Abstract

This study presents the use of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) as both a theory and methodology that operationalizes Discursive Violence (DV). Gleaning from 19,000 pages of discovery of a 2013–2014 court case, Smith et al., v. Henderson et al., this study explores the intersection of discursiveness and school reform policy; positing that permanent school closures are an example of violence against African-American students because of the discursive practices that steer these closures. In this study, Smith et al., v. Henderson et al. as a milieu to illustrate how CDA and DV can be employed methodologically. This study asks how discursive practices that steer school closures present as discursive violence and how can discursive violence be used to understand school closures in a predominately African-American and urban school district? Analysis shows how discursive practices deployed during the proposed closure of 20 Washington, D.C. public schools legitimized and normalized discursive violence against African-American students.

Literature review

A primer on violence

On August 15, 2015, American Civil Rights activist Julian Bond died. Bond, arguably, was one of the most radical Civil Rights leaders, often making controversial yet poignant statements when observing the welfare of African-American and poor American citizens. For example, in his 1972 book, A Time To Speak, A Time to Act: A Movement in Politics, Bond wrote, “violence is Black children going to school for 12 years and receiving 6 years’ worth of education” (p. 13). Without empirical evidence, yet with experiential knowledge, most African-Americans would not hesitate to agree with this fifty-year-old proclamation. Why is that? Why would most African-Americans recognize this proclamation as valid without, perhaps, empirical evidence? Because, for African-Americans, violence is proverbial to the Black experience (McMillian, Citation2018).

Black’s Law Dictionary (Garner, Citation2014) defines violence as the use of physical force accompanied by fury, vehemence, or outrage, especially with intent to harm. Black’s Law Dictionary goes on to expound on its definition of violence by citing contemporary legal arguments that have extended its definition of violence, contending that violence is not limited to physical contact or injury but may include erroneous publicity, false statements, picketing with misleading signs, and veiled threats by words and acts (Garner, Citation2014). Violence is commonly understood to mean physical force; however, violence is evolving into a binary term inclusive of both literal and symbolic forms. Legal scholarship asserts that words and actions carry within them the potential to inflict as much harm to individuals as physical contact—expanding violence from a literal sense to include the symbolic or semiotic representation of violence (Garcia-Villegas, Citation2003). In legal scholarship, symbolism carries with it the physical manifestations of violence. Also, it considers the relationship between violent acts and the import of the aftermaths felt by the individual or a specific populace—allowing arguments for figurative language that have both pragmatic and symbolic forms that can be interrogated. Furthermore, because violence is an affront to humankind, “the concept of violence must be broad enough to include the most significant varieties, yet specific enough to serve as a basis for concrete action” (Galtung, Citation1969, p. 168).

Violence in public education

For years, scholars have embraced symbolism and semiotic representation as necessary for bridging knowledge gaps and for novel conceptualization. Symbolism should not be considered a process to produce subjective meaning but rather a modality of interpreting context (Eco, Citation1986). Therefore, the use of abstract language to describe human experience should be accepted as a creditable lens. In education scholarship, Arnold et al. (2014) described metaphors as tools of representation and other scholarship has long explored the use of metaphors when explaining a phenomenon in education, using terms like failing to mentor Sapphire (Smith, Citation1999), left back (Ravitch, Citation2001), crossing over to Canaan (Ladson-Billings, Citation2001), dreamkeepers (Ladson-Billings, Citation2009), learning in a burning house (Horsford, Citation2011), passed along (Mawhinney et al., Citation2016), death by a thousand cuts (Journey For Justice Alliance, Citation2014), and many more.

This semiotic form of violence is not a new concept within education scholarship. Education scholarship has uncovered racialized inequities that African-American students experience during their elementary, middle, and secondary education tenure. The most salient themes include the academic debt and opportunity gap between African-American students and their White peers (Jackson, Citation1982; Jencks & Phillips, Citation1998; Klein, Citation2002; Ladson-Billings, Citation2006; Lomotey, Citation1990; Rebell, Citation2006; Rothstein, Citation2004; Wiener, Citation2006; Wing, Citation2002), the disproportionate placement of African-American students in special education settings (Ford & Russo, Citation2016; Glennon, Citation1995; Russo & Talbert-Johnson, Citation1997; Saucedo, Citation1992; Thompson, Citation2014), the disparities of school discipline and suspension rates among African-American students (Brick, Citation2009; Cartledge et al., Citation2001; Mendez & Knoff, Citation2003; Wald & Losen, Citation2003) and discipline disparities among African-American girls (Watson, Citation2018); the lack of access to rigor curricula and instruction (Ford et al., Citation2001; Heise, Citation2006; Levin, Citation2006; So, Citation1992), teacher quality (Darling-Hammond, Citation2000; Desimone & Long, Citation2010; Haskins & Loeb, Citation2007), inequitable school funding (EdBuild | 23 Billion, Citation2019), and inequitable and neoliberal educational policies (Au, Citation2009; Lipman & Haines, Citation2007; Renzulli & Evans, Citation2005; Saltman, Citation2015; Watkins, Citation2015).

While the scholars mentioned above empirically substantiated inequity, the use of the term violence had not been associated with their scholarship. Frantz Fanon (Citation1963) established a terminology foundation of violence within education, stating that any action or practice prohibiting a student from learning is an act of violence. These same epistemological thoughts are reflected in Epp and Watkinson’s (Citation1997) work, which described how the systemic structure of public education alongside inequitable practices, impede students’ learning opportunities and manifest as violence.

Using the pedagogy of Fanon (1963), the work of Leonardo and Porter (Citation2010) is an initial example of contemporary research in education that advances traditional notions of violence. Leonardo and Porter (Citation2010) positioned violence as a tactic to challenge the dehumanizing effects of racism. Within their context, violence became an offensive weapon to protect against the proprietor of racism. Leonardo and Porter (Citation2010) refer to violence as a counter method to students of color harsh and debilitating educational realities. In their article, the nomenclature of violence calls for a vast movement toward unearthing or redefining education—a movement that began with Fanon. Whether violence is the offensive weapon we employ or a contrivance of white supremacy, those of us who engage educational violence, symbolically, must do so with courage and endurance because of mounting opposition. Aggarwal, Mayorga, and Nevel (Citation2012) and Keisch and Scott (Citation2015) also advanced traditional notions of violence by identifying education reform policies as conduits of structural violence; yet, these bodies of literature did not operationalize violence within public education. Thus, education scholarship demonstrates that not only is public education faced with new forms of inequities, but also education scholarship is faced with an epistemological need to reframe emerging and persistent inequities in public education. To this end, I present discursive violence.

Discursive violence, what is it?

Discourse is more than traditional understandings of linguistic concepts that demonstrate transitions of thought or dialogue. Social theorists like Michel Foucault, Jürgen Habermas, and Norman Fairclough argue that discourse is language-in-use (Hall, Citation1997) and that discourse is something not easily defined because of its praxis (Fairclough, Citation2010). Habermas argues that discourse can operate in manners that preserve power and ideologies, and a hermeneutical approach to discourse positions one to interrogate the social contract and its reinforcement and reproductions of power within society (Habermas & Viertel, 1975). Outlining Foucault’s discursive approach to language and representation, Hall writes:

Discourse is about the production of knowledge through language. But since all social practices entail meaning, and meanings shape and influence what we do—our conduct—all practices have a discursive aspect. It is about language and practice. It attempts to overcome the traditional distinction between what one says (language) and what one does (practice) (Hall, Citation1997, p. 72).

Methodology: operationalizing discursive violence

Critical discourse analysis as theory and methodology

Operationalizing discursive violence and examining how violence exists discursively within public education is an essential lens to understand the current state of public education within the United States. Social theorists recognize that social ills must be exposed and contested (Fairclough, Citation2010; Rogers, Citation2011; Wodak & Meyer, Citation2015). The overall objective of CDA is to analyze how language plays its role in hegemony, social power. Critical discourse studies argue that transparency is a primary way to demand social change. Social theorists recognize the vital impact of language on societal functions, implicating language and power as systemic and constitutive characteristics of society (Fairclough, Citation2010, p. 126). While a historical Foucauldian perspective focuses on the symbolic relationships of discourse and discursive practices (Willig, Citation2015), other researchers have examined discourse in its pragmatic shape (Hall, Citation1997; Wodak & Meyer, Citation2015). Both perspectives are salient to operationalizing discursive violence and as functional constructs that inform the application of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) (Fairclough, Citation2010) as a theory and methodology.

