (BMI), dysmenorrhea score, CA125 and HGB levels, and uterine volume before treatment. Although the median CA125 value of the monthly group was higher than that of the trimonthly one, the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 1. Baseline patient demographics and disease characteristics.

Treatment outcomes

The treatment outcomes of the two groups are shown in . After 12 weeks of treatment, the dysmenorrhea scores (), uterine volume (), and CA125 levels () were significantly decreased in both groups, HGB levels () were significantly increased, and there was no significant difference between the two groups (p = .62, p = .32, p = .27, p = .05, respectively). In addition, our analysis of patients with pretreatment anemia showed significantly elevated HGB levels after 12 weeks in both groups with no statistically significant difference (p = .11).

Figure 2. Dysmenorrhea scores from baseline to 12 weeks in goserelin 10.8 mg and 3.6 mg groups, 12 weeks vs baseline p < .0001.

Figure 3. Uterine volume from baseline to 12 weeks in goserelin 10.8 mg and 3.6 mg groups, 12 weeks vs baseline p < .0001.

Figure 4. CA125 from baseline to 12 weeks in goserelin 10.8 mg and 3.6 mg groups, 12 weeks vs baseline p < .0001.

Figure 5. HGB from baseline to 12 weeks in goserelin 10.8 mg and 3.6 mg groups, 12 weeks vs baseline p < .0001.

Table 2. Treatment outcomes in goserelin 10.8 mg and goserelin 3.6 mg groups.

Menstruation

Regarding menstruation, the proportion of patients who experienced menses in the fourth week was 92.65% (63/68) and 91.94% (57/62) in the goserelin 10.8 and 3.6 mg treatment groups, respectively, of which 26.98% (17/63) and 28.07% (16/57) experienced prolonged menstruation. In the 3.6 mg group, the proportions of patients who experienced menstruation at weeks eight and 12 were 6.45% (4/62) and 1.61% (1/62), respectively. Simultaneously, in the 10.8 mg group, all patients had amenorrhea in weeks eight and 12.

Adverse events

The total adverse event score at the 12-week follow-up was 30 and was slightly higher in the goserelin 3.6 mg than in the 10.8 mg group (9.73 ± 5.28 vs. 7.62 ± 4.98, p = .02). shows the incidence of adverse events in both groups. Among them, the most common were hyperhidrosis (79.03% and 72.06%), hot flashes (82.26% and 66.18%), irritability (67.74% and 55.88%), insomnia (53.23% and 52.94%), and arthralgia (50.00% and 55.88%) in the 3.6 mg and 10.8 mg groups, respectively.

Table 3. Incidence of adverse events occurring in goserelin 10.8 mg and 3.6 mg groups.

Discussion

This study showed that in premenopausal patients with symptomatic adenomyosis, both single trimonthly (10.8 mg) and monthly (3.6 mg) administration of goserelin for 3 months significantly reduced uterine volume, relieved dysmenorrhea symptoms, improved anemia, and reduced CA125 levels. There was no significant difference in clinical efficacy between the two formulations. The most commonly used GnRH-a in the clinical treatment of uterine adenomyosis is the monthly dosage form, injected every 4 weeks for 3–6 months or longer, which increases the burden on patients and is inconvenient. The results of this study showed that trimonthly goserelin is a valid and cost-effective treatment alternative for Chinese patients with adenomyosis.

In our study, a total of 120 (92.31%) of 130 patients reported ≥ 1 adverse event, including 91.18% (62/68) of patients in the trimonthly and 93.55% (58/62) of patients in the monthly group. There was no difference in the incidence of adverse events between the two groups. The majority of adverse events were mild or moderate. The most frequently observed adverse events after treatment with trimonthly goserelin, such as vasomotor syndrome, mood instability, reduced bone mineral density, genital dryness, and sleep disturbance, were consistent with those previously reported in clinical practice of monthly goserelin [Citation13], and no new safety signals were identified.

The adverse events in our study are thought to be related to the hypoestrogenic side effects of GnRH-a, which is a factor limiting its use. Medical treatment of adenomyosis, such as LNG-IUS, seems to be the most effective first-line treatment for adenomyosis-related pain and bleeding [Citation14]. However, if the patient’s uterine volume is too large (> 150 ml) at the time of LNG-IUS placement, the treatment failure rate significantly increases [Citation15, Citation16]. Regarding other medical treatments, it has shown that progestins alone cannot effectively improve anemia and reduce uterine volume in patients with adenomyosis [Citation17]. The eligible patients in our study were not suitable for initial treatment with drugs such as LNG-IUS or progestins due to large uterine size (> 150 ml), severe anemia, or severe dysmenorrhea. Due to its rapid effectiveness in relieving pain, improving menorrhagia, and reducing uterine volume, GnRH-a is more in line with the needs of Chinese patients.

