Abstract

The use of martial arts in Japan’s cultural diplomacy, as well as the history of Japanese martial arts in Norway, remain underexplored. Despite its peripheral status in Japan’s cultural diplomacy, Japan actively influenced Norwegian judo from 1945 to 1980 by dispatching instructors and ‘goodwill’ judo delegations to Europe. These visits aimed not only to promote judo but also to align the international development of judo with Japan’s own martial arts discourse and cultural diplomacy strategies. In 1965 and 1968 the delegations worked to cement judo’s status as a modern Olympic sport while reinforcing the image of ‘New Japan’ – a nation that is peaceful, democratic and economically strong. In 1979 and 1980 similar delegations sought to secure a Japanese presidency in the International Judo Federation, while highlighting judo’s traditional cultural roots as a form of self-defence and character development. This discursive shift paralleled Japan’s economic rise and the growth of nihonjinron – a discourse affirming Japan’s unique culture. The Norwegian judo community adopted the sports discourse, but largely rejected the orientalised nihonjinron discourse.

The decades following World War II arguably marked one of the most successful applications of sports diplomacy, when in 1964 the Tokyo Olympics helped rebrand Japan as a modern, democratic, and peaceful nation. One key aspect of this transformation was the reimagining of judo, a martial art that had been associated with warfare and fascist indoctrination, as an international Olympic sport. Judo became a symbol of ‘New Japan’ and a valuable tool in Japan’s cultural diplomacy.Footnote1 However, once accepted into the Olympics, judo was assimilated into Western sporting traditions.Footnote2 Judo’s globalization, and the tension between sportification and nationalism have received much scholarly attention.Footnote3 In the last decade the role of martial arts in Japan’s cultural diplomacy has also been investigated, albeit to a lesser extent.Footnote4 Yet, these studies often concentrate on large, influential states with robust diplomatic ties with Japan or substantial Japanese diasporas. This was the exception, not the rule. For a more comprehensive understanding of judo’s globalization and Japan’s contribution, it is imperative to explore judo’s dissemination in smaller, more ‘peripheral’ states. Norway is apt for such a ‘case study’ as it was not the primary target of Japan’s cultural diplomacy, yet still welcomed several ‘goodwill’ judo delegations between 1945 and 1980, which invariably also toured other countries, particularly in Northern Europe – illuminating an aspect of Japan’s ‘martial arts diplomacy’ left unexplored. Moreover, the case also highlights what might be called the ‘indirect cultural diffusion’ of judo that occurred when actors from the USA, Britain, and France brought their own interpretations of judo to Norway.Footnote5

Scholarly attention on the development of Japanese martial arts in Scandinavia remains rare, with the studies of Hans Bonde on the development in Denmark, being noteworthy exceptions.Footnote6 While Japan is acknowledged in works on Norwegian foreign policy, and its influence on art and architecture has been analyzed, there is a marked deficiency of research on the historical relationship between Norway and Japan. Eldrid Mageli’s commissioned work commemorating a century of diplomatic ties between the two nations, stands as a rare exception.Footnote7 The development of Japanese martial arts in Norway, as well as Japan’s cultural diplomacy towards the country, thus remains largely unexplored.Footnote8

Another advantage of using Norway in such a study is the state’s policy to ‘digitalize everything’ in its National Library, including newspapers, books, journals and more (a collection henceforth referred to as NB.no).Footnote9 Navigating this expansive database presents challenges. An initial search for ‘judo’ and ‘jujutsu’ (and variants of these terms), as well as related ‘karate’, ‘budo’, and ‘bushido’ returned nearly 80,000 hits in more than 350 different newspaper titles between 1945 and 1990. The newspaper which yielded the most results (Aftenposten, 5,385) was singled out for a preliminary analysis, wherein all hits were examined. Aftenposten’s high hit rate should not (necessarily) be attributed to a greater interest in judo, but rather to its status as a regional paper for Oslo, where judo developed in post-war Norway. Additionally, NB.no includes both Aftenposten’s morning and afternoon editions, effectively doubling the likelihood of hits. For comparison, Arbeiderbladet, a labour paper for Oslo, yielded the second highest number of hits, 3,125. Still, political biases cannot be ruled out. Before the 1980s, Norway had a party press system in which most newspapers were patronized by a political party, and although Aftenposten was an ‘independently conservative’ newspaper from 1963, it was still closely aligned with the Conservative Press Agency (Høyres Pressebyrå) and the Conservative Party (Høyre).Footnote10 To avoid a conservative and Oslo-centric bias, all hits in ‘journals’ at NB.no (3,569 hits, in everything from scientific journals to weekly magazines, from all parts of the political spectrum) were also examined. Then the remaining Norwegian newspapers were consulted by sorting for the twenty most ‘relevant’ articles that mentioned ‘judo’ or ‘jujutsu’ each year using Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (tf-idf). This process yielded a total of 940 articles, representing 1.3 per cent of approximately 70,000 hits. ‘Relevance’ in this context refers to articles with the highest frequency of the search terms, often indicating either longer articles or those delving deeper into the subject.Footnote11 The Norwegian Judo and Martial Arts Federations archives, including minutes, reports, and magazines, were examined alongside relevant resources from the Olympic Library in Lausanne, such as the IOC Bulletin, minutes, and the correspondence between the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the International Judo Federation (IJF). Specific events and periods of Japan’s cultural activities in Norway were further investigated, with dates and names cross-referenced in Swedish and Danish newspaper databases. This amounted to an overview of the dissemination of judo in Norway, as well as how it figured into Japan’s cultural diplomacy.

Judo in Japan’s Cultural Diplomacy

Cultural diplomacy is a form of public diplomacy that aims to influence foreign audiences and increase a country’s soft power by leveraging its culture. Thus, movies, music and sports, can all be used to communicate values and influence opinions, which in turn might increase a state’s ability to get what it wants ‘through attraction rather than coercion or payments’.Footnote12 The goal of cultural diplomacy is to align the way a state is perceived abroad with its intended image, which requires careful consideration of how the state and its culture are represented in foreign discourses.Footnote13 Unlike traditional diplomacy, public diplomacy is ‘an unofficial, indirect, and dialogic diplomacy, practiced by mixed coalitions of governmental, intergovernmental, and nongovernmental actors’.Footnote14 This indirect approach allows governments to take risks in cultural exchanges and maintain control while appearing uninvolved. However, the lack of direct government control over popular culture, such as sports and martial arts, means that the outcomes may not always align with the government’s desired policies. As a result, it can be challenging to discern a state’s strategic goals and cultural diplomacy efforts through such events. Nedejda Gadjeva, a researcher of international relations, argues that Japan’s cultural diplomacy is characterized by ‘scattered power’: the absence of a centralized agency and strategy to integrate the activities of public and private actors and facilitate their projects. Even so its two main actors can be said to be the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (MOFA) and the Japan Foundation (JF). JF was established by MOFA in 1972 and has since sent both scholars and artist on international tours to highlight the unique traditions of Japanese culture.Footnote15 Despite this ‘scattered power’, it is still possible to identify trends in Japan’s cultural diplomacy that hints to long-term strategies regarding judo.

Arguably, Japan’s use of judo can be divided into four phases. The first phase was characterized by Kanō’s personal citizen diplomacy, that resulted from his attempts to make judo ‘a modern, scientific sport that would reflect Western norms’.Footnote16 Judo was invented by Kanō during the 1880s, and from its conception it combined Japanese nationalism with the internationalism of sports.Footnote17 Kanō described judo as originating in older martial arts know as jujutsu (which he called ‘the old samurai art of fighting without weapons’).Footnote18 The semantic change from ‘-jutsu’ to ‘-dō’, was used to signalize that judō was a character-building tool for self-improvement, and not mere techniques for self-defence. These ideas were later integrated into other Japanese martial arts which collectively became known as budō. As with judo, they were often renamed with the suffix ‘-dō’ used to connote character development (i.e. kendō, karate-dō, and aikidō). Budō was closely associated with bushidō, an invented tradition that placed ‘the samurai ethic’ as a ‘defining aspect of the Japanese national character’.Footnote19 Kanō worked ceaselessly to internationalize judo, first by co-authoring an English article on judo in 1888, then by touring Europe, North America, China, and Africa between 1889 and 1938.Footnote20 During these tours he recruited emigrated Japanese jujutsu-teachers to the Kōdōkan, his own judo academy. Examples include Koizumi Gunji and Tani Yukio from London’s Budokwai, as well as Kawaishi Mikinosuke who settled in Paris. This laid the foundations for the European Judo Union. As the first Japanese member of the IOC, Kanō also lobbied for judo and kendo to become Olympic sports in the planned 1940 Tokyo Olympics.Footnote21

