Abstract

Although the concepts of relational and contractual governance in inter-organizational relationships have attracted academic and practitioner interest over the last decades, to date there have been limited comprehensive and systematic efforts to review, analyse and synthesise extant literature. We review and analyse 1,415 publications identified from a wide range of management disciplines and journals from 1990 to 2018. We deploy bibliographic and content analyses to offer a comprehensive literature analyses and synthesis and subsequently develop and position a multidimensional framework of exchange governance. The proposed framework covers existing conceptualisations of exchange governance and its diverse mechanisms, environmental dimensions influencing the use of exchange governance mechanisms and performance implications. We uncover areas that are currently under-studied and draw out fruitful future research avenues.

1. Introduction

The development and management of inter-organizational relationships (IORs) has been extensively researched within organization and management studies (Das and Teng Citation1998; Vanneste and Puranam Citation2010). Organizations forming these relationships could be public, private, industrial, for-profit or non-for profit in nature. IORs are observable at several levels such as dyadic to ‘multiplicitous’, consisting of networks of many organizations (Cropper et al. Citation2008). The study of IORs focuses on the characteristics and patterns, origins, rationales and consequences of such relationships (Cropper et al. Citation2008).

Inter-organizational governance mechanisms refer to the formal and informal rules of exchange between partners (North Citation1990; Vandaele et al. Citation2007). The deployment of these governance mechanisms to nurture and manage IORs is an important phenomenon in the sense that it affects not only the performance of focal firms but also that of their suppliers, customers and business partners (e.g. Carson, Madhok, and Wu Citation2006; Klein-Woolthuis, Hillebrand, and Nooteboom Citation2005). Therefore, IOR governance mechanisms are especially important to operations and supply management (OSM) research (e.g. Cao and Lumineau Citation2015; Hartmann et al. Citation2014). Prior literature has distinguished between two main types of governance mechanisms in IORs: contractual and relational governance mechanisms (Griffith and Myers Citation2005; Rousseau et al. Citation1998). Contractual governance is manifested in ‘explicit, formal, and usually written contracts’ (Vandaele et al. Citation2007, p. 240) that are mostly very detailed and legally binding agreements, and which specify roles and obligations of contracting parties (Lyons and Mehta Citation1997). Relational governance refers to more emergent governance mechanisms that are manifested in socially derived ‘arrangements’ and that are more informal in comparison to contractual governance (Vandaele et al. Citation2007).

Advances in how inter-organizational governance is conceptualised and operationalised are reflected in the growing number of academic literature published on the topic (e.g. Poppo and Zenger Citation2002; Lumineau Citation2017; Zheng, Roehrich, and Lewis Citation2008). Although such literature provides important insights, it also suffers from: (i) a fragmentation among several research streams from economics, organization studies, strategic management, law, and operations management spanning different levels of analysis (see Schepker et al. Citation2014); (ii) a lack of conceptual clarity of the notion and interplay (i.e. substitute vs. complementarity discussions) of inter-organizational governance mechanisms, antecedents that influence the type of governance mechanisms used and subsequent impact on relationship performance (see Cao and Lumineau Citation2015), and (iii) limited effort to synthesize prior research by cutting across disciplines and various key themes. Moreover, prior studies have mainly focused on governance mechanisms in horizontal relationships such as alliances and further attention is needed to explore exchange governance in, for instance, buyer-supplier relationships (Lumineau Citation2017; Roehrich and Lewis, Citation2014; Schilke and Lumineau Citation2018). We reason that prior studies’ more context-specific treatment inhibits integration and holistic evaluation of the exchange governance literature. For instance, despite offering valuable insights, Vandaele et al. (Citation2007) focus mainly on business services exchanges. Similarly, the study by Cao and Lumineau (Citation2015) offers insights via a meta-analysis of IORs but does not deploy a comprehensive literature review spanning academic disciplines and industry contexts to take stock of and synthesise the body of knowledge (Tavares Thomé, Scavarda, and Scavarda Citation2016).

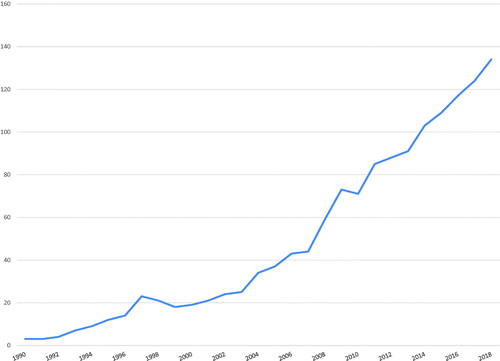

This study complements extant research efforts in analysing and synthesising prior governance studies and positions a research agenda and framework for future research avenues, posing the following research questions: (i) What is the current state of inter-organizational governance in management research? and (ii) What are the emerging themes of interest for management research? Such a comprehensive review is highly relevant in order to advance our understanding of governance mechanisms as well as how they have been conceptualised and approached, both theoretically and empirically, across disciplines. Our research demonstrates a surge of interest in governance literature over more than two decades, with the vast majority (over 80%) of peer-reviewed journal papers published over the last decade (see ). The recent exponential growth in the literature suggests that the time is ripe to take stock of where inter-organizational governance efforts are.

Our study draws together analyses of 1,415 published governance articles, offering a comprehensive review of key research streams in extant governance mechanisms studies. Moreover, we provide a better understanding of how contractual and relational governance mechanisms have been defined and conceptualised. Second, we position a conceptual framework synthesising multiple theoretical perspectives and associated constructs in terms of governance determinants, mechanisms and performance outcomes. The developed framework contributes to existing research by serving as a conceptual map of the field. It provides input for evaluating where the literature currently is and pointing out promising avenues for future research.

The paper is structured as follows. It commences by outlining the comprehensive review method adopted. The article is then split into two parts. Part one maps the field and uses bibliographic and content analyses to offer a range of analyses and examine changes in exchange governance research. Part two offers a synthesis and comprehensive analysis of the emerging themes, linking exchange governance mechanisms, antecedents and performance implications. This section also draws out theoretical gaps and positions a multi-dimensional framework to bring together dispersed research on exchange governance. Using this framework, current literature limitations are pointed out and future research avenues are discussed.

2. Comprehensive review approach

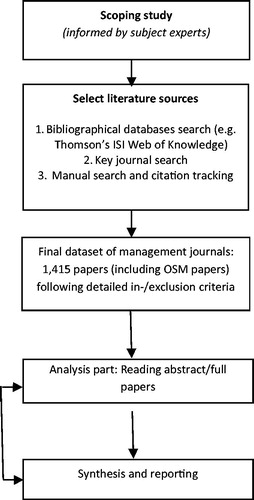

With the increasing attention towards studying contractual and relational governance mechanisms in management studies and indeed in OSM, we offer a comprehensive literature analysis and synthesis of prior research on governance mechanisms (Lumineau Citation2017; Roehrich and Lewis Citation2014). Literature reviews are vital in establishing key themes and relationships amongst the concepts under study, thus driving more structured future research efforts (Burgess, Singh, and Koroglu Citation2006). Our search strategy aimed at mitigating bias and establishing a comprehensive search and analysis framework by incorporating database search, cross-referencing between authors and applying agreed on inclusion and exclusion criteria (Durach, Kembro, and Wieland Citation2017; Rashman, Withers, and Hartley Citation2009). We adopted an iterative review procedure (), commencing with an initial scoping study to set the boundaries for our study (Tavares Thomé, Scavarda, and Scavarda Citation2016) and identifying seminal exchange governance papers (Heide and John Citation1992; Poppo and Zenger Citation2002). This initial analysis helped to establish a focus for subsequent analysis stages by, for instance, specifying the search period and terms. In addition, seven scholarly subject experts were interviewed to further improve the search strategy and search terms.

Figure 2. Summary of comprehensive review process (adapted from Rashman, Withers, and Hartley Citation2009, p. 5).

