Abstract

In Eveline Hasler’s novel on Henry Dunant, the founder of the Red Cross, she mentions ‘Wilhelm Sonderegger, teacher’ from Heiden/Appenzell, Switzerland. Sonderegger lived in the second half of the nineteenth century and taught gymnastics (Turnen) at school to increase the pupils’ physical activity. He also gave an inspiring speech at an assembly of Swiss gymnastics teachers in 1904, but passed away shortly thereafter at only 42 years of age. The methodology of Alain Corbin (The Life of an Unknown) is used to reconstruct the life of Wilhelm Sonderegger – starting with his death – and to discover how Sonderegger contributed to improving physical education in the Swiss school system in a rural area where it was commonly believed that children got enough physical activity by making hay or mucking out the barn. The approach chosen here of a detailed description helps to highlight the special features of the region and the living conditions found there. The topic of physical education, which this paper addresses, and the health of male adolescents and their preparation for the military through regular physical exercise, were topics that were also discussed across national borders in the second half of the nineteenth century as a result of the impact of industrialization and the military conflicts throughout Europe. The Appenzeller Zeitung contains articles by people from Munich who took a stand on this issue. These were not critically commented on by the Appenzeller Zeitung, the only publishing body in the region, as they were in line with its own arguments. The paper examines the influence of the pedagogical approaches of Swiss educator, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, Johannes Niggeler, the father of Swiss gymnastics, and the effects on the pupils in the Appenzell region. An analysis of Sonderegger’s articles in the Appenzeller Anzeiger provides us with additional microhistory. The aim of this paper is to highlight the uniqueness of the situation in Appenzell, and to explore it from an ethnological perspective.

In her novel on Henry Dunant, founder of the Red Cross, Eveline Hasler mentions ‘Wilhelm Sonderegger, teacher’ from Heiden/Appenzell, Switzerland.Footnote1 Sonderegger lived in the second half of the nineteenth century and, according to Hasler, wrote articles for the Appenzeller Zeitung on topics such as gymnastics (Turnen) at school.Footnote2 He also submitted a pedagogical study at the World’s Fair in ParisFootnote3 and gave an inspiring speech at an assembly of Swiss gymnastics teachers in 1904 in Herisau, Switzerland. Shortly thereafter, he passed away at only 42 years of age.Footnote4

Was the Sonderegger in the novel invented by Hasler to act as a fictive conversational partner for DunantFootnote5 in order to illustrate in a more socially critical way his final years in Heiden? Or did Sonderegger really exist? To reconstruct the life of Wilhelm Sonderegger, the methodology presented by Alain Corbin in The Life of an Unknown is used to uncover the microhistory of physical education in the Swiss school system in the nineteenth century as well as gymnastics in Switzerland.Footnote6 Which game-changing ideas did Sonderegger bring to education in a rural area where it was widely held that children would receive enough physical activity by making hay or mucking out the barn?Footnote7

Initial Meeting

Sonderegger is a typical Swiss surname and Wilhelm, as a first name, is also not out of the ordinary. An initial search query produced an image of Wilhelm Sonderegger entitled ‘senior civil servant’ (not teacher or journalist), however the dates do correspond to the person in question. In The Life of an Unknown, Alain Corbin searched for traces and interpreted these very carefully on the basis of research. He reconstructs the life of a person he has chosen at random from a church register for which little concrete information can be found. He bases this on vital statistics, the presumed living conditions, and the documented mortality rates at the time. The name of the unknown to be researched is the central theme in the everyday story that is processed. The contextualizations are sometimes dense and descriptive down to the smallest detail with the intention of giving contour to the passage of time and the life of the unknown.

