Abstract

This study evaluates how relationships, information characteristics, and supply chain information integration influence supply chain coordination and organizational performance in Bangladesh’s ready-made garment sector. Organizational performance includes operational performance and competitive performance. Data has been collected from 171 supplier-manufacturer dyads. Drawing on the coordination theory, this study theorizes that supply chain information integration and coordination can increase organizational performance. The structural equation modelling approach was used in data analysis. Generally, this study discloses that relationships and information characteristics positively influence supply chain information integration. Supply chain information integration directly influences supply chain coordination and competitive performance, whereas supply chain coordination is significantly related to operational and competitive performance. Moreover, supply chain coordination mediates the two relationships: supply chain information integration and operational performance and supply chain information integration and competitive performance. New insights are added by examining the relationships that connect the antecedents of supply chain information integration, supply chain information integration, and outcomes by looking at the focal manufacturing firm and its dyadic supplier partner separately. Separate examination in the dyad exhibits some identical and diverse outcomes. Furthermore, we suggest theoretical and practical implications for academics for theory building and managers.

1. Introduction

Due to the complex and dynamic business environment that firms operate in, there are huge pressures on cost, quality, and delivery issues that are, in turn, dependent on their supply chain (SC) partners’ ability to meet end customers’ requirements (Haleem et al. Citation2018). In such an environment, firms attempt to integrate their operations internally (cross-functional integration within the organization) and externally (integration with customers and suppliers) (Uddin and Akhter Citation2022), which is termed SC integration. SC integration in a complex business environment encompasses SC information integration and SC coordination with other partners (Tsanos, Zografos, and Harrison Citation2014). SC information integration is exchanging information through information systems within a company’s cross-functional areas and with other supply network partners to manage operational and related processes (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010; Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016). We deduce SC integration regarding the SC flows of information and physical and required coordination to manage them in the SC relationships. Information and physical integration are needed to create flawless operational processes and eliminate non-value-added activities within the SC. The integration of information flows between SC partners is defined as SC information integration, and the integration of physical flows is termed SC coordination (Tsanos, Zografos, and Harrison Citation2014). SC coordination deals with coordinating decision-making between SC partners on operational processes to ensure efficiency and effectiveness in SC management. Adopting such a process view of SC information integration can help integrate events in the supply network that often share sensitive information between SC partners to enhance superior organizational performance. Despite considerable past work on SC integration, we narrowly focus on SC information integration by examining its antecedents and influence on performance outcomes. Moreover, this study focuses on the less-studied context of Bangladesh’s ready-made garment industry. Also, the relationships that connect antecedents of SC information integration, SC information integration, and outcomes are examined separately by the focal manufacturing firm and its dyadic supplier partner. The level of integration, use of digital platforms, and coordination are not the same across the manufacturers and supplier firms. Manufacturers are in an advantageous position compared to suppliers concerning integration, digitalization, and coordination capabilities. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first papers to look at the dyadic influence of the role of SC information integration in the context of Bangladesh’s key ready-made garment sector.

According to the coordination theory, internal integrative systems, such as information integration and coordination, facilitate data exchange and cross-functional coordination. These systems develop the relatedness needed to integrate and exchange information among internal functions that extensively enhance the importance of information exchange and coordination. Internal integration and coordination are crucial integrative mechanisms for SC information integration and coordination, further improving organizational performance. SC information integration, exchange, and coordination are interconnected capabilities or resources in relationship-based strategic management literature (Briscoe and Rogan Citation2016; Castañer and Oliveira Citation2020; Malone and Crowston Citation1994). Thus, based on the coordination theory, we argue that pooling and managing resources or capabilities of a supply network comprise an evolving factor for the durable organizational performance of SC partners, compared to individual firms.

The context of ready-made garments is vital to understanding global supply chain integration issues. Bangladesh’s ready-made garment industry contributes significantly to its export earning potential. In 2021, this sector held a 6.80% share in the global export market, with a second position. In the fiscal year 2020–2021, the ready-made garment sector contributed 82% of Bangladesh’s total export earnings. The emerging and vibrant apparel sector requires proper planning, information integration, and coordination.

Ali, Rahman, and Frederico (Citation2021) argued for more integration and negotiation between buyers and suppliers in Bangladesh’s ready-made garment sector to minimize losses due to existing and new order cancellations during the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent McKinsey & Company Insights Report (2021) also emphasized that supply chain vertical integration and transparency in Bangladesh’s ready-made garment industry are crucial. In this report, Berg et al. (Citation2021) cite that Bangladeshi suppliers must invest in automation, information technology, digitization, and vertical integration to remain competitive in the global market. Otherwise, they will degrade in speed and competitiveness. Partly in response to this, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association plans to introduce a quick response code label on apparel items, where all the parties in the supply chain could be identifiable (BTJ Desk Report Citation2023). This attempt by the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association will accelerate information exchange among SC partners, transparency, and promote sustainability. These points are imperative for testing and validating theories encompassing SC integration and SC information integration in Bangladesh’s fast-growing ready-made garment industry.

SC information integration (through information exchange) is required to manage not only information flows but also SC coordination (through joint planning, execution, monitoring, and follow-up) (Tsanos, Zografos, and Harrison Citation2014). SC coordination is how a firm interacts and coordinates within its boundary and SC partners to ensure operational efficiency through product design, process monitoring, demand management, sales forecasting, operations, and resource planning (Tsanos and Zografos Citation2016). For instance, SC coordination can be enhanced through planning systems like FastReact (helps with specific integrated business planning for well-timed production of each supply chain step without delay) and electronic integration like SAP/Oracle (shares information and coordinates all the stages of SC) to cope with the agile supply chain needs. Under SC coordination, companies mutually allocate their resources at the functional levels to add value to participating SC companies (Fugate, Davis‐Sramek, and Goldsby Citation2009). Moreover, SC information integration deals with internal operating information by providing timely access to different functions in the company and sharing information between SC partners on a dynamic basis (Cai, Jun, and Yang Citation2010; Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016). Huo, Han, and Prajogo (Citation2016) investigated the association between SC resources, SC information integration, and firm performance, but the role of SC coordination was missing. Thus, from an SC information integration perspective, it is crucial to investigate mechanisms connecting SC coordination to operational performance and competitive performance outcomes (Fawcett et al. Citation2007; Rajaguru and Matanda Citation2019). Lower costs, high-quality products, effective order fulfillment, delivery, and customer complaints are indicators that comprise operational performance. Sales volume, market share, customer retention, and market strengths represent competitive performance.

Although prior SC literature has investigated the impact of SC information integration on firm performance and SC performance (Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016; Vafaei-Zadeh et al. Citation2020; Wei et al. Citation2020; Wong, Lai, and Bernroider Citation2015), few studies have addressed how SC information integration affects operational performance and competitive performance via SC coordination. Some researchers have proposed information characteristics and behavioural factors as antecedents that affect SC information integration (Tsanos and Zografos Citation2016). Similarly, the effect of SC information integration on competitive advantage and operational efficiency has also been reported (Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016). Against this backdrop, this study examines the mediating influence of SC coordination on the association between SC information integration and operational performance and between SC information integration and competitive performance. The absence of SC coordination may lead to poor SC performance, as evidenced by non-compliant products, poor delivery and lead time schedules, lack of customer focus, and low customer satisfaction (Kanda and Deshmukh Citation2008). Prior studies have also shown that firm performance can be enhanced through SC information integration, but how to attain competitive advantage via SC information integration was not explicitly examined (Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016; Wei et al. Citation2020). This study responds to calls for further research by Tsanos and Zografos (Citation2016) and Vafaei-Zadeh et al. (Citation2020) to examine the influence of relationship characteristics and information characteristics on SC information integration that have been under-studied in prior literature. This study also adheres to the research guidelines proposed by Huo, Han, and Prajogo (Citation2016). It probes the impact of SC information integration on competitive advantage, which is also a component of operational and competitive performance.

