Abstract

This paper aims to investigate the nexus of relationships linking firm innovativeness (FI), supply chain agility (SCA), and firm performance (FP). Grounding on Service-Dominant Logic (SDL) and Dynamic Capability View (DCV), this study explores the role of three types of FIs (i.e. service innovativeness, process innovativeness and administrative innovativeness) on SCA and its impact on different dimensions of FP. Limited empirical evidence is available in the SCA literature that examines FI as antecedents of SCA and explores SCA benefits using diverse performance parameters. We test the proposed model using survey data of 238 Australian service firms and analyzed it using partial least square-based structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Our result found that three types of FI are positively related to SCA, and SCA is positively related to all dimensions of FP. Investment in innovation practices are often considered as core practices of service-oriented firms during an uncertain time. Our results offer some useful guidelines for practitioners.

1. Introduction

Over the last one decade, SCA literature mainly concentrates on the usefulness of SCA in generating long-term profitability and competitiveness (Gligor, Holcomb, and Stank Citation2013). As a result, it has become a critical feature of the modern supply chain (SCM) (Dubey et al. Citation2018) to develop quick sensing and response capabilities (Calatayud, Manga, and Christopher Citation2019; Marin-Garcia, Alfalla-Luque, and Machuca Citation2018). These attributes allow firms to meet the ever-growing and ever-changing nature of global market demand to ensure competitiveness in the market (Braunscheidel and Suresh Citation2009). While important SCA has been discussed in the context of a dynamic business environment (Gligor, Holcomb, and Feizabadi Citation2016), it is equally important in a disruptive environment (such as Covid-19) by minimizing the imbalance of demand and supply through its sensing and reconfiguring capabilities. The evolving lockdown rules across the globe compel firms to alter its existing business models and digitalize the relationship to re-energize businesses. This is more prominent in the service sector which has witnessed the most substantial pandemic impact (OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Citation2020Footnote1).

Extant literature on SCA enablers is burgeoning emphasizing mainly on, technical, operational or organizational aspects while ignoring the role of FI. SCA is multidisciplinary (Braunscheidel and Suresh Citation2009; Gligor, Holcomb, and Stank Citation2013; Altay et al. Citation2018) and its corpus is spread across many fields, borrowing from other fields (such as…) is more likely to advance its theoretical development. While recent studies have started to emphasize innovative capability as an enabler of agility at the firm level (e.g. Ashrafi et al. Citation2019; Battistella et al. Citation2017; Ravichandran Citation2018), only Kim and Chai (Citation2017) address this link at the supply chain level. Their study examines the relationship between supplier innovativeness (that mainly focuses on product and service innovativeness) on SCA without taking into account of other types of firm innovativeness. Other related studies such as Chen (Citation2019) discusses the role of innovation and SCA in improving performance of manufacturing firms without discussing the relationship between these two. Grounding on Service Dominant Logic (SDL) and Dynamic Capabilities View (DCV), our study address this lacuna in SCA literature by empirically testing the impact of three types of FI i.e. service innovativeness, process innovativeness and administrative innovativeness on SCA. The underpinning argument for proposing FI as a driver of SCA lies in service firm’s capacity to renew and reconfigure their internal routines and external offerings, hence preserving the value of their critical resource in a dynamic business environment (Eisenhardt and Martin Citation2000). By exploring FI as an enabler of SCA, this study is expected to address Flint, Lusch, and Vargo (Citation2014) call on how to achieve agility through innovation capability. It will also enrich the literature on SCA’s enablers.

While there is rich stream of literature on SCA in manufacturing context (e.g. Alfalla-Luque, Machuca, and Marin-Garcia Citation2018; Ismail and Sharifi Citation2006, Kim and Chai Citation2017, Qrunfleh and Tarafdar Citation2013) SCM scholars paid limited attention in understanding antecedents and impact of SCA in service industry perspective despite its importance (Boon-itt et al. Citation2017). We argue that transferring insights gained from the manufacturing sector to the service context might not be particularly appropriate due to the inherent differences between these two industry practices (Ellram, Tate, and Billington Citation2004; Wang et al. Citation2015). The simultaneity characteristic of most services makes its competitive advantage duplicable which necessitates constant innovation offerings (Weerawardena et al. Citation2020). Therefore, it is surprising that such an essential sector has been fall short of empirical investigation in the SCA literature.

In today’s world, most employment and wealth in developed countries is derived from services (Wang et al. Citation2015). According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)) Citation2018), the service sector in Australia constitutes an important segment of the total business community. It represents 70% of Australia’s GDP and employs four out of every five Australians, confirming its significance in research. From Amazon drone delivery to Uber’s self-driving trucks, innovation can be seen to boost agility in the supply chain (Mckinsey & Company Citation2019). Considering its importance, it is necessary to conduct an empirical investigation on SCA in service sector.

There is no universal consensus regarding suitable measures of SCA performance outcomes. Although financial performance has been argued to be the dominant indicator, it does not demonstrate the current situation of the business environment or prospects for future performance, and return on investment and growth become meaningless when comparing enterprises in different sectors. As such, to pave the way for a comprehensive performance scale, they need to be balanced with more contemporary, intangible and strategy-oriented measures. Some of service best practices can be adopted from manufacturing industry but, in certain circumstances, the service sector needs specific service performance outcomes (Tseng et al. Citation2018), The classical performance issue of service SC practices is difficult to measure due to the fuzzy nature of service and its process being hard to standardize, visualize, design and deliver (Ellram, Tate, and Billington Citation2004), Our study has extended research on the initial SCA-performance proposed by Al Humdan et al. (Citation2020), In their model, Al Humdan et al. (Citation2020) suggested a comprehensive examination of SCA outcomes and incorporated five broad dimensions of firm performance. This research empirically assesses the proposed model. In doing so, we follow the rationale of Cho et al. (Citation2012) who pinpointed the need to develop an appropriate performance measurement in the context of service SCs that captures the essence of service organizational performance that should reflect a balance between financial and non-financial measures.

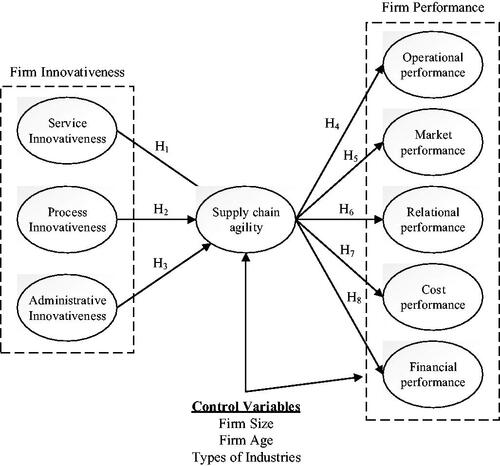

The main focus of this paper is the empirical investigation of the role of FI on SCA using three broad FI dimensions: service (product), process, and administrative innovativeness; and to investigate the association between SCA on five dimensions of firm performance: operational, marketing, relational, cost and financial. Specifically, this study addresses two research questions:

RQ 1: What is the relationship between firm innovativeness and SCA in the service sector?

RQ 2: What is the relationship between SCA and firm performance in the service sector?

2. Literature review

2.1. Firm innovativeness (FI)

Innovativeness is perceived in contemporary literature as a desirable feature of firms as it energizes and augments the probability of survival and continued success (Crossan and Apaydin Citation2010; Hurley, Hult, and Knight Citation2005). It indicates a proactive willingness to abandon old habits and try never-tested ideas (Golgeci and Ponomarov Citation2013). In the last few decades, there has been an unprecedented growth of service industries in advanced economies. Parallelly, there has been a great deal of services management and innovation studies that attempted to articulate the emergence of innovation in services and explain the difficulty in analyzing innovation in service industries (e.g. Avlonitis, Papastathopoulou, and Gounaris Citation2001; Drejer Citation2004; Gallouj and Djellal Citation2011). These scholars agree that the ‘fuzzy’ and ‘curious’ nature of service output makes it difficult to measure or assess innovation. They further illustrate that lack of protection possibilities due to its intangible character of service, and existing innovation theories that are developed around technological innovation in manufacturing activities, might act as a barrier to investigate innovation in service setting. However, these scholars acknowledge the importance of innovation in the service sector. They argue that even innovation does occur radically in service sector, it does not follow a technological imperative, but rather technology is a vehicle to enhance the process.

