Abstract

Suppliers and transport service providers are key parties in the construction supply chain, and their respective roles when employing a construction logistics setup based on third-party logistics are investigated. The use of construction logistics setups is an ongoing trend for large and complex construction projects and previous research has mainly focussed on the downstream actors. The purpose is to explore how suppliers and transport service providers in the construction supply chain are affected by the use of dedicated and project-specific construction logistics setups outsourced to third-party logistics providers in construction projects. The upstream actors’ attitudes towards and experienced effects from construction logistics setups operated by a third-party logistics provider, as well as their level of supply chain management maturity are studied in an explorative case study of a large construction project. Results show positive attitudes and that suppliers and transport service providers actively address supply chain management issues, whereas actual effects of the construction logistics setup on upstream actors, in this case, are inconclusive. Yet, the analysis indicates that a third-party logistics provider can assume the role of a systems integrator in the construction supply chain, balancing, and possibly, integrating the supply chain with the construction site.

Introduction

The construction industry is typically an engineer-to-order (ETO) industry where most of the products are physically big and immobile, and consequently have to be produced on their future site of use (Gosling et al. Citation2015; Gosling and Naim Citation2009). Therefore the construction process is carried out in temporary organisations (Bakker Citation2010), establishing temporary supply chains (Behera, Mohanty, and Prakash Citation2015; Dubois and Gadde Citation2002; Vrijhoef and Koskela Citation2000). As much as 60–80% of the gross work done in construction projects involves the buying-in of materials and services from suppliers and subcontractors (Dainty, Briscoe, and Millett Citation2001; Scholman Citation1997), leading to that these supply chain actors heavily impact the performance of construction projects (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002; Miller, Packham, and Thomas Citation2002). Hence, the construction supply chain is regarded as complex with interactions between multiple actors during the construction process (Bankvall et al. Citation2010; Winch Citation2001).

In order to support more efficient production as well as reducing the environmental impact of construction and at the same time improving health and safety, both on and around construction sites, the construction industry actors have been implementing supply chain management (SCM) principles. Yet, research has identified a lack of in-house knowledge of SCM and logistics amongst clients and contractors (Thunberg Citation2013; Cox Citation2008). To mitigate this lack of knowledge, contractors and clients have more frequently started to turn to third-party logistics (TPL) providers to set up specialised and project-specific construction logistics arrangements that take over all or parts of the logistics management in construction projects in a structured way. This is an ongoing trend and is typically done for large construction projects (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016; Sundquist, Gadde, and Hulthén Citation2018) and for urban development districts (Hedborg Bengtsson Citation2019; Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019; Ekeskär, Havenvid, and Karrbom Gustavsson Citation2019). As such, a construction logistics setup can be defined as the way that the logistics system, including elements, components, information systems, etc., are designed and arranged to handle logistics in a construction project. The construction logistics setups offered by the TPL providers are typically dedicated to managing materials and logistics on construction sites, a task traditionally performed by the contractors, but also to sequence deliveries to site and to offer logistics services like resources for unloading, traffic control, etc. This is a new and innovative phenomenon in the construction industry for both clients and contractors, but also for TPL providers not traditionally being very active in the construction industry and therefore unfamiliar with the conditions of the construction site and supply chains (Langley Citation2015; Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016; Hedborg Bengtsson Citation2019).

When outsourcing the logistics on a construction site to a TPL provider, the structure of the traditional construction supply chain changes, affecting not only the contractors working at the construction site but also upstream actors such as suppliers, wholesalers and transport service providers serving the construction industry. Hence, they all face new challenges with dedicated and specialised construction logistics setups in construction projects and on the basis of this Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016, 175) conclude that ‘there is a need to explore how this new phenomenon impacts construction projects in general and the performance of the construction supply chain in particular’. Previous studies of dedicated and specialised construction logistics setups in the construction industry have mainly focussed on the downstream actors on the construction site. Hence, there is a need for studying the perspectives of upstream actors when these types of construction logistics setups are used in construction projects. A perspective requested by scholars in previous studies (cf. Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016; Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019).

The purpose of this paper is therefore to explore how suppliers and transport service providers in the construction supply chain are affected by the use of dedicated and project-specific construction logistics setups outsourced to TPL providers in construction projects. Since TPL is a relatively new phenomenon in construction (Langley Citation2015), the study is of explorative nature. Furthermore, since TPL in this context is regarded to be a part of SCM, the analysis will be based on an SCM perspective.

In line with the purpose, three research questions (RQs) have been defined to guide the study. The first question relates to the study by Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016) who identified that contractors perceived suppliers and transport service providers to be negative towards a construction logistics setup outsourced to TPL providers, and thereby hindering the evolution of SCM practices in construction. The second question investigates any effects the suppliers and transport service providers experienced due to the use of a mandatory construction logistics setup. The third question is grounded in both RQ1 and RQ2 and relates to the definition of SCM provided by Mentzer et al. (Citation2001), arguing that all entities must have a supply chain orientation (SCO) to reach the full potential of SCM.

RQ1 What are suppliers’ and transport service providers’ attitudes towards the use of dedicated and project specific construction logistics setups?

RQ2 What effects do suppliers and transport service providers experience when a dedicated construction logistics setup is employed?

RQ3 How does the level of supply chain orientation (SCO) affect the attitudes and experienced effects of suppliers and transport service providers, as part of a dedicated and specialised construction logistics setup?

After this introduction, the literature review describes the theoretical framework of SCM and TPL, and how they have been applied in the construction industry. Then the research design is described together with a description of the studied case. The case study is a large hospital construction project with an implemented project-specific construction logistics setup operated by a TPL provider, and the analysis is focussing on identifying experienced effects on suppliers and transport service providers that are a result from the TPL implementation. The empirical results are analysed from a SCM perspective and discussed. Finally, conclusions are presented together with suggestions for future research.

Literature review

Supply chain management (SCM)

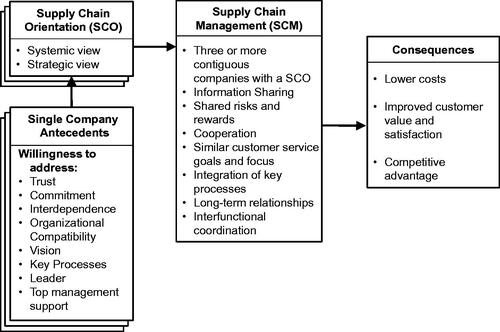

Mentzer et al. (Citation2001, 4) define a supply chain as ‘a set of three or more entities (organisations or individuals) directly involved in the upstream and downstream flows of products, services, finances, and/or information from a source to a customer’. Mentzer et al. (Citation2001) further argue that to realise SCM all participating actors must have a supply chain orientation (SCO), see , which includes to address a set of eight antecedents in a systemic and strategic way: trust, commitment, interdependency, organisational compatibility, agreed SCM visions and key processes, support from the top management, and acceptance of a leading role. The members of a supply chain are the entities that directly or indirectly interact with each other through its suppliers or customers (Lambert and Cooper Citation2000), and according to Mentzer et al. (Citation2001) all of them must have a SCO in order for SCM to be fully realised across the supply chain.

Figure 1. SCM antecedents and consequences based on Mentzer et al. (Citation2001).