Administration of the 3.6 mg or 10.8 mg formulations of goserelin resulted in an initial increase in luteinizing hormone (LH) and serum estradiol (E2) levels (flare-up effect) [Citation18], followed by a decrease in serum LH levels when the pituitary LHRH receptors are occupied, and E2 is suppressed within the menopausal range. Subsequently, serum E2 levels were suppressed during treatment with goserelin [Citation19], which is one of the rationales for GnRH-a in adenomyosis treatment [Citation20]. In a study by Masuda et al. (2011) on the use of goserelin combined with tamoxifen to treat early breast cancer, E2 concentrations in both the 10.8 mg and 3.6 mg treatment groups were suppressed to postmenopausal levels after 4 weeks of treatment. This suppression remained constant throughout the study, and there was no apparent difference in E2 suppression between trimonthly and monthly administration of goserelin [Citation8]. Another 24-week clinical study in premenopausal patients with advanced breast cancer reported similar estrogen suppression results [Citation21]. The initial flare-up effect of GnRH-a caused menstrual prolongation in both goserelin 10.8 mg (26.98% [17/63]) and 3.6 mg (28.07% [16/57]) group in the fourth week after injection, and no heavy bleeding occurred. Furthermore, suppression of sex hormones caused amenorrhea in most patients in the monthly group (93.55% [58/62]) and 98.39% [61/62], respectively) and all patients in the trimonthly group at weeks eight and 12 after injection.

Following injection of the 10.8 mg formulation, plasma concentrations of goserelin peaked at 2.4 h post-injection, then declined rapidly within 48 h, and steadily decreased over 12 weeks [Citation8]. This was due to the difference in the ratio of the lactide/glycolide copolymer contained in the two sustained-release formulations. The lactide/glycolide ratio was 95:5 and 50:50 in the 10.8 mg and 3.6 mg formulation, respectively, that led to a more gradual release of goserelin in the trimonthly formulation compared to the monthly one, thus, maintaining therapeutic drug levels for 3 months [Citation19].

GnRH-a can effectively relieve endometriosis-related pain and can be used alongside hormone add-back therapy for the long-term management of endometriosis, including symptom relief and recurrence prevention [Citation22]. Our study shows that goserelin 10.8 mg is as effective as goserelin 3.6 mg in the control of adenomyosis-related dysmenorrhea, which also applies to the treatment of endometriosis due to their similar hormone dependent nature. However, this needs to be confirmed by specific trials. GnRH-a can also be used for preoperative pretreatment in patients with adenomyosis with excessive uterine volume or severe anemia to facilitate surgery and reduce intraoperative bleeding, and it can be used as postoperative consolidation therapy for conservative surgeries [Citation23–25]. According to our study, trimonthly dosing of goserelin may be a better treatment option for these patients.

Our study has several potential limitations. First, the study design is open and the study length is relatively short. The hypoestrogenic side effects of GnRH-a limit its long-term treatment. In our study, after 12 weeks of treatment, almost half of the patients without conception plans in both groups chose to use LNG-IUS for long-term management. Several patients also used other hormonal therapies to consolidate treatment, such as combined oral contraceptives and progestins. Only a small proportion of patients with a uterine volume > 150 ml continued treatment with goserelin to 6 months. The patients’ different options for long-term management limited our study length, and a longer follow-up period would be required to clarify the long-term effects of GnRH-a after suspension of therapy. Second, the adverse event score is a subjective assessment method and most adverse events cannot be specifically measured. A more appropriate assessment method for measuring the severity of adverse events is lacking. Third, the adverse events are not stratified by age, which could allow for confounding effects due to common symptoms of menopause in older patients. We attempted to avoid this outcome by enrolling only patients without obvious symptoms of perimenopause. Finally, adenomyosis is clinically diagnosed primarily based on ultrasonographic features without histological evidence. Nonetheless, transvaginal ultrasonography has been proven accurate and reliable in diagnosing adenomyosis [Citation26, Citation27].

