Abstract

This research investigates how a global engineering firm can implement a centrally managed, globally integrated supplier base. Based on in-depth evidence from a single longitudinal case study, we identify different approaches for the case company to integrate their local supplier base into a multi-step process: first, the company attempted supplier base reduction by ‘cutting the tail’ off a vast supplier base. Second, they prioritised suppliers based on groupings and importance across the global supply network. Third, the case company tested supplier relationship management with a small selection of suppliers, resulting in improving their own delivery performance. Based on these insights, we propose a conceptual framework of global supplier base management. We discuss this framework in relation to the supply management and global operations literature. This paper contributes to the operations and supply chain management literature by offering an initial understanding for global sourcing strategies through integrating a previously localised supplier base into a globally consistent approach to managing the supplier base.

1. Introduction

Many global engineering firms, such as Grundfos, Rolls Royce, and Volvo, seek to globalise their supply chain through a centralised sourcing strategy and a consistent approach to managing their supplier base (Mazahir and Ardestani-Jaafari Citation2020; Salimian, Rashidirad, and Soltani Citation2021, Citation2017; Ferdows Citation2018; Kreye Citation2022). As these companies have grown and dispersed their processes across a global network, their supply management has often been similarly dispersed and localised (Erfurth and Bendul Citation2018). While engineering and production processes have matured and developed into advanced production and engineering networks, supply strategies have often remained localised (Erfurth and Bendul Citation2018; Pana and Kreye Citation2021; Choi and Krause Citation2006). This can create difficulties in procurement as supplier relationships are often managed ad hoc based on local needs and managed in a globally inconsistent way (Rudberg and Martin West Citation2008). As a result, global engineering firms face an advanced global engineering network coupled with an immature supply network, characterised by locally managed supplier bases without a globally consistent overview or management approach. However, globalising these supply networks and their management offers potential benefits for increasing their comparative advantage by utilising dispersed capabilities (Friesl and Silberzahn Citation2012) and increasing global efficiency (Shi and Gregory Citation1998) as a response to competitive pressures (Sun and Pang Citation2017). As such, incentives to globalise sourcing strategies are increasing, and their effect on supply chain management is becoming increasingly evident.

While research on supplier base management and supplier relationship management has advanced significantly in recent years (Delbufalo Citation2017; Salimian, Rashidirad, and Soltani Citation2021), little research has addressed the creation of a globally consistent approach to managing a global supplier base in a global engineering firm. Existing works instead highlight the need to begin efforts to manage the number of firms within the supplier base (Holmen, Pedersen, and Jansen Citation2007; Gadde and Snehota Citation2019; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021). To this end, firms must identify an appropriate number of suppliers to enable the creation and management of meaningful long-term and strategic relationships (Delbufalo Citation2017; Formentini et al. Citation2019). In addition, some supply chains see an increase in localisation of sourcing through reshoring, a trend accelerated through recent disruption event, such as the Covid-19 pandemic and Brexit (Hoek and Dobrzykowski Citation2021). We argue that the supplier base—specifically, the number of suppliers in the supplier base—represents a meaningful starting point for globalising supply chain management efforts in global engineering companies, aligning with similar argumentation in the literature (Cousins Citation1999; Gadde and Snehota Citation2019; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021). Specifically, this research seeks to answer the following research question (RQ): How can a global engineering firm create a globally consistent approach to managing its global supplier base?

This research responds to calls for further investigations into global operations, which represents an understudied and underreported area within operations management (OM) literature (Ferdows Citation2018). Similarly, Zhang and Gregory (Zhang and Gregory Citation2011) point out that a uniform understanding of global engineering operations and how to design and operate global engineering networks is also lacking in the literature. Presenting in-depth evidence from a single longitudinal case study, we address this gap by investigating how the approach to managing a locally dispersed set of suppliers can be integrated into a globally consistent way through supplier base reduction and supplier prioritisation, creating global performance management. Based on these insights, we propose a conceptual framework of global supplier base management.

The contributions of this work arise from the combination of supplier relationship management (Park et al. Citation2010; Delbufalo Citation2017; Formentini et al. Citation2019) and global operations management (Cheng, Farooq, and Johansen Citation2015; Ferdows Citation2018). We propose a framework for integrating a global supplier base in a global engineering firm based on our empirical work and both literature streams—supplier relationship management and global operations management—offering important insights for researchers and guidance for managers in the process.

2. Literature review

2.1. Global engineering operations

Global engineering operations describes internationally dispersed production or service processes within a network of coordinated and controlled individual units (Rudberg and Martin West Citation2008; Zhang and Gregory Citation2011). Global engineering firms engineer the products they sell, ranging from design, (part) production, assembly, and distribution of their products within a global network of connected subsidiaries and suppliers. Global engineering accordingly covers a broad range of topics related to product design (Park et al. Citation2010), global production (Rudberg and Martin West Citation2008), and supply chain management (Lambert and Schwieterman Citation2012). In turn, procurement at global engineering firms is often highly complex with a need to balance global concerns of efficiency and consistency with local concerns of flexibility, heterogeneity and innovativeness (Steinle and Schiele Citation2008).

Global engineering companies face specific challenges regarding procurement and supply chain management, creating the setting for researching the topic of large supplier bases (Choi and Krause Citation2006; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021) and supply chain configurations (i.e. the level of globalisation or localisation, collaboration, and partnerships concerning suppliers) in order to strategically select suppliers and manage supply risk. To begin with, global engineering companies face a geographically dispersed and heterogeneous set of suppliers (Erfurth and Bendul Citation2018). For example, suppliers can range from small commodities, such as fasteners, to functional units for the final product that may require co-design and development, such as large castings or specialised materials for wear parts in large industrial machinery. The total number of suppliers often reaches many thousands. Finally, the decision-making power in global engineering firms is often dispersed as well (Zhang and Gregory Citation2011). Strategic choices regarding supplier selection may reside in a centralised unit (e.g. global procurement) while the management of supplier contact and relationships often occurs between engineers and local managers (Zhang and Gregory Citation2011). In other words, a single point of responsibility often does not exist.