To summarize, this study has the following research intent: first, this study analyzes the influence of relational and information antecedent factors (relationship characteristics and information characteristics) on SC information integration. Second, this research examines the direct influence of SC information integration on operational and competitive performance and its indirect influence on operational and competitive performance via SC coordination. Accordingly, this study pursues the following research questions. (i) What are the antecedent factors that influence SC information integration? (ii) What is the association between antecedent factors, SC information integration, SC coordination, and operational and competitive performance? (iii) Does SC coordination mediate the association between SC information integration and competitive and operational performance? This study analyzed data collected from the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh to test these questions.

The rest of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the literature review, research gaps, and theoretical foundations of the study. Section 3 gives the development of hypotheses. The methodology and outcomes of the study are depicted next. Finally, the paper concludes by presenting the study’s implications, limitations, and scope for further research.

2. Review of related literature and theoretical development

2.1. Summarizing the related literature and identifying research gaps

The success of SC information integration has been reported to depend on factors like strategic information alignment, size of the firm in the SC (Harland et al. Citation2007), level of complexity in the product and market (Wong, Lai, and Bernroider Citation2015), environmental uncertainty (Wong, Lai, and Cheng Citation2011), and cultural differences (Vafaei-Zadeh et al. Citation2020). Other studies have linked relational factors to SC information integration as well (e.g. Tsanos, Zografos, and Harrison Citation2014; Tsanos and Zografos Citation2016; Wei, Wong, and Lai Citation2012; Wong et al. Citation2015), and some have included information/technical factors of SC information integration (Wei et al. Citation2020; Wong et al. Citation2015). Each firm in the SC needs to manage behavioural aspects as manifested by relationships and technological elements as manifested by information technologies. Relational and technical aspects should be considered simultaneously to improve performance outcomes; otherwise, their opposing effects could hamper advancement gains traced to SC information integration (Griffith and Dougherty Citation2001; Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016). To overcome these limitations, managing relationships and information characteristics among SC partners is necessary to enhance SC information integration.

Some scholars have investigated the relationship between SC information integration and firm performance or SC performance directly (e.g. Prajogo and Olhager Citation2012; Wei et al. Citation2020; Yu et al. Citation2018). They did not consider SC coordination issues like joint product design, joint planning, demand forecasting, capacity and inventory management, and after-sales support. However, some studies recommend that other aspects may moderate or mediate the association between SC information integration and firm performance (Wei et al. Citation2020; Wong, Lai, and Bernroider Citation2015; Yu et al. Citation2018). For example, Yu et al. (Citation2018) found flexibility dimensions, such as proactive flexibility and reactive flexibility, mediate the influence of SC information integration on organizational performance. Thus, SC coordination can bridge SC information integration and business performance, and this study proposes that SC coordination mediates the association between SC information integration and organizational performance.

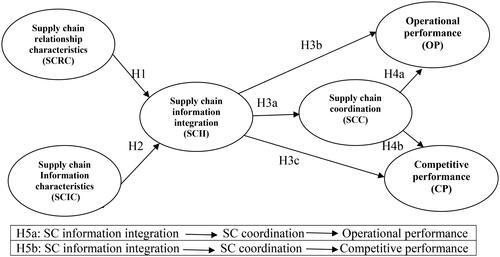

Many operations and SC management researchers have shown that SC information integration can provide several benefits (i.e. firm-level benefits and shared benefits) to SC members (Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016; Tsanos and Zografos Citation2016; Vafaei-Zadeh et al. Citation2020). Rajaguru and Matanda (Citation2013) assessed the inter-relationship among inter-organizational capabilities, inter-organizational information systems integration, and supply chain capabilities, but not their impact on performance. Tsanos, Zografos, and Harrison (Citation2014) provided a conceptual framework showing the association between behavioural factors, SC information integration, SC operational collaboration, and SC performance and suggested a further empirical study of those issues. This suggestion was also echoed by Huo, Han, and Prajogo (Citation2016), who specifically mentioned examining the association between internal and external information integration and the competitive performance of the firms in the SC. This study seeks to fill the underlying research gaps by taking note of these recommendations and using precepts from the coordination theory as the theoretical framework. The conceptual framework in this paper is shown in . In , detailed past studies are reported, leading to the research gaps that are addressed in this paper. The literature review () revealed the following three broad themes:

2.1.1. Theme 1: Diverse characteristics of integration

The concepts of relational/information characteristics of integration captured in the literature were quite diverse. They incorporated works capturing relational characteristics only (e.g. Cai, Jun, and Yang Citation2010; Tsanos, Zografos, and Harrison Citation2014; Tsanos and Zografos Citation2016) or information characteristics only (Vafaei-Zadeh et al. Citation2020; Wei et al. Citation2020). However, some works also included relational and information characteristics but not comprehensively (e.g. Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016; Prajogo and Olhager Citation2012; Rajaguru and Matanda Citation2013). Few studies did not consider either relational or information characteristics (Wei, Wong, and Lai Citation2012; Wong, Lai, and Bernroider Citation2015; Yu et al. Citation2018). Thus, relationship characteristics (e.g. trust, commitment, and compatibility) and information characteristics (e.g. information quality, information technology, and information security) are included to ensure the robustness of this research vis a vis coverage in prior literature.

2.1.2. Theme 2: Common integration dimensions that were studied

The most common integration dimensions that were examined in prior literature were SC integration and SC information integration. Other elements proposed as integration dimensions included inter-organizational integration and IT-enabled collaborative decision-making (Wong et al. Citation2015), Inter-organizational information systems integration, and SC capabilities (Rajaguru and Matanda Citation2013), Logistics integration (Prajogo and Olhager Citation2012), Logistics information integration, Inter-organizational trust, and Partner Cooperation (Wei, Wong, and Lai Citation2012) Information sharing, and Collaborative planning (Cai, Jun, and Yang Citation2010). However, other aspects that merit research (notably SC coordination/SC process coordination, which can play a crucial role in intensifying the information integration in an SC relationship) were not comprehensively evaluated. Thus, this investigation has considered SC coordination as a bridge between SC information integration and organizational performance.

2.1.3. Theme 3: Performance outcomes considered were diverse

Performance indicators in the extant domain were assessed differently. Some studies focused on SC performance (Tsanos, Zografos, and Harrison Citation2014; Tsanos and Zografos Citation2016; Yu et al. Citation2018), while some others emphasized firm-level performance (Prajogo and Olhager Citation2012; Vafaei-Zadeh et al. Citation2020; Wei et al. Citation2020). Financial performance and cost performance were also measured in some studies (Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016; Wong, Lai, and Bernroider Citation2015; Wong et al. Citation2015). Organizational performance is important in assessing firm-level performance in an SC instead of SC performance. Organizational performance is also an indicator of SC performance. Thus, this study decided to include organizational performance, providing operational and competitive performance. Few prior studies have examined competitive performance as part of organizational performance.

