Abstract

Companies must pursue both exploration and exploitation of supplier’s knowledge in increasingly competitive and complex production environments. This has been referred to as pursuing an ambidextrous supply strategy, extending the mobilisation of resources in pursuit of both aims beyond the borders of the lead manufacturer and into supplier organizations as well. Purchasing and supply management plays an increasingly central role in mobilizing and involving the suppliers in the pursuit of this agenda. The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the literature on organizational ambidexterity and operations management by exploring how purchasing departments contribute to the organizational pursuit of organizational ambidexterity. We explore practices followed by purchasing departments for mediating tensions between supply networks and organizational functions.

Introduction

Pursuing ambidextrous supply strategies influence the roles and practices of purchasing management. Purchasing plays an increasingly important role in exploiting the supply base and reaching cost-out targets (Hesping and Schiele Citation2015). Simultaneously, the competitive climate often requires companies to engage in collaborative innovation with suppliers to remain relevant to their customers. These conflicting demands challenge organisations to take on an integrative role in reconciling and mediating conflicting demands upon suppliers (Aoki and Wilhelm Citation2017). Organizational ambidexterity is increasingly used in studies of production planning and control (Petro et al. Citation2020). However, purchasing’s role in mobilizing the supply network to support organizational ambidexterity (OA) is unclear and has not received sufficient attention in the literature on procurement and supply management (Kauppila Citation2010; Aoki and Wilhelm Citation2017; Gualandris, Legenvre, and Kahlschmidt Citation2018). Purchasing may either take on an exploitative role or take on both explorative and exploitative roles. In the former case, purchasing's contribution is strictly one-sided. The latter case calls for OA at the departmental and even at the relational level. Purchasing functions must both leverage supply markets to reach the lowest total price (exploitation). Purchasing may also help the buying firm experiment and discover unexpected opportunities, thus transforming purchasing into an innovative function (Mikkelsen and Johnsen Citation2019). This paper explores how purchasing departments facilitate suppliers’ contributions to organizational ambidexterity (OA). More specifically, we explore how purchasing function in providing OA in different organizational and strategic settings. By organizational role, we mean the tasks purchasing are expected to carry out as an organizational entity in a more extensive organizational structure. We base our research on a comparative case study of managerial and organizational activities among purchasing managers in five medium to large-sized manufacturing companies. Several studies concern the ambidextrous organization's ability to learn from suppliers (Rothaermel and Alexandre Citation2009; Azadegan et al. Citation2013). We extend existing research by focussing on the role of the purchasing department in achieving OA and comparing and contrasting the role of suppliers in OA across multiple case contexts.

Defining organizational ambidexterity

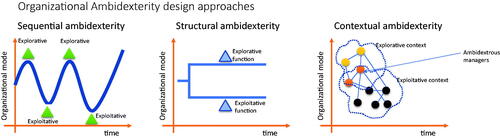

It is a fundamental axiom that organisational forms must match their environment to survive and prosper (Ashmos et al. Citation2000; Eisenhardt and Piezunka Citation2011). As business contexts become increasingly complex and posing paradoxical demands to maintain effective exchange conditions with their environments, organizational designs must become agile and flexible. The ambidexterity literature considers the organization's ability to provide different organizational responses to conflicting environmental demands. Tushman and O'Reilly (Citation1996) define OA as ‘The ability to simultaneously pursue both incremental and discontinuous innovation…from hosting multiple contradictory structures, processes, and cultures within the same firm’ (p. 24). Conscious organizational design efforts are needed, as exploration and exploitation efforts compete for the same scarce resources and – left unchecked – tend to crowd each other out (Kauppilla Citation2010). Exploration requires search activities outside the current operational parameters. It is associated with experimentation and risk-taking activities, and corresponding skill sets and organizational procedures supports it. Exploitation requires search within the existing operations for refinement and efficiency, typically associated with diametrically different skillsets and procedures (He and Wong Citation2004). However, there is no one way to shape organizational design to match the task environment. The organizational design literature debates different ways for an organizational form to achieve OA. It is divided into sequential, structural, and contextual ambidexterity (O’Reilly and Tushman Citation2013). These processes follow different logics and support various structures and practices, as outlined in .

The grounding principle for managing the tensions between exploration and exploitation activities is separating the two in time or space. Early on, Duncan (Citation1976) argued that organizations need to change their structure over time sequentially to align the organizational structure with the strategy to meet various environmental demands for innovation or efficiency. Burgelman (Citation1983) followed the organizational transition of projects from the forefront of technology change into becoming part of the operating core. He saw an organization as a system that emphasizes processes of variation, selection, and retention at different points in time. Taking a structural approach, Tushman and O’Reilly (Citation1996) suggested that there is a need for accommodating with simultaneous evolutionary and revolutionary changes in still more business contexts. Therefore, organizations need to structurally differentiate exploration and exploitation as a way to deal with unpredictable change and avoid excessive specialisation. Notably, as organizations grow and develop more formal structures, organizational designs may develop structural and cultural inertia. Separate organizational units can provide appropriate contexts for dealing with operational and innovative issues, as pointed out in the early literature (Lawrence and Lorsch Citation1967).

Furthermore, structural differentiation helps organizations maintain diverse sets of professional skills to deal with abruptly changing business contexts. Coordinating, integrating, and combining activities in this internal organizational environment has been described as a dynamic capability, resting on organizational routines and processes (Jansen et al. Citation2009). Gibson and Birkinshaw (Citation2004), adding activity as an organizing principle for creating separability, propose that individual managers can switch their attention between non-routine innovation and more routine operations. This way of separating tasks represents a third form of contextual OA. This form of OA differs from the previous two by not being anchored in organizational-level structural design. Instead, it presupposes managers’ ability to engage in paradoxical thinking, fulfil multiple roles, and conduct multiple tasks outside their formal job descriptions (Raisch and Birkinshaw Citation2008; Mom, Bosch, and Volberda Citation2009). Furthermore, in ambidextrous organizations, emphasis may quickly shift between exploring and exploiting, with rapid changes in top management attention and resources.

Purchasing’s role in OA

A chief responsibility of purchasing managers is to help to integrate the needs of internal and external constituents. The integration task involves mediating and coordinating between various functions inside the organisation and aligning activities and mobilising resources among suppliers in the supply network (Medlin and Törnroos Citation2015; Ardito et al. Citation2019). We are not the first to explore OA as a multilevel phenomenon, but other approaches have focussed on managerial roles in achieving OA rather than the departments' role (Kassotaki, Paroutis, and Morrell Citation2019). This multiple case study of the purchasing departments in five manufacturing companies shows the divergence in roles and responsibilities of purchasing departments when involved in operations and development activities internally and with supply networks.