Innovativeness is a multi-dimensional construct encompassing the adoption of an idea or behaviour, whether pertaining to a device, system, process, policy, program, product or service, that is new to the adopting organization (Maravelakis et al. Citation2006). Innovation research is scattered across multiple disciplines (i.e. marketing, management, business strategy, computer science) and has been conceptualized in myriad ways (Crossan and Apaydin Citation2010). This study adopts the innovation definition by Damanpour’s (Citation1991, p. 556): ‘the generation, development, and implementation of new ideas or behaviours. Innovation can be a new product or service, a new process, a new structure or administrative system, or a new plan or program on organizational members’. According to this definition, innovativeness reflects the development in services, products and systems through interactions between focal firm and its SC member. Three types of innovativeness identified in this study are service, process and administrative innovativeness. Service innovativeness is the firm’s new service offering beyond its usual services, process innovativeness is adopting new initiatives into a firm’s operations system that could result in an improved supply chain responsiveness, while administrative innovativeness refers to changes in organizational structure including the authority, structuring of tasks, recruiting of personnel, and allocating of resources and rewards (Damanpour et al. Citation1996).

2.2. Supply chain agility (SCA)

SCA has evolved as one of the fundamental characteristics needed for a SC to thrive in a turbulent and volatile environment (Feizabadi, Gligor, and Alibakhshi Citation2021; Wu et al. Citation2017). It is a critical success factor for firms to ensure its global competitiveness (Gligor, Holcomb, and Feizabadi Citation2016; Ismail and Sharifi Citation2006). Associated with the sense and response capabilities (Li, Goldsby, and Holsapple Citation2009; Marin-Garcia, Alfalla-Luque, and Machuca Citation2018), SCA has become a sine qua non as a response to the ever-increasing global market requirements for firm competitiveness. In scrutinising the practices to develop SCA, previous studies have addressed technical or operational antecedents such: flexibility (Braunscheidel and Suresh Citation2009), operational alignment (Ismail and Sharifi Citation2006), IT (DeGroote and Marx Citation2013), collaborative relationships (Gligor and Holcomb Citation2012) and sourcing (Power, Sohal, and Rahman Citation2001), with nascent amount of empirical studies on firm innovativeness. By exploring innovativeness as a driver of SCA, this study contributes to literature that discussed enablers of SCA.

In service industries where competition is severe, a key business competence is to acquire market information and respond to these changes in an effective and timely manner (Overby, Bharadwaj, and Sambamurthy Citation2006). Therefore, especially in service industries where uncertainty and unpredictability are normal, the performance of a firm highly depends on its SCA. Research on agility in service industries, however, remains sparse while there has been a pressing need to cope with growing and evolving service sector of the economy (Roth and Menor Citation2009).

3. Theoretical foundation

Theoretical foundation of this study is hinges on the integration of two theories i.e. dynamic capability view (DCV) (Teece, Pisano, and Shuen Citation1997) and service dominant logic (SDL) (Vargo and Lusch Citation2004). Particularly, the underpinning theoretical argument on the relationship between FI and SCA is grounded on DCV and the relationship between SCA and FP is based on SDL. In the following two sections, we are presenting our arguments on how these two theories have adopted in the context of this study.

3.1. Dynamic capability view (DCV)

Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (Citation1997) introduced Dynamic Capability View (DCV) as an extension of Resource-Based View (RBV). Dynamic capabilities (DCs) are defined as ‘the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments’ (Teece, Pisano, and Shuen Citation1997, p. 16). DCV builds on a firm’s ability to rapidly and constantly adapt, reconfigure and innovate. This has led scholars to conceptualize FI as a dynamic capability because innovation capabilities are always allied with change and improvements (e.g. Golgeci and Ponomarov Citation2013; Kindström et al. Citation2013; Rothaermel and Hess Citation2007). DCV has a specific focus on innovation and value creation (Hill and Rothaermel Citation2003; Katkalo, Pitelis, and Teece Citation2010). According to this view, innovation activities are indirectly related to FP through reconfiguring their operational processes or routines which, in turn, generate value for firms (Zahra, Sapienza, and Davidsson Citation2006). We argue that a firm’s SCs need to invest in building innovativeness as a DCs to mitigate vulnerabilities in an uncertain environment, which in turn creates value through SCA to survive in the long run. More importantly, DCV is highly relevant in service sector due to it complicated characteristics embedded in services (Den Hertog, Van der Aa, and De Jong Citation2010).

3.2. Service-dominant logic (SDL)

The premise of Service-Dominant Logic (SDL) is on services and processes rather than products and outcomes (Vargo and Lusch Citation2004), suggesting service provision rather than goods as the basis of economic exchange and focusing on intangible resources such as relationships, dialogue and interaction (Payne et al. Citation2009). SDL views SCs as value co-creation networks (Lusch Citation2011; Maas, Hartmann, and Herb Citation2014) where SC partners create value through blending their complementary operant resources (Maas, Hartmann, and Herb Citation2014) and promote knowledge growth amongst network members via resource deployment and coordination (Tokman and Beitelspacher Citation2011). Lusch, Vargo, and Tanniru (Citation2010) promulgated the natural fit between SCM research and SDL because SCM is concerned with developing and integrating resources to create compelling value propositions.

This study adopts SDL view of SCA based on the following rationale. SCA is centred around the response to dynamic and turbulent markets and customer demands (Ismail and Sharifi Citation2006). These characteristics require highly customized and dynamic market offerings and hence, require a higher degree of SDL that can blend many operant resources (such as knowledge and skills) offered by network actors (Vural Citation2017). SDL lens is useful here as it frames customers as a co-producer/co-creator (Vargo and Lusch Citation2004) and makes them inseparable from value creation process and service provision. From service industry perspective such value co-creation processes strengthen FP, because a key feature of the SDL is the notion that operant resources are the main sources of competitive advantage (Lusch, Vargo, and Fisher Citation2014).

4. Hypotheses development

4.1. FI and SCA

Continuous changes in technology, markets, and customer preference leads to existing services becoming obsolete, thus requiring changes in the firm’s services (Piening and Salge Citation2015). Moreover, trade secrets in the service sector are easily transferable because of the inseparability feature making services non-patentable that necessitates providing customers with constantly new innovative offerings (Biemans and Griffin Citation2018).

Innovation activities requires a close relationship between business partners with a high level of shared knowledge (Roy, Sivakumar, and Wilkinson Citation2004). Such knowledge eases the rapid development of new products and services (Salge Citation2012) and facilitate sensing and responding to market changes. As turbulent environment shrinks product life cycle, SCA provides an effective capability to respond to such dynamic markets (Teece, Pisano, and Shuen Citation1997). Particularly, Yusuf, Sarhadi, and Gunasekaran (Citation1999) propose that innovation is one of the critical factors to achieve operational agility in dynamic markets. Den Hertog, Van der Aa, and De Jong (Citation2010) posited that ‘signaling user needs’ by intensively interacting with clients is the most important capability of service innovation that will help in providing constantly new service offerings and experience, especially in such a highly unpredictable and heterogeneous sector. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Service firm’s service innovativeness positively influences its SCA.

Process innovation represents the ability to reconfigure organizational processes mainly through continual technological innovation, improved operation and distribution processes, improved access to resources, and implementation of cost-reduction operations (Piening and Salge Citation2015). It assists firms to quickly synchronize their processes and capabilities to anticipate and respond to internal and external uncertainties (Teece and Leih Citation2016). The result will be a higher value for customers in terms of getting cheaper, faster, or more flexible products and services (Klingenberg et al. Citation2013). Sometimes these changes are sustainable as key initiatives related to these changes are internally focused, making competitors difficult to imitate (Maine, Lubik, and Garnsey Citation2012). Such change process is prominent in the service sector due to the ease of imitation because services are co-created and co-designed with customers and other partners (Biemans and Griffin Citation2018). Hence, the continuous change and renewal become a requisite (Jansen et al. Citation2006) to develop SCA. On this ground, we predict that:

H2: Service firm’s process innovativeness positively influences its SCA.

