ABSTRACT

The present study describes a digital storytelling project about promoting a tourist destination using photographs taken by students in an English for tourism course taught in a Portuguese higher education institute. This work aims to explain how a digital storytelling project was used to enrich students’ knowledge of the English language while recycling content from their core degree subjects and enhance their 21st century skills. The stories created were based on students’ viewpoints of the city where they study and live enabling them to convey their emotions and opinions to promote it as tourist destination from a unique perspective. The results indicated that learner generated content positively impacted the students’ engagement in their English foreign language learning process. It was through the use of art and creativity that this project gave students the opportunity to also build on their communication, collaborative and critical thinking skills, all needed to succeed in the professional world in tourism.

1. Introduction

This generation of university students are digital natives who enjoying taking photos and even go to great lengths to capture the perfect one (Diehl et al., Citation2016; Suciu, Citation2019). Images are so important to these young adults that many would choose a holiday destination solely based on how well it would look in a photograph in order to be later posted on social media (Dewi et al., Citation2020; Salazar, Citation2021). Given this information, it is not surprising that the importance of images in marketing a tourist destination, although not new (Hunt, Citation1975), has grown substantially. Tourism destination image is a concept from the tourism field that refers to the perceptions a tourist destination has on people when choosing a holiday destination (Xiao et al., Citation2020). And in this pre-travel phase, storytelling in the first person alongside an image is considered to be an important marketing tool that significantly “increases engagement on social media, destination brand image, and tourist visit intentions” (Pachucki et al., Citation2021). It is therefore a relevant topic that any higher education student studying English in a Tourism and Hospitality degree needs to be familiar with today. Hence, the project presented in this paper aimed to combine the love second year undergraduate Tourism students have for photography with the importance of images and storytelling in promoting a tourism destination, in order to motivate and prepare students to communicate effectively in English when reaching the professional world.

Implementing a digital project of this nature in an English for Tourism course in higher education is challenging when taking into consideration the goals of the course, time constraints and large class sizes. In any Languages for Specific Purposes (LSP) classroom, the teachers’ ultimate goal is to teach the foreign language while preparing students to use that language as a means to develop other digital literacies skills and competences that will enable them to be productive when entering the workforce (Arnó-Macià, Citation2014). This goal at times is not attainable because many LSP teachers find themselves using topic-centered syllabi that place considerable focus on acquiring the subject matter and specialist vocabulary and less emphasis on developing twenty-first century skills that are required by employers (Knezović, Citation2016; Rios et al., Citation2020). These skills include media and information literacy, critical and creative thinking, problem-solving and analytical skills, effective written and oral communication, as well as collaborative work and social skills, all of which are necessary to make university graduates more competitive in everyday professional environments (Carlisle et al., Citation2021; Davies et al., Citation2018; Denson & Bowman, Citation2013). Although combining these 21st century skills with foreign language skills in an LSP classroom is not an easy feat, it can be possible with the use of ICT tools that can create a myriad of creative learning environments that support the development of these skills in higher education students. One such pedagogical tool that has been proven to be effective in bridging the gap between the professional world and the higher education world is digital storytelling.

Digital storytelling has been the object of many studies in LSP contexts (Fan, Citation2022; Lestari & Nirmala, Citation2020; Pollard & Olizko, Citation2019; Purba et al., Citation2022) given its main characteristic of using multimedia technology to help learners express themselves in a foreign language. Many studies have reached the conclusion that digital storytelling not only motivates students to learn the foreign language but also engages them more while helping them develop their productive skills, speaking and writing (Castaneda, Citation2013; Fu et al., Citation2021; Hava, Citation2019; Kallinikou & Nicolaidou, Citation2019; Mojtaba et al., Citation2017). But what is digital storytelling?

Digital storytelling is a multimedia approach that takes the ancient art form of storytelling to the modern technological world by integrating and interacting different modes of communication, such as images, audio, and video. This concept was made known in the 1990s by The Center for Digital Storytelling who since then have been providing workshops and resources for young people and adults in creating and sharing personal stories using a combination of different digital media tools (Lambert, Citation2009; StoryCenter, Citationn.d.). It is no surprise that it was introduced to educational settings to increase students’ motivation and engagement in learning tasks; to consolidate knowledge and skills; to improve research, writing and presentation skills; to develop digital literacy skills; and to promote reflection, critical thinking and social skills (Yuksel et al., Citation2010). To successfully incorporate digital storytelling in education, teachers need to aid students in the entire digital storytelling process. According to Morra (Citation2013), there are eight steps involved:

Step One: Come up with an idea. Write proposal.

