ABSTRACT

Do-It-Yourself laboratories (DIY labs) are autonomous community-based science research spaces that facilitate creative experiments independently in an unstructured location. The research on do-it-yourself (DIY) laboratories is emerging and there remain various questions to answer about the structure, leadership style, innovation strategies and environmental and public safety policies of DIYs. Keeping in view various challenges of DIY labs, this study theoretically highlights the challenges of DIY labs and competencies required for DIY leaders in coping with challenges and driving innovation. Drawing on existing literature of entrepreneurial leadership competencies, this paper proposes a comprehensive entrepreneurial leadership competency model comprising of personal, functional, interpersonal, technological, ethical and environmental competencies. This study offers insights into the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and DIY innovation, thus laying a foundation for further research in this domain. The competency model proposed in this study helps individuals to understand and learn the capabilities of becoming more effective DIY entrepreneurial leaders and foster innovation and creativity in DIY labs.

Introduction

Do-It-Yourself laboratories (DIY labs), also known as ‘citizen laboratories’ or ‘hackerspaces’, are autonomous community-based science research spaces facilitating creative experiments independently in an unstructured location unlike the traditional research activities carried out by universities and other formal research institutions. These democratised technological practice points have gained substantial attention among researchers in recent times (Yoon, Vonortas, and Han Citation2020). The recent expansion of DIY labs has attracted a significant number of science enthusiasts, volunteers, and practitioners, encouraging learning, and sharing of scientific knowledge. Besides, DIY labs play an integral role by involving ordinary individuals in practising and advancing science, technology and innovation (Hecker et al. Citation2018; Yoon, Vonortas, and Han Citation2020). DIY labs enable communities to learn and share knowledge about emerging technological and product innovation (Sarpong and Rawal Citation2020). The recent growth of DIY labs is backed by multiple factors such as cheap laboratory equipment, readymade materials and excessive scientific information (Million-Perez Citation2016). Moreover, sophisticated internet and digital business environment, accessible knowledge and information on various websites and online forum such as DIYbio.org, Facebook.com, and Slack.com have fuelled the growth of DIY in recent times (Grey, Dyer, and Gleeson Citation2017).

Since the emergence of DIY laboratories, a significant number of scientists have engaged in DIY experimental work. As a result, a growing number of subsidiaries that are linked with DIY laboratories have emerged in various parts of the world (You et al. Citation2020). These DIY labs usually operate under different names such as DIYbio labs, Hackerspaces and Fab Labs. These multiple names indicate that these spaces associated with DIY labs are growing drastically. As a salient example, Fab labs were initiated with 6 labs in 2004, reached 413 labs in 2013, and to date, Fab Foundation Network has 1830 DIY labs operating in more than 100 countries worldwide. The data regarding American DIY labs reveal that 57% of American adults comprising 135 million people are engaged with DIY labs and considered as makers (Stone Citation2015). The number of participants attending the events of Maker Fairs (an event to celebrate arts, crafts, engineering, science projects and the DIY mind-set) surged to 83,000 in 2009 (You et al. Citation2020).

The existing DIY labs have three categories. First, the subsistence DIY; second, industrial DIY; and the latest type of DIY is termed the ‘third wave of DIY’. The subsistence DIY wave is concerned with the basic needs of people; they fulfil their requirements by themselves without purchasing anything from the marketplace. The industrial DIY involves tools and kits available in the market for designing and making products with standardised instruction such as self-assembled furniture, equipment, etc. Conversely, the third wave of DIY underpins reading/writing features of the internet that enable the typical user to make digital-driven design, manufacture and sell goods via websites as per their innovative capacity. The third wave DIY can be carried out by anyone at any place (Fox Citation2014) and has the most potential for innovation.

The recent increase in DIY operations is pushed by various factors such as the availability of open-source-garage, cheap equipment, advancements in information technology and web-based communities (Sarpong et al. Citation2020). Notwithstanding the growing popularity of DIY labs, various scholars have expressed their concern about its regulation and operations (Ferretti Citation2019;Wolinsky Citation2005), the ethical issues (Wexler Citation2016; Fiske et al. Citation2019), irresponsible use of science (Tanenbaum et al. Citation2013) and public health and environmental safety concerns (Gorman Citation2010; Revill and Jefferson Citation2014). Besides, lack of clear ownership (Yoon, Vonortas, and Han Citation2020), strict regulation by government authorities, unsustainable financial support and lack of dedicated leadership (Seyfried, Pei, and Schmidt Citation2014) are some of the critical challenges faced by DIYs.

