Abstract

Introduction

Female sexual interest and arousal disorder (FSIAD) is the most prevalent female sexual dysfunction in the postmenopause.

Objective

The aim of this review is to provide a summary of the currently available evidence on the use of testosterone in the treatment of FSIAD in postmenopausal women.

Methods

A narrative review on the topic was performed. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews and meta-analysis were considered. 123 articles were screened, 105 of them assessed for eligibility, and finally 9 were included in qualitative synthesis following the PRISMA declaration.

Results

Current evidence recommends, with moderate therapeutic benefit, the use of systemic transdermal testosterone within the premenopausal physiological range in postmenopausal women with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD), the previous entity for low desire dysfunction, not primarily related to modifiable factors or comorbidities such as relationship or mental health problems. The available evidence is based on studies with heterogeneity on their design (different testosterone doses, routes of administration, testosterone use in combination and alone, sexual instruments of measurement). There is no data indicating severe short-term adverse effects, although long-term safety data is lacking.

Conclusions

Despite having testosterone as a valuable tool, therapeutic strategies are lacking in the pharmacological field of HSDD/FSIAD. Neuroimaging studies could provide valuable information regarding the sexual desire substrate and suggest the potential application of already approved drugs for women with a good safety profile. The use of validated instruments for HSDD in postmenopausal women, considering the level of distress, is necessary to be able to draw robust conclusions on the evaluated treatments.

Introduction

Menopause, characterized by the cessation in the ovarian function, is associated with physiological, psychological and cultural changes that influence sexuality in a byopsychosocial way. In this way, hormonal changes may be significant contributors to potentially emerging sexual dysfunctions (e.g. by means of diminished vaginal lubrication, because estrogens and testosterone are believed to promote the expression of nitric oxide synthase [Citation1]), but nonhormonal factors, such as own and partner’s health status, body-image concerns, loss of sexual self-confidence or performance anxiety, may also play a major role on its genesis in this vital period [Citation2].

From a physiological point of view, female hormonal environment, constituted by androgens and estrogens, modulates cortical coordinating and controlling areas that interpret what sensations are perceived as sexual and issue appropriate commands to the rest of the nervous system [Citation3]. In addition, sex hormones affect the threshold of sensitivity of both non-genital and genital organs and of hypothalamic-limbic structures, in which they elicit conscious perception and pleasurable reactions by influencing the release of specific neurotransmitters and neuromodulators [Citation3].

The importance of adequate estrogen levels, mainly estradiol, in preserving vaginal receptivity is well-known, as well as its permissive role in mental awareness and sexual receptivity [Citation4]. Nevertheless, androgens, mainly testosterone, have a 3–4 fold higher concentration in the female brain during reproductive years than estradiol and prime the brain to be selectively responsive to sexual incentives inducing a neurochemical state favorable to sexual response [Citation5]. Therefore, they contribute to initiation of sexual activity and permission for sexual behavior, and also directly modulate vaginal and clitoral physiology influencing genital engorgement and sensation and, cooperating with estrogens, enhance vaginal lubrication [Citation4]. Its mechanism of action is thought to involve both androgenic pathways and the aromatization of testosterone to estradiol [Citation6].

Female Sexual Interest and Arousal Disorder (FSIAD) is the most prevalent female sexual dysfunction in the postmenopause.

This entity was first described in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, on which, on the basis of the available literature, sexual desire and arousal disorders were combined into a single diagnosis [Citation7]. Many of the trials on the topic, however, have used the DSM-4 classification, on which Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD) was classified as part of the sexual desire disorders category and defined by the absence or significant reduction of sexual thoughts or fantasies and/or desire for and receptivity to sexual activity that causes personal distress [Citation8]. Such indicators need to have persisted through time (minimum 6 months) and cannot be attributed to a mental disease, drug effect, other health condition or deterioration of the partner relationship.

