Abstract

Placing myself as a rejected doctoral student (2010–2022), this paper examines the emergent nature of identity formation across time and space. While presenting a layered account of my lived experience in seeking pathways of pursuing doctoral study, each reading experience leads me to produce my identity(ies) and situated knowledge(s) as an outsider. To illustrate the complexity of one’s lived experience, I choose to present my work in an unconventional format of scholarship. By giving voice to an academic outsider, this paper adds to the nascent literature on the non-linear becomingness of academic identity. Further, this form of scholarship advocates for writing differently as a means to empower minorities to articulate their diverse epistemology. The implication of writing up this public letter helps me mitigate feelings of vulnerability and rebuild self-confidence, creating a space of being and its potential to reconstitute the self in their becomingness.

Dear readers

As an immigrant teacher, I don’t have a name in academia; but I do have a voice. I wanted to tell you a story of mine a long time ago, but at the time, I didn’t know “how” to get my authentic words out within this “inclusive” community. After 4 years of writing and rewriting, this letter serves as a counter-narrative to understanding the lived experience of immigrant teachers (Yan et al., Citation2024). This work further extends my previous article “A Non‑native Teacher’s Reflection on Living in New Zealand” (Yan, Citation2020).

You will soon notice that this letter is a hybrid of text, some of which was written years ago. I did not want to “erase” my earlier writings, so new layers have been added in the coming years. I have now achieved what was so elusive for so long, but the journey of frustration is worthy of discussion as it implicates issues such as citizenship, social class, otherness, lack of necessary resources, and proper guidance for minority groups of people. I hope this letter contributes to the ongoing dialogue on the becoming of “an academic outsider” (Reyes, Citation2022). This is the story of and about my arrival (in academia).Footnote1

*** ***

Who I am: the voiceless (other)

I look at where I am going

And where I am. And it never makes sense.

But then I look back at where I’ve been,

An [assemblage] seems to emerge, and if I project forward from that pattern,

Then sometimes I can come up with something—

I can see very clearly on my own being and becoming.Footnote2

This public letter was born out of my fraught experience(s) of seeking a pathway to pursue doctoral study as an immigrant teacher. For a long time, I have suppressed my inner voice, conforming my academic works to the rules of social sciences, as I naively believed that rigor was superior to imagination, intellect overshadowed feeling, and theories took precedence over concrete events. So great was the pressure to become one of you with a doctoral degree and the fear of not being accepted by academia—I don’t want my feelings to be misconstrued as a personal grudge, but rather as a reasoned argument. (Now in retrospect, I realized that the fear of uttering my emotional truth is a lack of belonging and confidence within this “scholarly” community).

The human “I” is still in a liminal space—torn between the desire for authenticity and the need to conform to the stringent and formal conventions of academic scholarship (Yan, Citation2024d). Without an established reputation, like Tony E. Adams, the abject “I” is concerned that too much personal voice might dilute their ‘emerging’ status as an academic scholar. This letter adopts an unconventional writing style making extensive use of “intrusive” discourse, creating a dialogical space and forging an aesthetic textuality. By inserting additional “texts” as a symbolic marker of marginalization and a form of resistance, this layered discourse problematizes conventional academic narratives that tend to present the academic experience as “having arrived” rather than focusing on the messy process of “becoming” and the many struggles, frustrations and failures that are often experienced in the interim.

My arrival

The dawn is breaking, yet the sky is veiled with fog and light drizzle. Hazy rays of sunshine struggle to herald the beginning of the day. Higher in the sky, a complete spectrum of colors emerges, illuminating the refractive index of light in the fog. A 20-year-old Asian figure, sallow, a bit thin. His face remains obscured. His hair is a little messy, his jumper inside the suit is either vintage or just old and with holes and sort of threadbare. He wears glasses, peering at the world through these dual lenses. A MOMENT TO REMEMBER.Footnote3

***

The first week after I arrived in New Zealand in 2009, I felt like stepping into a new world that held promise to my future. Within a week, I volunteered to be a Mandarin teacher at a local primary school called St Joseph’s—the oldest Catholic school in central Auckland.

Although I tried to apply for other odd jobs, teaching languages has always come naturally to me. With a working holiday visa, the reality soon kicked in that being a foreigner, it was virtually impossible to find a “proper” job back in 2009. I then forged a contingency plan—I wanted to obtain the right to stay permanently in New Zealand (through academic studies).

Within a month of my arrival in this foreign country, I took the initiative to apply for a course-based master’s in applied linguistics. Ranking has always been an important consideration for Asian students when choosing an institution in the West. So, I chose a “top-notch” university in the country—The University of Auckland (UoA).

As I anxiously awaited a response, days turned into weeks, and weeks into months. The weight of my aspirations hung heavy on my shoulders, and every passing day brought a mix of hope and trepidation. Then, like a burst of sunlight breaking through the clouds, an unconditional offer from UoA arrived. Exhilaration coursed through my veins, filling me with a renewed sense of purpose. My goal was to complete my master’s and then pursue my Ph.D. studies. A beacon of academic excellence became my destination. A well-executed plan?*

* But as I reflect on my well-executed plan, I can’t help but wonder: Is it enough? Does it truly capture the essence of my journey? The road ahead is still uncertain, and the pursuit of my dreams remains a constant dance between ambition and doubt. Yet, with each step, I am driven by a determination to carve my path, to leave a mark on this world that transcends borders and defies expectations.

*** ***

While understanding how I lived through the process of becoming an outsider, I turn to Kristeva’s (Citation1982) concept of abjection that helps to “[elucidate] that process of the human ‘I’ expulsion, as part of establishing and constantly re-establishing the self” (Tesar & Arndt, Citation2020, p. 1105). The theorization of writing this way has previously been discussed by Yan et al. (Citation2023): To what extent, do academic scholars allow the marginalized as the first-person narrator, being the first author, exploring their own being and knowing? That is why it is critical to preserve “my speaking body” without academic operations, which is why it is important to keep my original utterance. Otherwise, the speaking body of the text would once again lose its raw authenticity in time and space.

Bringing up my own insides “involves tacitly acknowledging academic abjection” (Henderson, Citation2014, p. 35) and such provocation of abjection is situated in the liminal, in-between spaces in what Kristeva (Citation1991) might see, that is, an ongoing and constant construction of I; of the “ongoing reworkings of ‘moments’, ‘places’, and ‘things’—each being (re)threaded through the other” (Barad, Citation2010, p. 268). Through a personal process of realistic reproduction of a particular life, my vignettes serve as both data and findings, conveying a profound understanding of the self and the situation.

Understanding my becoming, through layered texts, allows me to map the multiplicity and contingency of subjectivity in relation to social, cultural, historical, material and affective dimensions. The use of distinct narratives offers commentary, as “double-voiced” discourse (Bakhtin, Citation2010, p. 198), accommodating “discursive or rhetorical contexts where one is concerned primarily with explaining or comparing opinions” (Morson & Emerson, Citation1990, p. 167). Whilst acknowledging that lived experience requires interpretation, Derrida’s (Citation2016) notion of marginalia, or “supplementary mimesis,” further invites us to rethink these “markings” as real meaning (p. 290).

*** ***

I am a cash cow

Being a foreign student in the Otherland,

I was burdened with a heavy toll.

5 times the tuition fees of my local counterparts.

The weight of this financial and emotional burden

Threatened to suffocate my dreams.

Determined to pursue my education, only did I find myself

Immersed in a world of undocumented work, necessary to scrape together

Enough money to pay my rent. Well, that’s enough!

But my days turned into nights, and my nights blurred into sleepless shadows.

I became a nocturnal creature, sacrificing rest for knowledge,

My weary mind battling the demons of insomnia and the abyss of depression.

I was trapped in a twisted dance, my life teetering on the precipice of imbalance.

Despite the exhaustion and uncertainty, I approached my studies with unwavering enthusiasm.