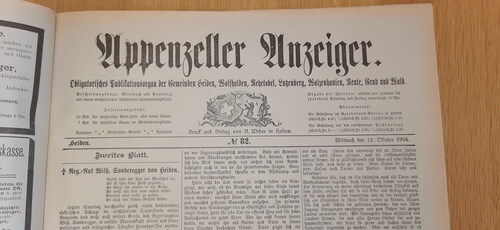

The second piece of evidence was taken from Hasler’s novel. She mentions that Sonderegger wrote articles for the Appenzeller Zeitung. According to the author, he had promised in July 1887 or 1888 to write an article on physical strengthening at school. The source is consistent with the existence of a paper with such content. Founded in 1828, the Appenzeller Zeitung was regarded as the boldest paper in all of Switzerland, so this is plausible. However, in 1877 the Appenzeller Anzeiger was launched directly in Heiden. Therefore, it is more likely that Sonderegger used the editorial office in his hometown, particularly as the Appenzeller Zeitung had changed its area of distribution and was regarded at that time as a product of Herisau (like Heiden, a municipality in Switzerland). At the time, the Appenzeller Anzeiger was issued on a bi-weekly basis (on Wednesdays and Saturdays). It provided brief reports on international and regional news in accordance with its mission of being an ‘obligatory publication organ of the districts of Heiden, Wolfhalden, Reute, Walzenhausen, Grub and Wald’ ().

After his sudden death following a stroke, an epitaph for Sonderegger was published in the Appenzeller Anzeiger on 10 October 1904:Footnote8

Senior Civil Servant W. Sonderegger of Heiden was born on 16 May 1862 in Berneck/CH. He died on 4 October 1904 in Heiden. He was married and a father of eight children. In 1878 he successfully completed his teacher’s training in Kreuzlingen; his first appointments as a teacher were in Schwändi-Glarus and Buchs. From 1887–1898 he worked as a teacher in a primary school in Heiden. Since 1898 Sonderegger was an elected member of the local council and section chief in charge of the civil status office. In 1900 he was appointed senior civil servant.

Wilhelm Sonderegger was not only a teacher and journalist, but also the senior civil servant in the picture.

Method

An analysis of Sonderegger’s articles in the Appenzeller Anzeiger, in conjunction with the recollections of Susanna Sonderegger-Rhyner,Footnote9 provides enough microhistory to become cognisant of the uniqueness of the situation in Appenzell and to explore it ethnologically, focusing on health enhancing physical activity at the end of the nineteenth century in Switzerland. All issues of the Appenzeller Anzeiger, starting from October 1904 (the death of Sonderegger) back to 1887, were examined for articles written by Wilhelm Sonderegger and other sources which described life and the challenges relating to education, health enhancing physical activities, gymnastics and pedagogical discussions. The aim was to create a picture of the life of a teacher in Appenzell and to gather basic information about physical education in the nineteenth century in a rural part of Switzerland.

Instead of working chronologically, special topics act as jigsaw pieces: the World’s Fair, the influence of the pedagogy of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, Johannes Niggeler, the father of Swiss gymnastics, and the pupils and people living in the Appenzell region.Footnote10 Nearly all of the articles in the paper were published anonymously, with the authors not even being identified by their initials. Some articles could be spotted because Sonderegger was mentioned, others because of their feuilleton style, unusual for this paper, but typical for Sonderegger’s writings. It is obvious that his activities as a journalist were formative for his life and his career.

He delighted the readers with much chit-chat, flavoured with golden humour and charming images. At the same time he offered instruction and clarification in his political articles, written with a fine vision and sharp logic. Sonderegger had an extraordinary journalistic streak and if he would have concentrated on this area exclusively, he most definitely would have made a significant contribution.Footnote11

Instead, he worked as a teacher and a journalist, first shaping opinion unintendedly, then later on as a local politician. Concentrating on Sonderegger as a journalist, and not only as a teacher, helps to broaden the limits of micro-historical knowledge.