Despite the exponential growth of various types of DIY labs across the world, there is limited discussion available in the academic literature about DIY labs, especially from a business management perspective. One of the key reasons for the lack of research in this context is because DIY lab’s research is mainly focused on science and engineering fields. In contrast, DIY labs have not yet attracted interest in organisation and management research (Fox Citation2014; Howard, Boeker, and Andrus Citation2019; Galvin, Burton, and Nyuur Citation2020). Prior studies focused on DIY labs and their social structure and discussed the importance of collaborative work (Guthrie Citation2014). Some studies also discussed the strategies of DIY labs and their implementation by focusing on the ecosystem theory, and highlighted how DIY stakeholders participate in laboratory work (Bloom and Dees Citation2008). The extant literature also focused on the motivation, characteristics, background and expertise of individual entrepreneurs, hobbyists, engineers and designers (Hatch Citation2013; Baden et al. Citation2015; Martin Citation2015; Galvin, Burton, and Nyuur Citation2020).

Drawing on prior research that focused on the growth of DIY labs and increasing participation of stakeholders, it is pertinent to explore the leadership styles and management of DIY labs. It is important that we know the leadership skills and competencies required for driving innovation in DIY laboratories. The organisation of the current era has witnessed a paradigm shift from relying on what to do and why to do, to new tasks, methods, and process to be innovative. As a result of this paradigm shift, there is more reliance on the skills and competencies of leaders as compared to management (Guo Citation2009). Researchers from the field of entrepreneurship argue that executing entrepreneurial activities carry various uncertainties, complexities, and challenges. This has led to the clarion call for more studies on entrepreneurial leadership (Simba and Thai Citation2019). Entrepreneurial leadership though a distinct field of study within the domain of leadership is deeply embedded in the positive integration of the fields of leadership and entrepreneurship (Harrison et al. Citation2020). Entrepreneurial leadership is recognised as a key driver of innovation and constant change in large and small and medium enterprises (Leitch and Volery Citation2017).

According to Leitch, McMullan, and Harrison (Citation2009), SMEs can develop entrepreneurial leadership through an action-based learning approach underpinned by the social and relational learning process. For effective leadership in SMEs and solving complex organisation challenges, the development of personal and functional competencies of entrepreneurial leaders is crucial (Leitch and Volery Citation2017; Simba and Thai Citation2019). Moreover, Leitch, McMullan, and Harrison (Citation2013) exploring entrepreneurial leadership in the context of human, social and institutional capital in SMEs, argue that entrepreneurial leadership is a social process and entrepreneurs learn from relational learning that occurs in active encounters of peer to peer interactions and trust building within the organisation. Thus, it is a recognised leadership approach geared towards achieving strategic value creation (Harrison et al. Citation2020).

Similarly, as the core purpose of DIY labs is to undertake innovative research and experimental work to gain economic benefit, its survival and long-term sustainability reside on innovation and creative inputs from team members. Executing entrepreneurial activities carry various uncertainties, complexities and challenges. Entrepreneurial leaders need to learn specific individual competencies that enable them to lead the entrepreneurial activities in turmoil situations to achieve entrepreneurial vision (Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004; Bagheri and Pihie Citation2011). As argued by Leitch and Volery (Citation2017), personal and functional competencies of entrepreneurial leaders are crucial in coping with business challenges and dealing with constant innovation and change. Therefore, the role of the lead entrepreneur or entrepreneurial leader and their capability and skills in attracting other organisational members is vital (Chen Citation2007). However, the primary DIY literature has largely disregarded the role of entrepreneurial leadership and its competencies in managing and sustaining innovation at DIY labs. Given the infancy of literature from the management viewpoint, the kind of leadership challenges DIY labs face and the specific competencies DIY entrepreneurial leaders require to foster innovation, represent major research gaps in the extant literature. Thus, we seek to advance the scholarship in this domain by addressing entrepreneurial leadership competencies in the context of DIY labs and drawing on existing EL competency models, this paper presents a competency framework of entrepreneurial leadership from a DIY perspective.