Step Two: Research/Explore/Learn

Step Three: Write script

Step Four: Storyboard/Plan

Step Five: Gather and create images, audio and video

Step Six: Put it all together

Step Seven: Share

Step Eight: Reflection and Feedback

These eight steps provide educators the necessary guidance to integrate this pedagogical tool in their classroom, regardless of the content area.

English as a foreign language is one such content area where digital storytelling has been proven to show positive effects in learners. Some studies have shown that digital storytelling improves students’ speaking skills in English, enhancing their fluency and pronunciation (Fu et al., Citation2021; Kallinikou & Nicolaidou, Citation2019; Mirza, Citation2020; Tyrou, Citation2022). Others have focused on how digital storytelling can increase students’vocabulary in English, making lexical items more meaningful and relevant to their own experiences (Hava, Citation2019; Leong et al., Citation2019; Mojtaba et al., Citation2017). Whereas others have studied the effectiveness of this digital pedagogical tool in improving students’ writing skills (Hava, Citation2019; Mojtaba et al., Citation2017; Tanrıkulu, Citation2020; Tyrou, Citation2022). In addition to specific English language skills, studies have indicated that creating digital stories give students the opportunity to generate, evaluate and improve ideas together thus allowing them to build on their collaboration skills and critical thinking skills while becoming more creative thinkers (Belda-Medina, Citation2021; Yang et al., Citation2020). All the studies cited above have also highlighted how digital storytelling increases motivation and satisfaction levels which in turn helps learners develop their English competence.

The project in this paper also examined the importance of digital storytelling in developing English language competence in Tourism higher education students centered on the topic of tourism destination image. Images have always been used in foreign language teaching to aid teachers in lessons and serve as prompts to help students develop their productive skills (Foutsitzi, Citation2022; Qiu, Citation2019; Zhang & Zou, Citation2021). Photographs more specifically have also been the object of some studies in the foreign language learning. In one particular study, researchers found that photographs were a motivational factor for improving writing (Megawati & Alkadrie, Citation2017). JASM, a multilingual awareness project aimed at media students learning foreign languages in higher education, also used photographs as a supplement to the migrant documentaries students created using digital storytelling (Costa et al., Citation2020). Another study analysed the benefits of student-generated photographs to enhance speaking performance by building on students’ schematic knowledge making them more active and in control of the materials hence aiding “the activation of relevant linguistic knowledge, thus reducing the mental effort and enhancing the speech production” (Huynh et al., Citation2022).

The literature review presented indicates that digital storytelling and the use of learner-generated photographs help students become more active in their foreign language learning while also aiding them in developing the 21st century skills that are required by the workforce today. Therefore, this work aims to answer the following questions:

To what extent does a digital storytelling project about promoting a tourist destination enrich English for tourism students’ knowledge of the English language while recycling content from their core degree subjects?

Does student generated content in learning English for tourism enhance 21st century skills?

The following sections describe the Shutterbug project and how it was implemented. Two examples are given which illustrate the students’ outputs. The last section addresses how the project was assessed.

2. The shutterbug project

2.1. Project overview

The Shutterbug Project was developed by two English teachers for forty-eight second year undergraduate tourism students in an English course. The syllabus of this course revolves around tourist attractions, art and guided tours. Among other things, students are expected to provide information and facts about cultural, historical and contemporary heritage as well as describe buildings, artwork and monuments. They should also be able to give advice and suggestions on tourist attractions and prepare and lead a guided tour. The contents were chosen based on the fact that these students have already studied the following subjects in semesters previous to this English course: History of Culture and Art, Heritage Tourism, and Tourism Marketing. The Geography and Tourism Itineraries course as well as the Tourism Products course are taught in the same semester which led some groups to attempt to choose themes that were covered in these courses.

Based on the students’ schematic knowledge in the Tourism area, the Shutterbug Project aimed to integrate two different pedagogical strategies: digital storytelling and photography to increase students’ motivation level when learning English for Tourism while also helping to prepare them for the professional world. It is the use of art and creativity that this project proposes to help students express ideas and personal experiences about the city where they are studying in order to promote it as a tourist destination for others who may choose to visit it. To successfully carry out this project, partnerships were established with the Viseu tourism office as well as the museums in the city and other institutions related to tourism.

