ABSTRACT

Problematic interactional patterns between client and therapist involve several phenomena, such as different forms of ruptures, enactments, impasses, and stalemates. This study explores psychodynamic therapists’ experiences and understanding of deadlock in the psychotherapy process. Interviews with eight experienced therapists were analyzed applying the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). Generally, the therapists described the deadlock as a negative process, blocking the progress of therapy. The deadlock confronted them with unfulfilled expectations of closeness and connection, as well as unwelcome feelings and wishes, and evoked self-doubt and questioning of their own professional role. The therapists experienced a loss of agency and reflective capacity in the encounter with the client. We found an elusive quality of something absent and incomprehensible in the therapists’ experiences. Resolution of deadlock interacted with therapists finding a constructive role in the therapeutic relationship and being able to give meaning to their experiences. We conclude that the therapists need to be observant of their experiences of deadlock and talk to others about them. The knowledge of deadlocks as natural phenomena in the therapy process that can be recognized, addressed, and worked with must be more widely diffused and should be an integral part of psychotherapy education and training.

Effective psychotherapy presupposes the development of a trustful relationship and working alliance between the client and the therapist (Norcross & Wampold, Citation2011; Tryon & Winograd, Citation2011). Problematic interactional patterns between client and therapist are possibly the most important reason for therapeutic failures in psychodynamic psychotherapy (Gold & Stricker, Citation2011). A weakened alliance correlates with clients’ unilateral therapy dropout (Roos & Werbart, Citation2013; Safran, Muran, & Shaker, Citation2014). Non-improved clients tend to experience the therapist as too distanced or passive (Werbart, von Below, Brun, & Gunnarsdottir, Citation2015), whereas their therapists could say that the clients reacted with aversion to closeness (Werbart, von Below, Engqvist, & Lind, Citation2019b). Accordingly, for therapy to be effective, therapists must possess the ability to attune the treatment to each client’s individual needs (Lambert & Barley, Citation2001; Werbart, Annevall, & Hillblom, Citation2019a).

However, evidence shows that therapists’ and clients’ views of what is important in therapy differ, and this gap is even larger when difficulties in the therapeutic process emerge (Gold & Stricker, Citation2011; Lilliengren & Werbart, Citation2010). If negative therapy processes continue unnoticed, hostility can emerge between therapist and client, leading to negative therapeutic outcomes (Gold & Stricker, Citation2011; von der Lippe, Monsen, Rønnerstad, & Eilertsen, Citation2008). However skilled the therapist is, relational problems and impasses will inevitably emerge in the course of psychotherapy (Omer, Citation2000; Råbu, Halvorsen, & Haavind, Citation2011). Negative experiences and feelings in therapy can be sources of important clinical information (Wolf, Goldfried, & Muran, Citation2017). Qualitative studies can give further information on how client and therapist interpret and give meaning to their needs and behaviors when facing difficult therapy processes (Halvorsen, Benum, Haavind, & Mcleod, Citation2016; Moltu & Binder, Citation2011). Examining the implicit knowledge of experienced therapists can increase our understanding and contribute more information about what is effective and what impedes therapeutic treatments (Lilliengren & Werbart, Citation2010).

Different terms have been used to describe the condition when the therapy process stagnates: impasse (Atwood, Stolorow, & Trop, Citation1989; Hill, Nutt-Williams, Heaton, Thompson, & Rhodes, Citation1996; Kantrowitz, Citation1993; Rosenfeld, Citation1987), deadlock (Hill et al., Citation1996; Stern, Citation2010), stalemate (Moltu, Binder, & Nielsen, Citation2010; Omer, Citation2000), and stuckness (McLeod & Sundet, Citation2020). Related concepts are alliance ruptures and enactments (Safran et al., Citation2014). Henceforth, we use the word “deadlock” as a superordinate term for related expressions represented in the literature or used by respondents in our study. Deadlock has been described as interplay between therapist and client leading to a halt in the therapy and becoming a hindrance to the treatment (Bernstein & Landaiche, Citation1992), or as a process where therapy becomes so difficult or complicated that no progress seems possible (Atwood et al., Citation1989). Other descriptions of deadlock are “a paralysed analytical process” (Maldonado, Citation1984), “phases of stagnation” (Moltu et al., Citation2010) and “a tension in the relation” (Safran et al., Citation2014).

Historically, some forms of psychotherapy have considered deadlocks as representing the client’s resistance to improvement (Bernstein & Landaiche, Citation1992; Whitaker, Warkentin, & Johnson, Citation1950). However, in order to understand and manage deadlock, we have to consider the interpersonal context (Atwood et al., Citation1989). With an isolated focus on the client, the therapists run the risk of becoming blind to their own influence on the situation. Severe deadlocks occur when the therapist’s and the client’s personal difficulties, vulnerabilities and defenses interact in unmanageable ways and both get stuck in locked positions that seem impossible to break free from (Maldonado, Citation1984; Safran & Kraus, Citation2014; Suchet, Citation2015). Deadlocks are sometimes described as alliance ruptures, and ruptures as enactments (Safran & Kraus, Citation2014; Safran et al., Citation2014; Stern, Citation2010; Yerushalmi, Citation2015); however, deadlocks are usually described as lasting for longer periods of time.

Whitaker et al. (Citation1950) distinguished an impasse from an initial “inertia” that can arise in some therapies, describing an impasse as a “stalemate” or a “plateau” in the process of achieving the therapeutic objective. According to these authors, symptoms of impasse include emotional withdrawal expressed through intellectualization, emphasis on symptoms, exclusive interest in non-psychological problems, or periods of meaningless silence, evoking frustration and irritation in both therapist and client. Kantrowitz (Citation1993) described impasses in psychoanalysis as a result of the client interpreting the analyst’s behavior as a repetition of a previously painful, frightening experience. Consequently, the client no longer considers it safe or fruitful to proceed, and the therapy process is stalemated. According to her, the difference between impasses and strong negative transference/countertransference reactions is that impasses remain unresolved, and when they persist, most clients leave treatment. In the psychoanalytic tradition, enactments and impasses are understood in terms of unresolved negative interplay between the client’s transference and the therapist’s countertransference (Hill et al., Citation1996; Kantrowitz, Citation1993; Safran & Kraus, Citation2014). Transference can be understood as everything the client brings to the therapy relationship, including interpersonal expectations and fears, and these evoke certain countertransference responses from the therapist (Gabbard, Citation2020; Høgland, Citation2014).The therapist’s countertransference can contribute to enactments and impasses, but can also provide information that the therapist can use in the therapy process (Aron, Citation2006; Benjamin, Citation2009).