This article begins with a discussion of the convergent evolution of entrepreneurship and leadership. In later parts, entrepreneurial leadership is defined and its competencies and their relevance to DIY, are discussed. Moreover, this paper reviews and synthesises extant literature. It identifies the challenges of DIY labs and presents a competency model of entrepreneurial leadership with detailed explanation. The major research elements along with research and practical implications are examined in the discussion section. Areas for future research are highlighted. Finally, in the conclusion, the key contributions of the paper are summarised.

Conducting the review

The aim of the study is to highlight the challenges of DIY laboratories and propose an integrated competency model for driving innovation in DIY labs. Therefore, the present study aims to enhance our understanding about entrepreneurial leadership and its relationship with DIY labs in driving innovation. To meet this end, this study adopted a narrative literature review to search relevant literature from both research streams. A narrative literature review aims to summarise and presents a critical analysis of literature on a given field of enquiry thus helping the researcher in drafting the research questions and building hypothesis (Cronin, Ryan, and Coughlan Citation2008). It was important that several fields are examined to provide a broader picture of entrepreneurial leadership, competencies and DIY. Keywords such as entrepreneurship, leadership, entrepreneurial leadership, DIY innovation, laboratories and entrepreneurial leadership competencies were employed as search strings in databases such as Emerald, Web of Science, Sage, Taylor and Francis, SpringerLink, Science Direct and ABI/PROQUEST. Such approaches were useful to synthesise extant literature based on entrepreneurial leadership and DIY research.

Entrepreneurship and leadership

The research on entrepreneurship and leadership has spanned over several decades. Notwithstanding the extensive investigation that has taken place in both disciplines, there yet remain some substantial overlaps and parallels in historical and conceptual viewpoint in both fields (Cogliser and Brigham Citation2004; Harrison, Paul, and Burnard Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Harrison, Burnard, and Paul Citation2018). Historically, entrepreneurship and leadership literature share the same process of theory evolution. Initially, both fields focused on innate qualities and characteristics of leaders and entrepreneurs that subsequently led to the emergence of the ‘trait theory’. Later, the effect of followers and contextual factors emerged in theories of both disciplines. In this regard, various researchers attempted to pinpoint the capabilities of leaders and entrepreneurs through which they influence their followers and enact organisational vision (Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004; Bagheri, Lope Pihie, and Krauss Citation2013). However, inconsistent research findings of leaders’ and entrepreneurs’ capabilities induced the researchers toward a dynamic shift from the traits and situational factors to an evolutionary dynamic learning process (Kempster and Cope Citation2010). As a result of this learning process, both entrepreneurs and leaders learn personal and functional competencies to cope with the challenges of competitive and turbulent environments (Bagheri and Pihie Citation2011; Leitch and Volery Citation2017). To date, various scholars have investigated the similarities of both fields and highlighted several overlapping characteristics of leaders and entrepreneurs such as innovativeness, risk-taking propensity and envisioning capabilities . Given the similarities of both fields, some studies have recognised entrepreneurship as a type of leadership on the ground of their common behaviour irrespective of contextual differences (Vecchio Citation2003; Bagheri, Lope Pihie, and Krauss Citation2013). However, some researchers express a contrary opinion regarding an entrepreneur as a leader. They argue that an entrepreneur is more than a leader as the role of the entrepreneur is more challenging in terms of starting the venture from the scratch and facing various challenges of tricky situations to succeed (Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004). Both entrepreneurs and leaders have different complexities in personality, skills and attributes since an entrepreneur needs to perform various roles in different situations simultaneously. Therefore, for the success and development of a new venture, an entrepreneurial leader needs to develop a particular set of competencies (Swiercz and Lydon Citation2002; Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004 ; Bagheri and Harrison Citation2020;).

The theoretical and conceptual overlaps between the two fields led to the emergence of a new phenomenon known as ‘entrepreneurial leadership’. The emergence of entrepreneurial leadership as a new paradigm of enquiry, not only helps in fabricating research and practice in the entrepreneurship and leadership arena but also shares distinct properties that both fields lack separately (Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004; Clark and Harrison Citation2018, Citation2019). presents some studies that have investigated entrepreneurial leadership as a convergence of entrepreneurship and leadership.

