Abstract

The paper discusses innovation within the traditionally conservative legal sector as a diverse service improvement mechanism that models positive firm change. A resource-based view and practice-based view blend provided a systematic theoretical benchmark for the study. Fifty-three semi-structured interviews were conducted with law professionals from seven countries capturing their day-to-day work experiences and identifying the barriers that hinder and the opportunities that support innovation adoption in legal firms today. A data-intensive thematic analysis uncovers six core themes: human factor and culture, client and market, technology, organizational transitions, legal processes, and education. The paper contributes to the state of art by (i) contextualizing each of these themes and their diverse underpinning dimensions; (ii) developing an evidence-based conceptual framework that critically assesses legal innovation uptake barriers and opportunities; and (iii) advancing the theoretical and empirical understanding of law service operations demonstrating the rationale for legal firms to invest in technology, multidisciplinary education, and training, and to adopt leaner, hybrid and more client-driven management approaches.

1. Introduction

Legal firms face difficulties when managing their business model and trying to adapt to the rapidly changing technology and customer expectations (Giannakis et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, the deregulation of the legal sector in countries like the UK and Australia (Garoupa Citation2014) and the demise of legal aid have been the forces driving many incumbent legal firms on the verge of bankruptcy or to productivity declines (Susskind Citation2017; Clegg, Balthu, and Morris Citation2020). Legal firms also undergo pressures due to the constant entrants of new businesses, such as the alternative business structure firms (ABS). For example, in 2011, 300 applications for ABS were submitted in the UK alone (Law Society of England and Wales Citation2016) creating online-based legal suppliers promising faster and more cost-effective legal services (Gottschalk Citation2002). Furthermore, institutional changes, with one major example for the UK and the European Union being Brexit and its short and long-term consequences, may create additional barriers preventing mostly large legal firms from expanding opportunities. Other legal firms are changing too, altering their recruitment practices due to uncertainty in the qualifications of a lawyer and the overall regulations that might come into force (Hellwig Citation2017).

Nonetheless, the legal sector still makes a vital contribution to the worldwide economy, with the USA and UK legal sectors leading a dynamic global market with total annual revenues (per 2019) of $330 bn and £26 bn respectively. The legal sector thus despite its problems remains competitive and has the capacity, if led and managed more efficiently, to prosper further. A path for achieving this is by taking actions for revitalizing the sector that can optimize legal business procedures, which nowadays may be fairly dysfunctional, repetitive, or unorthodox. Knowledge transfer from other professional disciplines and in particular innovation implementation can help in enhancing the sector.

The concept of innovation can have multiple meanings across different industries but is universally considered a powerful vehicle for change. Rothaermeler described innovation as ‘the successful introduction of a new product, process, or business model that can lead to a powerful driver in the competitive processes’ (Citation2015, 199). From an operations management perspective, innovation is about the transformation of a new idea into practice for the means of creating value for the customer (Rice Citation2017; Rogers Citation2010). This paper considers innovation as a diverse legal service improvement mechanism that creates positive firm change based on technology uptake, human and social capital management, and knowledge transfer.

There are a few examples in the literature (e.g. Roper, Love, and Bourke Citation2016; Desyllas et al. Citation2018; Moore and Haji Citation2017; Bourke, Roper, and Love Citation2020) where scholars explored the role or drivers for innovation in the legal services but as a whole law is a severely under‐researched industry (Segal-Horn and Dean Citation2007). There is a scarcity of operations management research that has focussed on identifying how the legal service sector embraces innovation and to what extent this is appreciated by and influences the working lives of legal professionals. There is no thorough record of the opportunities and challenges legal firms and their professionals face when trying to increase their overall efficiency and productivity and adapt to a paradigm change for the sector that goes beyond the traditional boundaries that have defined the law profession for decades.

Through a theory borrowing and blending approach (Oswick, Fleming, and Hanlon Citation2011) that combines on the one hand resource-based view (RBV) with practice-based view (PBV), and on the other hand principles of operations management research and applied social research methods, this paper attempts to generate a revelatory multiple lenses contribution (per Nicholson et al. Citation2018) that has a twin objective. It seeks to develop an in-depth understanding of the:

key human factor elements reflecting and affecting innovation and its adoption within law firms via investigating the daily operations of legal professionals;

challenges and opportunities that may prevent or enable the efficient delivery of services and innovation adoption by law firms according to individual legal professionals.

We argue, specifically, that a systematic framework that maps the challenges and opportunities of the legal service innovation adoption process is absent. We propose to address this gap through the following. First, we advance theoretical developments that may support our understanding of the processes ‘placing’ legal service supply in a primarily RBV-based framework that incorporates additional elements of knowledge transfer and best practice exchange. We question whether a sector characterized by a high knowledge intensity, a high professionalized workforce, and a low capital intensity (Von Nordenflycht Citation2010) is maximizing, as one would expect, opportunities for continuous improvement and growth through effective innovation or it is bound to traditional conventions and resistance to change. Second, we explore the challenges adversely affecting organizational capacity, at the firm level, and workforce performance, at the employee level, by way of mapping relevant literature. Third, we provide an in-depth qualitative analysis of primary data collected after interviewing 53 law professionals in as many organizations. This empowers us to expand the empirical understanding of the enablers and barriers that facilitate or marginalize innovation as an apparatus for positive change. Finally, we present a conceptual thematic guide that contextualizes the roadblocks to legal firm innovation and highlights opportunities that may hold the keys to overcome these. Some of the identified solutions will be further explored shortly and put into a more generalizable context via a follow-up quantitative study.

The next section of the paper presents a critical summary of previous studies of relevance and the theoretical backbone of the study. This is followed by a detailed description of the methodology and data analysis employed. The main section of the paper presents the findings of our thematic analysis identifying key dimensions of the challenges and possible opportunities experienced today by legal professionals reflecting and affecting innovation adoption in the legal service sector. Themes and subthemes are analyzed in detail with the use of raw extracts from the participants’ interviews. The paper then provides a discussion section that integrates the key messages of our study and relevant recommendations for law professionals and legal project managers, working in legal service firms looking to incorporate more innovation in their current and future practice. Next comes a conclusion section and the paper ends with a section about our work’s limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature review and theoretical underpinning of the study

An important constituent of the professional service law firm is the knowledge, networks, skills, and performance that is embodied and embedded in its partners and lawyers, where purchasing idiosyncratic knowledge bases, skills, and often the experiences of legal professionals (Beaverstock Citation2004; Beaverstock, Taylor, and Smith Citation1999; Bourke, Roper, and Love Citation2020). Significant changes in technology, client sophistication, and general resistance to change have brought the tenuous viability and effectiveness of the traditional law firm business model in need of a paradigmatic shift (Moore and Haji Citation2017). Operations issues concerning the system, technology, human resource management, and knowledge transformation are critical for legal service delivery (Segal-Horn and Dean Citation2007; Clegg, Balthu, and Morris Citation2020) and we hypothesize that underpin the process of accomplishing this shift. The tools currently used by the law sector to manage knowledge, however, are fragmented and rudimentary at best; thus law firms could benefit immensely from the development and use of knowledge management tools in activities underpinned by task, structure, technology, and human capital elements (Giannakis et al. Citation2018; Reid and Bamford Citation2016; Reid, Bamford, and Michalakopoulou Citation2018).