In retrospect, I see the futility of my mission and I now realize that I was destined to fail. I want to shout at my younger, naïve self: How are you going to become a high academic achiever in these circumstances?! Can’t you see there is no equity in the academic “business”? But of course, “he” does not listen. From the vantage point of the present, I watch, a spectator to his doomed expedition. I wait, knowing that his path is strewn with obstacles too insurmountable to overcome. And as I bear witness, I can’t help but yearn for his innocence, for that unyielding spirit that dares to defy the odds. But deep down, I know the bitter truth that awaits, the harsh reality that passion alone cannot conquer the merciless forces that govern our world.

***

“You’re not one of us.”

Born in the 1980s, I am the only child in my family. In 1995, my parents got divorced. I lived with a single mother who passed away before I began my undergraduate studies in 2003. My thirst for a Western education, an insatiable desire to wield the imperial language with eloquence, burns brighter than ever. The impact of the “One Child Policy” has emboldened a generation to dare to dream. Having worked for 2 years as an English teacher in my home country, I made the bold decision on a daring odyssey to New Zealand in 2009, seeking to immerse myself in the kaleidoscope of life’s experiences. (Yes, that was when I embarked on my well-executed plan, remember?)

Yes, I was born in China.

Despite my wanderings across foreign lands for over a decade,

I am forever branded as Oriental—

My non-native accent, personal beliefs, and mannerisms casting me as such in the eyes of others.

Still, I can vividly recall that afternoon lecture called ‘language analysis.’

The face of the lecturer, forever etched in my memory, watched us intently.

As we debated the grammatical merits of a particular English sentence,

She turned to us, her gaze penetrating our souls, and asked,

“So native speakers, raise your hands. Do you find this sentence acceptable?”

In that moment, amidst my international peers,

I felt the sting of public exile, my shame laid bare for all to see.

For the first time, I witnessed that the non-native group was singled out in the public sphere,* because of their linguistic deficiency that we could not tell what is right and what is wrong(?). I felt shameful and embarrassed because of my cultural background (that I will never possess a 100% sense of intuition in English expression). Despite meeting the admission requirements, English as my adopted tongue has nonetheless disadvantaged me in academia. (It still takes me a long time to construct a paragraph.) The intimidation of expressing my thoughts and ideas lingered, as I struggled to find my voice in such “inclusive” classroom.

* By thinking more concretely about institutional spaces, Ahmed (Citation2012) questions “how some more than others will be at home in institutions that assume certain bodies as their norm” (p. 3).

*** ***

In telling my story, I had struggled to apply conventional modes of writing to unpacking my lived experience. While presenting “abjection,”* this ongoing search for an outlet for my work was also challenged by the desire to present the self as a “legitimate” member of the academic community. Having so far received a master’s (by coursework), I felt like an outsider in academia. Even though I was able to publish from time to time, I faced significant challenges in finding an academic willing to guide and support me in the collaborative process of knowledge production. (I am only viewed as their “participants,” providing them data.)

* This is Kristeva’s (Citation1982) notion of abjection, understood as “that which is cast out [or rejected]” (p. 3). This post-structural conception offers both theoretical and analytical lenses in this letter, allowing for the exploration of Otherness—one’s marginalized experience of pursuing doctoral study and of becoming an academic without a PhD. Placing the self within a unique context, the hybridity of autoethnography and creative writing constitutes my resistance to hegemonic bodies of discourse, becoming the means through which marginalized groups can preserve their own being and knowing. Writing about the self allows me to forge a voice and construct a sense of autotheory (Fournier, Citation2021), shared experience for the purposes of extending sociological understanding.

Not knowing who I am and what I become, I naively write with a “polished,” “fake” accent to disguise my outraged feelings of inadequacy (Yan, Citation2021b).* I have come to realize that my suffocated “being” does not lead me anywhere but to lose my power of becoming. Owing to my lived experience of being the rejected, I have gradually pushed to the edge and mastered the “subtle art of not giving a F*ck,” (Manson, Citation2016) and not to “become the master’s tool” (Ahmad, Citation2017, p. 160)! I have found ways “not to reproduce its grammar in what I said, in what I wrote, in what I did, in who I was” (Ahmad, Citation2017, 4).

* Recently, I have encountered a wealth of “non-traditional” scholarship that is already there!! Unfortunately, I did not know that one can write the self as a unique type of research practice. During my postgraduate studies, our lecturers advised against using the first person in academic essays. Back then, I wished that I had read Moreira and Diversi’s (Citation2010) work “When janitors dare to become scholars.”

After years of searching for a mode of research practice, I now appreciate the power of writing as an inquiry (Richardson & St. Pierre, Citation2005), performing autoethnography (Denzin, Citation2018), the use of poetic inquiry (Faulkner, Citation2016), and writing intra-actively with desire (Wyatt and Gale, Citation2018) amongst other forms of arts-based works.

(Revising this manuscript, I have sensed that my academic voice has emerged and strengthened through writing and reading that orient my thinking (Yan, Citation2024d). Writing the self is a form of self-care, which in turn allowed me to gain some confidence in my own thinking. Engaging in the knowledge production, including the publication of book reviews (Yan, Citation2023b, Citation2023c, Citation2023d, Citation2024b, Citation2024c), has further strengthened my positionality of becoming as a consequence.) As Marshall McLuhan (Citation2001) reminds us, “[t]o live and experience anything is to translate its direct impact into many indirect forms of awareness”. (p. 183)

*** ***

This public letter examines the emergence of an academic identity forged in perceived failure and frustration—that of an identity that speaks to resilience and overcoming. Such endeavor is needed because the rejection of doctoral applications is rarely discussed and written about. In presenting such identity work, Ronai’s (Citation1992) layered account allows me to explore my personal experience of academic pursuit over the period between 2010 and 2022. This non-linear writing reflects many points of view, serving as sensitizing concepts that orient my reflective inquiry. Originating with Herbert Blumer (Citation2017), sensitizing concepts rest “on a general sense of what is relevant”, offering “directions along which to look” rather than “providing prescriptions of what to see” (pp. 71–72).

Through a layered account, it portrays the complex relationship between being and becoming an academic outsider. Butler (Citation2012) agrees with Foucault’s critique on the subject of desire that “not only accounts for an experience but determines that experience” (p. 238). Becoming represents the process of being in-between, of struggling to reach the “promised land” of academia. Being represents my realization that I have always been an academic, albeit differently. Through the dialogical process, I can see more clearly of my struggle because I attempted to reconcile two realities—being and becoming—realities that cannot be reconciled.

Such an “emerging” status carries with it an inner voice, invoking Foucauldian power as applied by the self on the self (Foucault, Citation2012). The marginalized must examine the self in order to grasp and seize future possibilities for one’s becomingness. The concept of becoming, borrowed from Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987), captures the movement and dynamism of any form of being as always in process, and is particularly oriented against the idea of linear development. In recalling my lived experience, I relied on my memory to search for those moments. While each event offers a singular static perspective, the layers of these views then unite my emergent identity as an ongoing, open-ended process.

As a point of departure, these aesthetic materials, a response of feelings, moods, or emotions to one’s lived experience, will be in close dialogue with poststructural conceptions. Producing a rich situated textuality, a layered account serves as an alternative, transformative and interpretive search for self-understanding and self-becoming. A layered autoethnography enables the self to amplify multi-voiced selves between the self and other, examining their own be(com)ing of an academic outsider. These hybridity discourses are interweaved to complicate established knowledge about “success” and “failure” in the context of doctoral education admissions. This letter’s original contribution lies in offering an emic understanding of the Other’s frustrated pursuit of an academic career.

Such lived experience then empowers me in the time to come, to theorize the conditional citizenship of academic life—a liminal status occupied by the selected group of people (Reyes, Citation2022). In this letter, I share my silenced existence and “failure” as valuable sources of Donna Haraway’s (Citation1988) concept of situated knowledge in terms of the forging of an identity—an academic outsider. To do so, I confront the structures and constrains of conventional academic writing, blending my own personal experiences with the literacy arts to lay bare the ways in which the university “selects” the so-called best candidates in their rigorous process of selection based on merit.

*** ***

Terminality. Period!

