ABSTRACT

In Bad Beliefs, Levy presents a picture of belief-forming processes according to which, on most matters of significance, we defer to reliable sources by relying extensively on cultural and social cues. Levy conceptualizes the kind of evidence provided by socio-cultural environments as higher-order evidence. But his notion of higher-order evidence seems to differ from those available in the epistemological literature on higher-order evidence, and this calls for a reflection on how exactly social and cultural cues are/count as/provide higher-order evidence. In this paper, I draw on the three-tiered model of epistemic exchange that I have been developing recently, which highlights the centrality of relations of attention and trust in belief-forming processes, to explicate how social and cultural cues provide higher-order evidence. I also argue that Levy’s account fails to sufficiently address the issue of strategic actors who have incentives to pollute epistemic environments for their benefit, and more generally the power struggles, incentives, and competing interests that characterize human sociality. Levy’s attempted reduction of the political to the epistemic ultimately fails, but his account of social and cultural cues as higher-order evidence offers an insightful perspective on epistemic social structures.

1. Introduction

Neil Levy’s Bad Beliefs (Levy, Citation2021) presents a trailblazing philosophical analysis of the prima facie puzzling phenomenon of “bad beliefs”. These are understood as widespread beliefs that are at odds with expert consensus and/or widely available scientific evidence, such as climate change denialism and vaccine skepticism (two prototypical “bad beliefs”). Levy’s main contention is that, rather than the result of poor individual cognitive practices, such bad beliefs are by and large rational; they are formed and maintained by means of the same tried and tested mechanisms for social learning that guide us in most of our belief-forming processes. “[T]hose who come to hold bad beliefs do so for roughly the same sorts of reasons as those who come to hold good beliefs.” (Levy, Citation2021) (xi) (Henceforth, page numbers without specification refer to (Levy, Citation2021).) Bad beliefs arise primarily in environments that are epistemically polluted; bad believers are simply responding rationally to a subpar environment.

Levy maintains that, on most matters of significance, we defer to reliable sources rather than figuring things out on our own. “Given that we’re epistemically social animals, it’s largely through deference that we come to know about the world and generate further knowledge.” (xiii) Throughout the book, Levy offers a detailed description of these mechanisms of deference, where cultural and social cues play a significant role. A key feature of his argument is to cast these cultural and social cues as evidence: “we’re social and cultural animals, and we respond to the genuine evidence that our fellows and our cultural environment provide to us.” (xviii) More precisely, Levy conceptualizes the kind of evidence provided by socio-cultural environments as higher-order evidence. This allows him to maintain a form of epistemic purism/evidentialism: his overall strategy is to recast factors that are often viewed as non-epistemic (e.g., markers of group identity) as higher-order evidence, and thus as epistemic after all (see footnote 13 on p. 35).

While intriguing and in many respects quite compelling, Levy’s overall argument has some weaker spots, which have been noted by other commentators (Schliesser, Citation2022; Williams, CitationForthcoming; Worsnip, Citation2022). I am myself sympathetic to his depiction of belief-forming processes as being thoroughly social and largely outsourced to one’s socio-cultural environment. (I’m a Vygotskian after all (Dutilh Novaes, Citation2020a).) I also agree that there is some degree of rationality in, for example, the position of an anti-vaxxer who is convinced that the scientific establishment and governmental institutions do not have his best interests at heart, given the information at his disposal (Dutilh Novaes & Ivani, Citation2022; Dutilh Novaes, Citation2020b).

Nonetheless, I believe that the conceptualization of social and cultural cues as higher-order evidence needs to be further explicated, in particular in light of the vast literature on higher-order evidence produced over the last decades (see (Horowitz, Citation2022) for a recent overview). Levy’s notion of higher-order evidence seems to differ from those available in this literature, so it is worth reflecting on how exactly social and cultural cues are/count as/provide higher-order evidence. To do so, I draw on the three-tiered model of epistemic exchange that I have been developing recently, which highlights the centrality of relations of attention and trust in belief-forming processes (Dutilh Novaes, Citation2020b).

Ultimately, however, I argue that Levy’s account fails to sufficiently address the issue of strategic actors who have incentives to pollute the epistemic environment for their benefit. Indeed, power struggles, incentives, and competing interests –— what Chantal Mouffe (among others) conceptualizes as “the political” (Mouffe, Citation2005)—are largely absent from Levy’s book, despite arguably being one of the main root causes of “bad beliefs” (as also argued in (Schliesser, Citation2022)).