Although the eight antecedents are different and have to be addressed individually, they are connected to each other and all of them are important. In order for a company to engage in a long-term cooperation such as SCM, trust and commitment are essential attributes (Mentzer et al. Citation2001). The company must be committed to share risk and rewards with the other companies in the supply chain. However, if trust among the actors in the supply chain is not established it is hard for a company to fully commit to the necessary obligations. Trust can be interpreted as the willingness to rely on the other actors and is essential in order to share risks and rewards. This means that the companies in the supply chain are depending on each other (interdependence) and therefore need to maintain a relationship with the other companies in the supply chain. Furthermore, a company’s organisational culture must be compatible with other companies in order for SCM to be successful. This includes shared visions of what the realisation of SCM should lead to and key processes that supports the efforts towards adopting SCM (Mentzer et al. Citation2001). Examples of key processes are customer relationship management, customer service management, demand management, order fulfilment, manufacturing flow management, procurement, product development and commercialisation, and returns (Lambert and Cooper Citation2000). Furthermore, the supply chain is in need of a leader to coordinate and manage the supply chain. A specific company may act as a leader because of their size, economic power or the initiating of relationships between companies. However, it is important that the leadership is constructive; otherwise other companies might end the cooperation. Finally, every company striving for SCM must have support from the top management. Top level managers have a large impact on the organisational performance and the lack of top management support can be a barrier to SCM (Mentzer et al. Citation2001).

When all the companies in the supply chain have an SCO, SCM (including information sharing, shared risks and rewards, cooperation, integration of key processes, long-term relationships and inter-functional coordination) may lead to positive effects in terms of lower costs, improved customer value and competitive advantage (Mentzer et al. Citation2001). By pulling together the different definitions of SCM Mentzer et al. (Citation2001, 18) provides a uniform definition of SCM: ‘the systemic, strategic coordination of the traditional business functions and the tactics across these business functions within a particular company and across businesses within the supply chain, for the purposes of improving the long-term performance of the individual companies and the supply chain as a whole’.

Third-party logistics

TPL has gained a lot of academic interest the past decade (Akbari Citation2018; Selviaridis and Spring Citation2007), as well as in practice with several companies from different industry sectors using TPL providers for managing all, or parts of, their logistic operations (Marasco Citation2008). TPL could be seen as logistics alliances or logistics partnerships (Skjoett-Larsen Citation2000), and therefore the concept of SCO also applies to TPL. Marasco (Citation2008, 128) defines TPL as ‘an external organisation that performs all or part of a company’s logistics function’. By outsourcing logistics to a third-party, companies free up resources and are able to focus on their core business (König and Spinler Citation2016). TPL setups are based on contractual relations and are often offered as a bundle of logistics services, typically including transport, warehousing and inventory management (e.g. materials handling, repackaging) (van Laarhoven, Berglund, and Peters Citation2000; Hertz and Alfredsson Citation2003). However, different value-adding activities (e.g. secondary assembly, installation of products), information related activities (e.g. tracking and tracing, distribution planning), and design of the supply chain have become more important as a service offered by TPL providers (van Laarhoven, Berglund, and Peters Citation2000; Hertz and Alfredsson Citation2003; van Hoek Citation2000a, Citation2000b). Since companies increasingly want to focus on core competences, outsourcing of activities, also including value-adding services, to TPL providers have become more important (König and Spinler Citation2016; Marasco Citation2008). Also so-called fourth-party logistics has emerged, which are arrangements closer to SCM than logistics management, focussing on the managerial, planning and strategic aspects of logistics (Selviaridis and Spring Citation2007).

Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016) did a meta-type literature review on driving forces for and concerns with implementing TPL. Among the driving forces a TPL could be said to help with focussing on core competencies, enhance flexibility, lower costs and reducing capital tied up in assets, inventory levels and order cycle times, as well as providing better lead time performance and delivery service. Among the concerns that speak against a TPL setup was: loss of control and in-house capability, fear of an unrealistic fee structure, a lack of knowledge on own internal costs for logistics, and fear of inadequate competence of the TPL provider. In urban areas reduced traffic and environmental sustainability goals have also been raised as examples of driving forces for TPL (Hedborg Bengtsson Citation2019; Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019).

SCM in the construction industry

SCM has been advocated and studied for decades in the construction industry (Aloini et al. Citation2012), but has yet failed to be adopted at a great extent compared to other industry sectors (Fernie and Tennant Citation2013; Bankvall et al. Citation2010; Segerstedt and Olofsson Citation2010). In order for SCM to be properly adopted in construction, SCM solutions from manufacturing industries cannot be directly transferred to the construction industry without considering the construction industry context (Tennant and Fernie Citation2014). Many of the SCM initiatives in construction have been linked to strategic alliances (Meng, Sun, and Jones Citation2011) and partnering agreements (Bygballe, Jahre, and Swärd Citation2010; Eriksson, Dickinson, and Khalfan Citation2007). However, focus has been towards dyadic partnering agreements between clients and contractors, failing to involve other supply chain actors (Bemelmans et al. Citation2012; Meng Citation2013; Bygballe, Jahre, and Swärd Citation2010). Furthermore, the construction industry is loosely coupled with small interactions between projects and permanent organisations. Actors seldom interact after a project is finished and construction projects can be considered as temporary networks of actors that dissolve when the construction project ends (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002, Citation2000). Partnering agreements aims to mitigate this and to increase cooperation between actors, however, the cooperation is mostly short-termed project partnering rather than strategically focussed partnering over several projects (Bygballe, Jahre, and Swärd Citation2010). The client’s procurement process heavily influences how the relationships are setup. By involving subcontractors early on and adopt long-term perspectives, subcontractors could better contribute and establish an innovation-friendly climate (Eriksson, Dickinson, and Khalfan Citation2007).

Even though the construction industry is organised as loosely coupled systems with small interactions between projects and permanent organisations (Dubois and Gadde Citation2000, Citation2002), projects are never disconnected from their parent organisations (Engwall Citation2003). Bemelmans et al. (Citation2012) studied this through the lens of buyer-supplier relationships in the Dutch construction industry, addressing different levels within construction companies: project, regional, business, and corporate levels. Their findings indicate that most companies have only reached the project level, indicating a low level of maturity. The study confirms results from previous studies that there is a lack in procurement processes, formal systems to evaluate and measure suppliers, and proactive mindsets towards suppliers. However, there are also positive tendencies such as active processes to reduce logistical steps and that companies are actively developing formal supplier integration programmes. Bemelmans et al. (Citation2012, 171) conclude that by ‘involving suppliers in value-creation projects, construction companies can maximise their use of the knowledge of suppliers in developing new products, processes or services’. Similarly Martinsuo and Sariola (Citation2015) studied how component and materials suppliers can work together with architects and structural engineers in order to offer expertise on material selections. They also noticed that the suppliers can influence how contractors purchase materials and their purchasing behaviour.

A construction site resembles a temporary factory (Bygballe and Ingemansson Citation2014) with at least three different kinds of temporary supply chains: labour (i.e. contractors and construction workers), machines and equipment (e.g. tools, scaffolding, cranes, etc.), and materials (Cox and Ireland Citation2002). Due to the temporary organising of operations and supply chains in construction (Gosling et al. Citation2015), SCM in construction must focus on coordinating the fragmented operations, the sourcing of materials and resources to the construction site, on coordinating materials and resources on the construction site itself, and on coordinating return flows from the site (Behera, Mohanty, and Prakash Citation2015). In this context, Vrijhoef and Koskela (Citation2000) describe four roles that SCM can play to improve coordination and enhance construction operations: (1) focus on the interface between the supply chain and site activities, (2) focus on improving the supply chain, (3) transferring site activities from the site to the supply chain, and (4) manage the site and the supply chain as an integrated domain. Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016) described that a fifth role, focus on the construction site, also is needed to fully cover both the construction supply chain and the site.