The following year marked my graduation with a master’s degree, a moment of pride tinged with a sense of unfulfilled potential. However, as the months unfolded, a harsh reality set in—my hard-earned degree held little value within the confines of New Zealand. It had been tailored for international students to return to their homelands as English teachers or for local graduates to venture abroad or teach locally. As a non-native speaker, the path to securing a position as an ESL teacher proved arduous, strewn with obstacles at every turn.

This so-called masters degree did not qualify me as a K–12 teacher in New Zealand, nor did it serve as a gateway to further academic pursuits. Its curriculum comprised eight subjects devoid of any research component, rendering it a “professional” master’s—an end in itself. “Terminal” being the operative word, in the most poignant sense, as it marked the termination of possibilities.* Such revelations were obscured from me when I completed the program. I want to shout at him: ask for a refund! Get back your testamur. But, of course, he remains oblivious to my words. At the time of application, my singular focus revolved around one burning question: Would I gain admission to a graduate school in a Western country?

* The terminal body is a “body from which biomedical promises have been tacitly or explicitly withdrawn, a body upon which any medical action is deemed to be futile” (Farman, Citation2017, p. 101). The reader might venture to add, then, that I am being dramatic, and full of self-pity. When promise, hope, and potential have been withdrawn from my speaking body, I do not know what you call it. Farman (Citation2017) further states, “terminality requires a body whose time is limited to itself only; it requires not a body in (or even out of) time but a certain kind of time in the body”. In this regard, terminality is experienced as a body that is constantly aware of its own impending end. This felt experience links it in part to the elimination of a future and the confinement of person to a finite body whose time is limited entirely to itself. Meanwhile, Farman (Citation2017) argues that terminality changes the embodiment of time in a specific way: feeling temporality as a countdown in hours, days, or months. In my case, it has been over a decade.

***

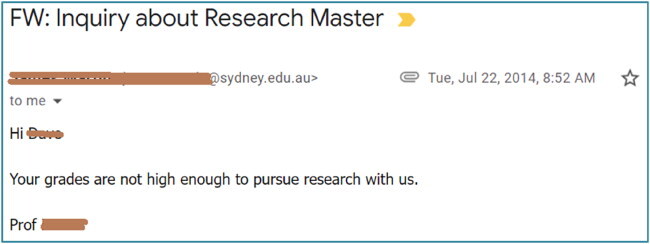

While constructing my vignettes, I scrolled through previous email exchanges (2009–2022) refreshing my memory of contacting several universities. I am surprised that I reached out to so many people working in higher education. As I read through hundreds of emails sitting in my inbox, each email exchange was like lighting a match—giving me a new, if short-lived, hope. Longing for conflagration. Searching for salvation. I worked so hard and I did nothing wrong. Over the years, I desperately searched for a pathway to change my status from being the rejected (doctoral student) to the accepted (being) in academia. This first digital vignette serves as a reminder of a moment when I found the courage and hope to reach out to a research program at the University of Sydney. The following is their terse reply:

Digital Vignette #1. Communicating with a potential supervisor.

***

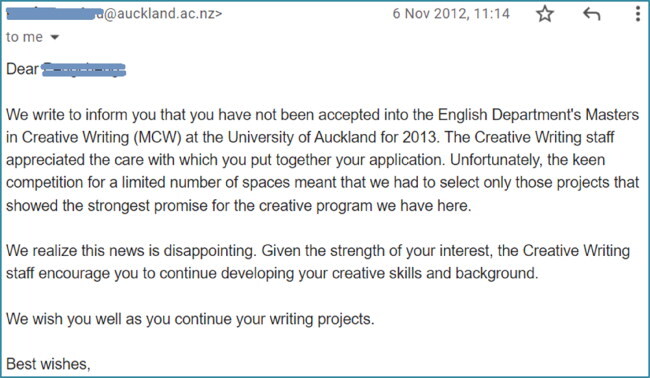

During the challenging months of 2010, when I couldn’t find a job in New Zealand, I embarked on a journey of self-expression. In those very moments of uncertainty, I poured my heart into the creation of an autobiographical novel. With unwavering determination, I self-published this intimate work on CreateSpace (now owned by Amazon), revealing a newfound passion for the art of creative writing. (In that daring leap of faith, I have now resolved to explore the uncharted realms of storytelling at the doctoral level, giving voice to untold tales and embracing the profound potential of literary creation.) The following vignette served as a poignant reminder of the profound courage that surged within me, propelling me to venture into the realm of creative writing. (The moment I departed from my home country and became an immigrant, I carried within me a profound sense of “hope” for my future.*)

Digital Vignette #2: The outcome after submitting my creative portfolio.

* Now I realize that my incessant pursuit is not a cause for despair but for hope that has been denied by injustice and equity. As Freire (Citation1993) reminds me, “hopelessness is a form of silence, of denying the world and fleeing from it” (p. 91). These situations stand out, revealing their true “historical dimensions of a given reality” (p. 99).

In the end, there is a newfound understanding of truth. Many “students” from a migrant background possess a limited understanding of the nuances associated with their chosen academic programs. It is through personal experience, after a decade of endeavor, that I have acquired “an insider knowledge,” that is, the admission process of a doctoral program in the social sciences, in both New Zealand and Australia, requires prospective applicants to have previously undertaken a research project, attaining a minimum grade of 80% and, preferably, having published peer-reviewed papers. (These higher education institutions might say this information is inaccurate or misleading. So, prospective students need to do their due diligence.) In many cases, their verbose website has never explicitly conveyed this information.*

* Unfortunately, the current landscape for doctoral applications is that many universities would only consider ranking and shortlisting high-achieving applicants. This highly selective process is understandable. However, university websites should have explicit selection criteria (including their ranking system), giving prospective students clear guidance to help in their doctoral preparation. Michel et al. (Citation2019) critique the tendency for the criteria to evaluate applicants not being plainly stated on the application web page, and thus applicants may not be able to take advantage of such important information when preparing their applications for graduate school effectively.

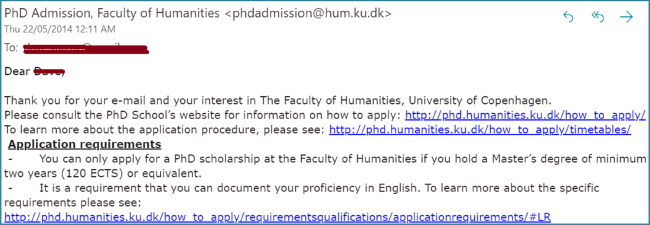

Regrettably, my four-year bachelor’s degree with a thesis in China did not align with the standards of an honors thesis in many western countries. Despite my diligence as a student, I did not achieve exemplary grades during my master’s studies in New Zealand and, as a result, the utilization of this qualification only served to detrimentally impact my doctoral application in other countries (see Digital Vignette #3).

Digital Vignette #3: I sought advice to confirm if my master’s degree could be recognized, which would enable me to pursue a PhD in Europe.

******

The purpose of presenting these digital vignettes is to emphasize my story is backed by factual evidence of what transpired. For more than 10 years, I relentlessly pursued a path to enter a doctoral program. I even explored options of doing a second master’s degree, or even an honor’s degree. Desperate for a second chance to prove my intellect and abilities, I found that each endeavor only deepened my sense of “failure,” reinforcing my position as the Other: an academic outsider. *

Doors closed, one after another,

Their echoes resounding with the bitter taste of defeat.

Inevitably, I reached a breaking point, and I had to relinquish my pursuit,

Burying the dying body deep within me.

In the darkness,

Devoid of hope, I could not envision—

The emergence of a new dawn.

It suddenly occurred to me that I lived in the land of no hope,

A false promise, I cherished to be true.

All pathways appeared to lead to a dead-end street.

Why, I now ask, would one embark on this arduous journey

Of endless search for the power of discourse and knowledge

Of uttering one’s own being and knowing?

* To ensure accuracy, I must correct myself. I was indeed offered a place in a coursework master’s at another institution, but I chose not to accept the offer. The exorbitant tuition fees for international students had reached unsustainable heights, masking under the new rhetoric of calling us “international citizens.” Paradoxically, while my desire to enter a PhD program burns strong, I am equally steadfast in my refusal to once again be reduced to a mere “cash cow” (Robertson, Citation2011). It serves as a stark reminder that admission into such programs is often driven by profit rather than merit. My experience of studying abroad has given me a profound understanding of the true value of higher education in the West and the system’s tendency to selectively favor “certain” students.