The paper is organized as follows. In part 2 I discuss Levy’s contention that social and cultural cues are (or provide) higher-order evidence. In part 3 I briefly present the three-tiered model of epistemic exchange, and investigate in which ways patterns of attention/salience and attributions of trustworthiness can be conceptualized as (pertaining to) higher-order evidence. In part 4 I briefly comment on what I perceive to be a dead angle in Levy’s overall project, namely his neglect of “the political”.

2. Levy on social and cultural cues as higher-order evidence

Levy emphasizes the role that social cues play in belief-forming processes, such as the views held by most members or well-regarded individuals in my community. In such cases, one should take the fact that they hold these views to be (higher-order) evidence for the views in question. In his words:

Our use of social referencing – our use of cues as to what others believe to form our own beliefs – the conformity bias and the prestige bias, our outsourcing of belief to the environment and our reliance on distributed networks of agents and artifacts; all of these should be seen as reliance on higher-order evidence. Evidence about what the majority believes is higher-order evidence …(147)

These cues can be viewed as providing higher-order evidence insofar as they pertain to “evidence that concerns … the reliability of the first-order evidence and how other people are responding to that evidence.” (xiii) “Higher-order evidence is evidence about our evidence.” (136) Levy maintains that higher-order evidence thus understood is not only significant; it is in fact typically more significant than first-order evidence for the majority of issues we encounter. “Within the narrow sphere of our expertise, our reliance on first-order evidence is relatively heavy; elsewhere, higher-order evidence plays a much greater role.” (150–1)

[C]ultural and social cues that … are essential to human flourishing and to knowledge production themselves work through the provision of higher-order evidence. We orient ourselves and make decisions centrally by reference to higher-order evidence.(xviii)

Those familiar with the epistemological literature on higher-order evidence will notice that this conceptualization of higher-order evidence as pertaining to social cues is somewhat nonstandard.Footnote1 In this literature, the notion of higher-order evidence is often presented as pertaining to the evidence that one has about the reliability of one’s own cognitive functions (Horowitz, Citation2022). For example, if I am largely reliable at a given task under normal circumstances, but then am informed that my current circumstances are adverse in ways that affect my performance on this task (I’ve been drugged; I’m suffering from lack of oxygen etc.), how confident should I be in the conclusions that I am drawing from the first-order evidence at my disposal? Indeed, the cases discussed are typically those where there is some kind of conflict between my first-order and my higher-order evidence (the latter seems to defeat the former somehow), and how to resolve the conflict. This is quite different from the phenomena that Levy is interested in, which are primarily situations where I either lack sufficient first-order evidence to reach a conclusion, or else am not skilled enough to interpret the available first order-evidence correctly. In both cases, I must defer to majority views in my community or to expert consensus (if there is one), which amounts to relying on higher-order evidence instead of the (unavailable or difficult to interpret) first-order evidence.

Is Levy entitled to this nonstandard approach to higher-order evidence? I think he is, for (at least) two reasons. Firstly, as noted in (Chen & Worsnip, CitationForthcoming), “the term ‘higher-order evidence’ is surprisingly hard to define precisely, and is, in practice, used in a confusing variety of different ways.” The literature relies on a number of paradigmatic cases to demarcate the class of relevant phenomena, but there does not seem to be sufficient consensus on what exactly these are. Now, if this is so, then arguably there is more room for alternative conceptualizations of the concept of higher-order evidence, i.e., more room for plasticity, than would be the case if the term had a more settled meaning. Secondly, Levy correctly points out that cases of peer disagreement (e.g., a calculation on how to split the restaurant check (Christensen, Citation2007)) are taken to be paradigmatic cases where higher-order evidence arises. But if disagreement counts as higher-order evidence, why wouldn’t agreement also count?Footnote2 “[A]greement also provides higher-order evidence. Given that a calculation is moderately difficult for me, if I come to the same answer as an independent agent, I should raise my confidence in it.” (138)

From these observations I conclude that Levy’s conception of higher-order evidence as primarily pertaining to confirmatory social cues,Footnote3 while nonstandard, is perfectly adequate. However, because it is nonstandard, much of the existing literature on higher-order evidence has little to offer when it comes to addressing the questions that Levy is interested in. Firstly, many of the paradigmatic cases in the literature pertain to intra-personal conflict (though not the peer disagreement cases), whereas Levy is primarily interested in social phenomena. Secondly, the issue of which rational norms should govern our belief-forming processes when first-order and higher-order evidence clash, which is central in this literature, is only tangentially relevant for Levy’s purposes. So additional conceptual resources are needed to explicate the provision of higher-order evidence by means of social cues. To this end, in the next section I draw on my work on the roles of attention and trust in social epistemic exchanges.