To identify articles for this review study, the main database ISI Web of Knowledge was searched using terms such as relational governance, contractual governance, relationship governance mechanism*, governance interplay, inter-organi*ation* trust contract*, inter-personal trust contract*, inter-organi?ation* contract*, contract network*, inter-organi?ation* trust* and trust governance. While ISI Web of Knowledge is considered the most comprehensive database for scholarly work, we also consulted other databases, such as Emerald, Business Source Premier, Science Direct and Ingenta to achieve even better coverage of journals.

outlines the approach used to identify articles published during the period 1990–2018. While only a relatively small number of papers was published before 1990, recent years show an immense increase of interest in management research on exchange governance (e.g. Klein-Woolthuis, Hillebrand, and Nooteboom Citation2005; Kreye, Roehrich, and Lewis Citation2015; Lumineau Citation2017; Poppo and Zenger Citation2002). As such, papers published between 1990 and 2018 offered a sufficient timespan to enable a comprehensive and meaningful analysis. In order to obtain a more comprehensive overview of extant governance research, we searched for management journals across areas including, but not limited to, marketing, strategy, organization studies, international business as well as OSM. We intentionally used broad search definitions as the concept of inter-organizational governance is used and published in a broad range of journals. Three researchers independently judged the identified set of papers based on inclusion criteria, being that identified papers should be from scholarly, peer-reviewed publications and of conceptual and/or empirical nature. For the selection of articles into the final dataset, the researchers aimed for 100% agreement. When this level of agreement was not reached during the initial reading of abstracts, all researchers read and discussed papers in detail and made a joint decision on the inclusion/exclusion of the article into the final dataset.

The search led to the identification of 1,415 publications forming the dataset. This dataset included OSM articles. We specifically zoomed in on OSM articles with an aim to detect publication patterns. This exercise did not lead to drastically diverging results and we decided to present publication patterns for the whole dataset. In order to produce new insights, data analysis and synthesis can be seen as primary value-added results of this comprehensive literature review (Crossan and Apaydin Citation2010). Analysis and synthesis of identified papers consist of two parts: (i) examining patterns of publications over the analysed period and (ii) presenting fruitful future research avenues drawn from the identification of thematic management research issues.

3. Part I: publication patterns

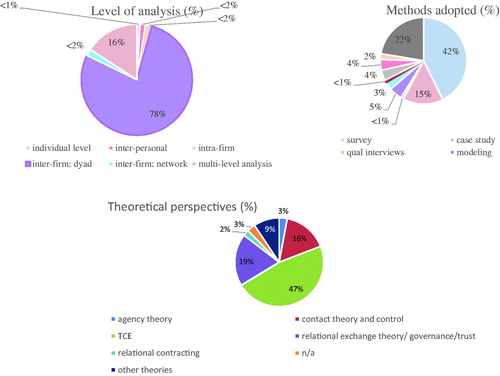

This section critically reflects on the analyses of the identified dataset. It offers key observations that are worth highlighting at this stage before moving on to discuss emerging research themes. summarises the key disciplines, levels of analysis, methodological approaches and theoretical perspectives adopted to date. Inter-organizational governance has been subject to scrutiny by researchers from diverse backgrounds, thus reflecting the inter-disciplinary nature of the phenomenon which presents overlapping economic, social, legal and political implications (North Citation1990).

Our review revealed that very few studies (<2%, see ) have focused on network governance. Therefore, for the purposes of conducting the review, we restricted our analysis to the dyadic level of analysis. A reason for the dyadic focus currently dominating in inter-organizational governance research (78%) might be the fact that researchers often face challenges in conducting research and collecting data at a network level (see Easton Citation2010). Relative to the importance of relational governance mechanisms at an inter-personal and inter-organizational level, only a few studies employ multiple levels of analysis (16%; e.g. Kamann et al. Citation2006; Zheng, Roehrich, and Lewis Citation2008, and very few studies in OSM). Prior studies have furthermore mainly focused on governance mechanisms in developed countries, with the USA and UK accounting for over 50% of all published papers. China is becoming increasingly interesting for governance researchers with a current share of 9.5%. Although relatively limited, the number of publications that use data across countries has started to grow in recent years (<10%; see for example Yang, Wacker, and Sheu Citation2012).

Second, there is evidence of a variation of governance research methodologies in the published literature. Survey research tends to be the primary data collection method (42%). Surveys have particularly been dominant in studies into the performance implications of contractual and relational governance (e.g. Sumo et al. Citation2016). The use of case study methodologies is more limited (15%). A few studies (4%) adopt mixed-method designs, such as by combining questionnaires with interviews (notable examples are Blumberg Citation2001; Gulati and Nickerson Citation2008) or conducting experiments (e.g. Tangpong, Hung, and Ro Citation2010). Surprisingly, despite the long-term nature of IORs and the importance to investigate exchange governance over time, there is only limited evidence of publications adopting a longitudinal or processual research perspective (e.g. Roehrich and Caldwell Citation2012).

Third, certain theoretical perspectives seem to be favoured in the analysis of exchange governance. In particular, transaction cost economics (TCE) appears to be the dominant theoretical frame of reference (e.g. Dyer Citation1997). Social exchange and management control theories are other conceptual lenses frequently adopted in extant literature (e.g. Faems et al. Citation2008; Jap and Ganesan Citation2000). Given the complexity of the phenomena under investigation, several studies adopt multiple theoretical perspectives to serve their purposes (e.g. Mellewigt, Madhok, and Weibel Citation2007). For example, extant research studies investigating the substitution and complementarity of relational and contractual governance mechanisms combine TCE with theories of social and relational exchange (e.g. Liu, Luo, and Liu Citation2009; Poppo and Zenger Citation2002; Sumo et al. Citation2016).

Surprisingly, well-established theoretical perspectives such as agency theory has not been much in focus, accounting for only around 2% of investigated management papers (see for instance Lazzarini, Miller, and Zenger Citation2004). Similarly, other theories such as resource-based view and dynamic capabilities perspectives appear to be under-utilised too. More recently, the organizational information processing theory (OIPT) has experienced a resurgence in inter-firm governance studies (e.g. Lumineau Citation2017). For example, studies have found that contracts designed with an emphasis on control functions would orient the need for processing information pertaining to the monitoring of partners’ activities (Provan and Skinner Citation1989). In contrast, contracts emphasising the coordination function would facilitate the flow and exchange of information between partners (Lumineau and Henderson Citation2012; Malhotra and Lumineau Citation2011; Reuer and Ariño Citation2007).

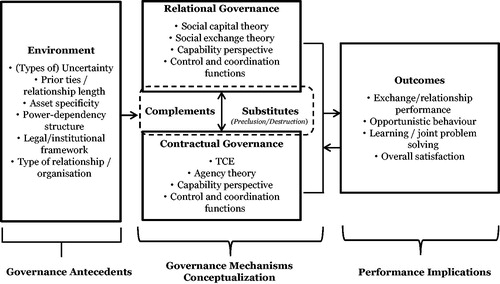

Our review has produced a clearer picture of growing but fragmented governance research. Based on the comprehensive analysis of the dataset, we depict a multidimensional framework of inter-organizational governance. summarises key concepts (environment, relational and contractual governance interplay as well as performance outcomes) derived from our analysis. The arrows flowing from outcomes back to governance mechanisms suggest that actual performance outcomes in IORs (e.g. opportunism or poor exchange or relationship performance) may trigger adaptations in contractual and/or relational governance mechanisms (e.g. Selviaridis and Spring Citation2018). This figure forms the basis for the synthesis efforts presented in subsequent sections.

4. Part II: synthesis and emerging research themes

This section provides a critical reflection and synthesis of inter-organizational governance research emerging from the analysis part, paving the way for future research avenues.

4.1. Conceptualization and evolution of governance mechanisms interplay

Inter-organizational governance mechanisms refer to the formal and informal rules of exchange between partners (North Citation1990; Vandaele et al. Citation2007; Poppo and Zenger Citation2002). Previous studies have distinguished between two types of governance mechanisms regarding IORs: economic strategies such as contracts, and relational governance which is derived from trust and social norms (Griffith and Myers Citation2005; Vandaele et al. Citation2007). Social norms are considered as behavioural guidelines that enforce social obligation in the relationship (Caldwell, Roehrich, and George Citation2017; Cannon, Achrol, and Gundlach Citation2000; Heide Citation1994). While in this paper our focus is on formal contracts, we acknowledge that there are several other definitions in the literature referring to ‘informal’ or ‘normative’ contracts, whose main characteristic is that they are not written and legally enforceable. In addition, the literature refers to relational contracts as a third form of contracting between classical and neoclassical contracting (Williamson Citation1985), which entails flexible and open-ended contractual specifications and provisions to allow for adaptation in relationships given the inherently incomplete nature of formal contracts (see MacNeil Citation1980). Relational contracts are a type of formal contracts in the sense that they are written and legally enforceable, and therefore are within the scope of our analysis.