In turn, these challenges create difficulties in implementing supplier relationship management in practice and often raise issues for global engineering companies regarding how to approach supplier relationship management. Supplier relationship management concerns the creation of close collaborative relationships with suppliers (Lambert and Schwieterman Citation2012), which aims to create joint competitive advantage (Dyer and Singh Citation1998) through joint product development or innovation, or joint resource investment and creation (Kreye and Perunovic Citation2020). Despite this, global supplier base management remains underreported in the engineering supply chain literature (Sabri, Micheli, and Cagno Citation2022). This constitutes a gap that this paper seeks to address.

2.2. Supplier base management

To enable effective supplier relationship management, a focal firm requires a ‘manageable’ supplier base (Eggert and Ulaga Citation2010) as well as the capabilities to manage close relationships with some of these suppliers (Eggert and Ulaga Citation2010; Miocevic and Crnjak-Karanovic Citation2012). An organisation’s supplier base constantly evolves as supplier relationships emerge, become closer, and terminate (Kreye and Perunovic Citation2020; Gadde and Snehota Citation2019; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021). As such, active management of the supplier base represents an important task for supply chain management (Salimian, Rashidirad, and Soltani Citation2021). A supplier base can be defined as those companies from which a focal organisation purchases its goods and services (Gadde and Snehota Citation2019) and which it actively manages (Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021). Furthermore, a supplier base constitutes a ‘most significant knowledge reservoir for the buying firm, as it contains a much more extensive set of resources than the resources available within the own company’ (Gadde and Snehota Citation2019). As such, suppliers make significant contributions to focal organisations’ efforts regarding, for example, innovation, manufacturing, product development, service development, and delivery of quality (L. M. Ellram and Ueltschy Murfield Citation2019; Ramirez Hernandez and Kreye Citation2021; Johnsen Citation2009; Schoenherr and Swink Citation2012; Holmen, Pedersen, and Jansen Citation2007; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021).

One of the core questions of supplier base management concerns supplier integration in terms of selecting an appropriate number of suppliers (Faes and Matthyssens Citation2009; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021). Specifically, globally operating engineering firms often pose a particularly challenging setting for supplier integration (Choi and Krause Citation2006; Faes and Matthyssens Citation2009; Holmen, Pedersen, and Jansen Citation2007) due to the large, globally dispersed, and heterogeneous supplier base (see also Section 2.1). This question can be linked to two important concerns. First, the number of suppliers in the supplier base may need to be reduced (Pressey and Mathews Citation2003; Eggert and Ulaga Citation2010; Holmen, Pedersen, and Jansen Citation2007), especially when integrating a large set of local suppliers into a globally and centrally managed supplier base (Feldmann and Olhager Citation2019). However, the choice of which suppliers to deselect from the supplier base may not be straightforward, especially in a global context, where the role and importance of local suppliers may not be recognisable by geographically and operationally removed organisational units. Second, the supplier base needs to be managed over time, relating to the supplier base’s long-term sustainability as a useful basis for supply chain management in the global engineering firm (Gadde and Snehota Citation2019; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021). In turn, this may create an incentive to increase the number of suppliers in the global supplier base by periodically adding suppliers for new product parts or new developments (e.g. L. Ellram and Tate Citation2015; Ramirez Hernandez and Kreye Citation2021). Therefore, the need to balance maintaining a supplier base that is small enough to be manageable and large enough for increased sourcing flexibility may form a central constraint for implementing a global strategy for supply chain management.

2.3. Conceptual framework

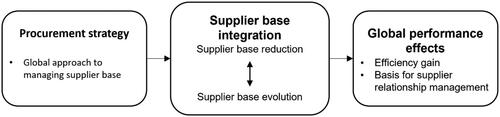

To investigate our research question, ‘How can a global engineering firm create a globally consistent approach to managing its global supplier base?’, we present an initial conceptual framework as depicted in . The framework shows how a global procurement strategy drives supplier base integration to create global performance effects. The global procurement strategy is operationalised through creating a globally consistent approach to managing the supplier base (Rudberg and Martin West Citation2008) and forms the starting point for this research. In this sense, the term ‘global’ refers to the strategic integration of various approaches to managing a globally dispersed supplier base rather than geographic location or other operational decisions. Supplier base integration can be operationalised through supplier base reduction (Pressey and Mathews Citation2003; Eggert and Ulaga Citation2010; Holmen, Pedersen, and Jansen Citation2007) and supplier base evolution (Gadde and Snehota Citation2019; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021), as outlined in more detail in Section 2.2. Supplier base integration constitutes the main focus of this work. Global performance effects focus particularly on potential efficiency gains of procurement through economies of scale in working with suppliers (Zhang and Gregory Citation2011) as well as the ability to build a meaningful basis for supplier relationship management through creating closer relationships with a long-term orientation (Lambert and Schwieterman Citation2012). Global performance effects stand in contrast to local performance effects such as the potential loss of a locally preferred suppliers (Steinle and Schiele Citation2008) or reduced flexibility in locally choosing a suitable supplier (Hoek and Dobrzykowski Citation2021). However, these local performance effects are outside of the scope of this research. Our goal is to investigate the characteristics and role of supplier base integration within the setting of global engineering firms. To this end, we depart from current frameworks of supplier base management and evolvement (Holmen, Pedersen, and Jansen Citation2007; Gadde and Snehota Citation2019; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021) by expanding and elaborating on them to fit the context of global engineering. We use this conceptual framework to guide our empirical study as described in more detail in the following section.

3. Method

With the strong business relevance of our research question, we present longitudinal evidence from a single case deriving from the strategic decision to implement supplier relationship management (SRM). Longitudinal research was chosen for this effort based on its suitability for studying the challenges in global operations (Ferdows Citation2018), thereby overcoming issues of data availability and complexity. Furthermore, embedded longitudinal research tackles research objectives in real organisational contexts where research can otherwise be difficult, expensive, or impossible to replicate (Romano and Formentini Citation2012). In addition, we chose a single case study to enable rich and in-depth discussions of the complex internal and external considerations related to supplier base management (Lambert and Schwieterman Citation2012), including the global organisational hierarchy, heterogeneity of suppliers (Erfurth and Bendul Citation2018) and local and global procurement needs (Rudberg and Martin West Citation2008). The study process represents a joint effort between the researcher(s) and practitioner stakeholders to find solutions through an iterative process of interim learnings and development (Childe Citation2011; Coughlan and Coghlan Citation2002).