3. Higher-order evidence in networks of attention and trust

In this section I discuss some of the mechanisms through which social cues are/count as/provide higher-order evidence. I first briefly present the three-tiered model of epistemic exchange (TTEX), and then focus on two of its three tiers to understand how attention and trust relate to the provision of higher-order evidence by social cues. (The third tier is where engagement with first-order evidence primarily occurs, thus it is less relevant for present purposes.)

3.1 The three-tiered model of epistemic exchange

TTEX was inspired by a framework known as Social Exchange Theory (SET) (Dutilh Novaes, Citation2020b). SET was developed by sociologists and social psychologists in the mid-20th century to explain human social behavior in terms of processes of exchanges between parties, involving costs and rewards, and against the background of social networks and power structures (Cook, Citation2013). It was influenced by research in economics (rational choice theory) and psychology (behaviorism), as well as by anthropological work by Malinowski, Mauss, and Lévi-Strauss.

SET is an influential and empirically robust framework, which has been used to investigate a wide range of social phenomena such as romantic relationships, business interactions, trust in public institutions, among many others. In particular, it has been extensively used to investigate interpersonal communication (Roloff, Citation2015). The SET models are neither purely descriptive – as they rely on certain normative assumptions such as that agents seek to maximize rewards and minimize costs – nor purely normative, given that they incorporate experimental findings as well as extensive observational data. Moreover, SET combines a first-person perspective, which explains and predicts choices that individuals make between different potential exchange partners, with a third-person perspective, which focuses on structural features of these exchange networks.

TTEX adapts insights and results from SET to exchanges that are specifically epistemic, that is, when epistemic resources such as knowledge, evidence, information etc. are involved (possibly alongside non-epistemic resources). TTEX identifies three main levels in processes of epistemic exchange:

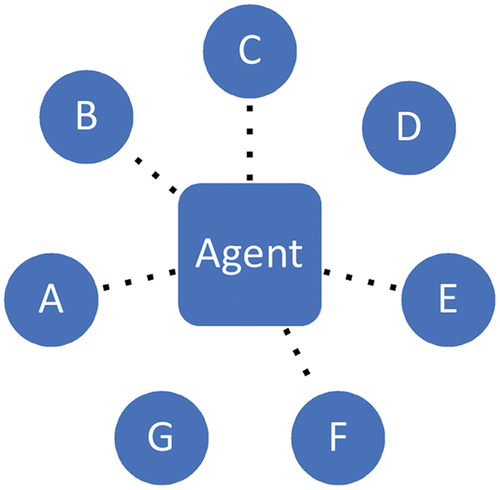

Attention/exposure. The first level consists in the networks determining who is a potential exchange partner to others, given the relevant opportunity structures for epistemic exchange (). Who is in a position to attract the attention of others? It may be that potential lines of communication are cut, for example in the case of censorship (Dutilh Novaes & de Ridder, Citation2021). But it may also be that so many signals are being broadcast that many different sources are competing for the receiver’s attention (Gershberg & Illing, Citation2022), in a so-called “attention economy” (Franck, 2019).

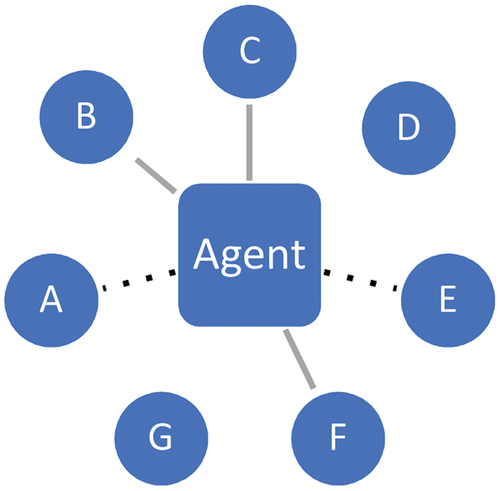

Choosing whom to engage with. The next level comprises the choices that agents make against the background of possibilities for exchange, as determined by the relevant opportunity structures (). Typically, there will be a number of options for a given agent – for example, the various newspapers that I can read on any given day, among those that I have access to. Given limitations of time and attention, contrastive choices will have to be made. Among those sources that have caught my initial attention, who do I deem to be worthy of consideration as an exchange partner? At this point, considerations of trustworthiness (Hawley, Citation2019) and expertise (Goldman, Citation2018) come into play, as well as the perceived value of the content being offered by different potential exchange partners.

