Abstract

Background

Endometriosis has been reported to be associated with metabolism-related diseases, such as hypercholesterolemia and diabetes, while no studies have reported the association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome.

Objective

This study aims to explore the association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome. Also, the association between endometriosis and single metabolic syndrome indicator was explored.

Methods

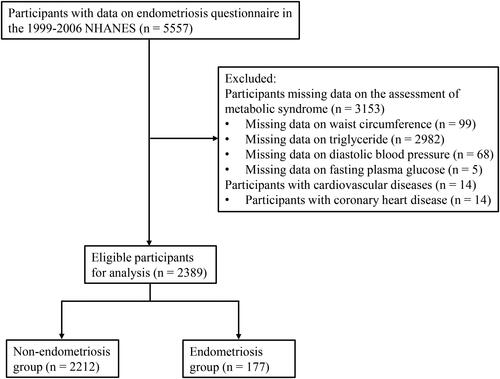

This was a cross-sectional study based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). A total of 2389 participants were finally included for analysis, with 2212 in the non-endometriosis group and 177 in the endometriosis group. Association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome was explored using multivariate logistic regression analysis, with results shown as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Association between endometriosis and single metabolic syndrome indicator was explored using multivariate liner regression analysis.

Results

After adjusting age, race, education level, family poverty to income ratio (PIR), smoking, age at menarche, gravidity, menopause, female hormones use, and dyslipidemia drug use, endometriosis was associated with the higher odds of metabolic syndrome (OR = 1.55, 95%CI: 1.01–2.35). Further adjusting hysterectomy or oophorectomy, we found the similar association despite no statistical significance (OR = 1.47, 95%CI: 0.96–2.25). Moreover, we found endometriosis was associated with the high level of triglyceride (TG) (β = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.06–0.70).

Conclusions

Our study found the association between endometriosis and metabolic conditions, indicating that metabolic conditions of endometriosis women should be focused, and monitoring the blood lipid levels may be significant in decreasing the risk of metabolic syndrome.

Introduction

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrium-like tissues outside the uterine cavity, affects 5–10% of women of reproductive age, and can cause severe dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility [Citation1,Citation2]. Endometriosis is an oestrogen-dependent inflammatory disease, and the immune response may induce metabolic disorders [Citation1,Citation3].

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of metabolic disorders characterized by central obesity, insulin resistance, blood pressure elevation, and atherogenic dyslipidemia [Citation4]. Evidence has showed that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome is 34.3% in women in the United States [Citation5]. Metabolic syndrome is associated with an increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), is one of the main reasons for mortality worldwide, and has been one of the important issues affecting public health [Citation4,Citation5]. Several studies have reported that endometriosis may have a relationship with metabolism-related diseases [Citation6,Citation7]. In endometriosis patients, levels of inflammatory markers are found to be elevated [Citation8]. Evidence has showed that inflammation could affect lipid metabolism, increasing the serum level of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) [Citation9]. Moreover, chronic inflammation increases the blood pressure, and vascular changes caused by hypertension likewise elevate the inflammatory mechanism [Citation10]. A study has showed that the relative risk of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension was increased in women with laparoscopically-confirmed endometriosis [Citation6]. Farland et al. have found that endometriosis was associated with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes [Citation7]. However, there were no studies to explore the association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome.

Herein, we performed a cross-sectional study to explore the association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data. Also, the association between endometriosis and single metabolic syndrome indicator was explored. Our study may be contributed to expand the knowledge in the management of endometriosis and metabolic conditions.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was a cross-sectional study, and data were extracted from NHANES, which was designed to evaluate American adults’ and children’s health and nutritional status [Citation11]. The unique of the survey was the combination of interviews and physical examinations. The survey was performed in a repeated 2-year cycle with a complex multistage probability sampling design. At the time of survey, written informed consent has been obtained from all participants, and procedures and protocols were reviewed and approved annually by the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board [Citation12]. We used 1999–2006 data (1999–2000, 2001–2002, 2003–2004, 2005–2006) because these four cycles reported data on endometriosis. This study was determined exempt from review by Institutional Review Board of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine because NHANES data were publicly available and de-identifiable.

Study population

Participants with assessment of endometriosis were included in this study. Participants missing data on metabolic syndrome or participants with cardiovascular diseases were excluded from this study.

Regarding the diagnosis of endometriosis, participants who gave positive answer for the question ‘Told by doctor had endometriosis?’ were classified as endometriosis patients [Citation13].

Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III, and participants met three or more of the following criteria were diagnosed as metabolic syndrome: (1) waist circumference (WC) > 88 cm; (2) systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 85 mm Hg or taking hypertension medications; (3) triglyceride (TG) level ≥ 150 mg/dL (1.70 mmol/L); (4) high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) < 50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L), or (5) fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level ≥ 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or taking diabetes medications [Citation5].

Data extraction

Data were extracted based on four aspects (baseline characteristics, physical examination, laboratory values, and dietary intake).

Baseline characteristics included age, race, educational level, marital status, family poverty to income ratio (PIR), drinking status, smoking status, age at menarche, gravidity, menopausal status, hysterectomy or oophorectomy, female hormones use, pregnancy status, and medicine use (diabetes drug use, dyslipidemia drug use, hypertension drug use). Age was divided into ≤ 40 years and > 40 years [Citation14]. For age at menarche, participants were asked ‘how old were you when first menstrual period occurred?’ Consistent with previous study [Citation15], they were categorized into ≤ 11 years, 12–13 years, and ≥ 14 years group. Participants who gave positive answer for the question ‘Had a hysterectomy?’ or ‘Had at least one ovary removed?’ were classified as hysterectomy or oophorectomy.

Physical examination included WC, SBP, and DBP.

Laboratory values included TG, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), HDL-C, and FPG. TG was measured enzymatically in serum or plasma using a series of coupled reactions [Citation16]. HDL-C was measured using a heparin-manganese (Mn) precipitation method or a direct immunoassay technique [Citation17]. LDL-C was calculated according to the Friedewald calculation: LDL-C = total cholesterol - HDL-C - TG/5 [Citation16]. FPG was measured using a hexokinase method [Citation18].

Dietary intake included total energy. Total energy intake was assessed via dietary interview. Dietary intake data were used to estimate the types and amounts of foods and beverages consumed in the past 24 h (midnight to midnight), and to estimate intakes of energy from those foods and beverages [Citation19].

Statistical analysis

To account for complex sampling design, data in this study were weighted using appropriate sample weights provided by NHANES. Measurement data were expressed as mean (standard error) (S.E), and differences between two groups were compared using t test. Counting data were expressed as number and percentage [n (%)], and differences between groups were compared using chi-squared test. Missing data were processed using multiple imputation. To explore the association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome, multivariate logistic regression analysis was used, and results were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to select covariates. To explore the association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome indicators, multivariate liner regression analysis was used. Univariate liner regression analysis was used to select covariates for single metabolic syndrome indicator. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and p < .05 was considered to be statistical significance.

Results

Characteristics of study population

A total of 5557 participants with data on endometriosis questionnaire in the 1999–2006 NHANES were extracted. Of these, 3,153 participants missing data on the assessment of metabolic syndrome [missing data on WC (n = 99), TG (n = 2982), DBP (n = 68), FPG (n = 5)] and 14 participants with cardiovascular diseases [with coronary heart disease (n = 14)] were excluded. Finally, 2389 participants were included for analysis, with 177 in the endometriosis group and 2212 in the non-endometriosis group (). There was statistical significance in age, race, marital status, smoking, menopause, hysterectomy or oophorectomy, female hormones use, WC, SBP, DBP, TG, and metabolic syndrome between endometriosis group and non-endometriosis group ().

Table 1. Characteristics of included participants.

Association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome

Supplementary Table S1 shows that age, race, education level, family PIR, smoking, age at menarche, gravidity, menopause, hysterectomy or oophorectomy, female hormones use, and dyslipidemia drug use were identified as confounders. In the unadjusted model, we found that participants with endometriosis had higher odds of metabolic syndrome than those without endometriosis (OR = 1.55, 95%CI: 1.06–2.25). After adjusting age, race, education level, family PIR, smoking, age at menarche, gravidity, menopause, female hormones use, and dyslipidemia drug, similar result was observed (OR = 1.55, 95%CI: 1.01–2.35). Further adjusting hysterectomy or oophorectomy, we found no statistical significance between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome (OR = 1.47, 95%CI: 0.96–2.25) ().

Table 2. Association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome.

Association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome indicators

Supplementary Table S2 shows the potential confounders for single metabolic syndrome indicator. Hysterectomy or oophorectomy was further adjusted based on the identified confounders. In the unadjusted model, endometriosis was found to be associated with WC, SBP, DBP, and TG (all p < .05). After adjusting the potential confounders, statistical significance was found between endometriosis and TG (β = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.08–0.76). Further adjusting hysterectomy or oophorectomy, the results were similar (TG: β = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.06–0.70) ().

