Abstract

The marathon in the Olympic Games in 1896 immediately inspired the sporting community both in Europe and in the United States. Some organizers sought to surpass the record set in Athens and awarded their marathon winners generously. In Norway, the main sports federation wanted to control the competition, and how it would be perceived. According to the Secretary of the Federation, the military Captain F.G. Seeberg, no participant should finish a long race in bad style, or even worse, dead. His organization managed, to some extent, to impose this partly aesthetic ideal on the many marathons during the following years. This restricted the striving for records, largely due to the shared ideology of amateurism among sportswriters and athletes. The story of marathons’ development in Norway and the rest of Scandinavia from 1896 to 1906 illuminates early cooperation and standardization in international sports, as well as national divergencies. More crucially, it details how the broader ideology of sports amateurism shaped a new long-distance running event due to its intensified attention to style.

The invention of the modern marathon is a well-known story. Michel Bréal, a French philologist inspired by several ancient literary sources of the runner-soldier Pheidippides, presented the idea of an ‘Olympic’ race from Marathon to Athens to his friend, the sports enthusiast Pierre de Coubertin. The impact of the first marathon, in relation to the success of the first Olympic Games in 1896 and the great spectacle aroused by a ‘home-run’ by the local hero Spyridon Louis, has been thoroughly researched.Footnote1 The reception and imitation in a wider, international context has been analysed by Pamela Cooper, who studied how marathon-running evolved in New York and Boston and noted that it emerged as a sport pursued by blue-collar athletes for many years.Footnote2 Marathon’s global reach was further detailed by David Martin and Roger Gynn, who, among many others, have written the long and fascinating history of numerous Olympic marathons.Footnote3

The development of the initial marathon races in Norway and Scandinavia, a narrative less commonly explored in the annals of sport history, reveals both national divergences and the transnational organization and cooperation around sports events. More significantly, it underscores the concept of amateurism as more than a set of rules pertaining to money and social classes but as a broader sports ideology shared by athletes and sports leaders alike.

The early Norwegian marathons have been treated by Finn Olstad, and Matti Goksøyr, albeit briefly and without extensive analysis. Both scholars focus on the role of the Norwegian Sports Federation (Centralforeningen for udbrædelse af idræt, hereafter the NSF) in deciding how the races should be conducted and evaluated. Olstad relates this organization and its prominent secretary, Franz Gustav Seeberg (1852–1940), primarily to the tradition and ideology of Swedish gymnastics.Footnote4 Goksøyr explains how the NSF in the long term ‘lost’ to the modernisation, or rather the ongoing ‘sportification-process’ as he terms it; a concept that implies and describes how traditional and occasional activities from around 1900 and then on were organized, rationalized, and centred around competitions and comparable results. To rephrase Allen Guttmann: records replaced rituals.Footnote5

Amateurism provides an overarching context for how marathons developed in Norway, and to some degree in Scandinavia as a whole. Amateurism is, or rather was, a complex sporting ideology that, among other aspects, explained the attention many sport writers and leaders paid to the aspect of style. Scholars have often occupied themselves by the social dimension of sport amateurism and the many related rules about income and money.Footnote6 Eric Halladay early suggested a broader framework, including pedagogical, ethical and aesthetic themes. Richard Holt elaborated more fully upon this.Footnote7 Both in this wider ideological sense focusing on health, morality, and style, and in a narrow sense focusing on rules and definitions, amateurism sheds light on how the marathon was welcomed in, and adapted to, established Norwegian traditions. Equally as important as the records were the moral and aesthetic qualities with which the runners completed the race.

The NSF yearbooks are important primary sources regarding these marathons. So are various editions of the influential sporting magazine Norsk idrætsblad (‘Norwegian Sports Magazine’) and most important daily newspapers published in the Norwegian capital Kristiania (which was the name of Oslo before 1925).Footnote8 Taken together, these publications and periodicals form an important part of what can be termed as the sports public sphere in Norway, a concept that also comprises important (often yearly) sporting events, the sites where these competitions and festivals took place, as well as the results of, reports from, and reflections upon these events.Footnote9 In the sports public sphere, various sports and their inherent values were discussed and negotiated. Marathon running was no exception. The sport writers and leaders introduced it with great interest; the clubs and the athletes themselves developed it; and it must be said, some years later the event became disputed, and by some disregarded in the sports public sphere. Accordingly, the motivation and ideas behind (and against) this sporting praxis should be regarded as important as who organized and financed it and then how popular it grew (at least for a while) among both athletes and spectators. Sports amateurism was an underlying philosophy throughout the first ten years of Norwegian marathon running. This moral and aesthetic value system in the sports public sphere helps explain the marathon’s enthusiastic introduction, its development, and to some extent this neo-Greek tradition’s fall from grace.

The Significance of Olympic Amateurism

The first modern Olympic Games – here meaning the competitions held (mostly) in accordance with the ideas of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) – were organized in Athens, Greece in 1896. At that time, Norway was in a personal union with the larger country of Sweden, where King Oscar II. presided over the joint foreign policy. Norwegian sports leaders were not present at the first IOC conference in Paris in 1894, and no Norwegian athletes participated in the games in Greece, nor did any journalist from Norway report in person from Athens. The sporting magazines and the newspapers, however, wrote extensively about this event both before and during the Olympic Games (April 5–11). The editors and journalists concentrated on what foreign papers told of the marathon race, the enthusiasm this event had created all over Greece, all the gifts that many people had bestowed upon the winner (Spiridon Louis), and what true amateur values the winner really represented.Footnote10 The possible tension – between this poor farmer and his noble performance, and all the material gifts that the larger society tempted him with – may be said to resonate with Coubertin’s own report from the games. According to the secretary of the IOC, Louis’ sense of honour, a sense that was strong in every Greek farmer, ‘saved the non-professional spirit from a very great danger’.Footnote11 The various notes and articles especially in the main sports magazine Norsk idrætsblad concluded in the same way, thereby confirming, or at least insisting upon, the champion’s deeply rooted amateurism.Footnote12 Considered more broadly, Norwegian sports writers associated ancient Greek sports with typical nineteenth century-amateur values of honour and simplicity, very much in line with how Coubertin and his committee perceived the ancient Olympic Games.Footnote13 It is also important to note that the educated classes who read the magazine Norsk idrætsblad, were familiar with the ancient battle at Marathon (490 BC). Hence, the word ‘marathon’ was perceived as related to values of freedom and independence (from autocracy and slavery) well before the term entered the sports public sphere.Footnote14 A paragraph in the sports magazine in 1899 illustrates perfectly this vivid and lasting idea: ‘The glorious memories of Marathon and Salamis, where European culture triumphed over Asian barbarism, and discipline over masses, presuppose the Olympic and other national games, where the Greek darlings competed in strength and grace under the eyes of the nations.’Footnote15

In June 1896, Norsk idrætsblad wrote about a marathon held in Paris, where the clear intention behind the event had been to beat Louis’ record, and the winner (a British professional runner) was awarded 2000 Francs by the magazine Petit Journal that also initiated the race.Footnote16 This arrangement can be said to confirm what Tony Collins has termed ‘the iron law’ (or symbiotic relationship) between capitalism in print media and sports.Footnote17 In Norway, on the other hand, the main sports periodical did not attempt to inspire record-setting competitions, nor did it argue for a very valuable prize to the winner. Already in May 1896, the magazine mentioned plans of a long running race in Denmark, and the editor called for a similar run on home turf, as the Norwegian landscape near the capital, he said, resembled the many hills and curves of the original, and more demanding, Greek race.Footnote18 The landscape itself, as well as the rough conditions, became a motive in the many local reports later on, as this made the Norwegian marathons stand apart, at least from the races in Paris and Copenhagen.

