Abstract

This article considers what critical community building might look like among colleagues at a university representing one faculty member, one doctoral candidate, and one undergraduate student. Using critical autoethnography-self-study, we analyze our journal reflections, presentations, teaching, and dialogues to better understand our approaches with teaching Critical Race Theory. This research asks: How do colleagues across power dynamics and positionalities learn from each other, and work collaboratively to teach about race and racism at a predominantly white institution? Our findings indicate that this sort of work requires relationships, shared vulnerability, and an understanding of our journeys to becoming critical pedagogues. We find value in this work due to its focus on collaboration across power dynamics (i.e. rank of professor, graduate, and undergraduate students) as well as our positionalities across womanhood. We offer implications for other faculty/instructors who wish to bring this sort of collaboration to their college classroom and teacher education.

Introduction

Late into 2020, the 45th President signed an executive order to remove Critical Race Theory (CRT) and white privilege training (or training of the like) from all federal agencies (Executive order September 4, 2020). He then followed this signing with a speech made at the White House Conference on American History,Footnote1 where he exclaimed that this “radical movement” (referring to CRT) is meant to intentionally fracture America and to promote a culture of exclusion of those who do not comply with this “tyranny.” Furthermore, he provided an inaccurate representation of CRT, using incomplete examples and inflammatory language to support his argument and invoke anger by the audience. Lastly, he declared that American teachers and schools were indoctrinating students into this “prejudiced ideology” by “[feeding students] hateful lies about this country” making the students shameful of their country and American values. The 45th president proclaimed that a “patriotic education” must be taught to students, where the curriculum is “pro-American,” meaning events and topics that discredit American values are left out of the conversations in educational institutions.

Four months after this speech the 45th President invited and prompted the administration’s followers to attack United States (U.S.) democracy. The mostly white followers became violent as they invaded, vandalized, and destroyed the U.S. Capitol during the certification of President-Elect Joe Biden. These insurrectionists were not met with officers in riot gear, tear gas, or a shower of rubber bullets. A stark difference was seen between the treatment of this group and the peaceful protesters of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in the summer of 2020. Most BLM protesters were non-violent and were acting within their legal rights, however they were still met with aggression and violence from law enforcement. Although upsetting, these differences are anything but surprising. The U.S. has not owned up to or dealt with its past and present practices of racial injustice, therefore there is repetition of oppression and violence against Black and Indigenous and other People of Color (BIPOC). This is evidenced in recent history with some notable white nationalist and extremist groups targeting non-white communities: Charleston church shooting in 2015, white nationalist Charlottesville protests in 2017, Pittsburgh synagogue shooting in 2018, Trump administration family separation policies in 2018, El Paso shooting in 2019, and the Atlanta spa shooting in 2021.

In his first day of office, the Biden Administration overturned the previous executive order on January 20, 2021 and signed a new order titled, “Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government.” While this executive order seemingly was intended to do the exact opposite of what Trump’s has proposed, the damage had already been done, and the seeds were planted to eliminate any perceived CRT or “diversity” training. Education, typically seen as a “State’s issue,” suddenly was in the public eye regarding the teaching of CRT in schools. At the time of this writing, 42 states have introduced bills that restrict teaching of CRT and/or how teachers can discuss issues of racism or sexism. Seventeen states have already enacted these bills (Education Week, 2022). This is obviously alarming to us as educators committed to racial justice and teaching CRT frameworks in classrooms that prepare future educators to navigate our increasingly diverse society.

Before the January 6 Capital attack and executive orders, tensions had already been on the rise in U.S., especially with Trump’s emboldment of white supremacists (i.e. Charlottesville), and reinciting racism as “okay” (Matias & Newlove, Citation2017). Given this context, the central organizing theme behind this project began with thinking about racial justice, and in particular, what it looks like to teach the predominantly white students (that represent our former university) about race, racism, and whiteness, at a time when there is so much division. We specifically use Critical Race Theory (CRT) as one of our frameworks guiding our teaching pedagogy. CRT extends beyond a race-intentional approach that challenges race and racism as topics to engage with, around dismantling the power hierarchies that support racism and white supremacy. In teacher education, this means going beyond broad discussions of diversity and multiculturalism to specifically address how white supremacy manifests in educational contexts.

We came together in this work ultimately to develop a critical community amongst ourselves as instructors to who teach about CRT on college campuses. We refer to this work as “critical” community building because the “community” we have built with one another is critical in nature. We’ve undergone critical self-reflection of our own positionalities, and interrogated larger power structures that operate within our institutions in order to create this “community” (a professor and students who are colleagues). Brittany is the faculty member who possesses institutional power in many ways (she’s faculty), and less power in other ways (at the time of the research collection she was untenured). She identifies as white passing cis-Latina (Colombian)/multiracial/biracial/Hispanic. She has benefited from a light-skinned privilege much of her life, and continues in most settings due to this system of white supremacy we live in. However, while she is racially white, she is also Latina with ethnic and heritage roots that tell a different story about her than most of her students at her former institution in the Midwest. Dominique is a doctoral graduate (completed her PhD) who identifies as a fat Black cis woman. As an instructor teaching about race, these visible markers of identity make navigating a predominantly white student body a complicated dance. Her teaching practice is modeled on dialogic critical pedagogy in the footsteps of Paulo Freire and bell hooks. However, the complex racial power dynamics mean she must balance maintaining a sense of authority with pedagogy rooted in mutual respect for students’ knowledges. Her positionality is complicated by these interconnected dynamics of power over, and power with, her students. Lastly, Jazmin is an undergraduate student completing a degree in education studies. She identifies as a lower-middle-class, queer, disabled white woman. She believes her lived-learned experiences dealing with “real-world” problems allow for her to understand and conceptualize difficult topics surrounding society and education. Although her class status can and has impacted her access to education, she understands the importance of education within and outside of the classroom. Often she reflects on how interlocking social systems of oppression play a role in all aspects of her life. This reflection allows for real examples when teaching others about the connection between oppression, education, and society.