The second phase was during World War II, when judo was militarized and made mandatory for all Japanese students, and the bushidō-ethos reinvented to instil the students with a willingness to self-sacrifice for the nation.Footnote22 In this new discourse, which gradually took root during the early Shōwa era (1926–1945) international sports was reimagined as the antithesis of budō.Footnote23 The third phase came after Japan’s defeat, when the state’s history of imperialist aggression as well as its postwar constitution’s renunciation of military force, severely limited its options for ‘hard’ power after World War II. Instead, the government promoted the idea of ‘New Japan’: a peaceful modern, economically strong, democratic nation with long traditions and great natural beauty.Footnote24 A key part of this strategy revolved around distancing the ‘New Japan’ from its imperial past. As such the Japanese government also avoided direct references to ‘samurai spirit or feudal traditions’ and avoided directly promoting its national martial art internationally.Footnote25 Instead, tea ceremonies, flower arrangements, cherry blossoms and Mount Fuji were used to ‘demonstrate Japan’s serene and peaceful nature to the world’.Footnote26 In this new discourse budō was a remnant of wartime militarism. Under the direction of the United States-led Allied occupation, budō was banned from schools in 1945. To regain acceptance, Japanese martial artists downplayed the character-building aspects and sportified their practice. Thus, the discourse of martial arts shifted from militarization, towards one of competition, performance, and international sports.Footnote27 The Ministry of Education even banned the use of the term ‘budō’ in 1946 and replaced it with ‘kakugi’ (lit. ‘combat sports’) from 1958 to 1989.Footnote28 The 1964 Tokyo Olympics was used to great effect in the ‘New Japan’ strategy, as it allowed Japan to revive other traditional national symbols that were associated with the war, such as the emperor, the Rising Sun flag, the anthem, and the army, by representing them as symbols of peace.Footnote29 At the same time, judo was reinvented and presented as a peaceful, modern and international sport with ancient roots in Japanese culture. Judo’s transformation was compared to how the marathon had its origin on the battlefield but had since become a symbol of international peace.Footnote30

The fourth phase starts from the 1970s, when Japan had regained its international position by joining the United Nations (in 1956) and the OECD (in 1964) and by experiencing a massive economic growth (its GDP grew by an average annual rate of more than 10 per cent from 1950 to 1973).Footnote31 According to Gadjeva, the state had two new diplomatic strategies. The first was to ‘project an image of a technological and economically advanced nation’.Footnote32 The second strategy was to establish the uniqueness and exoticness of Japanese culture, in line with the hegemonic nihonjinron discourse, which was also used to explain Japan’s economic growth.Footnote33 Nihonjinron aims to explore and assert Japan’s distinct identity, often by contrasting Japanese culture with other cultures, particularly China or the West. Encompassing everything from popular literature to scholarly research, nihonjinron, or theories about the Japanese people and their national character, hinges on the assumption that Japan is a homogeneous nation with a uniformly shared culture.Footnote34 In this discourse bushidō and the Japanese martial arts were also used as explanations to Japan’s exceptionalism.Footnote35 Thus, from the 1970s, judo was once again presented as budō, self-defence and character-building, rather than merely an international sport.

International Influence on Norwegian Judo Before 1965

As a smaller North-European country, Norway was not a primary target of Japan’s cultural diplomacy. Japanese influence on Norwegian judo prior to 1965 was indirect, mediated through other European judo practitioners and books. Nevertheless, after signing the San Francisco Peace Treaty in September 1951, sport diplomacy helped strengthen the bonds between the two nations when, in February 1952, Japan was invited to the winter Olympics for the first time after World War II. Both on that occasion, and in 1957 as part of the opening of Scandinavian Airline’s ‘North Pole Route’ from Copenhagen to Tokyo, members of the Japanese royal family visited winter sports events in Oslo. The mutual establishment of embassies in 1958 and 1959 then set the stage for formal diplomatic normalization in 1962, as well as Japan’s cultural diplomacy in Norway, which was characteristically ‘scattered’.Footnote36

In 1962, Japan launched the Sakura Maru, a floating fair showcasing Japanese products and symbolizing its economic strength. The ship paid visits to Norway in 1964 and 1972, when Japan was hosting the Olympics. The Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) was the main promoter of Japan in Norway during the 1960s and 1970s, but from 1973, the Japan Foundation took over this role, employing art exhibitions and cultural emissaries to highlight Japanese culture.Footnote37 From 1959, ‘Japanese Days’ and ‘Weeks’ became popular means of promoting Japanese culture and goods, often facilitated by the Japanese embassy, JETRO, JF or other organizations with ties to Japan. These events played up traditional Japanese customs and aesthetics, leaning into Norwegian fascination with Asian cultures. ‘Geishas’, or kimono-clad women serving tea, became a regular feature of these events, catering to Norwegian’s Asiaphilic desires.Footnote38 By 1984 a Japanese immigrant in Norway lamented that the only things Norwegians associated with Japan was ‘samurais, geishas, electronics and the photo industry’.Footnote39

Despite judo’s absence in Japanese cultural diplomacy in 1950s Norway, the early development of Norwegian judo is best understood in an international context. In 1948, while Japan was occupied by the Allies, the European Judo Union (EJU) was established as the first international judo federation.Footnote40 However, Japan quickly followed suit. The All-Japan Judo Federation was founded in 1949, and in 1950 judo became the first martial art to be reinstated in the Japanese school system, after the Ministry of Education argued that it was ‘a modern, democratic sport’.Footnote41 Kanō Risei, son of Kanō Jigorō and president of the Kōdōkan, worked to regain control of international judo. At EJU’s meeting July 12, 1951, a letter from him was read aloud. In it, Kanō requested the Kōdōkan in Tokyo to be the headquarters of an international judo federation. In line with the ‘New Japan’-strategy, Kanō emphasized that the main purpose of such an international federation would be to promote and expand bonds of friendship between the member states. While this proposal was initially declined, the EJU was formally dissolved at the same meeting, and the International Judo Federation established in its place, to allow Argentina to join the federation.Footnote42 From November 1951, Kanō Risei spent three months on a diplomatic tour to visit the leaders of judo in the USA and nine Europe countries, to secure Kōdōkan’s control over the IJF.Footnote43 At the following IJF meeting August 30, 1952, Kanō was elected president. However, Kanō did not personally attend but was represented by ‘a diplomat acting on behalf of the Japanese Ambassador’, which suggest that the Japanese state had an interest in securing Japanese leadership in the IJF.Footnote44

Simultaneously, the Norwegian judo community took shape around Henrik Lundh, who had learned jujutsu in the Norwegian resistance movement during World War II. In 1951 Lundh’s group transitioned to the sport of judo by studying Charles Yerkow’s 1947 book Modern Judo. They also travelled yearly to Copenhagen to learn from a certain ‘Mr. Kringlebakk’. In Copenhagen they also secured judo manuals written by Kawaishi. In 1952 the Norwegians contacted London’s Budokwai, to improve their judo. This led Eric Miller, Budokwai’s secretary and a student of Koizumi Gunji, to visit Oslo in 1953 and 1954. Footnote45 While Kawaishi signed Norwegian judo graduation cards as early as in 1954, there was little direct contact between Norwegian and Japanese judo practitioners at this time.Footnote46 Instead, the ‘Japanese’ techniques were transferred to Norway through European athletes, such as Miller and Kringlebakk. By 1955, Norway had merely twenty judo practitioners who, despite having contact with England and Denmark, described themselves as ‘self-taught’. Thus, when five Norwegians were awarded the brown belt (1st kyū) directly from Japanese Abe Ichiro at an international camp in Denmark in 1955, it was represented as a significant event.Footnote47 The following summer, Abe awarded several Norwegians with the black belt (1st dan) in Denmark.Footnote48 Abe can be described as a ‘martial arts missionary’, a person who had emigrated with the goal of teaching and promoting his nation’s martial arts.Footnote49 In 1951 he was sent to France by the Kōdōkan, on the request of the French Judo Federation. He stayed in Europe until 1969, becoming the Belgian Judo Federation’s Technical Director. From his base in Brussels, Abe continued to teach as Kōdōkan’s official emissary.Footnote50

Paul Bowman, a professor in media and cultural studies, has argued that ‘bound up in the desire to learn a traditional Asian martial art are Asiaphilic desires, orientalist fantasies, and allochronic imaginings of timeless embodied wisdom traditions’.Footnote51 Not surprising, Europeans, such as Miller, who were trained by Japanese ‘masters’, were highly respected by the Norwegian judo community, as they could claim the authority and authenticity of a direct linage to Kanō Jigorō – and the samurais before him. This way, they also served to the extended reach and legitimacy of Japanese judo organizations, such as the Kōdōkan. Robert Marchant, French judo-instructor, who had studied under Kawaishi Mikinosuke and Awazu Shōzō in Paris, proved particularly influential on Norwegian judo in the 1950s. He worked actively to influence Norwegian judo. His first visit to Oslo in 1954 was done with the goal of establishing both a Norwegian judo club and a national judo federation. Marchant planned his mission with Jean Gailhat, the general secretary of the French Judo Federation, and saw himself in a line of French judo-practitioners, who had introduced judo in Luxemburg (Pelletier), Switzerland (Vallee), Spain (Birnbaum), and Belgium and Holland (Jean de Herdt). The French were also promoting judo in Algeria, Indochina and Madagascar. Originally he planned to go to Sweden but chose Norway when Gailhat informed him ‘another Frenchman, Vaccharopoulos, was to go to Stockholm to establish a club’.Footnote52 A linage from Japan was apparently important as before leaving Marchant secured Kawaishi permission to examine and award belts to the Norwegians.Footnote53 During his first visit to Norway, Marchant had long conversations with Lundh’s group and helped plan the establishment of the first ‘Norwegian Judo and Jiu-Jitsu Club’, as well as the Norwegian Judo Federation. From 1954 to 1964, Marchant visited Norway annually and was present in 1958 when the first unofficial Norwegian Judo Championship was hosted on ‘four truckloads of wood shavings’ in Oslo by athletes in uniforms hand-sewn by Lundh.Footnote54 This highlights how judo was spread from high-ranking Japanese instructors, who established clubs, taught in neighbouring countries, and trained local judo teachers who in turn spread their own interpretations of judo to more ‘peripheral’ countries, such as Norway.

