ABSTRACT

Self-contempt may be a frequent but overlooked clinical phenomenon, associated with a number of psychological problems such as increased sadness and shame. It was shown that self-contempt interferes with productive emotional processing and the quality of therapeutic alliance. This study aims to develop a reliable measure of expressed self-contempt given that a previous three-point assessment may be too restrictive in range, resulting in non-significant results. Thus, the present study applied an extended observer-rated scale to different participant groups in different contexts. This explorative phase focuses on a sample of N = 61 participants divided into three groups, including n = 20 controls, n = 21 patients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorderand n = 20 patients with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Levels of self-contempt are compared between the groups and are associated with symptom indicators. Reliability of the instrument is analysed using inter-rater reliability and internal consistency, which are sufficient. The level of expressed self-contempt is not related to symptom intensity. Patients with borderline personality disorder do not express more self-contempt than the other groups. While further research should establish full validity of the scale, reliability is satisfactory and the use of the scale can be recommended.

Background

Self-contempt, or contempt towards the self, may be understood as a secondary emotional process in response to a more primary maladaptive emotion (Greenberg & Paivio, Citation1997a). Self-contempt may be understood as an expression of rejecting anger, one that is oriented towards the self, marked by a particular coldness, aloofness and fierce rejection (Kramer, Renevey, & Pascual‐leone, Citation2020; Pascual-Leone, Citation2009; Pascual-Leone, Gilles, Singh, & Andreescu, Citation2013). It is conceptualized as a special sort of contempt in which a person evaluates his/her real self as despicable, as significantly lower than the standards supposed by his/her ideal self (Miceli & Castelfranchi, Citation2018). It could thus be understood as the emotional process underlying the potentially most destructive part of self-criticism. Studying self-contempt becomes of central clinical relevance, as it seems is an important feature of psychopathology, while it can easily be overlooked. We will define self-contempt as an emotion related to a cold rejective feeling of self-deficiency implying anger and disgust towards the self. This self-rejective process involves emotional, cognitive and biological activations. A self-contemptuous individual treats oneself as disgusting and unworthy. This process negatively impacts their self-esteem or interferes with self-compassion, which may lead to further cognitive-representational, as well as interpersonal difficulties. These structural and functional aspects of self-contempt may speak for observing the phenomenon as it unfolds in a therapeutic session.

Self-contempt in psychotherapy research

In the literature, various attempts have been made to assess self-contempt. For example, in a study evaluating patients’ self-contempt specifically related to having a mental illness, Rüsch et al. (Citation2019) used a self-reported scale adapted from a measure on shame. In this context, self-contempt is the emotional component of self-stigmatizing thinking and behaviour. They observed that self-contempt for having a mental illness is a predictor of suicidality in patients; these patients presented with mostly affective disorders, anxiety spectrum disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Rüsch et al., Citation2019). Rüsch et al. (Citation2019) noted that the effect of self-contempt was significant after adjusting for hopelessness, which suggests a direct pathway from self-contempt to suicidality and concludes that the expression of self-contempt should be taken into account by clinicians (Rüsch et al., Citation2019, p. 1057).

Emotions are essential in psychotherapy (Greenberg & Paivio, Citation2003; Magnavita, Citation2006) because they are considered to be at the core of the therapeutic process (Greenberg, Citation1979) and to be beneficial across several models of psychotherapy (Greenberg & Pascual-Leone, Citation2006). However, not all emotional expressions are therapeutic and productive (Auszra & Greenberg, Citation2007; Pascual-Leone, Citation2018). Peluso and Freund (Citation2018) conducted a meta-analysis on the association between emotional expression and psychotherapy outcome and showed a moderate link, potentially conflating effects related to expression of productive and less productive emotions. In addition, they concluded that “external observational coding can often yield superior results” (Peluso & Freund, Citation2018, p. 468). This argument may specifically speak to the assessment of self-contempt as a multilevel activated process of self-rejection, for which the observed behaviour needs to be put to light. Using such observer-rated methodology, Whelton and Greenberg (Citation2005) observed the process of self-criticism, as well as its effect on the self, in an experiential two-chair dialogue. Their objective was to test Greenberg’s (Citation1990) hypothesis that self-contempt would be greater among self-critical individuals who were vulnerable to depression than among controls (Greenberg, Citation1990). They showed that the self-critics’ selves are more prone to experience harsh feelings when facing criticism, compared to controls, and they concluded that “what has been internalized is not just the content of the criticism, but its emotional tone of contempt and disgust” (Whelton & Greenberg, Citation2005, p. 1593). This study suggests that (a) the experiential two-chair dialogue focusing on self-criticism may be an excellent occasion to observe self-contempt as it unfolds (during the expression of the self-critical voice) and (b) self-contempt may be best assessed using a differentiated observer-rated method.