Purchasing’s role in achieving organizational ambidexterity is complex, involving an understanding of the decision environment's complexity, how this complexity influences the organizational processes of adaptation, and purchasing’s function (Nair et al. Citation2015; Ozer and Zhang Citation2015). Ambidexterity theory has previously been used to study ‘ambidextrous supply chain strategies’ (Kristal et al. Citation2010), ‘ambidextrous technology sourcing’ (Rothaermel and Alexandre Citation2009), ‘ambidextrous governance’ (Blome et al. Citation2013) and ambidextrous capabilities (Roscoe and Blome Citation2019), and how these forms of ambidexterity benefit the buying firm. The role of purchasing is less discussed. In the strategic supply management literature, purchasing takes on a boundary-spanning role for the management and alignment of supplier relationships, involving both elements of exploration and exploitation (Schiele Citation2010; Zhang, Wu & Henke Citation2015). Purchasing’s contribution to exploitation involves assisting in achieving a high and uninterrupted operational flow between internal and external constituents: ‘The procurement function should obtain the proper equipment, material, supplies, and services of the right quality, at the right time and place, at the right price and from the right source’ (Aljian Citation1984, 3). It includes helping to integrate supplies in the overall material flow through monitoring and negotiating purchasing agreements, supplier selection, category management, and implementation of purchasing policies (Jain et al. Citation2009; Cigolini and Rossi Citation2010). Kauppila (Citation2010) suggests that suppliers are principally used for exploitation, whereas external relationships with knowledge-intensive partners such as universities drive exploration efforts. In this view, purchasing’s involvement in OA is one-sided. However, purchasing is increasingly also contributing to new technology scouting and sourcing (Lakemond Echtelt, and Wynstra Citation2001; Legenvre and Gualandris Citation2018), mobilizing supplier resources (Ellegaard and Koch Citation2012) and facilitating early supplier involvement in new product development (Schiele Citation2010). Gualandris et al. (Citation2018) conceptualise purchasing ambidexterity as a contextual capability. They argue that ‘for higher levels of ambidexterity, purchasing personnel will be allowed to make their own (contextual) judgments on how to best advance and balance efficiency-oriented and innovation-oriented activities’ (Gualandris et al. Citation2018, 672). In a similar vein, Mikkelsen and Johnsen (Citation2019) discuss the changing role of purchasing departments in supplier integration in innovation projects.

For purchasing departments, internal stakeholders' competing priorities oriented towards exploration and exploitation call for ongoing interpretation and reframing of their organizational role. Purchasing sits at the front end and seek to balance among strategic priorities on an ongoing basis. Internally, they must, at the same time, accommodate to sourcing requirements from different departments while also look for synergies and integration. Externally, they must motivate suppliers to provide resources and knowledge, while at the same time negotiate for increasing efficiency at low cost. How can high-cost savings be achieved while simultaneously increasing purchasing performance and other strategic priorities such as responsiveness or innovation (Schütz et al. Citation2020)?

Several tensions potentially influence purchasing’s potential role in achieving OA. First, the perceived importance of the suppliers’ resources varies across the organizations the purchasing department is part of, strongly impacting the tasks associated with pursuing ambidexterity. Whereas some find that drawing in the supply base may impact negatively on internal strategic integration (Benner and Tushman Citation2003), others find that significant gains may come from matching external inputs with internal exploration or exploitation processes (Lin, Yang and Demirkan Citation2007). Second, the purchasing department is a specialized component of a more extensive organizational system (Volberda and Lewin Citation2003); it may be more or less involved in responses to conflicting environmental demands.

Pursuing ambidexterity at the departmental level means that multiple demands of exploitation and exploration must be met – not only concerning differing internal demands and priorities, but particularly with the management of supplier relationships and networks. From the purchasing department's perspective, the different forms of OA demands manifest themselves in different ways in the organizational design ().

Table 1. An overview of OA at the purchasing department level.

In principle, the purchasing department can be ambidextrous themselves on the operational level or contribute to the strategic level of OA (Cantarello, Martini, and Nosella Citation2012). In the case of contextual ambidexterity, purchasing departments must often present the same supplier with demands regarding cost-out programs while simultaneously seeking to draw on their resources for collaborative innovation activities, following other organisational programs (Aoki and Wilhelm Citation2017). When communicating with suppliers, purchasing teams must integrate conflicting internal demands for cost savings with internal requirements of dedicating more external resources for development purposes, such as in the case of transitions towards increasing sustainability in the supply base (Carter and Rogers Citation2008). This shift is described with specific product development projects (Mikkelsen and Johnsen Citation2019). In other cases. Purchasing is responsible for executing purchasing strategies, with KPIs derived from the corporate strategy – but are dealing with influential suppliers whose real-time actions influence the corporate level (Pardo et al. Citation2011). When the purchasing department predominantly is meant to contribute to the strategic level of OA and exploitation issues best reflect their organisational mandate, they struggle with innovation demands towards suppliers raised by other organisational departments in contact with the supplier (Adler, Goldoftas, and Levine Citation1999). In any case, the potential tension between exploration and exploitation impacts the purchasing department and calls for strategies and practices to overcome these conflicting issues, which also will feedback on the OA principles mobilised. Purchasing's role in the Toyota study by Aoki and Wilhelm (Citation2017) illustrates this. In the following, we explore how OA impacts on purchasing's organizational role.

Methodology

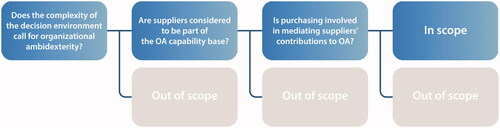

Our study builds on a two-year research project focussed on supplier resource mobilization in dynamic and changing environments, mainly how medium to large buying firms organize and manage processes and initiatives related to accessing and mobilizing their suppliers’ resources. Our case study includes data on various aspects of supplier relationships and internal relationships between different functional areas from the perspective of the buying organization and its suppliers. We adopt a comparative case study methodology to obtain detailed knowledge of the various dimensions and configurations of purchasing's role in pursuing supply network ambidexterity. More specifically, we apply a multiple-case embedded design, as our study includes five case companies and addresses multiple units of analysis (Yin Citation2013). Because the role of purchasing departments in OA is an under-researched area, we take an inductive approach (Meschnig, Carter, and Kaufmann, Citation2018). The selection of cases is based on purposeful rather than random sampling (Stake Citation2005). We are not contrasting the organizational role of a purchasing department operating in an ambidextrous organizational context to a purchasing department in a non-ambidextrous context. Instead, we focus on exploring how the purchasing department's roles in facilitating organizational ambidexterity unfold, given the boundary conditions selected ().

We selected cases for further scrutiny that initially looked interesting and rich for pursuing our research purpose (see Fourné et al., forthcoming, for a similar approach). Considering that we want to explore how purchasing facilitates suppliers’ contributions to OA, we applied several boundary conditions for selecting cases suited for our purpose.

The first selection criterion concerns the nature and complexity of the business context, as purchasing departments of companies operating in complex decision-making environments are prone to be exposed to more complexity (Stacey Citation1996). The complexity of decision environments is multifaceted, and definitions of complexity differ (Cannon and John Citation2007). Following Duncan (Citation1976), decision environment complexity is contingent upon the number of factors accounted for in the environment and the number of different states these can be configured in. Additionally, the frequency and nature of change add to the environmental complexity (Simon Citation1996). The complexity dimensions developed by Duncan (op. cit.) provide guidelines for the necessary but not sufficient boundary conditions for engaging in OA, including whether both gains from exploration and exploitation are pursued by the organisation (see also the OA selection criteria used by Wei, Zhao, and Zhang Citation2014).

