Abstract

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is a common autoimmune hematological disorder. Despite this, diagnosis is still challenging due to clinical heterogeneity and the lack of a specific diagnostic test. New findings in the pathology and the availability of new drugs have led to the development of different guidelines worldwide. In the present study, the Delphi methodology has been used to get a consensus on the management of adult patients with ITP in Spain and to help in decision-making. The Delphi questionnaire has been designed by a scientific ad hoc committee and has been divided into 13 topics, with a total of 127 items, covering the maximum possible scenarios for the management of ITP. As a result of the study, a total consensus of 81% has been reached. It is concluded that this Delphi consensus provides practical recommendations on topics related to diagnosis and management of ITP patients to help doctors to improve outcomes. Some aspects remain unclear, without consensus among the experts. Thus, more advances are needed to optimize ITP management.

Plain Language Summary

What is the context?

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is a hematologic autoimmune disease characterized by accelerated destruction and inadequate production of platelets mediated by autoantibodies (platelet count <100 × 109 /L).

Despite being a common condition, its heterogeneous clinical course makes its diagnosis and management still a challenge.

In recent years, new molecules with different mechanisms of action have emerged for the treatment of ITP.

Due to the increasing information about the pathology and its therapies, several international guidelines have recently been established to provide recommendations for the management and treatment of ITP.

There are still many patient scenarios and disease aspects which are not addressed in the guidelines.

What is new?

Our Spanish ITP Expert Group has developed a Delphi consensus study to provide recommendations and promote standardization of the management of adult patients with ITP in Spain.

The scientific committee defined 127 statements for consensus, corresponding to 13 chapters: (i) Diagnosis of ITP, (ii) First-line treatment, (iii) Second-line treatment, (iv) Treatment of refractory patients, (v) Follow-up, (vi) Emergency and surgery, (vii) ITP in the elderly, (viii) ITP in pregnancy, (ix) Anticoagulation and antiplatelet, (x) Secondary ITP, (xi) Quality of life, (xii) Discontinuation of TPO-RA, and (xiii) ITP and Covid.

The total number of agreed statements achieved was 103, giving a final percentage of consensus in the Delphi questionnaire of 81%.

What is the impact?

This Delphi consensus provides recommendations based on real clinical practice data, regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and management of patients and scenarios in ITP to assist clinicians in addressing this disease and achieving optimal outcomes for the patient.

Introduction

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by isolated thrombocytopenia with a platelet count <100 × 109/L.Citation1,Citation2 Its diagnosis remains one of exclusion, as there is no definitive test or clinical feature to establish it. This fact together with its highly variable presentation and clinical course, makes ITP difficult to diagnose.Citation3,Citation4

The pathogenesis relies on both accelerated destruction and inadequate production of platelets mediated by autoantibodies.Citation5

ITP can be primary, when the thrombocytopenia occurs in the absence of other conditions that may be associated with it, or secondary, in which ITP develops in association with another disorder such as autoimmune, infectious, or lymphoproliferative diseases.Citation1

The incidence of ITP ranges from 1.6 to 3.9 new cases per 100,000 patients per year, increasing with age.Citation6,Citation7 Approximately, 20% are secondary ITP.Citation5,Citation8

ITP may not uniformly exhibit purpura or bleeding manifestations,Citation2 even being asymptomatic in some patients. However, when symptoms are present, bleeding is the most common one and can be as mild as petechial, purpura, or severe and even life threatening in cases of intracranial hemorrhage, and massive gastrointestinal or urinary tract bleeding.Citation6

Reduced health-related quality of life is also a feature associated with ITP.Citation6,Citation9 Physical and mental health is impaired compared to the general population. Fatigue is another major concern for these patients, being the most frequent and top symptom wanted to be resolved.Citation10

The mortality rate of ITP will depend on age. The age-adjusted rates were 0.004, 0.012, and 0.130 cases per patient-year for age groups younger than 40, 40 to 60, and older than 60 years, respectively,Citation11 mainly due to hemorrhage, infections, and ineffective treatment.Citation12

