ABSTRACT

Community action for sustainability is a promising site of socio-technical innovation. Here we test the applicability of co-evolutionary niche theories of innovation diffusion (strategic niche management, SNM) to the context of ‘grassroots innovations’ (GIs). We present new empirical findings from an international study of 12 community currency niches (such as Local Exchange Trading Schemes, time banks, and local currencies). These are parallel systems of exchange, designed to operate alongside mainstream money, meeting additional sustainability needs. Our findings confirm SNM predictions that niche-level activity correlates with diffusion success, but we highlight additional or confounding factors, and how niche theories might be adapted to better fit civil society innovations. In so doing, we develop a model of GI niche diffusion which extends existing work and tailors it to this specific context. The paper concludes with a series of theoretically informed recommendations for practitioners and policy-makers to support the development and potential of GIs.

1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to contribute to a better understanding of how innovative solutions for sustainability developed in civil society can be harnessed and diffused more widely. Community action for sustainability is an often-overlooked, yet potentially promising site of socio-technical innovation. These ‘grassroots innovations’ (GIs) are formed in response to unsustainable mainstream systems, and aim to build and promote alternative systems of provision to enable more sustainable forms of production and consumption. We adopt a co-evolutionary understanding of socio-technical innovation which conceives of radical niches as potential sources of new ideas and solutions. Sustainability transitions literature examines the role of such niches in contributing to systemic change; strategic niche management (SNM) seeks to identify the conditions required for niches to successfully diffuse their ideas and practices into wider society. Until now, however, civil society niches have not been systematically studied, and the implications of their specific characteristics have not been adequately explored.

In this paper, we empirically test the applicability of these concepts to civil society niches. We study the field of community currencies (CCs) such as Local Exchange Trading Schemes (LETS), time banks, and local currencies: parallel systems of exchange, designed to operate alongside mainstream money, meeting additional sustainability needs. From an international study of 12 successful national project clusters (niches), we identify the niche activities, contextual factors, and socio-technical characteristics of the innovation itself, which are most strongly associated with successful diffusion. We highlight where SNM successfully explains patterns of diffusion, and where additional or confounding factors are evident. We reflect on how niche literature accommodates the realities of regime-crossing, social movement-based initiatives, and how SNM might be adapted to better fit civil society innovations. In so doing, we aim to contribute to a model of GI niche diffusion. We conclude with a series of theoretically informed recommendations for practitioners and policy-makers to support the development and potential of GIs, and discuss the implications for further research.

2. Theoretical context

2.1. Sustainability transitions and radical green niches

Over the last two decades a growing field of research has examined how to achieve transitions towards sustainability in the socio-technical systems which underpin the everyday activities of advanced industrial societies (such as the provision of food, energy, and transport). The term ‘socio-technical’ indicates that these systems consist not only of technological infrastructure, but also of social institutions and knowledge(s), and that these two aspects co-evolve. A transition is a fundamental shift in a socio-technical system, reflecting significant changes across a range of domains: technological, political, institutional, cultural, etc. Such a shift is required, it is argued, because incumbent systems are ‘locked-in’ to unsustainable trajectories by a set of dominant structures, institutions, and practices characterised in the literature as a ‘regime’. A transition can therefore be understood as a shift from one stabilised regime to another. The sustainability transitions field addresses the challenge of understanding and potentially influencing such transitions (Grin, Rotmans, and Schot Citation2010; Smith, Voss, and Grin Citation2010).

A common element in this literature is a focus on ‘niches’ as the loci of promising (but marginal) socio-technical radical green innovation. Niches are ‘spaces which shield experimental projects with radical innovations from too harsh selection pressures from incumbent regimes’ (Raven Citation2012, 126). The multilevel perspective (MLP) on socio-technical systems seeks to theorise and explain the dynamic relationships between radical innovative niches and incumbent regimes (i.e. dominant systems) (Geels Citation2002; Smith, Voss, and Grin Citation2010). A third analytical ‘level’ – landscape – represents broader, longer term changes which apply pressure to regimes, creating opportunities for niche innovations to offer solutions, diffuse widely, and potentially influence or even displace the regime. These levels (niche, regime, and landscape) are conceived as a nested hierarchy of degrees of stability or structuration, with the niche the least stable and the landscape the most. Historical studies adopting the MLP demonstrate how the accumulation and consolidation of niche experiments, combined with unfolding dynamics within regimes and landscape can, over time, lead to niches scaling-up and replacing incumbent regimes (Geels Citation2002, Citation2005).

2.2. Strategic niche management

The MLP is built on earlier work within sustainability transitions, including SNM which stressed the importance of intentionally created niches to protect and nurture emerging sustainable innovations (Kemp, Schot, and Hoogma Citation1998). Consequently SNM focuses on the factors which support successful niche development. Raven (Citation2012) outlines six important features of this literature, discussed in turn below, which form the backbone of our empirical analysis.

The first three are key niche-building processes identified in early SNM studies (Kemp, Schot, and Hoogma Citation1998). First, niche development is supported when visions and expectations are widely shared and are robust, tangible, and specific. Second, networking is necessary to establish a constituency around the innovation which provides resources, and engages other stakeholders in niche development (Schot and Geels Citation2008). Third, shared learning aids niche development when it involves both first-order learning (for instrumental performance gains) and second-order learning (radically reframing the innovation or the problems it addresses). SNM indicated that these three niche-internal processes were necessary (but not sufficient) for diffusion. Niche growth would occur when robust niche performance was combined with good compatibility with existing regimes (Smith Citation2007).

However, there was initially a lack of clarity over what exactly constituted a niche: a single project or a cluster? Thus, Raven's (Citation2012) fourth key feature of the SNM literature is the analytical distinction between local experiments and a more abstract ‘global’ niche level. The global niche is an emerging institutional field (or ‘proto-regime’) where a number of knowledge aggregation activities occur:

standardisation, codification, model building, formulation of best practice, etc. Also circulation of knowledge and actors is important … conferences, workshops, technical journals, proceedings, newsletters play a role too. (Geels and Raven Citation2006, 378)

Niches therefore comprise intermediary organisations and actors. These serve as ‘global carriers’ of best practice, develop standards, consolidate and institutionalise learning, and mobilise resources through networking and lobbying. Niches are emergent from, informed by, and in turn inform, local projects/experiments (Geels and Raven Citation2006).