The second case selection criterion concerns whether management’s focus is predominantly internal or external in OA's pursuit. When an internal focus dominates, managers pay limited heed to their suppliers’ potential contributions to innovation and cost management (Fawcett and Magnan Citation2002; Gadde, Håkansson, and Persson Citation2010; Florea and Corbos Citation2015). Contrastingly, we focus on firms that see their supply base as a strategically relevant resource (Lockamy and Mcormack Citation2004). A third but related criterion concerns purchasing’s involvement in exploration and exploitation activities. Several authors have discussed the importance of stimulating innovation activities using supply networks (Im and Rai Citation2008; Narasimhan and Narayanan Citation2013). Purchasing may deal with suppliers on a purely operational level, while development and other issues are dealt with by other departments (Araujo, Dubois, and Gadde Citation1999; Mogre, Lindgreen, and Hingley Citation2017). In the present context, we are interested in dilemmas in which internal and external demands on suppliers create managerial tensions for the purchasing department. Critical tensions among stakeholders call for the involvement of the next organizational level of authority, either up or down the organizational hierarchy. For instance, the arising of severe interpersonal tensions may call for intervention, reframing, and even re-design of tasks at the team or departmental level (Ellegaard and Andersen Citation2015). The separation of issues allows for structural differentiation and specialization of the organizational forms to pursue a specific objective, but aligning the two may provide interunit challenges. Integrating both demands within the same unit or team may create new ways of addressing issues. The organization of purchasing activities reflect these differences. Schiele (Citation2010) explores the challenges to the purchasing function in assuming the dual role of providing cost savings and innovation activities. He reports on case companies that divide the purchasing function into ‘advanced’ and ‘strategic’ sourcing departments, respectively focus on ‘technical’ and ‘commercial’ aspects.

All companies studied were medium or large multinational corporations. In companies (B and D), we focussed on the divisional level. The cases were selected based on their interests and activities, following Patton’s (Citation2007) recommendations for a purposive sampling strategy. The ability to mobilize the right resources from selected suppliers is highly essential for the case companies. Hence, each case company is at a stage where they have elaborate experience with involving strategic suppliers in various product and process development projects, yet also face challenges in further developing these strategic collaborations.

We relied on semi-structured interviews supplemented by internal documents for data collection, using the interview guide in Appendix 1. The selection of informants within each case followed a process of theoretical sampling, which is 'the purposeful selection of a sample according to the developing categories and emerging theory' (Coyne Citation1997). Our interviews started in the purchasing department; the number of people interviewed depended on this department's size. Informants typically included the head of purchasing, category managers, and purchasing assistants. We also identified and interviewed key personnel from purchasing, production, and R & D involved at different levels in particular strategic supplier relationships with our main contact person. This emerging interview process produced detailed knowledge of how actors at multiple organisational levels work with supplier involvement. In total, approximately we conducted 60 interviews for this study. We also made several site visits, and we carried through four seminars involving some or all of the case companies.

We recorded and transcribed all interviews, producing a substantial amount of material for coding and analysis. The interviews varied from 30 minutes to approximately 2 hours. Coding and interpreting data was an iterative process characterised by relatively few a priori constraints, but substantial use of theory (Orton Citation1997). In this process, we made sense of emerging categories from the empirical material by comparing them with existing theoretical ideas and concepts, just as we gradually refined our existing knowledge (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002). When relevant and feasible, we also used internal documents and other data sources. Given this study's explorative nature, we firmly focussed on maintaining flexibility in our coding, avoiding premature saturation, and maintaining possibilities for combining and recombining data, insights, and emerging theory. Thus, coding from emerging to saturated themes was done manually rather than using coding software, as qualitative coding software can distance the researcher too much from the data (Macmillan and Koenig Citation2004). below illustrates our coding approach.

Table 2. Examples of cross-case coding using multiple data sources and cases.

A few of our concepts were defined a priori but changed as we iterated between data, theory, and insights. Hence, our data analysis approach has been less prescriptive than the process often associated with grounded theory, and closer to contextual template analysis (King Citation2004). According to Beverland and Lindgreen (Citation2010), qualitative case studies in business research are often not sufficiently explicit when explaining reliability and external/internal validity issues. These traditional positivist quality criteria, initially developed for quantitative research, have been developed to fit qualitative research. First, Guba (Citation1979) suggested that qualitative research should be seen as 'auditable,' 'confirmable,' and 'credible' rather than as 'reliable' and 'valid' in the usual sense. Schwandt, Lincoln, and Guba (Citation2007) discuss 'trustworthiness' as a key concept for qualitative research and relate it to four criteria: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility is closely related to internal validity. We take to ensure credibility in the present study to carefully outline, develop, and deploy a semi-structured interviewing protocol (Appendix 1 of this paper show our interview protocol). Furthermore, before conducting interviews in the case companies, the authors have visited the companies and developed a profile for each case company to develop early familiarity. Also, to corroborate findings from individual interviews, triangulation with other interviews, and other data have been carried out. Transferability, the notion to which insights obtained from case research can (or should) be used in generalisation, is close to issues regarding reliability and external validity. It is also an issue of much controversy in the literature on case research methodology (Runfola et al. Citation2017). As pointed out by Ketokivi and Choi (Citation2014), qualitative researchers' challenge is not an empirical but theoretical generalization. The subject matter of case research cannot be uniqueness. It concerns the extent to which generality can be found in terms of theory: why should someone who neither knows anything about nor is in any way interested in the empirical context be interested in reading the contribution? We ensured transferability by framing our explorative research question in the existing OA literature. We adopted core concepts such as forms of ambidexterity and the organizational involvement of purchasing departments.

Case descriptions and cross-case analysis

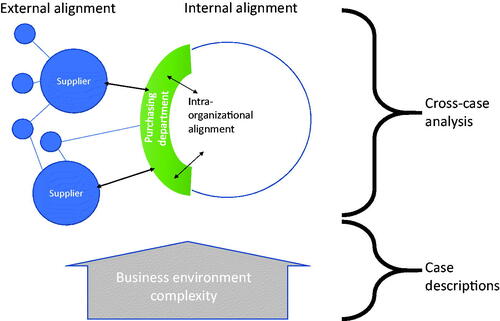

shows how the case descriptions and the cross-case analysis are linked. The case description section presents the case companies and discuss the environmental complexity that triggers ambidexterity. In the cross-case analysis section, we discuss purchasing's role in achieving OA's external and internal alignment capabilities.

Case descriptions

What follows is a brief description of the case companies and their business environments. provides an overview of selected essential information on each case company, such as organizational structure (Jacobides Citation2007), purchasing function type (Van Weele Citation2009), and suppliers' role (supporting exploration, exploitation, or both).

Table 3. Case company overview.

All the case companies studied are active in the manufacturing sector. Case company A is a division-based multinational enterprise that develops and provides components, products, and systems solutions primarily for the building and construction industry. Contracting with suppliers is done centrally, but operational purchasing activities are decentralized. Company B produces theatrical lightning and other heavy-duty stage light products for professional customers. The purchasing department is responsible for all strategic and tactical purchasing decisions. Shortly after the interview period, they were acquired by a large Japanese company and is now an independent division in this Company. Company C also has a division-based organizational structure. The MNE produces high-end hi-fi sound and vision products. Together with manufacturing, the purchasing function is heavily involved in developing and maintaining relationships with key suppliers, which provides a range of critical technologies. At the time of the interview, the Company employed 2000 persons. Company D maintains a matrix organization, where units are organized and managed both about technologies and markets. The Company produces monitoring and surveillance solutions for the military aerospace and aviation sectors. Given a strong focus on small-scale project development in teams, the purchasing department plays a hybrid role, combining elements of decentralized and decentralized purchasing, while at the same time having a staff function for the top management suite. Company E is a multinational enterprise that produces heavy-duty circulation pumps to provide water and other fluids. Its organizational structure is division-based. It is recognized as a technology leader in its field. Corporate and local (divisional and local) purchasing divide responsibilities and activities.

The competitive environment facing all case companies is highly complex and dynamic, which underlines agility and adaptability and triggers the need for organizational ambidexterity. All our companies also face unpredictability issues related to digitalisation and new regulatory demands from increased pressure on sustainability, which drive environmental complexity. Hence, in the case companies studied, sustaining market success depends on the ability to both exploit current capabilities to compete in a cost-efficient manner, while at the same time exploring new technologies and innovation opportunities. Several case companies find themselves at the intersection of mature and evolving technologies and need to accommodate the diverging skillsets underlying congruent performance in these business environments.