Corticosteroids remain the standard initial treatment for newly diagnosed patients.Citation13 They decrease platelet clearance and increase platelet production.Citation14 Additionally, they may reduce bleeding, through a direct effect on blood vessels.Citation15 However, the side effects of corticosteroids outweigh the benefits in the long-termCitation16 and have promoted research and availability of new treatments in the last decade. The use of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs) in ITP is also well-established.Citation17 They inhibit the phagocytosis of antibody-coated platelets and usually achieve a rapid but short-lived platelet increase.Citation18 They are usually used in combination with corticosteroids or as a first line in patients requiring a very rapid increase in platelet count.Citation19 Romiplostim, eltrombopag, and avatrombopag, this latter approved in 2019, are thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RA). They mimic the physiological activity of thrombopoietin and are indicated in cases of insufficient response to prior treatment (corticosteroids, IVIGs, or splenectomy). They increase platelet production and reduce bleeding.Citation20–22 Rituximab can also improve platelet count responses at 6 months in ITP patients.Citation23 Long-term data for rituximab have become available since 2010. Fostamatinib, a spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor was approved in 2018 for treatment of adults with chronic ITP who have had insufficient responses to prior treatments.Citation24–26

Due to the increasing therapeutic options, several guidelines have recently been published in different countries and internationally.Citation13,Citation18,Citation19,Citation27–29 The Spanish Group of ITP (GEPTI) has the commitment of maintaining updated guidelines on this disease. In this way, the aim of this Delphi consensus study is to develop new recommendations to help in decision-making and promote standardization of the management of adult patients with ITP in Spain.

Materials and methods

Scientific committee

The scientific committee consisted of 8 renowned opinion leaders in hematology. Their functions consisted of reviewing the literature on new developments in ITP, designing the Delphi questionnaire based on this evidence and clinical experience, and selecting the panel of experts to answer the questionnaire. Once the responses of the experts were obtained, the scientific committee was also in charge of analyzing the results, discussing them, and drawing the conclusions of the study.

Panel of experts

The panel of experts was chosen based on the experience and recognition of each physician and was composed of 31 hematologists from different hospitals nationwide.

Delphi methodology

According to the scientific evidence and clinical practice, a consensus was reached using Delphi methodologyCitation30 to assess the controversies identified between the different guidelines and clinical practice, reach a consensus, and debate and make recommendations for the management of ITP.

The scientific committee defined 127 statements for consensus (See supplementary material, Appendix S1) which were divided into 13 chapters: (i) Diagnosis of ITP, (ii) First-line treatment, (iii) Second-line treatment, (iv) Treatment of refractory patients, (v) Follow-up, (vi) Emergency and surgery, (vii) ITP in the elderly, (viii) ITP in pregnancy, (ix) Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy, (x) Secondary ITP, (xi) Quality of life, (xii) Discontinuation of TPO-RA, and (xiii) ITP and Covid. The questionnaire was sent online to the experts, the answer to the statements was in a Likert scale mode, and they had the option to comment on their response.

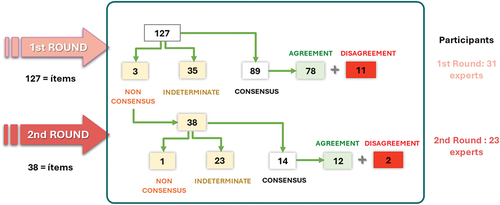

For the statistical analysis of the Delphi questionnaire, see supplementary material (Appendix S2). Here, we show the flow chart describing the process by which these recommendations were made ().

Results

The 31 experts who composed the panel of experts responded to the first round of the Delphi questionnaire. The second round was answered by 23 of these experts.

A total of 127 statements defined by the scientific committee were submitted to the first round for consensus. The expert panel reached a consensus of agreement on 71 of the 127 statements, and all experts came to a consensus on rejecting the statement on 11, which means a total consensus of 71%. The 38 statements for which consensus was not reached were subjected to a second round, reaching agreement in 12 and coming to a consensus on rejecting the statement in 2, which means 37% consensus in the second round. The total number of agreed statements, now considering both rounds, amounted to 103, so that the final percentage of consensus reached in the Delphi questionnaire was 81%.

Itp diagnosis

Experts have reached consensus that vaccination may trigger ITP more frequently in children than in adults. They also agree that Helicobacter pylori infection should be ruled out in adults with ITP and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Experts agree that the physical examination should be based on the search for hemorrhagic lesions, presence of visceromegaly, lymphadenopathy, and tumors. It is also essential to check the peripheral blood smear. Scales should be used to assess the severity of bleeding.

