ABSTRACT

This primary school teachers’ (1CEB) community of practice started its activity in the school year 2020/2021, being organized around three main goals: i) implement a small community of practice with 1CEB teachers, focusing on issues related to the curricular integration of Digital Technologies (DT); ii) create lesson plans and other materials for the 1CEB, where DT assume its role of cross curricular integration area; iii) share small common projects and iv) discuss the implementation of classroom activities. In its first year, the community of practice was implemented exclusively in a virtual model (Virtual Community of Practicefirst year of implementation, it was decided that the community should continue in the school year 2021/22, extending its scope to new teachers. Thus, after the second year of implementation, it is necessary to analyse the work developed. To do so, we sought to understand the community members’ opinions about the work developed through a participatory action-research. Data were collected through direct observation and a questionnaire. The initial analysis already carried out reveals many positive aspects of the work developed, namely in terms of cooperation, doubt clarification, the exchange of experiences, asking questions without fear of making mistakes, among others.

1. Introduction

This primary school teachers’ (1st CEB) community of practice started its activity in the school year 2020/2021, as an integrated project of the ICT Competence Centre of the School of Education of the Polytechnic Institute of Setúbal (CCTIC-ESE/IPS), being organized around three main concerns: i) the idea that technologies appear beyond the curriculum and make it difficult to be accomplished; ii) teachers’ lack of experience in the pedagogical use of digital technologies (DT) and iii) the difficulties that teachers face when working with digital technologies (DT) in their classroom, a consequence of the lack of experience in the use of DT with students.

In order to answer these questions, it had as main goals: i) implement a small community of practice with 1st CEB teachers, focusing on issues related to the curricular integration of DT; ii) create lesson plans and other materials for the 1st CEB, where DT assume its role of cross curricular integration area; iii) share small common projects and iv) discuss the implementation of classroom activities (what went well and what can be improved).

In its first year, the community of practice was implemented exclusively in a virtual model (Virtual Community of Practice – VCoP), where teachers from different geographical points of the country met to discuss ideas and reflect on their teaching and learning processes, using Digital Technologies. Ten synchronous sessions were organized throughout the school year. In some of these sessions, reflections were held on different subjects: the goals of a community of practice; the role of DT in schools; teaching and assessment methodologies with DT and use and exploitation of the Milage + Learning Platform. In these sessions, the VCoP welcomed guest speakers from outside the community, such as expert teachers in different topics, students and parents. In the remaining five work sessions, the Community was dedicated to the joint production of activities using DT, through a planning model previously discussed, for the 1st CEB.

For the development and testing of the activities, the community members were organised into working groups according to the school years in which they taught. In these groups, teachers designed tasks and implemented them in their classrooms, reflecting afterwards, in small and large groups, on the successes and difficulties experienced in applying them and, when necessary, they were adjusted and changed to better meet the objectives that had been set.

In addition to these 10 sessions, the working groups met, whenever necessary, to reflect on the work done, to exchange ideas on methodologies to be used, to carry out the evaluation of the activities, whenever they felt the need to do so. Some documents and materials were produced at the VCoP which were organised and made available in two online spaces: http://projectos.ese.ips.pt/cctic/?p=4742 and http://projectos.ese.ips.pt/cctic/?p=4881.

After this first year of implementation and after the evaluation of all the work developed, it was decided that the community should continue in the school year 2021/22, extending its scope to teachers that belong to the area of influence of the ICT Competence Centre of the University of Aveiro (CCTIC/UA).

As in the previous year, the VCoP was proposed (and accredited) to the Scientific-Pedagogical Council for Continuous Training, as a Study Circle modality. During the academic year 2021/22, the community was attended by most of the teachers who had participated in the 1st year, plus 7 teachers who joined for the first time, in a total of 14. For training purposes, four of the VCoP members took the role of trainers, being part of the core group (Wenger et al., Citation2002) and most active in the Community, while the remaining 14 took the role of trainees.