As Zivony (Citation2019) points out bluntly, “academia is not a meritocracy” (p. 1037): some individuals have already got certain advantages, because of their linguistic background and financial support. Although their cumulative effect is hard to quantify, “the privileged” have no doubt an advantage over those others who possess no financial security, linguistic privilege, cultural capital, and educational advantage. These factors can be striking, illustrating both the continuing disadvantages faced by minority groups. In line with Tavares (Citation2021), “foreign” students often encounter barriers to equity and inclusion. For example, the curriculum could disadvantage them by privileging local knowledge and experience. There is also a lack of urgency to transform this situation in the higher education. In other words, some get a head start while others are left behind through no fault of their own.

*** ***

Voicing the voiceless

While navigating scholarly work, I faced the challenge of finding a voice that resonates with my lived experience. To date, most autoethnographies have been written by people with a doctorate or in the process of completing their doctoral studies. Rarer are the voices of a holder of master’s degree, let alone the rejected group of students. In short, such voices are rarely heard.

The reader (actually, a reviewer) queries why it matters to me when the voice of masters students is not in the autoethnography.* To understand multiple identities within a single self, representation is everything when the minoritized and othered cannot find their voice or are granted a voice, as it diminishes their power and ability to navigate the unknown. In academia, the appropriation of autoethnography by scholars writing about themselves is certainly nothing new (Brooks et al., Citation2018; Herrmann, Citation2012; Humphreys, Citation2005; Koh, Citation2012; Learmonth & Humphreys, Citation2012; Poole, Citation2022). Morley (Citation2021) is among a group of academics who express a shared sense of “bleakness and despair,” questioning the continued relevance of social class (p. 8).

* I wrote a large proportion of this paper when I was a masters student, trying to get onto a doctorate. The issue of masters students’ non-existant, or silenced voices in the academic scholarship were problematic for me at the time. This liminal space is an area of gap that has yet to receive much attention. It is one of aspiration and reality, where getting onto a doctoral program is really tough. Such lived experience of a pre-doctorate really gives me a sense of how frustrating and disorienting academic life has become. More concerningly, I assumed that obtaining a doctorate grants certain groups of ‘people’ legitimacy, assigning them a recognizable positionality as an academic scholar.

Focusing on the long hard road from the position of “not having a doctoral degree” to “trying to get one,” this public letter questions this liminal space of doing, being and knowing in the practice of knowledge production. It challenges the notion that, within the current neoliberal academic milieu, only those with a doctoral degree are recognized as “academics” (although there are exceptions of academics holding masters degrees), highlighting the limited pathways that grant certain groups of people a license to produce so-called knowledge. The commitment to publicly examine personal theories born from experience thus embodies Holman Jones et al.’s (Citation2016) call to “embrace vulnerability with purpose” (p. 22). The once-silenced voice highlights a marginalized experience of “being” that does not call for an explanation, but to enlighten others through storytelling in better understanding who they are and what they choose to become. This public letter exemplifies how to galvanize that voice to smash that culture of “silence and indifference” to actualize their potential intellectually, and develop a new awareness of self, and the right to be heard (Freire, Citation1993, p. 116).

*** ***

The operational efficiency

Despite finding a position in a language school, the limitations of being an ESL teacher with a non-native accent cast a shadow over my future prospects. Admittedly, my teaching experience in New Zealand did give me some confidence owing to the positive feedback from students who felt inspired and saw in me a representation of what they could potentially achieve. Often, people would assume that I only taught Chinese students back then (because I am Chinese?). Working at a language school gave me the opportunity to teach students of various ages and cultural backgrounds. They include individuals from Korea, Japan, Cambodia, Vietnam, Colombia, Chile, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Germany, Spain, Italy and Russia. (That’s as far as my memory serves.) Eventually, I became more confident than before that my accent no longer bothered me at all.

After six years of teaching English in Auckland, however, my career had seemingly become stagnant. I longed to reach my full potential. During my exploration of doctoral programs, I stumbled upon an Ed.D. program (at the University of Melbourne). As I delved into its admission requirements, a spark ignited within me. In that moment, I glimpsed a ray of light, a glimmer of hope, and a renewed sense of purpose… life! I poured my passion and determination into a heartfelt personal statement, even though it was not required (in Australian universities). Soon after, an unforeseen obstacle surfaced: I needed to secure at least two academic reference letters.

Reflecting on my experience as a tertiary student, it became evident that most, if not all, academic lecturers showed little interest in connecting with students pursuing coursework master’s degrees. (Some even appeared prouder of peddling their own textbooks to students! A clear conflict of interest, isn’t it?) Five years had passed since my studies, and many of my former lecturers had moved on to the UK or the USA for their own careers, while most had faint recollections of me. Filled with a sense of desperation, I approached a former professor in the field of applied linguistics. Considering his reputation, if he wrote The Letter for me, it might carry some weight to open doors for my doctoral application.

***

I arrived earlier than the agreed time, waiting outside his office and feeling all warm-hearted. I knocked at the door, walking into his office where I saw piles of documents and books. He was sitting comfortably on an armchair. He appeared to know my purpose of visiting straightaway.

He gave me a piece of advice rather bluntly—

You do know that The University of Melbourne is a very top university. And based on your grades, I wouldn’t write a recommendation letter for you […] My advice is that you consider some lower-ranking universities in Australia or the UK, where you might have a better chance. Well, if you excuse me, I have some things to attend to.

His words carried the maximal efficiency and clear direction. In truth, I was embarrassed but I appreciated him for making time to meet me in person. (I should have told him that I knew his “name” since high school because of my interest in applied linguistics. But did he care what I was about to say?)

I left his office, feeling the door slammed shut with that empty echo I had come to expect. I felt like a third-rate being—I lost my dignity for being a human.

In retrospect, the professor informed me of the pronounced reality which I appreciated. For what he said eventually materialized, as a few months later, I received the outcome of my doctoral application. Surprisingly, the wording used in the admission letter mirrored that of the previous rejections. The operative keywords are: rigorous, selection, competitive, ranking, not high enough & best wishes.

That was the year of 2015. The sky was veiled with fog and light drizzle…

Suddenly, the frustration over the years overwhelmed me as I cried out in indignation while James Arthur’s singing “Impossible” was in play. To a terminal body, hope is what keeps me breathing (Farman, Citation2017). From that moment, I lose it.* My humming voice filled with tears and unanswered longing… This is an actual event that took place in Auckland prior to my decision to move to Australia, and it is not written for dramatic effect.

I remember, years ago

Someone told me I should take

Caution when it comes to love, I did […]

My illusion, my mistake

I was careless, I forgot, I did

And now

When all is done, there is nothing to say

[My dream’s] gone and so effortlessly

And my heart is broken

All my scars are open

Tell them what I hoped would be impossible

Impossible

Impossible

Impossible […]Footnote4

* Coming from a lower-class background, I was raised with a profound belief in the virtues of perseverance and diligence, as these qualities became vital when there were no other resources to rely on. When recounting my story, all these queries have led me to feel uncertain about the validity of my own experiences. Engaging with Dale (Citation2016), I came to realize, almost a decade later, that something that the professor did not tell me—“anyone can do it” (p. 200)—becoming an academic. However, it “demands an immediate recognition that this anyone is someone” (p. 222), who has to grab the tradition, play what they can, and make it into something that fits their abilities. Along the process, they will have to collate, construct and protect their own histories and emergent identities. Whether there is any justice in educational equity and access, “anyone can do it” can only be made possible, requiring “a decision from someone other than anyone” (Dale, Citation2016, p. 224).

*** ***

Positioning myself as the “rejected” in a specific history and culture, writing this layered account helps me gain a clearer perspective on my life as an immigrant and the politics surrounding marginalized experiences while striving to establish myself within academia. Through tracking meanings about “failure,”* I engage in a dialogical reflectivity of working out this “othered” experience. To do so, the notion of abjection allows me “to transform the conceptions of Otherness,” providing a way “of articulating the potential of having arrived in a new physical or conceptual space” (Tesar & Arndt, Citation2020, p. 1106).

