Abstract

Effective social research tapping a broad range of human experiences must employ research paradigms that are consistent with the ontologies and epistemologies of the research participants, community, and contextual scholars. This paper describes the construction of a bricolage, imbricating Islamic and interpretivist concepts for coherence and rigor in engaging 35 Muslim–Canadian educators in interviews on their pedagogies. The act of centering an Islamic paradigm made data visible beyond a narrow secular Western frame, offering analytic precision and interpretive significance within Muslim educational communities. Illustrating this data–paradigm engagement, a collective data excerpt is presented on socio–spiritual development, whereby educators described establishing with young Muslims an overarching conceptual framework rooted in Islamic tradition to situate self, social, and spiritual relationships; embark holistic transformative actions with social, individual, and spiritual dimensions; and engage in continuous self-reflexivity triangulated with divinity (muhasaba). Offering a unique pedagogical approach to socio–spiritual development, this bricolage also challenged methodological singularity.

1. Introduction

In embarking upon empirical fieldwork inquiring into educators’ pedagogies, what does a researcher do with statements like: “We are going to study math for the sake of Allah,” or “The report card comes after our death,” or descriptions of working with learners towards “having at least some degree of unmediated relationship with the Divine”? These words were voiced by Amira, a mosque-school principal; Rasha, an elementary school principal; and Faris, a youth educator, respectively, in semi-structured interviews during a critical interpretive study examining the pedagogies described by 35 Muslim–Canadian educators in a large Canadian city, in engaging young learners in teaching and learning Islam.Footnote1 This paper explores the relationship between a research paradigm and the data it yields—in this case, highly esoteric data—whereby consistency across research design involves matching epistemology, methodology, and methods to both deeper ontological priorities and research objectives (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Carter & Little, Citation2007; Zine, Citation2008). The paper details the process of assembling a study design as a bricolage, with Islamic paradigmatic concepts as primary and interpretivist methodological concepts as secondary, which conjoined diverse and, at times, disparate perspectives. This design proved expansive in capturing data beyond corporeal sense perception, beyond what is ordinarily visible within a normative, secular, Western research paradigm, which is illustrated in a collective data excerpt providing a glimpse of the research story. The study’s paradigmatic framing makes visible the data excerpt, which simultaneously reflects the paradigm.

In the next section, I situate myself as the researcher, provide some information on the original study upon which this paper reports, and establish the paper’s rationale. Section 2 examines some previous literature upon which this paper builds. Section 3 describes constructing a paradigm of Islamic concepts to frame the empirical research with Muslim–Canadian educators on their pedagogies. Section 4 offers a data excerpt collectively generated via the educators’ descriptions of pedagogies in nurturing social relationships. Section 5 discusses implications of employing a paradigm based on Islamic concepts for educational research in a Muslim community and offers some concluding thoughts.

1.1. Author–researcher positioning

As a Muslim interpretive bricoleur, ongoing critical reflexivity is required in situating myself within my work, academic discourses, and hegemonic and liberatory social structures that frame my life towards making visible—and hopefully empirically useful—my location in relation to my research. I am a white, English-speaking, Canadian woman of European descent, situated within socio-economic-educational privilege. The practices of formal Western schooling have contributed significantly to my development and manifest themselves in many ways in this research: the concepts I use, the pedagogies I value, the issues I see in schools and societies, the research questions I ask, and the meanings I make. As Kamberelis et al. (Citation2017) described, “researchers are (and should acknowledge) that they have been constructed within particular academic discourses that constitute filters through which they see and act in the world” (p. 703). In addition, I embraced Islam as a whole-life practice two decades ago and learned many key principles and practices living for several years in the Hijaz region of Saudi Arabia, home to the cities of Mecca and Medina. From this vantage point, I came to see deeply expanded dimensions of existence, sources of knowledge, and faculties of the human being that inform the way I live in the world and how I view the processes of research and knowledge attainment. As such, my research design bears epistemic traces of secular Western and Islamic spiritual cultural worlds that I inhabit simultaneously. Bricolage, as a relational, processual, culturally-relevant, and creative research design suitable for complex contemporary contexts (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2018), reflects my own complexities as well as those of my 34 research participants, who referred to 17 different “back home” cultures in making sense of Islamic pedagogy in Canada (see Alkouatli, Citation2022).

1.2. The original study: illuminating transcendent pedagogies

The study upon which this paper reports was designed around a simple, exploratory research question: By what pedagogies do Canadian–Muslim educators engage learners in teaching and learning Islam? The question aimed to identify day-to-day practices that Muslim educators enacted within a larger, overarching educational philosophy rooted in the Islamic tradition (eg. Memon, Citation2021). Some initial sensitizing concepts revealed a current gap in literature of Islamic Education Studies.Footnote2 First, there may exist pedagogies unique to teaching and learning Islam not yet categorized within this literature. Second, Muslim educators may be engaging learners in practices whose pedagogic value has not been fully appraised in light of Islamic educational objectives or current understandings of learning and development. Third, there may even be pedagogical engagements in evocations of transcendence, as perceptions of the Divine beyond the reach of corporeal sense perceptions. If an aim of Islamic education is to know the Divine—an aim articulated by a teacher in this study, called Fatima, as helping young Muslims “see Allah in everything around them; from within and outside”—then there must exist pedagogies that move learners towards this aim. If such transcendent pedagogies existed, arguably, they would be oriented towards the aim of Islamic education as deepening of knowledge over the lifespan and self-development in becoming “fully human in this world and to achieve everlasting happiness in the next world” (Chittick, Citation2011, p. 86). To become fully human is to develop spiritual faculties along with those of cognition, emotion, and physicality.

Where I had expected from the outset that the study’s focus would generate descriptions of transcendent content material, surprisingly, this study generated descriptions of transcendent pedagogies. Little research has previously examined transcendent pedagogies by which Muslim educators engage young people in exploring transcendence, as that which is beyond corporeal sense perception and centered around the concept of the Divine/God/Allah. There are some references to “transcendence” in the mainstream educational literature, albit few related to pedagogies. Phenix (Citation1971) offered a description of transcencence as the experience of going beyond any given state and the realization of being. Transcendence relates to creativity and the attitudes of wonder, awe, and reverence, which, in turn, constitute the impulse to learn: “Instead of regarding human learning primarily as a means of biological adaptation, it may be thought of as a response to the lure of transcendence” (p. 278). Transcendence may be cultivated by living in “the strength and illumination of it” along with witnessing “those who consciously celebrate it in their own existence” (p. 283). Descriptions in Islamic tradition highlight the primordial and transcendent nature of human beings as the fitra, characterized not only by purity and goodness but also by innate consciousness of God (Asad, Citation1980), with the soul (ruh) being the connection point to consciousness of God (Rothman & Coyle, Citation2018). In this perspective, the contextual, dynamic, and transcendental characteristics of the human self, which is created with potentials and capacities for agency and subjectivity, color a lifelong transformational process (Sahin, Citation2013). Unique aspects of this process include the role of self-transcendence within purposeful accountability:

[H]humans are endowed with both the competence for self-transcendence, a meta-cognitive function to monitor one’s life, and the gift for self-relativisation, an ethical quality that enables humans to be aware of their limitations through their recognition of the need to remain open, responsible and accountable to one another and, ultimately, to their Creator. (Sahin, Citation2013, p. 93)

Cultivating purposeful self-transcendence is central to education and scholars in Islamic tradition describe the ways in which our human faculties relate to transcendence as an educational process, including by seeing the Divine names, attributes, and signs in creation and within the human self (eg. Rothman & Coyle, Citation2018; Rothman, Citation2021).

