ABSTRACT

This paper provides a new set of Social Accounting Matrices (SAMs) for the EU-27 and describes their construction process. The World Input–Output Database (WIOD) has been used as the main data source, and it has been completed with information from National Accounts in Eurostat. The SAMs include a disaggregation of labour by skills and the disaggregation of the foreign sector into the EU and Rest of the world. It is described how to elaborate a symmetric Input–Output table product by product at purchasers’ prices using supply and use tables and applying the industry technology. It is also described the reallocation of social contributions needed to properly assign tax revenues to government and avoid the usually overlooked problems generated by the second redistribution of income. The description of the SAMs and their availability for the EU-27 can be very useful to researchers in applied economics using CGE and SAM models.

1. Introduction

The empirical analysis of any macroeconomic policy heavily relies on the availability and quality of data. Data in National Accounts provide a comprehensive set of definitions, variables and economic relations badly needed for monitoring and evaluating the performance of any region or country. Social accounting matrices (SAMs) are based on National Accounts and Input–Output (IO) tables; they have been defined as balanced square matrices that capture the circular flow of income for an economy in a specific period of time. SAMs display data such that rows account for income accruing from all accounts in the economic system and columns account for their expenditures. According to Pyatt (Citation1994), SAMs are extensions of Supply and Use tables (SUTs) that allow moving from static IO models to SAM and CGE models in which prices and quantities are interdependent.

The use of SAMs in policy analysis is not a new thing (Pyatt, Citation1988, Thorbecke, Citation2000, Round, Citation2003). But their construction and publication has been on the upswing of late (Santos, Citation2007, Lange and Schade, Citation2008, Deb Pal et al., Citation2012, Debowickz et al., Citation2013, Al-Riffai et al., Citation2016). In some cases, their construction has been motivated by the study of specific productive sectors, such as SAMs specifically elaborated for evaluating the economic effects of tourism (Jones, Citation2010), agriculture (Monge et al., Citation2014), energy (Cardenete et al., Citation2012). In other cases, they respond to the need of accounting for specific details not included in standard accounts as financial variables (Ayadi and Salem, Citation2014, Aray et al., Citation2017). Typically, SAMs are built for one single country or region, but the advent of such datasets as WIOD, which includes IO accounts for many countries, has made it possible to build nearly identical SAMs across a multitude of countries. Nevertheless, the elaboration and publication of SAMs remains difficult and time-consuming. This paper attempts to cover a data gap by providing a new set of homogeneous SAMs for the EU-27 that can be used directly in SAM and CGE models.

The SAMs, developed as reported herein, were designed to be a national constraint database in RHOMOLO v2, a regional holistic model that covers 27 nations of the European Union (EU-27) at the NUTS-2 level,Footnote1 but they also can be used in other studies due to their sectoral disaggregation.Footnote2 RHOMOLO v2 is a dynamic spatial general equilibrium model developed by the Directorate General Joint Research Centre (DG-JRC) for the Directorate General for Regional and Urban Policy (DG-REGIO) at the European Commission. It was designed to evaluate the effects of Cohesion and Structural policies on economic growth for all regions in the EU. Households, firms, government and the foreign sectors are included in RHOMOLO v2, and all economic transactions are defined as the result of agents’ optimized behaviour. Households are aggregated into one with preferences for variety à la Dixit and Stiglitz (Citation1977), and firms produce commodities that are consumed by other agents. Transportation costs are assumed to be of the iceberg type, and the R&D sector produces one specific differentiated good with increasing returns to scale. The model includes unemployment (Blanchfower and Oswald, Citation1995), a regional government sector and two foreign sectors: Rest of the EU and Rest of the world (RoW). More details on RHOMOLO v2 can be found in Mercenier et al. (Citation2016).

In constructing the SAMs, the main data sources were WIODFootnote3 and Eurostat. We detail the information used by source as well as the advantages and disadvantages embedded in each. We justify why we select data from either WIOD or Eurostat and discuss the limitations they possess. In general, the information for IO tables was extracted from WIOD, since among available multinational IO tables it paid the most attention to balancing trade flows among EU countries. Data on income distribution were directly taken from National Accounts, Eurostat. We took great effort to reconcile data from the two sources. Figures in SAMs are generally not the same as those registered in Eurostat since some numbers in WIOD have been estimated and, therefore, they do not always match those in Eurostat. This is especially the case for exports, imports and the foreign current balance. The SAMs also include a great amount of detail on transfers and tax revenue allocations.

The problems created by balancing inconsistent statistics have been early pointed out by several researchers (Stone et al., Citation1942; Stone, Citation1984) and have led to the development of a battery of balancing procedures. Nicolardi’s (Citation2013) method, which can simultaneously balance matrices in current and constant prices, is more flexible than others (Byron, Citation1978). Hosoe (Citation2014), on the other hand, evaluated the estimation errors in IO tables as well as prediction errors in CGE models by comparing the results of balancing symmetric tables and SAMs with cross entropy (CE) and least squares (LS) methods. He suggests that CE outperforms LS when only macroeconomic data are available. Scandizzo and Ferrarese (Citation2015) combine entropy minimization and Monte Carlo simulation techniques to estimate a SAM for Italy. Since we have available the macroeconomic data we need, we opt for a CE method in order to balance symmetric IO tables in purchasers’ prices.

The allocation of employers’ social security contributions to households first and to other agents in a second stage (second redistribution of income) included in National Accounts has been avoided in the SAMs by allocating these revenues just once to the appropriate agents. This simplifies the introduction of the information into RHOMOLO v2 or any other CGE model. To do this, we have combined and adjusted all information available in the national accounts and estimated missing data. On the other hand, the disaggregation of labour income by skill levels raises the utility of this database, which results in a convenient source for the analysis of income generation and distribution of different public policies and human-capital accumulation policies.

This document is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the main characteristics of the data sources used in the construction process, focussing on the advantages and drawbacks that lead to a decision on the data used to build the SAMs. In Section 3, the structure of the IO tables is detailed. Finally, Section 5 presents some conclusion remarks and the potential extensions of the database.

