ABSTRACT

Designing learning solutions in digitally mediated contexts requires attention to the level of immersion, interactivity, personalization, and engagement promoted, to which the incorporation of active learning methods and gamified strategies can be strategic. However, more research is needed on how teachers use technology-enhanced active learning strategies and on the impact of game-design elements inclusion in learning environments. This study provides findings from the informed exploration stage of a project, consisting of the development and assessment of a digital platform to be used in Portuguese basic and secondary schools to support participation in extracurricular projects and promote its users’ sense of belonging. A survey by questionnaire was publicly shared with Portuguese schoolteachers, in June 2022, to map the current technological reality in Portuguese schools and teachers’ relationship with technologies. 215 valid responses were analysed with descriptive statistics and content analysis. The use of digital technologies was found not to have decreased after the emergency remote learning period. Teachers assumed that the most used platforms coincided with those institutionally supported and that combining the promotion of active learning methods and the formal recognition of learners’ attitudes and skills in a digital solution was something innovative and required in Portuguese schools.

1. Introduction

Learning and collaborative technologies, particularly when enhanced by gamification strategies, provide teachers with optimal conditions for the deployment of active learning practices, and the promotion of more authentic, meaningful, and memorable learning experiences (OECD, Citation2021). Simultaneously, they can improve such experiences by enabling self-directed, ubiquitous learning (Chayko, Citation2014), and connectedness (Ito et al., Citation2013), providing teachers and learners with opportunities to share ideas, collaborate with each other, and to create and enroll in communities of practice (Sharples, Citation2016), which is in line with the promotion of key 21st century competencies (Binkley et al., Citation2012). However, according to the literature, more empirical evidence of teachers’ experience while using technology-enhanced active learning strategies (Sitthiworachart et al., Citation2022) is needed, as well as of the effectiveness of game-design elements in learning environments, and of their impact on how people learn in gamified contexts (Cavalcante-Pimentel et al., Citation2022).

Within the scope of design-based research (Bannan, Citation2013), this study provides findings from the informed exploration stage of a project, related to the design of a digital learning platform to be used in Portuguese basic and secondary education with the purpose of strengthening its users’ sense of belonging to the corresponding educational community by means of supporting the implementation of extracurricular projects, developed at school, stimulating participation in those projects and recognizing it based on a reward system incorporated in the gamified strategies of the platform (e.g., including storytelling and game-based elements such as digital badges). A digital survey by questionnaire, targeted at Portuguese basic and secondary school teachers, was publicly shared in June 2022, and a total of 215 valid responses was selected, with the purpose of gathering teachers’ perceptions of the current technological reality of Portuguese basic and secondary schools and of their relationship with digital technologies, in order that the following research question could be clarified: What do schools consider essential, so that they are willing to integrate another digital platform in their practices?

2. Designing learning solutions in digitally mediated contexts based on participatory practices

2.1. The role of learning and collaborative technologies

The potential of digital technologies to empower learning experiences is highlighted in the literature (Chayko, Citation2014; Sitthiworachart et al., Citation2022), among other things, for triggering learners’ creativity (Cochrane & Antonczak, Citation2014), and critical thinking (Harju et al., Citation2019), for promoting higher visibility of teachers and learners’ work, the development of higher cognitive processes as well as learner engagement and motivation (Narayan et al., Citation2018).

At the same time, different authors converge on the assumption that mobile learning and digital technologies facilitate new forms of interaction and social learning (Aguayo et al., Citation2017; Cochrane & Antonczak, Citation2014), also contributing to pedagogical changes, associated with a new relationship with knowledge (Ehlers, Citation2020), ontological shifts that require the adoption of innovative learning strategies and a reorganization of learning spaces (Cochrane & Antonczak, Citation2014). Such findings are also in line with those reporting the influence of digital technologies on teaching and learning outcomes (Lai & Bower, Citation2019), and on handling major educational challenges associated with traditional instruction, namely student disengagement and lack of motivation (Dicheva et al., Citation2015).