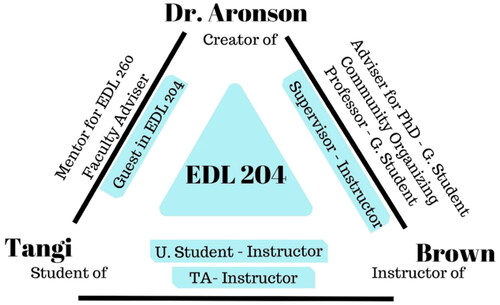

Brittany created and was the coordinator of a required social foundations course for pre-service teachers, titled EDL 204 Sociocultural Studies in Education. She worked closely with several doctoral students who teach this course using an apprenticeship model in learning how to teach critical content related to racism and whiteness. Dominique also previously taught the course. Jazmin is a former undergraduate students who was previously a student of EDL 204 in Fall 2018, and then a teaching assistant (TA) with Dominique for EDL 204 in Spring 2019. Additionally, Jazmin was a part of an undergraduate research class who was paired with Brittany as her faculty mentor. We are hence connected to each other through our teaching and research. We did not write this paper under the guise that we were experts in how to do this type of work, but rather we feel that the critical community we created and how we worked together across power dynamics is one of the ways that we can resist the restrictive nature of the academy. See for a visual depiction of our relationship.

In this article, we seek to consider what critical community building might look like amongst colleagues when coming together to teach in environments skeptical of and openly hostile to CRT. In this autoethnographic study, our guiding research question asked: How do colleagues across power dynamics and positionalities learn from each other, and work collaboratively to teach about race and racism at a predominantly white institution?

As part of our goal to understand our own critical community building, this research stems from a ‘critical’ collaborative self-study (Han et al., Citation2017) in a teacher education program over the course of 2 years. Our informal conversations lead to a conference proposal submission serving as the impetus to formally collect data on ourselves. Importantly, to better understand where we fit in the broader research community, we begin with an overview of the literature that helped us inform our approach to teaching about race at PWIs. From there, we connect our understandings from the literature to the context of this research: the course that brought us all together. Both the course and the analysis of our self-study is guided through the lens of critical pedagogy CRT which we explore interconnectedly. Next, we share our methodological marriage between collaborative autoethnography (Chang et al., Citation2013; Hughes & Pennington, Citation2017) and self-study in teacher education (LaBoskey, Citation2004; Samaras, Citation2002) and unpack our methods of data collection and analysis. Finally, we present our findings from this project and conclude with implications for teacher education and higher education spaces to continue in their journey for racial justice.

Literature review

Archer et al., (Citation2016) argues that higher education has continued to teach the same oppressive and limiting ideologies in college classrooms. An in-depth two-year study done between 2010-2012 focusing on the attitudes of white students towards their peers of color concluded: “that existing pedagogy has done little to challenge the raced, classed and gendered stereotypes, antagonisms, and behaviors that are displayed by White middle-class students within this higher education setting” (p. 50). As indicated from our introduction, it is obvious that racial injustice is ever more pervasive, and the ideology of white domination and privilege is continually passed onto the next generation. It is distressing to consider what could happen if widespread change and healing do not occur, but as current events unfold it is predicted to lead to more violence and chaos. We argue there is power in having inter-cultural/racial dialogue that disrupts power dynamics, not just amongst ourselves as instructors, but with students in the classroom as well. For example, Damrow and Sweeney (Citation2019) engaged in a study conducted with two higher education classes for preservice and in-service teachers, one being predominantly white and the other predominantly racially and ethnically diverse. The students were grouped across the two classes and participated in facilitated, peer-to-peer, and group conversations for ten months. The conversations ranged from interview style to relationship building dialogue. In the analysis of the dialogue and reflections of the student, the authors discovered that the “participants taught one another in ways [the professors] could not. Creating spaces where respectful dialogue could take place, provided an opportunity for knowing both self and ‘others’ more deeply and avoiding the danger of the single story” (p. 263). The authors suggest that students who interact in intimate and raw conversations with people of different identities, experiences, and ideologies allow all participants to develop empathy for others. Intentional community interaction and development of specifically white students and students of color is a tool to prompt empathy building for those who are learning about systemic racism, and/or have not experienced the impact of oppression firsthand. In addition to racially diverse communities, Case (Citation2012) argued that creating a space for white people to reflect on their biases is beneficial in their development and growth toward antiracism. This provides such an opportunity to work towards racial justice as they share their growing pains and revelations during their journey (Case, Citation2012; Fine, Citation1997; Jackson, Citation1999). In doing so this takes the burden off of people of color to teach, support, and be accountable for the growth of white people. We believe creating both types of spaces are important in teaching about racism in college classrooms.

In addition to this type of work seen with students in classrooms, we believe that thinking through cross-racial/power collaborations as instructors is also important to model critical community building and antiracist coalition building. In one example, Morales Morales et al. (Citation2020) research formed a Critical Education Research Collective (CERC) as space to engage in conversations about meaningful teaching, research, and inquiry. Similar to our work, the CERC focused on “cultivating critical pedagogy in the teacher education classroom” (p. 2). In agreement with the authors:

We suggest that critical pedagogy happens in the intersections of roles and

relationships. In our case it was the space where faculty, doctoral students, and student

teachers interacted and learned together. The space helped us reconsider how teaching and learning are traditionally thought of and moved us to think of teaching and learning as done with students, not to or for them. Our work started with re-imagining our relationships and roles. (p. 17)

Furthermore, research has indicated how intergroup dialogue (IGD) can aid in facilitating conversations related to identity, racism, oppression and more in higher education (Buckley & Quaye, Citation2016; Keehn, Citation2015). For example, French et al., (Citation2022) conducted a literature review of IGD showcasing its effectiveness, specifically in higher education settings. They explain, “educators and scholars can implement IGD in adult education settings as part of ongoing efforts to engage individuals from oppressed social groups in emancipatory processes while exploring how privileged groups can support oppressed groups in everyday life” (p. 45). While our triad did not specifically apply an explicit IGD strategy within our teaching, we mimic similar aspects from IGD such as engaging in relationship building at the start of class, doing a deep dive into our social identities, examining systems of systemic oppression, and promoting conversation across differences throughout the teaching experience.

