Abstract

Management innovations are an important source of competitive advantage, but we lack knowledge on the implementation process, not least in small- and medium-sized companies (SMEs). Recognising that psychological ownership (PO) represents a crucial aspect of the implementation process, we address micro-foundational characteristics of the implementation process. PO and critical incident theory (CIT) provide a lens enabling this micro analysis. The empirical setting is the implementation of Hoshin Kanri, a strategic management system in eight small companies. From the analysis of the eight cases, we operationalise four dimensions that characterise how PO evolves in the implementation process: types of PO incidents, frequency of PO incidents, incidents indicating an increase or decrease in PO, and incidents addressing individual or collective PO. Looking at how PO is developed both among CEOs and managers in SMEs, we use the four dimensions to characterise the evolvement of PO within the focal organisations. In doing so, our article elaborates on PO as a driver and, if insufficiently developed, an impediment to effectively implementing management innovations.

Introduction

Management innovation, described as ‘the invention and implementation of a management practice, process, structure, or technique’ (Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol Citation2008:825), is recognised as an important source of competitive advantage (Hervas-Oliver, Ripoll-Sempere, and Moll Citation2016; Mol and Birkinshaw Citation2009; Walker, Chen, and Aravind Citation2015) and a prerequisite for effective technological innovation (Černe, Jaklič, and Škerlavaj Citation2015; Volberda, Van Den Bosch, and Heij (Citation2013); Mol and Birkinshaw Citation2006). Through diffusion beyond their origin, management innovations can impact entire economies (Harder Citation2011). Against this background, knowledge of how to implement management innovation successfully is critical. However, to date, most literature on management innovations has focussed on their antecedents and outcomes (e.g. Mol and Birkinshaw Citation2009; Nieves and Segarra-Ciprés Citation2015; Volberda, Van Den Bosch, and Heij Citation2013). There is only limited research on what characterise the process by which management innovations unfold (Amarakoon, Weerawardena, and Verreynne Citation2018; Lin, Su, and Higgins Citation2016). This lack of in-depth research on the implementation process (Khosravi, Newton, and Rezvani Citation2019; Rasmussen and Hall Citation2016; Keupp, Palmié, and Gassmann Citation2012) makes Volberda, Van Den Bosch, and Mihalache (Citation2014) argue for more micro-oriented studies of implementation processes, studies that must be attentive to the context in terms of both the organisation and the type of managerial involvement considered (Damanpour, Sanchez‐Henriquez, and Chiu Citation2018; Nieves and Segarra-Ciprés Citation2015; Volberda, Van Den Bosch, and Heij Citation2013). Roy, Robert, and Giuliani (Citation2018) contend that there are few attempts to study the implementation of management innovations. It comes therefore as no surprise that Mol and Birkinshaw (Citation2009, 1279) call for research to ‘focus on how new management practices diffuse inside firms’. This implies opening the black box of intrafirm processes and paying attention to the organisational and managerial context in which management innovations are introduced. In the present article, we introduce the lens of psychological ownership (PO) to investigate intrafirm processes during the implementation of management innovations. We argue that development of psychological ownership constitutes an important contextual factor for management innovations to be successfully introduced in firms.

The importance of considering organisational and managerial contexts when studying management innovations is linked to two specific characteristics of these innovations. First, management innovations are social constructions consisting of managerial ideas, practices and processes that can be moulded in numerous ways. They must therefore be repeatedly defined and linked to the organisational context in which they are implemented (Černe, Jaklič, and Škerlavaj Citation2013). Second, management plays a key role in creating legitimising management innovations. Managers must take an explicit role in the generation and adoption process to create organisational ownership (Amarakoon, Weerawardena, and Verreynne Citation2018). Thus, the rhetorical component when ‘selling’ management innovations is essential (Bartel and Garud Citation2009; McCabe Citation2002). It is also important for the legitimacy of the management innovation that organisational co-workers feel ownership of i (Vaccaro et al. Citation2012).

The literature on psychological ownership (PO) suggests that when managers feel ownership of an innovation in a psychological sense, this PO facilitates their acceptance of the innovation (Paré, Sicotte, and Jacques Citation2006). PO of ideas creates a personal attachment that makes people willing to defend those ideas against change and opposition (de Dreu and van Knippenburg Citation2005). Hence, the degree to which managers and other organisational stakeholders take PO of a management innovation plays an important role in how the management innovation evolves. The extant literature on management innovation acknowledges this at least indirectly, for instance, when discussing the role of change agents (Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol Citation2008), but usually without referring explicitly to the notion of PO. In the present article, we address this gap by using the PO literature as our main theoretical lens to investigate how psychological ownership evolves in the implementation of management innovations.

Empirically, our study focuses on how PO develops in a specific management innovation case: the Hoshin Kanri management system in manufacturing SMEs. By studying SMEs, our work balances the emphasis on large firms by extant research on management innovations. Large companies offer very different conditions in terms of absorptive capacity or managerial resources (Mol and Birkinshaw Citation2009; Peeters, Massini, and Lewin Citation2014) as opposed to their smaller counterparts. There is also existing research on management innovations covering SMEs explicitly (e.g. Yu et al. Citation2022; Hervas-Oliver, Ripoll-Sempere, and Moll Citation2016; Madrid‐Guijarro, García‐Pérez‐de‐Lema, and Van Auken Citation2013) or including them in samples among other firm sizes (e.g. Mol and Birkinshaw Citation2009; Nieves and Segarra-Ciprés Citation2015). This work is usually drawing on large sample studies. While it has its own merits, not least in testing causal relationships with statistical rigour, it cannot address micro-level details of implementation processes. Looking at the dynamics of PO with its increase as well as decrease during management innovation processes, the present study opens for a better understanding of such processes on a micro-level in SMEs that strive to become more effective and efficient by introducing new management practices (Tezel, Koskela, and Aziz Citation2018).

Our focus on a unique management innovation implemented in several companies simultaneously avoids bias related to differences between management innovations. The management idea (Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol Citation2008) in Hoshin Kanri (HK) is a structure for ongoing learning in strategic conversations within the company (Marksberry Citation2011). Hoshin Kanri can be classified as a business practice that addresses how work responsibilities and decision making are organised in the firm (OECD Citation2005). Applying Armbruster et al. (Citation2008) categorisation scheme, HK represents a procedural management innovation with an interorganizational focus. It is also a crucial management innovation, as it targets the core of a company’s management processes (Hamel Citation2006). This management innovation is new to the studied organisations relative to the dominating strategic planning system, but not to the state of the art (Hutzschenreuter and Kleindienst Citation2006; Wolf and Floyd Citation2013). There are few reports on the implementation of Hoshin Kanri in SMEs (cf. Giordani da Silveira et al. Citation2017; Melander et al. Citation2016; Tennant Citation2007).

This article aims to investigate how management innovations are implemented in the SME context. We apply the PO lens to identify, on the micro-level, changes over the course of an implementation process. We then link this development to the process characteristics in terms of how and to what extent management innovation is implemented. The research question guiding this study is hence:

What role does psychological ownership play during the implementation of management innovations?

By introducing the PO perspective to the management innovation literature, our article contributes with a better understanding of the micro-processes at play when management innovations are implemented. In particular, we highlight how psychological ownership is spread beyond a narrow circle of managers and what importance a broadened psychological ownership has for making the implementation successful.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: First, we discuss extant research on management innovation and its link to the PO literature. Thereafter, we present our methodological approach, empirical data and the analysis. Finally, we present our results based on the research question.