Cross-case analysis: internal organizational alignment and principles of OA

Across all the case companies investigated, the purchasing departments have a high degree of adaptability and preparedness. They are capable of shifting between exploration issues and exploitation issues. Hence, contextual ambidexterity was emerging or already present, supporting other findings of purchasing's increasingly ambidextrous role (Schiele Citation2010).

Expectations towards flexibility and ability to work in different contexts was present in all purchasers’ job descriptions. An underlying driver is the purchasing departments’ need to engage with different operational requirements. The ongoing pressure for performing on both cost management and innovation issues also has consequences for individual employees' purchasing function. Furthermore, they must make judgments and take initiatives on an ongoing basis that can help forestall or alleviate tensions between priorities linked to the aims of exploration and exploitation activities. However, the purchasing department’s involvement in pursuing ambidextrous goals and dealing with the exploration-exploitation tension varies. In some companies, the OA role is designed into the purchasing organization, for instance, by assigning this function to a specific sub-team of purchasers working across category teams. In other cases, the entire category management team is involved sequentially in exploration and exploitation. Therefore, our study revealed a nuanced picture of the different OA design principles than often described in the literature characterizing OA at the organizational level. In , we have outlined overall defining aspects of the purchasing department's OA role in the case companies using the OA forms.

Table 4. Purchasing department's role in pursuing different forms of OA.

Across all the case companies, the purchasing department has a mediating role of linking the internal processes of exploration and exploitation, dividing their time between conflicting demands and taking on informal roles similar to what the literature on contextual ambidexterity describes (Gibson and Birkinshaw Citation2004). All the case company informants mentioned that interpersonal communication across departmental and organisational boundaries was critical for their ability to function. This observation underscores the importance of purchasing managers’ ability to cross exploration and exploitation contexts and thus engage with different managerial mindsets both inside and outside operational requirements. However, there was variation concerning how purchasing departments' principles for combining contextual ambidexterity with other forms of OA. Two OA configurations surfaced: case company A and E where formal organization structure the tasks of the purchasing department (the structurally dominant forms of OA) and case company B, C and D where the informal modes dominated (the sequentially dominant OA forms). As Jacobides (Citation2007) describes, organisational structures shape the attention and roles of departments, defining what is central and marginal in their roles. In case company A and E, suppliers' expected contribution to exploration (in the form of for instance cost-out innovation, testing or the like) and exploitation (in the form of for instance reaching target prices, reducing warehouse and logistical costs or other ways of increasing efficiency) were partitioned roles and ‘owned’ by the purchasing departments as their distinctive organizational task.

Secondly, structural and sequential ambidexterity such as formalized job descriptions or subunits (found in departments for company A and E) or purchasing participating in project teams (Case company B, C and D) lend support to the purchasing manager’s role as both knowledge provider and voicing operational issues in R&D activities. Still, in many cases, the shift between exploration and exploitation focus is managed through temporal organizing in project teams. Project teams are a way to create informal, mediating, and department-spanning task forces in organizations – in both formal and informal forms of OA.

Structurally dominant forms of OA in purchasing

Separating the management of supplier involvement in product development tasks from the commercial side of supplier relationships is used in company A and E’s purchasing departments. For the purchasing department, being assigned with managing the ongoing dualities of innovation and cost management, means that a) top management has delegated this responsibility to the purchasing department – for instance by including both contributions to cost savings and innovations in the key performance indicators (KPIs) used to manage the performance of the department and the department must deal with meeting both KPIs. Other organizational stakeholders are actively and persistently lobbying for influence and the supplier on the purchasing and supplier selection criteria. Purchasing may be represented in a committee or board, overseeing relationships with suppliers and manage supplier communication. When the buying organizations separate the responsibilities of supplier involvement in cost management and innovation issues, we observed that a similar separation in the supplier-buyer interface. For example, in both Company B and C, separate meetings with suppliers were conducted by the purchasing and product development departments. Company A and E both formalized supplier relationship management through their purchasing departments. The formalization means that the purchasing organization is chiefly responsible for managing supplier relationships and essential boundary spanners between supplier organizations and the buying company departments. Purchasers are involved in organizing and managing innovation activities and the more traditional activities of ensuring suppliers' ability to deliver and focus on cost management issues. As explained by company E, there is a strong focus on managing corporate processes for the rest of the organization.

We are following corporate purchasing processes and look at three main processes: Strategic sourcing, Supplier relationship management, and operational management. We own the processes and execute them. We try to keep up with future developments through our SRM program and mediate an open dialogue through our strategic sourcing procedures. Operational issue such as strategic contracting is handled in the operational management subroutines.

They participate in meetings between the supplier and various departments in the buying company and is also involved in internal product development or quality management meetings related to supplier issues. Also, purchasers actively search and involve suppliers and internal departments to seek out novel insights. In case company A, the purchasing department has an integral role, reflected in their KPIs, and is responsible for maintaining the overall dialogue with suppliers. More often than not, internal development teams involve informal talks with development engineers from supplier firms. Here, the purchasing department instead seeks to install general policies regarding when and how to inform purchasing concerning important events. Hence, to inform about this (and to hinder an unnecessary expansion of the existing supply base), purchasing officers actively invite themselves to the internal development team meetings to convey their information to the development teams. The purchasing departments take on the relationship management role and formally intermediate between the organization to ensure alignment can sometimes be problematic. Case Company E experienced a situation where discussions between purchasing and new product development concerning the continued role of relationships to one particular supplier was unsolvable. Seen from the new product development's perspective, this supplier was critical for a significant innovation activity. Strategic supply department found it impossible to work with the supplier and pressured for a replacement. This conflict made top management step in and transfer the responsibility for managing relationships with this particular supplier to the new product development function. This function developed a small internal team dealing with supplier relationships, including also purchasers from strategic purchasing in a liaison role.

Sequentially dominant forms of OA in purchasing

The observed differences in suppliers' perceived role as contributors to OA have consequences for the extent and nature of the boundary-spanning activities taken on by purchasing. For example, in case company C, suppliers are internally recognized as relevant to product development and operational issues. Most production is outsourced and assembled in an intricate global web of suppliers. Cost optimization is strongly oriented towards reducing sourcing costs and ensuring logistical flows and external quality inspection targets in collaboration with suppliers. Informants in case company C illustrates the idea of sequential ambidexterity. Interestingly, as the product moves from prototype to mass production, the suppliers involved in dialogues on product development and contributing to innovation are the same suppliers presented with strict cost reduction targets

In Company D, where customer offerings are customized and often one-of-a-kind, market success depends on intensive interactions with customers and suppliers. Suppliers’ ability to co-develop solutions means that they are involved early in the development of market offerings.

In company B, organizational role tensions arose as the purchasing organization attempted to take on a substantial role and formalize relationships with suppliers important for innovation activities. Whereas strategic purchasing considered the supplier as potentially problematic for further production, R & D saw the supplier as indispensable for further developing a significant new product line. Parallel to the critical role of the supply base in manufacturing, suppliers also deliver a broad range of product development technologies. Company D is continuously engaged in dialogue with suppliers regarding technical specifications and new uses of provided technologies. In such situations, the purchasing function's role is highly integrative, and purchasing is involved in both technical and commercial discussions with suppliers and the manufacturer's organizational units. Company C expressed this issue of aligning and pursuing the dual aims of exploration and exploitation within one organisational unit as ‘friendly battles,’ describing it in terms of opposite perspectives promoting creative thinking. This form of organisation also creates competing agendas. Thus, prioritization issues between exploration and exploitation activities frequently surface. The following quote from a purchasing manager in Company C points out prioritisation issues.