Organizational innovations are associated with all the administrative efforts of renewing the organizational routines, procedures, mechanisms, systems, and employee training to promote teamwork, information sharing, collaboration and learning (Gunday et al. Citation2011). It is a behaviour-like activity (Gunday et al. Citation2011; Yamin et al. Citation1997) that will facilitate the process of rapid generation of a new idea and concept development (Messersmith and Guthrie Citation2010). For example, service firms need to continually equip staff with the required and updated expectations, knowledge, and guidelines to operate emerging technologies. Without such expertise, service providers are unable to offer unique services. We argue that firms with expertise in a particular service sector can easily detect new service needs and respond to them through accumulating knowledge (Drejer Citation2004). Power, Sohal, and Rahman (2001) claimed that the promoting continuous improvement and participative management styles could be appropriate ingredients for SCA. Gunasekaran, Lai, and Cheng (Citation2008) stated that achieving SCA requires top management support and employee empowerment. Lyons et al. (Citation2007) used the term ‘service innovation culture,’ indicating the crucial role of organizational innovation in fostering service innovation. Consequently, it is predicted that:

H3: Service firm’s administrative innovativeness positively influences SCA.

4.2. SCA and FP

SCA refers to the operational aspects of creating capability through flexible operations (Braunscheidel and Suresh Citation2009). Brusset (Citation2016) conceptualized SCA as an operational capability focussing on timely and dependable product delivery. Yang (Citation2014) conjectured that collaborative operations improve lead times and handling of customer deliveries. This customer-focused perspective is the underpinning premise of quality (Handfield and Bechtel Citation2002; Samson and Terziovski Citation1999). Firms can meet customer expectations in the delivery process (Stank et al. Citation2003), leading to the improvement of service quality and the reduction of delivery time (Chen, Li, and Arnold Citation2013). This will then create more flexible, dependable and responsive systems, and enhance the service firm’s operations management. SCA maintains a high level of service quality by also developing fixed mindsets and intelligence for all employees and partners regarding the leading practices behind SCA (Fayezi, Zutshi, and O'Loughlin Citation2015). Thus, we predict the following hypothesis:

H4: Service firm’s SCA positively influences its operational performance.

SCA helps firms to convert markets’ threats into opportunities in order to maintain its market share (Li, Goldsby, and Holsapple Citation2009). The sensing feature of SCA makes the relationship with customers very close which eventually leads to detecting demand changes very swiftly, sustain customer loyalty and extends customers’ value (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010). Quick response to customers improves sales volume (Um Citation2017). In a highly customized environment with close contact with customers, SCA can support firms in achieving better business performance through providing high-level customer service (Um Citation2017). With this mind, the implementation of SCA enhances the supply chain customer’s value (Wieland and Wallenburg Citation2013), and accordingly increases the attraction of new customers, opening up of new markets, building customer loyalty (Cao and Zhang Citation2011), capturing market share and enhances the firm’s sales performance. Therefore, we predict the following hypothesis.

H5: Service firm’s SCA positively influences its marketing performance.

SCA aligns the firm’s network and operations to face the market turbulence (Ismail and Sharifi Citation2006). The information-enriched SC (Mason-Jones and Towill Citation1999) results in informational alignment and uncertainty reduction through the establishment of collaborative relationships (Tan et al. Citation2010) and provides service providers with a rapid understanding of customer needs (Stank et al. Citation2003). The sensing capability of SCA quickly helps in maintaining relational rents by seeking informational alignment between partners and an understanding of the exact customer needs. Collaboration is a distinct attribute of SCA (Wu et al. Citation2017) and compatible with the SDL’s core lexicon (Vargo and Lusch Citation2016). Collaboration helps firms to tailor its service offerings to the specific customer requirements by identifying their long-term requirements, expectations, and preferences. Stank, Keller, and Daugherty (Citation2001) argued that external collaboration increases internal collaboration which improves the firm’s service performance. Based on these arguments we proposed the following hypothesis.

H6: Service firm’s SCA positively influences its relational performance.

Sensing market changes allow firms to develop or alter its existing structures, technologies and policies to respond to those market changes efficiently (Ngai, Chau, and Chan Citation2011) as the collaboration between SC partners reduces ordering and transaction costs (Braunscheidel and Suresh Citation2009; Yang Citation2014). Wu et al. (Citation2017) argued that SCA is a tool for cost reduction through operational process integration and information integration. It allows better allocation of the resources and costs leveraging to create value for the final customer, ultimately resulting in superior cost performance. Being the most affected sector during and after Covide-19, cost does matter for service sector. Grounding on these we predict the following hypothesis.

H7: Service firm’s SCA positively influences its cost performance.

Information integration among SC partners not only enables the performance of SCA in developing relational and operational aspects, but also possesses the ability to improve the firm’s profitability (DeGroote and Marx Citation2013; Wu et al. Citation2017). Eckstein et al. (Citation2015) considered SCA not only fulfils customers’ demands swiftly but also helps to enhance the firm’s profitability. Um (Citation2017) argued that SCA improves profitability through enhancing the firm’s daily operations and customer service. SCA enhances profitability through enhancing cost-efficiency stemming from knowledge sharing and enhanced cooperation (Yang Citation2014), leading to asset utilization. Thus, it is predicted:

H8: In the service industry, SCA positively influences the firm’s financial performance.

Conceptual framework of this study is presented in

5. Research methods

5.1. Survey instrument

In this study, we adopted multi-item scales based on existing literature. Six items of SCA were directly adopted from Li, Goldsby, and Holsapple (Citation2009). The dimensions of FI were selected based on the seminal work of OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (Citation2005) and Gunday et al. (Citation2011). Nine items were selected to measure operational performance covering flexibility, quality, and dependability and were adapted from existing studies (e.g. Boyer and Lewis Citation2009; Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010; Huo, Gu, and Prajogo Citation2016; Gadenne and Sharma Citation2009; Prajogo et al. Citation2012; Schoenherr and Swink Citation2012). The scale for marketing performance was adapted from Green, McGaughey, and Casey (Citation2006) and Green and Inman (Citation2005). The relational performance was measured using three items derived from Stank et al. (Citation2003). Three items also were used to measure cost performance adapted from Schoenherr and Swink (Citation2012) and Stank et al. (Citation2003). Lastly, financial performance was measured using a three-item scale derived from Calantone, Cavusgil, and Zhao (Citation2002) and Vickery, Dröge, and Markland (Citation1997). Description of all items are provided in Appendix . All items were measured using a 5-point Likert Scale. A panel of experts from the service sector and academia reviewed the survey questionnaire, after which a pilot and trial run of the questionnaire was carried out.

In this study we used self-reported performance data for two reasons. First, collecting objective oriented performance data is not an easy task. Firms that are not listed in stock-exchange or a private company, they are not bound to disclose this information (Singh, Darwish, and Potočnik Citation2016). So it is a common practice not to share these financial or cost related information with anyone. In this study, majority firms are private business organizations in service industry, therefore it is expected that they would not be willing to share this information. Second, there is no strong empirical evidence to demonstrate that objective oriented data predict firm performance better than subjective oriented data (Singh, Darwish, and Potočnik Citation2016). Empirical evidences showed that subjective and objective performance measures are highly correlated (see Coombs and Gilley Citation2005; Collins and Smith Citation2006). Studies that adopted both subjective and objective performance measures (e.g. Hult et al. Citation2008) revealed that both measures are equally valid and reliable. This further establish that there is minimum bias associated with self-reported performance data.

5.2. Sampling procedure and data collection

The population of interest for this research is the Australian services sector. The choice of the services sector was due to its broad representation in the Australian corporate world. This research has chosen from a diverse base of respondents from the services sector. Respondents were recruited from distribution, finance, insurance, communication, property and business, education, research and health, and community services, amongst others.

The sample frame of this study is service organizations across multiple industries in Australia. It is represented through 2150 firms. The unit of analysis is the focal firm in a service-based supply chain. The questionnaire was directed at the firm’s senior and operational executives (C-level managers). This ensures that responses received from people who possessed extensive knowledge on FI and SCA and have sound understanding on strategic aspects of firm performance.

An online self-administered survey was used to collect data. Social Media Networks (SMNs) were employed as a source of data. SMNs can serve as a means to find relevant informants and convince them to commit to answering the questionnaire (Fieldin et al. Citation2008; Mirabeau, Mignerat, and Grange Citation2013). While pinpointing the problems associated with business surveys in findings and collecting substantial quantities of empirical data from hard-to-reach population, Gregori and Baltar (Citation2013) made it clear that recruiting from SMNs is legitimate and valid, especially as most professionals are familiar with such technology. This study utilized LinkedIn which is principally relevant to this study because it is the most prominent social networking in the business area (Utz Citation2016). Using LinkedIn features, the author started building first degree connections with the requested respondents using inclusion/exclusion criteria in line with the research objectives. Terms such as CEO, GM, MD, CEO, Supply Chain manager were entered, and the search was also limited to those industries belonging to the service sector. This process was conducted progressively each time after receiving a number of completed responses to ensure reasonable response rate. In the repeating process and after tracking the participants’ responses in terms of region and industry, a different state and/or different service industry was selected to fulfil the requested proportionate sample. In order to increase the response rate, a customized message that includes a link to the survey was sent to respondents in all Australian areas and different firms sizes which increased the representativeness. Creating this link was through subscription to a web-based survey host application (SurveyMonkey), Based on a sample size of 2150 firms, 459 valid responses were collected, 238 of which were usable cases (after deleting the missing responses), yielding an overall response rate of 11.11%. This response rate is quite acceptable and realistic in the context of supply chain literature, for example – Prajogo et al. (Citation2012) – response rate 13.2%; Chowdhury, Jayaram, and Prajogo (Citation2017) – response rate 10.2%; and Cousins et al. (Citation2019) – response rate 12.6%.

