Abstract

Seven inscriptions from Oine on Ikaria that refer to Samians residing on the island have long been used to argue the case for Samian political control over Ikaria. This article seeks to reassess what these inscriptions tell us about Samian–Ikarian interactions by exploring different models of connectivity for the two islands. Specifically, this article considers short-range mobility, and the capacity of each island to perform various political functions.

The island of Ikaria lies just 20 kilometres west of Samos in the east Aegean region (). On a clear day one island is clearly visible from the other and due to their proximity and geography, Samos and Ikaria along with the Fournoi islands form a natural archipelago (). Samos has a well-documented supra-regional history in Antiquity, supported by historical and literary texts, inscriptions, and archaeological evidence from both Samos’s Heraion sanctuary and its wider hinterland, all indicating that the island was a once-famed maritime superpower. By contrast, barely anything is known of the history of Ikaria, with a much less intensively studied archaeology, a significantly smaller epigraphic dataset, and literary mentions occurring few and far between. Only a general picture can be sketched out: for a large part of the third century BCE Ikaria had enjoyed a period of relative stability under the Ptolemaic rule of the east Aegean area,Footnote1 a factor that enabled the island to develop a wide-reaching and renowned export network for its local wine.Footnote2 Moreover, very little is indeed known about the relationship between Samos and Ikaria, and regarding the logistical connections between the two islands.

Figure 2. View from Mt Kerkis, west Samos. The Fournoi archipelago is visible in the foreground, and the tip of Ikaria is just visible to the right side of the photograph. Photograph by the authors.

For the Hellenistic and Roman periods (late fourth century BCE to mid-second century CE), the traditional view is that Samos exercised some degree of control over Ikaria, although this is more generally assumed than extensively proven. By “control”, it is understood that the Samians expanded their territory between islands, increasing the area from which they could source natural resources like vine and timber, and holding exclusive rights to perform various political functions. This picture is drawn, to a large extent, from a set of seven inscriptions found in the Ikarian polis (city-state) of Oine, dating between the second century BCE and second century CE and all making reference to the “Samians on Ikaria”, the “Samians who live on Ikaria”, or “the Samians who live in Oine”. This formula of residency has been used to suggest control of Ikaria (or at least of Oine) by Samos, generally maintaining the view that the Samians moved onto Ikaria during a time when it was otherwise abandoned – but this does not necessarily have to be the case.

This article discusses these “Samians on Ikaria”, questioning what groups there were living in Oine and nearby. It also asks whether our interpretation of the Oine inscriptions must revolve solely around the notion of complete political control. In doing so, we address some specific substantive points about the history of these particular islands: namely, regarding what the inscriptions discussed tell us about the political functions of both Oine (alongside the Ikarian polis of Therma) and of Samos, as well as their respective capacity to enact various political functions. However, this case study bears relevance beyond its immediate scope, extending to broader themes in Mediterranean history, particularly the dynamics of connectivity and interaction among island communities. As emphasized by broad-scale Mediterranean histories ever since Braudel, the mobility of proximate communities in highly networked ecological niches naturally fluctuates over a longue durée. In contrast, our focus on these two island communities allows us to consider specific political and cultural factors that contribute to the connection or isolation of neighbouring groups such as the Samians and Ikarians.

Critical to our discussion is the exploration of inter-connection at three levels: the island; the polis (city-state); and the community of practice. Regarding the island itself, Samos – similar to nearby east Aegean islands – variously expanded its network to off-island areas, using terrain on other islands or on proximate mainlands (known as peraia) for cultivation and settlement. At a higher level, then, we recognize that the insularity of such places transcends geographical boundaries, prompting us to consider territorial and political boundaries that cross between islands, partially or entirely.Footnote3 In the context of the polis, our case study from the worlds of Hellenistic and Roman Greece comes from a period in which different political units of varying sizes and complexity performed a range of political functions. That is, it is reasonable to anticipate that individuals from the political communities of Samos would exercise and manifest power differently from their counterparts in Ikarian poleis. Our analysis therefore contributes to a broader discussion on how poleis enacted political processes, and how interactions between such units fostered new forms of engagement, whether cooperative or competitive. Moreover, regarding the community, we acknowledge that different groups – regardless of political status or relationship to the polis – had diverse writing practices and ways to document historical information. As a consequence, communities of practice assume a crucial role in our discussion of trans-island interaction.

The focus here is on historical enquiry which, although dealing primarily with a theory first drawn from a set of inscriptions, is not epigraphic in its focus. Instead, this article will look at the inscriptions in their wider context, considering also how the island in the late Hellenistic and Roman periods fits into wider theoretical frameworks about mobility and connectivity.

1. Late Hellenistic and early Roman Oine

The ancient settlement of Oine is located on the north coast of Ikaria in the periphery of modern-day Kampos, two kilometres west of the port of Evdilos. According to the Pseudo-Scylax (58), written in the mid-fourth century BCE, Oine was just one of two poleis on Ikaria (the island is reported as being dipolis), the other being Therma. Communities of those from both Oine and from Therma are assessed separately for tribute on the mid-fifth-century Athenian tribute lists, noting in separate years the assessment of both “those from Oine on Ikaria” and those “off Ikaria”, a point which will be discussed further below. Regarding Oine itself, situated adjacent to the church Ayia Eirini, standing remains of a bath complex and an odeonFootnote4 were already known in the late nineteenth centuryFootnote5 and further explored in the first half of the twentieth.Footnote6 While the dating of the monuments themselves as Roman is dubious and more probably fifth/sixth century CE,Footnote7 a number of Hellenistic and Roman small finds and inscribed stones came to light during the course of the excavations, many of which are now kept in the Kampos archaeological museum, or in the courtyard of Ayia Eirini.

Among these finds were a set of seven decrees and honorific inscriptions dating between the second century BCE and the second century CE (Inscriptiones Graecae (IG) XII 6, 2, 1217–1223; Appendix nos. 1–7). Although relatively few in number, this corpus constitutes almost 10% of the known epigraphic material from Ikaria. That is, only 75 inscriptions originate from Ikaria (),Footnote8 where the majority (55 of 75) are short funerary inscriptions that tell us relatively little about the political status of the island in Antiquity. Even fewer inscriptions are found on Fournoi (21), and 11 of these (IG XII 6, 2, 1213) are brief rock-cut graffiti. By contrast, 1196 inscriptions originate on Samos, 146 of which are dedicatory and honorific inscriptions of the Hellenistic and Roman periods (statistics from across IG XII 6, 1 and 2).

Table 1. The inscriptions of Ikaria as published in Inscriptiones Graecae. Where the information is known, type of inscription, date, and findspot are indicated.

Seven inscriptions talk of “Samians on Ikaria” or “Samians who live on Ikaria” (), while two of these seven explicitly mention “Samians in Oine”. The text of two is reconstructed to make reference to those “on Ikaria”, but otherwise unquestionably mentions the Samians. On IG XII 6, 2, 1219, the Lerians are named alongside the Samians as enactors of the honorific. None of these inscriptions carry mentions of the boulē (βουλή, council) or dēmos (δῆμος, people), unlike other contemporary inscriptions enacted by the Samians put up elsewhere, and discussed further below. The inscriptions date between the first half of the second century BCE and 138–161 CE, providing a continuous (although sparsely populated and selective) sequence. Two inscriptions are from marble stelai (upright slabs), two from columns, and the other three from marble bases.

Table 2. Inscriptions from Oine, Ikaria, as discussed in this article. These inscriptions appear in full in the Appendix.

That it is Samians performing the dedicatory and honorific actions cannot be disputed. The only inscription surviving that documents Ikarians (or, specifically, the people of Oine) performing any sort of political action dates from at least two centuries earlier, on the fourth-century proxeny decree (IG XII 6, 2, 1224) granting privileges to Pausimachos from Byzantium (as was perfectly normal for Greek city-states to bestow the formal honour of proxenos upon individuals from foreign political entities). Elsewhere on the island, only one other honorific is found, which, while contemporary (first century BCE), is not actually from a polis but from the small settlement of Drakano. On this inscription (IG XII 6, 2, 1285) the dēmos is named as the enactor of the decree, presumably referring to the people of Drakano, since no other group is specified. A similar honorific is found on the Fournoi islands from the same period (IG XII 6, 2, 1203), dating to the second century BCE and referring generally to the “Samians on Corsiae [ancient Fournoi]”. Beyond the archipelago, inscriptions worthy of note come from Amorgos, Kos, Magnesia, and Rhodes, all places where there was a Samian presence “overseas” alongside other communities. All these inscriptions, and others, will be discussed in greater detail below.

