ABSTRACT

The project “Academia Digital para Pais” began in a pandemic context, in an effort of the Ministry of Education and the private sector, aiming at helping the digital-struggling families. The COVID-19 pandemic led schools to a sudden closure, highlighting the challenges families faced, both in terms of access to technologies, and in terms of the digital skills needed to participate in a digitalized world. The objectives of the project were twofold: i) provide parents/tutors with digital skills to help their children, during remote teaching; ii) provide parents/tutors with digital skills crucial for integration in society. We intended to study the project, from design to implementation, using a quantitative approach, aimed at: identifying the parents/tutors’ self-perceptions of the digital competences developed; determining the participants’ perception of the level of attainment of the goals of the project; measuring the satisfaction of the parents/tutors involved in the project; and lastly exploring differences in the self-perceived digital competence according to their level of satisfaction. The results reveal high levels of satisfaction which, combined with the positive self-perception in the development of their digital competences, is a strong indicator of the potential of these initiatives in the empowerment of citizens, concurring to their social inclusion.

1. Digital academy for parents

1.1. The context

The pandemic context that began in Portugal at the beginning of 2020, and which led to a general confinement in March of that year, generated a disruption in education with the closure of all the schools. Thus, in Portugal, in a period of 48 hours, between 13th and 15th March, schools, teachers, students and families were forced to reorganize themselves to teach and learn at home, using digital technologies.

This sudden, and therefore unprepared, transition from face-to-face teaching to online teaching, although commonly referred to as Distance Education, resulted, due to the unpredictability of a pandemic, in a response that several authors refer to as Emergency Remote Teaching (Hodges et al., Citation2020). A similar scenario took place all over the world affecting more than one and a half billion children and young people in 188 countries, according to UNESCO data (Affouneh et al., Citation2020).

In fact, the situation led to different efforts to minimize the impacts of school closures. Thus, in civil society movements, or led by the public sector, several initiatives emerged, namely programs for the distribution of computer material to students, support groups between teachers on social networks, support sites with resources and guidelines for schools, television programs to keep students in touch with school content, especially for those who did not have the digital means to follow the online modality then imposed.

The need for answers was urgent, since the exceptional situation experienced, combined with the unpreparedness on the part of the different actors, led to unavoidable difficulties experienced by teachers, students, and families on a global scale (Schleicher, Citation2020).

It is in this context of great disruption of the natural teaching/learning process that, in September 2020, the “Digital Academy for Parents” Project was born, an initiative of the private sector, specifically of the EDP Distribuição, now E-REDES, in partnership with the Directorate-General for Education (DGE), and which had the collaboration of the ICT Competence Centre of the University of Aveiro.

The project is born from the realization of the difficulties felt by families in accompanying the educational process of their children during the period of Emergency Remote Teaching, then transposed to virtual learning platforms. Its fundamental objective was the training of parents/tutors of more disfavoured families in the use of systems and services mediated by the web.

The projects’ aims were defined by E-REDES and the DGE as follows:

- provide families with basic digital competences allowing them to accompany and help their children during emergency remote teaching,

- provide families with basic digital competences, considering these as tools that will increase the families’ inclusion in today’s society, and fighting socioeconomical asymmetries (E-REDES Homepage, Citation2021).

1.2. Promoting the digital competence of citizens – the European and the national context

The concern with the development of citizens’ digital skills has been deserving the attention of different policy makers since, at least, the beginning of the century. In 2006 the European Parliament and its Council, through a recommendation present in the European Framework of Reference, identified the digital competence as one of the eight key competences to be developed by all citizens.

This recommendation is assumed as crucial for Europe to be able to respond to financial globalization and the need for an effective transition to a knowledge-based economy (Lucas et al., Citation2017), recommending, therefore, the taking of actions for promoting these skills, in contexts of initial training for young people and training of adults.

Following this recommendation several initiatives have emerged, namely the European Digital Agenda, published in 2010. This document makes it clear, through the different actions included in it, that the “digital” is of enormous importance in the lives of all citizens. In fact, this document notes the need for actions aimed at “Improving digital literacy, qualifications in this field and inclusion in the digital society” (European Commission: Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Citation2010) (p. 28).

One of the most relevant initiatives that have emerged in Europe, linked to the development of digital competences, was the creation of the working group of the Joint Research Centre (JRC) – Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS) for the development of a common conceptual basis for political and educational decision-makers to develop programs focusing on digital competences with clear and shared indicators. This common conceptual basis aimed at improving the educational paths of young people and adults, professionally active citizens, the unemployed and future workers.