3.1. Case selection

The case company was selected based on theoretical selection criteria for this research. First, the case company comprises a global engineering firm with a dispersed global network of engineering-related activities, including product design and development (Park et al. Citation2010), production (Rudberg and Martin West Citation2008), service provision (Pana and Kreye Citation2021), and supply chain management (Lambert and Schwieterman Citation2012). This aligns with typical characterisations of global engineering (Zhang and Gregory Citation2011). Second, the company has been implementing a global strategy in its global organisation, striving for a more centralised approach to managing its operations (Rudberg and Martin West Citation2008; Zhang and Gregory Citation2011). This includes a global purchasing strategy aimed at creating a globally consistent approach to managing the supplier base (Rudberg and Martin West Citation2008). Third, the case company was in the process of implementing a more relational approach to managing supplier relationships in their global setup, aligned with descriptions in the supplier relationship management literature (Formentini et al. Citation2019). This aligns with the secondary global performance effect of conceptual framework (creating a basis for supplier relationship management. The case company thus constitutes an appropriate example for investigating our research question.

The case company is headquartered in Denmark and operates within the global heavy equipment and plant manufacturing industries. In addition to the headquarter (HQ), the company has offices in seven regions and multiple subsidiaries globally. Traditionally, the case company has sourced most of its products and product parts from low-cost countries, following long stretches of outsourcing activities. Most suppliers were chosen locally based on specific requirements and existing relationships. This approach has resulted in a large supplier base with low synergies across the global supply chain.

The focus of this research concerns the procurement department of the case company, who was responsible for managing the set of supplier relationships with the supplier base consisting of first-tier suppliers. This represents an appropriate unit of analysis, as they had already identified supplier base management as a business process they wanted to implement in a continued move towards more strategic procurement. Following strategic evaluations, the case company initiated an internal programme for strategic procurement aimed at integrating their supplier base and developing an approach for global SRM in 2017. This programme was implemented through three focussed projects relevant for this research—namely, supplier base reduction, supplier rationalisation, and delivery performance. Other projects included in the programme, such as the creation and management of a supplier database, including performance data, supplier scorecards, supplier sustainability screenings, and supplier financial monitoring, culminated in the three investigated projects, and were thus indirectly included in our investigations. Additionally, one of the researchers had followed this programme closely since January 2019 and completed important programme tasks.

3.2. Data collection

Multiple sources of data were collected, including semi-structured interviews, presentations given in the case company’s procurement department, observations, and participation in various programmes related to SRM (Yin Citation2018). As one of the researchers was closely involved with the case company’s strategic procurement programme, rich data were collected throughout the process of creating a globally consistent approach to managing the supplier base via embeddedness and organisational participation. This enabled the collection of rich observational data in addition to secondary data throughout the process from March 2019 to June 2021. This longitudinal data set was complemented by retrospective semi-structured interviews with core respondents (Childe Citation2011) enabling a targeted time to reflect on the process and core learnings. The core respondents were within the case company’s global procurement department and were chosen based on their experience and expertise in the field. The interviews provided the opportunity to understand the interviewees’ experiences and contextual setting through discussion, as well as to further clarify possible assumptions and misunderstandings. Interviewees were selected based on their immediate relevance to the strategic procurement programme—specifically to the supplier base integration—and included the procurement group level and regional procurement managers. A total of 12 semi-structured interviews were accordingly conducted, as listed in . The interviews were guided by an interview protocol focussing on supplier selection and managing supplier relationships over time (see Appendix A). The interviewees were asked to reflect on both the current state of these topics and how they envisioned them in the future. The interviews were conducted face-to-face over videoconference in the first half of 2021. They averaged 30 min in length and were recorded and transcribed for analysis. These multiple sources of data enabled the researchers to establish a chain of evidence for construct validity (Gibbert, Ruigrok, and Wicki Citation2008).

Table 1. Summary of data collection.

3.3 Data analysis

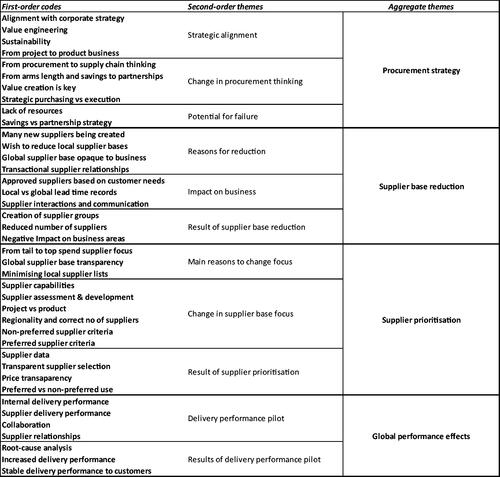

The unit of analysis is the purchasing function responsible for global supplier base management by the case company’s procurement department. The data were coded iteratively based on the RQ and knowledge from the literature review. The semi-structured interviews were employed as a gateway to the otherwise unstructured and rich longitudinal case data (). These transcribed interviews were initially coded deductively based on four aggregated thematic categories from the SRM literature—namely, purchasing strategy, supplier selection, collaboration, and supplier assessment and development (Park et al. Citation2010). Following this, each thematic category was coded in more detail based on an inductive process for more detailed analysis, resulting in more than 50 initial descriptive codes. This step led the researchers to focus specifically on supplier selection following the implementation of a global procurement strategy, in turn resulting in an iterative reframing of the research focus on supplier base integration. The longitudinal primary and secondary data were employed to triangulate the initial descriptive codes and to confirm and enrich the developed insights and identify the longitudinal process related to a global procurement strategy, supplier base reduction, supplier prioritisation, and global performance effects. The iterative process enabled the researchers to develop a progressive understanding and interpretation of the combined empirical data. Through this process, the authors combined emerging insights with the literature, exploring concepts beyond SRM to develop an increasingly abstract understanding to answer our research question. depicts the coding tree, representing how primary codes, secondary codes, and aggregate themes relate. This iterative process, based on empirical data and the literature, facilitated theory building (Miles, Michael Huberman, and Saldaña Citation2014, 292–293) and ensured internal validity by connecting emerging insights to theory-related concepts (Gibbert, Ruigrok, and Wicki Citation2008).