2. Samian control over Ikaria

According to the generally accepted view, by the time the island was integrated into the Roman province of Asia in 129 BCE, the once far-reaching networks of Ikaria had all but disappeared, and the Samians had taken control of the island.Footnote9 This idea can be traced back to an article of Louis Robert (Citation1933), in which the author put together two pieces of evidenceFootnote10: first, that Strabo notes that in the first century CE Ikaria was “deserted” (10.5.13, 14.1.19); second, that the inscriptions of Oine designate that it is the “Samians on Ikaria” who perform the honorific and dedicatory functions. This indicates, in Robert’s view, that after a brief time during which the island was completely abandoned, perhaps from a period of unrest and depopulation,Footnote11 the Samians moved in to use the natural resources of Ikaria in the same way that they had used the peraia (i.e. the area of Mycale on the modern Turkish mainland, lying opposite Samos).Footnote12 Perhaps the sole occupants of the island – or living alongside other communities, perhaps staying on the island permanently or perhaps moving seasonally (or otherwise) back to Samos – this group of Samians were understood to be the sole enactors of political functions on Ikaria, and therefore thought to “control” this aspect of the island.

It is perfectly possible to follow Robert in the view that the Samians had complete right over Oine during the time these seven inscriptions were put up, and the best evidence can be found in the force of the languages used. Three formulae are used to define the Samians on Ikaria in this group of inscriptions: “hoi oikoūntes” (οἱ οἰκοῦντες), “hoi katoikoūntes” (οἱ κατοικοῦντες), and “apoikōn” (ἀποίκων). Put simply, the semantic impact of all three expressions indicates to “colonise” or to take long-term residency, among other alternatives.Footnote13 Taking this reading, one could presume a model of unilateral migration,Footnote14 of one group of people moving to a new place that was previously either vacant or occupied by another group, motivated by push-and-pull factors. Strabo, at least, would appear to indicate that the Samians moved to Ikaria at a time of complete abandon. Taking this translation, one might read “the Samians [who are the only people who live on Ikaria] colonising Oine”, and assume Samos took “control” of the island.

Similarly, the inscriptions illustrate the political power of the Samians. The two earliest inscriptions are public honorific decrees set up by the Samians in Oine for the services offered by individuals (Appendix, nos. 1 and 2). No. 1 honours Eparchides for his good will and excellence towards the Samians, setting up a statue and the inscribed decree in thanks for this; no. 2 honours Timesileos again for his general excellence and generosity but also for undertaking important offices such as the stephanēphoros (an annually awarded priesthood associated with the cultic handling of wreaths) and organizing processions. The fragmentary state of no. 2 provides no information regarding how Timesileos was to be honoured or regarding where the inscription was to be set up. It is not possible to tell without further external evidence whether those named on this stone are Samian or Ikarian magistrates, permanent or temporary residents: there are two generations of Timesileoi named on a third-century BCE funerary monument from Ikaria (IG XII 6, 2, 1240) and a Theodoros son of Dimitrios who is dēmiorgos (magistrate) on Samos on a stone found at the Heraion (IG XII 6, 1, 198) in the second/third century CE. However, the chronology for these pieces is not near-contemporary enough to help the interpretation of no. 2, unless we take it as a much later date than has been previously assigned, in the second or third century CE, and assume that Theodoros is a Samian magistrate visiting from Samos to Ikaria to enact this honorific. The Samians in Oine were able to deliberate with enactment formulas as seen at [ἔδ]ο̣ξεν Σαμίοις τοῖς κατοικοῦσιν Οἴνην (no. 1, l.3), suggesting a political independence of the Samians on Ikaria and the role of the inscription in acting as a display of their political power.Footnote15 Furthermore, the Samians appear to have exercised a level of control over the public spaces of the island at this time. In no. 1, for instance, the bronze statue of Eparchides was to be set up “in the agora” (ll.1–5) with the decree placed alongside it (ll.6–8). That this refers to the agora in Oine is uncertain from the text alone, although Matthaiou and Papadopoulos deduce that as the inscription was found in Kampos, a placement at Oine would seem most reasonable.Footnote16 The inscriptions from Oine thus provide compelling evidence of the political power and autonomy of the Samians residing there in the second century BCE, as demonstrated through their enactment of public honorific decrees and control over the island’s public spaces.

Whether any Samian political control over Ikaria continued beyond the second century BCE, however, is difficult to ascertain. After this point, the Samians no longer enacted decrees on the island. Instead, they are recorded as setting up five short honorific inscriptions that honour Augustus, Nerva, Hadrian, and Antoninus Pius (see Appendix, nos. 3–7). Such inscriptions reflect the continued presence of the Samians on Ikaria and their active engagement in public life. The ability to set up honorifics in this way suggests that the Samians still held a degree of control over the island’s public spaces; they perhaps even received benefactions from certain emperors given the reference in no. 5 to Hadrian as saviour and founder (sōtēri kai ktistē, “σωτῆρι καὶ κτίστῃ”). There is no further evidence for what Hadrian founded in this case, or whether this was on Samos or Ikaria, though the use of the terms is suggestive of a relationship between the Samians and the emperor. However, the absence of enactment formulas makes their political control less explicit, and could indicate a change in the island’s political dynamics. Further to this is the choice of language in the inscriptions: in contrast to the decrees enacted in the second century BCE, which specifically refer to the Samians dwelling in the settlement (and thus within the community) in Oine, the Imperial honorary inscriptions refer more generally to the Samians residing on Ikaria. Whether or not this is a semantic shift or simply a substitution of a different formula is difficult to ascertain, but the case for a change in political organization is compelling when taken with the aforementioned fact that the tradition of enacting decrees disappears as the dynamics within the community appear to shift. Comparative evidence from the early third century CE illustrates that these shifts were specific to Ikaria; Samians living in Minoa on Amorgos, for instance, continued to deliberate with enactment formulas within specific communities (e.g. IG XII 7, 240, ll.1–2: Σαμίων [τῶν Ἀμοργ]ὸν Μεινῴαν κατοικούντων ἔδοξεν ἄρχουσι, βο[υλῇ], δήμῳ, as is discussed further below).

So, what does this mean for the Samians on Ikaria? On the one hand, the language shift from specific communities to the wider island could plausibly (though tentatively) be read to suggest that the Samians had assumed control of the entire island at some point after the second century BCE. On the other hand, the language shift might be better seen as a broader adjustment in Samian perspectives of Ikaria and their political and physical relationship with the island. This requires an alternative explanation that goes beyond the simplicity of political power and control purported in previous readings of the epigraphic record of the Samians on Ikaria.

3. Samian communities on Ikaria

The alternative, though, of Samian control over Ikaria is to consider the presence of Samian communities alongside groups on Ikaria, perhaps permanently or perhaps short-term/seasonally. That is, another option is to take “hoi oikoūntes” (οἱ οἰκοῦντες)”, “hoi katoikoūntes” (οἱ κατοικοῦντες)”, and “apoikōn” (ἀποίκων)” with their alternative meaning of “inhabit” or “settle”.Footnote17 This allows for an inclusive interpretation of “the Samians [one group of many on Ikaria] who inhabit Oine”. Indeed, this sort of reading does not even require the Samians to live permanently on Ikaria, and in fact both situation and geography would permit more frequent, shorter, temporary human movement between the two islands, or what one might call short-range mobility.Footnote18

There was already a tradition of mobile communities in this region long before the Hellenistic period. As noted above, the Ikarians of the fifth century BCE who were assessed for tribute on the Athenian lapis primus comprise of separate groups from Oine and Therma, but they are distinguished separately as those living “en Ikaria” (ἐν Ἰκαρία, “on Ikaria”) (IG I3 259, 261, 263, 271), and “ex Ikaria” (ἐξ Ικαρία, “away from Ikaria”) (IG I3 260, 262, 266, 268, 269, 270, 272, 273, 279, 281). This is a fairly significant formula to appear so frequently across the lists, and only appears with a handful of other communities (Arkeseians on Karpathos, IG I3 270; Brikindarioi on Rhodes, IG I3 285; Diakrioi from Rhodes; Elaiosians in Chersonesos, IG I3 282; IG I3 281, 285, 290; Lemnians in Chersonesos, IG I3 281, 282, 285; Milesians on Leukos, IG I3 259; Pedies from Lindos, IG I3 270, 281; [someone] from Pallene, IG I3 262; [someone] from Tenedos IG I3 265). By far this formula occurs most frequently with those from Ikaria than from any other community, and this should draw attention to two key points. First, that the Ikarians stood out among the other allies to the Athenians as a community more mobile than others, so much so that this was noted in their assessment, and to distinguish the different groups of Ikarians from one another. Second, that the formula “ἐξ Ικαρία” appears more frequently than “ἐν Ἰκαρία”, implying that this group was highly and frequently mobile. It is quite telling that this community is seen as “ἐξ” Ikaria and somewhat on the move rather than being settled “ἐν” somewhere else. Whether this group was mobile supra-regionally throughout the Aegean or just locally across neighbouring Samos, Fournoi, and elsewhere cannot be distinguished from this point alone, but the evidence certainly does point towards a mobile community. More circumstantially, and not from Ikaria itself but indicative of a story of mobility from the same archipelago, the set of fourth-century BCE graffiti from Fournoi extol the virtues of one Epigonos from Samos (IG XII 6, 2, 1213). That his name was so well known and so appreciated might lead one to suggest that he was a frequent visitor from Samos to the Fournoi islands; or, vice versa, that those from Fournoi were liable to frequent trips to Samos, where they saw and got to know Epigonos.