In 2012, in the analysis of different references presented by Ferrari, difficulties were found on the identification of a clear conceptualization of digital competence. As the author points out, even within the European Commission there are different conceptions and nouns being used, ranging from Digital Literacy, eLiteracy, e-Skills, eCompetence, among others. It is from this document that arises the conceptualization of Digital Competence, which is now considered consensual in the guiding documents and contained in the references produced by the European Commission: “Digital Competence is the set of knowledge, skills, attitudes (thus including abilities, strategies, values and awareness) that are required when using ICT and digital media to perform tasks; solve problems; communicate; manage information; collaborate, create and share content; and build knowledge effectively, efficiently, appropriately, critically, creatively, autonomously, flexibly, ethically, reflectively for work, leisure, participation, learning, socialising, consuming, and empowerment” (Ferrari, Citation2012 p. 45).

The effort to strengthen citizens’ digital competences remains a priority at European level as can be seen by the set of actions planned for 2021–2027 (European Commission: Digital Education Action Plan: Citation2020). Specifically with regards to the digital competences of citizens, concrete goals were defined in the Skills Agenda for Europe: “By 2025, 230 million adults should have at least basic digital competences, which corresponds to 70% of the adult population in the EU” (European Commission: European Skills Agenda for sustainable competitiveness, social fairness and resilience, Citation2020, p. 23).

In September 2021, the European Commission presented the program “Guide to the Digital Decade”, which “aims to ensure that the European Union achieves its objectives and goals towards a digital transformation of our society and our economy” (European Commission: Proposal for a Decision of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing the 2030 Policy Programme “Path to the Digital Decade”Brussels, Citation2021, p. 3).

The European Commission’s digital goals for 2030 aim to pave the way for the digital transformation of Europe, with defined goals for the digital transformation of companies, for the digitization of public services, for the creation of secure and sustainable digital infrastructures and for the development of citizens’ skills, pointing to 80% of the population with at least basic digital competences.

Portugal, as a member state of the European Union, is not a stranger to the European efforts, existing in our country, similarly to what has been portrayed, a strong commitment to the digital empowerment of citizens.

Focusing our analysis on the most recent initiatives, in the executive summary of the Action Plan for the Digital Transition of Portugal, presented in March 2020, it is mentioned that this plan “has as main areas of focus the digital empowerment of citizens, the transformation of companies and the digitization of the State” (Portugal Digital: Plano de Ação para a Transição Digital de Portugal, Citation2020, p. 3).

In a context of strong technological and digital development, the empowerment of citizens is notoriously fundamental – not only because more capable citizens are more effective parts on the societal engine, insofar as they contribute to it with all their knowledge, but also, because it is through training that the effort made towards digital inclusion is guaranteed. If we look at the objectives defined at European and national levels, which strongly focus on the growing digitization of companies and services, the lack of digital empowerment of people can entail risks of greater social exclusion.

1.3. Digital divide

The discussion about the digital divide of citizens is not new, it emerged in the 1990s, as the use of computers increased, and certain groups of citizens did not have access to them. Therefore, these citizens were not accompanying the development processes of the so-called digital revolution (Eastin et al., Citation2015; Scheerder et al., Citation2017).

In 2000 (van Dijk, Citation2000), presented four different forms of lack of access that can lead to digital exclusion:

Lack of experience in digital environments, due to lack of interest, and lack of propensity for technologies (psychological access);

Lack of access to computers/technological devices (material access);

Lack of digital skills, caused by inadequate training or absence of social support (access to skills);

Lack of significant use opportunities (access to use).

In the same article, the author highlighted the importance of studies shifting the focus from material access and starting to focus on other aspects, arguing for the underlying complexity of the digital divide.

In fact, at first, the issues of digital inclusion and exclusion were assumed in a simplistic and binary way – having access or not was the decision point; that is, they had a strong economic component, and separated those who had access to economic power from those who did not.

However, over the years, the definition has changed. If at first it was considered that access to technology would be sufficient to achieve digital inclusion, it quickly became clear that access, by itself, was not synonymous of the development of the digital skills that could result in an effective and beneficial use for citizens (Helsper et al., Citation2015). That is, given the evidence brought by the investigation, that equal access for all does not guarantee equal opportunities for all, the investigation sought to focus on the quality of use, going beyond the binary vision initially presented (Livingstone & Helsper, Citation2007).