5.3. Common method bias test

Proactive attempts were undertaken to minimize Common Method Bias (CMB) in this study, including assuring informants’ anonymity, constructing effective and simple questions and optimizing survey layout. Also, the wordings of the survey items were refined to improve their clarity by using expert judgement and q-sort techniques, resulting in tentative item reliability and item validity (Churchill Citation1979), Statistically, two different statistical analyses were also performed in this regard: Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al. Citation2003), and full collinearity assessment (Kock Citation2015). First, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test using all 36 items in the model. Our result showed that no single factor accounted more than 34.18% of the observed variance. Second, we assessed collinearity using variance inflation factors (VIFs) (Kock Citation2015). Our result revealed that all inner VIF values are less than the threshold value of 3.3 (ranging from 1.170 to 2.396). This confirms that CMB is not a concern in this study. Therefore, both tests’ results indicated that CMB is unlikely to influence the interpretation of the results.

5.4. Data analytic approach

In this study we adopted partial least square based structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) technique to analyze our data for three reasons. First, PLS-SEM is suitable for prediction oriented study and theory development compare to covariance based structural equation modelling (CB-SEM) that is appropriate theory testing and confirmation (Akter, Fosso Wamba, and Dewan Citation2017; Hair et al. Citation2019). As we are predicting the impact of different type of FI on supply chain agility and supply chain agility on firm performance, PLS-SEM is appropriate in this context. Second, PLS-SEM does not require to satisfy the normality assumption of variables. We tested the normality of all items using Z-scores of skewness and kurtosis (Hair et al. Citation2019). Our result presented in show that majority items have Zskewness value more than 1.96 and some of the items have Zkurtosis value beyond the threshold of ±1.96. This is a clear violation of normality assumption. Third, as we used 36 items in the model, it requires a sample size of 36 × 10 = 360 (at least) to use CB-SEM. As our sample size is 238 (after removing the missing responses), PLS-SEM is appropriate because it can handle small sample size (Hair et al. Citation2017). In this study we used SmartPLS 3.3.9 to analyze the data.

Table 1. Scale validity and reliability.

6. Data analysis

6.1. Measurement model assessment

We assessed the reliability and validly of all items and scales following the guideline provided by Hair et al. (Citation2017). All items have high factor loading (at p < 0.001) except four items (PInv4, AInv1, OP1, OP3). These items were removed due to low factor loading. We assessed the scale reliability using three measures – composite reliability (CR), Rho_A, and Cronbach’s alpha (α) with a threshold at 0.70 and all scales have reliability higher than 0.70. We assessed convergent validity using average variance extracted (AVE). Our result showed that all AVE values are higher than the threshold 0.50, demonstrating an adequate convergent validity ().

To evaluate the discriminant validity, we adopted three different approaches: Fornell and Larcker criterion, Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) of the correlations, and cross-loadings of the indicator First, the square root of the AVE exceeds the correlations between the measure and all other measures (Chin Citation2010). Second, HTMT of the correlations is less than 0.850 (Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt Citation2015). Both test results are presented in . Third, a measurement model has discriminant validity when the indicators’ loadings are higher against their respective construct compared to other constructs (Chin Citation2010) (). Together, the findings demonstrate acceptable discriminant validity.

Table 2. Discriminant validity test using Fornell–Larcker criterion and HTMT ratio.

Table 3. Discriminant validity test using cross-loading.

6.2. Structural model assessment

To assess the structural model, we first evaluated multicollinearity. The results of this analysis indicated that the inner variance inflation factor (VIF) were much lower than 5, indicating that data were quite distinct from each another (Hair, Ringle, and Sarstedt Citation2013). and shows the full PLS structural model.

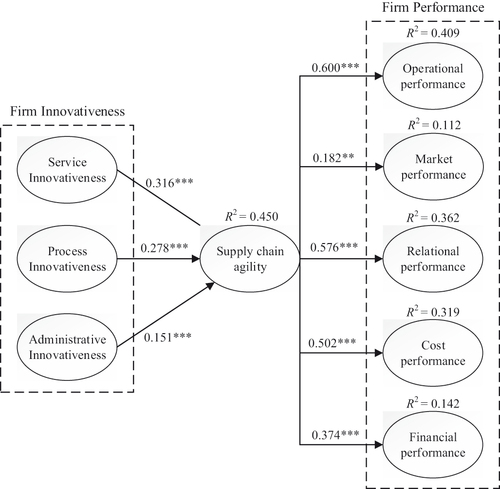

Figure 2. Result of path analysis. Note: (1) ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. (2) For visual clarity, the paths between control variables and dependent variables were not shown in the figure.

Table 4. Hypothesis testing.

The results indicated that service innovativeness (β = 0.316, t = 4.448, BCa CI: 0.177, 0.451), process innovativeness (β = 0.278, t = 4.146, BCa CI: 0.141, 0.408) and administrative innovativeness (β = 0.151, t = 2.943, BCa CI: 0.044, 0.247) are positive and significant predictors of SCA. Therefore, the results supported hypotheses H1, H2 and H3. We also found that SCA is a positive and significant predictor of each performance dimension – i.e. operational performance (β = 0.600, t = 12.215, BCa CI: 0.493, 0.689), marketing performance (β = 0.182, t = 2.654, BCa CI: 0.039, 0.312), relational performance (β = 0.576, t = 10.802, BCa CI: 0.466, 0.675), cost performance (β = 0.502, t = 9.377, BCa CI: 0.378, 0.598) and financial performance (β = 0.374, t = 4.772, BCa CI: 0.204, 0.517). Hence, these results supported hypotheses H4, H5, H6, H7, and H8.

We assessed our proposed model explanatory power using R2 values (Hair et al. Citation2017). Our result showed that R2 value ranges from 11.2 to 45% (). For example – SCA has a R2 value of 45%. It implies that 45% of the total variance in SCA can be explained by service, process, and administrative innovativeness which is considered substantial. Similarly, 40.9% of total variance in operational performance, 36.2% of variance in relational performance, and 31.9% of variance in cost performance can be explained by SCA. Other two performance dimensions i.e. market and financial performance have R2 value of 11.2 and 14.2%, respectively.

We also examined the effect size (f2) to assess the impact of predicting variables on dependent variables (Hair et al. Citation2017). provided all the f2 values of supported hypotheses. Effect size (f2) values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 illustrate small, medium and large effect of predictors on dependent variables (Hair et al. Citation2017). According to these threshold values, we have two large (H4: f2 = 0.542, and H6: f2 = 0.462), one medium (H7: f2 = 0.330) and five small effects (H1: f2 = 0.086; H2: f2 = 0.064; H3: f2 = 0.033; and H5: f2 = 0.033).

We used two firm level control variables – firm size and firm age in the model. Our result presented in showed that these two have no effect on any of the dependent variables of the model except the impact of firm size on market performance (β = −0.190, t = 2.399, BCa CI: −0.342, −0.029). We also used industry level control variables by creating seven dummy variable (using 0 and 1) for seven industry sectors that covers majority of respondents and assessed its impact on all dependent variables. Our result () revealed that none of these industry sectors have any effect on dependent variables except Ind_Consultance on market performance (β = 0.201, t = 2.148, BCa CI: 0.014, 0.382).

6.3. Robustness check

We assessed the robustness of the model by conducting two supplementary analyses i.e. potential non-linearity effect and endogeneity (Ozanne et al. Citation2022; Sarstedt et al. Citation2020). We checked the potential nonlinearities in the model using two tests (Sarstedt et al. Citation2020). First, we conducted Ramsey’s (Citation1969) RESET test in RStudio using latent variable scores extracted from original model’s PLS-SEM Algorithm (Ozanne et al. Citation2022). We presented our result in and it showed that none of the six partial regression analysis were significant. Therefore, there is no evidence of nonlinearity in the model. In the second test, we assessed the quadratic effect of SInv, PInv, and AInv on SCA, SCA on OP, MP, RP, CP and FP. Our result revealed that none of these quadratic effects are significant which suggested that our linear effects are robust.