Fifth, regime and landscape dynamics are critical in developing successful niches, both in initially prompting activists to experiment, and from regime destabilisation offering opportunities for niche solutions to be more widely adopted (Geels and Schot Citation2007). Landscape pressures or regime ‘crises’ can be a necessary precursor for niche innovations to gain influence, and interactions between the landscape, regime, niche, and projects explain how niches become coherent and powerful, or fail to establish themselves (Raven Citation2012). Sixth, vital niche protection serves three purposes: shielding from external pressures, nurturing innovation development, and empowerment to transform regime systems (Smith and Raven Citation2012).

From these theoretical foundations, the literature describes five stages of niche development (Raven Citation2012):

regime and landscape dynamics inform experimentation through the creation of new expectations and social networks;

emerging local networks experiment with novel socio-technical configurations and learn how to make them work within a specific context;

participants exchange knowledge with other actors and lessons get translated into more generic rules that become applicable in different locations;

the emerging institutional field becomes a useful resource for subsequent experiments in new locations;

when sustained sufficiently over time, such cycles result in a stable institutional field which may start to influence prevailing regimes, or become a viable competing socio-technical configuration.

This literature predicts that niches which exhibit the key internal niche-development processes, and which experience favourable external conditions in regimes and landscapes, should be able to diffuse their innovative solutions into wider society, influencing or even displacing regimes.

Influential niches diffuse their innovative ideas and practices along three potential routes. First, scaling-up sees individual projects recruit more participants and grow in size, activity, or impact. Second, project replication in new locations or contexts multiplies the number of participants and scale of innovative activity overall. Third, partial elements of niche ideas are translated into mainstream contexts to address regime crises, gaining influence but commonly losing much of their radical ethos (Smith Citation2007; Seyfang Citation2009). Our empirical analysis assesses innovation diffusion along each of these three routes.

2.3. Grassroots innovations

SNM has primarily addressed market-based innovations in technological systems, and there has been relatively little work to date examining how applicable these theories are to radical innovations emerging from civil society. GIs are defined as:

innovative networks of activists and organisations that lead bottom-up solutions for sustainable development; solutions that respond to the local situation and the interests and values of the communities involved. In contrast to the greening of mainstream business, grassroots initiatives tend to operate in civil society arenas and involve committed activists who experiment with social innovations as well as using greener technologies and techniques. (Seyfang and Smith Citation2007, 585)

By extending niche innovation analyses into civil society contexts, Seyfang and Smith (Citation2007) argue that community action is a promising but neglected site of systems-changing innovation for sustainability. GIs differ from conventional market-based innovation: they are driven by ideological commitment rather than profit seeking; the protected space is created by values and culture (as opposed to regulation or subsidies); and they tend to involve communal ownership structures and operate in the social economy, often relying on voluntary labour, grants, or mutual exchange. These alternative systems of provision are intended to meet social needs in a way that differs significantly from the dominant regime, whilst also facilitating the expression of green values and cultural preferences (Seyfang Citation2009).

Researchers have begun to explore the nature of GIs and the conditions under which they emerge (see Verheul and Vergragt Citation1995; Georg Citation1999; Hess Citation2007; Smith Citation2007; Seyfang Citation2009; Witkamp, Raven, and Royakkers Citation2011; Kirwan et al. Citation2013; Ornetzeder and Rohracher Citation2013; Smith and Seyfang Citation2013; White and Stirling Citation2013). Yet there has been little exploration of the processes of niche formation and growth in civil society contexts, nor of the ways GI niches seek to gain wider influence on regimes (Smith Citation2007; Longhurst Citation2012; Hargreaves et al. Citation2013; Seyfang and Longhurst Citation2013b; Smith et al. Citationforthcoming are rare exceptions). Previous research indicates that ‘internal’ networking between projects in the UK's Transition Towns movement is as important as ‘external’ networking with wider social actors (Seyfang and Haxeltine Citation2012), and that a community energy niche can grow even with a lack of systematic shared learning (Seyfang et al. Citation2014) but fully understanding GIs and their potential requires more work. We therefore seek to address this knowledge deficit by asking: How well does SNM explain the development of civil society-led GI niches? How can theory inform more successful diffusion? And how does SNM need to attend to the distinctive characteristics of GIs?

3. Community currencies (CCs) as grassroots innovations (GIs)

CCs are parallel exchange mechanisms designed to exist alongside conventional money, meeting needs that mainstream money neglects. Throughout history there have been many examples of such parallel currencies, from Victorian utopian socialist Robert Owen's Labour Notes to Depression era stamp scrip. The current growth in CCs began with isolated experiments in the 1970s, followed by the diffusion of key ‘types’ through primarily green economics networks and movements since the mid-1980s (Douthwaite Citation1996). There are presently many thousands of CC projects worldwide (Seyfang and Longhurst Citation2013b). Some of these use paper currency notes to facilitate trading goods and services between individuals, others use electronic accounting systems and have brokers pairing requests with offers of help, and still others are supported by local governments or non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as tools to promote recycling or public transport.

Whilst historical CCs focused on economic imperatives, many recent CCs are geared towards sustainable development, through a range of social, economic, and environmental objectives (Seyfang and Longhurst Citation2013a). Social goals include building networks and social capital, rewarding and enhancing civic participation, and enabling social inclusion and cohesion; additionally, participants benefit personally from feeling valued and acknowledged for their contributions to social reproduction, even when formal employment markets might not value their skills (e.g. domestic labour, childcare, and neighbourly support). Economic goals include promoting stronger local economies, giving people and businesses a tool and an incentive to trade with local rather than global actors and thereby keeping money circulating locally, tackling financial leakage, and increasing the local economic multiplier. Users can also access interest-free credit and informal employment opportunities. Environmental goals relate to both structure and usage: first, as a non-interest-bearing financial system, CCs counter the debt-based money system and growth-oriented capitalist economy which drives environmental degradation; second, by promoting more localised economies, shorter supply chains can reduce transport costs and pollution; third, they bring producers and consumers together, allowing the impacts of consumption to become more visible; fourth, they can promote asset sharing (reducing individualised consumption); and fifth as specialised incentive mechanisms, they can promote consumption of ethical and low-impact goods and services (Seyfang and Longhurst Citation2013a).