While research on exchange governance has steadily increased in recent years, our analysis also shows a lack of common conceptualisation and operationalisation. The relationship between governance antecedents and governance mechanisms has been a subject of debate in the literature (Cao and Lumineau Citation2015; Poppo and Zenger Citation2002). Early studies adopted a TCE perspective and tried to explore the relationship between the transaction characteristics, for example, uncertainty and asset specificity as well as contract design (Schepker et al. Citation2014). While transactions characterized by lower uncertainty and asset specificity do not require detailed contracts, partners design detailed contracts, with safeguarding clauses while conducting uncertain, asset-specific transactions (Reuer and Ariño Citation2007). Real options theory provides an alternative perspective to the relationship between uncertainty and contract design. While the TCE perspective implies that detailed contracts should be designed in the face of uncertainty, a real options perspective calls for more flexible contracts (Chi Citation2000). This flexibility allows partners to refrain from making irreversible investments. Furthermore, since the transaction characteristics, as well as familiarity between partners, change over time, flexible contracts allow for modification in response to the changing environment (Schepker et al. Citation2014).

Similarly, scholars have argued that the development of trust and norms between organizations appear to be less driven by the transaction characteristics and are more of a function of idiosyncratic capabilities of organizations (Dyer and Singh Citation1998; Madhok and Tallman Citation1998). Furthermore, the relationship between contractual and relational governance mechanisms appears to be even more tenuous (e.g. Cao and Lumineau Citation2015). Early studies focused on the issue argued that contracts have a damaging effect on relational governance. The core argument of this stream of literature was that the use of detailed contracts signals a lack of trust, which could damage the prospect of relational governance (Ghoshal and Moran Citation1996; Heide and John Citation1992; Macaulay Citation1963). Furthermore, detailed contracts create an environment of vigilance, preventing the development of trust through the reduction of opportunities for a spontaneous display of good intentions (Frey and Jegen Citation2001; Malhotra Citation2009). Another stream of literature has argued that relational norms, such as trust, make contracts redundant, as trust can govern relationships by itself (Das and Teng Citation2001; Gulati Citation1995). In other words, in a relationship characterized by long-term trust, organizations would choose to employ more informal modes of governance (Gulati and Nickerson Citation2008).

Over time, with the conceptual work by Das and Teng (Citation1998) and the seminal study by Poppo and Zenger (Citation2002), scholars moved towards the argument that contractual and relational governance mechanisms complement each other. This means that contracts can enhance trust while trust, in turn, can trigger ‘learning to contract’ effects whereby contracting parties learn to jointly design more effective contracts and to collaborate (Mayer and Argyres Citation2004). Contracts aid in the development of trust through the reduction of information asymmetry between both parties (Bastl et al. Citation2012; Liu, Luo, and Liu Citation2009). Moreover, as organizations enter into long-term relationships, they become more familiar with each other (Gulati Citation1995) and learn to specify more detailed contracts (Poppo and Zenger Citation2002; Ryall and Sampson Citation2009).

Although the debate of a substitution and complementary logic is ongoing in the literature, more recent works have provided some clarification on this divide (Cao and Lumineau Citation2015; Howard et al. Citation2019; Lumineau Citation2017). Scholars have drawn a distinction between the control and coordination function of formal contracts and argued that these two functions interplay differently with relational modes of governance. The control function refers to safeguarding parties against potential opportunism, whereas the coordination function emphasizes delineation of roles/responsibilities, communication and information sharing and joint problem solving (Kapsali, Roehrich, and Akhtar Citation2019; Schepker et al. Citation2014). While the control function signals a lack of trust and negatively influences goodwill trust, the coordination function of contracts creates a common knowledge structure, which aids in the development of competence trust (Malhotra and Lumineau Citation2011; Weber and Mayer Citation2011).

More recent studies on inter-organizational governance have moved towards exploring contractual governance in further detail. For example, the literature shifted its focus towards exploring issues pertaining to contract design (Bercovitz and Tyler Citation2014; Dean, Griffith, and Calantone Citation2016; Ozmel et al. Citation2017), the content of the contract (Duplat and Lumineau Citation2016; Schilke and Lumineau Citation2018) and the link between contracting and a range of performance outcomes such as supply chain alignment (Selviaridis and Spring Citation2018), new product performance (Dean, Griffith, and Calantone Citation2016), exchange performance (Poppo and Zhou Citation2014) and dispute resolution (Lumineau and Malhotra Citation2011).

Our comprehensive review led to the identification of key concepts and mechanisms pertaining to inter-organizational governance (see ). These concepts are presented in along with key gaps in our knowledge of these concepts. In accordance with Lumineau and Oliveira (Citation2018), we framed these knowledge gaps around key ‘blind spots’ in research on inter-organizational governance. The subsequent sections explore key gaps in further detail, thus supporting the development of fruitful future research avenues.

Table 1. Key concepts and knowledge gaps for inter-organizational governance research.

4.2. Advancing inter-organizational governance research

The following sections position key knowledge gaps and blind spots and discuss opportunities for future research efforts to advance inter-organizational governance research. The intention here is not to elaborate upon all blind spots identified in , but rather to offer some more specific insights and discussions with regard to future directions of inter-organizational governance research, considering also suitable theories and research designs.

4.2.1. Longitudinal, multi-level and dual-party research perspectives

Taking into consideration the fact that relationships usually consist of a large number of interfaces between individuals and organizations (e.g. between individuals, teams and organizations), we contend that they are not accurately represented as a single entity (focus on one party only), focusing on one level of analysis only or in a static picture (Lumineau and Oliveira Citation2018). There has been limited attention on a longitudinal understanding of how governance mechanisms evolve over time in IORs (notable exemption is, for instance, the study by Zheng, Roehrich, and Lewis Citation2008). Parties in long-term IORs will periodically alter and adjust governance mechanisms and accompanying safeguards, when deemed necessary and depending on the relative weight given to governance mechanisms at specific points in time (Halldórsson and Skjøtt-Larsen Citation2006). For instance, Selviaridis and Spring’s (Citation2010) empirical study demonstrates how parties shift their emphasis among the normative frames of the ‘contract’, the ‘deal’ and the ‘relationship’ (Collins Citation1999) as critical events (e.g. buyer fail to pay the supplier in time) in the relationship unfold. In cases of such events, a reference to the ‘relationship’ may be more appropriate than contract enforcement when relationship continuity and long-term financial benefits are sought over short-term economic gains.

A longitudinal perspective allows capturing characteristics of the exchange parties and the relationship at given points in time and in this sense contributes to our understanding of key antecedents of governance mechanisms (e.g. Das and Teng Citation2002). In line with the call for OSM scholars for increasing attention to a longitudinal view of exchange governance mechanisms and their interplay (Cao and Lumineau Citation2015; Zheng, Roehrich, and Lewis Citation2008), longitudinal field research is deemed appropriate for collecting and analysing data on exchange relationships context, characteristics and critical events (Langley Citation1999; Pettigrew Citation1990). Such data help in uncovering nuances in the deployment of trust and formal controls and capturing changes associated with substitution and/or complementarity effects. Moreover, a dual-party perspective is vital to move away from extrapolating from observations of a single party in an IOR (Lumineau and Oliveira Citation2018). Understanding the differences (and possible asymmetries) between parties in a relationship is key to future research exploring governance mechanisms interplay. A study by Son, Kocabasoglu-Hillmer, and Roden (Citation2016), for example, revealed that dissonance in the buyer’s and supplier’s perceptions of the visions and collective goals for the relationship result in differential strategic and operational performance outcomes for both parties. Adopting a dual perspective, therefore, becomes particularly important for OSM scholars. Further research should also consider the impact of various levels of analysis, including, but not limited to, individual and team and their impact on governance mechanisms. For instance, future research should explore how various functions of governance mechanisms are enacted by individuals or teams in an IOR, thereby refining the governance mechanisms interplay debate.

4.2.2. Theoretical lenses

Research on governance mechanisms is likely to benefit from an expanded theoretical frame of reference and infusing in a more systematic fashion theoretical lenses such as agency theory and capability perspective.

Agency theory can help delineate the circumstances under which the interplay and potential complementarity effects between trust and contractual controls occur. Contractual controls do not necessarily preclude the development of trust. The issue is rather what types of control are employed in exchange relationships (Strätling, Wijbenga, and Dietz Citation2012). As Das and Teng (Citation1998) suggested, trust and control can complement each other, but the degree to which they do depends on the type (namely, goal setting, structural specifications and cultural blending) and level of control. Such controls are both formal and informal, where informal controls closely associated with relational governance mechanisms. However, we need to understand better the effects of different types of contractual controls on trust (Strätling, Wijbenga, and Dietz Citation2012). Agency theory is a theoretical lens that may drive such research endeavours. In particular, its distinction between outcome- and behaviour-based contracts (Eisenhardt Citation1989) is theoretically useful in the sense that it disentangles the effects of process/behaviour monitoring from outcome controls and associated incentive systems.