TPL in the construction industry

Even though outsourcing activities to consultants and subcontractors are common in the construction industry, which also is the main factor behind the fragmentation of the construction industry, the handling of materials is traditionally kept in-house (Cox and Ireland Citation2002; Miller, Packham, and Thomas Citation2002). In a study by Jesper and Josephson (Citation2005) construction workers spent close to 15% of their working time moving materials and equipment to the assembly area. Sobotka and Czarnigowska (Citation2005) notice that by outsourcing the logistics processes, such as handling construction materials, costs can be reduced. By keeping the contractors’ own transports and storage at a minimum, and let logistics professionals manage the logistics, costs were reduced. Huttu and Martinsuo (Citation2015) exemplify that suppliers with their competence may be a source of value-adding services on the construction site, including packaging materials in order of installation, sequence deliveries, and scheduling just-in-time (JIT) deliveries according to the installation process to avoid storage of materials on the construction site. A supplier might even go further and installing a component, instead of having subcontractor on the construction site doing it.

In the last decade, TPL providers have started to offer specialised setups to the construction industry. These TPL providers set up dedicated and specialised construction logistics setups on, or in the vicinity of, construction sites, thereby taking over the logistics of the construction sites and establish structured interfaces between supply chains and construction sites (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016). In large construction projects and urban development projects, these types of outsourced logistics setups are often mandatory to use for all involved actors and are often initiated by clients (large projects, see e.g. Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016; Sundquist, Gadde, and Hulthén Citation2018) or municipalities (urban development districts, see e.g. Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019).

These setups are also examples of how clients and municipalities, by stating requirements on the construction industry actors, innovate and attempts to adopt SCM (Havenvid et al. Citation2016), in line with the suggestion of client driven change by Briscoe et al. (Citation2004). However, the initiatives are often not primarily motivated by improved logistics and to adopt SCM, rather in order to increase sustainability or to reduce the construction projects disturbance on third parties and the surrounding society (cf. Hedborg Bengtsson Citation2019; Sundquist, Gadde, and Hulthén Citation2018). The use of TPL in terms of construction logistics setups is a rather new phenomenon and has gained some research interests during recent years. lists some of the recent studies that have been made on TPL-based constructions logistics setups.

Table 1. Studies of construction logistics setups outsourced to TPL providers.

According to the studies presented in these project-specific and dedicated construction logistics setups operated by TPL providers improved efficiency and productivity on the construction sites (Allen et al. Citation2014; Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016; Sundquist, Gadde, and Hulthén Citation2018), managed to reduce cost (Lindén and Josephson Citation2013), but most importantly the TPL providers contributed with their logistics knowledge and competence (Lindén and Josephson Citation2013; Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016; Sundquist, Gadde, and Hulthén Citation2018; Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019). The TPL provider in these types of construction logistics setups, therefore, seems to fulfil the role of the materials coordinator advocated by Agapiou, Clausen, et al. (Citation1998).

All studies in analyse construction logistics setups with a main focus on the construction site. However, Sundquist, Gadde, and Hulthén (Citation2018) is the only study that also study how these types of construction logistics setups affect the upstream actors of the construction supply chain. The upstream actors do not benefit from the logistics setups as the downstream actors working at the construction site. This is confirmed by Dubois, Hulthén, and Sundquist (Citation2019) who found that on-site construction logistics setups induced lower efficiency in the construction supply chain compared to traditional on-site logistics handling. Hence, there is a need to further study suppliers and transport service providers and how they are affected when logistics operations are outsourced to TPL providers in terms of construction logistics setups.

Suppliers and transport service providers in the construction industry

Frödell (Citation2014) shows that procurement strategies are disconnected from how operations are performed at site, manifesting the ineffective purchasing procedures in construction. Suppliers and materials are typically procured on lowest price resulting in high total acquisition cost of materials (Agapiou, Flanagan, et al. Citation1998; Vrijhoef and Koskela Citation2000). Vrijhoef and Koskela (Citation2000) exemplify that materials purchased based on lowest price lead to very high handling and logistics costs, varying between 40 and 250% of the materials purchase price. The suppliers have to be flexible to cope with last minute orders due to lack of inventory control and poor storage capacity on the construction sites; a service appreciated by the contractors, but involves negative consequences for the suppliers in terms of planning their business and operations (Frödell Citation2011, Citation2014; Vidalakis and Sommerville Citation2013). At the same time the delivery performance of the suppliers in the construction industry is rather poor (Thunberg and Persson Citation2013), which is rooted in both the management of construction projects and in poor supply chain planning (Thunberg and Fredriksson Citation2018; Thunberg, Rudberg, and Karrbom Gustavsson Citation2017).

A challenge for the suppliers is to balance customer responsiveness and loading efficiency by consolidating deliveries to reduce transportation costs. Transportation costs are significant for the suppliers, therefore addressing transportation efficiency can result in decreased costs for the suppliers and reduced total acquisition cost of materials (Vidalakis and Sommerville Citation2013). Transports in the construction supply chain are typically of two types. One type is contracts with suppliers that include transport in the purchasing price of the material with deliveries the day after the order is placed by a transport service provider. The consequence is that several orders can be placed by many contractors without any coordination, resulting in several deliveries to the same construction site. The other type of transport is to focus on full truck loads, maximising the loading of trucks. This often results in large quantities of materials and unnecessary moving and handling of materials. There is also an increased risk of the materials being forgotten or stolen (Dubois, Hulthén, and Sundquist Citation2019).

In order for the total acquisition cost to be reduced, contractors have to develop better relations with the suppliers (Akintoye, McIntosh, and Fitzgerald Citation2000; Vidalakis and Sommerville Citation2013). This could be done if suppliers cooperated with designers and architects in earlier stages of construction projects. The suppliers and manufacturers have a lot of knowledge about the components and possess a large innovation potential that is not utilised (Martinsuo and Sariola Citation2015). There is also a potential of letting suppliers and manufacturers perform value-adding services (Huttu and Martinsuo Citation2015), in line with the third role of SCM in construction (Vrijhoef and Koskela Citation2000). However, problems in the construction supply chain often have their origin in early stages of the construction projects and include problems related to material flow, communication and project complexities. This could be mitigated with better planning of projects and through better cooperation with supply chain actors (Thunberg and Fredriksson Citation2018; Thunberg, Rudberg, and Karrbom Gustavsson Citation2017), which affect suppliers and transport service providers no matter how far they have come in their efforts of becoming supply chain oriented (Bankvall et al. Citation2010). By involving suppliers early in the design phase, the construction projects can take advantage of the suppliers’ competence and reduce problems on the construction site (Agapiou, Flanagan, et al. Citation1998; Sariola and Martinsuo Citation2016; Thunberg, Rudberg, and Karrbom Gustavsson Citation2017; Sariola Citation2018; Thunberg and Fredriksson Citation2018).

Frödell (Citation2011) found that in order to develop contractor-supplier relationships a number of aspects must be addressed, including trust, long-term commitment, core values, professionalism and willingness to collaboration. This is similar to construction supply chain maturity models presented by other scholars, which include, e.g., trust, collaboration, communication and joint objectives (Meng Citation2010; Meng, Sun, and Jones Citation2011). These suggestions echo the model by Mentzer et al. (Citation2001), presented in , and Thunberg, Rudberg, and Karrbom Gustavsson (Citation2017) conclude that the actors in the construction supply chain must address the antecedents of SCO in order for SCM to be adopted in construction.