Table 1. Some studies that have investigated entrepreneurial leadership as the convergence of entrepreneurship and leadership.

Entrepreneurial leadership: definition and competencies

Entrepreneurial leadership (EL) is still at the embryonic stage of conceptual and theoretical development and is defined as a distinct form of leadership that is effective in dealing with the challenges and complexities of a highly turbulent environment (Swiercz and Lydon Citation2002; Cogliser and Brigham Citation2004; Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004; Harrison Citation2018; Clark, Harrison, and Gibb Citation2019). Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie (Citation2004, 242) define entrepreneurial leadership as ‘leadership that creates visionary scenarios that are used to assemble and mobilise a “supporting cast” of participants who become committed by the vision to the discovery and exploitation of strategic value creation’. EL’s initial definition mainly focused on entrepreneurial leaders’ attributes and characteristics. At the same time, recent conceptualisation views entrepreneurial leadership as a process in which leaders use an interpersonal and a systematic approach to mobilise a group of followers to achieve organisational vision. Based on Gupta et al.’s definition, entrepreneurial leaders need to perform two different tasks; scenario enactment and cast enactment. In scenario enactment, entrepreneurial leaders build new ideas and identify ongoing future opportunities to sustain their venture. While in cast enactment, entrepreneurial leaders inspire and influence their followers to ensure their commitment to achieving the objectives of scenario enactment (see, e.g. Bagheri and Pihie Citation2011). A sample of studies that have defined entrepreneurial leadership and the definitions proposed are shown in .

Table 2. Sample of studies that have defined entrepreneurial leadership and the definitions proposed.

The evidence shows that entrepreneurial leadership with characteristics of innovation, customer and competitor orientation has a positive impact on business performance (see, e.g. Harrison, Paul, and Burnard Citation2016a; Harrison, Burnard, and Paul Citation2018). The role of entrepreneurial leadership skills is critical in new venture formation, performance and growth. Entrepreneurial leadership competencies are also recognised as crucial for leaders in leading a current organisation in a growing competitive and challenging environment (Bagheri and Pihie Citation2011; Bagheri and Harrison Citation2020). Various authors have explored the competencies of entrepreneurial leaders in a different context. For instance, Swiercz and Lydon (Citation2002) highlighted two competencies of entrepreneurial leaders, namely, self-competencies and functional competencies. Self-competencies are concerned with the leader’s entrepreneurial orientation at both individual and organisational levels which include proactiveness, innovativeness and risk-taking. In contrast, functional competencies are task-oriented, which include operations, finance, marketing and human resources (Swiercz and Lydon Citation2002; Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004; Frederick, Kuratko, and Hodgetts Citation2007).

Although Swiercz and Lydon (Citation2002) contribution laid the foundation of requisite competencies of entrepreneurial leaders, there is a paucity of discussion in the literature about the specific competencies required for entrepreneurial leaders in leading various entrepreneurial activities successfully (Swiercz and Lydon Citation2002; Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004). Guo (Citation2009) illuminated three core competencies of healthcare entrepreneurial leaders including healthcare environment and system competencies, organisation competencies and interpersonal competencies. Bagheri and Pihie (Citation2011) explored challenges and competencies of student entrepreneurial leaders leading entrepreneurial projects; they identified three critical competencies of entrepreneurial leaders that are the catalyst for leading entrepreneurial projects comprising; (1) creating a close relationship with and among group members, (2) employing a learning and developmental approach toward delegating tasks to group members and (3) building group members’ self-efficacy. Bagheri and Pihie (Citation2012) investigated the entrepreneurial leadership competencies of students through the lens of experience and social interaction. They found that entrepreneurial leadership competencies can be developed through the ongoing process of experiential and socially interactive learning. Bagheri, Lope Pihie, and Krauss (Citation2013) exploring personal competencies of Malaysian student entrepreneurial leaders, identified four personal competencies, namely, proactiveness, innovativeness, love of challenges, and versatility. Furthermore, Ngigi, McCormick, and Kamau (Citation2018) investigated entrepreneurial leadership competencies of mid-level CEOs in the context of Kenya and highlighted two categories of competencies including relational competencies and the task-oriented competencies. These relational competencies include effective bargaining, diplomacy while task-oriented competencies involve innovativeness, proactiveness and flexibility. Moreover, Bagheri and Harrison (Citation2020) drawing on skills, competencies, roles and behaviour of entrepreneurial leaders in the context of Iran and Scotland, developed a multi-dimensional scale of entrepreneurial leaders. Omeihe et al. Citation2020 discussed the skills and attributes of entrepreneurial leaders within the fashion industry of Nigeria; and identified five key skills (technical skills, conceptual skills, interpersonal skills, entrepreneurial skills and expectation management skills) and attributes (hard work, long-term view, passion and length of service, creativity, innovation and vision) of entrepreneurial leaders.