A praxis theoretical framework: critical pedagogy & critical race theory

Critical pedagogy (CP) and Critical Race Theory (CRT) ground this research study and played an integral role in the course material we all taught. This research integrates the personal and the political. As educators and as people we came together in a supportive community so that we might be able to navigate the contextual complexities that inform our CP/CRT teaching praxis. In this paper, as in the course, we lean into CP/CRT to provide foundational understanding of the social locations we hold as instructors in relationship to the students we teach. Sensoy and DiAngelo (Citation2017) define Critical Theory as a “scholarly approach that analyzes social conditions within their historical, cultural, and ideological contexts.” We approach teaching with this framing in mind. The knowledge exchange between teacher and student, the educator and those being educated, is not a neutral act. All participants are situated in the socio-cultural contexts that we each bring into the classroom. Each of us processes and makes meaning of experiences from those contexts (Sensoy & DiAngelo, Citation2017). As critical scholars and educators we guide students to “challenge ideological domination…[and] examination of students’ own social positions and the relationship between those positions” (Sensoy & DiAngelo, Citation2017, p. 29) that they bring into the classroom.

It is evident that racial identity plays an important role in how we as instructors are perceived, contextualized, and responded to by students in the course. The CRT ‘′movement is a collection of activists and scholars engaged in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power” (Delgado & Stefanic, Citation2023, p. 3). CRT offers a theoretical framework for both teaching about race and racism, as well as understanding our racialized positionalities. In Toward a Critical Race Theory of Education Gloria Ladson-Billings re-asserts that “racism is not a series of isolated acts, but is endemic in American life, deeply ingrained legally, culturally, and even psychologically” (Delgado, as cited in Ladson-Billings & Tate, Citation1995, p. 52). The social construction of race continues to be fertile ground for pedagogical exploration.

EDL 204 is a critical pedagogy course theoretically informed through a critical social justice lens which “recognize[s] that society is stratified (i.e. divided and unequal) in significant and far-reaching ways along social group lines that include race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability. Critical theories recognize inequality as deeply embedded in the fabric of society (i.e. as structural), and actively seek to change this’’ (Sensoy & DiAngelo, Citation2017, p. xx). As a collective teaching and learning through EDL 204, we rely heavily on CP and CRT as theoretical frames. The course uses texts from authors like Peter McLaren (Citation2002), Paulo Freire (Citation1998), and bell hooks (Citation1994), among many others to ground students’ understanding of broader socio-cultural issues affecting the education system in the U.S. In the spirit of Freire’s work, teaching and learning is cultivated as a fluid practice between students and instructors learning from, with, and through each other. The idea is that instructors can create an environment where they facilitate learning for the students and themselves. In short, creating a community of learning together where all stakeholders have a voice and can make contributions to shared growth. This is how we understand our shared praxis as critical pedagogues and how we integrated theory and practice into our teaching EDL 204 and our analysis as practitioner scholars.

The course: EDL 204

Theory guides our teaching, practice, and data analysis. EDL 204 brought us together as a faculty member, doctoral and undergraduate student. In 2018, EDL 204 was a required course for Teacher Education majors and an liberal arts elective option for all other majors. This course challenges how education has been understood and constructed through history with a goal to connect the past to the present. We spend roughly four to five weeks of the semester unpacking the history of race and ethnicity including understanding whiteness as a construct. There are several intentions behind this: 1) to understand that while race is a social construction, there are real consequences to the racialization in the world (Omi & Winant, Citation2014); 2) studying race moves beyond only understanding that racism exists- thus we study the history of racialized pasts from different minoritized groups including but not limited to African Americans, Indigenous peoples, Latinx and Asian American communities; and 3) whiteness was created to justify domination, so thus when studying ‘white people’ we study power and privilege. We emphasize that we also need to study systems of white supremacy for white people to become co-conspirators (Love, Citation2019) in working against systems of oppression.

However, it is not without challenge, our university is a predominantly white institution (PWI) located in the rural Midwest, with a mostly white faculty and economically affluent student body. Teaching CP/CRT in this context with the intention of creating a learning environment that is dialectical in nature presents both ethical and intellectual constraints. As instructors it is our job to facilitate a learning environment that fosters the “practice of critical teaching, implicit in a correct way of thinking involves a dynamic and dialectical movement between ‘doing’ and ‘reflection on doing” (Freire, Citation1998, p. 43). Students are asked to complete assignments that require them to reflect deeply on their own socio-cultural educational context using the course content as a guide. In these assignments many students report that this is the first time they have taken a step back to articulate their social location in an educational environment within a broader community context. It is from this shared experience that the three of us have begun to learn from each other how we might deeply consider our own positionalities when entering the classroom. McLaren’s (Citation2002) description of a critical educator provides useful in this endeavor:

The critical educator endorses theories that are, first and foremost, dialectical; that is

theories which recognize the problems of society as more than simply isolated events of

individuals or deficiencies in the social structure. Rather, these problems form part of

the interactive context between individual and society. The individual, a social actor,

both creates and is created by the social universe of which he/she is part. Neither the

individual nor society is given priority in analysis; the two are inextricably interwoven,

so that reference to one must by implication mean reference to the other. (p. 56)

Additionally, in EDL 204 we spend a significant portion of the course material exploring CRT and the social construction of race as it impacts the U.S. education system (Zamudio et al., Citation2011). Underneath the CRT umbrella the course explores concepts of racialization through the historical context of school segregation policies. Not only the moment of supposed desegregation brought on by the famous “Brown v. Board of Education” Topeka, Kansas case, but also the social impacts of the Black teaching force who lost position and influence in the broader public education system (Ladson-Billings, Citation2004). We invite students to explore the lesser known 1947 Mendez case which ushered in desegregation for Mexican American students in California (Moon, Citation2018), the intersection of race and disability (Annamma et al., Citation2013), the problematic nature of the “model minority stereotype” facing Asian Americans (AJ+, Citation2017), the construction of whiteness (DiAngelo, Citation2018), and Indian boarding schools (Lomawaima & McCarty, Citation2006). Essentially, we enter a lot of fraught ground for students and instructors to wrestle over together and what served as the impetus for our relationship.

The learning environment cultivated within the positionalities of the instructors and students, as well as the shared physical location with its own socio-cultural, political, historical, and economic contextualization generated a complex landscape to navigate. According to P. R. Camangian et al. (Citation2023) CRT invites us to “build community among those at the margins of society…challenge the perceived wisdom of those at societies center…and demonstrate that [we] are not alone in [our] position” (p. 58). As educators pursuing critical pedagogy together we shared a tenuous path, requiring investment in deep learning across our different experiences to articulate our unique stories.