The 1965 Delegation: Gaining the ‘Goodwill’ to Secure Judo’s Future in the Olympics

Japanese ‘judo experts’ did not visit Norway before 1965. Yet, the Norwegian media already mythologized them. In a particularly vivid example from Bergen Arbeiderblad, a local labour newspaper, Japanese ‘black belts’ were described as almost superhuman samurai, with total control of the respiratory system and a knowledge of anatomy allowing them to both kill and resuscitate.Footnote55 An actual visit from such exotic individuals would be a significant event in Norway.

In the autumn of 1965, a Japanese delegation consisting of seven martial artists, all students of economy, from Takushoku (lit. ‘the university of colonization’), a private university in Tokyo renowned for its martial artists, arrived in Oslo.Footnote56 Kunimatsu Shigeo, a member of the delegation, explained that their mission was to ‘travel to 42 countries and host exhibitions in karate and judo’ to demonstrate these ‘sports’. Kunimatsu added that: ‘We have been tasked by our homeland to return all the national flags that were hoisted during the Tokyo Summer Olympics’. This was meant to serve ‘as proof that sports can transcend borders more easily than other types of social exchange’.Footnote57 Before reaching Oslo, the 1965 delegation had already crossed 30 countries, driving through India, Pakistan and Europe in a lorry. They even spent over three weeks behind the ‘Iron Curtain’ and made it all the way to Moscow. After Scandinavia, their journey continued to Hamburg, then by boat to the U.S.A. and Canada.Footnote58

On Wednesday, 15 September, the delegation held two exhibitions. During the afternoon, they performed for the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK, the country’s only television channel) as part of their warm-up. A low-ranking Norwegian judo practitioner also participated in the performance. He appeared elated by the skill of his high-ranking Japanese partner. The broadcast was given a prominent position as part of the main daily news the same evening. While this was not the first television broadcast of Japanese martial arts, it marked the first broadcast of high-ranking Japanese ‘black belts’ performing on Norwegian soil. Furthermore, a voice-over explained each of the martial arts being demonstrated, giving each martial art increased exposure:

First, a bit of judo, which includes throws using the entire body. It may seem a bit brutal, but even Norwegian students participate in this and reportedly come away unscathed. Then, we move on to karate, which simply put, involves all types of punches and kicks. These can be so effective that they can be lethal if used to their full extent, which we were assured, is never the case. Lastly, a touch of aikido. This involves throws using joint locks. All of this is considered serious sport and excellent for self-defence.Footnote59

The ‘actual’ demonstration was held in the evening of 15 September, in the University of Oslo’s grand gymnasium, in collaboration with Norwegian Judo and Jiu-Jitsu Club (NJJK) and the Oslo Student Sports Association’s (OSI) judo group and in the presence of attaché Suzuki Hajime from the Japanese embassy in Norway. It was covered briefly by Aftenposten and ended in a formal ceremony steeped in solemnity, where the students returned the Norwegian flag that had flown during the Tokyo Olympics to the Norwegian Confederation of Sports (NIF). The Japanese delegation additionally presented a Japanese flag and results from the Tokyo Olympics, elegantly bound. The flags were presented to the onlookers as equals, then folded by Japanese students in white uniforms, in a symbol of the friendship between Norway and Japan ().Footnote60

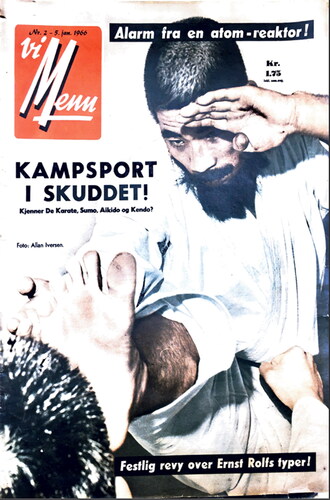

Both the television broadcast and the article in Aftenposten presented the martial arts in positive terms, marking a break from a postwar media discourse which had often portrayed them as violent and dangerous.Footnote61 It is unclear what caused this positive portrayal. The production team at the state owned NRK might have felt it important to portray what appeared to be an official Japanese delegation in positive terms, or possibly the delegations’ ties to the IOC gave it legitimacy. It is also difficult to trace any clear effects of the visit on the media discourse. Just three days later, several newspapers featured an advertisement, captioned: ‘Did you see Judo – Karate – Arkido [sic] on TV last Wednesday?’Footnote62 These were likely funded by Kurt Bai, who later used images of Kunimatsu Shigeo in his advertisements for correspondence courses in martial arts.Footnote63 This more sensationalized portrayal of the Japanese martial arts had a broad appeal, at least according to Bai. He claimed to have sold 25,000 mail-order copies of his course on Japanese self-defence in Norway by 1967, which had become notorious for its initial inclusion of ‘lethal’ techniques Footnote64 However, Kunimatsu also appeared on the cover of the January 5, 1966 issue of the gentlemen’s periodical We Men [Vi Menn], with the headline, ‘Martial arts on the rise! Do you know Karate, Sumo, Aikido, and Kendo?’ (). In two issues of We Men, Norwegians were treated to a detailed six-page exposition on Asian martial arts by Terence Westall, a British karate practitioner living in Norway. Westall acknowledged that Asian martial artists were often seen with ‘scepticism and mistrust’ and considered to possess ‘almost supernatural abilities … that rendered them supermen’.Footnote65 However, like the Japanese delegation, he chose to downplay these mystical elements and presented judo as a safe kampsport [combat sport] and its practitioners as ‘well-trained, athletic sportsmen’.Footnote66 Even so, Westall had represented karate in similar ways even before the delegation visited, showing that the causes for the correlating discourse were complex.Footnote67

While not explicitly stated, the immediate goal of the goodwill tours appears to have been to secure judo’s position in the 1968 Mexico Olympics. As early as September 1951, the IOC recognized the IJF as an international federation for a non-Olympic sport and one of Kanō’s first acts as the president of the IJF was to request that judo become an Olympic event.Footnote68 Despite this, judo was not included in the 1956 or 1960 Olympics. Then, in 1961, after judo was finally accepted as an event for the 1964 Olympics, 83 members of the Japanese diet (approximately 18 per cent of the seats) formed the Judo Federation of Japanese Diet Members, ‘for the purpose of cooperating in the development through the activity of the Diet’.Footnote69 The following year, the Lower House of the Diet unanimously approved plans to build the Nippon Budōkan, a hall for the ‘national sports’ of as kendo, kyudo, sumo, and judo. By combining modern architectural standards with elements of Japanese culture, the Budōkan was meant to symbolize ‘New Japan’. Matsumae Shigeyoshi, a long-time member of the Lower Diet and later Chairman of the Construction Committee of Nippon Budokan, argued that the Budōkan would show the world that ‘justice and peace’ were ‘the true ideals of Japanese martial arts and sweep away the world’s incorrect view connecting them to militarism’.Footnote70 Seen in this context, it is clear that the Japanese state had much to gain by the globalization of judo.

Concurrent with the 1965 tour to Norway, ‘H. Kawasaki’, a member of the National Diet of Japan, led a similar ‘goodwill’ tour for judo to Mexico and surrounding countries. On 15 September 1965, Kawasaki announced that he had secured judo’s place in the upcoming games by getting the approval of the leader of the Mexican Olympic Committee.Footnote71 Despite this announcement, the Japanese knew as of July 1965 that including a new Olympic event would require a winning vote on the IOC meeting in October 1965.Footnote72 IOC president Avery Brundage insisted that the inclusion of judo would require a change to Rule 30, which limited the number of events to 18.Footnote73 While this required a two-thirds majority, the IJF president seemed confident that all of the 66 member countries in IJF would vote in favour for the change.Footnote74 Thus, it appears that one goal of the goodwill tour to Norway in 1965 was to sway the Norwegian Olympic Committee to vote favourably. If the IJF won the vote, judo would figure in future Olympic Games and continue to serve as a symbol of ‘New Japan’.