During the school year, 10 working sessions were developed, discussing issues that considered the interests and needs of the teachers involved (project work and DT; the new Mathematics Essential Learning Outcomes; construction of opinion articles about the pedagogical integration of DT, with concrete examples of work to be carried out in the classroom), including, for the first time, a face-to-face meeting (a visit to Escola da Ponte, a school with a different approach in its organisation and learning methodologies). Different materials were also produced and made available in a specific space, specifically produced this year for the community https://projetos.ese.ips.pt/cpraticapeb/.

Thus, after the second year of implementation, it is necessary to understand how the work was developed, the strongest points and the ones that need to be improved, regarding the work that must be carried out in the 2022/23 school year.

With this article, we intend to analyse the perceptions and opinions of the teachers involved in the community about the work developed and how it may have contributed to their personal and professional development. On the other hand, using the DigCompEdu (European Framework of Digital Competence for Educators) as a reference, we will try to understand whether the work carried out in the community has helped in the development of digital competences of its members.

We will present a theoretical framework, followed by a description of the methodology adopted for the research carried out, some results obtained and, finally, some conclusions considering the analysed subject.

2. Theoretical framework

Communities of Practice (CoP) are not something new and they are everywhere. According to (Wenger, Citation1998), we are part of some throughout our lives, having, in some cases, a more effective participation and, in others, a more peripheral participation.

However, in recent times, there has been a large increase in the number of CoP, since, on one hand, they are composed of people who share the same interest or passion, who voluntarily interact regularly, exchange information and knowledge and share learning. On the other hand, there has been a significant increase in the use of digital technologies, allowing new forms of interaction (synchronous and asynchronous) and the possibility of more frequent interactions without additional costs, also reducing geographical barriers.

When analysing the CoP potential, we clearly see that the benefits in terms of education, as argued by (Wenger et al., Citation2002), are clearly greater than the difficulties that may be found: i) the group shares a common passion or interest and this is the area of knowledge around which the community is built; ii) the community is built on the basis of the relationships that are established, the interactions that lead to joint learning and the information sharing; iii) the members develop their own skills, based on the practices that are shared. In this sense, practice is seen as the challenge that unites and mobilises the community members, creating a basis for action, communication, problem-solving, performance and responsibility. These shared practices may involve different types of knowledge: cases and stories, theories, rules, models, principles, tools, experts, articles, lessons learned and best practices.

Thus, there is a great space within CoP for learning and that should, according to (Brown et al., Citation2018), be ruled by five fundamental points, very closely linked to the error issue: i) do not to be afraid of making mistakes and to learn from those mistakes; ii) mistakes should be analysed and understood; iii) we have to understand how those mistakes influence the results; iv) mistakes should not lead to the creation of resistance by the members but should be understood as part of the process and v) the help of external experts can be requested to help in different situations.

Also, according to (Brown et al., Citation2018), teachers involved in CoP should work together and not as isolated teachers, they should meet regularly, the community should have a shared leadership, collaboration among members and group work, leading to the construction of new common ideas that effectively improve students’ learning.

However, for these spaces to effectively “improve the conditions for professional practice through sharing, mutual support and collaborative learning processes” (Meirinhos, Citation2006) (p.135), it is necessary that teachers develop some digital skills that allow them to master synchronous or asynchronous communication tools, discussing and analysing possible solutions within the CoP. In addition, it is essential that they also think about how they can use DT in teaching and learning processes (Lucas & Moreira, Citation2018).

We live in a digital world, in which technology has been transforming the way we relate, work, learn and communicate with others. So, CoP can assume an even more important role as it opens new spaces that allow the creation of a propitious environment for knowledge construction, application and problem solving (Dias, Citation2008).

Thus, based on the potential available to us today, Virtual Communities of Practice (VCoP) integrate people who organise themselves, as in a CoP, but the difference lies in the fact that they use a communication system that does not require physical presence, eliminating some difficulties regarding the geographical location of its members, and can even unite people in different parts of the world.