In this study, the educators spoke in detailed terms about pedagogies of transcendence, highlighting pedagogical functioning at the esoteric core of an Islamic worldview. Here, educators and learners—independently, as pedagogical dyads, and collectively—interface with the Divine/God/Allah, beyond the reach of corporeal sense perception (the ghayb) (see Alkouatli, Citation2022). Importantly, these transcendent pedagogies are only made visible and meaningful within a paradigm expansive enough to recognize them in the first place. The purpose of this paper is to understand this paradigm–data dynamic and, as such, the question guiding this paper is: How does a research paradigm rooted in an Islamic conceptual framework make visible transcendent pedagogies?

1.3. Rationale: a paradigm problem

Transcendent pedagogies are important in learning and development based upon expanded understandings of the human being and in service of the esoteric aims of Islamic education. These pedagogies are intrinsically important in Muslim educational communities and, in addition, may contribute to educational diversity in secular Western multicultural communities, home to many Muslim learners and educators. Yet, such transcendent pedagogies are significantly understudied and, in trying to understand their absence in the literature, the dominance of so-called “international” education, rooted in a secular neoliberal paradigm with its radix in the Western academe, may play a role. Eurocentric research paradigms, including interpretivism, embedded with “white racial ideologies”—which were developed in the context of coloniality, “during periods of devastating racial oppression” (Pascale, 2011, p. 21)—are insufficient for inquiring into the full range of human experience. They are not expansive enough to capture data beyond their ideologically-fortified boundaries. In the context of Islamic education, specifically, these research paradigms need to be expanded because transcendent pedagogies are only visible when situated within paradigms that are broader at the levels of ontology and epistemology. In other words, empirical identification of transcendent pedagogies, here expressed in the Muslim educators’ words as data, require a research paradigm expansive enough to see and make sense of them in the first place. Pascale (2011) emphasized that research paradigms offer researchers more than “simple orientations for data collection and analysis […] they provide frameworks for recognizing what we see, as well as for understanding the relevance and importance of what we see” (p. 25; italics added). In addition, as a way of assessing the quality of qualitative research, Carter & Little (Citation2007) detailed a framework of internal consistency across epistemology, as the study and justification of knowledge; methodology, as the process of inquiry and justification for the research design; and method as research action in the form of techniques for gathering data and conducting analysis, which together create knowledge (p. 1317).Footnote3 In this study, Islami-basedc knowledge, defined as “knowledge that is based on an Islamic paradigm and emerges from Islamic epistemology and Islamic methodology” (Al Zeera, Citation2001, p. xxi), formed a starting point and an intended outcome.

A research paradigm constitutive of Islamic concepts of ontology, epistemology, methodology, and methods was required for generating new knowledge on transcendent pedagogies. Yet such frameworks have rarely been used as analytic tools in studying Muslim sites of education, schools, and societies. “Instead, they have long been regarded as elements of “false consciousness” or as dogmas to be suppressed by ‘rational’ scholarly thought” (Zine, Citation2008, p. 58). This suppression poses a significant problem for educational researchers in Muslim learning communities, in terms of recognizing and making sense of data beyond the limited scope of a normative secular paradigm. Zine’s (Citation2008) critical faith-centred framework was a unique attempt within the literature on Islamic Education to “situate spiritually centred epistemologies as valid locations for the production of academic knowledge” (p. 58). Therefore, it was the starting point of the study upon which this paper methodologically reports.

2. Research paradigms in the literature

Previous Muslim educational researchers have grappled with the question of how to conceptually situate research that involves knowledge production with and relevant to people in Muslim communities and, simultaneously, must also be taken seriously in the Western, secular-dominant academy. Many sidestep the issue and adopt exclusively positivist or interpretivist paradigms. Others strive to build conceptual bridges between paradigms. Some have called for situating research in Islamic contexts first and foremost within Islamic conceptual paradigms (Al Zeera, Citation2001; Al-Faruqi, Citation1988; Zine, Citation2008), starting with recognition that an overarching worldview informs the very foundations of Islamic education (Memon & Alhashmi, Citation2018; Mogra, Citation2010). Approaching Islamic ontology and epistemology from an educational rather than theological perspective, three scholars of Islamic Education—Al Zeera (Citation2001), Zine (Citation2008), and Ahmed (Citation2014)—upon whose work I built this study, positioned their work in different but related ways within Islamic paradigms.

Al Zeera (Citation2001) pointed out that large numbers of Muslim students and scholars at universities in Europe and North America use methods of inquiry derived from Eurocentric scholarship (positivist or constructivist) and queried whether these students were aware of how paradigms derived from Muslim worldviews relate to the methods and assumptions guiding their research. She described researchers who identified as Muslims, including herself: “Our daily activities are colored with Islamic values, so learning, making meaning, and interpreting new situations are all done in an Islamic frame of reference” (p. 46). While this may seem obvious, Al Zeera argued that not all existing secular, social-science paradigms are appropriate for producing holistic knowledge for the development of Muslim individuals and societies:

[A] practicing Muslim might blindly produce highly valid and scholarly research on cloning or genetic engineering which might cause a great deal of harm to humanity; […] Scientifically it would be sound research, but religiously and morally it might be dangerous and improper. (p. 26)

Zine (Citation2008) also addressed the paradigm challenge directly. When embarking upon ethnographic research in Islamic schools in Canada, Zine recognized that there existed no single analytic framework capable of attending to the various religious, social, political, cultural, and gender issues requiring examination in her research site; that integrated “spiritually-centered ways of knowing as part of legitimate academic knowledge” (p. 50). Instead, spiritual knowledges were subjugated knowledges, delegitimized by secular knowledge masquerading as a universal standard, even though secular knowledge is merely one path amongst many towards knowledge. Zine (Citation2008) asserted: “The dominance and perceived universality of this perspective silences other understandings—spiritual, metaphysical, and cosmological” (p. 50). In lacking engagement with spiritual knowledge, existing epistemological frameworks were unable to center issues of importance to the research participants themselves. In response, Zine (Citation2008) constructed the critical faith-centered epistemological framework to create space for faith-centered perspectives as valid sources of knowledge. Zine’s framework functions as a bridge between paradigmatic perspectives, upon which other scholars can travel, which allows for nuanced and contextually relevant interpretation and analysis in sites of Islamic education. In my study, Zine’s (Citation2008) framework formed the foundations of an integrated paradigmatic research design, which I then elaborated with ontological, epistemological, and pedagogical perspectives drawn from broader literature on Islamic education and Islamic Studies scholars whose work on education fills a gap in the literature, including Nasr (Citation2012); Rahman (Citation1980, Citation1988) and Winter (Citation2016).