In a European and national context where the commitment to the digitalization of society is growing, the issues of the digital divide must be part of social concerns. This is even considered when, in the Action Plan on the European Pillar of Social Rights (European Commission: The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan, Citation2021) it is stated that having basic digital skills is “a precondition for inclusion and participation in the labour market and in society in a digitally transformed Europe” (p. 7); therefore, all citizens should have access to technology and the skills that allow them to take advantage of it in order to be truly included citizens in today’s society.

In May 2021, the Portuguese Charter on Human Rights in the Digital Era was published, which enshrines to all citizens the right of access to the Internet, with the State being responsible for promoting measures that ensure access not only to technological resources, but also the necessary skills to take advantage of them.

The “Digital Academy for Parents” project arises in a pandemic context, which accentuated the need to develop citizens’ digital skills. However, as we could see from the described above, the relevance of the project is embodied in the context of the increasing digitalization of today’s society as it constitutes a means of combating the digital and, consequently, the social divide.

1.4. Digital academy for parents – implementation

The project “Digital Academy for Parents” was implemented in 48 adherent school clusters all over the country. The schools were responsible for designating a coordinator, select the volunteer trainers and manage the enrolment of the participants (10 to 20 participants per group). During its first year of implementation the project was specially directed to TEIPFootnote1 schools and to parents/tutors of children attending elementary levels of education (aged 6 to 11 years old), since they were perceived as the ones who struggled the most during the pandemic context.

The coordinator was responsible for the training of the volunteers, who in turn were responsible for the actual work with the participating parents/tutors.

The volunteers, primarily students from the schools, aged 14 or older, had training sessions with the coordinator, exploring all the material developed for the sessions. These materials, organized in a KIT, were developed by the ICT Competence Centre of University of Aveiro, which also provided the coordinators and the volunteers with online training sessions in order to better explore the provided KIT.

All the schools had access to the developed material through a Moodle platform course, created and managed by the DGE.

The course was developed in a total of 8 hours, divided into 4 sessions of 2 hours each. The KIT included all the resources needed to implement the sessions (multimedia presentations, video-tutorials, worksheets of the activities) plus guided plans of each session, which included detailed session plans, due to the lack of didactic knowledge of the volunteers.

The course had to be implemented in a face-to-face modality, so that the parents/tutors had all the help they needed. However, each school was allowed to manage the sessions according to the specificities of each context.

As the courses were running in a pandemic context, E-REDES provided the school with funds for extra costs deriving from the implementation of the course. Also, in order to promote the course and foster the enrolment of the families in the project, each family received supermarket vouchers and school supplies, offered by E-REDES.

2. Methodology

Our study followed a quantitative research methodology, of a descriptive nature, fitting into a Survey typology, having as universe all the parents/tutors who participated in the “Digital Academy for Parents” project, in the academic year of 2020/2021. Considering the official data provided by the DGE, a total of 995 participants were involved in the project, during this schoolyear.

The following objectives were defined for this study:

identify the self-perceived digital skills of parents/tutors who attended the training, seeking to determine the role of the training in the development of these skills;

determine the participants’ self-perception regarding the pursuit of the general objectives of the project;

determine the satisfaction of the parents/tutors involved in the project;

explore differences in the self-perceived digital competence according to the respondents’ characteristics;

explore differences in the self-perceived digital competence according to their satisfaction with the course.

In this paper, we will focus mainly on this last objective.

The option for the use of a survey was considered appropriate, as it is an instrument that is quickly disseminated and that effectively reaches the entire universe of respondents that we intended to reach, which is vast and geographically dispersed. According to (Given, Citation2008) surveys are one of the most used types of study in Educational Sciences, noting that “surveys can be used to study a variety of topics, including attitudes, beliefs, characteristics, traits, knowledge, behaviours, and anything else that can be reported by respondents.” (p.118), pointing to its usefulness in studies that intend to present self-perceptions within a group.

The development of the survey included a validation process by three specialists (one member of the ICT Competence Centre involved in the creation of the resources, one member of the DGE involved in the creation, development, and implementation of the project, and one school coordinator of the project). Also, after the experts’ validation, there was a commented application of the survey, with a tutor that had attended the course in the schoolyear 2020/2021 to ensure its adequacy to the target public.