CDA is a powerful analytical tool that centers on how social power operates through language. Language, in CDA, is multimodal; it includes video, text, talk, and practices (Fairclough, Citation2003). Fairclough (Citation2010) identified hegemony—the dominance of a social group over another—as a culprit of discursive inequity, stating that “the hegemony of a class or group over an order of discourse is constituted by a more or less unstable equilibrium between its constitutive discursive practices” (p. 130). Other methodologists of critical discourse analysis (Buchanan, Citation2008; Maingueneau & O'regan, Citation2006) suggested the origin of power—whether social, political, or economic—possessed by a group and the preservation of that power rest within the use of spoken language and language-in-use, both of which construct social norms. According to Fairclough (Citation2010), the study of social power and discourse are salient and defining elements in social and political discursive practices (Fairclough, Citation2010, p. 131).

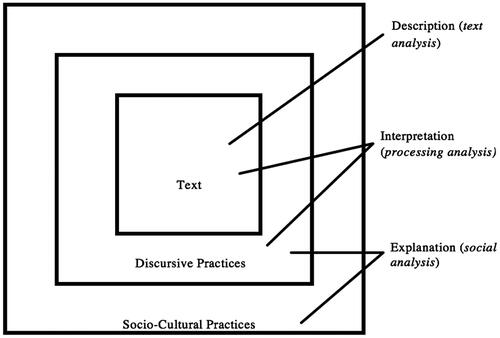

Fairclough (Citation1992, Citation2010) used a three-dimensional discourse analytical tool to verify the existence of social power within a “complex social event” or “discursive event” (Fairclough et al. 2002, p. 94). These dimensions were text, discursive practice, and social practice. Based upon this model, Fairclough (Citation2010) suggested that these domains are interdependent and reflect the establishment, reproduction, and negotiation of the realities of those involved in the discursive event. While each dimension is co-dependent, each level of discourse necessitates a unique form of discourse analysis when analyzing power. illustrates Fairclough’s (Citation1992, Citation2010) dimensions of discourse and critical discourse analysis. Fairclough (Citation1992) wrote:

Figure 2. Fairclough’s (Citation1992, Citation2010) dimensions of discourse. Note. Fairclough's (Citation1992, Citation2010) dimensions of discourse (labeled within the boxes) and the respective dimensions of discourse analysis (labeled to the right of the boxes).

Each are indispensable for discourse analysis. These are the tradition of close textual and linguistic analysis within linguistics, the macro-sociological tradition of analyzing social practice in relation to social structures, and the interpretivist or micro-sociological tradition of seeing social practice as something which people actively produce and make sense of on the basis of shared commonsense procedures (p.72).

Fairclough’s (Citation1992, Citation2010) three-dimensional conception of discourse and three-dimensional method of critical discourse analysis is an approach “that sets out to make visible through analysis, and to criticize, connections between properties of texts, social processes and ideologies which are generally not obvious” (p. 132). Each dimension represents the embedded layers of discursive, social, and cultural practices that shape and influence society. As illustrated in , text, discursive practice, and socio-cultural practice operate synchronously and represent language in discursive forms, the production and interpretation of the language form, and the social implications of the language form, respectively. Fairclough (Citation2010) wrote:

The method of discourse analysis includes linguistic description of the language text, interpretation of the relationship between the (productive and interpretative) discursive processes and the text, and explanation of the relationship between the discursive processes and the social processes (p. 132).

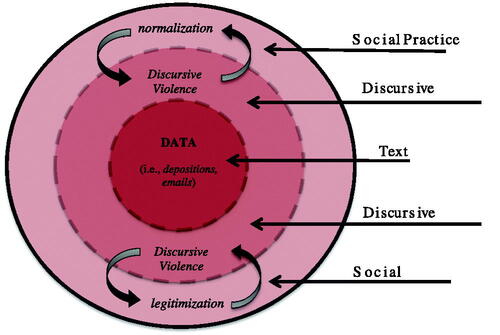

CDA is also a useful methodological framework when analyzing how discourse evolves over time in institutions. For example, studying how discursive violence operates within our public school and judicial system is another way to illustrate how African-American and other students of color continue to experience inequity. This study explores the intersection of discursiveness and school reform policy, positing that permanent school closures are an example of violence against African-American students because of the discursive practices that steer these closures. This study asks, how do discursive practices that steer school closures present as discursive violence, and how can discursive violence be used to understand school closures in a predominately African-American and urban school district? Expanding upon Fairclough’s discursive model, I offer the framework in :

is an aggregate visual interpretation of the conceptual and methodological frameworks created to facilitate the operationalization of discursive violence. This adaptation of Fairclough’s model serves as a framework to examine the power a class or system may have over another class and how this imbalance of power manifests within society through discursive practice (Fairclough, Citation2010). Informed by CDA, I maintained Fairclough’s (Citation2010) methodological approaches, positioned on the right, because they bound analytical classification for each discursive level. The segmented lines represent the various entry points of discursive violence and its conciliatory practices within the constructs of legitimization and normalization. Additionally, this three-dimensional framework underscores the intentionality of explicit or implicit discursive practices that create inequitable educational experiences. Finally, this adaptation is designed to examine the interdependence of text, discursive practice, and social practice experienced by African-Americans.

Background

The Washington D.C. Public School context

Located as they are in the capital of the United States of America, Washington, D.C. public schools should be the vanguard for equity in public education and an international exemplar of Western education. Instead, public schools in Washington, D.C., are rife with inequities and serve as a microcosm of public education systems across the United States. Historically, wards across Washington, D.C. have displayed significant racial and economic disparities. Perhaps symbolic of the interlocking and contiguous political, economic, social, and education systems that confound administrative responsibility, D.C. has no voting power in the United States Congress. This lack of political capital makes D.C. a case ripe for examining networking social systems, discursiveness within those systems, and education reform policy.

Attempts to improve public education within the United States often occur through education reform policy. However, education reform policies, especially the implementation of them, are often met with dissension from parents, teachers, students, and concerned community members (Lipman & Haines, Citation2007). This dissension could be attributed to its [reform policy] intention to create equitable educational experiences, however, its outcome often creates the opposite and exacerbates preexisting inequities. This study explores the intersection of discursiveness and school reform policy situated within the litigious dissension between parents and community organizers and Washington, D.C. Public Schools (DCPS) after DCPS announced its proposed closure of 20 public schools. This study presents school closures as a backdrop to foreground discursive violence.

School reform in Washington, D.C., has rarely occurred without dissension. Since the early 1950s and 1960s, D.C.’s approach to education reform policies has been examined closely by the D.C. District Court (McMillian, Citation2018)—indicating a contentious and litigious relationship between DCPS and its community members. Appointed by then-Mayor Adrian Fenty in 2007 as the first chancellor of DCPS, Michelle Rhee perceived DCPS to be in “dire situation” (Rhee, Citation2012, p.39). Rhee’s appointment as DCPS Chancellor was met with community skepticism and protest, in that while Rhee had some education experience, she was an outsider and had no prior experience with DCPS or experiential knowledge of the Washington, D.C. context (Fullard, Citation2013). Without regard to the possible origin of the "dire situation," Rhee accredited DCPS problems' crux was attributed to its teachers. Rhee believed engineering a teacher-evaluation system and permanently closing 23 DCPS schools was the most prudent course to revitalize DCPS (Smith v. Henderson, Citation2013). In 2010, Michelle Rhee resigned as Chancellor of DCPS. Rhee’s successor was Kaya Henderson and she served as Chancellor of DCPS from 2010 until 2016.

Smith et al. v. Henderson et al.