While Kunimatsu framed the delegation as a cultural diplomatic mission for Japan, the 1965 delegation was not directly funded by the Japanese state, but rather by Takushoku university and ‘various Japanese industries’. Additionally, a ‘major Japanese car group’ had donated the lorry. In total, the tour was planned to cost $3,000, a sparse sum that required the students to spend nights in cheap hostels or under a tarp on the back of the lorry.Footnote75 The 1965 delegation to Oslo was used as part of a low cost, global strategy by the IJF and the Japanese to secure judo’s future in the Olympics while also presenting ‘traditional’ Japanese martial arts to the world which, intentionally or not, served to reinforce the image of ‘New Japan’. However, despite their efforts, the IJF lost the vote in 1965, 23 to 25, and judo was not included in the 1968 Olympics.Footnote76 Instead, Mexico’s National Olympic Committee proposed that the IJF could host the 1968 Judo World Championships in Mexico City at the same time as the Olympic Games. When the IOC rejected this proposal, the IJF toed the line and hosted the World Judo Championships in Mexico City in 1969.Footnote77

The 1968 Delegation: Japanese Champions and a British Coach

In 1968 the newly established Norwegian Judo Federation (NJF) was informed by the Japanese Embassy that a new judo delegation, sponsored by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, would visit Oslo from 25 February to 3 March.Footnote78 This delegation differed from its 1965 predecessor by including two high-profile champions who would stay longer and teach judo. Even so, it was arguably a British coach who had the strongest impact on Norwegian judo from the late 1960s to late 1970s, with his visits shaping an imagined dichotomy between ‘European’ and ‘Japanese’ judo.

The members of the 1968 delegation was Takeuchi Yoshinori, the current Japanese champion, and Maruki Eiji, the reigning world champion.Footnote79 A notice printed in several newspapers described it as a sensation that such ‘Japanese judo experts’ would teach in Oslo: ‘These are no young boys – in their home country they are highly valued, and on the judo grading scale, they are respectively at the fifth and sixth level, meaning quite advanced’. The delegation planned to teach in two local clubs, OSI Judo and Norwegian Judo and Jiu-Jitsu Club, from Monday to Wednesday, then host a public judo exhibition on 29 February.Footnote80 They would also teach judo to physical education students at the Norwegian School of Sports Sciences.Footnote81 While the 1968 delegation was not given much attention by the Norwegian press, Aftenposten captured the moment Takeuchi and Maruki were invited for tea by Torkel Sauer, chairman of the NJJK, in the home of Henrik Lundh.Footnote82 Afterwards, the NJF described the visit from the 1968 delegation as ‘well managed’.Footnote83

The aim the 1968 delegation was to teach judo and increase both the level of the international competitions and the number of participants. During the 1950s IOC president Avery Brundage was hesitant to include judo, which he viewed as ‘too new a sport internationally’ with ‘too few participants’.Footnote84 Subsequently, the IOC rejected the motion for judo to become an Olympic sport in both 1954 and 1955. By increasing worldwide judo activity, the 1968 delegation could help secure judo’s future in the Olympics. The delegation also visited clubs in Denmark, Sweden and Finland, with the goals of encouraging active judo practitioners to compete and inspiring other to start practicing ‘this noble sport’. Before this, Takeuchi and Maruki had a similar tour to Australia, showing that this Scandinavian tour was also part of a larger strategy.Footnote85 In Gothenburg the visit was used to prepare for an international competition between Sweden, Finland and Poland in Uppsala.Footnote86 Concurrently, Denmark was planning to host the third Nordic Judo Championship in Copenhagen in 1968. Aftenposten mentioned that after ‘the pleasure of hosting two Japanese masters who led the training for a week’, the Norwegians had ‘been training intensely in preparation for their [first] participation in the Nordic tournament’.Footnote87 The same year the NJF also expressed goal of joining the European Judo Union ‘as soon as possible’.Footnote88 This suggests that the 1968 delegation succeeded in stimulating judo activity in Scandinavia. While judo was not accepted for the 1968 Olympics, Japan and the IJF’s campaigns in the 1960s proved successful longer term. By 1967 judo was included in the 1972 Olympics and has since remained an Olympic event.Footnote89

Despite these visiting delegations, it was arguably Geoffrey R. Gleeson, Britain’s national coach, who exerted the greatest influence on Norwegian judo in the 1960s. From 1966 to 1970 he was the head coach of NJJK’s annual summer camps, and when the NJF was established during the 1967 camp, he became its first technical advisor.Footnote90 He proved controversial. While traditionally trained during four years at the Kōdōkan (1952–1955), Gleeson was a reformist who believed that judo should not ‘force’ the practitioners to adopt ‘a purely Japanese subculture’, but rather be adopted to European ‘socio-cultural patterns’.Footnote91 He sought to remove ‘the veil of mystique’ that surrounded the sport, and created his own style of judo.Footnote92 From Gleeson’s arrival the Norwegians struggled to choose between Gleeson’s ‘European’ style and the ‘Japanese’ styles of Kawaishi and the Kōdōkan. While Henrik Lundh claimed that ‘much of what was made in Norwegian judo were destroyed by that which Gleeson introduced’, others argued that he was misunderstood and was merely teaching Kōdōkan judo with a new language. These debates continued until the mid-1980s, when the NJF finally settled on the Kōdōkan-system.Footnote93

The 1979 Delegation: Campaigning for the IJF Presidency

More than a decade passed before an official Japanese judo ‘goodwill’ delegation again visited Norway in 1979. Like in 1968, this delegation had a prolonged stay and provided judo instruction. However, it was also part of a campaign to reinstate Japanese leadership in the IJF. Consequently, the visit can be interpreted as part of an effort to preserve the ‘Japaneseness’ of judo. However, care should be taken not to create an oversimplified dichotomy between ‘Japanese’ and ‘sportified’ judo, as Japanese actors also used international sporting arenas to showcase their culture.

The perceived differences between ‘Japanese’ and ‘European’ judo were accentuated when Kōdōkan’s Kobayashi Kiyoshi was recruited to NJJK’s annual summer camps in 1976 and 1977. According to the NJJK, Norway’s judo practitioners could hardly believe that such a high-ranking Japanese instructor, ‘Kōdōkan’s official representative in Europe’, would visit the country.Footnote94 There was a clear contrast between Gleeson, who wore a sweatsuit and described himself as a ‘coach’ not a ‘sensei’, and the more traditional Kobayashi, who started his classes with a deep bow towards a picture of Kanō Jigorō.Footnote95 Unlike the diplomatic tours in 1965 and 1968, Kobayashi’s visits were driven by Norwegian demand. NJJK ‘worked for three years’ to secure Kobayashi’s participation, which was only possible thanks to the NJJK’s ‘especially good connections’.Footnote96 Even so, Kobayashi can be described as a ‘martial arts missionary’ like Abe Ichiro. While visiting Norway, Kobayashi explained his role as ‘representative of official Japanese judo’ in Europe, and his job ‘to take care of smaller judo nations’ by educating local coaches.Footnote97 This is collaborated by his son, who claims Kobayashi was sent to Europe by the Japanese government to promote judo as part of Japanese culture. Kobayashi lived and taught in several countries between 1952 and 1958, including the United States, Egypt, Greece, Belgium, Italy, Germany and France, before settling in Portugal in 1958 where he lived for more than 50 years.Footnote98

In 1979 and 1980 Norway was once again visited by judo delegations who were strictly motivated by Japanese needs, and not drawn by local demand. From February 6–12, 1979, a delegation led by Sato Nobuhiro, a professor in judo at Tokai university, visited Oslo. The other members of the group were Sonoda Isamu, Sato Makoto and Sakaguchi Kazuaki. In Oslo they spent their nights teaching at local clubs, all of Saturday (nine hours) teaching judo instructors and the national team at the Norwegian School for Sport Sciences. On the Friday they also visited the Norwegian Police Academy to share ‘the character-building aspects of judo’ and held a public exhibition at the Oslo Gymnastics Hall.Footnote99 Much was made of the fact that Sonoda had won both the 1969 World Judo Championship and the 1976 Olympics. Before the public performance, Aftenposten ran the following advertisement: ‘Japanese World Champion in Judo has Exhibition Tonight’.Footnote100 By this time, there were more than 3,000 active judo practitioners in Norway, and Sonoda also attended a local judo championship for 300 boys aged 7 to 15. His presence was described as ‘an especially positive addition for the young’.Footnote101