* As Burford (Citation2017) claims, writing failure and despair can serve “as a rich analytic tool that can generate ways of thinking, doing, and being” (p. 457). By dislocating my identity(ies), writing about my ‘failure’ enables me to see through the complicated entanglements of hidden forces—socio-cultural capital and identity politics in academia. I now feel empowered to ‘choose to’ become the academic Other, that is, an academic who is ostensibly on the inside, but who chooses to remain on the edges in order to embrace a deeply embedded memory that has altered how one sees the self.

Methodological notes: writing the self within liminality

To delve into the becoming of an academic outsider, I have relied on the concept of the dialogical self as a generative framework that guides my reflective thinking. By placing I-positions in a dialogical framework, it enables me to express my selves from specific points of view taking place between different positions across time and space. Hermans et al. (Citation1992) conceptualized the self as the multiplicity of often competing and contradictory identities, among which dialogical relationships emerge and are interwoven. The notion of the self-as-knower is expressed in a sense of personal identity through time, as Hermans (Citation2003) contends that the self is “intrinsically involved in a process of positioning and repositioning” (p. 83).

Here is writing in which an embodied experience provides the basis of knowledge that “embodies a theory of consciousness and a method of reporting in one stroke” (Ronai, Citation1995, p. 396). Through a dialogical self, multiple accounts of the same phenomena have been written over time and written by different versions of the self. This multiplicity of I-positions then allows for the self to materialize a layered account of being and knowing. It depicts “a continuous dialectic of experience, emerging from the multitude of reflexive voices that simultaneously produce and interpret a text” (Ronai, Citation1992, p. 396). The layered approach considers concrete personal texts to be as important as abstract analyses, as Ahmad (Citation2017) would argue that “the personal is theoretical” (p. 10). Moreover, a layered textuality allows data collection and analysis to proceed simultaneously. In writing about that personal experience, the history of ideas “that is in touch with a world” is also a form of theoretical work (Ahmad, Citation2017, p. 10), advancing the academic discourse on the marginalized position.

To this layered account, the analytical process is inspired by Henderson (Citation2014), “craft[ing] a methodological use of abjection” that is pushing and being pushed by the “data” (p. 23). In achieving that, close textual engagement with theory leads to the resultant writing (Jackson & Mazzei, Citation2011), seeking “to magnify the emotions and processes of signification” that surround my subjectivities and becomingness (Henderson, Citation2014, p. 23). Through an explication of abjection, this theoretical lens offers a productive use of the liminal space (Tesar & Arndt, Citation2020), where the abject recognizes the-I that is transforming and constantly re-establishing the self—the becoming of an academic outsider. The emergence of a hybrid identity is thus foregrounded in “the historical situation of the body” (Butler, 1987/Citation2012, p. 234).

The notion of outsider resonates with Henderson (Citation2014) in that “academic abjection” serves “both as a conceptualization of a situation of knowing and not knowing, and as a mode of writing research” (p. 24). Meanwhile, the authorial “enunciative position” and “analyst (intellectual)” voice(s) are further understood by “a reading experience which may … lead us to the very edge of our identity as speaking being” (Smith, Citation1996, pp. 154–158). Through the layered account, the-I “live[s] in the story, becoming in it, reflecting on who one is becoming, and gradually modifying the story” (Frank, Citation2013, p. 163). Such reflectivity enables me to ascertain where I have been, and to discipline the self in order to become who I want to be.

The hybridity of multiple voices, including the personal, the poetic, and the scholarly ones, conceives of the formation of the self as an “emergent process” that is not a linear experience but a fragmented, self-adjusting one (Rambo, Citation2005, p. 583). By offering an impressionistic sketch of layers of experience, an interpretation of the narrative emerges, while thinking with theories and related literature (Jackson & Mazzei, Citation2011). In so doing, both the reader and the self shall interrogate my own position of knowing or not knowing. This innovative practice of writing serves as Bakhtinian “surplus” to elucidate the necessary conditions for dialogical interaction (Bakhtin, Citation2010).

To convey the complexities of becoming an academic outsider, I choose to present what happened to me in literary forms, allowing for “multiple ways of representing reality” (Wertsch, Citation1993, p. 13). By “bringing up the ‘data’ that serve as materials for analysis,” a collection of aesthetic texts opens up a liminal space to examine the notion of becoming abjection (Henderson, Citation2014, p. 24), through the identity of a foreign student, an immigrant teacher, a rejected doctoral applicant, and the abject other. This liminality, intertwined with the emerging status of terminality, necessitates the “plural consciousness” that embodies multivocality, “create[ing] the background necessary for his own voice, outside of which his artistic prose nuances cannot be perceived, and without which they do not sound” (Bakhtin, Citation2010, p. 278).

To weave together a layered account, my personal narratives are further strengthened by digital vignettes (of validating my memory), to locate and make sense of multiple identities, hidden desires, and silenced voices within the self. In telling my stories of doctoral pursuit over a decade (2010–2022), I have to think hard and select suitable examples that set up specific scenes, contextualizing my becomings and inviting discussions. In presenting these vignettes, I open a window through which readers can see an invisible body “assembled from shattering, from splattering, an archive whose fragility gives us responsibility: to take care” (Ahmed, Citation2017, p. 17). Apart from “ask[ing] what a text means, what it says, what is the structure of its interiority, how to interpret or decipher it,” I take into account the advice provided by Grosz (Citation1994) that “one must ask what it does, how it connects with other things (including its reader, its author, its literary and non-literary context)” (p. 199).

Following Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987), non-linear texts are required to create the conditions of possibility for discovering “lines of flight,” as “movements away from sedimented norms and ways of being” (Brooks et al., Citation2018, p. 140). Although an assemblage is multiple and contingent, Buchanan (Citation2015) cautions that it is always “purposeful” rather than simply a happenstance collection of people, materials and actions. The assemblage of my vignettes then becomes “an arrangement of things, dependent on a particular encounter and connection” (Pham et al., Citation2021, p. 3). These vignettic data further provoke me to find a theoretical lens that orient my thinking and understanding (St. Pierre, Citation2019).

While utilizing theories to understand my experience, the subject becomes de-centred and the focus is on what the event does, hence imagining the different positions of the self in a dialogic process (Hermans, Citation2013). By bringing together what some would consider incompatible theories, it is to highlight the significance of epistemological diversity, which disrupts conventional understandings of knowing. As Tesar and Arndt (Citation2020) suggest, “these aspects of abjection as a liminal transformative process are already in flux, in the shifting conceptions that occur through the dislocation of methodologies” (p. 1106). By challenging established notions, this public letter opens up new avenues of inquiry and encourage fresh perspectives, for this kind of “unsettlement” of analytic utterance testifies “to its closeness to, cohabitation with, and ‘knowledge’ of abjection” (Kristeva, Citation1982, p. 30).

*** ***

Socio(logical) imagination and reality

While doing my master’s in New Zealand, socializing with peers was a luxury I couldn’t afford. The lack of interaction further hindered my confidence. Conversations with local students, unfamiliar with Asia, left me feeling awkward and anxious. Our divergent cultural and educational backgrounds meant we had little in common. There appeared to be epistemological differences that separate us, an invisible wall that remains to this day. While my peers were undoubtedly polite, it was difficult for me to discern their genuineness and true interest in getting to know who I really was. More often than not, I felt the weight of judgment based on my origin and background.

Oftentimes, academic scholars offer their sincere suggestion, at the end of their research, such as, international students need to embrace the new environment with openness and confidence, leaving behind any shyness or reservations. Statements as such often leave me dumfounded. Bringing up Kristeva’s theory of abjection that necessitates “the dialectic between an inside and outside” (Henderson, Citation2014, p. 24), we understand that the subject is a speaking body constituted in and through language. Although the speaking body that was present in the discussion should be understood, it is when the speaking subject is not allowed to articulate what they want to say, making them feel alienated within this academic space.

*** ***

My relentless pursuit to become part of your world left me feeling utterly hopeless and emotionally drained.