2.2. Supply chain information integration and coordination

SC information integration refers to the degree to which a firm shares operational, technical, and strategic information within its boundaries and across SC partners to manage organizational and SC activities (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010; Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016). It includes electronic collaboration, information technology, and information exchange. Firms exchange information through electronically connected information systems or other media, such as face-to-face, telephone, and fax (Cai, Jun, and Yang Citation2010). Typically, in inter-organizational information sharing, electronically connected information systems are used (Vafaei-Zadeh et al. Citation2020). SC information integration has two dimensions: internal and external information integration. Firms develop an integrated information system within their firm boundaries through internal information integration that helps in inter-functional information exchange (Rai, Patnayakuni, and Seth Citation2006). Hence, all internal functions are included in a database, and data are used for effective and efficient day-to-day operations (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010). Firms share information with their SC partners through external information integration to facilitate collaborative planning and strategic operational decisions (Prajogo and Olhager Citation2012).

SC coordination refers to how a firm coordinates operations within its cross-functional entities and across SC boundaries to attain operational supremacy. According to Treacy and Wiersema (Citation1993, 85), SC coordination is defined as ‘companies pursuing operational excellence by seeking ways to minimize costs, eliminate intermediate production steps, reduce transaction and other 'friction’ costs, and optimize business processes across functional and organizational boundaries’. It includes coordination of purchasing, production, sales, and delivery of products and services (Tsanos and Zografos Citation2016). SC partners jointly plan, coordinate, evaluate, and implement their organizational and SC operational decisions. SC coordination emphasizes physical, spatial, temporal, and economic issues of SC integration (Morash and Clinton Citation1998; Xiao and Jin Citation2011). This study operationalizes SC coordination, which is comprised of two dimensions: internal coordination and external coordination. Internal coordination emphasizes inter-functional coordination to ensure on-time delivery and meet customer requirements. External coordination focuses on joint resource allocation and full utilization of resources between SC partners to ensure operational efficiency.

In summary, SC integration refers to how a firm strategically integrates internal functions with its customers and suppliers. This study defines SC integration in a complex business environment encompassing SC information integration and SC coordination with other partners (Tsanos, Zografos, and Harrison Citation2014). SC information integration includes the exchange of information through an information system by a firm within its organizational functions and across SC partners to jointly manage organizational and SC processes (Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016). SC coordination is defined as the extent to which a firm coordinates within its administrative functions and across SC partners to ensure operational efficiency through product design, process monitoring, demand management, sales forecasting, operations, resource planning, etc. (Tsanos and Zografos Citation2016).

2.3. Coordination theory

Malone and Crowston (Citation1990, 361) have defined coordination as ‘the act of managing interdependencies between activities performed to achieve a goal’. Subsequently, other scholars have extended the definition of coordination as a pooling of resources, building capabilities, communication, and integration between partners (Briscoe and Rogan Citation2016; Hoetker and Mellewigt Citation2009; Vlaar, Van Den Bosch, and Volberda Citation2007). In the context of SC management, it is crucial to identify interdependent SC activities. Hence, coordination is a strategic response to the challenges of devising systems to manage those interdependent activities.

The coordination theory tackles the additional information processing performed when multiple connected actors pursue goals that a single actor pursuing the same goals would not perform (Malone Citation1988, 5). This theory states that firms should harmonize their SC partners to manage interdependent activities (Malone and Crowston Citation1994). Interdependent activities are categorized as (i) pooled interdependency, (ii) reciprocal interdependency, and (iii) temporal interdependency (Ahmed et al. Citation2020; Jayaram, Tan, and Nachiappan Citation2010; Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2012). Inter-organizational practices, such as SC information integration (as pooled interdependency) and SC coordination (as reciprocal and temporal interdependency) are coordinated by relationships and information exchange that exists among SC partners, and the strength of that coordination enhances organizational performance (Stekelorum et al. Citation2021; Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2012). Both internal and external integration and coordination require proper SC management. Internal and external coordination, preceded by a standardized information network and long-term relational bonding, enhances organizational performance and sustainability (Ahmed et al. Citation2020; Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2012).

Prior research has also applied the coordination theory to communicate the strategies to enhance organizational performance from internal and external polling of resources or capabilities and integration. For instance, Wilson and Platts (Citation2009) employed the constructs from coordination as a theory lens to elucidate the role of resource configuration on mixed flexibility requirements. Jayaram, Tan, and Nachiappan (Citation2010) also used the coordination theory to endorse the strong association between the scope of supply chain integration and supply chain management efforts. Goh and Eldridge (Citation2019) draw on coordination theory to investigate the effect of sales and operational planning on supply chain performance. Moreover, Ahmed et al. (Citation2020) used the coordination theory to assess the impact of supply chain partners’ environmental integration on a firm’s sustainability performance. Similarly, Stekelorum et al. (Citation2021) applied the coordination theory to examine the influence of internal and external green supply management practices on third-party logistics providers’ operational and financial performance.

To summarize, by relying on the precept of the coordination theory and the extant related literature, this study proposes and tests a holistic conceptual model () that theorizes a relationship between antecedents of SC information integration, SC information integration, SC coordination, and organizational performance. This study developed hypotheses from this conceptual framework and will discuss them in the next section.

3. Hypotheses development

3.1. Antecedents of supply chain information integration

According to the coordination theory, trust and commitment are represented by the characteristics of supply chain relationships that are crucial to managing the SC's interdependent efforts (Skipper et al. Citation2008). SC relationship characteristics are relational mechanisms that encourage firms to partner and attain competitive advantages in SC. Trust and commitment are two necessary components in SC relationships. A trusted relationship between SC partners leads to high-level SC information integration (Cai, Jun, and Yang Citation2010). Many firms do not want to share proprietary information with their SC partners unless they have trusting relationships (Moberg et al. Citation2002). Information sharing within organizational boundaries and across the SC is essential to accomplish state-of-the-earth SC tasks (Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016; Uddin, Fu, and Akhter Citation2020). In a trusted relationship, firms get access to high-quality and a more comprehensive range of information domains (Hung et al. Citation2011). By tapping into such high-quality and broader information, firms integrate and jointly plan demand, supply, and other operational decisions in the SC, enabling them to build successful internal information integration capabilities (Zsidisin et al. Citation2015). Commitment is another component of the SC relationship, wherein firms invest considerable efforts to maintain valuable relationships with their partners along the SC (Moberg et al. Citation2002; Tsanos and Zografos Citation2016). SC information integration requires simultaneous efforts from partners regarding resource dedication and allocation to the mutual relationship. Firms express willingness to gather and use information with those partners in the SC who are committed and trusted in their relationships to their joint advantage (Moberg et al. Citation2002). Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Supply chain relationship characteristics positively influence supply chain information integration.

H2: Supply chain information characteristics positively influence supply chain information integration.