4. Findings

4.1. Procurement strategy

The case company’s purchasing strategy reflects their corporate strategy, being anchored in the market and stakeholder needs with the goal of ‘delivering sustainable productivity to our customers’ and value to the company (internal case company strategy overview document). Until 2016, the case company focussed on cost savings through price negotiations, with decentralised sourcing run by each of the seven regions. This means that the case company purchased the same type of product from various different suppliers based on the individual regions’ local knowledge and sourcing capabilities. The shift towards a more globalised procurement strategy started in 2016 because ‘we needed a strategy strengthening our procurement organisation, focussing more on performance management, talent, procurement roles and how we collaborate…since 2016, we have aligned our procurement organisation with all regional procurement heads reporting directly to our CPO [central procurement office]’ (internal procurement strategy document).

As part of the move towards a global procurement strategy, the case company wanted to stop the constant addition of new suppliers by creating a manageable, transparent global supplier base. The SRM programme manager describes this as follows: ‘If they [procurement] just evaluate and think about why a certain supplier is chosen, and if we already have a supplier in our portfolio we can use, [I hope that we] get away from selecting suppliers locally and where we find [new] suppliers that we will not use much in the future and that add to our portfolio all the time. So, in short, [I hope] that we take control over who we use’. This reflection demonstrates the complex interaction between reducing the supplier base and managing it over time by establishing a standardised approach to selecting suppliers. Globalisation of supplier base management requires consideration of not only the heterogeneous geographic needs, but also the different business functions. Global category manager 3 described this as follows: ‘It can do no good that we in procurement—like now—go out and say we have to save a lot of money, but our colleagues in engineering and product line management are fairly content with the prices. It is more important for them to ensure proper agreements or conditions with the suppliers on the collaboration front’. This indicates the different supply needs in the different departments of the case company, which, in turn, requires consideration in the global supplier strategy.

Ultimately, the value of this global integration would be to increase supplier cooperation to increase the value provided to the case company. As the senior procurement manager explained, ‘If you want to work with supplier collaboration and improve the processes at the supplier, look at their setup, look at their supply chain, look at value engineering. It demands something different from you; it takes more time, you need patience to work with this, but it has a better effect’. This indicates that the case company had identified the potential value of SRM for their business with a changing focus in procurement away from the traditional emphasis on execution and cost savings. To achieve these potential benefits, the company underwent a multi-year process of supplier base reduction, supplier prioritisation, and delivery performance improvement, subsequently realising benefits of global supply management.

4.2. Supplier base reduction

Initially, the case company attempted to reduce the massive global supplier base by 30% in each region. This effort aimed at ‘cutting the tail’ off low-spending local suppliers and creating a manageable supplier base as indicated by the Central Procurement Officer in a bi-weekly update to the entire procurement organisation: ‘My favourite thing is that you are allowed to work with as many suppliers as you can remember. Their full name, their postal code, or an account manager there…beyond this number of preferred suppliers, the tail is too big’ (internal procurement communication, 2021). To this end, the case company initiated a centrally governed programme for supplier base reduction, which included a series of workshops with all the global category managers and later with regional stakeholders, tasking them with choosing what suppliers over a certain spend threshold should be cut either immediately or gradually. Through the SBRP, the case company reduced its supplier base from more than 50,000 individual suppliers to approximately 40,000 individual suppliers. In addition to this reduction, the suppliers were mapped so the managers and stakeholders could better understand the historic use of the suppliers and their possible affiliation with other suppliers. In turn, this resulted in the definition of supplier groups where local entities or subsidiaries of companies were mapped under the umbrella of the parent company, producing a supplier base of approximately 8000 supplier groups.

However, the supplier base reduction resulted in some disruptions to different business areas, such as the aftermarket and project business, as stated by the senior procurement manager: ‘I think it is hopeless making such a hardcore cut…. you are disrupting the aftermarket, who are the ones using all these smaller suppliers’. The aftermarket division relies on quick and often local supplier support to respond rapidly to its customers’ maintenance requirements. Specifically, local procurement managers raised concerns, as important suppliers that were not used frequently, but which the case company remained dependent on, were deleted from the supplier base. In addition, the programme suggested that local procurement teams could mark suppliers as preferred, which would protect them from deactivation. This would be used extensively by regional teams, who could mark suppliers as ‘preferred’, ‘phase out’, or ‘induced by case company’s customers’. These issues resulted in the SBRP taking a lot longer than anticipated (based on observations). This demonstrates the need to understand why suppliers are used within the global business (product and service based) to evaluate which suppliers can be deleted from the supplier base. As a result, after roughly a year, a different approach to reducing the supplier base replaced the SBRP.

4.3. Supplier prioritisation

The case company subsequently focussed on supplier prioritisation, which refocussed the efforts from avoiding tail-end suppliers to identifying the suppliers that can cover the supply needs of the different internal stakeholders. As the supplier rationalisation programme lead remarked, ‘The future vision is to use our top 1,000 suppliers more; it is not to focus on using smaller suppliers less, but to use bigger suppliers more’. This focus on pushing certain suppliers into (more frequent) use, combined with a policy of deactivating suppliers not used for a rolling three-year period, would subsequently reduce the supplier base in the long term and focus strategic initiatives on the suppliers where the case company engages most of their spending.

The outcome of supplier prioritisation was a supplier base split into five categories, as summarised in . The 550 globally and regionally preferred supplier groups were identified based on existing positive relations as well as high spending or potential for high spending. The vast majority of the remaining 7,500 supplier groups were identified as non-preferred, with few supplier groups being categorised as either ‘to be avoided’ or ‘blacklisted’.

Table 2. Supplier prioritisation based on globally defined categories (based on case company official categorisation material).

This categorisation is not fixed, as the case company seeks to define a supplier base of preferred suppliers that are attractive to use as well as to promote use of them to all relevant stakeholders in the case company. Regular follow-up activities, especially when suppliers fall into the ‘avoid’ or ‘blacklisted’ categories, further encourage use of preferred suppliers over others. During categorisation, the damage of the prior approach to supplier base reduction could be felt during supplier prioritisation. Based on researcher observation, the hard cutting of suppliers from supplier rationalisation (Section 4.1) to the supplier categorisation system resulted in regions fearing that if suppliers were labelled non-preferred, they would be removed. The wording of ‘non-preferred’ remains misunderstood and debated in meetings with the regions well beyond the case programme reported in this paper.