2.1. Resource-based view and theory blending with elements of practice-based view

The resource-based view (RBV) remains a long-standing theory underpinning how firms survive under competition (Bititci et al. Citation2011; Neumann and Medbo Citation2009; Papadopoulos et al. Citation2020; Yang et al. Citation2010; Yang Citation2008) that has not been effectively challenged regarding its centrality to the field of operations research (Busby Citation2019). This study adopts RBV, at its core, acknowledging the importance of resources in the legal service sector and the need for these knowledge-intensive organizations to look primarily within their capacities to find sources of competitive advantage (Barney Citation1991). Legal firms can assemble resources that work together to create organizational capabilities (Huang et al. Citation2006) and a sustainable competitive advantage (Laosirihongthong, Prajogo, and Adebanjo Citation2014). At the same time, practice-based view (PBV), a theory that considers practice as an activity or set of activities that a variety of firms might execute, emphasizes imitable activities or practices amenable to transfer across firms (Bromiley and Rau Citation2014). Acknowledging the particularity of the legal sector and identifying how much it falls behind other industries in terms of its operations management fundamentals during a pre-study, made us recognize its need for knowledge and technology transfer from other disciplines and the uptake of common firm practices.

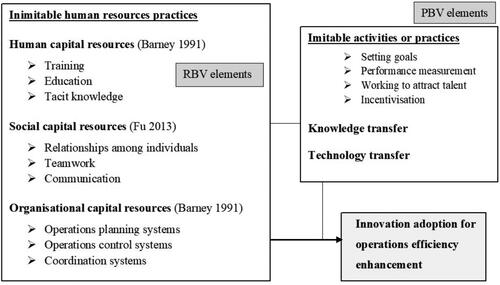

Thus, we blend the predominant RBV (Bititci et al. Citation2011; Neumann and Medbo Citation2009; Papadopoulos et al. Citation2020; Yang et al. Citation2010; Yang Citation2008) with key PBV (Bromiley and Rau Citation2014) elements to cater for these sector ‘irregularities’ as presented in . This hybrid theoretical underpinning informed the nature, context, and content of our data collection instrument since our questions focussed predominately on human resources and organizational capital issues, the efficiency of legal processes, technology uptake, and knowledge transfer. All these factors are key elements of RBV and PBV and proved to be reflecting and affecting legal service innovation.

As evident from : RBV is about human resources and social capital. Whereas, PBV is about technology and knowledge transfer. Aspects of these elements will be explored through the research and examined within the discussion.

2.2. Legal service innovation

Innovation is a compelling theme in operations management with strong associations with growth, prosperity, and the survival of the firm (Hamel Citation2006). It is one of the best ways for a company to reach its performance objectives (Robert et al. Citation2019) especially for service companies that typically lack an in-depth understanding of the practices that can be implemented to improve their operations’ efficiency (Belvedere Citation2014). Innovation for the professional service sector is the entrance of new technological tools, the effective management of employees, and the transformation of employees’ knowledge into services (Clegg, Balthu, and Morris Citation2020; Bourke, Roper, and Love Citation2020). Service innovation is, therefore, a type of service blueprinting (Radnor et al. Citation2014) that is designed to enhance the service delivery system and its constituent elements and processes.

Earlier studies (e.g. Roper, Love, and Bourke Citation2016; Desyllas et al. Citation2018) that focussed on innovation in the legal sector see innovation as a framework for ‘improved services or new improved ways of delivering legal services’. Brinks et al. (Citation2018) suggested that innovation in legal services is underpinned by the creativity and knowledge of the legal employees as these improve legal services.

Harvey, Heineke, and Lewis (Citation2016) outlined professional services, such as Law firstly, by levels of customer contact (i.e. face-to-face interaction, consultations) and consequent delivery specifications (i.e. every client’s case or transaction is different) and secondly, by operations processes that emerge as a consequence of ‘professionals’ making judgments about both ends (what constitutes an adequate/appropriate outcome) and means (the content and sequence of process steps), suggesting that are essentially fluid/flexible in character. Furthermore, evidence suggests that legal services encompass higher levels of customer engagement, extensive customization, knowledge intensity, and low levels of capital intensity (Sampson and Froehle Citation2009; Brandon-Jones et al. Citation2016). From an operations management perspective, knowledge management and transformation in association with innovative techniques, such as Lean thinking may lead to a positive process change. Understanding the key dimensions of the issues that innovation needs to tackle, and how this can be adopted by businesses, is increasingly important for managers (Yalabik, Howard, and Roden Citation2012) and crucial for the sustainable growth of legal firms looking to create a competitive advantage over their competitors.

This paper adopts service innovation as a service improvement mechanism generating positive business change that relies on technology uptake, human and social capital management and knowledge transfer all of them key elements of the RBV and PBV blended theoretical framework introduced in .

2.3. Key elements of innovation implementation

Many challenges that the legal service sector experiences can be solved through technology, but inadequate technology adoption could also be a barrier. Resources, such as technology and communication interventions are considered as innovative input elements (Fouad, Tourabi, and Lakhnati Citation2018) for creating innovative outputs (i.e. products and/or services). Technology adoption is considered a key innovation element that can lead firms to competitive advantage and can be seen as part of a wider organizational innovation (Le Bas, Mothe, and Nguyen-Thi Citation2015). Firms opt for adopting the newest technologies and products to leverage over the competitive market (Zaefarian et al. Citation2017) but the transition is not always easy for lawyers. There is a vast selection of technological tools that can help legal firms optimize their work, but most lawyers are resistant to them (Wilkins and Ferrer 2018). This research is looking to examine, among others, why this is the case.

Another significant factor for successful innovation implementation lies in the management of the human element. Specifically, the culture of a firm and the management of employees play an important role in encouraging the adoption of new approaches, strategies, and technologies. For instance, Christensen, Wang, and Van Bever (Citation2013) argued that artificial intelligence (AI) and big data science solutions can only be supported through human capital interference. The human factor also refers to the activities that the senior managers are responsible to manage and control, the operations within the legal firms, but also the lawyers. Tacit knowledge that lies among these resources is the key asset for a firm’s competitive advantage (Michalakopoulou, Reid, and Bamford Citation2017) and it can be transferred through teamwork, organizational processes, and communication (Fu Citation2013).

Managers should try to nurture social capital as a pathway to realize the true value of technology implementation (Chichkanov, Miles, and Belousova Citation2019; Wu, Liu, and Chin Citation2018) and lead their firms through organizational transitions. Fu et al. (Citation2015) supported that a firm’s human resource practices reflect and affect problem-solving via innovation. For example, managers who opt for innovative policies within a firm are more likely to influence their employees’ creativity and ideas sharing. Overall, for the lawyers, it is argued that the term innovation emphasizes their continuous journey of adaptation, evolution, and improvement (DeStefano Citation2018) as a means of providing enhanced services to a significantly more demanding and sophisticated clientele.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection and recruitment

This study has an exploratory character and thus adopts a qualitative research approach trying, much like (Siggelkow Citation2007) suggests, to provoke thought and new ideas, rather than to poke holes in existing theories and provide a fully representational analysis. This is a meaningful choice since, as Halldorsson and Aastrup (Citation2003) recognize, strong evidence exists supporting: (i) the departure of operations research from a ‘tradition’ solely based on purely quantitative methods, (ii) the rapid emergence of qualitative research efforts, and (iii) a call for rethinking the notion of research quality and its methodological implications. Qualitative research is crucial for strengthening the empirical base of operations management by enhancing insights and discovery into organizational phenomena (Soltani et al. Citation2014).