3.2. Supply chain information integration, supply chain coordination, and organizational performance

According to the coordination theory, SC partnering firms require integrated mechanisms to attain competitive advantage and supremacy in performance (Briscoe and Rogan Citation2016; Malone and Crowston Citation1994). SC information integration is an integrated mechanism (representation of pooled interdependency) that can stimulate the coordination among SC partners in product design, procurement, material flows, sales forecasting, inventory management, and process monitoring (Prajogo and Olhager Citation2012; Setia, Sambamurthy, and Closs Citation2008; Soliman and Youssef Citation2001; Zaridis, Vlachos, and Bourlakis Citation2021). The coordination theory offers theoretical reasons as to why SC information integration not only facilitates operational and strategic information exchange in the SC but also plays a vital role in operational integration (as a mechanism) in dyadic relationships (Stekelorum et al. Citation2021; Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2012). SC information integration allows the firms to share strategic SC information and transactional information about procurement and order placing. Strategic SC information facilitates firms in coordinating strategic decisions regarding their operations, such as sales forecasting, inventory management, and delivery scheduling (Prajogo and Olhager Citation2012; Tsanos and Zografos Citation2016). Hence, strategic SC information requires intense communication and a trusting relationship between SC partners. Through SC information integration, firms share adequate and complex information that needs efficient operational integration with their SC partners. For effective SC coordination, firms need real-time SC information like sale forecasting, production planning, inventory level, and process monitoring (Gamme and Aschehoug Citation2014; Lehoux, D’Amours, and Langevin Citation2014; Zhao, Zhao, and Hou Citation2010). Hence, SC information integration helps firms align with their SC partners in coordinating their operational activities (Özcan, Coronado Mondragon, and Harindranath Citation2018). Furthermore, SC information integration provides high-quality, timely, and sufficient information to reduce geographical and time distances. Thus, the following hypothesis is predicted:

H3a: Supply chain information integration positively affects supply chain coordination.

H3b: Supply chain information integration positively affects operational performance.

H3c: Supply chain information integration positively affects competitive performance.

3.3. Supply chain coordination, operational performance, and competitive performance

The coordination theory explains that a firm can enhance operational capabilities through joint planning, implementation, and follow-up practices with its SC partners (Castañer and Oliveira Citation2020; Hoetker and Mellewigt Citation2009). SC coordination as reciprocal interdependency involves joint planning, execution, and monitoring practices that SC partners must do to enhance capabilities and competitive advantage. Hence, SC partners are responsible for planning, management, implementation, and performance evaluation (Min et al. Citation2005). SC coordination facilitates SC partners in mapping their outputs and orders, where digital technologies can play an important role (Yu et al. Citation2018). SC partners can address critical issues like SC disruption and overall operational expenses through SC coordination and attain operational supremacy (Zhang et al. Citation2010; Zhao et al. Citation2020). SC coordination ensures the involvement of manufacturers and suppliers in R&D activities and operational processes (Shou et al. Citation2021). Consequently, product and process design, development, and production processes can be changed to attain more standardized and high-quality products. In such a manner, SCs become more flexible and consistent. In sum, SC coordination’s inter-firm planning behaviours help SC members produce standardized and customized products that enhance their operational performance (Birasnav, Chaudhary, and Scillitoe Citation2019; Morash and Clinton Citation1998; Uddin Citation2022). Therefore, it is offered:

H4a: Supply chain coordination positively affects operational performance.

H4b: Supply chain coordination positively affects competitive performance.

3.4. Mediation effects

According to the coordination theory, SC information integration and SC coordination are considered managing devices that firms can use for capability development (Skipper et al. Citation2008; Stekelorum et al. Citation2021; Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2012). To enhance performance, firms should highly emphasize SC information integration and SC coordination (Goh and Eldridge Citation2022; Liu et al. Citation2013). SC information integration is firmly connected to coordination processes, implying that business processes should be coordinated and linked within firms’ internal and external boundaries (Cagliano, Caniato, and Spina Citation2006; Jayaram, Tan, and Nachiappan Citation2010). This argument suggests that SC information integration may support a firm in facilitating SC coordination with its SC partners and enhance capabilities, leading to organizational supremacy (Li et al. Citation2006). Hence, SC information exchange and integration are necessary to build coordination between SC partners (Prajogo and Olhager Citation2012; Sundram et al. Citation2018). More specifically, consistent information flow within a firm and in the SC ensures cross-functional coordination and joint decision-making. This can assist firms in implementing strategic decisions more effectively and efficiently, enhancing the possibility of attaining a competitive advantage. Sahin and Robinson (Citation2005) argued that the significant outcome of SC integration is achieved through SC coordination, while information exchange unbolts only a tiny fraction of the probable benefits related to SC information integration. IT and trust support SC information exchange, ultimately facilitating SC coordination and organizational performance (Vanpoucke, Vereecke, and Muylle Citation2017; Yu et al. Citation2018). SC information integration can enhance SC coordination and flexibility between SC partners, actively facilitating market change prediction and adjusting the operational processes before everything changes, thereby enhancing organizational performance (Khanuja and Jain Citation2022; Levi-Bliech et al. Citation2018). SC partners exchange their resources, operational plans, and procedures with each other through collaboration and improve their operational performance and competitive performance. The mediation effect of SC coordination indicates the importance of SC coordination to managers while making supply chain integration decisions. Thus, the role of SC coordination as a mediating variable means that even if a firm has outstanding SC integration and competition capabilities, SC coordination is indispensable for bridging such SC integration and competition capability to organizational performance enhancement (Wook Kim Citation2006). Therefore, the following hypotheses are predicted:

H5a: Supply chain information integration indirectly positively affects operational performance through supply chain coordination.

H5b: Supply chain information integration indirectly positively affects competitive performance through supply chain coordination.

4. Research methodology

4.1. Sample and data

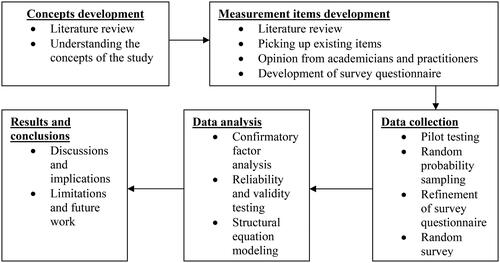

Data were collected from manufacturer-supplier dyads of the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh. All respondents held at least one managerial position in their respective firms (). The survey questionnaire was developed broadly in three steps. First, a detailed analysis of the relevant literature on those issues was conducted. In parallel, we confirmed the importance of SC relationship characteristics, SC information characteristics, SC information integration, SC coordination and operational performance, and competitive performance of these constructs by conducting a focus group interview of three Operations and Supply Chain Management academics. The importance and relevance of these issues to apparel supply chains in Bangladesh were discussed by interviewing four SC managers from four ready-made garment companies in Bangladesh. Second, a semi-structured questionnaire was constructed based on the outcomes of the previous stage. The semi-structured questionnaire includes closed-ended and open-ended questions. In this stage, 20 firms were randomly selected, and pilot testing of our research instrument was conducted. Pilot testing increases the clarity and understandability of the survey instrument. Hence, to facilitate understanding by the respondents, we defined the meaning of latent constructs at the top of the questionnaire. This step was crucial in encouraging respondents to recognize the meaning of the constructs in the questionnaire from a holistic perspective and in connection to their industry. Finally, the survey items were refined throughout this process, improving face validity, and a close-ended questionnaire using a seven-point Likert scale was finalized ().

Table 1. Demographics of valid samples.

From the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association general member list (total of 3,651), 900 ready-made garment manufacturers were selected randomly. The web link access to an electronic copy of the close-ended questionnaire was sent by e-mail. Of the 900 firms, 720 agreed to participate in the survey and to give contact details for a representative supplier. Hence, two criteria were set to mitigate supplier selection bias: (i) the length of the relationship with the supplier had to be a minimum of one year, and (ii) the supplier selected should deliver the highest procurement value to the manufacturer. Of the 720 firms that agreed to participate, only 273 manufacturing firms returned the filled-up questionnaire (response rate of 37.92%). Of these 273 responses, 14 were incomplete (without supplier contact information or insufficient response). Then, 259 corresponding suppliers were contacted; 227 of these firms agreed to participate in the survey, and the close-ended questionnaires were sent to them. A total of 180 questionnaires were returned from the suppliers (response rate 79.30%). After removing nine incomplete responses due to missing values, 171 paired responses were used for further analysis. The demographic details of the final sample are given in below.