Table 5. Assessment of nonlinearity effects.

We checked the endogeneity of the model following the procedure suggested by Hult et al. (2018). We adopted Gaussian copula method (Park and Gupta Citation2012) to assess endogeneity in Rstudio. We extracted the latent variable scores of all scales from SmartPLS and used it as input. We ensured that none of the independent variables (i.e. SInv, PInv, AInv, and SCA) are normally distributed by following Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with Lilliefors correction. In the next step, we established twelve regression models in Rstudio program with all possible combinations of Gaussian copulas. Endogeneity problem occurs if Gaussian copula is significant (i.e. p < 0.05). Our result () shows that none of these Gaussian copulas are significant which suggest that endogeneity is not a problem in this model. This further ensures the robustness of our model.

Table 6. Assessment of endogeneity.

6.4. Post hoc analysis – mediation test

As a post hoc analysis we conducted mediation test to identify broadly that SCA mediates (fully or partially) the relationship between different types of FI and its different performance dimensions. In the model, we have three independent variables related to innovativeness (i.e. service innovativeness, process innovativeness, and administrative innovativeness) and five dependent variables related to firm performance (operations, market, relational, cost and financial). This led us to conduct 5 × 3 = 15 mediation tests following the two-stage procedure suggested by Nitzl, Roldan, and Cepeda (Citation2016). In the first stage, we assessed the significance of indirect effect and in the second stage, we assessed the significance of direct effect to identify the nature of mediation (Nitzl, Roldan, and Cepeda Citation2016). We presented the mediation test result in Appendix . Our result revealed that in 9 out 15 tests SCA partially or fully mediates the reltionship between different types of innovativenesses and firm performances. In the remaining 6 tests, we could not find any mediation effect of SCA. These findings broadly suggest the importance of SCA in extracting performance benefits of various aspects of FI.

7. Discussion

Despite an increasing number of empirical investigations on SCA enablers and its consequences, the vast majority of these studies have adopted an unbalanced view of firm performance. This gap is more visible when explored existing SCA literature that concentrates mainly on manufacturing setting, leaving the service sector virtually unexplored. To our best knowledge, there is limited empirical evidence that investigates innovativeness as a driver of SCA and assess the impact of SCA on diverse performance parameter in the Australian service sector.

7.1. Theoretical implications

Theorizing SCA as a dynamic capability, the study reveal that all dimensions of FI are directly linked to SCA. This corroborates recent studies that examined innovative capability as an enabler of agility at the firm level (Ashrafi et al. Citation2019; Battistella et al. Citation2017; Ravichandran Citation2018) and at the SC level (Kim and Chai Citation2017). Despite the importance of innovativeness, scant research has considered it at the SC context. Our work attempts to extend the effect of FI in enhancing SCA. For instance, if a service firm is mastering the frequent introduction of new services and in multiple ranges, it will help members across the SC to anticipate and respond to the accelerated changes promptly which will keep them abreast of any changes, especially as service firms operate in a highly unpredictable environment. Similar outcomes will occur if the firm adopts closely related technologies or flexible administration procedures.

SCA positively influence all dimensions of FP. This is in line with previous empirical works that have found a positive association between SCA and each of the operational performances (Blome, Schoenherr, and Rexhausen Citation2013; DeGroote and Marx 2013; Eckstein et al. Citation2015; Gligor and Holcomb Citation2012), marketing performance (Liu et al. Citation2013; Whitten, Green, and Zelbst Citation2012), relational performance (Gligor and Holcomb Citation2012), and cost performance (Eckstein et al. Citation2015). Although our study partially contradicts recent studies that have found no direct association between SCA and financial performance (e.g. Gligor, Esmark, and Holcomb Citation2015), while these studies are supported by good sample size collected from multi-industry senior-level managers, the measurement of firm performance could be inconclusive because they substantiated the financial performance of the firm by employing only one construct (i.e. ROA) and ignoring other widely recognized measures such as profitability or (ROI), This extensive understanding of firm performance offers a more inclusive picture regarding the expected benefits of SCA.

SCA allows firms to accelerate time to market, eliminate waste and errors, and reduce operational cost. Unlike other scholars, this study has found that it is the lean supply chain which is highly associated with the lowest cost compared to SCA (e.g. Naylor, Naim, and Berry Citation1999; Qrunfleh and Tarafdar Citation2013), and in contrast to Alfalla-Luque, Machuca, and Marin-Garcia (Citation2018) findings that showed no positive impact on cost competitive advantage. This is possibly due to their manufacturing-oriented sample that adopted lean paradigm. This study finds strong evidence that the SCA is also linked to the low cost and thus extends the understanding of the SCA-cost performance link (Chen, Wang, and Chan Citation2017). Lacking agility will expose firms to diminished competitive advantage as the risk of not meeting customer demands. This will increase system-wide costs to maintain the desired market share. Although cost is not considered a market winner for agility, our study demonstrates that SCA should not be taken merely as the ability to manage market changes rapidly, but also to cope with a more cost-effective way to gain a competitive advantage. This is consistent with prior research findings in the manufacturing sector (e.g. Eckstein et al. Citation2015; Gligor, Esmark, and Holcomb Citation2015; Yang 2014),

As a post hoc analysis, we conducted mediation test to understand the critical role of SCA in extracting performance benefits of various aspects of FI. The relationship between service innovativeness and relational performance is fully mediated through SCA. Also, SCA is fully mediating the relationship between process innovativeness and cost performance. Finally, SCA is found to fully mediate the relationship between administrative innovativeness and both relational and cost performance. The results support the notion that innovativeness, through its multiple aspects, plays an instrumental role in enhancing the firm’s cost and relational performance and that this relationship is through SCA. To our best knowledge, this finding extends the SCA literature by delivering a unique direction in the relationship between innovativeness and the firm performance that has not been investigated before. The findings encourage managers in service firms to more confidently invest on SCA to generate better revenue.

7.2. Managerial implications

The results convey an important message to managers of the importance of innovativeness to engender agility in the supply chain through different lenses. Taking an SDL, although subject to further examination, provides a starting point for understanding the value co-creation and the service ecosystem of sense and response networks and offers some organizations an opportunity to take on the role of system integrators. This is of great managerial relevance because SCA works well in turbulent environments that provide greater incentives for value co-creation that necessitates integrating the various actors’ various operant resources. Firms guided by an SDL take a more holistic service-centred view where all actors contribute to the value propositions. The SDL perspectives inform practitioners who seek to adopt SCA to invest more in building relational assets and intensively involving customers as the final beneficiaries who define value in which the core of most service firms lies.

Executives in service firms need to know how agility in SC is enabled. Examining the role of FI, is extremely useful in their quest to manage the ever-changing dynamics and interactions in the SC. By identifying the various dimensions of FI, this study helps managers to gain a better understanding of factors that contribute to increase SCA, during uncertainty environment. The services innovation dimension, in particular, has the greatest impact on developing SCA. Developing and offering customized new services constantly should be managers’ priority to improve SCA. Renewing work methods in a more cost-effective and sustainable way is key for service managers.

Secondly, the SCA-firm performance link results provide some clarity regarding the expected outcomes of SCA. Business professionals and managers are in a never-ending quest to understand relationships and find ways to improve performance. This study suggests a comprehensive look at the firm performance of SCA becoming a valuable tool to assist in measurement, estimation, assessment, and benchmarking key drivers in order to improve the overall performance. This study conveys an essential message to managers to be agile. Therefore, firms might find that they can reduce risk and improve their cost and financial performance by promoting SCA.

Finally, the study alerts managers to the realization of the importance of agility. It is a key factor in determining the success of the business and maintaining the firm’s competitive advantages in an uncertain environment, such as that of COVID-19. Adopting an agile philosophy within the SC amid crises provides managers with the ability to restructure sources and operational systems to adapt to customer needs while nurturing a growth mindset. Agility helps a firm reduce operational risk and improve its financial performance because it views changes not as expected and manageable, but as a chance to disrupt. This is evident from many companies being transitioned to an entirely virtual workplace in response to the pandemic.