2. Available data sources: WIOD and Eurostat

In the elaboration of national SAMs, we have combined information from WIOD with data from National Accounts, Eurostat. WIOD is the first database to contain homogenized IO information for the EU-27 and 13 other countries in the worldFootnote4 (Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Russia, Taiwan, Turkey and the United States). This database has information on: world tables (SUTs, world IO tables [IOTs] and interregional national IO tables); national tables (SUT and national IO tables [NIOTs]) and socio-economic accounts [industry output, value added, capital stock, investment and wages and employment by skill type (high, medium and low)]. It is available for the period 1995–2011. We elaborate just its SAMs for 2010.

Most of the tables in WIOD are in both purchasers’ and previous-year prices, and national IO tables are valued in millions of United States (U.S.) dollars. The exchange rates for each country used to effect this possibility also are available in the database. The information is disposable for 35 industries (International Standard Industrial ClassificationFootnote5 Rev. 3 or NACEFootnote6 Rev. 1) and 59 products/commodities (CPA,Footnote7 1996). The database was originally elaborated for the period 1995–2009. Further updates and revisions of national SUTs were released in 2013 by using updated National Accounts data on expenditure for 2010–2011 and applying growth rates to 2009 figures (Timmer, Citation2013). This explains why some macroeconomic variables, like value added at basic prices and GDP, are slightly different to the numbers provided by Eurostat’s National Accounts.

In Eurostat, there are more detailed data on SUTs and symmetric IO tables than in WIOD regarding sectoral disaggregation and value-added components. In fact, Eurostat obtains information directly from national statistical offices. Unfortunately, some of that information, particularly the IO tables, is not always available for the same year for all countries. Additionally, symmetric tables are elaborated for some countries using the assumption of fixed sales structure (industry-by-industry) and in some others using the technology assumption (product-by-product). The sectoral breakdown is based on NACE Rev. 2. There is information for 17 out of the 28 EU countries for 2010 but no data for Croatia, as in WIOD. Tables for 2005 are available for Denmark, Spain, Luxembourg, Poland and Portugal but none for Bulgaria, Cyprus, Latvia, Malta and Croatia. Unlike WIOD, symmetric tables in Eurostat are strictly product-by-product, although Netherlands and Finland are exceptions.

Finally, the National AccountsFootnote8 provide very useful and detailed information on income distribution and government accounts, although for some countries there are minor inconsistencies and/or missing data. The disaggregation of compensation of employees between wages and salaries and employer’s social security contributions for the foreign sector is not available for 14 countries and the disaggregation of foreign sectors into EU and RoW is not available for 9 out of the 28 EU countries.

The main advantage of using IO tables from Eurostat instead of WIOD is that all numbers match with official National Accounts and few adjustments are needed. The data provided by the national statistical offices are balanced and there is consistency among SUT, SIOT and National Accounts. On the other hand, the lack of information for several countries and the different criteria used in symmetric IO tables, industry-by-industry in some countries and product-by-product in others, represent a clear limitation.

As a result of the analysis of the aforementioned data availability, data of IO tables have been directly obtained from WIOD while figures on primary and secondary distribution of income have been collected from Eurostat. In reconciling numbers from both data sources and to balance the SAMs, we have adjusted transfers and calculated savings as a residual. In the SAMs, gross savings from the EU and the RoW are the result of trade flows, tax revenues and productive factors incomes between national economies and the foreign sectors. The resulting numbers are very different from those registered for the same variables in National Accounts due to the huge difference of trade flow data between Eurostat and WIOD. The latter displays balanced trade flows among all the EU countries distinguishing by imports, exports, re-exports and international trade and transport margins. Eurostat data on value added and taxes have also been used as an auxiliary source for estimations, as explained in Section 3.2. In what follows, the details on the construction of the national SAMs are described.

3. The National SAMs for the EU-27 in 2010

The SAMs elaborated for the 27 EU countries are balanced square matrices of dimension 85×85. In these economies, there are four agents: households, corporations, the government and the foreign sector, which are divided into the EU and the RoW. There are 59 productive sectors,Footnote9 wages and employers’ social contributions by level of skill (high, medium and low), social contributions paid by employees, self-employed and unemployed and an account for capital. There are three accounts of taxes: direct taxes (households’ income tax and corporate income tax), taxes net of subsidies on products and other taxes net of subsidies on production. Additionally, there is an account for property income and three types of transfers: other current transfers, adjustments due to the participation of households in pension funds reserves and welfare benefits. Finally, there are two more accounts for gross fixed capital formation and stock variations, one for savings and three for trade and transport margins, international trade margins and re-exports, correspondingly. The last three accounts are explicitly included in WIOD in order to match the trade flows between countries and assure consistent flows within the EU and with the RoW.

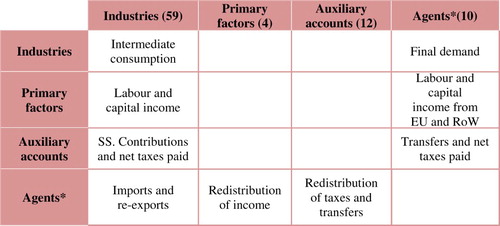

SAMs are naturally partitioned. In the case of those for the EU-27, the largest partition is the intermediate consumption matrix, which captures the intermediate consumption need by industries to produce their corresponding ‘homogeneous’ good. The partition of value added includes labour and capital income; other partitions are: taxes paid by industries and imports. The final demand partition details the amount of goods demanded per product by households, government, investment, stock variations and exports. Other partitions account the redistribution of income, tax revenues and transfers. Figure summarizes the partitions in the EU-27 SAMs.

In the row/column of agents, we include additional accounts that are not really considered agents within the economy. This is the case of: gross fixed capital formation, stock variations, trade and transport margins, re-exports and international trade and transport margins. In Figure , these accounts are included among agents in order to capture all the components of final demand, including investment and stock variations. The accounts of re-exports and international trade and transport margins are included in WIOD and do not appear in other data sources like Eurostat’s National Accounts and/or official national IO tables. The number of accounts (rows/columns) in each partition is detailed in parenthesis. Table displays these partition components, and Table presents an aggregated version of the project’s resulting Austrian SAM.

Figure 1. Main structure of SAMs EU-27.

Note: numbers in brackets account for the number of accounts (rows/columns) in the SAM. Source: own elaboration.

*Other accounts that are not agents in the economy are also included in these sub-matrices.

Table 1. Accounts in the SAMs EU-27.

Table 2. Social Accounting Matrix for Austria (million EUR).