Teacher Training, Reading Societies and the Parlour

Wilhelm Sonderegger, son of a farming family, was educated at a teacher’s seminar in Kreuzlingen for three years. When he entered the seminar in 1875, a new democratic social order had already brought about a step change in education: Liberal civic society worked towards increasing national education by reforming rural schools, which were no longer run by the Church, but by the state. The aim was to secure a new order of citizens who could read rules and fill in election ballots. The constitution of Thurgau, ratified on 26 April 1831, states ‘It is the duty of the state to ensure the improvement of public education.’ All children, boys and girls equally, should receive a secularized primary education at school. In line with this postulation, new and better-educated teachers were in high demand. The education act from 1833 issued the following directive for the new role and function of a teacher: ‘Art. 56. A school teacher is regarded as a servant of the state. Therefore, it is his role and duty to promote, to the best of his knowledge, an understanding of the conditions of general welfare, religiousness and morality, and to impart a love of nation and the fatherland.’ Following this decree, the newly elected education council initiated the founding of a teacher’s seminar. This opened on 12 November 1833 and initially had 27 male boarders.

When Sonderegger began practicing his profession in the 1880s, it was common to teach in one school room, with children divided by age into classes. He taught using special methodically orientated books and worked from a compulsory syllabus, imparting knowledge that society deemed to be important. Despite an awareness of the pedagogy of Pestalozzi,Footnote12 teaching was mostly done ex cathedra. Subjects at primary schools were religion, reading, writing and singing. Mathematics and physical activity were not mentioned, despite the philanthropists Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi promoting the idea of bringing physical education into schools. Both emphasized that physical education should be fostered so that individuals could acquire useful skills and be of greater benefit to the community. These notions were already being propagated at the turn of the nineteenth century.Footnote13

Sonderegger was highly regarded as a teacher and educator of youth, as the Appenzeller Jahrbücher describe in retrospect.Footnote14 The teacher seemed to be highly motivated, had a positive attitude, and knew how to create attractive lessons for his pupils. The children trusted him and shared their observations and adventures with the beloved educator.Footnote15 He even did experiments with his pupils and presented the results at the World’s Fair in Paris.

The 1889 World’s Fair in Paris

In his dual role as a journalist and a contributor, Sonderegger was given the chance to go to Paris and visit the World’s Fair.Footnote16 The World’s Fair, also called Exposition Universelle Internationale or Exposition Mondiale (Expo), was an international exhibition, established during the industrial age as a competitive technical and arts & crafts exhibition. Taking place one hundred years after the French Revolution, the 1889 World’s Fair was special.

The Exposition Universelle de 1889 raised the bar in nearly every respect. Despite a few teething problems, because of a rampant fear of revolution, 61,722 exhibitors from 54 nations and 17 French colonies took part and more than 32 million visitors came.Footnote17 The extraordinary success can be attributed to a good balance between education and entertainment. … The magnificent spectacle was an elegant and bright incantation of liberalism and its economic pendant, capitalism.’Footnote18

Sonderegger received a gold medal at the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris for his pedagogical work an expertise on the mental capabilities of pupils using illustrative examples. On its way back from Paris, this work went missing.Footnote19

As a teacher, Sonderegger was paid by the canton– no longer by parents –, was employed full time, and worked the whole year.Footnote20 By 1870, compulsory schooling was generally accepted and the process of education in society was further advanced.Footnote21 By then, a modern and holistic educational system was more or less successfully established in most of the cantons in Switzerland.Footnote22 The Federal Factory Act, passed in 1877, prohibited children under the age of 14 from working in factories, and supported schooling.Footnote23 However, creating a law does not necessarily mean that attitudes change. In 1904, two generations after the law was introduced, an article was published on children working in home industry while mandatorily attending school, and other sorts of occupation in the canton of Appenzell.

Based on 125 reports from 128 schools and an additional 200 essays on the topic ‘What did I do yesterday’, he could report on 8,510 children. All in all, 63.9% of boys and 72.8% of girls worked on a daily basis in home industry and other sorts of occupations. 31.6% of these children worked more than six hours a day. If you add together compulsory schooling and working hours, this amounts to up to 81 hours per week!Footnote24

In response to these findings, a law protecting children was passed. However, this worked against the traditional, commonly held opinion in this rural area that children acquired enough physical activity through farm work. By 1887, though probably earlier than that, but not published in the paper,Footnote25 Sonderegger had tried to make the case for integrating more physical activity and physical education into the Swiss school system.