The survey was made available to the respondents online, between May and NaN Invalid Date . According to (Bryman, Citation2016) making a questionnaire available online has advantages in terms of speed and convenience of response, not ignoring the low cost of its application. The same author also mentions as an advantage of this data collection procedure the fact that it is attractive to the respondent, and that it presents a lower probability of non-response or failure to respond to one or more questions.

The survey was structured in five parts, with a total of 53 questions, all of them closed-ended questions, except for an optional open-ended question in which parents/tutors were asked to freely add comments about the project. Also, the respondents were given the opportunity to add extra information, should they consider necessary, in another open-ended question.

Parts II and III, with 5 and 39 questions, respectively, were directly related to the objectives of the “Digital Academy for Parents” project and aimed to determine the participants’ perceptions regarding the pursuit of the general objectives defined for the project and the self-perception of the digital competences developed. For these questions a 5-points Likert scale was presented, since it is intended to measure the degree of intensity of the respondents’ opinions about a given phenomenon, aimed at obtaining information and allowing the subject some choice between a series of proposed degrees (Bryman, Citation2016).

Specifically, in part III the respondents were presented with a series of sentences, generated from the contents that were part of the course, asking the respondents to position themselves in a series of competences, after they had completed the course. This aimed to find out their self-perception on the competences developed through the attendance of the course.

In order to learn about their satisfaction, the respondents had a general question to state their satisfaction with the project (part IV), in which they were asked to position themselves in a 10 points scale (from 1 - dissatisfied to 10 - totally satisfied).

Part V was dedicated to the data regarding the characterization of the respondents. In this paper we will focus on the analysis of the data related to the satisfaction of the participants.

Cronbach’s Alpha tests were performed in order to analyse internal consistency of the Likert scale items presented in parts II and III. Data revealed high levels of consistency in both parts, as presented in .

Table 1. Results of the Cronbach Alpha for parts II and III of the questionnaire.

2.1. Subjects’ characterization

149 parents/tutors responded to our survey, which corresponds to 15% of the target population. Of these, 81,9% (n = 122) are female and 18,1% (n = 27) are male.

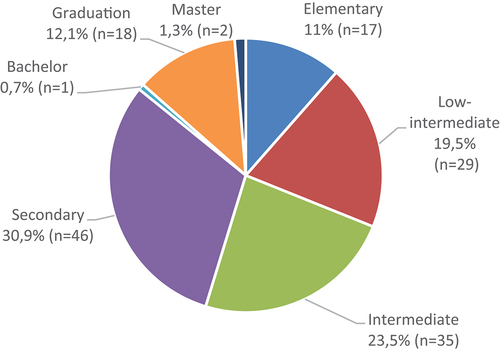

Regarding their educational qualifications, the majority of the respondents have completed a secondary education level (30,9%), followed by the 3rd educational level (23,5%), which corresponds to middle school. 19,5% and 11,4% of our respondents have, respectively, completed the 2nd or 1st educational level (which corresponds to elementary education). 14,1% of the respondents indicate having higher education qualifications (cf. ).

The majority of the tutors were mothers (79,2%), followed by fathers (17,4%). The course was open to everyone legally responsible for the students’ school path, so there were also grandparents, aunts, and siblings (1,3%).

When it comes to the professional situation of the respondents most of them were employed (55%), and some of these were self-employed (4,7%). The second largest group was unemployed (41,6%) and a small percentage mentioned that at the time, they were attending some sort of formal training (3,4%).

2.2. Results

As previously mentioned, in this paper we will focus on the last objective defined in our study, that is, to explore differences in the self-perceived digital competence according to the participants’ satisfaction with the course.

The levels of satisfaction were studied in two areas:

The respondents’ satisfaction with the course itself;

The respondents’ satisfaction with the attainment of the overall course objectives.

Firstly, it is relevant to present the overall results obtained regarding the self-perception of the respondents when it comes to the developed digital competences.

Our data point to a positive self-perception with an overall score of the digital competence of 3.97, which is close to 4 in the 5-point Likert scale, i.e., indicating that the parents/tutors who participated in the study consider the course helped them develop digital competences.

The second section of the questionnaire aimed at determining the respondents’ self-perception of the attainment of the overall objectives of the project defined by E-REDES and DGE (cf. E-REDES website), contained a set of statements related to these goals. Thus, faced with the statements “I feel more capable of using technologies in various areas of my life”, “I am more willing to go back to school (enrolling in a course at a ‘Centro Qualifica’Footnote2, for example)”, “I am more able to use digital technologies to accompany my child at school‘, ’I feel closer to my child’s school‘, and ’I have developed a more positive relationship with the School”, and based on a Likert scale of 5 points, the average is close to the value 4 of the scale, corresponding to “I agree”, with a total score of 3.9.