4.2. Measurement

This study adapted the existing literature’s latent constructs and related observed variables. The required measurement items were obtained from existing literature, and creating a new set of item(s) was not pursued. The observed variables were purified by taking expert opinions from operations and supply chain academicians and managers. The observed items were also modified to suit our investigation perspective. After conducting pilot testing on 20 supply chain managers, the items were again refined (in necessary cases) to ensure face validity. A seven-point Likert scale was used to evaluate all the items (observed variables). On that scale, ‘1’ symbolizes ‘strongly disagree’, and ‘7’ symbolizes ‘strongly agree’. The latent constructs were operationalized by collating the corresponding responses to each observed variable.

4.2.1. Supply chain relationship characteristics

This construct exhibits the relational factors that encourage firms to actively join the SC information integration process. This study adapted the five items from Hung et al. (Citation2011) and Rajaguru and Matanda (Citation2019). These items measured the behavioural and compatible factors that influence SC information integration.

4.2.2. Supply chain information characteristics

This construct includes five items that measure information characteristics regarding information quality, information technology, and information security. This research adapted the five indicators from the study of Vafaei-Zadeh et al. (Citation2020).

4.2.3. Supply chain information integration

This construct revealed the extent of internal and external integration regarding information technology and information exchange between SC partners. Five items of this construct were adapted from Wong, Lai, and Bernroider (Citation2015) and Prajogo and Olhager (Citation2012).

4.2.4. Supply chain coordination

This construct revealed the extent of internal and external coordination and joint efforts between SC partners. Five items of this construct were adapted from Tsanos and Zografos (Citation2016).

4.2.5. Operational performance

We used four items in this contract, representing the degree of quality, delivery, and cost leadership through higher productivity, customer satisfaction, and flexibility. In addition, four items of this construct were adapted from the study of Rajaguru and Matanda (Citation2019).

4.2.6. Competitive performance

This construct measured a firm’s performance compared to its leading competitors in the primary industry. This study adapted four items of this contrast from the survey of Fawcett et al. (Citation2007).

4.3. Control variables

This study controlled for the firm’s size and the relationship’s duration. The duration of the relationship ensures heterogeneity of relationships among the supply chain partners. This variable indicates how long the firms in the supply network have been working with their partners. Longer duration in relationships means mutual trust, interdependency, and durability. This variable was measured through a three-range duration in the survey questionnaire (). This study assessed another control variable, ‘firm size’, through the number of personnel in the firm. Large firms, in terms of the number of personnel, indicate higher business volume with their supply network partners and enjoy more power in the supply network relationship. This study also considered ‘informants’ experience’ in the current position as a control variable. This variable was measured by providing the questionnaire with four options (1 to 3 years, 4 to 6 years, 7 to 10 years, and above 10 years). Highly experienced executives can deal with several issues in the supply network more efficiently than new or less professional staff. This variable was included to account for human effects that can influence the degree of relational and informational integration, SC coordination, operational performance, and competitive performance. This study also controls for industry type. Though all firms belong to the ready-made garment sector, manufacturing firms exercise more digital integration than supplier firms.

4.4. Nonresponse bias and common method bias

Two methods were used to mitigate against non-response bias. First, Armstrong and Overton (Citation1977) method was used. Since we spent four months (December 2022 to March 2023) on data collection, the vital information received in the data collection process was compared in the early respondents (first 10% of the received responses) and late respondents (last 10% of the received responses). Variances were assessed through a t-test analysis. It was exhibited by the results that variances concerning the number of employees and relationship duration were not significant at p ≤ 0.05. Second, ten paired responses were randomly picked, and two characteristics (i.e. current position and years in the current position) were compared with those of the ten paired responses from the initial sample. The results also showed that variances were insignificant at the p ≤ 0.05 level. Thus, non-response bias is not a significant threat in this study.

Two steps were followed to address common method bias. First, this study designed a questionnaire that is easily understandable to the informants. Endogenous and exogenous variables were separated. This research maintained strict confidentiality of the informants’ responses. Second, this research applied the marker variable method to assess the study’s common variance between the marker variable and latent variables () (Lindell and Whitney Citation2001). A marked variable is theoretically unrelated to any of the latent constructs of the study. This study treated ‘government support’ as a marker variable and adapted the scale (using a 7-point Likert-type) from Um and Oh (Citation2020). Results have shown no significant (<0.25; ) correlation between latent and marker variables. Thus, common method bias is a minor challenge in this study.

Table 2. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) results.

Table 3a. Correlations and (squared correlations) among the constructs—suppliers’ model.

5. Analysis and results

5.1. Measurement validation

Before testing hypotheses, this study tested the reliability, unidimensionality, and validity of all the unobserved constructs in the two models: (i) the suppliers’ model and (ii) the manufacturers’ model. First, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS software was conducted. CFA presents a comprehensive enumeration of the unobserved variables of a study (Uddin Citation2013). Consistent with Hair et al. (Citation2014), this study assessed goodness of fit (GOF) indexes of the suppliers’ model, and the acceptable indexes were: χ2 = 505.805; df = 324; p = .000; χ2/df = 1.561 (<3.0); RMSEA = .057 (<0.06); AGFI = .858; NFI = .901; CFI = .943; IFI = .944 (NFI, CFI and IFI is more significant than 0.90). Second, this research computed Cronbach’s α to check internal consistency; Cronbach’s α value ranged from 0.793 to 0.947, passed the suggested reference point of 0.70, and confirmed internal consistency. Third, we computed standardized factor loadings (SFLs), average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) to test for convergent validity. All standardized factor loadings were statistically significant [SFLs >0.50 are acceptable (Hair et al. Citation2014; Uddin and Rahman Citation2015)]. The standard threshold for average variance extracted is 0.50 (Hair et al. Citation2014). The AVE for each construct was higher than the threshold point. The composite reliability of each construct was more significant than the reference point of 0.70. Thus, SFLs, CR, and AVE support strong convergent validity (). Measurement items are shown in .

Again, we assessed GOF indexes of the manufacturers’ model, and the acceptable indexes were: χ2 = 500.813; df = 316; p = .000; χ2/df = 1.585 (<3.0); RMSEA = .059 (<0.06); AGFI = .895; NFI = .902; CFI = .958; IFI = .958 (NFI, CFI, and IFI is more significant than 0.90). The Cronbach’s α value ranged from 0.819 to 0.963, confirming internal consistency. All the SFLs were statistically substantial [SFLs >0.50 are acceptable (Hair et al. Citation2014)]. The AVE for each construct was higher than the threshold points of 0.50, and the CR of each construct was more significant than the reference point of 0.70. Thus, SFLs, CR, and AVE support the convergent validity of the manufacturers’ model ().

Finally, discriminant validity was evaluated by paralleling the squared correlation with the AVE for each construct. When discriminant validity is present, the AVE estimates for each pair of constructs are higher than the squared inter-construct (SIC) correlation between all pairs of constructs. As demonstrated in , the correlation matrix (significant at the p < 0.01 level) and SIC correlation coefficient met the requirements for discriminant validity. For instance, in the suppliers’ model (), in SC information integration, the AVE estimate was 0.743, and the SIC values for SC coordination, operational performance, and competitive performance were 0.144, 0.214, and 0.005, respectively, demonstrating discriminant validity. Again, in the manufacturers’ model (), in SC information integration, the AVE estimate was 0.794, and the SIC values for SC coordination, operational performance, and competitive performance were 0.201, 0.060, and 0.024, respectively, ensuring discriminant validity.

