Abstract

Objective

To investigate safety and effectiveness of NOMAC-E2 and levonorgestrel-containing COCs (COCLNG) in users over 40.

Methods

In this large, observational study, new usersFootnote1 of NOMAC-E2 and COCLNG were recruited in Europe, Australia, and Latin America and followed-up via questionnaires. Incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) was expressed as incidence rate (IR; events/104 women-years [WY]). Unintended pregnancy was expressed by the Pearl Index (PI; contraceptive failures/100 WY). Mood and weight changes were defined as mean changes in mood score and percentage of body weight.

Results

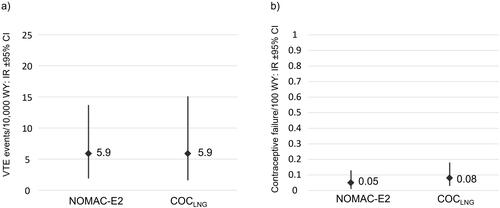

Overall, 7,762 NOMAC-E2 and 6,059 COCLNG users over 40 were followed-up. NOMAC-E2 showed no increased VTE risk compared to COCLNG; confirmed events: 5 NOMAC-E2 (IR 5.9; 95% CI, 1.9–13.7) vs 4 COCLNG (IR 5.9; 95% CI, 1.6–15.1). Unintended pregnancy did not differ substantially between cohorts; confirmed events: 4 NOMAC-E2 (PI 0.05; 95% CI, 0.01–0.13) vs 5 COCLNG (PI 0.08; 95% CI, 0.03–0.18). No differential effect on mood and weight was observed between cohorts.

Conclusions

NOMAC-E2 can be considered a valid alternative to COCLNG in perimenopausal women.

Introduction

Perimenopause is the transitional time around menopause beginning in the years prior to menopause and ending 12 months after the final menstrual period [Citation1]. Women in perimenopause are on average 40 to 50 years old and can experience irregular menstrual cycles, bleeding problems and first onset of menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes and vaginal dryness [Citation2]. During the transition to menopause, the ovarian reserve and fertility decline. However, perimenopausal women can still become pregnant and unintended pregnancy in this age group is associated with increased maternal mortality, spontaneous abortion, fetal anomalies and perinatal mortality [Citation3,Citation4]. Thus, women in perimenopause still require effective contraception.

In addition to their contraceptive effect, combined oral contraceptives (COCs) offer various health benefits that can be particularly relevant for women in perimenopause [Citation5], such as the reduction of irregular cycles, painful or heavy menstrual bleeding [Citation6,Citation7]. Age per se is not a contraindication of COC use, though certain potential risks with the use of COCs increase with age (predominantly the risk of venous thrombosis and of myocardial infarction) [Citation8]. Guidelines thus do not recommend the use of COCs in older women in the presence of other cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. in women over 35 years, smoking more than 15 cigarettes a day) [Citation9] but state that women without contraindications may use COCs for contraception up to the age of 50 [Citation10].

NOMAC-E2 is a fixed dose COC containing 2.5 mg of the progestin nomegestrol acetate and 1.5 mg of 17β-estradiol (a synthetic analogue of endogenous estrogen) and is taken for 24 days followed by 4 days of placebo. At dosages of 1.5 mg/day or more, NOMAC effectively suppresses gonadotropic activity and ovulation in women of reproductive age [Citation11].

Post-authorization safety studies (PASS) investigate the frequency of already known adverse events and possible rare adverse events in a patient population that is typical of real-life users [Citation12]. The PRO-E2 study was conducted as a required PASS in accordance with Article 10a of the European Union (EU) Regulation 726/2004 and was aimed at investigating the cardiovascular and other health risks associated with the use of NOMAC-E2 compared with the use of levonorgestrel-containing COCs (COCLNG) during standard clinical practice. The study results showed that NOMAC-E2 use was not associated with a higher risk of thromboembolic events [Citation14] and showed a statistically significant better effectiveness [Citation13] compared with COCLNG. The mean age of participants in the PRO-E2 study was 30.1 years. To specifically investigate NOMAC-E2 safety and effectiveness in perimenopausal women, we analyzed a PRO-E2 subpopulation of participants over 40 years.