Theoretical framework

In this framework, we start by providing an overview of the extant literature on management innovation. The previous empirical research that we address, covers a variety of management innovations, such as TQM, lean, six sigma or the balanced scorecard. To keep our article focussed, we have refrained from discussing any specific management innovations apart from Hoshin Kanri in detail. We rather discuss central topics of the overall literature on management innovations, including their antecedents, their implementation, and the role of managers in management innovation processes. Thereafter, we introduce the PO literature as a lens for studying the process of management innovation.

Management innovation

Firms not only innovate by launching new products, services or technologies but also transform management by introducing novel practices. In doing so, management innovation adds to a firm’s innovative performance regarding technological change (Volberda, Van Den Bosch, and Heij Citation2013). There is a long tradition of research studying management innovations, including Chandler’s (Citation1962) and Williamson’s (Citation1975) work on the multidivisional form, Reger et al.'s (Citation1994) work on implementing TQM, Gosselin’s (Citation1997) research on activity-based costing, and Womack and associates’ books on lean production, pioneered by Toyota (Womack, Jones, and Roos Citation1990; Womack and Jones Citation1996). However, management innovation as a label denoting a specific field of research emerged only after the turn of the millennium.

In a seminal article, Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol (Citation2008, 825) define management innovation as ‘the invention and implementation of a management practice, process, structure, or technique’. While this definition focuses on management innovations new to the state of the art, also research on innovations new to the firm, i.e. the diffusion and adoption of existing management innovations has become a research topic (e.g. Nieves and Segarra-Ciprés Citation2015; Mol and Birkinshaw Citation2012). There is an obvious difference in the degree of novelty when comparing management innovations entirely new to the world to those new to a specific firm. The present article focuses on novelty to a firm, i.e. management innovations that have existed for some time, but not yet been introduced in a specific organisation. While such innovations may be widely spread in the environment of the focal firm, their implementation may still be a major problem hampering the firm’s competitiveness (Bloom and Van Reenen Citation2007, Citation2010).

In recent years, there has been a growing body of research on management innovations (Damanpour and Aravind Citation2012; Khosravi, Newton, and Rezvani Citation2019). Overall, the literature on management innovation has a limited connection to the literature on technological innovation (Heij et al. Citation2020). Damanpour (Citation2014) suggests that management innovations are more difficult to observe and that they have several distinct features: management innovations are pervasive in their impact on organisational structures and authority, the link between the innovation and the outcome is often unclear (Heij et al. Citation2020), and these innovations are difficult to implement because of their operational complexity.

The general innovation literature has devoted much attention to the decision to adopt an innovation (Klein and Sorra Citation1996; Wisdom et al. Citation2014). This literature emphasises the identification of an innovation opportunity and the yes/no decision to pursue it (Armbruster et al. Citation2008; Damanpour Citation2014) rather than its subsequent implementation. Consequently, the interorganizational episode is in focus, while intraorganizational processes remain a black box, and we learn little about adaptation and variation between organisations (Ansari, Fiss, and Zajac Citation2010). In the management innovation literature, this is mirrored in research on the antecedents of management innovation. Volberda, Van Den Bosch, and Heij (Citation2013) distinguish between interorganizational, intraorganizational and managerial antecedents. Often, the interplay of various contextual factors determines whether an organisation adopts management innovations (Ganter and Hecker Citation2014). Bloom and Van Reenen (Citation2007) found that a competitive environment leads to more management innovation, while family management, particularly primogeniture succession, makes firms conservative and impedes management innovation. In a 2010 publication, the same authors add a low degree of labour market regulations, multinational exposure and human capital as antecedents of management innovation. Diagnostic capability (Harder Citation2011) and search activities (Mol and Birkinshaw Citation2009) are important to identify suitable innovation options. The internal characteristics of firms, such as diverse top management teams (TMTs), rich internal communication flows and CEO novelty, support the introduction of management innovations (Yu et al. Citation2022; Harder Citation2011). Karatepe, Aboramadan, and Dahleez (Citation2020) found that servant leadership promotes management innovation by fostering a climate for creativity. The importance of managerial capabilities for identifying suitable management innovations may be a disadvantage for SMEs, which typically lack large and diverse management teams (Harder Citation2011) and face general resource constraints, not least constraints in human capital (Mol and Birkinshaw Citation2009). Bloom and Van Reenen (Citation2010) found that young firms are less likely to introduce management innovations during later stages of their growth if the founder is still the CEO, probably due to founders having entrepreneurial skills rather than those required for managing a maturing firm. External change agents such as industry associations and consultants sometimes serve as a substitute for limited internal resources when SMEs introduce management innovations (Nieves and Segarra-Ciprés Citation2015). Their involvement often involves standardised processes and tends to make management innovations similar across organisations (Wright, Sturdy, and Wylie Citation2012).

Some management innovation literature goes beyond the yes/no question of adoption. Damanpour (Citation2014) subdivides the process of management innovation into the phases of awareness, selection, adaptation, implementation, and routinisation. Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol (Citation2008) outline a process model for management innovations new to the state of the art, comprising the stages of motivation, invention, implementation, and theorising and labelling. By definition, such a model places much emphasis on the conception, testing and shaping of an entirely new practice, which is different from the process of implementing an existing management innovation that is new to the firm. Nevertheless, Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol's (Citation2008) model highlights the importance of management innovation’s legitimacy in organisations, which is likely to be critical even in implementing an existing innovation (Volberda, Van Den Bosch, and Mihalache Citation2014).

Extant work emphasises the importance of decisions and support by management to succeed in the implementation of a management innovation (Rasmussen and Hall Citation2016). Wu (Citation2010) emphasises the importance of understanding resistance to management innovation, such as misfit between the ideas underlying management innovation and existing mental schemes in organisations (Reger et al. Citation1994). Implementation is affected by the innovation’s fit with the organisation in terms of technology and technological innovations, culture and the political interests of stakeholders (Ansari, Fiss, and Zajac Citation2010; Mawadia, Eggrickx, and Chapellier Citation2018). Robert et al. (Citation2019) identify different factors inhibiting management innovations, including the fear of losing influence, lack of confidence in the project, lack of skills and lack of management support. The importance of top management support seems especially outspoken in the SME context. (Negrao, Filho, and MarodinCitation2017; Rohlfer, Hassi, and Jebsen Citation2022; Yu et al. Citation2022).

Depending on the existence of inhibiting factors, particularly the lack of fit, innovation will require adaptation to be legitimate (Ansari, Fiss, and Zajac Citation2010). As we know from research on management fashions, new ideas are more likely to be successfully implemented, if they leave room for interpretive viability, i.e. enough ambiguity to easily fit them to a specific context (Benders and van Veen Citation2001). Klein and Sorra (Citation1996) argue that innovation is not implemented unless organisational co-workers have become skilful, consistent and committed in its use.

