Abstract

This article contests the emphasis that is frequently placed upon child-friendly methods in research with young children. Focusing upon a series of research encounters from a doctoral study of play in an early years classroom, I examine my interactions with the children and their social and material worlds and draw upon these encounters to highlight some emergent and unpredictable elements of research with young children. I argue that these elements call for a decreased emphasis upon the implementation of method towards an openness to uncertainty and an ethical responsiveness to the researcher’s relations with children and their everyday lives. An ethical responsiveness to uncertainty has implications throughout the research process, including through the ways in which we choose to read, interpret and present the data. This article offers original contributions to contemporary debates regarding what might become possible when uncertainty is acknowledged and embraced in research with young children.

Introduction

Ellie, aged five, curls her body upon the sofa, an arm resting on her mother’s leg as we use a laptop to watch the video recording from last week at school. In the recording, Ellie is playing with Saffron; they are making playdough sausage rolls and chocolate cakes for a birthday party. The recording has captured excited voices as Ellie welcomes imaginary guests to the party: Yorkshire accents transform to American voices; a red lace dress and silver shoes replace a navy blue uniform. Ellie sits between me and her mother, watching as the party unfolds on the screen. She stretches a hand towards the laptop, points at the green playdough food, slides off the sofa and runs out of the living room. Her mother turns to me, laughing – “sorry, she’s so tired after school, she’s got no attention left”. We chat amiably about Ellie and Saffron’s adoption of American accents, their love for all-things-Disney and Ellie’s fifth birthday party. Ellie appears at the living room door with an apron and a bowl, saying “we bake cakes, don’t we mum?” The conversation shifts to cakes; Ellie describes her birthday cake, throwing her arms out wide to indicate its hugeness. We look at a photo of the cake on her mother’s phone; I comment on the strawberry topping and Ellie, jumping up and down, squeals in delight as she recalls the strawberries that are growing in a pot on the kitchen doorstep. We move outside to eat strawberries.

This vignette is based upon field notes from my doctoral research (Chesworth, Citation2014) in which I used video recordings as a provocation for exploring children’s, parents’ and teachers’ perspectives of play in an early years classroom. The episode highlights some ways in which Ellie’s responses to watching the recording of her play were interwoven with her relationships and interactions with(in) the material and social context of her home. The example is indicative of the fluid and unexpected encounters that emerged as I explored the children’s perspectives of play. The data I collected were often ephemeral; the process of data collection was not clearly defined or distinct, but instead merged with the everyday-ness of children’s lives. As a novice researcher, this was sometimes an unsettling process because it did not align with the seminars I had attended on qualitative research, nor with the literature I was reading about methods for involving young children. The field notes from my visit to Ellie’s home are illustrative of the ways in which my encounters with children and their families invited me to reconsider my understanding of what constitutes method, data and ethics in research with young children.

In this article, I revisit a series of encounters from my study in order to present an original analysis of some issues and considerations associated with young children’s involvement in research. With this in mind, I do not intend to present a formula for engaging with young children as research participants. Rather, I aim to make visible some of the unexpected dilemmas, challenges and opportunities that I encountered which have required me to re-examine what it means to ‘do research’ and to recognise the uncertainty associated with research methods, ethical engagements and the interpretation of young children’s perspectives. Thus, this article draws upon original insights from my study of play to present a case for acknowledging and embracing uncertainty in research with young children. In so doing, I argue for a shift in the focus of attention from method towards a more reflexive consideration of the ontological, epistemological and ethical questions regarding the researcher’s engagement with children and their everyday lives. As such, I position my discussion within a body of international literature that problematises the dogmatic application of methods and which instead sets out to explore the possibilities and uncertainties of moving towards a methodology for early childhood research that,

seeks encounters, in which the research itself, both its practices and its findings, might emerge as something new, something not-yet-thought. Such encounters do not foster research practices that engage in methodical rule-following, and they do not impose or presume a moral framework. Rather they open up a moment- by-moment ethical questioning that asks how things come to matter in the ways they do. (Davies et al., Citation2013, p. 680)

This article, then, presents a case for recognising the possibilities that emerge when we embrace uncertainty in research encounters with young children. But, I also want to argue for a more pervasive appreciation of how uncertainty permeates throughout the research process; of how our interpretations of the significance of findings, and of how those findings are constructed, are not fixed, but ever-emerging. To illustrate this, my discussion will include some indication of how I have re-turned (Barad, Citation2014) to my earlier readings of my research encounters with children. As Lennon (Citation2017, p. 55) suggests, this process ‘allows different understandings, different feelings and different subjectivities to emerge’ and suggests that researchers have an ethical responsibility to make visible the inherent uncertainties of interpretation. I will return to this point later, but first I discuss the broader context in which research with young children is situated.