The mediation analyses suggest important guidelines for managers to maintain relational and cost performance and thus satisfy shareholders by mainly maintaining the sense and response capabilities of the firm. This result alerts managers to recognize the dynamic conceptualization of SCA and act quickly internally and externally with each partner across the supply chain, which will eventually aid in creating and sustaining their competitive advantage.

8. Conclusion

Our research contributes to the empirical aspect of the SDL and DCV by validating a multidisciplinary state-of-the-art conceptual model from SC, innovation, and strategy literature streams. From a theoretical perspective, the role of SDL in explaining SCM is discussed in the literature, but not in relation to the agility concept. This study argues that integrating SDL with DCV is relevant for understanding SCA’s new enablers and performance implications. Embracing an SDL may, therefore, lead to a better understanding of the factors influencing SCA, departing from the conventional thinking of previous research that defined innovation as an outcome of a broader context of value attenuation and customer value co-creation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the pilot study in SCA's research stream to utilize the SDL, integrated with a resource theory.

econdly, this study contributes to the growing literature of SCM and innovation by investigating firm innovativeness and SCA using a large data set in Australia. The study found that all dimensions of firm innovativeness are directly linked to SCA. An attempt was made to bridge the gap between operations management and innovation literature and providing unique empirical contribution. It responds to the question, what enables SCs to sense and respond rapidly to uncertainty, ambiguity and disruption? from an innovation perspective that has been ignored in the previous literature. By responding to Al Humdan et al. (Citation2020) who encouraged the examination of the role of innovation in amplifying SCA, this study enriches the literature by showing the different effect of firm innovativeness on SCA where service innovation ranks first.

Recognizing the importance of consistent and reliable performance measures and outcomes for SCA, this study empirically assesses Al Humdan et al. (Citation2020) performance model. It makes another original contribution by indicating that SCA is highly associated with all five dimensions of firm performance. Whereas most previous SCA studies examined one or two types of performance, this study supplements and deepens our understanding of the SCA performance implications. It confirms that SCA, through collaboration and integration, allows better allocation of the resources and cost leveraging to create value for the final customer, ultimately resulting in waste elimination and directly contributing to the cost performance.

Finally, the simultaneity feature of services where both the service provider and the customer (and sometimes other business partners) produce and design the service at the same time makes barriers to entry relatively low due to ease of imitation (Brandon-Jones et al. Citation2016) making competition in services fiercer than other industries and thus agility is of paramount importance. Agility in service industries is a key business competence in acquiring market information and responding to changes in a useful and timely manner (Overby, Bharadwaj, and Sambamurthy Citation2006), From the financial sector that needs to deal with several high-impact regulations urgently, the intense competition in commodity services where prices are under pressure, or the highly customized services that need to be put in markets in ever-shorter time in telecommunications, SCA can be seen as always necessary. Prior comparable research has been quite extensively directed to the manufacturing sectors, which leaves the understanding of SCA in the service sector under-researched. This study provides timely insights into SCA in the Australian competitive service environment and contributes to the knowledge needed by manufacturers of the future to compete in the service economy.

While our research has provided some intriguing insight, limitations exist, which also reflect possible avenues for future studies. First, in our conceptual model we only investigate the direct effect. For example – we tested the direct effect of three dimensions of FI on SCA and SCA on FP without considering any boundary conditions. Future research can identify the potential boundary condition that can strengthen or weaken these effects. Second, although the SDL is found to be compatible with the core lexicon of SCA, further investigation is needed. Third, this study collected data at one point of time rather than two or three different time period. To test the proposed model. Future research can replicate this model using longitudinal study. Fourth, this study collected data using single informant. Future research can adopt a multiple-informant research design to obtain a more accurate evaluation of variables that represent inter-firm processes and relationships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eias AI Humdan

Eias AI Humdan is Researcher and lecturer in management sciences, has been doing higher educational consultancies and teaching for 15 years. Graduated from Exeter University in 2005 with MSc in International Business, followed by a full-time academic manager for many academic institutions. Scored the top grade in MRes in Management in 2017 after having a PhD in operations management, both at Macquarie University – Sydney, Australia. Currently is an assistant professor at Rabdan Academy UAE.

Yangyan Shi

Yangyan Shi is a senior faculty member at Macquarie Business School, Macquarie University, a Chartered Member of CILT-A, and a member of the Centre for Supply Chain Management at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. He had several years of industrial experience in logistics and supply chain management in Australia, New Zealand, China and the UK. He has been actively publishing his academic research in leading international journals, including IJOPM, IJPE, IJPR, SCMIJ, IJPDLM, etc. His research interests include operations management, logistics, supply chain management, procurement, and third-party logistics.

Masud Behina

Masud Behnia received the B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. degrees from Purdue University, Washington DC, USA.,He had an extensive period in the power industry. He has worked in experimental and numerical fluid mechanics and heat transfer for more than 25 years. He has authored many research articles/books related to Operations Management & Research. He has had publications in journals and conferences, including more than 400 refereed papers. Worked in Sydney, Australia as a professor of management and an executive dean. He is currently a senior research fellow, CTR, Stanford University.

Mesbahuddin Chowdhury

Mesbahuddin Chowdhury, PhD, is a Senior lecturer (above the bar) of Operations and Supply Chain Management at UC Business School, University of Canterbury, New Zealand. He received his PhD in Supply Chain Management from Monash University, Australia in 2012 and served as a Research Fellow at Monash University for 2 years. Dr. Chowdhury has the experience in teaching Operations Management, Purchasing and Supply Chain Management, Business Research Method and Business mathematics. His current research interests are on buyer-supplier relationship, social capital, supply chain resilience, organisational resilience, certification, knowledge sharing and health and safety management practice.

Notes

1 OCED is an intergovernmental economic organisation with widely accepted international economic guidelines concerning developed economies.

References

- Akter, S., S. Fosso Wamba, and S. Dewan. 2017. “Why PLS-SEM is Suitable for Complex Modelling? An Empirical Illustration in Big Data Analytics Quality.” Production Planning & Control 28 (11–12): 1011–1021. doi:10.1080/09537287.2016.1267411.

- Al Humdan, E., Y. Shi, M. Behnia, and A. Najmaei. 2020. “Supply Chain Agility: A Systematic Review of Definitions, Enablers and Performance Implications.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 50 (2): 287–312. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-06-2019-0192.

- Alfalla-Luque, R., J. A. Machuca, and J. A. Marin-Garcia. 2018. “Triple-A and Competitive Advantage in Supply Chains: empirical Research in Developed Countries.” International Journal of Production Economics 203: 48–61. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.05.020.

- Altay, N., A. Gunasekaran, R. Dubey, and S. J. Childe. 2018. “Agility and Resilience as Antecedents of Supply Chain Performance under Moderating Effects of Organizational Culture within the Humanitarian Setting: A Dynamic Capability View.” Production Planning & Control 29 (14): 1158–1174. doi:10.1080/09537287.2018.1542174.

- Ashrafi, A., A. Z. Ravasan, P. Trkman, and S. Afshari. 2019. “The Role of Business Analytics Capabilities in Bolstering Firms’ Agility and Performance.” International Journal of Information Management 47: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.12.005.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2018. “Australian Industry, cat. no. 8155.0.” https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/8155.0

- Avlonitis, G. J., P. G. Papastathopoulou, and S. P. Gounaris. 2001. “An Empirically-Based Typology of Product Innovativeness for New Financial Services: Success and Failure Scenarios.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 18 (5): 324–342. doi:10.1111/1540-5885.1850324.

- Battistella, C., A. F. De Toni, G. De Zan, and E. Pessot. 2017. “Cultivating Business Model Agility through Focused Capabilities: A Multiple Case Study.” Journal of Business Research 73: 65–82. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.12.007.

- Biemans, W., and A. Griffin. 2018. “Innovation Practices of B2B Manufacturers and Service Providers: Are They Really Different?” Industrial Marketing Management 75: 112–124. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.04.008.

- Blome, C., T. Schoenherr, and D. Rexhausen. 2013. “Antecedents and Enablers of Supply Chain Agility and Its Effect on Performance: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective.” International Journal of Production Research 51 (4): 1295–1318. doi:10.1080/00207543.2012.728011.

- Boon-Itt, S., C. Y. Wong, and C. W. Wong. 2017. “Service Supply Chain Management Process Capabilities: Measurement Development.” International Journal of Production Economics 193: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.06.024.

- Boyer, K. K., and M. W. Lewis. 2009. “Competitive Priorities: investigating the Need for Trade‐Offs in Operations Strategy.” Production and Operations Management 11 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2002.tb00181.x.