Change agents, both external, such as consultants and internal, often top managers (Peeters, Massini, and Lewin Citation2014), are supposed to play a key role in implementing management innovations (Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol Citation2008), notably in creating external and internal ownership for them (Volberda, Van Den Bosch, and Mihalache Citation2014). The building of organisational ownership appeals to co-workers’ self-interest, consistency with organisational values and the promise of solving organisational problems (Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol Citation2008). As management innovation is concerned with changing the organisation’s social system (Heij et al. Citation2020), effective implementation is more likely if top management obtains support from middle managers and the organisation has experience in carrying out change projects (Harder Citation2011). This resonates with Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol (Citation2008) notion of change agents legitimising management innovations among organisational stakeholders and was confirmed in Frynas, Mol, and Mellahi (Citation2018) application of the Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol (Citation2008) model. Generally, top managers play a more central active role in management innovation than in product innovation, which is more a task for engineers and product experts (Nieves and Segarra-Ciprés Citation2015). This might imply that gaining support from middle managers is a harder task in management innovation processes (Yu et al. Citation2022). Management innovations are introduced more quickly and effectively where influential champions drive the implementation process forward (Daniel, Myers, and Dixon Citation2012; Kunz and Linder Citation2015; Yoho et al. Citation2018) and different levels of management cooperate (Heyden, Sidhu, and Volberda Citation2018). Peeters, Massini, and Lewin (Citation2014) find that managerial attention by corporate-level executives legitimises the management innovation process and makes it more efficient. They also contend that change agents at the level of middle managers might not have the authority to legitimise management innovation internally. Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol (Citation2008) see a key role of internal change agents in theorising management innovation in relation to the organisational context, while external change agents build legitimacy internally in their role as experts and towards external audiences, which is particularly important for innovations new to the state of the art. In the literature, legitimacy is typically depicted as developing in a linear manner, i.e. the possibility of legitimacy loss is not problematised.

Integrating an innovation into its new technological, cultural and political context requires adaptational and interpretive effort (Ansari, Fiss, and Zajac Citation2010). Guzman and Espejo (Citation2019) and Klein and Sorra (Citation1996) argue that successful implementation needs a climate favourable to change and innovation, including open debate, as well as a fit between the specific innovation and the organisation’s values.

There is agreement that management innovation requires support from organisational co-workers and, notably, management to be effective (Birkinshaw and Mol Citation2006; Damanpour and Aravind Citation2012; Harder Citation2011; Volberda, Van Den Bosch, and Heij Citation2013). However, due to the lack of process studies in the field, we have limited knowledge beyond the correlation of certain antecedents with management innovation. For instance, we know that managerial commitment supports management innovation (Scherrer-Rathje, Boyle, and Deflorin Citation2009) but do not know how managers become committed to an innovation initiative and how this commitment develops over time. Likewise, while we know of the importance of specific leadership styles in such initiatives (Vaccaro et al. Citation2012), the question remains as to how leadership concretely influences the behaviour of organisational co-workers to be more (or less) supportive of management innovation.

Psychological ownership (PO)

We argue that PO is an important theoretical lens to understand possessive feelings that attach individuals to objects. It has roots in the psychology and organisation sociology literatures dating back as far as the 19th century (cf. Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2001 and 2003 for good reviews of the concept’s history and its relationship to other concepts in psychology) literature PO implies that material or nonmaterial objects, such as ideas (Brown and Robinson Citation2011), become part of a person’s extended self (Baer and Brown Citation2012; de Dreu and van Knippenburg Citation2005), and the person considers these objects his or her own (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2003). This lens can help us understand how managers and other organisational members increase their commitment to management innovations and how managers succeed in implementing them. The PO literature suggests that the successful adaptation of innovative ideas is supported by managers’ feeling that the ideas are their own, i.e. their experience of PO (Paré, Sicotte, and Jacques Citation2006).

Often, PO has been considered an inertial force, as it makes organisational co-workers adhere to ideas they have been used to (Brown, Lawrence, and Robinson Citation2005). However, PO can have both positive and negative effects on change acceptance. Typically, managers reject changes that are subtractive, i.e. take something away from ideas they already own. However, when ideas are perceived as additive, i.e. building on and extending managers’ existing ideas, they are likely to be supported (Baer and Brown Citation2012). Paré, Sicotte, and Jacques (Citation2006) report that PO has a positive impact on both the perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of an innovative system. Hence, managers who feel PO of an innovative idea are likely to develop attitudes that facilitate its adoption and implementation. Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks (Citation2001) view control, intimate knowledge and investment of oneself in the target as the primary paths for developing PO. Thus, a study of how PO evolves should pay attention to how different implementation actions influence the relationship to management innovation (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2001). It is also likely that managers who experience immediate additive effects also more rapidly develop PO.

PO has traditionally been conceptualised as comprising three dimensions: belonging, self-efficacy and self-identity (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2001). Thus, having PO of something creates a feeling of belonging and helps define a person’s identity. The self-efficacy component implies that the perception of being in control comes with an ability and a responsibility to achieve success with the objects of ownership. Avey et al. (Citation2009) add two further dimensions to PO: accountability and territoriality. While the former means that PO comes with the perceived right to hold others accountable and be held accountable, the latter points to a potentially negative side of PO. Those who feel PO may be inclined to keep the object of ownership for themselves and exclude others from it.

The literature suggests that such perceptions of PO are not limited to individuals but can also apply to collectives, such as working groups or management teams (Man and Farquharson Citation2015; Pierce and Jussila Citation2010, Citation2011). Collective PO emerges at the individual level, where individual organisational co-workers need to develop a sense of our-ness before this perception becomes collectively shared (Pierce and Jussila Citation2011). Such development of collective PO is promoted by social interaction, especially in early project phases (Man and Farquharson Citation2015). Consequently, this evolution of PO from the individual to the collective becomes crucial if the focal object is the adoption of a management innovation (cf. Kossek Citation1989).

How, then, can we empirically observe that co-workers feel PO of a management innovation? Indicators of PO include taking responsibility for the innovation (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2001, Citation2003) and going beyond required work roles to support it (Vandewalle, Van Dyne, and KostovaCitation1995). Individuals experiencing PO are likely to care for and protect the object of ownership even to the extent of making personal sacrifices (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2001). They may explicitly refer to the object as ‘mine’ (Van Dyne and Pierce Citation2004) or ‘ours’ (Pierce and Jussila Citation2011), thus expressing their closeness to it (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2003). Olckers (Citation2013) operationalises the dimensions of PO and measures them with a questionnaire. The questions address the extent to which co-workers identify with the organisation (self-identity), feel responsible for their actions’ effects on the organisation (responsibility, similar to accountability), feel in control of their actions (autonomy, similar to self-efficacy) and defend their work environment from others (territoriality). As with all questionnaires, Olckers' (Citation2013) instrument relies on self-reported perceptions rather than on actual behaviour. Questionnaires also tend to fail to capture the processual nature of PO (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2003); therefore, it is of no surprise that the time dimension has been an understudied area of research (Peck and Luangrath Citation2018). A probable effect of this is that the variation in PO over time also represents an understudied area (Baxter and Aurisicchio Citation2018). To date, empirical research on PO has focussed on the individual level and neglected the collective dimension (Dawkins et al. Citation2017; Pierce and Jussila Citation2011). Data collection methods other than questionnaires may be helpful in overcoming these shortcomings.

In summary, the management innovation literature paints a diverse picture of factors that can impact the process in which management innovations are implemented (Cândido and Santos Citation2011; Okumus Citation2003; Volberda, Van Den Bosch, and Heij Citation2013). There is a strong focus on identifying antecedents preceding management innovations and studying them quantitatively (Harder Citation2011; Mol and Birkinshaw Citation2009), whereas the process as such often remains a black box. As a result, the understanding of how PO evolves over time is limited. Therefore, process studies of management innovations will contribute to the field by providing insights into implementation processes and PO. To the best of our knowledge, management innovation has not yet been studied from the PO perspective.

The Hoshin Kanri management system

This article reports on a research project financed by the Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems (VINNOVA) and participating companies between 2013 and 2016.Footnote1 The project aimed to adapt the Hoshin Kanri (HK) (management compass) to manufacturing SMEs.