Products in WIOD are classified according to CPA, using the NACE standard, see Table . In the following sections, we present the content of the partitions outlined in Figure and the adjustments implemented to match numbers.

Table 3. Productive sectors in the SAMs for EU-27 in 2010.

3.1. Intermediate consumption

The intermediate symmetric IO table is a 59×59 homogeneous square matrix in purchasers’ prices elaborated with data from SUTs from WIOD. A symmetric IO table can be defined as a table where the same definition for products/industries is used both in columns and rows (Eurostat, Citation2008). SUTs are rectangular matrices in which columns reflect industries and rows products. Usually product detail is more disaggregated than that for industries, such that most industries produce more than one good. The extent that they do so depends on the variety of their primary and secondary production. Symmetric tables, which traditionally have been used for analytical purposes related to production, summarize the information included in SUTs, which are more descriptive and data-oriented. The fact that symmetric tables are more likely to be used as analytical tools is largely due to analytical (data-driven) assumptions required for the particular applications.

Symmetric IO matrices in basic prices can result from the transformation of SUTs using a technology assumption, which result in product-by-product symmetric tables that relate products (rows) with homogeneous units of production (columns), or as a result of a fixed sales structure – industry-by-industry symmetric tables. These two construction procedures: technology assumption and fixed sales structure lead to two additional approaches each, based on the product or industry technology assumption used in the former and on the fixed sales structure on products or industries in the latter. We describe the main characteristics in what follows. A complete description can be found in Eurostat (Citation2008).

First, under the technology assumption (product-by-product), two approaches can be applied: product technology (PT) or industry technology (IT). The PT conversion implies to reallocate secondary production embedded in supply tables to the industries where their main production good is that specific product. Consequently, rows and columns are reorganized in such a way that every industry produces only one composite homogeneous good. In measuring and reallocating secondary production, however, negative numbers can result in symmetric tables. These numbers can crop up for different reasons: the product technology assumption might be faulty; what is recorded can be economic transactions rather than technological relations; data recording errors, etc. Using the IT procedure avoids these problems. It captures the idea that all products elaborated by a specific industry are always produced via the same technology, irrespectively of the specific product actually made. The intermediate part captures inter-industries relations about how industries use products in production.

Second, under the fixed sales structure (industry-by-industry) tables may capture the production of goods that are also produced by other industries since they capture very well the relations among different industries. They do not reallocate secondary production and the same good can be produced by different sectors using each sector a specific sales structure (fixed industry sales structure, FI) or the same good can be produced by different sectors using all the same sales structure (fixed product sales structure, FP).

According to Beutel (Citation2017), the most common method applied to product-by-product IO tables is the PT method, while for industry-by-industry IO tables it is the FP technology. He notes that the implementation of the FP technique is quite straight forward and avoids negative transactions but it has a weak link to product-based statistics. The problem of negatives in PT is quite relevant and, in most cases, mandates the application of manual balancing procedures. This makes life extremely difficult for small research teams that might be tasked with producing large databases. Rueda-Cantuche (Citation2017) provides a clear technical explanation of the transformation methods and discusses the arguments in favour and against product-by-product or industry-by-industry IO tables as well as the various procedures presently used to eliminate any negative values that might appear.

As mentioned, industry-by-industry tables are ‘closer to statistical sources and actual observations’ (Eurostat, Citation2008). But the ESA-95 favours product-by-product tables (technology assumption, Eurostat Citation2008. p. 301) since they are theoretically more homogeneous and more appropriate in many types of IO studies. We have followed the ESA-95 recommendation and therefore have elaborated intermediate consumption matrices in the SAMs EU-27 following the technology assumption. Additional information on the conversion of SUTs into symmetric can be found in Eurostat (Citation2008) and Miller and Blair (Citation2009).

Symmetric tables provided by WIOD are industry-by-industry and in basic prices. Consequently, they cannot be directly combined with information of final demand in Use tables by products at purchasers’ prices. In this case, the rows of the new matrix show products as in the Use table and since final demand at purchaser’ prices by type of goods is available in WIOD, we have preferred to use the technology assumption for building a product-by-product symmetric table, since no adjustment is needed on the demand side. On the other hand, the EU-27 SAMs will be used as a database to evaluate the impact of different policies on public investment demand, so it seems quite reasonable to construct new product-by-product symmetric tables in purchasers’ prices for all countries. The product-by-product transformation process applied here is based on the technology assumption detailed in Eurostat (Citation2008, Model B in Figure 11.2), which avoids the problem of negatives (ten Raa and Rueda-Cantuche, Citation2013). This is a relevant issue in the construction of large databases, particular so here since it is the one we present in this paper. In any case, Eurostat also is in favour of it (Rueda-Cantuche, Citation2017).

The transformation of the symmetric table from basic prices and into purchasers’ prices implies the need to include net taxes on products associated with intermediate consumption and also trade and transport margins. These are adjusted using a cross-entropy (CE) program, c.f., Robinson et al. (Citation2001). There are several balancing methods that can be used to update and adjust SAMs and IO Tables. In this case, we use it to adjust the value of the matrix and eliminate inconsistences. Every balancing procedure begins by evaluating starting values in relation to their plausibility by comparing the figures across both different national datasets and across time if it is possible (Beutel, Citation2017).

Of course, a particular balancing procedure also must be chosen. The most popular are: RAS (Lahr and De Mesnard, Citation2004), GRAS (Temurshoev et al., Citation2013) and CE. RAS is a biproportional matrix balancing technique that iteratively changes rows and columns in a matrix using proportions based on known margins. It is a simple algorithm that cannot work with negative values and that requires a minimum set of data. GRAS is a modified version of RAS that allows for negative numbers in SAMs and IOTs. On the other hand, like algorithms in the RAS family, CE minimizes distances between datasets but it has the advantage of estimating a consistent database starting with an inconsistent dataset. Plus, it is sufficiently flexible that it can readily incorporate known information about specific parts of the matrix to be estimated. RAS and CE have been compared in several papers. McDougall (Citation1999) points to the superiority of RAS, for problems both can manage it is much more efficient. But when more data issues get more complex, researcher appears to favour CE (Robinson et al., Citation2001). Thus we balanced the symmetric IO tables using the CE approach.