Therefore, the aims of this project were:

to provide students the tools needed to learn lexical items and language structures in English about the visual arts that will allow them to put into practice the English language for future use if they choose to be tour guides, tourist information officers, hotel receptionists (giving information to tourists about local culture).

to increase student’s level of confidence in their written and oral communication in English within the visual arts context to be able to work as tour guides or other tourism information providers.

to develop student’s digital literacies skills as well as their critical and creative thinking skills, problem-solving and analytical skills to help them enter the competitive tourism job market.

to strengthen the ties between higher education and the community.

This project was worth 30% of students’ overall grade and it carried out in groups of two or three students throughout the Spring semester. Overall, students had to complete four different tasks (see ).

Table 1. Shutterbug project task overview.

Before starting the Shutterbug Project, a needs analysis survey was developed on Google Forms in order to find out how important photography is for students and what their perceptions are about the role of photography in tourism. Conducting a needs analysis for this project was vital because it aided teachers in deciding whether the tasks were relevant and appropriate for the students (Malicka et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the survey was divided into four sections related to: the role of photos in students’ lives; photography in tourism; photography and English language learning; Viseu as a tourist destination. This survey was validated by a tourism expert, a photographer and two third year tourism students.

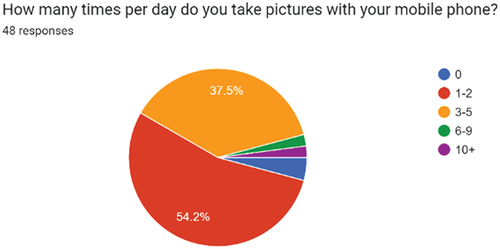

The results of this survey indicated that the majority of students (80%) likes taking photos, which is in line with the theoretical framework (Diehl et al., Citation2016; Suciu, Citation2019). Only 4% of the students do not take pictures with their mobile phones on a daily basis (see ) and those who do, share them occasionally (44%) or sometimes (33%) on social media.

They stated that their main motivations to do so were: staying connected and maintaining relationships (66.7%), communicating (43.8%) and showing others what they are doing (31.3%).

As far as photography and tourism are concerned, most of the students agreed that photography makes people more aware of their surroundings (76%) and all of them concur that photos help remember a tourist destination and that they have an impact on tourism. A third strongly agreed that people choose holiday destinations based on photos they have seen on social media. Moreover, the majority of the students strongly (46%) or moderately agree (29%) that a great tourist destination photo tells a story.

Given that the project was implemented in an English for tourism course, it was also important to find out students’ perceptions on how the project could impact their language learning process. Students were asked to choose from a list of five items: speaking, writing, vocabulary, grammar and motivation, which they considered to be the most important for them when using photos to improve their English language competence. The three most chosen, in the order of preference, were: motivation, speaking and vocabulary. This is in line with research which has shown that photos are a motivation factor when learning a foreign language (Megawati & Alkadrie, Citation2017).

In the last section of the survey, the teachers wanted to find out how the students would describe the city of Viseu to someone who has never visited it. This was an open-ended question and after applying content analysis on the answers, three characteristics were most commonly found: “history”, “green spaces” and “best city to live”. The following excerpt is an example:

Viseu is a very quiet city and great for people who like nature and enjoy visiting religious monuments. From the historical monuments like the Sé de Viseu with unique architectural styles to the Rossio de Viseu where you can see the city life.

The overall results of this needs analysis survey were a strong indication that the students understood the relevance of a project of this nature and therefore would be actively involved in the different stages of the project. The next section describes how each stage was implemented.

2.2. Project implementation

Students were introduced to the project in the first class of the semester. They were also encouraged to take advantage of content from other tourism related courses from their degree, namely History of Culture and Art, Heritage Tourism, Geography and Tourism Itineraries, Tourism Products and Tourism Marketing. In the guided tour of Viseu, they visited and learned about the main tourist attractions in the city, some of its unique aspects and legends, as well as important personalities and events. In addition to this general tour, other tours to specific places were arranged based on each group’s theme to help them in their story building process. This gave them the opportunity to go into the community and have deep, thoughtful conversations with the locals to discover the traditions of the places.