Ahmed (Citation2014) articulated the importance of researchers’ “rooting thinking processes in Islamic epistemology” (p. 566). She pointed out the “fundamental divide between holistic Islamic epistemology and its principle of an eternal core truth on one hand and the inherent relativism/subjectivism of interpretivism on the other” (p. 567) and situated her research in an interpretive paradigm while aiming to retain the “the holism of Islamic epistemology” through the Islamic research principles she devised to guide her research. Ahmed (Citation2014) described how a non-Muslim reader might take her work as purely interpretivist, but a Muslim reader might judge her work on how true it stayed to an Islamic paradigm as embodied in those research principles. She elaborated:

Had this study used a purely interpretivist paradigm, it may have produced useful findings from a social research perspective, but these findings would be a world away from what the community that is initiating the research would find useful or meaningful. (p. 567–568)

3. Methodology: paradigmatic architecture in constructing the bricolage

In assembling Islamic concepts into a paradigm to frame this research, I started with three principles drawn from of Zine’s (Citation2008) critical faith-centered epistemological framework, which was designed upon guiding precepts drawn from the Qur’an governing theory and praxis and broadly echoed across the literature on Islamic Education and the lived reality of many Muslim people. The central ontological concept of tawhid, indicating sole unique divinity as the source of all existence, comprises the first principle from which all else flows: “A philosophy of holism, or connections among the physical, intellectual, and spiritual aspects of identity and identification” (p. 53). Within this ontological holism, which transcends our limited understandings of time, space, and human ontogenesis, the spiritual and material, cognitive and emotional, ideological and practical all contribute to a wholeness of being that Islamic practices aim to develop. The second principle is epistemological:

Not all knowledge is socially constructed, but knowledge can emanate from divine revelation and can have a spiritual or incorporeal origin. Beliefs in prophets, revelation, messengers, angels, spirits, jinn, and so on must be incorporated into research and knowledge production as part of the way faith-centred people read and make sense of the world and their place in it. (p. 68)

That a spiritual essence is embedded in everyday acts is central to maintaining the articulation of the spiritual, material, and intellectual states of being as holistic and mutually constituting elements of Islamic ontology. From an epistemological standpoint, this forms the basis of understanding of how faith-centred Muslims make sense of the world and their place in it. (pp. 53-54)

The conceptual priority of an Islamic onto-epistemological paradigm is illustrated in the core conception of the human being, as an embodied being composed of an interconnected mind/intellect (‘aql), heart (qalb), and soul (ruh), which enables wider dimensions of consciousness (Rothman, Citation2021). First, the detailed mapping of these faculties in Islamic traditional literature center the spiritual aspects of the human being. The intellect (‘aql) has been described by classical scholars as “a sirr rūḥānī (spiritual enigma) by which the soul can perceive knowledge via both self-evidentiary and demonstrative means, with its place in the heart, and its light in the mind” (Mosaad, Citation2022, p. 111). With the heart and mind both of a spiritual substance, much of their functioning takes place beyond the tangible and material; in the ghayb, which is translated as “that which is beyond the reach of human perception” (Asad, Citation1980, p. 25) and cannot be conveyed to human beings “in other than allegorical terms” (p. 111). My study required a paradigm able to recognize pedagogies intended to engage these faculties.

Following from this first point, where a secular paradigm may be considered primarily a product (and tool) of cognition, an paradigm rooted in Islamic principles is characterized as a product (and tool) of an expansive expression of consciousness, as unified and embodied cognition, emotion, and spirituality (Al Zeera, Citation2001; Boyle, Citation2006; Rothman & Coyle, Citation2018).Footnote4 This consciousness is central to an Islamic paradigmatic perspective, its development is a primary objective of both human development and education in Islam, and pedagogies may play a role in that development.Footnote5 The onto–epistemic–pedagogic holism of an paradigm drawing from Islamic tradition renders it primary in this research design, within which methodology and methods are situated, and which echoes Al-Faruqi’s (Citation1988) call for research to “embody the principles of Islam in its methodology, in its strategy, in what it regards as its data, its problems, its objectives, and its aspirations” (p. 16–17). In responding to such calls, a conceptually-prior paradigm centering key Islamic principles at the core of the research enabled deeper, clearer vision of educators’ objectives and uses of pedagogy and, simultaneously, actively contested the marginalization of Islamic education at the levels of paradigm and pedagogy. The study’s dimensions all collectively echoed the imperative primacy of an Islamic conceptual paradigm: the research topic (Muslim educators pedagogies in teaching Islam), the academic field in which it was situated (Islamic Education Studies); and the researcher and research participants’ social, religious, and epistemic locations in Muslim life.

3.1. Interpretivist methodology

After establishing an paradigm rooted in Islamic principles as conceptually primary, interpretivism provided an analytic framework for interpreting evidence (Pascale, 2011). While interpretivism is often identified as a research paradigm, in this study interpretivism was relegated to the level of methodology—and, even then, imbricated with Islamic research principles (Ahmed, Citation2014)—primarily because interpretivism is not conceptually broad enough to encompass the full range of human experience in Muslim educational contexts.

The socially-situated starting point of an interpretivist approach to research is that people interpret themselves and their circumstances in ways shaped by culture and characterized by unique ontological perspectives, which, in turn, shape their practices, institutions, and cultural contributions (Hammersley, Citation2013). For example, there would be little point educating a child Islamically if a teacher did not conceive of that child as embodying a pure nature (fitrah), a spiritual dimension or soul (ruh); if a teacher did not recognize transcendent objectives behind ritual practices and their existential trajectories. Pascale (2011) described: “In order to understand a situation, interpretivists argue that researchers must understand the meanings the situation holds for the participants, not just their behaviors” (p. 23). Authentic interpretivism alone renders imperative an Islamic conceptual paradigm as the starting point of this study and its perspectival frame.

