ABSTRACT

Six people were interviewed about the possibility of becoming posthumous body donors. Interview transcripts were analyzed using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Individual-level analysis suggested a common interest in Personhood Concerns and a common commitment to Enlightenment Values. Investigations of these possible themes across participants resulted in identification of two sample-level themes, each with two subthemes: Autonomy, with subthemes of agency and consent, and Rationality, with subthemes of knowledge/epistemology and materialism/ontology. This paper concentrates on the former. Consent for posthumous body donation was felt to sometimes fall short of adequately identifying donors’ preferences about what happened after consent was given, even with respect to actions for which consent established permission. In turn, paucity of information about donors’ preferences limited others’ ability to act as proxy agents to facilitate donors’ posthumous autonomy. Thus, while consent may curtail violations of people’s autonomy by authorizing actions for which permission has been established, it may fall short of facilitating their autonomy in ways that might be possible with greater knowledge of those people’s desires. Alternative methods of establishing consent are explored that might better-determine people’s desires and thereby improve others’ ability to act as proxy agents for them to facilitate their subsequent (even posthumous) autonomy.

Because our actions can affect other people’s welfare and autonomy, it is sometimes morally appropriate to try to establish whether others assent or dissent to us performing certain actions (or if they would be likely do so, if asked), thereby giving ourselves the opportunity to take their apparent preferences into consideration when deciding whether and how to act (Sibley et al., Citation2012). In some circumstances, moral, legal, or other prescriptions demand more than this, i.e., that we must establish (or appropriately infer) permission from others to act in ways that we anticipate will or may affect them (Dunn, Citation2016). Establishing such permission from people authorized to give it – i.e., establishing consent – has the potential to make actions that might otherwise be morally questionable at least morally acceptable (Boulton & Parker, Citation2007).

Consent for an action is considered valid if people entitled and competent to do so voluntarily give their permission for that action to occur, or it is established that they would do so if asked. The perceived validity of consent therefore varies according to claims concerning who is entitled to give permission; how voluntarily they give their permission; how competent they are to give permission; and how appropriately informed they are about what they are giving permission for (Boulton & Parker, Citation2007). How well-established consent for an action is depends on how clearly that consent grants permission for that action at the time it occurs (Gruber, Citation2016; Prabhu, Citation2019). People can sincerely disagree about how entitled, competent, knowledgeable, and free a person must be to give valid consent, as well as about how well-established consent must be to suitably grant permission for particular actions (Boulton & Parker, Citation2007; Boyd, Citation2015; Grady & Longo, Citation2015; Helgesson & Eriksson, Citation2011; Horn, Citation2014; Sommers, Citation2019; Zealley et al., Citation2022).

People can also disagree about the necessity and sufficiency of consent as a criterion for ensuring ethically appropriate conduct. For example, Onora O’Neill says that although consent “is commonly viewed as … key to respecting … autonomy, this claim is … deeply obscure” (O’neill, Citation2003, p. 5). To the extent that consent is valid and well-documented, it mainly serves as protection of people’s autonomy by limiting things that violate it. This seems a crucial but rather weak form of respecting autonomy. We submit that stronger forms would not merely establish people’s permission but would also or instead seek to facilitate what people want, wanted, or would want (Emba, Citation2022; Uniacke, Citation2013), i.e., their agency (Maclean, Citation2006). Further, if consent is conditional in any way, it may be withdrawn or become invalid or irrelevant if consenters or circumstances significantly change (Chan et al., Citation2017). There are also issues of how consent interacts with other ethically relevant principles, such as rights to legitimately veto something that someone else has given consent for (Mason & Laurie, Citation2001). In short, understanding consent, autonomy, and the relationship between the two is a challenging task.

The study reported below was part of a program of research investigating potential motives and concerns of people involved in body donation. Body donation is an important practical matter because much medical teaching and research relies heavily on a regular supply of donated dead bodies and parts thereof (Habicht et al., Citation2018). It is also important morally and legally, not least because of the various ways that bodies may be obtained (Champney et al., Citation2018) and the multiple things than can be done with and to them (Cornwall, Citation2016). Mindful of the complex combinations of motives and concerns that potential and actual body donors can have (Farsides et al., Citation2021), the current authors were keen to investigate the specific motives and concerns of local stakeholders in body donation.

In line with recent calls suggesting a need for and multiple benefits of such research (Andow, Citation2016), our study was qualitative and exploratory rather than being set up to test hypotheses derived from existing psychological theories or philosophical positions (Thompson, Citation2023). The latter point is particularly important. Our study was not guided by or intended to be informative about philosophical issues per se, either in general or in relation to specific topics such as agency, autonomy, or consent. We sought to investigate our participants’ views about the possibility of becoming body donors in the expectation that this might help us identify and further investigate concerns that could be common among potential body donors in our geographical area at this time. Nevertheless, our results suggested that some of our participants’ most important concerns related to issues of agency, autonomy, and consent, concerns that we feel are potentially relevant far beyond the specific domain of posthumous body donation.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research Governance and Ethics Committee of Brighton and Sussex Medical School. Participants gave written, informed consent, including for the use of anonymized quotes in publications resulting from the research.

Context

Body donation in England is regulated by the Human Tissue Authority (HTA). The HTA describes its regulatory approach as being based on four guiding principles, of which consent is presented as “the fundamental principle” (HTA, Citation2020a). The HTA explains that this means that donors’ “wishes are paramount” and it assures each prospective donor that “your body … will only be used in accordance with your wishes” (HTA, Citation2020b, p. 1). Similar guarantees are increasingly provided in body donor recruitment programs across the globe (Champney et al., Citation2018).

shows part of the HTA’s “body donation card” (HTA, Citation2022). This gives people an opportunity to register a wish for their bodies to be donated after their death. An accompanying webpage (HTA, Citation2021) says that donated bodies “can be used for a number of purposes, which may include: Anatomical examination … Research … Education and training.”