Experts do not consider it necessary for diagnosis to study bone marrow, nor to detect antiplatelet antibodies.

First-line treatment

Experts agree that treatment should be started in adult patients with newly diagnosed ITP and platelet count <20 × 109/L, without clinical signs of bleeding or bleeding risk factors. However, there is no consensus that treatment should be initiated in pediatric patients with the same characteristics.

The panel does agree that treatment of newly diagnosed ITP should be initiated with corticosteroids if there are no contraindications and that the maximum duration of treatment at maximum dose should be limited to 3 or 4 weeks. There is also consensus that TPO-RA can be used in the treatment of newly diagnosed ITP. As for IVIG, there is consensus that they should be used in situations of hemorrhage ≥WHO Grade II and that, prior to their use, a sample should be taken for serology and autoimmunity studies.

Second-line treatment

As the first option in the second-line treatment of ITP, experts recommend TPO-RA; in contrast, they do not recommend rituximab or fostamatinib. If a patient needs treatment to maintain a platelet count >20–30 × 109 /L despite previous treatment with corticosteroids for 8 weeks, experts agree to switch to second-line treatment. If a TPO-RA fails, experts prefer to start a second TPO-RA instead of changing to another type of treatment. And they agree that in chronic ITP the most important thing is to preserve quality of life and avoid side effects of treatments.

Treatment of refractory patients

The panel has reached consensus that before labeling an ITP as refractory, it is mandatory to rule out other entities that may cause thrombocytopenia.

In refractory ITP, experts agree that bone marrow biopsy generally does not show abnormal findings, but there is a subgroup of patients who may benefit from it. Mortality in refractory patients is agreed to be high due to bleeding, but also due to serious infections and thrombotic events.

Experts agree that therapeutic abstention should be considered in patients without hemorrhagic symptoms, a platelet count <20 × 109/L and good quality of life.

And in case of poor response to a single agent, experts agree that the possibility of synergy in the combination of fostamatinib with TPO-RA may be a valid option.

Follow-up

Experts agree that patients with chronic ITP, with or without active treatment, having stable platelet count may be suitable for remote follow-up visits. In addition, follow-up of chronic ITP without active treatment should be adapted to the patient’s lifestyle (e.g. travel, physical activity…).

Experts agree that patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed ITP with platelet counts <20 × 109/L and/or moderate-severe bleeding should be admitted for treatment. Patients with ITP under antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy should have closer follow-up due to increased bleeding risk. If during follow-up the patient reports asthenia of unknown cause, the experts agree that a worsening of the ITP should be suspected, and a timely platelet count performed. In patients who have received prolonged corticotherapy, osteoporosis must be ruled out and adequate treatment must be given.

For a patient with a previous diagnosis of ITP during pregnancy who is pregnant again, there is consensus that she should be considered a high-risk pregnancy to be controlled jointly by obstetricians and hematologists.

Emergency and surgery

Experts agree on considering indication for urgent treatment in ITP two clinical settings: (i) With platelet count <50 × 109/L and active bleeding in a major organ (central nervous system, lung, digestive tract, urinary tract, peritoneal hemorrhage). (ii) With platelet count <20 × 109/L and high risk of active bleeding in a major organ.

In patients with ITP needing neuraxial anesthesia or lumbar puncture, the platelet count must be >80 × 109/L.

To increase the platelet count in an emergency or non-delayable surgical situation: (i) The indicated IVIG dose is 1 g/kg/day. Experts rejected any need to delay retreatment for 48 to 72 hours in cases of an inadequate response to administer a new dose of IVIG if the response is not adequate. (ii) The corticosteroid of choice is dexamethasone at a total dose of 40 mg/day × 4 days.

Experts agree that antifibrinolytic drugs are indicated in any moderate/severe bleeding except in cases of hematuria.

In emergency situations, or severe or life-threatening bleeding, TPO-RAs are an option if the need for elevated platelet counts beyond 7 days is foreseen.

Itp in the elderly

In elderly patients with suspected ITP, experts agree that a bone marrow study should be performed in case of (i) Other alterations in the blood count, (ii) Peripheral blood smear findings suggesting another underlying disease, or (iii) If there is no response to the usual treatments for ITP.

Thrombotic risk should be considered when initiating treatment for ITP. In case of platelet counts >30 × 109/L, treatment should be initiated only if the patient has comorbidities that increase the risk of bleeding or requires antithrombotic treatment.