As said before, we have converted transaction flows in the symmetric tables from basic into purchasers’ prices. Hence, taxes and trade and transport margins are redistributed across columns and included as a part of intermediate demand. Nevertheless, trade and transport margins associated with final demand are not included in the intermediate consumption in the new matrix, exactly as it happens with net taxes on products. For this reason, domestic trade and transport margins from the supply table are included in an additional row in the same way that net taxes on products are also registered as payments that industries do to this specific account. One of the reasons why these adjustments are needed is because margins affecting final demand are not included in the intermediate matrix. On the other hand, the amount of the margins (taxes) paid through the demand of each commodity does not need to be equal to the amount of the margins collected in the course of the sale of that commodity; consequently, total supply does not match total demand. Therefore, we needed to add an additional row to the trade and transport margins column included in the Supply table.Footnote10 SUTs in WIOD are expressed in national currency. Table displays the countries that did not belong to the Eurozone in 2010 as well as the exchange rates that we applied.

Table 4. Exchange rates national currency/euros.

3.2. Value added and taxes

The disaggregation of value-added components (rows) by industries (columns) composes another important partition in the SAMs. Value added is usually disaggregated into wages and salaries, employer’s social contributions, gross operating surplus and other net taxes on production (NTP). The value-added components that are available in the socio-economic accounts (SEA) in WIOD are capital compensation, labour compensation and compensation of employees.Footnote11 Value-added figures have been elaborated for 35 industries, and total figures match the sum of the accounts in WIOD for labour compensation and capital compensation. Unfortunately for us, in WIOD NTP are merged with capital compensation. The difference between compensation of employees and labour compensation is that the latter includes wages received by self-employed. These rents are usually accounted as mixed income in Eurostat’s National Accounts, where again they are combined with capital compensation. We allocate the difference between labour compensation and compensation of employees to gross operating surplus. We also disaggregate compensation of employees into wages and salaries and employers’ social contributions. And, finally, we have subtracted NTP from capital compensation. Further the accounts of wages and salaries and employers’ social contributions have been disaggregated by skill level using the information available in WIOD for 2009. The definitions of skills used in WIOD are detailed in Table .

Table 5. Skill level definition based on education level attained.

The disaggregation of value added from WIOD has been completed using more detailed data available from Eurostat. This is the case for NTP and the disaggregation of compensation of employees into wages and salaries and employers’ social contributions. First, data on other net taxes on production, NTP, by industry (NACE Rev. 1.1) have been collected from Eurostat National AccountsFootnote12 and SUIOTs.Footnote13 These sources offer data on value-added components but generally for years prior to 2010 and for 2010 itself only for two countries. In the other cases, we relied on data for 2009 (9 countries) or 2008 (7 countries), and even 2007 (4 countries) or before (2 countries). After the analysis of both sources, we concluded that the National Account tables provided more recent and better information for 17 countries,Footnote14 but that preferred data from the SUIOTs for 9 countries.Footnote15 Unfortunately, no disaggregation of NTP by industry exists for Cyprus in any dataset available to us.

Given the data source for each country, we calculated total NTP by applying the share of NTP over GVA in this source over total GVA from WIOD. Then we broke out total NTP by industry applying industry shares observed in Eurostat data sources. In doing this, we assumed that the distribution by NTP industry for 2010 was the same as that actually observed in the closest previous year for which the data were available. In the case of Cyprus, we approximated the distribution of NTP using data from Malta since no data could be had from Eurostat. In this case, we first obtained total NTP from Eurostat for 2010,Footnote16 which is not available by industry according to NACE Rev. 1.1; second, we applied the share of NTP over GVA in this source to the total GVA from WIOD; third, we obtained the distribution of NTP by industry by applying Malta’s observed shares. The disaggregation of taxes by industries was more complicated than the disaggregation for other variables since net taxes can be positive or negative in any given year and any given industry. Thus, in order to avoid arbitrary results, the disaggregation of NTP by industry was made while respecting the positive or negative sign of the last observed year (Eurostat).

Similarly, the disaggregation of compensation of employees (COMP) into wages and salaries (WS) and employers’ social contributions (SCE) was made by applying shares obtained from Eurostat’s National Accounts and SUIOT. WS and SCE are disaggregated by industry (NACE Rev. 1.1) in Eurostat. We later applied these shares of WS and SCE over COMP from Eurostat to the values of COMP by industry from the WIOD-SEA.

The disaggregation of WS and SCE by skill level was derived using WIOD data for 2009. Labour skills are divided into high, medium and low, according to the education level attained, which were applied in the form of shares. These shares, available for 2009, were applied to the compensation of employees in 2010. Finally, RAS was used to assure that total values by rows matched those for columns for all industries.

3.3. Redistribution of income and transactions

The matrix of redistribution of income and transactions (see Figure ) is the cross-tabulation of all auxiliary accounts included in the SAMs in order to capture the primary and second redistribution of income among institutional sectors. Primary factors income is redistributed among the aggregate household, the corporate sector, the government and the foreign sector, divided into EU and RoW. In it, tax revenues and current transfers are allocated following available data on Eurostat National Accounts.

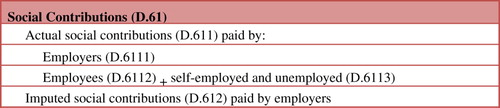

The primary and second distributions displayed in National Accounts present some trouble for SAM builders. The main problem is that social security contributions paid by employers and employees are first allocated to households and later on are transferred from households to other agents. This would be a straightforward issue if all revenues from contributions were allocated to government, but according to National Accounts they are allocated to households, corporations and government, and it is the re-routed transfers of SC that are unclear in Eurostat National Accounts. On the other hand, because all contributions paid by employers and employees are transferred to households, it is also difficult to disentangle the allocation of contributions of employers from contributions of employees. According to the European system of accounts 1995, Eurostat (Citation1996), social contributions are structured as shown in Figure .

Figure 2. Disaggregation of social contributions.

Note: ESA 95 codes are shown in brackets.

Source: own elaboration based ESA 95.