The paper is based on a systematic thematic analysis examining raw interview data collected via 53 in-depth semi-structured interviews with legal professionals that are working or have worked before their current role in legal firms across the world. This sample size, which is rather exhaustive for qualitative studies, was decided so that this study has the potential to provide more reliable and valid insights that could provide an in-depth snapshot of the current situation. We interviewed law professionals until we reached a saturation point. We acknowledge however that the qualitative nature of the study combined with the size of the sample could not lead to easily generalizable results but this type of generalization was never per se our research purpose. The specific country selection was not a pre-requisite, as this study aims to explore the operations of legal services and not their legal systems that are quite different, per se.

One-to-one interviews were preferred over other qualitative methods like focus groups for privacy and confidentiality reasons and due to the interviewees’ time constraints that would not allow them to find a common place and time to meet with other law professionals. Also, the international focus of the study meant that many of the participants had to be remotely interviewed via Skype that according to Lo Iacono, Symonds, and Brown (Citation2016) has proven to be a time-efficient and financially affordable instrument for increasing the variety of study samples. The semi-structured nature of this study’s interviews provided a layer of flexibility that allows for the discovery or elaboration of information that is important to participants but may not have previously been thought of as pertinent by the research team (Gill et al. Citation2008). The interviews for consistency reasons were based on an interview guide (provided in Appendix 2) that was organized in sections referring to the human factor element, the fast-developing technology, the efficiency of legal processes, and the transfer of knowledge following the narrative of our PBV-enhanced RBV theoretical underpinning. Spontaneous follow-up questions designed to help the interviewees make clearer their views were occasionally and per case used to enrich the content and quality of the data.

The study followed a snowball sampling where the first participants were selected based on their employment profile (Bell, Bryman, and Harley Citation2018). Then, these people were asked to nominate others fitting the same criteria (i.e. colleagues). This approach was selected as legal specialists are a difficult sample to reach; these referrals significantly increased the study’s response rate. The key participation precondition was that each of the interviewees had actively engaged with legal firm work during their professional working lives.

3.2. Method of analysis

The raw data of the semi-structured interviews were systematically analyzed through the means of data-driven thematic analysis. The approach employed was inspired by the general guidelines of Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step thematic analysis framework involving: (i) getting familiar with the data through transcription; (ii) generating initial codes; (iii) searching for themes; (iv) reviewing themes; (v) defining and naming themes; and (vi) producing the final written output. Thematic analysis is a powerful analytical tool with which the researchers can ‘identify, organize, analyze, and report the finding patterns’ in the data corpus (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) that has been widely used in operations research (e.g. Leite, Bateman, and Radnor Citation2019; Schroeder et al. Citation2019).

Throughout the analysis, the researchers ensured that the extraction and presentation of findings were based on the raw data rather than on their own interpretations to reduce bias using a thematic analysis presentation framework in line with the works of Nikitas, Avineri, and Parkhurst (Citation2018) and Nikitas, Wang, and Knamiller (Citation2019). This is a line of work that fits with best practice guidance, as advocated by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), since it builds the qualitative analysis around the selection of the most powerful raw extracts of the interviewees’ answers that could demonstrate clearly the explicit dimensions of the selected themes. This is superior to the use of analyst-deduced summaries or more quantitative-based presentation and interpretation approaches (Nikitas, Avineri, and Parkhurst Citation2018).

The study’s qualitative results were organized and analyzed using the qualitative software NVivo11. The interview transcripts were coded following the patterns of the interviewees’ responses; this was a data-driven process. More specifically, we used an inductive coding framework meaning that codes (that were later organized in sub-themes and themes) were generated directly from the examination of the collected data and not based on pre-defined codes dictated by the relevant literature. So, we did not use prior codes developed before the data examination but instead attached codes to units of data as we were analyzing the transcription files. Our only critical analyst-based deliberation was our explicit focus on the challenges and opportunities for innovation adoption in the legal services context; this was a generic prefabricated focus defined by our theoretical underpinning, the structure of the interview guide, and the questions asked and not by our thematic analysis per se (Boyatzis Citation1998).

The coding protocol provided in Appendix 3 presents in detail the frequencies (i.e. reference counts) of each code as evident in the interviewees’ transcripts that partially led to the sub-theme formation; this is the finalized protocol that all authors agreed to. Nevertheless, it should be clearly noted that the code, sub-theme, and theme selection was not only based on a quantitative-styled theme-devising exercise (i.e. reference counts) since in line with Clarke and Braun (Citation2013) and Liu, Nikitas, and Parkinson (Citation2020) we believe that a strong thematic analysis focuses primarily on the researcher’s reflective and thoughtful engagement with the data and the analytic process in a way that embraces their qualitative nature. Piecing together the overall picture was thus not simply about aggregating patterns and reference counts (Nikitas, Avineri, and Parkhurst Citation2018) but as Musselwhite (Citation2006) suggests, a process of weighing up the salience and dynamics of issues, and searching for structures within the data that have explanatory power, rather than simply seeking a wealth of evidence.

To enable the selection of the ‘best’ quotes, ensure reliability and reduce any analyst-generated bias that could be linked to a single researcher, the four authors analyzed the data independently for the coding stage and then compared and synthesized their independent coding analyses to build a single ‘bigger-picture’ narrative that defined the themes and sub-themes. During the synthesis procedure and after exhaustive discussion we reached a 95% consensus on the codes that were eventually the building blocks of our themes; this exceptionally high agreement in the key qualities underpinning our systematic analysis framework increases the reliability, validity, and rigor of our work by reducing individual research biases since the authors acted as cheques and balances to each other. Although eliminating biases will never be perfect in such studies (Symon and Cassell Citation2012), by adopting a systematic, intensive, and insightful interpretative approach we tried (and certainly to some degree we achieved) to improve the legitimacy of our analysis.

The themes as emerged from our inductive analysis process are presented one by one in section 4 (a sub-section is dedicated for each of the six themes, i.e. sub-sections 4.2–4.7). Each of the themes analyzed has different dimensions and expressions clearly presented as their sub-themes. A thematic map is presented in sub-section 4.8 that provides a holistic contextualization of all the themes and their sub-themes as facilitators or barriers to innovation.

3.3. Sampling characteristics

The sample consisted of 53 legal professionals. Most of them were active legal practitioners and all had some working experience with a legal firm in the UK or abroad. More specifically, the participants were law academics, law firm partners, attorneys/lawyers, trainee solicitors, legal IT experts, in-house lawyers, barristers, and legal administrators. Some of the interviewees had served in multiple roles throughout their respective careers. For instance, 12 of the interviewees although employed in academia were qualified but not practicing solicitors. This twin professional background potentially adds value to the research as these interviewees could identify more broadly the challenges of the legal sector and its capacity to innovate since they have faced these themselves in their previous role but currently have the distance and neutrality of an academic. The interviewees’ key characteristics are presented in Appendix 1.

4. Results and analysis

4.1. Overview of the analytical process and key results

From the thematic analysis, six main themes emerged, each of them with multiple dimensions and expressions, based on the patterns of the interviewees’ responses. The six themes are human factor and culture, client and market, technology, organizational transitions, legal processes, and education. The majority of our participants suggested that many problems prevent a firm from maximizing its potential, which mostly arises from the legal profession’s heterogeneous, diverse and complicated nature. They also identified that there is a need for operations improvements within their legal firms’ structures and culture as a whole. It seems that the legal service sector’s innovation adoption is limited and slow; the sector is less responsive and flexible to change and to the rising and increasingly diversified client expectations than what is expected from an industry that is one of the backbones of modern society. The analysis also identifies that law firms need better internal and external channels of communication, are exceedingly demanding in terms of resource allocation even to the level of each employee, and should be supported by a more holistic approach to training and education that involves developing an advanced understanding of non-legal matters referring to technology and management.