Sonderegger was first employed in Sevelen (St. Gallen), then in Schwändi (Canton Glarus), later returning to Buchs in the Rhine Valley. Early in 1887 he was visited by a delegation from the school commission of Heiden and was appointed to teach at the primary school (Unterschule) in Heiden. As a boarder in Kreuzlingen, Sonderegger was taught and shaped by other teachers. It was also obligatory to join a reading society, where people with different views gathered to discuss general subjects as well as to exchange ideas on recent political topics. Members also provided important impetus for political and cultural life as well as for the common welfare in their community. With lectures and a circulating reading folder, they fostered comprehensive education. Reading societies generally kept their distance from political parties and regarded themselves as being politically neutral and not following any ideology. They were a forum for discussion, education and socialising. All in all, their function was to build public opinion and were very common at that time in Europe. Four were located in Heiden, where Sonderegger taught: Dorf, Brunnen, Untern und Bissau.Footnote26 He might have been a member of one or more.

Sonderegger and his wife also offered something akin to a parlour, where well-known people came to visit the family. Conversing in German or French, it broadened the participants’ intellectual world and their views on life. Sonderegger-Rhyner mentions, for example, General Hans Herzog, Eli Ducomun, Dr. Becker, Dr. Bolmi, Mrs. Gertrud Villiger-Keller, Mr. Randegger (founder of the well-known cartographic institute) and J. Henry Dunant, ‘the best teacher’ of Sonderegger.Footnote27 Dunant chose Sonderegger to translate his book Un souvenir de Solférino into German.

The young patriot Wilhelm Sonderegger,Footnote28 tainted with the benefit of impartiality and democratic belief, burdened with the disadvantage of problems and constraints growing out of the conditions, this Swiss of a strong heavy step and a soft heart, of a harsh language and a fluent, capricious mind was just right for the knowing old man, to be a megaphone and tool of his will.’Footnote29

Dunant wrote in one of his letters to Sonderegger ‘Social aristocrats are needed, and you have to be one of them, a true aristocrat of intelligence.’Footnote30 Sonderegger was a politically active citizen, spreading his opinion in public discussions, through his journalistic work and, most likely through the reading societies, which can be seen as the forerunners to the dominating liberal movement in Switzerland. ‘The school parlour was too narrow for the active mind and therefore the educator of youth became – little by little – an educator of the public. Through his whole work there was a tendency towards high aims; small-mindedness was strange to him.’Footnote31

It was primarily the young, rural elites who fought for the success of the French Revolution and who, in 1894, founded the liberal party that Sonderegger was a member of.

For the majority of his working life, Sonderegger was active in Heiden.

Where is Heiden?

Heiden is situated in Appenzell/Canton Aargau, 400 metres above Lake Constance (810 metres above sea level). The lowest point in Heiden lies at 470 metres, the highest at 1,030 metres.

Sonderegger descended from a dynasty in Appenzell, most of whom had been farmers who had tilled the same soil since the fourteenth century.Footnote32 While working as a teacher, he created a relief of the mountains of Säntis, followed – maybe with the support of his wife – by a larger relief of Appenzell made out of gypsum and paper with isohypses and elevations that were true to scale.Footnote33 More than half of the area of the municipality of Heiden was used for agriculture (grazing, dairy farming, viniculture, cereal crops). The textile industry was the largest employer in town (employing 71% of workers). In 1888, Heiden had 3,436 inhabitants; by 1900 the number had increased slightly to 3,745.

In 1859, before Sonderegger came to Heiden, the average age of women in Heiden was only 24; for men it was 25 and there was a high infant mortality rate. Information about health care is hard to find for Heiden in the first half of the nineteenth century. However, in the second half of that century there was a greater need for better health care and hence this was developed further. When Sonderegger began teaching in Heiden in 1887, its rise from a village to a major regional hub, which started in the 1860s, was at its height. Heiden had become one of the most famous spa towns in Europe. Medical services and, as a consequence, life spans increased due to the many external spa guests who were attracted by dairy treatments (whey cure). These included doctors like Albrecht von Graefe, a popular Berlin ophthalmologist, and Heinrich Frenkel, a neurologist. In addition, a district hospital was built in 1874, which was the first of its kind in the region of Ausserrhoden.Footnote34 Obviously, this development had an extremely positive influence on life spans, or as historian Johannes Huber, who is currently working on a history of Heiden Hospital, put it ‘A hospital is something like a church of health in the village.’Footnote35 The spa and tourism in Heiden – a transport hub since 1875, when the Rorschach-Heiden-Bergbahn connected Heiden to the Swiss railway system – contributed (necessarily) to securing primary health care. Heiden’s important status in the region was also reflected by the fact that it published its own newspaper, the Appenzeller Anzeiger, from 1877 onwards. It was here that Sonderegger contributed articles, however – strangely enough – not on the social conditions of his home region, but on geographical and seasonal matters.Footnote36