As the review demonstrated, the existing governance literature appears to largely sidestep how organizations can develop competence in managing formal contracts and leveraging trust, social capital and related relational governance mechanisms (Mayer and Argyres Citation2004). Indeed, literature within organization studies and strategic management has stressed the importance of contracting and relational capabilities for performance attainment (Kreye, Roehrich, and Lewis Citation2015). For instance, Argyres and Mayer (Citation2007) and Lumineau and Henderson (Citation2012) argue that contract design capabilities might be a source of competitive advantage for organizations. These capabilities entail learning about the required level of extensiveness and sophistication of contractual provisions in response to exchange attributes as well as potential contingencies and hazards. Some existing studies stress the notion of contracting capabilities which extend beyond contract design to include know-how regarding the outsourcing decision, contract monitoring and management (Yang, Hsieh, and Li Citation2009). In the same vein, developing appropriated organizational structures and processes to articulate, codify and share expertise regarding the management of relations with exchange partners can help improve performance (Kale, Dyer, and Singh Citation2002; Kale and Singh Citation2007; Lorenzoni and Lipparini Citation1999). Future empirical research on exchange governance should extend prior studies to examine how governance capabilities develop and how they impact performance. Particularly for OSM scholars, studying long-term buyer-supplier relationships, learning theory could provide a useful lens to aid the understanding of how buyers and suppliers develop the capability to design, use and renegotiate the contracts overtime (Cao and Lumineau Citation2015). Future research could also examine how asymmetries in counterparts’ contracting and relational capabilities impact on firm and relationship performance (see ).

4.2.3. The manifold facets of trust

Despite a myriad of trust definitions in extant management literature, the concept is often positioned including two key elements: positive expectations regarding the actions and/or intentions of partners and voluntary vulnerability towards a partner (Rousseau et al. Citation1998). Whilst some research studies have distinguished between various types of trust, such as intentional and competence trust (e.g. Klein-Woolthuis, Hillebrand, and Nooteboom Citation2005), limited research has been undertaken regarding the distinct levels of inter-personal and inter-organizational trust and their interplay with contractual governance mechanisms. A fundamental advantage of conceptualising trust in these two dimensions is that by taking this perspective, the inherently individual level of the phenomenon can be extended to the organizational level of analysis. That is, previous studies on the relationship between both governance mechanisms deployed an overarching and rather general concept of trust, thereby failing to distinguish between different types and dimensions inherent in IORs. Inter-personal trust is referred to as ‘the extent of a boundary-spanning agent’s trust in her counterpart in the partner organi[s]ation’ (Zaheer, McEvily, and Perrone Citation1998, 142). Moreover, in an exchange relationship, the role of boundary-spanning individuals, as they build up strong inter-personal ties, has an important influence on IORs. Boundary-spanning individuals belonging to an organization are characterized by having a higher involvement and interaction in the IOR than their counterparts (Friedman and Podolny Citation1992). Trust is built among such individuals from the contracting organizations and is based upon close interactions and personal ties (Kale, Singh, and Perlmutter Citation2000).

Trust may also exist between organizations at the inter-organizational level which has been defined as ‘the extent of trust placed in the partner organi[s]ation by the members of a focal organi[s]ation’ (Zaheer, McEvily, and Perrone Citation1998, 142). This form of trust reflects an organization’s expectations that the partner organization will not act opportunistically (Bradach and Eccles Citation1989). One premise of inter-organizational trust exists where there is predictability of the partnering organization’s behaviour towards a vulnerable focal organization and this helps to develop greater confidence in the relationship (Gulati and Nickerson Citation2008).

Apart from the level of trust, different types of trust should be taken into consideration, moving away from offering a unified trust dimension and neglecting the multi-faceted concept under investigation. The concept of trust is closely related to social capital theory. In this context, Tsai and Ghoshal (Citation1998) have found that the cognitive and structural dimensions of social capital impact on trust, which represents an important aspect of the relational dimension of social capital. Similarly, the seminal work by Sako (Citation1992) distinguishes between various degrees of predictability in behaviour, thus leading to three types of trust: goodwill, competence and contractual. Building on this, Malhotra and Lumineau (Citation2011) suggest that while control provisions included in formal contracts reduce goodwill trust, the coordination function supports the development of competence trust and increases the likelihood of resolving inter-firm conflicts quickly. For example, the type of trust developed over time could inform the level of contractual completeness (Poppo and Zenger Citation2002). For OSM scholars, studying the evolution of trust (e.g. from contractual to competence to goodwill) and its ensuing effect on performance represents a critical area of research. For instance, shadows of the past and future may help recover trust breakdowns and ensures continuity of buyer-supplier relationship (Poppo, Zhou, and Ryu Citation2008; Wang, Craighead, and Li Citation2014). This calls for further research to address this knowledge gap and advance our understanding of the role and impact of inter-personal and inter-organizational trust on contractual governance mechanisms.

4.2.4. Relationship environment and governance antecedents

Our analysis and synthesis resulted in adding environmental dimensions influencing the use of exchange governance mechanisms (see ), such as asset specificity and the creation of associated partner-specific dependencies (e.g. Cannon, Achrol, and Gundlach Citation2000; Vandaele et al. Citation2007); the role of power asymmetry (e.g. Bucklin and Sengupta Citation1993) and power/dependence (see Lusch and Brown Citation1996) in relation to governance choices and conflict resolution (Malhotra and Lumineau Citation2011); the wider institutional environment and legal system in which contracting parties operate (e.g. Deakin, Lane, and Wilkinson Citation1997) and the type of industry, sector and relationship (e.g. public-private partnerships; Zheng, Roehrich, and Lewis Citation2008).

Two of these antecedents seem particularly fruitful areas for further enquiry: uncertainty and prior ties. identifies some specific blind spots and opportunities for future research in relation to these two antecedents. Uncertainty and its various types (environmental, market and behavioural; see Geyskens, Steenkamp, and Kumar Citation2006) feature strongly in the governance literature as key antecedents to governance choice. For instance, Podonly (Citation1994) finds that high market uncertainty results in organizations engaging in exchanges with those of similar status and with whom they have transacted in the past. Social norms are predominant in such instances. In a similar vein, Carson, Madhok, and Wu (Citation2006) refine the uncertainty concept and distinguish between volatility and ambiguity as antecedents of the deployment of relational contracts; in particular, relational contracts appear to be robust to environmental volatility but not to ambiguity, whereas formal contracts perform better in cases of highly ambiguous, but less volatile, transaction environments (Carson, Madhok, and Wu Citation2006). The existing literature often stresses the effect of particularly environmental and behavioural uncertainty, but such a focus underplays the role of risk attitudes of buyers and suppliers in contract design (Eisenhardt Citation1989). In addition to future research opportunities identified in , we suggest that agency theory could be useful to uncover the role of risk attitudes of exchange partners in designing contractual governance mechanisms. Attitudes towards risk may result from internal (firm-level) factors such as organizational culture and mind-sets of individual (senior) managers, rather than external (environmental) factors. An agency theory framework allows studying the impact on risk aversion and/or risk-taking behaviour on exchange governance.

Scholars from different fields recognize the importance of repeated exchanges in IORs. Economists emphasize the calculative nature of relational governance in the present when expectations of future exchanges prompt current cooperation (Baker, Gibbons, and Murphy Citation2002). That is, in contrast to sociologists who consider the ‘trustworthy status’ as conditional upon the benefits derived from the trustworthy status (e.g. repeated business) over the status of self-interest (Klein Citation1996). This logic is common to game theory, where opportunistic behaviour in the present is contrasted with the benefits of cooperative behaviour in the future. On the other hand, the sociological perspective emphasizes the importance of prior exchanges in forming social norms and ties that emerge in subsequent exchanges (Uzzi Citation1997). While we concur with existing research that the history of IORs can have a bearing on the development of governance mechanisms, we argue that there need to be more systematic efforts to employ a longitudinal perspective to study the role of prior ties in exchange governance (see also Cao and Lumineau Citation2015; Selviaridis and Spring Citation2018). This is because a longitudinal view emphasizes agency (i.e. what individuals/organizations do), temporal interconnectedness and the sequence of critical events which describes how things change over time (Pettigrew Citation1997; Van de Ven Citation1992). Studying exchanges as continuous processes and employing micro-level analysis of actors (both firms and managers within these firms) and events during the exchange (Pettigrew Citation1997) help in better understanding the role of prior interactions and how they influence the interplay of trust and formal controls (e.g. Huemer, Boström, and Felzensztein Citation2009; Zheng, Roehrich, and Lewis Citation2008). This is important if governance scholars wish to capture the co-evolution of trust and contracts over repeated exchanges (Faems et al. Citation2008; Vanneste and Puranam Citation2010). suggests specific avenues for future research in relation to the above aspects.