These recent experiments have emerged principally from civil society; consequently, they are interesting contemporary examples of GIs attempting to develop new socio-technical systems from the bottom-up. Our previous analysis of CCs identified that although many have common ideological and social movement origins, they have different goals and mechanisms – hence they are conceptually and materially distinctive sub-niches. We distinguish four different CC types (Seyfang and Longhurst Citation2013a), and this distinction is another analytical axis in our empirical study.

Local Currencies: Paper-based (note) currencies (exchangeable for national currency) that circulate within a specific locality, for example, the UK's Bristol Pound. These tend to focus primarily on economic development objectives and keeping money circulating locally; whilst informed by the green critique of money and often instigated by radical environmentalists, the more recent examples are increasingly well marketed to a mainstream audience, professionalised, and are adopting electronic payment systems for convenience and efficiency.

Mutual Exchange: Currencies that are created by a group of users as a form of mutual credit and are issued through the act of exchange. LETS are the most common example; members list the goods and services they wish to offer, and others contact them to request a trade – units of local currency are transferred from the buyer's account to the seller's; no interest is charged or paid, and negative and positive accounts should equal out overall. These types are most successful at building community spirit and social capital, and are typically run by volunteers.

Service Credits: Time-based currencies used to reward neighbourly activity and build social capital; these are normally run by institutions such as health, education, or community development partnerships, and aim to meet users' social and economic needs, and nurture civic engagement in areas of social fragmentation and disadvantage. The most common are Time Dollars in the USA and UK Time Banks; they typically require funding to employ project workers.

Barter Markets: These allow participants to exchange goods and services at a specific event/site without use of mainstream money. Participants trade with a special market currency, which circulates on the day enabling a high volume of transactions. The most famous is the Argentinean Redes de Trueques, which expanded rapidly during a period of financial instability in the late 1990s, meeting the needs of a mainstream newly impoverished middle class; current examples are led by green activists aiming to promote sharing, reuse, and waste prevention.

Our earlier work has identified how CCs travel between countries, evolving across space and time, and that internal niche-development processes occur at multiple, nested, levels (e.g. local, national, and international), and in parallel for the four CC types (Seyfang and Longhurst Citation2013a, Citation2013b). Whilst recognising the significance of these multiple levels in understanding wider CC niche development, we found the most significant niche-development processes were occurring at the national level, within CC types. Thus, here we examine a sample of 12 diverse national CC niches, to empirically test whether SNM's niche-development processes are occurring, and how this correlates with diffusion success.

4. Methodology

Informed by this previous work, our unit of analysis is the national CC niche, for example, Time Banks in the USA. These comprise at least five CC projects of a particular type within a country, and intermediary networks sharing learning and best practice, developing the ‘sector’ on behalf of local projects, lobbying for support, etc. An international scoping study identified 39 national CC niches (some countries had more than one, e.g. the UK has Time Banks, LETS, and Transition Currency niches). Europe had the greatest number of CC niches (19), followed by North America (9), Asia (4), South America (3), Australasia (2), and Africa (1) (Seyfang and Longhurst Citation2013a).

Evidence was gathered primarily from CC websites and documents, and elite informants (practitioners and intermediary actors with global expertise and perspective), and the quantity and quality of data available for each niche varied enormously. Consequently only about half of the 39 niches were likely to offer sufficient data for further exploration of the factors contributing to their successful diffusion. Of those, 12 were purposively sampled for diversity of CC type, geography, and maturity. We wished to include examples of all four currency types, in all possible continents, and to include older and newer iterations of types where possible. shows the spread of cases selected for diversity, and provides a summary of their key features.

Table 1. National currency niches (age in years).

Table 2. Summary of CC niches.

Each national niche was investigated using a mixed-method case study approach: reviewing previous literature and research (including grey literature); reviewing CC networks and projects' own publications and websites; elite interviews with national niche intermediary actors and leading activists; and reviews of relevant national policy developments. Where information was not available in English, online tools were used to translate websites and translators were hired to interpret documents and conduct email interviews on our behalf.Footnote1 Analysis followed standard qualitative techniques, using theoretically informed codes (top-level codes included networking, learning, expectations, regime, landscape, actors, translation, replication, scaling-up, etc.), whilst being open to unexpected factors becoming salient in the investigation of what contributes to niche diffusion. Case study dossiers averaging 9500 words were compiled, varying from 14,500 words (the longest-running case with the most evidence) to just 4000 (the most recently established case).

An analytical framework was developed to allow cross-case comparison drawing on the rich case study material to derive metrics for two key variables: ‘niche activity’ and ‘diffusion success’. Niche activity was quantified using a scoring system based around learning, networking, and shared expectations with context-specific sub-indicators comprising the kinds of activities that might meet those objectives (). Each sub-indicator was individually scored with zero points for none/no evidence, and either 1, 2, or 3 depending on the extent of activity found. Aggregated, these provided a score for each dimension of niche activity, as well as a composite total (which measures aggregated niche activity over the case's lifetime, rather than at a specific point in time).

Table 3. Metrics of niche activity.

A similar process was used to develop a metric for ‘diffusion success’. A threefold ranking system was developed for each of the three diffusion routes: replication, scaling-up and translation (). Replication was scored according to our best estimate of the total current number of active projects in the niche (assumed to be the peak to date). Two exceptions are the Argentinian Trueque and UK LETS, with peaks and cut-offs of 2001 and 2000, respectively. As the purpose of this particular paper is to explore the conditions supporting niche diffusion, the reasons for these declines are not investigated here – see Gómez (Citation2012) and Aldridge and Patterson (Citation2002) for more information.

Table 4. Metrics of diffusion success.

Scaling-up was scored according to the number of users of the largest known project within the niche. There was no data for two cases (Banco del Tiempo and Brazilian Community Banks), which were therefore given the lowest score, as there was no evidence that any project had scaled beyond 200 users. Translation was the most difficult diffusion route to quantify, requiring a qualitative assessment of the extent and nature of diffusion into different types of institution, actor groups, contexts, etc., sometimes away from the origins of the CC project. For this metric, we have simply indicated whether translation has occurred, and if so, whether or not it is widespread.