The remaining section includes a theme-by-theme analysis that presents representative raw interviewee quotes reflecting directly or indirectly innovation or elements, dimensions, forms, or expressions of innovation adoption or consideration. It should be acknowledged that innovation was not a term always understood by the interviewees or understood in a homogenous way by all of them; innovation is a non-straightforward and rather abstract notion for most lawyers and legal professionals. However, the research participants did recognize innovation as the sum or the product of different innovation components usually referring, in par with our interview guide and theoretical underpinning, to technology uptake, human and social capital management, and knowledge transfer. That was what made our interviews meaningful and the quotes selected useful for our analysis. All in all, this qualitative work aims to identify and assess the challenges and opportunities that define the legal sector today with an emphasis on areas reflecting the innovation potential.

4.2. Theme one: human factor and culture

The first theme is the human factor and culture and discusses the working environment and professional convention issues. This theme is entirely aligned with our theory since it acknowledges the importance of resources in the legal service sector in general and human resources in particular. Three distinctive sub-themes emerged all of them unique enough to be distinguished as separate considerations but relative enough to be part of a single umbrella theme reflecting and affecting the human and cultural element. These were namely: management of human capital, work-life balance, and resistance to change.

The poor and inadequate management of employees can often be a critical problem. The people in charge of managing and leading employees are key parameters in any productivity enhancement process or innovation adoption initiative. For instance, being managed solely by lawyers was not seen as a precondition for success but as a possible barrier. Respondent A.P. –19 believes that ‘lawyers are not qualified enough for being responsible for the human resource management, but only for legal matters’. This can result in a lack of leadership within the firm.

With the ABS entrance, non-lawyers, such as accountants or/and business managers, are allowed to create their own legal firm. This has resulted in both advantages and disadvantages in terms of the employees’ management. Supporters of the mixed management approach argued that senior managers from different backgrounds can have a better understanding of the employees’ and projects’ needs.

Nonetheless, opponents of the hybrid management style believe that non-legal owners cannot fully understand them, resulting in frustration and misinterpretations amongst them. ‘I have worked with people who are not lawyers and yet they are running law firms. It is absolutely atrocious’ (C.M. –32). Respondent A.A. –25, had a similar but more modest point to make ‘I know some firms in town that are managed quite hands-on by non-legally qualified managers and I think that causes a little bit of friction sometimes. I am not sure if that works very well’.

Reaching an optimal work-life balance was important for legal professionals but many of them felt they could not achieve it; work for many interfered with non-professional life. Heavy workloads, strict deadlines, and long working hours combined with minimal training make some law professionals see themselves as factory workers and not as innovation producers or facilitators. ‘Managers are trying to cut down costs. Some lawyers are just being used like factory workers, like fee earners’ (A.A. –25).

According to many respondents, no matter the size of the law firm they were working with, the legal profession is associated with a frustrating lack of personal life. As the competition increases, managers focus on maximizing profits forgetting about their employees’ well-being. This is one main reason that pushes legal professionals to decide a career change, moving from legal firms to being in-house lawyers, becoming self-employed, or entering academia.

Many interviewees acknowledged that they could not plan their daily schedule. Pre-scheduled appointments are not necessarily the norm nowadays. Lawyers need to have long and high billable hours in their timetable, to be viewed as productive employees. ‘You have to cope with long working hours and have to be prepared to be very flexible on your day-to-day programme. A client can call you at 6 pm and you have to be available to work for him/her’ (G.S. –37). ‘You need to be able and willing to dedicate part of your private life to the firm’ (F.E. –7).

Poor work-life balance, a modern ‘service innovation-killer’ (T.D. –40), is an ongoing issue that legal managers need to work on providing solutions that themselves embed a degree of innovation, like flexible working hours, additional appraisal schemes, or working from home to help their employees manage their time effectively. Training sessions on stress and routine management could also be a suitable innovative practice.

The sub-theme resistance to change refers to the legal professionals’ unwillingness to adopt change. This is a diverse phenomenon that is central to this work directly affecting innovation adoption. The legal profession has been for years attached to a culture that in some cases is severely outdated. Most interviewees supported that the profession has to go through a cultural transformation. ‘The profession is running historical; the recruitment criteria are often similar as those of the past rather than adapted to today’s requirements, because they (senior managers) want to recruit and work with people like them’ (A.D. –53).

Most respondents regardless of their position or the size of their firm, argued that change is slow and often linked negatively to both the management structures and to the employees’ culture. ‘Change is quite slow. The law firms might not have the capacity to focus on the change that needs to happen as much as they would like to’ (PM.C. –42). Lawyers typically are reluctant to adhere to new processes and technological tools. This is particularly relevant for more experienced professionals (10 or more years of working experience) of our sample as they already learned to follow specific procedures, systems, and guidelines. ‘There is a resistance of adopting new things’ (P.MO. –18) and ‘the industry is a bit traditional, maybe not in line with the technology development’ (I.M. –46).

Another respondent with long experience in leadership roles argued that although most law firms are embracing innovative technological tools to keep up with new trends, their outdated thinking keeps legal employees in the past. ‘I still believe that all law firms run in an old-fashioned style that fits the way lawyers and bankers still see the profession. You want employees to send emails and information as quickly as possible but you still impose on people to waste their time on silly things. I believe there is no reason for everyone to come with a suit and a tie or even come in the office every single day. That old-fashioned style of professionalism is annoying, given the generally fast developing and technologically informed environment that we all are living in right now (P.D. –33)’.

Employing legal project managers is the latest trend that many large law firms start to integrate into their culture to tackle such issues. A chief information technology officer in a large law firm while discussing one’s efforts to persuade lawyers around the world to adopt new technological tools for improving their document management and minimize their workload pointed out the reasons why this is difficult. ‘Lawyers are individualistic, they are resistant to change, they are very good at arguing against standardization, they are good at arguing against consistency; lawyers believe that they are unique and they deserve unique solutions’ (T.D. –40).

Ultimately, resistance to change from law professionals is frequent and rooted in the legal industry’s traditional and long-standing conventions. However, new business structures of law firms and pressures from a highly competitive market should remind them of the need for continuous development and innovation adoption.

4.3. Theme two: client and market

The present analysis supports the case that law services need to be client-centric and to reflect the dynamically changing market needs; innovation can be a key for this. Competition was referred from all the interviewees as the major reason for staff redundancies and change of direction in their careers. Specifically, participant A.A. –25 due to the recession and the risk of being fired, took the opportunity to join the academic sector. ‘I was sort of forced out by the fact that there was the recession and commercial property was drying up. We were going to lose people so I had the opportunity of joining a university, before I get redundant’ (A.A. –25).

The role of the lawyer and the recruitment criteria were also re-formed allowing less room for innovation. Fixed-term or part-time contracts were introduced as a response to competition; law firms are hiring lawyers on demand. Competition thus adversely affected, in many cases, the nature of contracts, especially for early career professionals. ‘A lot of the jobs advertised are 12-month fixed term contracts. That is one of the ways that firms build flexibility. They are not sure about how the volume of the work is going to continue’ (A.A. –25).