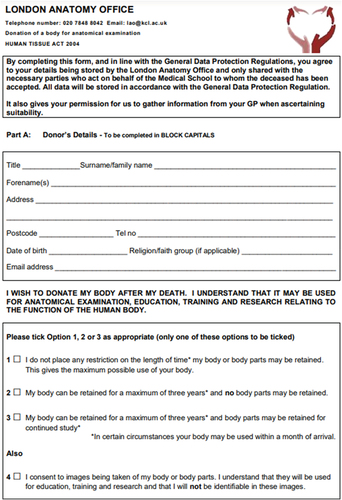

The second author receives donated bodies administered by the London Anatomy Office (LAO). shows part of the LAO’s “Consent Form” (retrieved from https://www.kcl.ac.uk/research/london-anatomy-office). This form suggests that someone signing it is: (1) declaring that they “wish” to donate their body after their death; (2) declaring that they “understand that it [i.e., the donated body] may be used for anatomical examination, education, training, and research relating to the function of the human body”; and (3) giving or withholding permission for various specific possibilities, e.g., donated bodies or body parts “being used for Public Display”.

Sample

Known stakeholders in body donation were, for that reason, invited to participate as interviewees. All six people interviewed were British, professional women, and all but one was white, but none of these characteristics were sampling criteria. Four participants were known to the second author in her professional capacity and two were identified as promising participants by earlier interviewees. shows interviewees’ pseudonyms and the key characteristics that lead them to be invited to be participants. One further intended interviewee (an undertaker) agreed to participate but circumstances prevented this. No one approached refused to participate. Data collection stopped when the authors felt both that they had sufficient data for their purposes and that further interviewing seemed likely to yield negligible analytic advantage. The sample size and composition are in line with recommendations for studies of this type (Smith et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Data collection

Each interview was conducted by the first author between October 2018 and June 2019. Three were face-to-face (Marigold, Brigitte, Sally) and three were video-conferenced. Four interviews were one-to-one, but Mel and Emma were interviewed together.

A semi-structured interview guide was used. The first question was intended to elicit the fullest and least constrained account possible of participants’ views about personally becoming body donors (Oxburgh et al., Citation2010): “Please can we start by you telling me your views about the possibility of you becoming a body donor? Please try to tell me everything you can that might help me understand your views on this”. Most follow-up questions were intended to ensure that all participants gave full accounts of various aspects of their views, e.g., the main advantages and disadvantages they saw in becoming body donors; decisive reasons for acting as they did; influences on their decisions and actions; changes in their attitudes across time, etc. (Oxburgh et al., Citation2010). shows all the questions included in the interview guide. The interviewer asked additional questions whenever doing so seemed likely to be helpful to facilitate the interviewing process or to obtain analytically useful information.

Table 2. Interview schedule.

Data transcription

As soon as possible after each recorded interview was completed, recordings were transcribed by professional transcribers from audio recordings. Transcripts were verbatim and included mention of salient paralinguistic features, e.g., laughs, extended pauses. The interviewer then listened to the audio recording and checked and made minor corrections and annotations to each transcript.

The attempted recording of the video-interview with Anna failed. Upon realizing this, immediately after the interview, the interviewer made extensive “field notes” of what he remembered being said. Although these informed and facilitated interrogation of the on-going analysis and results, no quotes from Anna are used to illustrate points below.

The interviewer then produced more-anonymized versions of each transcript. All actual and many potential identifiers were replaced with pseudonyms or descriptions, e.g., “I’m a professional harpsichordist and recently retired as president of the Magic Circle” might have been changed to “[Gives musical occupation and notes recent presidency of a prestigious international society]”. Maximum anonymity was sought with minimum loss of information that might be analytically important. The final anonymized transcripts may be seen at https://osf.io/wrnkz/

Data analysis

The first author used interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA: Nizza et al., Citation2021; Smith et al., Citation2021). Analysis started as soon as the first interview was completed and continued until just before the submitted draft of this paper was completed.

In line with a distinctive feature of IPA, each transcript was analyzed separately (i.e., “ideographically”) and only then were all transcripts analyzed at a sample-level (i.e., “nomothetically”). Both types of analysis sought to capture themes and relationships among themes within the relevant dataset. For present purposes, a theme summarizes what various data have in common that makes them seem indicative of a distinctive and explanatorily important construct that is illustrated by those data. Within the general topic of interest (i.e., participants’ views about personal body donation), specific themes were initially identified “inductively” as they became apparent to the analyst (i.e., there were no pre-identified themes) and then abandoned or amended if different themes seemed to better represent data of particular interest. To learn more about how analyses proceeded, including something about the first author’s “reflexivity”, we have included some of our analytic “memos” in footnotes of the anonymized transcripts posted at https://osf.io/wrnkz/.

Respondent validation

At different stages in the research process, each interviewee was offered both full and anonymized versions of transcripts of their own interview, a summary of the analysis of their own interview, and a copy of an earlier draft of this paper. Interviewees who accepted any of these invitations were invited to make comments and request changes (Barbour, Citation2001). Requests for further anonymization were always granted. Comments on analyses and the draft paper were generally positive and did not lead to substantial analytic changes.

Second-author audit

Just before conducting the respondent validation, the first author provided the second author with an earlier draft of this paper, anonymized transcripts, and various documents recording earlier stages in the analysis and reasons for key analytic decisions taken. In discussion with the first author, the second author adopted a “demanding critical friend” perspective to evaluate all claims and explore avenues for possible improvement. This paper is in part a product of that process.