We also coded the niches according to a number of other relevant factors which emerged from our reading of the literature: the external policy context; the attitude of niche actors to the regime they were responding to, and to the state, and whether they were involved in lobbying for supportive change; the national network's form, and whether they are proactive in establishing new projects. We undertook a great many exploratory analyses, sub-dividing the cases according to these factors and seeking patterns in the data. Finally, we investigated the CC niches' internal strengths and weaknesses, and external challenges and opportunities to complement the niche analysis. We present here only what we consider to be the most important analyses and key findings.

5. Findings: What factors contribute to niche diffusion?

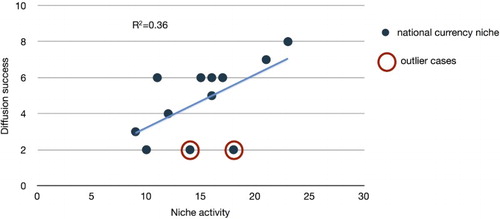

We begin by testing SNM's central prediction that niches which demonstrate learning, networking, and establishing shared expectations will be more effective (in the right contexts) at diffusing their innovations. We test this empirically by correlating scores for niche activity and diffusion success across our 12 cases (). Scoring for niche activity varied between 9 and 23, with a mean of 15. (Of the 17 types of niche activity examined, only 1 was universally evident, indicating that CC niche-development activities are unevenly distributed and somewhat ad hoc.) Scores for diffusion success varied between 2 and 8, averaging 4.75. shows a correlation between the two scores (R2 = 0.36), indicating that the two phenomena are linked, and confirming SNM's predictions in the CC context, and potentially GIs more generally. This is a significant finding, and the first such quantified analysis of GI niche diffusion and activity.

Table 5: Niche Activity and Diffusion Success Scores for 12 National Currency Niches

Looking more closely at the data, there are two significant outliers (highlighted): Troc Tes Trucs and Brazilian Community Banks. Both have relatively high scores for niche activity but low diffusion scores. These are the only niches which exhibited a ‘managed replication’ strategy (see Section 5.1) which increases the niche activity score whilst simultaneously decreasing potential diffusion. Furthermore, there is no data on Brazilian Community Banks projects’ scale so its diffusion score may be underestimated. If one accepts that these two niches are somewhat anomalous, and they are excluded from the calculation, there is a much higher R2 value (0.73), indicating a strong correlation and confirming the theoretical prediction. This is not necessarily a causal relationship, however, and theory suggests an iterative and mutually supportive relationship between niche-building activities and the diffusion of new projects (Schot and Geels Citation2008).

Examining the data more closely reveals which specific aspects of CC niche activities were most correlated with diffusion success. The R2 correlation is strongest for Internal networking (0.72), followed by Learning (0.37), with a weak score for External networking (0.16), and no correlation at all with Expectations (0.00). This finding counters the proposition that niche activities are all equally important in contributing to diffusion – there is good evidence that for CCs, intra-niche networking is far more significant than other activities, and we discuss below why this might be.

There also appears to be a link between who establishes projects within a niche, and their diffusion success. The mean diffusion score for activist-established systems is 5.1 compared to 3.5 for NGO-led projects. This may be because activist-led CCs are less tightly managed than NGO-led projects (even with a proactive replication strategy) and can draw on supporters' and volunteers' efforts to drive diffusion.

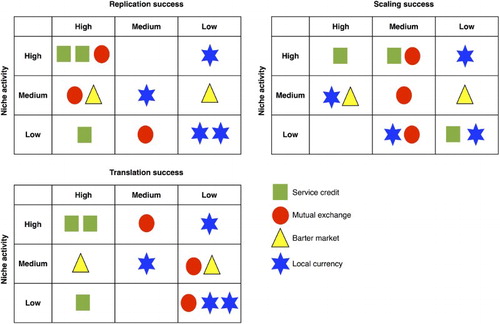

This test provides a useful overview of the overall correlation, but has limitations. Perhaps the most significant is that niches with the highest aggregate diffusion score have demonstrated all three routes of replication, scaling, and translation. This clearly is ‘diffusion success’ but an innovation does not have to follow all three routes. A niche which followed only one of the routes, but did so exceptionally well, would score lower diffusion success overall. We therefore go on to examine the factors contributing to diffusion success along each of the three routes in turn. shows graphical representations of these data plotted into a matrix (with niche activity scores ranked and grouped into ‘high, medium, and low’ categories comprising four cases each), for each diffusion route. The following sections discuss each in detail.

Figure 2. Matrices showing success along three diffusion routes versus niche activity, by currency type.

5.1. Replication

The matrix of CC replication success versus niche activity () reveals that half the niches demonstrated a high degree of diffusion via this route, the most prominent of the three. It is striking that 5 of the 12 niches are situated at either extreme of the matrix, that is, high niche activity and high replication, or alternatively low niche activity and low replication. The niche activity we found does indeed involve many activities which make replication easier, for example, training, developing handbooks, and national conferences. This confirms SNM's predictions that more niche activity is linked with a greater proliferation of projects and vice versa.

However, the distribution of cases across the matrix indicates that it is not a straightforward relationship – niche activities may support replication, but are not a pre-requisite. High levels of replication can occur without extensive niche activity and vice versa. To explain this, we must examine the different types of CC more closely. None of the Local Currencies had achieved high levels of replication, whereas the Service Credits had all done so and the Mutual Exchanges all displayed medium or high replication. Two possible reasons for this difference relate to the nature of the projects (and the innovations) themselves. First, Mutual Exchanges and Service Credits are relatively ‘low-tech’ (being analogous to volunteering rewards or gift vouchers, and requiring only a computer to set up), whereas Local Currencies emulate conventional money and adopt more professional technology and payment systems. Second, Local Currencies require a wider range of participants in order to function well, for example, businesses and local government. This involves significant recruitment effort and negotiation to manage the expectations of all parties (Longhurst Citation2012). In contrast, Mutual Exchanges and Service Credits can be established amongst much smaller group of citizens, making their replication more straightforward and accessible.