HK is a management system developed in the large company context, and to our knowledge, there exist only a few academic reports that focus on HK adoption in a small firm setting (Tennant and Roberts Citation2001; Melander et al. Citation2016; Löfving et al. Citation2021). HK can be described as ongoing and focussed learning in strategic conversations (Marksberry Citation2011), a process that increases co-workers’ control over their work and results in higher productivity (Babisch Citation2005; Kondo Citation1998). These formalised conversations, based on a distinct scientifically based methodology (PDCA), differentiate HK from other management systems (e.g. Feurer, Chaharbaghi, and Wargin Citation1995). Furthermore, the consistent and process-oriented nature of HK stimulates managers to develop clear ambitions and an engaging coaching-oriented leadership style (van Assen Citation2018).

HK should be implemented at the top management level and then deployed down to operations (cf. Tennant and Roberts Citation2001). Hence, top management PO is crucial for organisation-wide implementation and co-worker inclusion (cf. Lee and Dale Citation1999). When PO has been achieved, the annual process starts with owners/top managers defining the current state of the business, the vision, and the one- to three-year organisational objectives (cf. Akao Citation1991; Babisch Citation2005; Hutchins Citation2008). This ability to consistently focus on a few critical breakthroughs or challenges, to create a sense of urgency, is vital for HK’s success (Chiarini Citation2016; Wood and Munshi Citation1991). What follows is a structured deployment/strategic catch-balling routine and review processes that form an iterative decision-making process funnelling the broad vision into more well-defined, short-term objectives, leading to a consensus on the strategic knowledge needed. This review process has two purposes: to ensure that the execution of set objectives is on target and to aggregate learning on how to develop the strategic management system itself (Cowley and Domb Citation1997).

HK can be described as one pillar in the broad total quality management (TQM) and lean manufacturing movement (Akao Citation1991, Potter Citation2022). Hence, parallels between HK and lean are obvious. Based on an extensive literature review, Leite, Radnor, and Bateman (Citation2022) propose that consistent, engaged and motivated leadership is essential for a successful implementation of lean management, and Tortorella et al. (Citation2021) conclude that a development-oriented culture and coaching leadership style are highly related to lean management implementation. These findings are in line with the HK characteristics discussed above.

Overall, HK can be classified as a procedural and interorganizational innovation addressing routines and processes within the focal firm. It represents a crucial management innovation, as it targets the core of a company’s management processes (Hamel Citation2006). The difference between HK and most other examples, as discussed by Armbruster et al. (Citation2008), Damanpour (Citation2014) and OECD (Citation2005), is a strong emphasis on the role of management preceding the participation of the organisation as a whole. The emphasis on management in HK, in turn, makes managers role in the development of psychological ownership easy to observe empirically, making HK highly suitable for a study that focuses on the psychological ownership aspect of implementing management innovations.

Finally, it must be noted that even if HK follows some distinct principles, as reported above, it is not a rigidly structured concept (Jolayemi Citation2008; Nicholas Citation2016). This supports the ambition in this study to encourage broad variation in the HK implementation process. To further support this variation, a supportive standardisation approach was applied by the trainers (Wright, Sturdy, and Wylie Citation2012).

Method

The project included 14 Swedish manufacturing SMEs (see ), three researchers and two trainers, allowing robust, multiple-case theory building (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007; Hoon Citation2013). The team included competencies in strategic and innovation management, development work, lean management and possessed both practical knowledge of Hoshin Kanri and essential contextual knowledge (Hu et al. Citation2016).

Table 1. Companies participating in the study and their characteristics.

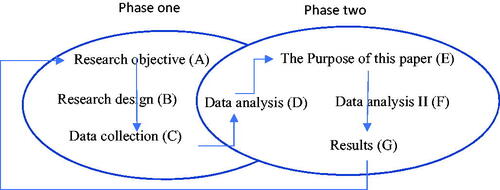

The present research project follows the action research tradition, as trainers and researchers participated in the implementation process (Bradbury Citation2015). Following Coghlan and Shani (Citation2014) we have taken several actions to ensure quality in such a project. Relevance of the project was secured as the challenge addressed was approved by a wide number of companies that all were willing to invest considerable time. Moreover, we contacted several industry experts and discussed the need for this type of research in SMEs. Rigour was addressed by the application of a designed research protocol (McCutcheon and Meredith Citation1993). Below, we visually describe the protocol, and in the following text, we have marked the different stages of the research process with the letters A to F (). The link between the results and the initial research objective (G-A) is addressed in the concluding part of the paper. In the research protocol we assign considerable time and effort to stage D to secure a rigours interpretive process in several cycles (see below). A process that continued in the following interpretive analysis. An important aspect in this analysis was how to combine a standardised outline of the project to provide for comparisons between companies with openings for variance, to provide for various interpretations. Following Wright, Sturdy, and Wylie (Citation2012) we adopted a semi-structed standardisation that contributes to variance. The HK concept in-itself and the imposed structure of quasi-experimental workshops enforced a certain standardisation in the project. But this was balanced by the fact that even if HK follows some distinct principles, as reported above, it is not a rigidly structured concept (Jolayemi Citation2008; Nicholas Citation2016). Moreover, the individual differences between the participating companies that surfaced over time, combined with the varying background among the five involved trainers and researchers, ensured a certain variation within implementation processes. Companies and research participants have provided informed consent to the research. No formal ethics approval for this research was required by Swedish law.

The study of how to implement the Hoshin Kanri management system (A) was organised as a set of quasi-experimental workshops (cf. Grant and Wall Citation2009) with company management (B). In 94% of the workshops, the CEO attended, and in 81% of the workshops, at least two more managers participated. In total, 130 workshops (446 h) were arranged within a period of 36 months. The level of engagement differed among the companies. Six companies abandoned the project prematurely because of structural changes (changes in ownership, CEO successions or drastic changes in market conditions). As a result, this analysis focuses on the eight companies that participated through the end of the project in August 2016, covering 105 workshops over 366 h (C).

The 12–18 workshops attended by each of the eight companies were organised according to five themes. (Get to Know; Today and Tomorrow; Analysing and Choosing Challenge; Follow up on Challenge(s) and Project Conclusion Meeting). The idea being that company management identified a strategic challenge or critical breakthrough on which the principles of Hoshin Kanri was applied. First, when the specific challenge was successfully approached and those involved were familiarised with HK, the entire HK management system was implemented (Melander et al. Citation2021).

The five implementation themes represented a needed systematic design (Gersing, Oehmen, and Rebentisch Citation2014), allowing design evaluation. The experimental aspect was covered by the two implementation steps where the challenge in the first step was unique for each company. But also, by company deviations from the systematic design of the process both in terms of emphasises on the different themes (in some companies it took several WS to cover the first three themes) and sequentiality (in some companies it was learnt in the follow-up (theme four) that the challenge chosen in theme three was unsuitable, and the process was then reversed to choose a new challenge).

The analysed data consist of 366 h of workshop time and numerous phone calls and emails. First, the team (one researcher and one trainer in each workshop) took extensive fieldnotes at all 105 workshops (in total, 405 transcribed pages). After workshops, the team directly conducted a 45–60-min debriefing session. After this, all working material was shared by all researchers, and the results were jointly analysed at weekly project meetings (in total, 77 online meetings, 1–2 h long). In these meetings, attended by the researchers, general learning-oriented questions guided us. What went according to plan? Why? What did not go according to plan? Why? Furthermore, in longer meetings organised once every semester, the research team categorised and analysed the weekly learning to identify general patterns across workshops and participating companies (D).