As such, “this absence of the face-to-face factor changes practices and behaviours and promotes more autonomous and free contexts for the participation of each individual, because it does not regulate a determined time and space for action”. (Pinto, Citation2009).

In short, VCoP present themselves as an alternative to be explored for the construction of these competencies, since they are also formed by people who are committed to learning a specific field of knowledge. They are professionals who discuss practices, share experiences and seek solutions to common problems.

For this to become a reality in short term, we have, in Portugal, a teacher training plan, integrated within the scope of the Digital Transition Action Plan (Ministers’ Council Resolution no. 30/2020, April, 21) (de Ministros, Citation2020), which leads teachers to reflect on the digital’s pedagogical potential, developing in them “the skills necessary to fully exploit the potential of digital technologies to enhance teaching and learning and adequately prepare learners to live and work in a digital society”. (Meirinhos, Citation2006) (p. 12)

On the other hand, within the scope of the Digital Development Action Plan for schools, integrated in the Digitalisation Programme for Schools (Ministers’ Council Resolution no. 30/2020, April, 21) (de Ministros, Citation2020), it is notable the importance given to the involvement of teachers in communities of practice supported by cooperative and interdisciplinary work, stimulating reflection, sharing and critical digital use in an educational context.

Thus, the issue of teachers’ involvement in communities of practice, leading, on the one hand, to the development of professional skills and, on the other hand, to the development of digital skills, assumes a critical role in today’s society and it should lead to the implementation of activities with students, pedagogically supported by digital technologies.

3. Methodology

Since one of the authors of this article is an active member of this community, this study is a participatory action research (Borda, Citation2001), since it is not only an observation, but also an active participation.

Thus, according to (Coutinho et al., Citation2009), we positioned ourselves within a critical or emancipatory action-research framework since we seek to implement solutions that promote action improvement, in a social collaboration environment, leading to change.

In this research, we followed a mixed paradigm (quantitative and qualitative), with data collected from direct observation and through a questionnaire survey with close and open-ended questions (Coutinho, Citation2014).

To implement the questionnaire, we used Google Forms, since it allowed us to collect the respondents’ answers, whether they were close-ended answers, for later treatment and analysis of a quantitative nature, or answers to open-ended questions, which will have a qualitative and interpretative analysis.

The questionnaire was divided into five parts: Characterization of the elements of the community; Community participation; Community evolution; Participation of the trainers (resident trainers and guest trainers) and goal achievement. It was applied between the penultimate and last training sessions, in June 2022, to present some data in the final session (July 2022) and to organize the work to be carried out during the 2022/23 academic year.

14 responses were obtained, corresponding to all of the teachers of the 1st CEB, who participated in the Community (all the elements of the VCoP, except the four trainers of the Study Circle).

4. Data analysis

4.1. Questionnaire analysis

The closed-ended questions in the questionnaire consisted of statements that the teachers had to rate on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 corresponding to “I completely disagree” and 5 to “I completely agree”. There were also three open-ended questions, which aimed at identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the community and receiving suggestions for the work to be carried out in the school year 2022/23, if the teachers wanted to continue to belong to the Community.

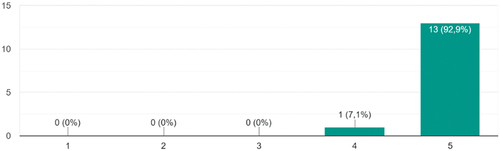

Regarding the Community Participation and considering the statement “Participation has enriched my professional life”, 1 teacher rated it with 4 (7.1%) and 13 rated it with 5 (92.9%), as presented in . This idea is also shared by several trainees, in their critical reflection reports, when they state that “It allowed students to work contents under a totally innovative approach and on the other hand, to develop new skills”. (critical report, trainee A); “This sharing within the community gave me a knowledge of strategies to conduct the activities aiming the greatest growth in students’ learning”. (critical report, trainee B) or even:

“This training was the driving force behind some changes in my work. I would like to highlight the project methodology, suggested and presented by teacher Rui Lima in one of the sessions, and some of the proposals for work plans presented during the visit to Escola da Ponte”. (critical report, trainee C).