Results

Personal experiential themes

shows the two most prominent themes identified for each participant, known within IPA as Personal Experiential Themes. These suggested common commitment among participants to what might be called Enlightenment Values (Bristow, Citation2017, e.g., curiosity, discovery, discussion, enquiry, freedom, humanism, knowledge, materialism, progress, rationality) and Personhood Concerns (Fjellstrom, Citation2005, e.g., mind-body relations, personal autonomy, personal identity, personal meaning, personal purpose, self-development). Enlightenment Values and Personhood Concerns were thereby identified as possible cross-participant themes of importance, known within IPA as Group Experiential Themes (GETs).

Table 3. The two most prominent personal experiential themes for each participant.

Group experiential themes

Each transcript was reexamined to identify text that seemed related to any aspect of Enlightenment Values or Personhood Concerns. That text was recoded to try to best identify the nature of these themes or of others that seemed to better characterize the text under consideration. This led to GETs which we called Rationality and Autonomy, with subthemes of knowledge/epistemology and materialism/ontology for the former and agency and consent for the latter. Transcripts were then further reexamined to mark-up and where necessary recode text particularly relevant to these GETs.

This paper reports results relating only to the Autonomy GET. This relatively narrow focus allows us to include multiple extended quotes from participants which in turn, and in line with the aims of IPA, fosters comprehensive and nuanced appreciation of both within-participant and between-participant phenomena, as well as facilitating readers’ ability to critically evaluate our analyses (Tamminen et al., Citation2021).

A note about quotes

Participant quotes below are sometimes abridged to focus only on material most relevant for the analysis under discussion and to improve readability. Punctuation has also been changed to further optimize readability. Numbers in brackets after quotes refer to line numbers within transcripts posted at https://osf.io/wrnkz/ so that quotes can be examined unabridged and in context.

Autonomy, agency, and consent

Discussion in the results below focuses on key features of, and relationships among, the constructs Autonomy, Agency, and Consent within our analysis. Readers may inspect all data identified as relating specifically to each of these constructs by exploring the annotated transcripts posted at https://osf.io/wrnkz/ using the search-terms #Autonomy: Agency, and #Autonomy: Consent.

Desires and willingness to do what?

The phrase “become a body donor” proved ambiguous, with discussants frequently slipping between meaning on the one hand people registering (at least) willingness for their body to be examined posthumously and on the other their bodies being accepted for posthumous examination. In analysis, it was also often necessary or helpful to further differentiate between attitudes to each of these things and potentially distinct attitudes toward various personnel (e.g., surgeons) doing various things (e.g., dissection) for various purposes (e.g., skill development) and with various possible outcomes (e.g., improved health-care provision). These distinctions, and common failures to make or recognize them, made it particularly important and instructive to try to be clear about what, precisely, participants sought, wanted, and were willing to permit.

Marigold thought that she might register body donation willingness in the future as a way of granting permission for her body to be examined posthumously:

[Tom: If somebody told you that you couldn’t be a body donor, how would you feel about that?] I would be fine. [Tom: Okay, so you’d like to be helpful but you’re not that bothered, if, for whatever reason, you can’t be?] No. (797-808)

Brigitte felt that she had availed of an opportunity by registering her body donation willingness. She liked the possibility that (in certain circumstances – see below) her body would be accepted for posthumous examination and subsequently prove to be useful, but what she specifically wanted to do was to make that a possibility:

It’s part of your whole contribution to the world, like a ripple where you throw something into a pond and other things can happen as a result. Maybe your body is used by someone who goes onto become a world-famous scientist; you have no idea, and it doesn’t really matter. (70-76) I don’t care what the outcome is. That doesn’t matter to me. (121-122) I want to be able to say, “I did what I could.” (138) I’ve made a decision to give and making the decision to give is the important thing. (729-730)

Mel wanted more. Although she had already registered body donation willingness (and desire), that act seemed not to be intrinsically satisfying for her. Rather, Mel saw registration as potentially instrumental to facilitate consequences that she wished to see come about (the fulfillment of which would nevertheless require others’ support), i.e., actual contributions to medical education or science:

I can do some good when I’m dead; teaching health care professionals anatomy. (113-115) [Tom: How would you feel if you knew in advance that you weren’t going to become a donor?] (331-333) I’d be really disappointed. [I’d feel] a great regret, because it’s such a waste to burn our bodies when they’re so vital for students for their learning. It’s all about the education. (365-371)

Honoring donors’ wishes

All participants believed that registering body donation willingness is and should be a matter of individual choice: “It’s a very personal decision” (Sally, 583). All also agreed that “it’s nice when people die and you know what they wanted” (Marigold, 520–521). All also wanted and planned to fulfil the body donation wishes of their loved ones, with some already having done so. Brigitte expressed satisfaction that she had been able to help implement her father’s desired donation and believed that people feel driven to honor their relatives’ preferences, even at some personal cost:

I could do the last thing that he wanted me to do for him, which made me feel very good. (231-236) On the other side, there’s people where the person who’s died wanted the body donation and the person who’s left didn’t, but they’re still having to do it to fulfil the other person’s wishes. (249-251)

The two participants who routinely work with relatives of deceased donors corroborated Briggite’s view:

We get tears often when we can accept [i.e., a donated body]. They [i.e., facilitating relatives] just break down, saying, “Oh, thank you so much. It’s so lovely … Mum’s always wanted to do that.” (769-774)

We couldn’t accept [the body of] her next of kin. She was very happy about that. She did what her next of kin had wanted. She’d tried to donate but got the result that she wanted, ultimately, and couldn’t. (194-197) It’s the thing we hear all the time, “It’s what they wanted”. So, they put their feelings to one side. (209-210)

Thus, there was a general view that most people want, intend, and try to implement loved ones’ body donation wishes: “If it’s what they wanted, I’m going to try and make it happen for them” (Emma, 679–711). This suggests that when people agree for loved ones’ bodies to be passed into the stewardship of anatomists, they are doing so primarily to facilitate the “posthumous agency” of the person now (physically) dead, not merely to comply with something that the deceased had consented to.