Methodology

This collaborative research project borrows from the methodologies of collaborative autoethnography (Chang et al., Citation2013; Hughes & Pennington, Citation2017) and self-study in teacher education (LaBoskey, Citation2004; Samaras, Citation2002) to create a ‘critical’ collaborative self-study (Han et al., Citation2017). When meeting to discuss what our overarching methodology should be to guide our study, we found ourselves at a loss when examining the literature on “autoethnography” and “self-study.” We felt both methodologies had something to offer in terms of what we were seeking to do. Autoethnography is useful in considering what we wish to learn about our identities in relation to power, privilege, and oppression; and self-study helps us in studying our teaching practices. The main differences lie in these methods’ disciplinary roots but share a common goal of how we understand ourselves in relation to society (Hughes & Pennington, Citation2017). Thus, rather than silo these equally advantageous research methodologies, we decided to marry the two pulling from them the tenets most helpful in conducting this research project.

Autoethnography importantly looks at the self in relation to the larger context. Ellis (Citation2004) explains that autoethnography involves personal writing in relation to culture. Chang et al., (Citation2013) define collaborative autoethnography as a “qualitative research method that is simultaneously collaborative, autobiographical, and ethnographic” (p. 17). They explain autoethnography is itself a blending of ethnography – study of cultural groups over time, with biography– a study of self, and that they are adding the additional dimension- collaboration. As shared above, our research began in 2018 when our connection to one another was unveiled. From that point, we intentionally began journaling and reflecting upon our experiences teaching EDL 204, particularly in regards to how we taught about race.

Self-Study methodology comes out of a teacher education tradition. In general, a large part of the curriculum in teacher education is to teach reflexivity- that is being mindful and thoughtful of your teaching practices. It makes sense then that teacher educators would follow a similar path in their own pedagogy. Samaras (Citation2002) shares with her own experience in mind that self-study is “a difficult yet emancipating process … telling my own story helps me understand my own teaching better” (p. 5). The idea behind using stories is not meant to be a narcissistic practice, but rather to reveal to future teachers reflexivity and help them “understand how their early life lessons shaped their teaching and their perspectives about students who are not like them” (Samaras, Citation2002, p. 5). “LaBoskey (Citation2004) outlines five elements of self-study: it is self-initiated and focused; it is improvement-aimed; it is interactive; it includes multiple, mainly qualitative, methods; and it defines validity as a process based on trustworthiness” (Hamilton et al., Citation2008, p. 21). Our research project fits well within self-study due to its focus on how we teach about race to future teachers with a goal to improve our practice (and contribute to the field as a whole to improve practice). It is certainly interactive as we are constantly engaging in reflection with one another and our colleagues writ large. Finally, we situate this work as valid and have established trustworthiness by sharing and reflecting on our preliminary data at the American Educational Studies Association (AESA) conference. More on this below.We are also theorizing this work around our positionalities. These include both our social identities as well as positions of power. Importantly, in our marriage of these two methodologies, we’d like to note the importance of a critical orientation in the work that we are engaging with. As CP/CRT scholars, not only is our teaching pedagogy guiding through CP/CRT, but also this is the lens we take on as we analyze our data and consider the implications of our findings.

Methods

Autoethnographic methods of data collection frequently use methods such as reflection journaling, videotaping, interviews, and fieldwork (Hughes & Pennington, Citation2017). For this research project, there are three main points of data collection: 1) personal narrative reflections from a written prompt, 2) video-recording of our preliminary analysis of data at the AESA conference in Fall 2019, and 3) video-recording of a teaching lesson we collaboratively planned and implemented in November 2019. The prompt we each responded to for data point #1 asked us to share stories related to our understanding, challenges, and key moments we’ve had when teaching and learning about race.

In addition to these three material points of data collected, we have many informal points of data that are informing us including numerous conversations face-to-face over coffee or dinner, via texting with each other, or through email exchange. Brittany also co-taught a lesson with Dominique when Jazmin was a student on the ‘white savior industrial complex’ . Jazmin has also been a guest in both of our classes and served as a mentor to a new group of faculty advisees working with Brittany. We continue to reflect upon all of these important moments that contribute to our collective analysis.

Data analysis

From the moment we began collecting and organizing our data, we already were in a process of analysis. “Autoethnographers (Lapadat, Citation2009; Muncey, Citation2010) would argue that data analysis begins with memory work; when you select memories, you examine, evaluate, and analyze them as you decide which ones fit with your autoethnographic exploration” (Chang et al., Citation2013, p. 95). We have already applied analytics through the first point of data collected by selecting what to tell as we were writing our stories (Ellis, Citation2004).

During each stage of our data collection, we gathered to discuss what stood out to us in each of these examples. We asked questions about where we saw our experience converge and where we saw them diverge. For our first stage, data analysis began when we each read each other’s stories and probed each other asking more questions. This led us to come up with two preliminary themes from our data: 1) the shared responsibility we feel is necessary in teaching about race, and 2) how there is a process and journey for learning to do racial justice work. As Chang et al., (Citation2013), “the point here is to think of data collection-analysis-interpretation as iterative rather than linear processes” (p. 100). After presenting these preliminary findings at AESA and debriefing on the presentation, we planned a collaborative teaching lesson keeping in mind our findings.

In our final state of data analysis, we each independently watched our conference presentation and collaborative teaching lesson. Following in line with Chang et al., (Citation2013) approach for analyzing the repertoire of data we collected, we began by 1) reviewing the data, 2) segmenting, categorizing, and regrouping the data, and 3) finding themes and reconnecting the data (pp. 102-109). Upon reviewing the data, we each took notes to get a holistic sense of what we noticed. Here we constructed a preliminary list of topics emerging from watching the videos (similar to initial codes). We then met to discuss our interpretations of our reactions and how we related to one another. This allowed us to share our different perspectives and dialogue with one another and to see where recurring topics emerged in our data. Finally, we collectively decided from our notes, what initial codes came together into larger categories, and ultimately our themes. Self-study and autoethnographic researchers often “write in first person, using a multi-genre approach that can incorporate short stories, poetry, novels, photographs, journals (Hamilton, Smith, & Worthington, Citation2008, p. 22). We present our data as our collective analysis across our narratives, conference presentation, and the teaching lesson.