2.2. The creation of smart learning environments

Active learning methods have attracted growing interest from academia and education stakeholders (Sitthiworachart et al., Citation2022), for their potential to place learners at the heart of the learning process, and for the development of a competency-based approach to learning, including problem-solving (OECD, Citation2021), and the use of higher cognitive skills (Hwang et al., Citation2019), particularly responsible for favouring deep learning (Deterding et al., Citation2011). Game-based learning is referred to as an active learning strategy and technology (Sitthiworachart et al., Citation2022), also connected with the inclusion of game-design elements, responsible for making “non- game products and services more enjoyable and engaging” [17, p. 10], and with the concept of gamification, defined by (Deterding et al., Citation2011) as the use of game design elements in non-game contexts. The interest in using gamification in educational settings has grown over time (Dicheva et al., Citation2015), due to the potential of educational games to provide engaging learning experiences, to promote the development of key competencies like problem-solving, collaboration, and communication, and to motivate learners by means of mechanisms that may include rewards, but mostly explore “the joy of playing and possibility to win” [15, p. 1].

Agbo et al. (Citation2021, p. 5816) point out that a smart learning environment “provides a high level of immersion, interactivity, personalization, and engagement to adapt to learners’ needs and provide intelligent feedback based on learners’ characteristics and learning progress”. Digital learning platforms, especially if enhanced by gamification strategies, may be an example of smart learning environments. However, empirical evidence of the effectiveness of game elements inclusion in learning environments is still scarce (Dicheva et al., Citation2015), and more research is needed as for deeply understanding how people learn in gamified environments, when it occurs, and what conditions are required so that effective learning may result from it (Cavalcante-Pimentel et al., Citation2022). Simultaneously, the lack of studies providing evidence of teachers’ experience while using technology-enhanced active learning strategies (Sitthiworachart et al., Citation2022) is clear in the literature, as well as the challenges faced by instructors as to coping with the rapid evolution of digital tools (Ylirisku et al., Citation2021), and to integrating such resources in their teaching practice in an innovative way (Sitthiworachart et al., Citation2022). Besides that, Dicheva et al. [15, p. 10] also point out “the lack of technological support” as one of the major barriers to the integration of game elements in education and highlight the importance of software tools’ development as for a more effective support of gamification in as many educational contexts as possible.

Although technological resources are fundamental tools as to promoting connectedness (Ito et al., Citation2013), (Erstad et al., Citation2021) highlight that it is not so much about the technology used, but about the way schools open up and place their focus on the practices that may actually encourage teachers and learners to interact and engage in innovative ways. The creation of communities of practice is one of the scopes within which digital technologies may have a distinguishing role (Sharples, Citation2016), for the facilitation of digital connectedness and transformative relational agency, associated with the awareness that the success of teamwork results from each member’s contribution (Bender & Peppler, Citation2019), and the corresponding impact on teachers and learners’ sense of belonging (Erstad et al., Citation2021), among other things, by means of projects that apply innovative teaching and learning strategies, and promote real-world problem-solving and collaborative work.

3. Methods

3.1. Methodological approach and purpose of the study

Within the scope of design-based research and following the integrative learning design framework (ILDF) (Bannan, Citation2013), this study provides findings from the informed exploration stage of a project, related to the development of a digital learning platform to be used in basic and secondary education. The purpose of this digital tool is to strengthen its users’ sense of belonging to the corresponding educational community and support the implementation of extracurricular projects, developed at school, by means of stimulating participation in those projects and recognizing it, based on the use of gamification strategies, including storytelling and a game-based reward system involving tangible and digital rewards (e.g., badges, experience points, and internal rankings).

The informed exploration stage was mostly centred on needs analysis based on identifying research gaps and gathering insights into the current technological reality of Portuguese basic and secondary schools and into teachers’ relationship with digital technologies, so that the following research question could be clarified: What do schools consider essential, so that they are willing to integrate another digital platform in their practices?

The informed exploration stage precedes the enactment stage of the project, which will consist of the development design process of the platform by means of co-design and participatory strategies involving end-users (teachers and learners) from Portuguese basic and secondary schools.

3.2. Study sample and data collection

Considering the lack of studies focusing on teachers’ experience while using technologies to support active learning (Sitthiworachart et al., Citation2022), and on Rienties et al.’s (Citation2016, p. 4) assumption, based on the Technology Acceptance Model, that the intention to use digital technologies is mostly influenced by its users “perceived usefulness” and “perceived ease of use”, it was considered relevant to gather data on basic and secondary teachers’ perceptions of the matters in focus.

A digital survey by questionnaire was publicly shared and targeted at Portuguese basic and secondary school teachers, also with the support of different Teachers Associations. As exclusion criteria, it was determined that teachers who were not currently assuming teaching functions in a basic and secondary school or who did not do it over the preceding two school years could not integrate the study sample. All basic and secondary school levels and possible subject areas taught by the teachers were considered.

Data collection happened in June 2022. 244 teachers answered the survey and a total of 215 valid responses were finally selected.