Method

Research approach

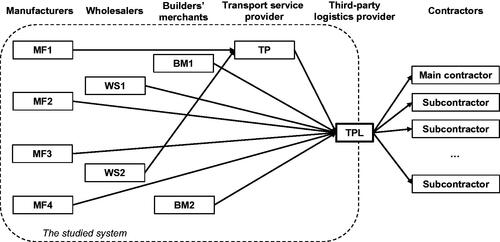

To answer the research questions, a case study approach was used (Yin Citation2014) employing a single case study of suppliers (manufacturers, wholesalers, and builders’ merchants) and a transport service provider, i.e. upstream actors in the construction supply chain. The suppliers and transport service provider deliver to a large construction project that utilised a dedicated and project-specific construction logistics setup operated by a TPL provider to manage all the logistics on the construction site. provides a schematic overview of the studied part of the supply chain and the actors included in the case study. Case studies are regarded a good method for studying new phenomena in exploratory research (Voss Citation2009). The use of a single case study is motivated by that the project is revelatory (Yin Citation2014; Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007) and offered a unique opportunity for in-depth understanding of a construction logistics setup outsourced to a TPL provider and how it affects suppliers and transport service providers (Eisenhardt Citation1989; Flyvbjerg Citation2006; Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007).

The suppliers and the transport service provider included in the study represent different types of upstream actors in the construction project supply chain, including deliveries of both project-specific and generic types of materials. The studied actors are divided into four categories: manufacturers (MFs), wholesalers (WSs), builders’ merchants (BMs) and transport service provider (TP), as indicated in . provides an overview of the upstream actors participating in the case study.

Table 2. Description of suppliers and transport service providers participating in the case study.

Data collection and analysis

Data have been collected during a period of 2.5 years, between autumn 2013 and spring 2015. The primary data sources have been a total of 14 semi-structured interviews. The interviews have been carried out with managers at the client (two interviews), managers at the TPL provider (three interviews) and with managers at the suppliers and transport service provider (nine interviews). The interviews typically lasted between 1 and 1.5 h, and when necessary clarifications and follow-up questions were asked by e-mail or by phone. All interviews were based on an interview guide concerning the topics of logistics operations in general and in construction projects, the specific project and the construction logistics setup used in the project, as well as effects the respondents had experienced as a result of the construction logistics setups. is a summary of the interview guide, illustrating the interview themes and key issues that were discussed. The interview guide was adapted to each respondent, who also brought up additional topics of their own.

Table 3. Structure of the interview guide with themes and key issues discussed.

Observations and site visits were also an important data source in order to understand how materials and orders were handled, loaded and unloaded by the different upstream actors. In addition, secondary data sources included review of project documents (including internal policies, meeting protocols and external project audits), information on actors’ webpages, informal conversations, and master thesis reports. See for summary of case study information.

Table 4. Case study information.

The aim of all research is to build new theory (Meredith Citation1993) and an explorative study can be seen as the first step towards building new theory by providing conceptual description, philosophical conceptualisation as well as taxonomies and typologies (Meredith Citation1993). Meredith (Citation2001) suggests that theory-building is an iterative process in three steps that starts with description and explanation of the studied phenomenon, building of conceptual constructs and models, and ends with verification and validation of the models. The iterative process continues over and over until the models are refined and can be presented as new theory. However, since this study is of explorative nature, we do not claim nor aim to present neither validated conceptual models nor new theory. The aim is to describe and explain a new phenomenon and can be seen as the initial step in the iteration process towards new theory.

The analysis of the collected data was done through a conceptual analysis. In conceptual analysis it is common to combine empirical and analytical research approaches to provide new insights into a new phenomenon through logical reasoning (Wacker Citation1998). In the analysis the collected data is analysed by comparing the upstream actors’ different perspectives on the attitudes towards the use of TPL (RQ1) and experienced effects from using a TPL provider in a construction project (RQ2). The suppliers’ and transport service provider’s level of supply chain orientation (RQ3) is also analysed. Finally, although the single case study only provides a limited data set, an attempt to investigate the possible moderating effects from the attitudes (RQ1) and the level of SCO (RQ3) on the experienced effects (RQ2) is investigated. A similar attempt is also made concerning the relation between the attitudes (RQ1) and the level of SCO (RQ3).

In practice, the analysis has been done through coding and interpretation of interviews and other data sources. Regarding attitudes and effects, the data is based on the respondents’ answers. The level of SCO is assessed based on a combination of interviews and other data sources and thereafter interpreted as to how the data compares to the eight antecedents needed to have an SCO (Mentzer et al. Citation2001). Both authors have been involved in the analysis, and the coding and interpretation of data have been an iterative process in the analysis phase of the study.

Case description

In the construction project, several contractors were working alongside the fully operative hospital, inducing thousands of transports to and from the construction site. Due to the large amount of deliveries and the complex environment with a fully operative hospital, the client decided to outsource the logistics and materials handling to a TPL provider specialised towards the construction industry; the main driving force was to not disturb hospital operations.

The TPL provider set up a project-specific logistics setup that was mandatory to use for all contractors involved in the construction project. To avert the traffic and keep them from disturbing the hospital operations and ambulance traffic, all deliveries were directed to a checkpoint operated by the TPL provider. Gatekeepers posted around the site made sure that no deliveries entered without permission and that no ambulances were held up. During daytime, only some special arranged deliveries, and deliveries with materials for the loadbearing structure, such as concrete reinforcements and prefabricated concrete elements, were allowed to enter the construction site. All other materials used in the construction project were brought in between 4 pm and midnight by the TPL provider when the contractors had stopped working for the day.

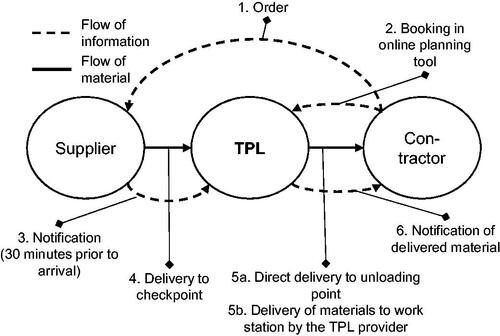

The TPL provider established directives for deliveries, such as maximum pallet size and weight, packaging and labelling of arriving materials. The TPL provider did not have any contact with the suppliers; it was up to the contractors to inform their suppliers of the directives on how the materials were to be delivered. The contractors were not allowed to store more materials than what was needed for immediate production at the site. shows the prescribed process of how materials were ordered and delivered to the construction site. A contractor placed an order at their supplier, then the contractor booked the planned delivery in an online planning tool provided by the TPL provider no later than five days before the delivery was planned to arrive. Simultaneously they booked how long the time slot for unloading should be, information about the delivery (e.g. number of pallets, size of pallets, type of material, etc.) and resources needed to unload the delivery (e.g. forklifts or cranes). Neither the suppliers nor the transport service providers had access to the online planning tool; it was up to the contractors to inform their suppliers of when (both date and time slot) the deliveries were to arrive. The suppliers in turn had to notify the contractors when the deliveries were on route together with relevant information such as the number of pallets.

Figure 3. The prescribed process of ordering, booking and delivering materials to the construction project (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016). The numbers indicate in which order the activities occur.