Experts agree that the first-line treatment of choice for elderly patients is prednisone at lower than usual doses (0.5 mg/kg/day). If IVIG is used, doses of 0.4 g/kg/day for 4–5 days are recommended versus the usual 1 g/kg/day for 1–2 days. The expert-recommended second-line treatment of choice is TPO-RA. Splenectomy is less effective in the elderly than in younger patients and has a higher rate of infectious and thrombotic complications.

Itp in pregnancy

There is consensus that treatment of ITP in pregnancy should be considered: (i) When platelets <20 × 109/L, and (ii) In case of hemorrhagic symptoms, need for antithrombotic treatment or invasive procedures, even if the platelet count is >30 × 109/L.

There is agreement that the first-line treatment for ITP in pregnancy is oral corticosteroids. If splenectomy is considered in pregnant patients with refractory ITP, it should be performed in the second trimester of pregnancy. TPO-RA can be used in the third trimester of pregnancy in severe and refractory cases.

For cesarean section under general anesthesia, experts agree that the safe platelet count is 50 × 109/L. And for delivery under epidural anesthesia, a platelet count >70 × 109/L is required.

Experts agree to perform a platelet count in cord blood. If the platelet count in the neonate is <30 × 109/L, experts recommend the administration of IVIG. If it is <50 × 109/L and there is intracranial hemorrhage on transfontanelar ultrasound, the administration of IVIG and corticosteroids is recommended.

Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy

Consensus has been reached that the criteria for primary prophylaxis with anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents should be the same in patients with ITP. Single and dual antiplatelet therapy with platelets >50 × 109 /L is considered to be safe in patients with ITP. On the contrary, they do not consider it safe with platelets >20 × 109 /L.

Finally, in patients with ITP and a stable platelet count >50 × 109/L, when considering the risk of bleeding, there is no consensus on whether or not anti-vitamin K drugs are safer than direct oral anticoagulants.

Secondary itp

There is consensus that the most common causes of secondary ITP in adults are hematological malignancies and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); and in children, primary immunodeficiency and SLE. Other causes include mostly low-grade B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (B NHL) and SARS-CoV-2 infection.

There is agreement that hydroxychloroquine is an effective option in the treatment of ITP secondary to SLE. Also, it is agreed that TPO-RAs, used with caution, are effective in secondary ITP in case the underlying disease increases the thrombotic risk.

In case of Helicobacter Pylori infection and very low platelet counts or bleeding, experts agree that eradication therapy should be prescribed along with ITP treatment.

Quality of life (QoL)

There is agreement among experts that patients with acute ITP have better QoL than patients with chronic ITP.

Experts agree that the assessment of QoL in ITP patients should be routinely performed in good clinical practice. To this end, the use of QoL scales, especially ITP-specific scales, is recommended before initiation and during treatment.

Experts agree that increased platelet counts, reduced bleeding, as well as reduced duration of corticosteroids alone or as concomitant therapy, are associated with improvements in the patient’s health-related QoL (HRQoL). In addition, there is consensus that treatment with TPO-RAs has led to an improvement in QoL in both adults and children. When choosing a TPO-RA, it is important to consider patient’s needs and the option less interfering the patient’s way of life. Experts agree that patients prefer an oral treatment without food restrictions.

Discontinuation of TPO-RAs

Consensus has been reached that to initiate tapering of TPO-RA doses with the intention of discontinuing treatment, the patient must have a stable platelet count ≥50 × 109/L for at least 6 months without need for concomitant medication.

Experts agree that the tapering period should last several months, the dose reduction should be a maximum of 30% per week and should be performed at least every 2 weeks with regular checks of the platelet count. In the case of discontinued TPO-RA treatment, if the platelet count falls below 20 × 109/L or bleeding occurs, experts agree to restart it.

Itp and covid

Consensus has been reached that a platelet count <20 × 109/L detected 2–7 days after SARS-CoV-2 infection should be considered a possible “de novo” ITP. This “de novo” ITP should be treated with the same guidelines as a “de novo” ITP not associated with infection.

The panel agrees that therapy in patients with ITP treated with TPO-RA and active SARS-CoV-2 infection should not be modified.

There is consensus that patients with COVID-19 presenting with ITP with platelet counts <20 × 109/L should not receive anticoagulation therapy. If urgent elevation of platelet counts is necessary, IVIG should be used.