A cross-sectional survey conducted in women from the United States and Europe, known as the Women’s International Study of Health and Sexuality, assessed the prevalence of HSDD [Citation9]. In the European sample, among women aged 50–70, the prevalence was 9% in women with natural menopause and 12% in women with surgical menopause, being most frequently presented on its generalized and acquired form. The proportion of women with low desire increased with age, while the proportion of women distressed by low desire decreased with age. These data has to be kept in mind when proposing treatments because if a woman does not report distress with her decreased or loss of sexual desire, she will not meet the criteria for the condition of HSDD [Citation10].

When HSDD is present in postmenopausal women, after excluding other causes such as mood disorders, relationship problems and systemic illness, testosterone constitutes an evidence-based therapy and, thus, is included in clinical practice guidelines [Citation11]. Systemic testosterone has proven its effects on clitoral hemodynamics in women with sexual dysfunction [Citation12] and, in animal model, sexual behavior facilitation has been attributed to its direct interaction with the androgen receptor [Citation13]. Despite this biological evidence, barriers from both healthcare professionals and patients regarding androgen therapy still exist.

The aim of this review is to provide a summary of the currently available evidence on the use of testosterone in the treatment of FSIAD in postmenopausal women.

Matherial and methods

A narrative review of studies involving systemic testosterone (ST) for the treatment of FSIAD in the postmenopause was carried out using Pubmed, Embase and Medline. To identify all of the articles assessing ST in adult ages, the following search strategy was designed: ‘Systemic testosterone’ ([All Fields] and [MeSH Terms]) or ‘testosterone’ ([All Fields] and [MeSH Terms]) or ‘androgen use’ ([All Fields] and [MeSH Terms] and ‘Female Sexual Interest and Arousal Disorder’ [All Fields] and [MeSH Terms]) and Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder ([All Fields] and [MeSH Terms]) and (‘humans’ [MeSH Terms] and (‘women’ [MeSH Terms] or ‘female’ [MeSH Terms]) and ‘adult’ [MeSH Terms]) and ‘menopausal’ or ‘postmenopausal’ ([All Fields] and [MeSH Terms]). This strategy was adapted and applied to different Internet search engines to the MEDLINE database (1966–June 2023).

No limits were set in terms of time of publication. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews and meta-analysis were considered. The search was performed for publications in English and publications were included if the full text of the article was available. Articles based on animals models or that evaluated other treatments for FSIAD were excluded, as well as those focusing on men sexuality.

One reviewer (CCB) independently evaluated the eligibility of the trials. Two other reviewers (LR, LL) extracted the data from the selected articles using a prefixed protocol (information was gathered on the characteristics of the participants in the trial, the intervention and how the results were measured).

When extracting data from the selected reports, those that could be relevant for the treatment of FSIAD in the postmenopause with ST were picked in a first screening. Afterwards, the most relevant were introduced in the present review. LR, LL and SA undertook the selection of the data and CCB checked any possible mistake that could have occurred during the first data extraction.

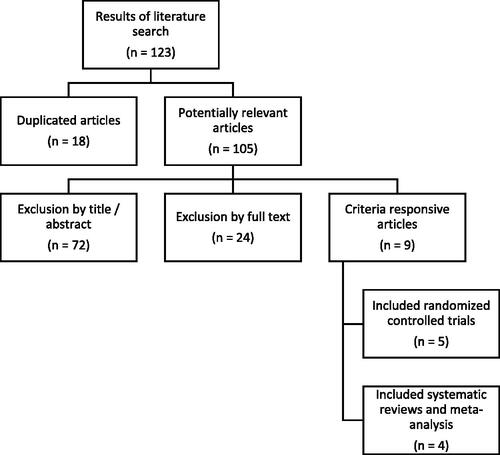

123 articles were screened, 105 of them assessed for eligibility, and finally 9 were included in qualitative synthesis. The process of article selection is schematized in , with a flowchart following the PRISMA declaration.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram showing the selection process.

Main reasons for excluding articles from analysis were: not addressing sexual outcomes, being based on an animal model and having a study design not aligned with the inclusion criteria of the review.

Of the reviewed articles, literature reviews or those the purpose of which was not to demonstrate ST impact on female sexual desire in the postmenopause were not considered.