In section 4 of the questionnaire respondents were asked about their degree of satisfaction with the “Digital Academy for Parents” course, asking them to rate themselves on a 10-point scale. The results express high satisfaction with the project, since the reached average was 8.3 points.

Examining the distribution of responses by items, we found that, of the 149 respondents, only 2,7% (n = 4) indicated a degree of satisfaction below the average level (5). At level 5, we found 10,7% (n = 16) of the responses, with the remaining 86,5% (n = 130) respondents being at levels above 5. Levels 8 and 10 were the ones with the highest incidence of responses, with 18,1% (n = 27) and 41,6% (n = 62), respectively.

To understand whether the participants’ satisfaction with the course itself exerted differences in the participants’ self-perceived digital competence, we first performed descriptive tests, dividing the participants into 2 groups of satisfaction scores: satisfied and totally satisfied, considering in the group of “satisfied” participants who marked the values between 1 and 6 on the scale presented (n = 34), and “totally satisfied” those participants who marked satisfaction values between 7 and 10 (n = 72).

As we can see in , the self-perceived digital competence is higher in the group of participants with greater satisfaction with the course.

Table 2. Global score of the self-perceived digital competences.

In order to comparatively analyse the mean scores of the 2 defined groups, the t-Student test was performed, with the Levene’s test revealing that the variances are not homogeneous. T-Student tests revealed differences which are statistically significant, considering the overall degree of satisfaction with the course and the self-perceived digital competences, as presented in .

Table 3. Results of the t-Student test for satisfaction with the course and self-perceived digital competences.

In addition to trying to understand how the degree of general satisfaction exerted differences in the level of self-perceived digital competence, we considered relevant to analyse whether the degree of satisfaction with the pursuit of the overall objectives also exerted differences in the self-perception of digital competence development.

To this end, we divided the participants into two groups: those who considered that the program only partially fulfilled its objectives (average less than or equal to 4; n = 54) and those who considered that the program had overall fulfilled its objectives (average superior to 4; n = 52), verifying that the self-perception of digital competence is higher in the group of participants who consider that the course objectives have been fully achieved, as shows.

Table 4. Satisfaction with the overall objectives of the course and self-perceived digital competence.

In order to determine whether the differences detected were statistically significant between these two groups, the t-Student test was performed, and the Levene’s test revealed that the variances are not homogeneous. The t-Student tests revealed differences which are statistically significant, considering the degree of satisfaction with the pursuit of the general objectives of the course and the self-perceived digital competence (see ).

Table 5. Results of the t-Student test for attainment of the overall goals of the project and self-perceived digital competence.

3. Conclusions

The results indicate that those who attended the “Digital Academy for Parents” project have a positive self-perception of its impact in the development of their digital competences. To Parents/tutors, the digital competences acquired, not only allow them to support their children/students in school tasks, but also expand their skills to other areas of their lives. This digital empowerment is absolutely relevant when we are moving towards a greater digitalization of the services that citizens have access to in their daily lives, so attending the course contributed to the reduction of the existing digital divide.

In a macro analysis, the results point to the positive contribution that the attendance of the Digital Academy for Parents can make in the current context in which all citizens are sought to have digital skills that allow them to move in today’s society and contribute to the development of that same society. When we compare Portugal with the European Union, we see that the country has been making efforts and achieving positive results with regards to the development of the citizens’ basic digital skills. However, our results are still below the European Union average in the number of individuals with low qualifications in terms of basic digital skills (DESI Homepage, Citation2022).

The results of our study clearly show high levels of satisfaction with the course, as well as high levels of satisfaction with the attainment of the global goals of the project. The results also indicate that the levels of satisfaction exert an influence in the self-perceived digital competence of the respondents.

Therefore, we consider it relevant that the institutions responsible for the implementation of the course consider ways to guarantee high levels of participant satisfaction, either by designing activities that meet their expectations and needs, with attractive and exciting dynamics, and/or by ensuring that contents are approached in a pedagogically appropriate way, for example. In fact, it may be determinant to create mechanisms to verify points of satisfaction/dissatisfaction in order to improve the project and its outcomes.