Similar to her predecessor, Kaya Henderson supported the evaluation of teachers, and after Henderson was appointed chancellor of DCPS in 2013, she proposed closing 20 more public schools in Washington, D.C. Both Rhee’s and Henderson’s school closure and consolidation policies impacted neighborhoods east of Rock Creek Park—neighborhoods that were gentrifying and whose students were leaving public schools to enroll in competing charter schools. For this reason, plaintiffs, Shannon Smith, Marlece Turner, and Brenda Williams—parents of students who attended schools slated for closure, Empower DC, a grassroots organization, and members of the Advisory Neighborhood Commission filed an injunction to halt and dismiss the plans to consolidate permanently and close schools. While Shannon Smith is listed as the primary plaintiff in this case, parents received immense support from Empower DC, whose directors were present during depositions. Empower DC is an organization that provides training, development, community education, and advocacy for low-and moderate-income Washington, D.C. residents (www.empowerdc.org).

The schools slated for permanent closure were deemed under-enrolled, and Henderson asserted that closing these under-enrolled schools would save DCPS an estimated $8.5 million (Smith v. Henderson, Citation2013). However, while Henderson and other DCPS officials viewed these school closures as financially prudent, the plaintiffs, community organizers, parents, and students found that:

All of the schools to be closed sat in majority-minority, lower-income neighborhoods east of Rock Creek Park, in Wards 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8. Some of these schools had been drained of their students by the increasing popularity in charter schools. For example, around 50% of children attend charter schools in Wards 1, 5, and 7, and about 40% attend charters in Wards 4, 6, 8. Henderson’s proposal suggested no school closings in Ward 3, which is more White, more affluent, and west of the Park, or in Ward 1, which also contains several whiter, wealthier neighborhoods (Smith v. Henderson, Citation2013).

In this case, there is no evidence whatsoever of any intent to discriminate on the part of Defendants, who are transferring children out of weaker, more segregated, and under-enrolled schools. The remedy Plaintiff’s seek—i.e. to remain in such schools—seems curious, given that these are the conditions most people typically endeavor to escape. In any event, as Plaintiffs have no likelihood of ultimate success on the merits of their suit, they cannot prevail in this Motion here (Smith v. Henderson, Citation2013).

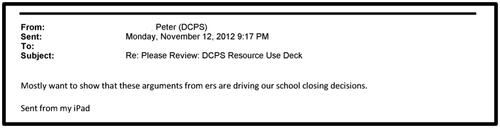

Data

Over the several months in which Smith et al. v. Henderson et al. (2013, 2014) took place, February of 2011 to October of 2014, a series of documents were produced for discovery; specifically, depositions and subpoenaed emails from DCPS administrators holding a DCPS.gov email address. For this study, I focused on publicly available sets of documents—the depositions of three DCPS administrators (e.g. chancellor, deputy chancellor of operations, and chief of data and strategy), and the emails subpoenaed from DCPS to substantiate plaintiffs’ claims of discrimination. Additionally, to triangulate my deposition and subpoenaed email data, I reviewed court memorandums of opinion, the DCPS reorganization plan, and other data, including media from local news outlets and blogs. Also, data presented in this study was acquired from a more extensive qualitative study (McMillian, Citation2018) on discursive violence. I present portions of the actual emails instead of rewriting the content of the emails; emails are displayed in reverse chronological order. For ease of reading, I numbered the email threads in the order they were received. I present unmodified images of the emails as a way of preserving the integrity of the data, making an invisible discourse tangible, and as a way of proving the existence of pretexts that led to discursive violence. Images of emails and passages from depositions were selected from 19, 347 pages of documents. To understand the power dynamics of the networking social systems, the job titles of the sender and receiver of emails are indicated on the emails. provides detailed information on the data analyzed in a larger study.

Table 1. Data produced during court discovery.

Winnowing the data

Content analysis is a methodology that allows an investigator to “select, appraise, and synthesize data contained in documents” (Bowen, Citation2009, p. 28). Following Bowen (Citation2009), my goal was to employ content analysis, not as a methodology but as a means of winnowing the depositions and subpoenaed emails listed in and reducing the amount of text analyzed by sampling particular documents (Weber, Citation1990). Open reading and memoing were conducted on the depositions of the DCPS officials—allowing the creation of a log of words and statements. An open-reading approach allowed me to gain more insights, without a presumption of prevarication, into the local context of Washington, D.C., DCPS, its fiscal need, and the concerns of the communities. During the open reading of the depositions, annotations or memos were created, text highlighted, and a log of phrases, names, neighborhoods, organizations, administrators, events, and schools was generated and functioned as a repository for items to query in the Nvivo11® software. Examples of log entries across all depositions were: IFF study, closure, consolidation, recommendation, Office of Civil Rights, Department of Education, Ward 8, ANC, Walton Foundation, and Broad Foundation. All pages of the depositions and subpoenaed emails were uploaded into Nvivo11®, and text queries were run on all items listed in the log. Conducting a key-word-in-context (KWIC) query (Weber, Citation1990) using Nvivo11® software, emails were reviewed to confirm the semantic and syntax use of the terms listed within the log. This approach yielded 106 pages of email threads available for coding and analysis alongside the three depositions—totaling 696 pages.

Analysis

Applying discursive violence to the DCPS school closure context

Passages redacted from the depositions and emails were framed within McMillian’s (Citation2018) adapted discursive model (as depicted in ) of Fairclough (Citation2010) that positions text, discursive practice, and social practice as unique but interfacing determinants in the reinforcement of inequity. The depiction of Fairclough’s three-dimensional framework for examining the interdependence of text, discursive practice, and social practice reflects a way of operationalizing violence and “three complementary ways of reading a complex social event” (Fairclough, Citation2010, p. 94). The secondary layer, discursive practice, in Fairclough’s model influences the potential of both text and social practice. In my model, the discursive practice layer is discursive violence working as a generator that exports violence into socio-cultural practices. Thus, discursive violence creates a gap between the potential and the actual (Galtung, Citation1969); understanding this fact is key to understanding this model. In this way, I applied dimensions of CDA to the passages redacted from the emails and deposition transcripts. Nodes that emerged from the analysis are depicted and categorized according to each construct of discursive violence in .

Table 2. Nodes coded across each construct and data.

I compared passages from depositions and emails to contextualize discourse and discursiveness as a means of understanding the duality of discourse with parents and community members versus other DCPS administrators and the mayor’s office. The duality of the public and private discourse revealed how, when, and which conditions employed discursive violence during the DCPS school closures. To make these comparisons, I layered a passage from a deposition (text) with text from a related email (discursive violence) and with the socio-cultural precepts of Fairclough (social practice). Because discursive violence exists in the discrepancy between the dispositions and the emails, the layered comparisons allowed me to examine the intersection of discourse and social power. By contextualizing and aggregating salient data, I illustrated how school closure policies and discursive practices that steer them met the criteria for each construct of violence (i.e. legitimization and normalization).

Findings

As defined previously, discursive violence is produced through behaviors, decisions, and other discursive practices and forms a continuum of socio-cultural practices adversely influencing a specific populace’s social, economic, political, and educational outcomes. When asking how discursive practices that steer school closures present as discursive violence, the data yielded evidence suggesting DCPS administrators often deployed discursive violence through practices of duality, framing a narrative for the court and public, and circumventing moral and ethical evaluation. Lastly, when asking how discursive violence can be used to understand school closures in a predominately African-American and urban school district, the data yielded evidence suggesting that discursive violence targets students of color and materializes in an urban context in exclusionary and spatialized manners. I present each theme in the following sections and accompany it with selected data from a larger dataset of findings from a previous study (McMillian, Citation2018).

Legitimizing discursive violence

Discreet in nature, discursive violence involves day-to-day interactions and practices that collectively define and influence cultural and institutional behavioral norms. Legitimization operates as a socio-cultural practice localized within a praxis of political and regulatory networks. Furthermore, the discursive level of social practice (as presented in ) harbors discursive violence and permits and performs systemic patterns of adversity. In legitimizing discursive violence, practices are mediatory; they balance, negotiate, and rationalize daily thoughts and actions. In subsequent sections, I present findings and evidence as examples of legitimizing discursive violence—duality, framing a narrative for the court and public, and circumventing ethical and moral evaluation.