Short-range mobility between (at least) Samos, Ikaria, and Fournoi is plausible, given local geography. The route between Ikaria and Samos is noted by the Pseudo-Scylax in the fourth century BCE as lying on the main maritime route across the east–west axis of the Aegean (113, cf. Thucydides 3.39), specifically connecting Tenos to Mykonos to Ikaria to Samos. Distance was certainly no issue even from around the sixth century BCE, when Herodotus (486) indicates that the maximum sailing time in a day was around 70,000 fathoms (ca. 130 km).Footnote19 But owing to few suitable anchorages in this area, even short-range sailing would require clear weather – something that is not guaranteed around this part of the Aegean for either the winter months or for the mid-summer – making one prone to unpredictable diurnal cycles, and perhaps requiring frequent stops on shorter journeys along the way between the islands.Footnote20 The volume of shipwrecks around the Fournoi archipelago attests that there was a major sailing route in this area, but also affirms its dangerous nature;Footnote21 meanwhile, comparative evidence from the early modern period also indicates the utility of this area as a major crossroads for Aegean-level connectivity moving both north–south and east–west.Footnote22 What does this mean for our present enquiry? In short, it illustrates how the area around Ikaria both before and after the Hellenistic and Roman periods was renowned for being a nucleus of connectivity and a high-mobility zone. It is important to consider, therefore, the possibility of a similar mobility in and around these islands between the second century BCE and second century CE. That Samians appear on the inscriptions as a group making decrees on Ikaria does not indicate their permanence on the island; rather, they could be one of several mobile groups circulating the area, as was common in this part of the Aegean, and their designation as “Samians on Ikaria” is just one way of noting that mobility.

And there is evidence for multiple (mobile) communities inhabiting these spaces. On the one hand, these pointers are internal to the seven inscriptions from Oine. Notably, on Appendix 1, no. 3 the apoikoi include not just Samians but also a community of individuals from Leros.Footnote23 Clearly, at least at the turn of the first century CE when this honorific was made, there were communities originating from different places living together on Ikaria – or at least communities who had once come from different places. The fact that Samians and Lerians are named here is consistent with a number of possibilities: (i) a group of Samians and/or Lerians were accepted into a polis, like in the case of Oine; (ii) a group of Samians and/or Lerians having taken over Oine; (iii) a number of groups of Samians and/or Lerians were living permanently or temporarily on Ikaria; or (iv) groups from different places (e.g., Samians and Lerians) were living in different sites on Ikaria. Whether or not there were still Ikarians living on Ikaria is quite independent of these factors. Why, then, the need for those making the dedication to identify themselves as Samians and Lerians? Why were those making these decrees referring to themselves as “Samians” and not as “Ikarians”, as one might otherwise expect from those who have settled in a new land. For this group to refer to themselves as Samians implies that at the level of the community there is a collective memory of being from Samos, and furthermore that expressing a connection to Samos was particularly important.Footnote24 While such a reading is possible, time-depth reduces its plausibility. That is, if our dataset is a representative sample of the stones that were once inscribed on Ikaria, then there is an almost 300-year gap between the first reference to “Samians on Ikaria” (no. 1, first half of second century BCE) and the latest possible date of the last (no. 7, 161 CE), some 10 generations of 30 years. We would have to accept, then, that even over this multi-generational gap the later inhabitants of Ikaria (i.e. those who did not have life on Samos within their immediate memory) still chose to identify themselves more closely with Samos than with Ikaria. In terms of persistent identities and lingering ethnonyms, this is of course entirely possible – but perhaps not the neatest solution to the problem.

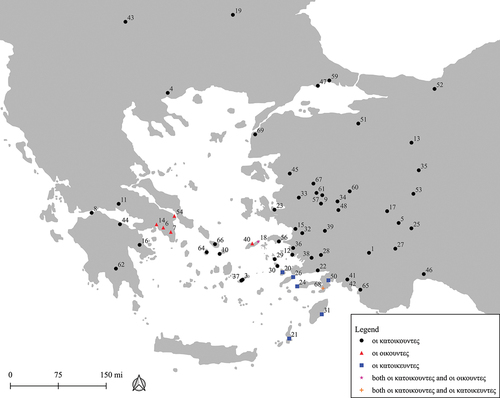

On the other hand, there is also evidence for high mobility and multiple residency when looking beyond Ikaria itself. The residency formulas used on Ikaria are not specific to Samos, nor to Ikaria. The formula “hoi oikoūntes” (οἱ οἰκοῦντες) has (albeit few) parallels, found on a total of eight inscriptions dating between the fourth and second century BCEFootnote25; no. 1 represents the last known use of the term. Three examples are found in Athens, three in Rhamnous, and one in Eleusis, referring to the “Athenians inhabiting Lemnos” (Ἀθηναῖοι οἱ οἰκοῦντες ἐν Λήμνωι), “the Athenians inhabiting the Chersonese” (οἱ οἰκοῦντες Ἀθηναίων ἐν Χερρονήσωι), “those inhabiting the polis of Rhamnous” (οἱ οἰκοῦντες τῶν πολιτῶν Ῥαμνοῦντι), and “those inhabiting Eleusis” (οἱ οἰκοῦντες Ἐλευσῖνι). Even with the limited size of this dataset, one might deduce that the formula is fairly specific to Attica, since no. 1 is the only example found outside of the region (). Such comparanda offer two important insights: first, only three of these examples can be linked to political control in the case of the Athenians on Lemnos and the Athenians in the Chersonese, based on other evidence that Athens exerted some form of political authority or influence over these regions.Footnote26 Each of these inscriptions, however, was set up in Athens rather than on Lemnos or the Chersonese, illustrating that the residency formula was not used to engage with the epigraphic landscape of the region under political control, but with that of the home polis. The second insight is that the formula can be used to refer to co-existing groups in a given place. A decree from Rhamnous provides indisputable evidence of this, highlighting the dynamics of politics and residency in the process:Footnote27 the decree is enacted by the Rhamnousians (l. 1), honouring an individual for his services to the Athenian dēmos and Rhamnousian community, and it references distinct groups co-residing within the fortress of Rhamnous using the formula hoi oikoūntes (the Rhamnousians and the Athenians (ll. 10–11)) and the same within the fortress of Eleusis (the Athenians and the Eleusinians (ll. 13–14)); the decree ends with a dedication from “those among the citizens living in Rhamnous” ([οἱ οἰ]κοῦντες τῶν πολιτῶν Ῥαμνοῦντι (ll. 49–52)). The force of hoi oikoūntes in the Ikarian dataset thus does not necessarily have to imply political control rather than the mere residency of the Samians among other groups given the formula’s different uses in comparative evidence.

Figure 3. Map showing the distribution of epigraphic uses of residency formulae per place in the Aegean and western Anatolia. Drawn by the authors.

The evidence of hoi katoikoūntes further strengthens the case for understanding the inscriptions in the context of multiple interacting communities, as this formula elsewhere is a fairly generic term that can in fact refer to mixed groups of people. Comparanda using this formula number 147 inscriptions from 61 different places (, ),Footnote28 including 27 instances where the term appears in the Dorian form (τοὶ κατοικεῦντες) on Rhodes, its peraia and nearby places (e.g. Karpathos, Knidos, and Kos).Footnote29 Application of the Ionian form, used on Ikaria, is spread chronologically between the end of the fourth century BCE and the fifth/sixth century CE, and occurs predominantly in the Aegean islands and western Anatolia. The formula is employed frequently to refer to Athenians and Romans among other groups dwelling on Delos; thirty-two percent of the dataset originates from Delos during the second and early first centuries BCE – i.e. after the island had been named an Athenian colony in 167/6 BCE,Footnote30 and its force is to refer often collectively to Athenians, Romans, and all foreigners or Hellenes living on the island ().Footnote31 In this light, the term is used to refer not only to those in direct and indirect control over Delos (Athens and Rome, respectively), but also to those inhabiting the island. This reading of the formula can also apply to the Samians on Ikaria. After the Athenians and Romans, the Samians were the most mobile group followed by the Lerians, offering strong evidence that the Samians were a highly mobile community who took up residence in places such as Ikaria.