In this first analysis, focussing on the Hoshin Kanri implementation process, we soon realised that the PO concept was useful when operationalising our joint understandings of the unique company processes. Consequently, the introduction of the PO literature as a theoretical lens represented a move from a descriptive analysis to an interpretative analysis (Abdallah, Lusiani, and Langley Citation2019).

The interpretative analysis

This phase of the research began with an extensive literature review of PO literature. The outcome of this review was the purpose of this paper (E) and the overview of PO as presented in the theoretical framework. Inspired by innovation process research (Van de Ven and Poole Citation1990; Ring and Van de Ven Citation1994) we identified critical incident theory (CIT) as a prospective method for analysing PO changes. CIT is an established research method in the social sciences embracing an inductive perspective and acknowledged for its flexibility in application (Butterfield et al. Citation2005). Flanagan (Citation1954, 327) defined an incident as an observable human activity that permits inferences and predictions. Critical incidents are represented by significant occurrences such as events, incidents, processes or issues (Man and Farquharson Citation2015). CIT was originally recommended for participatory observations, as practised in this study (Flanagan Citation1954), but is today often combined with self-reporting methods (Gremler Citation2004).

Inspired by Man and Farquharson (Citation2015), Gray, Knight, and Baer (Citation2020) and Tourish (Citation2020), who all used incidents to understand PO evolution in a qualitative approach, we returned to our field notes (405 pages), and in the second analysis, we focussed on how PO incidents could contribute to our understanding of implementing management innovations. (F). This analysis resulted in 164 incidents (see and , a reasonable number for this type of analysis (FitzGerald et al. Citation2008)). Two researchers independently studied the field notes and coded instances (cf., Man and Farquharson Citation2015). After coding the notes from two case companies, the results were compared, and discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached. When the results of the analyses differed, which occurred in six out of the 32 incidents that were coded in the first two case companies, the two authors involved a third member of the research team and jointly reached a consensus.

Table 2. CEO's psychological ownership – increase or loss of PO.

Table 3. Organisational psychological ownership – increase or loss of PO in the collective dimension.

includes questions that address an increase in engagement, promotion, mastery and integration (T2:1,3,5,7). Below, we include one question to illustrate the logic applied. (Question T2:1) Does the CEO engage in the implementation work? Assumption: If the CEO devotes time to and shows engagement in and between the organised workshops, this indicates that he or she considers the innovation important and prioritises it. This is a sign of increased PO of the innovation. Frequent incidents identified in the data are increased relevance, increased engagement, increased responsibility, increased time devoted to the innovation and attempts to organise implementation work.

As noted above, relying on data from participatory observations, we were also able to code incidents that indicated whether the incident was of rhetorical or technical nature. Following Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol (Citation2008) and Zbaracki (Citation1998) we here separated the incidents that concerned statements that were related to HK and incidents that concerned analytical tools applied in the implementation process. Among the later daily management, A3 reporting, PDCA and communication tools were the most prominent.

Further, we analysed the frequency of incidents in each company and incidents that indicated an increase or loss of PO (Bott and Tourish Citation2016). In below, the questions that addressed a loss of PO are represented by questions 2:2,4,6 and 8. Below, we include the first of these four questions as an example. (Question T2:2) Does the CEO disengage from the implementation work? Our assumption: If the CEO limits the time spent in and shows disengagement during and between the organised workshops, this indicates that he or she considers the innovation less important and gives it less priority. Hence, this signals that they CEOs have experienced a loss of PO of innovation. Frequent incidents identified in the data are long intervals between workshops, high workload frequently used as an excuse, unmotivated cancellations of workshops and low activity during workshops. The coded incidents are accompanied by a note indicating the workshop in which they appeared, which allowed us to address incident occurrence.

Following Heyden, Sidhu, and Volberda (Citation2018) and Khosravi, Newton, and Rezvani (Citation2019), we finally addressed how PO evolved from the individual to the collective. Here, the individual was represented by the CEO), and the collective level was represented by the present or prospective top management team. The reason for this decision is that the management innovation literature emphasises top management’s crucial role in the adoption process (Vaccaro et al. Citation2012; Yu et al. Citation2022). Consequently, incidents addressing the CEO’s PO of management innovation are critical for our understanding of how implementation evolves into the necessary collective PO (Guzman and Espejo Citation2019),

As discussed above, Pierce and Jussila (Citation2010) introduced the collective PO construct in PO research. We view our emphasis on incidents that signal collective PO in the adoption process as a first stage in the transformation from individual to organisational PO. Based on Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks (Citation2001) and Avey et al. (Citation2009), we inductively developed questions that addressed the collective dimension when we were coding at the individual level. This allowed us to go back to focus on the collective level in a second coding process. In below, we present the results of this coding as well as the six questions addressing increased or loss of collective PO (T3:1–6). These incidents range from the CEOs’ ambition to include or exclude co-workers in the adoption process, as well as co-workers’ activity in the implementation process. We do not include the actual reporting of co-workers’ participation in workshops and organisational activities between workshops in our analysis. Even if these data supported the conclusions reached in the coding process. Additionally, here, all coded incidents are accompanied by a note indicating the workshop in which they appeared, which also allowed us to address incident occurrence.

Finally, given the importance of knowing to what extent management innovation is used (Armbruster et al. Citation2008), the research team evaluated the implementation status in terms of psychological ownership of Hoshin Kanri. Given that this is a difficult task when studying the early phase of innovation adoption (Damanpour and Aravind Citation2012), this was done on two occasions. The first evaluation took place at the end of the last workshop in the implementation process. Here, we opened for a general evaluative discussion with the participants on both the historic process and on their plans for the future regarding Hoshin Kanri, if any. At this time, it was obvious that two companies (Villa, DandP) had taken more of ownership than the remaining companies. The second evaluative occasion was approximately six months after the project was finished. Here, we contacted the CEOs on phone and interviewed them on the progress since the project was completed. On both occasions, we used Armbruster et al.'s (Citation2008) questions on complexity, life cycle, extent of the use of and quality to guide our interviews. In the second interview, structural changes, such as the owner/manager divesting the company (LG) and that the CEO had left the company (House), obviously impacted implementation efforts in several cases. After the second evaluation, we categorised the participating companies as either High (2), Neutral (2) or Low (4) on psychological ownership of Hoshin Kanri.

Critical incidents and psychological ownership

Our application of critical incident theory (CIT) resulted in 164 incidents that signalled a change in PO at the individual (CEO) or collective level. We organised these incidents according to four dimensions that together characterise the studied implementation processes.

Rhetorical vs. technical PO incidents

Frequent vs. infrequent PO incidents

Increasing vs. decreasing PO incidents

Individual vs. collective PO incidents

Rhetorical vs. technical PO incidents

This dimension denotes whether PO is primarily reflected in a verbal statement (rhetorical) or concerns work with an analytical tool (technical).

Five out of the first six incidents in WSs 1 and 2 are rhetorical in nature in our cases. Statements such as ‘HK relevant for us’ and expressions of commitment, such as when the CEO at Flex at the second workshop concludes a presentation from the research team with the statement that ‘Hoshin Kanri is relevant for us’, signal curiosity in the sense that the CEO is open to learning and generally positive to the management innovation. However, there is no outspoken commitment embedded in these statements, as there is no clear link to a future effort (Salancik Citation1977). The commitment is also limited in most statements, as they are made only in the presence of externals, in this case the research team. On several occasions further into the process, we also identify rhetorical statements made by middle managers (Villa, House, DandP, LG). In most cases, these are statements of appreciation made by a single manager to the research team in a small setting. To exemplify one manager in Villa talking to a researcher at a coffee break, he stated with gratitude that he never had been invited to a strategy day before this HK workshop he now attended.