4.4. Global performance effects

Through the two programmes, the case company achieved their goal of centralising and reducing their suppliers to increase supply performance. The SBRP resulted in a shortened aggregated global list of suppliers, providing a better understanding of supplier groups. This provided the case company with improved visibility of global spending with a supplier group and, in turn, higher negotiation power, as prices and terms can be negotiated collectively for each supplier group, eliminating the need to do so for all individual suppliers within a group. While this may in turn have enabled suppliers to have greater visibility of the ordering volume by the case company, the main performance benefit was the increased negotiation power due to groupings of orders by the case company. Supplier rationalisation, meanwhile, resulted in obtaining a better global overview of the supplier base with related visibility of the global market for each of the regions. Through the ongoing category meetings and tools such as up-to-date supplier performance dashboards created in the SRP, each region now possesses enhanced access to knowledge regarding the existing global supplier base, as well as negotiated prices. Managing supply and the supplier base in turn enables the case company to increase the value they deliver to their customers.

The two supplier base management programmes were complemented by a programme targeted at performance improvements after the case company realised that 60–70% of the problems in delivering on time to the case company’s customers were caused by late deliveries from suppliers. This realisation and an increased focus on delivery performance more generally led the case company to work more closely with 12 supplier groups in a pilot programme to collaboratively increase delivery performance towards the case company. Through this programme, appointed supplier leads from the case company, guided by central delivery performance programme managers, worked directly with each supplier group to map root causes for supply delays and agree upon concrete improvement initiatives to improve the delivery performance to the case company. After eight months of the programme, the case company witnessed significant improvements in measured delivery performance with suppliers where root causes were identified and addressed. The delivery performance programme has resulted in more stable delivery performance towards the case company’s customers from suppliers included in the programme even during the COVID-19 pandemic. summarises the three programmes presented, with core activities and main achievements for the case company.

Table 3. Case initiatives to achieve global supply management.

5. Discussion

5.1. Concept development

The case company’s initial step of reducing their supplier base was valuable, as this enabled them to map and aggregate their global supply base and to group related suppliers and create visibility of their global suppliers (Razak, Hendry, and Stevenson Citation2021). Supply chain visibility is often seen as a prerequisite for effective supplier base management aimed at supply chain traceability (Razak, Hendry, and Stevenson Citation2021), particularly in sourcing or procurement decisions (Ma et al. Citation2022). This also reflects the need to reduce the supplier base before engaging in supplier relationships management (Pressey and Mathews Citation2003; Eggert and Ulaga Citation2010; Holmen, Pedersen, and Jansen Citation2007). The case company’s initial approach of ‘cutting the tail’ off suppliers in terms of frequency in use proved problematic. This reflection mirrors descriptions in the literature on supplier interactions indicating that infrequently used supplies may still remain business critical (Levin, Walter, and Keith Murnighan Citation2011; Lopes, Brito, and Alves Citation2013; Hurmelinna Citation2018; Pick et al. Citation2016). Instead, the case company focussed on grouping their supplier base, effectively creating global supplier segments (Kraljic Citation1983; Formentini et al. Citation2019). Instead of the typically described approach of supplier segmentation based on value of the supplied product, the case company based the supplier segments on organisational characteristics, such as company groups or subsidiaries. This approach may relate to the large scale of the global supplier network (Choi and Krause Citation2006; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021), which provides a largely incompatible basis for grouping suppliers based on few characteristics, such as complexity of the supplied product or part (Formentini et al. Citation2019). The case observations of reducing the supplier base may thus relate to the global nature of the case company and hence complement approaches described in the literature.

Following supplier base reduction, the prioritisation of suppliers enabled the case company to further reduce the global supplier base and focus supplier engagement efforts. This indicates that supplier prioritisation is dynamic and dependent on shifting business needs, reflecting observations in the literature (Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021). By defining different categories of preferred suppliers, the case company shifted the focus from the tail towards the top supplier groups. While this step reflects approaches described in the literature, the implementation of prioritisation in the case company differs from, for instance, purchasing portfolio models (Kraljic Citation1983; Formentini et al. Citation2019). The case company’s prioritisation efforts were based on previous buying history in the form of monetary spending, as well as local and global category knowledge, which was based on the purchasing needs of the different business areas to create a global repository of experience working with different suppliers. In contrast, existing purchasing portfolio models require advanced procurement data and skills (Kraljic Citation1983; Formentini et al. Citation2019). This observation may reflect the lower level of maturity in supplier base management capabilities in the case company specifically and potentially in global engineering firms more broadly, reverberating the need to build more specific theory for global engineering firms (Zhang and Gregory Citation2011; Ferdows Citation2018).

The global performance effects of creating a globally consistent approach to managing the supplier base related to the case company improving their own delivery performance through close collaboration with a chosen subset of suppliers. The case company’s pilot project suggests that close interaction with a selection of key suppliers can result in performance benefits aligned with the literature (Miocevic and Crnjak-Karanovic Citation2012; Leppelt et al. Citation2013; Kähkönen and Lintukangas Citation2018). In turn, the suppliers’ willingness to participate and contribute to the pilot project suggests that they prioritised the case company as a key customer, which could be a result of the supplier base reduction and prioritisation efforts (Dubois Citation2003). This indicates the potential value of implementing SRM in a global engineering firm; however, this is resource intensive, as procurement people need to work directly with the suppliers. For the case company, these effects lend credibility to efforts to map the global supply base, reduce the supplier base, and prioritise suppliers, and provide a goal for these efforts.

5.2. Creating globally consistent approach to supplier base management

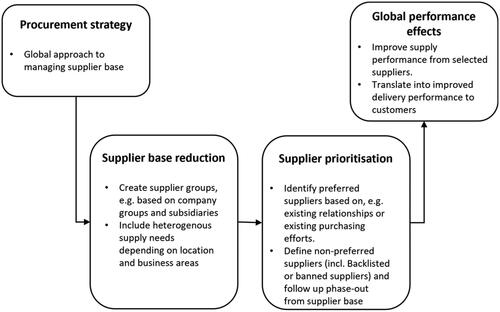

We summarise the process of creating a globally consistent approach to managing the supplier base into a proposed framework, as depicted in . The framework details the two steps to integrate the supplier base of a global engineering firm based on our case findings and reflections on the literature, as presented in Section 5.1. These two steps are supplier base reduction and supplier prioritisation, creating global performance effects. Each of these steps has specific characteristics for global engineering firms, and we identified these characteristics through our empirical study.

Figure 3. Proposed framework for creating globally consistent approach to managing the supplier base in global engineering firms.