Donors’ consideration of survivors’ preferences

Most participants seemed confident that surviving loved ones would have no qualms about implementing their body donation wishes. Some believed that everyone they cared about would happily do so: “[Tom: So, everybody’s on board, that you care about?] Yes (Briggite, 786–787). Others recognized that implementation of their body donation wishes might have negative consequences for surviving loved ones, but nevertheless thought that their own wishes should be prioritized:

It can cause difficulty for families, based on the length of time that your body is used. [It] could be three years later before they get to attend a cremation. That kind of delay can alter the grief process. If that’s a wish [i.e., if body donation were to be Marigold’s desire], and that [i.e., disruption in relatives’ grieving process] just happens to be a result, then they would, hopefully, truly understand and accept. (551-563)

[Tom: How do you reconcile those two? “I want to help science” but “Here are my kids that I might be being selfish about.”] I think, if I keep mentioning it throughout my life, it’ll be, “That’s what mum’s wishes are”, so I’m sure that will trump anything else. (105-110)

Although keen to become a body donor and to let others know that this was her desire, Mel prioritized allowing her surviving partner freedom to choose whether to implement her body donation wishes:

Everybody I know knows what I think. If, when the time comes, my partner decides not to donate me, then that’s their choice. (163-164)

Thus, most people felt that relatives should honor their body donation wishes, despite some recognizing that this might be difficult for them. In this regard, Mel was the exception. Having made sure that others knew what her wishes were, her preference that her partner should retain his own autonomy trumped her (very firm) desire to become a body donor.

Preference hierarchies and conditions

Participants’ body donation wishes seemed rarely, if ever, unconditional. Although Brigitte had already registered body donation willingness, her preference was that her body would not be donated for posthumous examination:

I have registered to become a body donor [but] I hope I’m not a body donor because I would prefer my useful body parts to be used for organ transplant. (34) Body donation has got a particular place to play when you’re older, when you know that you’re going to die. (46)

As well as fitting into preference hierarchies, some participants’ body donation willingness also seemed conditional on what they thought would or might happen to their donated bodies, or what consequences would or might follow from that:

I don’t really mind who I help (440), within the HTA Terms of Scheduled Purpose (470-472). [Some] people donate their bodies when they know they’re going to be used as crash test dummies or put out to rot, to work out maggot times. I don’t fancy it. (746-752) In your death, you want things. You want to be helpful in a way that I find comfortable thinking about in my living state. (762-764)

Mel similarly wanted her donated body to be useful although, when pressed, she came to wonder whether her preferences might be slightly more specific than this:

[Tom: Do you care about what happens?] To my physical body? No, not at all. I don’t care at all. (533-536) Anybody who can learn their anatomy, I’m happy because it’s all about learning the anatomy. [Tom: Okay. And there’s no limits to this, if you were to be used for weapons research for example?] (552-559) Hmm. It depends on what we mean by weapons research. I’m thinking amputation rather than, “How much of this do we need to blow a body up; to maim somebody?” (569-573)

Emma’s (potential) body donation willingness seemed likely to be conditional in the same way:

Trauma surgeons for the military – if that’s what you mean by weapons research, then fine, but if you’re building a better exploding weapon or something, then yeah, I think I would draw a line there. (580-583) [It] never occurred to me that a donation could be used for nefarious purposes. (598-600)

Emma and Mel also gave some striking examples of priorities among people they had dealt with professionally:

I’ve had a couple of calls from people who’ve said, “Hi, I’m just about to kill myself. I just wanted to make sure you’ve got my paperwork and you can come and pick me up.” (853-856)

What you can say to these people, is “If you do take your own life, we can’t accept you, because you’ll have to have a postmortem.” They say, “Really? Oh.” (872-874)

These people potentially prioritized their bodies being donated even over declared intentions to imminently end their own lives. This seems reflective of a general pattern suggesting that people’s desires for body donation might best be thought of as conditional, i.e., preferences for some rather than other outcomes in relatively specific circumstances.

Determining people’s preferences and permissions

Participants varied in the steps they had taken to ensure that others knew their body donation preferences. Emma and Marigold were not currently intending to register body donation willingness and had not discussed such a possibility with those closest to them (Emma 150, Marigold 950).

Like Mel (103,162), Brigitte had registered body donation willingness and discussed her wishes with loved ones:

I’m registered for both [i.e., body and posthumous organ donation]. (53) My family know what my wishes are. We’ve had a lot of discussions about it. (61-64)

Sally had declared an intention to become a body donor to her family but, following their initial reaction to that declaration, had not subsequently discussed her preferences in detail:

I’ve got the consent form but I haven’t had it witnessed. It’s with my will. (21-22) My eldest daughter will be in charge. (161-162) [Tom: Did you say that you had or haven’t spoken about it to them [i.e., Sally’s children]?] Just a throwaway line, but they don’t really know. (213-216)

Although participants varied in the methods and the extent to which they had documented and communicated their body donation willingness or desire, none seemed to have done much to document or communicate their specific wishes and preferences concerning things that might be done to their bodies, by whom, and to what ends. However, a substantial part of the interview with Marigold, an anatomist, explored her understanding of donors’ preferences and permissions. Her overall view seemed to be that people’s registration of body donation willingness could typically be considered sufficient evidence of a “fundamental desire to help” that justified an assumption of consent for any procedure that might realistically occur during posthumous examination.