Simultaneously, such a paradigm in interpretational context may provide space for (a) a participant to articulate meaning and (b) a researcher to interpret meaning, both of which are needed in producing valid knowledge, as Pascale (2011) pointed out:

Evidence is always the political effect of decisions regarding what constitutes valid and relevant knowledge as well as decisions that regard the conditions a researcher must fulfill to give her or his work value as science. Consequently, critical empirical research must begin not with a theory/evidence dichotomy but rather with a theory/evidence convergence that recognizes the theoretical foundations that shape what constitutes valid knowledge. (p. 27)

The process of discerning Islamic principles framing a paradigm in the first instance is itself an interpretive act, as is discerning dimensions for “internal consistency” between epistemology, methodology, and methods (Carter & Little, Citation2007, p. 1316). Building an internally-consistency research foundation is necessarily interpretive because it involves human researchers making research decisions relevant to a given researcher, in a context, with particular research participants, at a particular time. Therefore, along with being an interpretation itself, a paradigm rooted in Islamic principles is necessarily inclusive of differences in interpretation because it does not specify particulars in terms of what Islamic principles are but, rather, invites individual researchers to describe Islamic particulars relevant to their own interpretive traditions and research contexts in processes of designing internally-consistent, culturally-coherent research. The particulars a researcher employs to frame research will eventually justify the generation of new knowledge. As such, Islamic interpretive inclusivity may be made visible by methodological interpretivism.

In this study, interpretivism not only complimented a paradigm of Islamic principles in framing research conducted in an Islamic site of education, it rendered such a paradigm imperative in that the unit of analysis of this study—educators’ perceptions of pedagogy—“have been shaped by the deeper faith values” (Sahin, Citation2017, p. 131). This study’s paradigm made visible those faith values and interpretivism made visible their import.

3.2. Bricolage

Framing this study within a larger Islamic conceptual paradigm aimed to balance the epistemic weight of its interpretivist methodology, developed in the global North, and constituted a bricolage as research design, whereby: “The researcher-as-bricoleur-theorist works between and within competing and overlapping perspectives and paradigms” (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2018, p. 12). The term “bricolage” acknowledges that the study is guided by a conceptual imbrication of both Islamic and interpretivist concepts, ethical imperatives, and methods, aiming to unify the emic and the etic, the marginalized and the dominant, the contextual and the abstract in a form of “border thinking” (Mignolo, Citation2011, p. 61). As a researcher shaped by diverse worldviews, bricolage is an expression of an inner dialectic. The goal is not to replace one paradigm with another but understand their limitations—including Islamic ones, which cannot be acritically accepted—as well as their possibilities. A Muslim researcher need not draw only from a faith-based perspective, nor from only one interpretational or sectarian perspective of Islam or way of being Muslim (Panjwani & Revell, Citation2018). Instead, the interplay of secular and faith-based frameworks as intellectual alliances may allow for greater depth of analysis than either one on their own (Zine, Citation2008).

Bricolage also captured methodological complexity as an expression of sociocultural complexity amongst the 35 Muslim–Canadian educators as research participants whose perspectives on pedagogy were multicolored interpretations shaped by diverse contexts. They were each members of larger educational communities comprised of children, parents, community leaders, international scholars, and religious leaders, teaching, learning, researching, and evolving at the intersection of multiple cultures. Sahin (Citation2018) reflected this point and asserted the need for more reflexive dialogue between diverse education ideas and expressions:

The life-world of young generations of Muslims has been informed by both Islamic parental heritage as well as the wider secular culture. How young Muslims develop their sense of belonging and agency within such a demanding cultural reality needs careful consideration by the community as well as wider society. (p. 12)

3.3. Methods of data collection and analysis

Fidelity to a bricolage of Islamic and interpretive principles, as dialectic integration at an ontic-epistemic level, extended to methods intended to make full, accurate meaning of the data. Three data-collection methods included, first, individual semi-structured interviews (Brinkmann, Citation2018); second, engagement of two to four educators at a time in halaqat, or dialogic circles of learning and communication (Ahmed, Citation2014, p. 20); and third, artifact-mediated halaqat, whereby I invited the teachers to visually represent their perspectives on methods of teaching Islam (an artifact).Footnote6

While understanding a research encounter as inherently joint meaning making may be common in interpretive research, the particularly esoteric (ghaybiat) dimensions of the conceptual substrate underlying these research encounters—Islamically-inspired perspectives of objectives, content, participants in teaching and learning, and pedagogy—made for discussions whereby we grappled to articulate these esoteric dimensions and generated insights that could only have been captured within a research paradigm allowing for such dimensional reach. As such, study’s bricolage approach as an may situate it at the borders of the post-qualitative, which Denzin & Lincoln (Citation2018) described as a horizon informed by “postcolonial, indigenous, transnational, global, and the multiple realities […]” (p. 3). Each aspect of this horizon was present in this study.

4. Visible data excerpt: a process of socio–spiritual development

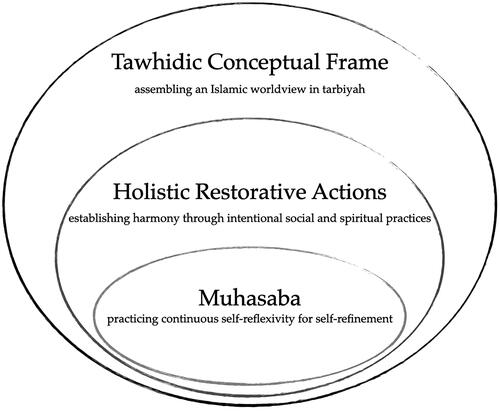

During data collection, many of the educators, at some point or another, discussed nurturing young people’s social development. Specifically, the educators described how they handled altercations between children—arguments, disagreements, fights, and even bullying—as part of socio–spiritual development aimed at nurturing the faculties of body, mind, heart, and soul in uniquely Islamic conceptions of being human. Although the educators were teaching in Canadian context, their descriptions diverged significantly from normative and progressive approaches to behavior education in mainstream Canadian schools and were clear manifestations of the broader Islamic paradigm in which they are situated. Here, these descriptions are presented as a collective data excerpt: the educators’ voices together compose a pedagogical picture of socio–spiritual development of character in three parts, illustrating how the individual, the social, and the Divine are enmeshed in integrative relationality. First, the educators’ described the everyday relational process of establishing with young people a comprehensive tawhidic conceptual framework—a worldview centering the Divine—in concentric hierarchical arrangements of social relationships characterized by rights and responsibilities. Second, educators described guiding youth through holistic transformative actions with social, individual, and spiritual dimensions—making things better with other people, with oneself, and with God, respectively—as rehearsals of verbal, physical, social, and spiritual practices. Third, educators described working with young people on developing a type of ongoing critical self-reflexivity (muhasaba), triangulated against the tawhidic conceptual framework towards self-refinement. Taken together and illustrated in , these three parts illuminate an iterative process of socio–spiritual development within which educators engaged learners and, in doing so, made visible an Islamic paradigm. Each aspect of the process is further described below.