Then, in September 1896, this periodical, as well as some of the daily Norwegian newspapers, printed advertisements for a Norwegian marathon of 40 km for adults 18 and over, whether being members of a sporting club or not. A relatively minor sporting club in the capital, Kristiania Idrætsforening, (Kristiania Sports-Association, hereafter KI) founded in 1893, was behind this initiative.Footnote19 KI consisted of about 150 members in 1896; it was smaller than the main club Tjalve, which also concentrated on athletics – or ‘foot racing’ [‘fodsport’] as it was termed then, and the club recruited among blue-collar workers as much as white-collar workers.Footnote20 Why KI would arrange a marathon was not noted in the advertisements. It is, however, very likely that the inspiration came from the description of the long-distance race in Athens in Norwegian newspapers and sport magazines. Race walking, admittedly, was a well-established event in Norway, thanks to the major athletic club in Kristiania (Tjalve); on the other hand, the distances here were typically much shorter (10 km/20 km).Footnote21 The well-respected association Foreningen til Skiidrættens Fremme (The Ski-Association, hereafter Skiforeningen) had experimented with long distance skiing (cross country, 50 km), back in 1888, but this race represented a special event until it was re-introduced in the ski-festival in Holmenkollen on the outskirts of Kristiania in 1902.Footnote22

The local club, KI, had applied to the NSF for financial support for organizing the competition. The NSF was originally established in 1861 but then rebranded in 1895: it was both an association with paid membership and a federation of more than 3,100 local clubs and various sports associations, and it certainly tried to exert control over how different sports developed.Footnote23 The affiliated clubs were obliged to write yearly reports of their activities and of the events that had been financially supported by the federation. These reports were then published in the NSF yearbook, which was publicly available. In particular, the secretary Franz Gustav Seeberg, who held that position from 1892 until 1920, wrote and lectured extensively about, or rather against, the tendencies towards records, specialization, and professionalism in many sports. He was a military officer by education, and a gymnastics teacher by profession.Footnote24

A week before the race, in the leading newspaper Morgenbladet, Seeberg recommended the forthcoming marathon for every sportsman. He legitimized it as a test of vital physical endurance, although he expressed scepticism to the rather long distance of over 40 km.Footnote25 He declared that he detested race walking; noting that this was an English invention that was both useless and ugly. Instead, he wanted people (men) to walk long distances and run whenever possible. By this he meant that they should not run uphill. Either way, walking or running, rational preparation was essential, from the secretary’s point of view. Rational training implied for him primarily indoor (and in the summer outdoor) gymnastics, as he repeatedly argued that this should be the fundamental and all-round and harmonious basis for every sport.Footnote26

In the newspaper, Seeberg explained that the NSF had granted the organizers financial support on certain terms: including that it should consider the runner’s ‘Kondition’ in the results. He had advised the local club to have a doctor present at the finish line – a medical expert who would then examine their physical and mental state, or condition. He warned against the quest for new records, in marathon as well as in other sports, because it could lead to semi-professionalism, which attracted only a few, and excluded the masses. ‘Records!’, he wrote with disapproval: ‘This record-nuisance has gotten so out of hand that it threatens to extinguish all healthy sports.’Footnote27 Sports’ most important value, Seeberg argued, consisted of that almost everyone was invited to participate and given an equal chance to test his abilities, and to succeed.Footnote28 In the long run, one would need to distinguish between several divisions and levels to make the competition compelling for a lot of athletes, but for now, as this was the very first marathon in Norway, he thought that everyone should be invited to participate in the same competition. Civilians and military students and officers were encouraged to enlist themselves, although they all had to be amateurs, he wrote.Footnote29 This last and important requirement had not been mentioned in the advertisements. The club KI probably assumed it because there were few, if any, professional runners in Norway at that time.Footnote30

Neither Seeberg, the NSF nor the athletic club KI expressed explicitly that women could not – or rather should not – participate. In the 1890s, several (male) writers in Norsk idrætsblad did encourage women to try out skiing, and even take part in minor races.Footnote31 The NSF, on the other hand, had a doctor warning in its yearbook of 1896: ‘Let our women go skiing, it’s good for them, but make them understand that their physical development and structure, their whole physique, is not the same as a man’s, and that skiing, for a woman, must be adjusted accordingly’.Footnote32 Athletics, even more so than skiing, was a domain only for men, and only for respectable masculinity – at least until the 1930s.

The First Marathon in Norway

In terms of the number of participants, which obviously was Seeberg’s main criterion for success in every sport, the first Norwegian marathon race must be characterized as a triumph. 28 men signed up for the competition, more than in Athens (25) and in Copenhagen that same autumn. There were, however, fewer participants than in New YorkFootnote33 and many fewer than the almost 200 men who participated in the race in Paris in July.Footnote34 Probably even more runners would have lined up in the Norwegian race if the Norwegian Athletics’ Federation (Norsk Idrætsforbund) had not stated, as it originally did, that associated clubs and members should not take part in competitions held by associations that were not members of the federation.Footnote35

As a stand-alone event, this marathon also laid the pattern for the following years’ competitions as well. Captain and Secretary F.G. Seeberg showed up in person, if not necessarily in his uniform, at the starting line of the race, approximately 50 km. south of the capital of Norway. He urged the runners to adhere to three important pieces of advice: (1) do not start out too fast; (2) do not accelerate uphill; and (3) do not, under any circumstance, push yourself too hard towards the finishing line, thereby losing your ‘Kondition’.Footnote36 As he also had explained in the newspaper, a doctor would be receiving the runners after the race in order to examine the runners’ health and general condition. This dimension would then be part of the final ranking. Seeberg probably did not explain in detail how the runners’ condition would affect the actual, final result.

Also, the competitors were to start with an interval of three minutes between them. The existing sources do not disclose why this method was chosen instead of a mass start, as was used in Athens. It does, however, make sense when one thinks of the assigned doctor’s task. Having doctors qualifying and quantifying the performance had already been used in public sports in Kristiania. When the association Skiforeningen organized the combined event of ski jumping and cross-country skiing in 1883, two doctors examined the skiers after the approximately 4 km cross-country race. In their subsequent report they recommended that information about the athletes’ age, height and weight should be included in the race programme. They had seen such sport statistics being published in the United States, and they thought such (quantitative) information would be highly interesting for the spectators.Footnote37

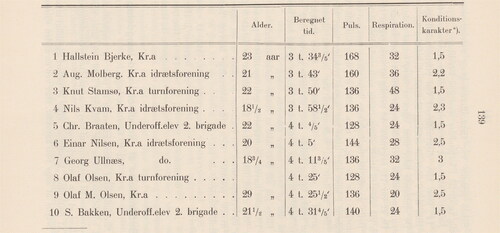

The first marathon took place in October 1896 in cloudy and cold weather. When it began to rain, the hilly course grew rather wet and slippery and became really challenging. Hallstein Bjerke of KI ran the fastest; his first Norwegian marathon record settled at 3.34.36. This result was well behind Spiridon Louis’ approximately three hours, or the winner’s time in Copenhagen two weeks later. On the other hand, considering the demanding conditions, this result must be characterized as quite impressive. Bjerke and probably the other racers, one must conclude, cannot have followed all the instructions he heard from Seeberg before the race commenced.Footnote38 As noted, the overall health condition of the runners should be considered as important as the hours, minutes and seconds used – according to the NSF and Seeberg. Consequently, in relation to the results of each of the ten prize winners, readers of the daily newspapers and the sporting magazine could also figure out the athletes’ pulse, breath, and condition after the race. Per Giertsen, the attending physician, had categorized the runners in terms of a score where 1 was the very best and 5 was too low to pass. In the final ranking, published in the daily newspaper Morgenbladet and in the periodical Norsk idrætsblad, it is, however, obvious that the finishing time weighted more than the health condition score, as the hours and minutes which the runners had spent on the distance gave their ranking. For example, August Molberg (KI) finished second in time, but received a lower score than Knut Stamsø (KI), who finished third. Even so, a military student who finished tenth, won a special prize from the NSF for a fine finishing time and being in good health condition.Footnote39 In a display of Solomonic wisdom, the NSF's own report, published six months later, accounted both for the time spent on the race, when one considers the ranking of the runners, and their physical condition, all summed up in a specific grade (to the right in the table in ).