Research with young children

Recognition of young children’s competencies and agency (Prout & James, Citation1997) has been associated with an assertion that children’s perspectives are key to understanding aspects of their own lives (Mayall, Citation2000). Hence, recent years have seen a proliferation in the development of ‘child friendly’ methods that seek to contribute to the transition from research ‘about’ or ‘on’ children towards research ‘with’ children (Waller & Bitou, Citation2011). Multi-method, visual research tools such as the Mosaic approach (Clark & Moss, Citation2011; Clark, Citation2017) have made an important contribution to acknowledging the multiple modes in which young children communicate and make meaning. However, an emphasis upon method runs the risk of reductionist approaches to research with children, in which child-friendly tools are applied as taken-for-granted and guaranteed formulae for eliciting children’s experiences and perspectives (Gallacher & Gallagher, Citation2008; Palaiologou, Citation2014). As Law (Citation2004) suggests, the academy’s preoccupation with method is steeped in a problematic ‘singularity: the idea that there are definite and limited sets of processes’ (p. 9) that will lead us to discover a truth that is ‘out there’, waiting to be discovered. Furthermore, within an imposed research design (Waller & Bitou, Citation2011), there is a tendency for task-based methods to define and limit the terms for children’s engagement with adults determining where and how children are able to engage in the research process (Holland, Renold, Ross, and Hillman, Citation2010).

The adoption of child-friendly methods runs the risk of imposing fixed and homogenous identities upon children that, as Thomson (Citation2007) argues, reinforce the hierarchical structures associated with notions of empowerment, ‘giving voice’, and the binary constructions of the powerful adult and the powerless child. As such, an over emphasis upon method may inadvertently serve to regulate spaces for interaction and to restrict, rather than enable, children’s involvement during the research process.

I have found Deleuze and Guattari’s (Citation1987) conceptualisation of the smoothing and striation of spaces helpful in enabling me to theorise my shifting ideas regarding research interactions with young children. According to Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987, p. 554), smooth spaces are ‘an amorphous collection of juxtaposed pieces that can be joined together in an infinite number of ways’. Within smooth spaces, actions and interactions do not occur in relation to a fixed trajectory or sequence; rather, they can be thought of as emergent, shifting and in a constant state of flux, enabling bodies to ‘interact and transform in endlessly new ways’ (Hohti, Citation2016, p. 1151). When applied to a research context, smooth spaces are characterised by a non-linear, uncertain methodology that evolves and unfolds in unforeseen directions through a series of interconnected encounters. By contrast, striated spaces are structured spaces in which ‘actions are prescribed’ (Hansen, Hansen, & Kristensen, Citation2017, p. 2) and are consequently restrained and regulated by specific aims or practices such as those associated with predetermined research frameworks and methods. Deleuze and Guattari understand smooth and striated spaces as co-existent and interdependent (Holland, Citation2013), constantly combining and interweaving in ways in which ‘smooth space is constantly being translated, transversed into a striated space; striated space is constantly being reversed, returned to a smooth space’ (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987, p. 474). Hence, a researcher might intentionally avoid ‘setting up norms of appropriate engagement’ (Gallacher & Gallagher, Citation2008, p. 507) and instead seek to operate nomadically (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987) within a smooth space, exploring new territories for ethical engagement with children. Nevertheless, classroom practices and the wider social and cultural discourses within which such practices reside will always contribute to the interplay of smoothing and striation of the spaces in which research takes place. Furthermore, I argue that the interwoven processes of smoothing and striation require an acknowledgement of the complex, relational characteristics of research with young children. This invites a rejection of simplistic assumptions which imply that smooth spaces always enable children to enact agency and that striated spaces are fundamentally repressive. Rather, I argue that researchers need to be reflexive to the co-existing and dynamic processes of smoothing and striation and the effects they produce in our research.

The study context

My professional background as a teacher of young children acted as the initial motivation for commencing my doctoral research. As a teacher working in the English education system, I had become concerned with the ways in which I was required to regulate children’s play in order to meet a series of learning goals that were prescribed by a national curriculum framework. Through my research, I set out to contest instrumental notions of play by exploring the dynamic meanings and motivations that children, their parents, siblings and teachers ascribed to play in a reception class located in a small town in Northern England. In the English education system, the reception class constitutes a transition point for 4- and 5-year old children between non-statutory, preschool provision and compulsory schooling. This has resulted in tensions and debates about the purpose of the reception class that have been fuelled by a neoliberal policy-driven emphasis upon externally imposed outcomes, universal notions of learning (Wood, Citation2014) and school readiness (Ang, Citation2014). Basing my research within a reception class consequently afforded a complex political backdrop for exploring perspectives of play.