The photography workshop, conducted by a photographer, introduced students to discursive spaces of photography, the position of the photographer’s gaze, the power of image in the tourist context. The workshop aimed to provide students with a wide array of experiences so that they could learn how to work their photographic equipment and understand all of its potential. This in turn allowed students to see the fruitful relationship between the specific know-how of photography and the general perspectives of the tourist experience. Students also studied the relationship between photographic language and digital media platforms, in order to make places, cultural contents and society stand out in environments that are already saturated with images.

As far as storytelling is concerned, students were first introduced to the topic in class through a workshop. This activity allowed them to explore a painting, a photo and a contemporary sculpture.

To encourage students’ participation and engagement, some gamification tools were used, namely Mentimeter, Genially and Wordwall (Membrive et al., Citation2020). This workshop allowed participants to give free rein to their imagination, encouraging them to become involved in the thoughts and feelings of the characters depicted in the artworks, knowing that things may not always be as they first seem. Storytelling can also involve creating new characters and devising new interactions beyond what is visible, taking the artwork as a starting point, and using it as a stepping stone to create a whole new narrative, scenarios, dialogue and themes.

As a follow-up activity, each student had to choose a painting and tell their own story based on it. This was an individual five-minute presentation where they had to talk about the identification of the painting first and then narrate their own story. In total, there were 44 different presentations. Some students chose paintings that have ready-made stories as they depict myths or stories from the Christian faith and found it difficult to apply skills such as prediction, guessing, or hypothesizing. Others chose world famous paintings, which have already been the object of many stories, and also found it difficult to add something of their own. However, the majority of the students chose paintings they could relate to, and because of that they were able to vividly present their story and gauge how the characters felt and the reasons behind that. Many students chose Genially to present their painting, which they learned about during the workshop.

In the following task, as future tourism professionals, students were challenged to think about the city where they study, Viseu and its potential as a tourist destination and communicate these ideas visually in a photograph and orally in a digital storytelling format. To accomplish this, first they had to choose a subject that best represents Viseu as a tourist destination. The next step was taking a photo that would showcase their subject. Additionally, each group member would take another photo to further explore details of the original photograph, resulting in a photo within a photo. However, there had to be a connection between all the photos with a common story, keeping in mind the main idea: Viseu as tourist destination.

The final product had to combine different modes (image, text and audio) and students could choose the tool and format they preferred to tell their story. Only two approaches were chosen: PowerPoint presentation and video format. Thirteen groups chose the former, while other 8 presented their story using the latter format. Overall, there were 21 projects, which were organized in four different categories: historical figures; landmarks; art; customs and traditions (see ).

Table 2. General categories of the Shutterbug project outputs.

The projects from the category “historical figures” highlighted the role and importance of certain personalities in the development of the city. In most cases the group photo showcased a statue and students managed to unfold a story and create their own narrative, intertwining the life of the character and the development of the city. In the category “landmarks”, group photos depicted some of the main hotspots in the city, as well as some hidden gems. In some stories, students were able to go beyond physical space and evoke a psychological reality, consisting of emotions and past events. The category “art” encompassed projects that had painting, sculpture, museums as their main theme. Most of the stories aimed at connecting visitors with experiences involving the senses, or combining different types of art, blending renaissance paintings with street art and offering unique experiences. Finally, the projects classified in “customs and traditions” centered around genuine local experiences focusing on people and their traditions. For example, the project “Old Stor(i)es” was about stores and their owners that have been there for so long that they are now part of Viseu’s history.

2.3. Examples of Shutterbug projects

The two projects described in this section are examples of different types of students’ outputs. The first one was chosen to exemplify how students, who are not from Viseu, managed to collect information about their theme using an original approach no other group used to help tell their story. The other project was a good example of students’ ability to recount past events from their own perspective while empathetically involving the viewer.

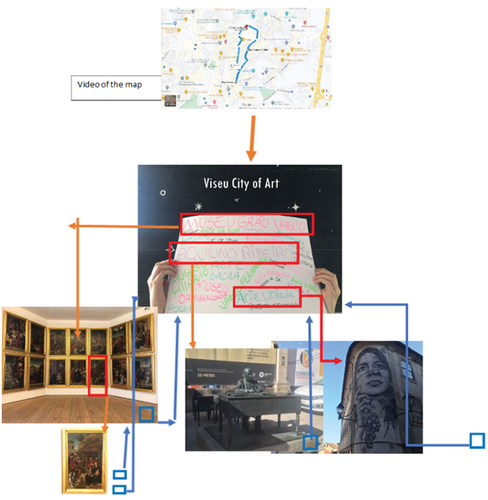

The project “Viseu: a city of art” stood out because of the approach students used, which involved using the voices of the local people. They spent an afternoon walking around the city and asking people the first word that came to their mind when they heard the expression “Viseu: a city of art”. Based on the information they gathered, they created a poster with the most common words and took a photo of it. This was the main photo of their project and the starting point for their storyboard. Subsequently, each member chose a word and decided on the best photo to showcase it. The following excerpt is the introduction to their story:

Art is an underestimated, yet key element, in the construction of a city, helping connect people with the history and culture of the place they live in.