Figure 1. Behind each of the prize winners was noted their age (‘alder.’ – (column to the left)), finishing time (‘beregnet tid’), heart rate (‘puls’), breathing rate (‘respiration’) and condition score (‘konditions-karakter’).Footnote40

In the same yearbook of NSF, Dr Giertsen explained in more detail how he had conducted his examinations. He was aware that pulse and respiratory rates were not, in themselves, determining factors of the overall condition. The physician shared that he had checked whether each runner’s heart rate was regular, whether the skin was too pale, and how the athlete responded to his questions.Footnote41 Most interesting in this report from the marathon race was his clarification of why he had disqualified a military student. Jørgen Ultvedt (his full name was made public) had finished the race in an almost ruined condition, Giertsen declared. Ultvedt’s condition was obviously far worse than that of the rest; his condition score was set to 5. Besides this, and according to his own explanation, Ultvedt had accepted a glass of cognac proffered him just a few kilometres ahead of the finish line. Giertsen concluded that rational or sensible physical activity should be encouraged, while alcohol use while participating in sports should be banned.Footnote42

Ultvedt’s position as a military student might have led Dr Giertsen to evaluate him more strictly than most of the civilian runners. It is more than possible that Giertsen in this case lent an ear to officer Seeberg, who himself must have observed that the military student had finished the race in bad style. (Seeberg himself had bicycled through the course.) In any case, this disqualification represented a striking contrast to the old myth of ancient Greece. The soldier-runner Pheidippides was a literary hero because he had pushed himself so hard that he died. The officer-to-be Ultvedt in Kristiania was a real villain, at least for the sport authorities, because he had exhausted himself. He had also shown a weakness in his character when accepting the cognac. For Seeberg, both as a sports leader and a military commander, to risk one’s very life was not ideal. His concept of condition comprised more than just stamina or (physical) endurance. Seeberg’s ideal condition was a blend of medical and aesthetic, and even moral, dimensions. A good performance, he argued on many occasions, had to be measured by condition, and attitude, as well as time.Footnote43

Norwegian and Scandinavian Marathons

Similar stand-alone marathons were held by KI in Kristiania during the following years, based on the same underlying rationale, and amateur terms, as in 1896. Participants who registered for the race, whatever their profession in civil life, had to be amateurs. Military students did not take part, though, which one might ascribe to Ultvedt’s rather tragic fate. The age limit was raised to 20 in 1898, based on a recommendation from the medical experts.Footnote44 Around 1899, two separate classes, seniors and juniors, were introduced. A junior was here defined as a racer who had not previously won any prize in marathon races, while the more experienced senior had. In both classes, the runners started with a specific interval between them. A doctor awaited them at the finish line, and a ‘medical’ report about the runners’ condition was written. The prizes were solely medals.Footnote45

Afterwards, hours, minutes, and seconds spent, as well as the pulse and health condition of the prize winners, were published at least in the periodical Norsk idrætsbladFootnote46 and in the NSF Yearbook in 1898, 1899, and 1900. This last-mentioned publication included a more detailed list made by the doctor that included information about the participants’ profession, probably stressing their amateur status. The time the runners had spent determined the order of the results presented in the sports magazine and the newspapers and even in the report that KI produced to the NSF, while Dr Magelsen’s thorough account in the yearbook (both in 1898 and 1899) presented the participants in the order in which they crossed the finish line. (With a start interval of three minutes between each runner, it was not immediately clear that the first to cross the finish line was the winner).Footnote47

Similar long-distance races took place in Bergen and also in the smaller Norwegian cities Tønsberg, Kristiansand, and Stavanger.Footnote48 Some of these competitions were arranged in connection with national competitions in athletics, and the first Norwegian national marathon champion might be named as early as 1897, although he (Hallstein Bjerke) was not officially declared as such then.Footnote49 The marathons, at least in the Norwegian capital, were often hampered by bad weather, but when it came to numbers of spectators and reports in the newspapers, the races grew quite popular and became well respected.Footnote50 The participants represented a broad range of professions and social classes; for example, in 1899 farmers, mechanics, clerks and even a typographer ran the marathon in Kristiania.Footnote51 Although the number of runners fell sharply in Kristiania in 1898 (from 28 to 11), probably due to a lack of advertising, the introduction of the two separate classes attracted 25 participants in 1900.Footnote52

The marathon champion Hallstein Bjerke competed against the best Danish long distance runner Martinus Olsen in 1898, first in Copenhagen at an international event, and in the autumn in the Norwegian national championships in athletics in Bergen: The Dane won on both occasions.Footnote53 In 1898, three local Scandinavian clubs (KI in Kristiania, Arbejdernes Idræts-Forening in Copenhagen, and Östermalm Idrottsforening in Stockholm) decided to cooperate and arrange an official Scandinavian amateur championship alternating among the three capitals. However, the rules of the Danish Sports Association excluded those from Denmark who had competed against non-members (represented by, for example, Arbejdernes Idræts-Forening).Footnote54 In 1899, the first official Scandinavian marathon was arranged in Kristiania, here as a stand-alone event, and with the NSFs ‘rules’ announced before the race commenced. The winner was a Swede; the Danish athletes did not participate, for unknown reasons. Even for this race, a doctor authorized a report, including scores for the participant’s health condition. The organizing club (KI), however, emphasized the new Norwegian records set in this race in their report to the NSF Yearbook.Footnote55 International races were also held in the capital of Norway in 1902, now with two distinct classes, one for former prize winners, and one for participants who had not won any previous marathons. In its yearbook, the NSF praised how rationally the Swedish winners in the long running distances had prepared themselves, and even more importantly, their gracious style.Footnote56 The doctor at this race probably examined the participants before the race, as this procedure also had been followed in a minor marathon race in Kristiania in 1901.Footnote57 Health condition scores were no longer part of the given results.