Norwegian sources consistently describe the 1979 visit as an official delegation sent by the Japanese state, as seen in a regional liberal newspaper: ‘The four Japanese are on an official goodwill tour to Southern Europe and Scandinavia. They arrived in Norway on the 6th of February and will proceed to Sweden and Finland on 12 February’.Footnote102 This claim is collaborated by the extensive involvement of the Japanese Embassy in Norway. Not only did Yoshioka Akira, the Japanese ambassador, attend the exhibition on Friday, 9 February, he also invited ‘a range of representatives, including those from the Norwegian Judo Federation, Norwegian Confederation of Sports, Oslo Park and Sports Committee, alongside members of the press, totalling approximately 30 people’ to his residence on 7 February. Here they meet the Japanese delegation, and several Japanese emigrants. The embassy also screened a judo-film for the visitors, which they informed could be lent to local judo clubs.Footnote103 Additionally, the embassy made their interpreter available to the media so they could interview the visiting delegation.Footnote104 This was not the first time the Japanese embassy in Norway helped to stimulate the growth of Japanese martial arts in Norway. At least once, in 1971, it lent out judo-films to be played as advertisement for a new judo club.Footnote105 In 1973 the embassy also showed Kurosawa Akira’s Judo Saga (Sanshirō Sugata), a film which is loosely based on the life of one of Kanō Jigorō’s students, at Cinema Klingenberg in Oslo.Footnote106 Nor was it the last. In March 1979, Embassy counsellor Hirōka would award the trophies at the Norwegian Karate Championship.Footnote107 Then in 1981, 1983, and 1984 the embassy endorsed a local martial arts club’s participation in ‘Japanese Weeks’ – events that promoted Japanese products and showcased Japanese culture, while also serving as advertisement for local martial arts clubs.Footnote108 Japan also occasionally sponsored such martial arts exhibitions through the Japan Foundation, which was congruent with JF’s practice in other European countries.Footnote109

The concurrent trends in Japan’s cultural diplomacy help explain the role of judo in Japan’s cultural diplomacy towards Norway in 1979. According to Evgenia Lachina ‘The internationalization of national martial arts’ had proven to be:

a perfect tool for Japan to reassert its national identity in its own eyes and in the eyes of the world after the humiliation of defeat and occupation. Thus, after Japan’s hard power suffered a defeat, it was transformed into soft power which enabled Japan’s presence all around the world, not physical, but cultural.Footnote110

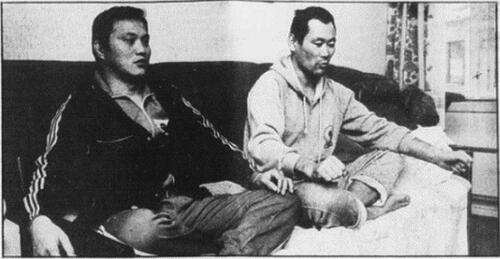

Figure 3. In the article ‘The Japanese Policeman: Balanced but Firm’, the character-building aspects of judo were reinforced by an image of Sato Sonoda and Sato Nobuhiro sitting cross legged in lotus pose, description as ‘exuding a confident and relaxed calm’. Photo: Arild Jakobsen, Fædrelandsvennen, February 10, 1979, 21.

While it is unclear why a regional liberal newspaper from southern Norway would be particularly interested in the delegation, the only substantial interview with its members were conducted by Fædrelandsvennen. In the interview the members of the delegation reproduced the idea of judo as an Olympic sport. However, they also borrowed from the nihonjinron-discourse. One of the delegation’s missions was to lecture on ‘the character developing aspects of judo’. Additionally, its members emphasized the practical applications of judo and jujutsu, particularly as means for law enforcement. Except for Professor Sato, all members were police officers and the article in Fædrelandsvennen emphasized that Sakaguchi was a member of Kidō-tai, an elite riot control unit. This discourse of combat and self-defence was highlighted by images showing Japanese in everyday clothes repelling knife attacks and surprise attacks using jujutsu.Footnote114 During the public exhibition on February 9, 1979, the delegation also chose to demonstrate kime-no-kata, an old set of techniques created explicitly for self-defence and not for competition. This way, the discourse of the 1979 delegation challenged the established view in the NJF that judo was a sport and not self-defence ().

Figure 4. ‘Makoto Sako [sic] attacks with a commando knife – Professor Nobuhiro Sato makes a lightning-fast sidestep to the left – grabs hold of the knife arm and the head of his opponent – positions a leg in front of him, thereby in a pincer grip’. Photo: Arild Jakobsen, Fædrelandsvennen, February 10, 1979, 21.

![Figure 4. ‘Makoto Sako [sic] attacks with a commando knife – Professor Nobuhiro Sato makes a lightning-fast sidestep to the left – grabs hold of the knife arm and the head of his opponent – positions a leg in front of him, thereby in a pincer grip’. Photo: Arild Jakobsen, Fædrelandsvennen, February 10, 1979, 21.](/cms/asset/975ff65f-ce7e-477e-ad3a-610f399788a6/fhsp_a_2380411_f0004_b.jpg)

It can be no coincidence that the 1979 delegation was led by a professor from Tokai University, the same year Matsumae Shigeyoshi, Tokai’s founder, ran for the IJF presidency. Although Matsumae did not personally visit Norway in 1979, he was the head of a similar judo delegation which visited the USA and several European countries in 1978–1979. During these travels he met with local judo instructors, announced his candidature, and explained his plans for the International Budo University, which would be dedicated to the training of international budō instructors.Footnote115 Matsumae and his supporters Nishimura Motoki, Inokuma Isao, and Ōgo Mahito visited approximately 80 countries during his campaign.Footnote116 Matsumae also intended to visit Norway in 1980, accompanied by Inokuma, a former Olympic champion. However, due to the political situation in Japan, the meeting was cancelled. Instead, Matsumae sent his ‘personal assistant’ in the International Judo Federation, Ōgo Mahito, whose explicit goal in Norway was ‘to spread knowledge of judo’ in 1980.Footnote117 As a former diplomat and a long-time member of the Lower Diet, Matsumae also highlighted the ties between the Japanese state and the IJF. By 1979, he held several influential positions in Japan; as head of the Nippon Budokan Foundation (from 1975 until his death in 1991) he oversaw the development of Japanese martial arts. In 1977 he became the leader of the newly established Japanese Budo Association (JBA), which organized the Japanese federations of nine martial arts, including judo, kendo, karate, sumo, and aikidō.Footnote118 The Norwegian vote in the 1979 IJF election is unknown, but Matsumae won decisively, 68 to 25, and the sitting president, Charles Palmer, called his loss a ‘massacre’.Footnote119

Matsumae stressed the national heritage and the character-building aspects of budō. Excerpts from the JBA’s 1987 ‘Budo Charter’, which was published during his presidency, are sometimes used to illustrate how the Japanese worked on preserving budō as a culture heritage amid growing internationalization and sportification:

Today, Budō has been diffused throughout the world and has attracted strong interest internationally. However, infatuation with mere technical training, and undue concern with winning is a severe threat to the essence of Budō. To prevent this perversion of the art, we must continually examine ourselves and endeavour to perfect and preserve this national heritage.Footnote120

Even so, the Japanese state indirectly contributed to the exotification and orientalization of its culture when the Japanese embassy helped establish Oslo Budokan in 1989. This non-profit centre for Japanese culture not only offered courses in judo, karate, aikido, kenjutsu, and kobudo but also facilitated cultural activities like tea ceremonies, calligraphy, and art exhibitions. Oslo Budokan aimed to uphold the traditional mental and cultural aspects of budo, such as etiquette and self-discipline, elements that were perceived to be in decline with the intrusion of Western culture and sports.Footnote124 Its founder held that all Japanese arts shared ‘a common denominator’ as

practitioners undergo a long period of training where basic movements are practiced – until the body, mind, instrument, and activity are fully mastered. Only then can spontaneity flow freely and the practitioner express themselves through their chosen medium, whether it be a brush, sword, or musical instrument.Footnote125 This is a perspective which resonates with Eugen Herrigel’s orientalist proposition from his classic 1948 book Zen in the Art of Archery, where he claims that every Japanese individual perfects at least one art throughout their life.Footnote126

Negotiations on the Meaning of Judo

The development in Norway highlights how the meaning of judo was constructed through transnational negotiations between Western coaches, Japanese ‘martial arts missionaries’, and local Norwegian practitioners. Between 1965 and 1980, Norway was also visited by four judo ‘goodwill’ delegations. Because Norway was only a peripheral target for Japan’s cultural diplomacy these visits were invariably part of broader international campaigns that sought to align local representations of judo with those in Japan. Identifying when a state prioritizes targeting more ‘peripheral’ nations with sports diplomacy provides insights to the processes behind the globalization of sports and the priorities behind sports diplomacy.

In 1965 and 1968 the tours were designed to bolster judo’s status as an international Olympic sport, simultaneously reinforcing the image of the ‘New Japan’ – a peaceful, modern, economically robust nation. In contrast, the 1979 and 1980 tours aimed at securing a Japanese presidency in the International Judo Federation, while emphasizing judo’s roots in traditional Japanese culture, in line with the prevailing nihonjinron discourse. Even so, ‘international sport’ and ‘Japanese traditions’ are not mutually exclusive concepts. Japanese martial arts diplomats, such as Kanō Jigorō and Matsumae Shigeyoshi, can better be described as ‘ethnocentric internationalists’ who strived for judo to become an Olympic sport which embodied Japanese culture. In both the 1960s and the 1970s, the campaigns aimed at aligning the international judo discourse with that in Japan. Martial arts remain a vital part of Japan’s cultural diplomacy – as seen with Karate’s inclusion in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. However, as with judo in the aftermath of Tokyo 1964, this new ‘Japanese’ event was not included in the subsequent 2024 Paris Olympics – suggesting a need for further transnational negotiations on the balance between sportification, internationalization and ‘Japaneseness’.Footnote127

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Glenn Eilif Solmoe

Glenn Eilif Solmoe is a PhD candidate in sports history at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, with a master’s degree in history from the University of Bergen.