Findings

We created three main themes across our data sets: 1) Organic Relationships, 2) Shared Vulnerability, and 3) the journey we are on. Given the nature of our data collection, we begin each theme with an aesthetic description of our presentation and teaching. In addition to the words we analyzed, we paid attention to the nonverbal body language we each communicated as well as the observed energy in the room. We do this so as readers you can embark upon this journey with us, hopefully gaining a visual representation in addition to our written descriptions of these main themes.

Organic relationships

Sitting side by side are three bodies of different ages, races/ethnicity, and positions. We navigate setting up for our presentation, Jazmin is busily setting up our video camera making sure we are all in view. There is laughter and smiles amongst us as we organize. Brittany commands the room as she starts speaking. She is very used to giving presentations after spending a number of years in the academy. Dominique feels nervousness, but hides it through her laughter. We only know this later after she reveals this to us. Jazmin is presenting for the first time at an academic conference. You wouldn’t necessarily know this given her confidence and ability to interact with adults twice her age with ease. We begin to move into the “assigned” parts we practiced, but go off track a bit. It feels easy though. We ebb and flow. One person says something and then another piggy-backs off of that. It’s as if we are in each other’s head. The nervousness simmers. We are now in synergy. That is the beauty of this relationship (Supplementary material).

One very obvious stream throughout our conversations around our narratives, presentation, and teaching was our repeated mentioning of the organic development of this relationship. This not only came up in our informal conversations between one another while preparing for AESA, but also in our written analysis of watching the videos. Brittany shared in her writeup: “Overall, watching these videos, I felt at ease with us. I was impressed by how easily we just collided with one another. I know we “practiced” in certain ways, but mostly I felt that we just ebb and flowed.”

Similarly, Dominique discusses an idea of “intergenerational support” when she shares: “I like this idea of an intergenerational support network that arises in how we describe our connection to one another. We also describe it as an organic relationship of complex positionalities.” As a tenure-track professor (who just recently was granted tenure), doctoral candidate (who has now graduated), and undergraduate student, we are in different parts of our journeys. Dominique is now working as a participatory researcher in the non-profit sector and continuing to teach in the academy, while Jazmin is already thinking about applying to graduate school once she graduates. This idea of being “intergenerational” doesn’t necessarily speak to our age, but instead our life experiences and trajectories. Again, this was all part of a natural process that shaped our relationship, but also informed each of us how these different stages in our life impacts the work we do.

An additional part of this relationship worth noting is Jazmin’s emphasis on feeling validated. In our presentation, Jazmin asked: “what does it mean to be in a format where students can communicate openly and honestly?” Part of Jazmin’s ability to be a part of this triad was because she felt heard. She felt that she had something to offer, often calling herself a type of “informant.” As a white female undergraduate student learning about racism and whiteness, she went through similar feelings of defensiveness we often see reported in the literature. But what was different for her? What made her want to push past this and keep learning? It was the humanizing factor of having mentors who cared about her and cared about her willingness to work against oppression. Perhaps this might seem more intentional than organic, but when teaching about race, we believe you must validate a student’s humanity. We do not mean excusing resistance, willful ignorance, or socialized racism. Rather this means disrupting this because you care. For us, this is fostered through our mutual support and understanding.

Shared vulnerability

Throughout the co-teaching session, there is an observable positivity among the three of us. The energy in the room when we were teaching together felt supportive and encouraging. However, as we entered our time together the energy of the classroom space was palpably a bit uncomfortable amongst the students in the room. The addition of Dominique and Jazmin in the space shifted the energy about what to expect from the class that day. Over the course of the first fifteen minutes or so the class began to shift and the students began to share more freely. Brittany had been with the class from the beginning of the semester, while Dominique and Jazmin were guests that were meeting this particular group of students for the first time. There is always a delicate balance that needs to be achieved in order to have edifying conversations about race in the U.S. Introducing new people into that conversation who have not been there from the beginning can shift that delicate balance. However, as time passed the trust that had already been built in the classroom had been extended to the new guests. Additionally, the trust built between Brittany, Dominique, and Jazmin provided a container for the class to have a constructive discussion.

All of us as students and educators have shared with each other how vulnerable it feels to teach about race, especially in the context where we are doing this work. Each of us navigates the complexities of our own positionalities in relationship to how the students we face perceive us. We dance between the relationships of power, privilege, and oppression that come with each of those positionalities. We literally put our skin and flesh on display in the classroom and essentially ask the students to do the same. These dialogues feel tender and difficult for all of us. We work to prepare students for the feelings of discomfort that many are not prepared for, especially white students, who represent the majority in this class. We introduce the class with a text by Margaret Wheatley titled Willing to be Disturbed (Wheatley, Citation2002), inviting students to engage in the course by first asking the following of them:

As we work together to restore hope to the future, we need to include a new and strange ally – our willingness to be disturbed. Our willingness to have our belief and ideas challenged by what others think. … Curiosity is what we need. We don’t have to let go of what we believe, but we do need to be curious about what someone else believes. We do need to acknowledge that their way of interpreting the world might be essential to our own survival…To be curious about how someone else interprets things, we have to be willing to admit that we’re not capable of figuring things out alone. (pp. 38 – 39)

Expressions of shared vulnerability are revealed in how each of us articulates experiences in our own narratives. Brittany speaks to the complex nature of navigating her own racial identity as a graduate student in conjunction with excavating it in relationship to the students in her classroom when she writes:

This [during graduate school in Nashville] is the first time I really began to

understand the impact that racism had on education. This was also the first time I

was asked, “what are you?” While I was not (and do not identify) as a person of

color, but I wasn’t white … I was clearly ambiguous enough to warrant such a

question. Then I learned, I wasn’t white enough.

When we, as students, are able to communicate openly and honestly with those who will guide us on the path to personal development, we are willing to ask the hard, awkward, uncomfortable questions. We are able to conceptualize our experiences and learn to ask “How do I practice anti-racism?”