In addition to the antecedents mentioned above, OSM scholars have called for exploration of the role of power-dependence in the relationship and its impact on the inclusion or exclusion of different types of contract clauses (Selviaridis Citation2016; Selviaridis and Spring Citation2018). Particularly, the bargaining power afforded to the buyer or supplier through its position in the wider supply chain/network could significantly shape the contract (Argyres and Bercovitz Citation2015). This further links to the call for more research on the overall structure of a multi-tier supply network and its influence on governance mechanisms (Mena, Humphries, and Choi Citation2013; Zhang, Lawrence, and Anderson Citation2015). For instance, a closed-type structure of supply network leads to tighter self-enforcing agreements and stronger informal social controls (Mena, Humphries, and Choi Citation2013).

4.2.5. Outcomes

Recent prior literature established that contractual and relational governance mechanisms act as complements (Poppo and Zenger Citation2002; Cao and Lumineau Citation2015). Thus, there is an increasing emphasis on exploring the performance implications of the governance interplay. Prior work focused on issues such as reducing opportunism (Mellewigt, Madhok, and Weibel Citation2007; Zhou and Xu Citation2012), buyer’s satisfaction (Poppo and Zenger Citation2002), relationship performance (Zaheer, McEvily, and Perrone Citation1998), facilitating joint problem solving (Mayer and Argyres, Citation2004) and information flow (Olsen et al. Citation2005). More recent studies have begun to widen their scope in terms of examining performance outcomes such as improving project performance (Caniëls, Gelderman, and Vermeulen Citation2012; Ning Citation2017), innovation performance (Arranz and de Arroyabe Citation2012; Carey, Lawson, and Krause Citation2011), negotiation strategy (Lumineau and Henderson Citation2012), plant performance (Wacker, Yang, and Sheu Citation2016), firm performance (Jayaraman et al. Citation2013) and alliance performance (Schilke and Lumineau Citation2018).

Studies exploring the link between governance and performance have generally adopted perceptual measures and conceptualized it as the buyer’s satisfaction with the exchange (for example, Poppo and Zenger Citation2002). This is because exchange performance is harder to specify and therefore data are difficult to obtain (Poppo and Zhou Citation2014). Some exceptions include Gulati and Nickerson (Citation2008) who combine perceptual measures with quasi-objective measures such as average part target ratio, average part price change ratio, average defect rate and improvements in average defect rate. However, most of the studies adopting more objective measures such as cost, quality and delivery consider mainly the buyer’s perception of supplier performance (Zaheer, McEvily, and Perrone Citation1998). Since OSM scholars have also traditionally relied on perceptual measures of performance (Ketokivi and Schroeder Citation2004), considering more objective measures of performance would be a particularly fruitful future research avenue.

In what follows, we focus on the two outcomes that appear in the majority of studies (over 75%): exchange performance and opportunism. identifies a number of specific suggestions for future research in these areas. Prior literature offers a mixed view with regard to the impact of governance mechanisms on exchange performance. For instance, Lusch and Brown (Citation1996) have drawn a distinction between normative and explicit contracts, suggesting that normative contracts can positively influence relational behaviour (e.g. flexibility and solidarity) and lead to better performance. Lee and Cavusgil (Citation2006) argue for the positive impact of trust on the stability of alliances as well as on effective knowledge transfer. Ferguson, Paulin, and Bergeron (Citation2005) found that norms of cooperation and trust predominate over contractual mechanisms in terms of how clients evaluate exchange performance. These and other governance studies to date mostly stress the safeguarding role of contracts and their impact in terms of opportunism reduction. Relatively little is known about the performance effects of coordination and adaptation contract functions (e.g. what contract clauses promoting coordination and adaptation are included in formal contracts and how do they impact exchange performance). Further research is needed to understand better the performance implications of coordination and adaptation-oriented formal contracts (Schepker et al. Citation2014; see ).

In relation to the above, we also need a better understanding of the impact of contracting capabilities on exchange performance (see ), as well as what types of contracting capabilities are particularly effective in developing the coordination and adaptation functions of contracts (Selviaridis Citation2016; Spring and Araujo Citation2014). A capability per spective to contracting has been stressed in some prior studies (e.g. Argyres and Mayers Citation2007; Lumineau, Fréchet, and Puthod Citation2011), but there is still limited evidence of whether ‘learning to contract’ effects performance and how the development of contracting capabilities impacts performance. Future research should adopt a longitudinal and dyadic perspective using dynamic capabilities theory to capture learning effects (Schepker et al. Citation2014) and their impacts in terms of incentive alignment and performance improvement in supply chains. For instance, studies could examine the process of how organizations learn to contract and more specifically, learn to control and coordinate in different contexts. Longitudinal, in-depth case studies are particularly useful in this endeavour in that they enable gaining access to rich sources of data such as evolution of contract documents (Mayer and Argyres Citation2004).

Opportunistic behaviour is determined by a wide spectrum of factors pertaining to economic incentives (e.g. asymmetric investments specific to the exchange and unequal distribution of benefits), cultural diversity and goal incompatibility as well as short alliance horizons and pressures for immediate performance results (Das and Rahman Citation2010; Lumineau Citation2017). Extant literature focuses on how different governance mechanisms (e.g. formal and informal controls) can be employed to mitigate opportunism and its different facets. For instance, Carson, Madhok, and Wu (Citation2006) stated that relational contracts reduce opportunism in cases of high volatility, but they are not sufficient in cases of high ambiguity, where formal contracts are found to be more robust. Lumineau and Quelin (Citation2012) suggest that different contract function emphasis (in terms of control and coordination provisions) are required to encounter strong and weak forms of opportunism. Such analysis also suggests that some mechanisms are more effective than others taking into account the relationship context and specific environmental conditions such as the sector, type of transaction and level of environmental uncertainty (Rivera-Santos and Rufin Citation2010; Rindfleisch et al. Citation2010).

Future research should, therefore, improve our understanding of the determinants and drivers of governance mechanism decisions ex-ante, with the aim of deterring opportunistic behaviours ex-post and agency theory may be helpful here. Neumann (Citation2010), for instance, submits that appropriability concerns, information asymmetry and bargaining power asymmetries instigate the deployment of detailed contracts ex-ante, which are then complemented by trust mechanisms. Given its focus on the determinants of contract choices other than asset specificity (e.g. task programmability and risk attitude of buyer/supplier), agency theory is promising for explaining the effects of contractual governance mechanisms in IORs. In addition, future research should seek to explore the effect of opportunism on the contractual governance-performance link, as well as how opportunistic behaviour may evolve over time depending on the dynamic interplay of contracts and relational governance (see ).

An additional outcome that has been highlighted in the literature more recently is learning and joint problem solving between contracting parties, and the interplay of learning and governance mechanisms (e.g. Mayer and Argyres Citation2004). A particularly interesting aspect stressed in the literature is the role of contract framing (Weber and Mayer Citation2011) and its connection to learning effects in IORs (Weber Citation2017). Future research should consider potential asymmetries between a buyer and a supplier in terms of learning effects. In addition, further research is needed to uncover how contracting parties learn to frame contractual provisions and how interpretations of (revisited) contract frames may impact the dynamics of trust and learning in inter-firm relationships (see ).

4.3. Limitations and further research

This study has its limitations, some of which will serve as a stimulus for future work. First, this study’s focus was to analyse and synthesise prior research into a multi-dimensional framework, not offering detailed theoretical propositions or hypotheses, which may be seen as the next step. Second, this review mainly deployed the ISI Web of Knowledge database. While aiming for comprehensive coverage by following rigorous, comprehensive review and synthesis procedures, the database selection and filtering processes may have omitted some relevant research such as conference papers. However, we remain confident that our comprehensive review has covered a wide range of management journal articles on the topic. Furthermore, even though only peer-reviewed articles were selected in the dataset, we cannot rule out the fact that quality levels of selected articles are the same. Future studies could improve upon these limitations by complimenting this comprehensive literature review with an assessment of the reliability and validity of results by focusing on management journals of similar standing (Hawker et al. Citation2002).

Third, deploying an analytical framework for such a multi-dimensional concept of exchange governance highlights some previously under-researched linkages while failing to capture others. Foremost, however, we feel the analytical framework helped to bound and integrate the various, dispersed research streams. We also acknowledge the caveat that our comprehensive review explicitly focuses on inter-organizational governance and its two core mechanisms, i.e. contractual and relational governance. Future studies should extend this work by reviewing the literature on governance more broadly, for example, network governance (Provan, Fish, and Sydow Citation2007; Provan and Kenis Citation2007) and structural decisions for governing transactions. As such, we hope the research agenda that we set will help advance the current body of knowledge on inter-organizational governance mechanisms in general and within the OSM research field in particular.