When purchasing host meetings, where quality control and purchasing are involved, it is all about procurement. Even during our supplier days (where they invite suppliers to present new technologies and discuss new product development). It is precisely the same when we participate in department meetings. It is all about cost, lead times, etc. Maybe other issues will be given 15 minutes of the entire 2-hour agenda.

Even though departments divided responsibilities for managing innovation activities and cost management with suppliers, this made less sense as the issue interrelated, and the separation of meetings produced ongoing tensions. In Company B, the purchasing department facilitates both cost optimization and innovation activities with suppliers. Purchasing relationships with selected strategic suppliers are managed from the purchasing organization by key supply purchasers, which, besides often having an engineering education, also have a background in development activities. This manager's job is to maintain supplier attractiveness and work closely with the selected suppliers to retain early access to suppliers’ technology developments and provide an overview of the rest of the organisation.

I am CC on every mail correspondence with the supplier. I may not be directly involved in every conversation, but I know what is going on … I have weekly meetings with the engineers involved in this particular field (manager, Company B)

Suppliers perceive innovation and cost management is interrelated, and their willingness to mobilise resources in support of a customer's innovation activities relates to the same customer's cost-cutting pressures. Hence, to accommodate both objectives at the corporate level, interdepartmental talks and ongoing adjustments between buyer and supplier departments must be made when purchasing policies impact innovation activities or vice versa. In the present cases, socialisation and interpersonal relationships between department representatives across organisational boundaries seem to be a key for solving ongoing issues. In some cases, problems are intractable, and management makes formal adjustments on the departmental or inter-organizational levels to restore supplier relationships.

At the same time, the category manager mediates discussions concerning cost savings and process optimizations. Companies C and D share certain traits regarding the organizational support of ambidextrous supplier involvement. In both organizations, purchasing partakes in product development activities and cost optimizations; project development dominates the organization, and the purchasing department assigns members to the project organization. In Company C, purchasing is at the centre of product development, as suppliers' technologies drive a major share of the technical features of the products produced. In this organization, the departmental boundaries between concept development and purchasing often blur. However, the organizing process is changing from an organizational set-up in which purchasing has full control over supplier communication to a new set-up in which suppliers participate. Physical co-location of members of the product development department, quality control, and purchasing managers helps create open communication lines and supports knowledge sharing across departmental boundaries. This set-up is a change from the previous purchasing organisation, which was implemented to solve cost control issues and to keep product development in alignment with the cost regime of the Company. However, in step with Company C outsourcing still more technologies, the policy was causing many delays and troublesome processing decisions as purchasing officers relayed information.

Organization people and I think it is not wrong to have people responsible for day to day and the same people responsible for the strategy, but if day to day takes up so much of the time, it is a problem. You see that firefighters are the heroes in many organizations, but the people who are heroes and solved the problem should not have been here in the first place.

This has created situations in which development engineers sought to shortcut connections to suppliers.

The previous procurement manager said that we need to control everything, and you are not allowed to communicate with suppliers — procurement should communicate with suppliers….

Interviewer: …OK?

And then there was anarchy, so what happened and … if I am not allowed, I do it and then I do not tell. They ended up in the worst situation they can be in. (R&D Engineer, Company C)

The proposed solution has been to increase contextual ambidexterity using ‘double-hat roles’ and increase the agility to sequentially shifts throughout the organisation. An example of a double-hat role is that product development, in their interactions with strategic suppliers, also addresses purchasing and delivery issues, which typically would have less to do with explorative search. Still, they engage suppliers in contextual ambidexterity as well.

External alignment: purchasing’s role in mobilizing the supply network for OA

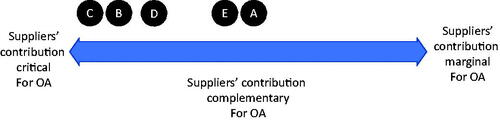

In parallel to the two main ways in which purchasing supported organizational alignment for OA, the case companies similarly followed two routes for achieving external integration with suppliers. In the cases studied, the customer value proposition and correspondingly the interface with customers influenced whether the supply base was critical or complimentary for OA. It was possible to identify two forms of supply network mobilisation, which reflected the importance of technology inputs from suppliers: Suppliers are seen either as critical or complementary for the organization's ability to build ambidexterity. By critical, we assume that the organisation’s external dependence on the suppliers’ input (technology or otherwise) limits its internal degrees of freedom concerning operations, innovation, or both (Pfeffer and Salancick Citation2003). Complementary in this context means that suppliers provide strategically important inputs for exploration and/or exploitation, but are subsumed the internal manufacturing activities, and internal resources and capabilities (with some difficulty) can be mobilised to replace the external. In cases where suppliers’ contributions are marginal for organizational ambidexterity (for instance, in cases where suppliers input is a standardized commodity purchased on spot market terms), there is no buyer dependence. In our cases, the suppliers’ contribution to the manufacturers OA is distributed on the continuum outlined in below.

Suppliers as critical for building organizational ambidexterity

In three case companies (B, C, and partly in company D), the relationships to strategic suppliers are paramount to the Company's exploration abilities and ability to develop gradual improvements and achieve operational excellence. New supplier-driven technologies strongly influence the manufacturers' value proposal in their customer markets and may change the buyers’ ability to position themselves in the market. An example from company C is access to wireless technology standards or voice recognition used in active loudspeakers. Critical dependence also means that all functions and management levels of the organization consider building and managing critical supplier relationships and that several organizational stakeholders are involved in some form of dialogue with strategically important suppliers. For the purchasing departments, this suggests that they have an integrative role towards strategic suppliers. Spanning the organizational boundaries between the supplier organization and multiple constituents in the buying firm requires departmental practices to represent and ongoing reconciliation of different priorities among constituents' activities. Taking on this task requires sharp insights into most aspects of suppliers' activities, resources, capabilities, and purchasing departments to organize internally according to key supply management practices. The following quotes from category managers from case companies B, C, and D show this ().

Table 5. Alignment and boundary spanning practices of purchasing managers when suppliers are critical for OA.

Purchasing officers participate in or are briefed on the interactions between the supplier and various departments in the buying company and are also involved in internal product development or quality management meetings related to supplier issues. Supplier collaboration is at the core of their activities, and the R&D function is directly involved with supplier development resources. Case company D has tailored market activities to meet the needs of long-standing critical customers. Meeting their needs typically also involves the configuration of a supply base to meet the market solution's specific technical requirements. Component suppliers are critical for developing new and innovative solutions tailored to specific customers. Therefore, engineers from the development teams are eager to involve engineers from supplier firms early in development to ensure leading-edge components. Simultaneously, this Company serves customers having extreme demands for flawless operations. The ability to live up to these operational targets depends on the suppliers' ability to continue error-free deliveries of specialised components. Hence, there is a trade-off for this Company's overall interest in selecting the most appropriate suppliers for development purposes and the most reliable supply bases for continuous delivery.

Suppliers as complementary for building organizational ambidexterity

In Companies A and E, suppliers’ inputs complement internal technology building. These companies differ from the first group by being less technologically dependent on strategic suppliers and suffering less from prohibitively high exit costs. In these companies, the purchasing organization plays an important mediating role. It is primarily responsible for managing supplier relationships and acts as a liaison between supplier organisations and other departments in the buying company. Also, purchasers are involved in organizing and managing innovation activities, along with the traditional activities of cost management and on-time delivery ().

Table 6. Alignment and spanning practices of purchasing managers when suppliers are complementary for OA.