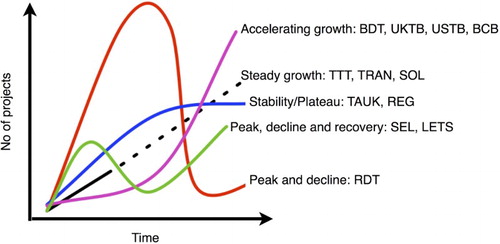

We found several replication trajectories amongst the niches over time (), indicating that niche diffusion by replication is not a linear process. Linearity can be observed in some cases (especially early on, e.g. UK Transition Currencies) but rates of growth can vary at different points in a niche's lifetime (e.g. three Service Credit niches currently exhibit accelerating growth). Several niches have experienced a pattern of peak-and-decline, most significantly the Argentinian Trueque. There is no doubt this was the most widespread of our CC niches and is almost certainly the most widely diffused contemporary CC of all, particularly in terms of replication and scaling. However, following extremely rapid and uncontrolled growth, it suffered a catastrophic collapse in confidence and subsequent fall in numbers from which it has never recovered (see Section 5.4). Some Mutual Exchange niches also show a fall in project numbers over time, followed by a resurgence, depicted in as ‘peak-and-recovery’ (e.g. French SEL). Finally, a few niches appear to have plateaued, for example, Regiogeld exhibits a severe slowdown in the rate of new projects emerging. Rather than this indicating a stable population of consolidated projects, a common experience in CCs is that the number of new projects emerging roughly equals those closing down. This underlying ‘churn’ of projects coming in and out of existence is not adequately captured by snapshot measures of total project numbers, but can be very significant. Lasker, Collom, and Kyriacou's (Citation2011) survey of US Time Banks found that 55% of projects were less than two years old, and a further 32% were formed 3–5 years ago. In this case, replication is extremely successful – but maintaining projects beyond their first few years is more problematic. Both the high rate of project churn and the variability of replication trajectories point to this route being a non-linear path to niche growth and diffusion.

An interesting trend is the subset of accelerating growth replication exhibited by the three Service Credit niches since 2008. This has been driven by a more grassroots diffusion of time banks, particularly in the USA and UK (the data are less clear in Spain). Collom, Lasker, and Kyriacou (Citation2012) describe three different models of time bank: standalone community-based; embedded with open membership; and embedded with closed membership. Niche theories propose that, over time, civil society-based niche activity will evolve towards translation (embedding) as mainstream actors adopt (embed) the innovation. However, this recent growth appears to be amongst the community-based projects (i.e. moving away from mainstreaming), possibly as a response to recent global economic crises, and also as time banks are adopted by social movements extending their repertoires of action. This suggests that the trajectory varies not only in terms of the rate of growth but also the direction. Indeed, CC niches can grow in more than one ‘direction' simultaneously, particularly those, such as Service Credits, which are adept at translation (see Section 5.3).

Finally, we identified three modes of CC niche replication. Reactive replication (six of our 12 niches) involves projects being established by activists without needing any permission or instigation from niche-level actors; if a national body exists, it tends to comprise projects offering mutual support. Proactive replication (four niches) sees a national body, or other intermediaries, actively working to seed and establish new projects, alongside bottom-up activist-led projects emerging without permission. Finally, with managed replication (two niches) only those given permission can establish new projects, involving a contractual or accreditation process that must be negotiated with niche-level bodies. charts replication success for these three different modes. Unsurprisingly, managed replication shows the least, reflecting a concerted effort to control the process. Contrastingly, reactive and proactive strategies are much more successful – whilst these reflect different kinds of niche process, both support high replication.

5.2. Scaling

Scaling of CCs involves projects expanding to engage more participants or users. Our quantified data do not suggest a very strong relationship between niche activity and scaling success (), and few patterns are evident. We note that the largest projects within all of the Mutual Exchange niches were between 201 and 1000 users, unlike the other three CC types, which all displayed at least one niche containing a project with over 1000 participants. We suggest two reasons for this. First, Mutual Exchanges are based on personal interactions and reciprocity, and may not grow beyond the point where members feel a sense of community. Second, CC usage can dwindle as social capital amongst participants increases and members trade with each other informally, which clearly problematises the process of measuring CC ‘success’.

In general, though, the data reveal that high scaling-up can be better explained by a combination of internal and external factors. Our niches indicate that the most significant internal strength of successful projects is having sufficient resources. Social economy initiatives like CCs struggle to develop business models that provide a regular stream of income. However, the largest showcase projects within our niches did have a stable resource base: some, such as the Chiemgauer (the largest German Regiogeld project), have started to generate income and have both volunteer and paid staff; others, such as the Talente Tauschkreiss Voralburg, have semi-volunteers, part paid in the currency; the largest time banks are of the ‘institutional’ variety, benefiting from the resources of both the host organisation and their existing clientele. The most commonly reported internal weakness (cited in almost all our niches) was struggling to attract participants and recruit people to use the currency, a fairly universal problem amongst CCs. This is perhaps unsurprising. CCs are radical experimental innovations – potential users might be wary, and require reassurance that their needs can be met. CCs must then fulfil users’ performance expectations to retain their participation, and sometimes emerging, enthusiastic – but oversold – projects fail to meet users’ expectations (Longhurst Citation2012).

External factors play a significant role in determining the extent of CC diffusion by scaling. The wider sociocultural context of the project was the most significant external success factor. For example, the largest UK LETS projects were located in areas where there was a high density of green, post-materialist middle-class members (Aldridge and Patterson Citation2002). Similarly the Chiemgauer's success is at least partly due to its Bavarian context where local civic pride is a strong motivating factor driving usage. The biggest external threats to project scaling were related to political issues: difficulties working with public authorities, which activists can find slow and frustrating; electoral and funding cycles rendering legitimacy and supportive measures vulnerable to change; and legal issues which arise as most CCs operate in legal grey areas, ignored by authorities who see them as irrelevant, but with a constant threat of future regulatory or punitive action. There are few examples of positive legislative steps to support CC development (the autonomous community of Galicia in Spain is one, although state support was revoked following a change in government).

In summary, scaling does not seem to have a significant link with CC niche activity at the national level, and instead relates to a combination of project-level internal and external factors. However, in most of our national niches, there are only one or two very large projects and many smaller ones. For example, the Chiemgauer dwarfs all other Regiogeld projects and there are very few others that have reached critical mass. This raises questions about how easy it is to both replicate and scale CCs.