Extending this line of research, Kramer and Pascual-Leone (Citation2016) examined the role of emotion in the elaboration of self-criticism in individuals with anger problems, again using an experiential two-chair dialogue as context of assessment. They compared 23 anger-prone undergraduate students to 22 control students on process indices of emotions – contempt, fear, shame, anger and global distress – in response to self-critical content. They used the two-chair dialogue task in order to study moment by moment the process of working through self-criticism. Their objective was to examine the process of self-hate which states that individuals with maladaptive anger use more contempt when expressing self-criticism than controls. Kramer and Pascual-Leone (Citation2016) developed an observer-rated assessment measuring self-contempt, which consisted of an independent three-point Likert-type scale measuring the degree of contempt from 0 (= absent) to 2 (= fully present): this scale was developed to assess self-contempt on a video recording. They confirmed that anger-prone participants expressed more self-contempt than controls during the self-criticism part of their two-chair dialogue. The authors were thus able to state that anger-prone participants, when compared to controls, “expressed more self-hate in the form of contemptuousness” (Kramer & Pascual-Leone, Citation2016, p. 326): it suggests a crucial link between anger, hate, contempt and elements of the self. According to Kramer and Pascual-Leone (Citation2016), the main limitation of their study is that it was not conducted in a clinical context. We would add that a three-point Likert-type scale may not be sufficient to capture the differentiated picture of self-contemptuous expressions.

Sallin et al. (Citation2021) examined the role of expressed self-contempt in brief therapy for borderline personality disorder (BPD). Borderline personality disorder was selected as it was understood as being associated with self-contemptuous processes. Their objective was to study the association between self-contempt and core symptoms of BPD, as well as the progression of expressed self-contempt during treatment and its (potentially detrimental) effect on the therapeutic alliance and the outcome of the brief treatment. Sallin et al. (Citation2021) analysed 50 patients from an ambulatory outpatient center. The data were taken from a previous treatment trial by Kramer et al. (2014; unpublished). Sallin et al. (Citation2021) analysed video and audio recordings of sessions; per patient, three sessions were coded: at the beginning, middle and end of the brief treatment. Of note, the coding method was applied to both video and audio data within this sample, which was discussed by the authors as a feasible methodological adaptation of the original scale.

Sallin et al. (Citation2021) found an association between the intensity of expressed self-contempt and the level of borderline symptoms at baseline. They did not find any change in self-contempt across the brief treatment, but they found that expressed self-contempt negatively predicted the working alliance as evaluated by patients, while it positively predicted the working alliance as evaluated by therapists (Sallin et al., Citation2021). Finally, the authors observed no association between self-contempt measures and outcomes in their sample (Sallin et al., Citation2021). This study was the first to assess self-contempt in a psychotherapy context and brought forward important elements for the understanding of this self-rejecting emotion process. It showed that self-contempt is central to borderline personality disorder because of known problematics of instability in interpersonal relationships, affects, self-image, as well as self-aversive behaviours and affects (Brown, Linehan, Comtois, Murray, & Chapman, Citation2009; Gunderson, Citation2011; Winter, Bohus, & Lis, Citation2017). The newest revision of the international classification of diseases (11th ed; ICD-11; World Health Organization, Citation2019) includes a disturbed view of the self, characterized by self-contempt, as a suggested feature of severe personality disorder (World Health Organization, Citation2019). Furthermore, it was discussed that individuals with a traumatic background might have a higher sense of threat – both from other persons and from themselves – which induces self-contempt (Gilbert & Tirch, Citation2009), and traumatic experience is common in borderline personality disorder patients (Yen et al., Citation2002; Zanarini & Frankenburg, Citation1997).

Expressed self-contempt was differentially related to the therapeutic alliance in the Sallin et al.’s (Citation2021) study, which may relate to the findings of Muntigl, Horvath, Bänninger-Huber, and Angus (Citation2020) who showed that therapists react differently to self-critical expressions according to the type of self-criticism used. Self-criticism, according to Muntigl, Horvath, Bänninger-Huber, and Angus (Citation2020), can be either a strong self-condemnation implying a negative evaluation of the self (ie akin to a self-contemptuous process) or a more self-reflective evaluation, which does not imply the same negative evaluation (Muntigl, Horvath, Bänninger-Huber, & Angus, Citation2020). What is particularly important in their study is that they focused on showing how optimistic responses from therapists can help change self-critical talk into a more productive and positive way (Muntigl, Horvath, Bänninger-Huber, & Angus, Citation2020). It appears that the self-contempt that accompanies self-criticism is a main factor in maintaining self-critical beliefs (Kannan & Levitt, Citation2013). These results highlight the possible implications of expressed self-contempt on several dimensions of psychotherapy, as well as its potential role in a productive process of change, if appropriately reflected by the therapist, moving from maladaptive to more adaptive emotional states.