I drive my Black body, 45 minutes from my apartment to the university where I teach

through rural Ohio, past oversized signs in support of the 45th president and confederate

flags. It is never lost on me that my presence in this space is contentious and

temperamental.

The journey to be critical pedagogues

Brittany and 3 first met in Dominique’s classroom. There was excitement and energy flowing through Dominique’s room- she always brings an essence of positivity to the spaces she occupies. Brittany had given this lecture a million times it seemed, but it was still always really scary to be up there in the front of the classroom, sharing her flawed self with future teachers. Letting them read a diary entry she had written her first year teaching. It was actually kinda embarrassing. BUT, if there is one thing she knew, it was that everyone starts off somewhere on this journey. So it was important for her to do this. Dominique enthusiastically supported Brittany and was able to co-narrate her own journey to becoming a critical pedagogue. As Jazmin sat there in the classroom, she was intrigued by these two women and what they had to say. Just a few short weeks later Jazmin visited Brittany’s office. That was her beginning of the journey to be a critical pedagogue ….

The last consistency we found between our data was the ways we all discussed the journey we are on. We call this our journey- because we recognize we are never done learning. For Jazmin, since she is starting this journey much earlier than Brittany and Dominique she shares, “I have started a timeline of how I have become conscious of the world and my view within it.” We are impressed (Brittany and Dominique) by Jazmin’s critical self-reflection and only wish we had been so cognizant during our college years! But here, we can learn from Jazmin as much as she feels she has learned from us. To elaborate on Jazmin’s journey, she shares:

I recognized that I am still within the process of working towards anti-racism. I recognize, now more than ever, that one does not change overnight. There is a process and mistakes and realizations and expansion. I believe that we have to realize this process of unlearning and regrowing is challenging. That growth can only come when you are pushing yourself past the barriers of your own mind. I believe to teach Critical Race Studies, we (as educators) must walk in tandem with them (students) validating their effort and progress, and sharing our stories of challenge and how we continued.

Deciding to step into a classroom as an instructor for the first time, I took on a job teaching primarily privileged, mostly white, students in an honors program. The level of anxiety I felt surprised me, imposter syndrome took over. As a fat Black woman it was not lost on me that I might be one of very few Black faces these students ever see in this role in this institution. This has followed me into my role as a graduate teaching assistant.

There is a sense of metacognition we have each spoken too regarding our journeys in becoming critical pedagogues. We are at different stages, but nevertheless we are all on this journey. We each validate each other’s experiences and recognize how our positionalities shape our experiences. Brittany has been doing this the longest in terms of formal teaching, so her starting point often is shaped by students’ reactions (whether positive or negative) to her pedagogy. She shares:

Regardless of students’ reactions, I know that we must keep teaching. I believe in education, or I wouldn’t be here. I wouldn’t be able to sit and do this work day upon day. Education alone is not enough- students can have all the knowledge in the world, but this needs to change their hearts. I believe that love is key to this sort of teaching. Even when I might come across as being “mean” or that I “hate white people” (which I have heard in my teaching evals), I know that this type of “tough love” is necessary when teaching about race, racism, and whiteness to our predominantly white students.

Discussion

At the time we began working together in 2018 we could not have imagined how the world would shift around us. In the wake of the 2020 global pandemic, uprisings in response to the killings of unarmed Black civilians and police brutality, teaching for racial justice has new urgency. It has always been necessary but feels especially salient in this present moment e. Teaching for racial justice, and teaching CRT, has always been contentious, but currently we are met with even greater challenges.

In order to combat white supremacy, it is important that students have robust knowledge of the shameful history that has led to this essential social disruption. In our view it is imperative, especially in PWIs, that students have the opportunity to grapple with institutionalized and structural racism in addition to their own positionalities. The EDL 204 course is an example of structural curricular change that moves the focus of minoritized experiences from the margins to the center; and we are examples of the lived curriculums as the instructors. We invite educators to re-examine their curriculums to explore whose experiences are missing, marginalized, and devalued, as well as to examine their role in collaboration and delivery. How might the current curriculums (including ourselves) uphold white supremacy, and consider the use of CRT as a tool for this re-examination? Additionally, the course model allowed for us to creatively build a critical collaborative community. These types of relationships aren’t always fostered in the structure of a university- and as professors/instructors, we must find ways to create this. The relationships we have forged provide an example of the power this type of curriculum holds for students and educators. The thoughtfully developed curriculum provided us an opportunity to grow understanding and empathy for students, faculty and ourselves. For us to teach for racial justice, our findings indicate that we need to form relationships with one another (ours was natural, but we recognize there are other ways to build these), gain a shared vulnerability, and come to terms with the fact that this is an evolving journey. We do not wish to generalize our findings – as they are specific to our triad – but we do offer implications of what we have learned in connection to the literature as a call for action for other educators to work critically and collaboratively with one another in their college classrooms.

Building from awareness

There is a widespread consensus across the literature pertaining to racial justice and alike, that awareness and understanding of the existence of systematic racism is the first and most critical step in educating students about racism (Adams, Citation2007; Amos, Citation2011; Blakeney, Citation2005; Borsheim-Black, Citation2018; Buchanan, Citation2015; Case, Citation2012; Cutri & Whiting, Citation2015; Damrow & Sweeney, Citation2019; DiAngelo, Citation2018; Jordan & Schwartz, Citation2018). Thus, as college educators, we must first begin here by teaching from an understanding that not all students come to our classrooms informed. For us, in EDL 204, we took an historical approach to fostering this understanding. We anchored all of our lessons in history, but then made relevant connections to the present. We also used ourselves as the curriculum, sharing our stories and our struggles along the way.

There are many practices to aid in the process of connecting the understanding of systemic racism to the individual. One example shared by Rousmaniere (Citation2000) utilized a reflective writing approach to understand one’s own educational experience. She explains “the educational autobiography exercise also goes beyond the personal, as intense personal recollections move quickly into considerations of curriculum, and ultimately, of educational politics” (p. 96) This practice allows the pre- and in-service teachers to question how and why the school functions as a whole and the complex relationship of systematic oppression that affects schooling and education. This reflection process can be useful for many students as they discover the privileges and oppression that they experience. In order to connect these experiences to structural racism, Cutri and Whiting’s research (Citation2015) reveals “that attention to privileges associated with social class could provide powerful entry into examinations of other personal privileges in critical multicultural education” (p. 19). The authors argue that viewing a different, more tangible experience of systematic oppression allows for an easier interpretation of theories students may not as easily relate to such as CRT.