Table 3b. Correlations and (squared correlations) among the constructs—manufacturers’ model.

5.2. Hypotheses testing

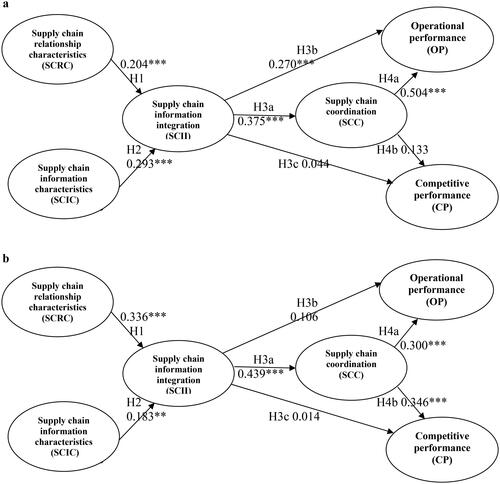

This study has assessed the overall association between supply chain relationship characteristics, supply chain information characteristics, supply chain information integration, supply chain coordination, operational performance, and competitive performance through a structural equation modelling approach. Hypotheses were tested in two separate models: (i) the suppliers’ model and (ii) the manufacturers’ model. The suppliers’ model exhibited acceptable GOF statistics: χ2 = 511.860; df = 329; p = .000; χ2/df = 1.556 (<3.0); RMSEA = .057 (<0.06); AGFI = .857; NFI = .902; CFI = .943; IFI = .944 (NFI, CFI, and IFI is more significant than 0.90). This study found that all hypotheses were accepted at the p < 0.05 and p < 0.001 levels, excluding H3c and H4b (, ). For SC information integration, which is driven by SC's relationship and information characteristics, the empirical results show that supply chain relationship characteristics and supply chain information characteristics predict the extent of SCII, thereby supporting H1 and H2. In SC information integration—SC coordination relationship, SC information integration facilities SC coordination, and supporting H3a. Again, for SCII-organizational performance relationships, SC information integration significantly affects operational performance and insignificantly affects competitive performance, supports H3b, and rejects H3c. In the association between SC coordination and organizational performance, SC coordination greatly influences competitive performance. Still, it does not significantly affect competitive performance, implying that H4a was supported, but H4b was not.

Figure 3. (a) Results of path analysis—suppliers’ model. (b) Results of path analysis—manufacturers’ model. Note: **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001

Table 4a. Results of hypotheses testing—suppliers’ model.

The manufacturers’ model exhibited acceptable GOF statistics: χ2 = 513.484; df = 322; p = .000; χ2/df = 1.595 (<3.0); RMSEA = .059 (<0.06); AGFI = .794; NFI = .901; CFI = .956; IFI = .957 (NFI, CFI, and IFI is more significant than 0.90). In that model, we found that all hypotheses were accepted at the p < 0.05 and p < 0.001 levels, excluding H3b and H3c (, ).

Table 4b. Results of hypotheses testing—manufacturers’ model.

This study applied the approach mentioned in Zhao, Lynch, and Chen (Citation2010) to assess the mediation role of SC coordination in the linkage between SC information integration and organizational performance dimensions (operational and competitive performance). This approach is simple to understand. Over specific structural paths, both direct and indirect effects were evaluated. The intervening effect of SC coordination on the linkage between SC information integration and organizational performance was projected by simultaneously depicting the direct and indirect structural lines in the structural equation modelling (Zhao, Lynch, and Chen Citation2010). In the suppliers’ model, the direct and significant influence of SC information integration (β = 0.375, p ≤ 0.001) on SC coordination and the influence of SC coordination (β = 0.504, p ≤ 0.001) on operational performance show the intervening (mediating) effect of SC coordination on the linkage between SC information integration and operational performance, supporting H5a. The indirect impact of SC information integration on operational performance was recognized to be positive and significant (βdirect = 0.270, p ≤ 0.001; βindirect = 0.189, p ≤ 0.001; βtotal = 0.459, p ≤ 0.001). The positive and significant effect (both direct and indirect) of SC information integration on operational performance exhibits a complementary mediation effect (). Again, the natural and significant impact of SC information integration (β = 0.375, p ≤ 0.001) on SC coordination and the insignificant influence of SC coordination (β = 0.133, ns) on competitive performance do not confirm the mediation role of SC coordination on the linkage between SC information integration and competitive performance, rejecting H5b.

Table 5a. Result of mediation effect test—suppliers’ model.

In the manufacturers’ model, the direct and significant impact of SC information integration (β = 0.439, p ≤ 0.001) on SC coordination and the significant effect of SC coordination (β = 0.300, p ≤ 0.001) on operational performance pageant mediation role of SC coordination on the linkage between SC information integration and operational performance, accepting H5a. We found the positive and significant indirect effect of SC information integration on the operational performance of SC information integration on competitive performance (βdirect = 0.106, ns; βindirect = 0.132, p ≤ 0.05; βtotal = 0.238, p ≤ 0.05), while the direct effect of SC information integration on competitive performance was also positive, but not significant. The significant indirect influence of SC coordination on the association between SC information integration and competitive performance shows only a mediation effect. Similarly, results show positive and significant indirect effects of SC information integration on competitive performance (βdirect = 0.014, ns; βindirect = 0.152, p ≤ 0.05; βtotal = 0.166, p ≤ 0.05), while the direct effect of SC information integration on competitive performance was also positive, but not significant. The significant indirect influence of SC coordination on the linkage between SC information integration and competitive performance also shows only the mediation effect, accepting H5b ().

Table 5b. Result of mediation effect test—manufacturers’ model.

5.3. Robustness checks

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was executed to validate the effectiveness of structural equation modelling. Their results validated the main findings of structural equation modelling analysis. The results of this study confirmed the robustness of applying numerous methods to lessen concerns regarding common method bias (marker variable test, survey instrument design), non-response bias (statistical t-test), and measurement errors. Additionally, this research has conducted some complementary tests to confirm that the study’s main findings are impartial and free from possible mistakes, ensuring the robustness of the study. First, we arbitrarily picked a 40% sample and executed structural equation modelling; the outcomes were the same as the study’s primary outcomes. Second, we have chosen operational performance as the dependent variable and other constructs (e.g. SC relationship characteristics, SC information characteristics, SC information integration, SC coordination, and competitive performance) as independent variables in the suppliers’ model. Then, we performed regression analysis; the results supported the original structural equation modelling analysis results. Finally, in the manufacturers’ model, we conducted regression analyses on the SC relationship characteristics, SC information characteristics, SC information integration, SC coordination, and competitive performance as predicted variables and then their interactivities as the predictor variables. The outcomes also supported the outcomes of the original structural equation modelling analysis. For further robustness check, in Appendix (A3), the outcomes of a short, structured interview with two executives from supplier and manufacturing firms were presented.

6. Discussion

The current study assessed the influence of supply chain relationship characteristics and supply chain information characteristics on SC information integration in suppliers’ models and manufacturers’ models. Firms develop SC information integration to attain operational performance and competitive performance objectives through SC coordination. We have conducted an empirical investigation to assess the proposed hypotheses based on data collected via a questionnaire survey from Bangladesh’s ready-made garment sector.