Despite the importance of the work by Sallin et al. (Citation2021), their study presents limitations: the authors point out that the three-point Likert-type scale of expressed self-contempt might be too restrictive in range to be able to code the differentiated manifestations of self-contempt. This problem may have led to non-significant findings when it came to assess the possible changes over the course of psychotherapy. A comparative control group was also missing in their study.

Present study

The present study aims to take a step back, building on the results from the study by Sallin et al. (Citation2021), and aims at developing an extended version of an observer-rated scale of expressed self-contempt, to be applied in the clinical context. We hope that the extension from a three-point to five-points Likert-type scale would help grasp the full picture, with all the nuances, of the phenomenon. In order to do so, the present study develops such a scale, with the definition of specific anchors and a coding procedure.

The main research question is that expressed self-contempt can be reliably assessed using a five-point Likert-type scale. Mainly, we aim at providing benchmark indicators of the level of expressed self-contempt at the beginning of any treatment, in two different clinical groups – patients with borderline personality disorder and major depression, and a healthy control group undergoing experiential two-chair dialogue. We hope that such benchmarks may be helpful for further research focusing on self-contempt as a multilevel phenomenon.

Methods

Participants

Three groups of participants took part in the study. First, n = 20 undergraduate students were recruited as healthy controls. Then, n = 21 patients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder and n = 20 patients with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder were recruited. The data for healthy controls come from a recent study comparing daily life and an analogue psychotherapy session through an ecological momentary assessment of emotional processing (Beuchat et al., Citation2021). The data for patients with borderline personality disorder group come from the previously described study by Sallin et al. (Citation2021). Finally, the data for patients with major depressive disorder group come from a study estimating the efficacy of adjunctive psychodynamic psychotherapy compared to the usual psychiatric and pharmacological treatment (de Roten et al., Citation2017). The setting was different across the groups as the healthy controls were undergoing a self-critical two-chair dialogue, while patients with borderline personality disorder and major depressive disorder groups were in the first session of psychotherapy. In order to establish baseline levels of self-contempt with the aim of benchmarking, we focused on the initial in-person contact for all participants.

Across the groups, the participants were on average 37.8 years old (SD = 16.46) and were mostly females (72%, n = 44). There were notable differences among groups in terms of age. Healthy controls were, on average, 23.05 years old (SD = 1.85). Patients with borderline personality disorder were on average 32.43 years old (SD = 6.86), and patients with major depressive disorder were 57.68 years old (SD = 10.53) on average. Healthy controls were mostly females (75%, n = 15), similar to patients with borderline personality disorder (76%, n = 16) and patients with major depressive disorder (65%, n = 13). The mean level on the borderline symptom list (BSL; Bohus et al., Citation2009) was 1.76 (SD = .93); these data were only available for patients with borderline personality disorder. The mean level on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery & Åsberg, Citation1979) was 30.65 (SD = 5.90), and these data were only available for patients with major depressive disorder. The mean level on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; American Psychiatric Association, Citation1994, pp. 143–147) was 49.82 (SD = 12.34) for patients with borderline personality disorder and major depressive disorder groups together, 57.66 (SD = 8.14) for patients with borderline personality disorder and 41.16 (SD = 10.25) for patients with major depressive disorder. These numbers are reported in .

Table 1. Demographics and symptom scales.

Measures

Outcome questionnaire (Lambert et al., Citation1996): 45-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the symptomatic level; this is a widely used questionnaire to assess the outcome of a psychotherapeutic treatment, in the form of a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. The internal consistency reliability of the outcome questionnaire ranges from .70 to .92 for the subscales, while the total score of the OQ has a reliability score of .93 as measured with Cronbach’s alpha (Lambert et al., Citation1996). Test–retest reliability ranges from .78 to .82 in the subscales, while the total score of the OQ has a test–retest reliability of .84 (Lambert et al., Citation1996). In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the OQ is of .89.

Borderline Symptom List (BSL 23; Bohus et al., Citation2009): 23-item self-report questionnaire that assesses specific borderline personality disorder symptoms in the form of a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. The internal consistency of the BSL 23 is high, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .97 and test–retest reliability of .82 (Bohus et al., Citation2009). In our sample, the Cronbach’s alpha is of .91.

Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery & Åsberg, Citation1979): it assesses depression symptomatology; this is a depression rating scale computing 10 items, widely used and validated. Interrater reliability of the MADRS ranges from .89 to .97 (Montgomery & Åsberg, Citation1979). In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha of the MADRS is of .88.

Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (Goldman, Skodol, & Lave, Citation1992): a procedure to measure the overall severity of psychiatric disturbances rating patients’ functioning on a scale ranging from 0 to 100. Reliability of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale ranges from .49 to .80 (Goldman, Skodol, & Lave, Citation1992). In our sample, the Cronbach’s alpha score is of .85 for the Global Sssessment of Functioning Scale.

Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Horvath & Greenberg, Citation1989): this self-report questionnaire – brief version – assesses the quality of the working alliance, both from the client and the therapist perspective, using 12 items. The internal consistency, as measured with Cronbach’s alpha, of the working alliance inventory, is .93 (Horvath & Greenberg, Citation1989). In our sample, the WAI is presented with a Cronbach’s alpha of .94.

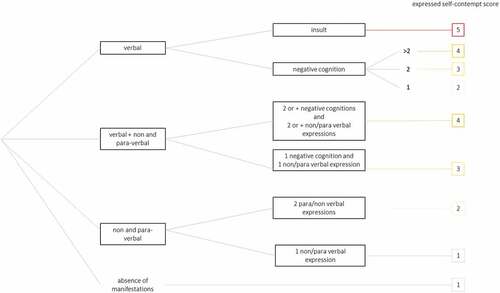

Expressed self-contempt rating scale: we defined and used a five-point Likert-type scale as an improved observer-rated scale for the assessment of expressed self-contempt. We used a coding manual (see ). The manual functions as a decision tree: the rater needs to evaluate verbal and non-/para-verbal manifestations of expressed self-contempt. In the absence of any manifestation, the expressed self-contempt score will be rated 1. In the presence of one non-/para-verbal expression, the score will also be 1. In the presence of verbal and non-/para-verbal expressions, two options are possible: either one negative cognition and one non-/para-verbal expression that lead to a score of 3; or two or more negative cognitions and two or more non-/para-verbal expressions that lead to a score of 4. If only verbal expressions are present, without any non-/para-verbal expressions, the possibilities are multiple: either only negative cognitions are expressed, which will be quantified; one negative cognition leads to a score of 2, two negative cognitions lead to a score of 3, more than two (three or more) negative cognitions lead to a score of 4. Finally, in the presence of an insult, the score will be 5 in any case.

Coders were master and PhD students in psychology who were trained using both the decision tree and a coding manual developed for this purpose, as shown in and exemplified in .

Table 2. Examples of process markers or observable markers for expressed self-contempt ratings.

Procedure

The five points of the expressed self-contempt Likert-type scale were defined based on the three-point Likert-type scale previously developed by Kramer and Pascual-Leone (Citation2016). The objective was to create a more sensitive scale. Whereas the previous scale was constituted of three points that were: 0 = no self-contempt; 1 = moderate self-contempt and 2 = high self-contempt, the new scale was defined as follows: 1 = no expressed self-contempt; 2 = low expressed self-contempt; 3 = moderate expressed self-contempt; 4 = high expressed self-contempt; 5 = extreme expressed self-contempt. Attribution of a self-contempt score was made by observing verbal (insults or negative cognitions) and non-verbal elements, eg raising an eyebrow, or according to Ekman and Friesen (Citation2003), tightening one side of the lip corner (Ekman & Friesen, Citation2003), as well as their occurrences.

We gathered video-taped interviews for the borderline personality disorder group as well as for the control group. We gathered audio-taped interviews for the major depressive disorder group. Two independent raters coded 20 interviews for each group. This allowed us to compare heterogeneous designs because the groups were in different settings (two-chair dialogue experiential task for the control group, psychotherapy intake sessions for the borderline personality disorder and the major depressive disorder groups). Both raters attributed a score – ranging from 1 to 5 – to each session coded. For the statistical analysis, we used these mean scores of expressed self-contempt.

A two-chair dialogue was implemented to assess the control participants. The two chair-dialogue (Greenberg, Citation2015) is a task derived from the empty chair work (Greenberg, Citation1979) that was first developed for a psychotherapeutic use in the context of emotion-focused therapy. In our setting, we used it as an intrapersonal task in which the participants had to picture themselves in the other chair rather than a relative of theirs. As Greenberg (Citation1979) puts it, “the therapeutic task [promotes] experiencing in the one chair and criticisms and projections in the other chair” (Greenberg, Citation1979, p. 319). In order to achieve this, in the control group, the interviewers first asked the participants to remember and relive as vividly as possible a situation of failure that they felt towards themselves. The interviewers then asked them to change chair in order to incarnate the self-critical voice they might have “heard” during the reliving of the failure situation and to picture themselves on the opposite chair. The interviewers asked them to say aloud, while incarnating the critical voice, what the critical voice thought or felt about them in the failure situation. Finally, the interviewers asked the participants to respond to the self-criticism. This emotion-evoking procedure served to code the self-contempt for the moments of the task when the participants were in the critic chair.

In order to explore the reliability of the data and have benchmark indicators for the levels of self-contempt, we assessed reliability using intra-class correlation coefficients and Cronbach’s alpha, in addition to test of normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. We conducted Pearson’s correlations between the levels of self-contempt for each group and compared the levels of self-contempt among the three groups using ANOVA models. All tests were made using SPSS version 27.

Results

Reliability assessment

Kolmogorov–Smirnov’s test of normality was significant for control participants (p = .000) and for patients with major depressive disorder (p = .049) but not for patients with borderline personality disorder (p = .094). This means that only the borderline personality disorder patients’ group had a normal distribution of scores.

Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) estimates and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated based on a mean-rating (k = 2), absolute agreement and two-way mixed-effects model. ICC (2, 2) for the control group was .733 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from .334 to .896 (F (1, 18) = 4.009, p > .001) with a very good internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha =.74. For the borderline personality disorder group, ICC (2, 2) was .576 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from .434 to .688 (F (1,166) = 2.35, p < .000) with a good internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha =.56. For the major depressive disorder group, ICC (2, 2) was .668 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from .537 to .762 (F (1,139) = 3.07, p < .000), with a good internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha =.66. For all three groups together, ICC (2, 2) was .720 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from .653 to .775 (F (3, 325) = 3.57, p < .000) with a very good internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha = .71 (see ).

Table 3. Psychometric properties and validation coefficients of the expressed self-contempt scale.

Based on these results, we can conclude that the reliability of the five-point Likert-type scale of expressed self-contempt is satisfactory.

Links between self-contempt and symptom levels

Pearson correlations between the mean level of expressed self-contempt and symptoms questionnaires were not significant (see ); we found no link between general functioning and the level of expressed self-contempt in the borderline personality group r = .120, p > .05, and we found no link between general functioning and the level of expressed self-contempt in the major depressive disorder group either r = .055, p > .05. For the borderline personality disorder group, we found no link between borderline symptomatology and the level of expressed self-contempt r = −.293, p > .05 nor between outcome and the level of expressed self-contempt r = −.040, p > .05. Finally, for the major depressive disorder group, we found no link between depressive symptomatology and the level of expressed self-contempt r = −.388, p > .05.

Table 4. Pearson correlations between clinical questionnaires and level of expressed self-contempt.

Self-contempt in different groups of participants

Control participants, participants presenting a borderline personality disorder and participants presenting a major depressive disorder vary in their average score of expressed self-contempt as expressed by one-factor inter-group ANOVA F(2, 58) = 60.792, sig = .000 which showed a significant difference between the means. A one-way ANCOVA conducted to compare the score of expressed self-contempt whilst controlling for age showed the same result F(2, 57) = 32.354, sig =.000 (Rsquare = .18).

Post hoc analyses (Tukey HSD) showed that the control group (M = 4.30, SE = .24), p = .000 has a superior mean than the borderline personality disorder group (M = 1.95, SE = .14), p < .05 and the major depressive disorder group (M = 1.81, SE = .13), p < .05. However, borderline personality disorder and major depressive disorder groups do not significantly differ between themselves (p = .831).

We can conclude that patients with borderline personality disorder do not express more self-contempt than patients with major depressive disorder nor than healthy controls in our setting.

Discussion

The present study developed a new observer-rated scale to assess expressed self-contempt in psychotherapy. This study aimed at providing the first reliability data for different groups of participants, in addition to putting forward the first benchmark indicators about levels of self-contempt for each of the participant groups, and exploring links with symptom levels. This observer-rated scale assesses expressed self-contempt using verbal and non-verbal elements in a more sensitive manner than it had been previously done. The objective is to allow a better differentiation between various intensities of self-contempt.

We observe that this scale is reliable, rather easy to apply and does not require any long training. We also observe a general lack of relationships with symptom levels for all three groups of participants studied. There are methodological implications related to the development of this scale: having a reliable measure of expressed self-contempt could help understand several clinical elements of psychological difficulties associated with self-contempt, although there remains an open question about the validity of the scale developed. While of course evaluating psychological difficulties mostly relies on the clinician’s appreciation and experience, having a validated tool to measure self-contempt would represent a potential gain of information and a valuable help.

Because self-contempt appears to be a secondary emotion, one could argue that attending to expressed self-contempt in the session, delicately and appropriately naming it, bears the potential for the client to transform their emotional experience into more primary experiences, for example, the often underlying shame about one’s inadequacy. Indeed, we need to consider Pascual-Leone (Citation2018)’s model of emotion transformation: self-contempt is not explicitly included in this model. However, one adaptive emotion is self-compassion; we argue here that self-contempt represents the act of treating the self harshly and could therefore be a secondary emotional, or maladaptive emotional, reverse side of self-compassion. We could imagine that actively working on self-contempt when it is problematic could help access self-compassion and ignite a specific process of emotion transformation that has not been described more fully so far. For example, self-contempt may be an important clinical manifestation as part of the cluster of anger emotions, but there is some unclarity whether it is a secondary emotional experience or a primary maladaptive experience – in the sense of characterological expressions of trauma-related maladaptive responses directly to specific situations (Greenberg & Paivio, Citation1997b; Pascual-Leone, Gilles, Singh, & Andreescu, Citation2013; Pascual-Leone, Paivio, & Harrington, Citation2016); detailed sequential analyses, using the current scale, could shed light on this question from an empirical viewpoint.