5.3. Translation

Successful diffusion by translation requires the CC niche innovation (or elements of it) to be taken up and adopted by new types of actors, in new contexts. Examples from this study include community-based Time Banks in the USA being incorporated into youth court, health care and education systems. Translation is the least common of the 3 diffusion routes and only half our 12 niches showed any evidence of translation. shows cases clustering in the translation matrix's top-left and bottom-right corners, suggesting a correlation between niche activity and translation success. Service Credits are clearly the most successful at translation, as the model is adaptable to a range of contexts and actors – an intended function of the innovation itself. Most Local Currencies and Mutual Exchanges, and all Barter Markets show no translation at all.

A CC niche innovation's ability to be translated into mainstream settings is related to the regime which the CC is trying to influence or change. Identifying the relevant regime for each CC type was not straightforward. In many cases CCs seek complementarity, that is, they are not seeking to ‘overthrow’ or ‘displace’ an incumbent regime but are instead trying to build parallel infrastructure, or seed reforms within the existing regime. By clarifying the problem our 12 CC niches address, we identify 3 relevant regimes ().

The monetary system is the narrowest of these three regimes, addressed by two Local Currency niches: those that are most explicitly attempting to create alternative forms of local money and provide a substitute general-purpose money for use in everyday transactions. Here, the innovation itself is intended as a more sustainable substitute for conventional debt-based money which is seen as dysfunctional. A second set of CCs (various types but including all the Mutual Exchange niches) are addressing the mainstream economy. They are informed by the above monetary critique, but instead offer new forms of special-purpose money or micro-economy. In these, exchange takes place under different rules (e.g. equal labour value) and participants can construct their livelihoods at least partly outside the mainstream economy. The third regime is consumer society, and here CCs challenge the structures and values of consumer society itself. All Service Credit niches subscribe to this broader ambition to stimulate a wider change in society towards reciprocity, non-materialism, and an appreciation of value outside the market.

In another analysis, these regimes might be categorised as ‘landscapes’, the slow-moving background context within which regimes operate, and we acknowledge that the distinction is not clear-cut in this instance (we return to this in our conclusions). Within SNM the regime is often defined as the market which acts as a selection environment for new innovations, within an overarching industrial structure (Smith and Raven Citation2012). In the case of GIs such as CCs these categories may not be as relevant or applicable. However, the sustainability transitions literature broadly accepts that regimes are ‘nested’, and the same argument could be applied in this case. For example, the monetary regime is part of the economic regime which in turn is part of consumer society. Thus Local Currency projects, if successful, will impact on both the economy and wider society (this may be desired by the protagonists). However, if the immediate intention is to provide an alternative to mainstream money, this narrower regime target prevents translation into new contexts. Alternatively, Service Credits offer a tool flexible enough to be applied in health, education, justice, environmental, social, cultural, institutional, community and business contexts, and can thereby influence society in general. Here adaptability is built in, so translation is much easier to achieve into multiple regimes simultaneously. We conclude that whilst niche activity appears to have some relevance for predicting translation success, breadth of regime has greater influence.

5.4. Regime context

The regime context can influence niche growth and diffusion, when destabilising crises open up windows of opportunity for niches to proliferate, for example, the recent expansion in Service Credits as a response to economic austerity. The most striking instance of this is the Argentinian Trueque Barter Markets which were the most successful example of CC diffusion in terms of scale, between 1995 and 2001. Exact numbers of users and ‘nodos’ (Barter Markets) are unknown, but several sources suggest that in excess of 300 nodos were in operation with between 2.5 and 6 million users (Gómez Citation2012). This rapid expansion and diffusion success is at least in part due to regime destabilisation, if the wider economy itself can be characterised as a regime. The period from 1976 to 1991 saw an expansion of national debt and high inflation, followed by wage freezes and a reduction in state expenditure leading to severe unemployment. The Trueque was created in this context (Powell Citation2002). During its early years the economic conditions slightly improved, but a new crisis erupted in 1999. At the core of this crisis was a revaluation in the US dollar stimulated by wider turmoil in Latin American economies. This damaged the Argentinian economy's competitiveness and caused a rapid expansion in unemployment and poverty as well as political turmoil. Barter Markets expanded rapidly, with some support from both regional and central government. The middle classes were hit hardest by the economic crisis and were the core CC users (Powell Citation2002). There was also a widespread familiarity with the idea of alternative forms of money: many regional governments had a history of issuing their own bonds and currency, and continued to do so during the 1999–2002 crisis (Pearson Citation2003). Both these factors facilitated the growth of the Trueque during this period.

Regime contexts can exhibit positive impacts on niche diffusion, by proactively supporting and nurturing a niche's development. We classified policy contexts as either ‘supportive’ (referring to explicit governmental support) or ‘unsupportive’ (where there was evidence of either hostility or simply ignorance). For both niche activity and diffusion success, a supportive policy context was associated with scores 35% higher than in an unsupportive policy context (diffusion success 5.4 compared to 4.0; niche activity 17.8 compared to 13.3). This indicates that policy support can lead to a vibrant niche forming (e.g. through a flow of resources that supports niche-development activities) which is linked with greater diffusion success, confirming the predictions of niche theories.

6. Conclusions

This paper aims to identify the determining factors of GI niche diffusion, so as to better understand how to harness the creative forces driving innovative solutions for sustainability in civil society. It presents a novel quantified analysis to assess how well SNM explains the empirical evidence of a set of 12 CC niches and their diffusion experiences. Our aim is to contribute to an emerging body of knowledge about GIs for sustainability and their characteristics, scope, and potential for influencing wider systems.

We find some evidence of correlation between niches conducting key niche-development activities, and innovation diffusion success, which supports SNM (with such a small sample, this is not statistically significant). However, these activities are not equally important in predicting innovation diffusion. Internal project-to-project networking is the niche activity most strongly linked to diffusion success. In contrast, shared learning and expectation management appear to be relatively unimportant, and many niches have diffused widely with little evidence of consolidated and shared formal learning. This finding contradicts SNM's predictions, and runs counter to much accepted wisdom on the requirements of innovative niches to diffuse.