Table 3. Count of inscriptions using the ‘οἱ κατοικοῦντες’ residency formula, indicating in each instance which (if any) named groups are specified on the inscription.

Furthermore, that the Samians apply terms like these in other (non-Ikarian) contexts also invite one to exercise caution. In an honorific decree dating to the late fourth century BCE (the first known use of the term), the Samians living in exile in Iasos (οἱ κατοικοῦντες Σαμίων̣ ἐν Ἰασῶι) offer their thanks to two citizens of Iasos for their services whilst the Samians were exiled from the island by the Athenians; the decree was enacted by the Samian boulē and dēmos after the exile had ended and the decree was set up in the Heraion of Samos.Footnote32 The formula at its earliest use, therefore, was not associated with Samians as the agents of imperialism, but rather Samians as the victims of it.Footnote33 What is more, the only secure context that allows for the assignment of political control to groups who define themselves as hoi katoikoūntes is when they are epigraphically mentioned as the enactors of decrees. We have already seen two examples in which the Samians in Oine and Minoa (Amorgos) were able to deliberate with the formula “edoxen” (ἔδοξεν) (Appendix no. 1; IG XII 7, 240), discussed above.Footnote34 Further examples, however, are few and far between. On the island of Lipsoi during the second century BCE, for instance, both “the citizens dwelling in Lepsia” (ἔδοξε τῶν πολιτῶν τοῖς κατοικο[ῦσιν] ἐν Λεψίαι) and “the Milesians dwelling in Lepsia” (ἔδοξε Μιλησί̣ων τοῖς κατοικοῦσιν ἐν Λ[ε]ψί̣αι) were able to enact decrees,Footnote35 as were the Lerians dwelling on Leros.Footnote36 Overall, only 6 of the 182 examples of the formula “X on Y”, or “the people of X living in Y” can be used as explicit evidence of X having political control over Y. In other cases, literary evidence might provide information on whether X had colonized Y and so on; this is the case for the 10 references to the Athenians dwelling on Delos or the three references to the Athenians on Lemnos.Footnote37 Otherwise, there is no secure precedent to use residency formulas as evidence of political control or power; they are merely evidence of presence.

It is prudent, then, to turn back to issues of chronology. In the traditional narrative of Robert and others, the second century BCE is seen somewhat as a “watershed” moment, and a transformation on the state of affairs. Previously, in the fourth century BCE, the Ikarians themselves are seen to have had the power to make political declarations, granting the proxeny; but by the second century they were not the main political actors on the island. The need to see this shift is motivated by Strabo’s note that Ikaria was inhabited at one point; and so it is understood that those who had the power to grant decrees had left Ikaria, and that those who moved in with new political powers were the Samians. This narrative, however, over-emphasizes the importance both of the proxeny decree and of the Oine inscriptions while not taking a wider view of other evidence. First, the Samian political presence on Ikaria cannot be universal. In Drakano in the first century CE, a decree is made (IG XII 6, 2, 1285) in the name of the dēmos – not the Samians, not the Samian dēmos, but (presumably) the local dēmos. Either Drakano was so deeply under the thumb of the Samians that it did not even need stating that it was the Samians making this decree, or they simply were not here. Second, the Samians are elsewhere, and their relationship with these other places is apparently different to their relationship with Oine. Relevant to decrees made to individuals on Rhodes (IG XII 1, 149), Kos (IG XII 1, 150) and in Magnesia on the Meander (IG XII 1, 154), all dating between the fourth and second centuries BCE, it is the boulē and the dēmos of Samos who enact the decrees – not simply the Samians in residence. It is only in Minoa on Amorgos, also of the Hellenistic period, where one sees both the “Samians residing in Minoa of Amorgos” and the “dēmos of the Samians living in Minoa of Amorgos” (IG XII 7, 226, 231, 237, 239, 240). Why, then, could the Samians on Ikaria make decrees all by themselves without the boulē or dēmos, unless they were a remote community working alongside the dēmos of Oine?Footnote38 Third, perhaps a weaker point but still worth articulating, is that the formula used is indicative of a residency rather than of a particular control: we do not hear of the Samians exontes tēn nēson (possessing the island, ἔχοντες τὴν νῆσον). In any case, the grand moment of change between the fourth and second centuries does not have to be viewed so starkly in Oine.

Furthermore, one might ask why (and why not) there was motivation for this sudden control over Ikaria in the second century BCE. That there was a “gap” in the occupation of Ikaria that prompted Samians to repopulate the island seems somewhat improbable: there is a long, continuous and almost unbroken record of funerary inscriptions from Oine between the fifth century BCE right through to the fourth century CE that confutes the argument for a period of abandonment. Either that period was so brief that it fails to show up in the epigraphic record, but just happens to coincide with the time of Strabo’s comments, and the island continued to be used as a funerary space when not otherwise occupied (unlikely or perhaps unprecedented); or, there simply was no long gap in occupation for Ikaria. This last supposition seems the most tenable, since the narrative about a break in occupation comes solely from Strabo, whose testimony is in question: it remains unclear whether Strabo ever actually visited the island and was giving an eye-witness description of the Ikarian state of affairs. Furthermore, the late Hellenistic and early Roman settlement structure of the island cannot be properly determined, given the absence of any extensive or intensive archaeological research. Robert himself warned against tying Strabo and the epigraphic record too closely together, even though Strabo’s work is generally accepted as “evidence” for Samian control of Ikaria.Footnote39 But even supposing there was a break in occupation of the island and the Samians decided to move in and take it over, what was their purpose? The simple answer would be for territorial expansion. The case of Samos and its peraia has already been raised, but this was not a unique arrangement in the ancient world. In the eastern Aegean, at various times Samothrace, Tenedos, Lesbos, Chios, and Rhodes used off-island territories within their network,Footnote40 necessitating frequent short-range trips either between islands, or between the “home” island and the mainland. It might be that Ikaria provided an alternative to the peraia when this territory came under threat – but this seems quite a stretch, and remains mere theory in the absence of further substantive evidence. But this model does not have to imply permanent residency, and in fact is better suited to the short-range high-frequency mobility that was discussed above. Why would a community of Samians require permanent residency on Ikaria if their only motivation for taking the land was for trans-humance? The “Samians on Ikaria”, therefore, might be more a question of “Samians [who are at some points of the year] on Ikaria”, liable to frequent movement between their home polis and Ikaria as a remote territory.

What is the implication for a community of Samians resident on Ikaria? There is at least the political dimension of these inscriptions: namely, what do they tell us about the political functions performed by Ikaria and Samos? Oine of the second century BCE did not have a tradition of making decrees; the only decree, as noted above, is the proxeny decree from 200 years earlier, and the only decree by an Ikarian dēmos comes from Drakano. Similarly, there is no tradition on Fournoi, where the only example of a decree (in the second century BCE) is made by the Samians (IG XII, 6, 2, 1203). That is to say, there is not a tradition of epigraphic habit on Ikaria until the Samians arrive at Oine. The decrees (Appendix, nos. 1 and 2) are indicative of the capacity of the Samians to pass laws and modify the physical fabric of Oine. Likewise, the ability of the Samians on Ikaria to erect honorific inscriptions for the emperors (3–7) indicates that there were some people residing on Ikaria who were prosperous enough to set up honours and that they wished to display their collective loyalty to imperial figures.Footnote41 By contrast, as noted above, there is an extensive and deep epigraphic tradition of making decrees on the part of the Samians inhabiting Samos, a tradition that goes back even to the start of the third century BCE.Footnote42 That is, it is far more usual to see Samians than Ikarians issuing decrees and honorific statues. Might the examples from Oine, then, simply be a case of the Samians having a longer and more impressive history of epigraphic habit and publication, and that it is that tradition brought to Ikaria in erecting these stones? To put this another way, this set of inscriptions could be read not simply as indicative of the movement of people between Samos and Ikaria (however temporary or permanent), but a transfer of practices, and of Samians and Ikarians coexisting alongside one another, and performing something more conventionally Samian in practice.