Discussion

ITP is an autoimmune disease characterized by a heterogeneous clinical course. Because of this, diagnosis and management are challenging, having a remarkable impact on the patient’s quality of life. Despite recent advances in the approach of ITP, many areas need further research.Citation31

In terms of diagnosis, there was controversy about performing a blood count in citrate and manual blood count to rule out false thrombocytopenia; some experts considered the smear to be sufficient, based on their clinical practice. There was also no consensus that patients with ITP and positive autoimmunity tests should be referred to a specialized autoimmune disease service; some commented that this was not sufficient evidence and others that it was necessary to rule out an autoimmune disease at this point. Nor was there consensus that antiphospholipid antibodies should be tested for before the use of TPO-RA or other agents that may increase thrombotic risk.

Regarding first-line treatment, experts recommend starting a newly diagnosed patient with corticosteroids, a well-established practice.Citation13,Citation18,Citation19,Citation27–29 However, due to the good long-term results and good safety profile, the experts agree that starting with TPO-RA can also be explored, where they disagree is that the WHO classification of bleeding grade should be used to decide on the treatment modality.

In terms of stopping antiplatelet therapy in newly diagnosed ITP patients, they agree if platelet counts <30 × 109/L are present. However, there is no consensus if platelets <50 × 109/L. Some authors comment that the indication for antiplatelet therapy deserves an individualized assessment.

There is evidence of the benefits of TPO-RAs as a second-line treatmentCitation32 and experts recommend them. However, while thrombopoietin analogues are recommended as drugs of choice for second-line treatment of ITP, experts recommend the use of fostamatinib as the first therapeutic option in patients with ITP and high thrombotic risk. The use of rituximab before fostamatinib is also not advised. If a TPO-RA fails, there is controversy in preferring to start fostamatinib rather than switching to a second TPO-RA and in adding low doses of corticosteroids to the current TPO-RA before switching. In case of therapeutic failure of two TPO-RAs, there is also no consensus on starting a third TPO-RA instead of changing to another type of treatment. Some experts hesitate to exhaust treatment options. In addition, at this point, there are differences among centers regarding the accessibility of drugs, which may influence therapeutic decisions.

In refractory patients, experts agree that the best treatment remains to be defined and the risk/benefit of any treatment should be carefully assessed on an individual basis.

For the follow-up of patients with ITP, there was controversy that they should be advised to avoid activities with a high risk of injury and/or bleeding, such as contact sports, even if they are stable and maintain hemostatic platelet counts (≥50 × 109/L). Some authors think that the risk in this case is low and would depend on the platelet count and consider that in this situation it should be a patient’s choice.

In patients with ITP and elective surgery, experts did not reach consensus that TPO-RA should be used: (i) Even if there is no refractoriness to corticosteroids and/or IVIG; (ii) If the specific date of surgery is known and is less than 3 weeks away; or (iii) To increase platelet counts in an emergency situation and in the face of a shortage of IVIG.

In elderly patients with ITP, the approach differs from younger patients, due to the greater risk of bleeding and thrombosis, comorbidities, possible impaired mental health, concomitant treatments, and poor life expectancy.Citation33 Experts agree that the first-line treatment of choice is prednisone at 0.5 mg/kg/day, and second-line TPO-RAs, as established in other guidelines.Citation17–19,Citation29

In the case of ITP in pregnancy, it is a population at risk, due to the higher rate of adverse effects in the mother and in the fetus, and a lower probability of response than in the non-pregnant population.Citation34 Experts recommend oral corticosteroids as first-line treatment, as establishedCitation13,Citation18,Citation19,Citation27,Citation34 and, in severe or refractory cases, TPO-RA can be used in the last trimester.

For procedures where neuraxial anesthesia is required, experts recommend a platelet count >80 × 109/L. However, for epidural anesthesia in pregnancy, they recommend a platelet count >70 × 109/L; both results are in line with the international guidelines.Citation13 However, a platelet count for these procedures must be >80 × 109/L even in pregnancy for other recommendations.Citation18,Citation19 Therefore, there is a lack of consensus among the expert recommendations’ guidelines.