To sum up, the deadlock in psychotherapy seems to be a relatively unexplored phenomenon. Different synonyms – deadlock, stalemate, standstill, stuckness, impasse, rupture – have been used, but clinical case studies lack consensus on the nature of this phenomenon, and its meaning is seldom analyzed (Atwood et al., Citation1989; Davies, Citation2003; Kantrowitz, Citation1993; Maldonado, Citation1984; McLeod & Sundet, Citation2020; Rosenfeld, Citation1987; Safran, Citation2002; Safran et al., Citation2014; Suchet, Citation2015). The present study explores the phenomenon of deadlock from the experienced psychodynamic therapists’ perspective with the aim of making their experiential, tacit knowledge more explicit and systematic. How do experienced psychodynamic therapists perceive and describe deadlock in the psychotherapy process? How do they make sense of such experiences and use them in their therapeutic work?

We regarded the qualitative methodology of the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) as the method of choice for capturing the phenomenon in focus. The IPA is concerned with how participants make sense of their lived experiences and with understanding their sense-making through interpretative activity (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013; Larkin, Watts, & Clifton, Citation2006). Thus, the IPA combines inductive procedures with a focus on the interpretation of meaning. Accordingly, the epistemological assumption of this investigation was that rich personal accounts of the participants can tell us something essential about the “what” and “how” of their lived experiences (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin, Citation2009). Furthermore, we assumed that the participants’ different perspectives will reveal different features of the phenomenon in focus.

Method

Participants

An invitation to participate in this study was sent by e-mail to members of the Psychotherapy Center Stockholm and the Swedish Psychoanalytical Association. Therapists interested in sharing their experiences of therapeutic processes that had got stuck or had arrived at a deadlock were invited to contact us. We used purposive sampling to find a defined group for whom the topic at hand had relevance and personal importance (Pietkiewicz & Smith, Citation2014). Criteria for participation were the therapist having training in psychodynamic psychotherapy, having had their license for at least two years, and having at least one client in active therapy at the time of the interview.

Eight first respondents to the invitation were included, five women and three men, between 53 and 75 years old (Mdn = 56), and with between three and 30 years of experience as licensed psychotherapist (Mdn = 15). Three of the therapists were publicly employed and five were in private practice. All treatments mentioned by the therapists had occurred at a frequency of once or twice a week. In accordance with the interview protocol, the therapists were asked to report one instance of deadlock each; however, one of them reported two contrasting cases. Four of the cases involved female clients and five cases involved male clients. No other client data were collected as the focus was on the therapists’ experiences of deadlock.

Researchers

Interviews with therapists and data analysis were conducted by the second and third authors as part of their master’s thesis; at the time of the study they were female students in a five-year psychology program (psychodynamic orientation). The first author, a male senior researcher and psychoanalyst, was involved in the planning of this study, preparing the interview protocol, and conducting continuous audits of data analysis.

Interviews

The semi-structured interviews followed a guide indicating the main areas of interest. The aim of the interviews was to collect as rich and descriptive a body of material as possible, with space and flexibility for unexpected issues to emerge (Pietkiewicz & Smith, Citation2014). With the inductive starting point of IPA no specification of the phenomenon under scrutiny was given and the interviewers’ stance was that of a naive and curious listener who was interested in the concerns of the participants (Smith et al., Citation2009). Initially, the therapists were asked to describe their perceptions and views of the phenomenon of deadlock or standstill in the therapy process. Subsequently, they were invited to give a narrative description of one particular case and their understanding of when and how their experience of deadlock happened, including their own as well as the client’s contributions. Further questions focused on the effects the deadlock had had on the therapist and the therapeutic collaboration: the therapist’s feelings and ways of coping with them; how the experience affected the therapeutic relationship and its developments; if and how the deadlock could be resolved; and what happened afterwards. Finally, the therapists were asked if there was something more that the therapist thought the interviewer might need to know to better understand what they were talking about in the interview. The therapists were also asked about their own experience of participation in the interview. The audio-recorded interviews were conducted by the second and third authors (four interviews each) at the therapists’ offices or in a booked room in a library and lasted 50–90 minutes. The responders gave their written consent prior to the interview.

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

The interview transcripts were analyzed, applying IPA. IPA focuses both on the individual’s specific experience in depth and on the common experiences of the participants in order to identify and interpret distinct components of the phenomenon in focus (Larkin et al., Citation2006; Pietkiewicz & Smith, Citation2014). IPA involves a “double hermeneutics” of making sense of the participants’ making sense of the phenomenon in focus (Smith et al., Citation2009). The coders transcribed verbatim four interviews each and analyzed their interviews following the steps recommended by Smith et al. (Citation2009). Descriptive analysis focused on what had been said and what had not. Linguistic analysis examined how the respondents expressed themselves in the interviews. Conceptual analysis involved a preliminary interpretation of the content of each interview. These analyses resulted in notes brought to the next step. The coders met on four occasions, during which they jointly crystallized core aspects of the therapists’ experiences and successively clustered them into superordinate themes (). In the last step, all interviews were individually compared with the emerging themes, focusing on both common and unique aspects of the therapists’ experiences. At each step of the data analysis the coders conducted constant comparative analysis, comparing new understanding with already formulated results and shifting focus between the parts and the whole (Breakwell, Smith, & Wright, Citation2012).

Credibility checks

The procedure of independent analyses, consensus discussions, working together and audits of each step of data analysis was inspired by consensual qualitative research (CQR; Hill et al., Citation2005) and was aimed at increasing the trustworthiness of the analysis (Williams & Morrow, Citation2009). The rationale for this procedure was our assumption that both the interpersonal psychotherapy processes and the phenomenological/ hermeneutic inquiry are deeply rooted in intersubjective co-construction of meaning. The frequencies of participants contributing to each theme were scrutinized as an additional validity check and reported using nomenclature from CQR: general = all or all but one of the cases (8–9); typical = more than half of the cases up to the cutoff for general (5–7); variant = at least two cases (2–4). The results of the analysis and the illustrating quotations were sent to the therapists for a member check (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985; Thomas, Citation2017). The therapists were asked to provide feedback on how the authors had understood their experiences. Six out of eight therapists responded, three of them approved the results and a further three gave feedback resulting in minor changes.