The day list [of donated bodies] have signed up to anatomical examination and some of them don’t know what we do, and they were fine with that. (274-284) When you do things that are quite, er, challenging, so sawing someone’s head in half, I do think, you know, “Did that person really know that this is what was going to happen to them?” [Tom: How do you deal with that?] It comes back to the fundamental thing that they wanted to help other people learn and understand about the human body and if the need was to cut someone’s head in half to see into it, then that’s the need. (302-311)

When asked a hypothetical question, Marigold suggested that she might take a different approach if she were to agree to examine the body of someone she had known when they were alive:

I don’t think I would want to, unless it was their explicit wish and then, of course, I would just do it. (245-246) You’d wonder what they wanted to be used for. I know it’s within the Consent but would they really want to be dissected by students? Would they want to be turned into a skeleton? Would they want their head kept in a pot for the next 200 years? (255-267) There is granularity, so I’d like to know. (287-288)

Here, unlike with the bodies of actual donors she dealt with, Marigold recognizes the possibility of donors having (had) preferences for things not to happen despite them being allowed by the formal consent process. Marigold speculated about possible reasons for this difference:

It would be personal. You know people as them. I just don’t think I could emotionally detach myself. (207-226) You have got a vested interest in that individual. So, there is an emotional attachment to make sure that you would do what they wanted within that Consent. (338-341)

Later in her interview, Marigold explored ways of obtaining more detailed information about donors’ specific preferences:

I do wonder if we’ll get to a point where greater granularity is added to the donation forms. (833-834) I’d like it, from an ethical point of view. From a sector perspective, it would be really difficult. (840-845) It would mean that we wouldn’t be able to accept so many donors, because they wouldn’t match what we need them for at that time, [e.g.,] if someone said they wanted to be kept whole. (856-864)

Seemingly in response to this perceived tension between facilitating documentation of donors’ specific desires and meeting professional supply needs, Marigold considers a second alternative to the current consent procedure:

Or, when people give consent, the Information Pack says all these types of things that they may be used for, and they accept that it could be any one of those. More in the pack. I think that would be a really positive step, because people want knowledge and transparency. (869-979)

Regardless of methods by which it might be achieved, Emma and Mel did not share Marigold’s preference for improving the specificity of consent among prospective body donors. This was because their priority was to avoid people having to consider potentially distressing possibilities, perhaps unnecessarily:

I personally don’t think they need to know everything. The anatomists think they need to know absolutely every detail. They’re talking from a very educated [perspective]. (795-797) I don’t think it would be useful for them to know that their body’s cut into chunks. We have some saying “Oh, I don’t care what they what they do. They can cut me into a million pieces”, and that’s fine. And then there’s others that say, “No thanks, I don’t want to hear.” I would almost lobby against it, but that would be saying we’re doing something that’s not right. (810-823)

And their families don’t need to know that level of detail. A third [of a donated body] comes back in the coffin [on completion of posthumous examination] and I don’t think families need or would want to know that. I think they’d be traumatized by that. (803-808)

Participants therefore had various views about how consent procedures could best serve donors’, relatives’, anatomists’, and ethical needs.

Changing preferences

Half of the sample (Emma, Marigold, and Sally) were not yet ready to register body donation willingness but thought that their preferences might change over time or circumstance:

If I live a few more decades or if I was diagnosed with something terminal, I’d probably think a bit more deeply about it then. (54-56) I’m not really ready to think about it. (72)

Emma also noted that her preferences about what she would like to happen to her body posthumously had changed in the past:

I used to think, “Oh, I’d love to be one of those Gunther von Hagens shows. That’s so cool.” But now, having done this job, I feel less certain. (49-52) I think that was without knowing the ins and outs of what it actually meant. It was more of a superficial, like, “That’s really cool”, kind of thing. (63-65)

Brigitte described how it had felt when something that she had apparently actively requested was implemented following her father’s body donation:

There was a phone call two years later saying, “Do you want to come to the cremation? It’s in two days’ time.” It was very out of the blue. I was walking round Ikea at the time. When you fill in the form, there are various checkboxes like, “Do you want to know when the cremation is?” There was a whole series of questions. It was difficult because it was literally two days later, and I had a lot of other commitments. (561-576) It was painful because it threw everything back up again. (635-636) Two years later, it’s like a sudden death’s come out of the blue. So that was a bit difficult. It was kind of, “I didn’t need to be dealing with it again.” (640-647) I may’ve ticked the box; I don’t know. Even if I did tick the box, maybe my thoughts have moved on since. Maybe ticking that box is no longer relevant to me. Actually, what’s more important is how I feel now. The feeling right now is, “No, I don’t need to go to the cremation.” (662-669)

In discussing the relative merits of different options for indicating preferences about such things, Brigitte said:

Maybe what would be good is to get a three-month warning: “In three months’ time, it’s likely that the body will be cremated. Now how do you feel? Do you want to know or not?” Because at the point when you’re signing to the point where it actually happens is a major difference, because you’ve gone through so much. It’s only afterward you’re going to know. You don’t know beforehand. (685-693)

Participants’ preferences concerning body donation and related matters therefore clearly had the potential to change over time. Moreover, Brigitte provided one impactful example of this happening, with the result that she experienced considerable distress upon the implementation of something that she had consented to – or perhaps even requested – only a couple of years previously.

Discussion

We interviewed six people involved or invested in posthumous body donation about their thoughts and feelings concerning the possibility of donating their body posthumously. Our aim was to discover what we could about their motives and preferences. Qualitative analysis of their transcripts identified common concerns that we felt related to issues of agency, consent, and autonomy.