The city of Viseu is imbued with art, as it was home of many kings, poets, and painters, such as King D. Duarte or the famous Renaissance painter Vasco Fernandes, both major figures in the history of not only Viseu, but Portugal as a whole.

This photograph is meant to highlight the people and places that are an integral part of the history of art in Viseu, according to what the citizens of this city think when they hear the phrase “Viseu: City of Art”.

The individual photos students took were then organized according to the narrative above, which resulted in an itinerary. The group selected a painting from the Grão Vasco Museum, a sculpture of a famous writer (Aquilino Ribeiro) and an example of street art, which can be seen in their interaction plan ().

This plan shows how these students combined different types of art and art periods found in Viseu. This information was not new to them, since they had already learned about art and art periods in the History of Culture and Art course, where they had had a guided tour of the Grão Vasco Museum.

The other project, “A Journey to the Origins of the City”, also deserves attention because the students were able to describe traditions found on the emblematic tiles panel in the city square, Rossio, speculating about the feeling and emotions of the characters displayed. The group’s photo (see ) is the focal point of the story, which takes us back in time to a rural Viseu.

According to this group, the main goal of the project is to “show the everyday life of peasants in the past. Our theme takes us back to the past and with it we intend to promote Viseu through its history. We want tourists to know about the customs and traditions that make this city unique.”

One of the students (Student A) chose to focus on the scene represented in and speculated about the daily activities of the past in the Rossio.

Below is an example of the script this group created for the storyboard. It was included in the project as an audio.

But going to the fair didn’t mean just taking crockery to sell, this was a meeting place for couples, a place away from their parents where they could flirt and get to know each other better. Without the accompaniment of their mothers or the presence of relatives they take this time to meet. We can see several men accompanied by ladies, which gives us the idea that they are talking. As in the old days everyone knew each other, but dating is not like today, this was the only way they could get together. Here they stayed until late afternoon, just before the sun went down, these ladies and gentlemen went home to their lives, the day was done and the tasks were long, the next day would be another day of work.

Bringing the characters displayed in the tiles panel to life, students created this narrative that enriched their story and were still able to describe traditions and habits of the past. By creating a connection between the time and place, the viewer is able to understand the scene depicted and the feelings that arise from it.

2.4. Project assessment

The final digital storytelling product submitted by each group was assessed by means of a rubric that was based on the previous work of Barrett (Citation2006) and the University of Houston (Citation2022). The criteria for assessing the Shutterbug Project were the following:

Content and theme

Creativity

Photos

Storyboard

English Language

The content and theme category aimed to assess how the group was able to choose a theme and content to promote the city and establish a purpose early on, maintaining a clear focus throughout the project. All groups, with the exception of one were able to identify a theme that captured the essence of the city, going beyond a mere selection of a city landmark and adding their personal contribution, thus showing evidence of critical thinking skills. The students involved in the project “Infante D. Henrique statue” were not able to build a connection between the historical figure and the city. This group limited their project to the statue. Overall, the content is relevant to story and theme. To create their stories, all groups researched information about aspects of their theme, which allowed them to interconnect the different elements to create a coherent and meaningful story.

By performing research and familiarizing themselves more with the themes chosen, groups were able to create original and creative projects. Even though some groups promoted the city the way it has always been done, most of them managed to create stories that can enrich tourists’ experiences in different nuanced ways. One group, “Viseu, city of art”, mentioned in the previous section, interviewed people on the streets of the city to obtain information that would allow them to present different perspectives about their theme, making their project unique. Another group project, “Old and new”, centered their narrative around an iconic painting of a local baroness from the 19th century displayed in the Grão Vasco Museum, the “old” part of their project and connected it to a street art form depicting the same baroness found on an electrical box not far from the museum, the “new” part of their project.