4.1. Assembling a tawhidic conceptual framework for “great morality”

As a first step towards developing healthy social interactions, the educators described helping young people establish a conceptual framework characterized by tawhid as the centrality of divinity. As an overarching cognitive framing of their daily activities, the conceptual framework holds distinct perspectives on individual, social, and divine rights and responsibilities. At its most basic, it involves moral values, which the educators described as exploring together with children in an everyday process of tarbiyah. Ruby described reminding the learners of various hadith (or saying of the Prophet ﷺ), including: “The Muslim is the one from whose tongue and hand [other] Muslims are safe.” Asifa described consistently integrating this same hadith into the school day: “A good Muslim is the one who doesn’t hurt another Muslim with his tongue or his hand.” Gentleness and safety towards others are intrinsic aspects of Muslim moral character. Ruby described another hadith identifying a strong person as someone who can control his or her anger, not someone who can physically overpower others. Moreover, preventing oneself from becoming a bully is just as important as protecting oneself from being a victim of bullies, as Jina described while studying a particular Qur’anic verseFootnote7 with her learners:

We talked about the differences between humazah and lumazah—humaza is a bully and lumazah is a backbiter—and how these two people are dangerous! We should be careful not to be a humaza or a lumaza. And how can we protect ourselves from these people?

The educators described working with young people on developing khuluq, beautiful character enacted in behavior, modelling it themselves, and providing illustrations in the actions of Prophet Muhammad and his closest companions. Desire to be amongst the people closest to the Prophet—and closest to his character—is a unique objective of Islamic education that Fatima, an elementary educator, described working on daily: “Everything good that they [the children] do, we relate it to our Prophet Muhammad’s Sunnah, we relate it to Qur’an. We make them feel that [they are living Islam] when we are walking.” Fatima described coming across some birds while outside with the children and seized the chance to make meaning together:

Deen is filled with animals. This is Islam. Islam teaches us how to be merciful with animals. So, you want to let them know that this great morality, it is not with no base: this is Islam. We have to make the relation clear.

Rasha described khuluq as both an individual and a community developmental responsibility:

The basic thing that we talk to them [the learners] about bullying is Muslim brotherhood and sisterhood; that this is your community. The Prophet (ﷺ) said that the people closest to him on the Day of Judgment are the ones who are best in behavior.,Footnote8 Khuluq [moral character]. The best of you has the best khuluq. So that is basically the message we give them.

Abid, a youth educator, elaborated on this unseen dimension as he described exploring with young people how to be patient in the face of negativity or injustice: “Not to reply to the bad with the bad is another [higher] level of patience.” Abid illustrated this concept in a story about Muhammad and his companion Abu Bakr. The two of them were together when a man started swearing, slandering, and hurling insults at them. Muhammad just smiled without replying. After a while, Abu Bakr could take the insults no longer, and he replied some words to the man. When Abu Bakr replied, Muhammad left. Abu Bakr ran after him and inquired as to why he had left. Muhammad said:

When the man was slandering us, there was an angel present. And the angel was replying for us: whatever the man said went back to him. But when you replied, the angel left and Shaytan came. And I don’t want to be in a place where Shaytan is. That’s why I left.Footnote9

Moving from basic moral actions and safety, towards a more complex divine ontology, Amira identified transcendence in social-emotional life in saying: “[The Qur’an] is shifa al sudu [healing the hearts in our chests]. It’s shifa [healing] for everything. Allah is taking care of our emotions!” This description contains some uniquely Islamic conceptions, including identifying Allah, via the Qur’an, as the source healing and care for emotions. From this perspective, developing increased God-consciousness is itself a significant source of strength and resilience in facing life’s hardships. Abid and Amira’s words highlight the Divine center of this tawhidic conceptual framework, within the ghayb, beyond material perception, where Allah is a sole and central reality. Educators described helping children make sense of this transcendence using analogies. Huda said, “We are not seeing Allah directly, but we can see everything around us saying that there’s only one God. So, I try to connect them by the small things. We can’t see the air, for example, but we would die without it!” Her colleague, Fatima, elaborated: “You cannot see air, but it still exists; you cannot see your soul that makes you alive—you cannot see it, but you are alive! So, yes, there are things in our religion, we cannot see it, we cannot feel it, we cannot touch it—but it still exists.” These were ways in which the educators mediated divinity.

Amira described evoking the divine as knocking on the doorway into knowledge itself:

For us, it is the key to enter into any of the subjects whatsoever: Islamic Studies, Qur’an, and Arabic as well! It’s a kind of knocking on the door of knowledge, in a way [pause]. They don’t say to the kids, We are going to study math for the sake of Allah [whispering]—they don’t do it in secular settings. But we do it…

Taken together, these excerpts reveal some specific principles and practices, including transcendent ones, populating a tawhidic conceptual framework as a moral foundation of socio–spiritual development.

4.2. Holistic transformative actions: verbal, social, physical, spiritual

As action is essential to knowledge (Al-Attas, Citation1980), this second step involves activating social and spiritual knowledge specific to the tawhidic conceptual framework. When an altercation happens, the educators described supporting young people in engaging in concrete actions as immediate, practical, and situated sense making. Apologies come first, Asifa described, followed by: “Purify yourself, say, ‘Astaghfiruallah [may Allah forgive me]. Astaghfiruallah. Astaghfiruallah.’ Please say astaghfiruallah. Clean your mouth—not by rinsing or by gargling—but by saying ‘Astaghfiruallah’ and purifying yourself.” Thus, along with regular retributive actions—apologizing and making things better with the other child—Asifa taught young perpetrators to conduct verbal–spiritual actions to make things better with God and with him/herself. Jina emphasized, “It’s very important to feel this purification, to feel that you’re good with Allah.”

The next step is inviting the child to emotionally connect to the other child by empathically and imaginatively considering: “If they did that to you, how would you feel? Put yourself in those shoes!” Asifa said, and, finally, acting upon one’s remorse by trying not to do it again: “So, don’t say this to her or him again!”

Next, Ruby described teaching physical actions—“the Islamic techniques to calm ourselves down”—starting with the ritual cleansing practice of wudu. She reminded her learners: ‘Go make wudu and then come back and let’s discuss the issue.’” The physical act of splashing water on oneself is intended to put out the fire of anger. Then, when things are cool and calm, discussion can take place.

Amira described helping children move their emotions into physical actions with spiritual resonances: “We teach them, especially the one who perpetrated, to do two rakat [cycles of prayer] for forgiveness. So, we are connecting the feeling, even if it was negative, and transforming it into ibadah [act of worship]. Feelings into action.” In this excerpt, Amira described teaching children how to transform a negative action into an act of worship. This is an example of a transformative action as a pivot that reorients the child toward higher, transcendent awareness. Here, the teacher works with the nature of the child (fitra)—a nature that includes both making mistakes and recognizing divinity—to transform negative emotions into acts of worship. Asifa similarly described instructing her students to do these special prayers: “Salat al tawbah (prayer of repentance), right away: two rakat—go, go go go! […] You’re going to ask Allah for forgiveness. This was not right, what you did!” Here, the educators described supporting their learners to understand what they did and take transformative actions that worked upon individual spiritual levels, as well as social ones.