The proposed framework differs from other frameworks for supplier relationship management (Park et al. Citation2010; Formentini et al. Citation2019), which have traditionally described how to repeatedly engage with a focussed set of suppliers to achieve joint benefits. Instead, our framework focusses on the steps required before engaging in such efforts. We connect these steps to the specific characteristics of global engineering firms, who deal with large, geographically dispersed, and heterogeneous suppliers. Our framework illustrates the steps necessary to integrate these suppliers, following the definition of a global procurement strategy. These steps include supplier base reduction and supplier prioritisation.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we investigated the following research question: ‘How can a global engineering firm integrate its local supplier base into a globally integrated supplier base?’ To this end, we expanded on and contextualised existing frameworks regarding supplier base management and evolvement in the setting of global engineering companies. Our findings suggest that a strategic call from procurement to centralise the supplier base and manage supplier relationships leads to three focussed activities: (1) supplier reduction and rationalisation, (2) supplier prioritisation, and (3) supplier relationship management. First, the large supplier base needs to be reduced and rationalised in order to provide a global, centralised, and manageable supplier base and to create a transparent and unified understanding regarding this supplier base. Second, which suppliers to focus on should be prioritised, determined by defining preferred suppliers and, thereby, also non-preferred suppliers, as this enables a deeper understanding of the global supplier base. Third, based on this newfound understanding, supplier relationship management should be performed, where specific suppliers are chosen for close collaboration.

This paper contributes to the literature with two specific contributions. First, our work expands on existing frameworks for supplier relationship management (Lambert and Schwieterman Citation2012; Dubois, Gadde, and Mattsson Citation2021; Formentini et al. Citation2019) by focussing on the preliminary steps required to integrate a supplier base and develop the necessary internal understanding regarding the global supplier base before engaging in close collaboration. The proposed framework () offers initial guidance into the activities necessary to integrate the supplier base in preparation for strategic supplier relationship management. Second, this research contributes to the field of global operations management (Cheng, Farooq, and Johansen Citation2015; Ferdows Citation2018) by illustrating the specific supply-chain management challenges faced by global engineering firms. By including global operations in our theoretical framing and conceptual development following empirical analysis, this research further enriches discussions regarding global operations and, specifically, the need to integrate and manage global supplier bases.

The managerial implications of our research are linked to the proposed conceptual framework (): first, we demonstrate that, in the contextual case of a global engineering firm, the purchasing function is becoming more strategic and has begun a transition from local decentralised units towards a more unified global supply chain. This translates into a procurement strategy for centralising the supplier base and the goal of proactively and centrally managing supplier relationships. Second, in order to centralise and manage the supplier base, the supplier base has to become manageable. To this end, ‘cutting off the tail’ was revealed to produce some negative effects on business operations, meaning that managers should consider potential heterogeneous needs in the business. When centralising the supplier base, managers can instead group individual suppliers into supplier groups that are all under the same parent company, thus greatly reducing the supplier base. Subsequently, these supplier groups make it easier to negotiate globally based on a total monetary volume with the group, as well as to gather all performance data under one umbrella. Third, managers can prioritise supplier groups even with limited available procurement data. This can be accomplished based on, for instance, monetary spending and existing local and global category knowledge, but can also include other metrics if such metrics are available. Fourth, and finally, we demonstrate that, when the supply base is grouped and prioritised, proactive supplier relationship management initiatives can be rolled out in collaboration with the identified key suppliers. In this case, first efforts indicated that, despite needing some procurement resources, clear improvements in delivery performance towards the case company, and thereby the end customers, were possible.

Several limitations apply to this research. First, qualitative case study research can be criticised for its potential for researcher bias (Siggelkow Citation2007), which is a particular risk for this study given the close relationship between one of the researchers and the case company, with the researcher working in the described programme for multiple years. This risk was mitigated through rigour in research framing, data collection, and analysis (Gibbert, Ruigrok, and Wicki Citation2008) as well as maintaining a close relationship to the literature in the field to shape the focus of the research and conduct of the empirical study. This involved discussion, refinement, and analysis of the research findings with other researchers who had no connection to the case company. Similarly, collecting semi-structured interviews provided a structured basis for data analysis, limiting the effect of recall bias from the researcher (Yin Citation2018). Second, the qualitative study is not statistically generalisable. For this study, we present a rich contextual account from a previously underreported area of global engineering companies, enabling the exploration of novel insights with a limited understanding in the literature. Based on unique data access, we can further describe longitudinal changes instead of simply providing a snapshot of reality. A rigorous analysis process further enabled us to provide abstract generalisability from our data (Gibbert, Ruigrok, and Wicki Citation2008), which we discuss critically. Third, the data was collected during the global COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced processes and reflections through an increase in localising supply (Hoek and Dobrzykowski Citation2021) to create flexibility (Steinle and Schiele Citation2008).

Finally, this research reveals important avenues for future research: first, because the basis of this research concerned a single case study, with the related limitations, further case studies of large buying firms’ approaches to supplier base management are needed. This may subsequently reveal findings that provide further nuances to our insights and potentially expand on specific activities identified in our study. Second, this research points towards the potential focus of supplier relationship management activities on specific types of suppliers in the global supplier base. However, more work is needed to identify—from both buyer and supplier perspectives—which types of exchange settings are particularly beneficial for supplier relationship management. Third, our research demonstrates the transformative nature of implementing supplier relationship management in a global engineering firm, which has traditionally focussed on transactional (cost-based) relationships. Transforming these relationships into relational set-ups, however, requires a fundamental shift in mindset from both buyers and suppliers, providing important directions for further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bjørn Skjønning Andersen

Dr. Bjørn Skjønning Andersen has received his PhD candidate from the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), in the Department of Technology, Management and Economics and has since worked in the Global Procurement Department at FLSmidth in Denmark. He obtained his MSc in Operations and Management Engineering from Aalborg University (AAU). The focus of his PhD is on Strategic procurement and Supplier Relationship Management.

Melanie E. Kreye

Prof. Dr. Melanie Kreye is Professor of Operations and Supply Chain Management at the School for Business and Society, University of York, UK. She joined the School from the Technical University of Denmark (DTU). Her research area is Operations Management and she focuses on topics related to sustainable supply chain management and service operations within manufacturing industry including services offerings development, circular economy and the management of uncertainty. She is an Associate Editor with the International Journal of Operations and Production Management and Board member of EurOMA.