Notes

1 Jessamyn R. Abel, The International Minimum: Creativity and Contradiction in Japan’s Global Engagement, 1933–1964 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2015), 160.

2 Andreas Niehaus, ‘Spreading Olympism and the Olympic Movement in Japan: Interpreting “Universal” Values’, in The Olympics in East Asia: Nationalism, Regionalism, and Globalism on the Center Stage of World Sports, ed. William W. Kelly and Susan Brownell (New Haven: Yale CEAS Occasional Publications, 2011), 75–94.

3 Evgenia Lachina, ‘Conquering the World: The “Martial” Power of Japan Goes Global’, The International Journal of the History of Sport 35, nos 15-16 (2018): 1510–30; Haimo Groenen, ‘The Early Development of Women’s Judo in Belgium from the Liberation to the late 1950s: Emancipation, Sport and Self-defence’, The International Journal of the History of Sport 29, no. 13 (2012): 1819–41; Abel, The International Minimum, 160–1; Niehaus, ‘Spreading Olympism’; Allen Gutmann and Lee Thompson, Japanese Sports: A History (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001).

4 See John A. Johnson. ‘Transcending Taekwondo Competition to Sustain Inter-Korean Sports Diplomacy’, The International Journal of the History of Sport 37, no. 12 (2020): 1187–204.; Hsienwei Kuo and Chinfang Kuo, ‘Strategic Role of Taiwanese Acrobatics in the Cultural Diplomacy of the Republic of China since the Cold War’, The International Journal of the History of Sport 38, no. 15 (2021): 1594–611. Abel, The International Minimum, 160–1.

5 However, the further use of the term ‘cultural diffusion’ could suggest that judo is essentially a ‘Japanese’ practice, when its development and globalization is better characterized as a complex and often transnational process.

6 Hans Bonde, Bonde, ‘Return of the Ritual: Martial Arts and the Young’s Revolt against the Youth Rebellion, The International Journal of the History of Sport 26, no. 10 (2009): 1523–39; Bonde, ‘Den gule bølge. Judo mellem eksotisering og sportificering’, in ‘Idrættens regionalisering og internationalisering’, special issue, Idrætshistorisk årbog [Danish yearbook of sports history] (1990): 153–79.

7 Eldrid I. Mageli, Toward Friendship: The Relationship between Norway and Japan, 1905–2005 (Oslo: Unipub, 2006).

8 In 2021, Norway’s martial arts federations had 46,231 members, ranking below only football, skiing, handball, golf, gymnastics, athletics, swimming, and cycling in membership numbers. The Norwegian Confederation of Sports (NIF), ‘Nøkkeltall Rapport 2021’ [‘Key figures report 2021’], October 1, 2022, 66–7, https://www.idrettsforbundet.no/contentassets/e3516813cbf54cd48ac7697df2b32d44/nokkeltallsrapport-2021.pdf (accessed June 17, 2024).

9 The National Library has a worked on digitalizing Norway’s cultural heritage since 2006. Nasjonalbiblioteket, ‘Digitalisering’, n.d., https://www.nb.no/om-nb/digitalisering/(accessed April 17, 2023).

10 Henrik G. Bastiansen, Lojaliteten som brast: Partipressen i Norge fra senit til fall 1945 – 2000 [The loyalty that broke: Party press in Norway from Zenith to Fall 1945 - 2000] (Oslo: Norsk pressehistorisk forening, 2009), 52.

11 Tf-idf considers both the frequency of the term in the document and the frequency of the term in the entire corpus.

12 Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: PublicAffairs, 2004), x, 44–55.

13 Christina Maags, ‘Enhancing China’s National Image Through Culture Festivals’, Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 7, no. 1 (2014): 35–8.

14 Nadejda Gadjeva, Japanese Public Diplomacy in European Countries: The Japan Foundation in Bulgaria and France (New York: Routledge, 2022), 1.

15 Gadjeva, Japanese Public Diplomacy, 22–4.

16 Oleg Benesch, ‘Olympic Samurai: Japanese Martial Arts between Sports and Self-Cultivation’, Sport in History 40, no. 3 (2020): 340.

17 Inoue Shun describes judo as an invented tradition that became the first prototypical modern martial art. ‘The Invention of the Martial Arts’, in Mirror of Modernity: Invented Traditions of Modern Japan, ed. in Stephen Vlastos (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 163–73.

18 Kano translated jujutsu as ‘the art of gaining victory by yielding or pliancy’. Thomas Lindsay and Jigoro Kano, ‘Jiujutsu (柔術). The Old Samurai Art of Fighting Without Weapons’, in Transactions of The Asiatic Society of Japan, vol. XVI (Yokohama: Meiklejohn & Co, 1888), 192.

19 Oleg Benesch, Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 8.

20 Shohei Sato, ‘The Sportification of Judo: Global Convergence and Evolution’, Journal of Global

History 8, no. 2 (2013): 303, 305; Lindsay and Kano, ‘Jiujutsu’, 198; Benesch, ‘Olympic Samurai’, 328–55.

21 Niehaus, ‘Spreading Olympism’, 83.

22 Takashi Uozumi, ‘An Outline of Budo History’, in The History and Spirit of Budō, ed. Takashi Uozumi and Alexander Bennett (Chiba: International Budo University, 2010), 15; Alexander Bennett, Kendo: Culture of the Sword (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 139–54.

23 Niehaus, ‘Spreading Olympism’, 83.

24 Abel, The International Minimum, 141, 144, 204; Gadjeva, Japanese Public Diplomacy, 18.

25 Lachina, ‘Conquering the World’, 1515; Gadjeva, Japanese Public Diplomacy, 19.

26 Gadjeva, Japanese Public Diplomacy, 18.

27 Bennett, Kendo, 163–99;175; Allan Guttmann and Lee Thompson, Japanese Sports: A History (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001), 175–80.

28 Raúl Sánchez García, The Historical Sociology of Japanese Martial Arts (New York: Routledge, 2019), 198.

29 Christian Tagsold, ‘The Tokyo Olympics: Politics and Aftermath’, in The Olympics in East Asia: Nationalism, Regionalism, and Globalism on the Center Stage of World Sports, ed. William W. Kelly and Susan Brownell (New Haven: Yale CEAS Occasional Publications, 2011), 64.

30 Abel, The International Minimum, 161.

31 Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 253.

32 Gadjeva, Japanese Public Diplomacy, 19.

33 Ibid.; Harumi Befu, ‘Nationalism and Nihonjinron’, in Cultural Nationalism in East Asia: Representation and Identity, ed. Harumi Befu (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 120, 125.

34 Harumi Befu, Hegemony of Homogenity (Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press, 2001), 2, 6–8, 68.

35 Benesch, Inventing the Way of the Samurai, 229.

36 Mageli, Toward Friendship, 189, 200, 204; ‘Japansk prins’ [‘Japanese Prince’], Hamar Stiftstidende, February 12, 1952, 3; ‘Nordpolruten er ett år’ [‘The North Pole Route is One Year’], Sarpen, February 22, 1958, 1, 2; ‘Stort opplegg til åpningen av Nordpol-ruten’ [‘Major Event for the Opening of the North Pole Route’], Andøya Avis, February 22, 1957, 1.

37 Mageli, Toward Friendship, 79; Gadjeva, Japanese Public Diplomacy, 47; ‘Den tiende japanske flytende messe i Oslo’ [‘The tenth Japanese floating fair in Oslo’], Norges Handels og Sjøfartstidende, September 27, 1972, 5; ‘Secretary Girl/Friday’, Aftenposten Morgen, March 5, 1966, 33; Spotlight on Japan, Morgenbladet, August 12, 1966, 1, 5–13; Thirty pages on ‘Japan i Norge’ [‘Japan in Norway’], Rana Blad, February 20, 1974.

38 Gadjeva, Japanese Public Diplomacy, 48; ‘Japansk uke i Oslo [‘Japanese week in Oslo’], Norges Handels og Sjøfartstidende, March 3, 1959, 4; ‘RIE på by’n’ [‘RIE Out in the City’], Aftenposten Morgen, March 12, 1960, 4; ‘Velkommen til japansk uke’ [Welcome to Japanese week’], Adresseavisen, February 17, 1969, 17; ‘Japansk uke med sake og mini-kabaret’ [‘Japanese week with sake and mini cabaret’], Drammens Tidende og Buskeruds Blad, October 18, 1969, 6.

39 ‘Japan i Oslo’ [‘Japan in Oslo], Aftenposten Morgen, March 31, 1984, 6.

40 Richard Bowen, ‘Origins of the British Judo Association, the European Judo Union, and the International Judo Federation’, in Jujutsu & Judo in the West, ed. Micheal DeMarco (Kindle: Via Media, 2018), 24.