“There are plenty of pathways …,” you reassured me.

Oh, how enlightening! Thanks for bestowing upon me the wisdom that there are, in fact, ‘plenty’ of pathways. What a revelation!

Then, how come all had led me to the same dead-end? A fate worse than death.* My passion for scholarship and knowledge production seemed a joke to me. I “loathed” myself for being fixated on this dream.

“You had to give it up, moving on with your life, mate!” The-I of the future is calling out to me.

* In Subjects of Desire, Butler (Citation2012) argues that affectivity, “understood as a response to adversity,” is present “as both referential and transfigurative” (pp. 118–147). Quoting Sartre (Citation2014), she elucidates this conceptual position that “emotion is a way of apprehending the world”; emotions are “flights” and “degradations of reality” (pp. 35–52.). In fact, Sartre (Citation2014) bluntly points out that “the hyper-tension of sadness”, that derives from the affected subject, is a result of “lacking the power to undo the nots of the ropes that bind him …” (p. 26).

*** ***

Luck, knowledge, or “mere” coincidence

In 2015, I decided to leave Auckland behind. In the realm of an immigrant life in New Zealand, an accumulation of capital(s)—that proved fruitful—secured me a teaching career in Melbourne, despite my absence from Australian shores. (While the version presented here is simplified, the truth is that the decision process was not straightforward, as I was trying to find a teaching position in California. At the same time, I was also considering returning to my home country, China.)

Working in a government school, I am now amazed by the abundant professional learning opportunities: the costs of attending those conferences and workshops are generously covered by the Department of Education. As a classroom teacher, I am also encouraged to use evidence-based research to inform my own pedagogical practice (Yan, Citation2021a, Citation2022). My nebulous identity (Chinese citizen or Chinese-Australian?) has also become a source of advantage, bestowing upon me rare opportunities in recent years.

It all began when I obtained a permanent residency before becoming an “Australian” teacher. Overnight, I was immediately eligible for The Inclusive Education scholarship, enabling me to do a second master’s in Australia. As Bloemraad (Citation2018) highlights, “citizenship has power” and “through its power of access,” I am granted with certain rights, benefits and resources (pp. 9, 20). However, Riggs (Citation2015) would argue that “almost everything that ever happens is a matter of luck for each of us. Hence, in order for it to be worth mentioning, there must be something significant about the fact that the event being mentioned is out of one’s control (p. 182).

I am (a) local (student) now! With a strong letter of recommendation from my principal, I was finally admitted into The University of Melbourne. I do not even need to pay a cent! Becoming a “local” student, I am now living in a comfortable residence with a learning space, which reminded me of those earlier days as an international student in Auckland where I had to rent a shared shithole and I could smell my flat mate’s stinky socks.

With paid study leave and financial incentives, the rejected “I” has ironically become a high-achieving student with excellent grades (94% on average). However, I remain humble for only I know how much I have traded for this “exclusive” journey on which I am embarking.

***

The “I” of now has the privilege to “unlock” the system: fully comprehend what it means to be “rigorous,” and “competitive.” As Dall’Alba and Barnacle (Citation2015) point out, “when we enact what we know through the body’s entwinement with others and things, we concomitantly embody ways of being-in-the-world” (p. 1460). In this regard, our knowing, acting and being an academic are integrated within the socio-material practice of research. They emphasize that those, who are “learning to become researchers,” will encounter the challenge “of integrating what they know about research, how they act in carrying out research and who they are becoming within the broader community of researchers” (p. 1460).

By recognizing the power of abjection itself, it necessitates the shifting conceptions of the mundane human-I, coming alive differently. In exile, the experience of be(com)ing an academic outsider is “a [stranger’s] experience of becoming noticeable”; such experience propels me to conjecture “how some bodies become understood as the rightful occupants of certain spaces” (Ahmed, Citation2012, pp. 2–3). It awakens the abject to a greater awareness, with a deeper sense of understanding different states of being and, now, I recognize “the growing, interdependent, mutually affecting powers of all that is within the human ‘I’” (Tesar & Arndt, Citation2020, p. 1107).

While studying at a higher institution, I am now able to access “journal articles” that would typically be restricted to me before. I can be a legitimate member of academia! However, I soon realize that by becoming one of you, I will lose my voice again (Yan, Citation2024e).* The dominant discourse seems to depict me as an “immigrant teacher” who requires professional development to improve their cultural understanding and linguistic competence, and classroom management, the list goes on…

* As Poole (Citation2023) states, Asian non-native academic is likely to experience more barriers than their white native-speaking counterpart. I often wonder, when they are denied access to resources and policies are written in “codes,” let alone a sense of being, how can they flourish in their adopted country?

*** ***

The “I” of now wants to tell the “I” of then, “cannot you see you were conditioned for your academic failure? And you wanted to become a high-achieving student?!?” In the search for answers, a profound question arises: what are the chances of ascending as an academic high-achiever when confronted with unfamiliarity with the Western education system, a lack of knowledge regarding its intricate game rules, the weight of financial burdens, and the disorientation caused by divergent socio-cultural norms?. *

* The reader might tell me: “I dislike hearing self-pity. While your journey may indeed be laden with challenges, it is your aspirations, perseverance, and unwavering dedication that enable you to transcend them and rise above.”

Perhaps?!

Echoing Reyes (Citation2022), I claim the “academic outsider” as a site and discourse in/through which to assert an “outsider” as alternative academic identity. In this public letter, my vulnerability lies in feeling like an outsider looking in. Bringing up identity, as Butler (Citation1999) puts it, is “a set of repeated acts, within a highly regulatory frame that congeal over time, produc[ing] the appearance of a substance, of a natural sort of being” (p. 45). Claiming “outsider” as an academic identity, this public letter problematizes and destabilizes normative notions of the academic that are fixated on a rather narrow conception of the academic life, usually focused on the doctoral and post-doctoral experience. As Ruth (Citation2008) critiques, “a substantial part of being an academic is to be a producer and consumer of text (knowledge-as-text), [and] to engage in questions of textual authority” (p. 100). This invites questions of knowledge relative to being an academic, and of the usually accepted norms of becoming an academic.

I have come to realize that PhD is not the only pathway to becoming and producing knowledge in academia, but is it not? And yet, the academic “I” still endures the “stranger’s experience” (Ahmed, Citation2012, p. 3), of compromising, negotiating or internalizing their identity to be socially accepted by the dominant group. By elevating the experience and articulating its signification, the self is engaged in altering the status of the human “I,” however, such an ontological process takes time for the human “I,” connecting with their inner being and sense-making (Tesar & Arndt, Citation2020).

My story of becoming has to be told this way, although I am fully aware of the structure of scholarly discourse. I hope this letter serves as a starting point to talk genuinely about exclusion and selection in the higher education and academia. In agreement with Ahmed (Citation2012), “the act of writing was a [political] reorientation, affecting not simply what I was writing about but what I was thinking and feeling” (p. 2). In writing this letter, I feel empowered to produce situated knowledge(s) that derive from my personal experience. By resisting to become “one of you,” writing about otherness as inquiry has eventually given me a space of convergence for becoming a multivocal self. This emergent identity empowers me to generate invaluable insights while doing research in my own right (Yan, Citation2024f). As Hanisch (Citation1970) once reminded us, “the personal is political” whereby individual experiences can become theoretical (p. 76).

*** ***

Deep down the “I” of now grasps the simple truth: how an individual can be conditioned for their seemingly “success.” And now, I have gained a much better understanding of how the Western system operates (Yan, Citation2024a)! The abject “I” does not say that I no longer experience discrimination and inequity (which will, perhaps, be another story to tell in future). NOW I am more equipped to recognize such adverse situations,* knowing that it is not my fault, but a part of the process of my becomingness that the-now of I must face as the academic outsider. Given necessary resources and proper guidance, “anyone can do it” (Dale, Citation2016, p. 200)!

* Against the backdrop of greater equity and equality, Pilkington (Citation2013) discloses the extent of disadvantage as lived by many marginalized groups. To overcome it, it becomes essential to first recognize systemic issues and signs of marginalization and exclusion, imposed upon them, across different contexts of higher education.