3.3. The data collection tool and data analysis

The data collection tool used was created with the aim of gathering basic and secondary school teachers’ perceptions of their experience using digital platforms for educational purposes, and identifying strengths and weaknesses of the educational system, so that the insights collected could provide as much information as possible for the development of a digital solution that would be an innovative, practical, and useful tool to facilitate teaching and learning.

The online survey included four sections: i) basic information on the teacher’s profile (including age, subjects and school levels taught); ii) current technological reality at basic and secondary schools (as for institutionally supported digital resources, digital tools used in the emergency remote learning period and after it); iii) purpose for using digital technologies; and iv) relationship with digital technologies (as to understanding what teachers’ perspectives were on the future evolution of their technological reality at school, based on their experiences using these tools).

The data analysis techniques used were descriptive statistics in the case of the data from closed-ended questions, and content analyses, in the case of open-ended questions.

4. Results

4.1. Teachers’ profiles

As for the teachers’ age, 50,2% of the inquired participants were aged between 45 and 54 years old, followed by 33,5%, aged above 55. The least representative groups were those of the teachers aged between 35 and 44 (12,6%), and below 35 years old (3,7%).

Regarding the levels taught by the teachers, it is important to mention that in most cases they worked with more than one school level. Most teachers worked in lower secondary (78%) and in upper secondary education (42%). Within the scope of elementary education, a smaller percentage worked in primary school (19,5%) and in preschool (4%). The predominant subject areas among the sample related to elementary education, as well as English as a foreign language (EFL), Portuguese, Mathematics, Biology and Geology.

4.2. Current technological reality at basic and secondary schools

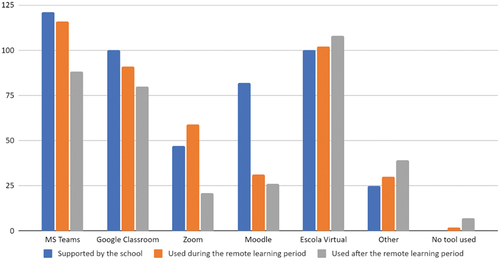

The panorama of the use of digital platforms in Portuguese basic and secondary schools is shown in , regarding the following aspects, based on the teachers’ perceptions: i) digital tools supported by the teacher’s institution; and ii) the tools the teacher used more frequently during and after the emergency remote learning period.

Figure 1. Teachers’ use of digital platforms in their basic and secondary schools during and after the emergency remote learning period.

According to the data depicted in , the digital platforms reported by most teachers for being institutionally supported were MS Teams (N = 121), Escola Virtual (N = 100), and Google Classroom (N = 100). The same three platforms stood out during and after the remote learning period. MS Teams was the one stated by most teachers (N = 116) for being used during the COVID-19 pandemic period, but the option for Escola Virtual was more noticeable after it (N = 108). This digital platform, developed by a Portuguese publishing company, releases teaching and learning resources aimed at basic and secondary education either related to the e-version of multi-subject schoolbooks or to complementary resources. The choice of Escola Virtual was the most consistent over time, also showing a growing tendency.

As for the use during and after the remote learning period, MS Teams and Google Classroom were progressively chosen by less teachers. Although Moodle was the fourth in the ranking of the digitally supported platforms (N = 82), the option for it during and after the remote learning period was considerably low, compared to the rest of the sample. Overall, lesser prominence was given to Zoom platform, especially as for institutional support and use after the remote learning period.

4.3. Purpose for using digital technologies

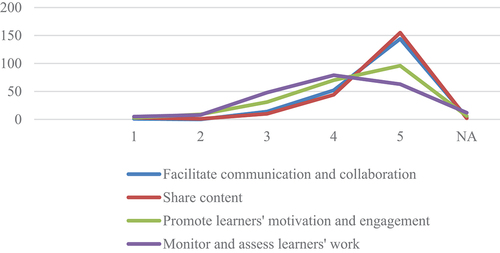

Regarding the purpose for using digital tools at school, teachers were asked to assess the importance given to four possible reasons, using a scale ranging from 1 (less important) to 5 (the most important). provides the distribution of teachers’ answers as for that matter.

Figure 2. Reasons for using digital technologies based on the level of importance given by the teachers.