In special situations, experts have not reached a consensus that dual antiplatelet therapy is safe with platelets >20 × 109/L. The discrepancy is that some experts, based on their experience, would raise the threshold to 30 × 109/L to be safe. In patients with ITP and high cardiovascular risk, opinions are divided as to whether the most appropriate second-line treatment of choice should be TPO-RA, fostamatinib, or rituximab. However, they do agree that it should not be splenectomy.

With respect to secondary ITP, experts agree that management in the initial phase is the same as in primary ITP. As for second- or third-line treatments, they should consider the underlying disease and its degree of activity, as suggested by other authors.Citation35,Citation36

There is consensus that the deterioration in the quality of life (QoL) of ITP patients not only affects their physical health but also their mental health, work environment, and social relationships. Fatigue is a significant symptom of multifactorial etiology present in many ITP patients, limiting participation in daily activities and impairing QoL. These agreements are in line with several studies showing impairment of QoL in different aspects including productivity,Citation6,Citation9,Citation37,Citation38 which sometimes makes them even leave their employment, becoming a financial and social problem.Citation4

For the tapering of TPO-RA, there is evidence that up to 30% of ITP patients receiving TPO-RAs can achieve sustained responses lasting for months after discontinuation.Citation39,Citation40 For this topic, raised the controversy that the patient must have platelet count ≥50 × 109/L for at least 3 months; some experts do not consider it as sufficient, being in line with the conclusions of other studiesCitation41,Citation42 There is also no consensus that the patient should be in complete response (platelet count ≥100 × 109/L) in a stable manner for at least 3 or 6 months without need for concomitant medication; some experts think that a complete response is not necessary for this and that it may also depend on the patient’s needs. Finally, there is no consensus that once TPO-RA treatment has been discontinued, if a low platelet count forces us to restart treatment for a few weeks, the possibility of permanently discontinuing TPO-RA should be discarded.

Regarding COVID-19, experts recommend that patients with ITP should be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 and that, after vaccination, other causes of immune thrombocytopenia should be investigated, and platelet counts should be more closely monitored. However, there are doubts among the experts on whether to perform a platelet count 3–7 days before and after the vaccination date; some experts are of the opinion that it depends on the individual case. There is also no consensus that in cases of a major exacerbation of ITP after vaccination, an additional dose of vaccine should not be administered; they comment that it will depend on the severity of exacerbation.

Conclusion

This Delphi consensus provides recommendations on certain topics related to the diagnosis, treatment, and management of patients and situations in ITP in order to help the clinician address this disease and achieve outcomes for the patient. A few aspects have remained unclarified; therefore, improvements are still necessary for the optimization of ITP management.

Author contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the study presented. All authors have read and approved the article.

Original manuscript statement

This manuscript has not been published in any language or has been submitted to any other journal at the same time.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (722 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Luzán 5 Health Consulting for their support with the Delphi methodology, and Estefanía Hurtado Gómez for the medical writing.

Disclosure statement

Tomás José González-López has received research grants from Sobi, Grifols, Amgen, and Novartis and speaker honoraria from Sobi, Grifols, Amgen, Novartis, Momenta, Alpine, and Argenx. Isidro Jarque reports consulting honorarium from Amgen, Novartis, and Shionogi. Rest of authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2024.2336104.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kistangari G, McCrae KR. Immune thrombocytopenia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(3):495–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2013.03.001.

- Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, Michel M, Provan D, Arnold DM, Bussel JB, Cines DB, Chong BH, Cooper N, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113(11):2386–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-162503.

- Cines DB, Bussel JB. How I treat idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Blood. 2005;1062:244–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4598.

- Cooper N, Kruse A, Kruse C, Watson S, Morgan M, Provan D, Ghanima W, Arnold DM, Tomiyama Y, Santoro C, et al. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) World Impact Survey (I-WISh): Impact of ITP on health-related quality of life. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(2):199–207. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26036.

- Cines DB, Bussel JB, Liebman HA, Luning Prak ET. The ITP syndrome: pathogenic and clinical diversity. Blood. 2009;113(26):6511–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-129155.

- Segal JB, Powe NR. Prevalence of immune thrombocytopenia: analyses of administrative data. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(11):2377–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02147.x.

- Kohli R, Chaturvedi S. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of immune thrombocytopenia. Haemostaseologie. 2019;39(3):238–49. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1683416.