During interviews and analysis, it was sometimes difficult to be confident about what action or event was being discussed when phrases such as “become a body donor” were used. Such phrases sometimes seemed to refer to living people who had indicated willingness for their bodies to be posthumously donated and sometimes to dead people whose bodies had been successfully donated. At least pedantically, each of these uses seemed to risk veering toward paradox or incoherence by referring to people who had not yet donated as “donors” or to people who had died as engaging in intentional actions such as “donation”. (See Davies, Citation2022 for one potential reason for the latter.) This in turn resulted in uncertainty about the relationships participants perceived between stating willingness for posthumous donation, donation occurring, and donors’ agency and autonomy.

Not being able to initiate actions after one’s death does not necessarily preclude the possibility of posthumous agency and autonomy. Ronald Dworkin (Citation1993) famously proposed the notion of “precedent autonomy”, where a person communicates preferences for what happens to their body later. When others’ actions are guided by a person’s preferences, those proxy agents’ actions can in some circumstances be thought of facilitating the autonomy of the person on whose behalf they are acting (Bandura, Citation2018). Dworkin’s proposal sparked intense and important debates about the appropriateness of facilitating precedent autonomy in various situations where people’s preferences may have significantly changed since their earlier declarations, e.g., following dementia or similar (Buller, Citation2015; Maclean, Citation2006). Precedent autonomy is perhaps less contentious in the case of posthumous body donation because most people believe that the dead have no material preferences (Callahan, Citation1987) and that it is sometimes appropriate to act in the interests of people who have died (McGuinness & Brazier, Citation2008). Acting in accordance with dead people’s living wishes may therefore be thought of as facilitating their “posthumous autonomy”.

Notwithstanding debates about ownership of people’s dead bodies (Herring & Chau, Citation2007), all participants felt that surviving loved ones should have at least the opportunity to support dead people’s (living) body donation preferences. Indeed, most participants felt that loved ones should seek satisfaction of those preferences even if doing so conflicted with their own preferences, thus implying that dead people’s precedent autonomy should sometimes trump living people’s current autonomy. One participant recognized the possibility of other stances. She was keen for her partner to know her wishes and therefore have the option of acting as a proxy agent for her, but nevertheless wanted him to decide if this was what he wanted to do. This participant therefore recognized the possibility of prioritizing the autonomy of the living over that of the dead, even when fully aware of the dead’s living preferences (Wilkinson, Citation2014). This is consistent with UK law, which states that people can express preferences about what happens after their death but that these preferences need not always be enacted by those who survive them (Conway, Citation2018).

Later facilitation of people’s preferences is most confidently achievable if those preferences are known or easily inferred. Although participants were aware that consenting to body donation meant that donors’ dead bodies could be temporarily passed into the stewardship of anatomists and subsequently examined, their awareness of and levels of comfort with what might happen beyond this sometimes seemed relatively unclear, i.e., in terms of who might and should be allowed to do what to donated bodies, and with what purposes and consequences. This seemingly “referentially opaque” (Manson, Citation2013) relationship between consent and desires was most thoroughly explored in the interview with “Marigold”. In her work as an anatomist, Marigold acts on the assumption that donors are motivated by a “fundamental desire to help” and that this justifies an assumption of consent for anything instrumental to that end – despite occasionally wondering how they would have felt about some of the things done to their donated bodies. When considering the possibility of working on the body of a donor she had known personally, Marigold thought that she would worry about whether the donor would have in fact wanted various specific things that were incontestably captured by the current consent procedure. Faced with such a possibility, Marigold felt that she would refuse to act in any way unless she was confident that she knew that a specific action or outcome was what the donor had wanted. Such differentiation between what people have consented to and what they wanted or would want makes stark the difference between being empowered or constrained by a (deemed) permission and being given the opportunity or responsibility to act as a proxy agent. The former may protect aspects of a person’s autonomy but the latter seems better able to facilitate active support of it. With such a distinction in mind, some consent procedures risk being seen as producing binding contracts that do more to serve anatomists’ needs than to facilitate support of donors’ autonomy (Dunn, Citation2016; Gathani et al., Citation2016).

Permissions granted by the current consent process therefore seem not to optimally capture the complexity and nuance of participants’ concerns. This suggests that Marigold may have been justified in wondering about the relationship between some of the things she did and donors’ preferences. This might not be a problem if donors are in fact motivated by the fundamental and unqualified desire to help that Marigold assumes. However, the unconditionality of this assumption seems questionable because some participants had concerns in addition to desires to be helpful that placed limits on what they would like and would be willing to facilitate as a result of their own body donation (Cooper et al., Citation2020).

One option to try to improve the correspondence between donors’ preferences and what might happen to their donated bodies would be extend and make more detailed the information available in consent documentation. This seemed to be Marigold’s preference, but it was not shared by other participants who believed that participants would not benefit from acquiring the breadth and depth of information that this would require. How informed consent can and should be is of course a long-running and on-going debate that is unlikely to be much affected be the results of a single study (Boyd, Citation2015; Corrigan, Citation2003). In this respect, our results merely serve as a reminder that people with others’ interests at heart can reach incompatible conclusions about how to best to serve those (perceived) interests.

A second option would be to offer potential donors choices about how much information they wanted to have access to prior to consent. Something similar happens when people register willingness to posthumously donate organs in the UK. This is done via a website (https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/) and people can provide consent for donation either after reading minimal information or after a detailed trawl of the extensive information available on that website. The site also provides contact details to allow access to clarification or further information.