About the statement “I learned with the community”, 1 teacher gave a score of 4 (7.1%) and 13 gave a score of 5 (92.9%), indicating that all the participants in the community learned from the experience and that the vast majority even considers that this learning was significant. This idea is also shared by several trainees in their critical reflection reports, when they state that their participation in the community allowed them to understand how they could promote “learning situations that allow students to engage in projects, solve problems and take ownership of digital environments and tools in a healthy and responsible way” (critical report, trainee D); allowed “the contact with different methodologies and approaches to activities planned in working groups, and proposed by the peers/colleagues, while giving place and time for ‘in loco’ experimentation of the same activities” (critical report, trainee E) or that it facilitated the conduct of “research and team planning, diversifying educational practice for the knowledge of new resources and applications and contact with new alternative educational methodologies”. (critical report, trainee F).

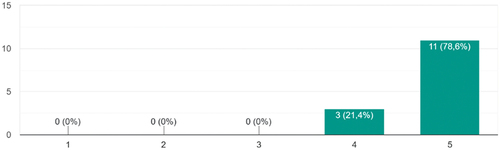

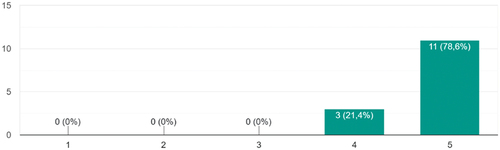

Regarding the statement “The exchange of information increased over time”, all the teachers responded 4 (21.4%) and 5 (78.6%), i.e., “agree” and “completely agree”. About the statement “Confidence between participants has increased over time.”, the 14 teachers indicated to agree (14.3%) and completely agree (85.7%). Finally, regarding the statement “The community has become closer over time”, we can verify, through , that 78.6% of community members assigned the rating 5.

All these issues related to the relationships that were established and the cohesion that existed between the community members were also shared by some trainees in their critical reflection reports, when they state that “The colleagues’ support in the design and critical reflection about the learning scenarios has been the greatest asset of this Learning Circle”; (critical report, trainee A); ”(…) this Study Circle allowed a digital empowerment of teachers with an horizontal model, i.e., among colleagues, motivating for the change of pedagogical practices (…)” (critical report, trainee G); “In the community we all shared knowledge, exchanged experiences, brought our problems and tried, together, to find solutions. In this sense, mutual help, friendship and trust arise in a spontaneous way”. (critical report, trainee H) or even:

“During this year, I have developed some programming activities in the classroom, tangible and visual, through the support of colleagues with more experience from the community. Thus, I felt supported to experiment new methodologies in the classroom, overcoming difficulties through collaborative and cooperative work.” (critical report, trainee I).

Regarding the goal achievement, the results were also quite encouraging. In regard to “Knowledge sharing helped me to develop new ideas”, we can see in that the 14 teachers rated it between 4 and 5.

This aspect was also quite visible in the synchronous sessions where, after many reflections in large group, with the existence of different ideas, the teachers, in small groups, tried to create activities where some of the ideas that had been discussed were included. In the critical reflection reports we can find some references to this issue when it is mentioned that:

“This type of collective learning, in which everyone is allowed to speak, to ask questions and have their doubts and anxieties heard, in which there is sharing of materials and ideas and in which we all practice what we learn in our schools, facilitates the emergence of new ideas, resources and educational paths, sometimes alternative ones, since the school environments in which each of us work is different. And it was in this sharing, so often in an informal way, that we were all able to learn”. (critical report, trainee J).