When the delivery had approximately 30 min left until arrival, the driver of the delivery notified the TPL provider who then could act on the information, e.g. hold the delivery if there was an ambulance incoming or any problems in production that could cause problems with accepting incoming goods. When the delivery arrived, the TPL provider inspected the material and logged any deficiencies. For daytime deliveries, the TPL provider directed the delivery trucks to the right unloading location. For deliveries arriving after 4 pm, personnel from the TPL provider unloaded and delivered the material to the contractors’ workstations. Finally, the TPL provider notified the contractor that the delivery had arrived, any deficiencies, and that the materials were delivered.

Case study findings

Manufacturers

All of the manufacturers (MF1-4) were either positive or neutral to the use of a dedicated construction logistics setup in the construction project. However, they had opinions on the particular setup used in the studied construction project. The construction logistics setup with deliveries at evenings and strict policies was perceived to benefit the contractors rather than the manufacturers. MF4 was the manufacturer of the prefabricated concrete elements used for the loadbearing structure and also the contractor responsible for the loadbearing structure, hence they ‘delivered to themselves’. All of their deliveries arrived during daytime at a very early stage in the project and they did not utilise any of the materials handling services the construction logistics setup provided.

All manufacturers highlighted the lack of a terminal for interim storage in the construction logistics setup, however, all manufacturers except MF3 arranged interim storages (by themselves, at their suppliers, or through their transport service provider). Both MF2 and MF3 expressed discontent with deliveries in the evenings, since it forced them to change their business models, which induced extra costs. Deliveries after 4 pm are not industry standard, which limited the possibility for their transport service providers to find alternative goods to load their vehicles on the return route. MF2 also expressed that the prescribed order process was not ideal, e.g. MF2 had to contact the contractor when they were ready to deliver, then the contractor could book a timeslot in the online planning tool, and then had to notify MF2 when to deliver. MF1 recognised positive effects and estimated that the construction logistics setup saved costs thanks to the well-defined policies and from possibilities to track orders and deliveries.

All manufacturers discussed and recognised logistics as an important issue to deal with in the construction industry. Slot times and dedicated logistics setups were something the manufacturers had encountered before and predicted to be more common in the future. Their past experience made them contact the TPL provider before the construction project start-up to get necessary information on the construction logistics setup. MF3 was open for developing their business model in order to adapt to a new paradigm, and would have liked to see increased knowledge of SCM in the industry at large.

Wholesalers

The wholesalers (WS1-2) were positive to the construction logistics setup and highlighted the dedicated resources used for unloading deliveries. They could trust that materials were taken care of in a proper manner, something they were not used to in the construction industry. Both wholesalers contacted the TPL provider at an early stage in the project to be informed about the setup of the construction logistics setup used in the project. WS1 used experience from other construction logistics setups and reassured their customers that the construction logistics setup in the project would not affect their service level or commitments towards them.

The two wholesalers worked differently with deliveries. WS1 delivered in own trucks and used a local warehouse to consolidate their deliveries. WS2 bought both daytime and evening transports from TP, with whom they had a close collaboration. The ‘slotted’ delivery plan and evening deliveries induced extra costs for both wholesalers. The extra costs were forwarded to the contractors who were not prepared that the construction logistics setup would induce extra costs on them. WS2 expressed that the construction logistics setup caused extra planning for all parties involved, resulting in that the contractors made fewer last-minute orders. This enabled the wholesalers to plan ahead with their suppliers as well.

Both WS1 and WS2 were actively working with logistics management and used it in their marketing strategies. Their business models were to sell a whole concept and solve the materials delivery as smoothly as possible so that the contractors can focus on production. WS2 was open with that they are not the cheapest supplier but emphasised that the contractors must look at total acquisition cost and not on price when purchasing materials. Both wholesalers also offered construction logistics setups of their own with materials handling. At the same time, they had adapted to the construction industry culture and accepted last-minute orders with express delivery.

Builders’ merchants

Both builders’ merchants (BM1-2) expressed that the TPL setup was well defined and easy to follow, leading to a better than average construction project when it came to logistics. They had both daytime and evening deliveries and noticed that the contractors were able to add last-minute orders to be delivered the same day, as long as they had a booked timeslot. Their main concerns were detailed parts of the construction logistics setup, such as the size of the checkpoint and the rigidity in the online planning tool concerning that orders had to be placed five days ahead of delivery. Both builders’ merchants also considered that some of the policies stipulated by the TPL provider where counterproductive from a total project perspective. The policies according to the builders’ merchants rather guaranteed efficient operations for the TPL provider than for the construction project.

Both builders’ merchants adapted their business models to be able to serve the construction project as profitable as possible by minimising the number of deliveries. Deliveries during the evenings were new to them and induced extra costs. The profit margins from materials were already low and deliveries were charged at a fixed price. However, BM1 was able to charge extra for evening deliveries. Both builders’ merchants were forced to have time buffers on deliveries due to queues and waiting times at the checkpoint, which also had ripple effects on deliveries to other construction projects they supplied. Both builders’ merchants stated that there were fewer deliveries than usual for comparable projects and that the hedging on materials was down to 10% instead of normal 20%, which they attributed to better planning by the contractors as a result of the directives of the construction logistics setup.

The builders’ merchants perceived themselves as key players in the construction supply chain, functioning as materials storage for the contractors. Their role was to serve the construction projects so that the contractors and construction workers could focus on production. They served the industry by being flexible and able to deliver last-minute orders in own trucks with cranes, able unload themselves and did therefore not need any extra resources for unloading. They did also express that it would be an advantage if architects and designers involved them in earlier stages of construction projects to better utilise their knowledge about materials’ standards.

Transport service provider

The transport service provider (TP) was positive to the construction logistics setup, but in their opinion the construction logistics setup could have been better. Instead of a small checkpoint placed at the construction site, they advocated for a larger terminal further away from the construction site, with trucks and trailers feeding the construction project with consolidated deliveries. They perceived the construction logistics setup as too complicated, with materials first arriving to TP’s terminal and then to be delivered to the construction project. TP was also negative towards the fact that several contractors had made deals with small transport service providers that often found ways to sidestep the rigid policies. In their view, these deals undermined the construction logistics setup and favoured the smaller transport service providers.

The use of the construction logistics setup made TP’s work easier to perform compared to traditional construction projects, especially in terms of the dedicated resources for unloading and the well-defined policies on how deliveries were to be made. However, because the timeslots were booked with the suppliers by the contractors, TP were not able to consolidate and optimise the loading of the trucks and had to deliver several times a day. Also, if they noticed that the booked time slots were not adjusted to the actual number of pallets, they themselves could not book, or adjust, the time slots or the delivery information in the on-line planning tool. In total, TP considered that due to the large number of deliveries, the construction logistics setup induced a small increase in their profit.

TP had long experience of working with the construction industry and actively tried to reform the industry. One example was their own effort of using their terminals as a construction logistics setup of their own. They had a close collaboration with WS2 and together with them they visited constructions sites and planned for suitable areas for unloading.

Case analysis

The case analysis is structured according to the three research questions and is then summarised in .

Table 5. Attitudes towards, and effects from, the construction logistics setup, as well as the level of SCO.

Attitudes towards the use of TPL

In the study by Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016), analysing the same construction logistics setup from a contractor and client perspective, contractors argued that suppliers and transport providers were negative to the construction logistics setup. However, taking the perspective of suppliers and transport service providers give a different notion. None of the studied supply chain actors were negative towards the construction logistics setup; however, they had opinions about it. These opinions can be traced back to how the construction logistics setup was set up. JIT deliveries are becoming more common in the construction industry, but deliveries during evenings and nights are not common. This caused extra work for the suppliers in the form of extra planning. It could also induce extra costs if the transport service provider a supplier used could not find any goods to backhaul.