Another category, photos, was assessed. The main focus was on relevancy rather than on quality due to the fact that the project was created in an English for tourism course. The photos taken by students were relevant and matched the different parts of their stories. However, throughout the project, some groups had difficulties identifying the best shot for their themes because they wanted to illustrate abstract concepts that are not easy to visually represent. An example is the “LoVisEu” project. This group wanted to incorporate the idea of “love” which is found in a famous song about the city, “Indo eu, Indo eu”, with parts of the city where couples can fall in love.

The storyboard is a vital part of the project. This is where the groups were putting together their content, photos and other media to tell their story about the city they were promoting. This visual representation of the storyline allowed students to carefully map out their ideas and write out their scripts to help them create their final multimedia product. All groups were able to create their storyboards, but some had more difficulties and needed more guidance. For example, the project “Memories of Viseu”, had difficulties connecting their photos to the theme. Despite being able to decide on a group photo and initial storyline, the group had difficulties connecting each individual photo to the theme chosen.

The last category, and one of the most important, was English language. Here the focus was on the use of language structures, vocabulary, pronunciation and fluency. Given that students worked on the project throughout the semester, editing and getting feedback from the teachers, mistakes were minimum and did not detract from the story. For example, vocabulary and language structures was not an issue because specific terminology related to the topics (e.g., art, describing a building, etc.) was covered in class. Pronunciation and fluency in most of the projects needed more attention. Having a written script prevented some students from producing natural speech because they read what they had written. This was noticeable in the audio part of the project.

3. Discussion and conclusions

The current paper explored how digital storytelling and the concept of destination image were combined to enhance English for tourism students learning of the foreign language and promote their interdisciplinary work from their tourism degree while simultaneously developing their 21st century skills. The Shutterbug Project allowed students to become creators of content by using original photos they took to promote the city where they study as a tourist destination. This group project gave students the opportunity to work individually and collaboratively on the project allowing them to build on communication skills, collaborative skills, critical thinking skills and creativity skills all needed when entering the workforce in tourism. But with a project of this nature there are successes and challenges.

As far as the successes are concerned, the results of the project indicated that students increased their level of confidence in their written and oral communication in English within the cultural context of tourism namely when referring to lexical items concerning art and architectural features, as well as to language structures related to describing places and guiding. In addition to developing their linguistics skills, they also deepened their knowledge of tourist attractions in the city where they study, strengthening the ties between the higher education institute and the local community. This was possible due to the prior knowledge they possessed from other more specific tourism related courses they study in their degree. The stories created in each project were based on students’ perceptions and experiences they had lived while studying in the city they were promoting. It was through this digital storytelling project that students were able to convey their emotions and opinions to describe Viseu to tourists. As future tourism professionals, this can help them build stronger ties with the people and places of any tourist destination because “stories about places are also the essential memory of tourism service experiences” (Bassanoa et al, Citation2019: 11).

Understanding the successes of a project is important to validate its worth, but it is equally important to reflect and identify challenges that arise in order to adapt and improve the project for future use. The main challenge of the Shutterbug project for most groups was selecting a theme for the story. In the initial stage of the project, they were too focused on the subject of their group photo, and had difficulties creating a narrative that would connect all the individual photos. To overcome this challenge, the teachers presented an example of a promotional video using storytelling about another Portuguese city that went viral during that time. This video along with group meetings with the teachers, helped put students on track to create their projects. Another challenge was combining all the different media in their final project. Despite devising an interaction plan and a storyboard, some groups had difficulties choosing the best medium to convey their narratives. For example, several groups displayed the same information in both written and audio formats. Some had long audios (more than a minute and half) for the same image, which distracted the viewer.

Despite these challenges, the Shutterbug project integrated two different pedagogical strategies: photography and digital storytelling to increase students’ engagement when learning English as a foreign language while also helping to prepare them for the professional world in the tourism field. This project proposed to help students express ideas and personal experiences about the city where they are studying in order to promote it as a tourist destination for others who may choose to visit it one day.

Although the project described in this paper has revealed some interesting contributions about the integration of art and creativity along with digital storytelling in an English for tourism course, it still has some limitations and future research is needed. This paper described the process of this project from the teachers’ perspective, further studies are needed to address tourism students’ perspective about the impact digital storytelling projects have on their foreign language learning.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by National Funds through the FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., within the scope of the project Refª UIDB/05507/2020 and DOI identifier https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/05507/2020. Furthermore, we would like to thank the Centre for Studies in Education and Innovation (Ci&DEI) and the Polytechnic of Viseu for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arnó-Macià, E. (2014). Information technology and languages for specific purposes in the EHEA: Options and challenges for the knowledge society. In E. Bárcena, T. Read, & J. Arús (Eds.), Languages for specific purposes in the digital era (pp. 3–25). Springer.