There are also incidents of a technical type. This distinction is in line with Zbaracki's (Citation1998) separation of rhetorical and technical elements in the implementation process, where technical elements refer to practical work with relevant analytical tools. As stated above, five out of the six first incidents were rhetorical, meaning that the technical type generally takes longer to appear in an implementation process. In the Garo case, the CEO adopted and modified an analytical tool early in the process, the A3. This indicates that he voluntarily, between workshops, has spent time adopting the management innovation. Later this also happened in House and Flex. Even if the technical incidents only represented a minor part of the total number (11.5%) it seems as they were important for the implementation process, as the majority addressed collective PO.

Although technical PO incidents show collective commitment in a rather substantial way, the rhetorical type is more than just cheap talk. In the cases of Flex, Villa and DandP, we detect incidents that address this marketing aspect, whereas the CEOs early in the processes express their ambition to involve co-workers in the implementation process. The Garo case represents an interesting case here. In WS1, the CEO early states that HK is relevant for them; hence, this incident represents a rhetorical statement made in the presence of the research team and with low commitment. Later, in the same workshop, the CEO invites the research team to the upcoming TMT (top management team) meeting. Here, the rhetorical statement he makes is linked to a clear commitment, and thus, the signalling value in this rhetorical incident is high.

However, an even more committing rhetorical incident is when the CEO in Villa relabels the management innovation internally, an incident of high symbolic value (Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol Citation2008). This resonates with McCabe’s (Citation2002) notion of rhetoric being central to management innovation processes, especially when the management innovation is to be marketed within the organization (Tsoukas Citation2009).

We therefore propose:

P1: The process of establishing PO of a management innovation is characterized by rhetorical incidents in the initial phase of the implementation process.

P2: The role of technical elements is more prominent than rhetorical elements when establishing a collective PO of a management innovation in the implementation process.

Frequent vs. infrequent PO incidents

The time dimension in management innovations has been recognized (Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol Citation2008) but is still an understudied topic both in PO studies (Peck and Luangrath Citation2018) and in the management innovation literature (Damanpour Citation2014). Robert et al. (Citation2019), for instance, claim that there is an optimal implementation time, and processes beyond this time erode motivation.

In this study, the research team ended their engagement in the implementation processes at a specific point in time. Then, the status of the eight processes was evaluated, with a follow-up after six months.

DandP and Villa stood out as developed a high PO of the management innovation within the studied period, and they continued the implementation after the study ended. In these cases, we can identify the highest level of incidents in total (30 each), the highest number of positive incidents (30 and 26) and the highest number of collective incidents (9 and 11). In terms of frequency, the average was 2,5 incidents per workshop.

For the six remaining companies, the relationship between PO and the final evaluation (taking place at the end and after six months) was more unclear. A slight difference was detectable between the two companies that were evaluated as neutral (House and KG) with a frequency of 0.75–1 incidents of increasing PO per workshop and the four that were evaluated as Low PO (KG, Fell, Flex and Garo) with a frequency of incidents signalling an increase in PO on 0.5–0.7. Hence, the estimated level of PO when implementing HK in these six companies was not directly related to the level of incidents or frequency of incidents per workshop. Several factors contribute to this unclear result, where some factors relate to the implementation characteristics, such as the type of incidents discussed above. Other factors relate to structural changes that took place in the six months after the study ended. In the LG case, for instance, HK adoption was disrupted by the owner/manager divesting the company. At House, the CEO was replaced soon after the project ended. Our results suggest that a high number and frequency of positive incidents both at the individual CEO level and the collective level provide the implementation process with momentum that helps both achieve and maintain PO, while a low number of incidents erodes motivation and thus PO. Given these results and the recognized importance of the time dimension in the literature, we propose the following:

P3: A high number and frequency of positive incidents increases PO and thus a successful implementation of a management innovation.

P4: A high number and frequency of collective incidents increases PO and thus a successful implementation of a management innovation.

Increasing vs. decreasing PO incidents

We know that implementation processes sometimes come to a halt and even degenerate or reshape, referred to as iterations by Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol (Citation2008). However, when attended to in the management innovation literature, this complexity is often simplified to identify implementation enablers or hurdles (cf. Douglas, Overstreet, and Hazen Citation2016; Wu Citation2010). Our results indicate that processes can develop, they can come to a halt, and they can also revert (Langley et al. Citation2013). Therefore, the CEO can well be driving a decrease in PO and not only an increase. When a CEO persistently signals an increasing PO, as in the DandP case, this is obviously to be interpreted as beneficial for the implementation of a management innovation (Scherrer-Rathje, Boyle, and Deflorin Citation2009; Daniel, Myers, and Dixon Citation2012), but the picture is more complexed when increasing and decreasing incidents are mixed. Such as in the Flex case.

Out of 164 incidents 44 represented a decrease in PO. There was a clear pattern distinguishing successful implementation cases from less successful implementation cases. At Villa and DandP, 56 out of 60 incidents were positive, and only four indicated a decrease in PO. Three out of these four were related to delays due to workload in Villa. At the remaining six case companies, the frequency of decreasing incidents was higher and more evenly distributed, with 40 incidents representing a decrease out of a total of 104. Analysing the incidents indicating a decrease in PO, we identify three categories. The first relates to time management, such as the postponement of workshops, key participants not attending the workshop or ‘homework’ not completed. These are all interpreted as a decrease in PO, as the company representatives down-prioritized HK adoption. Surprisingly, most of the decreasing incidents in this category were related to the CEO in the case companies. The second category is incidents that signal difficulties diffusing HK to a wider group in the company. A category that will be further discussed below. The third category of incidents that represent a decrease in PO is related to failed experiments. An activity that was implemented, such as the practice of daily management, represented an incident signalling an increase in PO. However, if the implementation failed, this failure was at a later stage, signalling a decrease in PO. Setbacks in Villa, KG and Garo are included in this category.

We therefore propose:

P5: Incidents consistently signalling increasing PO leads to high organizational PO.

P6: Incidents providing shifting signals of both increasing and decreasing PO leads to low organizational PO.

P7: Incidents consistently signalling decreasing PO leads to low organizational PO.

Individual vs. collective PO incidents

The innovation literature, albeit focusing on adoption rather than implementation (Wisdom et al. Citation2014), has argued that an innovation is not implemented unless co-workers have become committed to its use (Klein and Sorra Citation1996). Such commitment is obviously of particular importance when we study an innovation that only functions if many co-workers are included (Armbruster et al. Citation2008). The common picture is that the CEO relentlessly strives for this implementation, but the process is (sometimes) resisted by other stakeholders. From the studied case companies, we believe that this picture should be qualified.

An important question in this context is thus how PO evolves from an individual to a collective phenomenon. It is apparent that in our two most successful cases, DandP and Villa, the CEO promoted the passage from the individual to the collective early. As shown by incidents reported in Tables two and three, they addressed this issue in the first two workshops. At Villa, the diffusion of the management innovation to the collective level became an integrated part of the first workshops as the CEO at once started to plan for a strategy meeting in the workshops. At DandP, it took longer, but here, a top management team was formed early, and daily management in the entire organization was introduced as a part of the implementation process. It is hence no surprise that the number of (positive) collective incidents was higher in these two companies than in the others.