Reflexivity

In accordance with the phenomenological approach to reflexivity (Mortari, Citation2015), the authors strived for rigorous introspective self-examination, paying attention to how faithfully they interpreted and described the participants’ subjective experiences, and being open to how newly appearing aspects of the phenomenon might change an earlier understanding. Conducting the interviews and data analysis, the authors tried to “bracket” (Fischer, Citation2009) their preconceptions, prejudices and ideas, and to maintain an attitude of curiosity and not-knowing. Following the “double hermeneutics” of IPA, the bracketing could only be partially achieved. Accordingly, the authors applied a cyclical approach to their reflective activity, as recommended by Smith et al. (Citation2009). They met on five occasions and made a written record of their presumptions, biases, and emotional states potentially influencing the interviews and data analysis, for example their presumption that there may be gender differences in causal attribution of emerging deadlock, or that certain types of deadlock would not be mentioned, such as those emerging from sexual attraction. The aim of bracketing was to raise awareness of own potential influence on the data, data analysis and interpretations, and to facilitate meta-positions, creating adequate reflective distance to the study setting (Malterud, Citation2001).

The interest in the studied phenomenon originated in the authors’ clinical experiences, thus influencing the design of this study. The first author had a special interest in research on unsuccessful psychotherapies and on the clients’ and the therapists’ perspectives. The second and third authors had a particular interest in trauma, sexualities and gender, and their influence on interpersonal processes in psychotherapy. The interpretation of findings was informed by the contemporary intersubjective/relational psychoanalytic tradition.

Ethical considerations

Before starting the study, all authors filled out and signed the “Ethics Declaration,” following the ethical guidelines required at Swedish universities for master’s theses in psychology. The Swedish Ethical Review Authority exemption was examined and granted by the responsible authority at the Department of Psychology, Stockholm University. All participants received an official letter with information about relevant ethical aspects and gave their written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki prior to the interviews. They are also kept anonymous in the present report.

Results

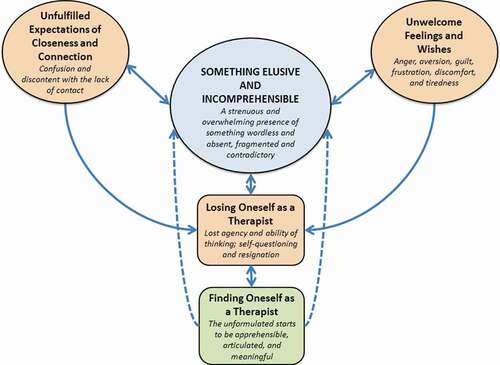

We start by presenting how differently the interviewed therapists could describe stalemates in the therapy process. We then move on to describe and interpret the experience itself, as captured in the superordinate themes unfulfilled expectations of closeness and connection, unwelcome feelings and wishes, and something elusive and incomprehensible. The effects this experience had on the therapist are depicted in two further superordinate themes, losing oneself and finding oneself as a therapist. Finally, we sum up the constitutive facets of the deadlock phenomenon. The hypothetical interconnections between these different facets of the deadlock phenomenon are represented in . All quotations below refer to the therapists’ narratives about particular cases of the emergence of this phenomenon [the therapists’ alias are in square brackets].

Figure 2. A tentative model of interconnections between different facets of the therapists’ experiences of deadlock and how the quality of Something Elusive and Incomprehensible was present in all other superordinate themes (the core theme in upper-case letters).

Generally, therapists described deadlock as a standstill affecting or hindering the therapy process: “Deadlocks are like standstills … the flow has stopped” [Anne]. “Are we at a dead end? Can’t we move on? Stagnation … Are we spinning our wheels?” [Carl]. As a variant, the therapist might experience deadlock from the very beginning: “But sometimes it’s so painful that you don’t feel that you … don’t even get started, the whole therapy is marked by a deadlock” [Frida]. Helena described the deadlock as literally a rupture in the therapeutic relationship: “For me, deadlock is maybe … yes, in a way it’s when someone chooses not to continue […] not to see each other, then nothing can occur between us.” Whereas deadlock was generally described as a negatively experienced and an often unendurable phenomenon, the therapists typically also described deadlock as something inevitable and necessary, a time for stabilization and contemplation. George interpreted deadlock as a time-limited phase in an ongoing interpersonal process:

Looking the other way around, there is no deadlock in any therapy because something is always going on. But there are occasions you can experience partially as deadlock, during a session or a minute; it is related to time and to the relationship. [George]

Diane described deadlock in more neutral terms, as a necessary break in what is going on: “It’s restful but sleepy and sort of, rather boring. But in a way, quite comfortable for me.” As a further variant the deadlock was marked by cheerfulness in the therapeutic relationship, experienced as a hindrance in the therapy process:

You’re sitting there having a nice time … making the therapist your friend. … It is also a defense against something. Laughter, a patient that laughs, you slip into it … you laugh when the patient leaves … for me therapy is a serious matter. [Boris]

Deadlocks were generally experienced as difficult and confusing. The deadlocks mentioned in the interviews were different in character and had been going on for various periods of time, from a few months up to several years. Occasionally, deadlocks recurred frequently in the same therapy. The cases the therapists chose to talk about were described and experienced as exceptionally difficult, concerning, or otherwise special.