Materials and methods

PRO-E2 was a large, multinational, controlled, prospective, active surveillance study. New users (startersFootnote2 and restartersFootnote3) of NOMAC-E2 and COCLNG were followed for up to 2 years in 12 countries in Europe, Australia, and Latin America. The main clinical outcome of interest was venous thromboembolism (VTE), specifically deep venous thrombosis (DVT) of the lower extremities and pulmonary embolism (PE) in women without pre-defined risk factors at study entry (i.e. pregnant within 3 months of treatment initiation, a history of cancer/chemotherapy or an increased genetic risk of VTEFootnote4). Secondary objectives included unintended pregnancy, weight change and mood change. Ethical approval was obtained as required by local law and an independent Safety Monitoring and Advisory Council (SMAC) monitored the study.

The PRO-E2 study methodology was described in detail previously [Citation13,Citation14]. Briefly, women were recruited by health care professionals (HCPs) during routine clinical practice. All women newly prescribed an eligible COCFootnote5 could participate if they had not used a COC in the past 2 months, signed an informed consent form and completed a baseline questionnaire in the local language. Outcomes of interest were captured by direct contact with the study participants and validated via attending physicians. VTE outcomes were subjected to blinded adjudication, as described previously [Citation14].

Baseline survey and follow-up

Women completed a baseline questionnaire to capture demographic data (age, weight, height), reason(s) for their COC prescription (contraceptive reasons only, contraceptive and non-contraceptive reasons, non-contraception reasons only), gynecological history, personal and family medical history, concomitant medication, exposure to hormonal contraceptives and lifestyle factors. Follow-up questionnaires were sent to women via mail or e-mail at 6, 12, and 24 months after study inclusion to capture data on contraceptive use, pregnancy, and the occurrence of the outcomes of interest.

Evaluation

In the PRO-E2 study, a non-inferiority design with an upper limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI) on a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.5 was used for assessing the risk of VTE. Time-to-event analyses of VTE and unintended pregnancy were carried out for the overall cohort based on Cox regression analyses to yield crude and adjusted HR for NOMAC-E2 vs. COCLNG [Citation13,Citation14].

As the number of confirmed events in the sub-population over 40 years was too low for allowing a meaningful time-to-event analysis, only incidence rates (IR) are presented in this manuscript. The incidence of VTE is expressed as IR including 95% CI based on the occurrence of new cases per 104 women-years (WY) and the incidence of unintended pregnancy is measured by the Pearl Index (including 95% CI), which calculates the number of contraceptive failures per 100 WY of exposure.

Pregnancy events were assigned to the exposure at the time of conception (which may have differed from the COC prescribed at study entry). Only first confirmedFootnote6 pregnancies during study participation were included. Confirmed pregnancies were included regardless of the reasons for contraceptive use (e.g. contraceptive or non-contraceptive reasons) reported by study participants at baselineFootnote7.

The mean change in percentage of body weight was calculated by comparing the body weight at each follow-up time point to the body weight at baseline. Baseline and follow-up questionnaires contained mood-related questions. The responses to these questions were transformed into a mood score scaled from 0 to 100 (with a higher score indicating a better mood) and score changes from baseline to each follow-up time point were compared. Changes in body weight and mood score were calculated for constant users (i.e. women who continued using their baseline prescription through follow-up).

Results

Out of 91,313 women who began using an eligible COC at baseline, 44,559 women were initially prescribed with NOMAC-E2 and 46,754 with COCLNG. Of these, 7,762 NOMAC-E2 users and 6,059 COCLNG users were over 40 years old. shows the regional distribution of study participants in this age group. Most participants over 40 in both cohorts came from Russia (40.7% and 46.3% in the NOMAC-E2 and COCLNG cohort, respectively) and Italy (35.0% and 27.3% in the NOMAC-E2 and COCLNG cohort, respectively).

Table 1. Regional distribution (country) of women over 40 years at study entry by user cohort.

Baseline characteristics

There were no substantial differences between the cohorts with respect to most baseline characteristics (). Mean weight (NOMAC-E2: 66.3 kg; COCLNG: 66.9 kg) and mean body mass index (BMI, NOMAC-E2: 24.4; COCLNG: 24.7) were very similar in both cohorts. A slightly lower proportion of NOMAC-E2 users reported ever having been pregnant (NOMAC-E2: 85.6%; COCLNG: 90.0%). Cohorts were very similar in relation to cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, high blood pressure, personal and family history of cardiovascular disease) as well.