References

- Cheng, Yang, Sami Farooq, and John Johansen. 2015. “International Manufacturing Network: Past, Present, and Future.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 35 (3): 392–429. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-03-2013-0146.

- Childe, Stephen J. 2011. “Case Studies in Operations Management.” Production Planning & Control 22 (2): 107–107. doi:10.1080/09537287.2011.554736.

- Choi, Thomas Y., and Daniel R. Krause. 2006. “The Supply Base and Its Complexity: Implications for Transaction Costs, Risks, Responsiveness, and Innovation.” Journal of Operations Management 24 (5): 637–652. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2005.07.002.

- Coughlan, Paul, and David Coghlan. 2002. “Action Research for Operations Management.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 22 (2): 220–240. doi:10.1108/01443570210417515.

- Cousins, Paul D. 1999. “Supply Base Rationalisation: Myth or Reality?” European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 5 (3–4): 143–155. doi:10.1016/S0969-7012(99)00019-2.

- Delbufalo, Emanuela. 2017. “The Effects of Suppliers’ Trust on Manufacturers’ Innovation Capability: An Analysis of Direct versus Indirect Relationships.” Production Planning & Control 28 (14): 1165–1176. doi:10.1080/09537287.2017.1350766.

- Dubois, A. 2003. “Strategic Cost Management across Boundaries of Firms.” Industrial Marketing Management 32 (5): 365–374. doi:10.1016/S0019-8501(03)00010-5.

- Dubois, Anna, Lars Erik Gadde, and Lars Gunnar Mattsson. 2021. “Purchasing Behaviour and Supplier Base Evolution – A Longitudinal Case Study.” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 36 (5): 689–705. doi:10.1108/JBIM-11-2018-0328.

- Dyer, Jeffrey H., and Harbir Singh. 1998. “The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage.” The Academy of Management Review 23 (4): 660–679. doi:10.2307/259056.

- Eggert, Andreas, and Wolfgang Ulaga. 2010. “Managing Customer Share in Key Supplier Relationships.” Industrial Marketing Management 39 (8): 1346–1355. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.03.003.

- Ellram, Lisa M., and Monique L. Ueltschy Murfield. 2019. “Supply Chain Management in Industrial Marketing–Relationships Matter.” Industrial Marketing Management 79 (March): 36–45. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.03.007.

- Ellram, Lisa, and Wendy L. Tate. 2015. “Redefining Supply Management׳s Contribution in Services Sourcing.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 21 (1): 64–78. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2014.10.001.

- Erfurth, Toni, and Julia Bendul. 2018. “Integration of Global Manufacturing Networks and Supply Chains: A Cross Case Comparison of Six Global Automotive Manufacturers.” International Journal of Production Research 56 (22): 7008–7030. doi:10.1080/00207543.2018.1424370.

- Faes, Wouter, and Paul Matthyssens. 2009. “Insights into the Process of Changing Sourcing Strategies.” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 24 (3/4): 245–255. doi:10.1108/08858620910939796.

- Feldmann, Andreas, and Jan Olhager. 2019. “A Taxonomy of International Manufacturing Networks.” Production Planning & Control 30 (2–3): 163–178. doi:10.1080/09537287.2018.1534269.

- Ferdows, Kasra. 2018. “Keeping up with Growing Complexity of Managing Global Operations.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 38 (2): 390–402. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-01-2017-0019.

- Formentini, Marco, Lisa M. Ellram, Marco Boem, and Giulia Da. 2019. “Finding True North: Design and Implementation of a Strategic Sourcing Framework.” Industrial Marketing Management 77 (September 2018): 182–197. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.09.006.

- Friesl, Martin, and Raphael Silberzahn. 2012. “Challenges in Establishing Global Collaboration: Temporal, Strategic and Operational Decoupling.” Long Range Planning 45 (2–3): 160–181. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2011.11.004.

- Gadde, Lars Erik, and Ivan Snehota. 2019. “What Does It Take to Make the Most of Supplier Relationships?” Industrial Marketing Management 83 (May): 185–193. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.07.003.

- Gibbert, M., W. Ruigrok, and B. Wicki. 2008. “What Passes as a Rigorous Case Study?” Strategic Management Journal 29 (13): 1465–1474. doi:10.1002/smj.

- Hoek, Remko van, and David Dobrzykowski. 2021. “Towards More Balanced Sourcing Strategies – Are Supply Chain Risks Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic Driving Reshoring Considerations?” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 26 (6): 689–701. doi:10.1108/SCM-09-2020-0498.

- Holmen, Elsebeth, Ann Charlott Pedersen, and Nikolai Jansen. 2007. “Supply Network Initiatives - A Means to Reorganise the Supply Base?” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 22 (3): 178–186. doi:10.1108/08858620710741887.

- Hurmelinna, Pia. 2018. “Exiting and Entering Relationships: A Framework for Re-Encounters in Business Networks.” Industrial Marketing Management 70 (July 2017): 113–127. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.07.010.

- Johnsen, Thomas E. 2009. “Supplier Involvement in New Product Development and Innovation: Taking Stock and Looking to the Future.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 15 (3): 187–197. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2009.03.008.

- Kähkönen, Anni Kaisa, and Katrina Lintukangas. 2018. “Key Dimensions of Value Creation Ability of Supply Management.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 38 (4): 979–996. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-04-2016-0189.

- Kraljic, Peter. 1983. “Purchasing Must Become Supply Management.” Harvard Business Review (September-October): 109–117.

- Kreye, M. E., and Z. Perunovic. 2020. “You Don’t Forget Where You Come from: Linking Formation and Operations in Publicly Funded Innovation Networks.” Production Planning & Control 31 (10): 816–828. doi:10.1080/09537287.2019.1693066.

- Kreye, Melanie E. 2022. “When Servitized Manufacturers Globalise: Becoming a Provider of Global Services.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 42 (10): 1521–1543. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-11-2021-0714.

- Lambert, Douglas M., and Matthew A. Schwieterman. 2012. “Supplier Relationship Management as a Macro Business Process.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 17 (3): 337–352. doi:10.1108/13598541211227153.

- Leppelt, Thomas, Kai Foerstl, Carsten Reuter, and Evi Hartmann. 2013. “Sustainability Management beyond Organizational Boundaries–Sustainable Supplier Relationship Management in the Chemical Industry.” Journal of Cleaner Production 56 (October): 94–102. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.10.011.