Based on the input depicted in , the reasons selected by most teachers for using digital tools, and also considered the most important, were sharing content (N = 155, 72%), facilitating communication and collaboration (N = 144, 67%), and promoting learner motivation and engagement (N = 96, 45%). The reason chosen by a smaller number of teachers and, within that scope, associated by the most with scale attribute 4 (“important”) was to monitor and assess learners’ work (N = 79, 37%). Teachers could also add further reasons for using digital technologies and the creation of digital resources, adapted to learners’ profiles and needs, was the one that stood out.

4.4. Relationship with digital technologies

In order to assess teachers’ relationship with digital technologies, the data gathered reported their openness to introducing a new digital platform in the school dynamics, a reflection on the level of pedagogical and digital innovativeness of the platforms they used as well as their perspectives on what to do and challenges to overcome.

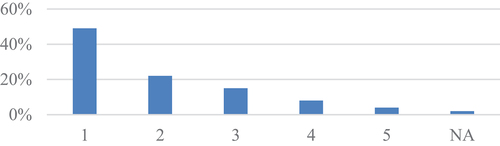

As for teachers’ openness to introducing a new digital platform in the school dynamics, they were asked to express their level of agreement with the following statement, by means of a scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree): “Introducing a new digital platform in the school dynamics would be unconceivable, even if it promoted learner motivation and engagement as well as the recognition of their skills and attitudes in an innovative way within the scope of participation in extracurricular activities”. Data related to teachers’ answers is presented in .

Figure 3. Teachers’ level of agreement with the statement reporting their possible lack of tolerance towards the inclusion of a new digital platform in school dynamics.

As stated in , the majority of the teachers disagreed with the idea that introducing a new digital platform in the school dynamics would be unconceivable (49%, N = 105) and a small number totally agreed with it (4%, N = 9). Based on that it may be assumed that most teachers welcomed the idea of introducing a new platform in the school dynamics if it included the features mentioned in the statement.

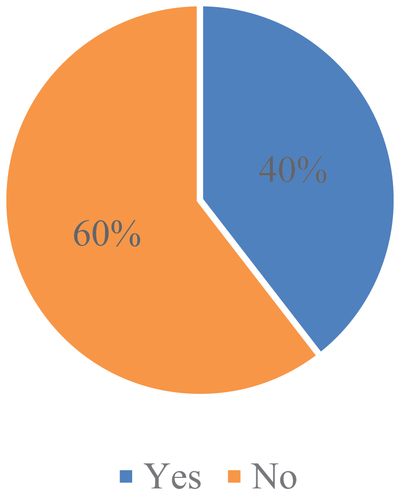

Regarding teachers’ reflection on the level of pedagogical and digital innovativeness of the platforms used, they were expected to acknowledge whether these tools included functionalities that promoted active learning methods and gamification strategies, as well as the recognition of learners’ skills and attitudes within the scope of participation in curricular and extracurricular activities. As shown in , 60% of the teachers stated that among the platforms they used, none included all the requirements mentioned, compared to 40% that considered the opposite.

Figure 4. Teachers’ perceptions of whether the platforms they used included functionalities that promoted active learning methods and gamification strategies as well as the recognition of learners’ skills and attitudes.

As for teachers’ perspectives on the future evolution of the technological reality at school, they first reflected on how the integration of such innovative tools (including active learning methods and gamification strategies as well as the recognition of learners’ skills and attitudes) could be encouraged. Then they focused on the challenges to be overcome, all over the integration process. Data resulting from content analysis of teachers’ perceptions as for both matters is depicted in .

Table 1. Codes resulting from content analysis of teachers’ perceptions of how to encourage the use of an innovative platform in schools.

Table 2. Codes resulting from content analysis of teachers’ perceptions of challenges to be overcome all over a digital platform integration process.

As shown in , the integration of a tool with the features mentioned before requires a strong marketing strategy aimed at motivating learners to use it and showing teachers the practicality and effectiveness of its functionalities, as well as the consideration for weaknesses in the use of digital technologies at school and the preparation of its end-users prior to its integration and regular practice in the teaching and learning activities.

Regarding teachers’ perceptions of the challenges to be overcome all over the integration of an innovative digital platform, and, as shown in , technical problems (e.g., Internet connectivity), lack of digital devices, the persistence of a bureaucratic educational system and inconsistencies in most teachers’ digital literacy may hinder such integration and should be carefully met, so that it can happen successfully at schools.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Considering the research question: What do schools consider essential, so that they are willing to integrate another digital platform in their practices?, and based on the study findings, it may be inferred that the inclusion of a new digital platform in the school dynamics is welcomed by basic and secondary school teachers and perceived as needed.