Taken together, Jina described that these holistic transformative actions—verbal, physical, and spiritual supplications and actions—may have lifetime consequences: “Asking children to do the astaghfar [supplication for forgiveness]—astaghfiruallah al Azim—and asking them to pray to two rakat, it goes with them for a lifetime.” In other words, these responses to social conflicts are transformative of character in the moment and over a lifetime. With practice, these actions become sources of personal refinement and empowerment for both the person transgressed and the transgressor.

4.3. Critical self-reflexivity: muhasaba

A third aspect of this Process of Socio–Spiritual Development is critical reflection, individually and together, upon what happened, triangulated by the tawhidic conceptual framework. After an incident, Rasha described: “The very first thing we ask them is: ‘What do you think your situation is with Allah (ï·») is right now? Is He happy with you? Is He sad?’ So, we always get them to reflect on their behavior in terms of halal and haram.” Here, along with reflecting on the impacts of one’s actions on other people, reflection is triangulated with a divine dimension, which has previously been noted as a type of critical but supported, metacognitive self-evaluation of oneself in light of a divine perspective and expectations (Alkouatli, Citation2022, Citation2020). Referred to as muhasaba, this triangulated critical self-reflexivity contains the potential to propel a person to their highest good. Indeed, that is its purpose. This third step in nurturing healthy social interactions, like the first two steps, evokes to the initial Islamic conceptual framework that educators constructed with learners, and which involves imagination and perspective taking. Educators asked learners to imagine other children’s feelings: “If they did that to you, how would you feel?” (Asifa); to imagine angels defending the innocent (Abid); to imagine God’s perspective, to which every person is ultimately accountable (Rasha). In short, to evaluate one’s actions beyond one’s own perspective.

This collection of excerpts illustrates transcendent pedagogies in contemporary cultural context across holistic human dimensions; as data beyond a normative, secular, tangible frame. Here, educators work with young people to understand the Islamic concepts that comprise an overarching tawhidic conceptual framework and are translated into holistic transformative practices and triangulated with critical self-reflexivity. In working to transcend lower impulses and extinguish the fire of anger and move towards higher impulses—making amends with other people, transforming mistakes into acts of worship, and engaging in ongoing self-reflexivity in light of divinity—these practices may have lasting effects on how young people deal with conflict in their lives. In turning low moments of tension into opportunities for self-refinement, young people actively deepen socio–spiritual interactions and develop the esoteric qualities of taqwa (God-consciousness) and khuluq (moral character). As an ongoing process of socio–spiritual development, Ruby described, “I always connect these Islamic techniques and principles to everything we face.”

5. Data–paradigm engagement (discussion)

The primary methodological problem that inspired the design of this study was the marginalization of Islamic frames of reference as relevant tools for research (Al Zeera, Citation2001; Zine, Citation2008), as part of a larger problem of epistemic hegemony (Alkouatli, Citation2020; Mignolo, Citation2011). Dominant discourses in the secular Western dominant academy emphasize the measurable, the tangible, which means, for the researcher as well as the 35 Muslim–Canadian educators at the center of this study, that the ghayb, beyond corporeal sense perception, poses an ongoing conceptual and existential problem. In response, I constructed an Islamic–interpretive bricolage to frame this study based on three onto-epistemic principles: first, tawhid is a philosophy of holism centering divinity and fostering connections among physical, intellectual, and spiritual; second, knowledge can have a spiritual or incorporeal origin; third, everyday practices link and enact the two (Zine, Citation2008). Together, these principles opened so much epistemic space that they made visible the most esoteric aspects of the study’s themes: human spiritual dimensions, divine relationality and knowledge, and pedagogies that develop all three. Most pedagogies in Islamic education support a specific interplay between the human and the transcendent, between al-insan and Allah. Without employing an paradigmatic frame that made them visible and intelligible, these aspects would have been rendered invisible in a data loss so significant that both the insan and Allah disappear, leaving only the tangible but most superficial, instrumental pedagogies behind, bereft of reason or intention: excursions into nature, critical thinking exercises, arts, and crafts.Footnote10 Ontological, epistemological, and methodological expansion into Islamic tradition was required to capture data celestially located beyond a narrower secular frame that is highly relevant to the educational community within which the research took place.

On this liberating epistemic ground, I embarked on the process of data–paradigm engagement, as a “dialogical interface between the data and the framework” (Zine, Citation2008, p. 48), whereby: “particular knowledge gained in the field is related back to the discursive frame” (p. 48). As related to their pedagogies, the educators described aspects of an Islamic paradigmatic framework. This engagement between the foundational principles and the now-visible data was illustrated in the excerpt of the previous section, whereby the educators invited young people to embark upon a socio–spiritual process of development, so named in recognition of the integrative relationality between an individual, other people, and the divine. This process fosters a unique, expansive growth mindset, where social interactions are triangulated by a divine reality, which can be evoked for forgiveness and purification at any time; angels help the oppressed; and the very real human tendencies for expressing negative emotions and making mistakes can be turned intentionally into acts of worship. Critical self-reflexivity on this process contributes to self- and social-refinement for self-development. There are two primary implications that involve consistency and agency.

5.1. Paradigmatic consistency is important in both research and educational design

While the collective excerpt illustrates the importance of a paradigm consistent across ontology, epistemology, and methodology as a valuable heuristic in research, such a paradigm is also helpful in framing the Islamic educational philosophy that guides Muslim educators’ praxis. Up to this point, I have employed the term ‘paradigm’ in the context of research and the term ‘conceptual framework’ in the context of education. But the two merge in establishing the foundations of Islamic educational research to support education in the Islamic tradition. Articulating the ontology, epistemology, and methodology/pedagogy of an Islamic educational paradigm makes visible unique objectives (the why), conceptions of learners and teachers (the who), content (the what), pedagogies (the instructional how), and perspectives on human development (the mechanistic how and when). From a singular ontological starting point that translates into sources of knowledge and sensemaking, this educational paradigm is expressed, in the social microcosm of a classroom, in practices: Islamic rituals and contemplation; social relationships; social etiquette; knowledge seeking; and pedagogies. Consistency across foundational paradigm is just as important to effective Islamic education as it is to rigorous empirical research. Yet, the holism of this consistency was damaged with the onset of colonial education and persists through the continuation of ‘international’ education. Key aspects have been deleted, denigrated, and overwritten, especially those located in the ghayb, beyond the reach of corporeal perception. This also constitutes a significant loss of educational potency in many of today’s Islamic schools, which are often based on secular Western models that conform to curricula, pedagogies, and standards based on very different paradigmatic foundations. Muslim educators, school leaders, parents, and scholars are currently grappling with the ramifications of this normalized damage and aiming to restructure Islamic schools starting with onto-epistemic paradigms relevant to their own communities (eg. Abdalla et al., Citation2018; Memon, Citation2021; Ahmed, Citation2021). If the optimal education of Muslim children is built upon an Islamic worldview, this paper offers insights as to how Islamic educators and schools might restructure their approaches to socio-spiritual development as daily relational processes that replace ‘behavior management’ when things go wrong.