Duality

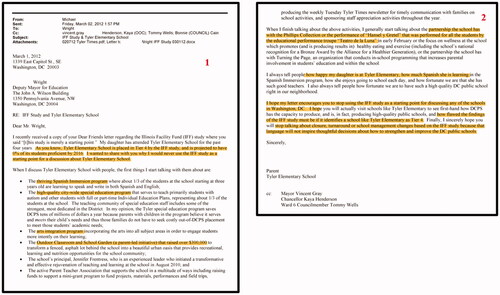

In Smith et al. v. Henderson et al. (Citation2013, 2014), DCPS administrators created a dual discourse, framed a narrative for the court and public, and circumvented ethical and moral evaluation. Identifying divergent public-private discourse is critical to operationalizing discursive violence. A comparison of depositions and subpoenaed emails revealed inconsistencies between DCPS’ public and private discourses. When confronted with inconsistent narratives, DCPS officials used rationalizations to justify the duality. Upon analysis, their publicly proffered rationales were contrary to the private discourses found among email exchanges. They represented a dissonant relationship between public and private behaviors—the type of dissonance where we negotiate between good and evil, or justice and injustice, and attempt to justify desired outcomes. DCPS administrators used duality, framed a specific narrative for the court and public, and circumvention of ethical and moral evaluation to present their decision as legitimate arguments for school closures and to reinforce the arguments with contrived evidence, all in support of their desired agenda. See Excerpt 1 as an example:

Excerpt 1

DCPS Chief of Data and Strategy: When did the process begin? So I think it is useful to think back that we have, there have been a number of factors that have changed DC and DC Public Schools over the past years, maybe even decades, including the increase in enrollment in charter schools, changes in population shifts in where folks live so we, DCPS, have recognized for years that based on the number of school buildings we had in 2012, that our number of buildings and our square footage exceeded the need that we had for the numbers of students we had enrolled. And in fact, our square footage in our number of buildings created inefficiencies in our schools that meant that we were paying a lot of money to keep buildings going that could have been better used to ensure that children are receiving a high quality education. So I don’t think there was any one particular aha moment when we recognized that we had a need to further reduce the overall footprint of the school district. I think that was clear for a long stretch of time. The, I think the issue gained additional attention in the spring of 2012. The deputy mayor did a study to look at the number of quality seats. And while it wasn’t, strictly speaking, a school consolidation analysis, it did speak to the number of good seats we had for students across the district. And we, as we looked at budget modeling, also identified that while we were spending a large per pupil sum at many schools, that we weren’t actually providing the quality of service that we wanted to be able to provide, because we lacked an economy of scale in those schools. And so that information, taken together over time, helped us recognize in the summer and then fall of 2012 that we should explore school consolidation as a means of improving the way we use our resources (Weber Dep. 29–31, February 11, 2014).

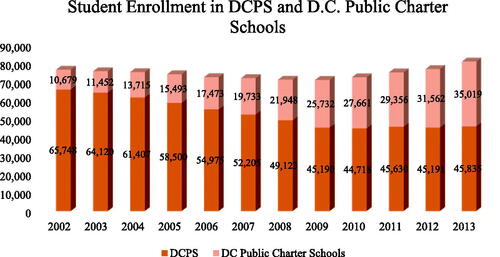

This excerpt is representative of the rationalizations put forward by the DCPS school officials. They described school closures as a necessary evil to remain economically stable—a necessary evil seemingly brought about by circumstances beyond their control (i.e. situations that seemed to happen to the school district). In their discourse, the school officials did not acknowledge that their actions were primarily responsible for the impending closures (i.e. situations they made happen). In Excerpt 1, the chief of data and strategy first based his rationale for the school closures on the local context of Washington, D.C. He pointed to economic and social changes as the primary reason for the 2013 school closures, inferring that DCPS’ decision operated in tandem with changing demographics and economies in D.C.’s various neighborhoods. He made the school closures seem inevitable rather than an outgrowth of DCPS’ past decisions to close schools. His first example of the “many factors that have changed DC and DC Public Schools” was the increased enrollment in public charter schools. In the deposition, the chief of data and strategy did not specify why charter school enrollment increased. However, found within the subpoenaed emails were enrollment data for both DCPS and D.C. Public Charter Schools; the data pointed to DCPS’ 2008 school closures, under the tenure of Michelle Rhee, as the cause for increasing enrollment in charter schools and corresponding declines in traditional-school enrollment. An email attachment detailed the student enrollment trends in both school systems. The email attachment is (re)produced in .

Because the Washington, D.C., Public Charter School System also services D.C. students, the data, once disaggregated, showed the decline in enrollment was merely a shift in enrollment from traditional to charter public schools. In other words, the chief of data and strategy maintained a duality in his discourse, choosing to omit what he knew to be true when speaking publicly. In the deposition, he did not admit to DCPS’ complicity in causing the district’s under-enrollment problem.

In Excerpt 1, the DCPS chief of data and strategy continued to rationalize school closure by transitioning from student enrollment concerns to the financial drain caused by the concomitant “under-enrolled” buildings. He stated, “We, DCPS, have recognized for years that based on the number of school buildings we had in 2012, that our number of buildings and our square footage exceeded the need that we had for the numbers of students enrolled.” He neglected to mention that the 2008 school closings, under the tenure of Michelle Rhee, were a significant factor in the dwindling enrollment and idle buildings. The DCPS school closures of 2008 reduced the space DCPS actively used for its students by 2.3 million square feet (21st Century School Fund, Urban Institute, & Brookings Institution, Citation2009). District administrators believed the closures of 2008 would bring financial reprieve because the reduced building-space requirements would also reduce the district’s fixed costs; however, the buildings remained in DCPS’ inventory, and any associated costs remained the responsibility of DCPS, creating a fiscal burden that DCPS was seeking to unload in 2013.

In addition to omitting any criterion that would help to define “a high-quality education,” the chief of data and strategy doubled down on his rationale for school closings by citing “a study that looked at the number of quality seats,” referring to the networked authority of both the IFF and ERS studies. The Chicago-based Illinois Facility Fund (IFF) is an organization that provides loans, New Market Tax Credits, equity, consultant services, and research to nonprofit organizations (www.iff.org). Education Resource Strategies (ERS) is a nonprofit organization that assists urban school systems in organizing resources, people, time, technology, and money (www.ersstrategies.org). Sponsored by the Walton Foundation, both IFF and ERS were commissioned by the Washington, D.C. Mayor’s office to research the quality of education in both DCPS and D.C. Charter Public Schools. While DCPS administrators mentioned charter schools as an alternative, charter schools were servicing students already displaced by the 2008 school closings. In turn, DCPS was hemorrhaging dollars. Instead of ending the financial losses, the government and other entities found creative ways to entice parents, students, and other educators to support school closures, convincing them that having “choice” would create healthy competition and that children should receive a quality education regardless of the means. This circular referencing affirms how discursive violence is legitimized systemically. In citing the IFF and ERS studies and other external reasons for the school closures, the chief’s deposition illustrates how networking social systems create a praxis of inequitable education opportunities.

Framing A Narrative for The Court and Public

When the mayor commissioned IFF and ERS to conduct research, he publicly framed it as research on all schools’ overall quality and effectiveness within D.C., including DCPS. The studies were framed to identify “quality” throughout the area; therefore, the judge’s perception was that school closures were necessary to provide quality education. For example, in a court memorandum quoted earlier, the judge stated the schools slated for closure offered “conditions most people typically endeavor to escape” (Smith et al. v. Henderson et al., 2013, p. 1). The subsequent figures reflect the misdirection of the studies and how DCPS used the studies to frame a specific narrative for the court and public.

Excerpt 2

Mr. Barnes: Now, that stream of e-mails also referred to the IFF study. It’s in there.

DCPS Deputy Chancellor of Operations: Yes, one of the e-mails on the chains refers to the IFF study. It looks like the agenda for the meeting that this was about.

Mr. Barnes: Yeah. You’re familiar with the IFF study?

DCPS Deputy Chancellor of Operations: I am.

Mr. Barnes: And how was the IFF study used in the context of the school closings?

Mr. Parsons: I’d object as vague.

Mr. Barnes: Was it?