Why might this be the case? Our quantification methodology may have underplayed the role of these two types of activities, but it seems more likely that CCs' nature and characteristics are substantively different to previously studied innovations. Perhaps their rootedness in social movements and related repertoires of action mean they diffuse by sheer force of activist will, and their reasonable diffusion success is in spite of (not because of) a lack of systematic learning and expectation management. If this is so, then the question remains: How successful could these niches be if they attended more consistently to niche-development activities? Further research (and in particular, longitudinal intervention evaluations) is needed to fully assess these more detailed assessments of what is required to diffuse CCs. There was also a non-linear and varying set of diffusion trajectories, suggesting that the niche literature's linear progression of niche formation is oversimplified for this type of innovation. Peaks, troughs, recoveries, crashes, and plateaus are all in evidence as the CC niches respond to internal conditions and wider external factors. More theoretical work is required to fully account for the complexity of GI diffusion patterns.

The four CC types displayed varying diffusion successes, some of which could be explained by their socio-technical configurations. Replication was the most common diffusion route amongst CC niches, though not necessarily correlated with niche activity. Instead, we argue this is explained by the nature of the GIs themselves: they are primarily low-tech, and designed to be empowering and accessible to civil society groups wanting to experiment, therefore easy to transfer to new locations. Activist-led projects with looser central control spread most effectively. Diffusion via scaling-up existing projects appears to be only weakly linked to niche activity. Internal resource constraints and external sociopolitical and cultural factors were stronger influences on the ability of projects to grow and recruit more participants, as were features of the innovation itself (in terms of meeting users' expectations). Diffusion by translating innovations to new contexts was related to niche activity, which is to be expected; however, it was perhaps more influenced by the scope of the regime the niche responded to (and hence, the value-driven character of GIs). Service Credits were the most successful CC type; they address consumer society as a whole, and this regime-crossing breadth allows it to be appropriated into many different contexts.

Finally, we found strong evidence that wider regime and sociopolitical contexts were also significant in determining diffusion success. Favourable policy contexts and regime destabilisations were linked to wider diffusion, again confirming niche theory's predictions. Many of these contextual factors point to a hitherto understudied geography of GIs. In terms of patterns and trajectories of niche diffusion: place matters, and it can matter in a number of ways, from the influence of physical landscape and topographical features, to the clustering of populations with sociocultural values who are more or less predisposed to new ideas (see, for instance, Coenen, Benneworth, and Truffer Citation2012). Further work is necessary to understand how geography influences niche diffusion.

The intrinsic nature of GIs raises additional issues for SNM and niche theories. The complex multi-regime systems which many of these CCs address go beyond the single-technology-single-regime frameworks of much of the niche literature. Most of these niches do not intend to replace the regime, but rather to influence it, or sit alongside it. And some of the regimes are perhaps more like landscapes (i.e. consumer culture), raising questions about the extent to which the regime and landscape can be analytically separated. Thus, whilst some elements of SNM explain CCs' diffusion quite well, other parts are less successful at dealing with GIs. Adapting regime and niche concepts to non-market, value-driven innovative contexts demands attention; or perhaps alternative conceptual frameworks might be better suited to understanding how GIs can influence systemic change.

In keeping with the wider literature on niche development, our research clearly highlights that diffusion success is dependent on a number of factors and it is beyond the control of any given actor (or set of actors) to simply ensure that these elements are aligned. However, that does not mean that currency innovators are without influence at all. National intermediaries which perform ‘global niche’ functions seem a necessary foundation for extensive replication of projects. To harness the innovative efforts of communities for sustainable development, SNM suggests these bodies should focus their attention on internal networking initially, then direct efforts towards systematic shared learning, collective visioning and expectation-management and outward-facing networking, to achieve diffusion success beyond an initial growth spurt. Such actions may achieve levels of CC diffusion previously unseen. Of course, resources are the principal constraint, but policy measures to nurture intermediary niche-level organisations which support on-the-ground projects could achieve a step change in GI diffusion.

But it is also clear that CC developers face three key tensions when attempting to diffuse their innovations. The first is between control and diffusion. Niches with a managed diffusion strategy were better able to negotiate shared expectations around their projects, maintain confidence, and prevent damaging political tensions over the purpose and direction of the CC. However, this mode of management clearly slows down the rate of replication. A second tension relates to the technological sophistication of the CC. Simpler currencies are easier to replicate but potentially more difficult to integrate into everyday life to replace other forms of exchange and transaction. A third tension, common to many GIs, between engaging with mainstream actors and regimes, and maintaining autonomy, has clear implications for a niche's diffusion strategy.

GIs have a role to play in the transition to sustainability, but these initiatives cannot be expected to do it all on their own – to achieve sustained and wider influence, they do need support both at project and niche level, and in the wider regulatory and sociopolitical context. Given such conditions, it is reasonable to assume this untapped innovative capacity might flourish and grow.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Gill Seyfang is Reader in Sustainable Consumption at the University of East Anglia. She leads a programme of research on ‘GIs’ for sustainability within the 3S (Science, Society and Sustainability) Research Group, in the School of Environmental Sciences. She is the author of The New Economics of Sustainable Consumption: Seeds of Change (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009) and is co-editor of the International Journal of Community Currency Research.

Noel Longhurst is a Senior Research Associate at the University of East Anglia where he is a member of the Science, Society and Sustainability (3S) Research Group. His work focuses on socio-technical change with a particular focus on energy and economic systems. He has a particular research interest in the spatialities of innovation, the governance of technological change, and the role of civil society in innovation and transition processes. He is co-editor of the International Journal of Community Currency Research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. For SEL, SOL and Troc tes Trucs (French); Regiogeld and Tauschkreis (German) and Banco del Tiempo (Spanish).

References

- Aldridge, T., and A. Patterson. 2002. “LETS Get Real: Constraints on the Development of Local Exchange Trading Systems.” Area 34 (4): 370–381. doi: 10.1111/1475-4762.00094

- Coenen, L., P. Benneworth, and B. Truffer. 2012. “Toward a Spatial Perspective on Sustainability Transitions.” Research Policy 41 (6): 968–979. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.014

- Collom, E., J. N. Lasker, and C. Kyriacou. 2012. Equal Time, Equal Value. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Douthwaite, R. 1996. Short Circuit: Strengthening Local Economies for Security in an Unstable World. Totnes: Green Books.

- Geels, F. W. 2002. “Technology Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-level Perspective and a Case Study.” Research Policy 28 (5): 469–488.