This is particularly clear, based on the evidence that despite the consistent use of digital tools before and after the emergency learning remote period, most teachers did not identify any platform, among those they used, that combined innovative features (related to the promotion of active learning methods and the integration of game-design elements) with the formal recognition of learners’ attitudes and skills. Complementary to that, sharing content and facilitating communication and collaboration were the reasons the teachers considered the most important for using digital technologies, which was only then followed by learner motivation and engagement. According to (Erstad et al., Citation2021), in order to have an impact on teachers and learners’ sense of belonging, technologies should support the implementation of projects that integrate innovative teaching and learning strategies and promote problem-solving and collaborative work, which after all might have an impact on their motivation and engagement levels.

Besides that, the willingness expressed by most teachers to integrate a new platform in their school dynamics was another relevant input of the study findings, together with insights like the importance of considering details of a digital tool like its ease of use, level of attractiveness and innovation, the facilitation of collaborative work (also between teachers with different levels of digital literacy), and the provision of training as well as of results on its effectiveness (based on its use in other schools). These facts are particularly significant, considering that most of the teachers in the sample belonged to the elder groups (between 45 and 54 years old and above 55), associated in the literature with usually having lower digital literacy levels (Lucas & Bem-Haja, Citation2021), and also taking into account these teachers’ perceptions of the challenges to be overcome as for an appropriate integration of digital tools at school, particularly the lack of teaching time for collaborative work, teachers’ tiredness of investing in projects that do not last long, and the lack/inadequate teacher training as for those matters. Such insights might be indicative of the willingness of the teaching workforce to welcome more innovative digital resources, as long as they facilitate teaching and learning practices, but also their awareness of the weaknesses of the system and difficulties involved in appropriately using and integrating these tools. These findings strengthen the relevance of studies like (Dicheva et al., Citation2015), according to which it is fundamental, on the one hand to provide schools and teachers appropriate technological support/training, so that digital game-based solutions can be properly integrated in educational settings, and, on the other hand consider the effectiveness and quality of software tools’ development.

Another insight of the study relates to the fact that the platforms reported as being used the most during and after the remote learning period were the same mentioned by most teachers for being institutionally supported (MS Teams, Escola Virtual, and Google Classroom). This fact may be indicative of the influence the decisions taken by the school board as for the adoption of digital tools (e.g., platforms) may have on teachers’ attitudes towards the use of these tools, and may be consistent with the position of authors who view the use of digital platforms for education purposes as highly bureaucratized and associated with a platform capitalism phenomenon (Lima, Citation2021), from which schools were not able to protect themselves (Afonso, Citation2021), promoting new ways of non-participation and a highly hierarchical use of such tools. A possible way of approaching such issues may be, according to (Erstad et al., Citation2021), placing the focus first on the pedagogical practices to be encouraged and on the resulting interactions between teachers and learners, and only then on choosing the digital resources that may facilitate teaching and learning within that scope. As highlighted by (Masterson, Citation2020), the integration of digital technologies is still a matter of concern in basic and secondary schools, for the strategies used (still related with teacher-centred approaches) and the inconsistencies found in teachers and learners’ digital literacy. Such facts can only be addressed, according to (Sancho-Gil et al., Citation2020) with a more critical and reflexive use of these tools and a different approach as for the integration of future Ed-tech initiatives.

Overall, study findings provide evidence that teachers recognize the potential of digital learning platforms to strengthen its users’ sense of belonging to their education community, and that they are willing to collaborate with the integration of a new tool if that matches the purpose of their schools.

Acknowledgments

The present study integrates Project Campus and is financially supported by Fundação Altice and by national funds through FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology, I. P., under the project UIDB/05460/2020, which is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Afonso, A. J. (2021). Novos caminhos para a sociologia: tecnologias em educação e accountability digital. Educação and Sociedade, 42, e250099. https://doi.org/10.1590/es.250099

- Agbo, F. J., Oyelere, S. S., Suhonen, J., & Laine, T. H. (2021). Co-design of mini games for learning computational thinking in an online environment. Education and Information Technologies, 26(5), 5815–5849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10515-1

- Aguayo, C., Cochrane, T., & Narayan, V. (2017). Key themes in mobile learning: Prospects for learner-generated learning through AR and VR. Austr J Educ Technol, 33(6), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3671

- Bannan, B. (2013). The integrative learning design framework: An illustrated example from the domain of instructional technology. In T. Plomp & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design research: an introduction (pp. 114–133). SLO - Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development.