- Moulis G, Germain J, Comont T, Brun N, Dingremont C, Castel B, Arista S, Sailler L, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Beyne-Rauzy O, et al. Newly diagnosed immune thrombocytopenia adults: clinical epidemiology, exposure to treatments, and evolution. Results of the CARMEN multicenter prospective cohort. Am J Hematol. 2017 Jun;92(6):493–500. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24702.

- Efficace F, Mandelli F, Fazi P, Santoro C, Gaidano G, Cottone F, Borchiellini A, Carpenedo M, Simula MP, Di Giacomo V, et al. Health-related quality of life and burden of fatigue in patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia by phase of disease. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(10):995–1001. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24463.

- Cooper N, Kruse A, Kruse C, Watson S, Morgan M, Provan D, Ghanima W, Arnold DM, Tomiyama Y, Santoro C, et al. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) World Impact Survey (iWish): patient and physician perceptions of diagnosis, signs and symptoms, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(2):188–98. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26045.

- Cohen YC, Djulbegovic B, Shamai-Lubovitz O, Mozes B. The bleeding risk and natural history of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in patients with persistent low platelet counts. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(11):1630–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1630.

- Portielje JE, Westendorp RG, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Brand A. Morbidity and mortality in adults with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2001;97(9):2549–54. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.9.2549.

- Provan D, Arnold DM, Bussel JB, Chong BH, Cooper N, Gernsheimer T, Ghanima W, Godeau B, González-López TJ, Grainger J, et al. Updated international consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. 2019;3(22):3780–817. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000812.

- Gernsheimer T, Stratton J, Ballem PJ, Slichter SJ. Mechanisms of response to treatment in autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(15):974–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904133201505.

- Kitchens CS. Amelioration of endothelial abnormalities by prednisone in experimental thrombocytopenia in the rabbit. J Clin Invest. 1977;60(5):1129–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI108864.

- Guidry JA, George JN, Vesely SK, Kennison SM, Terrell DR. Corticosteroid side-effects and risk for bleeding in immune thrombocytopenic purpura: patient and hematologist perspectives. Eur J Haematol. 2009;83(3):175–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01265.x.

- Provan D, Stasi R, Newland AC, Blanchette VS, Bolton-Maggs P, Bussel JB, Chong BH, Cines DB, Gernsheimer TB, Godeau B, et al. International consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2010;115(2):168–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-225565.

- Matzdorff A, Meyer O, Ostermann H, Kiefel V, Eberl W, Kühne T, Pabinger I, Rummel M. Immune thrombocytopenia - Current diagnostics and therapy: recommendations of a joint working group of DGHO, ÖGHO, SGH, GPOH, and DGTI. Oncol Res Treat. 2018;41(Suppl 5):1–30. doi: 10.1159/000492187.

- Lozano ML, Sanz MA, Vicente V. Directrices de diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento de la PTI. Recomendaciones del grupo de trabajo de la SEHH y GEPTI. 1ª ed. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Hematología y Hemoterapia; 2020.

- Marshall AL, Scarpone R, De Greef M, Bird R, Kuter DJ. Remissions after long-term use of romiplostim for immune thrombocytopenia. Haematologica. 2016;101(12):476–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.151886.

- Wong RSM, Saleh MN, Khelif A, Salama A, Portella MSO, Burgess P, Bussel JB. Safety and efficacy of long-term treatment of chronic/persistent ITP with eltrombopag: final results of the EXTEND study. Blood. 2017;130(23):2527–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-748707.

- Al-Samkari H, Nagalla S. Efficacy and safety evaluation of avatrombopag in immune thrombocytopenia: analyses of a phase III study and long-term extension. Platelets. 2022;33(2):257–64. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2021.1881952.

- Chugh S, Darvish-Kazem S, Lim W, Crowther MA, Ghanima W, Wang G, Heddle NM, Kelton JG, Arnold DM. Rituximab plus standard of care for treatment of primary immune thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2(2):75–81. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00003-4.

- Bussel J, Arnold DM, Grossbard E, Mayer J, Trelinski J, Homenda W, Hellmann A, Windyga J, Sivcheva L, Khalafallah AA, et al. Fostamatinib for the treatment of adult persistent and chronic immune thrombocytopenia: results of two phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(7):921–30. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25125.

- Bussel JB, Arnold DM, Boxer MA, Cooper N, Mayer J, Zayed H, Tong S, Duliege A-M. Long-term fostamatinib treatment in adults with immune thrombocytopenia during the phase 3 clinical trial program. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:546–53. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25444.