Results

General characteristics of the studies

Over the last two decades, many studies have been performed on the use of testosterone on postmenopausal women, either for HSDD treatment or for the evaluation of changes in the sexual desire domain in women without the sexual dysfunction diagnosis. As it can be seen in , 5 RCTs and 4 systematic reviews have been included in this work, with a study population ranging from 272 to 8,961 subjects. None of them has been focused on FSIAD and they have shown improvement in sexual function compared to placebo in postmenopausal women with HSDD.

Table 1. Relevant studies addressing systemic testosterone impact on female sexual desire in the postmenopause.

They have evaluated the use of testosterone alone and in combination with estrogens, different routes of administration (transdermic, oral, intramuscular, subcutaneous) and doses (150 or 300 μg/day). Although the target population has been mainly constituted by postmenopausal women, some studies have also included premenopausal subjects. Different tools have been applied to evaluate sexual outcomes of the treatment, being the number of satisfying sexual events (SSE) the one by far mostly used, although validated scales or questionnaires have sometimes been used. Noteworthy, some studies based on the use of testosterone in postmenopausal women, have sexual outcomes as secondary outcomes. Trials have a maximum follow-up period of 24 weeks for efficacy and 2 years for safety.

Testosterone regimens

Davis et al. [Citation14] settled the recommended dose in 300 μg/day (within the premenopausal range) in a study conducted in 2009 on which no sexual benefits were observed with the lower dose (150 μg/day) in comparison to placebo.

Regarding the route of administration, transdermal therapy (patch, gel, cream, or spray) has been seen to provide the most physiologic form of replacement; intramuscular injections and subcutaneous implants should be avoided because they result in supraphysiologic levels, and oral preparations are not recommended because of possible adverse lipid effects, including reduction in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and increase in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [Citation15]. Testosterone compounds should also be avoided as they are not rigorously regulated [Citation16].

Treatments tend to be used for 24 weeks, being improvement in the sexual sphere typically perceived at 6 to 8 weeks after initiating treatment (sometimes earlier) [Citation15]. Its use beyond 6 months should be reconsidered [Citation11,Citation17].

Safety and tolerability

In terms of safety and tolerability, the incidence of mostly mild androgenic adverse events (acne and hair growth) was slightly higher among the treatment patients compared with the placebo group, without other androgenic effects seen with supraphysiologic levels (voice deepening and alopecia) [Citation18,Citation19]. Lipid profiles, carbohydrate metabolism, cardiometabolic markers and renal and liver functions were unaffected, although panel’s recommendations do not extend to women with high cardiovascular disease as they were not included in the clinical trials [Citation16,Citation19]. No adverse effects on breast cancer or mammographic breast density have been seen, but trials were insufficient to assess long-term breast cancer risk [Citation20,Citation21]. Abnormal uterine bleeding has been reported, but no increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer has been detected (biopsy reporting atrophy or insufficient tissue) [Citation20]. No changes in memory, nor cognitive performance, mood, bone mineral density or other musculoskeletal health-related parameters are expected with the treatment and, therefore, testosterone supplementation should not be used to improve any of these situations [Citation11,Citation20]. No serious adverse events were seen with physiologic use, which is the reason why levels of testosterone need to be checked baseline and monitored during the treatment, but there is a lack of long-term safety data [Citation17]. Baseline measurement is also important to detect women to whom the therapy is unlikely to help (that is, with blood testosterone levels already in the upper quartile) [Citation16].

Sexual instruments of measurement

In relation to the instruments of measurement, our revision reflects the heterogeneity of the studies on the subject.

The four systematic reviews included in this work [Citation18,Citation19,Citation22,Citation23], as well as one of the RCTs [Citation14], are only based on the SSEs as a sexual outcome. SSEs are determined by asking women to record their subjective experience and frequency of sexual activity by paper or electronic diary, which records the number of intercourse and nonintercourse sexual events, number of orgasms, level of sexual desire, and satisfying sexual activity experienced [Citation24]. It represents a non-validated method to assess sexual dysfunction and desire and its minimally important difference (MID) has been established in an increase of >1 episode/month [Citation25].