41 Uozumi, ‘An Outline of Budo History’, 16; Sánchez García, The Historical Sociology of Japanese Martial Arts, 198.

42 Kjell Salling, ‘Den europeiske judounion’ [‘The European Judo Union’], Norsk Judo, no. 6 (1986): 17; Bowen, Jujutsu & Judo in the West, 29.

43 ‘Salling, ‘Den europeiske judounion’, 17.

44 Bowen, ‘Origins of the British Judo Association’, 30. The present of this Japanese diplomat can further be viewed in context of the City of Tokyo’s concurrent bid to host the Olympics, which had cross-party support in the Lower House of the Diet as early as May 1949. Abel, The International Minimum, 144.

45 He learned from Ingbrigt Solum, an officer, and Sam Melberg, a private instructor with ties to the resistance. ‘Henrik Lund’, Norsk Judo, no. 3 (1974): 8–9.

46 Torkel Sauers graduation card from the French Judo and Jiu-jitsu Federation. Geir Åstorp, ‘Torkel Sauer’, Judoinfo, February 24, 2015, https://judoinfo.no/torkel-sauer/ (accessed October 30, 2023).

47 ‘Norske judo-utøvere hevdet seg i internasjonal leir’ [‘Norwegian Judo Practitioners Excelled at an International Camp’], Aftenposten Aften, August 24, 1955, 6.

48 ‘Torkel Sauer 60 år’ [‘Torkel Sauer 60 years’], Norsk Judo, no. 6 (1985): 19.

49 Although he does not use the term ‘martial arts missionary’, Bennett has similarly commented on the ‘almost evangelistic tendencies of Japanese with regard to kendo’s propagation overseas’. Bennett, Kendo, 221.

50 John Bowen, ‘In Memoriam: Ichiro Abe Kodokan 10th dan (1922 – 2022)’, The Kano Society Bulletin, no. (2022): 1–6.

51 Paul Bowman, Mythologies of Martial Arts (London: Rowan & Littlefield, 2017), 69.

52 Robert Marchant, ‘En hilsen fra Robert Marchant 5. Dan’ [‘A greeting from Robert Marchant 5. Dan’], Norsk Judo, no. 2 (1979): 22–3.

53 Ibid.

54 ‘Judo, er en kunstart hvor alt simpelt og brutalt er fjernet’ [‘Judo, is an art where everything vile and brutal has been removed’], Dagbladet, July 16, 1958, 8; ‘Et 25-års minne’ [‘A memory of 25-years’], Norsk Judo, no. 2 (1978): 18; ‘Judo – som japanerne kaller en “myk kunst”’ [‘Judo – Which the Japanese call a “Soft Art”’], Aftenposten Morgen, February 16, 1963, 13; ‘Henrik Lundh’, Norsk Judo, no. 3 (1974): 8–9.

55 ‘Han lærer Bergenserne judo’ [‘He teaches the people of Bergen Judo’], Bergens Arbeiderblad, November 23, 1963, 12.

56 The group consisted of Washizawa Arata, Kunimatsu Shigeo, Murakami Hiroshi, Inada Susumo, Okamura Junzō, Ishii Masahiro, with 26-year-old Sasaki Hirokichi as their leader. ‘Sju japaner i lastebil på resa runt jorden’ [‘Seven Japanese in a lorry traveling around the world.’], Göteborgs-posten, September 17, 1965.

57 Interview with Kunimatsu. ‘Karate er ikke å knuse murstein’ [‘Karate is not breaking bricks’], Arbeiderbladet, September 16, 1965, 22.

58 Norway was number ‘30 out of 44’ or ‘20 out of 42’ according to different sources. ‘Norsk olympiadeflagg fra Tokyo overrakt Norges Idrettsforbund’ [‘Norwegian Olympic flag from Tokyo presented to the Norwegian Confederation of Sports’], Aftenposten Morgen, September 16, 1965, 30; ‘Sju japaner jorden runt i lastebil’ [‘Seven Japanese crossing the world in a lorry’], Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfarts-Tidning, September 17, 1965, 1; Arbeiderbladet, September 16, 1965, 22; Göteborgs-Posten, September 17, 1965, 22.

59 The Daily Review, television broadcast, aired September 15, 1965, on The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK).

60 [‘Norwegian Olympic flag from Tokyo (…)’], Aftenposten Morgen, September 16, 1965, 30.

61 While judo and jujutsu had gradually been represented in more positive terms, likely due to the NJF’s efforts and judo’s inclusion in the Olympics, karate remained controversial. Compare ‘Skolert selforsvar eller uhemmet råskap?’ [‘Schooled self-defence or unrestrained brutality?’], Arbeiderbladet, April 21, 1955, 10; ‘Jiu-jitsu og karate’, Aktuell, July 4, 1964, 40.

62 ‘Så De Judo – Karate – Arkido på TV sist onsdag?’ [Did you see Judo – Karate – Arkido [sic] on TV last Wednesday?], Bergens Tidende, September 18, 1965, 23. The same advertisement appeared in Arbeiderbladet, September 18, 1965; Stavanger Aftenblad, September 18, 1965, 11.

63 ‘Kan De forsvare Dem ved et overfall?’ [Can you defend yourself against an assault?’], Aktuell, April 1, 1967, 34.

64 ‘Livsfarlige grep pr. postordre’ [‘Lethal holds by mail order], Dagbladet, August 23, 1967, 1, 11.

65 ‘Orientalsk kampsport i skuddet’ [‘Oriental martial arts on the rise’], Vi Menn, January 5, 1966, 10.

66 ‘Hender uten våpen’ [‘Hands Without Weapons’], Vi Menn, January 12, 1966, 31.

67 ‘Karate’, Vi Menn, June 16, 1965, 6.

68 Andreas Niehaus, ‘‘If You Want to Cry, Cry on the Green Mats of Kôdôkan’: Expressions of Japanese Cultural and National Identity in the Movement to Include Judo into the Olympic Programme’, The International Journal of the History of Sport 23, no. 7 (2006): 1176.

69 Letter, Matsutaro Shoriki (president of Judo Federation of Japanese Diet Members) to Otto Mayer (chancellor of the IOC), June 6, 1961, The International Judo Federation (D-Rm02-JUDO), Correspondence 1951–1969 (003), The IOC Historical Archives, Lausanne, Switzerland (hereafter IOCA).

70 Abel, The International Minimum, 160–1.

71 ‘Jiu-Jitsu på OL-programmet i Mexico 1968’ [Jiu-Jitsu on the Olympic Program in Mexico 1968’], Aftenposten Morgen, September 16, 1965, 15.

72 Letter, Kano Risei to the IOC, July 8, 1965, The International Judo Federation (D-Rmo2-Judo), Correspondence 1951–1969 (003), IOCA.

73 Minutes from the Meeting of IOCs Executive Committee, October 5, 1965, IOC Executive Board, 1960–1969, IOCA.

74 Letter, Kano Risei to the IOC, July 8, 1965, The International Judo Federation (D-Rmo2-Judo), Correspondence 1951–1969 (003), IOCA.

75 ‘Sju japaner jorden runt i lastebil’ [‘Seven Japanese crossing the world in a lorry’], Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfarts-Tidning, September 17, 1965, 1; ‘Sju japaner i lastebil på resa runt jorden’ [‘Seven Japanese in a lorry traveling around the world.’], Göteborgs-Posten, September 17, 1965, 22.

76 ‘Request from the I.F. of Judo’ Comité International Olympique Bulletin 92 (1965): 77–8.

77 Letter, J.W. Westerhoff to Pedro Ramirez Vazques, July 21, 1967, The International Judo Federation (D-Rm02-JUDO), Correspondence 1951–1969 (003), Correspondance 1966–1967 (SD6), IOCA.

78 Torkel Sauer, The NJF’s Annual Report, November 2, 1968, in ‘Forbundsting’ [‘General Assembly’], Judoinfo, https://judoinfo.no/judoforbundet/forbundsting/ (accessed November 1, 2023); ‘Jeg gik altid i en stor bue uden om slagsbrødre’ [‘I always gave Brawlers a wide berth’], Berlinske Tidende, March 2, 1968, 22.

79 ‘To japanske judo-eksperter til Oslo’ [‘Two Japanese judo experts to Oslo’], Nationen, February 12, 1968, 3; Geir Åstorp, ‘Terje Gunnerud – 6. Dan’, Judoinfo, August 31, 2016, https://judoinfo.no/terje-gunnerud-6-dan/ (accessed November 1, 2023).

80 ‘Japanske judo-eksperter skal instruere i Oslo’ [‘Japanese judo experts to instruct in Oslo’], Aftenposten Aften, February 9, 1968, 6. See also ‘Judoeksperter på besøk’ [‘Judo experts visits’], Sunnmøre Arbeideravis, February 10, 1968, 1, 5; ‘Japansk kulturdelegasjon til Oslo for å demonstrere judo’ [‘Japanese cultural delegation to Oslo to demonstrate judo’], Varden, February 10, 1968, 28; ‘To japanske judoeksperter til Oslo’ [‘Two Japanese judo experts to Oslo’], Nationen, February, 10 1968, 3.

81 Åstorp, ‘Terje Gunnerud – 6. Dan, Judoinfo.