The time regulation of booking deliveries in the online planning tool five days prior to arrival caused annoyance among the suppliers and the transport service provider. They did not expect the regulations to be as strict as they were and they also lacked the possibility to book deliveries by themselves and therefore had to go through the contractors. All suppliers considered that the TPL provider should have been more flexible and that they should have focussed more on aiding the construction work made on site.

The regulations on how to pack materials were also in certain cases deemed as inflexible. As an example, MF3 delivered long ventilation shafts that needed specialised pallets. At first it was not possible for the TPL provider to send the pallets back to MF3, which would have meant that MF3 had been forced to manufacture new pallets for every delivery. However, MF3 and the TPL provider managed to resolve this issue.

MF2 and MF3 had a more neutral attitude towards the construction logistics setup compared to the other companies participating in the study that were positive. The reason behind their neutral attitude is linked to their position in the supply chain. They are the two companies furthest away from the construction site and therefore interact the least with the construction logistics setup of the nine interviewed companies. Their focus as manufacturers is on their products. They are used to traditional construction projects where they can deliver their products with as little effort as possible.

Experienced effects from the use of TPL

The judgement on experienced effects derives directly from what the respondents reported in the interviews. Therefore, the effects are only based on the respondents’ opinions. The most significant effects of the construction logistics setup for the suppliers and the transport provider are the increased costs as well as increased planning efforts. However, in many cases the increased costs were forwarded to the contractors and therefore the impact can be said to be moderate. The increased planning efforts are hard to judge, since they can be both positive and negative for the suppliers. Since the construction logistics setup introduced new delivery procedures compared to what the suppliers are used to, an increase in planning efforts can be seen as a logical consequence. If the planning has led to decreased number of deliveries, less last-minute orders and decreased waste, then it is a clear positive effect.

BM1 and BM2 report that there was a significant reduction in waste of materials. The builders’ merchants sell typical standardised construction materials such as drywalls, nails, wood, etc. These types of construction materials are used in most construction projects wherefore the builders’ merchants can compare the amount of construction materials ordered and delivered. The exact reduction has to be considered with care since this information is not checked with the contractors. MF2 reported an increase in waste of materials. This is traced back to a delivery that got lost somewhere in the delivery process and MF2 had to cover the cost by themselves. However, even if this may be caused by a delivery process that MF2 is not used to, it is hard to directly pin the loss of material as caused by the construction logistics setup.

Both builders’ merchants report a reduction in the number of deliveries to the construction site. This is partly caused by the reduction in waste of materials, i.e. less material delivered means fewer deliveries. BM1 also changed their business model due to the size of the construction project and arranged so that all deliveries were made from the central warehouse. They also made sure to co-load as many deliveries as possible. BM2 arranged it so that when their transport provider was about to deliver plasterboards directly from the manufacturer, the transport provider also stopped by the warehouse and picked up additional materials that were to be delivered. TP report an increase in the number of deliveries compared to a traditional construction project. However, in the studied construction project many suppliers utilised TP’s terminal as an interim storage and TP had daily deliveries to the construction site. Both MF1 and WS2 are examples of companies that utilised TP in this way. Some of those deliveries were allowed to enter during daytime and TP then delivered the material to the checkpoint and the contractors had to go there by themselves to pick it up. The increase in deliveries was not of a direct concern for TP; on the contrary it is within their core business and more deliveries meant that they could bill more.

Other types of experienced effects are traced back to the organising of the construction logistics setup. As depicted in , the TPL provider did not have any contact with the suppliers, apart from meetings with some of the suppliers in the start-up of the construction project. The suppliers perceived this as cumbersome and it would have been easier if they had access to the TPL provider’s online booking system. This can be interpreted as increased bureaucracy. Furthermore, did the lack of a terminal induce some of the other effects, such as increased cost since several suppliers had to manage own warehouses for interim storage.

The level of SCO

Within the limits of relatively few interviews and the single case setting, the evaluation is based on the eight antecedents identified in Mentzer et al. (Citation2001). Assessing the suppliers’ and the transport service provider’s level of SCO, i.e. how many antecedents they have addressed, provide an estimation of their readiness towards the adoption of SCM, which is based on information from the interviews. It is the level of SCO that is of interest as a measurement of SCM maturity level, not what specific antecedent each company is considered to have addressed. However, all participating suppliers and the transport service provider are considered to have addressed vision in their progress of becoming supply chain oriented. This assessment is based on that all participating companies express that they consider logistics to be important.

WS1, WS2 and TP are considered to have high levels of SCO and to have addressed all eight antecedents, a result of their work with reforming the construction industry. Logistics and timely deliveries are core competences for these companies, wherefore they actively try to introduce SCM in the industry. An example of this is that all three companies already provide or are developing construction logistics setups of their own. Similarly, BM1 and BM2 regard logistics important, but their product portfolio is rather standardised and their willingness to serve the contractors limits their ambitions concerning logistics. Since both builders’ merchants are local franchisers of larger chains, they are too small to be proactive and the profit margins of standardised construction materials are also low. This hampers them in the procurement negotiations with the contractors since they are afraid of losing the contractors as customers. They have become victims of the traditional culture in the construction industry.

The manufacturers tend to have a low level of SCO and are also furthest from the construction site in the construction supply chain. Hence, they are very product oriented and not aware of logistics problems at site, with the exception of MF4 who also is a contractor that makes the assessment of MF4’s level of SCO more complicated. The manufacturers also leave the responsibility for delivery and logistics to the transport service providers, wherefore SCM is not at the core of their business. One exception is MF1 who designs products specifically for each project and was therefore more involved in the construction process, leading to that they also focus more on logistics issues and are considered to have a higher level of SCO.

Summary of analysis

provides a summary of the findings in the case study categorised by the corresponding RQs. From it can be identified that companies with a positive attitude towards the construction logistics setup have been assessed to have a higher level of SCO, except for MF4. However, since MF4 is also a contractor, their positive attitude can be traced back to how the construction logistics setup has worked in their favour at the construction site. All companies in the study express that the construction logistics setup focuses more on the construction site and therefore is of greater benefit for the contractors.

All the companies with a positive attitude worked closely with the construction logistics setup and saw the benefits it can have. Companies with a higher level of SCO will more likely have a positive attitude towards logistics and SCM initiatives. The positive attitudes towards the construction logistics setup can also be derived from how the construction logistics setup did bridge the supply chain and the construction site. There were always resources available to receive the arriving deliveries and the companies could feel secure about them being taken care of in a proper manner. MF2 and MF3 were too far away from the construction site and could not experience how the construction logistics setup established an interface between the construction site and the supply chain. They were not used to the extent of regulations on how and when to deliver materials and this affected their attitude towards the setup. However, at least MF3 was open to change their business model to adapt to logistics setups in the future, which meant that the construction logistics setup did affect their perception of SCM and logistics setups.

The attitude towards the construction logistics setup and the level SCO do not affect the experienced effects per se. As an example, most suppliers experience increased costs despite if they have a positive attitude or what their level of SCO is. However, the attitude may affect how the suppliers and TP perceive the experienced effects. A company with negative attitude will most likely view effects such as increased cost as troublesome. This will in turn strengthen the company’s negative attitude towards the construction logistics setup. The increased cost and planning efforts induced by the setup did not obstruct most of the suppliers’ attitude towards the construction logistics setup. On the contrary increased planning was often seen as good and as a consequence of the contractors increased planning. The increased cost could many times be forwarded to the contractors and did therefore not affect them that much. A higher level of SCO can also bring an understanding that it is not the cost itself that is important or a problem. The cost is rather a price that has to be paid in order for the success of the construction logistics setup and for the actors in the supply chain to share. WS1 and WS2 are good examples of how a high level of SCO inflicts how they perceive the experienced effects. Their high level of SCO is manifested in their business model; they are not the cheapest suppliers and they sell a whole concept. This can inflict higher costs and increased planning, but instead it brings benefits for their customers and other actors in their supply chains.