This also suggests something about the status of Ikaria’s political units and of their relationship with Samos. In terms of the collective political activity, on the one hand there is one group (the Samians) coming from a named polis who are prolific in dedicatory activity, and another group (the Ikarians) whose named polis (Oine) does not habitually do these sorts of things. Crucially, then, we see a “spectrum” of different polis-type activity, and that when the Samians put up inscriptions on Ikaria they were invoking language indicative of certain demotic functions that this particular community would not normally perform. Ironically, then, it is not just a case of there being another group present on Ikaria, but that this group was more likely to leave traces of its presence through the fabric of political activity. The alternative (although not mutually exclusive) is that the presence (or knowledge) of a Samian community was inspiring an epigraphic tradition, that those in Oine took to codify their political activities in stone, upon the example of their Samian neighbours. That the activity of one community could be motivated through interaction with or knowledge of another is not a new suggestion for the late Hellenistic and Roman periods,Footnote43 and in fact this sort of Peer Polity Interaction (PPI) provides a useful model for making sense of what could be happening in the east Aegean area. It has already been posited that the area around Samos and Ikaria was a microcosm of connectivity, with highly mobile individuals and groups moving between and beyond the islands: PPI relies on the notion of a pre-existing mobility, and the preconditions here provide the perfect laboratory for groups who would learn from and compete with one another.

On these various accounts, then, whether using linguistic, contextual, or historical comparanda, there is sufficient room to interpret the formulas discussed above under the second reading, “the Samians [one group of many on Ikaria] living in Oine”. In doing so, one might propose that there was short-range mobility between the islands of Ikaria and Samos in the late Hellenistic and early Roman periods, with wider implications for how Samos and Ikaria, first separately and then together, performed various political functions as indicated by their epigraphic habits.

4. Conclusions

This article has sought to understand more about the relationship between Samos and Ikaria in the late Hellenistic and early Roman periods. Previous scholarship in this area has assumed the inclusion in seven inscriptions of a certain formula that declares the presence of “Samians on Ikaria” to refer to a control by or migration of Samians to Ikaria, occurring some time before the first century BCE. In our view, a closer analysis of this epigraphic formula across the Aegean world suggests that although these inscriptions could be read as indicative of a unilateral relationship between Samians and Ikarians, it might merely connote the presence of different groups inhabiting the island. We have attempted to offer an additional reading of these inscriptions by suggesting that they could just as easily speak to short-range frequent mobility between Samos and Ikaria. The significance of this alternative reading is that it allows greater room for considering difference in the extent to which Samos and Ikaria performed polis-like functions, and that mobility permitted Samians to perform more “Samian” type activities in an “Ikarian” space. Furthermore, the people from Samos, by naming themselves as “Samians who live on Ikaria”, were distinguishing themselves from other groups and choosing to identify themselves in a specific way. Crucially, then, we suggest that the “Samians who live on Ikaria” were not necessarily the only people living on Ikaria at this time, and that, even though the only group who chose to explicitly identify themselves by name, they were not the sole enactors of civic or religious power on the island.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Christy Constantakopoulou, Stephen Lambert, Alex Mullen, and Graham Shipley for thoughts and discussions related to this topic, and for reading through drafts of this paper at various stages.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthew P. Evans

Matthew P. Evans is a Teaching Fellow in Greek History at the University of Warwick and is the incoming Richard Bradford McConnell Student at the British School at Athens. His research interests broadly concern the social and cultural history of the Hellenistic and Roman Aegean, and he has participated in various archaeological projects in Greece and Italy. Matthew’s doctoral thesis analysed gymnasia as a lens through which to explore the interplay between identity and the built environment in postclassical Greece and especially how this was impacted by macro-regional political shifts.

Michael Loy

Michael Loy is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Cambridge and a former Assistant Director of the British School at Athens (2019–2022). Michael’s research on the history and archaeology of Archaic and Classical Greece investigates routes, networks, mobility, and connectivity between maritime and terrestrial communities, largely employing GIS-based methods and tools from the Digital Humanities. He is co-director of the West Area of Samos Archaeological Project.

Notes

1. For a general discussion of this period, see Shipley, A History of Samos, 182ff; and Papalas, Ancient Icaria, 115–116.

2. Athenaeus 2, 57. For “Ikarian type” transport amphoras see Reynolds, “Trade Networks”, fig. 6j.

3. On insularity, territory, and island networking more generally throughout Mediterranean history and in different periods, see Broodbank, An Island Archaeology; Broodbank, The Making; Constantakopoulou, Dance of the Islands; Dawson, “Maritime Connectivity”; Horden and Purcell, The Corrupting Sea; Kolodny, La population; Kowalzig, “Cults, Cabotage, and Connectivity”; Malkin, A Small Greek World, 65–96; Reger, “Political History”; Sweetman, Devlin and Pirée Iliou, “The Cyclades”; Talbot, “Separating the Waters”.

4. Papalas, Ancient Icaria, 134; Bougatsou, “Οικιστική ιστορία της Ικαρίας”, 64–65 and others have suggested that a small council met here to make decisions of local importance, while the most important civic business would be conducted on Samos.

5. Stamatiadis, Ikariaka, 22–23. See also Evangelidis, “Άνασκαφαὶ καὶ ἔρευναι”, 45 on a description of Roman inscriptions found in the vicinity of Byzantine remains.

6. Politis, “Ἀνασκαφαί ἐν Ἰκαρίας”, with further work in the area conducted by Zafeiropoulos, Chatzianastasiou, Zapheiropoulou, and others as documented variously in the ADelt Chronika: 36 (1981): 378–379, 37 (1982): 360, 38 (1983): 348, 39 (1984): 295, 43 (1988): 501–503, 52 (1997): 946–949, 56–59 (2001–2004, B6): 38–44, 63 (2008): 1122.

7. The earliest phase for these buildings is given as the first century CE, but for the most part the architecture of what remains is dated much later.

8. This material was variously mentioned, discussed, and studied since the early nineteenth century (cf. Matthaiou, “Οι επιγραφές της Ικαρίας”, 145–146. The publication of these inscriptions in Inscriptiones Graecae XII was handled by Angelos Matthaiou (see also Matthaiou, “Aus der Arbeit”), and the most recent commentary and study by Angelos Matthaiou and Georgios Papadopoulos, Επιγραφές Ικαρίας).

9. Shipley, A History of Samos, 205–207; Papalas, Ancient Icaria: 119–120; Constantakopoulou, Dance of the Islands, 180–182.

10. Robert, “Les Asklepieis de l’Archipel”, 431–433.

11. It is also suggested that Therma was refounded as Asclepieis in the third century BCE as a gesture indicating that the settlement was “under new management” by the Samians.

12. Hiller von Gaertringen, Inschriften von Priene, 37: 115. See also the general discussion in Shipley, A History of Samos, 31–37.

13. Liddell and Scott, Liddell and Scott, 86, 367, 477. Casevitz, Le Vocabulaire, 161 gives as the general meaning for κατοικέω “occuper un territoire … κατοικεῖν est volontiers employé pour des individus, des peuples ou des fractions de populations qui résident […] s’installent, provisoirement ou définitivement, en un lieu où ils viennent à la suite d’un départ en exil notamment”. More generally for a κατοικία (164): “celle d’établissement, lieu où est établie une population: ensemble de maisons, village, localité”. Taking the sense of the word literally under this definition, it is clear to see why unilateral political control by the Samians is an attractive option.

14. Cf. commentary of migration as a paradigm in Anthony, “Prehistoric Migration”; Burmeister, “Archaeology and Migration”.

15. Lambert, “What was the Point”, 204.

16. Matthaiou and Papadopoulos, Επιγραφές Ικαρίας, 86–87. This must remain tentative since, as they admit, the findspot was not directly stated.

17. It is certainly preferable to avoid taking ἀποίκων in a sense of “colonisation”. The word apoikia is well known from the Archaic period for designating Greek settlements overseas (Welwei, “Apoikia”; Bernstein, “Relations with Homelands”), but by the late Hellenistic times the term could be applied to anyone who settled abroad. The term appears in 51 inscriptions dating between the mid fifth century BCE and mid-second century CE found primarily in both Attica and Asia Minor, though examples are also found in the western Mediterranean in Sicily.

18. “Frequent and shorter-term movements across variable, often shorter, distances.” Mokrišová and Kotsonas, “Mobility, Migration, and Colonization”, 218. See also van Dommelen, “Moving On”.

19. Cf. Arnaud, Les routes; Beresford, Ancient Sailing Season; Leidwanger, “Modeling Distance”; Morton, The Role.

20. Cf. Churchill Semple, The Geography, 580–582.

21. Campbell and Koutsouflakis, “Aegean Navigation”.

22. Jurriaans-Helle, Cornelis de Bruijn; van der Vin, Travellers to Greece, 13–18.

23. It should be noted that there are concerns raised regarding the authenticity of this inscription, with Robert noting that it is a possible forgery on the basis that no physical copy can be located (see IG). Cf. Amorgos of the Hellenistic period, where different groups appear to be present in the different poleis: Samians in Minoa (IG XII 7, 226, 231, 237, 239, 240; on which see further below), Milesians in Aigiale (IG XII 7, 395–410), and Naxians in Arkesine (IG XII 7, 50).