As students become equipped with this new lens of understanding the world, it isn’t long before a wave of shame and/or guilt clouds their thoughts as they become increasingly aware of the unintended actions, they have taken to progress this system. In this next step, we come to find that empathy and community play a large role in the student’s ability to come out of a place of guilt and into a place of growth.

Empathy and critical community building

Within our triad, we shared empathy for one another leading to our ability to be vulnerable. For the students who chose to continue their journey of pursuing racial justice and finding individual liberation, an environment that is centered around building relationships and empathy will help to build resilience to challenges and failures (Amos, Citation2011, Citation2016; Blakeney, Citation2005; Buchanan, Citation2015; Case, Citation2012; Damrow & Sweeney, Citation2019; DiAngelo, Citation2018; Jordan & Schwartz, Citation2018). Jordan and Schwartz (Citation2018) examine radical empathy, the “radical acceptance of vulnerability, an openness to being affected by one another,” (p. 28) in the classroom. Specifically, the authors examine how teachers who utilize radical empathy are able to connect with their students and the curriculum in a way that is engaging and transparent. This practice of radical empathy in teaching asks for the teachers to not only acknowledge the realities of the community and of each student’s experiences but also to offer up some insight into how the teacher thinks about, is challenged by, and/or has grown as it relates to the topic. In doing so the student may be more inclined to grapple with the materials and content on a personal level allowing for an authentic practice of learning and a growth mindset in the presence of failure. We found in our own research that we exhibited radical empathy with one another, but also it became an inherent part of our teaching in the classroom. Modeling this for our students was also an important part of our vulnerability practice.

Empathy and critical community building are shown to provide catalysts for personal and cultural growth. It becomes clear that one cannot be completely rid of racist thoughts or behaviors, rather it is lifelong practice and skill that must be continually built upon. In order to continue this practice, it is beneficial to hold a growth mindset in the presence of ‘slip-ups’ and failure. As well as create a big picture goal in which to strive. In the pursuit of racial justice, one (holding any privileged identities) must take on the role of co-conspirator (Love, Citation2019) in which there is a responsibility to develop one’s personal growth and community growth, as society works to liberate all citizens.

Implications for teaching and teacher education

As we’ve shared, awareness and empathy building are two components where we have found success in our efforts to learn and teach for racial justice through a CRT lens. We find value in this work due to its focus on collaboration across power dynamics (i.e. rank of professor, graduate, and undergraduate students) as well as our positionalities across womanhood based on race, ethnicity, class, able-bodiedness, and sexuality. This unique tri-dimensional model of teaching and learning is something we believe contributes to the literature pertaining to how we learn from each other and inform the radical empathy we practice.

The art of teaching is inherently a communal experience. Teacher educators and teacher education would benefit from creating intentional opportunities for shared growth across identity and positionality; especially as it relates to learning to teach about racial justice through CRT. Between the current political climate and the fact that institutions were not built to support people at the margins (e.g. women of color, disabled folx, etc.), finding ways to offer mutually support systems is essential to keep racial justice work alive. For example, within our triad, Brittany and Dominique were able to leverage from the growth and vulnerability of Jazmin, who explicitly spoke about g grappling with how whiteness has influenced her identity development. Brittany and Dominique (as the professors) would not have been able to have the same amount of influence that Jazmin had with her peers.

We are preparing future generations of educators to be able to stand in solidarity with each other and their students to combat white supremacy in education. The current anti-CRT climate creates an even stronger need for community building within the field. We offer just one example of how this might be practiced and invite our audience to do the same

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (561.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Brittany Aronson

Brittany Aronson is an Associate Professor in Teacher Education at Pennsylvania State University. She teaches classes in social justice in education, sociology of education, and racialization anti-Blackness, and whiteness in education. In her scholarship, she focuses on preparing educators to work against oppressive systems as well as critical policy analyses of both popular and political discourse. Her research interests include critical teacher preparation, social justice education, critical race theory, critical whiteness studies, and educational policy. Dr. Aronson earned a PhD in Learning Environments and Educational Studies from the University of Tennessee in 2014.

Dominique M. Brown

Dominique M. Brown is an educator at heart. All of her work comes back to teaching and building into others. She develops curriculums rooted in anti-oppression frameworks, facilitates critical dialogues, and creates spaces centering women of color. She earned a Ph.D. in Educational Leadership from Miami University in 2022. As a holistic educator focused on promoting the wellbeing of women in the African diaspora, She specializes in cultivating womanist healing practices for and with Black women. She is trained in somatic movement, meditation, and contemplative practices. She collaborates with practitioners who focus on yoga, creative/art healing practices, Black folk healing, etc. as a means of alleviating racialized trauma. Her research interests span the cross-sections of womanism/Black feminism and the African Diaspora; integrating critical pedagogy and contemplative practice.

Jazmin Tangi

Jazmin Tangi recently graduated from Miami University (OH) in 2023, earning a Bachelor of Science in Education Studies with a concentration in Education and Social Entrepreneurship and a minor in Disability Studies. During their time in the program, Jazmin influenced the direction of the program and department. They advocated for refinements in the curriculum offerings, fostered partnerships across colleges, and collaborated with leadership to improve program engagement and relevance. Social justice and liberation are at the core of their endeavors, with specific career interests including (but not limited to) curriculum development, education policy, and community-based participatory research.

Notes

References

- AJ+. (2017). Why do we call Asians the model minority?. YouTube, October, 8. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PrDbvSSbxk8

- Annamma, A. S., Connor, D., & Ferri, B. (2013). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. Race Ethnicity and Education, 16(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2012.730511

- Adams, M. (2007). Pedagogical frameworks for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 15–33). Routledge.