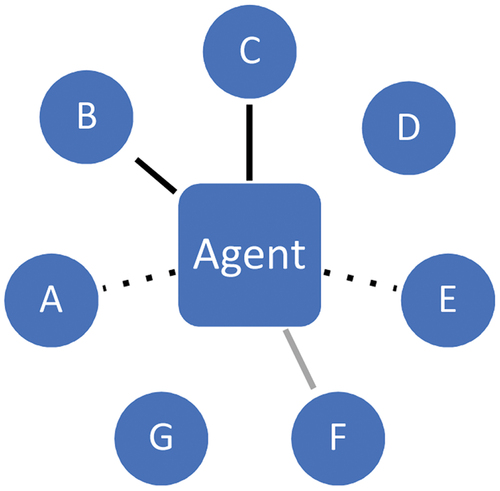

Engagement with content. It is only at a third stage that engagement with content properly speaking occurs; this is when the actual epistemic exchange in fact takes place (). At this point, the receiver will (reflectively) engage with the content in question, seeking to understand its substance and evaluate its cogency. In case of a positive evaluation, this may lead to a change in view for the receiver (though even at this stage the receiver may still balk at revising her beliefs).

The figures below represent the three tiers. (For simplicity, they depict a main agent and other agents around her, even though the model focuses on complex networks of agents.)

Attention: Agent does not “see” sources D and G, the other sources catch her attention (dotted lines in ).

Contrastive choices: Agent deems B, C and F as worth exchanging with (gray lines in ), but not A and E.

Engagement: Agent eventually engages substantively with B and C (black lines in ), but not with F.

Importantly, TTEX views agents as interconnected in complex networks, alternating the roles of sender and receiver of messages. The topologies of these networks crucially determine how messages propagate (Sullivan et al., Citation2020; Zollman, Citation2013). For example, agents squarely in the middle of these networks, with multiple potential connections, will typically be in a better position to exchange with many others and spread their messages across the network (O’connor & Weatherall, Citation2019). By contrast, agents at the fringes of networks will find it much harder to attract attention and engage in exchanges.

3.2 Attention and higher-order evidence

Can phenomena pertaining to tier 1—attention, exposure, salience – be conceptualized in terms of higher-order evidence? If so, how? The relevance of attention for (social) epistemology remains so far an undertheorized topic, having received more sustained attention only recently; relevant work includes (Gardiner, Citation2022; Munton, Citation2021; Pinedo & Villanueva, Citation2022; Smith & Archer, Citation2020).Footnote4 Smith and Archer (Citation2020) note that attention is characterized by being contrastive—it involves focusing or concentrating on some sources/objects instead of others – and by involving some degree of voluntary control while simultaneously being susceptible to external influences.

It is a trivial observation that an agent will only take (first-order) evidence into account in her belief-forming processes if she pays sufficient attention to it; unattended evidence is no evidence from the agent’s perspective. In this sense, attention is obviously epistemically relevant. But the epistemic relevance of attention goes beyond this elementary point. For example, an individual knower may come to hold false beliefs as a result of misplaced attention even if the information she has access to is accurate (Gardiner, Citation2022). More generally, a suboptimal distribution of attention in an epistemic environment can have pernicious epistemic effects. To investigate these phenomena, Munton (Citation2021) introduces the useful notion of a salience structure, understood as an ordering of information by accessibility in a given epistemic environment. She argues that certain important forms of prejudice can be explained as resulting from undue organization of information. A concrete example: the media may relentlessly report on crimes committed by immigrants even when, statistically, they are rare occurrences. By making these events disproportionally salient to the public, false beliefs about this group are induced (namely, that they are particularly prone to commit crimes).

These observations echo Levy’s general point that bad beliefs are largely a result of suboptimal (“polluted”) epistemic environments. Since attention is contrastive, if certain pieces of information are made more salient to me by means of e.g., repetition, my attention will be focused more on them than on other evidence that may well be available to me but is less salient. When cues are plentiful, they compete for attention. The salience structures in an epistemic environment will greatly influence the belief-forming processes of agents in this environment, and consequently the beliefs they come to hold.

Levy offers some brief comments on the relations between attention/salience and higher-order evidence. He notes for example that “[t]he use of environmental cues is the use of higher-order evidence: it renders options salient to us” (150) and that “we make certain facts salient to one another – sometimes through the design of the physical environment – to recommend them” (170). The suggestion seems to be that, when an agent sees to it that a piece of information is prominently displayed in her epistemic environment, in practice she is telling others that it is noteworthy information that they should pay attention to. From the receiver’s perspective, the inference will be that information that my (social and material) environment makes salient to me is probably relevant; it is likely the same information that my close peers are exposed to, with whom I need to coordinate in socio-epistemic processes. For the purposes of social coordination, joint attention is a valuable collective epistemic state (Tomasello, Citation2014), and environmental cues are instrumental in securing joint attention. Thus, the mere fact that many members of my community are attending to a certain piece of information is (defeasible) indication that it is something I need to pay attention to, if nothing else for group-cohesion reasons.