24. On expressing collective identities in the ancient world and on association of a group with a persistent identity, see for example Mac Sweeney, “Beyond Ethnicity”; Morgan, “Ethnic Expression”; Demetriou, Negotiating Identity, 8–14; Mullen, Southern Gaul, 4–5.

25. IG II2 275 = IG II3 1, 501 (ca. 336/5 BCE); IG II2 672 = IG II3 1, 884 (279/8 BCE); IG II2 3467 = Dēmos Rhamnountos II 9 = SEG 49.144 (third/second cent. BCE); Schweigert, “Two Third-Century Inscriptions”, 338 = IG II3 1, 885 = SEG 38:74 (280/279 BCE); SEG 22:127 = IG II2 1288+1219 = I.Eleusis 191 (ca. mid-third cent. BCE); Pouilloux, La Forteresse de Rhamnonte 15 = SEG 25.155 (236/5 BCE); Pouilloux, La Forteresse de Rhamnonte, 8 = IG II2 3467 (300–100 BCE); IG XII 6, 2, 1217 (ca. 200–150 BCE).

26. On the Athenian capture of Lemnos: Herodotus 6.136; Cornelius Nepo, Miltiades 1–3; Diodorus Siculus 10.19.6. On the Athenians in the Chersonese: Herodotus 6.140.

27. Pouilloux, La Forteresse de Rhamnonte, 15 = SEG 25:155.

28. Only 142 of the inscriptions come from geographically known places (58 places in total); it is to be noted that this dataset includes partially reconstructed inscriptions.

29. These date between the beginning of the second century BCE and the mid second century CE. For a discussion of examples from Syme, see Constantakopulou, “Beyond the Polis”, 226.

30. See Roussel, Délos, colonie athénienne, for general discussion on Delos in the second century.

31. Inscriptions de Délos (ID) 1642, 1646, 1650, 1652. 1653, 1656, 1671, 1672, 1673, 1674. There are cases where “Athenians who live on Delos” are distinguished from “Romans who reside on Delos” (ID 1970: Ἀθηναίω[ν οἱ κατοικοῦντες καὶ Ῥωμαίων?] οἱ παρεπιδ[ημοῦντες ἐν Δήλωι?]; see also ID 1643, 1647, 1648, 1649, 1665, 1677).

32. IG XII 6, 1, 17, ll.18–19. The inscription is discussed in Errington, “Samos”, 53; Shipley, A History of Samos, 162.

33. And yet it is the assumed force of hoi katoikoūntes as indicating direct control that has been used to argue the case for Samian dominance on Amorgos and Corsiae.

34. Another example is IG XII 7, 239, ll. 1–4.

35. McCabe, Lepsia Inscriptions, no. 2 and 3. The latter inscription was found on the nearby island of Patmos.

36. McCabe, Leros Inscriptions, no. 3.

37. On the Athenians on Delos, see Polybius 30.20.1–2, 7. On the Athenians on Lemnos, see above n. 26.

38. For examples from Samos decreed by the boulē and dēmos, see IG XII 6, 1, 11; 16; 23; 24; 27; 29; 37; 46; 51; 62; 63; 65; 82; 95; 119; 146. For just the dēmos, IG XII 6, 1, 12; 122; 130; 154; 252. For the dēmos, under the resolution of the prytaneis (ἔδοξεν τῶι δήμωι, γνώμη πρυτάνεων), IG XII 6, 1, 6, 14; 118; 154. There are two anomalies, IG XII 1, 6, 133 is decreed by the aleiphomenoi from the senior’s palaistra (ἔδοξεν τοῖς ἀλειφομένοις ἐν τῆι γεροντικῆι παλαίστραι) and IG XII 6, 1, 132 is decreed by the members of the thousand lesser Epidaurians (ἔδ[οξεν τ]οῖς χιλιαστῆρσι Ἐπιδαυρί̣ων̣).

39. “Elle avait perdu son indépendance, s’était dépeuplée, mais il ne faudrait pas, en prenant à la lettre la terme ἔρημος ou en forçant le mot λειπανδροῦσαν, employés par Strabon, qui d’ailleurs n’avait pas visité l’île, pas plus que Samos, croire qu’elle était inhabitée; ce serait ne pas vouloir connaître les épitaphes de l’époque impériale, la liste d’éphèbes qui date précisément de l’époque de Strabon et la dédicace des habitants de l’île à l’empereur Antonin.” Robert, “Les Asklepieis de l’Archipel”, 432.

40. See Funke, “Peraia”, and a more recent discussion of the evidence in Constantakopoulou, Dance of the Islands, 231–245. The notion of off-island territory for expanding agricultural activities is a sensible one; the choice of Ikaria is rather more curious. As a particularly rocky and difficult to traverse island with less overall cultivable area than Samos, Ikaria – although highly convenient for its proximity – would not have provided its neighbours with substantially more usable territory than if they had looked elsewhere. The basin around Oine provides one of the flattest and most fertile areas across the whole of Ikaria, and it would therefore be the most suitable location for such a purpose.

41. It is well documented that groups residing in a city or on an island but not having political control (or even the rights to engage in political activity) made honorific dedications both within sanctuaries and poleis in the late Hellenistic and Imperial periods, on which see Bruneau and Bordreuil, “Les Israélites de Délos”; Dillon and Baltes, “Honorific Practices”, 208. So the mere presence of these honorifics is not enough to suggest that Samians enjoyed political control on Ikaria at the time they were erected.

42. IG XII 6, 1, 1 (dated 285 BCE) for the first decree from the Heraion. IG XII 6, 1, 9, as an honorific, is possibly from as early as the fourth century BCE.

43. On the roots of Peer Polity Interaction (PPI) see Renfrew and Cherry, Peer Polity Interaction. See also Ma, “Peer Polity Interaction”, Michaels, “The Spread of Polis Institutions”, and Renfrew, “Introduction”.

44. See SEG 49-1162, 53-888.

45. See SEG 53-890.

Bibliography

- Anthony, David. “Prehistoric Migration as Social Process.” In Migrations and Invasions in Archaeological Explanation, edited by John Chapman and Helena Hamerow, 21–32. Oxford: Archaeopress, 1997.

- Arnaud, Pascal. Les routes de la navigation antique: itinéraires en Méditerranée. Paris: Errance, 2005.

- Beresford, James. The Ancient Sailing Season. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

- Bernstein, Frank. “Relations with Homelands: Apoikia and Metropol(e)is.” In A Companion to Greeks Across the Ancient World, and Franco De Angelis, 499–512. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- Bougatsou, Ioanna. “Οικιστική ιστορία της Ικαρίας στους ιστορικούς χρόνους.” In Η aρχαιολογική σκαπάνη στην Ικαρια. Εβδομήντα χρόνια ανασκαφικής έρευνας και μελλοντικές προοπτικές, and George Koutsouflakis, 49–78. Athens: Festival Ikarias, 2010.

- Broodbank, Cyprian. An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Broodbank, Cyprian. The Making of the Middle Sea: A History of the Mediterranean from the Beginning to the Emergence of the Classical World. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Bruneau, Philippe, and Pierre Bordreuil. “Les Israélites de Délos et la juiverie délienne.” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 106 (1982): 465–504.

- Burmeister, Stefan. “Archaeology and Migration: Approaches to an Archaeological Proof of Migration.” Current Anthropology 41, no. 4 (2000): 539–567.

- Campbell, Peter, and George Koutsouflakis. “Aegean Navigation and the Shipwrecks of Fournoi: The Archipelago in Context.” In Under the Mediterranean I. Studies in Maritime Archaeology, edited by Stella Demesticha and Lucy Blue, 279–298. Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2021.

- Casevitz, Michel. Le vocabulaire de la colonisation en grec ancien. Paris: Klincksieck, 1985.

- Churchill Semple, Ellen. The Geography of the Mediterranean Region: Its Relation to Ancient History. London: Constable, 1931.

- Constantakopoulou, Christy. The Dance of the Islands: Insularity, Networks, the Athenian Empire, and the Aegean World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Constantakopoulou, Christy. “Beyond the Polis: Island Koina and Other Non-polis Entities in the Aegean.” In Communities and Networks in the Ancient Greek World, edited by Claire Taylor and Kostas Vlassopoulos, 213–236. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Dawson, Helen. “Caught in the Current: Maritime Connectivity, Insularity, and the Spread of the Neolithic.” In Revolutions. The Neolithisation of the Mediterranean Basin: The Transition to food Producing Economies in North Africa and Southern Europe, edited by Joanne M. Rowland, Giulio Lucasini, and Geoffrey J. Tassie, 85–100. Berlin: Edition Topoi, 2021.