The Athletes’ Own Stories

Marathons evolved from a clear focus in the sport’s public sphere on style, medical ‘condition’, and similar physical aspects, to a sharper attention to time spent – and that of attaining records. The attention also changed from local and national races to Scandinavian and international races (some on Norwegian ground). This was in line with at least some of the runner’s wishes. In 1899, the Danish champion Martinus Olsen wrote in the magazine Norsk idrætsblad, about how marathons had developed from that first run in Athens. He informed about the various countries and cities that had arranged similar long-distance competitions, who the winners were, and their finishing times. Olsen’s text discloses in this respect the process of standardization in the marathon as a specific sports-event, long before the Olympic Marathon in London (1908) made 42.195 km a new standard distance. It also highlights the quest for records that characterizes the modern sporting world. Even so, Olsen did not seem to doubt the other premises of amateur sport. According to Danish newspapers, Olsen, a house painter by occupation, was enthusiastically recruiting Norwegian participants to an international marathon in Denmark: He did this merely for the fun and honour of his endeavours, and certainly not due to any commercial interest.Footnote58 He even offered the organizers of a marathon in Bergen a very precious drinking horn trophy as a special prize. This gesture was strikingly similar to what Breal had done earlier; he had given the organizers in Athens a silver cup for the marathon winner (with his own name engraved on it).Footnote59

Hallstein Bjerke, the first Norwegian marathon champion and a mason by profession, did not discuss marathon extensively in the public sports sphere. He revealed his own quest for records as he ran the course south of the Norwegian capital in a private race in the spring of 1897, here with bicyclists pacing him.Footnote60 In 1898 he wrote a report to the NSF from the international marathon in Copenhagen, where he and five other Norwegians had received financial support for their travel expenses. In this event all the 23 runners started as a group, accompanied by many cyclists, because each of the participants had his own pacer (who had agreed upon a certain speed and a finishing time goal). Bjerke did not hide his criticism of the ideals – or put more precisely, the lack of ideals – concerning style and condition here, based on his experience during this arrangement. (He himself finished third in this marathon). The quest for records, which the author termed ‘record-extravagance’ [‘rekordflokseri’], ruled.Footnote61 There were no other rules than this lavishness, according to his report. Two of the Swedish runners were much too young, 15 and 17 years old. The runner finishing fourth in the race, a young Swedish man with the appropriate surname Fast, was also a competitive cyclist.Footnote62 Bjerke found Mr Fast’s body posture rather saddening; he noted that his chest was concave and that he also was hunchbacked. Although Bjerke did not use the word amateur or amateurism explicitly, his ideals were clearly influenced by this ideology, especially in his characterization of the Danish marathon’s indifference to stylish aspects. It is plausible that he had a certain reader in mind when he shared his harsh criticism; Secretary Seeberg would surely agree on this, in particular what he regarded as the lack of style in cycling races.Footnote63

Cycling as a competitive sport had practised pacing for several years. Gustav Thorp, a keen amateur cyclist who chased records both in track cycling as well as 50 km and 100 km road racing,Footnote64 argued in a letter published in the leading Norwegian sports magazine in 1899 that pacing should be introduced in marathons as well. He even disputed the established tradition in Norway of interval starts, as he thought that all starting at the same time would make the race much more interesting to the spectators and fairer for the participants. His most important argument was nevertheless that this could improve the finishing times.Footnote65 Hagbarth Wergeland, the editor of the magazine, deeply disagreed with Thorp in this matter, and published a remark in response to the letter. In his comments he suggested banning pacing from all amateur sports. Good competitions were meant to measure excellence among equals, not to distinguish between those who had a clever pacer and those who did not. Wergeland admitted that pacing may be necessary in cycling and horse harness racing, but athletics still had not been spoiled by such means: ‘[We] have not heard about a marathon runner who has received free equipment from a shoemaker, just to advertise for his products.’Footnote66 He probably hinted to the kind of semi-professionalism that the famous cyclist Wilhelm Henie was accused of, in several publications.Footnote67 In a letter in the next edition of the magazine, the secretary of the organizing club KI, Hjalmar Thorstensen, rejected both pacing and the use of a mass start. The reason, he explained, was that his club, in accordance with the NSF rules and Secretary Seeberg’s basic views, wanted to avoid runners risking their lives while participating in marathons. He argued that to start the runners with three minutes between them ensured an ‘honest and fair run’.Footnote68 Hence, the moral dimension of sports amateurism was clearly present in this defence of the Norwegian approach to marathons from both the editor of the sports magazine, and the secretary of the organizing athletic club in Kristiania. Focusing on the virtues of courage and serious – but no too serious – effort, they thought fair and morally grounded competitions should and could support the formation of a good character in the participants.Footnote69

Half Marathons

For some sports leaders and medical doctors, marathons could obviously be detrimental to good health and aesthetically appealing sports. In 1901, the Norwegian Athletics’ Federation decided to reduce the race length in the national marathon championships to approximately half the traditional marathon distance (20 km).Footnote70 The decision was made by a margin of eleven to seven, indicating a highly divided stance among the members. Why the federation chose to not continue the established tradition of full national marathons, the sources do not divulge. It happened even as the president of the federation at that time, Asbjørn Bjerke, was the brother of Hallstein Bjerke, the pioneer of Norwegian marathon running.Footnote71 The NSF, and it seems Secretary Seeberg on behalf of this federation, decided not to financially support any full-stretch marathons after this.Footnote72 He argued, very much in line with reports from various medical doctors, that few of the marathon runners were prepared enough or used rational methods enough to get ready. In one sense, they were too committed to the values of amateurism, although this logical flaw did not seem to occur to Seeberg. He had encouraged the many readers of Morgenbladet to take part in the marathon in 1896. Now he found that many who did try this long-distance running, had not taken their preparations seriously enough.Footnote73

Either way, the Bergen-based club Norrøna, which is likely to have depended on the NSF for monetary support for prizes and other costs, reduced the length of their marathon from 1903. Still, the event was termed ‘Marathon race’ in the newspapers, and to all the spectators along the track, it was highly popular at least until 1905.Footnote74 Some readers of Norsk idrætsblad disputed the idea that a 20 km race was healthier and expressed the view that they wanted the full distance back.Footnote75

In 1906, a relatively large team from Norway (which had become a fully sovereign national state the year before), took part in the jubilee-Olympics that Greece organized in Athens ten years after the first Olympics had been arranged by the IOC. No local Greek athlete won the marathon this time, and no Norwegian participated in this race: The registered Norwegian athlete (Fritz Skullerud) was, for all practical purposes, disqualified even before the race commenced.Footnote76 The Norwegian main sports magazine contented itself, and its readers, with a single, and only one, eyewitness account of the marathon race.Footnote77 The enthusiasm for the long race had significantly diminished.

The political conflict between Norway and Sweden in 1905 probably explains why Scandinavian marathons were not held in the following years. Sweden and the neighbouring country Finland (that won independence from Russia in 1917) developed strong long-distance runners. For Norwegians, the marathon distance became a somewhat uncomfortable event for many decades until the female pioneers Grete Waitz and Ingrid Kristiansen set their marathon World Records in the 1970s and 1980s.Footnote78 In national Norwegian championships, the original marathon distance was re-introduced as late as 1950.