Over an 8-month period, I spent one morning per week filming episodes of five children’s play in the reception class. Filming took place for approximately 3 hours, depending upon the changing daily routines within the classroom, and focused upon one child per week. All play activities in which the focus child participated within the 3-hour period were recorded, with the exception of those that were excluded at the children’s request or for other ethical reasons. The recordings became a provocation through which to explore the children’s, families’ and teachers’ perspectives as they selected episodes of play to watch and respond to during my visits to the school and to the children’s homes. This approach drew upon the seminal video-cued, multivocal ethnographic studies of Tobin, Wu, and Davidson (Citation1989) and Tobin, Hsueh, and Karasawa (Citation2009), an approach I adapted and extended to embrace non-vocal, embodied and emplaced (Pink, Citation2009) modes of meaning-making.

Filming and ethics

Throughout the 8-month period of fieldwork, I viewed the children’s assent to participate as ongoing, flexible and provisional (Flewitt, Citation2005). As such, once parents had given their informed consent, children sometimes opted to withdraw from the research on a temporary or, in one case, a permanent basis. Filming children’s play raises ethical questions (Flewitt, Citation2005) and I was mindful that listening to children’s perspectives could be construed as intrusive and contributing to a culture of surveillance (Einarsdottir, Citation2011). Filming became an ethical practice and required me to recognise that visual imagery is inevitably a social construction (Thomson, Citation2008). Use of the camera necessitated a reflexive consideration of how children and their play were presented in the recordings and at the beginning of the research period, the children and I agreed upon a ‘thumbs up, thumbs down’ sign by which they could indicate their willingness to be filmed, or conversely to request that I stop filming. Initially, this was useful in building up trusting relationships; at first, children tested my credentials by showing the ‘thumbs down’ signal and observing whether I stopped filming. However, the need for this rather formal signal became less relevant as the children and I became attuned and responsive to the camera’s presence. I always waited for a sign of permission and avoided filming any situations when the children did not appear to have noticed me. Sometimes a child would ask that I did not use the camera that day, or request that I waited until ‘after I’ve done this’. These flexible approaches to engaging with the children enabled their temporary withdrawals from the research process to be acknowledged and respected.

Having established the context for the research, I now draw upon extracts from my field notes to discuss four encounters that are illustrative of some elements of uncertainty-in-action. Whilst the study included adult and child participants, this article focusses primarily upon selected encounters between the children and me. The examples that follow indicate some ways in which the research can be understood as an emergent navigation of the challenges and opportunities that the children and I encountered during our explorations of play. Such an approach required me to be reflexive to the ethical dilemmas and methodological decisions that emerged throughout the research. As Pillow (Citation2003, p. 179) suggests, reflexivity requires that the dilemmas and problems that occur during fieldwork are no longer ‘viewed as incidental but can become an object of study themselves’. Throughout the discussion, I suggest some implications of acknowledging uncertainty for research practices involving young children. Whilst acknowledging that the use of pseudonyms in research dissemination is a debated subject (Dockett, Einarsdottir, & Perry, Citation2011), the children’s names in the encounters that follow have been changed to respect their privacy.

Encounter 1: negotiating research relationships

This morning I shared the information booklet with Lucy (aged four) and she signed her consent with a large letter L. I asked her if she had any more questions, to which she responded with no hesitation, “Have you got any pets?” My initial reaction was to offer a hasty response and to re-focus Lucy’s attention upon my intended interpretation of the question in relation to the research process. However, Lucy persisted with her line of enquiry, asking “What do you like best – cats or dogs?” And so we chatted about pets. I shared my preference for cats over dogs; Lucy disagreed and argued that you can’t take a cat for a walk. I told her that I had two pet chickens. Lucy confided that she wanted her dog to be a bridesmaid at her mum and stepdad’s wedding.

In this encounter, Lucy’s question established a connection between us in a way that I had not anticipated. The image-based information booklets documented a commitment to respecting the children’s choices regarding participation; however, they held limited value in isolation of the conversations which they stimulated between the children and me. For example, the final page of the booklet invited children to ask me any questions that they might have about their involvement in the research. This page was often re-interpreted by the children and frequently became a stimulus to ask questions about my home, family, pets and life experiences. Such questions may initially appear incongruent to the research and could suggest the children’s inability to understand the context in which the invitation for questions had been offered. However, these questions acquire alternative meanings when one considers them in relation to the children’s motivation to make connections with me, perhaps through establishing common interests, knowledge and experiences.