Mr. Parsons: I assume we mean the school closings at issue in this case, not the 2008 closings?

Mr. Barnes: That’s correct.

Mr. Parsons: You can answer.

DCPS Deputy Chancellor of Operations: It wasn’t used by the work group. The IFF study was actually commissioned out of the deputy mayor for education’s office. It wasn’t a school closing study. It was where are quality seats in the city located? But it was not directly a criteria [sic], a factor or input in to the consolidation that we’ve been talking about this morning (Ruda Dep. 68–69, February 14, 2014).

Excerpt 3

Mr. Barnes: You’re familiar with the IFF study?

DCPS Chancellor: Yes.

Mr. Barnes: Uh-huh. Who funded the IFF study, if you know?

DCPS Chancellor: The DC Public Education Fund, I think.

Mr. Barnes: Uh-huh.

DCPS Official: Yeah.

Mr. Barnes: Was that study consulted in the school closings decisions?

DCPS Chancellor: No.

Mr. Barnes: And your testimony with respect to the ERS study was that it, too, was not consulted in the school closings?

DCPS Chancellor: The ERS study helped us understand, gave us information that informed the process. But previously you asked whether ERS had recommended schools for closure, and they had not (Henderson Dep. 106, February 21, 2014).

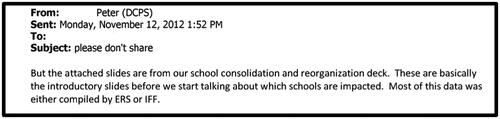

along with Excerpts 2 and 3 represent the duality of the narrative and how DCPS sought to frame a specific narrative to support their school closures decision. Moreover, they display how venture philanthropists and other networking social systems’ interests operate seamlessly away from public scrutiny and accountability and articulate in public education. The narrative for D.C. residents explained that the school closures were motivated by the needs of the district. However, private discourse ( and 7) revealed that school closures were motivated by the IFF study—a study representing the interests of the mayor’s office. The private discourse (emails) of the DCPS officials disclose actual socio-cultural discursive approaches and mischaracterizations of school closures. Private discourse is innate within any organization. Indeed, it is a necessary ingredient in the deliberative process that leads to decisions. However, discursive practices can potentially become untethered from ethical consideration when the narrative framed in private diverges from the narrative framed for the public. Divergent public-private discursive practices are especially harmful, and violent in public institutions such as school districts, as they shape students' educational experience.

Figure 5. Email exchange between concerned parent and administrators regarding the misleading of the IFF Study.

Figure 6. Confidential email from the DCPS Chief of Data and Strategy regarding data compilation by ERS and IFF.

The discursive practices of power-wielding officials have the potential to obfuscate the truth and become violent when they block access to meaningful participation in the decision-making process. Although private discourses alone are not grounds for disciplinary actions, discursive social practices that systemically disenfranchise certain groups in favor of others must be challenged and held accountable. When examining the content of the concerned parent’s email displayed in , alongside the emails and excerpts, prevarication about the use of the studies is evident. The use of the studies implicated the historical narrative of educational inequities constructed by agencies of capitalism and anti-Black racism in DCPS. The perversion of the reports’ results and the governance of associated discourse created and exacerbated inequitable outcomes for the African-American students impacted by these closures.

Circumventing moral and ethical evaluation

Each discursive level maintains its definition; they are also interconnected through the practices of discursive violence and have no exact point of delineation. Discursive violence is diverse in its articulations but singular in its essence—speaking to the indivisibility of the multiple exports of violence. Fairclough (Citation2003) framed rationalization as a component of legitimization and theorized that social power exists, in part, as a result of “the simultaneous working” of multiple discourses (p. 100). Found within the practices of discursive violence are processes of hegemony or social power that circumvent moral and ethical evaluation (Fairclough, Citation2003, p. 108).

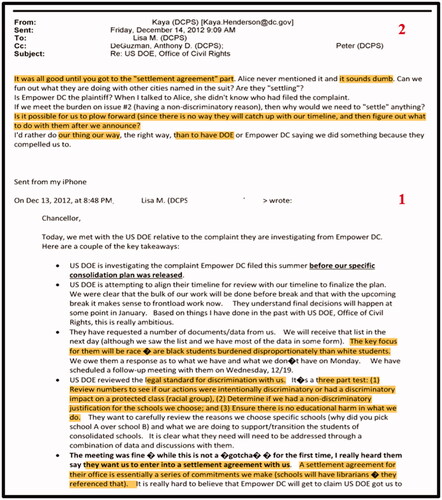

The presentation of data in are emails that show the efforts of DCPS administrators to circumvent moral and ethical evaluation assumed within their positions. As shown in , the DPCS deputy chancellor of operations provided the DCPS chancellor with essential action items from her meeting with constituents from the United States Department of Education’s (DOE) Office of Civil Rights (OCR). The office is a DOE sub-agency responsible for ensuring equal access to education through the enforcement of civil rights laws. In the email, with the subject heading “US DOE, Office of Civil Rights,” the deputy chancellor outlined the various recommendations and expectations of DOE but emphasized a resolution agreement. A resolution agreement with the OCR is a document that defines requisite action items a school district must address to be compliant with civil rights laws. This agreement would not have constituted an admission of guilt had DCPS chosen to sign it; rather, it would have documented an agreement between the two parties and an earnest attempt by DCPS administrators to resolve the Plaintiff’s complaint. However, the DCPS chancellor rejected the idea of a resolution agreement outright—dismissing and circumventing moral and ethical evaluation in so doing. Shown in is an email exchange from the DCPS Deputy Chancellor of Operations to the DCPS Chancellor informing the Chancellor of key takeaways from a meeting with the DOE, OCR.

Figure 8. Email exchange from the DCPS Deputy Chancellor of operations to the DCPS chancellor regarding the recommendations of the United States Department of Education.

The way discursive practices legitimize discursive violence is through the processes of production (Fairclough, Citation2003). This production is inextricably connected with how we develop a product. In this instance, an answer to how discursive practices that steer school closures present discursive violence entwines how DCPS administrators intentionally attempted to circumvent the evaluation of their policies. In the email displayed in , the deputy chancellor of operations was intentional in her feedback to the chancellor about a resolution agreement with OCR. In her reply, the chancellor is adamant about not adhering to the recommendations of the OCR. The DOE’s Office of Civil Rights exists because the United States has a history of discrimination in its public education. Therefore, the willingness to subvert the OCR on the part of the chancellor was tantamount to a willingness to subvert equity.

The chancellor went on to call the OCR recommendation “dumb.” In addition to dismissing the possibility of a student experiencing discrimination within her school district, the chancellor’s response trivialized federal efforts to achieve educational equity. This response showed an uncanny amount of comfortability with refusing and then insulting the recommendations of the OCR. The chancellor’s inquiry about other school districts’ cooperation with the OCR demonstrated her willingness to cooperate solely based on the popularity of the resolution agreement. Tactfully, the deputy chancellor of operations informed the chancellor that the timeline the OCR was pursuing was “ambitious,” inferring that the DOE’s investigative timeline could be unattainable by the time DCPS announced the final list of schools to be closed. The chancellor’s language in her response included phrases like “plowing forward,” “there is no way they will catch up with our timeline,” “figure out what to do with them after we announce,” and “I’d rather do our thing our way … than to have DOE or Empower DC saying we did something because they compelled us to.” This language reproduced social domination because it was an abuse of her authority.

Moreover, the chancellor’s refusal to cooperate, use of insulting and conditional language, and willingness to expedite the school closures to avoid investigation—without legal repercussion—were all examples of how practices of discursive violence are legitimized. Additionally, the courts affirmed these discursive violence practices because these emails—that went unevaluated—were a part of the discovery presented to the court. Duality of the discourses, framing a narrative for the court and public, and the blatant disregard for systems of accountability added to the legitimization of discursive violence.

Normalizing discursive violence

In the normalization of discursive violence, practices of discursive violence have social implications. For example, the normalization of discursive violence in Smith et al. v. Henderson et al. resulted in subjugating and patterned lived experiences exclusive to the African-American students. In addition, findings suggest that DCPS administrators employed practices of discursive violence that were exclusionary and geographical toward Washington, D.C. residents who lived east of Rock Creek Park.