This very long hiatus may seem to be a paradox. In the Norwegian sports public sphere long distance skiing was very popular and widely supported; the champions of the 50 km cross-country skiing championships were hailed as ‘kings’ of their sport even from the beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote79 Many influential Norwegian writers argued that what set long-distance cross-country skiing apart from other (and foreign) sports was that the ski track was determined by the landscape itself; hence, the athletes had to master natural curves as well as uphill and downhill tracks in the Norwegian woods and mountains. The outdoor environment with pristine snow contributed to a clean and morally sound and educating sport, as they saw it.Footnote80 Most marathons took also place outside the stadium and in the outskirt of Kristiania, Bergen, and Stavanger. This fact could theoretically have increased this long-distance event’s esteem in the Norwegian public sphere. Aspects of such thinking were evident in the many articles on marathons in the Norwegian sports magazine in 1896. However, over time, the Olympics became associated with specialization and with stadiums in large cities.Footnote81 This negative connection may have influenced the negative view of marathons in some circles in the sports public sphere. Besides, the marathon was a recently established – and foreign – tradition, which likely contributed to the more sceptical view in Norway. Long skiing competitions (‘skirenn’) was also an invented tradition, with its own involvement with and from medical science. Nevertheless, it was portrayed as something highly national, if not the national tradition, of Norway.Footnote82 Furthermore, the very nature of cross-country skiing, with changing snow and temperature conditions, made it much less relevant in terms of time and records. In addition, marathon’s relationship to negative health implications, was highly debated and disputed in international media, especially after the Olympic race in London in 1908 and Stockholm 1912.Footnote83

A Conflict within Amateurism

In one interpretation of the rise and fall of marathons in Norway, Secretary Seeberg of the NSF is the tragic main character who fought for higher ideals in a minor running event – and lost to the mightier forces within or beneath the sportification process. In another version he was the stubborn ideologist of stylish and healthy sports who managed to undermine and even eradicate marathons on Norwegian soil, at least for many years. In fact, the NSF’s reluctance and scepticism pertaining to marathons, as well as the decision in 1902 to stop supporting such events financially, may be perceived as the opposite of sportification. Some scholars have suggested the term ‘de-sportification’ to conceptualize the tendencies that slowed the development of intense, results-driven and comparable competitions;Footnote84 others have used ‘militarization’ for some of these tendencies.Footnote85 Secretary Seeberg argued, in the context and question of marathon-running as early as 1897, that the value of a dead soldier was almost zero, and that the essential goal was to have an orderly ready for new assignments.Footnote86 In this, he definitely expressed himself as a military commander. Regarding the broader and longer process of sportification, F.G. Seeberg should be perceived as a qualified hindrance. He accepted the element of competition and the drive for winning, but he wanted all sports to have a greater purpose, including personal health and the military strength of the country. Even so, the amateurism of the era should not be neglected. Seeberg’s sports ideology should not only be seen as a result of his military and gymnastics instructor background. Furthermore, the marathons in Norway and Scandinavia should not be identified only with his ideas – but with how these events were conceived of and treated in the broader sports public sphere.

Analytically, amateurism may be interpreted in a narrow sense, only relating to the many rules concerning monetary aspects (and professionalism behind it) – such as travel stipends, income, and value of prizes. The organizing club Kristiania Idrætsforening in 1896, and from 1898 the three cooperating Scandinavian clubs, accepted amateurs – in this narrow connotation – as the only legitimate participants in marathons, although shared and specific amateur rules for all of Scandinavia had not been defined at that time. The runners themselves seemed satisfied with the modesty of the prizes; they ran mostly for (and around one third of them then won) medals. The spectators probably did not put any bet on the runners either; at least the sports magazines and press did not report and – something that was quite usual in the context of professional speed skating in Norway at that time, and of course, in horse racing.

Amateurism may also be understood in a broader sense, as a sports ideology – including dimensions related to health and education and not the least, to ethics, and to aesthetics.Footnote87 A common thread through several epochs of the influential periodical Norsk idrætsblad, was the conception that sports, and especially what was termed outdoor Norwegian true ‘idræt’ – above all skiing – could prepare people for bravery and endurance, virtues they needed in life.Footnote88

Several writers in the 1890s conceptualized idræt as the opposite of (English) sport. Secretary Seeberg, accordingly, expressed his distaste not only for records and fatiguing long distances, but for the lack of beauty in many modern sports. As mentioned, he despised the foreign technique of speed walking because it looked horrid to him, and he disliked the bent-forward position in speed skating and in cycling as well – partly because he thought it was unhealthy when the chest was bent inward, partly because such a body posture was dreadful to him, in aesthetic terms. The influences from classical Greek culture profoundly affected the worldview of the educated classes, particularly shaping the perspectives of Seeberg’s generation.Footnote89 In the 1896 yearbook he explicitly discussed the characteristic of the classical Greek body culture, its tendency towards harmony and perfection, and where this fine tradition then went wrong. He found that the ancient Olympic Games in Greece developed into desperate striving for the first prize and, as a result, to further and further specialization. This was the original sin: ‘The consequence of this specialized education was again that the great majority became mere spectators, and the battle for honours was fought only between a few who pursued it as a craft or livelihood, athletes and professionals. And with this, everything was in absolute decay’.Footnote90 Seeberg held that participation was the core value in sports. To take part and compete, as a moral virtue both in sports and in the broader life, was a fundamental value in the Norwegian and Scandinavian sports amateurism.Footnote91 Although Seeberg’s scepticism grew even stronger in the years after 1897, he did not distance himself from competitive sport altogether. Nevertheless, he did really worry about the growing enthusiasm for length over style also in the Norwegian winter tradition of ski jumping.Footnote92 The medical expertise that the NSF invited as part of the evaluation team in sports may also have inspired Seeberg to focus even more on the aspect of health.Footnote93

The idea of a strict health condition grade was met with resistance from Skiforeningen, and very likely from some of the participants in marathons as well. One can also detect some differences and a degree of polarization between articles in the main Norwegian sports magazine and the NSF yearbook. The NSF focused more on aesthetics and health, while the editors and writers of Norsk idrætsblad prioritized the moral values of effort and fair competitions. This divergence reflects a conflict inherent in amateurism itself. Whether the defining, fundamental attribute should be the style and the grace of the athletes, or their commitment to, and honesty in, their sports activity was not always clear. By and large, in the Norwegian sports public sphere, the all-round quality that the amateur athletes were supposed to embody, was perceived as much more important than a simple quest for records, or even worse, for money.Footnote94

The Rise and Fall of Norwegian Marathons

Marathon-running was quickly introduced in Norway, following the first Olympic Marathon in 1896. The Norwegian sports public sphere embraced the event: both editors and sports leaders believed it to contain, and develop, a true amateur spirit. Even so, the mighty secretary of the National Sports Federation, Captain F.G. Seeberg, wanted firm control over how the runners pushed themselves, and introduced a grade or score of condition that should be integrated in the results. The concept of condition, ‘Kondition’ as it was called in Norwegian, was a blend of medicine and aesthetics as well as moral values. The medical expertise that his organization incorporated into sports probably influenced him, and other sport leaders, to not support marathon events from 1903 on. Some of the athletes wanted to introduce (foreign) pacing and mass start in marathon to attain new records, but most of them, in line with the local organizing clubs, supported the attention to style, and to modesty, in the overarching ideology of sports amateurism. After the first enthusiasm of the Greek and Olympic marathon, Norwegian sports leaders developed a fear that Olympic sports would lead to more and more specialization. Marathons in Norway developed almost as a Greek tragedy; amateurism inspired its rise in 1896, and contributed to its fall, a decade later.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Matti Goksøyr, Daniel Svensson and Mona Engvig for useful comments on this text.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gudmund Skjeldal

Gudmund Skjeldal is Associate Professor at the Department of Sport and Social Sciences, Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, Oslo. In his PhD thesis (2022), he concentrated upon sports amateurism in a Norwegian context.

Notes

1 See for example John, J. MacAloon, This Great Symbol: Pierre De Coubertin and the Origins of the Modern Olympic Games (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981); and Anthony Th. Bijkerk and David C. Young, ‘That Memorable First Marathon’, Journal of Olympic History (1999): 5–24.

2 Pamela Cooper ‘Community, Ethnicity, Status: The Origins of the Marathon in the United States’, The International Journal of the History of Sport 9, no. 1 (1992): 50–62.

3 David E. Martin and Roger W.H. Gynn, The Olympic Marathon: The History and Drama of Sport’s Most Challenging Event (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2000).