This example indicates one way in which the children contributed to the research in ways that were unplanned and emergent. Lucy’s re-interpretation of the purpose of the information booklet is illustrative of the ways in which the children ‘drew me into their community, and connected me to it’ (Davies, Citation2014, p. 16). As we sat together talking about pets, Lucy and I experienced a mutual attentiveness to each other’s everyday lives. Through such encounters, I endeavoured to become open to the unforeseen conversations that unfolded with the children. I became aware of the possibilities that emerged when I resisted the urge to define our relationships within familiar binary segments (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987) of what it means to be an adult or a child, a teacher or a pupil, a researcher or a participant, within the context of an early years classroom. Nevertheless, my role as a researcher did not exist in isolation of my previous experiences and, as Bettez (Citation2015, p. 939) suggests, my avowed commitment to respectful relationships with the children required me ‘to first be thoughtful about the assemblage of our identities in relation to the assemblages of others’. In my former role as a teacher I had been required to engage with children for specific purposes, and I realise that there are numerous ways in which a researcher’s past ‘infects the witnessing of the ethnographic present’ (Jones, Holmes, MacRae, & MacLure, Citation2010, p. 488). My teacher identity was made visible throughout the minutiae of my participation in classroom life and the interplay of my researcher and teacher identities contributed to the constant smoothing and striating of the spaces in which my relationships with the children emerged.

Encounter 2: uncertain directions

The following conversation took place during a visit to five-year old Molly’s home. Molly, her mum –Dawn - and I were watching a video recording in which Molly and a group of peers were taking turns to jump from a circular arrangement of logs that were fixed into the playground surface.

Dawn: How high are these logs, Molly?

Molly: Well. Very high. But don’t worry mum, we can do it. And the little ones, well they jump off the little logs.

Dawn raises her eyebrows, laughing, and continues to watch the recording.

Molly: Don’t worry mum I don’t fall off (turns to look at me) D’you know, I can jump all the way from here (points to sofa) all over to that chair where you are.

Dawn: Yes, but you know what we say about jumping on sofas. Hmm? (puts her arm around Molly; glances at me, smiling).

Molly: Mum, can I take Liz into the garden and show her how I jump on the trampoline? I can jump really high, can’t I?

Dawn: Yes, we can go into the garden, if that’s OK with you, Liz? I’ll get the key.

Dawn leaves the room. Molly, giggling, raises her body to stand on the sofa. She lifts her arms, launches into the air, and lands on the soft velvet cushion next to me.

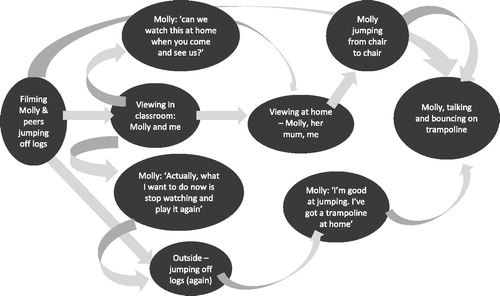

This encounter is indicative of the children’s unpredictable responses to watching the recordings of their play. Molly’s conversations with her mum, her jumping between chairs and her keenness to show me the trampoline in the garden contributed to a multiplicity of responses through which to explore play in ways that recognised the materiality and emplaced characteristics of children’s meaning-making. The absence of predetermined methods facilitated a capacity to follow ‘the scent’ (Bennett, Citation2010, p. xiii) of the children’s diverse responses to watching the recordings of their play. In (below), I have mapped Molly’s multiple engagement with the Jumping off Logs footage, using arrows to indicate the flow and connectedness of her different responses to viewing the footage at home and in the classroom.

This re-presentation is illustrative of Hohti’s (Citation2016, p. 1151) description of smooth research space in which ‘bodies can interact and transform in endlessly new ways’. But, who, and what, constitutes the ‘bodies’ that participate in these encounters? My initial analysis discussed the ways in which elements of the physical environment (the trampoline in the garden, the chairs in the living room) afforded opportunities for the children to make-meaning of the connections between their play and the cultural practices of home and school. I suggested that the choices the children made regarding how to respond to the videos were expressions of agency. However, I have subsequently become interested in the ways in which new materialist philosophies, and specifically Barad’s (Citation2007) theory of agential realism, offer potential to shift the ways in which we engage with young children’s worlds. Barad’s (Citation2007, p. 152) suggestion that ‘matter and meaning are mutually articulated’ has prompted me to revisit my initial interpretations of children’s expressions of agency. This is leading me to consider a more distributed reading of agency which emerges through the intra-actions between children and the socio-material worlds they inhabit (Lenz Taguchi, Citation2010).