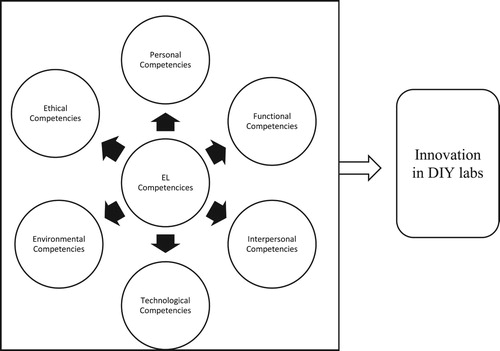

However, the existing literature on entrepreneurial leadership competencies presents a limited perspective. The role of entrepreneurial leaders is more diverse. An entrepreneurial leader needs to address various challenges simultaneously such as technological challenges, environmental issues, public safety and ethical consideration in organisational activities. The above studies mainly focused on personal and functional competencies, interpersonal competencies, system competencies and technological competencies. These studies discuss the components of entrepreneurial leadership competencies separately. Therefore, entrepreneurial leadership research lacks a comprehensive competency model that covers all aspects of competencies. More importantly, there is no discussion in the literature about DIY entrepreneurial leaders and their competencies in driving innovation at DIY labs. This study by reviewing current literature on EL competencies attempts to fill the gap by proposing a comprehensive entrepreneurial leadership competency model in a DIY context.

Entrepreneurial leadership competencies and DIY labs

This study drawing on current EL competency models attempts to develop a competency model for DIY entrepreneurial leaders. In the following segments, we define entrepreneurial leadership competencies and their approaches.

EL literature identifies two approaches in which entrepreneurial leaders carry out their entrepreneurial roles. First, ‘work-oriented approach’ that is concerned with requisite entrepreneurial leadership competencies for performing various functions in different stages of new venture creation and business growth. Second, ‘socio-cultural and situated approach’ an approach which implies that entrepreneurial leadership development is a social process that evolves through the gradual learning process in a particular community context (Kempster and Cope Citation2010; Bagheri and Pihie Citation2011).

The current literature on entrepreneurial leadership competencies overlooks various essential competencies of entrepreneurial leaders. For instance, Swiercz and Lydon (Citation2002) highlighted personal and functional competencies of entrepreneurial leaders and ignored some crucial aspects of entrepreneurial leadership competencies such as interpersonal, ethical and technological competencies. Guo (Citation2009) proposed a model of healthcare entrepreneurial leaders’ competencies comprising, healthcare environment and system competencies, organisation competencies, and interpersonal competencies. However, Guo’s competency model also lacks some essential entrepreneurial leadership competencies such as ethical competencies which are crucial for healthcare to perform their task honestly and maintain healthcare privacy. Moreover, they also need to develop technological skills to deal with the latest technologies in the healthcare operation. Bagheri and Pihie (Citation2011) focused on interpersonal, task delegation and self-efficacy competencies of entrepreneurial leaders. However, they also disregarded technological, environmental and ethical competencies that entrepreneurial leaders need to build and sustain their venture in the long run. Moreover, Ngigi, McCormick, and Kamau (Citation2018) explored relational competencies and the task-oriented competencies of Kenyan mid-level CEOs; however, their competency model does not focus on technological, interpersonal and ethical competencies of entrepreneurial leaders that are also crucial for mid-level CEOs.