5.2. Socio–spiritual development is agentic

Divinity as central to a tawhidic conceptual is only made relevant by an individual’s agentic recognition of this divinity and acknowledgment through active engagement. Al-Attas (Citation1980) illuminated this process in the term adab, as unified knowledge of one’s position within such a frame and concomitant action:

Adab is recognition and acknowledgement of the reality that knowledge and being are ordered hierarchically according to their various grades and degrees of rank, and of one’s proper place in relation to that reality and to one’s physical, intellectual and spiritual capacities and potentials. (p. 17).

In relation to human relationships it is about adhering to ethical norms in social behaviour. It manifests as respect, humility, and love for one’s parents, families, communities, neighbours, teachers, and so on. In relation to the natural world, proper place is about maintaining and cultivating the natural environment and being conscious of personal actions and choices that can harm nature. Similarly, intellectually and spiritually, proper place is defined by recognizing one’s ultimate purpose and essence. (p. 76)

In summary, provide a working example of data–paradigm engagement, expressed in two implications: 1. an Islamic research paradigm across ontology, epistemology, and methodology translates into an Islamic educational paradigm, with unique pedagogical expressions towards developmental aims; 2. Individual young people have agentic roles to play in their own socio-spiritual development, which appear as pedagogical expressions collaborative between educators and learners.

Table 1. Data–paradigm engagement illuminating a socio–spiritual process for development.

5.3. Concluding thoughts

Three principles derived from a critical faith-centered epistemological framework (Zine, Citation2008) constituted the starting point of this research, elaborated by paradigmatic aspects drawn from the Islamic Education literature, enhanced by interpretivist methodology, and operationalized by culturally-relevant methods into a critical interpretive bricolage rooted in Islamic concepts. This basic internal consistency translated into a research paradigm for framing empirical research with Muslim–Canadian educators. As evoking vision of reality that affirms no dichotomy between the sacred and the profane, between the worldly (dunya) and the other-worldly (akhirah) (Al-Attas, Citation2005), the research paradigm enabled a “metaphysical survey of the visible as well as the invisible worlds” (p. 13). Thus rooted, the paradigm recognized data beyond the visible, the tangible and, in this study, illuminated transcendent pedagogies in the educators’ words as data. The data elucidated the key role that spirituality plays in teaching and learning—as the lure of transcendence (Phenix, Citation1971)—and answered the guiding question: How does an Islamic research paradigm make visible transcendent pedagogies? By enabling metaphysical survey of the visible and invisible worlds (Al-Attas, Citation2005), the study’s research paradigm made discernable key aspects of a process of socio–spiritual development.

But rendering data visible was only the first step. The second step involved analyzing it through data–paradigm engagement. This paper discussed three themes related to socio–spiritual development (see ), which constitute an approach distinct from normative Western behavior management practices: first, establishing a tawhidic conceptual frame whereby the divine is centrally situated in the concentric circles of a person’s life; second, rehearsing holistic transformative actions, inclusive of verbal, physical, social, and spiritual practices; and, third, developing muhasaba, as ongoing, supported, triangulated self-reflexivity for self-development.

The third step inquired: What are the implications of this now-visible data? The first implication is that if consistent conceptual relevance in research design is important in conducting educational research meaningful to the community in which it takes place, consistent conceptual relevance is also important in education. Islamic educational praxis requires an Islamic paradigm for holistic reach across dimensions of the human being and objectives of education—both of which center transcendence. The second implication is that situating socio–spiritual development within an such a paradigm renders it agentic: intentionality in young Muslims’ actions, informed by multidimensional knowledge, is critically valuable. The socio-spiritual process of development might be considered in sites of Islamic education towards an endemic restructuring of behavior education towards a more holistic nurturing of character in the everyday. This would involve restructuring at the paradigm levels and rewriting philosophies of education to guide praxis.

In underlining the importance of this restructuring, the paper aims to reach two primary communities: first, to the educational community in which it took place; second, to a wider community of global Muslim educators, teacher-educators, and academics, many of whom are searching for alternatives to existing approaches rooted in limiting paradigms. But the research might also be useful for any educator who works with Muslim learners and any researcher who works within a minoritized academic community.

Researchers who situate their studies in authentic paradigms alternative to the mainstream may contribute onto-epistemic diversity to the currently homogeneous and hegemonic academy. Yet academic rigor must be maintained by internal-consistency and rigorous peer review of research designs, analyses, interpretations, themes, and implications. Exploring beyond the confines of a normative secular frame can never mean conceptual or empirical laxity. Ultimately, this paper aims to usher aspects of paradigms and pedagogies rooted in Islamic tradition from the epistemic hinterlands of the contemporary academy to the center, in recognition that they are engines driving a unique expression of young people’s development within an interconnected whole.

Ethical approval

The author was responsible for all the aspects entailed in developing the study, including: the conceptualization and design of the study, collecting and analyzing the data, and reporting the findings. Ethics approval for this research was obtained from the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (H19-00275).

Disclosure statement

There are no financial competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Claire Alkouatli

Claire Alkouatli is a Lecturer at the University of South Australia and a Learning Innovation Developer with the Ontario Institute of Studies in Education. Her PhD is in Human Development, Learning, and Culture from the University of British Columbia, Canada. Her qualitative research focuses on the roles of culture, relationships, and pedagogies in human development across the lifespan—particularly imagination, play, dialogue, inquiry, and challenge.

Notes

1 The 35 Muslim educator research participants taught in formal, full-time schools (12); informal, complimentary Islamic schools (18); and on a free-lance basis (5). All place and people names are pseudonyms; ethics approval for this research was obtained from the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (H19-00275). This study is overviewed in Alkouatli, (Citation2022).

2 After a critical examination of literature on the topic of Islam and education, Sahin (Citation2018) concluded that much of what has been written about Islamic Education has been from historical, sociological, and anthropological perspectives, rather than educational ones (p.1). He proposed the articulation of an academic, interdisciplinary field of Islamic Education Studies, to capture critical engagements involving “thinking educationally about Islam and Islamically about education” (p. 7). This paper is situated within this field; all literature reviewed was in English.

3 Similarly, Braun & Clarke (Citation2006) described the importance of qualitative consistency, whereby the theoretical framework and methods are themselves analytic decisions made by the researcher makes, which must match each other and match the object of the researcher’s inquiry.

4 Based upon conceptual and empirical research with key informants, Rothman & Coyle (Citation2018) described both consciousness and intellect as centered in the heart: “this center of consciousness within the human being is inherently connected and can be consciously connected to a primordial, divine consciousness” (p. 1743).