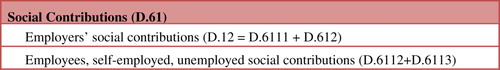

A main interest in a SAM is to understand how employers’ social contributions paid by firms and detailed in IO tables by industry and coming from the foreign sector are redistributed among the institutional agents in the economy. That is, we are interested in social contributions from the perspective of distributive transactions (Figure ). The available information in National Accounts with respect to social contributions paid and received by the different agents in the economy is detailed in Table . There are data for employers’ social contributions (SC) (D.12) and total SC (D.61) but not for employees, self-employed and unemployed (D.6112 + D6.113). On the other hand, total SC (D.61) are disaggregated into actual (D.611) and imputed (D.612). Taking into account this information, and that imputed contributions can only be due to Employers’ SC, then Actual Employers’ SC received (D6.111) can be calculated as the difference between Employers’ SC received (D.12(R)) and Imputed SC paid (D.612(P)) (see Table ).

Figure 3. Social contributions as distributive transactions.

Note: ESA 95 codes are shown in brackets

Table 6. Social contributions (Austria 2010).

Table 7. Actual Employers’ social contributions (D.6111) (Austria 2010).

Following the structure in Figure , in order to disentangle social contributions of employers and employees and their redistribution, we have reordered some of the cells in Table and calculated some additional figures in Table . The row corresponding to SC by employees, self-employed and unemployed (D.6112 + D6.113) is computed deducting from total contributions (D.61) those corresponding to employers (D.6111 + D.612).

Table 8. Allocation of social contributions (Austria 2010).

Contributions paid by households other than employers’ SC are calculated as a balance. We know the value of actual (44,387) and imputed (5984) SC paid by households. Subtracting from the aggregation of previous figures the amount of employers’ SC received by households (27,173), which are paid by sectors, and the difference in total contributions due to the RoW (−102), we may approximate the amount of contributions of employees, self-employed and unemployed paid by households. The SC of employees paid by industries and that employees do not receive, since they are directly discounted from their payrolls, are included in wages and salaries in National Accounts. On the other hand, unemployment benefits are included as a transfer in current transfers and because unemployed also paid contributions they should be implicitly included in these transfers in National Accounts. Later, households pay all of these transfers. The SC retained by households are due to imputed contributions; consequently, they have been allocated to employers’ social contributions. In relation to the corporate sector and the government, total contributions received by these agents are available from National Accounts. This ratio of contributions received by corporations and by government is used to distribute employer’s SC between these two agents. Then around 7.7% of the revenues of employer’s SC go to corporations and 92.3% go to the government in Austria. These shares have been applied to the resulting number of net employers’ SC paid by households (27,173–100) plus net contributions received by the EU (85–217) and the RoW (71-41). The figures in SC of employees, self-employees and unemployed are calculated as a balance.

As can be observed in Table , there is a −102 imbalance in total SC, which does not appear in the disentangled figures of the contributions where total paid figures are equal to total revenues. If we aggregate the value of SC of employers and SC of employees paid by households (27,173 + 23,300) the resulting figure is €102 million larger than the figure provided by National Accounts (D.61) included in the table. The reason is we are correcting this difference when estimating the value of SC of employees paid by households. According to the available information, the sum of contributions of employers paid by the production sectors is equal to the SC figure of employers later redistributed to domestic agents, without including the positive/negative balance derived from the foreign sector. This issue has been observed for all countries in the EU.

Other net taxes on production are allocated to government and other net taxes on products are redistributed between the government and the EU using the information from National Accounts. Value added and taxes on imports are included in other net taxes on products and there is a part of revenues that always goes to the EU authorities. This is reflected in the SAMs.

3.4. Final demand

The final demand partition captures the amount of products used by different agents in the economy (households, government, corporations and the foreign sector) for final consumption and investment (gross fixed capital formation and stock variations). The figures corresponding to these transactions are directly taken from the national use tables in WIOD at purchasers’ prices. The aggregation of final demand by product and the intermediate demand from the symmetric IO table is equal to total demand and it matches total supply by product.

The institutional sectors in the SAMs have revenues from different sources (factor incomes, transfers, etc.) that they use for paying taxes – the composite household and the corporate sector pay direct taxes – and transfers. Net revenues pay for consumption, and savings are calculated as a residual. The aggregation of domestic (households, corporations and government) and foreign savings (the current balance account from the EU and the RoW) are used to fund gross fixed capital formation and stock variations.

Exports constitute the final demand of the foreign sector. These data on exports to the EU-27 and the RoW are not directly available from WIOD because national SUTs do not provide any distinction by origin and destination. The data in the SAMs come from WIOD’s ISUT. Exports in the ISUT can be obtained by reversing the perspective of imports. In the measurement of imports, the reporting country in the Use table is the importer country, which consumes products domestically produced as well as imported, but it can be also taken as the country of destination for all the goods exported by the country of origin. In this way, we only measure exports for the 40 countries in WIOD and not for the others. There is no specific Use table for the regions not included in WIOD. Hence, the commodities sent to these territories cannot be directly observed. For this reason, we have combined the information on exports in national use tables with the value of exports reported for the 40 countries in ISUT. For each EU-27 country, we have the total exports by product from national SUTs, and we take the total of exports by product to the EU-27 region from the ISUT. The difference between these two figures corresponds to exports to the RoW. Both in national and international use tables, exports are valued at FOB (free on board).

3.5. The foreign sector: imports and re-exports

Imports from the EU and the RoW together with value added and intermediate consumption add total supply by product. The data on imports have been obtained from the information included in the ISUT. They are at FOB values and international trade and transport margins (ITM) are included in a different account. The FOB valuation has been used in WIOD in order to have coherent numbers of bilateral trade flows since any import is also an export for another country. Unlike the usual account of national trade and transport margins included in national supply tables, the sums of the ITM included in the SAMs are not equal to zero. According to Timmer (Citation2012), these figures have been elaborated in WIOD using data from UN COMTRADE and the national data in the margins sectors of transport and trade. As mentioned, there is an account of re-exports that is part of total supply. The valuation of this variable is not clear in WIOD, but as they are defined as ‘total use minus imports in CIF in cases if the latter are larger than the former’, it can be assumed that they are valued at FOB.

Re-exports are assumed not to be part of domestic production, so their value has been subtracted from total imports in CIF. The corresponding bilateral flows have been adjusted proportionally. All foreign trade flows are valued in FOB, which requires the introduction of a new account in our SAMs that is estimated in WIOD and named ‘International trade and transport margins’. This account captures the bilateral trade and transport margins by product category. The logic of this account is that there are services which are produced in different countries, and consequently reported in supply tables, but are not actually consumed in the same country where they are produced and they are registered in use tables of other countries in form of commodities valued at CIF.