Discussion

The following section discusses the attitudes and experienced effects, the supply chain orientation and the possibility of a TPL provider to act as a systems integrator in the construction supply chain.

Attitudes and experienced effects

The construction logistics setup established an interface between the supply chain and the construction site (Vrijhoef and Koskela’s (Citation2000) first role), which was also found in Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016). However, the suppliers found the construction logistics setup to benefit the contractors more and it was therefore in some cases found to be cumbersome to use. This is consistent with the conclusions in Sundquist, Gadde, and Hulthén (Citation2018) and Dubois, Hulthén, and Sundquist (Citation2019). The TPL provider should have included the suppliers and transport providers more in the process of determining the delivery process, policies and regulation. In such a case the experienced effects, presented in , might have been different. The suppliers could then prepare their work better and thereby avoid the extra costs. The need to integrate the construction logistics setup with upstream tiers is important in order for more suppliers to see the benefits with them. As a logistics partnership it should benefit all participating parties as far as possible. A construction logistics setup with the possibility to store materials, such as the ones reported by Hedborg Bengtsson (Citation2019) and Janné and Fredriksson (Citation2019), would probably have reduced some of the critique regarding these issues.

Three of the studied companies (WS1, WS2 and TP) have, or are developing, construction logistics setups aimed for the construction industry. This indicates that logistics are at the core of their businesses and that they have identified a need for dedicated and specialised construction logistics setups in the construction industry. It is reasonable to assume that a supplier driven construction logistics setup would be different compared to the setup in this study in that it would focus more on the supply chain rather than on the construction site. Thereby it would fulfil the second role described by Vrijhoef and Koskela (Citation2000). However, there are issues with a supplier driven construction logistics setup that must be resolved, such as how it would handle deliveries from other suppliers and direct competitors.

As shown in Lindén and Josephson (Citation2013), Sobotka and Czarnigowska (Citation2005) and Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016) costs can be reduced when the logistics handling is outsourced. However, these studies focus on the contractor perspective and show that the contractors experienced total costs effect depends very much on how well they manage to exploit the possible benefits from the construction logistics setup. The effects should also be considered on an aggregated level, taking the effect on total acquisition cost for the suppliers and transport service providers into account and thereby include the entire supply chain.

Increased costs and planning are the most common experienced effects for the upstream actors. Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016) report that construction logistics setups lead to increased planning, that in turn lead to a positive outcome for the contractors in the form of reductions in workforce. An increase in planning is to be expected when the upstream actors have to adapt to new way of working. If it led to positive outcomes is inconclusive, but it probably contributed to reducing costs. Taking a supply chain perspective Vidalakis and Sommerville (Citation2013) show that the cost of transportation is a large expense for the suppliers and it is therefore in their interest to reduce the number of transports and make them more efficient, which should be taken into account when setting up a construction logistics setup.

Supply chain orientation

The participating companies in this study were divided into four categories: manufacturers, wholesalers, builders’ merchants and transport service provider. The level of SCO has been found to be different for the different categories with largest varieties for the manufacturers. The manufacturers are very different companies in terms of products, economic power and organisational compatibility. All of them focus on their products first and logistics is a secondary concern. A common denominator between the manufacturers in this study is that they all deliver unique, non-standardised products. All these factors can partly explain the manufacturers’ different levels of SCO.

Logistics is the core business for transport service providers and for a very large transport service provider such as TP who provide several logistics services it would be peculiar if they did not have a high level of SCO. However, not all transport service providers are as large as TP and in the construction industry several smaller transport service providers are used. For them a high level of SCO is not necessarily as important as it is for TP.

The wholesalers also had a very high level of SCO. This is a result of their efforts towards SCM and logistics. They strive to change how the construction industry works with ordering and supplying materials and more and more of the orders they receive are made online. Both WS1 and WS2 also deliver materials to other industry sectors than construction and many of those industries have come further in the adoption of SCM and logistics compared to the construction industry. This affected WS1 and WS2 in a positive direction towards SCM. Where the wholesalers use their size and experience from other industries as leverage, do the lack of size and experience from other industries the opposite for the builders’ merchants. They are local franchisers and supply construction projects with standardised materials, wherefore they work closely with the contractors. However, the competition between different builders’ merchants is fierce and the profit margins are low. Hence, they have to offer last minute orders and other services to the contractors in order to be competitive (Vidalakis and Sommerville Citation2013; Frödell Citation2014). This hinders them from addressing all the eight antecedents if the contractors are not willing to do the same.

Altogether the suppliers and transport service provider can be said to have a rather high level of SCO indicating that they have a willingness to address the necessary issues needed to adopt SCM (Mentzer et al. Citation2001). This is also supported by the general positive attitude towards the construction logistics setup.

TPL provider as a systems integrator

The construction logistics setup was clearly designed to benefit the construction project and the actors working at the construction site. However, as emphasised by Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016) a construction logistics setup is a support function to a construction project, but could also act as a supply chain integrator and materials coordinator (Agapiou, Clausen, et al. Citation1998). The TPL provider in this case had a golden opportunity to take the role of a supply chain integrator and a materials coordinator (Agapiou, Clausen, et al. Citation1998), thereby facilitating the fourth role of SCM in construction (Vrijhoef and Koskela Citation2000).

The TPL provider’s level of SCO is also something that needs to be discussed and studied further. For instance, it is clear that it was not committed to include the upstream tiers based on how the construction logistics setup was organised. It is also doubtful that it had organisational capability of doing that. However, that may come down to how the construction industry is organised; in temporary organisations and as a loosely coupled system with small or no interaction between actors and projects (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002).

Furthermore, the incentive for the client in this study to outsource the construction logistics, was not to improve SCM nor to integrate the supply chain actors. It was to avoid disturbance of the hospital’s operations and in this aspect the construction logistics setup was a success. However, clients have to realise that such initiatives will affect the all actors of the supply chain; by addressing the antecedents of becoming supply chain oriented, construction logistics setups will more likely benefit both the construction project as well as the construction supply chain.

The construction logistics setup in this case mainly focussed on establishing an interface between the supply chain and the construction site in accordance with Vrijhoef and Koskela’s (Citation2000) first role and also on logistics at the construction site, which Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016) identified as an additional role for logistics and SCM to play in construction.

Conclusions

With the exception of Sundquist, Gadde, and Hulthén (Citation2018), previous studies on construction logistics setups outsourced to TPL providers (see ) have mainly focussed on the downstream tiers, i.e. the contractors and the other actors on the construction site. This study has turned the perspective by focussing only on the upstream tiers and contributes with insight on the upstream tiers’ attitudes and experiences from a construction logistics setup. Since TPL can be seen as a logistics partnership (Skjoett-Larsen Citation2000) it is natural to also include the upstream tiers. This is mainly a critique against the contractors and the TPL provider that do need to integrate suppliers and transport providers more. The sharing of risks and rewards are one of the key components of SCM (Mentzer et al. Citation2001).