Three RCTs consider, apart from the SSEs, the Profile of Female Sexual Function (PFSF) and the Personal Distress Scale (PDS) questionnaires [Citation26–28]. The PFSF is a patient-based instrument that has been validated for discriminating menopausal women with low libido from controls. It contains 37 items in seven domains (sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, sexual pleasure, sexual concerns, sexual responsiveness, and sexual self-image) and a single-item measure of overall satisfaction with sexuality. Scores range from 0 to 100 for each domain, with higher scores indicating increased sexual functioning or decreased concerns. A total score of less than 40 in the sexual desire domain is indicative of low sexual desire [Citation29]. The PDS is a validated questionnaire which measures distress caused by low desire. Its scores range from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less distress, and being a score of more than 40 indicative of distress [Citation30].

Another RCT [Citation31] only considers the Sexual Interest Questionnaire (SIQ), an unidimensional self-report scale that has been designed specifically to measure two domains of sexual function in postmenopausal females: desire (level of desire before menopause, current level of desire, degree of distress with current level, importance of desire, satisfaction with current level, frequency of sexual thoughts or fantasies) and sexual responsiveness (satisfaction with frequency of sexual activity, frequency of desire to engage in sexual activity). It contains ten items that are rated on a seven-point scale and has been validated to discriminate between symptomatic and non-symptomatic postmenopausal women in terms of low sexual desire [Citation31]. No cutoff has been established yet.

Sexual outcomes

Several studies have tested the transdermal formulation specifically designed for women with HSDD (not currently approved by many medical regulatory agencies) delivering 300 μg testosterone/day showing improvements in total satisfying sexual activity and in sexual desire and distress using the PFSF [Citation26–28,Citation32]. Therefore, ST has been shown to significantly improve desire and the rest of domains of sexual response, reducing the associated levels of distress in postmenopausal women [Citation5,Citation33].

Regarding follow-up, it has been described that 60% of women typically note an improvement in their sexual function 6 to 8 weeks after initiating treatment, although it may occur as early as 4 weeks, with maximal effects on sexual desire and SSEs typically occurring at about 12 weeks [Citation15]. Although serum testosterone levels do not correlate with the presence or absence of HSDD or its severity, probably given the intracrinology of androgen action [Citation34] that makes clinical outcomes difficult to predict from blood levels alone [Citation35], a correlation between testosterone concentration during therapy and improvement in sexual desire has been observed [Citation36]. Finally, it has been stated that treatment should be discontinued after 6 months of lack of clinically meaningful improvement (expected to happen in 20% of women under testosterone treatment [Citation16]) whereas, in case of improvement, it should be continued for 6 to 12 months before considering taking a drug holiday to see whether treatment is still required (in case it was, beyond 6 months use, testosterone concentration should be measured regularly, approximately every 6 months) [Citation11,Citation17].

Discussion

For decades, women have been treated with testosterone in an attempt to alleviate a wide range of symptoms, with unclear risks and benefits.

However, over the past two decades, scientific effort has been made to dilucidate its risks and benefits profile.

The available evidence shows a moderate therapeutic benefit, compared to placebo, in the use of systemic transdermal testosterone, dosed in a physiologic premenopausal range (300 μg/day), in postmenopausal women with HSDD not related to modifiable factors or comorbidities [Citation17], and there is no data showing severe short-term adverse effects. One additional SSE per month has been both statistically significant and a clinically relevant change to the study subjects [Citation16,Citation37], being identified as the threshold improvement best able to differentiate menopausal responders and nonresponders [Citation38]. On this way, it should only be started after a proper psychosocial evaluation and management of potential contributors to decreased sexual desire such as: dyspareunia, fatigue, vasomotor symptoms, anemia, thyroid disease, anxiety, depression, sexually repressive cultural or religious values, side effects of other medications and relationship problems. This fact does not exclude the possibility of a combined treatment which equally addresses the implicated psychological and sociocultural factors [Citation15]. If the treatment is considered by the clinician, comprehensive counseling needs to be provided to the patient within the frame of sexuality biopsychosocial model, which locates the medical treatment with testosterone as a pharmacological facilitator of much more complex inner processes.