My vignettes may stop here,

And yet, there is no end to one’s becoming.

It is a life-long journey of understanding who I am,

Through abjection, constantly redefining what I can become.

As my journey into becoming continues,

The human “I” needs consistent reflection,

And keeps building strength in dealing with uncertainties.

***

In internalizing my identity(ies) and becomingness, the “I” has been a continuously changing process of relational co-creating and relational (re-)positioning in space and time (Hermans, Citation2001). Through my experience as a foreign student, immigrant teacher, and a rejected doctoral applicant, the abject-I realizes that the formation of their academic identity is hybrid in nature: that of be(com)ing. In a Kristevan sense, the abject-I “works through the struggles and pain,” through which I am able “to connect with inner being and sense-making” (Tesar & Arndt, Citation2020, p. 1106). These elements, and the constancy of abjection as transformation, have then implicated the subject-I abjecting the self from the contextual homogeneity, “between conscious and unconscious, self and other, citizen and foreigner, identity and difference” (Oliver, Citation2002, p. xxvii).

In the process of becoming an outsider, I have undergone the turbulent experiences of a frustrating socio-cultural and educational transition. This echoes Leonardo and Porter (Citation2010) in that abjection is “a symbolic form of violence,” that concerns a dialogue in the academic sphere. In this sense, “[one’s] own anxieties about their own vulnerability are displaced onto those whose positions they fear” (Kenway et al., Citation2006, p. 125). By recognizing “an outsider” as a generative modes of knowledge production, the realization of seeing that there are alternative ways of one’s becoming can be both liberating and empowering—I am not afraid of telling my emotional truth (Yan, Citation2023a).

My becoming of an academic outsider enables me to produce a different kind of knowledge, concerning “how some and not others become strangers”—the politics of stranger-making (Ahmed, Citation2012, p. 2). I have now understood, what Ahmed (Citation2006) meant, “how the [body] can extend themselves into spaces,” “creating contours of inhabitable space,” and how such spaces can be “extensions of bodies,” but most frustratingly, “some spaces extend certain bodies and simply do not leave room for [the] Others” (p. 11). In unpacking the entanglements in such becomingness, this public letter broadens Brooks et al.’s (Citation2018) critique on the norms and mechanisms of doctoral study, privileging certain bodies and ways of being and excluding the other.

This public letter expresses my inner experience and the desire of being heard of what the human “I” might contribute to the discourse in the cultural politics of education. Now I have gone from a naïve, idealistic master’s student, following the conventional rules of writing, to an immigrant scholar who advocates social justice and equity and embraces my unique way of speaking, writing and thinking. So, I wonder, how far I am allowed to confront the academic conventions and “policing” when examining my own becoming of an outsider and expressing my emotional truth?

I hope this public letter encourages minority groups of people to engage in knowledge production of articulating their reality. You need to write your stories on your own terms, even if it means constant desk rejection and multiple rounds of revision (and despair). This work is written for you—the “I” of then.

P.S. In 2022, I was admitted into a PhD program in one of the world’s top-50 universities (and awarded with two types of scholarships that recognize so-called high-achieving students). Lucky me?!

Sincerely,

An academic

Outsider

Acknowledgements

As an/Other, the first author “I” appreciates the co-author’s willingness to take a back seat role. We worked together on this work, the process of which is about empowering the “I” to take ownership of its own story. We contend that who tells the marginalized story matters. And yet, a published work does not always belong to “I” or “us”; it reflects various aspects of invisible input, including feedback from numerous reviewers/editors who rejected and/supported this significant piece of work. The two of us, there was “already quite a crowd,” as Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) reminded us, “To reach, not the point where one no longer says ‘I,’ but the point where it is no longer of any importance whether one says ‘I’. We are no longer ourselves. Each will know his own. We have been aided, inspired, multiplied” (p. 3).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dave Yan

Dave Yan is an ordinary individual who dares to dream the impossible, “no matter how hopeless, no matter how far to reach,” and “to bear with unbearable sorrow” even if this road is full of hurdles (Leigh & Darion, Citation1965). As a rejected doctoral applicant, he holds a deep appreciation for the city libraries in Auckland and Melbourne, which provided him access to literary works when he couldn’t access scholarly journals. Drawing upon his lived experience as an immigrant, he has gradually formed a unique style of theorizing and scholarship in the production of minor literature.

Adam Poole

Adam Poole is currently an assistant professor in the Department of Education Policy and Leadership, Education University of Hong Kong. His research interests include the internationalization of private secondary education, professional development for English teachers, and social justice methodologies (including the funds of identity and funds of knowledge approaches).

Notes

1 Despite a plethora of studies exploring equality in the higher education, much research has focused on the career experiences for minority doctoral students (e.g. Arday, Citation2021; Mattocks & Briscoe-Palmer, Citation2016). What is less reported are the lived experiences in access to different types of universities and degree attainment and their pursuit of doctoral studies more specifically, and how such experiences contribute to their becoming of an academic outsider.

2 This prose poetry is inspired by Pirsig (Citation1999, p. 168). Throughout this paper, poetic writing serves a means of inquiry, allowing me to express my inner experience about my being across time and space. As Gibson (Citation2016) argues, poetry defies making ambitious claims of any sort, because it is a philosophical language “that often strive[s] to unburden language of its usual representational and sense-producing responsibilities” (p. 131).

3 One of the strengths of autoethnographic inquiry is that it can be used with a variety of theoretical and methodological lenses. As Ellis and Bochner (Citation2000) argue, there is no canonical way of doing autoethnography. Autoethnographic research is about writing evocative narratives as socially-just acts (Holman Jones et al., Citation2016), allowing the reader to “experience” the feelings and perceptions of living with the diverse human experience, of similarity and difference. In doing so, we bring together autoethnographic and critical standpoints, for the examination of interpersonal and cultural experiences of identity from the inside out (Boylorn & Orbe, Citation2020). However, a potential limitation of autoethnography is the critique that it is insufficiently theoretical. The issue of achieving a balance between evocation and connection with theories has been a concern in writing ‘conventional’ works. As Learmonth and Humphreys (Citation2012) caution, emphasizing theoretical analysis might risk losing the evocative power of autoethnography. To present my emotional truth and amplify my growing voice, I have chosen to create a layered account, through re-reading and re-writing, which is then fed back into the emerging narrative which you are reading now.

4 The lyrics of the song were written by Birgisson and Wroldsen (Citation2010).

References

- Ahmad, A. (2017). Living a feminist life. Duke University Press.

- Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer phenomenology: Orientations, objects, others. Duke University Press.

- Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

- Arday, J. (2021). Fighting the tide: Understanding the difficulties facing Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) doctoral students’ pursuing a career in academia. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(10), 972–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1777640

- Bakhtin, M. M. (2010). The dialogic imagination: Four essays (C. Emerson & M. Holquist). University of Texas Press. (Original work published 1981)

- Barad, K. (2010). Quantum entanglements and hauntological relations of inheritance: Dis/continuities, spacetime enfoldings, and justice-to-come. Derrida Today, 3(2), 240–268. https://doi.org/10.3366/drt.2010.0206

- Birgisson, A., & Wroldsen, I. (2010). Impossible [Recorded by Shontelle]. On No gravity. SRC.

- Bloemraad, I. (2018). Theorising the power of citizenship as claims-making. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(1), 4–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1396108

- Blumer, H. (2017). What is wrong with social theory? In N. K. Denzin (Eds.), Sociological methods (pp. 84–96). Routledge. (Original work published 1970)

- Boylorn, R. M., & Orbe, M. P. (Eds.). (2020). Critical autoethnography: Intersecting cultural identities in everyday life. Routledge.

- Brooks, S., Franklin-Phipps, A., & Rath, C. (2018). Resistance and invention: Becoming academic, remaining other. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 31(2), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1349956

- Buchanan, I. (2015). Assemblage theory and its discontents. Deleuze Studies, 9(3), 382–392. https://doi.org/10.3366/dls.2015.0193

- Burford, J. (2017). Not writing, and giving ‘zero-f**ks’ about it: Queer(y)ing doctoral ‘failure’. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 38(4), 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1105788

- Butler, J. (1999). Gender trouble. Routledge.