We found in our study that the level of expressed self-contempt in psychotherapy is not related to symptom intensity. This may be a surprising result, given what was found by Sallin et al. (Citation2021) for borderline personality disorder. However, when looking closely at the correlations, we found that the specific symptom measures had small-to-moderate correlations with expressed self-contempt: level of depression correlated with self-contempt at r = .39 in patients with depression and level of borderline symptoms correlated with self-contempt at r = .29 in patients with borderline personality disorder. The absence of significance of these correlations may be due to the small sample sizes. The absence of links may also be interpreted both as an indicator of independence of symptoms from emotion processes and as a lack of validity of the newly developed scale, if these relationships with symptoms were expected. To our knowledge, there is one study on BPD which has found relationships with symptom levels (Sallin et al., Citation2021), so it is premature to conclude about this question.

Establishing benchmark indicators for further research, we explored the differences in levels of self-contempt in two patient groups with healthy controls and found that patients with borderline personality disorder do not express more self-contempt than patients with major depression disorder nor healthy controls. Clearly, this result is dependent on the setting difference between the groups. It suggests that the controls in the two-chair dialogue task – aiming at evoking emotions – elevated the likelihood to have high levels of any emotion being expressed, including self-contempt. This means that the fact of undertaking an experiential task, namely, the two-chair dialogue that provides a productive context to express self-critical elements, probably also provides a productive context to the expression of self-contempt. One implication, so far, may be to recommend that the newly developed five-point rating scale of expressed self-contempt may be applied preferentially to video-data stemming from two-chair dialogues.

The present study did not find any difference in the mean of expressed self-contempt when we compared patients with borderline personality disorder with patients with major depressive disorder. Of note, the ratings for the borderline personality disorder group have been made on video recordings, whereas ratings for the major depressive disorder group have been made on audio recordings only. This questions the relevance of behavioural elements’ analysis in our expressed self-contempt scale, yet we will argue that behavioural features, or facial expressions, in expressed self-contempt may still be of importance. Our study should be replicated in other clinical populations undergoing the two-chair dialogue to be able to draw further conclusions about this.

Limitations

Our study has limitations that must be discussed. The setting of the assessment was different in what regards the recording method between the three groups, precluding a more formal between-group test design. The control group and the borderline personality disorder group were video-recorded, whereas the major depressive disorder group was audio-recorded. This was a choice we made based on the data we had at our disposal. Age difference between the groups may also be a limitation of our study and should be addressed in future studies.

Also, the choice we made of analysing the first session of psychotherapy was relevant for this exploratory benchmarking study but should be complemented by research focusing on the process of change in future studies.

Furthermore, because of the chair dialogue setting that facilitates the expression of self-contempt, the normative sample, or control group, can be expected to have the highest self-contempt out of the three samples. Given that our three samples come from different studies, other analyses than comparing the means should be done in future studies to test mean differences.

One important goal of this study was to examine and establish the interrater reliability of our new scale. While Cronbach’s alpha was generally acceptable, ranging from .56 to .74 across groups, and of .71 considering the three samples together, we need to acknowledge that for two samples, namely the borderline personality disorder group and the major depressive group, Cronbach’s alphas were .56 and .66, respectively. Put simply, Cronbach’s alphas were good in our control group sample and within the three samples together, but remained fair in the other two samples. This may be related to the setting difference in the patient groups and may imply that our scale may be better used in a self-critical two-chair dialogue setting than in a psychotherapy session. Further research is needed to explore this question.

Finally, one limitation of our study that future studies may address is that future studies should be conducted to test the inter-rater reliability between raters who use audiotape and those who use videotape of the same session for rating. Indeed, two groups of raters should ideally rate sessions of patients and control group samples, one based on audio-recordings and the other on video-recordings, and the agreement should be calculated in order to establish the inter-rater reliability separately when audio or video recordings are used.

Conclusions

This study puts forward a newly developed observer-rated scale using a differentiated five-point Likert-type scale, to assess expressed self-contempt in psychotherapy. Reliability and applicability of the scale were confirmed, both for verbal, para-verbal and non-verbal indicators of self-contempt. This may imply that this scale allows a greater understanding and observation of expressed self-contempt for researchers and clinicians.

Self-contempt may be conceptualized as an affective dynamic process of fundamentally rejecting the self and holds a promising role for understanding emotional processing as a mechanism of change explaining the effects of psychotherapy, in particular in severe psychological disorders and those affected by long-standing trauma. Yet, it is often overlooked. A potentially valid and reliable observer-rated measure of self-contempt is an important and useful tool for clinicians and psychotherapy researchers. The first results of this study are thus promising. Thanks to the heterogeneous design, we observed that the context has an impact on the sensitivity of the scale. Indeed, it appears that self-contempt is more easily observed in a two-chair dialogue setting rather than in an early session of psychotherapy; it even seems that expressed self-contempt is present more intensively in these settings.