Table 2. Selected baseline characteristics of women over 40 years by user cohort.

At study entry, 43.5% of NOMAC-E2 users and 47.9% of COCLNG users reported taking the prescribed COC for contraceptive reasons only. Contraceptive and/or non-contraceptive reasons were reported by 54.4% and 50.4% of NOMAC-E2 and COCLNG users, respectively. The most frequent non-contraceptive reasons were cycle regulation (NOMAC-E2 43.5% vs COCLNG 46.1%), heavy and/or prolonged menstrual bleeding regulation (NOMAC-E2 36.1% vs COCLNG 32.2%) and painful menstrual bleeding (NOMAC-E2 22.9% vs COCLNG 22.4%).

NOMAC-E2 users reported having a slightly higher level of education, with 42.7% having had more than a university entrance level education compared to 37.3% of COCLNG users.

Only a minor proportion of all COC users reported suffering from depression requiring treatment (3.8% of NOMAC-E2 users and 3.2% of COCLNG users).

Venous thromboembolism

The primary outcome of PRO-E2 was VTE (DVT of the lower extremities and PE). Over the course of 8,525 WY and 6,764 WY of follow-up, 5 and 4 confirmed VTEs were observed in women over 40 from the NOMAC-E2 and COCLNG cohorts, respectively. The VTE incidence rates per 10,000 WY by user cohort were very similar in both cohorts (5.9/10,000 WY; 95% CI, 1.9–13.7 for NOMAC-E2 and 5.9/10,000 WY; 95% CI, 1.6–15.1 for COCLNG), as shown in .

Unintended pregnancy

As expected in this age category, unintended pregnancy rates were low and did not differ substantially between cohorts. Overall, there were 4 confirmed unintended pregnancies in NOMAC-E2 users (0.05 per 100 WY; 95% CI, 0.01–0.13) and 5 in COCLNG users (0.08 per 100 WY; 95% CI, 0.03–0.18) ().

Effects on weight and mood

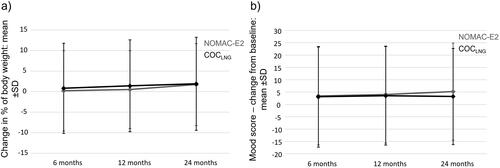

Constant users of NOMAC-E2 had a mean change in body weight of 0.2% (SD ±9.77), 0.5% (SD ±9.47), and 1.7% (SD ±9.97) at 6, 12 and 24 months after study entry, respectively. Constant users of COCLNG had a mean body weight change in 0.8% (SD ±10.97), 1.4% (SD ±11.16) and 1.9% (SD ±11.33) at 6, 12 and 24 months after study entry, respectively (). Notably, the standard deviations were large and the marginal trend of body weight increase was in the same order of magnitude as the average human weight gain with aging [Citation15].

Figure 2. (a) Change in weight after study entry by user cohort and (b) Change in mood score after study entry by user cohort.

Mean changes in mood score did not differ substantially in both cohorts (). Changes from baseline to follow-up were only minor and standard deviations were large; NOMAC-E2: 3.4 (SD ±19.80), 4.0 (SD ±19.64), and 5.2 (SD ±19.68) and COCLNG: 3.1 (SD ±20.38), 3.5 (SD ±19.95), and 3.2 (SD ±19.51) score change from baseline to 6-, 12- and 24-months follow-up, respectively.

Discussion

Women transitioning to menopause are still potentially fertile and require effective contraception, especially because unintended pregnancy in this age group is associated with higher risks. At the same time perimenopause is a peak stage in life for menstrual dysfunction and a time when menopausal symptoms may commence [Citation16]. All these factors may influence contraceptive choice.