Due to the paucity of studies exploring governance, our comprehensive review has focused on the governance of IORs at the dyadic level. Our findings, however, point toward future research directions that are relevant for the governance of inter-organizational networks. Particularly, the governance of network-level relationships is fundamentally different from that of dyadic relationships. Das and Teng (Citation2002), for example, adopting a social exchange theoretic lens, distinguished the governance of network-level, multi-party relationship from dyadic relationships. Dyadic relationships rely on restricted social exchanges, where the two parties have direct reciprocity with each other. In contrast, network relationships rely on generalized social exchanges, where the obligations to one party could be transferred to another party in the network. Therefore, network transactions are governed through indirect reciprocity, where the members repay the favour gained from one member to a different member of the network. The importance of relational governance, as well, as coordination in network relationships is even more pronounced because it is challenging to design explicit contracts to govern networks (Li et al. Citation2012; Oliveira and Lumineau Citation2017). Such issues make the governance of inter-organizational networks fundamentally different from that of dyadic relationships and therefore warrant more detailed attention in future studies.

5. Conclusion

The paper advances our understanding regarding the conceptualisation and operationalisation of governance mechanisms in IORs. A myriad of papers draws on the notion of governance mechanisms to illustrate and explain various aspects of relationships. This research effort is timely, taking stock of this important and frequently used concept of governance mechanisms, and assessing whether a coherent body of knowledge has developed. In reviewing and synthesising extant literature studies, we provided one of the first comprehensive attempts to clarify exchange governance conceptualisation and operationalisation across management disciplines, including OSM studies. We position a comprehensive conceptual framework as a more coherent means of further developing the research agenda for the governance of IORs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jens K. Roehrich

Jens Roehrich is the HPC Chair in Supply Chain Innovation at the School of Management, University of Bath, UK. Before joining the University of Bath, Jens worked at Imperial College Business School, Imperial College London, UK. Significant strands of his research agenda explore the long-term interplay of contractual and relational exchange governance mechanisms and the management of public-private collaborations in the UK and across Europe. His research has been published in journals such as Journal of Management Studies, British Journal of Management, Social Science and Medicine, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Industrial Marketing and Management, and Production Planning and Control.

Kostas Selviaridis

Kostas Selviaridis is an Associate Professor in Operations Management at Lancaster University Management School, UK. His research concerns the governance of inter-organizational relationships in supply chains, with a focus on the role of contracting and its interplay with relational approaches to governance. Kostas’ current work concentrates on two areas: (a) contracting for innovation in the delivery of public services, and (b) the design and management of performance-based contracts. His research has appeared in international outlets such as the International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, Industrial Marketing Management, and the International Journal of Production Research.

Jas Kalra

Jas Kalra is a Research Fellow in HPC Supply Chain Innovation Lab, School of Management, University of Bath, UK. Before joining the University of Bath, Jas worked at the University of Manchester, UK. Jas's current research focuses on contractual and relational governance of inter-organizational relationships, orchestration of supply networks, and strategic procurement and management of professional services.

Wendy Van der Valk

Wendy van der Valk is an Associate Professor in Purchasing and Supply Chain Management at Tilburg University, The Netherlands. Her research focuses on (performance-based) contracting, and the interplay between contractual and relational governance in relation to exchange performance in the context of complex outsourcing projects. She has published in, amongst others, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, and Industrial Marketing Management.

Feng Fang

Feng Fang is a PhD candidate in Supply Chain Management at the Department of Management, Tilburg University, The Netherlands. Before that, he received his master degree in Industrial Engineering at Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands. His research interests are performance-based contracts, trust and buyer-supplier relationships.

References

- Ancona, D. G., G. A. Okhuysen, and L. A. Perlow. 2001. “Taking Time to Integrate Temporal Research.” The Academy of Management Review 26(4): 512–529. doi:10.2307/3560239.

- Argyres, N., and J. Bercovitz. 2015. “Franchisee Associations as Sources of Bargaining Power? Some Evidence.” Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 24(4): 811–832. doi:10.1111/jems.12111.

- Argyres, N., and K. J. Mayer. 2007. “Contract Design as a Firm Capability: An Integration of Learning and Transaction Cost Perspectives.” Academy of Management Review 32(4): 1060–1077. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.26585739.

- Arranz, N., and J. C. F. de Arroyabe. 2012. “Effect of Formal Contracts, Relational Norms and Trust on Performance of Joint Research and Development Projects.” British Journal of Management 23(4): 575–588. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00791.x.

- Baker, G., R. Gibbons, and K. J. Murphy. 2002. “Relational Contracts and the Theory of the Firm.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(1): 39–84. doi:10.1162/003355302753399445.

- Bastl, M., M. Johnson, H. Lightfoot, and S. Evans. 2012. “Buyer-Supplier Relationships in a Servitized Environment: An Examination with Cannon and Perreault’s Framework.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 32(6): 650–675. doi:10.1108/01443571211230916.

- Bercovitz, J. E. L., and B. B. Tyler. 2014. “Who I Am and How I Contract: The Effect of Contractors’ Roles on the Evolution of Contract Structure in University-Industry Research Agreements.” Organization Science 25(6): 1840–1859. doi:10.1287/orsc.2014.0917.

- Blumberg, B. F. 2001. “Cooperation Contracts between Embedded Firms.” Organization Studies 22(5): 825–852. doi:10.1177/0170840601225004.

- Bradach, J. L., and R. G. Eccles. 1989. “Price, Authority, and Trust: From Ideal Types to Plural Forms.” Annual Review of Sociology 15: 97–118. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.15.1.97.

- Bucklin, L. P., and S. Sengupta. 1993. “Organizing Successful co-Marketing Alliances.” Journal of Marketing 57(2): 32–46. doi:10.1177/002224299305700203.

- Burgess, K., P. J. Singh, and R. Koroglu. 2006. “Supply Chain Management: A Structured Literature Review and Implications for Future Research.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 26(7): 703–729. doi:10.1108/01443570610672202.

- Caldwell, N., J. K. Roehrich, and G. George. 2017. “Social Value Creation and Relational Coordination in Public-Private Collaborations.” Journal of Management Studies 54(6): 906–928. doi:10.1111/joms.12268.

- Caniëls, M. C. J., C. J. Gelderman, and N. P. Vermeulen. 2012. “The Interplay of Governance Mechanisms in Complex Procurement Projects.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 18(2): 113–121. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2012.04.007.

- Cannon, J. P., R. S. Achrol, and G. T. Gundlach. 2000. “Contracts, Norms and Plural Form Governance.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 28(2): 180–194. doi:10.1177/0092070300282001.

- Cao, Z., and F. Lumineau. 2015. “Revisiting the Interplay between Contractual and Relational Governance: A Qualitative and Meta-Analytic Investigation.” Journal of Operations Management 33–34(1): 15–42. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2014.09.009.

- Carey, S., B. Lawson, and D. R. Krause. 2011. “Social Capital Configuration, Legal Bonds and Performance in Buyer-Supplier Relationships.” Journal of Operations Management 29(4): 277–288. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2010.08.003.

- Carson, S. J., A. Madhok, and T. Wu. 2006. “Uncertainty, Opportunism, and Governance: The Effects of Volatility and Ambiguity on Formal and Relational Contracting.” Academy of Management Journal 49(5): 1058–1077. doi:10.5465/amj.2006.22798187.

- Chi, T. 2000. “Option to Acquire or Divest a Joint Venture.” Strategic Management Journal 21(6): 665–687. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200006)21:6<665::AID-SMJ109>3.0.CO;2-0.

- Collins, H. 1999. Regulating Contracts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cropper, S., M. Ebers, C. Huxham, and P. S. Ring. 2008. “Introducing Inter-Organizational Relations.” In The Oxford Handbook of Inter-Organizational Relations, edited by S. Cropper, M. Ebers, C. Huxham, and P. S. Ring. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Crossan, M., and M. Apaydin. 2010. “A Multi-Dimensional Framework of Organizational Innovation: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Journal of Management Studies 47(6): 1154–1191. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00880.x.

- Das, T. K., and B. S. Teng. 1998. “Between Trust and Control: Developing Confidence in Partner Cooperation in Alliances.” Academy of Management Review 23(3): 491–512. doi:10.5465/amr.1998.926623.