Remarkably, part of the scientific evidence for testosterone treatment on menopausal women with HSDD is derived from studies on menopausal women without the sexual dysfunction diagnosis. Considering the present review, one out of five RCTs and three out of four meta-analysis are performed considering the effect of ST on menopausal women (without HSDD diagnosis), which implies the extrapolation of results from a population without a sexual concern to the targeted group with sexual distress due to lowered sexual desire. With such inference, the psychosocial contributors of a sexual dysfunction are not considered neither addressed.

Another extrapolation which needs to be performed in the majority of studies addressing this topic is regarding the entity itself. As it has been previously mentioned, clinical trials have been conducted using the past entity for low sexual desire (HSDD), whereas nowadays entity (FSIAD) implies the coalition between low desire and arousal dysfunctions.

Studies have also been heterogeneous on their design (different testosterone doses, routes of administration, testosterone use in combination and alone, sexual instruments of measurement), a fact that hinders the interpretation of results regarding its applicability on FSIAD in the postmenopause. Furthermore, sexuality has been evaluated as a secondary outcome in many studies, instead of being the main objective for which the study had been specially designed. As it has been previously mentioned, and according to recommendations from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) draft guidance [Citation24], the quantification of SSEs has been the main criterion for assessing efficacy, which can represent an unobjective and partial outcome of sexual desire due to the lack of standardization, the fact that does not specifically assess distress related to desire and qualitative information provided by the indicator. In fact, in other trials, increases in the frequency of SSEs were not always accompanied by increases in desire or vice versa [Citation24], which is attributed to the fact that the number of sexual encounters is not part of the criteria for female sexual dysfunction and simply counting cannot properly assess a complex and multidetermined construct such as desire. Apart from that, the use of daily diaries is associated with a placebo effect irrespective of the assessed condition, which complicates the demonstration of significant treatment effect. In this way, women might experience improved desire but choose not to engage in sexual activities or may not perceive the activity as satisfactory for reasons not related to their desire. Therefore, instead of data collected using daily diaries, findings in the literature support the use of patient-reported outcomes [Citation24] with symptom-related scales such as the PDS or SIQ to capture the multidimensional and subjective nature of female sexuality. Unfortunately, only 4 RCTs, and none of the analyzed meta-analysis, specifically assess distress atributted to low desire.

Even though there have been several reviews on ST use in postmenopausal women, this review has a special focus on the instruments of measurement and the analyzed population, suggesting the need for better designed trials. According to that, only 3 studies [Citation26–28] have used psychometric instruments which provide meaningful and valid end points to study female sexual desire (and, therefore, measure distress related to desire) and selected the appropriate population of study (that is, postmenopausal women presenting with the female sexual dysfunction). However, being strict and only analyzing these studies, conclusions remain similar and our findings are following the scientific societies recommendations regarding systemic transdermal testosterone use at 300 μg/day in the postmenopause to treat HSDD. Nevertheless, further studies with better methodology design, taking into account the previously mentioned information, are needed.

In 2019 (39) and 2021 (15) global consensus position statements endorsed by many international scientific societies established candidates for testosterone therapy are postmenopausal women with decreased sexual interest (with or without reduced arousal), causing stress or personal or interpersonal impact, and who seek treatment, on which its moderate effect is translated to 1 additional SSE per month on average [Citation39].

Nevertheless, treatment with testosterone has been limited by its off-label prescription due to the fact that specific formulations for women, whose therapeutic requirements of testosterone are less than one-tenth of those for hypogonadal men, have not been generally approved by national drug regulatory authorities such as the European Medicine Agency (EMA) and the US FDA (but for a female-tailored testosterone cream in Australia) [Citation33].