In the future, our scale may be applied in a more homogeneous and controlled design. It may be interesting to compare healthy controls with patients with borderline personality disorder, both undergoing two-chair dialogue. We also intend to explore whether expressed self-contempt changes over the course of therapy and, if so, whether this change is related to outcome. It would also be necessary to replicate our results with another patient population, for example, patients with pathological narcissism, or with eating disorders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hélène Beuchat

Hélène Beuchat is a PhD student in clinical psychology at the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), University Institute of Psychotherapy (IUP) and at the University of Fribourg (UNIFR). She started her PhD studies after a Bachelor in both psychology and English, followed by a Master in clinical psychology at the University of Lausanne (UNIL). Her work focuses on emotions, borderline personality disorder and mechanism of change.

Loris Grandjean

Loris Grandjean is a young scientist-practitioner psychologist with a passion for integrative clinical practice and research in psychotherapy currently pursuing a Ph.D. in clinical psychology where he investigates the role of emotional arousal in the treatment of clients presenting with a Borderline Personality Disorder. Alongside his research, he is also training to qualify as a psychotherapist.

Nastia Junod

Nastia Junod is a PhD student in neurosciences and pedopsychiatry at the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV). She studied medicine at the University of Lausanne and focused her research on the use of EMA and EEG in psychiatry.

Jean-Nicolas Despland

Jean-Nicolas Despland is a medical doctor, psychiatrist and psychotherapist FMH, full professor at the Faculty of Biology and Medicine of the University of Lausanne and director of the University Institute of Psychotherapy (IUP) of the Department of Psychiatry (CHUV, Lausanne). He is responsible for the coordination of training courses for residents in three main models, psychoanalytic, CBT and systemic psychotherapies. In the field of research, he has received continuous support from the FNRS and other organizations since 1998 and has published more than 250 scientific and clinical articles, as well as several books.

Antonio Pascual-Leone

Antonio Pascual-Leone is a clinical psychologist and associate professor of psychology at the University of Windsor, Canada. He completed his early graduate training in France and then completed his Ph.D. with Les Greenberg at York University. He has published a number of papers on psychotherapy process and outcome, with a special focus on the role of emotion. He currently runs the Emotion Change Lab at the University of Windsor. Dr Pascual-Leone is the current director of the Psychological Services and Research Centre (PSRC). He received training in DBT and CBT treatments and currently runs a private practice in Windsor.

Chantal Martin-Sölch

Chantal Martin-Sölch is full professor of clinical psychology at the Department of Psychology at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. She obtained her PhD from the University of Fribourg in 2002. Her research interests include psychobiology, clinical neuroscience and experimental psychopathology, investigations in psychopathology and psychosomatics, on stress, on reward system and clinical interventions and mindfulness.

Ueli Kramer

Ueli Kramer currently works as Privat-Docent at the Institute of Psychotherapy and the General Psychiatry Service, Department of Psychiatry, University of Lausanne (Switzerland), and at the Department of Psychology, University of Windsor (Canada). He is currently the President of the European Society for Psychotherapy Research (EU-SPR).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV®). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Pub.

- Auszra, L., & Greenberg, L. S. (2007). Client emotional productivity. European Psychotherapy, 7(1), 137–152.

- Beuchat, H., Grandjean, L., Despland, J. N., Pascual‐leone, A., Gholam, M., Swendsen, J., & Kramer, U. (2021). Ecological momentary assessment of emotional processing: An exploratory analysis comparing daily life and a psychotherapy analogue session. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(2), 345–356. doi:10.1002/capr.12455

- Bohus, M., Kleindienst, N., Limberger, M. F., Stieglitz, R. D., Domsalla, M., Chapman, A. L., … Wolf, M. (2009). The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): Development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology, 42(1), 32–39. doi:10.1159/000173701

- Brown, M. Z., Linehan, M. M., Comtois, K. A., Murray, A., & Chapman, A. L. (2009). Shame as a prospective predictor of self-inflicted injury in borderline personality disorder: A multi-modal analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(10), 815–822. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.008

- de Roten, Y., Ambresin, G., Herrera, F., Fassassi, S., Fournier, N., Preisig, M., & Despland, J. -N. (2017). Efficacy of an adjunctive brief psychodynamic psychotherapy to usual inpatient treatment of depression: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 209, 105–113. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.013

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (2003). Unmasking the face: A guide to recognizing emotions from facial clues (Vol. 10). Cambridge: Ishk.

- Gilbert, P., & Tirch, D. (2009). Emotional memory, mindulness and compassion. In Didonna Fabrizio (Ed.), Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness (pp. 99–110). New York: Springer.

- Goldman, H. H., Skodol, A. E., & Lave, T. R. (1992). Revising axis V for DSM-IV: A review of measures of social functioning. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 9.