Gymnastics in Different Settings – Schools, the Military, Clubs

Johannes Niggeler, Switzerland’s ‘father of gymnastics’, instigated the idea of adding gymnastics, taught by specially educated teachers, to the school syllabus. However, the problem was that there were not enough trained teachers to do this. Thus, it was decreed by the Swiss Federal Council and written directly into the constitution. Even though cantons had sovereignty over education, all cantons had to adhere to this decree. Catholic and rural parts of Switzerland did not, however, meet these obligations. Attitudes towards health seemed to remain unchanged from the previous century, where instructions in schools included: ‘2. Health regulation. … Take care to do the following: get moderate daily exercise through work or other means.’Footnote37 The German privy councillor von Nußbaum (Munich) commented on gymnastics by saying:

that it has been a good idea to implement it as obligatory, however, at the moment the dose of this wonderful medicine is to be regarded as homeopathic, probably with little effect. I am convinced, that in the future you have to alternate daily physical activity with mental work, to keep a child healthy. In addition to that, I am convinced that learning would be easier if the body was strengthened more and if mental exertion did not take up so many hours as it does at the moment in nearly all educational institutions.Footnote38

In 1891 the Swiss military commented on gymnastics for male pupils and concluded that, in all cantons, schools were anxious to introduce compulsory gymnastics in order to achieve at least that which was possible.Footnote41 Federal funds for schools were to be used, first and foremost, for the infrastructure at schools to promote gymnastics, namely gyms, outdoor gymnastic grounds, and new gymnastics equipment.Footnote42 Meanwhile, the war (1870/71) in the second half of the nineteenth century strengthened the link between gymnastics and preparation for military service. Major Müller spoke about pre-military training on the Swiss Day of Gymnastics Teachers. He emphasized that

Pre-military training at school – one requirement of Art. 120 of the preliminary draft of a new army law of the Swiss military – is in keeping with the times.

Due to the resistance to compulsory education, a search is underway for a way to integrate free organizations that foster military education.

Here, the alliance will participate in two different ways: first by supporting voluntary gymnastics and shooting and, secondly, by testing physical capabilities, which every young Swiss has the duty to increase.Footnote43

Müller refers directly to a new publication, The Increase of Physical Capacities of Swiss Youth, where the author, infantry captain Arthur Steinmann (Herisau) concludes:

If civic schools and gymnastics clubs with their pre-military training develop and strengthen the young bodies in common work, they will not only achieve far more outstanding soldiers than before, but will create an army of healthy, powerful citizens, which will show, in an economic fight, such tough powers of resistance needed to guarantee the independence of smaller nations.Footnote44

The central committee of the federal gymnastics association firmly backed compulsory military service for every Swiss.

Only, if training started in adolescence on the basis of a high level of physical fitness could it increase during compulsory military service.

Gymnastics education at school has to be guaranteed and supported.

The physical education of adolescents between the end of school and the start of military service (from 16 to 20 years of age) has to be obligatory and implemented.

The examination of recruits has to involve physical fitness tests.