4 Matti Goksøyr, Historien om norsk idrett [‘The history of Norwegian sports’] (Oslo: Akilles, 2022.), 63–5. Finn Olstad, Norsk idretts historie. Bind 1. Forsvar, sport, klassekamp 1861-1939 [Norwegians sports history] (Oslo: Aschehoug/Norges Idrettsforbund, 1987), 140–2.

5 See Allen Guttman, From Ritual to Record: The Nature of Modern Sports (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008). Guttmann’s concept, first elaborated in the edition of 1978, is modernization. The concept sportification has been suggested by Matti Goksøyr, among others, to enhance the ongoing process of rationalization in competitive modern sports. See Matti Goksøyr, ‘Sivilisering, modernisering, sportifisering – fruktbare begreper i idrettshistorisk forskning?’ [‘Civilization, modernization, sportification – Fruitful concepts in sport history research?’] (Report, Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, 1988).

6 See Matthew P. Llewellyn and John Gleaves, The Rise and Fall of Olympic Amateurism (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2016); and Wray Vamplew, Pay Up and Play the Game: Professional Sport in Britain, 1875-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

7 Eric Halladay, ‘Of Pride and Prejudice: The Amateur Question in English Nineteenth-Century Rowing’, The International Journal of the History of Sport 4, no. 1 (1987): 39–55. Richard Holt, ‘The Amateur Body and the Middle-Class Man: Work, Health and Style in Victorian Britain’, Sport in History 26, no. 3 (2006): 352–69. For a thorough presentation and discussion of their positions, see Gudmund Skjeldal, ‘“Kjærlighed”, “Sportsgribbe”, og “Cirkusartister”. Amatørførestillingar i norsk idrettsoffentlegheit 1866-1907’ [‘Amateur conceptions in the Norwegian sports public sphere 1866-1907’), 55–61.

8 The editor in the magazine, for most of the time period 1896–1906, was Hagbarth Wergeland – member of a well-known family in Kristiania, and a true amateur ideologist in most of his writings. In circulation numbers the magazine was relatively small, but its influence on the other daily newspapers, and on the sports public sphere as such, was huge. See Skjeldal, ‘“Kjærlighed”, “Sportsgribbe”, og “Cirkusartister”, 113–51, 345–440.

9 The ongoing process of digitizing historical printed materials in Norway has enormously facilitated the search through diverse and dispersed publications.

10 See ‘De olympiske lege’ [‘Olympic Games’], Norsk idrætsblad, April 9, 1896 (no. 14), 115. In this note is was said that a woman would take part, among the 25 Greek [men] that planned to run the Maraton (42 km). A later and longer piece, ‘De olympiske lege’, Norsk idrætsblad, April 24, 1896, (no 16), 128–9, told both of Bréals original idea, the myth of the runner that died, and the spectacle that the triumph of Spiridon Louis (‘Loys’) arose in Athens, though his full name was not mentioned, just that he was a young farmer. See also: ‘Marathonløbet’, Norsk idrætsblad, May 14, 1896 (no. 19), 153.

11 Bijkerk and Young, ‘That Memorable First Marathon’, 19. This article also contains a lot of interesting eye-witness reports from different journals and newspapers, including the Swedish Tidning för Idrott, about the first marathon in Athens in 1896.

12 ‘Athletik’, Norsk idrætsblad, April 30, 1896 (no. 17), 138. More than 14 different newspapers wrote about the marathon race in Athens, some of them also expressing the view that all Louis’ gifts were well deserved.

13 ‘Idræt og gymnastik’ [‘Sports and gymnastics’], Norsk idrætsblad, January 6, 1896 (no. 1), 5.

14 See for example Siegwart Petersen, Verdenshistorier. Læse- og lærebog for borger- og almueskolen [World Histories for Schools] (Kristiania: Capppelen, 1877), 24–5.

15 My transl. ‘Om turningens betydning’ [‘On the importance of gymnastics’], Norsk idrætsblad, November 16, 1899 (no. 46), 559 [‘De hærlige minder fra Maraton og Salamis, hvor den europæiske kultur seirede over det asiatiske barbari, disciplinen over masserne, har til forudsætning de Olympiske og andre nationale lege, hvor de græske yndlinge under nationes øine kappedes i kraft og gratie.’]

16 ‘Det franske Marathonløb’ [‘The French Marathonrace’], Norsk idrætsblad, July 30, 1896 (no. 30), 243.

17 Tony Collins, Sport in Capitalist Society: A Short History (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2013), 6.

18 Norsk idrætsblad, May 14, 1896 (no. 19), 155.

19 ‘Norsk Marathonløb’, Norsk idrætsblad, September 24, 1896, (no. 38), 305. The runners had to be over 18 years old. Advertisement for example in ‘Marathon-løb’, Chr. Nyheds- og Aver.bl (Morgenposten), October 1, 1896 (as well as the dates September 26, and 29. The fee was set low, only 1 (NOK) for each runner.

20 Helge Pharo, Tjalve Hundre År [Tjalve Hundred Years] (Oslo: Schibsted, 1990),16–7.

21 See for example, ‘Lettvindt metode’ [‘A too easy method’], Norsk idrætsblad, November 15, 1892 (no. 45), 317.

22 Thor Gotaas, Femmil: skisportens manndomsprøve [The fifty kilometer: Skiings’ test of manhood] (Oslo: Gyldendal, 2013).

23 Centralforeningen for udbredelse af idræt (hererafter Centralforeningen), Aarsberetning for 1896, samt vinteren 1896/1897 [Yearbook for 1896, as well as the winter 1896/1897] (Kristiania: Brøggers bogtrykkeri, 1897), 28.

24 It was called ‘Den Gymnastiske Centralskole’ in Norwegian. F.G. Seeberg was the principal there from 1894 to 1987. He became later Lieutenant colonel in the army (1908). See Olstad, Norsk idretts historie, 112.

25 ‘42. km Kapgang, Løp tilladt’ [‘42 km. Walking, Running Permitted’], Morgenbladet, September 26, 1896 (no. 560), 2. It was signed by the initials ‘F.G’; most probably ‘Franz Gustav’ [Seeberg]. Most newspapers consisted of only four (unpaginated) pages at this time; page number are therefore not noted.

26 See Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1896, 1–10. This foreword was written by Seeberg himself, and it was titled ‘Idræt og Gymnastik’ (‘Sport and Gymnastics’).

27 My transl. [‘Dette Record-uvæsen har taget sadan Overhaand nu, at det holder paa at dræbe al sund Idræt.’] ‘42. km Kapgang, Løp tilladt’ [‘42 km. Walking, Running Permitted’], Morgenbladet, September 26, 1896 (no. 560), 2.

28 Seeberg was reluctant to women’s participation in most competitions, and he did not like the idea of children’s sport either. In gymnastics, on the other hand, he supported lessons and practices for women.

29 To have membership in any club or association was not mandatory, the advertisements said. Any (specific) definition of an amateur did not rule all Norwegian sports at that time, though the question of prizemoney (or not) was well-known, and an important issue, in the Norwegian sports public sphere at that time. See Skjeldal, ‘“Kjærlighed”, “Sportsgribbe”, og “Cirkusartister”…’, 372–5.