About the statement “I improved the quality of my work”, 2 teachers (14.3%) assigned level 4 and 12 teachers (85.7%) assigned level 5. In the teachers’ critical reflection reports, we also find some data about this topic, when they state that ”(…) the knowledge exchange about digital tools and resources allows professional growth among peers and a willingness to experiment new scenarios in the classroom. (critical report, trainee C); ”(…) through sharing and experience exchange, my practice was greatly enriched and allowed me to change some teaching strategies”. (critical report, trainee E) or even:

“By belonging to this community of practice, I felt that I was personally and professionally enriched, and sought to improve my practices by taking the community’s teachings into the classroom, not only by the use of digital resources presented in the sessions, but also the apprenticeship that was ‘born’ from the formal and informal moments between all the teachers who belong to the community”. (critical report, trainee D).

Regarding the last question, which refers to the closed-ended questions, “Please mark your agreement with the following statements”, it should be noted that, on the one hand, 93% of the members rated the statement “The presentation of the work by the different groups was an important moment of sharing and met my expectations”. On the other hand, the statement “I had the same opportunities to participate as all the members” was rated 5 by all the teachers, which indicates that all were integrated and felt that their contributions were heard and considered by the other members of the Community.

We highlight the fact that all teachers stated that they would like to continue working within the Community in the next school year.

Finally, we analysed the open answers. With regard to the strengths of the Community, the following were mentioned: i) sincere sharing by all and the willingness to help the others (9 teachers); ii) cooperation (3 teachers); iii) learning without fear of making mistakes, where we do not feel judged and feel at ease to question and share our anxieties and failures (3 teachers); iv) sessions with guest trainers (2 teachers); v) increased knowledge (4 teachers); vi) professional development (4 teachers) and vii) the opportunity to listen to and meet interesting people in the education area (1 teacher).

Regarding the points for improvement, teachers mentioned: i) the construction of more activities; ii) exploration of more digital tools; iii) the existence of a space called “What I do with…”, where participants can demonstrate the use of a particular DT, or website, for a greater exchange of knowledge; iv) the duration of the sessions and v) the existence of more face-to-face sessions.

4.2. Document analysis

Throughout the sessions, several documents were made available, discussed and built and were placed in the specific community space (https://projetos.ese.ips.pt/cpraticapeb/). Among these documents, we highlight, in the first place, the plans and resources built by the different groups that were tested, in the different classes of the elements that constituted those groups (https://projetos.ese.ips.pt/cpraticapeb/index.php/recursos/recursos-da-comunidade/).

There were also situations in which teachers of other groups, from different school years, seeing the potentiality of what the other elements had built, adapted this work and applied it in their classes, giving feedback afterwards to the group that had created them. Secondly, we highlight the space “Shares and Opinions”, which resulted from the reflections of the different community members on the pedagogical use of the DT, with concrete examples of activities that enhance this use, in a curricular integration perspective.

Each trainee also wrote a final critical reflection report on how the sessions had been developed throughout the year. In these reflections, we found elements that were very useful for the evaluation of the work carried out, but also in the preparation of the work to be carried out in the 2022/23 school year. Thus, in addition to the opinions that we have provided throughout this article, we would like to highlight two others about the work done within the Community:

“This Study Circle undoubtedly helped to break the fear of using digital tools in the classroom. By exploring and applying them in collaborative work, I felt more confident and I found out that students were undoubtedly more motivated and interested and even more predisposed to learn and carry out research on subjects/themes covered in class.” (critical report, trainee L) and

“Regarding colleagues, I started to come up with “ideas” and talk about them with enthusiasm, having managed, at least, to get people talking about technologies, projects and collaboration which, in the 1st CEB, with an ageing teaching staff, often fall into the category of “it’s too much work and messy”. Some colleagues started asking me to share what we were doing in the community after the sessions and visits. (critical report, trainee B).

5. Conclusions

Over these two years of existence, the Community of Practice for Primary School Teachers has been taking small steps, considering the goals it has set. Data indicate we have managed to create an informal, collaborative environment between all its elements, conducive to experimentation, reflection and knowledge sharing, always with the underlying idea that each one contributed with what they know, without questions or criticism of individual ideas and beliefs.