- Barrett, H. (2006). Researching and evaluating digital storytelling as a deep learning tool. Proceedings of SITE 2006–Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference. In C. Crawford, R. Carlsen, K. McFerrin, J. Price, R. Weber, & D. Willis. Eds. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE), Orlando, Florida, USA. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/22117/. last accessed 2022/09/10.

- Bassano, C., Barile, S., Piciocchi, P., Spohrer, J. C., Iandolo, F., & Fisk, R. (2019). Storytelling about places: Tourism marketing in the digital age. Cities, 87, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.12.025

- Belda-Medina, J. (2021). Promoting inclusiveness, creativity and critical thinking through digital storytelling among EFL teacher candidates. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.2011440

- Carlisle, S., Ivanov, S., & Dijkmans, C. (2021). The digital skills divide: Evidence from the European tourism industry. Journal of Tourism Futures, 9(2), 240–266. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-07-2020-0114

- Castaneda, M. E. (2013). “I am proud that I did it and it’s a piece of me”: Digital Storytelling in the Foreign language classroom. CALICO Journal, 30(1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.11139/cj.30.1.44-62

- Costa, A. M., Amaro Costa, C., Coutinho, E., Oliveira, I., Pereira, J., Garcia, P., Roush, P., Gillain, R., Amante, S., Fidalgo, S., Relvas, S., & Delplancq, V. (2020). JASM: Active pedagogy for foreign language learning in higher education. 13th International Conference Innovation in Language Learning, Italy.

- Davies, I., Ho, L., Kiwan, D., Peck, C. L., Peterson, A., Sant, E., & Waghid, Y. (2018). The Palgrave handbook of global citizenship and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Denson, N., & Bowman, N. (2013). University diversity and preparation for a global society: The role of diversity in shaping intergroup attitudes and civic outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, 38(4), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.584971

- Dewi, N. I. K., Gede, I. G. K., Kencanawati, A. A. A. M., & Mataram, I. G. A. B. (2020). Social media usage by generation Z in pre-trip planning. Proceedings of the International Conference on Science and Technology on Social Science (pp. 190–195). Atlantic Press.

- Diehl, K., Zauberman, G., & Barasch, A. (2016). How taking photos increases enjoyment of experiences. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 111(2), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000055

- Fan, Y.-S. (2022). Facilitating content knowledge, language proficiency, and academic competence through digital storytelling: Performance and perceptions of first-year medical-related majors. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 56(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2022.2110337

- Foutsitzi, A. (2022). Images in educational textbooks and educational audiovisual media. European Journal of Language and Literature, 8(2), 26–32.

- Fu, J. S., Yang, S.-H., & Yeh, H.-C. (2021). Exploring the impacts of digital storytelling on English as a foreign language learners’ speaking competence. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 1–16.

- Hava, K. (2019). Exploring the role of digital storytelling in student motivation and satisfaction in EFL education. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(7), 958–978. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1650071

- Hunt, J. D. (1975). Image as a factor in tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 13(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757501300301

- Huynh, T. N., Lin, C. J., & Hwang, G. J. (2022). Learner-generated material: The effects of ubiquitous photography on foreign language speaking performance. Educational Technology Research & Development, 70(6), 2117–2143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10149-1

- Kallinikou, E., & Nicolaidou, I. (2019). Digital storytelling to enhance adults’ speaking skills in learning foreign languages: A case study. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 3(3), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti3030059

- Knezović, A. (2016). Rethinking the languages for specific purposes syllabus in the 21st century: Topic-centered or skills-centered. International Scholarly and Scientific Research & Innovation, 10(1), 117–132.