Unfulfilled expectations of closeness and connection

Talking about their experiences of deadlock, the therapists generally expressed more or less explicit expectations of the therapy relationship: what the therapy was supposed to be, what the therapist’s own role should be, and what hopes – both the client’s and the therapist’s – the therapy was expected to fulfill. These expectations of closeness and connection remained unfulfilled in the deadlock situation, and the therapists expressed their discontent with the perceived distance in the relationship:

There was very little connection and it’s very hard when you don’t make contact. You get tired from a lack of connection, it makes you very tired. So it became a real lull and I thought: God damn it, this is hard! [Boris]

Here, the lack of contact was described as a “lull.” Boris expressed frustration over the client’s non-responsiveness and emphasized how difficult it was to endure the lack of relatedness, repeating himself and swearing. Generally, the therapists expressed expectations that the therapeutic relationship would be deeper or more intensive than it actually was. Typically, this was accompanied by confusion, not accepting the client’s way of relating, or by disappointment when the therapists experienced themselves as being shut out by the client. Frida recounted how an attachment between therapist and client never developed. Carl described desperation in the experience of distance and not being let in by the client: “Yes, but I can … experience some sort of, like despair at not really getting through to him … It shouldn’t have to be like this for you … I can help you.” By expressing how the current situation “shouldn’t have to be like this” Carl seemed to emphasize that he could help his client if only the client would allow him. His frustration and expressed despair suggested that he had got into something that he could not understand.

Generally, the therapists expressed an ambition to give the client a new relational experience in the therapy, and this was thwarted in the deadlock situation. Expectations of closeness and connection typically appeared in metaphors of being like a parent, a teacher, or a partner: “He just harped on … It’s like when you have heard about someone going on a date … and they meet a person who talks for an hour about themselves.” [Boris]. In this passage Boris expressed his feeling of being treated like an audience. The analogy of being on “a date” with a person who “talks for an hour about themselves” strengthened his experience of being a partner who was excluded from the conversation. This might be interpreted as frustrating his yearning for closeness in the therapeutic relationship. Other metaphors for the distance experienced by the therapists were “dying as a therapist” [Boris] or “being like an abandoned infant lacking a bond and closeness, who shuts off and eventually dies” [Boris and Helena]. Thus, the experience of lacking contact with the client could range from frustrating and distressful to extremely anxiety-provoking and life-threatening.

Unwelcome feelings and wishes

Generally, deadlock evoked negative feelings, wishes and impulses in the therapists. These were not always explicitly expressed, and therefore were perceived by the interviewers as shameful or otherwise painful or unwanted. In the interviews, these feelings often became apparent in the use of language, unsympathetic descriptions of the client’s problems, laughter, sighs, and groans during the interviews. These unwelcome feelings and wishes differed but typically referred to the therapists’ reactions that could or actually had affected the therapy negatively. The therapists could feel anger toward the client and might experience such feelings as unacceptable, or fight to resist falling asleep during the session. Typically, they did not talk to their clients about their negative experience in the relationship and they could blame the client for the deadlock. Esther openly admitted her dislike of the client: “and I realized that if I couldn’t keep track of my countertransference feelings I might become quite nasty to her. We could end up in verbal mudslinging.” By using the phrase “mudslinging” Esther seemed to imply that the situation could have become ridiculous if she had allowed her countertransferential reactions to rule. The awareness of negative feelings could give the therapist the capacity to resist acting, thereby avoiding a destructive therapy relationship.

Even positive feelings and wishes could be experienced as unwelcome and involved in the co-construction of deadlock. Typically, the therapists revealed a yearning to be special for the client, for example being different than the client’s parents or former therapist. As a variant, the therapists described a painful experience of not being seen by the client and reproached them for not relating to the therapist as a person. Yet another variant was being drawn into flattering situations: “to sit there and show off and be [laughing] idealized, which really is a thing to be noted, when you are being over-idealized” [Esther]. Esther regarded “showing off” as the therapist relaxing and having a nice time with the client. She made a critical reflection on her own position, laughing at herself, thus revealing some discomfort at having enjoyed the idealization. The shift in Esther’s formulation from “idealized” to “over-idealized” can be interpreted as the idealization being greater than she had been aware of initially.

Something elusive and incomprehensible

In general, deadlock was experienced as so psychologically strenuous and overwhelming that the therapists tried to tune out from their feelings in different ways. As a variant, they described not being able to think in the presence of the client, and this was generally manifested in the interview as not being able to think or express themselves in the presence of the interviewer. The therapists’ experiences of something unformulated and not yet understood showed an elusive, unfathomable quality, a presence of something wordless and absent in the material. For George, these elusive experiences had a quality of cognitive disturbances:

Sometimes it felt as though I couldn’t think, or, it also depended on, I also wondered what it depended on, that I had problems following my own thoughts in the office, I couldn’t, I myself just started to dissociate.

George described a state of having problems following his own thoughts, and he sought an explanation for his alarming experience. Finding no explanation, he continued to describe the therapy situation, showing how he lost his mental presence in the sessions. The state of confusion and not understanding was a typical sequel of deadlock. This could be reflected in the therapists’ fragmented and dissociated narratives or in the use of several inconsistent explanations:

And I also think that the fact that … I never could put this together in some way, anyhow, that I could get any … understanding of something. Thus, it never got into a framework where I could … feel empathy for him … I could understand the theme itself, that there was something in this … that it just like floated around in some sort of chaos, it was so … pervasive. [Frida]

In this passage, Frida followed her associations and her narrative took an exploratory, tentative form, consisting mostly of negations. The “pervasive” quality of her experience of chaos is reflected in the very structure of her account. The elusive, unfathomable quality of the therapists’ experiences manifested itself when something evasive and wordless in their narratives was significantly present as a mute “hole.”

Losing oneself as a therapist

All therapists described a loss of agency and analytical thinking in the deadlock situation. Typically, this was followed by self-doubt and questioning of the therapist’s own professional role. Losing oneself as a therapist led to uncertainty and suffering, and had both psychological and somatic impacts. Feelings of incompetence and worthlessness were accompanied by frustration, anger, and resignation. The therapists could feel helpless and incapable, could react in uncharacteristic ways, and could feel themselves being stuck or drawn into something:

Yes, but it was almost a physical feeling of being nailed to the chair … since the patient was so extremely sensitive to me moving at all … I became powerless, bereft of my tools. [Esther]

Esther’s experience of deadlock was a physical feeling of being nailed to the chair, thus the loss of agency became a bodily sensation. She could not maintain her therapeutic position and use her tools. Generally, the therapists were convinced that their own reactions contributed both to the emergence and the maintaining of the deadlock. Thereby, they could end up in collusion with the client, either by not confronting the client or by participating through enactments in the client’s personal scenario. Typically, the therapists got stuck in oppositional, complementary roles in relation to the client:

In the beginning I think I became, what should I say, quite active! Like when you try to resuscitate someone who is dying … then I got a little tired of that, I suppose. And then we were both dying … And when the therapist is dying, then you have to look at what is happening. Yes, nothing is happening. [Boris]

The client’s passivity in the therapy is compared here to dying, and Boris initially reacted by increasing his own rescue activity. When Boris stopped being the only one carrying out the therapy, he said that nothing was happening and he experienced that they were both dying. His use of the “dying” analogy shows how dramatically this situation was experienced and implies that he was losing both himself and the client.