- Brandon-Jones, A., M. Lewis, R. Verma, and M. C. Walsman. 2016. “Examining the Characteristics and Managerial Challenges of Professional Services: An Empirical Study of Management Consultancy in the Travel, Tourism, and Hospitality Sector.” Journal of Operations Management 42: 9–24.

- Braunscheidel, M. J., and N. C. Suresh. 2009. “The Organisational Antecedents of a Firm’s Supply Chain Agility for Risk Mitigation and Response.” Journal of Operations Management 27 (2): 119–140. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2008.09.006.

- Brusset, X. 2016. “Does Supply Chain Visibility Enhance Agility?” International Journal of Production Economics 171: 46–59. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.10.005.

- Calantone, R. J., S. T. Cavusgil, and Y. Zhao. 2002. “Learning Orientation, Firm Innovation Capability, and Firm Performance.” Industrial Marketing Management 31 (6): 515–524. doi:10.1016/S0019-8501(01)00203-6.

- Calatayud, A., J. Manga, and M. Christopher. 2019. “The Self-Thinking Supply Chain.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 24 (1): 22–38. doi:10.1108/SCM-03-2018-0136.

- Cao, M., and Q. Zhang. 2011. “Supply Chain Collaboration: Impact on Collaborative Advantage and Firm Performance.” Journal of Operations Management 29 (3): 163–180. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2010.12.008.

- Chen, C. 2019. “Developing a Model for Supply Chain Agility and Innovativeness to Enhance Firms’ Competitive Advantage.” Management Decision 57 (7): 1511–1534. doi:10.1108/MD-12-2017-1236.

- Chen, C., P. Li, and T. Arnold. 2013. “Effects of Collaborative Communication on the Development of Market-Relating Capabilities and Relational Performance Metrics in Industrial Markets.” Industrial Marketing Management 42 (8): 1181–1191. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.03.014.

- Chen, X., X. J. Wang, and H. K. Chan. 2017. “Manufacturer and Retailer Coordination for Environmental and Economic Competitiveness: A Power Perspective.” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 97: 268–281. doi:10.1016/j.tre.2016.11.007.

- Chin, W. W. 2010. “How to Write up and Report PLS Analyses.” In Handbook of Partial Least Squares, edited by V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, and H. Wang, 655–690. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Cho, D. W., Y. H. Lee, S. H. Ahn, and M. K. Hwang. 2012. “A Framework for Measuring the Performance of Service Supply Chain Management.” Computers & Industrial Engineering 62 (3): 801–818. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2011.11.014.

- Chowdhury, M., J. Jayaram, and D. Prajogo. 2017. “The Influence of Socialisation and Absorptive Capacity on Buyer’s Innovation Performance.” International Journal of Production Research 55 (23): 7022–7039. doi:10.1080/00207543.2017.1346321.

- Churchill, G. A. 1979. “A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs.” Journal of Marketing Research 16 (1): 64–73. doi:10.1177/002224377901600110.

- Collins, C. J., and K. G. Smith. 2006. “Knowledge Exchange and Combination: The Role of Human Resource Practices in the Performance of High-Technology Firms.” Academy of Management Journal 49 (3): 544–560. doi:10.5465/amj.2006.21794671.]

- Coombs, J. E., and K. M. Gilley. 2005. “Stakeholder Management as a Predictor of CEO Compensation: Main Effects and Interactions with Financial Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 26 (9): 827–840. doi:10.1002/smj.476.

- Cousins, P. D., B. Lawson, K. J. Petersen, and B. Fugate. 2019. “Investigating Green Supply Chain Management Practices and Performance: The Moderating Roles of Supply Chain Ecocentricity and Traceability.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 39 (5): 767–786. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-11-2018-0676.

- Crossan, M. M., and M. Apaydin. 2010. “A Multi‐Dimensional Framework of Organisational Innovation: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Journal of Management Studies 47 (6): 1154–1191. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00880.x.

- Damanpour, F. 1991. “Organisational Innovation: A Meta-Analysis of Effects of Determinants and Moderators.” Academy of Management Journal 34 (3): 555–590. doi:10.2307/256406.

- Damanpour, F. 1996. “Organisational Complexity and Innovation: developing and Testing Multiple Contingency Models.” Management Science 42 (5): 693–716. doi:10.1287/mnsc.42.5.693.

- DeGroote, S. E., and T. G. Marx. 2013. “The Impact of IT on Supply Chain Agility and Firm Performance: An Empirical Investigation.” International Journal of Information Management 33 (6): 909–916. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2013.09.001.

- Den Hertog, P., W. Van der Aa, and M. W. De Jong. 2010. “Capabilities for Managing Service Innovation: Towards a Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Service Management 21 (4): 490–514. doi:10.1108/09564231011066123.

- Drejer, I. 2004. “Identifying Innovation in Surveys of Services: A Schumpeterian Perspective.” Research Policy 33 (3): 551–562. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2003.07.004.

- Dubey, R., N. Altay, A. Gunasekaran, C. Blome, T. Papadopoulos, and S. J. Childe. 2018. “Supply Chain Agility, Adaptability and Alignment: Empirical Evidence from the Indian Auto Components Industry.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 38 (1): 129–148. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-04-2016-0173.

- Eckstein, D., M. Goellner, C. Blome, and M. Henke. 2015. “The Performance Impact of Supply Chain Agility and Supply Chain Adaptability: The Moderating Effect of Product Complexity.” International Journal of Production Research 53 (10): 3028–3046. doi:10.1080/00207543.2014.970707.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., and J. A. Martin. 2000. “Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They?” Strategic Management Journal 21 (10–11): 1105–1121. doi:10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID-SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E.

- Ellram, L. M., W. L. Tate, and C. Billington. 2004. “Understanding and Managing the Services Supply Chain.” The Journal of Supply Chain Management 40 (4): 17–32. doi:10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00176.x.

- Fayezi, S., A. Zutshi, and A. O'Loughlin. 2015. “How Australian Manufacturing Firms Perceive and Understand the Concepts of Agility and Flexibility in the Supply Chain.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 35 (2): 246–281. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-12-2012-0546.

- Feizabadi, J., D. M. Gligor, and S. Alibakhshi. 2021. “Examining the Synergistic Effect of Supply Chain Agility, Adaptability and Alignment: A Complementarity Perspective.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 26 (4): 514–531. doi:10.1108/SCM-08-2020-0424.

- Fieldin, N. G., R. M. Lee, and G. Blank. 2008. The Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods, London: Sage.

- Flint, D. J., R. F. Lusch, and S. L. Vargo. 2014. “The Supply Chain Management of Shopper Marketing as Viewed through a Service Ecosystem Lens.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 44 (1/2): 23–38. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-12-2012-0350.

- Flynn, B. B., B. Huo, and X. Zhao. 2010. “The Impact of Supply Chain Integration on Performance: A Contingency and Configuration Approach.” Journal of Operations Management 28 (1): 58–71. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2009.06.001.

- Gadenne, D., and B. Sharma. 2009. “An Investigation of the Hard and Soft Quality Management Factors of Australian SMEs and Their Association with Firm Performance.” International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 26 (9): 865–880. doi:10.1108/02656710910995064.

- Gallouj, F., and F. Djellal. 2011. The Handbook of Innovation and Services: A Multi-Disciplinary Perspective. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Gligor, D. M., C. L. Esmark, and M. C. Holcomb. 2015. “Performance Outcomes of Supply Chain Agility: when Should You Be Agile?” Journal of Operations Management 33-34 (1): 71–82. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2014.10.008.

- Gligor, D. M., and M. C. Holcomb. 2012. “Antecedents and Consequences of Supply Chain Agility: Establishing the Link to Firm Performance.” Journal of Business Logistics 33 (4): 295–308. doi:10.1111/jbl.12003.

- Gligor, D. M., M. C. Holcomb, and J. Feizabadi. 2016. “An Exploration of the Strategic Antecedents of Firm Supply Chain Agility: The Role of a Firm’s Orientations.” International Journal of Production Economics 179: 24–34. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.05.008.

- Gligor, D. M., M. C. Holcomb, and T. P. Stank. 2013. “A Multidisciplinary Approach to Supply Chain Agility: conceptualisation and Scale Development.” Journal of Business Logistics 34 (2): 94–108. doi:10.1111/jbl.12012.