Exclusionary practices

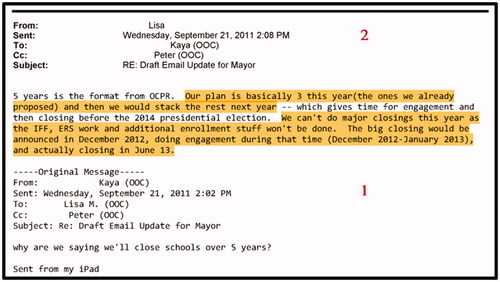

In an effort to avoid repeated protests and political backlash from Michelle Rhee’s 2008 DCPS closures of 23 schools, DCPS administrators made commitments to the public that there would be transparency and collaborative community engagement throughout the process of deciding on the 2012–2014 closures. Presented below are data from an email and passage from the depositions that show DCPS administrators did engage D.C. community members; however, the DCPS administrators did so on their terms. Fourteen months before the initial release of the DCPS Consolidation and Reorganization Plan (DCPS, 2013), DCPS officials had a predetermined timeline that is explicitly outlined in . Shown in is an email exchange between the DCPS Chief of Data and Strategy and the DCPS Chancellor.

Figure 9. Email exchange from the DCPS Chief of Data and Strategy and the DCPS Chancellor clarifying the school closure timeline.

Presented in is DCPS administrators’ preferred timeline of the school closures and consolidations. Written 14 months before the November 2012 release of the closure/consolidation plan, this email exchange identifies how the results of the IFF and ERS studies would be used. The email described an aggressive five-year plan of consolidating and closing several public schools in Washington, D.C. The deputy chancellor of operations allowed a timeframe of two months for “engagement.” However, DCPS administrators did not specify who their audience would be during the engagement period, and this intentional ambiguity created a discursive standard that any form of engagement would suffice. Consequently, DCPS administrators established a precedent for selective engagement. illustrates that DCPS was willing to delay the school closure timeline for the sake of the IFF and ERS studies but not for the students and communities impacted by the school closures. This disparity is an example of how DCPS' administrators' practice of discursive violence was exclusionary and limited the parents, community members, and students from meaningful input into conversations and an opportunity to provide community-based solutions.

Furthermore, the deputy chancellor of operation’s synopsis of the five-year school closure timeline excluded the semantic use of “community” and neglected to anticipate any protests or engagement from the African-American communities affected by the closures. Instead, phrases such as “stack the rest” and “closing before the 2014 presidential election” were used as discursive signifiers that prevented meaningful collaboration with the community and the contributions and perspectives of parents, students, teachers, and community members. Moreover, the semantic positioning of engagement omitted any references to the community or parents, suggesting the DCPS administrators had assumed the proposed timeline presented in would face no obstacles that would alter their plans to close schools. Twice, the term engagement appeared within the deputy chancellor’s email; however, both mentions are absent of a description. The term engagement is positioned as a routine task or a marketing ploy, not as a shared decision with those affected by the school closures.

The excerpts below were taken from the deposition of the DCPS Chancellor. Because the chancellor and the mayor had responsibility for the final decision when determining which schools would remain open and which would close, counsel for the plaintiffs, Mr. Barnes, asked why the chancellor chose to close some schools and not others. Counsel for the plaintiffs asked the chancellor specifically about the community engagement period. Barnes named each school located in Wards east of Rock Creek Park and asked the DCPS Chancellor if she met directly with parents from each school he names.

Excerpt 4

Mr. Barnes: Okay. Was the mayor involved in crafting that initial list?

DCPS Chancellor: I am sure that I took the initial list to him before we released it publicly. He probably gave us feedback on that initial list before we went out. And then we went out publicly after getting his input.

Mr. Barnes: Okay. Garrison was on that initial list?

DCPS Chancellor: Yes.

Mr. Barnes: Did you meet with parents from Garrison?

DCPS Chancellor: Yes.

Mr. Barnes: Uh-huh. Francis-Stevens was on that initial list?

DCPS Chancellor: Yes.

Mr. Barnes: Did you meet with parents from Francis-Stevens?

DCPS Chancellor: Yes.

Mr. Barnes: Ferebee-Hope was on that initial list?

DCPS Chancellor: Yes.

Mr. Barnes: Did you meet with parents from Ferebee-Hope?

DCPS Chancellor: In the large community meeting, but not specifically with parents (Henderson Dep. 62–63, February 21, 2014)

Excerpt 5

Mr. Barnes: Thank you. Sharpe Health School parents?

DCPS Chancellor: Not in a specific meeting about Sharpe Health …

Mr. Barnes: Ron Brown Middle School?

DCPS Chancellor: No.

Mr. Barnes: Kenilworth?

DCPS Chancellor: No.

Mr. Barnes: Any school in Ward 7 or 8?

DCPS Chancellor: I don’t know. I’m happy to go back and look in my calendar and we can tell you exactly who I met with about what over that course of time.

Mr. Barnes: Martha Winston in Ward 7?

Mr. Rosenbloom: Again, this is whether there was a meeting with the parents?

Mr. Barnes: With parents and the chancellor.

DCPS Chancellor: No.

Mr. Barnes: Mamie D. Lee?

DCPS Chancellor: Nope. (Henderson Dep. 65–66, February 21, 2014)

Following along the lines of community engagement, counsel for the plaintiffs was attempting to demonstrate how the community engagement period was scripted and never intended to leverage the concerns of the parents, students, teachers, and community in a meaningful way that would persuade the DCPS Chancellor to alter the school district’s plans. Instead, the engagement period seemed to be about optics, exploiting the students and communities. Data from the depositions and emails did not show deliberate engagement with communities east of Rock Creek Park. Yet, in the earlier marketing of the mayor’s One City Plan (D.C. Exec. Off. of the Mayor, 2012) and the IFF and ERS studies, the public language surrounding school closures inferred the community would be central stakeholders in the final decision. The inconsistency or the lying about community engagement caused surreptitious acts and illustrated a disregard for the concerns and interests of the communities, thereby normalizing discursive violence.

Geography and race

When Judge Boasberg ruled that the plaintiffs’ motion for an injunction against the school closures was denied, in his memorandum of opinion, he aligned his opinion with the narrative that had been framed for him using subjective truths. He wrote:

The remedy Plaintiffs seek—i.e. to remain in such schools—seems curious, given that these are the conditions most people typically endeavor to escape …. To promote its proposal and gather community feedback, DCPS took its show on the road. The City Council held two hearings on the closures. DCPS itself convened meetings throughout the city, including four Ward-based public meetings that drew 780 participants…this desire for community input was no charade. On the contrary, the feedback yielded real changes in DCPS’ final Plan (Smith et al. v. Henderson et al., 2013, Section 94).

The initial DCPS consolidation and reorganization plan was released in November 2012. This plan proposed the closing and consolidation of 20 public schools across the nine D.C. wards, with many of the closures situated east of Rock Creek Park. In January 2013, two months after the initial plan, DCPS administrators released a revised proposal that reduced the initial list of 20 schools to 15 public schools (DCPS, 2013). Those 15 schools sat east of the dividing racial lines of Rock Creek Park and served a total of 2,792 students. Of them, 2,790 students were students of color and predominately African-American; two students were White. Therefore, 99.92% of the students the DCPS displaced with 2013–2014 school closures were students of color. However, when asked explicitly about the racial demographics of students impacted by the school closures, DCPS officials stated that race was not a factor when deciding which schools would remain open and which schools would close.

Excerpt 6

DCPS Chief of Data & Strategy: I did not know the precise number of students who were impacted by consolidation.

Mr. Barnes: Had you known, would that have made a difference in your thinking?

Mr. Rosenbloom: Again, calls for speculation.

Mr. Barnes: No. He knows what he thinks.

Mr. Rosenbloom: Repeat the same objection. You can answer if…

DCPS Chief of Data and Strategy: Okay. Had I known…I’m sorry. Would you mind restating the question?

Mr. Barnes: Had you known that of the 2,792 students affected by the closures, 2,790 were students of color, mostly African-American, would that have influenced your thinking?