These margins have been obtained from combining national SUTs with information from the bilateral trade database that was constructed within the WIOD project. In the ISUT, the use table for each country is broken down by origin, being the latter one of the 40 countries reported in WIOD or the RoW. Hence, we can deduct imports by origin and aggregate them into two categories, EU-27 and RoW. Since there are no specific data for Croatia, the trade information for this country is implicitly included in the account of the RoW.

Usually, re-exports are not included in such specific way in national SAMs as they are in the present way. But WIOD includes information on them in order to balance international trade flows. In this regard, Timmer (Citation2012) discuss the matter briefly, and Dietzenbacher et al. (Citation2013) discuss the set of processing trade, re-exports and transit-trade. But the database’s documentation does not make a precise distinction between ‘goods that are sent abroad for processing’ and ‘re-exports’. That is, in WIOD tables re-exports are not only affecting trade flows (imports and exports) but also the production technology through national intermediate matrices since the main idea is to capture the underlying industry technologies and not only the value-added generated. This is particularly important for countries like China and the US. But a key problem arises when adjusting trade flows to properly capture the value of imports and exports excluding not in processing trade but in pure re-exports (also called transit trade), that is the flow of commodities that goes from country A to C through country B without suffering any minor or major change. In this regard, if the figures included in ISUT under the name re-exports also include processing trade the amount of this pure re-exports is unavailable and consequently it is very difficult to understand their technological distribution in intermediate consumption, albeit we hope mostly in the form of inventory carrying costs (insurance, warehousing and finance). In the present case, where the SAMs are elaborated for the purpose of being used as databases in a CGE model, we want the trade relating to the pure re-exports themselves to be extracted from the trade accounts and properly registered as trade flows for origin and destination pairs of trade partner countries and avoid any intermediate step. But the lack of information on exactly how the re-exports are accounted in WIOD made this adjustment difficult.

On other transfers and income flow data for the foreign sector, some countries do not bifurcate these accounts into those for the EU and those for the RoW. In some cases, even compensation of employees is not disaggregated into wages and salaries and employer’s social contributions. In the first case, we applied the average weights of EU and RoW from all the other EU countries where this information was available. For the second, we also calculated the corresponding average weights of salaries and contributions from all the other EU countries where this information was available and applied the shares to split the compensation of employees.

Non-residents’ consumption is registered by a transfer from the foreign sectors to households, and residents’ consumption abroad is included in the SAM as a transfer from the aggregate household to the foreign sectors. These data have been taken from the WIOD-SUTs. Hence, the column vector consumption accounts for commodity consumption in the territory made by residents and non-residents.

3.6. The reconciliation of data sources and their adjustments

This section provides information on the assumptions made to reconcile the two main data sources used in SAMs and the impact of the overall adjustments made to fill in the information gaps and matrices’ imbalances.

Value added and taxes. The decomposition of value added in its four components is a case in which we combined data from WIOD and Eurostat National Accounts. As explained in Section 3.2, National Accounts and SUIOT from Eurostat are combined with data from WIOD’s SEA to break out value added into wages and salaries, employer’s social contributions, gross operating surplus and other net taxes on production. In a first step, the percentage distribution of NTP over GVA in Eurostat is applied to GVA from WIOD; and, in a second step, the break out of NTP by industry from the former is applied to the latter. A possible origin of disagreement between WIOD and Eurostat comes from the difference in GVA between the two sources, because for 2010, the WIOD update elaborated for 1995–2009 did not use official Eurostat data, rather it was derived by applying growth rates (Timmer, Citation2013). Table provides an overview of the difference in GVA between the two sources. It shows that in most countries the difference is less than 2%, with deviations of more than 5% only in Bulgaria and Greece. Outside of this, Eurostat data are only used to derive shares that are applied to WIOD aggregates.

Table 9. GVA at basic prices in 2010 from Eurostat and WIOD.

For estimates of NTP by industry, the 2010 figures from National Accounts and SUIOT for most EU-27 countries are generally unavailable. So we assumed, for any country, that the distribution of net taxes and their positive or negative sign by industry did not change between the last year with available NTP data and 2010. Following a similar approach, we disaggregated compensation of employees from WIOD-SEA into wages and salaries and employers’ social contributions using the shares observed by Eurostat. The disaggregation of this variables by skill levels using WIOD-SEA data for 2009 was made by assuming that:

The shares by skill levels for the compensation of employees were the same as those for labour compensation. To test the accuracy of this assumption, we accounted for different distributions of skill level between the two groups composing labour compensation – namely COMP and mixed income of self-employed. If the self-employed had different levels of education than employees, we would have altered the composition of this group. But we found the impact of this assumption was limited since most of labour compensation figures relied on the compensation of employees: an average of 87% of labour compensation is due to COMP in WIOD.

The shares for 2010 were the same as those for 2009. When observable, we find these shares vary little from year to year.

The disaggregation of employees’ compensation for the foreign sector was effected by applying the average share observed for the countries in which the data were available. The observed mean proportion of wages and salaries over total compensation is 84.5% for the foreign sector, while social contributions account for 15.5%. Other features of the distribution of the observed proportions suggest symmetry and normality, therefore the choice of the mean as an estimator for the missing values is not unreasonable. Another factor in favour is the low overall impact of the foreign sector’s compensation of employees; on average, and with the exception of Luxembourg, it accounts for less than 1.0% of total compensation of employees of the observed national economies.

4. Conclusion

This paper describes the main data sources used in the construction of SAMs for 27 EU countries; Croatia is not included. It also outlines their use for a comparative analysis of SAM multipliers in national economies. In this set of matrices, the second redistribution of income has been adjusted in order to facilitate the elaboration of more realistic (CGE) models. We made special effort to disaggregate Social Contributions (SC) of employers and employees, as well as what we believe is a better allocation of activity to government and other institutional sectors. The latter avoids the initial allocation of SC of employers to households and later on to other agents of the economy, mainly the government.

The starting point is the set SUTs at basic and purchasers’ prices for all EU-27 countries in WIOD. This information was used to elaborate a 59×59 symmetric national IO table in purchasers’ prices using a bi-proportional adjustment method. The symmetric matrices were completed using data from Eurostat National Accounts to close the circular flow of income.