In general, the outcomes of this research show that supply chain relationship characteristics and supply chain information characteristics positively impact firms’ SC information integration initiatives in both models. These results signify that SC's relational and information characteristics should be considered simultaneously for SC information integration. Thus, firms should build relational connections with their SC members to enhance their integration level. At the same time, information characteristics (e.g. accuracy, security, and standardization) are equally crucial for them for developing SC information integration. Since operational supremacy is imperative in SC integration, firms must coordinate operational avenues meticulously with their SC partners that facilitate them in joint planning, resource allocation, and customer dealings. In short, positive SC relational and information characteristics in SC management facilitate the development of SC information integration, where firms can accomplish their long-term organizational performance goals.

First, our results show that SC relationship characteristics and SC information characteristics are positively linked to SC information integration. This result follows the coordination theory, which posits that relational and technological characteristics represent temporal and pooled interdependency to nurture SC information integration and SC coordination (Jayaram, Tan, and Nachiappan Citation2010; Skipper et al. Citation2008). Thus, this research has direct contributions and implications for the coordination theory by describing how relational and technological characteristics amplify the impact of SC information integration and SC coordination on organizational performance. Moreover, these results are consistent with prior studies, where the authors argued that trust and information technology-based SC relationships are crucial for SC integration and SC coordination (Hung et al. Citation2011; Qin and Fan Citation2016; Vafaei-Zadeh et al. Citation2020; Zsidisin et al. Citation2015).

Second, this research adds to the SC integration literature by addressing the need for empirical investigation of vertical information integration on firm performance, especially in the ready-made garment sector in Bangladesh (Berg et al. Citation2021; Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016). This study examines the impact of SC information integration and SC coordination on organizational performance in the supplier-manufacturer dyads and thus complements the area of current literature. This study found that SC information integration facilitates SC partners to get benefits from SC coordination. The results state that SC information integration positively and significantly influences SC coordination in suppliers’ and manufacturers’ models. This result is similar to Prajogo and Olhager (Citation2012) and Tsanos and Zografos (Citation2016). So, to ensure operational supremacy, firms should nurture their coordinating efforts supported by information integration in the SCs. Moreover, this study found that SC information integration positively influences firms’ operational performance. Thus, relational and technology-attributed SC information integration can determine the operational performance of the firms of that SC. This result is also consistent with the conclusions drawn by Huo, Han, and Prajogo (Citation2016) and Vafaei-Zadeh et al. (Citation2020). We draw on the coordination theory and emphasize the significance of SC information integration and SC coordination in enhancing two dimensions of organizational performance (operational and competitive performance). These findings are primarily distinctive and reveal the significance of SC integrative mechanisms and coordination in attaining competitive advantage.

Third, the results show that SC coordination is positively associated with organizational performance. This result also follows the coordination theory, which states that cross-functional coordination within a firm and coordination with SC partners represent reciprocal interdependency that enhances capabilities of joint planning and operations, leading to operational supremacy (Castañer and Oliveira Citation2020; Jayaram, Tan, and Nachiappan Citation2010). Thus, this study directly contributes to the coordination theory by explaining how internal and external coordination can enhance organizational performance. Moreover, these findings are similar to prior studies, where the authors argued that SC coordination is vital for improving firm performance (Huo, Han, and Prajogo Citation2016; Vafaei-Zadeh et al. Citation2020).

The results have shown some similarities and dissimilarities in the case of suppliers’ models and manufacturers’ models. First, we analyzed the influence of relational and information antecedent factors (relationship and information characteristics) on SC information integration. In that case, results showed the significant positive impact of relationship characteristics (trust, commitment, and compatibility) and information characteristics (information quality, information technology, and information security) on SC information integration in both models, supporting H1 and H2. It implies that both models have theoretical and empirical validity and ensure robustness in SC information integration antecedent factors. Second, we have examined the influence of SC information integration on SC coordination, operational performance, and competitive performance. In the relationship between SC information integration and SC coordination, the suppliers’ and manufacturers’ models responded similarly; i.e. we found a significant positive impact of SC information integration on SC coordination, supporting H3a. These results also evidenced that the structural path between SC information integration and SC coordination was correct and sound. In the relationship between SC information integration and operational performance, the results exhibited a positive and significant linkage between SC information integration and operational performance in the suppliers’ model, supporting H3b. In contrast, the manufacturers’ model showed a positive but insignificant association between SC information integration and operational performance, not supporting H3b. This diverse result of the manufacturers’ model in the same relationship could be because of the influence of other factors like SC capabilities, logistics integration, etc., along with SC information integration. Again, in the SC information integration and competitive performance relationship, the results presented a positive but insignificant association between SC information integration and competitive performance in both models, thereby not supporting H3c. These findings indicate that other influencing factors (e.g. SC efficiency, lean processes, SC process integration, etc.) other than SC information integration are involved that can influence competitive performance significantly.

In the SC coordination and operational performance relationship, the suppliers’ and manufacturers’ models have shown a positive and significant impact of SC coordination on operational performance, supporting H4a. These results confirmed that the linkage between SC coordination and operational performance was correct and profound. In the SC coordination and competitive performance association, we found a positive but insignificant linkage between SC coordination and competitive performance in the suppliers’ model, not supporting H4b. In contrast, the manufacturers’ model showed a positive and significant association between SC coordination and competitive performance, supporting H4b. This distinct result of the supplier’s model in the same relationship could be because of the influence of other factors like SC flexibility, customer service, etc., along with SC coordination. This study has examined the mediation role of SC coordination on the linkage between SC information integration and operational performance, as well as SC information integration and competitive performance. The mediation role of SC coordination in the linkage between SC information integration and operational performance was confirmed in both models, supporting H5a. These outcomes signified that SC coordination is intervening in the SC information integration and operational performance relationship. In that case, suppliers’ models are more advantageous because the direct linkage between SC information integration and operational performance was significant. In contrast, the manufacturers’ model indicated SC information integration’s direct but insignificant influence on operational performance. We also found that the mediating role of SC coordination in the association between SC information integration and competitive performance is significant in the manufacturers’ model, supporting H5b, but not in the suppliers’ model, thereby not supporting H5b. These results indicated the superiority of the manufacturers’ model (though there was no significant direct linkage between SC information integration and competitive performance in both models) over the suppliers’ model. Our findings also depict how SC coordination mediates the impact of SC information integration on organizational performance. This signifies that firms should focus on joint operational issues like demand forecasting, planning, manufacturing, inventory management, and delivery to enhance their overall organizational performance.

6.1. Research implications

6.1.1. Theoretical implications

This study contributes to the SC management literature by structuring on prior theoretical and empirical works of SC integration. The empirical assessment of the suggested framework exhibits that this study further outspreads the SC management literature. We extend SC management literature by recognizing and confirming relationship and information characteristics’ roles in facilitating SC information integration. This, consequently, signifies the significance of relational and information attributes for SC information integration among the SC partners. This study has presented a comprehensive model incorporating relationship characteristics, information characteristics, SC information integration, SC coordination, and organizational performance.

This research contributes to the SC management literature by explaining how relationship and technological characteristics facilitate building SC information integration. No prior study has investigated the impact of relationship and technological characteristics in one model. We draw on the coordination theory and examine their effects on SC information integration as relationship, and technological characteristics represent temporal and pooled interdependency to attain competitive advantage. The results show that relationship and technological characteristics have a significant positive impact on SC information integration. Therefore, this study provides evidence of why firms should identify specific relational and technological factors when integrating with SC partners to ensure operational and competitive supremacy.