Separating the management of supplier involvement in product development tasks from the commercial side of supplier relationships is the commonly used practice in these companies. This practice does not imply that purchasing is excluded from these activities or are unaffected by them. On the contrary, they have a relatively clear mandate and exercise their influence to make sure that R & D or management do not overstep corporate purchasing policies. For instance, purchasing may be represented on a committee or board, oversee relationships with suppliers, or control all supplier communication. Furthermore, this does not mean that purchasing does not face tensions related to the dual aims of involving suppliers in innovation and cost management activities. Tensions typically emerge with aligning new suppliers with existing supply policies. Purchasing participates in introducing new suppliers into the case companies’ supply bases and typically administers a range of supply policies and practices (such as supplier certifications) used by the manufacturer. Purchasing may work with these new suppliers and need a policy to manage supplier relationships and avoid confusion or conflicts that may occur when different companies’ departments communicate with the same supplier, but without internal coordination.

Purchasers actively search for novel insights, involving suppliers and internal departments. In case company E, the purchasing department typically organizes regular meetings with suppliers, setting the agenda for such meetings, and collecting information. Additionally, the supplier is also responsible for organizing technological foresight activities, where those responsible for technological development in both firms would meet and exchange insights and expectations regarding coming technologies and their impact on current and future investment and production activities. Also, purchasing specialists sit in on product development committees and provide insights on the supplier or activate their network of contacts in the supplier firm.

Discussion

The present cross-case analysis has provided insights into the evolving role of purchasing departments in organisations, who increasingly rely on mobilizing supply networks for achieving OA. In this sense, the paper extends the evolving literature on supply networks contribution for OA. Manufacturers mobilize supply networks for a broad range of activities relating to exploration, exploitation, or both at the same time. Examples from the cases included suppliers providing exploration input to technology search, problem specification, product testing, process development as well as exploitation inputs, such as contributing to cost-out processes, quality insurance, lean supply systems, etc… The results concerning the purchasing departments’ role in this phenomenon complement recent studies on ambidexterity governance (Blome et al. Citation2013). Our findings suggest that purchasing departments combine different forms of OA. At the core, purchasing department managers provide flexibility and integration in cross-functional teams along with contextual ambidexterity lines. However, the study also shows that purchasing departments play different roles in mobilising suppliers and meditating with internal functions to support supply network ambidexterity. The roles studied co-vary with the criticality of the supplier inputs and complexity of supplier involvement for the manufacturing organization. When supplier inputs are critical for company performance, buyer-supplier relationships become more complex. There is a broad-based, and unstructured dialog were members from several departments from the manufacturing organisation and the supplier organization. Employees from several departments are involved in exchanging insights with the supplier, often on an informal and open-ended basis. Purchasing has a participative or consulting role. Other departments ask purchasers for advice, where purchasing provides a support function, complementing activities of other departments and seeking to jockey purchasing priorities. In cases where supplier inputs are more complementary for OA, purchasing takes on a more central and integrative role, channelling a substantial part of the organizational activities and taking formal responsibility for policing the corporate purchasing policies. It verifies the requisite variety principle in organisational design literature. Which suggests that the number of possible states of a control mechanism must be greater than or equal to the number of states in the system being controlled. The organisational design and capability of the purchasing function must be able to match the forms of variation it is facing (Boisot and McKelvey Citation2011).

The principle of requisite variety has consequences for these departments' organizations and activities as they become designed to accommodate the different needs for involving suppliers in activities with other organisational functions. Organizational structure directs attention for individuals and departments and influences this and their degree of formalization. Clearly, in less formalized organizations, alignment between external and internal actors is more comfortable for purchasing departments. However, their ability to pursue formulated goals related to OA is less outspoken than in organizational structures that grant them a clearer mandate. Purchasing departments also develop new liaisons with departments — they build informal teams with managers from other departments on an ad hoc basis or become formally represented in standing workgroups. Relatedly, purchasing departments take on new responsibilities and are increasingly engaged in developing and providing market offerings. Thus, the skill profiles of purchasing managers are changing in these organizations. In step with new responsibilities becoming increasingly important, traditional skills related to purchasing are increasingly taken on by others in the supply network.

The study also shows that the purchasing department's contribution to ambidexterity is more pragmatic and multifaceted than ideal types or modes of ambidexterity discussed in the literature. A finding from this study, which supports previous research on OA, was that OA's principles discussed earlier were not alternatives. Instead, many principles for achieving ambidexterity complemented each other, as seen in other studies of OA (Adler, Goldoftas, and Levine Citation1999; Andriopoulos and Lewis Citation2009). However, there are different ways for purchasing to be involved.

The ongoing pressures to perform on both cost management and innovation issues have consequences for the purchasing function. They face priority dilemmas and a lack of solutions that will satisfy all stakeholders involved. Furthermore, they must make judgments as well as take initiatives on an ongoing basis to help forestall or alleviate tensions between priorities linked to the aims of exploration and exploitation activities. This type of functioning requires norms and management practices in the purchasing department that encourage and support professional capabilities development. It requires attracting extrovert personnel, and requires the support of the development of personal characteristics that can be helpful in multitasking and political problem solving, such as efficacious behaviour, mediation, brokering, and cooperation. Secondly, this study shows that conflicting demands upon purchasing departments abound from these changes, producing organizational tensions. These tensions manifest themselves and are dealt with differently through following and combining different modes of OA in the case organizations studied. Finally, the study confirms the notion made by others that even though OA ambitions and forms penetrate to purchasing departments as well, there is a tendency for purchasing – in more structured and formalised organisational contexts, to emphasise exploitation over exploration (see also Eisenhardt Citation2013).

Conclusions and impact for research and management practice

Our research contributes to managerial practice as well as to research. For purchasing managers, understanding the critical connection between internal and external demands and how they reflect the organisation's overall fitness and value proposition is a valuable insight when it comes to pursuing their roles effectively. There is not one single way in which purchasing departments can integrate or contribute to OA. The findings suggest that both the supply network's status and the role of suppliers' technology for the value proposition of the manufacturer influence the form of OA that is manifested in the purchasing departments. We believe that considering these factors in organizational development and design will improve practice and increase the possibilities for increasing strategic and operational management fitness.

This study contributes to the research agenda for literature on strategic purchasing and the literature on OA, by outlining critical organizational tensions regarding internal and external orientations in this activity and discussing how and the extent to which the purchasing department may be involved in these activities. Future research on organizational research may build on these insights. Also, for purchasing and supply management research, the integrative role of purchasing in strategy is an important topic to explore further. This study has limitations, as well. Foremost, the empirical departure point of this study was the purchasing function. This starting point biased the perspectives explored and conveyed; we suspect that some additional nuances to purchasing’s role would have been found if we had started our interviews elsewhere in the organisation. However, giving voice to the purchasing perspective is also an important rationale for the paper in the first place.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Poul Houman Andersen

Poul Houman Andersen is Professor at Aalborg University Business School and head of the PhD School at the Faculty of Social Sciences at Aalborg University. In addition, he is part time Professor in supply management at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. His research interest covers research methodology, strategy, operations management and the organizing of buyer–seller relationships. He is the author and co-author of several books and has published more than 60 papers in academic journals, such as Business Strategy and the Environment, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, California Management Review and Industrial Marketing Management.

Chris Ellegaard

Chris Ellegaard is professor at the School of Business and Social Sciences at Aarhus University, Denmark. His research interests lie within the area strategic purchasing and supply management, with a particular focus on buyer–supplier relationships, supply risk management, supplier development and sourcing decision making. He has published papers in a range of Journals, including International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Journal of World Business and Supply Chain Management.