But notice that Levy makes a stronger claim: the mere act of making a content salient counts as a recommendation. Levy conceptualizes recommendations as nudges, as implicit cues that the option made salient is choiceworthy (139–141). The framing in terms of nudges suggests practical choices that will be good or bad, rather than beliefs that will be true or false. But equally relevant is the question of whether mere salience lends support to the truthfulness of a piece of information, especially as Levy is interested in (bad) beliefs.Footnote5 There is empirical evidence that people have a tendency to conflate salience with truthfulness (e.g., the illusory truth effect (Fazio et al., Citation2015)). But do we want to go as far as saying that it is perfectly rational for agents to take mere repetition and salience as a sign of truthfulness? True enough, if many independent sources all send the same signal, this may be rationally interpreted by the receiver as cumulative (higher-order) evidence for the truthfulness of the signal (a point familiar from the literature on testimony). But of course, in environments of dense connectivity, the independence clause often fails (e.g., information cascades (Jalili & Perc, Citation2017)), which means that mere salience may be misleading even when the environment is not strategically manipulated.

We can thus agree that people typically do take salience to be an indicator not only of relevance but also of truthfulness. But the normative claim that it is rational for them to do so does not follow,Footnote6 both in view of cascade phenomena and in view of the ease with which an environment’s salience structure can be manipulated. Examples of such manipulation include traditional propaganda that suppresses messages contradicting the dominant ideology (Stanley, Citation2015; Welch, Citation1993), and “flooding the zone” strategies of bombarding the environments with noise so as to cause confusion (Pomerantsev, Citation2019; Starr, Citation2020).

Be that as it may, recognizing the role of attention and salience in belief-forming processes entails that salience structures displaying problematic arrangements may negatively affect these processes, which in turn supports Levy’s call for the epistemic engineering of environments. As an example of engineering interventions, Levy cites no-platformingFootnote7: “a policy of ensuring that higher-order evidence is conveyed appropriately may support no-platforming certain speakers, on the grounds that provision of a platform itself provides higher-order evidence in favor of a view.” (147) But insofar as attention also involves some degree of voluntary control, then “bad beliefs” may be mitigated not only by epistemic engineering of the environment but also by agents carefully curating their attentional regime (Gardiner, Citation2022). So “bad believers” may well be at least partially responsible for how they (mis)manage their attention.

3.3 Trust and higher-order evidence

As noted above, Levy emphasizes the crucial role of deference in how we come to know about the world and generate further knowledge. But how do we choose whom to defer to? These choice mechanisms are precisely what tier 2 of TTEX theorizes. At this level, an agent assesses the suitability of her different potential exchange partners as sources of epistemic resources. Epistemologists have discussed tier-2 phenomena extensively over the last decades, in particular testimony (Lackey & Sosa, Citation2006), trust (Dormandy, Citation2021), and expertise (Goldman, Citation2018), and these phenomena are quite naturally conceptualized in terms of higher-order evidence. Prima facie, markers of a source’s trustworthiness/expertise operate as higher-order evidence for the content transmitted: S says that p, and S is (perceived as) trustworthy/an expert on topics pertaining to p, so S’s endorsement counts as higher-order evidence for the truthfulness of p.Footnote8

There is much debate on what trust and trustworthiness consist of, but three conditions for trust seem largely uncontroversial in the literature:

Trusting requires that we can, (1) be vulnerable to others – vulnerable to betrayal in particular; (2) rely on others to be competent to do what we wish to trust them to do; and (3) rely on them to be willing to do it. (McLeod, Citation2020)(section 1)

When it comes to epistemic trust, these conditions entail (1) vulnerability to being misled/misinformed; (2) reliance on an informant’s sufficient knowledge in the domain in question, which is primarily an epistemic condition; (3) reliance that an informant will not purposefully misinform, which is primarily a moral/ethical/political condition. Thus, when evaluating the trustworthiness of an informant, there are two main factors to be taken into account: their competence (knowlegeability), and their benevolence.Footnote9 An informant is (sufficiently) benevolent toward me if she will not seek to deliberately promote her interests over mine.Footnote10 This may happen if there is no real conflict between her interests and mine, in which case she may act in self-interest and yet will not be harming my own interests (our interests may be aligned). Alternatively, she may harbor genuine goodwill toward me, in which case she may act in ways that promote my interests even if this may harm hers. Finally, she may be motivated by overall moral rectitude, which prevents her from systematically promoting her interests over other people’s.

For an informant to be considered trustworthy, both conditions need to obtain: competence and benevolence. An informant may mean well but simply be incompetent (not sufficiently knowledgeable) on a given topic, in which case the information offered will likely not be accurate. Alternatively, they may be competent, but their ultimate goal may be to promote their own interests over mine, in which case they may try to manipulate my doxastic states to their advantage. If the agent perceives an informant as either incompetent or as not benevolent toward her (or both), then she will perceive the informant as untrustworthy.