The way that people give consent for organ donation suggests additional possibilities to facilitate autonomy in body donation (and elsewhere). Instead of providing their own advance consent, potential donors can nominate a representative to make decisions on their behalf later. For several reasons, this seems a particularly useful potential option in cases of posthumous body donation. First, there can be an extended time between statements of consent and donation occurring, and donors’ ability to competently amend their earlier declarations will often diminish over time (Jongsma & van de Vathorst, Citation2015). Secondly, relatives are likely in to be in a good position to know what their deceased loved ones wanted at a time relatively close to their death, whereas consent forms for body donation potentially serve the precedent autonomy of people from a much earlier time. Donors’ preferences may have changed during that period and donors at the earlier time may not have even had preferences concerning technologies likely to have developed since then. Thirdly, body donation usually requires loved ones’ involvement already, because surviving friends or relatives must take steps soon after their loved one’s death to ensure that donation happens. With such involvement required, it is perhaps, at worst, a slight additional burden for nominated agents to declare what the donor wanted (or would have wanted) to happen to their body once donation was achieved. Fourthly, nomination of delegates can require consent from those delegated for that delegation. This seems to formalize recognition of relatives’ involvement in comparison to current procedures (where relatives may only find out about loved one’s donation decisions after the latter’s death) and also seems likely to initiate discussions between potential donors and their nominated relatives that will clarify for both parties what donors’ specific preferences are.

Any change in procedures to obtain consent for body donation has the potential to influence the number of people donating and also what they consent to. Some worry that this might negatively impact supply of a valuable resource and so it would of course be prudent to research people’s attitudes toward any proposed changes to the current system. However, if secure supplies are to be prioritized over optimizing donors’ posthumous autonomy, it would seem disingenuous to pretend otherwise. The latter goal is, after all, only one moral good that is potentially relevant (Bach, Citation2016; Wilkinson, Citation2014).

The current study explored the views of a relatively small group of relatively distinct people with regards to a very specific domain of possible behavior. We make no claims about how representative those views may be of other people’s views or of views relating to different behaviors (Larkin et al., Citation2019). We also acknowledge that the relevance of many of our points will differ with respect to specific donation laws and practices (Morla González et al., Citation2021), and that the latter may sometimes have unclear or uneasy relationships with each other (Matesanz & Dominguez-Gil, Citation2007). This also means, of course, that the relevance of many of our comments may change if relevant laws and practices change. Nevertheless, our results seem potentially relevant in many if not most situations where issues of consent or autonomy are relevant, and not only in the domain of body donation. After all, unless it is literally contemporaneous, all consent is precedent, i.e., based on earlier evidence of preferences or permissions, albeit sometimes established very recently (Maclean, Citation2007). However, our results seem most likely to be relevant to situations where consent is established at one time but the actions consented to at that time may be performed much later, potentially after considerable changes in both circumstances and donors’ preferences. In those sorts of situations, if we want to protect or serve people’s interests, perhaps even posthumously, it seems wise to contemplate the longevity of “historical” consent and, if appropriate, seek more current information that might confirm or amend that obtained at an earlier time.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude and thanks to our participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Anonymized transcripts showing Autonomy and Rationality GET coding, and illustrative analytic “memos”, are available at https://osf.io/wrnkz/

References

- Andow, J. (2016). Qualitative tools and experimental philosophy. Philosophical Psychology, 29(8), 1128–1141. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2016.1224826

- Bach, M. C. (2016). Still human: A call for increased focus on ethical standards in cadaver research. HEC Forum : An Interdisciplinary Journal on Hospitals' Ethical and Legal Issues, 28(4), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-016-9309-9

- Bandura, A. (2018). Toward a psychology of human agency: Pathways and reflections. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617699280

- Barbour, R. S. (2001). Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? British Medical Journal, 322(7294), 1115–1117. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115

- Boulton, M., & Parker, M. (2007). Informed consent in a changing environment. Social Science & Medicine, 65(11), 2187–2198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.002

- Boyd, K. (2015). The impossibility of informed consent? Journal of Medical Ethics, 41(1), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2014-102308

- Bristow, W. (2017). Enlightenment. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/enlightenment

- Buller, T. (2015). Advance consent, critical interests and dementia research. Journal of Medical Ethics, 41(8), 701–707. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2014-102024

- Callahan, J. C. (1987). On harming the dead. Ethics, 97(2), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1086/292842

- Champney, T. H., Hildebrandt, S., Jones, G. D., & Winkelmann, A. (2018). BODIES R US: Ethical views on the commercialization of the dead in medical education and research. Anatomical Sciences Education, 12(3), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1809

- Chan, S. W., Tulloch, E., Cooper, E. S., Smith, A., Wojcik, W., & Norman, J. E. (2017). Montgomery and informed consent: Where are we now? British Medical Journal, 357, j2224. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2224

- Conway, H. (2018). Frozen corpses and feuding parents: Re JS (disposal of body). The Modern Law Review, 81(1), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2230.12319

- Cooper, J., Harvey, D., & Gardiner, D. (2020). Examining consent for interventional research in potential deceased organ donors: A narrative review. Anaesthesia, 75(9), 1229–1235. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15039

- Cornwall, J. (2016). The ethics of 3D printing copies of bodies donated for medical education and research: What is there to worry about? The Australasian Medical Journal, 9(1), 8–11. https://doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2015.2567

- Corrigan, O. (2003). Empty ethics: The problem with informed consent. Sociology of Health & Illness, 25(7), 768–792. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-9566.2003.00369.x

- Davies, J. (2022). Explaining the illusion of independent agency in imagined persons with a theory of practice. Philosophical Psychology, 36(2), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2022.2043265

- Dunn, M. (2016). Contextualising consent. Journal of Medical Ethics, 42(2), 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103381

- Dworkin, R. (1993). Life’s dominion: An argument about abortion, euthanasia, and individual freedom. Knopf.