- Das, T. K., and B. S. Teng. 2001. “Trust, Control, and Risk in Strategic Alliances: An Integrated Framework.” Organization Studies 22 (2): 251–283. doi:10.1177/0170840601222004.

- Das, T. K., and B. S. Teng. 2002. “The Dynamics of Alliance Conditions in the Alliance Development Process.” Journal of Management Studies 39(5): 725–746. doi:10.1111/1467-6486.00006.

- Das, T. K., and N. Rahman. 2010. “Determinants of Partner Opportunism in Strategic Alliances: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Business and Psychology 25(1): 55–74. doi:10.1007/s10869-009-9132-2.

- Deakin, S., C. Lane, and F. Wilkinson. 1997. “Contract Law, Trust Relations, and Incentives for Co-operation: A Comparative Study.” In Contracts, Cooperation and Competition, edited by S. Deakin and J. Michie, 105–139. Oxford: University Press.

- Dean, T., D. A. Griffith, and R. J. Calantone. 2016. “New Product Creativity: Understanding Contract Specificity in New Product Introductions.” Journal of Marketing 80(2): 39–58. doi:10.1509/jm.14.0333.

- Duplat, V., and F. Lumineau. 2016. “Third Parties and Contract Design: The Case of Contracts for Technology Transfer.” Managerial and Decision Economics 37(6): 424–444. doi:10.1002/mde.2729.

- Durach, C. F., J. Kembro, and A. Wieland. 2017. “A New Paradigm for Systematic Literature Reviews in Supply Chain Management.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 53(4): 67–85. doi:10.1111/jscm.12145.

- Dyer, J. H. 1997. “Effective Interim Collaboration: How Firms Minimize Transaction Costs and Maximise Transaction Value.” Strategic Management Journal 18(7):535–556. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<535::AID-SMJ885>3.0.CO;2-Z.

- Dyer, J. H., and H. Singh. 1998. “The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage.” The Academy of Management Review 23(4): 660–679. doi:10.2307/259056.

- Easton, G. 2010. “Critical Realism in Case Study Research.” Industrial Marketing Management 39(1): 118–128. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.06.004.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. “Agency Theory: An Assessment and Review.” Academy of Management Review 14(1): 57–74. doi:10.5465/amr.1989.4279003.

- Essig, M., A. Glas, K. Selviaridis, and J. K. Roehrich. 2016. “Performance-Based Contracting in Business Markets.” Industrial Marketing Management 59: 5–11. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.10.007.

- Faems, D., M. Janssens, A. Madhok, and B. Van Looy. 2008. “Toward an Integrative Perspective on Alliance Governance: Connecting Contract Design, Trust Dynamics, and Contract Application.” Academy of Management Journal 51(6): 1053–1076. doi:10.5465/amj.2008.35732527.

- Ferguson, R. J., M. Paulin, and J. Bergeron. 2005. “Contractual Governance, Relational Governance, and the Performance of Interfirm Service Exchanges: The Influence of Boundary-Spanner Closeness.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 33(2): 217–234. doi:10.1177/0092070304270729.

- Frey, B. S., and R. Jegen. 2001. “Motivation Crowding Theory.” Journal of Economic Surveys 15(5): 589–611. doi:10.1111/1467-6419.00150.

- Friedman, R. A., and J. Podolny. 1992. “Differentiation of Boundary Spanning Roles: Labor Negotiations and Implications for Role Conflict.” Administrative Science Quarterly 37(1): 28–47. doi:10.2307/2393532.

- Geyskens, I., J. B. Steenkamp, and N. Kumar. 2006. “Make, Buy or Ally: A Transaction Cost Theory Meta-Analysis.” Academy of Management Journal 49(3): 519–543. doi:10.5465/amj.2006.21794670.

- Ghoshal, S., and P. Moran. 1996. “Bad for Practice: A Critique for the Transaction Cost Economics Theory.” The Academy of Management Review 21(1): 13–47. doi:10.2307/258627.

- Griffith, D. A., and M. B. Myers. 2005. “The Performance Implications of Strategic Fit of Relational Norm Governance Strategies in Global Supply Chain Relationships.” Journal of International Business Studies 36(3): 254–269. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400131.

- Gulati, R. 1995. “Does Familiarity Breed Trust? the Implications of Repeated Ties for Contractual Choice in Alliances.” Academy of Management Journal 38(1): 85–112. doi:10.2307/256729.

- Gulati, R., and J. A. Nickerson. 2008. “Interorganizational Trust, Governance Choice, and Exchange Performance.” Organization Science 19(5): 688–708. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0345.

- Halldórsson, A., and T. Skjøtt-Larsen. 2006. “Dynamics of Relationship Governance in TPL Arrangements – A Dyadic Perspective.” International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 36(7): 490–506. doi:10.1108/09600030610684944.

- Hartmann, A., J. K. Roehrich, L. Frederiksen, and A. Davies. 2014. “Procuring Complex Performance: The Transition Process in Public Infrastructure.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 32(2): 174–194. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-01-2011-0032.

- Hawker, S., S. Payne, C. Kerr, M. Hardey, and J. Powell. 2002. “Appraising the Evidence: Reviewing Disparate Data Systematically.” Qualitative Health Research 12(9): 1284–1299. doi:10.1177/1049732302238251.

- Heide, J. B., and G. John. 1992. “Do Norms Matter in Marketing Relationships?” Journal of Marketing 56(2): 32–44. doi:10.1177/002224299205600203.

- Heide, J. B. 1994. “Interorganizational Governance in Marketing Channels.” Journal of Marketing 58 (1): 71–85. doi:10.1177/002224299405800106.

- Howard, M. B., J. K. Roehrich, M. A. Lewis, and B. Squire. 2019. “Converging and Diverging Governance Mechanisms: The Role of (Dys) Function in Long-Term Inter-Organizational Relationships.” British Journal of Management 30(3): 624. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12254.

- Huemer, L., G. O. Boström, and C. Felzensztein. 2009. “Control-Trust Interplays and the Influence Paradox: A Comparative Study of MNC-Subsidiary Relationships.” Industrial Marketing Management 38(5): 520–528. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.12.019.

- Jap, S., and S. Ganesan. 2000. “Control Mechanisms and the Relationship Life Cycle: Implications for Safeguarding Specific Investments and Developing Commitment.” Journal of Marketing Research 37(2): 227–245. doi:10.1509/jmkr.37.2.227.18735.

- Jayaraman, V., S. Narayanan, Y. Luo, and J. M. Swaminathan. 2013. “Offshoring Business Process Services and Governance Control Mechanisms: An Examination of Service Providers from India.” Production and Operations Management 22(2): 314–334. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2011.01314.x.

- Kale, P., and H. Singh. 2007. “Building Firm Capabilities through Learning: The Role of the Alliance Capability and Firm-Level Alliance Success.” Strategic Management Journal 28(10): 981–1000. doi:10.1002/smj.616.

- Kale, P., H. Singh, and H. Perlmutter. 2000. “Learning and Protection of Proprietary Assets in Strategic Alliances: Building Relational Capital.” Strategic Management Journal 21(3): 217–237. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200003)21:3<217::AID-SMJ95>3.0.CO;2-Y.

- Kale, P., J. Dyer, and H. Singh. 2002. “Alliance Capability, Stock Market Response and Long-Term Alliance Success: The Role of the Alliance Function.” Strategic Management Journal 23(8): 747–767. doi:10.1002/smj.248.

- Kamann, D. J. F., C. Snijders, F. Tazelaar, and D. T. Welling. 2006. “The Ties That Bind: Buyer-Supplier Relations in the Construction Industry.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 12(1): 28–38. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2006.03.001.

- Kapsali, M., J. K. Roehrich, and P. Akhtar. 2019. ” “Effective Contracting for High Operational Performance.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 39(2): 294–325. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-10-2017-0604.

- Ketokivi, M. A., and R. G. Schroeder. 2004. “Perceptual Measures of Performance: Fact or Fiction?” Journal of Operations Management 22(3):247–264. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2002.07.001.

- Klein-Woolthuis, R., B. Hillebrand, and B. Nooteboom. 2005. “Trust, Contract and Relationship Development.” Organization Studies 26(6): 813–840. doi:10.1177/0170840605054594.

- Klein, B. 1996. “Why Hold-Ups Occur: The Self-Enforcing Range of Contractual Relationships.” Economic Inquiry 34(3): 444–463. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.1996.tb01388.x.

- Kreye, M., J. K. Roehrich, and M. A. Lewis. 2015. “Servitizing Manufacturers: The Importance of Service Complexity and Contractual and Relational Capabilities.” Production Planning and Control 26(14–15): 1233–1246. doi:10.1080/09537287.2015.1033489.