The problem, as Levy himself persuasively argues in Chapter 5, is that, as lay people, we’re typically not in a good position to identify competence (on a given topic): “cues for expertise don’t correlate well with its actual possession” (112). We are too ignorant to evaluate the first-order evidence on the matter under dispute ourselves (by hypothesis), and we are not good either at what Anderson (Anderson, Citation2011) describes as the second-order assessment of the trustworthiness of experts. Moreover, since trusting experts involves not only their competence but also their benevolence toward us (understood as sufficient alignment of interests, which incidentally is something that Levy does not sufficiently address in the book), we need somehow to be able to assess both factors independently, which proves to be a formidable, nearly unfeasible challenge (Duijf, Citation2021). Thus, while Levy recommends deference to experts (which he views as an appropriate use of higher-order evidence), he himself recognizes that ascertaining which experts to defer to in case of expert disagreement is tricky, precisely because we’re often not in a good position to assess the relevant higher-order evidence (cues for expertise).

Besides deference to experts, Levy cites approvingly the conformity bias and the prestige bias, and argues that they are in fact reliable epistemic strategies. The conformity bias consists in asking myself what do people like me believe and orienting my beliefs to align with theirs. The prestige bias in turn centers the beliefs of prestigious people in my community. But why is it rational to treat being like me as a mark of being a (more) reliable source of information? As Worship asks (Worsnip, Citation2022), “is my trusting itself open to rational assessment?”

Levy contends that the conformity bias “is rational because those who don’t share my values may seek to exploit me, and those on my side are likely to be more trustworthy (toward me).” (82) He thus relies on the presumed benevolence of “people like me” to justify the rationality of trusting them on epistemic matters. But there are at least two issues with this claim. Firstly, it does not address the competence clause for trustworthiness; what if all those like me, myself included, are simply incompetent in the relevant domain, and thus unreliable informants? Secondly, being “like me” is also an imperfect marker of benevolence, and one that is in fact often used for spurious political purposes. As Worsnip notes (Worsnip, Citation2022), “exploitation can come from those who are (perceived to be) on one’s political ‘side’ just as much as those on the other side.” (Alas, real-life examples abound.)

In sum, while I very much agree with Levy that, generally speaking, other agents’ beliefs and behavior provide higher-order evidence, I am less optimistic that we are in a good position to correctly assess whom to trust, that is, which agents’ beliefs and behavior should influence ours. While it is rational to defer to trustworthy sources – who must be both sufficiently competent on the relevant subject and sufficiently benevolent toward me – it is very difficult to recognize trustworthiness accurately. Markers of competence and benevolence are quite unreliable, and highly susceptible to strategic manipulation—which brings us directly to the final issue that I want to address.

4. But where is the political?

Levy’s starting point in the book are politically charged controversies on topics such as climate change and vaccines. His overall strategy is to frame these controversies in epistemic terms – as ‘bad beliefs’–which accordingly can be addressed with the tools from social epistemology and cognitive science. He does recognize the existence of “those who … manipulate us by targeting our beliefs,” (4), but seems to think that we’re at least to some extent protected from bad-faith epistemic manipulation. In a footnote, he remarks:

Again, this outsourcing leaves us open to exploitation by those who can make use of it, of course. The degree to which we’re vulnerable to exploitation is limited by the fact that we remain sensitive to first-order evidence regarding how well we’re doing: voters turn on the governing party when economies falter, for instance. We integrate our higher-order evidence with the first-order evidence that is sufficiently near and clear for us to make use of it.(79)

This seems overly optimistic, and somewhat in tension with the overall message of the book that first-order evidence plays a small role in our belief-forming processes on most domains. More importantly, it suggests a purely epistemic counterbalance to phenomena that are arguably primarily political. Indeed, power struggles and competing interests – what Chantal Mouffe conceptualizes as “the political” (Mouffe, Citation2005)–are largely absent from the book. More generally, Levy seems to paint an overly rosy picture of human sociality, one where politics, conflicts, incentives and self-serving interests remain undertheorized. As noted in (Williams, CitationForthcoming), “we are also highly competitive, hypocritical, self-deceiving, status-seeking, coalitional primates.”

Levy seems to suggest that political phenomena are mostly reducible to epistemic phenomena. But as noted by Schliesser (Citation2022, p. 5), “our epistemic environment is in many ways a social and politicized environment. Within this environment, there will be many strategic actors who may have incentives and interests to pollute it […]. This is the human condition.” Schliesser further notes that, if epistemic pollution is indeed primarily the effect of motivated interests, then it will continue to exist as long as power is concentrated in the hands of those (or other) unscrupulous actors. The “polluters” not only spread first-order disinformation but also (or even primarily) higher-order disinformation, influencing perceptions of competence and benevolence of sources in their favor (Nguyen, Citation2020).