- Demetriou, Denise. Negotiating Identity in the Ancient Mediterranean: The Archaic and Classical Greek Multiethnic Emporia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Dillon, Sheila, and Elizabeth Palmer Baltes. “Honorific Practices and the Politics of Space on Hellenistic Delos: Portrait Statue Monuments Along the Dromos.” American Journal of Archaeology 117 (2013): 207–246.

- Errington, Robert Malcolm. “Samos and the Lamian War.” Chiron 5 (1975): 51–58.

- Evangelidis, Dimitris. “Άνασκαφαὶ καὶ ἔρευναι ἐν Σκύρῳ.” ADelt 4 (1918): 34–45.

- Funke, Peter. “Peraia: Einige Überlegungen zum Festlandbesitz Griechischer Inselstaaten.” In Hellenistic Rhodes: Politics, Culture, and Society, edited by Vincent Gabrielsen, 55–75. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 1999.

- Hiller von Gaertringen, Friedrich Freiherr. Inschriften von Priene. Berlin: Habelt Verlag, 1906.

- Horden, Peregrine, and Nicholas Purcell. The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

- Jurriaans-Helle, Geralda. Cornelis de Bruijn: Voyages from Rome to Jerusalem and from Moscow to Batavia. Amsterdam: Allard Pierson Museum, 1998.

- Kolodny, Emile Y. La population des îles de la Grèce: essai de géographie insulaire en Méditerranée orientale. Aix-en-Provence: Édisud, 1974.

- Kowalzig, Barbara. “Cults, Cabotage, and Connectivity: Experimenting with Religious and Economic Networks in the Greco-Roman Mediterranean.” In Maritime Networks in the Ancient Mediterranean World, edited by Justin Leidwanger and Carl Knappett, 93–131. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Lambert, Stephen. “What was the Point of Inscribed Honorific Decrees in Classical Athens?” In Sociable Man: Essays on Ancient Greek Social Behaviour, edited by Stephen Lambert, 193–214. Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, 2011.

- Leidwanger, Justin. “Modeling Distance with Time in Ancient Mediterranean Seafaring: A GIS Application for the Interpretation of Maritime Connectivity.” Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013): 3302–3308.

- Liddell, Henry George, and Robert Scott. Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged: Original Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Ma, John. “Peer Polity Interaction in the Hellenistic Age.” Past & Present 180 (2003): 9–39.

- Mac Sweeney, Naoíse. “Beyond Ethnicity: The Overlooked Diversity of Group Identities.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 22 (2009): 101–126.

- Malkin, Irad. A Small Greek World: Networks in the Ancient Mediterranean. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Matthaiou, Angelos. “Aus der Arbeit der “Inscriptiones Graecae” V. Zwei Dekrete aus Ikaria.” Chiron 29 (1999): 225–231.

- Matthaiou, Angelos. “Οι επιγραφές της Ικαρίας.” In Η αρχαιολογική σκαπάνη στην Ικαρια. Εβδομήντα χρόνια ανασκαφικής έρευνας και μελλοντικές προοπτικές, edited by Ioanna Bougatsou and George Koutsouflakis, 145–151. Athens: Φεστιβάλ Ικαρίας, 2010.

- Matthaiou, Angelos, and Georgios Papadopoulos. Επιγραφές Ικαρίας. Athens: Ellenike Epigraphike Etaireia, 2003.

- McCabe, Donald. Lepsia Inscriptions. Text and List. Princeton: Institute for Advanced Study, 1985.

- McCabe, Donald. Leros Inscriptions. Text and List. Princeton: Institute for Advanced Study, 1985.

- Michaels, Christoph. “The Spread of Polis Institutions in Hellenistic Cappadocia and the Peer Polity Interaction Model.” In Shifting Social Imaginaries in the Hellenistic Period: Narrations, Practices and Image, and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, 283–307. Boston: Brill, 2013.

- Mokrišová, Jana, and Antonis Kotsonas. “Mobility, Migration, and Colonization.” In The Wiley Companion to the Archaeology of Early Greece and the Mediterranean, edited by Irene Lemos and Antonis Kotsonas, 217–246. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2020.

- Morgan, Catherine. “Ethnic Expression on the Early Iron Age and Early Archaic Greek Mainland: Where Should we be Looking?” In Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity, edited by Ton Derks and Nico Roymans, 11–36. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009.

- Morton, Jamie. The Role of the Physical Environment in Ancient Greek Seafaring. Leiden: Brill, 2001.

- Mullen, Alex. Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Papalas, Anthony. Ancient Icaria. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 1992.

- Politis, Linos. “Ἀνασκαφαί ἐν Ἰκαρίας.” Πρακτικά της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας (1939): 124–155.

- Pouilloux, Jean. La forteresse de Rhamnonte. (Étude de topographie et d’histoire.) Paris: De Boccard, 1954.

- Reger, Gary. “The Political History of the Kyklades 260–200 B.C.” Historia 43 (1994): 32–69.

- Renfrew, Colin. “Introduction: Peer Polity Interaction and Socio-Political Change.” In Peer Polity Interaction and Socio-Political Change: New Directions in Archaeology, edited by Colin Renfrew and John Cherry, 1–18. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Renfrew, Colin, and John Cherry. Peer Polity Interaction and Socio-Political Change: New Directions in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Reynolds, Paul. “Trade Networks of the East, 3rd to 7th Centuries: The View from Beirut (Lebanon) and Butrint (Albania) (Fine Wares, Amphorae and Kitchen Wares).” In LRCW3: Late Roman Coarse Wares, Cooking Wares and Amphorae in the Mediterranean. Archaeology and Archaeometry. Comparison between Western and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Simonetta Menchelli, Sara Santoro, Marinella Pasquinucci and Gabriella Guiducci, 89–114. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2010.

- Robert, Louis. “Les Asklepieis de l’Archipel.” Revue des Études Grecques 46 (1933): 423–442.

- Robert, Louis. “Les Asklepieis de l’archipel.” Opera Minora Selecta I (1969): 549–568.

- Roussel, Pierre. Délos, colonie athénienne. Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1987.

- Schweigert, Eugene. “Two Third-Century Inscriptions.” Hesperia 10, no. 4 (1941): 338–341.

- Shipley, Graham. A History of Samos 800–188 BC. Oxford: Clarendon University Press, 1987.

- Stamatiadis, Epameinondas. Ikariaka. Samos: Egem, 1893.

- Sweetman, Rebecca, Alice Devlin, and Nefeli Pirée Iliou. “The Cyclades in the Late Antique period. Churches, Networks and Christianization.” In Cycladic Archaeology: New Approaches and Discoveries, edited by Erica Angliker and John Tully, 215–238. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2018.

- Talbot, Michael. “Separating the Waters from the Sea: The Place of Islands in Ottoman Maritime Territoriality during the Eighteenth Century.” Princeton Papers: Interdisciplinary Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 18 (2018): 61–86.

- Van der Vin, Jos. Travellers to Greece and Constantinople: Ancient Monuments and Old Traditions in Medieval Travellers’ Tales. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul, 1980.

- Van Dommelen, Peter. “Moving On: Archaeological Perspectives on Mobility and Migration.” World Archaeology 46 (2014): 477–483.

- Welwei, Karl-Wilhelm. “Apoikia.” In Brill’s New Pauly, edited by Hubert Cancik and Helmuth. Leiden: Brill, 2006. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e127690.

Appendix

1. IG XII 6, 2, 1217; Matthaiou and Papadopoulos Citation2003, no. 47; Matthaiou Citation1999, 228–231, fig. 2: Honorary Decree of the Samians in Oine for Eparchides; marble stele; first half of second century BCE.Footnote44 In the Archaeological Museum of Kampos (inv. no. 232).

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

1 – – – – . Ο̣ἴ̣νη̣ν, στῆσ[αι δὲ αὐτοῦ τὴν εἰκόνα]

[ἐν τῆι ἀγ]ορᾶι ἐν ἐπιφανε̣[ῖ τόπωι ἔχουσαν]

ἐπι̣γραφὴν τήνδε v »Σάμ[ιοι οἱ οἰκοῦντες Οἴνην]

ἐτίμησαν Ἐπαρχίδην Α– – – – – – – – – – – –

5 χρυσῶι στεφάνωι, εἰκόνι χ[αλκῆι ἀρετῆς ἕνεκα]

καὶ εὐνοίας τῆς εἰς ἑαυ̣τ[ούς·« ἀναγράψαι δὲ]

τὰ δεδογμένα εἰς στή[λην λιθίνην καὶ στῆσαι]

ἐν τῆι ἀγορᾶι παρὰ τὴν ε[ἰκόνα· τῆς δὲ ἀνα]–

γραφῆς καὶ τῆστάσεω[ς τῆς στήλης καὶ τῆς ἀνα]–

10 θέσεως τοῦ ἀνδριά[ντος ἐπιμεληθῆναι τοὺς]

νεωποίας Γοργοσ– – – – – – – – – – – – – –,

Μητροφῶντα Θε – – – – – – – – – – – – – .

vacat

Translation:

- – -

1 – - – Oine, to place his statue

in the agora in a prominent position bearing

the following inscription: “The Samians inhabiting Oine

honoured Eparchides A- – -

5 with a golden wreath (and) bronze statue for the sake of his excellence

and goodwill towards them”, and to engrave

what was decided on a stone stele and place it

in the agora next to the statue; the engraving

and the installation of the stele and the

10 erection of the statue shall be taken care of by the

neopoioi Gorgos- -,

Metrophon The- -

vacat

2. IG XII 6, 2, 1218; Matthaiou and Papadopoulos Citation2003, no. 1, pl. 2 and 3: Honorary Decree of the Samians in Oine for Timesileos; marble pedimental stele; after 133 BCE.Footnote45 In the Archaeological Museum of Kampos (inv. no. 239).