- Levin, Daniel Z., Jorge Walter, and J. Keith Murnighan. 2011. “Dormant Ties: The Value of Reconnecting.” Organization Science 22 (4): 923–939. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0576.

- Lopes, Luísa, Carlos Brito, and Helena Alves. 2013. “Customer Relationship Reactivation in the Telecommunications Sector.” Proceedings of the 3rd INBAM Conference. International Network of Business and Management Journals, 1–17.

- Ma, Jie., Ying Kei Tse, Minhao Zhang, and Jill MacBryde. 2022. “Quality Risk and Responsive Actions in Sourcing/Procurement: An Empirical Study of Food Fraud Cases in the UK.” Production Planning & Control 1–12. doi:10.1080/09537287.2022.2080125.

- Mazahir, Shumail, and Amir Ardestani-Jaafari. 2020. “Robust Global Sourcing under Compliance Legislation.” European Journal of Operational Research 284 (1): 152–163. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2019.12.017.

- Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Miocevic, Dario, and Biljana Crnjak-Karanovic. 2012. “The Mediating Role of Key Supplier Relationship Management Practices on Supply Chain Orientation-The Organizational Buying Effectiveness Link.” Industrial Marketing Management 41 (1): 115–124. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.11.015.

- Pana, M., and M. E. Kreye. 2021. “Managing the Global Service Transition: Employees’ Reactions and Management Responses.” Production Planning & Control 1–13. doi:10.1080/09537287.2021.2005839.

- Park, Jongkyung, Kitae Shin, Tai Woo Chang, and Jinwoo Park. 2010. “An Integrative Framework for Supplier Relationship Management.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 110 (4): 495–515. doi:10.1108/02635571011038990.

- Pick, Doreén, Jacquelyn S. Thomas, Sebastian Tillmanns, and Manfred Krafft. 2016. “Customer Win-Back: The Role of Attributions and Perceptions in Customers’ Willingness to Return.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 44 (2): 218–240. doi:10.1007/s11747-015-0453-6.

- Pressey, Andrew D., and Brian P. Mathews. 2003. “Jumped, Pushed or Forgotten? Approaches to Dissolution.” Journal of Marketing Management 19 (1–2): 131–155. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2003.9728204.

- Ramirez Hernandez, Tabea, and Melanie E. Kreye. 2021. “Uncertainty Profiles in Engineering-Service Development: Exploring Supplier Co-Creation.” Journal of Service Management 32 (3): 407–437. doi:10.1108/JOSM-08-2019-0270.

- Razak, Ghadafi M., Linda C. Hendry, and Mark Stevenson. 2021. “Supply Chain Traceability: A Review of the Benefits and Its Relationship with Supply Chain Resilience.” Production Planning & Control 1–21. doi:10.1080/09537287.2021.1983661.

- Romano, Pietro, and Marco Formentini. 2012. “Designing and Implementing Open Book Accounting in Buyer–Supplier Dyads: A Framework for Supplier Selection and Motivation.” International Journal of Production Economics 137 (1): 68–83. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2012.01.013.

- Rudberg, Martin, and B. Martin West. 2008. “Global Operations Strategy: Coordinating Manufacturing Networks.” Omega 36 (1): 91–106. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2005.10.008.

- Sabri, Yasmine, Guido J. L. Micheli, and Enrico Cagno. 2022. “Supplier Selection and Supply Chain Configuration in the Projects Environment.” Production Planning & Control 33 (12): 1155–1172. no. November: doi:10.1080/09537287.2020.1853269.

- Salimian, Hamid, Mona Rashidirad, and Ebrahim Soltani. 2017. “The Management of Operations a Contingency View on the Impact of Supplier Development on Design and Conformance Quality Performance.” Production Planning & Control 28 (4): 310–320. doi:10.1080/09537287.2017.1282056.

- Salimian, Hamid, Mona Rashidirad, and Ebrahim Soltani. 2021. “Supplier Quality Management and Performance: The Effect of Supply Chain Oriented Culture.” Production Planning and Control 32 (11): 942–958. doi:10.1080/09537287.2020.1777478.

- Schoenherr, Tobias, and Morgan Swink. 2012. “Revisiting the Arcs of Integration: Cross-Validations and Extensions.” Journal of Operations Management 30 (1–2): 99–115. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2011.09.001.

- Shi, Yongjiang, and Mike Gregory. 1998. “International Manufacturing Networks—to Develop Global Competitive Capabilities.” Journal of Operations Management 16 (2–3): 195–214. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72532-1_13.

- Siggelkow, Nicolaj. 2007. “Persuasion with Case Studies.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (1): 20–24. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.24160882.

- Steinle, Claus, and Holger Schiele. 2008. “Limits to Global Sourcing? Strategic Consequences of Dependency on International Suppliers: Cluster Theory, Resource-Based View and Case Studies.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 14 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2008.01.001.

- Sun, Wenbin, and Jing Pang. 2017. “Service Quality and Global Competitiveness: Evidence from Global Service Firms.” Journal of Service Theory and Practice 27 (6): 1058–1080. doi:10.1108/JSTP-12-2016-0225.

- Yin, Robert K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

- Zhang, Yufeng, and Mike Gregory. 2011. “Managing Global Network Operations along the Engineering Value Chain.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 31 (7): 736–764. doi:10.1108/01443571111144832.

Appendix A.

Interview protocol

About the interviewee:

How long have you been with the project company?

What is your background?

What is your formal role in the project company?

What kind of tasks take up most of your work?

What categories are you involved with?

Percentages for each category?

Procurement strategy.

What do you see as the most important goals within [the global procurement department of the case company]?

How does this differ from the previous procurement strategy at the company?

Sourcing and supplier base management:

2. How is a supplier chosen for a product or project in your area?

What factors do you see as the most important for a ‘perfect’/optimal supplier?

What constitutes a preferred supplier?

What factors would you like to monitor on a supplier?

3. How are relationships with suppliers managed and monitored?

Based on formal performance monitoring? What KPIs are used, if so?

Based on more informal/personal factors to create trusting relationships? How is this implemented?

4. How are suppliers currently eliminated from [the case company’s] supplier base?

What reasons do you see for ending a relationship with a supplier?

Can you give some examples of discontinuing a supplier?