- Geels, F. 2005. “The Dynamics of Transitions in Socio-technical Systems: A Multi-level Analysis of the Transition Pathway from Horse-Drawn Carriages to Automobiles.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 17 (4): 445–476. doi: 10.1080/09537320500357319

- Geels, F., and R. Raven. 2006. “Non-linearity and Expectations in Niche-Development Trajectories: Ups and Downs in Dutch Biogas Development (1973–2003).” Technological Analysis and Strategic Management 18 (3/4): 375–392. doi: 10.1080/09537320600777143

- Geels, F., and J. Schot. 2007. “Typology of Socio-technical Transition Pathways.” Research Policy 36 (3): 399–417. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003

- Georg, S. 1999. “The Social Shaping of Household Consumption.” Ecological Economics 28: 455–466. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(98)00110-4

- Gómez, G. 2012. “Sustainability of the Argentine Complementary Currency Systems: Four Governance Systems.” International Journal of Community Currency Research 16 (D): 80–90.

- Grin, J., J. Rotmans, and J. Schot. 2010. Transitions to Sustainable Development. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hargreaves, T., S. Hielscher, G. Seyfang, and A. Smith. 2013. “Grassroots Innovations in Community Energy: The Role of Intermediaries in Niche Development.” Global Environmental Change 23 (5): 868–880. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.008

- Hess, D. 2007. Alternative Pathways in Science and Industry: Activism, Innovation and the Environment in an Era of Globalization. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Kemp, R., J. Schot, and R. Hoogma. 1998. “Regime Shifts to Sustainability Through Processes of Niche Formation: The Approach of Strategic Niche Management.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 10: 175–119. doi: 10.1080/09537329808524310

- Kirwan, J., B. Ilbery, D. Maye, and J. Carey. 2013. “Grassroots Social Innovations and Food Localisation: An Investigation of the Local Food Programme in England.” Global Environmental Change 23: 830–837. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.12.004

- Lasker, J., E. Collom, and C. Kyriacou. 2011. “Time Banks in the United States: Organizational and Membership Diversity.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for the Study of Social Problems, Las Vegas, NV, August 20.

- Longhurst, N. 2012. “The Totnes Pound: A Grassroots Technological Niche.” In Enterprising Communities: Grassroots Sustainability Innovations, edited by A. Davies, 163–188. Bingley: Emerald.

- Ornetzeder, M., and H. Rohracher. 2013. “Of Solar Collectors, Wind Power, and Car Sharing: Comparing and Understanding Successful Cases of Grassroots Innovations.” Global Environmental Change 23: 856–867. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.12.007

- Pearson, R. 2003. “Argentina's Barter Networks: New Currency for New Times.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 22 (2): 214–230. doi: 10.1111/1470-9856.00074

- Powell, J. 2002. Petty Capitalism, Perfecting Capitalism or Post-capitalism? Lessons from the Argentinian Barter Network. ORPAS – Institute of Social Studies (The Hague), Working Paper 357.

- Raven, R. 2012. “Analysing Emerging Sustainable Energy Niches in Europe: A Strategic Niche Management Perspective.” In Governing the Energy Transition: Reality, Illusion or Necessity? edited by G. Verbong and D. Loorbach, 125–151. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Schot, J., and F. Geels. 2008. “Strategic Niche Management and Sustainable Innovation Journeys: Theory, Findings, Research Agenda and Policy.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 20: 537–554. doi: 10.1080/09537320802292651

- Seyfang, G. 2009. The New Economics of Sustainable Consumption: Seeds of Change. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Seyfang, G., and A. Haxeltine. 2012. “Growing Grassroots Innovations: Exploring the Role of Community-Based Initiatives in Sustainable Energy Transitions.” Environment and Planning C 30 (3): 381–400. doi: 10.1068/c10222

- Seyfang, G., S. Hielscher, T. Hargreaves, M. Martiskainen, and A. Smith. 2014. “A Grassroots Sustainable Energy Niche? Reflections on Community Energy in the UK.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 13: 21–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2014.04.004

- Seyfang, G., and N. Longhurst. 2013a. “Growing Green Money? Mapping Grassroots Currencies for Sustainable Development.” Ecological Economics 86: 65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.11.003

- Seyfang, G., and N. Longhurst. 2013b. “Desperately Seeking Niches: Grassroots Innovations and Niche Development in the Community Currency Field.” Global Environmental Change 23 (5): 881–891. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.007

- Seyfang, G., and A. Smith. 2007. “Grassroots Innovations for Sustainable Development: Towards a New Research and Policy Agenda.” Environmental Politics 16 (4): 584–603. doi: 10.1080/09644010701419121

- Smith, A. 2007. “Translating Sustainabilities Between Green Niches and Socio-technical Regimes.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 19 (4): 427–424. doi: 10.1080/09537320701403334

- Smith, A., S. Hielscher, T. Hargreaves, M. Martiskainen, and G. Seyfang. Forthcoming. “Making the Most of Community Energies: Three Perspectives on Grassroots Innovation.” Environment and Planning A.

- Smith, A., and R. Raven. 2012. “What Is Protective Space? Reconsidering Niches in Transitions to Sustainability.” Research Policy 41 (6): 1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012

- Smith, A., and G. Seyfang. 2013. “Constructing Grassroots Innovations for Sustainability.” Global Environmental Change 23 (5): 827–829. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.003

- Smith, A., J.-P. Voss, and J. Grin. 2010. “Innovation Studies and Sustainability Transitions: The Allure of the Multi-level Perspective and Its Challenges.” Research Policy 39 (4): 435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.023

- Verheul, H., and P. Vergragt. 1995. “Social Experiments in the Development of Environmental Technology: A Bottom-up Perspective.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 7: 315–326. doi: 10.1080/09537329508524215

- White, R., and A. Stirling. 2013. “Sustaining Trajectories Towards Sustainability: Dynamics and Diversity in UK Communal Growing Activities.” Global Environmental Change 23: 838–846. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.06.004

- Witkamp, M., R. Raven, and L. Royakkers. 2011. “Strategic Niche Management of Social Innovations: The Case of Social Entrepreneurship.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 23 (6): 667–681. doi: 10.1080/09537325.2011.585035