The matrices resulting from our exercise closely resemble the Eurostat National Accounts and all numbers are comparable to official public data sources. We are confident that, if they replicate our process, readers will arrive at the same figures.

The set of matrices as developed in this paper should prove to be an important tool for researchers who seek to evaluate public policies in the EU, either for one country or for all EU-27 countries. In particular, the SAMs have been elaborated to be national aggregates that will constrain NUTS-2 regional SAMs that will be the core data for RHOMOLO v2 – a regional CGE model developed by the EC to analyse the likely effects of EU cohesion and structural policies (López-Cobo, Citation2016).

This is undoubtedly the most up-to-date set of compatible national matrices for Europe that has been benchmarked to publicly available official data. Still, there are other issues related to them that should be further evaluated in the future. One issue is related to trade flows and the concept of re-exports included in WIOD. As mentioned before, it was difficult for us to clearly understand this variable within the WIOD context and, particularly, how re-exports and/or processing trade affect the production technology and trade flows among the EU countries and the RoW. The SAMs we produced distinguished these two trade types, and any reallocation of trade flows due to a different interpretation of these concepts within WIOD could yield significant changes to foreign trade balances. Also, in the SAMs discussed herein, taxes net of subsidies on production are not disaggregated into a value-added tax, taxes on imports and other net taxes on products. A common feature in many recent SAMs is to present only one household sector although the truly social dimension of any SAM, and explicitly included in the name, is the disaggregation of households.Footnote17 The SAMs presented in the document do also have one composite household, while labour income is disaggregated by skill level. One desirable extension would be to divide the composite household by main income source. This issue could be an important feature for those researchers interested in the analysis of poverty and inequality, but it would be a potentially tedious and time-consuming task, one rarely undertaken by statistical offices. In this regard, it would be even more complex to carry out for all 27 EU countries. These and other aspirations could be interesting and valuable, but difficult to implement. We invite any and all researchers with an interest to extend the current database.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the comments and suggestions from all the members of the RHOMOLO team and from José Manuel Rueda-Cantuche and Alfredo Mainar. We are also grateful to Umed Temursho and Bart Los for helping us to better understand the WIOD database and three anonymous referees and the editor, Michael Lahr, for their useful comments. The authors are solely responsible for the content of the paper. The views expressed are purely those of the authors and may not under any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the European Commission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) classification is a hierarchical classification system to divide the EU territory for the purpose of collection, development and harmonization of EU regional statistics, and socio-economic analyses of the regions and for the framing of EU regional policies. NUTS-2 levels correspond to regions for the application of regional policies (Eurostat Citation2011).

2 The SAMs for the EU-27 are available in supplemental data for this article, which are available online from the publisher.

3 WIOD database is a project funded by the European Commission, Research Directorate General as part of the 7th Framework Programme, Theme 8: Socio-Economic Sciences and Humanities. Grant Agreement no: 225 281.

4 There are no data for Croatia.

5 The International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) system is a United Nations (UN) industry classification system.

6 NACE (Nomenclature des Activités Économiques dans la Communauté Européenne) is a standard industry classification system used by the European Union. It is the European implementation of the UN’s ISIC.

7 Acronym for the Classification of Products by Activity (CPA) that is used for statistics in the European Economic Community.

8 Eurostat (Citation2014a).

9 We have elaborated a symmetric 59×59 IO table using data from supply and use tables.

10 The flexibility of SAMs allows researchers to adapt the structure of these matrices to the purpose of the analysis. In this case, we used symmetric tables in purchasers’ prices, but we just as easily could have adjusted WIOD SUTs instead.

11 The nomenclature used in WIOD is not the same used in Eurostat’s National Accounts. We apply the official standard terminology by ESA and recent figures from WIOD have been adjusted as explained in the following paragraph.

12 Eurostat (Citation2014b).

13 National SUIOTs according to NACE Rev.1.1. Downloaded on 2014 July 15.

14 This source offers more complete information by sector, and it is available for years 2008, 2009 or 2010. It is used for the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, France, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, Netherlands, Austria, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia and Finland.

15 SUIOT are used for Belgium, Bulgaria, Ireland, Greece, Spain, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and United Kingdom. The most recent available data varies from 2005 to 2009 depending on the country.

16 Eurostat (Citation2014c). Annual National Accounts: National Accounts aggregates and employment by sector 2010 (NACE Rev. 2) (nama_nace64_c) [Data file]. Downloaded on 2014 July 8. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

17 The proper name of these matrices is National Accounting Matrices (NAMs) but the use of the name SAM has been extended also for matrices where the household sector is not disaggregated.

References

- Al-Riffai, P., S. Moussa, A. Khalil, F. Hussein, E. Serag, N. Hassan, A. Fathy, A. Samieh, M. ElSarawy, E. Farouk, S. Souliman, and A. Abdel-Ghafour (2016) A Disaggregated Social Accounting Matrix: 2010/11 for Policy Analysis in Egypt (Egypt SSP Working Paper 2. Washington, DC and Cairo, Egypt: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)).

- Aray, H., L. Pedauga and A. Velázquez (2017) Financial Social Accounting Matrix: A Useful Tool for Understanding the Macro-Financial Linkages of an Economy. Economic Systems Research, 29, 486–508. doi: 10.1080/09535314.2017.1365049

- Ayadi, M. and H. Salem (2014) Construction of Financial Social Accounting Matrix for Tunisia. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5, 216-221.

- Beutel, J. (2017) The Supply and Use Framework of National Accounts. In: Thijs ten Raa (ed.) Handbook of Input–Output Analysis. Cheltenham, UK, Edward Elgar Publishing, 41–132.

- Blanchflower D.G. and A.J. Oswald (1995) An Introduction to the Wage Curve. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(3), 153-167.

- Byron, R.P. (1978) The Estimation of Large Social Account Matrices. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), 141, 359–367.

- Cardenete, M.A., P. Fuentes and C. Polo (2012) Energy Intensities and Carbon Dioxide Emissions in a Social Accounting Matrix Model of the Andalusian Economy. Research and Analysis, 16, 378–386.