The central committee can already assure the federal authority that the federal gymnastics association will do everything in its power with joy and enthusiasm to implement the order and to see the eminent patriotic work through to fruition.Footnote46

Final Remarks – or Sonderegger’s Inspiring Speech

Returning to Sonderegger, his ‘inspiring speech’ at an assembly of Swiss gymnastics teachers in 1904 was published in the Appenzeller Anzeiger. Here he introduced himself in three different ways, describing himself as a representative of the school commission of the canton of Appenzell; president of a military commission; a gymnastics and weapons comrade. As the representative of the school commission, Sonderegger stated: ‘A harmonious education of adolescents is only possible if both mental and physical education are implemented to this effect. The education of the body had to fight long enough against the prejudice of what famous men, whose fame enlightened centuries, called an essential demand of a focused pedagogy.’Footnote47 Maybe Plüss is right when he says ‘gymnastic lessons at school were and are a reflection of the predominant ideals of society and a projection screen of how humankind has to be and live’, a reinterpretation of Billie Jean King’s remark that sports are a microcosm of society.Footnote48 In his role as the president of a military commission, Sonderegger remarked on the recent discussion on physical fitness of soldiers and summed it up in a very popular way, saying: ‘Each soldier should be a gymnast, each soldier also a gymnast and patriot. Let us stick to that!’ His remarks go back to Niggeler, co-founder of the Swiss gymnastics teachers association as early as 1858. With the slogan Jeder Lehrmann ein Wehrmann (every teacher is a soldier) he fought for compulsory military service for teachers.

Sonderegger was a person who did exist. He lived only for 42 years. However, he influenced public opinion in many ways in his home region of Appenzell – as a teacher, a journalist, and a politician. In his experience, ideas and decrees took ages to be put into practice. Finally, it can be concluded that the area or the canton in which one lives need not influence one’s actions or political decisions – one can be cosmopolitan, as Sonderegger himself was.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Swantje Scharenberg

Swantje Scharenberg studied Sports Science, Journalism and Ethnology at the Georg-August University in Goettingen, and received her PhD there in 1992. Her habilitation treatise (2006) was on sports heroes in the German press in the interwar period. She currently works as a Professor at the Institute of Sports and Sports Science at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in charge of the Research Center of Physical Education and Sports for Children and Adolescents (FoSS). She is president of the Fellows of CESH (European Committee for Sports History).

Notes

1 Eveline Hasler, Der Zeitreisende. Die Visionen des Henry Dunant [The Time Traveller: The Visions of Henry Dunant] (München: Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, 2018), 8.

2 Ibid., 17.

3 René Sonderegger, Jean Henry Dunant – Revolutionär! [Jean Henry Dunant – Revolutionary!] (Zürich: Reso-Verlag, 1935), 29.

4 Hasler, Der Zeitreisende [The Time Traveller], 32f.

5 Henry Dunand (May 8, 1828 in Geneva – October 30, 1910 in Heiden), who is considered the founder of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, lived in poverty in Heiden for around three decades. In 1901, he received the first-ever Nobel Peace Prize for his life’s work.

6 Alain Corbin, Auf den Spuren eines Unbekannten. Ein Historiker rekonstruiert ein ganz gewöhnliches Leben; aus dem Französischen von Bodo Schulze [On the trail of an unknown man. A historian reconstructs a completely ordinary life; translated from the French by Bodo Schulze] (Frankfurt/New York: Campus-Verlag, 1999).

7 Hasler, Der Zeitreisende [The Time Traveller], 17.

8 .

9 Susanna Sonderegger-Rhyner, ‘Erinnerungen an Jean Henry Dunant [Memories of Jean Henry Dunant]’, in Jean Henry Dunant – Revolutionär! [Jean Henry Dunant – Revolutionary!], ed. René Sonderegger, (Zürich: Reso-Verlag, 1935), 93–8.

10 ‘Then I have to give the reader some elements that allow him to recreate the possible and the probable: a sketch of the virtual history of the landscape, the personal environment and the mood, a draft of possible emotional states or conversation sequences, an imagination from the social ladder, viewed from below, or the way the memories may have been structured. We must always be aware that we will not know the slightest thing about the moral qualities of the chosen individual.’ (Corbin, Auf den Spuren eines Unbekannten [On the trail of an unknown man], 10).