Similarly, the competition that the continuous entrance of new law firms creates, drives legal service fees down. Online platforms and websites offer legal advice to clients at a competitive price, forcing law firms to decrease their fees or compromise with alternative fee arrangements. ‘I was doing a market research the other day and I saw a couple of websites that advertise their conveyancing for £400 which is basically nothing compared to the number of hours you are putting into conveyancing’ (T.A. –5). When firms are struggling for their survival and the margin for profit is limited, it is difficult to make a meaningful investment in innovation.

It seems that lawyers’ value has weakened, and in association with the high customer demand, law firms conduct their work faster and at a reduced cost. Communication technology can, in theory, support this need since lawyers cannot spend the same amount of time and resources communicating face-to-face with one client as was happening in the past. On the contrary, they have to cater for and attract new clients, devoting less time and perhaps compromising on quality.

Clients are playing an important role in law firms’ prosperity and it is a factor that can drive change. The value of their clientele plays a huge role for the interviewees, so they dedicate time and effort to address the interaction needs of their clients despite the scarcity of resources. ‘We are interacting with our clients mostly via email or Skype, or on the telephone. However, we are mostly focussing on whatever method is available and convenient to the client’ (O.E. –8).

Many of the participants, however, argued that the entrance of new technological advancements has resulted in a lack of interaction between them and their clients. For example, P.K. –1 argued that ‘lack of communication is a massive complaint to firms’. Similarly, T.R. –2 stated that ‘customers want to see their lawyer face-to-face and not just see documents online’.

Lawyers are supporters of face-to-face interaction with the client, as it can help them to solve problems faster and avoid misunderstandings. The telephone is on many occasions the preferred communication medium with clients. For now, lawyers seem to be reluctant in adopting innovative means of communicating, like Skype and similar platforms, as they argue most of the time these do not work properly. A partner in a large law firm in Germany with 27 years of experience argued that although some firms have heavily invested in technology communication, many prefer doing long mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transactions via telephone for the benefit of their clients. ‘Most of our communication with clients is via email and phonecalls. We can have an 8-h telephone conference when we do M&A. Clients also think it works easier and faster’ (G.U. –36). Technology can thus also be a challenge that may reduce willingness to innovate; this will be analyzed as the main theme in section 4.4.

Another sub-theme refers to high client expectations. As clients are the driving force for profitability, lawyers must respond and satisfy their needs. PM.K. –26, working as a lawyer before and as a legal project management in a large law firm now, suggests that nowadays clients are more aware of the legal service processes and anticipate a better service. ‘Clients have growing expectations which are beyond receiving a good legal service; they now want it in a way which works for them when in the past the legal transaction, would run on their behalf without being visible to them’ (PM.K. –26). Law firms seem to have responded to this crisis, by hiring more project managers to assist with their operational processes. ‘We have noticed that the legal project manager department has grown, because clients want us’ (PM.N. –24).

Moreover, technology has also helped to form this very demanding client-oriented market. On the one hand, clients expect fast responses from their lawyers on their matters and on the other hand, faster processes result in more cases assigned for them to solve. ‘In terms of practice, clients are the biggest problem – they have unrealistic expectations. They expect to be able to email you at any time and you have to respond back as soon as possible’ (T.M. –10).

However, A.C. –6 supports that ‘it is better to empower the clients to understand their situation and advise them accordingly to deal with their problem and not just represent them’. This can also enhance the interaction in certain ways. For example, P.K. –1 pointed out that ‘due to the fact that cases are managed and solved through online programmes, clients are not supposed to meet their lawyers, and therefore, they have to be knowledgeable of their legal matters, before they address them to a lawyer'. That is true, but disruptive, as supported by legal firm owner J.F. –44, ‘most people that visit a lawyer already have researched on Google many of their questions beforehand. So, disruption is another issue, because IT is developing fast’.

4.4. Theme three: technology

Technology emerged as a critical theme in our analysis since technology uptake is typically one decisive path to innovation. Most of the interviewees argued that although technological tools can help the legal profession through innovating document and case management systems, they can also impose security risks. Cybersecurity was a key concern for all law professionals as they are dealing with clients’ confidential information and large amounts of money. For example, an interviewee said that ‘with technology in place there is a risk of hacking and therefore more security issues’ (A.PC. –29). The lawyers’ concerns about cybersecurity and its destructive effects have increased after the 2017 cyber-attack on a global law firm operating in the UK and strict regulations are now in place.

Our analysis identified that our more experienced interviewees (10 years of working experience in the legal sector or more) were likely to bring up the risks associated with technology adoption. They feel more comfortable without it and there is no need to change to something that is not secure enough. ‘The use of technology exposes law firms to risk that they were not used to address regarding information security and hacking’ (A.C. –6). ‘I think there is a legitimate fear of security. A lot of cases are very sensitive so law firms are afraid that details of their cases may leak or they may get lost. If you lose essential correspondence, you are in big trouble’ (P.MO. –18).

Others thought that technology can come with risk but law firms looking to emerge must be brave and invest in innovative systems to have a competitive advantage over competitors. ‘The problem with technology is that it leads law firms to potential vulnerability to be exploited for fraud purposes. But then again as the world gets more competitive and the pressures for efficiencies get greater, they have to look at the way successful firms stay ahead of the curve. My firm thrives because it has adapted to change better and it has been better financially and technologically managed than other firms’ (AD.J. –30).

Some law firms try to tackle the technology and cybersecurity issues by recruiting legal engineers with the dual-task to facilitate efficient processes and train the law personnel. Training on the new IT developments may be the answer to the lawyers afraid to use technological advancements to support their legal work. Some of the respondents employed in senior legal positions argued that training could potentially tackle the resistance to technology adoption. ‘Technology for me has been really helpful. I mean I am not an IT freak, so at first it may seem a little bit difficult, but it is not eventually. You get used to that (technology) but since I have trained and learnt how to use these new facilities, it is much better’ (I.EG. –48). Training is thus a key opportunity for technology adoption.

Some firms select to outsource their IT systems for additional security. ‘We actually have a third-party IT company that basically does it all; looks after, maintains and improves our IT systems. We now have written cybersecurity policies and procedures in place as to what we are expected to do when there is an issue’ (AD.J. –30). This is an entirely different path to progress and innovation based on acquiring knowledge from external collaborators.

Communication technology implications are equally important. Faster and easier communication with clients is the main improvement for the legal sector that is founded on technology. As C.M. –32 stated ‘technology enables the solicitor to operate with less physical contact with the client. The customer does not need to cover any distance to come to the office; instead they can just upload a case online to the system. Technology can also assist in the administration of a case’. Similarly, T.AD. –21 argued that ‘emails make our life easier. Communication technology helps a lot’.

However, not everybody is satisfied with the way that online communication operates. Some lawyer-to-client relationships need physical contact for building up trust. For example, family law cases are those that are most sensitive in context, as clients need encouragement during their legal process. Lawyers believe communication technology can harm certain law cases rather than assist to solve them efficiently. According to T.M. –10, ‘most people rely on technological systems too much, ignoring the face-to-face contact with the customer’.

4.5. Theme four: organizational transitions

The fourth theme refers to political implications and organizational transitions. One notable example that emerged from the UK interviewees reflecting and affecting this theme was Brexit and its aftermath. As legal multinational companies operate under strict regulations and laws in the UK, a change on them, such as Brexit, could have a considerable impact on their operations in various ways. The British legal professionals of this study argued that it is still unknown what law firms will have to do to comply with the new regulations. ‘It is still uncertain what will happen with the Brexit. I believe that people are scared, law firms are trying to move their head offices in Ireland, a lot of solicitors are trying to qualify in Ireland to keep being a European lawyer’ (T.A. –5). On the other hand, Brexit for the short term has created opportunities for most law firms as it has increased their profit margins. Immigration law is an area positively affected by Brexit. People feeling uncertain of the consequences of Brexit are more likely to seek advice from a lawyer. ‘Firms responsible for immigration procedures would have a lot of work to do’ (I.O. –17).