Despite having testosterone as a valuable tool, long-term safety data are lacking and off-label prescription is needed. These are issues to be comprehensively discussed in the shared decision-making process as, for example, the lack of regulatorily approved formulations for women expose them to an inappropriate dosing. Therefore, more therapeutic strategies in the pharmacological field of HSDD/FSIAD and, more extensively, female sexual dysfunctions need to be provided.

The authors of this article strongly believe neuroimaging studies to disentangle the functionalism of the most potent sexual organ could provide valuable information regarding the desire substrate under both physiologic and dysfunctional conditions (e.g. FSIAD), which would be useful to speculate and test the applicability in this field, according to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, of already approved drugs for women with a good safety profile. It is also fundamental to use validated instruments designed to measure the desired condition (in this case, FSIAD in postmenopausal women), avoiding design heterogeneity and considering level of distress, in order to be able to draw robust conclusions. Therefore, better designed trials that include the combination of neuroimaging and validated patient reported outcomes could be of much interest in this field of research.

Acknoledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the helpful and constructive feedback provided by the reviewers during the review process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

This manuscript is a narrative review carried out using medical search engines (Pubmed, Embase and Medline) and the data included come from originals already published by other authors; therefore, we cannot share these data as they are not our property. To get access to the data of the different series included in this review, the authors of the referenced works should be directly consulted.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Marin R, Escrig A, Abreu P, et al. Androgen-dependent nitric oxide release in rat penis correlates with levels of constitutive nitric oxide synthase isoenzymes. Biol Reprod. 1999;61(4):1–7. doi:10.1095/biolreprod61.4.1012.

- Graziottin A, Leiblum SR. Biological and psychosocial pathophysiology of female sexual dysfunction during the menopausal transition. J Sex Med. 2005;2(Supplement_3):133–145. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00129.x.

- Munarriz R, Kim NN, Goldstein I, et al. Biology of female sexual function. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29(3):685–693. doi:10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00069-1.

- Nappi R, Wawra K, Schmitt S. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22(6):318–323. doi:10.1080/09513590600762265.

- Nappi RE, Albani F, Santamaria V, et al. Menopause and sexual desire: the role of testosterone. Menopause Int. 2010;16(4):162–168. doi:10.1258/mi.2010.010041.

- Jones SL, Rosenbaum S, Gardner Gregory J, et al. Aromatization is not required for the facilitation of appetitive sexual behaviors in ovariectomized rats treated with estradiol and testosterone. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:798. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00798.

- American Psyschiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental diseases (DSM-5). 5th edition. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013; 2014. Panamericana, editor.

- Nappi RE. Why are there no FDA-approved treatments for female sexual dysfunction? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(12):1735–1738. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1064393.

- Dennerstein L, Koochaki P, Barton I, et al. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in menopausal women: a survey of Western European women. J Sex Med. 2006;3(2):212–222. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00215.x.

- Berra M, De Musso F, Matteucci C, et al. The impairment of sexual function is less distressing for menopausal than for premenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2010;7(3):1209–1215. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01666.x.

- Davis SR. Use of testosterone in postmenopausal women. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2021;50(1):113–124. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2020.11.002.

- Cipriani S, Maseroli E, Di Stasi V, et al. Effects of testosterone treatment on clitoral haemodynamics in women with sexual dysfunction. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(12):2765–2776. doi:10.1007/s40618-021-01598-1.

- Maseroli E, Santangelo A, Lara-Fontes B, et al. The non-aromatizable androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT) facilitates sexual behavior in ovariectomized female rats primed with estradiol. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;115:104606. (doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104606.

- Davis SR, Moreau M, Kroll R, et al. Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(19):2005–2017. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0707302.

- Parish SJ, Simon JA, Davis SR, et al. International society for the study of women’s sexual health clinical practice guideline for the use of systemic testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. J Sex Med. 2021;18(5):849–867.

- Slomski A. Which postmenopausal women should use testosterone for low sexual desire? JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323(6):493–495. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.22070.

- Parish SJ, Kling J. NAMS PRACTICE PEARL: testosterone use for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2023;30(7):781–783. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000002190.

- Achilli C, Pundir J, Ramanathan P, et al. Efficacy and safety of transdermal testosterone in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(2):475–482.e15. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.10.028.