82 ‘Japanske judoeksperter til Oslo’ [‘Japanese judo experts to Oslo’], Aftenposten Aften, February 26, 1968, 7.

83 Minutes from the NJF’s Board Meeting, March 10, 1968, in ‘Stiftelsesdokumenter’ [‘Founding documents’], Judoinfo, October 2014, https://judoinfo.no/judoforbundet/stiftelsesdokumenter/ (accessed November 1, 2023).

84 Brundage quoted in Niehaus, ‘If You Want to Cry, Cry on the Green Mats of Kôdôkan’, 1188.

85 [‘Two Japanese judo experts to Oslo’], Nationen, February 12, 1968, 3.

86 ‘Arbetet golvade världsmästeren’ [‘Arbetet floored the word champion’], Arbetet, February 19, 1968, 11.

87 ‘Norge deltar for første gang i Nordisk i judo’ [‘Norway participates for the first time in Nordic in judo’], Aftenposten, April 18, 1968, 11.

88 Minutes from the NJF’s Board Meeting, August 27, 1968, in ‘Stiftelsesdokumenter’ [‘Founding documents’], Judoinfo, October 2014, https://judoinfo.no/judoforbundet/stiftelsesdokumenter/ (accessed November 1, 2023).

89 Letter, J. W. Westerhoff to A. Geesink, January 11, 1967, The International Judo Federation (D-Rm02-JUDO), Correspondence 1951–1969 (003), Correspondance 1966–1967 (SD6), IOCA.

90 Minutes from the NJF’s Constitutive Meeting, June 28, 1968, in ‘Stiftelsesdokumenter’ [‘Founding documents’], Judoinfo, October 2014, https://judoinfo.no/judoforbundet/stiftelsesdokumenter/ (accessed November 1, 2023); ‘Norges eldste judo-klubb’ [Norway’s oldest judo club’], Norsk Judo, no. 5 (1985): 4–5.

91 Gleeson quoted in ‘British Coach Analyzes U.S Judo’, Black Belt Magazine (February 1973): 24–5.

92 Gleeson quoted in ‘Judo er artisteri med proffer i hovedrollen’ [‘Judo is artistry with professionals in the leading roles.’], Arbeiderbladet, July 4, 1970, 15.

93 ‘Henrik Lundh, Norsk Judo, no. 3 (1974): 21; Carl August Thoresen, ‘Judo historie i Norge – Del 2’ [‘Judo history in Norway – Part 2’], Judoinfo, November 21, 2014, https://judoinfo.no/judo-historie-i-norge-del-2/ (accessed November 1, 2023).

94 ‘1976 Judosommerleir’ [‘1976 judo summer camp’], Hajime 2 (1976): 8.

95 Gleeson in ‘British Coach Analyzes U.S. Judo’, Black Belt Magazine (February 1973): 24–5; ‘Møte med Kiyoshi Kobayashi’ [‘Meeting Kiyoshi Kobayashi’], Norsk Judo, no. 1 (1979): 35.

96 [‘1976 judo summer camp’], Hajime 2 (1976): 8.

97 ‘Japaner instruerer i luftige svev’ [‘Japanese instructs in lofty throws’], Fremtiden, August 10, 1977, 5.

98 Renato Santos Kobayashi, ‘Mestre Kiyoshi Kobayashi’ [‘Master Kiyoshi Kobayashi’], Instituto Português de Artes Tradicionais Japonesas, September 9, 2015, https://www.facebook.com/ipatj/photos/mestre-kiyoshi-kobayashikiyoshi-kobayashi-%C3%A9-considerado-o-pai-do-judo-em-portuga/1073113529367311/?locale=pt_PT (accessed November 1, 2023).

99 ‘Besøk fra Japan’ [‘Visit from Japan’], Norsk Judo, no. 1 (1979): 25; ‘Den japanske politimann: avbalansert men håndfast’ [‘The Japanese policeman: Balanced but firm’], Fædrelandsvennen, February 10, 1979, 21.

100 ‘Japansk verdensmester i judo’ [‘Japanese world champion in judo’], Aftenposten, February 9, 1979, 18.

101 ‘Mange friske judokamper’ [‘Many vigorous judo matches’], Akers Avis Groruddalen, February 23, 1979, 6; ‘Japansk topptrener på judoleir i Svelvik’ [Top Japanese coach leads judo camp in Svelvik’], Arbeiderbladet, August 12, 1977, 34.

102 ‘Den japanske politimann: avbalansert men håndfast’ [‘The Japanese policeman: Balanced but firm’], Fædrelandsvennen, February 10, 1979, 21.

103 ‘Mottakelse i den japanske ambassade’ [‘Reception at the Japanese embassy’] Norsk Judo, no. 1 (1979): 7.

104 ‘Den japanske politimann: avbalansert men håndfast’ [‘The Japanese policeman: Balanced but firm’], Fædrelandsvennen, February 10, 1979, 21.

105 ‘Sørlandets første judoklubb stiftes onsdag’ [‘Southern Norway’s first judo club to be established on Wednesday’]. Fædrelandsvennen, January 16, 1971, 14.

106 ‘Oslo i dag’ [‘Oslo today’], Aftenposten Morgen, February 17, 1973, 8.

107 ‘Karate-NM’ [Norwegian karate championship], Asker og Bærums budstikke, April 2, 1979, 8.

108 The club was Oslo Budo Kwai. ‘Karate’, Aftenposten Morgen, October 5, 1981, 10; ‘Japansk uke’ [‘Japanese week’], Dagbladet, June 1, 1983, 33; ‘Japansk uke’ [‘Japanese week’], Aftenposten Morgen, March 24, 1984, 6.

109 Gadjeva, Japanese Public Diplomacy, 47; ‘Karate’, Aftenposten, October 5, 1981,10; ‘Japan Today in Norway’, Dagbladet, October 11, 1990, 49.

110 Lachina, ‘Conquering the World’, 1526.

111 Gadjeva, Japanese Public Diplomacy, 19.

112 Befu, ‘Nationalism and Nihonjinron’, 120.

113 Niehaus, ‘Spreading Olympism’, 88.

114 ‘Den japanske politimann: avbalansert men håndfast’ [‘The Japanese policeman: Balanced but firm’], Fædrelandsvennen, February 10, 1979, 21.

115 Uozumi, ‘An Outline of Budo History’, 20; ‘Personal History of Shigeyoshi Matsumae’, The International Judo Federation (D-Rm02-JUDO), Biographies, questionnaire, report, work plan and information flash 1963-1985 (009), Biographies des Présidents de l’IJF 1975-1980 (SD5), IOCA.

116 ‘Store forandringer i IJF’ [‘Huge changes in the IJF’], Norsk Judo, no. 1 (1980): 4.

117 ‘OL-vinner til Norge’ [‘Olympic champion to Norway’], Aftenposten Morgen, May 19, 1980. 16; ‘Japansk judo-kapasitet [‘Japanese judo expert’], Demokraten, May 29, 1980, 15; ‘Mahito Ohgo på Norgesbesøk’ [Mahito Ohgo visits Norway’], Norsk Judo, no. 2 (1980): 15; ‘Norsk Judo- og Jiu-Jitsuklubb fikk besøk av japansk pedagog’ [‘Norwegian judo and Jiu-Jitsu Club hosts Japanese educator’], Akers Avis Groruddalen, May 23, 1980, 7.

118 ‘Personal History of Shigeyoshi Matsumae’; Uozumi, ‘An Outline of Budo History’, 18.

119 ‘Store forandringer i IJF’ [‘Huge changes in the IJF’], Norsk Judo, no. 1 (1980): 4.

120 ‘The Budo Charter’, 1987, quoted in Miguel Villamón, David Brown, Julián Espartero, and Carlos Gutiérrez, ‘Reflexive Modernization and the Disembedding of Jūdō from 1946 to the 2000 Sydney Olympics’, International Review for the Sociology of Sport 39, no. 2 (2004): 153; See also Bennett, Kendo, 4.

121 Niehaus, ‘Spreading Olympism’, 77.

122 ‘What emerged from the fusion of Olympic internationalism with particular national cultures and its application toward nationalistic impulses and ambitions might be labelled ethnocentric internationalism’. Abel, The International Minimum, 123.

123 Ibid., 125, 128.

124 ‘Budosport er mer enn slag og spark’ [‘Budo sport is more than kicks and punches’], Aftenposten, November 3, 1989, 19.

125 Torild Nesheim Bamre, ‘Japansk kultursenter’ [‘Japanese Cultural Centre’], Arbeiderbladet, January 11, 1990, 16.

126 Yamada Shoji, ‘The Myth of Zen in the Art of Archery’, in Martial Arts in the Modern World, ed. Thomas A. Green and Joseph R. Svinth (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003), 89.

127 Chang-Ran Kim, ‘Olympics-One and Done? Karate Ponders Uncertain Olympic Future after Tokyo Debut’, Reuters, August 8, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/sports/review-olympics-did-it-pass-test-what-are-karates-prospects-games-2021-08-08/ (accessed June 27, 2024).