The introduction of new regulations with some examples for the UK context being, the Tesco law, the decrease in legal aid funding, and the deregulation of 2007, has considerably increased the competition within the legal profession. The regulatory authorities like Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) and the Law Societies are forming the legal models that legal firms are permitted to use. These may sometimes lack innovation when according to Ramanathan et al. ( Citation2017) flexible regulations help innovative firms in improving performance and inflexible ones do not.

More specifically, the decrease in legal aid funding was a big challenge for the UK legal sector as it reformed the way many law firms and legal aid lawyers were operating. Many lawyers dealing with clients in criminal and family law lost their job, as customers did not have help from the state to fund their cases. Others tried to adapt to the new regulatory formations by changing their area of expertise or simply by being among the few that remained in the legal aid sector. Overall, as A.P. –19 pointed out ‘the reduction and the withdrawal of the legal aid, and in particular the criminal legal aid are important challenges’. Furthermore, T.M. –10 supported that ‘it is extremely difficult to get by with the legal aid salary. And because funding is limited and legal aid has decreased since 2013, law firms are made severe cuts. They do not invest much as they used to, to make things easier for their employees, in terms of IT and infrastructure’.

The regulatory bodies and the government are the institutions responsible for the key organizational transitions that have an impact on the legal profession. Law firms operate in an environment that every change can affect their ability to innovate. When there is a need for change, it is not only the lawyers that have to adapt but also the overall system, and that is difficult. ‘I think it needs a culture shift but because the legal profession is not just lawyers, is the regulatory bodies, it is the SRA, it is the Barr Council, it is the courts, it is the university Law schools, this is hard’ (A.D. –53).

Organizational transitions and their impacts cannot be easily absorbed even when innovation adoption within law firms is thriving in discrete areas, such as the adoption of smart contracts, and is evolving new roles within the profession, such as legal project managers. In this case, innovative policy reform and responsiveness can be the apparatus for navigating successfully through big changes.

4.6. Theme five: legal processes

Legal processes refer to the transactions that lawyers are following from the beginning of a client’s instructed case until its completion. The level of complexity of these legal procedures differs from client to client, but also from one law area to another. For this reason, there are no pre-written processes of how a case should be handled and run, and most of the time it lies down to the lawyer’s experience. Hence, managers struggle to define efficiency and to take measures to tackle the potential bottlenecks.

The complexity of legal processes is a key challenge adversely affecting efficiency and innovation in legal firms. Efficiency is strongly associated with the complex nature of each legal transaction. For instance, long transactions like M&A require teams of lawyers to secure the deal; that means more resource allocation is needed for the client’s legal case completion. For instance, ‘the average time delivery for our corporate transactions takes three to four months and it is complex. It is quite a long process and cannot become any shorter’ (P.D. –33).

Many senior lawyers responding on how efficient their area of work is, argued that the legal sector is running effectively enough after the email entrance and automation could not be applied in a professional service environment. ‘We improved significantly. We used to physically post the documents, now we do everything electronically. I do not think you can get much more efficient than that’ (A.A. –25). There were many others though pointing out that there is room for improved operations efficiency. However, most of them do not know how this can be achieved, when considering the diverse and heterogeneous nature of the legal context and the unsuitability of most technological tools. ‘The legal processes today are extremely inefficient! For example, there is much waiting for court hearings. The courts are overwhelmed and understaffed resulting in cases taking years to run their course’ (F.E. –7).

At the same time though, as competition increases, law firms have to opt for efficiency measures to increase profit and improve performance. For instance, process mapping and the use of machine learning (ML) and AI as innovation tools are becoming more frequent and common. Some of the law areas, such as insurance claims, personal injury, and conveyancing can be characterized as more efficient in comparison to complicated procedures such M&As and commercial real estate. Thus, we argue that the more standardized/automated a legal process is, the more efficient in terms of time, cost, and resources it can be. Efficiency is also defined in very practical terms from G.S. –37 who said that efficiency is equivalent to ‘only one person having to review a document and then present it to the partner’. Thus, the more parties involved, the less straightforward a transaction can be.

Another reason behind the inefficiency of legal processes is repetition. Although there is a lot of repetition in the legal sector in the form of documents, communications, and processes, most lawyers still believe that each case is unique and develop new templates each time. ‘There is no repetition of documents. Every day is a new day and every case is different. Especially on litigation’ (T.AD. –21). Although this approach can reduce potential errors, it can be also extremely time-consuming. Two former lawyers working as legal project managers have a different take that fits our narrative. ‘I think that the best way for law firms to handle costs is by ensuring that the processes are handled efficiently and not by recruiting less people or lower level staff’ (PM. N. –24). ‘We would take the learning from one matter that we have done and bring it across to other matters. This will result to run processes more efficiently’ (PM. K. –26). This type of internal knowledge transfer can be a source of competitive advantage for firms.

Thus, process coordination and effective management are essential parts of business success and a different form of innovation. However, law firms typically acknowledge that to achieve efficiency and increase profit, they have to innovate by decreasing operative costs and semi-automating, as well as standardizing procedures. Sometimes though, they opt for outsourcing their non-core activities or having franchise offices at low-cost countries to reduce handling costs. ‘It was more cost-effective for our law firm to have their offices abroad’ (PM.C. –42).

4.7. Theme six: education

The last theme refers on the one hand to the academic education and the skills that students obtain from Law Schools and on the other hand, to the knowledge transfer and exchange among the university law lecturers and the industry law practitioners. We identified that professionals that enjoy better education and life-long training are better situated to be part of the innovation process of their respective firm.

Academic education is the first important hurdle law students have to overcome to enter the legal sector. Law schools are providing the fundamentals of law to students equipping them for their future careers. However, junior lawyers graduating from their courses, have to apply and complete traineeships from law firms to practise the profession. Many of them find it difficult to secure a contract. ‘Law is a difficult route because the investment in education to become a solicitor is huge, so all this input has to be worth it’ (T.A. –5). Trainee solicitors that participated in the study highlighted the challenges that they faced after graduating from their legal course. A trainee solicitor, who is a part-time student in an MSc programme and paralegal in a small firm believes that undergraduate studies provide a basic theoretical knowledge not aligned with the sector advancements. ‘In my undergraduate degree in England I was taught the basics, but if you are just learning things by heart you are going to forget about them when you go for work. While if you do those two in parallel (studying and professional practice) things stick in your mind and you never forget’ (T.A. –5).

Another respondent working in the USA emphasized the lack of skills of the trainee solicitors entering law firms. ‘There are a lot of newer attorneys that do not necessarily have the experience and skills to enter the sector but are tech-savvy. Junior lawyers in the USA learn the ‘rule’ of procedure in school but they cannot learn how to effectively practice, maintain ethical standards and other practices without the real-world observation and practice… I see a huge gap in what is being taught in the classroom and what is happening in the real world’ (F.E. –7). This means that academic institutions do not necessarily equip their law students with the required state-of-the-art skills as of now limiting their ability to innovate.