This subpopulation analysis of the PRO-E2 study showed that around half of the participating women over 40 (slightly more in the NOMAC-E2 cohort) reported to use their COC for contraceptive and/or non-contraceptive reasons. The most frequent non-contraceptive reasons comprised cycle regulation, heavy and/or prolonged menstrual bleeding regulation and painful menstrual bleeding. This indicates that women in this age group might seek for a contraceptive that is both effective and beneficial for the management of perimenopausal symptoms. Approximately 90% of women experience changes in their menstrual patterns for 4 to 8 years before complete menopause is reached [Citation5]. A multicenter, randomized, double-masked study showed that, as long as other underlying causes are eliminated, menstrual cycles can be effectively controlled by using COCs in 80% of cases [Citation6]. Another randomized trial has shown that COCs can reduce the amount of menstrual bleeding by approximately 40% [Citation7].

Baseline characteristics of women over 40 in the PRO-E2 study with regards to BMI, cardiovascular risk factors, gynecological and medical history did not differ substantially between cohorts, apart from minor differences in relation to parity and educational level.

Although the overall number of VTE and unintended pregnancy events was low in both cohorts, the presented subpopulation analysis in women over 40 indicated no substantial differences between women using NOMAC-E2 or COCLNG in VTE risk and contraceptive effectiveness. Furthermore, we observed no differential effect on mood or weight changes between cohorts. This might be particularly relevant for women in this age group, as the hormonal changes in perimenopause often come along with mood swings or weight gain. The results sustain the possible use of a pill with a similar VTE risk compared to pills with LNG but having a better metabolic profile, as was previously shown [Citation17–19].

Study-specific limitations have been described previously [Citation13,Citation14]. Briefly, besides the usual limitations of observational research [Citation20], the PRO-E2 study had a higher loss to follow-up (LTFU) rate than in previous similar studies. This resulted in part from implementing the GDPR in May 2018 and emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic toward the end of the study. Another limitation was that a direct comparison with a COCLNG, which has the same 24/4 day regimen as NOMAC-E2, was not possible, as such a preparation is not currently on the market [Citation21]. Mood outcome was derived solely from self-reported information given by participants in response to specific questions as part of the baseline and follow-up questionnaires and was not further validated by clinical records or contact with treating physicians.

The study benefited from several strengths. Only new users (first-ever users of an eligible COC or restarting use after a break of at least 2 months) participated; selection bias introduced by the inclusion of prevalent users was eliminated. Relying upon patient reports ensured that almost all outcomes of interest were captured. The study design also enabled the capture of important potential confounders such as age, BMI, gravidity, and education level. Furthermore, it captured precise information on COC use (specific COCs, stopping and switching patterns) and women contributed WY to several (sub-)cohorts depending upon their real-life use. Study participants were recruited by a broad range of HCPs (e.g. gynecologists, general practitioners, midwives) and all eligible new users could participate (e.g. there were no medical inclusion or exclusion criteria). Therefore, the generalizability of the results to the general population is high.

Conclusions

NOMAC-E2 compares to COCLNG in perimenopausal women in clinical practice with regards to VTE risk, contraceptive effectiveness and effects on mood and body weight and can thus be considered a valid alternative to COCLNG, which is often recommended by guidelines as first line treatment. In conclusion, both COCs are indicated and proved to be safe contraceptives in perimenopausal women.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable scientific contribution of the SMAC. Their critical review of the data and challenging discussions substantially enhanced the overall quality of the study and the interpretation of the results. SMAC members included David Grimes, Michael Lewis, Robert Reid, Samuel ShapiroFootnote8, Carolyn Westhoff, Ulrich Winkler and Stephanie Teal. Advisors to the SMAC included Jochen Albrecht and Fritz von WeizsäckerFootnote9. The authors would also like to thank the colleagues in the local field organizations who conducted the day-to-day field work. Their remarkable dedication and flexibility despite the challenging circumstances caused by the pandemic ensured the success of the study. The authors would also like to thank the ZEG Berlin staff members (statisticians, data managers, event validation staff, and medical advisers) whose contribution to the study was invaluable.

Disclosure statement

SVS, KB, AB, CF, and KH are full-time employees at ZEG Berlin. FF has received honoraria from Bayer, Gedeon Richter, EffiK, MSD, Pfizer and Theramex for educational or advisory activities. JC has received honoraria from Bayer, Gedeon Richter, Lilly, MSD, and Theramex for educational or advisory activities. CK has received honoraria for educational or advisory activities from Theramex, Theva, Exeltis, Besins, Merck, Organon, Henry Schein, Gedeon Richter, Jenapharm, Bayer, Serono.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 First-ever users of an eligible COC or restarting with an eligible COC (same COC as before or a new COC) after a break of at least 2 months.