- Emba, C. (2022, March 17). Opinion: Consent is not enough. We need a new sexual ethic. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/03/17/sex-ethics-rethinking-consent-culture/

- Farsides, T., Smith, C. F., & Sparks, P. (2021). Beyond “altruism motivates body donation”. Death Studies, 47(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.2006827

- Fjellstrom, R. (2005). Respect for persons, respect for integrity. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 8(2), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-004-7694-3

- Gathani, A., Moorlock, G., & Draper, H. (2016). Pre-mortem interventions for donation after circulatory death and overall benefit: A qualitative study. Clinical Ethics, 11(4), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477750916657658

- Grady, C., & Longo, D. L. (2015). Enduring and emerging challenges of informed consent. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(9), 855–862. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1411250

- Gruber, A. (2016). Consent confusion. Cardozo Law Review, 38(2), 415–458.

- Habicht, J. L., Kiessling, C., & Winkelmann, A. (2018). Bodies for anatomy education in medical schools: An overview of the sources of cadavers worldwide. Academic Medicine, 93(9), 1293–1300. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000002227

- Helgesson, G., & Eriksson, S. (2011). Does informed consent have an expiry date? A critical reappraisal of informed consent as a process. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 20(1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0963180110000642

- Herring, J., & Chau, P. L. (2007). My body, your body, our bodies. Medical Law Review, 15(1), 34–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/medlaw/fwl016

- Horn, R. (2014). “I don’t need my patients’ opinion to withdraw treatment”: Patient preferences at the end-of-life and physician attitudes towards advance directives in England and France. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 17(3), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-014-9558-9

- HTA. (2020a, May 20). Code A: Guiding principles and fundamental principle of consent: Code of practice. Human Tissue Authority. Retrieved from https://www.hta.gov.uk/guidance-professionals/codes-practice-standards-and-legislation/codes-practice

- HTA. (2020b, December 7). Guiding principles and the fundamental principle of consent: Guide for the general public to Code of Practice a. Human Tissue Authority. Retrieved from: https://www.hta.gov.uk/guidance-public/public-guides-hta-codes-practice

- HTA. (2021, December 6). How to donate your body. Human Tissue Authority. Retrieved from: https://www.hta.gov.uk/guidance-public/body-donation/how-donate-your-body

- HTA. (2022, April 1). Body donor cards. Human Tissue Authority. Retrieved from: https://www.hta.gov.uk/guidance-public/body-organ-and-tissue-donation/body-donation-medical-schools/body-donor-cards

- Jongsma, K. R., & van de Vathorst, S. (2015). Dementia research and advance consent: It is not about critical interests. Journal of Medical Ethics, 41(8), 708–709. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2014-102445

- Larkin, M., Shaw, R., & Flowers, P. (2019). Multiperspectival designs and processes in interpretative phenomenological analysis research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 16(2), 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1540655

- Maclean, A. R. (2006). Advance directives, future selves and decision-making. Medical Law Review, 14(3), 291–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/medlaw/fwl009

- Maclean, A. R. (2007). Advance directives and the rocky waters of anticipatory decision-making. Medical Law Review, 16(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/medlaw/fwm019

- Manson, N. (2013). Informed consent and referential opacity. In D. Archard, M. Deveaux, N. Manson, & D. Weinstock (Eds.), Reading onora O’Neill (pp. 89–103). Routledge. ISBN 9780415675987 .

- Mason, J. K., & Laurie, G. T. (2001). Consent or property? Dealing with the body and its parts in the shadow of Bristol and Alder Hey. The Modern Law Review, 64(5), 710–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2230.00347

- Matesanz, R., & Dominguez-Gil, B. (2007). Strategies to optimize deceased organ donation. Transplantation Reviews, 21(4), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trre.2007.07.005

- McGuinness, S., & Brazier, M. (2008). Respecting the living means respecting the dead too. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 28(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqn005

- Morla González, M., Moya Guillem, C., Delgado Rodríguez, J., & Molina Pérez, A. (2021). European and comparative law study regarding family’s legal role in deceased organ procurement. Revista General de Derecho Público Comparado, 29. Retrieved from. https://philpapers.org/rec/MOREAC-11

- Nizza, I. E., Farr, J., & Smith, J. A. (2021). Achieving excellence in interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): Four markers of high quality. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1854404

- O’neill, O. (2003). Some limits of informed consent. Journal of Medical Ethics, 29(1), 4–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.29.1.4

- Oxburgh, G. E., Myklebust, T., & Grant, T. (2010). The question of question types in police interviews: A review of the literature from a psychological and linguistic perspective. International Journal of Speech, Language & the Law, 17(1), 46–66. https://doi.org/10.1558/ijsll.v17i1.45

- Prabhu, P. K. (2019). Is presumed consent an ethically acceptable way of obtaining organs for transplant? Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 20(2), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143718777171

- Sibley, A., Sheehan, M., & Pollard, A. J. (2012). Assent is not consent. Journal of Medical Ethics, 38(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2011-100317

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2021). Interpretive phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Sommers, R. (2019). Commonsense consent. The Yale Law Journal, 129, 2232. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2761801

- Tamminen, K. A., Bundon, A., Smith, B., McDonough, M. H., Poucher, Z. A., & Atkinson, M. (2021). Considerations for making informed choices about engaging in open qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(5), 846–886. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676x.2021.1901138

- Thompson, K. (2023). Qualitative methods show that surveys misrepresent “ought implies can” judgments. Philosophical Psychology, 36(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2022.2036714

- Uniacke, S. (2013). Respect for autonomy in medical ethics. In D. Archard, M. Deveaux, N. Manson, & D. Weinstock (Eds.), Reading onora O’Neill (pp. 104–120). Routledge. ISBN 9780415675987 .

- Wilkinson, T. M. (2014). Respect for the dead and the ethics of anatomy. Clinical Anatomy, 27(3), 286–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.22263

- Zealley, J. A., Howard, D., Thiele, C., & Balta, J. Y. (2022). Human body donation: How informed are the donors? Clinical Anatomy, 35(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23780