- Deb Pal, B., S. Pohit and J. Roy (2012) Social Accounting Matrix for India. Economic Systems Research, 24, 77–99. doi: 10.1080/09535314.2011.618824

- Debowickz, D., P.A. Dorosh, H.S. Haider and S. Robinson (2013) A Disaggregated and Macro-Consistent Social Accounting Matrix for Pakistan. Journal of Economic Structures, 2, 4.

- Dietzenbacher, E., B. Los, R. Stehrer, M. Timmer and G. de Vries (2013) The Construction of World Input–Output Tables in the WIOD Project. Economic Systems Research, 25, 71–98. doi: 10.1080/09535314.2012.761180

- Dixit A.K. and J.E. Stiglitz (1977) Monopolistic Competition and Optimum Product Diversity. American Economic Review, 67, 297–308.

- Eurostat (1996) European System of Accounts (ESA 1995). Luxembourg.

- Eurostat (2008) Eurostat Manual of Supply, Use and Input–Output Tables. Luxembourg.

- Eurostat (2011) Regions in the European Union. Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics. NUTS 2010/EU-27. Luxembourg.

- Eurostat (2014a) National Accounts (ESA95). Annual sector accounts 2010 (nasa_nf_tr) [Data file]. Downloaded on 2014 November 14 (last update: 2014-08-22). http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

- Eurostat (2014b) National Accounts (ESA95). National Accounts by 60-sector aggregates at current prices (nama_nace60_c) [Data file]. Downloaded on 2014 July 16 (last update: 2014-02-15). http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

- Eurostat (2014c) Annual National Accounts: National Accounts aggregates and employment by sector 2010 (NACE Rev. 2) (nama_nace64_c) [Data file]. Downloaded on 2014 July 8. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

- Hosoe, N. (2014) Estimation Errors in Input–Output Tables and Prediction Errors in Computable General Equilibrium Analysis. Economic Modelling, 42, 277–286.

- Jones, S. (2010) The Economic Contribution of Tourism in Mozambique: Insights from a Social Accounting Matrix. Development Southern Africa, 27, 679–696.

- Lange, G.M. and K. Schade (2008) A Social Accounting Matrix for Namibia, 2004: A Tool for Analyzing Economic Growth, Income Distribution and Poverty. NEPRU Working Paper 112. Namibian Economic Policy Research Unit, Windhoek.

- Lahr, M.L. and L. De Mesnard (2004) Biproportional Techniques in Input–Output Analysis: Table Updating and Structural Analysis, Economic Systems Research, 16, 115–134.

- López-Cobo, M. (2016) Regionalisation of Social Accounting Matrices for the EU-28 in 2010. Working Paper JRC104029, Joint Research Centre, Seville, Spain.

- McDougall, R. (1999) Entropy Theory and RAS are Friends. GTAP Working Papers 300. Center for Global Trade Analysis, Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, USA.

- Mercenier, J., M.T. Álvarez-Martínez, A. Brandsma, F. Di Comite, O. Diukanova, D. Kancs, P. Lecca, M. López-Cobo, P. Monfort, D. Persyn, A. Rillaers, M. Thissen and W. Torfs (2016) RHOMOLO-v2 Model Description: A Spatial Computable General Equilibrium Model for EU Regions and Sectors. JRC Working Papers JRC100011, Joint Research Centre, Seville, Spain.

- Miller R.E. and P.D. Blair (2009) Input–Output Analysis: Foundations and Extensions, 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press.

- Monge, J.J., H.L. Bryant and D.P. Anderson (2014) Development of Regional Social Accounting Matrices with Detailed Agricultural Land Rent Data and Improved Value-Added Components for USA. Economic Systems Research, 26, 486–510. doi: 10.1080/09535314.2014.889663

- Nicolardi, V. (2013) Simultaneously Balancing Supply and Use Tables at Current and Constant Prices: A New Procedure. Economic Systems Research, 25, 409–434.

- Pyatt, G. (1988) A SAM Approach to Modeling. Journal of Policy Modeling, 10, 327–352.

- Pyatt, G. (1994) Modelling Commodity Balances in a Computable General Equilibrium Context. Economic Systems Research, 6, 123–134. doi:doi: 10.1080/09535319400000012

- Robinson, S., A. Cattaneo and M. El-Said (2001) Updating and Estimating a Social Accounting Matrix Using Cross Entropy Methods. Economic Systems Research, 13, 47–64.

- Round, J. (2003) Constructing SAMs for Development Policy Analysis: Lessons Learned and Challenges Ahead. Economic Systems Research, 15, 161–183.

- Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. (2017) The Construction of Input–Output Coefficients. In: Thijs ten Raa (ed.) Handbook of Input–Output Analysis. Cheltenham, UK, Edward Elgar Publishing, 133–174.

- Santos, S. (2007) Modelling Economic Circuit Flows in a Social Accounting Matrix Framework. An Application to Portugal. Applied Economics, 39, 1753–1771.

- Scandizzo, P.L. and C. Ferrarese (2015) Social Accounting Matrix: a New Estimation Methodology. Journal of Policy Modeling, 37, 14–34.

- Stone, J.R.N., D. Champernowne and J.E. Meade (1942) The Precision of National Income Estimates. The Review of Economic Studies, 9, 111–112.

- Stone, R. (1984) Balancing the National Accounts: The Adjustment of Initial Estimates – A Neglected Stage in Measurement. In: A. Ingham and A.M. Ulph (eds.) Demand, Equilibrium and Trade: Essays in Honor of Ivor F. Pearce. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 191–212.

- Temurshoev, U., R.E. Miller and M.C. Bouwmeester (2013) A Note on the GRAS Method. Economic Systems Research, 25, 361–367.

- ten Raa, T. and J.M. Rueda-Cantuche (2013) The Problem of Negatives Generated by the Commodity Technology Model in Input–Output Analysis: A Review of the Solutions. Journal of Economic Structures, 2, 5.

- Thorbecke, E. (2000) The Use of Social Accounting Matrices in Modelling (Unpublished paper presented at the 26th General Conference of the International Association for Research in Income and Wealth, Kraków, Poland).

- Timmer, M., ed. (2012) The World Input–Output Database (WIOD): Contents, Sources and Methods. WIOD Working Paper Number 10. http://www.wiod.org/publications/papers/wiod10.pdf.

- Timmer, M. (2013) Updates and Revisions of National SUTs for the November 2013 release of the WIOD. (Working paper, WIOD.).