Drawing on the existing entrepreneurial leadership competency literature, this study evaluates their competency models and identifies their limitations and suggests a comprehensive competency model focusing on DIY labs. One of the main limitations of previous studies is their focus on individual competencies in terms of personal, functional, interpersonal and technological competencies. None of these studies provides a comprehensive entrepreneurial leadership competency model that covers varying roles of entrepreneurial leaders. Therefore, this paper puts forward a comprehensive entrepreneurial leadership competency model by combining the essential competencies of entrepreneurial leaders that have been discussed in prior research at individual capacities.

Personal competencies

Entrepreneurial leaders’ self-competencies comprise proactiveness, innovativeness and risk-taking. Proactiveness is concerned with being ready for the future through planning instead of reacting and responding to the occurrence of the event. Proactiveness is an entrepreneurial leaders’ personality trait that helps them to make subsequent plans for the future of their business (Bagheri and Pihie Citation2011). Proactiveness enables entrepreneurial leaders to sense the future challenges, identify business opportunities and recognise and plan for forthcoming changes (Okudan and Rzasa Citation2006; Frederick, Kuratko, and Hodgetts Citation2007).

Innovativeness refers to the entrepreneurial leader’s capability of being creative in recognising business opportunities, using resources efficiently and finding an innovative solution to problems (Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004; Okudan and Rzasa Citation2006; Chen Citation2007; Bagheri and Pihie Citation2011; Bagheri and Harrison Citation2020). Unlike traditional leaders, entrepreneurial leaders have creative skills that enable them to think and act on novel ideas and value creation (Surie and Ashley Citation2008). DIY labs engage in research and product development activities independently and their long-term sustainability rests on continuous innovation. For instance, innovative use of scraps and other DIY tools, identifying and exploiting business opportunities and niches neglected by large firms, and applying scarce resources more efficiently, require specific creative skills to generate useful and innovative ideas. These competencies are crucial for DIY labs that are associated with digital platforms and offer innovative read and write services through digital customisation across various online platforms.

Risk-taking is an integral part of the entrepreneurial process and is concerned with the inclination of entrepreneurial leaders to accept the fear of uncertainty and launch their venture owning the responsibility of future contingencies (Chen Citation2007). Entrepreneurial leaders take calculated risks in the launching of new ventures. Unlike managers, entrepreneurial leaders are more risk-takers as they are engaged in various business activities at different phases of the new venture creation and development process (Thomas and Mueller Citation2000). In the same vein, DIY labs are independent research and business hubs and aim to undertake research commercialisation activities at micro-level. Therefore, for leading the successful research activities in DIY labs, leaders must have risk-taking propensity to gain commercial benefit from their endeavours.

Functional competencies

Entrepreneurial leaders perform diverse roles in new venture creation process. Besides the personal competencies, they also need to develop specific competencies related to performing various challenging tasks. These competencies include marketing, finance and human resource competencies (Swiercz and Lydon Citation2002). Nonetheless, there is more claim for scholarly work on specific entrepreneurial leadership functional competencies (Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004). As majority of DIY labs are run by individual entrepreneurs, they have limited resources to hire experts for each segment of organisational activities such as marketing, finance and business management. Therefore, these functional roles must be carried out by entrepreneurial leaders themselves. In this regard, entrepreneurial leaders need to learn basic finance and accounting, marketing tools, techniques and their applications and organisational management to successfully lead their DIY ventures.

Interpersonal competencies

For successful entrepreneurial leaders, development of interpersonal competencies is inevitable. Guo (Citation2009) suggests that entrepreneurial leaders can build their interpersonal competencies through the principles of effective communication, human resources, and motivation. Interpersonal competencies mainly involve the self-development of entrepreneurial leaders; how entrepreneurial leaders conceive themselves, their strengths, weakness, areas of improvement and their self-impact on other members of the organisation (Harrison, Burnard, and Paul Citation2018). In this regard, entrepreneurial leaders must develop relationships and maintain professional networks that lead to superior team performance in the workplace. Entrepreneurial leaders need to develop an environment that facilitates a transparent exchange of ideas, emotions and understanding from both poles in the communication process. Clear inflow and outflow of information at the workplace enhances employees’ capabilities to develop their communication behaviour and subsequently makes them more creative at dealing with their respective tasks. Similarly, entrepreneurial leaders associated with DIY must develop their interpersonal competencies to facilitate innovative idea generation and opportunity exploitation.