30 Performing artists had been practicing public running events in Norwegian cities previously in the nineteenth century. Ice skating (primarily speed skating) was the most important sport that introduced this question of professionalism in a Norwegian, and even a Scandinavian, context. Especially the controversies regarding the champion Axel Paulsen in 1888 contributed in this respect. See Skjeldal, ‘“Kjærlighed”, “Sportsgribbe”, og “Cirkusartister”…’, 275–9. In 1896, in the very autumn as the marathon was held, an amateur controversy occurred regarding the race cyclist Wilhelm Henie (father of the later ice skater Sonja Henie). Henie, world champion in 1895, was disqualified from the championships in Copenhagen, as he had accepted, according to the officials that excluded him, to stay several nights for free in a hotel in Amsterdam, while he took part in a competition there. See Skjeldal, ‘“Kjærlighed”, “Sportsgribbe”, og “Cirkusartister”, 402–3. According to the scholar Helge Pharo, who wrote the history of the athletic club Tjalve, some sort of disagreements regarding amateur rules was behind its foundation in 1890. Gustav Thorpe, a businessman and keen cyclist, was among the founders. Helge Pharo, Tjalve Hundre År [Tjalve hundred years] (Oslo: Schibsted, 1990), 25.

31 Finn Olstad, Norsk idretts historie. Bind 1. Forsvar, sport, klassekamp 1861-1939 [Norwegians sports history] (Oslo: Aschehoug/Norges Idrettsforbund, 1987), 70–1, 90–1.

32 My transl. Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1896 samt vinteren 1896-1897, 70–3. [«Lad vore kvinder gaa paa ski, det har de godt af, men lat dem forstaa, at deres legemlige utvikling og bygning, deres heles fysik ikke er den samme som mandens, og at skiløbning for kvindens vedkommende maa avpasses herefter.»]

33 See ‘Great Athletic Records’, The New York Times, September 20, 1896 (no. 14067), 6.

34 The first Danish marathon-edition, on October 28, organized by Arbejdernes Idræts-Klub, had 18 participators; they were most probably all amateurs, as they competed for medals, and for some cups and a chest needle that Dansk Idræts-Forbund (Danish Sport Federation), had handed the organizers in support. See Norsk idrætsblad, November 12, 1896 (no. 45), 361.

35 KI had not been invited when the federation Norsk idrætsforbund was founded, as it was accused of sowing conflict, and not cooperation, in Kristiania. See ‘Norsk Idrætsforbunds representantsamling’ [‘Norwegian Sports-Association’s Representantional Assembly’], Norsk idrætsblad, October 8, 1896 (no. 40), 321.

36 See ‘Det norske Marathonlöb’ [‘The Norwegian Marathon Race’], Norsk idrætsblad, October 15, 1896 (no. 41), 328.

37 The doctors, Mr Heiberg and Mr Irgens, had even used scores or grades (1,2,3) in their judgement of the skiers’ condition and attitude. See ‘Præmieskirendet ved Huseby’ [The ski-race at Huseby’], Norsk idrætsblad, March 9, 1883 (no. 5), 40.

38 The magazine explicitly abstained from a comparison, it wrote, not only out of the conditions, but of the terms that Centralforeningen had presented, especially concerning ‘Kondition’.

39 ‘Fodløb paa 42 kilometer’ [‘Footrace of 42 kilometers’], Morgenbladet, October 7, 1896 (no. 588, frontpage). Norsk Marathonløb’, Norsk idrætsblad, September 24 (no. 38), 305. See also ‘Det norske Marathonlöb’ [‘The Norwegian marathon race’], Norsk idrætsblad, October 15, 1896 (no. 41), 328.

40 Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1896 samt vinteren 1896-1897, 141.

41 Ibid., 140–1.

42 Goksøyr has highlighted how alcohol was a natural part of Norwegian sporting life, at least in skiing at that time, Matti Goksøyr, ‘Det lille klunk i sækken’, in Norge anno 1900: Kulturhistoriske glimt fra et århundreskifte [Norway around 1900: Glimpses of a cultural history], ed. Bjarne Rogan (Oslo: Pax, 1999), 69–85.

43 Seeberg often paired condition with attitude (‘Holdning’), which also could be translated as good manners, or even ‘character’. See Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1895 samt vinteren 1895-1896, 3–7.

44 This age-limit might have been introduced by the NSF in 1898, meant to guide all demanding events in every sport. See Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1897 samt vinteren 1897-1898, 19–25.

45 Hallstein Bjerke, who won the race in Kristiania twice, was in 1898 awarded the special silver-medal of Centralforeningen, for ‘excellent time, good condition, and a well-planned race’. See Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1898 samt vinteren 1898-1899, 104.

46 See for example ‘Marathonløbet’ [‘The Marathonrace’], Norsk idrætsblad, September 2, 1897 (no. 35), 293–4.

47 Magelsen included for example a quantitative category of the relation between pulse and breathing. He also underlined that an examination after the race not necessarily informed of how the runners had behaved themselves, and experienced the physical challenge, during the marathon. See Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1898, 104–5.

48 Norsk idrætsblad, August 19, 1897 (no 33), 297.

49 Sverre Gundersen and Edvard Nilsen, eds., Norsk friidretts historie fra 1896 til 1950 [Athletics in Norway from 1896 to 1950] (Oslo: Nasjonalforlaget, 1952), 40–1. See also ‘Mesterskabsstævnet i Kristiansand’ [‘The championships in Kristiansand’], Norsk idrætsblad, September 9, 1897 (no. 36), 302. Aftenposten, August 14, 1901 (no. 554), noted that the marathon in Stavanger would be mostly flat course, and that runners in Kristiania should prepare for this.

50 In 1898, the newspapers told of several hundred spectators, besides the marathon-course just outside the capital Kristiania. See ‘Marathonløbet’ [‘The Maratonrace’], Bergens Annonce-Tidende, September 14, 1898 (no. 273). (The article had originally been printed in the newspaper Verdens Gang.) In 1899, as another example, a letter to the sports magazine deeply encouraged Norwegian runners to start training for the forthcoming marathon, as he knew that several Danish athletes were well prepared. See ‘Marathonløbet til høsten’ [‘The Marathonrace in the coming autumn’], Norsk idrætsblad, July 20 (no. 29), 357 (it was signed by ‘N.N.’).

51 Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1899 samt vinteren 1899-1900, 126–7.

52 Centraforeningen, Aaarsberetning for 1900 samt vinteren 1900-1901, 134. The class for those who had won a prize previously, was called ‘senior’.

53 Norsk idrætsblad, August 25, 1898 (no. 34), 538–539. See also ‘Marathonløbet’ [‘The marathon race’] Bergens Annonce-Tidende, August 16, 1898 (no. 240). In the yearbook of the NSF, two of the Norwegian athletes who participated in Copenhagen (they had received financial support for the travel) wrote their reports from the race (Einar Nilsen and Hallstein Bjerke). See Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1898, 114–16.

54 See ‘Skandinavisk Marathonløb’ [‘Scandinavian marathon race’], Bergens Annonce-Tidende, August 19, 1901 (no. 240). The Marathon meeting in Sweden in 1903 attracted as many as 45 athletes. The Danish club could be translated in English as ‘The Workers Sports’ Association’.

55 Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1899 samt vinteren 1899-1900 (Kristiania: Steenske, 1900), 123–4.

56 Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1902 samt vinteren 1902-1903 (Kristiania: Steenske, 1903), 101–2.

57 Ørebladet, August 19, 1901.

58 See ‘Det Skandinaviske Marathonløb’ [The Scandinavian marathon race’], Dagens Nyheder, August 16, 1901, 2.

59 ‘Marathonløbets historie’ [‘The history of the marathon race’], Norsk idrætsblad, August 24, 1899 (no. 34), 416–17. The most valuable prize, at least worth 100 NOK, had probably been afforded by the organizers themselves in 1898, and then offered back by Martinus Olsen – as a prize for marathons the following years. See Arbeidet, August 16, 1898. According to another newspaper in Bergen, Mr Olsen and Hallstein Bjerke had finished the race in 1898 as very good friends, hand in hand. See ‘Marathonløbet’ [‘The maraton race’], Bergens Annonce-Tidende, August 16, 1898.