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that trimonthly administration of goserelin 10.8 mg is equivalent to monthly dosing of goserelin 3.6 mg in clinical efficacy, and is non-inferior in terms of safety and tolerability. Hence, trimonthly goserelin 10.8 mg may be an alternative regimen that is more convenient for patients, potentially helping improve compliance. In addition, the trimonthly formulation is less expensive and effective in reducing patient outpatient visits, which will help reduce patient-related healthcare costs and clinician burden.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bird CC, McElin TW, Manalo-Estrella P. The elusive adenomyosis of the uterus–revisited. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;112(5):1–6.

- Grimbizis GF, Mikos T, Tarlatzis B. Uterus-sparing operative treatment for adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(2):472–487.

- Osada H. Uterine adenomyosis and adenomyoma: the surgical approach. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(3):406–417.

- Zhu L, Chen S, Che X, et al. Comparisons of the efficacy and recurrence of adenomyomectomy for severe uterine diffuse adenomyosis via laparotomy versus laparoscopy: a long-term result in a single institution. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1917–1924.

- Vannuccini S, Luisi S, Tosti C, et al. Role of medical therapy in the management of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(3):398–405.

- Pontis A, D'Alterio MN, Pirarba S, et al. Adenomyosis: a systematic review of medical treatment. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32(9):696–700.

- Kho KA, Chen JS, Halvorson LM. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of adenomyosis. JAMA. 2021;326(2):177–178.

- Masuda N, Iwata H, Rai Y, et al. Monthly versus 3-monthly goserelin acetate treatment in pre-menopausal patients with estrogen receptor-positive early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126(2):443–451.

- Bozzini N, Messina ML, Borsari R, et al. Comparative study of different dosages of goserelin in size reduction of myomatous uteri. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11(4):462–463.

- Cunningham RK, Horrow MM, Smith RJ, et al. Adenomyosis: a sonographic diagnosis. Radiographics. 2018;38(5):1576–1589.

- Van den Bosch T, de Bruijn AM, de Leeuw RA, et al. Sonographic classification and reporting system for diagnosing adenomyosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53(5):576–582.

- Van den Bosch T, Dueholm M, Leone FP, et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe sonographic features of myometrium and uterine masses: a consensus opinion from the morphological uterus sonographic assessment (MUSA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(3):284–298.

- Della Corte L, Barra F, Mercorio A, et al. Tolerability considerations for gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues for endometriosis. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2020;16(9):759–768.

- Cope AG, Ainsworth AJ, Stewart EA. Current and future medical therapies for adenomyosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2020;38(2–03):151–156.

- Lee KH, Kim JK, Lee MA, et al. Relationship between uterine volume and discontinuation of treatment with levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices in patients with adenomyosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294(3):561–566.

- Zhang P, Song K, Li L, et al. Efficacy of combined levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for the treatment of adenomyosis. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22(5):480–483.

- Ji M, Yuan M, Jiao X, et al. A cohort study of the efficacy of the dienogest and the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist in women with adenomyosis and dysmenorrhea. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2022;38(2):164–169.

- Bedaiwy MA, Mousa NA, Casper RF, et al. Aromatase inhibitors prevent the estrogen rise associated with the flare effect of gonadotropins in patients treated with GnRH agonists. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4 Suppl):1574–1577.

- Cockshott ID. Clinical pharmacokinetics of goserelin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;39(1):27–48.

- Dueholm M. Minimally invasive treatment of adenomyosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:119–137.

- Noguchi S, Kim HJ, Jesena A, et al. Phase 3, open-label, randomized study comparing 3-monthly with monthly goserelin in pre-menopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2016;23(5):771–779.

- Bedaiwy MA, Allaire C, Alfaraj S. Long-term medical management of endometriosis with dienogest and with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and add-back hormone therapy. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(3):537–548.

- Chao X, Song X, Wu H, et al. Adjuvant therapy in conservative surgery for adenomyosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;154(1):119–126.

- Wang PH, Liu WM, Fuh JL, et al. Comparison of surgery alone and combined surgical-medical treatment in the management of symptomatic uterine adenomyoma. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):876–885.

- Yu W, Liu G, Liu C, et al. Recurrence-associated factors of laparoscopic adenomyomectomy for severely symptomatic adenomyoma. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(3):3430–3438.

- Abbott JA. Adenomyosis and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB-A)-pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;40:68–81.

- Dason ES, Chan C, Sobel M. Diagnosis and treatment of adenomyosis. CMAJ. 2021;193(7):E242.