Mr. Rosenbloom: I’m repeating the objection. Go ahead and answer.

Mr. Barnes: Sure.

DCPS Chief of Data and Strategy: No, I don’t believe it would.

Mr. Barnes: Uh-huh. And had you known that only two White students were impacted would that have influenced your thinking?

Mr. Rosenbloom: I would repeat the objection.

Mr. Barnes: Understood.

DCPS Chief of Data and Strategy: No, sir.

Mr. Barnes: Were those numbers ever discussed in those meetings?

DCPS Chief of Data and Strategy: I was never in a discussion of the specific number of students affected by school consolidation, that I can recall (Weber Dep. 86–87, February 11, 2014) ().

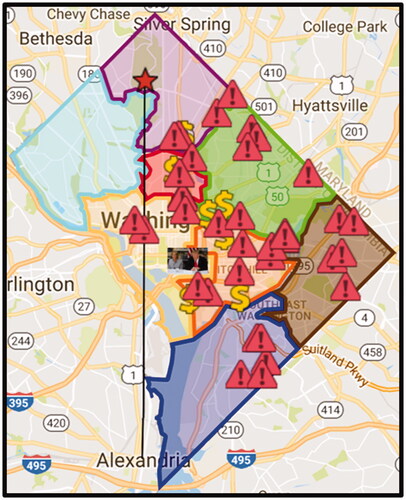

Figure 10. Map of Washington, D.C. Wards. Note. Map of Washington, D.C., wards, with an overlay of all locations of the 2008 and 2013 school closures. Yellow dollar symbols represent the areas of gentrification.

The intersection of race and geography in the Smith et al. v. Henderson et al. case (2013, 2014) established a framework of inequity for D.C. wards east of Rock Creek Park. In this instance, normalized practices of discursive violence against African-American students and their communities had geographic implications, and areas of quality education were drawn on a map along lines similar to the boundaries that would define racial divides. In Excerpt 6, the chief of data and strategy dismisses race as a factor influencing DCPS school closures. However, the students and communities affected by the closures were disproportionately African-American; therefore, race cannot be ignored when assessing which communities were harmed. Race and geography are not mutually exclusive in this instance, but rather interlocking demographics used to reinforce White norms and localize discursive violence against African-American students and their communities. At the expense of student’s education, access, and opportunity, DCPS administrators purposefully evaded conversations about the racial implications of the school closures. Because these school closures occurred in concentrated African-American neighborhoods, the geographical dimensions of these closures were also racialized. Therefore, avoiding and objecting to discourse regarding the demographic impact and the geographical location of these school closures creates an adverse educational experience for a specific race of students. However altruistic DCPS administrator’s intentions were to preclude race; this form of discursive blindness or race neutrality of policy cultivates racism and duality of discourse. In this instance, a consideration that the students overwhelmingly affected were African-American would have, at the very least, compelled both public and private discourses to address the racialized implications of the closures. DCPS administrator’s colorblind approach did not diminish the disparate impact of the closures but instead amplified the adverse effect of the closures. Furthermore, their discursive blindness impeded their ability to interrogate how the pretexts of capitalism and racism influenced their personal and work-related decisions.

Conclusion

Dumas and colleagues’ (Dumas et al., Citation2016) posited that educational equity is complicated by discursive practices” (p. 6). Equivocally, violence against minoritized communities is found within discursive practices. Discursive violence is a byproduct of Anti-Black racism. Discursive violence is produced through behaviors, decisions, and other discursive practices that form a continuum of socio-cultural practices adversely influencing a specific populace's social, economic, political, and educational outcomes. Discursive violence impedes the process of narrowing the distance between present reality and potential reality (Galtung, Citation1969)—inequity versus equity. The promise of equity and the improvement of public education for African-American students are often quenched by practices of discursive violence. These practices of discursive violence persist through relics of systemic anti-Black racism, are legitimized by networking social systems, and are normalized by administrators who kowtow to inequitable ideologues (Khalifa, Citation2015). Because practices of discursive violence are determined by a social hierarchy (Bonilla-Silva, Citation1997), they also inform social interactions, and achieving change would mean reforming the social condition (Freeman, Citation1977). As previously mentioned, discursive violence is an anthropological inquiry (Shore & Wright, Citation2003) into policy, how policies govern schooling, and how discursive shifts occur during policy implementation. Thus, discursive violence is a valuable framework that centers on how policy impacts students' educational experiences. Using CDA to operationalize discursive violence within qualitative data contributes to the education research literature because it provides insight into how inequities persist within urban public education; they [inequities] are reified in daily discursive practices that are micro in essence, nuanced, and easily bypassed—moreover, operationalizing discursive violence through CDA plots how education reform policy is implemented within urban contexts. Discursive violence is critical for examining education reform policy, such as school closures, because it foregrounds discourses that are otherwise hidden. Additionally, because adverse social, political, economic, geographical, and educational pretexts make it difficult for public schools to function as “sites of opportunity” (Horsford et al., Citation2019, p. 1), the application of the discursive violence framework contextualizes the miscarriages of education reform implementation within these pretexts.

In Smith v. Henderson, the novel use of case discovery as data presents itself as an interdisciplinary opportunity for qualitative inquiry. Using discovery as data bridges law and education, and advances existing knowledge on how the courts view the implementation of education reform policy and school district governance. Under the guise of “quality education,” the Washington, D.C., mayor and DCPS school administrators forged partnerships with venture philanthropists and framed their partnerships as an opportunity to remedy a problem that they had constructed. These partnerships disparately and negatively impacted African-American students, other students of color, students from low-income homes, and students with disabilities. Discursive practices surrounding school consolidation and closure policies are violent. This discursive form of violence is substantiated through school reform policies and is maintained through day-to-day interactions. Because of the normalcy of violence, we have relegated violence within our schools to physical notions, overlooking the violent discursive practices that widen the gap between educational inequity and achieving educational equity. CDA recognizes that inquiry into discursive practices is always an exploration into power (Rogers, Citation2011). Practices of discursive violence are power in motion. The foremost example of power in motion is how state and local education agencies respond administratively to education reform policies. Because words, written or spoken, have creative power (J. Hall, personal communication, January 3, 2016), policies have an innate ability to construct lived experiences. With this, it becomes beneficial for education researchers to contend with discursive violence as the culprit of persistent educational inequities, identify the practices of discursive violence that operate within various educational phenomena, as well as what practices or discourses are needed to usurp the discursive violence often employed to implement federal, state, and local education reform policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rhodesia McMillian

Rhodesia McMillian is an Assistant Professor of Education Policy at The Ohio State University College of Education and Human Ecology. Utilizing critical methodologies and theories, Dr. McMillian is an interdisciplinary scholar whose research bridges K-12 education reform law, education policy, elementary and secondary educational governance, special education law, and sociology.

References

- Aggarwal, U., Mayorga, E., & Nevel, D. (2012). Slow violence and neoliberal education reform: Reflections on a school closure. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 18(2), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028099

- Au, W. (2009). Obama, where art thou? Hoping for change in US education policy. Harvard Educational Review, 79(2), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.2.2qp374u658v11770

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (1997). Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review, 62(3), 465. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657316

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Brick, B. T. (2009). Race, social context, and social control: An examination of disparity in school discipline [Ph.D.]. University of Missouri - Saint Louis.

- Buchanan, J. (2008). Using Foucaldian critical discourse analysis as a methodology in marketing. Australia and New Zealand Marketing Academy.

- Cartledge, G., Tillman, L. C., & Talbert Johnson, C. (2001). Professional ethics within the context of student discipline and diversity. Teacher Education and Special Education, 24(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/088840640102400105

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8, 1. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v8n1.2000

- Desimone, L. M., & Long, D. A. (2010). Teacher effects and the achievement gap: Do teacher and teaching quality influence the achievement gap between Black and White and high-and low-SES students in the early grades. Teachers College Record, 112(12), 3024–3073. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811011201206

- Dumas, M. J., Dixson, A. D., & Mayorga, E. (2016). Educational policy and the cultural politics of race: Introduction to the special issue. Educational Policy, 30(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904815616488

- Eco, U. (1986). Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language (vol. 398). Indiana University Press.