Table 3. Association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome indicators.

Discussion

In this study, we found that endometriosis was significantly associated with the high odds of metabolic syndrome before adjusting hysterectomy or oophorectomy. After adjusting hysterectomy or oophorectomy, we found the similar association although there was no statistical significance. Moreover, we found that endometriosis was associated with the high level of TG whether adjusting hysterectomy or oophorectomy or not.

The prevalence of endometriosis is high and has been one of the critical health problems in women [Citation1]. Endometriosis has been found to be associated with some metabolism-related diseases [Citation6,Citation7,Citation20]. Farland et al. have reported the higher risk of type 2 diabetes in endometriosis women without obesity, never experiencing infertility, or never experiencing gestational diabetes mellitus [Citation7]. Rossi et al. have found an association between endometriosis and WC [Citation20]. A prospective cohort study has reported that endometriosis women had a higher risk of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension than non-endometriosis women [Citation6]. Metabolic syndrome is characterized by several metabolic abnormalities, such as central obesity, hypertension, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance [Citation4]. In this study, we found the significant association between endometriosis and markers of metabolic syndrome. The possible mechanism explaining for this was inflammatory response. Our study found the level of inflammatory marker was higher in the endometriosis women although no statistical difference was found (Supplementary Table S3). Many studies have reported that inflammatory factors, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP), were elevated in endometriosis women [Citation21–23]. The inflammation may contribute to the development of metabolic syndrome [Citation4]. IL-6 level was shown to be elevated with insulin resistance and decreased with obesity, and to regulate fat and glucose metabolism [Citation24,Citation25]. Also, IL-6 increased the production of CRP, which was demonstrated to be strongly correlated with thrombosis and atherosclerosis [Citation26]. The production of TNFα was also proportional to the mass of adipose tissue and associated with insulin resistance, both of which were major features of metabolic syndrome [Citation4].

After adjusting hysterectomy or oophorectomy, endometriosis was associated with higher odds of metabolic syndrome but no statistical significance was found, indicating that surgical treatments play an important role in the association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome. Women with endometriosis may undergo surgeries, such as hysterectomy or oophorectomy, to alleviate symptoms [Citation1]. Some studies have suggested that hysterectomy or oophorectomy increased the risk of metabolism-related diseases in patients with gynecological diseases (including endometriosis) [Citation27,Citation28], which may weaken the relationship between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome. Future studies into the relationship between surgical treatments for endometriosis and risk of metabolic syndrome may further elucidate the mechanisms.

Our study found the association between endometriosis and the high level of TG. Crook et al. have reported that TG level was higher in women with endometriosis than those without endometriosis [Citation29]. A previous study has showed that TG involved in the development and progression of atherosclerosis [Citation30], and women with endometriosis had elevated arterial stiffness than controls [Citation31]. Considering these interactions and complexities, clinicians should focus on endometriosis women’s lipid status. We also found the marginal significant association between endometriosis and WC. Rossi et al. have found that endometriosis was significantly associated with WC in the adult women [Citation20]. In the future, the association between endometriosis and WC needed to be further explored.

There are some strengths in this study. First, our study explores the association between endometriosis and metabolic syndrome, and the findings may be helpful for the management of metabolic syndrome in endometriosis patients. Second, our sample size is from the NHANES database, which adopts the complex multistage probability sampling design and includes a nationally representative sample. Several limitations exist in the study. First, this is a cross-sectional study that cannot infer causal relationship. Second, endometriosis is determined by self-reported physician diagnosis during the survey. Surgery is the gold standard for the diagnosis of this disease; however, it is unable for us to specify whether the cases of endometriosis have been diagnosed surgically due to the limitation of the database, which may lead to selection bias. Third, NHANES is a population-based program in the United States. Our findings should be further verified in the participants from other countries and regions.

Conclusion

This study found that endometriosis was associated with metabolic conditions. Our findings suggested that the metabolic conditions of endometriosis women should be focused. Monitoring the blood lipid levels of endometriosis women may be significant in decreasing the risk of metabolic syndrome. In the future, prospective studies are needed to elucidate the effect of endometriosis on the metabolic syndrome.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (37 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in this study are available in the NHANES database, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM, Flores VA. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet. 2021;397(10276):1–6.