1 [ἐπ]ὶ̣ δημιουργ[ο]ῦ Θεοδώρο̣υ τοῦ Δημητρίου, στεφα–

[νη]φόρου δὲ v Τ[ι]μησίλεω, Ταργηλιῶνος διχομηνίᾳ,

[ἔδ]ο̣ξεν Σαμίοις τοῖς κατοικοῦσιν Οἴνην· vac. Ἐπει–

[vac.] δ[ὴ] Τιμησίλεως Μητροφῶντος, φύσει δὲ Διη–

5 – –ς̣ ἀ̣πὸ τῆς πρώτης ἡλι[κίας] τῶν ἀρίστων ζη–

[λωτ]ὴ̣ς γεγενημένος ἔν τ[ε τοῖ]ς λοιποῖ[ς] καλὸς

[κ]α̣ὶ̣ ἀ̣γαθὸς ὑπάρχων διετέλει [κ]αὶ λέγων vacat

[κ]αὶ πρ̣άσ<σ> ων ἀεὶ τὰ συμφέροντα π̣ᾶσιν ἡμῖν κατ̣ὰ

κ̣ο̣ινὸν καὶ κατ᾿ ἰδίαν v στε[φ]αν̣[η]φόρος τε γενόμ̣<ε>–

10 νος αὐθαίρετος διὰ τοῦ ἐνι̣[αυ]τοῦ ἦρξε[ν] ἴ̣σ̣[ω]ς

[καὶ φι]λ̣αγάθως vac. ἱκεσίαν τ[ε ἐπι]τελέσας τῆι [Ἀρ]–

τέ[μ]ιδι τῆ[ι] Ταυ[ρ]οπόλωι ὑπ–3–4–ξ̣ατο παν–3–4–

[τοὺς] πολίτας καὶ τὰς π[ολίτιδ]ας καὶ τὰ τ[έκνα]

– – – 10–11– – – Σ[.]ΛΙΣΠΑΡΕΣ[. .]ΛΟ[. .]ΟΙΠΑΣ v θα–

15 – – 5–6– – Τ[.]Σ– – – Σ δυ[…]Α[…]Ν[…]ΑΝ δη–

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – καὶ Ε– –

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΩΠ– – – – – – – ΠΡ– –

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΩΤ– – – – – – Ε– –

– – – – – – – – – – – οὐθὲν [.]Δ[…]ΤΟΥ– – – – – – –

20 – – – – – – – – – – [. .]ΥΣΩΝ ἱκεσ[ί]α̣ν [. .]ΣΑΙΝ– –

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΚΙΑΙ[. .]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Λ . ΣΠΟ[. .]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Ο̣Υ̣ΚΛΕΙ[. .]

[– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – φι]λαγάθω̣ς

25 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΤΡΑΝΕ– –

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΥΠ[.]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Ω[.]ΝΡ[.]

[– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – δρα]χμὰς̣

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Τ..ΗΝ[.]

30 [– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – δ]ραχμαῖς̣

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Α[…]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΕΚ[…]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΕΠ[. .]ΝΗΙ

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

35 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Ε[. .]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΝΑΣ[.]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΠΑ[. .]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – . […]

40 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΣΥ̣Γ[… .]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΜΕΤΑ

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ι καὶ στεφα–

[νῶσαι? – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –]ΔΕΔ[. .]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Ε^ΟΛ̣ΗΝΙΡΜ̣[.]

45 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Ο̣ΙΝΝΝΥΛΟ

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ΣΛΧΕ[…]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – ?– – – – – – – – – – – – –

Translation:

1 Under the demiourgos Theodoros son of Demetrios, the stepha-

nephoros of Timesileos, in Targelion at the full moon.

The Samians dwelling in Oine decided: Since

Timesileos son of Metrophon, natural son of Die-

5 – -, has been from early youth a zealot for the best

and has always been fine and good in other respects

in deed and word,

and always acting in the interest of all of us

collectively and individually; and becoming stephanephoros,

10 he voluntarily officiated throughout the year in a fair

and righteous manner; and when he hosted a procession to Ar-

temis Tauropolos, undertook the reception of all

the (male) citizens, (female) citizens and children

- – -

- – -

Lines 16–46 weathered except for small remains mentioning supplication (l. 20) and sums of drachmas (l. 29 and 30).

3. IG XII 6, 2, 1219: Honorary inscription for the emperor Augustus; marble column; 27 BCE-CE 14. Possible forgery; see IG.

1 Σαμίων ἀποίκων

Ἰκαρίας

Αὐτοκράτορι Καίσαρι

4 Λέριοι πανδημεί.

Translation:

1 (Of the) Samian settlers

on Ikaria

to the emperor Caesar

4 the Lerians as a whole

4. IG XII 6, 2, 1220; Matthaiou and Papadopoulos Citation2003, no. 3, pl. 6.2: Honorary inscription for the emperor Nerva; marble circular base; CE 96–98. In the Archaeological Museum of Kampos (inv. no. 396).

1 Σάμιοι οἱ κατοικοῦν–

τες Εἰκαρίαν vacat

Αὐτοκράτορι Καίσαρι

4 Νέρουᾳ Σεβαστῶι

Translation:

1 The Samians dwelling

on Ikaria

to the emperor Caesar

4 Nerva Augustus

5. IG XII 6, 2, 1221; Matthaiou and Papadopoulos Citation2003, no. 4, pl. 7: Honorary inscription for the emperor Hadrian; marble profiled circular base; shortly after CE 117. In the Archaeological Museum of Kampos (inv. no. 397).

1 Σάμιοι οἱ ἐν Εἰκαρίᾳ

κατοικοῦντες τῷ

μεγίστῳ Αὐτοκράτορι

Τραϊανῷ Ἁδριανῷ, θεοῦ

5 Τραϊανοῦ υἱῷ, θεοῦ Νέρβα

υἱωνῷ, ἀρίστῳ Καίσαρ[ι] Σε{β̣α̣}–

βαστῷ Γερμανικῷ Δακικῷ

Παρθικῷ, σωτῆρι καὶ κτίστῃ.

Translation:

1 The Samians who dwell on Ikaria

to the

greatest emperor

Traianus Hadrian, son of divine

5 Traianus, grandson of divine Nerva,

the best Caesar Augustus

Germanicus Dacicus

Parthicus, the saviour and founder.

6. IG XII 6, 2, 1222; Matthaiou and Papadopoulos Citation2003, no. 5, pl. 8.1: Honorary inscription for the emperor Antoninus Pius; marble base; CE 138–161. In the Archaeological Museum of Kampos (inv. no. 400).

1 Σ̣άμιοι οἱ κατ̣[οικοῦντες Εἰκαρίαν]

Αὐτοκράτο̣ρα̣ [Καίσαρα Τ(ίτον) Αἴλιον Ἁ]–

δ̣ριανὸν Ἀντω[νῖνον Σεβαστὸν Εὐσεβῆ].

4 vacat

Translation:

1 The Samians dwelling on Ikaria

(honour) the emperor Caesar Titus Aelius Ha-

drianus Antoninus Augustus Pius

4 vacat

7. IG XII 6, 2, 1223: Honorary inscription for the emperor Antoninus Pius; marble column; CE 138–161.

1 Σάμιοι οἱ ἐν Ἰκαρίᾳ κατοικοῦντες

[…]ΤΟΥΝΑΟΥ Αὐτοκράτορ<ι>

Καίσαρι [Τί]τῳ Αἰλίῳ

Ἁδριανῷ Ἀντωνίνῳ

5 Σεβαστῷ Εὐσεβεῖ.

Translation:

1 The Samians dwelling on Ikaria

- – - (honour) the emperor

Caesar Titus Aelius

Hadrianus Antoninus

5 Augustus Pius.