Knowledge and its dissemination are key issues for modern organizations that seek to gain and maintain a competitive advantage (White et al. Citation2019). When it comes to knowledge transfer the legal system should function as a meeting place for law practitioners and law academics. Their respective knowledge, experience, and opinion exchange could be a key asset in this demanding professional service environment and a facilitator for innovation. The majority of the respondents believed in the value of knowledge transfer, but they acknowledge that it is not common among them. The reasons for it are the confidentiality of the profession and the vast differences in the work they are undertaking in their everyday life.

On the one hand, legal practitioners believe that the communication between them and law academics is difficult; usually, they do not understand each other. They argue that ‘there is a feeling, almost a reluctance, to engage with them [academics] on the ground’ (G.U. –36). They also think interaction is very limited ‘I was thinking about the relationship between the two parties… it is close to zero’ (I.M. –46) and ‘there is not a lot of cross-over between the practice and academia which is a bit surprising’ (P.MO. –18).

Interviewees working in law education stated that universities tend to hire people with practical experience that can bridge the communication gap; these interviewees also see more potential for synergies between the two groups. ‘People in our university department are professionally qualified anyway and they have still their practice certificates. But it is always good to talk and I do not think people talk enough and the reason is the lack of time. All in all, I have had practitioners ring me up and ask for my academic opinion, and also the opposite having people ask for my opinion as a practitioner’ (LS.D. –52).

However, our participants were open to exchange ideas and accommodate more synergy opportunities. ‘I think knowledge transfer would be useful because people who are practicing do not really have the time to read basic things and work through things’ (O.Y. –49). This could help for example small legal enterprises that cannot invest in additional resources to create partnerships with universities and expand their tacit knowledge. ‘The challenge for me is to bring all of the knowledge that I have got from the big law firm where I was working and apply it to the smaller firm now as an owner, outsourcing where it is needed the expert advice and help from Law Schools’ (O.E. –8).

One platform for synergies that Law Schools offer is the ‘legal advice clinics’ which is a medium of knowledge transfer that links academics, students, and professionals. ‘The legal advice clinic is supervised by practitioners, professional lawyers whose skills are being shared and acquired by students; students who do have placements in law firms’ (A.A. –25).

4.8. Mapping and contextualizing the themes

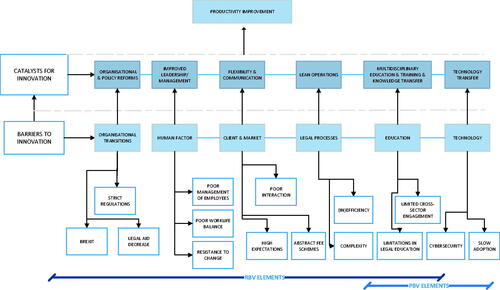

A systematic and critical synthesis of the themes and sub-themes discussed in detail in the previous analysis sections is presented in . The key findings of our data-driven thematic analysis are embedded in a conceptual framework coupling theme-induced barriers and catalysts to innovation, grounded by our theoretical narrative that blended RBV and PBV (see bottom of ). This framework, based on the six emerging themes, is the first-ever scientific guide that identifies, taxonomizes, and directly relates the barriers and opportunities characterizing a legal firm’s capacity and potential to innovate. Barriers to innovation are defined by: (i) organizational transitions and regulatory restrictions; (ii) resistance to change, work-life balance issues and management problems; (iii) poor communication and interaction, complex fee structures, increasing client and industry expectations; (iv) the complexity and limited efficiency of legal processes and operations; (v) insufficient and monocultural education, inadequate training provision and limited knowledge transfer opportunities; (vi) technology adoption problems including cyberthreat-phobia and lethargic engagement with modern tools.

The opportunities (or catalysts) for establishing clearer pathways to innovation relate predominantly to: (i) organizational reforms and policy change; (ii) improved management of human resources and more effective (or even hybrid) leadership; (iii) organizational and operational flexibility and effective communication; (iv) Lean operations that minimize duplication of effort; (v) improved Law School education and continuous interdisciplinary skill training that both incorporate IT and project management perspectives and knowledge transfer initiatives and structures including outsourcing; (vi) technology adoption enhancement in all aspects of legal service operations. The first four of these problem-opportunities couples are benchmarked by RBV, the fifth by both RBV and PBV, and the last by PBV as shown in . This thematic map could be used by legal firms as a guidance tool that will allow them to first appreciate the diversity of innovation as a multi-layer pathway to efficiency and productivity improvement and then adopt it more effectively.

5. Discussion

This paper contributes by presenting an in-depth qualitative exploration of the key challenges and opportunities for innovation adoption that legal professionals and their respective law firms are now facing. Our analysis highlights the lack of empirical research on the diverse issues the employees experience when working in the professional services sector (Dobrzykowski, McFadden, and Vonderembse Citation2016; Zhang, Gregory, and Neely Citation2016) in general and the legal sector in particular (Segal-Horn and Dean Citation2007; Lewis and Brown Citation2012; Susskind Citation2017). Change is underway in the legal profession and is being felt acutely by lawyers in every stratum of the occupation (Riordan and Osterman Citation2016) so responsiveness and adaptability to change needs to be promoted and nurtured in law firms. With a plethora of innovative technology instruments, education and training initiatives, institutional reform opportunities, and advanced operations management techniques already in place, but seldomly utilized thus far, the authors make the case that legal services can become more efficient. Six diverse themes underpin this study namely: human factor and culture, client and market, technology, organizational transitions, legal processes, and education.

From the interviews, it seems that some legal professionals felt overwhelmed by the rapid need for technology adoption in the sector; for them, resistance to change is more natural and innovation adoption is, therefore, a more complicated process. From our pool of respondents, the senior lawyers with more working experience tended to be less open to technology interventions and change altogether, especially in the absence of a ‘helping hand’ as described in Sochor and Nikitas (Citation2016). Many of our respondents that were newer to the profession, such as trainee lawyers, however, saw technology as a tool that makes their professional life easier and were less bound to the ‘established conventions’ of the profession. These newer law professionals have therefore possibly the potential to be early innovation adopters. So innovative approaches could first target them and they can then propagate the message of ‘change’ to their colleagues.

There were however concerns about the educational training that grooms lawyers today; it was deemed tech-savvy but not fitting the actual real-world demands of the legal profession practice. Linking Law school education with practise and vice versa may be a way forward; knowledge transfer synergies between the two is another form of innovation that is particularly suitable for the legal sector. This is in line with Reid (Citation2020).

Technology, ranging from simple emails and data storage/management to teleconferencing and AI-based operations, was viewed as a potential source of problems and as a tool that despite its merits could create more distance between service providers and clients. Cybersecurity threats were highlighted as a possible pitfall for legal firms and there were some underlying concerns for people with low digital literacy. Increasing the law sector’s preparedness to deal with cyberattacks via voluntary and mandatory regulations (Hiller and Russell Citation2013) and more importantly via custom-tailored digital training for lawyers and the hiring and utilization of special IT and project management personnel could alleviate these concerns. However, this transition process could be slow and resource-intensive. Face-to-face meetings should also complement less personalized and more remote communication channels; these meetings can be reduced but never completely substituted due to their trust-building and physical interaction value.

At the same time technology was considered by many as a huge enabler that modernized, simplified, and made more flexible communication and interaction norms and channels internally and externally. This is in line with the study of Martin and Omrani (Citation2015) based on the European Working Condition Survey arguing that Internet use and ICT uptake are positively related to employees’ job satisfaction and extra effort. It is also relevant with Smith, Blazovich, and Smith’s (Citation2015) key finding suggesting that the more social media platforms a firm uses, which is a form of innovative communication, the higher its ranking among prestigious law firms is, since social media can be used for client development, networking, disseminating information, and building awareness of the firm and its practices.