As today’s world is characterized by increasing levels of digitalization, which demand new and everchanging competences from citizens, namely digital competences, the relevance of projects such as “Digital Academy for Parents” can be considered extremely high. Thus, we aimed at studying the project, namely its first year of implementation, trying to understand its impact in the promotion of the digital competence of citizens.

Although the project was born in a pandemic context, in a reaction to the needs felt by families, it is well framed in the European and national agendas, as they are marked by the definition of strategic objectives in the digital area, which imply a strong commitment to the empowerment of all citizens, as reflected, for example, in the objectives defined in the European program “Europe’s Digital Decade: digital objectives for 2030”. These same aims are pursued at the national level, with a set of measures and actions present in the Action Plan for the Digital Transition.

In fact, the project has not ended, and is now on its way to its 3rd edition, assuming a big importance on the lives of schools which, on their own initiative, wanted to learn more about the project and expressed their desire to implement it. With the expansion of the project to all school clusters, in the second year of implementation, the project grew with 28% of the country’s school clusters joining it, which represents close to 400 classes, as shown in the launch session of the second edition of the initiative. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m4kpa9Kw_d0).

Although the sample of our study may not be enough to be considered representative of the total population involved in the project, we consider it provides important insights, that may be useful to consider when designing and implementing similar projects, which can contribute to the development of the citizens’ digital competences and, in doing do, contribute to diminish the digital divide.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. TEIP- Programme for Priority Intervention Educational Areas – the aim of this programme is to promote educational inclusion in schools located in socio-economic disadvantaged areas.

2. Centro Qualifica – The Qualifica Program is a program aimed at adults with incomplete education and training, which aims at the improvement of their qualification levels, contributing to the progression of the population’s qualifications and the improvement of the employability of individuals.

References

- Affouneh, S., Salha, S., & Khlaif, Z. N. (2020). Designing quality e-learning environments for emergency remote teaching in coronavirus crisis, Interdisciplinary Journal of Virtual Learning in Medical Sciences, 11(2), 135–137.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- DESI Homepage. Retrieved August 28, 2022 from. https://digital-agenda-data.eu/charts/desi-components#chart={%22indicator%22:%22desi%22,%22breakdown-group%22:%22desi%22,%22unit-measure%22:%22pc_desi%22,%22time-period%22:%222022%22}

- Eastin, M., Cicchirillo, V. & Mabry, A. (2015). Extending the digital divide conversation: Examining the knowledge gap through media expectancies, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59:(3), 416–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1054994.

- E-REDES Homepage. Retrieved July 17, 2021. from https://www.e-redes.pt/pt-pt/academia-digital-para-pais

- European Commission: Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A digital agenda for Europe. 245 final. (2010).

- European Commission: Digital Education Action Plan: 2021–2027. (2020).

- European Commission: European Skills Agenda for sustainable competitiveness, social fairness and resilience. Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. 274 final, (2020).

- European Commission: Proposal for a Decision of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing the 2030 Policy Programme “Path to the Digital Decade”Brussels (2021). COM 574 final.

- European Commission: The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan (2021). Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. COM 102 Final.

- Ferrari, A. (2012). Digital competence in practice: An analysis of frameworks. JRC-IPTS, Seville.

- Given, L. (Ed). (2008). The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage Publications.

- Helsper, E. J., van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & Eynon, R. (2015). Tangible outcomes of internet use: From digital skills to tangible outcomes project report.

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review, 27, 1–1. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. (2007). Gradations in digital inclusion: Children, young people and the digital divide. New Media & Society, 9(4), 671–696. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807080335

- Lucas, M., Moreira, A., & Costa, N. (2017). Quadro europeu de referência para a competência digital: subsídios para a sua compreensão e desenvolvimento, Observatorio Journal, 11(4), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS11420171172

- Portugal Digital: Plano de Ação para a Transição Digital de Portugal. (2020). Plano de ação para a transição digital - Portugal Digital.

- Scheerder, A., van Deursen, A., & van Dijk, J. (2017). Determinants of Internet skills, uses and outcomes. A systematic review of the second- and third-level digital divide. Telematics and Informatics, 34(8), 1607–1624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.07.007

- Schleicher, A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on education. Insights from education at a glance 2020. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-education-insights-education-at-a-glance-2020.pdf.

- van Dijk, J. (2000). The Digital Divide as a Complex and Dynamic Phenomenon. https://www.utwente.nl/en/bms/vandijk/research/digital_divide/Digital_Divide_overigen/pdf_digitaldivide_website.pdf.