- Butler, J. (2012). Subjects of desire: Hegelian reflections in twentieth-century France. Columbia University Press. (Original work published 1987)

- Dale, P. (2016). Anyone can do it: Empowerment, tradition and the punk underground. Routledge.

- Dall’Alba, G., & Barnacle, R. (2015). Exploring knowing/being through discordant professional practice. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(13–14), 1452–1464. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2014.947562

- Deleuze, D., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus (B. Massumi, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press.

- Denzin, N. K. (2018). Performance autoethnography: Critical pedagogy and the politics of culture. Routledge.

- Derrida, J. (2016). Of grammatology (G. C. Spivak, Trans.). Johns Hopkins University Press. (Original work published 1967)

- Ellis, C., & Bochner, A. P. (2000). Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 733–768). SAGE.

- Farman, A. (2017). Terminality. Social Text, 35(2), 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3820569

- Faulkner, S. L. (2016). Poetry as method: Reporting research through verse. Routledge.

- Foucault, M. (2012). The history of sexuality, Vol. 3: The care of the self (R. Hurley, Trans.). Vintage. (Original work published 1988)

- Fournier, L. (2021). Autotheory as feminist practice in art, writing, and criticism. MIT Press.

- Frank, A. W. (2013). The wounded storyteller: Body, illness, and ethics. University of Chicago Press.

- Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). Continuum. (Original work published 1970)

- Gibson, J. (2016). What makes a poem philosophical? In M. LeMahieu & K. Zumhagen-Yekplé (Eds.), Wittgenstein and modernism (pp. 130–150). University of Chicago Press.

- Grosz, E. (1994). A thousand tiny sexes: Feminism and rhizomatics. In C. V. Boundas & D. Olkowski (Eds.), Gilles Deleuze and the theatre of philosophy (pp. 187–210). Routledge.

- Hanisch, C. (1970). The personal is political. In S. Firestone & A. Koedt (Eds.), Notes from the second year: Women’s liberation—Major writing of the radical feminists (pp. 76–78). Radical Feminism. https://webhome.cs.uvic.ca/∼mserra/AttachedFiles/PersonalPolitical.pdf

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

- Henderson, E. F. (2014). Bringing up gender: Academic abjection? Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 22(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2013.877202

- Hermans, H. J. (2003). The construction and reconstruction of a dialogical self. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 16(2), 89–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720530390117902

- Hermans, H. J. (2001). The dialogical self: Toward a theory of personal and cultural positioning. Culture & Psychology, 7(3), 243–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X0173001

- Hermans, H. J. (2013). The dialogical self in education: Introduction. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 26(2), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2013.759018

- Hermans, H. J., Kempen, H. J., & Van Loon, R. J. (1992). The dialogical self: Beyond individualism and rationalism. American Psychologist, 47(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.1.23

- Herrmann, A. F. (2012). “I know I’m unlovable”: Desperation, dislocation, despair, and discourse on the academic job hunt. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(3), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411431561

- Holman. Jones, S., Adams, T. E., & Ellis, C. (2016). Coming to know autoethnography as more than a method. In T. E. Adams, S. Holman Jones, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp. 17–48). Routledge.

- Humphreys, M. (2005). Getting personal: Reflexivity and autoethnographic vignettes. Qualitative Inquiry, 11(6), 840–860. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800404269425

- Jackson, A. Y., & Mazzei, L. (2011). Thinking with theory in qualitative research: Viewing data across multiple perspectives. Routledge.

- Kenway, J., Kraack, A., & Hickey-Moody, A. C. (2006). Masculinity beyond the metropolis. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Koh, A. (2012). ‘In-between’ Asia and Australia: On the politics of teaching English as the Other. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 33(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2012.666073

- Kristeva, J. (1982). Powers of horror: An essay on abjection (L. S. Roudiez, Trans). Columbia University Press.

- Kristeva, J. (1991). Strangers to ourselves. (L. S. Roudiez, Trans). Columbia University Press.

- Learmonth, M., & Humphreys, M. (2012). Autoethnography and academic identity: Glimpsing business school doppelgängers. Organization, 19(1), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508411398056

- Leigh, M., & Darion, J. (1965). The impossible dream (The Quest) [Song]. On Man of La Mancha [Broadway musical]. Columbia 30th Street Studio.

- Leonardo, Z., & Porter, R. K. (2010). Pedagogy of fear: Toward a Fanonian theory of ‘safety’ in race dialogue. Race Ethnicity and Education, 13(2), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2010.482898

- Manson, M. (2016). The subtle art of not giving a f*ck: A counterintuitive approach to living a good life. HarperCollins.

- Mattocks, K., & Briscoe-Palmer, S. (2016). Diversity, inclusion, and doctoral study: Challenges facing minority PhD students in the United Kingdom. European Political Science, 15(4), 476–492. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-016-0071-x

- McLuhan, M. (2001). Understanding media: The extensions of man. Routledge. (Original work published 1964)

- Michel, R. S., Belur, V., Naemi, B., & Kell, H. J. (2019). Graduate admissions practices: A targeted review of the literature. ETS Research Report Series, 2019(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12271

- Moreira, C., & Diversi, M. (2010). When janitors dare to become scholars: A betweeners’ view of the politics of knowledge production from decolonizing street-corners. International Review of Qualitative Research, 2(4), 457–474. https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2010.2.4.457

- Morley, L. (2021). Does class still matter? Conversations about power, privilege and persistent inequalities in higher education. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 42(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1855565

- Morson, G. S., & Emerson, C. (1990). Mikhail Bakhtin: Creation of a prosaics. Stanford University Press.

- Oliver, K. (Ed.). (2002). The portable Kristeva. Columbia University Press.

- Pham, X., Bright, D., Leahy, D., & Welch, R. (2021). Categorical difference as affective assemblage: experiences of Vietnamese women in the neoliberal university. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(5), 1679–1692. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1902948

- Pilkington, A. (2013). The interacting dynamics of institutional racism in higher education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 16(2), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2011.646255

- Pirsig, R. M. (1999). Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance: An inquiry into values. Random House.

- Poole, A. (2022). Examining “precarious privilege” in international schooling: White male teachers negotiating contract non-renewal. Educational Review. Advance online publicaiton. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2022.2106190

- Poole, A. (2023). From recalcitrance to rapprochement: Tinkering with a working-class academic bricolage of ‘critical empathy’. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 44(4), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2021.2021860

- Rambo, C. (2005). Impressions of grandmother: An autoethnographic portrait. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 34(5), 560–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241605279079

- Reyes, V. (2022). Academic outsider: Stories of exclusion and hope. Stanford University Press.

- Richardson, L., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2005). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 959–978). Sage.

- Riggs, W. D. (2015). Luck, knowledge, and “mere” coincidence. In D. Pritchard & L. J. Whittington (Eds.), The philosophy of luck (pp. 177–189). Wiley.

- Robertson, S. (2011). Cash cows, backdoor migrants, or activist citizens? International students, citizenship, and rights in Australia. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(12), 2192–2211. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.558590

- Ronai, C. R. (1992). The reflexive self through narrative: A night in the life of an erotic dancer/researcher. In Ellis, C., Flaherty, M. (Eds.), Investigating subjectivity: Research on lived experience (pp. 102–124).

- Ronai, C. R. (1995). Multiple reflections of child sex abuse: An argument for a layered account. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 23(4), 395–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124195023004001

- Ruth, D. (2008). Being an academic: Authorship, authenticity and authority. London Review of Education, 6(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/14748460802184998

- Sartre, J.-P. (2014). Sketch for a theory of the emotions (P. Mairet, Trans.) Routledge. (Original work published 1939)

- Smith, A. (1996). Julia Kristeva: Readings of exile and estrangement. Macmillan.

- St. Pierre, E. A. (2019). Post qualitative inquiry in an ontology of immanence. Qualitative Inquiry, 25(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418772634

- Tavares, V. (2021). Feeling excluded: International students experience equity, diversity and inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.2008536