Whilst a comprehensive discussion of new materialism is not the focus of this article, I refer to it here to illustrate an important point about uncertainty in research. I am a relative outsider in my explorations of new materialism and I frequently retreat to more familiar theoretical territory, yet the ideas with which I am engaging unsettle and prod at the analysis presented in my thesis. Events that were unnoticed move into focus and my readings of ‘agency’ and ‘perspectives’ shift as I investigate new lenses through which to think about the children’s responses to the filmed footage. As qualitative researchers, our interpretations are always situated within the affordances and constraints of the theoretical frameworks within which we choose to work. We have an ethical responsibility to acknowledge the partial and uncertain nature of interpretation and to undertake our research in ways which strive to make visible ‘what is being made to matter, and with what effect’ (Davies, Citation2014, p. 82).

Encounter 3: discussing David. Navigating the ethics of participation

Today I’ve been watching Daniel’s play film with Daniel (aged four) and Lucy (aged four). In the film, Daniel is outside, playing with Peter: they are lying inside a crawl-through plastic tunnel and rolling down the slope.

Daniel: We’re both crashing. Oh, stop kicking me. Stop kicking me Peter (pauses film, very long silence). Peter. Well, he’s not actually my friend. Well, actually he is my good, good friend but, but sometimes it’s hard to be his friend.

Lucy: Why?

Daniel: Well. He’s always mean to me.

Lucy: Do you tell him off?

Daniel: Not always.

Lucy: Tell him off. Peter is mean, Peter is mean.

Daniel: (giggling, joins in) Peter is mean. Pete is mean.

Peter has come inside. I think he might have heard the conversation. He comes over.

Peter: I’m not actually mean to him (directed towards Lucy).

Daniel: You are (blushes). You are sometimes.

Peter: I’m not (frowning, arms folded).

In this encounter, I recall feeling uncomfortable about Daniel and Lucy’s use of the film to discuss Peter. This example exemplifies the interwoven processes of smoothing and striation and illustrates several dilemmas that I encountered during my research. What should a researcher do in situations in which children appear to be exercising power in ways that are potentially hurtful, disrespectful or oppressive? Should I have intervened and, if so, at what point? Is it ethical to restrict children’s responses to those which convey kindness or similar positive attributes? Conversely, is it ethical to do nothing? In this encounter, the research created a space for dissent in which the power relationships between Daniel and Peter were acknowledged and subsequently unsettled. Daniel’s alliance with Lucy provided a context in which he was able to consider his interactions with Peter. However, Daniel and Lucy’s conversation also included an element of ridicule that I found uncomfortable to witness.

I opted to intervene when Peter became upset and started to cry. I stopped the film, comforted Peter. Daniel, familiar with the rituals of apology, said he was sorry and attempted to hold Peter’s hand. The matter was quickly resolved, yet I remained uncertain regarding my response. During my time in the classroom I had frequently seen Peter exercising control over Daniel; I could understand why Daniel said that Peter was mean. By comforting Peter, was I suggesting my disregard for Daniel’s feelings? This episode exemplifies the ongoing ethical uncertainties that I experienced throughout my research and illuminates the need to act beyond the implied certainty of the university ethical review process through which researchers must present a case for their ethical credentials prior to commencing fieldwork. Of course, the formal protocols and procedures of the institutional ethical review process have a role to play in upholding values of informed consent, confidentiality and anonymity. Institutional ethics panels also serve to protect children from unscrupulous research agendas and it is therefore understandable that the notion of methodological uncertainty could provoke some uneasiness. However, the focus on the procedural aspects of research instils a tick-box certainty to ethical considerations. The notion of gaining ethical consent and beginning one’s fieldwork does not acknowledge the complex ways in which ethics are caught up in the dynamic, relational elements of research. By contrast, Barad (Citation2011, p. 150) argues for recognition of an ‘ethics of entanglement’ in which the relational and dynamic qualities of ethics are emphasised. This conceptualisation cuts through the certainty of the ethical approval process and requires that the researcher’s role moves beyond responsibility to a more intra-active ‘response-ability’ (Barad, Citation2012, p. 208). My presence implicated me within the complex network of classroom relationships; I was not a neutral onlooker and I acted accordingly.

Encounter 4: Rapunzel in the garage – uncertain interpretations

In this final vignette I discuss five-year old Riley’s responses to watching a filmed episode of play in which he was playing with three boys. The children were constructing a go-kart from wooden blocks and plastic crates. A girl, Daisy, arrived in the construction area and attempted to join in the play. At school, Riley wanted his friend, Robbie, to watch the footage with him. Robbie had not been part of the go-kart play. When Daisy appeared on the screen he paused the film, turned to Riley and asked, “Is that a girl? Riley replied, “Oh yeah, she’s got a ponytail there.” He paused, touching his head. “Rapunzel hair.” Later in the afternoon, I noticed Riley waving his hand, as if to beckon me. I approached him, kneeling on the carpet to be at his level. Riley moved his face towards my ear, touched my hair, and whispered, “Rapunzel was in the garage”, before running outside.