11 Appenzellische Jahrbücher [Appenzell Yearbooks] 33 (1905), 209.

12 Sonderegger gave a lecture on Pestalozzi in 1896 (Appenzeller Anzeiger, 150th anniversary of Pestalozzi’s birth (January 12, 1746)), January 15, 1896.

13 Walter Mengisen in Mirko Plüss, ‘Kaum ein Schulfach hat sich so verändert wie der Sport [Hardly any school subject has changed as much as sport]’, Neue Zürcher Zeitung Magazin, 11 April 2023, https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/schulsport-in-der-schweiz-die-geschichte-des-turnunterrichts-ld.1779363 (accessed June 9, 2023).

14 Appenzellische Jahrbücher [Appenzell Yearbooks] 33 (1905), 208.

15 Susanna Sonderegger, ‘Ein Augenzeuge. Erinnerungen an Dunant von Frau Susanna Sonderegger, Heiden [An eyewitness. Memories of Dunant by Mrs Susanna Sonderegger, Heiden]’, Du. Schweizerische Monatsschrift ‘Das Rote Kreuz’, No. 8., August 1942.

16 Under ‘Letters from Paris’ Sonderegger started reporting on the World’s Fair in May 1889. His readers accompanied him as he walked through the exhibition and presented the different nations. He stayed there for several weeks.

17 Winfried Kretschmer, Geschichte der Weltausstellungen [History of the World Exhibitions] (Frankfurt: Campus-Verlag, 1999), 131.

18 J.H. Hall, ‘Paris 1889. Exposition universelle [World Exhibition]’, in Historical Dictionary of World’s Fairs and Expositions 1851–1988, ed. John E. Findling (Westport: Greenwood, 1990), 108–16, 115.

19 Sonderegger, Jean Henry Dunant, 29. Susanna Sonderegger (1942) mentions that the work had received an award, she did not speak of a gold medal.

20 According to Sonderegger-Rhyner, in 1892 he had an income of 1,600 SFR.

21 When the Helvetic state was dissolved in 1803, the cantons regained their educational policy independence. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, schools were built in the different hamlets of the community. Starting in 1805 school attendance up to year 13 was mandatory in some cantons. In 1822, a so-called Freischule was founded. All boys intelligent enough to join a secondary school were allowed to go there. To be accepted, they had to pass an exam. ‘The high number of children in the countryside and the tight finances of the municipalities did not allow gender-segregated classes. … Furthermore, boys and girls were assumed to have different intellectual abilities.’ (H.U. Grunder, Das Schweizer Primarschulsystem – Teil 2. (Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum, 2023), https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/2017/08/serie-das-schweizer-primarschulsystem-teil-2/). So the girls - instead of being sent to school - continued to contribute to the families’ income in agriculture and in the factories. It took until the liberal shift in the 1830s for the educational systems to be fundamentally renewed. In Appenzell Innerrhoden, for example, compulsory schooling was only enshrined in law in 1858, also in this year the provisorat was changed to a Realschule. In 1899, 771 pupils attended school in Heiden.

22 Speech, Monika Knill, 29 November 2008, ‘Ein Blick zurück: Aus der Geschichte der letzten 175 Jahre’, Chefin des Departements für Erziehung und Kultur, anlässlich der Feier zum 175-Jahr-Jubiläum der Thurgauer Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung und zur Einweihung der Neubauten des Campus [A look back: From the history of the last 175 years’, Head of the Department of Education and Culture, on the occasion of the celebration of the 175th anniversary of Thurgau teacher training and the inauguration of the new buildings on the campus]’ Bildung Kreuzlingen. https://monikaknill.tg.ch/public/upload/assets/19588/175%20Jahre%20LLB%20TG.pdf?fp=1.

23 Thomas Gull, ‘Kinderarbeit [Child labor]’, Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz, 9 März 2015, https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/013909/2015-03-09/ (accessed October 13, 2020).

24 Appenzeller Anzeiger, 28 September 1904.

25 Hasler, Der Zeitreisende [The Time Traveller], 17. Sonderegger had been asked to write an article on the matter of physical activity at school for the Appenzeller Zeitung. Neither in the Appenzeller Zeitung nor in the Appenzeller Anzeiger could this article or others written by Sonderegger on the matter of physical education be found.