Hanne Kragh

Hanne Kragh is an Associate Professor at School of Business and Social Sciences, Aarhus University, Denmark. Her research focuses on the organization and management of buyer–supplier relationships including supplier involvement in innovation. She has published in journals such as Industrial Marketing Management, Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, Management Decision and Journal of Change Management.

References

- Adler, P. S., B. Goldoftas, and D. I. Levine. 1999. “Flexibility Versus Efficiency? A Case Study of Model Changeovers in the Toyota Production System.” Organization Science 10 (1): 43–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.1.43.

- Aljian, G. W. 1984. Procurement Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Andriopoulos, C., and M. W. Lewis. 2009. “Exploitation-Exploration Tensions and Organizational Ambidexterity: Managing Paradoxes of Innovation.” Organization Science 20 (4): 696–717. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0406.

- Aoki, K., and M. Wilhelm. 2017. “The Role of Ambidexterity in Managing Buyer–Supplier Relationships: The Toyota Case.” Organization Science 28 (6): 1080–1097. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1156.

- Araujo, L., A. Dubois, and L. E. Gadde. 1999. “Managing Interfaces with Suppliers.” Industrial Marketing Management 28 (5): 497–506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(99)00077-2.

- Ardito, L., E. Peruffo, and A. Natalicchio. 2019. “The Relationships between the Internationalization of Alliance Portfolio Diversity, Individual Incentives, and Innovation Ambidexterity: A Microfoundational Approach.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 148: 119714. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119714.

- Ashmos, D. P., D. Duchon, and R. R. McDaniel Jr., 2000. “Organizational Responses to Complexity: The Effect on Organizational Performance.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 13 (6): 577–595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810010378597.

- Azadegan, A.,. P. C. Patel, A. Zangoueinezhad, and K. Linderman. 2013. “The Effect of Environmental Complexity and Environmental Dynamism on Lean Practices.” Journal of Operations Management 31 (4): 193–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2013.03.002.

- Benner, M. J., and M. L. Tushman. 2003. “Exploitation, Exploration, and Process Management: The Productivity Dilemma Revisited.” The Academy of Management Review 28 (2): 238–256. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/30040711.

- Beverland, M., and A. Lindgreen. 2010. “What Makes a Good Case Study? a Positivist Review of Qualitative Case Research Published in Industrial Marketing Management, 1971–2006.” Industrial Marketing Management 39 (1): 56–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.09.005.

- Blome, C., T. Schoenherr, and M. Kaesser. 2013. “Ambidextrous Governance in Supply Chains: The Impact on Innovation and Cost Performance.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 49 (4): 59–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12033.

- Boisot, M., and B. McKelvey. 2011. “Complexity and Organization-Environment Relations: Revisiting Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety.” The Sage Handbook of Complexity and Management : 279–298.doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446201084.n17.

- Burgelman, R. A. 1983. “A Process Model of Internal Corporate Venturing in the Diversified Major Firm.” Administrative Science Quarterly 28 (2): 223–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2392619.

- Cannon, A. R., and C. H. S. John. 2007. “Measuring Environmental Complexity: A Theoretical and Empirical Assessment.” Organizational Research Methods 10 (2): 296–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106291058.

- Cantarello, S., A. Martini, and A. Nosella. 2012. “A Multilevel Model for Organizational Ambidexterity in the Search Phase of the Innovation Process.” Creativity and Innovation Management 21 (1): 28–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2012.00624.x.

- Carter, C. R., and D. S. Rogers. 2008. “A Framework of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: moving toward New Theory.” International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 38 (5): 360–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030810882816.

- Cigolini, R., and T. Rossi. 2010. “Managing Operational Risks along the Oil Supply Chain.” Production Planning and Control 21 (5): 452–467. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09537280903453695.

- Coyne, I. T. 1997. “Sampling in Qualitative Research. Purposeful and Theoretical Sampling; Merging or Clear Boundaries?” Journal of Advanced Nursing 26 (3): 623–630. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-25-00999.x.

- Dubois, A., and L. E. Gadde. 2002. “Systematic Combining: An Abductive Approach to Case Research.” Journal of Business Research 55 (7): 553–560. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8.

- Duncan, R., B. 1976. “The Ambidextrous Organization: Designing Dual Structures for Innovation.” In The Management of Organization Design, Vol. 1: Strategies and Implementation, edited by R. H. Kilmann, and D. Pondy, and E. Slevin, 167–188. New York: North-Holland.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 2013. “Top Management Teams and the Performance of Entrepreneurial Firms.” Small Business Economics 40 (4): 805–816.

- Eisenhardt, K., and H. Piezunka. 2011. “Complexity Theory and Corporate Strategy.” Chapter 29. In The Sage Handbook of Complexity and Management, edited by P. Allen, S. Maguire, and B. McKelvey, 506–523. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

- Ellegaard, C., and P. H. Andersen. 2015. “The Process of Resolving Severe Conflict in Buyer–Supplier Relationships.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 31 (4): 457–470. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2015.06.004.

- Ellegaard, C., and C. Koch. 2012. “The Effects of Low Internal Integration between Purchasing and Operations on Suppliers’ Resource Mobilization.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 18 (3): 148–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2012.06.001.

- Fawcett, S. E., and G. M. Magnan. 2002. “The Rhetoric and Reality of Supply Chain Integration.” International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 32 (5): 339–361. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030210436222.

- Florea, A. I. I., and R. A. Corbos. 2015. “Supplier Relationship Strategies in the Automotive Industry: An International Comparative Analysis.” Revista de Management Comparat International 16 (4): 451.

- Gadde, L.-E., H. Håkansson, and G. Persson. 2010. Supply Network Strategies. 2nd ed., New York: Wiley.

- Gibson, C. B., and J. Birkinshaw. 2004. “The Antecedents, Consequences, and Mediating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity.” Academy of Management Journal 47 (2): 209–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/20159573.

- Gualandris, J., H. Legenvre, and M. Kalchschmidt. 2018. “Exploration and Exploitation within Supply Networks: Examining Purchasing Ambidexterity and Its Multiple Performance Implications.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 38 (3): 667–689. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-03-2017-0162.

- Guba, E. G. 1979. “Naturalistic Inquiry.” Improving Human Performance Quarterly 8 (4): 268–276.

- He, Z. L., and P. K. Wong. 2004. “Exploration vs. Exploitation: An Empirical Test of the Ambidexterity Hypothesis.” Organization Science 15 (4): 481–494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0078.

- Hesping, F., and H. Schiele. 2015. “Purchasing Strategy Development: A Multilevel Review.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 21 (2): 138–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2014.12.005.

- Im, G., and A. Rai. 2008. “Knowledge Sharing Ambidexterity in Long-Term Interorganizational Relationships.” Management Science 54 (7): 1281–1296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1080.0902.

- Jacobides, Michael G. 2007. “The Inherent Limits of Organizational Structure and the Unfulfilled Role of Hierarchy: Lessons from a near-War.” Organization Science 18 (3): 455–477. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0278.

- Jain, V., S. Wadhwa, and S. G. Deshmukh. 2009. “Revisiting Information Systems to Support a Dynamic Supply Chain: Issues and Perspectives.” Production Planning and Control 20 (1): 17–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09537280802608019.

- Jansen, J. J. P., M. P. Tempelaar, F. A. J. van den Bosch, and H. W. Volberda. 2009. “Structural Differentiation and Ambidexterity: The Mediating Role of Integration Mechanisms.” Organization Science 20 (4): 797–811. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0415.