From this point of view, it seems a bit naïve to expect that these issues can be tackled purely or even mostly with epistemic strategies such as epistemic engineering or nudging, as long as power imbalances allow for systemic epistemic manipulation. Surely there is an important epistemic dimension in oppressive social arrangements (as (Mills, Citation2017) cogently argues), and political change will involve at least to some extent changing minds (a familiar Gramscian point). However, strategic polluters will typically resist efforts of “epistemic cleanses”, resulting in very classical power struggles.

A case in point are measures to regulate the spread of disinformation in digital environments. Predictably, there is much push-back from proponents of “free speech”, who (in good faith or not) contend that this kind of governmental interference creates a dangerous precedent. A recent example are the efforts by the Brazilian Supreme Court in the period leading to the October 2022 presidential elections to counter systematic disinformation campaigns orchestrated by the incumbent candidate Bolsonaro and his supporters, who challenged the reliability of the country’s (extremely robust) electronic voting system.Footnote11 What ensued was a bitter political battle: attacks on the very foundations of democratic institutions countered by juridical measures, thanks to a still sufficiently functional political system with enough power balance between the three branches of government.

Despite these reservations, there is no denying that Bad Beliefs is an important and thought-provoking book that is likely to stir fruitful discussion for years to come. Especially the conceptualization of social and cultural cues as higher-order evidence offers an extremely fertile perspective for those interested in epistemic social structures in all their complexities.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Eric Schliesser, Colin Rittberg, and Alex Worsnip for comments on earlier drafts. This research was generously supported by the European Research Council with grant ERC-2017-CoG 771074 for the project ‘The Social Epistemology of Argumentation’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Insofar as Levy adopts a general conception of higher-order evidence as “evidence about our evidence”, then his conceptualization is not particularly nonstandard (Chen & Worsnip, CitationForthcoming). But the focus specifically on social and cultural cues as providing higher-order evidence is largely absent in this literature so far.

2. Horowitz (Citation2022) also recognizes the parity: “the focus [in the literature] is on higher-order defeat, rather than higher-order confirmation, even though these possibilities go hand in hand.” Notice though that it matters whether the agreement in question comes from people like me (as in the peer disagreement cases) or from people not like me. (I owe this point to Alex Worsnip.) See section 3.3 below for further discussion.

3. However, since confirmation tends to be contrastive – evidence e confirms view A and thus disconfirms other views incompatible with A – Levy’s social cues may also give rise to situations of conflict between first-order and higher-order evidence.

4. See also network epistemology (Zollman, Citation2013), even if this research program does not problematize the concept of attention explicitly.

5. On a purely ecological conception of rationality, the issue of truthfulness may not even arise. But Levy makes it clear that he is (also) committed to a veritistic conception of rationality: “We respond to the higher-order evidence encoded in our environment and in the assertions of others, by deferring to them or even self-attributing beliefs. We do so in the service of truth.” (153).

6. Levy does not state this claim explicitly, but this is what seems to be required to make sense of the idea that salience has (higher-order) evidential import for beliefs, not only for practical choices.

7. See also (Pinedo & Villanueva, Citation2022).

8. But see (Chen & Worsnip, CitationForthcoming), who view testimony that p as first-order evidence for p. Perhaps what counts as higher-order evidence are S’s markers of competence and reliability, not their testimony that p itself.

9. Benevolence and competence (and perceptions thereof) are arguably a matter of degrees, and accordingly so is trustworthiness. Often, what matters is trustworthiness above a certain threshold, which may vary according to the situation.

10. Interests are states of affairs that individuals or groups wish to bring about; typically (though not necessarily), they will tend to contribute to the wellbeing of the individual or group in question (Dutilh Novaes, Citation2021).

References

- Anderson, E. (2011). Democracy, public policy, and lay assessments of scientific testimony. Episteme, 8(2), 144–164. https://doi.org/10.3366/epi.2011.0013

- Chen, Y., & Worsnip, A. (Forthcoming). Disagreement and higher-order evidence. In M.Baghramian, J. A. Carter, & R. Rowland (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of the philosophy of disagreement. Routledge.

- Christensen, D. (2007). Epistemology of disagreement: The good news. The Philosophical Review, 116(2), 187–217. https://doi.org/10.1215/00318108-2006-035

- Cook, K. S. (2013). Social exchange theory. In J. DeLamater & A. Ward (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 6–88). Springer.