Despite this respect for the individuality of each teacher, there is some evidence that we have been building a common project, where everyone is involved in the activities that arise and where small experiences are shared. Thus, according to (Wenger, Citation1998), the community becomes involved in the practices of its members and the sharing of ideas and discussions on certain themes is reflected in the practice of each of them.

When evaluating all the work done, we can say that all the sessions of the Community, with or without external guests, contributed to the construction of new knowledge and new ideas that were implemented in the classroom, discussed in small and large groups and changed whenever necessary, leading to a change in teaching practices.

The members discovered digital tools/resources, making them all capable of innovating, taking into account the different educational realities, and these practices supported by the VCoP contributed to their professional development.

It also seems to us that, in addition to professional development, the teachers also developed some digital skills. In fact, throughout the sessions different ways to pedagogically integrate certain tools were addressed and they also became aware of them, feeling more confident in their use. One of the activities that took place in one of the sessions was the explanation, by one of the members, of how an interactive simulator could be used to study the greenhouse effect (activity built by the 3rd and 4th year group, called “Caring for what is ours”), which had never been done by some of the members. So, everyone had the chance to see how it could be used with the students, also developing some navigation, search and use skills.

This idea that the curricular integration of DT can occur if teachers have the skills and knowledge of how to use technology in their teaching and learning process (Baylor & Ritchie, Citation2002) is fundamental to change their practices and to develop their own digital skills, which allow them to focus not only on the development of technical skills but also on classroom practices.

Thus, we state our conviction that the participation in communities of practice supports teachers, contributing to making them more aware of the work they have to do with their students and to making them feel supported by their peers, so that they can continue to evolve and reflect on their pedagogical practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Baylor, A. L., & Ritchie, D. (2002). What factors facilitate teacher skill, teacher morale, and perceived student learning in technology-using classroooms? Computers & Education, 39(4), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1315(02)00075-1

- Borda, O. F. (2001). Participatory (action) research in social theory: Origins and challenges. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research (pp. 27–37). Sage Publications.

- Brown, B. D., Horn, R. S., & King, G. (2018). The effective implementation of professional learning communities. Alabama Journal of Educational Leadership, 5, 53–59. https://www.icpel.org/uploads/1/5/6/2/15622000/ajel_volume_5_2018.pdf

- Coutinho, C. P. (2014). Metodologia de Investigação em Ciências Sociais e Humanas: Teoria e Prática. Almedina.

- Coutinho, C. P., Sousa, A., Dias, A., Bessa, F., Ferreira, M. J. R. C., & Vieira, S. R. (2009). Investigação-acção: Metodologia preferencial nas práticas educativas. Revista Psicologia, Educação e Cultura, XIII(2), 355–379.

- de Ministros, C. (2020). Resolução do Conselho de Ministros 31/2020 (Cria a Estrutura de Missão Portugal Digital).

- Dias, P. (2008). Da e-moderação à mediação colaborativa nas comunidades de aprendizagem. Educação, Formação & Tecnologias, 1(1), 4–10.

- Lucas, M., & Moreira, A. (2018). DigCompEdu: quadro europeu de competência digital para educadores. Universidade de Aveiro.

- Meirinhos, M. (2006). Desenvolvimento profissional docente em ambientes colaborativos de aprendizagem à distância: Estudo de caso no âmbito da formação contínua Tese de Doutoramento, Universidade do Minho. https://bibliotecadigital.ipb.pt/bitstream/10198/257/1/TESE_D_Meirinhos_D.pdf

- Pinto, M. (2009). Processos de colaboração e liderança em comunidades de prática online: o caso da @rcaComum, uma comunidade ibero-americana de profissionais de educação de infância. Tese de Doutoramento, Universidade do Minho. http://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/bitstream/1822/12571/4/Tese_Doutoramento_20-18-02-09.pdf

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E., McDermott, R. A., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard Business School Press.