The following week I visited Riley’s home and we watched the go-kart footage with his parents:

Riley, pauses the film, frowning, looks at Craig (dad): She ruined it, ruined the kart.

Riley, still frowning, thumps his fist on his leg.

Craig: It doesn’t look like she’s ruining it. Looking closely at screen.

Lisa (mum): Girls can work in garages, Riley.

Riley: Girls can work in garages. Yeah?

Lisa: Yeah they can, Riley. That’s right.

Riley: I let her play.

I recall that I was fascinated by Riley’s different responses to watching Daisy’s arrival in the film and I wanted to be able to account for these different responses. I retreated to my professional teacher training and the familiar territories of developmental psychology to interpret Riley’s contrasting responses to watching the films as being indicative of the disequilibrium he was experiencing in relation to his understanding of gender. I was dissatisfied with this explanation and it was at odds with the theoretical ideas I was drawing upon in my research. But at the time, I felt the need to provide a theoretical explanation for these differences and to account for the ‘absence of singularity’ (Law, Citation2004, p.61). My training in qualitative methods required me to seek validity through triangulation. However, as Law (Citation2004, p. 61) argues, a rejection of singularity ‘does not imply that reality is fragmented. Instead, it implies something more complex. It implies that different realities overlap and interfere with one another.’ Understood as such, children’s perspectives are dynamic and always-emerging. This recognition invites us to re-consider our relationship with data and to embrace the discomfort of ‘moments of disconcertion’ when ‘at the point of analysis, and coding, we can’t find rational ways of accounting for them’ (MacLure, Citation2013, p. 172). Three years after the completion of my PhD, I am struck by my desire to return to these moments of disconcertion, to revisit the data and to ‘dive into its strata of mysteries, contradictions, and complexities’ (McCoy, Citation2012, p. 769) in order to acknowledge the inherent uncertainty and dynamic characteristics of interpretation.

Uncertainty in research with young children

The encounters discussed in this article indicate some ways in which young children’s involvement in research can be understood to be emergent, dynamic and unpredictable. This has significant implications for those of us who choose to enter young children’s worlds as researchers. We do not enter as neutral onlookers, but instead become part of the places and spaces that children inhabit, through which our encounters with children constitute ‘a process of transformation where you lose absolutely the possibility of controlling the final result’ (Rinaldi, Citation2006, p. 184). In this study, the video recordings of the children’s play became provocations for ‘multiple entanglements of actions, meanings, and materialities’ (Blaise, Citation2016, p. 618), an approach that required openness to the emerging ideas that arose from the children’s unpredictable and multiple modes of engagement with the research. Within these contexts, children enacted agency through their intra-actions (Lenz Taguchi, Citation2010) with people, space and materials, including the recordings of play. Such an approach to involving children in research invites consideration of an expanded notion of agency in which the focus shifts from ‘empowering’ individual children towards a more dynamic appreciation of how agency operates within and throughout the relationships and intra-actions that constitute children’s everyday lives. As such, children’s perspectives of play were enacted in multiple modes and places: gathered together on floor cushions in the classroom; in the garden as children bounced on the trampoline; whilst drinking cups of tea within the midst of busy family living rooms.

On the one hand, my intention in this article is to illuminate the possibilities that open up when we succumb to uncertainty in our research encounters with young children. On the other hand, I also wish to emphasise that research as an ethical practice requires us to acknowledge, act upon and make visible the elements of uncertainty that permeate throughout the research process. In part, this constitutes an alertness and responsiveness to the dynamic relationships and interactions associated with the research encounter. These micro-ethical moments (Guillemin & Gillam, Citation2004) do not occur in isolation; rather, they are caught within the interconnected and ever-evolving interactional networks of the homes, classrooms and wider social, cultural and political contexts within which research is situated. Acknowledgement of these relational and ethical elements shifts the emphasis from research as method towards research as ethical praxis (Palaiologou, Citation2014). This necessitates that researchers make visible ‘the specific nature of dilemmas encountered in situ, the decision-making processes involved, the actions taken, and the affective responses to these’ (Graham, Powell, & Taylor, Citation2015, p. 331).

Ethical praxis also involves making visible the means by which we come to know. Law (Citation2004, p. 153) suggests that a central concern here is the need to be reflexive to ‘our own unavoidable complicity in reality-making’. However, Lenz Taguchi (Citation2010) argues that reflexivity is insufficient because it separates the researcher from that which is being researched. Instead, Lenz Taguchi (Citation2010) draws upon Barad’s (Citation2007) concept of diffraction which she uses to turn the gaze away from the researcher towards her entanglements within the intra-actions of the research encounter. Nevertheless, I maintain that the practice of ‘uncomfortable reflexivity’ (Pillow, Citation2003, p. 175) makes an important contribution to ethical praxis because it requires us to confront and acknowledge the uncertain and messy elements of our research. In particular, I am in support of Elwick, Bradley, and Sumsion’s (Citation2014) call for researchers to engage critically with methods which claim that it is possible to know with certainty how very young children experience their worlds.