In the deadlock situation, the therapists typically questioned their capabilities and occasionally lost their self-reliance. These experiences were described in terms of meaninglessness, dejection, inadequacy, being inferior, worthlessness, and being unable to do anything right: “There you can begin to doubt your own competence, too. What is it that doesn’t … ? I’m no good [sighs]. I’m no good at all” [Carl]. In this statement Carl went from wondering about something to questioning his own competence and describing himself as “no good.” This might suggest that his self-doubt extended from his professional role to himself as a person.

Finding oneself as a therapist

Finding oneself as a therapist coincided, according to our understanding, with the experience of establishing an ongoing collaboration between the therapist and the client as two autonomous agents. The deadlock could be overcome in seven of the cases described by the therapists, whereas Carl experienced that the deadlock was not fully resolved, and in one of Frida’s two cases the impasse led to interrupted treatment. Generally, the therapists used theoretical knowledge as guidance in the process of retrieving their professional role in relation to the client. To be still there and endure the hardship appeared as a typical aspect of the therapeutic relationship. When the therapists had found a greater psychological freedom in the therapeutic encounter they also described their clients in more sympathetic terms. Typically, the therapists described reflecting on their own role in the relationship before the deadlock could be resolved. As a variant the importance of supervision was expressed:

But I don’t think I would have done it without supervision, I realize now afterwards when I talk about this … because otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to endure this, otherwise I probably would have tried to bring it to an end, change the setting, change the time or do whatever, since it was unbearable. [George]

For George, supervision made it possible to protect the therapeutic framework and prevent him from taking desperate measures, i.e. “doing whatever” in order to bear the unbearable.

The overall change from experienced loss of agency and reflective capacity to a constructive role differed among the therapists. They could experience that they themselves broke the deadlock, that the deadlock could be resolved by their and their clients’ joint efforts, or that external factors contributed to the resolution. Boris described how the deadlock ended when he disclosed his personal experience to the client:

I thought it was very much the patient’s fault … It’s just by routine that he comes to me … but then I realized I have to analyze myself a little as well, what is my role, what am I doing. And then I realized, oh my God, I have to … talk about what’s going on. I have to bring it up. … And then there was a very good response … he was able to agree with my description of the situation. And then the deadlock was broken. [Boris]

Initially, Boris blamed his client for the impasse, but by gaining insight and taking responsibility for his contribution to the relationship, the therapist and client met in a shared understanding.

Finding oneself as a therapist could happen in different ways, but implied that the therapists found individual understanding of their experiences of the deadlock. In this process, a creation of meaning had taken place. This could include understanding how the deadlock had emerged, finding an empathetic stance toward the client, or detecting the client’s progress in the therapy:

And so, in the last session, it comes to light that she has felt sorry for me for not being able to understand. That I am so stupid, that I haven’t understood. And you know, for me, it has been my largest blind spot, because no one has ever felt sorry for me … what a fantastic declaration of love … so this is what happened, we hugged each other and she laughed and it was liberating, but it had been ghastly. [Anne]

Anne described how her understanding of the client’s way of relating became “liberating”, allowing her to escape from being stuck in a situation experienced as “ghastly.” Frustration about not understanding was expressed in self-reproach over being “stupid”. The shift of focus from her experienced personal shortcoming to seeing and appreciating the client’s care for her enabled them to meet.

Constitutive facets of the deadlock phenomenon

The five superordinate themes presented above do not form a chronological course of events or a process line, as the included experiences were described as possible to occur simultaneously. Accordingly, the therapists could experience the deadlock as both unendurable and necessary, and the process of losing oneself as a therapist could occur simultaneously with finding oneself as a therapist. Furthermore, the same emotional reaction could have different meanings depending on the context. For example, feelings of anger toward the client could belong to unwelcome feelings and wishes when the therapist described supervision as necessary for handling the anger and being able to continue with the therapy. However, the same emotional reaction could be part of losing oneself as a therapist if the anger triggered the therapist to act out and experience that it was impossible to continue the therapy. The quality of something elusive and incomprehensible was present in all other superordinate themes, thus constituting the core and distinctive aspect of the experience of deadlock (see ). The unformulated and not yet apprehensible experience of unfulfilled expectations of closeness and connection was indirectly expressed in the therapist’s confusion and dissatisfaction with the distance in the therapeutic relationship. In the experience of unwelcome feelings and wishes, something unformulated and not apprehensible could appear in anger, guilt, frustration, and in the therapist’s tiredness. In losing oneself as a therapist the unformulated appeared in the therapists’ self-doubt and loss of ability to think about the therapy process. When the therapist experienced finding oneself as a therapist, the elusive and unformulated started to be apprehensible, articulated, and meaningful in different ways.

Discussion

The therapists in our study experienced deadlock as a negative process, blocking the progress of therapy, as also previously described in the literature (Moltu & Binder, Citation2011; Moltu et al., Citation2010; Rosenfeld, Citation1987; Safran, Citation2002). At the same time they regarded deadlock as an inevitable and necessary part of the therapeutic process, something they needed to contain and work through (cf., Hartley, Citation2004; Omer, Citation2000). At the core of deadlocks we found therapists’ unfulfilled expectations of closeness and connection. The universal human striving for intimacy and attachment, despite the impossibility of sustaining them, is also the starting point for Elkind’s (Citation1992) seminal work on resolving impasses in therapeutic relationships. In our study, the therapists’ frustrated relational expectations and lack of contact evoked negative feelings toward their clients. As noted by Omer (Citation2000), therapists experiencing troubles in the therapeutic relationship tend to attribute negative characteristics and an ineradicable pathology to their clients. Karlsson (Citation2004) observed that therapists experiencing being trapped in an impasse can consider the client impossible to reach. In our study, blaming the client was in conflict with the therapists’ wish to be special for the client, and was followed by not understanding, being confused, angry and feeling worthless as a therapist (cf., Hartley, Citation2004; Hill et al., Citation1996). Losing agency and a therapeutic stance was so stressful and overwhelming that the therapists occasionally tuned out psychologically or dissociated. In a study of therapist effects, Nissen-Lie et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated that a combination of self-doubt as a therapist with a high degree of self-affiliation as a person was associated with a better outcome when confronted with difficulties in practice. In our study, the deadlock situation seems to have contributed to blurred borders between the professional and the private self. On the other hand, the therapists’ self-doubt could be one of the starting points for their self-reflection. In different ways, all the therapists struggled to formulate and make sense of their elusive and incomprehensible experiences. In each therapist-client dyad, the experience of deadlock had specific and unique qualities. As described previously by Whitaker et al. (Citation1950), the qualities of the psychotherapeutic impasse depend upon the dynamics of the client and the therapist. The pattern and duration of the deadlock and how it was resolved (or not) varied from case to case. Furthermore, it was impossible for the therapists to identify the point in time when the deadlock started: the impasse could be first identified when the therapist felt lost and no longer had the ability to process what had been communicated in the therapist-client dyad.