5 The connection between pedagogies and the development of consciousness has not been empirically studied in sites of Islamic education; the link between the two is posited from conceptual literature on the importance of Islamic social practices and the social environment in human development (eg. Obeid, Citation1988) and from sociocultural literature that describes the role of social practices, including pedagogy, in shaping human consciousness (eg. Daniels, Citation2016; Vygotsky, Citation1987).

6 Three themes discerned through thematic data analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) are discussed in Alkouatli (Citation2022).

7 Qur’an, 104: Surah al Humazah.

8 From a hadith in Sunan al-Tirmidhi (Al-Tirmidhi, Citation2010).

9 From a hadith in Sunan Abu Dawood.

10 Beyond the scope of this study, a question arises as to whether this may be precisely the problem with Islamic educational systems whereby colonial forces uprooted and denigrated paradigmatic frames relevant beyond secular ones.

References

- Abdalla, M., Chown, D., & Abdullah, M. (2018). Islamic schooling in the West: Pathways to renewal. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ahmed, F. (2014). Exploring halaqah as research method: A tentative approach to developing Islamic research principles within a critical “indigenous” framework. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(5), 561–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.805852

- Ahmed, F. (2021). Authority, autonomy and selfhood in Islamic education: Theorising Shakhsiyah Islamiyah as a dialogical Muslim-self. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(14), 1520–1534. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1863212

- Al Zeera, Z. (2001). Wholeness and holiness in education: An Islamic perspective. International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT).

- Al-Attas, S. M. N, Journal of Islamic Philosophy, Inc. (2005). Islamic philosophy: an introduction. Journal of Islamic Philosophy, 1(1), 11–43. https://doi.org/10.5840/islamicphil2005113

- Al-Attas, S. M. N. (1980). The concept of education in Islam: A framework for an Islamic philosophy of education. Presented at the First World Conference on Islamic Education, Makkah.

- Al-Faruqi, I. R. (1988). Islamization of knowledge: Problems, principles and prospective. In Islam: Source and purpose of knowledge. Proceedings and selected papers of second conference on islamization of knowledge. International institute of Islamic thought.

- Alkouatli, C. (2022). Muslim educators’ pedagogies: Tools for self, social, and spiritual transformation. Harvard Educational Review, 92(1), 107–133. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-92.1.107

- Al-Tirmidhi. (2010). Sunan al-tirmidhi. Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiya.

- Alkouatli, C. (2020). An Islamic pedagogic instance in Canadian context: Towards epistemic multicentrism. In A. Abdi (Ed.), Critical theorizations of education (pp. 197–211). Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill Publishers.

- Asad, M. (1980). The message of the Qur’an. Dar al-Andalus.

- Boyle, H. (2006). Memorization and learning in Islamic schools. Comparative Education Review, 50(3), 478–495. https://doi.org/10.1086/504819

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brinkmann, S. (2018). The interview. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed., pp. 576–599). Sage.

- Carter, S. M., & Little, M. (2007). Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: Epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1316–1328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307306927

- Chittick, W. (2011). The goal of Islamic education. In Casewit, J. (Ed.), Education in the light of tradition. Studies in comparative religion (pp. 85–92). Ottawa: World Wisdom, Inc.

- Daniels, H. (2016). Vygotsky and pedagogy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315617602

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2018). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed., pp. 1–26). Sage.

- Hammersley, M. (2013). Methodological philosophies. In M. Hamersley (Ed.), What is qualitative research? (pp. 21–46). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Kamberelis, G., Dimitriadis, G., & Welker, A. (2017). Focus group research and/in figured worlds. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed., pp. 692–716). Sage.

- Memon, N. (2013). Between immigrating and integrating: The challenge of defining an Islamic pedagogy in Canadian Islamic schools. In G. P. McDonough, N.A Memon & A. I. Mintz (Eds.), Discipline, devotion, and dissent: Jewish, catholic, and Islamic schooling in Canada. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Memon, N. A. (2021). Islamic pedagogy for Islamic schools. In K. Hytten (Ed.) The oxford encyclopedia of philosophy of education. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1515

- Memon, N., & Alhashmi, M. (2018). Islamic pedagogy: Potential and perspective. In M. Abdalla, D. Chown & M Abdullah (Eds). Islamic schooling in the West: Pathways to renewal (pp. 169–194). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mignolo, W. D. (2011). Introduction & part one. The darker side of western modernity: Global futures, decolonial options (pp. 1–76). Duke University Press.

- Mogra, I. (2010). Teachers and teaching: A contemporary Muslim understanding. Religious Education, 105(3), 317–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344081003772089

- Mosaad, W. M. (2022). Islam before modernity: Ahmad al-Dardīr and the preservation of traditional knowledge. Gorgias Press LLC.

- Nasr, S. H. (2012). Islamic pedagogy: An interview. Islam & Science, 10(1), 7–24.

- Obeid, R. A. (1988). An Islamic theory of human development. In R. M. Thomas (Ed.), Oriental theories of human development: Scriptural and popular beliefs from Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Shinto, and Islam (pp. 155–174). Peter Lang.

- Panjwani, F., & Revell, L. (2018). Religious education and hermeneutics: The case of teaching about Islam. British Journal of Religious Education, 40(3), 268–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200.2018.1493269

- Phenix, P. H. (1971). Transcendence and the curriculum. Teachers college record: The voice of scholarship in education, 73(2), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146817107300205

- Rahman, F. (1980). Major themes of the Qur’ān. Bibliotheca Islamica.

- Rahman, F. (1988). Islamization of knowledge: A response. American Journal of Islam and Society, 5(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.35632/ajis.v5i1.2876

- Rothman, A. (2021). Developing a model of Islamic psychology and psychotherapy: Islamic theology and contemporary understandings of psychology (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

- Rothman, A., & Coyle, A. (2018). Toward a framework for Islamic psychology and psychotherapy: An Islamic model of the soul. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(5), 1731–1744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0651-x

- Sahin, A. (2013). New directions in Islamic education: Pedagogy and identity formation. Leicestershire, UK: Kube.

- Sahin, A. (2017). Education as compassionate transformation: The ethical heart of Islamic pedagogy. In P. Gibbs & O. Gibbs (Eds.), Pedagogy of compassion at the heart of higher education (pp. 127–137) Springer.

- Sahin, A. (2018). Critical issues in Islamic education studies: Rethinking Islamic and Western liberal secular values of education. Religions, 9(11), 335–364. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110335

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky. Volume 1: Problems of general psychology (R. W. Rieber & A. S. Carton, Eds.). Plenum Press.

- Winter, T. (2016). Education as ‘drawing-out’: The forms of Islamic reason. In N. A. Memon & M. Zaman (Eds.). Philosophies of Islamic education: Historical perspectives and emerging discourses (pp. 26–41). Routledge Research in Religion and Education.

- Zine, J. (2008). Canadian Islamic schools: Unraveling the politics of faith, gender, knowledge and identity. University of Toronto Press.