- EdBuild (2019). 23 Billion. http://edbuild.org/content/23-billion

- Epp, J. R. , & Watkinson, A. M. (Eds.). (1997). Systemic violence in education: Promise broken. SUNY Press.

- Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and text: Linguistic and intertextual analysis within discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 3(2), 193–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926592003002004

- Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. Routledge.

- Fairclough, N. (2010). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Routledge.

- Fairclough, N., Jessop, B., & Sayer, A. (2002). Critical realism and semiosis. Alethia, 5(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1558/aleth.v5i1.2.

- Fanon, F. (1963). The wretched of the earth. Grove Press.

- Ford, D. Y., & Russo, C. J. (2016). Historical and legal overview of special education overrepresentation: Access and equity denied. Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners, 16(1), 50–57.

- Ford, D. Y., Harris, J. J., Tyson, C. A., & Trotman, M. F. (2001). Beyond deficit thinking: Providing access for gifted African American students. Roeper Review, 24(2), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783190209554129

- Freeman, A. D. (1977). Legitimizing racial discrimination through antidiscrimination law: A critical review of Supreme Court doctrine. Minn. L. Rev, 62, 1049.

- Fullard, Q. (2013). Ignoring successful practices: A case study of Michelle Rhee and William Bratton. Chicago Policy Review. Online.

- Garcia-Villegas, M. (2003). Symbolic power without symbolic violence. Florida Law Review, 55, 157.

- Garner, B. A., & Black, H. C. (2014). Black's Law Dictionary. Thomson Reuters.

- Glennon, T. (1995). Race, education, and the construction of a disabled class. Wisconsin Law Review, 1995, 1338.

- Habermas, J., & Viertel, J. (1975). Theory and practice. Studies in Soviet Thought, 15(4), 341–351.

- Hall, S. (1997). Foucault: Power, knowledge, and discourse. In Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices 72–81. London: Sage.

- Haskins, R., & Loeb, S. (2007). A plan to improve the quality of teaching. Education Digest, 73(1), 51–56.

- Heise, M. (2006). Litigated learning, law’s limits, and urban school reform challenges. NCL Review, 85, 1419.

- Horsford, S. D. (2011). Learning in a burning house: Educational inequality, ideology, and (dis)integration. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Horsford, S. D., Stovall, D., Hopson, R., & D’Amico, D. (2019). School leadership in the New Jim Crow: Reclaiming justice, resisting reform. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 18(2), 177–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2019.1611872

- Jackson, K. W. (1982). Factors that influence the achievement difference between Black and White public school students [Ph.D.]. The University of Chicago.

- Jencks, C., & Phillips, M. (1998). The Black-White test score gap: Why it persists and what can be done. The Brookings Review, 16(2), 24–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/20080778

- Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336900600301

- Journey For Justice Alliance. (2014). Death by a thousand cuts: Racism, school closures, and public school sabotage. http://www.j4jalliance.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/J4JReport-final_05_12_14.pdf

- Keisch, D. M., & Scott, T. (2015). US education reform and the maintenance of White supremacy through structural violence. Landscapes of Violence, 3(3), 6.

- Khalifa, M. (2015). Can Blacks be racists? Black-on-Black principal abuse in an urban school setting. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(2), 259–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.916002

- Klein, D. W. (2002). Beyond Brown v. Board of Education: The need to remedy the achievement gap. Journal of Law & Education, 31(4), 431–457.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2001). Crossing over to Canaan: The journey of new teachers in diverse classrooms. The Jossey-Bass Education Series. Jossey-Bass, Inc.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2006). From the achievement gap to the education debt: Understanding achievement in U.S. schools. Educational Researcher, 35(7), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X035007003

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The Dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children. John Wiley & Sons.

- Leonardo, Z., & Porter, R. K. (2010). Pedagogy of fear: Toward a Fanonian theory of "safety" in race dialogue. Race Ethnicity and Education, 13(2), 139–157. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2010.482898

- Levin, H. M. (2006). On the relationship between poverty and curriculum. NCL Review, 85, 1381.

- Lipman, P., & Haines, N. (2007). From accountability to privatization and African American exclusion: Chicago’s “Renaissance 2010”. Educational Policy, 21(3), 471–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904806297734

- Lomotey, K. (1990). Going to school: The African-American experience. SUNY Press.

- Maingueneau, D., & O'regan, J. P. (2006). Is discourse analysis critical? And this risky order of discourse. Critical Discourse Studies, 3(2), 229–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405900600908145.

- Mawhinney, L., Irby, D. J., & Roberts, E. S. (2016). Passed along: Black women reflect on the long-term effects of social promotion and retentions in schools. International Journal of Education Reform, 25(2), 154.

- McMillian, R. (2018). Rationalizing violence: Examining discourse and school closures in Washington, D.C., public schools [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Missouri-Columbia; MOspace Institutional Repository.

- Mendez, L. M. R., & Knoff, H. M. (2003). Who gets suspended from school and why: A demographic analysis of schools and disciplinary infractions in a large school district. Education & Treatment of Children, 26(1), 30.

- Ravitch, D. (2001). Left back: A century of battles over school reform. Simon and Schuster.

- Rebell, M. A. (2006). Poverty meaningful educational opportunity, and the necessary role of the courts. NCL Review, 85, 1467.

- Renzulli, L. A., & Evans, L. (2005). School choice, charter schools, and White flight. Social Problems, 52(3), 398–418. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2005.52.3.398

- Rhee, M. (2012). What it takes to fix our schools: Lessons learned in Washington, DC. Harvard Law & Policy Review, 6, 39.

- Rogers, R. (2011). An introduction to critical discourse analysis in education. Routledge.

- Rothstein, R. (2004). Wishing up on the Black-White achievement gap. Education Digest, 70(4), 27–36.

- Russo, C. J., & Talbert-Johnson, C. (1997). The overrepresentation of African American children in special education: The resegregation of educational programming? Education and Urban Society, 29(2), 136–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124597029002002

- Saltman, K. J. (2015). Venture Philanthropy and the neoliberal assault on public education. Neoliberalism, Education, and Terrorism, 67–93. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315633299-3

- Saucedo, D. R. (1992). Ethnicity as basis for inclusion or exclusion in programs for the mildly handicapped [Ed.D.]. University of California, Riverside.

- Shore, C., & Wright, S. (Eds.) (2003). Anthropology of policy: Perspectives on governance and power. Routledge.

- Smith v. Henderson, 944 F. Supp. 2d 89 (Dist. Court (2013).

- Smith, P. J. (1999). Failing to mentor Sapphire: The actionability of blocking Black women from intiating mentoring relationships. UCLA Women’s Law Journal, 10, 373.

- So, A. Y. (1992). The Black schools. Journal of Black Studies, 22(4), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/002193479202200405

- Thompson, P. W. (2014). African American parent involvement in special education: Perceptions, practice, and placement [Ed.D.]. University of California, San Diego.

- Wald, J., & Losen, D. (2003). Defining and redirecting a school-to-prison pipeline, school-to-prison research conference. Harvard University.

- Watkins, W. (2015). The assault on public education: Confronting the politics of corporate school reform. Teachers College Press.

- Watson, T. N. (2018). Zero tolerance school discipline policies and Black girls: The (un) intended consequences. Journal of the Center for Policy Analysis and Research, 1(1), 167–187.

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis. SAGE.

- Wiener, R. (2006). Opportunity gaps: The injustice underneath achievement gaps in our public schools. NCL Review, 85, 1315.

- Willig, C. (2015). Discourse analysis. In J. A. Smith, Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 143–167). SAGE.

- Wing, J. Y. (2002). An uneven playing field: Behind the racial disparities in student achievement at an integrated urban high school [Ph.D.]. University of California, Berkeley.

- Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2015). Methods of critical discourse studies. SAGE.

- 21st Century School Fund, Urban Institute, & Brookings Institution. (2009). Analysis of the impact of DCPS school closings for SY 2008–2009 (p. 21). http://www.21csf.org/csf-home/publications/MemoImpactSchoolClosingsMarch2009.pdf