In only one case did the therapist describe the therapeutic process coming to a standstill due to the participants’ mutual idealization. One of the potential origins of setbacks in psychotherapy is when the therapeutic relationship is used for both participants’ narcissistic gratification (Leiper & Kent, Citation2001). Closely related is an erotic impasse between the participants, as described in a case study by Davies (Citation2003). However, none of the therapists in our study described deadlock caused by sexual attraction in the therapeutic relationship. Possibly, impasses involving positive feelings between the client and the therapist are more seldom reported as they might conflict with therapeutic ideals and social desirability. Nevertheless, all the therapists in our study more or less explicitly experienced deadlock as challenging their ideals of always having endurance, seeing clearly, being understanding and able to face everything that emerged in therapy. This resulted in questioning of one’s competence, experiencing oneself as a failure, and in frustration about being incapable or incompetent. Previously, Leiper and Kent (Citation2001) described how impasses undermine the therapists’ self-confidence and evoke feelings of shame and guilt about not being able to help, partly in parallel to the clients’ shame at their failure to cope without help. These feelings make it even more difficult to recognize and acknowledge setbacks in psychotherapy, potentially contributing to a vicious circle of losing the therapeutic stance and agency, and of new enactments.

The elusive and incomprehensible quality of the deadlock phenomenon was connected with the therapists’ experience of something unformulated and not yet apprehensible, like a presence of something absent. Unformulated experiences entail the possibility of integration and giving meaning to not-yet-discerned aspects of the client’s problem and the therapeutic relationship. In this context, it is striking how the various descriptions and examples of deadlocks (including the word “deadlock” itself) are metaphors (“stop of flow,” “dead end,” “spinning wheels,” etc.). The experience of deadlock cannot be formulated and understood until the therapeutic relationship allows enough safety for symbolic thinking on metaphor-saturated experiences (Stern, Citation2010).

In times of deadlock, the therapeutic relationship could take the form of collusion or complementarity. Losing oneself as a therapist could involve tacit agreement about avoiding specific content in therapy and the joint creation of a “hopeless therapeutic narrative” (cf., Omer, Citation2000). Elkind (Citation1992) linked therapeutic impasses with the client’s and the therapist’s collusive resistance to sharing painful experiences. Accordingly, Karlsson (Citation2004, p. 567) defined collusion as “a resistance between therapist and patient in which the transference and countertransference become interlocked in a tacit agreement to avoid a mutually fantasized catastrophe.” Losing oneself as a therapist could also involve getting stuck in complementary roles, when one’s position was defined by the other’s, when there was a disagreement about who was doing what to whom, and both parties could experience themselves as being negatively treated by the other – described by Benjamin (Citation2009) as the structure for all relational breakdowns. Finding oneself as a therapist required finding a third position, where it was possible to think and feel together and not just respond to each other. According to Benjamin (Citation2009) this “shared third” – where it is possible to identify with the client without losing one’s own subjective perspective – is crucial for resolving deadlocks. When the therapist and the client can leave their power struggle and begin to meta-communicate, they can return to reciprocity and acknowledgment of each other (Aron, Citation2006). This requires that the therapists can identify and acknowledge their own contribution to the breakdown of collaboration (cf., Leiper & Kent, Citation2001; Omer, Citation2000; Safran & Kraus, Citation2014). In our study, the therapists generally sought support and guidance in theoretical knowledge during the impasse, and as a variant looked for supervision. Thus, not only a witness (cf., Moltu & Binder, Citation2011) but also a theory can play the role of “the third” outside the immediacy of what is going on in the sessions.

A growing body of evidence demonstrates that alliance ruptures, impasses, and transference–countertransference enactments are inevitable in therapy. Rupture repair is related to favorable outcomes. Furthermore, specially designed training programs have been shown to enhance the therapists’ abilities to detect and work constructively with alliance ruptures, negative therapeutic processes, and impasses (Safran & Kraus, Citation2014; Safran et al., Citation2014). Still, the existing culture of shame makes it hard for therapists to admit difficulties in therapies and their own contributions to negative processes (Leiper & Kent, Citation2001; Nathanson, Citation1992). In our study, the therapists’ ideal self-image could lead to experiencing deadlock as a failure and something shameful, even if they typically regarded deadlock as an inherent part of therapeutic processes. All of them described longer periods of deadlock as extremely frustrating, painful, and angst-provoking. Therapeutic impasses and deadlocks seem to be common but elusive phenomena, associated with shame and guilt. Consequently, knowledge of how therapists experience and deal with deadlock has to be more widely diffused and should become a natural part of psychotherapy education and training.

As observed by Kantrowitz (Citation1993) only when the impasse is resolved does it become possible to understand the dynamic resulting in the collapse. Unresolved impasses usually end with dropout from treatment and the therapists’ attempts to understand what happened must remain speculative. (However, see a study by Hill et al., Citation1996 of how therapists with various theoretical orientations tried to understand deadlocks ending in the termination of long-term psychotherapy.) Unrecognized and unresolved deadlocks might also result in treatments continuing for years and years with no sense of progress (Ehrenberg, Citation2000). For natural reasons, no such case of unrecognized deadlock and endless treatment was represented in our material.