26 Arthur Oehler, ‘Die öffentliche Meinungsbildung – Lesegesellschaften und Parteien [Public opinion formation – reading societies and parties]’, in Heiden: Geschichte von den Anfängen bis ins 21. Jahrhundert. Heiden: Vom einfachen Hof zur Zentrumsgemeinde, ed. David Aragai, Thomas Fuchs, Johannes Huber, Arthur Oehler, Stefan Rothenberger, Stefan Sonderegger (Schwellbrunn: Appenzeller, 2022), 186–93.

27 Sonderegger-Rhyner, Erinnerungen an Jean Henry Dunant [Memories of Jean Henry Dunant]’, 93.

28 Sonderegger gave a public speech on patriotism, published in the Appenzeller Anzeiger on April 3, 1889.

29 Sonderegger, Jean Henry Dunant, 31.

30 Ibid., 30.

31 Priest Altweg in the funeral sermon, Appenzeller Anzeiger, October 15, 1904.

32 Sonderegger, Jean Henry Dunant, 29.

33 The creation of the relief may have been motivated by Johannes Randegger, often a guest at Sonderegger’s home and a publisher of school maps. The relief, publicly presented in a chalet in Heiden, was not only a special point of interest in Heiden, but a shining example of contemporary topographic work (Sonderegger, Jean Henry Dunant, 29).

34 When the hospital opened in 1874, 15 patient beds were on offer and health care was conducted exclusively by one maidservant and one servant. Regular reports of the year were published in the Appenzeller Anzeiger e.g. June 22, 1889 for the year 1888.

35 Elia Fagetti, ‘Spitalgeschichte. “Ein eigenes Spital ist so etwas wie eine Kirche der Gesundheit im Dorf”: Über die historische Bedeutung des Spitals Heiden [Hospital history. “A private hospital is something like a church of health in the village”: On the historical significance of the Heiden Hospital]’, Appenzeller Zeitung, May 25, 2021. https://www.appenzellerzeitung.ch/ostschweiz/appenzellerland/spitalgeschichte-ein-eigenes-spital-ist-so-etwas-wie-eine-kirche-der-gesundheit-im-dorf-ueber-die-historische-bedeutung-des-spitals-heidens-ld.2131618.

36 Stefan Sonderegger, ‘Zu Fuß von Heiden nach Ragatz [On foot from Heiden to Ragatz]’, Appenzeller Anzeiger, August 25, 1888.

37 N.N., Lesebuch für die Jugend in Schulen und Haushaltungen. Mit Bewilligung der Obern (von Pfarrer Schiefs) [Reading book for young people in schools and households. With the permission of the superiors (from Pastor Schiefs)], (Gedruckt zu Trogen in der Sturzeneggerischen Buchdruckerei, 1789), 99.

38 Johann Nepomuk von Nußbaum, ‘Körperliche und geistige Arbeit im Gleichgewicht [Physical and mental work in balance]’, Appenzeller Anzeiger, May 4, 1887.

39 Appenzeller Anzeiger, July 29, 1896.

40 Appenzeller Anzeiger, October 31, 1888.

41 Appenzeller Anzeiger, December 16, 1891.

42 Appenzeller Anzeiger, May 18, 1904.

43 Appenzeller Anzeiger, October 8, 1904.

44 Appenzeller Anzeiger, October 22, 1904.

45 N.N., ‘150 Jahre Turnen im Appenzellerland – Appenzellischer Turnverband [150 years of gymnastics in Appenzellerland – Appenzell Gymnastics Association]’, 2012, 13. https://www.yumpu.com/de/document/read/4694782/150-jahre-turnen-im-appenzellerland-appenzellischer-turnverband.

46 Appenzeller Anzeiger, May 18, 1904.

47 Speech, Stefan Sonderegger, October 1904, at the Assembly of Swiss Gymnastics Teachers.

48 Plüss, ‘Kaum ein Schulfach hat sich so verändert wie der Sport [Hardly any school subject has changed as much as sport]’.