2 First-ever users of an eligible COC

3 Restarting with an eligible COC (same COC as before or a new COC) after a break of at least 2 months

4 This definition of the primary outcome and the exclusion of women with pre-defined risk factors conformed with requirements of the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee of the EMA for this study.

5 1) NOMAC-E2, 2) COCLNG monophasic preparation containing 20-30mcg of ethinylestradiol, 3) COCLNG multiphasic preparation containing up to 40mcg of ethinylestradiol. LNG concentrations ranged from 90 to 150 mcg depending on COC formulation.

6 If there was ambiguity concerning the date of conception or COC use, the woman and/or her HCP were contacted for clarification. The consent form included permission to contact any treating physician to follow up on specific outcomes.

7 Study participants reported their reason(s) for COC use only at study entry; their reason(s) for use may have changed during follow-up (e.g. a woman who began using a COC for contraceptive only reasons may have experienced a relationship change and continued using the COC for non-contraceptive reasons).

8 Died 19 April 2016.

9 Died 19 November 2019.

References

- Harlow S D, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause. 2012;19(4):1–5.

- Santoro N. Perimenopause: from research to practice. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(4):332–339.

- Shaaban MM. The perimenopause and contraception. Maturitas. 1996;23(2):181–192.

- Kailas NA, Sifakis S, Koumantakis E. Contraception during perimenopause. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2005;10(1):19–25.

- Cho MK. Use of combined oral contraceptives in perimenopausal women. Chonnam Med J. 2018;54(3):153–158.

- Davis A, Godwin A, Lippman J, et al. Triphasic norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol for treating dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(6):913–920.

- Fraser IS, McCarron G. Randomized trial of 2 hormonal and 2 prostaglandin-inhibiting agents in women with a complaint of menorrhagia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;31(1):66–70.

- Mendoza N, Soto E, Sánchez-Borrego R. Do women aged over 40 need different counseling on combined hormonal contraception? Maturitas. 2016;87:79–83.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use. 2016 (July 29, 2016).

- Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. FSRH Guideline Contraception for women aged over 40 years. August 2017. (Amended September 2019).

- Ruan X, Seeger H, Mueck AO. The pharmacology of nomegestrol acetate. Maturitas. 2012;71(4):345–353.

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) – Module VIII – Post-authorisation safety studies (Rev. 3). 2017.

- Reed S, Koro C, DiBello J, et al. Unintended pregnancy in users of nomegestrol acetate and 17β-oestradiol (NOMAC-E2) compared with levonorgestrel-containing combined oral contraceptives: final results from the PRO-E2 study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021;26(6):447–453.

- Reed S, Koro C, DiBello J, et al. Prospective controlled cohort study on the safety of a monophasic oral contraceptive containing nomegestrol acetate (2.5mg) and 17β-oestradiol (1.5mg) (PRO-E2 study): risk of venous and arterial thromboembolism. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021;26(6):439–446.

- Arner P, Bernard S, Appelsved L, et al. Adipose lipid turnover and long-term changes in body weight. Nat Med. 2019;25(9):1385–1389.

- Gebbie A. Contraception in the perimenopause. J Br Menopause Soc. 2003;9(3):123–128.

- Klipping C, Duijkers I, Trummer D, et al. Suppression of ovarian activity with a drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive in a 24/4 regimen. Contraception. 2008;78(1):16–25.

- Junge W, Mellinger U, Parke S, et al. Metabolic and haemostatic effects of estradiol valerate/dienogest, a novel oral contraceptive: a randomized, open-label, single-Centre study. Clin Drug Investig. 2011;31(8):573–584.

- Fruzzetti F, Trémollieres F, Bitzer J. An overview of the development of combined oral contraceptives containing estradiol: focus on estradiol valerate/dienogest. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28(5):400–408.

- Susser M. What is a cause and how do we know one? A grammar for pragmatic epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133(7):635–648.

- Read CM. New regimens with combined oral contraceptive pills–moving away from traditional 21/7 cycles. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2010;15 Suppl 2: s 32–41.