- Lambert, J. (2009). Where it all started the center for digital Storytelling in California. In J. Hartley & K. McWilliam (Eds.), Story circle: Digital storytelling around the world (pp. 79–90). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Leong, A. C., Zainol Abidin, M. J., & Saibon, J. S. (2019). The benefits and drawbacks of using tablet-based digital storytelling in vocabulary learning among Malaysian young English as a Second language (ESL) learners. Asia Pacific Journal of Educators and Education, 34, 17–47. https://doi.org/10.21315/apjee2019.34.2

- Lestari, R. P., & Nirmala, D. (2020). Digital Storytelling of English advertisement in ESP teaching in Indonesia. EduLite: Journal of English Education, Literature and Culture, 5(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.30659/e.5.1.66-77

- Malicka, A., Gilabert Guerrero, R., & Norris, J. M. (2017). From needs analysis to task design: Insights from an English for specific purposes context. Language Teaching Research, 23(1), 78–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817714278

- Megawati, M., & Alkadrie, S. A. (2017). The effectiveness of using photograph in teaching writing. JETL (Journal of Education, Teaching and Learning), 2(2), 138. https://doi.org/10.26737/jetl.v2i2.277

- Membrive, V., Armie, M. S.-T., & IGI Global. (2020). Gamification, and Videogames: A case study to teach English as a second language. In V. Membrive & M. Armie (Eds.), Using literature to teach English as a second language (pp. 122–141).

- Mirza, H. S. (2020). Improving university students’ English proficiency with digital storytelling. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching (IOJET), 7(1), 84–94.

- Mojtaba, T., Pushpinder, S., & Sanaz, M. (2017). Enhancing vocabulary and writing skills through digital storytelling in Higher Education. i-manager’s Journal of Educational Technology, 14(3), 40. https://doi.org/10.26634/jet.14.3.13858

- Morra, S. (2013, June 05). 8 steps to great digital storytelling. Transform learning ~ written by Samantha Morra.Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://samanthamorra.com/2013/06/05/edudemic-article-on-digital-storytelling/

- Pachucki, C., Grohs, R., & Scholl-Grissemann, U. (2021). No story without a storyteller: The impact of the storyteller as a narrative element in online destination marketing. Journal of Travel Research, 61(8), 1703–1718. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211046052

- Pollard, D., & Olizko, Y. (2019). ART and ESP INTEGRATION in TEACHING UKRAINIAN ENGINEERS. Advanced Education, 6(11), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.20535/2410-8286.147539

- Purba, A., Girsang, S. E., Silalahi, T. F., & Saragih, E. (2022). Improving nurses’ esp communicative competence by digital storytelling method. International Journal of Education and Learning, 4(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.31763/ijele.v4i1.530

- Qiu, X. (2019). Picture or non-picture? The influence of narrative task types on lower- and higher-proficiency EFL learners’ oral production. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 60(2), 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2017-0094

- Rios, J. A., Ling, G., Pugh, R., Becker, D., & Bacall, A. (2020). Identifying critical 21st-century skills for workplace success: A content analysis of job advertisements. Educational Researcher, 49(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19890600

- Salazar, M. G. Z. When real meets digital. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from https://blog.nixplay.com/2019/11/gen-z-when-real-meets-digital/

- StoryCenter. STORYCENTER. (n.d.). Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://www.storycenter.org/

- Suciu, P. (2019, October 24). A photo used to be worth a thousand words, but thanks to social media photos have lost their value. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/petersuciu/2019/10/24/a-photo-used-to-be-worth-a-thousand-words-but-thanks-to-social-media-photos-have-lost-their-value/?sh=3d3d86fa607f 2022/02/11.

- Tanrıkulu, F. (2020). Students’ perceptions about the effects of collaborative digital storytelling on writing skills. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(5–6), 1090–1105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1774611

- Tyrou, I. (2022). Undergraduate students’ perceptions and attitudes about foreign language-related digital storytelling. International Journal of Education (IJE), 10(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.5121/ije.2022.10104

- University of Houston, Rubrics. (2022). Educational uses of digital storytelling. Retrieved September 10, from http://digitalstorytelling.coe.uh.edu/archive/rubrics.html

- Xiao, X., Fang, C., & Lin, H. (2020). Characterizing tourism destination image using photos’ visual content. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(12), 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9120730

- Yang, Y.-T. C., Chen, Y.-C., & Hung, H.-T. (2020). Digital Storytelling as an interdisciplinary project to improve students’ English speaking and creative thinking. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 840–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1750431

- Yuksel, P., Robin, B. R., & McNeil, S. (2010). Educational uses of digital story- telling around the world. Elements, 1, 1264–1271. http://digitalstorytelling.coe.uh.edu/survey/SITE_DigitalStorytelling.pdf

- Zhang, R., & Zou, D. (2021). A state-of-the-art review of the modes and effectiveness of multimedia input for second and Foreign language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(9), 2790–2816. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1896555