- Langley, A. 1999. “Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data.” Academy of Management Review 24(4): 691–710. doi:10.5465/amr.1999.2553248.

- Lazzarini, S. G., G. J. Miller, and T. R. Zenger. 2004. “Order with Some Law: Complementarity versus Substitution of Formal and Informal Arrangements.” Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 20(2): 261–298. doi:10.1093/jleo/ewh034.

- Lee, Y., and S. T. Cavusgil. 2006. “Enhancing Alliance Performance: The Effects of Contractual-Based versus Relational-Based Governance.” Journal of Business Research 59(8): 896–905. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.03.003.

- Li, D., L. Eden, M. A. Hitt, R. D. Ireland, and R. P. Garrett. 2012. “Governance in Multilateral Alliances.” Organization Science 23(4): 1191–1210. doi:10.1287/orsc.1110.0671.

- Liu, Y., Y. Luo, and T. Liu. 2009. “Governing Buyer-Supplier Relationships through Transactional and Relational Mechanisms: Evidence from China.” Journal of Operations Management 27(4): 294–309. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2008.09.004.

- Lorenzoni, G., and A. Lipparini. 1999. “The Leveraging of Inter-Firm Relationships as a Distinctive Organizational Capability: A Longitudinal Study.” Strategic Management Journal 20(4): 317–338. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199904)20:4<317::AID-SMJ28>3.0.CO;2-3.

- Lumineau, F. 2017. “How Contracts Influence Trust and Distrust.” Journal of Management 43(5): 1553–1577. doi:10.1177/0149206314556656.

- Lumineau, F., M. Fréchet, and D. Puthod. 2011. “An Organizational Learning Perspective on the contracting Process.” Strategic Organization 9 (1): 8–32. doi:10.1177/1476127011399182.

- Lumineau, F., and J. E. Henderson. 2012. “The Influence of Relational Experience and Contractual Governance on the Negotiation Strategy in Buyer-Supplier Disputes.” Journal of Operations Management 30(5): 382–395. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2012.03.005.

- Lumineau, F., and D. Malhotra. 2011. “Shadow of the Contract: How Contract Structure Shapes Interfirm Dispute Resolution.” Strategic Management Journal 32(5): 532–555. doi:10.1002/smj.890.

- Lumineau, F., and N. Oliveira. 2018. “A Pluralistic Perspective to Overcome Major Blind Spots in Research on Interorganizational Relationships.” Academy of Management Annals 12(1): 440–465. doi:10.5465/annals.2016.0033.

- Lumineau, F., and B. Quelin. 2012. “An Empirical Investigation of Inter-Organizational Opportunism and Contracting Mechanisms.” Strategic Organization 10(1): 55–84. doi:10.1177/1476127011434798.

- Lusch, R. F., and J. R. Brown. 1996. “Interdependency, Contracting, and Relational Behavior in Marketing Channels.” Journal of Marketing 60(4): 19–38. doi:10.2307/1251899.

- Lyons, B., and J. Mehta. 1997. “Contracts, Opportunism and Trust: Self-Interest and Social Orientation.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 21(2): 239–257. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a013668.

- Macaulay, S. 1963. “Non-Contractual Relations in Business: A Preliminary Study.” American Sociological Review 28(1): 55–67. doi:10.2307/2090458.

- Macneil, I. 1980. The New Social Contract: An Inquiry into Modern Contractual Relations. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Madhok, A., S. B. Tallman. 1998. “Resources, Transactions and Rents: Managing Value Through Interfirm Collaborative Relationships.” Organization Science 9: 326–339.

- Malhotra, D. 2009. “When Contracts Destroy Trust.” Harvard Business Review 87(5): 25.

- Malhotra, D., and F. Lumineau. 2011. “Trust and Collaboration in the Aftermath of Conflict: The Effects of Contract Structure.” Academy of Management Journal 54(5): 981–998. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.0683.

- Mayer, K. J., and N. S. Argyres. 2004. “Learning to Contract: Evidence from the Personal Computer Industry.” Organization Science 15(4): 394–410. doi:10.1287/orsc.1040.0074.

- Mellewigt, T., A. Madhok, and A. Weibel. 2007. “Trust and Formal Contracts in Interorganizational Relationships - Substitutes and Complements.” Managerial and Decision Economics 28(8): 833–847. doi:10.1002/mde.1321.

- Mayer, K. J., and D. J. Teece. 2008. “Unpacking Strategic Alliances: The Structure and Purpose of Alliance Versus Supplier Relationships.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 66 (1): 106–127. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2007.06.007.

- Mena, C., A. Humphries, and T. Y. Choi. 2013. “Toward a Theory of Multi-Tier Supply Chain Management.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 49(2): 58–77. doi:10.1111/jscm.12003.

- Neumann, K. 2010. “Ex Ante Governance Decisions in Inter-Organizational Relationships: A Case Study in the Airline Industry.” Management Accounting Research 21(4): 220–237. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2010.05.002.

- Ning, Y. 2017. “Combining Formal Controls and Trust to Improve Dwelling Fit-out Project Performance: A Configurational Analysis.” International Journal of Project Management 35(7): 1238–1252. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.06.002.

- North, D. C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: University Press.

- Oliveira, N., and F. Lumineau. 2017. “How Coordination Trajectories Influence the Performance of Interorganizational Project Networks.” Organization Science 28(6): 1029–1060. doi:10.1287/orsc.2017.1151.

- Olsen, B. E., S. A. Haugland, E. Karlsen, and G. J. Husoy. 2005. “Governance of Complex Procurements in the Oil and Gas Industry.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 11(1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2005.03.003.

- Ozmel, U., D. Yavuz, J. J. Reuer, and T. Zenger. 2017. “Network Prominence, Bargaining Power, and the Allocation of Value Capturing Rights in High-Tech Alliance Contracts.” Organization Science 28(5): 947–964. doi:10.1287/orsc.2017.1147.

- Pettigrew, A. M. 1990. “Longitudinal Field Research on Change: Theory and Practice.” Organization Science 1(3): 267–292. doi:10.1287/orsc.1.3.267.

- Pettigrew, A. M. 1997. “What Is Processual Analysis?” Scandinavian Journal of Management 13(4):337–348. doi:10.1016/S0956-5221(97)00020-1.

- Podonly, J. M. 1994. “Market Uncertainty and the Social Character of Economic Exchange.” Administrative Science Quarterly 39:458–483.

- Poppo, L., and T. Zenger. 2002. “Do Formal Contracts and Relational Governance Function as Substitutes or Complements?” Strategic Management Journal 23(8): 707–725. doi:10.1002/smj.249.

- Poppo, L., K. Z. Zhou, and S. Ryu. 2008. “Alternative Origins to Interorganizational Trust: An Interdependence Perspective on the Shadow of the past and the Shadow of the Future.” Organization Science 19(1): 39–55. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0281.

- Poppo, L., and K. Z. Zhou. 2014. “Managing Contracts for Fairness in Buyer-Supplier Exchanges.” Strategic Management Journal 35(10): 1508–1527. doi:10.1002/smj.2175.

- Provan, K. G., and P. Kenis. 2007. “Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18(2): 229–252. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum015.

- Provan, K. G., A. Fish, and J. Sydow. 2007. “Interorganizational Networks at the Network Level: A Review of the Empirical Literature on Whole Networks.” Journal of Management 33(3): 479–516. doi:10.1177/0149206307302554.

- Provan, K. G., and S. J. Skinner. 1989. “Interorganizational Dependence and Control as Predictors of Opportunism in Dealer-Supplier Relations.” Academy of Management Journal 32(1): 202–212. doi:10.2307/256427.

- Ranganathan, R.,. A. Ghosh, and L. Rosenkopf. 2018. “Competition-Cooperation Interplay during Multifirm Technology Coordination: The Effect of Firm Heterogeneity on Conflict and Consensus in a Technology Standards Organization.” Strategic Management Journal 39(12): 3193–3221. doi:10.1002/smj.2786.

- Rashman, L., E. Withers, and J. Hartley. 2009. “Organizational Learning and Knowledge in Public Service Organizations: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Management Reviews 11(4): 463–494. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00257.x.

- Reuer, J. J., and A. Ariño. 2007. “Strategic Alliance Contracts: Dimensions and Determinants of Contractual Complexity.” Strategic Management Journal 28(3): 313–330. doi:10.1002/smj.581.

- Rindfleisch, A., and J. B. Heide. 1997. “Transaction Cost Analysis: Past, Present, and Future Applications.” Journal of Marketing 61 (4): 30–53. doi:10.1177/002224299706100403.