- Dormandy, K. (Ed.). (2021). Trust in epistemology. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Duijf, H. (2021). Should one trust experts? Synthese, 199(3–4), 9289–9312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03203-7

- Dutilh Novaes, C. (2020a). The dialogical roots of deduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Dutilh Novaes, C. (2020b). The role of trust in argumentation. Informal Logic, 40(2), 205–236. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v40i2.6328

- Dutilh Novaes, C. (2021). Who’s afraid of adversariality? conflict and cooperation in argumentation. Topoi, 40(5), 873–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-020-09736-9

- Dutilh Novaes, C., & de Ridder, J. (2021). Is fake news old news? In S. Bernecker, A. K. Flowerree, & T. Grundmann, The epistemology of fake news (pp. 156–179). Oxford University Press.

- Dutilh Novaes, C., & Ivani, S. (2022, September 6). The inflated promise of science education. Boston Review. https://bostonreview.net/articles/the-inflated-promise-of-science-education/

- Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N. M., Payne, B. K., & Marsh, E. J. (2015). Knowledge does not protect against illusory truth. Journal of Experimental Psychology General, 144(5), 993–1002. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000098

- Gardiner, G. (2022). Attunement. In M. Alfano, C. Klein, & J. de Ridder, Social Virtue Epistemology (1st ed., pp. 48–72). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367808952-7.

- Gershberg, Z., & Illing, S. D. (2022). The paradox of democracy: Free speech, open media, and perilous persuasion. University of Chicago Press.

- Goldman, A. I. (2018). Expertise. Topoi, 37(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-016-9410-3

- Hawley, K. (2019). How to be trustworthy. Oxford University Press.

- Horowitz, S. (2022). Higher-order evidence. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/higher-order-evidence/

- Jalili, M., & Perc, M. (2017). Information cascades in complex networks. Journal of Complex Networks. https://doi.org/10.1093/comnet/cnx019

- Lackey, J., & Sosa, E. (Eds.). (2006). The epistemology of testimony. Oxford University Press.

- Levy, N. (2021). Bad beliefs: Why they happen to good people. Oxford University Press.

- McLeod, C. (2020). Trust. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/trust/

- Mills, C. W. (2017). Black rights/white wrongs: The critique of racial liberalism. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190245412.001.0001

- Mouffe, C. (2005). On the political. Routledge.

- Munton, J. (2021). Prejudice as the misattribution of salience. Analytic Philosophy, Phib, 64(1), 12250. https://doi.org/10.1111/phib.12250

- Nguyen, C. T. (2020). Echo chambers and epistemic bubbles. Episteme, 17(2), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2018.32

- O’connor, C., & Weatherall, J. O. (2019). The misinformation age. Yale University Press.

- Pinedo, M. D., & Villanueva, N. (2022). Epistemic de-platforming. In D. B. Plou, V. F. Castro, & J. R. Torices (Eds.), The political turn in analytic philosophy (pp. 105–134). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110612318-007

- Pomerantsev, P. (2019). This is not propaganda. Faber & Faber.

- Roloff, M. (2015). Social exchange theories. In Charles R. Berger, & Michael E. Roloff (Eds.), International encyclopedia of interpersonal communication (pp. 1–19). Wiley.

- Schliesser, E. (2022). Review of Bad Beliefs: Why they happen to good people. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02698595.2022.2119492

- Smith, L., & Archer, A. (2020). Epistemic injustice and the attention economy. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 23(5), 777–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-020-10123-x

- Stanley, J. (2015). How propaganda works. Princeton University Press.

- Starr, P. (2020). The flooded zone: How we became more vulnerable to disinformation in the digital era. In W. L. Bennett & S. Livingston (Eds.), The disinformation age (1st ed., pp. 67–92). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108914628.003

- Sullivan, E., Sondag, M., Rutter, I., Meulemans, W., Cunningham, S., Speckmann, B., & Alfano, M. (2020). Vulnerability in social epistemic networks. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 28(5), 731–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/09672559.2020.1782562

- Tomasello, M. (2014). A natural history of human thinking. Harvard University Press.

- Welch, D. (1993). The third reich: Politics and propaganda. Routledge.

- Williams, D. (Forthcoming). Bad Beliefs: Why they happen to highly intelligent, vigilant, devious, self-deceiving, coalitional apes. Philosophical Psychology.

- Worsnip, A. (2022, November 2). Review of “Bad Beliefs: Why they happen to good people.” Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. https://ndpr.nd.edu/reviews/bad-beliefs-why-they-happen-to-good-people/

- Zollman, K. (2013). Network epistemology: Communication in epistemic communities. Philosophy Compass, 8(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-9991.2012.00534.x