- Boccia R, Cooper N, Ghanima W, Boxer MA, Hill Q, Sholzberg M, Tarantino MD, Todd LK, Tong S, Bussel JB, et al. Fostamatinib is an effective second-line therapy in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(6):933–8. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16959.

- Choi PY, Merriman E, Bennett A, Enjeti AK, Tan CW, Goncalves I, Hsu D, Bird R. Consensus guidelines for the management of adult immune thrombocytopenia in Australia and New Zealand. Med J Aust. 2022;216(1):43–52. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51284.

- Kashiwagi H, Kuwana M, Hato T, Takafuta T, Fujimura K, Kurata Y, Murata M, Tomiyama Y. Committee for the revision of “reference guide for management of adult ITP” blood coagulation abnormalities research team, research on rare and intractable disease supported by health, labour and welfare science research grants. Reference guide for management of adult immune thrombocytopenia in Japan: 2019 revision. Int J Hematol. 2020;111(3):329–51. doi: 10.1007/s12185-019-02790-z.

- Neunert C, Terrell DR, Arnold DM, Buchanan G, Cines DB, Cooper N, Cuker A, Despotovic JM, George JN, Grace RF, et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Advances. 2019;3(23):3829–66. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000966.

- Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01567.x.

- Terrell DR, Neunert CE, Cooper N, Heitink-Pollé KM, Kruse C, Imbach P, Kühne T, Ghanima W. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP): Current limitations in patient management. Med (Kaunas). 2020;56(12):667. doi: 10.3390/medicina56120667.

- Carpenedo M, Baldacci E, Baratè C, Borchiellini A, Buccisano F, Calvaruso G, Chiurazzi F, Fattizzo B, Giuffrida G, Rossi E, et al. Second-line administration of thrombopoietin receptor agonists in immune thrombocytopenia: Italian Delphi-based consensus recommendations. Ther Adv Hematol. 2021;12:20406207211048360. doi: 10.1177/20406207211048361.

- Mahevas M, Michel M, Godeau B. How we manage immune thrombocytopenia in the elderly. Br J Haematol. 2016;173(6):844–56. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14067.

- Eslick R, McLintock C. Managing ITP and thrombocytopenia in pregnancy. Platelets. 2020;31(3):300–6. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2019.1640870.

- Liebman HA. Recognizing and treating secondary immune thrombocytopenic purpura associated with lymphoproliferative disorders. Semin Hematol. 2009;46(1 Suppl 2):S33–6. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.12.004.

- Bussel JB. Therapeutic approaches to secondary immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Semin Hematol. 2009;46(1 Suppl 2):S44–58. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.12.003.

- Zhou Z, Yang L, Chen Z, Chen X, Guo Y, Wang X, Dong X, Wang T, Zhang L, Qiu Z, et al. Health-related quality of life measured by the short form 36 in immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a cross-sectional survey in China. Eur J Haematol. 2007;78(6):518–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00844.x.

- McMillan R, Bussel JB, George JN, Lalla D, Nichol JL. Self-reported health-related quality of life in adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:150–4.8. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20992.

- Leven E, Miller A, Boulad N, Haider A, Bussel JB. Successful discontinuation of eltrombopag treatment in patients with chronic ITP. Blood. 2012;120(21):1085. doi: 10.1182/blood.V120.21.1085.1085.

- Bussel JB, Mahmud SN, Brigstocke SL, Torneten SM. Tapering eltrombopag in patients with chronic ITP: how successful is this and in whom does it work? Blood. 2015;126(23):1054. doi: 10.1182/blood.V126.23.1054.1054.

- Zaja F, Carpenedo M, Baratè C, Borchiellini A, Chiurazzi F, Finazzi G, Lucchesi A, Palandri F, Ricco A, Santoro C, et al. Tapering and discontinuation of thrombopoietin receptor agonists in immune thrombocytopenia: real-world recommendations. Blood Rev. 2020 May;41:100647. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2019.100647.

- Cooper N, Hill QA, Grainger J, Westwood JP, Bradbury C, Provan D, Thachil J, Ramscar N, Roy A. Tapering and discontinuation of thrombopoietin receptor agonist therapy in patients with immune thrombocytopenia: results from a modified delphi panel. Acta Haematol. 2021;144(4):418–26. doi: 10.1159/000510676.