- Greenberg, L. S. (1979). Resolving splits: Use of the two chair technique. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16(3), 316–324. doi:10.1037/h0085895

- Greenberg, L. S. (1990). Emotion in psychotherapy. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.003303

- Greenberg, L. S. (2015). Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/14692-000.

- Greenberg, L. S., & Paivio, S. C. (1997a). Varieties of shame experience in psychotherapy. Gestalt Review, 1(3), 205–220. doi:10.2307/44394018

- Greenberg, L. S., & Paivio, S. C. (1997b). Varieties of shame experience in psychotherapy. Gestalt Review, 1(3), 205–220. doi:10.2307/44394018

- Greenberg, L. S., & Paivio, S. C. (2003). Working with emotions in psychotherapy (Vol. 13). New York: Guilford Press.

- Greenberg, L. S., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2006). Emotion in psychotherapy: A practice-friendly research review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(5), 611–630. doi:10.1002/jclp.20252

- Gunderson, J. G. (2011). Borderline personality disorder. New England Journal of Medicine, 364(21), 2037–2042. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1007358

- Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(2), 223. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223

- Kannan, D., & Levitt, H. M. (2013). A review of client self-criticism in psychotherapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(2), 166. doi:10.1037/a0032355

- Kramer, U., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2016). The role of maladaptive anger in self-criticism: A quasi-experimental study on emotional processes. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 29(3), 311–333. doi:10.1080/09515070.2015.1090395

- Kramer, U., Renevey, J., & Pascual‐leone, A. (2020). Assessment of self‐contempt in psychotherapy: A neurobehavioural perspective. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 20(2), 209–213. doi:10.1002/capr.12307

- Lambert, M. J., Hansen, N., Umphress, V., Lunnen, K., Okiishi, J., Burlingame, G., & Reisinger, C. (1996). Administration and scoring manual for the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2). Wilmington, DE: American Professional Credentialing Services.

- Magnavita, J. J. (2006). The centrality of emotion in unifying and accelerating psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(5), 585–596. doi:10.1002/jclp.20250

- Miceli, M., & Castelfranchi, C. (2018). Contempt and disgust: The emotions of disrespect. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 48(2), 205–229. doi:10.1111/jtsb.12159

- Montgomery, S. A., & Åsberg, M. (1979). A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry, 134(4), 382–389. doi:10.1192/bjp.134.4.382

- Muntigl, P., Horvath, A. O., Bänninger-Huber, E., & Angus, L. (2020). Responding to self-criticism in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 30(6), 800–814. doi:10.1080/10503307.2019.1686191

- Pascual-Leone, A. (2009). Dynamic emotional processing in experiential therapy: Two steps forward, one step back. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 113. doi:10.1037/a0014488

- Pascual-Leone, A. (2018). How clients “change emotion with emotion”: A programme of research on emotional processing. Psychotherapy Research, 28(2), 165–182. doi:10.1080/10503307.2017.1349350

- Pascual-Leone, A., Gilles, P., Singh, T., & Andreescu, C. A. (2013). Problem anger in psychotherapy: An emotion-focused perspective on hate, rage, and rejecting anger. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 43(2), 83–92. doi:10.1007/s10879-012-9214-8

- Pascual-Leone, A., Paivio, S., & Harrington, S. (2016). Emotion in psychotherapy: An experiential–humanistic perspective.

- Peluso, P. R., & Freund, R. R. (2018). Therapist and client emotional expression and psychotherapy outcomes: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 461. doi:10.1037/pst0000165

- Rüsch, N., Oexle, N., Thornicroft, G., Keller, J., Waller, C., Germann, I., … Zahn, R. (2019). Self-contempt as a predictor of suicidality: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 207(12), 1056–1057. doi:10.1097/nmd.0000000000001079

- Sallin, L., Geissbüehler, I., Grandjean, L., Beuchat, H., Martin-Soelch, C., Pascual-Leone, A., & Kramer, U. (2021). Self-contempt, the working alliance and outcome in treatments for borderline personality disorder: An exploratory study. Psychotherapy Research, 31(6), 765–777. doi:10.1080/10503307.2020.1849848

- Whelton, W. J., & Greenberg, L. S. (2005). Emotion in self-criticism. Personnality and Individual Differences, 38(7), 1583–1595. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.09.024

- Winter, D., Bohus, M., & Lis, S. (2017). Understanding negative self-evaluations in borderline personality disorder—A review of self-related cognitions, emotions, and motives. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(3), 1–9. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0771-0

- World Health Organization. (2019). ICD-11. (No Title).

- Yen, S., Shea, M. T., Battle, C. L., Johnson, D. M., Zlotnick, C., Dolan-Sewell, R., … Sanislow, C. A. (2002). Traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: Findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190(8), 510–518. doi:10.1097/00005053-200208000-00003

- Zanarini, M. C., & Frankenburg, F. R. (1997). Pathways to the development of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 11(1), 93–104. doi:10.1521/pedi.1997.11.1.93