Looking towards future uncertainties

In this article, I have argued for a shift in the focus of attention from the formulation of child-friendly methods towards a relational and emergent approach to research with young children. Such an approach contributes to understandings of children’s involvement as being dynamic and enacted. Looking forward, it is important that we continue to imagine alternative ways of engaging with young children in order that their involvement in research does not striate but continues to evolve. As such, this article offers original contributions regarding the possibilities and dilemmas that emerge through embracing the uncertain terrains of research with young children. Whilst the arguments presented in this article will be of particular interest for researchers in the field of early childhood, they have wider significance for qualitative researchers who seek to contest the current emphasis upon standardised, instrumental measures of what is deemed to be worthy or valid in contemporary educational research. Implicit in this instrumental agenda is an assumption that selecting appropriate methods will enable researchers to capture, display and proffer authentic voices as empirical evidence within a system that is increasingly driven by ‘what works’ imperatives. By contrast, a key argument in this article is that researchers have an ethical responsibility to recognise and make visible the elements of uncertainty in the processes through which participants’ voices are produced, interpreted and re-presented.

Uncertain methodologies, closely interwoven with epistemological and ontological considerations, are not without challenges and require the researcher to maintain a reflexive and ethical stance within and throughout the relationships that unfold through the research process. Such an approach requires flexibility and considerable investment in time. This may pose some dilemmas in relation to the constraints and demands of research proposals and timescales that require the researcher to ‘outline the doing before she begins’ (Lather & St Pierre, Citation2013, p. 630). Nevertheless, such methodologies invite us to move beyond the well-trodden terrains of child-friendly methods to explore the worlds of young children in ways that are not-yet thought.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Liz Chesworth

Liz Chesworth is a lecturer in Early Childhood Education at the University of Sheffield. She is interested in the dynamic meanings and motivations that children ascribe to their play and how these may present alternative readings of play to those located within curriculum and policy frameworks. Liz has drawn upon children’s perspectives to explore issues of power, agency and choice within early childhood classroom cultures. She is interested in children’s play in relation to the diverse socio-material contexts of home and school.

References

- Ang, L. (2014). Preschool or prep school? Rethinking the role of early years education. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 15, 185–199. doi:10.2304/ciec.2014.15.2.185

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. (2011). Nature’s queer performativity. Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences, 19, 121–158. doi:10.5250/quiparle.19.2.0121

- Barad, K. (2012). On touching—the inhuman that therefore I am. Differences, 23, 206–223. doi:10.1215/10407391-1892943

- Barad, K. (2014). Diffracting diffraction: Cutting together-apart. Parallax, 20, 168–187. doi:10.1080/13534645.2014.927623

- Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bettez, S.L. (2015). Navigating the complexity of qualitative research in postmodern contexts: Assemblage, critical reflexivity, and communion as guides. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28, 932–954. doi:10.1080/09518398.2014.948096

- Blaise, M. (2016). Fabricated childhoods: Uncanny encounters with the more-than-human. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 37, 617–626. doi:10.1080/01596306.2015.1075697

- Chesworth, L. (2014). Multiple perspectives of play in a reception class: Exploring insider meanings (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Leeds Beckett University.

- Clark, A. (2017). Listening to young children: A guide to understanding and using the mosaic approach (3rd ed.). London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Clark, A., & Moss, P. (2011). Listening to young children: The mosaic approach (2nd ed.). London: National Children’s Bureau for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Davies, B. (2014). Listening to young children: Being and becoming. London: Routledge.

- Davies, B., De Schauwer, E., Claes, L., De Munck, K., Van De Putte, I., & Verstichele, M. (2013). Recognition and difference: a collective biography. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26, 680–691. doi:10.1080/09518398.2013.788757

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus. London: Bloomsbury.