To conclude, deadlocks in psychotherapy are common and ought to be addressed in training and research. They are opportunities for the therapist’s self-reflection and improvement of therapeutic skills. Resolved and non-resolved deadlocks in psychotherapy can potentially lead to good and bad outcomes, respectively. Therapists need to be observant of their experiences of deadlock and talk to others about them. In order to do this, we need to counteract the culture of shame and self-blame, and to disseminate the knowledge of deadlocks as natural phenomena in the therapy process that can be recognized, addressed, and worked with. An increased awareness of how therapists experience, create understanding of and work with deadlocks might contribute to improved therapeutic skills, and ultimately might prevent therapy dropout and non-beneficial outcomes. As one of the interviewed therapists put it:

“Deadlock” is really quite apposite, because I think it is what life itself is about in some way … Deadlocks are an important process, I think. Because it is there, maybe, that your trust in another human being can increase. [Diane]

Strengths, Limitations, and Further Research

The main strength of this study is the rigorous application of a well-established qualitative methodology in order to build bridges between the therapists’ experiential knowledge of cases of deadlock, and systematic empirical research. The participants were self-selected therapists who had a personal and professional interest in the phenomenon in focus. Only in two of the nine presented cases was the deadlock not fully resolved. It is possible that important information on unresolved impasses could be collected from therapists who chose not to participate. Thus, the therapists’ attempts to retrospectively understand unresolved deadlock is an important area for further research.

The choice of psychodynamic therapists was guided by our assumption that this theoretical orientation places particular emphasis on what happens within and between both participants in the therapeutic process. We were interested in how experienced therapists perceived and made sense of such experiences. Thus, further research is needed on experiences of deadlock among therapists with other orientations, as well as novice and inexperienced clinicians. Likewise, the clients’ experiences of therapeutic impasses deserve further research.

When inviting the participants and conducting the interviews the authors avoided specifying the notion of deadlock, opening space for the therapists’ own understanding of the phenomenon. Still, it is possible that our pre-understanding influenced the data collection and analysis, despite our attempts to maintain an attitude of naivety. However, the cyclical approach to bracketing contributed to the authors’ reflective activity, deepening the understanding of the deadlock phenomenon (Fischer, Citation2009; Smith et al., Citation2009). When conducting the present study, the authors functioned as an analytic “third” to each other, auditing each step of the data analysis and increasing awareness of each other’s viewpoints and emotional reactions. At the same time, we observed parallel processes, similar to those when unnoticed difficulties in the therapeutic relationship are enacted in the therapist-supervisor relationship (McNeill & Worthen, Citation1989; Searles, Citation1955): the interviewer could feel like the described client; the impasse could be enacted in the interplay between the interviewer and the respondent; and the interviewer could identify with the respondent during audits with the first author. When conducting the study, the authors could experience deadlocks in their analytic work and react with anger, confusion, shame, and guilt. These experiences contributed to capturing different facets of the phenomenon in focus, especially the distinctive aspect of something elusive and incomprehensible.

Practical Implications

Therapeutic impasses and deadlocks seem to be common, but elusive, shame- and guilt-associated phenomena. Deadlocks are opportunities for the therapist’s self-reflection and improvement of therapeutic skills. In order to contribute to better preconditions for therapeutic progress therapists need to be observant of and talk to others about their experiences of deadlock. The knowledge of deadlocks as natural phenomena in the therapy process has to be included as an integral part of psychotherapy education and training.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrzej Werbart

Andrzej Werbart, PhD, is a professor of clinical psychology at the Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, Sweden. He is psychoanalyst in private practice and training and supervising analyst at the Swedish Psychoanalytical Society. His research interests include process and outcome studies, as well as the patients’ and the therapists’ perspective on psychotherapy. He is the author of several publications in the field of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy research.

Emma Gråke

Emma Gråke, MSc, is a licensed psychologist with experience from working in both public and private sectors. Her interests include difficulties and facilitation in the therapeutic process and the therapeutic relationship, and factors that could influence them. She has a M.F.A. from the Royal University College of Fine Arts in Stockholm.

Fanny Klingborg

Fanny Klingborg, MSc, licensed psychologist working with attachment and mentalization based treatment in trauma-related disorders with youths and their closest network. Her theoretical interests include existential, psychodynamic and relational literature and she has a background in arts and literature.

References

- Aron, L. (2006). Analytic impasse and the third: Clinical implications of intersubjectivity theory. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 87(2), 349–368.

- Atwood, G. E., Stolorow, R. D., & Trop, J. L. (1989). Impasses in psychoanalytical therapy: A royal road. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 25(4), 554–573.

- Benjamin, J. (2009). A relational psychoanalysis perspective on the necessity of acknowledging failure in order to restore the facilitating and containing features of the intersubjective relationship (the shared third). International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 90(3), 441–450.

- Bernstein, P. M., & Landaiche, N. M. (1992). Resistance, counterresistance, and balance: A framework for managing the experience of impasse in psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 22(1), 5–19.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginner. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Breakwell, G. M., Smith, J. A., & Wright, D. B. (2012). Research methods in psychology. London, UK: Sage.

- Davies, J. M. (2003). Falling in love with love: Oedipal and postoedipal manifestations of idealization, mourning and erotic masochism. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 13(1), 1–27.

- Ehrenberg, D. B. (2000). Potential impasse as analytic opportunity: Interactive considerations. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 36(4), 573–586.

- Elkind, S. N. (1992). Resolving impasses in therapeutic relationships. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Fischer, C. T. (2009). Bracketing in qualitative research: Conceptual and practical matters. Psychotherapy Research, 19, 583–590.

- Gabbard, G. O. (2020). The role of countertransference in contemporary psychiatric treatment. World Psychiatry, 19(2), 243–244.

- Gold, J., & Stricker, G. (2011). Failures in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(11), 1096–1105.

- Halvorsen, M. S., Benum, K., Haavind, H., & McLeod, J. (2016). A life-saving therapy: The theory-building case of “Cora”. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 12(3), 158–193.

- Hartley, J. F. (2004). An examination of therapists’ experience of impasse in psychological therapy. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Leeds, Department of Clinical Psychology. Retrived February 1, 2018, from. http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/4188

- Hill, C. E., Nutt-Williams, E., Heaton, K. J., Thompson, B. J., & Rhodes, R. H. (1996). Therapist retrospective recall of impasses in long-term psychotherapy: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(2), 207–217.

- Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., Hess, S. A., Knox, S., Williams, E. N., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 196–205.

- Høgland, P. (2014). Exploration of the patient – therapist relationship in psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(10), 1056–1066.

- Kantrowitz, J. L. (1993). Impasses in psychoanalysis: Overcoming resistance in situations of stalemate. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 41(4), 1021–1050.

- Karlsson, R. (2004). Collusions as interactive resistances and possible stepping-stones out of impasses. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 21(4), 567–579.

- Lambert, M. J., & Barley, D. E. (2001). Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(4), 357–361.

- Larkin, M., Watts, S., & Clifton, E. (2006). Giving voice and making sense in interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 102–120.

- Leiper, R., & Kent, R. (2001). Working through setbacks in psychotherapy: Crisis, impasse and relapse. London, UK: Sage.

- Lilliengren, P., & Werbart, A. (2010). Therapists’ view of therapeutic action in psychoanalytic psychotherapy with young adults. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(4), 570–585.

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Maldonado, J. L. (1984). Analyst involvement in the psychoanalytical impasse. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 65, 263–271.

- Malterud, K. (2001). Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet, 358(9280), 483–488.

- McLeod, J., & Sundet, R. (2020). Working with stuckness in psychotherapy: Bringing together the bricoleur model and pluralistic practices. In T. G. Lindstad, E. Stänicke, & J. Valsiner (Eds.), Respect for thought: Jan Smedslund’s legacy for psychology (pp. 361–376). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- McNeill, B. W., & Worthen, V. (1989). The parallel process in psychotherapy supervision. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 20, 329–333.

- Moltu, C., & Binder, P. E. (2011). The voices of fellow travelers: Experienced therapists’ strategies when facing difficult therapeutic impasses. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 50(3), 250–267.

- Moltu, C., Binder, P.-E., & Nielsen, G. H. (2010). Commitment under pressure: Experienced therapists’ inner work during difficult therapeutic impasses. Psychotherapy Research, 20(3), 309–320.

- Mortari, L. (2015). Reflectivity in research practice: An overview of different perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(5), 5.

- Nathanson, D. L. (1992). The nature of therapeutic impasse. Psychiatric Annals, 22(10), 509–513.

- Nissen-Lie, H. A., Rønnestad, M. H., Høglend, P. A., Havik, O. E., Solbakken, O. A., Stiles, T. C., & Monsen, J. T. (2017). Love yourself as a person, doubt yourself as a therapist? Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 48–60.

- Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2011). Evidence-based therapy relationships: Research conclusions and clinical practices. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 98–102.

- Omer, H. (2000). Troubles in the therapeutic relationship: A pluralistic perspective. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(2), 201–210.

- Pietkiewicz, I., & Smith, J. A. (2014). A practical guide to using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in qualitative research psychology. Czasopismo Psychologiczne – Psychological Journal, 20, 7–14.

- Råbu, M., Halvorsen, M. S., & Haavind, H. (2011). Early relationship struggles: A case study of alliance formation and reparation. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 11(1), 23–33.

- Roos, J., & Werbart, A. (2013). Therapist and relationship factors influencing dropout from individual psychotherapy: A literature review. Psychotherapy Research, 23(4), 394–418.

- Rosenfeld, H. (1987). Impasse and interpretation: Therapeutic and anti-therapeutic factors in the psychoanalytic treatment of psychotic, borderline and neurotic patients. London, UK: Routledge.

- Safran, J. D. (2002). Impasse and transformation: Negotiating ruptures in the therapeutic alliance. In T. Scrimali & L. Grimaldi (Eds.), Cognitive psychotherapy toward a new millennium (pp. 81–84). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Safran, J. D., & Kraus, J. (2014). Alliance ruptures, impasses, and enactments: A relational perspective. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 381–387.

- Safran, J. D., Muran, J. C., & Shaker, A. (2014). Research on therapeutic impasses and ruptures in the therapeutic alliance. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 50(1–2), 211–232.

- Searles, H. F. (1955). The informational value of the supervisor’s emotional experiences. Psychiatry, 18(2), 135–146.

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, method and research. London, UK: Sage.

- Stern, D. B. (2010). Partners in thought: Working with unformulated experience, dissociation and enactment. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Suchet, M. (2015). Impasse-able. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 25(4), 405–419.

- Thomas, D. R. (2017). Feedback from research participants: Are member checks useful in qualitative research? Qualitative Ressearch in Psychology, 14(1), 23–41.

- Tryon, G. S., & Winograd, G. (2011). Evidence-based psychotherapy relationships: Goal consensus and collaboration. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 50–57.

- von der Lippe, A. L., Monsen, J. T., Rønnerstad, M. H., & Eilertsen, D. E. (2008). Treatment failure in psychotherapy: The pull of hostility. Psychotherapy Research, 18(4), 420–432.

- Werbart, A., Annevall, A., & Hillblom, J. (2019a). Successful and less successful psychotherapies compared: Three therapists and their six contrasting cases. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 816.

- Werbart, A., von Below, C., Brun, J., & Gunnarsdottir, H. (2015). “Spinning one’s wheels”: Nonimproved patients view their psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 25(5), 546–564.

- Werbart, A., von Below, C., Engqvist, K., & Lind, S. (2019b). “It was like having half of the patient in therapy”: Therapists of nonimproved patients looking back on their work. Psychotherapy Research, 29(7), 894–907.

- Whitaker, C. A., Warkentin, J., & Johnson, N. (1950). The psychotherapeutic impasse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 20(3), 641–647.

- Williams, E. N., & Morrow, S. L. (2009). Achieving trustworthiness in qualitative research: A pan-paradigmatic perspective. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 576–582.

- Wolf, A. W., Goldfried, M. R., & Muran, J. C. (2017). Therapist negative reactions: How to transform toxic experiences. In C. E. Hill & L. G. Castonguay (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others? Understanding therapist effects (pp. 175–192). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Yerushalmi, H. (2015). Impasses in the relationship between the psychiatric rehabilitation practitioner and the consumer: A psychodynamic perspective. Journal of Social Work Practice, 29(3), 355–368.