Among the six cases where collective incidents were unusual or came late, we could detect several causes of slow adoption. One was the active resistance of important stakeholders in the Garo case, a type of hindrance that is often referred to in the management innovation literature (cf. Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol Citation2008). However, we also identified LG, a case where the top management team initially was very positive, but the CEO was more reluctant to increase transparency, and KG, where workshop participants from the family were positive to the management innovation but refrained from involving non-family co-workers in the implementation process. A third example is Flex, where the diffusion issue entered the agenda late in the process. All these cases signal the need to attend to sensitivity among top managers when and how to include more co-workers in the implementation process. We conclude this reasoning by proposing:

P8: Incidents signalling CEO openness to include co-workers early in the implementation process increase PO, and thus a successful implementation of a management innovation.

Discussion

Management innovations are difficult to study, as they are less codifiable than technological innovations and hence difficult to copy (Robert et al. Citation2019). Therefore, studies of management innovation need to emphasise the process in which innovations are interpreted, deconstructed and reconstructed in specific company contexts (Amarakoon, Weerawardena, and Verreynne Citation2018; Rasmussen and Hall Citation2016). This implementation process is the focus of the present study.

We have introduced and elaborated on the PO perspective (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2001). A perspective that adds to our understanding of how organisational legitimacy is constructed during the implementation of management innovations (Birkinshaw, Hamel, and Mol Citation2008)

Our study resonates with extant research claiming that managerial commitment is essential for effective management innovation (Scherrer-Rathje, Boyle, and Deflorin Citation2009). Such commitment is mirrored in managers signalling ownership of the management innovation through rhetorical and technical incidents in the implementation process. These two types own different qualities. The rhetorical statement may appear vague at first sight as it is not connected to direct action, but symbolically it represents a powerful signal that top managers’ PO of the management innovation will ensure their fidelity to the idea of the management innovation and sell it within the organisation (Dutton et al. Citation2001; McCabe Citation2002). The latter is especially true if the statement is made in the presence of important stakeholders and includes clear promises on future activities. The technical type, on the other hand, represents an activity that embeds a signal. For instance, the postponement of a workshop meeting without clear reason signals lower prioritisation. In our study, we propose that both rhetorical and technical incidents appear in the implementation process but that the rhetorical type, then often linked to the CEO, plays a more prominent role in the first phase of the implementation process.

However, this does not mean that the collective dimension does not matter. The extant literature suggests that management innovations, when compared to technical innovations, require wider adoption within the focal organisation to be successfully implemented (cf. Heyden, Sidhu, and Volberda Citation2018). This aspect is reflected in the separation of individual (CEO) and collective incidents, where the latter indicate a collective ownership of the innovation. In addition to the more obvious proposition that a high level of collective incidents increases PO indicates successful adoption, we also find that the timing and early planning of how and why organisational members were included in the process is important. Moreover, in the two successful cases, it was apparent that the CEO had a clear idea of the need to diffuse PO in the organisation from the very beginning, which resulted in early incidents indicating an increased collective PO.

This resonates with the literature on open strategy, where Hautz, Seidl, and Whittington (Citation2017) identify commitment as one out of five dilemmas. They argue that opening up the process contributes to more organisational commitment. However, if top management opens up the process, they also need to manage the expectations that follow. Hence, by opening up, managers need to recognise others’ viewpoints, and thus managers are no longer in absolute control. This reasoning helps to understand why some of the CEOs in our case companies struggled with the opening up of the management innovation implementation process. On the one hand, they understood the need to be inclusive, but on the other hand, they hesitated to refrain from absolute control. This struggle is reflected in the mix of increasing and decreasing PO incidents that appeared in some of our case companies.

Concerning the CEO’s leadership style, our findings partly extend Vaccaro et al. (Citation2012) reasoning on the importance of trust for the successful implementation of management innovations. Vaccaro argues that trust can be linked to both transactional and transformative leadership styles (Bass Citation1985); thus, both styles can result in successful implementation processes in small companies. Our observations (45–50 h in each company) confirm that our two successful cases represent a transformative leadership style. A style that highly contributed to the successful implementation of the management innovation. Hence, both CEOs early on had the idea to empower the employees when they entered the project.

The two successful cases are also characterised by high momentum in terms of the number and frequency of PO incidents reflecting increasing PO. This is in line with Robert et al.'s (Citation2019) finding that the timing aspect in implementation is important and that a successful process needs momentum. A notable finding in our study is related to the mixture of incidents signalling increasing and decreasing PO. High intensity in terms of the number and frequency of signals does not contribute to the effective implementation of management innovations if those signals are inconsistent. In such situations, organisational members seem to be confused.

Overall, our study addresses the dynamics related to PO in the implementation of management innovation. A PO perspective can help us understand some of the reasons why such processes sometimes fail and sometimes succeed. Thus, we do not claim that PO alone can explain successful management innovation. We therefore encourage further research on how implementation processes can both advance and deteriorate over time.

Conclusions

Academic contributions

We make three contributions to the literature on management innovations and PO.

Our main contribution to the understanding of management innovation processes is the introduction and exploration of the PO perspective (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2001) to the management innovation literature. Our study confirms extant research claiming that PO is essential to effective management innovation (Scherrer-Rathje, Boyle, and Deflorin Citation2009), as PO relates to the commitment aspect that surfaces in both rhetorical statements and technical elements. Furthermore, it suggests that in SMEs, implementation processes are usually initiated at the top management level but also need to be diffused to a broader basis of organisational stakeholders to ensure sustainability. Here, our findings complement Vaccaro et al.'s (Citation2012) ideas on how to balance transactional and transformational leadership when managing the implementation of management innovations in an SME context. Only where a broad set of organisational co-workers assumed PO of the management innovation and thus developed an intrinsic motivation to work with the innovation can we find successful implementation.

By using CIT for studying implementation processes from a PO perspective, we make a methodological contribution. To date, the dominant method in PO studies is self-reporting surveys, which have problems capturing micro-processes of how PO develops (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2003). We therefore used the CIT methodology to identify micro-indicators of PO in our existing data. In this way, we could detail our study and develop nine propositions on both the nature of the implementation process and on the individual and collective ownership of the management innovation. We hope this methodological approach can inspire more research on PO in management innovation implementation.

Finally, our article contributes to the literature by presenting a multicase study in an SME context. Investigating the implementation of management innovations in SMEs contributes to our general knowledge of management innovations, as SMEs, due to their limited size, offer an opportunity for researchers to gain a more holistic view of the implementation process. In the companies studied, we were able to regularly observe how management and operational staff interacted and hence the emergence of organisational PO, which would not have been possible with a more top management-focussed study. Furthermore, a focus on the SME context enriches our understanding of the implementation process in resource-constrained contexts (Harder Citation2011).

Managerial implications

The main implication for managers in this paper is that managers need to realise that management innovations do not arrive ready made for use in a specific context. Firms have their unique features such as organisational design, technology, identity and values that constrain what changes can be implemented successfully (Brunninge, Bueno Merino, and Grandval Citation2011; Brunninge and Melander Citation2015). However, as management innovations are typically characterised by some degree of interpretive viability (Benders and van Veen Citation2001), managers can adapt them to the context of the focal organisation. Successful adaptation and adoption of a management innovation includes managerial commitment and favourable organisational conditions. The latter need to be promoted actively.