- Bender, S., & Peppler, K. (2019). Connected learning ecologies as an emerging opportunity through Cosplay. Comunicar, 27(58), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.3916/C58-2019-03

- Binkley, M., Erstad, O., Herman, J., Raizen, S., Ripley, M., Miller-Ricci, M., & Rumble, M. (2012). Defining twenty-first century skills. In P. Griffin, B. McGraw, & E. Care (Eds.), Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills (pp. 17–66). Springer.

- Cavalcante-Pimentel, F. S., Morais-Marques, M., & Barbosa, V. (2022). Learning strategies through digital games in a university context. Comunicar, 30(73), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.3916/C73-2022-07

- Chayko, M. (2014). Techno-social life: The Internet, digital technology, and social connectedness. Sociology Compass, 8(7), 976–991. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12190

- Cochrane, T., & Antonczak, L. (2014). Implementing a mobile social media framework for designing creative pedagogies. Social Sciences, 3(3), 359–377. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3030359

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments (pp. 9–15). MindTrek.

- Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G., & Angelova, G. (2015). Gamification in education: A systematic mapping study. Educational Technology and Society, 18(3), 75–88.

- Ehlers, U. (2020). The future skills turn. In U. Ehlers (Ed.), Future skills - Future learning and future higher education (pp. 11–26). Springer. Book Series.

- Erstad, O., Miño, R., & Rivera-Vargas, P. (2021). Educational practices to transform and connect schools and communities. Comunicar, 29(66), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.3916/C66-2021-01

- Harju, V., Koskinen, A., & Pehkonen, L. (2019). An exploration of longitudinal studies of digital learning. Educational Research, 61(4), 388–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2019.1660586

- Hwang, G. J., Yin, C., & Chu, H. C. (2019). The era of flipped learning: Promoting active learning and higher order thinking with innovative flipped learning strategies and supporting systems. Interact Learn Environ, 27(8), 991–994. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1667150

- Ito, M., Gutiérrez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes, J., Salen, K., Shor, J., Sefton-Green, J., & Watkins, S. C. (2013). Connected learning: An agenda for research and design. Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

- Lai, J. W., & Bower, M. (2019). How is the use of technology in education evaluated? A systematic review. Computers & Education, 133, 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.010

- Lima, L. (2021). Máquinas de administrar a educação: dominação digital e burocracia aumentada. Educação and Sociedade, 42, e249276. https://doi.org/10.1590/es.249276

- Lucas, M., & Bem-Haja, P. (2021). Estudo sobre o nível de competências digitais dos docentes do ensino básico e secundário dos Agrupamentos de Escolas e das Escolas Não Agrupadas da rede pública de Portugal Continental. Ministério da Educação – Direção-Geral da Educação.

- Masterson, M. (2020). An exploration of the potential role of digital technologies for promoting learning in foreign language classrooms: Lessons for a pandemic. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15(14), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v15i14.13297

- Narayan, V., Herrington, J., & Cochrane, T. (2018). Designing for learning with mobile and social media tools – A pragmatic approach. Conference Proceedings of 35th International Conference of Innovation, Practice and Research in the use of Educational Technologies in Tertiary Education: Open Oceans: Learning Without Boarders (pp. 214–223). Geelong.

- OECD. (2021). 21st-century readers - Developing literacy skills in a digital world OECD. Retrieved July 1, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3jvZgmG

- Rienties, B., Giesbers, B., Lygo-Baker, S., Ma, H. W. S., & Rees, R. (2016). Why some teachers easily learn to use a new virtual learning environment: A technology acceptance perspective. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(3), 539–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2014.881394

- Sancho-Gil, J. M., Rivera-Vargas, P., & Miño-Puigcercós, R. (2020). Moving beyond the predictable failure of Ed-Tech initiatives. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1666873

- Sharples, M. (2016). Digital education: Pedagogy online. Nature, 540(7633), 340–340. https://doi.org/10.1038/540340a

- Sitthiworachart, J., Joy, M., King, E., Sinclair, J., & Foss, J. (2022). Technology-supported active learning in a flexible teaching space. Educational Sciences, 12(9), 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090634

- Ylirisku, S., Jang, G., & Sawhney, N. (2021, August 15–18). Re-thinking pedagogy and dis-embodied interaction for online learning and co-design. In E. Brandt, E. Markussen, T. Berglund, E. Julier & G. Linde (Eds.), Nordes 2021: Matters of Scale, Kolding, Denmark (pp. 4234–432). https://doi.org/10.21606/nordes.2021.48