- Golgeci, I., and S. Y. Ponomarov. 2013. “Does Firm Innovativeness Enable Effective Responses to Supply Chain Disruptions? An Empirical Study.” Supply Chain Management18 (6): 604–617. doi:10.1108/SCM-10-2012-0331.

- Green, K. W., R. McGaughey, and K. M. Casey. 2006. “Does Supply Chain Management Strategy Mediate the Association Between Market Orientation and Organisational Performance?” Supply Chain Management 11 (5): 407–414. doi:10.1108/13598540610682426.

- Green, K. W., and R. Inman. 2005. “Using a Just-In-Time Selling Strategy to Strengthen Supply Chain Linkages.” International Journal of Production Research 43 (16): 3437–3453. doi:10.1080/00207540500118035.

- Gregori, A., and F. Baltar. 2013. “Ready to Complete the Survey on Facebook Web 2.0 as a Research Tool in Business Studies.” International Journal of Market Research 55 (1): 131–148. doi:10.2501/IJMR-2013-010.

- Gunasekaran, A., K. H. Lai, and T. E. Cheng. 2008. “Responsive Supply Chain: A Competitive Strategy in a Networked Economy.” Omega 36 (4): 549–564. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2006.12.002.

- Gunday, G., G. Ulusoy, K. Kilic, and L. Alpkan. 2011. “Effects of Innovation Types on Firm Performance.” International Journal of Production Economics 133 (2): 662–676. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.05.014.

- Hair, J. F., C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2013. “Editorial: partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance.” Long Range Planning 46 (1–2): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001.

- Hair, J. F., W. C. Black, B. J. Babin, and R. E. Anderson. 2019. Multivariate Data Analysis. 8th ed. Andover: Cengage Brain.

- Hair, J. F., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Handfield, R. B., and C. Bechtel. 2002. “The Role of Trust and Relationship Structure in Improving Supply Chain Responsiveness.” Industrial Marketing Management 31 (4): 367–382. doi:10.1016/S0019-8501(01)00169-9.

- Henseler, J., C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2015. “A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modelling.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43 (1): 115–135. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8.

- Hill, C. W., and F. T. Rothaermel. 2003. “The Performance of Incumbent Firms in the Face of Radical Technological Innovation.” The Academy of Management Review 28 (2): 257–274. doi:10.2307/30040712.

- Hult, G. T. M., D. J. Ketchen, D. A. Griffith, B. R. Chabowski, M. K. Hamman, B. J. Dykes, W. A. Pollitte, and S. T. Cavusgil. 2008. “An Assessment of the Measurement of Performance in International Business Research.” Journal of International Business Studies 39 (6): 1064–1080. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400398.

- Huo, B., M. Gu, and D. Prajogo. 2016. “Flow Management and Its Impacts on Operational Performance.” Production Planning & Control 27 (15): 1233–1248. doi:10.1080/09537287.2016.1203468.

- Hurley, R. F., G. T. Hult, and G. A. Knight. 2005. “Innovativeness and Capacity to Innovate in a Complexity of Firm-Level Relationships: A Response to Woodside (2004).” Industrial Marketing Management 34 (3): 281–283. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.07.006.

- Ismail, H., and H. Sharifi. 2006. “A Balanced Approach to Building Agile Supply Chains.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 36 (6): 431–444. doi:10.1108/09600030610677384.

- Jansen, J. J. P., F. A. J. Van Den Bosch, and H. W. Volberda. 2006. “Exploratory Innovation, Exploitative Innovation, and Performance: Effects of Organizational Antecedents and Environmental Moderators.” Management Science 52 (11): 1661–1674. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0576.

- Katkalo, V. S., C. N. Pitelis, and D. J. Teece. 2010. “Introduction: On the Nature and Scope of Dynamic Capabilities.” Industrial and Corporate Change 19 (4): 1175–1186. doi:10.1093/icc/dtq026.

- Kim, M., and S. Chai. 2017. “The Impact of Supplier Innovativeness, Information Sharing and Strategic Sourcing on Improving Supply Chain Agility: Global Supply Chain Perspective.” International Journal of Production Economics 187: 42–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.02.007.

- Kindström, D., C. Kowalkowski, and E. Sandberg. 2013. “Enabling Service Innovation: A Dynamic Capabilities Approach.” Journal of Business Research 66 (8): 1063–1073. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.03.003.

- Klingenberg, B., R. Timberlake, T. G. Geurts, and R. J. Brown. 2013. “The Relationship of Operational Innovation and Financial Performance: A Critical Perspective.” International Journal of Production Economics 142 (2): 317–323. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2012.12.001.

- Kock, N. 2015. “Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach.” International Journal of e-Collaboration 11 (4): 1–10. doi:10.4018/ijec.2015100101.

- Li, X., T. J. Goldsby, and C. W. Holsapple. 2009. “Supply Chain Agility: Scale Development.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 20 (3): 408–424. doi:10.1108/09574090911002841.

- Liu, H., W. Ke, K. K. Wei, and Z. Hua. 2013. “The Impact of IT Capabilities on Firm Performance: The Mediating Roles of Absorptive Capacity and Supply Chain Agility.” Decision Support Systems 54 (3): 1452–1462. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.12.016.

- Lusch, R. F. 2011. “Reframing Supply Chain Management: A Service‐Dominant Logic Perspective.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 47 (1): 14–18. doi:10.1111/j.1745-493X.2010.03211.x.

- Lusch, R. F., S. L. Vargo, and M. Tanniru. 2010. “Service, Value Networks and Learning.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 38 (1): 19–31. doi:10.1007/s11747-008-0131-z.

- Lusch, R. F., S. L. Vargo, and R. Fisher. 2014. “Drawing on Service-Dominant Logic to Expand the Frontier of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 44 (1/2): 1–5. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-07-2013-0209.

- Lyons, R. K., J. A. Chatman, and C. K. Joyce. 2007. “Innovation in Services: Corporate Culture and Investment Banking.” California Management Review 50 (1): 174–191. doi:10.2307/41166422.

- Mckinsey & Company. 2019. “The Missing Lever in Service Operations: Agility.” https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/operations-blog/the-missing-lever-in-service-operations.

- Maine, E., S. Lubik, and E. Garnsey. 2012. “Process-Based vs. product-Based Innovation: Value Creation by Nanotech Ventures.” Technovation 32 (3–4): 179–192. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2011.10.003.

- Marin-Garcia, J. A., R. Alfalla-Luque, and J. A. Machuca. 2018. “A Triple-A Supply Chain Measurement Model: Validation and Analysis.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 48 (10): 976–994. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-06-2018-0233.

- Mason-Jones, R., and D. R. Towill. 1999. “Total Cycle Time Compression and the Agile Supply Chain.” International Journal of Production Economics 62 (1–2): 61–73. doi:10.1016/S0925-5273(98)00221-7.

- Maas, S., E. Hartmann, and S. Herb. 2014. “Supply Chain Services from a Service-Dominant Perspective: A Content Analysis.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 44 (1/2): 58–79. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-11-2012-0332.

- Maravelakis, E., N. Bilalis, A. Antoniadis, K. A. Jones, and V. Moustakis. 2006. “Measuring and Benchmarking the Innovativeness of SMEs: A Three-Dimensional Fuzzy Logic Approach.” Production Planning & Control 17 (3): 283–292. doi:10.1080/09537280500285532.

- Messersmith, J. G., and J. P. Guthrie. 2010. “High Performance Work Systems in Emergent Organisations: implications for Firm Performance.” Human Resource Management 49 (2): 241–264. doi:10.1002/hrm.20342.

- Mirabeau, L., M. Mignerat, and C. Grange. 2013. “The Utility of Using Social Media Networks for Data Collection in Survey Research.” International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2013): Reshaping Society through Information Systems Design, Milan, Italy, p. 4201.

- Naylor, J. B., M. M. Naim, and D. Berry. 1999. “Leagility: integrating the Lean and Agile Manufacturing Paradigms in the Total Supply Chain.” International Journal of Production Economics 62 (1–2): 107–118. doi:10.1016/S0925-5273(98)00223-0.

- Ngai, E. W., D. C. Chau, and T. L. Chan. 2011. “Information Technology, Operational, and Management Competencies for Supply Chain Agility: findings from Case Studies.” The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 20 (3): 232–249. doi:10.1016/j.jsis.2010.11.002.

- Nitzl, C., J. L. Roldan, and G. Cepeda. 2016. “Mediation Analysis in Partial Least Squares Path Modeling.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 116 (9): 1849–1864. doi:10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302.