This needs to include time for managers to learn about the innovation, time and resources to adapt the management innovation to the company context and the creation of an implementation strategy that ensures the needed individual and collective PO in the organisation. When implementing a management innovation that requires co-worker involvement, our study indicates the need to show both behavioural and rhetorical skills to create an inclusive and engaging milieu. To successfully implement a management innovation, organisational members need to perceive the innovation as ‘theirs’, i.e. they need to assume psychological ownership. While PO often starts on the level of the CEO, top management needs to promote its spread in the organisation. Among our cases, an apparent strategy that gained success was to take a collective approach and learn how to develop and use the management innovation collectively, thus promoting PO among employees. This approach was also well in line with the principles of Hoshin Kanri, the studied management innovation. It also resonates with extant research, emphasising the importance of endurance and organisational involvement in change management processes (Blombäck, Brunninge, and Melander Citation2013).

It should also be recognised that most management innovations will challenge the organisational balance. There will be winners, but there can also be losers in this political dimension. Managers should be attentive to communicating the benefits of management innovation for different groups of organisational members and be willing to mitigate its drawbacks. In this respect, general training in change management can equip managers to overcome possible resistance (cf. Klein and Sorra Citation1996).

Limitations and suggestions for future research

As the literature on management innovations is often based on data from successful cases in large firms, we regard the study of both successes and less successful cases in an SME context as a contribution in itself. Failures offer a good ground for learning.

However, our data do not allow us to generalise our findings to large firms that have more resources to commit to implementing a management innovation and where one can assume that the innovation task is likely to be delegated to middle managers. It would be very interesting to see an empirical study in such a context, particularly concerning the dynamics of PO, in a setting where less operational responsibility lies with top management. Do top managers still play a key role in implementing management innovation, and if so, what? Is it necessary to spread PO even among a large set of organisational members, and if so, can it be done in a similar manner as in SMEs?

It is regularly concluded that involvement from different stakeholders, especially top management, is critical when implementing management innovations (Nieves and Segarra-Ciprés Citation2015; Rasmussen and Hall Citation2016; Scherrer-Rathje, Boyle, and Deflorin Citation2009). This makes the characteristics of HK highly relevant for a detailed study of how PO evolves on an individual and organisational level. However, the strong emphasis on management and stakeholder inclusion in HK are not necessarily mirrored in all management innovations. Following Armbruster et al. (Citation2008), we believe that it is important to carefully classify and investigate the performative consequences of individual management innovations before generalisations are made. In particular, future research should investigate whether PO is spread in organisations in a similar manner when management innovation puts less emphasis on participation than Hoshin Kanri. Additionally, we would welcome attempts to test our findings on firms that engage in structural management innovations (Armbruster et al. Citation2008) to see whether processes relating to PO are similar to those in firms pursuing procedural management innovations such as Hoshin Kanri.

A further limitation in our study is that we evaluate the outcome of the implementation process merely in terms of changes in PO, and not by the performance of the focal management innovation (Hoshin Kanri) within the participating companies. By this, we can only discuss the characteristics of the implementation process in relationship to changes in PO. In this study, this limitation in the design was accepted, as the prime objective was to further our understanding of the process in which management innovations are implemented. However, we hope the results we developed can inspire further studies in which changes in PO can also be related to the performance of the studied management innovation.

Finally, in this paper, we applied critical incident theory (Butterfield et al. Citation2005) to study the early phases of PO change. This method has been used in PO research before (Man and Farquharson Citation2015; Gray, Knight, and Baer Citation2020; Tourish Citation2020), but it is rarely used in combination with observational data (Bott and Tourish Citation2016). Pescosolido (Citation2002) represents the only study detected, and in this study, the observations are combined with follow-up interviews. In this study, we have also added the recognition of incidents indicating both increase and loss of PO and separated between individual and collective PO (Pierce and Jussila Citation2010). Altogether, this exploratory use of the CIT method offers an opportunity to develop and validate more robust methods to capture early phases of management innovation implementation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anders Melander

Anders Melander is an Associate Professor of Management at Jönköping International Business School, Jönköping University. Anders research includes strategy, strategic change, strategic planning, Hoshin Kanri and family business. His work has been published in Management Decision, Journal of Management & Organisation, Journal of Management History, Scandinavian Economic History Review, International Studies of Management and Organisation, and Systemic Practice and Action Research.

Olof Brunninge

Olof Brunninge is an Associate Professor of Management at Jönköping International Business School, Jönköping University. Olof’s research interests lie in the areas of strategic management, organisational identity and self-understanding, corporate governance & ownership, family businesses, and social memory in organisations. His work has been published in journals such as Long Range Planning, International Studies of Management and Organisation, Small Business Economics, The Journal of Family Business Strategy and Journal of Organisational Change Management, and Marketing Theory.

David Andersson

David Andersson is a senior consultant and owner of Borand AB. David has more than 20 years’ experience from coaching in the manufacturing industry. His skills are in change management, kata & lean production and Hoshin Kanri. His work has been published in Management Decision and Systemic Practice and Action Research.

Fredrik Elgh

Fredrik Elgh is a Full Professor of Product Development at the department of Industrial Product Development, Production and Design, School of Engineering, Jönköping University. Fredrik’s earlier research focuses on cost engineering, design for producibility, design automation and knowledge-based engineering, but now also includes, design methodology, set-based concurrent engineering, product platforms, knowledge engineering and lean management with applications in automotive, aerospace, mechanical, consumer and house-building industry. His work has been published in journals such as Journal of Engineering Design, International Journal of Agile Systems and Management, Advanced Engineering Informatics, and Management Decision.

Malin Löfving

Malin Löfving (Ph.D. Chalmers University of Technology) is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at the School of Engineering, Jönköping University, and project manager and industrial coach at Träcentrum Nässjö Kompetensutveckling AB. Her research interest is in the area of manufacturing strategy in small and medium-sized enterprises. Her publications appear in journals such as Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management and Management Decision.

Notes

1 Vinnova, Sweden's innovation agency, financed 50% of the project. They approved the project plan and demanded a reporting structure to make sure the participating companies financed the remaining 50%. Otherwise, Vinnova did not influence the execution of the project in anyway.

References

- Abdallah, C., M. Lusiani, M , and A. Langley. 2019. “Performing Process Research.” In Standing on the Shoulders of Giants, edited by B. Boyd, T. R. Crook, J. K. Lê, and A. D. Smith, 91–114. Emerald Group Publishing. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Akao, Y. 1991. Hoshin Kanri: Policy Deployment for Successful TQM. New York, NY: Productivity Press.

- Amarakoon, U., J. Weerawardena, and M. L. Verreynne. 2018. “Learning Capabilities, Human Resource Management Innovation and Competitive Advantage.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 29 (10): 1736–1766. doi:10.1080/09585192.2016.1209228.

- Ansari, S. M., P. C. Fiss, and E. J. Zajac. 2010. “Made to Fit: How Practices Vary as They Diffuse.” Academy of Management Review 35 (1): 67–92.

- Armbruster, H., A. Bikfalvi, S. Kinkel, and G. Lay. 2008. “Organizational Innovation: The Challenge of Measuring Non-Technical Innovation in Large-Scale Surveys.” Technovation 28 (10): 644–657. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2008.03.003.

- Avey, J. B., B. J. Avolio, S. D. Crossley, and F. Luthans. 2009. “Psychological Ownership: Theoretical Extensions, Measurement and Relation to Work Outcomes.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 30 (2): 173–191. doi:10.1002/job.583.

- Babisch, P. 2005. Hoshin Handbook. Poway: Total Quality Engineering.