- Islam RM, Bell RJ, Green S, et al. Safety and efficacy of testosterone for women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trial data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(10):754–766. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30189-5.

- Pinkerton JAV, Blackman I, Conner EA, et al. Risks of Testosterone for Postmenopausal Women. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2021;50(1):139–150. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2020.10.007.

- Gera R, Tayeh S, Chehade HEH, et al. Does transdermal testosterone increase the risk of developing breast cancer? A systematic review. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(12):6615–6620. doi:10.21873/anticanres.13028.

- Ganesan K, Habboush Y, Sultan S. Transdermal testosterone in female hypoactive sexual desire disorder: a rapid qualitative systematic review using grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation. Cureus. 2018;10(3):e2401. doi:10.7759/cureus.2401.

- Jayasena CN, Alkaabi FM, Liebers CS, et al. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials investigating the efficacy and safety of testosterone therapy for female sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol. 2019;90(3):391–414.

- Kingsberg SA, Althof S. Satisfying sexual events as outcome measures in clinical trial of female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2011;8(12):3262–3270. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02447.x.

- Kingsberg S, Shifren J, Wekselman K, et al. Evaluation of the clinical relevance of benefits associated with transdermal testosterone treatment in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4(4 Pt 1):1001–1008. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00526.x.

- Buster JE, Kingsberg SA, Aguirre O, et al. Testosterone patch for low sexual desire in surgically menopausal women: a randomized trial. Obs Gynecol. 2005;105:944–952.

- Simon J, Braunstein G, Nachtigall L, et al. Testosterone patch increases sexual activity and desire in surgically menopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5226–5233. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1747.

- Panay N, Al-Azzawi F, Bouchard C, et al. Testosterone treatment of HSDD in naturally menopausal women: the ADORE study. Climacteric. 2010;13(2):121–131. doi:10.3109/13697131003675922.

- Derogatis L, Rust J, Golombok S, et al. Validation of the profile of female sexual function (PFSF) in surgically and naturally menopausal women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30(1):25–36. doi:10.1080/00926230490247183.

- Leiblum SR, Koochaki PE, Rodenberg CA, et al. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women: US results from the Women’s International Study of Health and Sexuality (WISHeS). Menopause. 2006;13(1):46–56. doi:10.1097/01.gme.0000172596.76272.06.

- Lobo RA, Rosen RC, Yang HM, et al. Comparative effects of oral esterified estrogens with and without methyltestosterone on endocrine profiles and dimensions of sexual function in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(6):1341–1352. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00358-3.

- Shifren JL, Davis SR, Moreau M, et al. Testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in naturally menopausal women: results from the INTIMATE NM1 Study. Menopause. 2006;13(5):770–779. doi:10.1097/01.gme.0000243567.32828.99.

- Al-Azzawi F, Bitzer J, Brandenburg U, et al. Therapeutic options for postmenopausal female sexual dysfunction. Climacteric. 2010;13(2):103–120. doi:10.3109/13697130903437615.

- Maseroli E, Cellai I, Filippi S, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of androgens in the human vagina. J Mol Endocrinol. 2020;65(3):109–124. doi:10.1530/JME-20-0147.

- Davis SR, Guay AT, Shifren JL, et al. Endocrine aspects of female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004;1(1):82–86. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10112.x.

- Demers LM. Androgen deficiency in women; Role of accurate testosterone measurements. Maturitas. 2010;67(1):39–45. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.04.019.

- Davis SR, Braunstein GD. Efficacy and safety of testosterone in the management of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2012;9(4):1134–1148. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02634.x.

- Derogatis LR, Graziottin A, Bitzer J, et al. Clinically relevant changes in sexual desire, satisfying sexual activity and personal distress as measured by the profile of female sexual function, sexual activity log, and personal distress scale in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire dis. J Sex Med. 2009;6(1):175–183. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01058.x.

- Davis SR, Baber R, Panay N, et al. Global consensus position statement on the use of testosterone therapy for women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(10):4660–4666. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-01603.