- Amos, Y. T. (2011). Teacher dispositions for cultural competence: How should we prepare white teacher candidates for moral responsibility? Action in Teacher Education, 33(5-6), 481–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2011.627037

- Amos, Y. T. (2016). Voices of teacher candidates of color on white race evasion: ‘I worried about my safety!’. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(8), 1002–1015. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1174900

- Archer, L., Burke, P. J., & Crozier, G. (2016). Peer relations in higher education: Raced, classed and gendered constructions and Othering. Whiteness and Education, 1(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/23793406.2016.116474

- Blakeney, A. M. (2005). Antiracist pedagogy: Definition, theory, and professional development. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 2(1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2005.10411532

- Borsheim-Black, C. (2018). “You Could Argue It Either Way”: Ambivalent white teacher racial identity and teaching about racism in literature study. English Education, 50(3), 228–254. https://doi.org/10.58680/ee201829578

- Buchanan, L. B. (2015). “We make it controversial” Elementary preservice teachers’ beliefs about race. Teacher Education Quarterly, 42(1), 3–26.

- Buckley, J. B., & Quaye, S. J. (2016). A vision of social justice in intergroup dialogue. Race Ethnicity and Education, 19(5), 1117–1139. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2014.969221

- Camangian, P. R., Philoxene, D. A., & Stovall, D. A. (2023). Upsetting the (schooling) set up: Autoethnography as critical race methodology. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 36(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2021.1930266

- Case, K. A. (2012). Discovering the privilege of whiteness: White women’s reflections on anti-racist identity and ally behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 68(1), 78–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01737.x

- Chang, H., Wambura Ngunjiri, F., & Hernandez, K.-A. C. (2013). Collaborative autoethnography. Routledge.

- Cutri, R. M., & Whiting, E. F. (2015). Naming a personal “Unearned” privilege: What pre-service teachers identify after a critical multicultural education course. Multicultural Perspectives, 17(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15210960.2014.984717

- Damrow, A. L., & Sweeney, J. S. (2019). Beyond the bubble: Preparing preservice teachers through dialogue across distance and difference. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.02.003

- Delgado, R., & Stefanic, J. (2023). Critical race theory: An introduction. New York University Press.

- DiAngelo, R. (2018). White fragility: Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism. Beacon Press.

- Ellis, C. (2004). The ethnographic I. Altamira Press.

- Education Week. (2021). Map: Where critical race theory is under attack. Education Week, June 11. https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/map-where-critical-race-theory-is-under-attack/2021/06

- Fine, M. (1997). Witnessing whiteness. In M. Fine, L. Wies, L.C. Powell & L. Mun Wong (Eds.), Offwhite: Readings on race, power, and society (pp. 57–65). Routledge.

- Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Rowman & Littlefield Publisher, INC. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- French, P., James-Gallaway, C., & Bohonos, J. (2022). Examining intergroup dialogue’s potential to promote social justice in adult education. Journal of Transformative Education, 20(1), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/15413446211000037

- Hamilton, M. L., Smith, L., & Worthington, K. (2008). Fitting the methodology with the research: An exploration of narrative, self-study and auto-ethnography. Studying Teacher Education, 4(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425960801976321

- Han, H. S., Vomvoridi-Ivanović, E., Jacobs, J., Karanxha, Z., & Feldman, A. (2017). Using Collaborative Self-Study Methods to Explore Culturally Responsive Pedagogy in Higher Education. In SAGE Research Methods Cases (pp. 1–15). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sophia-Han-4/publication/314283221_Using_Collaborative_Self-Study_Methods_to_Explore_Culturally_Responsive_Pedagogy_in_Higher_Education/links/5a484a01aca272d2945fdad3/Using-Collaborative-Self-Study-Methods-to-Explore-Culturally-Responsive-Pedagogy-in-Higher-Education.pdf

- Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

- Hughes, S. A., & Pennington, J. L. (2017). Autoethnography: Process, product and possibility for critical social research. SAGE.

- Jackson, R. L. (1999). White space, white privilege: Mapping discursive inquiry into the self. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 85(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335639909384240

- Jordan, J. V., & Schwartz, H. L. (2018). Radical empathy in teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2018(153), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20278

- Keehn, M. G. (2015). When you tell a personal story, I kind of perk up a little bit more”: An examination of student learning from listening to personal stories in two social diversity courses. Equity & Excellence in Education, 48(3), 373–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2015.1056712

- LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J.J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching practices (pp. 817–869). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2004). Landing on the wrong note: The price we paid for Brown. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033007003

- Ladson-Billings, G., & Tate, W. F. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 97(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146819509700104

- Lapadat, J. C. (2009). Writing our way into shared understanding: Collaborative autobiographical writing in the qualitative methods class. Qualitative Inquiry, 15(6), 955–979. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800409334185

- Love, B. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

- Lomawaima, K. T., & McCarty, T. L. (2006). To remain an Indian: Lessons in democracy from a century of Native American education. Teachers College Press.

- McLaren, P. (2002). The critical pedagogy reader. Routledge.

- Matias, C. E., & Newlove, P. M. (2017). Better the devil you see, than the one you don’t: bearing witness to emboldened en-whitening epistemology in the Trump era. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(10), 920–928. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1312590

- Moon, J. (2018). Why Mendez still matters: Meet the school desegregation case that still affects ELL instruction today. Teaching Tolerance. https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/spring-2018/why-mendez-still-matters

- Morales Morales, D., Ruggiano, C., Carter, C., Pfeifer, K. J., & Green, K. L. (2020). Disrupting to sustain: Teacher preparation through innovative teaching and learning practices. Journal of Culture and Values in Education, 3(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcve.03.01.1

- Muncey, T. (2010). Making sense of autoethnographic texts: Legitimacy, truth and memory. Creating autoethnographies. Sage.

- Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2014). Racial formation in the United States. Routledge.

- Rousmaniere, K. (2000). From Memory to Curriculum. Teaching Education, 11(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210050020417

- Samaras, A. P. (2002). Self-Study for teacher educators: Crafting a pedagogy for educational change. Peter Lang.

- Sensoy, O., & DiAngelo, R. (2017). Is everyone really equal? An introduction to key concepts in social justice education (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

- Zamudio, M. M., Russell, C., Rios, F. A., & Bridgeman, J. L. (2011). Critical race theory matters: Education and ideology. Routledge.

- Wheatley, M. J. (2002). Turning to One Another: Simple Conversations to Restore Hope to the Future. Berrett-Koshler Publishers, Inc.