- Kassotaki, O., S. Paroutis, and K. Morrell. 2019. “Ambidexterity Penetration across Multiple Organizational Levels in an Aerospace and Defense Organization.” Long Range Planning 52 (3): 366–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.06.002.

- Kauppila, O. P. 2010. “Creating Ambidexterity by Integrating and Balancing Structurally Separate Interorganizational Partnerships.” Strategic Organization 8 (4): 283–312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127010387409.

- Ketokivi, M., and T. Choi. 2014. “Renaissance of Case Research as a Scientific Method.” Journal of Operations Management 32 (5): 232–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2014.03.004.

- King, N. 2004. “Using Template Analysis in the Qualitative Analysis of Text.” Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. London: Sage.

- Kristal, M. M., X. Huang, and A. V. Roth. 2010. “The Effect of an Ambidextrous Supply Chain Strategy on Combinative Competitive Capabilities and Business Performance.” Journal of Operations Management 28 (5): 415–429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.12.002.

- Lakemond, N., F. Echtelt, and F. Wynstra. 2001. “A Configuration Typology for Involving Purchasing Specialists in Product Development.” The Journal of Supply Chain Management 37 (4): 11–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2001.tb00108.x.

- Lawrence, P. R., and J. W. Lorsch. 1967. “Differentiation and Integration in Complex Organizations.” Administrative Science Quarterly 12 (1): 1–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2391211.

- Legenvre, H., and J. Gualandris. 2018. “Innovation Sourcing Excellence: Three Purchasing Capabilities for Success.” Business Horizons 61 (1): 95–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2017.09.009.

- Lin, Z., H. Yang, and I. Demirkan. 2007. “The Performance Consequences of Ambidexterity in Strategic Alliance Formations: Empirical Investigation and Computational Theorizing.” Management Science 53 (10): 1645–1658. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1070.0712.

- Lockamy, A., III, and K. McCormack. 2004. “The Development of a Supply Chain Management Process Maturity Model Using the Concepts of Business Process Orientation.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 9 (4): 272–278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540410550019.

- MacMillan, K., and T. Koenig. 2004. “The Wow Factor: Preconceptions and Expectations for Data Analysis Software in Qualitative Research.” Social Science Computer Review 22 (2): 179–186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439303262625.

- Medlin, C. J., and J. Å. Törnroos. 2015. “Exploring and Exploiting Network Relationships to Commercialize Technology: A Biofuel Case.” Industrial Marketing Management 49: 42–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.05.036.

- Meschnig, G., C. Carter, and L. Kaufmann. 2018. “Conducting Multilevel Studies in Purchasing and Supply Management Research.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 24 (4): 338–342. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2017.11.001.

- Mikkelsen, O. S., and T. E. Johnsen. 2019. “Purchasing Involvement in Technologically Uncertain New Product Development Projects: Challenges and Implications.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 25 (3): 100496. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2018.03.003.

- Miller, D. 1993. “The Architecture of Simplicity.” Academy of Management Review 18 (1): 116–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1993.3997509.

- Mogre, R., A. Lindgreen, and M. Hingley. 2017. “Tracing the Evolution of Purchasing Research: future Trends and Directions for Purchasing Practices.” Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 32 (2): 251–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-01-2016-0004.

- Mom, Tom J. M., Frans A. J. Van Den Bosch, and Henk W. Volberda. 2009. “Understanding Variation in Managers' Ambidexterity: Investigating Direct and Interaction Effects of Formal Structural and Personal Coordination Mechanisms.” Organization Science 20 (4): 812–828. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0427.

- Nair, A., J. Jayaram, and A. Das. 2015. “Strategic Purchasing Participation, Supplier Selection, Supplier Evaluation and Purchasing Performance.” International Journal of Production Research 53 (20): 6263–6278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2015.1047983.

- Narasimhan, R., and S. Narayanan. 2013. “Perspectives on Supply Network-Enabled Innovations.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 49 (4): 27–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12026.

- O'Reilly, C. A., III, and M. L. Tushman. 2013. “Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, Present, and Future.” Academy of Management Perspectives 27 (4): 324–338. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2013.0025.

- Orton, J. D. 1997. “From Inductive to Iterative Grounded Theory: Zipping the Gap between Process Theory and Process Data.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 13 (4): 419–438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0956-5221(97)00027-4.

- Ozer, M., and W. Zhang. 2015. “The Effects of Geographic and Network Ties on Exploitative and Exploratory Product Innovation.” Strategic Management Journal 36 (7): 1105–1114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2263.

- Pardo, C., O. Missirilian, P. Portier, and R. Salle. 2011. “Barriers to the “Key Supplierization” of the Firm.” Industrial Marketing Management 40 (6): 853–861. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.06.029.

- Patton, M. Q. 2007. Sampling, Qualitative (Purposive). Blackwell, London: The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology.

- Petro, Y., U. Ojiako, T. Williams, and A. Marshall. 2020. “Organizational Ambidexterity: using Project Portfolio Management to Support Project-Level Ambidexterity.” Production Planning and Control 31 (4): 287–307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2019.1630683.

- Pfeffer, J., and G. R. Salancik. 2003. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Raisch, S., and J. Birkinshaw. 2008. “Organizational Ambidexterity: Antecedents.” Journal of Management 34 (3): 375–409. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316058.

- Roscoe, S., and C. Blome. 2019. “Understanding the Emergence of Redistributed Manufacturing: An Ambidexterity Perspective.” Production Planning and Control 30 (7): 496–509. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2018.1540051.

- Rothaermel, F. T., and M. T. Alexandre. 2009. “Ambidexterity in Technology Sourcing: The Moderating Role of Absorptive Capacity.” Organization Science 20 (4): 759–780. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0404.

- Runfola, A., A. Perna, E. Baraldi, and G. L. Gregori. 2017. “The Use of Qualitative Case Studies in Top Business and Management Journals: A Quantitative Analysis of Recent Patterns.” European Management Journal 35 (1): 116–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.04.001.

- Schiele, H. 2010. “Early Supplier Integration: The Dual Role of Purchasing in New Product Development.” R&D Management 40 (2): 138–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2010.00602.x.

- Schütz, K., M. Kässer, C. Blome, and K. Foerstl. 2020. “How to Achieve Cost Savings and Strategic Performance in Purchasing Simultaneously: A Knowledge-Based View.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 26 (2): 100534. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2019.04.002.

- Schwandt, T. A., Y. S. Lincoln, and E. G. Guba. 2007. “Judging Interpretations: But is It Rigorous? Trustworthiness and Authenticity in Naturalistic Evaluation.” New Directions for Evaluation 2007 (114): 11–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.223.

- Simon, H. A. 1996. The Sciences of the Artificial. Boston, Mass: MIT press.

- Stacey, R. 1996. “Emerging Strategies for a Chaotic Environment.” Long Range Planning 29 (2): 182–189. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(96)00006-4.

- Stake, R. 2005. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Tushman, M. K., and C. A. O'Reilly. III 1996. “Ambidextrous Organizations: Managing Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change.” California Management Review 38 (4): 8–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/41165852.

- Van Weele, A. J.(2009). Purchasing and supply chain management: Analysis, strategy, planning and practice. Cengage Learning EMEA.

- Volberda, H. W., and A. Y. Lewin. 2003. “Co‐Evolutionary Dynamics within and between Firms: From Evolution to co‐Evolution.” Journal of Management Studies 40 (8): 2111–2136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-6486.2003.00414.x.

- Wei, Z., J. Zhao, and C. Zhang. 2014. “Organizational Ambidexterity, Market Orientation, and Firm Performance.” Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 33: 134–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2014.06.001.

- Yin, R. K. 2013. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Newbury Park: Sage publications.