60 ‘Marathonløbet’, Norsk idrætsblad, June 17, 1897 (no. 24), 199.

61 See Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1898, 115–16. Bjerke’s report was titled ‘Marathonløbet i Kjøbehavn 1898’. He represented Tjalve at this occasion, and probably change to the athletic club before the season started. The other report, written by Einar Nilsen, representing Kristiania Idrætsforening, was not nearly as harsh in its criticism as Bjerke’s was.

62 Fast won the bronze medal in the Olympic Marathon in 1900 (Paris), where no Norwegians took part.

63 See Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1904, samt vinteren 1904-1905, 62. At least a later report from a Danish marathon race included elements of condition, or ‘Kondition’, see ‘Marathon-løbet’ [‘The marathon race’], Næstved Tidende. Sydsjællands Folkeblad, August 23, 1904, 2.

64 See ‘45 km paa 49.04’, Norsk idrætsblad, September 17, 1896 (no. 37), 298.

65 ‘Til Kr.a. idrætsforening’, Norsk idrætsblad, July 27, 1899 (no. 30), 370–1. Thorp would later become an editorial staff, and in 1903 even editor of Norsk idrætsblad. He should not be perceived as representing opposition to amateurism in sport, on the contrary, he worked for international cooperation and even Olympic Games, on terms of honour and what he self as ancient amateur values. See Pharo, Tjalve Hundred Years, 25, and Skjeldal, ‘“Kjærlighed”, “Sportsgribbe”, og “Cirkusartister”…’, 415–16.

66 Til Kr.a. idrætsforening’, Norsk idrætsblad, July 27, 1899 (no. 30), 370–1.

67 See ‘Kapridtene paa Bygdöbane’ [‘The races at Bygdøy’], Norsk idrætsblad, June 4, 1896 (no. 22), 176–7; Agder, April 18, 1896.

68 ‘Hr. Gustav Thorp’, Norsk idrætsblad, August 3, 1899 (no. 31), 31–2.

69 And besides this: Interval-start had for long been the rule in the celebrated national sport of cross-country skiing.

70 See ‘Norsk idrætsforbund’, Bergens Annonce-Tidende, August 27, 1901.

71 See Pharo, Tjalve Hundre Years, 27. Pharo perceives Hallstein Bjerke as the specializer among many allrounders in the athletic club Tjalve.

72 Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1901, 90–1.

73 Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1904, 62–3.

74 ‘Idrætslaget “Norrøna”’, Bergens Annonce-Tidende, May 30, 1902 (no. 362). In 1905, probably, the organizing club Norrøna introduced mass-start. A newspaper questioned this change of the traditional rules. See ‘Marathonløbet’, Bergens Tidende, September 4, 1905 (no 247).

75 ‘Marathonløb – 20 km. løb’, Norsk idrætsblad, June 7, 1906 (no. 23), 212. The letter was signed Bjarne Bratz.

76 According to a report from a gymnastics participant who won gold for the Norwegian gymnastics team, the only marathon candidate had had major health issues during the 1500-meters stadium run. The official leaders of the Norwegian team then did not allow him to start in the marathon, to no risk the newly won Norwegian honour. Joh. A. Haagensen, Athenfærden 1906: Nordmændernes deltagelse i de olympiske lege [The travel to Athens: Norwegian who participated in the Olympic Games’] (Kristiania: Stenersen, 1907), 107–9. Ugens Nyt, May 15, 1906 (no 56), gives an interesting account of the event in Athens. A Canadian, William Sherring, won the race in Athens this time.

77 ‘Marathon-Athen’, Norsk idrætsblad, May 10, 1906 (no. 19), 181.

78 Most recently, Mads Drange has written their common history as pioneers in women’s Marathon-running. Mads Drange, Rivalene: Grete Waitz, Ingrid Kristiansen og norsk idretts største duell [The rivals: Grete Waitz, Ingrid Kristiansen and the greatest duel of Norwegian Sports] (Oslo: Kagge, 2022).

79 Thor Gotaas, Femmila, 42, 55.

80 See for example Fridtjof Nansen, The First Crossing of Greenland (London: Longmans, Green and Co, 1890), and Fritz Huitfeldt, Skiløbning I Text og Billeder [Skiing in text and pictures] (Kristiania: Jacob Dybwads forlag, 1908).

81 Olstad, Norsk idretts historie, 115–17.

82 See as one striking example Fridtjof Nansen, Paa ski over Grønland [‘On skies across Greenland’] (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1890). The concept ‘invented tradition’ relates to the book of Eric Hobsbawm and Therence Ranger, The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). [First edition 1983].

83 The Portugese Francico Lázaro did not finish his race in Stockholm, and died the following day, probably of sunstroke. See Thor Gotaas, Løping, en verdenshistorie [‘Running: A world history’] (Oslo: Gyldendal, 2008) 152–4.

84 Arve Hjelseth, ‘Idretten i samfunnet – samfunnet i idretten’ [‘Sport in society – Society in sport] in Tanker om samfunn [Thoughts on society], ed. K. Dahlgren and H.E. Næss (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2012), 172–95.

85 Glenn-Eilif Solberg, ‘En militarisert sport? Skiskytingens tidlige utvikling i Norge’ [‘A Militarized Sport? The Early History of Biathlon in Norway’], Historisk tidsskrift, 100, no. 1 (2021): 6–21.

86 Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1896, 149–50.

87 Richard Holt, ‘The Amateur Body and the Middle-Class Man: Work, Health and Style in Victorian Britain’, Sport in History, 26, no 3 (2006): 352–69. Although Holt concentrates on English (and London) sports, his discussion and theories concerning amateurism a sports ideology should not be constricted to Great Britain.

88 The sports magazine was founded in 1881, when Sigvart Petersen was the editor (until 1888). Hagbarth Wergeland relaunced the periodical in 1891, editing it (mostly) until 1907. A very significant drawing, followed by a poem, underlining this outdoor amateurism in a Norwegian context, was printed in Norsk idrætsblad, January 25, 1884 (no. 2), frontpage.

89 Pål Augestad, Skolering av kroppen: Om kunnskap og makt i kroppsøvingsfaget [‘Schooling of the body: On knowledge and power in physical education’] (PhD.diss, Høgskulen i Telemark, 2003), 62–3.

90 My transl. Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1896, 15. [‘Følgen af denne specialuddannelse var atter, at den store mængde gik over til kun at være tilskuere, og at kampen om hæderspriserne kun kom til at finde sted mellom nogle faa, der drev det som haandværk eller levebrød, athleter og professionister. Og hermed var det hele i absolut forfald.’].

91 See Skjeldal, ‘“Kjærlighed”, “Sportsgribbe”, og “Cirkusartister”, 400, 456.

92 Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1904, 65.

93 A list of rules published in 1899 (almost as the ten commandments) concerning competition and training, highlights the focus on health in Norwegian Sports Federation, and Seeberg’s close collaboration with medical expertise. See Centralforeningen, Aarsberetning for 1898, 20–2.

94 Goksøyr emphasizes how important the allrounder was to Norwegian sports-authorities. Matti Goksøyr, Historien om norsk idrett [The Norwegian sports history] (Oslo: Akilles, 2022), 59.