The three research questions that were developed from the purpose are answered in and the following discussion. The suppliers and transport service providers have in this study been found to be positive towards construction logistics setups as an improvement of the logistics in the construction industry (RQ1). The experience effects (RQ2) differs between the different actors in the supply chain, but are in general positive. Similarly, also the level of supply chain orientation (RQ3) also differ between the actors, but the study reveals that upstream actors in the supply chain generally are more mature when it comes to logistics and SCM than what the downstream actors are (i.e. contractors and clients).

Contribution with study

The main contribution with this study is that it provides knowledge of how construction logistics setups operated by TPL providers affect upstream actors. This study shows that the upstream actors are positive towards construction logistics setups, despite that the effects seems to benefit the downstream actors, i.e. clients and contractors, rather than the upstream actors. The study also shows that the TPL provider fails to become a systems integrator if the upstream actors in the supply chain is not integrated in the construction logistics setup.

Furthermore, the study shows that the upstream actors generally have a rather high level of SCO and are therefore well prepared to initiatives that rely on SCM principles. The upstream actors also appear to be more mature when it comes to logistics and SCM. Even though the assessment of the suppliers’ level of SCO must be treated with care and within the limits of generalisability of this study. The positive attitude together with a high maturity of SCM is something that enables for developing these kinds of setups further, together with suppliers and transport service providers, utilising their competence as suggested by Huttu and Martinsuo (Citation2015) and Martinsuo and Sariola (Citation2015).

Limitations and ideas for future research

The methodological choices made in this study have implications on generalisability. The study is grounded in a single case study of a construction project. It is therefore difficult to state that the findings will apply to other contexts. However, the single case study offered a unique opportunity to study the phenomenon of dedicated and project specific construction logistics setups operated by TPL providers and how they affect the upstream actors of the supply chain. Other studies of similar logistics setups are however needed in order to verify the results.

Furthermore, the analysis is a conceptual analysis and the data collection methods have been qualitative. This means that reported effects and level of SCO are based on the authors’ interpretation of the interviews and other data sources. Further studies are needed in order to confirm how these types of construction logistics setups affect the upstream actors and how they deal with SCO in order to adopt SCM.

The client’s responsibility as the initiator of the construction logistics setup also has to be considered. The client has to realise that initiatives such as outsourcing logistics on the construction site to a TPL provider will affect the actors in the construction supply chain. Further studies on the clients’ strategic intent and how clients consider the implications for both the project as well as the extended network is needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andreas Ekeskär

Andreas Ekeskär is a PhD student in construction management within the School of Architecture and the Built Environment at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden. Prior to becoming a PhD student, he worked as a construction project manager for the City of Stockholm. He has also worked as a logistics specialist for the consultancy firm WSP. His current research interests are in third-party logistics in construction and inter-organisational relationships between different actors in the construction industry. He has previously been published in Construction Management and Economics.

Martin Rudberg

Martin Rudberg holds the L E Lundberg Chair in Construction Management and Logistics at Linköping University in Norrköping, Sweden, and manages a group that conducts research and teaching within construction logistics and construction supply chain management. His main research interests reside within the areas of digitalisation, supply chain planning, production strategy and supply chain management in construction. Professor Rudberg currently leads one of Sweden’s largest research initiatives on digitalisation in construction within the strategic innovation programme Smart Built Environment.

References

- Agapiou, A., L. E. Clausen, R. Flanagan, G. Norman, and D. Notman. 1998. “The Role of Logistics in the Materials Flow Control Process.” Construction Management & Economics 16 (2): 131–137.

- Agapiou, Andrew, Roger Flanagan, George Norman, and David Notman. 1998. “The Changing Role of Builders Merchants in the Construction Supply Chain.” Construction Management and Economics 16 (3): 351–361.

- Akbari, Mohammadreza. 2018. “Logistics Outsourcing: A Structured Literature Review.” Benchmarking: An International Journal 25 (5): 1548–1580.

- Akintoye, A., G. McIntosh, and E. Fitzgerald. 2000. “A Survey of Supply Chain Collaboration and Management in the UK Construction Industry.” European Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 6 (3–4): 159–168.

- Allen, Julian, Michael Browne, Allan Woodburn, and Jacques Leonardi. 2014. “A Review of Urban Consolidation Centres in the Supply Chain Based on a Case Study Approach.” Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal 15 (4): 100–112.

- Aloini, Davide, Riccardo Dulmin, Valeria Mininno, and Simone Ponticelli. 2012. “Supply Chain Management: A Review of Implementation Risks in the Construction Industry.” Business Process Management Journal 18 (5): 735–761.

- Bakker, René M. 2010. “Taking Stock of Temporary Organizational Forms: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda.” International Journal of Management Reviews 12 (4): 466–486.

- Bankvall, Lars, Lena E. Bygballe, Anna Dubois, and Marianne Jahre. 2010. “Interdependence in Supply Chains and Projects in Construction.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 15 (5): 385–393.

- Behera, Panchanan, R. P. Mohanty, and Anand Prakash. 2015. “Understanding Construction Supply Chain Management.” Production Planning & Control 26 (16): 1332–1350.

- Bemelmans, Jeroen, Hans Voordijk, Bart Vos, and Jan Buter. 2012. “Assessing Buyer-Supplier Relationship Management: Multiple Case-Study in the Dutch Construction Industry.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 138 (1): 163–176.

- Briscoe, Geoffrey H., Andrew R. J. Dainty, Sarah J. Millett, and Richard H. Neale. 2004. “Client‐Led Strategies for Construction Supply Chain Improvement.” Construction Management and Economics 22 (2): 193–201.

- Bygballe, Lena E., and Malena Ingemansson. 2014. “The Logic of Innovation in Construction.” Industrial Marketing Management 43 (3): 512–524.

- Bygballe, Lena E., Marianne Jahre, and Anna Swärd. 2010. “Partnering Relationships in Construction: A Literature Review.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 16 (4): 239–253.

- Cox, Andrew. 2008. “Strategic Management of Construction Procurement.” In Construction Supply Chain Management Handbook, edited by William J. O'Brien, Carlos T. Formoso, Ruben Vrijhoef and Kerry A. London, 1–22. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Cox, Andrew, and Paul Ireland. 2002. “Managing Construction Supply Chains: The Common Sense Approach.” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 9 (5/6): 409–418.

- Dainty, Andrew R. J., Geoffrey H. Briscoe, and Sarah J. Millett. 2001. “Subcontractor Perspectives on Supply Chain Alliances.” Construction Management and Economics 19 (8): 841–848.

- Dubois, Anna, and Lars-Erik Gadde. 2000. “Supply Strategy and Network Effects — Purchasing Behaviour in the Construction Industry.” European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 6 (3–4): 207–215.

- Dubois, Anna, and Lars-Erik Gadde. 2002. “The Construction Industry as a Loosely Coupled System: Implications for Productivity and Innovation.” Construction Management & Economics 20 (7): 621–631.

- Dubois, Anna, Kajsa Hulthén, and Victoria Sundquist. 2019. “Organising Logistics and Transport Activities in Construction.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 30 (2): 620–640.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–550.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Melissa E. Graebner. 2007. “Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (1): 25–32.

- Ekeskär, Andreas, Malena Ingemansson Havenvid, and Tina Karrbom Gustavsson. 2019. “Horizontal Inter-Organizational Collaboration: The Case of Third-Party Logistics.” Proceedings 35th Annual ARCOM Conference, edited by C. Gorse and C. J. Neilson, Leeds, UK, 4–9 September, 821–830.