- Allaire C, Bedaiwy MA, Yong PJ. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. CMAJ. 2023;195(10):e363–e371.

- Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860–867.

- Fahed G, Aoun L, Bou Zerdan M, et al. Metabolic syndrome: updates on pathophysiology and management in 2021. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):786.

- Hirode G, Wong RJ. Trends in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2011–2016. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2526–2528.

- Mu F, Rich-Edwards J, Rimm EB, et al. Association between endometriosis and hypercholesterolemia or hypertension. Hypertension. 2017;70(1):59–65.

- Farland LV, Degnan WJ, Harris HR, et al. A prospective study of endometriosis and risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2021;64(3):552–560.

- Mu F, Harris HR, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. A prospective study of inflammatory markers and risk of endometriosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(3):515–522.

- Melo AS, Rosa-e-Silva JC, Rosa-e-Silva AC, et al. Unfavorable lipid profile in women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(7):2433–2436.

- Guzik TJ, Touyz RM. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and vascular aging in hypertension. Hypertension. 2017;70(4):660–667.

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [cited 2023 Jun 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NCHS Ethics Review Board (ERB) Approval. [cited 2023 Jun 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm.

- Hu PW, Yang BR, Zhang XL, et al. The association between dietary inflammatory index with endometriosis: NHANES 2001–2006. PLoS One. 2023;18(4):e0283216.

- Ervin RB. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults 20 years of age and over, by sex, age, race and ethnicity, and body mass index: United States, 2003–2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;5(13):1–7.

- Shen Y, Xiao H, Hu H. Racial/ethnic differences in age at menarche and lifetime nonmedical marijuana use: results from the NHANES 2005–2016. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(2):448–453.

- Cholesterol-LDL & Triglycerides (LAB13AM). [cited 2023 Jun 30]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/1999-2000/LAB13AM.htm.

- Cholesterol-Total & HDL (Lab13) [cited 2023 Jun 30]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/1999-2000/LAB13.htm.

- Plasma Fasting Glucose, Serum C-peptide & Insulin (LAB10AM). [cited 2023 Jun 30]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/1999-2000/LAB10AM.htm.

- Dietary Interview-Total Nutrient Intakes (DRXTOT_B). [cited 2023 Jun 30]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2001-2002/DRXTOT_B.htm.

- Rossi HR, Nedelec R, Jarvelin MR, et al. Body size during adulthood, but not in childhood, associates with endometriosis, specifically in the peritoneal subtype-population-based life-course data from birth to late fertile age. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(7):1248–1257.

- Li S, Fu X, Wu T, et al. Role of interleukin-6 and its receptor in endometriosis. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:3801–3807.

- Aksak T, Gümürdülü D, Çetin MT, et al. Expression of monocyte chemotactic protein 2 and tumor necrosis factor alpha in human normal endometrium and endometriotic tissues. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50(5):101971.

- Gleason JL, Thoma ME, Zukerman Willinger N, et al. Endometriosis and uterine fibroids and their associations with elevated C-reactive protein and leukocyte telomere length among a representative sample of U.S. women: data from the national health and nutrition examination survey, 1999–2002. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2022;31(7):1020–1028.

- Rehman K, Akash MSH, Liaqat A, et al. Role of interleukin-6 in development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2017;27(3):229–236.

- Méndez-García LA, Cid-Soto M, Aguayo-Guerrero JA, et al. Low serum interleukin-6 is a differential marker of obesity-related metabolic dysfunction in women and men. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2020;40(3):131–138.

- Badimon L, Peña E, Arderiu G, et al. C-reactive protein in atherothrombosis and angiogenesis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:430.

- Madika AL, MacDonald CJ, Gelot A, et al. Hysterectomy, non-malignant gynecological diseases, and the risk of incident hypertension: the E3N prospective cohort. Maturitas. 2021;150:22–29.

- Chiang CH, Chen W, Tsai IJ, et al. Diabetes mellitus risk after hysterectomy: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(4):e24468.

- Crook D, Howell R, Sidhu M, et al. Elevated serum lipoprotein(a) levels in young women with endometriosis. Metabolism. 1997;46(7):735–739.

- Generoso G, Janovsky C, Bittencourt MS. Triglycerides and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in the development and progression of atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019;26(2):109–116.

- Kilic D, Guler T, Sevgican CI, et al. Association between endometriosis and increased arterial stiffness. Kardiol Pol. 2021;79(1):58–65.