Furthermore, this study extends the pertinence of the coordination theory. SC information integration and SC coordination are treated as managing devices of interdependency in the SC relationship (Stekelorum et al. Citation2021; Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2012). SC information integration and SC coordination are comprehensive approaches for collaboration in information exchange and coordination, ultimately enhancing the competitive edge of partnering firms in the SC. As our results indicate a positive association between SC integration, SC coordination, and firms’ competitiveness, this study contributes to the coordination theory and SC management literature.

Academic scholars may extend our findings in further studies in the ready-made garment sector or similar branches of studies. Considering the similarities and dissimilarities between the suppliers’ and manufacturers’ models is important. Both models exhibited that relationship and information characteristics are equally crucial for SC information integration. Therefore, to theorize SC integration or SC collaboration, academics must simultaneously consider behavioural and technological aspects as antecedent factors. While building theory on SC integration, academics must recognize SC coordination as a crucial outcome, as both models have validated this relationship. Concerning performance dimensions, outcomes of SC integration, including operational and competitive performance, should be considered.

SC coordination is another crucial component in the manufacturer-supplier relationship. Performance indications can be outcomes of SC coordination. In that case, academics must recognize operational performance as an important outcome, as our suppliers’ and manufacturers’ models validated this assertion jointly. They can think about other performance indicators, such as competitive performance, sustainable performance, customer performance, innovation performance, etc. SC coordination can be considered a direct inflecting element and mediator in an SC integration and performance relationship depicting model.

6.1.2. Managerial implications

Given its theoretical contribution, this study is very important to SC managers for several reasons. First, it shows both models’ significant positive impact on relationship and information characteristics on SC information integration. This similarity in both models implies that managers in Bangladesh’s ready-made garment sector are very concerned about behavioural and technological issues in their SC relationships. We recommend that managers set rules and standards to codify, retrieve, and store data in the data management system. They must ensure information quality, information technology, and information security.

Second, this study presents a significant positive impact of SC information integration on SC coordination in the suppliers’ and manufacturers’ models. Hence, managers emphasized information exchange internally and externally through standardized electronic media (e.g. intranet, internet). At the same time, they (especially manufacturers) were involved in joint planning and execution of operational processes with their SC partners through electronic integration and other planning software like FastReact. Suppliers use mobile phones, email, and social media like WhatsApp for information integration. However, in many cases, software-based integration was absent; the reasons could be a single product line and a small business size (cost constraints) (please see Appendix—A3). Suppliers thought operational performance was an immediate outcome, as the suppliers’ model exhibited a positive and significant linkage between SC information integration and operational performance. Manufacturers have different opinions regarding operational performance as the immediate performance outcome of SC information integration. They might think that operational performance can be attained efficiently without other facilitating factors like SC capabilities, SC agility, or SC responsiveness. Additionally, managers (suppliers and manufacturers) have jointly denied considering competitive performance as an immediate outcome of SC information integration. They may think about other factors along with SC information integration. We propose that managers invest resources in building information exchange support systems (e.g. data integration, enterprise resource planning, and integrative inventory management systems). Firms should arrange training programs for managers to use these information systems. There should be specific rules and regulations to facilitate recording, storing, and retrieving information, such as experience sharing, group discussion, and upward suggestions from lower and mid-level employees.

Third, the suppliers’ and manufacturers’ model managers have indicated a positive and significant impact of SC coordination on operational performance. They believe that when joint planning and operational processes are implemented properly in the SC, low-cost and standard products can be produced, and lead time and delivery schedule can be maintained. Similarly, managers in manufacturing firms believe that sales volume, market share, and customer retention can be increased through efficient coordination with SC partners. Supplier firms’ managers have differing opinions about whether competitive performance can be enhanced through SC coordination and other factors. Finally, managers also emphasized the intervening role of SC coordination in the relationship between SC information integration and operational performance. They have given higher importance to SC coordination because operational performance enhancement is impossible without efficient and effective coordination. Even managers in manufacturing firms have emphasized SC coordination for competitive performance enhancement more than SC information integration. Thus, this study suggests that managers should set up regular coordination meeting schedules with their SC partners regarding planning, execution, and monitoring of strategic issues to respond to market reactions.

Furthermore, this study’s holistic model suggests that SC managers will make situation-based decisions. For instance, managers can perceive, reconfigure, and implement coordination strategies to reap the advantages of information integration in the SC. Finally, given that SC coordination bridges SC information integration and organizational performance, we recommend that firms emphasize integration and coordination with their SC partners in joint efforts ranging from demand forecasting to on-time delivery and after-sales support.

6.1.3. Policy implications

Decision-makers should consider the results of this study for policy formulation and implementation. Specifically, the Bangladesh Garments Manufacturers and Exporters Association, Bangladesh Textile Mills Association, and Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association can play a crucial role in this aspect. They can jointly consider the results of this study. As per suppliers and manufacturers, model, relational, and information, antecedent factors are crucial for SC information integration; decision-makers and trade associations can facilitate creating a trusted atmosphere in the ready-made garment sector through information exchange and credible and benevolent initiatives between SC members. For information integration, IT-enabled infrastructure is highly required. In that case, ready-made garment associations can help to develop and implement hardware and software and maintain the quality and security of information.

Suppliers and manufacturers have both emphasized SC coordination between SC partners. Global SC requires more automation and digitalization. For effective and efficient electronic coordination in the SC, intranet, and internet services, planning software, production tracking software, and enterprise resource planning software must be ensured, especially for firms that do not have complete or updated such facilities. Trade associations may also encourage and train SC members about software usage, maintenance, information sharing, and perspective benefits and limitations.

Though Suppliers and manufacturers in the ready-made garment industry believe that their performance indicators are in a good position, especially indicators of operational performance, this industry will have to face huge competition globally. High-quality, defect-free products should be produced in the domestic and global markets for performance enhancement. Efficient logistics support is needed to maintain lead time and delivery schedule. Decision-makers must focus on updated machinery, a trained and skilled workforce, higher vertical integration among supply chain partners, and efficient logistics services. They must ensure a secure and positive working atmosphere, as people do not want to repeat the Rana Plaza tragedy.

Bangladesh is in a key phase of its economic transition. The government should strengthen support and supervision in promoting the ready-made garment sector in Bangladesh. Financial, technical, and infrastructural support, especially in technology and coordination aspects, are very much needed. The government can develop special funds and authorities to provide financial support, supervise information networks, and coordinate efforts in ready-made garment SCs in Bangladesh. The study’s findings uncover that developing countries like Bangladesh have plenty of opportunities to connect to ready-made garment SC partners through information integration and coordination, resulting in enhanced performance.

6.2. Conclusions and limitations

This paper confirmed the association between SC relationships and information characteristics, SC information integration, SC coordination, and organizational performance from the SC management perspective in Bangladesh’s ready-made garment sector. First, it is abundantly evident from the outcomes that SC relationship and information characteristics and SC information integration are positively correlated. Second, our results exhibit a positive impact of SC information integration on SC coordination and organizational performance. Results also demonstrate that SC coordination has a significant direct effect on performance. The mediating function of SC coordination in the link between SC information integration and organizational performance was positive and significant. In short, we concluded that SC's relationship and information characteristics strengthen SC's information integration to enhance operational performance and competitive performance through SC coordination.