- Dockett, S, Einarsdottir, J. & Perry, B. (2011). Balancing methodologies and methods in researching with young children. In D. Harcourt, B. Perry, & T. Waller (Eds.), Researching young children’s perspectives: Debating the ethics and dilemmas of educational research with children (pp. 68–81). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Einarsdottir, J. (2011). Icelandic children’s early education transition experiences. Early Education and Development, 22, 737–756. doi:10.1080/10409289.2011.597027

- Elwick, S., Bradley, B., & Sumsion, J. (2014). Infants as others: Uncertainties, difficulties and (im)possibilities in researching infants’ lives. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27, 196–213. doi:10.1080/09518398.2012.737043

- Flewitt, R. (2005). Conducting research with young children: Some ethical considerations. Early Child Development and Care, 175, 553–565. doi:10.1080/03004430500131338

- Gallacher, L. A., & Gallagher, M. (2008). Methodological immaturity in childhood research? Thinking through participatory methods. Childhood: A Global Journal of Child Research, 15, 499–516. doi:10.1177/0907568208091672

- Graham, A., Powell, M.A., & Taylor, N. (2015). Ethical research involving children: Encouraging reflexive engagement in research with children and young people. Children and Society, 29, 331–343. doi:10.1111/chso.12089

- Guillemin, M., & Gillam, L. (2004). Ethics, reflexivity and ethically important moments in research. Qualitative Inquiry, 10, 261–280. doi:10.1177/1077800403262360

- Hansen, S.R., Hansen, M.W., & Kristensen, N.H. (2017). Striated agency and smooth regulation: Kindergarten mealtime as an ambiguous space for the construction of child and adult relations, Children's Geographies, Advance online publication, 15, 237–248. doi:10.1080/14733285.2016.1238040

- Hohti, R. (2016). Time, things, teacher, pupil: Engaging with what matters, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29, 1148–1160. doi:10.1080/09518398.2016.1201610

- Holland, E. W. (2013). Deleuze and Guattari’s a thousand plateaus: Readers’ guide. London: Bloomsbury.

- Holland, S., Renold, E., Ross, N.J., & Hillman, A. (2010). Power, agency and participatory agendas: A critical exploration of young people’s engagement in participative qualitative research. Childhood: A Global Journal of Child Research, 17, 360–375. doi:10.1177/0907568210369310

- Jones, L., Holmes, R., MacRae, C. and MacLure, M. (2010). Documenting classroom life: How can I write about what I am seeing? Qualitative Research, 10, 479–491. doi:10.1177/1468794110366814

- Lather, P., & St Pierre, E.A. (2013). Post-qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Research in Education, 26, 629–633. doi:10.1080/09518398.2013.788752

- Law, J. (2004). After method: Mess in social science research. London: Routledge.

- Lennon, S. (2017). Re-turning feelings that matter using reflexivity and diffraction to think with and through a moment of rupture in activist work. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30, 534–545. doi:10.1080/09518398.2016.1263885

- Lenz Taguchi, H. (2010). Going beyond the theory/practice divide in early childhood education: Introducing an intra-active pedagogy. London: Routledge.

- MacLure, M. (2013). Classification or wonder? Coding as an analytic practice in qualitative research. In R. Coleman & J. Ringrose (Eds.), Deleuze and research methodologies (pp. 164–183). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Mayall, B. (2000). Conversations with children: Working with generational issues. In P. Chistensen & A. James (Eds.), Research with children: Perspectives and practices (pp. 120–135). London: Falmer Press.

- McCoy, K. (2012). Toward a methodology of encounters: Opening to complexity in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 18, 762–772. doi:10.1177/1077800412453018

- Palaiologou, I. (2014). ‘Do we hear what children want to say?’ Ethical praxis when choosing research tools with children under five. Early Child Development and Care, 184, 689–705. doi:10.1080/03004430.2013.809341

- Pillow, W. (2003). Confession, catharsis, or cure? Rethinking the uses of reflexivity as methodological power in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 16, 175–196. doi:10.1080/0951839032000060635

- Pink, S. (2009). Doing sensory ethnography (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

- Prout, A. & James, A. (1997). A new paradigm for the sociology of childhood? Provenance, promise and problems. In A. James & A. Prout (Eds.), Constructing and reconstructing childhood (pp. 7–33). London: Falmer.

- Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, researching and learning. London: Routledge.

- Thomson, F. (2007). Are methodologies for children keeping them in their place? Children’s Geographies, 5, 207–218. doi:10.1080/14733280701445762

- Thomson, P. (2008). Doing visual research with children and young people. London: Routledge.

- Tobin, J., Hsueh, Y., & Karasawa, M. (2009). Preschool in three cultures revisited: China, Japan, and the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Tobin, J., Wu, D. Y. H., & Davidson, D. (1989). Preschool in three cultures: Japan, China, and the United States. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Waller, T., & Bitou, A. (2011). Research with children: Three challenges for participatory research in early childhood education. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 19, 5–20. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2011.548964

- Wood, E. (2014). The play-pedagogy interface in contemporary debates. In L. Brooker, M. Blaise, & S. Edwards (Eds.), The Sage handbook of play, learning and early childhood (pp. 145–156). London: Sage.