We also found that technology was in some cases an apparatus that could create new layers of efficiency by minimizing replication of work and by standardizing procedures involving some degree of repetition. This is in line with Santa, Hyland, and Ferrer (Citation2014) key result suggesting that technology innovation is highly correlated with operations effectiveness. Ways of increasing awareness regarding the benefits of technology could be also critical for supporting technology adoption.

All the legal professionals interviewed had to sacrifice personal time for their daily work duties and considered their industry as a particularly challenging one defined by slow change, inflexibility, complex organizational transitions, pay cuts, low fees, high customer expectations, and legal process inefficiencies. In some cases, lack of adequate management, leadership, and communication was also identified as key efficiency and innovation adoption barriers when these should be decisive facilitators of good practice. Nurturing interdisciplinary skills even at the top managerial level that go well-beyond legal matters (e.g. project management, ICT), outsourcing non-core components of the firms using the help of specialists, and hybrid models of leadership may all be innovation practices that lead to significant productivity improvements. Thus, legal professionals, similarly with other professional service employees, need an increased non-billable time allocation (Duane Ireland, Kuratko, and Morris Citation2006), flexible working opportunities (James Citation2014), a balanced mix of soft/interpersonal and hard/technical skills that comes from multidisciplinary training (Hendarman and Cantner Citation2018) and an entrepreneurial and knowledge-oriented style of leadership (Bagheri Citation2017) to maximize their engagement with innovation-building activities. Less regulatory restrictions and better responsiveness to organizational transitions and policy reform could also support innovation-based interventions. The literature supports this recommendation arguing that very strict regulatory framework conditions may negatively influence innovation activities (Blind Citation2012).

Based on these findings, our study recommends that in many cases where the legal profession operates in a way that is not effective, robust, or technologically informed, problems should not be ignored; problems should be solved. This is because the legal sector is a service provision industry with immense socio-economic impact in today’s world and cannot be dictated by resistance to change and unwillingness to innovate. Law and lawyers shape culture (Friedman Citation2017) and this process require adaptability to change and the capacity to innovate.

Innovation should be looked at as a concept synonymous with knowledge transformation that means to create positive process change and business improvement; it can be reflecting technology uptake but goes well-beyond that. Innovation adoption should be incremental, strategic and may start not necessarily from technology per se but from education, management, and interaction interventions. For example, since many participants highlighted the lack of knowledge transfer between the legal industry and universities, establishing synergies between them could be a less radical starting point for transformation in light of Tassabehji, Mishra, and Dominguez-Péry (Citation2019) argument that knowledge sharing is correlated with innovation performance improvement. In particular, knowledge transfer partnerships, a form of innovation that can lead to new ideas creation and creativity promotion, could be a helpful and not particularly expensive lifeline for law firms in need of external support.

Tsinopoulos, Sousa, and Yan (Citation2018) agreed with the importance of open innovation that firms have to leverage on, for achieving product and service improvements. This refers to businesses creating and sustaining contacts externally with suppliers, universities, and competitive parties (Laursen and Salter Citation2014). Innovation should be also used as a tool enhancing customer satisfaction since as Maguire et al. (Citation2012) admits the competitiveness (and survival) of any company will be determined by the nature of its interaction with customers that for law firms need to be of high quality.

Lean thinking is a distinct operations management tool, successful in other sectors (Hines, Martins, and Beale Citation2008), that could enhance innovation and technology adoption (Zhou Citation2016). More specifically Lean thinking constitutes a well-established path to higher quality, improved operations performance, increased timeliness, and greater respect for the people who provide the services (Bamford et al. Citation2015; Womack and Jones Citation2015) that is getting some traction lately with the law sector (some law clinics use Lean thinking principles according to Nicholson and Pakgohar Citation2019). If Lean thinking is combined with other innovative work practices that are founded on added flexibility, skill-creation, interdisciplinary training, collaboration, and incentivization initiatives that are positively related to employees’ positive attitudes towards work conditions (Martin and Omrani Citation2015) they can formulate an innovation package that can improve legal processes and create competitive advantages.

However, innovation, in any of its forms, should not be applied in isolation or as a monoculture; it must be approached as a holistic and multi-layer philosophy of thinking and acting for continuous improvement and change in the whole business environment from the top, the management, the daily routine of employees, to the bottom, how the operations run, level (Melton Citation2005). Innovation needs to be approached as a journey for continuous performance enhancement and not solely as an organizational process in line with Drew (Citation2006). Law providers must also recognize the pursuit of incremental innovations formally in their innovation strategies and define formal processes for implementing these types of innovation (Oke Citation2007).

Our paper attempts a contribution that is both rigorous and relevant (Hodgkinson and Rousseau Citation2009) by considering both a theoretical and practical problem when formulating the research focus and positioning the contributions via the implications stated (Nicholson et al. Citation2018). According to Nicholson et al.'s (Citation2018) contribution conceptual framework, this paper makes an incremental and revelatory contribution around key outputs and implications aligned to the developed themes: human factor and culture; client and market; technology; organizational transitions; legal processes; education. The output and implications of these are summarized, presented, and explained in , the thematic map for innovation adoption, which potentially makes a defined contribution to both theory and practice.

Our theoretical underpinning combined RBV (Bititci et al. Citation2011; Neumann and Medbo Citation2009; Papadopoulos et al. Citation2020; Yang et al. Citation2010; Yang Citation2008) and PBV (Bromiley and Rau Citation2014) elements as a starting point, which informed the nature, context, and content of the data collection instrument (e.g. interview guide). As evident from the data, both elements were seen as barriers and opportunities to innovation adoption within the legal firms. Thus, there is a combination of both theories to underpin the context of the paper. This mix of theories (RBV is the predominant one) is an interesting aspect of our work. By informing, guiding, and contextualizing our questions, the theory was critical to the way the results were formulated. has clear references to the key characteristics that define our starting theory (presented in ) as there is a strong focus on human resources and organizational capital issues, the efficiency of legal processes, technology uptake, and knowledge transfer. Therefore, the basic ingredients of informed the components presented in , and the results of our thematic analysis presented in align with the theoretical framework as presented in .

Furthermore, we identified through our qualitative work (and thus these findings need to be validated and triangulated by a follow up quantitative analysis that will give statistically significant results before these can be widely generalizable) that the more established cohorts of legal professionals tend to have different points to make and concerns to raise than those newer to the profession. The former group, as represented by our sample at least, feels overwhelmed by the rapid need for technology adoption. It appears that resistance to change exists within the profession – this does make innovation adoption more complicated. We, therefore, suggest that innovation should be considered more as knowledge transformation than technology adoption. This has the potential to actively engage more legal professionals in uptake.

6. Conclusions

This paper outlines the challenges that legal professionals are facing in their highly competitive, conservative-bound, and ever-changing working environment that could create innovation adoption barriers. It also maps out areas of opportunity for innovation uptake that have not seen enough ‘investment’ yet but are acknowledged by legal professionals as fields where innovative interventions could be timely and meaningful. Our study, which drew from the RBV and PBV elements to inform the nature, context, and content of data collection (focussing on human resources and organizational capital issues, the efficiency of legal processes, technology uptake, and knowledge transfer), thus highlights some of the misconceptions of innovation drawing similarities to Bourke, Roper, and Love (Citation2020) conceptual framework around ‘activities’ and ‘practices’.