Technological competencies

Technological competence is concerned with the entrepreneurial leader's capability of using various technologies at the workplace such as office automation, robots, machine learning and the internet of things (Songkünnatham Citation2018; Putsom, Suwannarat, and Songsrirote Citation2019). Technological competence enables entrepreneurial leaders to use technology and latest equipment proficiently to oversee their business operation effectively (Putsom, Suwannarat, and Songsrirote Citation2019). It requires specific consideration from leaders because it is the only type of competence that rapidly changes. Technological competence enhances employee’s innovativeness, business performance and organisational competitive advantage (BolíVar-Ramos, GarcíA-Morales, and García-Sánchez Citation2012). In DIY labs, entrepreneurial leaders perform various scientific research work, offer online services on the digital platforms, and use multiple DIY tools independently. Therefore, they must focus on the development of technological competency to perform state of the art research and commercialise their products using digital platforms.

Environmental competencies

DIY labs are operated remotely, and most of them are unregulated. The researchers express deep concern over the unregulated operations of DIY labs towards the environment. On the one hand, DIY labs are recognised as the source of growth specifically in scientific research. For instance, DIY bio-synthetic biology where better tools and models are developed to explore and exploit the living system. In this regard, engineers and biologists design and develop innovative bio-molecular components and devices that facilitate the creation of cheaper drugs, targeted therapies for diseases like cancer (Khalil and Collins Citation2010; Landrain et al. Citation2013). On the other hand, junior scientists and engineers undertaking projects such as engineered bacteria in untraditional research centres present severe safety and security threats to stakeholders and the environment (Landrain et al. Citation2013). Therefore, along with other entrepreneurial leadership competencies, environmental competence is also crucial for the sustainable growth and success of DIY labs. Entrepreneurial leaders must focus on the system where DIY labs operate, and they should enhance their understanding of how to improve its lab activities and align their operations ensuring environment and public wellbeing.

Ethical competencies

Researchers often criticise the missing element of the ethical dimension in entrepreneurial leadership. It is argued that pragmatism enables entrepreneurs to achieve innovation and accomplishment (Surie and Ashley Citation2008). However, the ethical dimension assists entrepreneurial leaders to develop the legitimacy essential for value creation, discovery and change ethics in organisations. It is inevitable that a conceptual foundation for entrepreneurial leadership needs ethics as an integral part. Ethics and entrepreneurial leadership are aligned through pragmatic and action-oriented approach to moral grounds in organisations that enable building trust and commitment among organisational members (Surie and Ashley Citation2008). As a result of this approach, organisations can achieve better value creation and sustainable innovation. It is important for entrepreneurial leaders to assess their actions and their impacts through the prism of long-term credibility. As entrepreneurial leaders’ role is characterised as evolving in nature, it results in altering the current norms and forming a new one. In this manner, growing practice and standard in various domains should reflect ethical behaviour and its reinforcement (Surie and Ashley Citation2008). Similarly, the leadership of DIY labs carries out different experimental and research work in independent labs; their actions have long term footprints on society and the environment. Therefore, ethics and values must be part of their leadership practices to meet both ends. presents a combined competency model for entrepreneurial leaders. These competencies are further explained below:

Entrepreneurial leadership and innovation at DIY labs

Various studies suggest that the role of leaders is critical in terms of inspiring the followers and stimulating their innovative work behaviour and performance (Soriano and Martínez Citation2007; Chen et al. Citation2014; Bagheri Citation2017). In this regard, several studies have found a significant positive relationship between leadership style and employees innovative work behaviour, opportunity recognition, creative capabilities and sustainable growth of the various types of businesses (De Jong and den Hartog Citation2010; Koryak et al. Citation2015; Chen, Li, and Leung Citation2016; Bagheri Citation2017). Specifically, the role of leadership has a significant impact on driving innovation in high-tech businesses and managing the innovation process (Waldman and Bass Citation1991). According to Tung and Yu (Citation2016), employees are not creative themselves; instead, it is the supporting role of leaders that stimulates their creativity.

Notwithstanding the emphasis of various studies on the role of leadership style on individual innovation, limited studies focused on the impact of leadership style in fostering innovation and employees’ opportunity recognition (De Jong and den Hartog Citation2010; Kang, Solomon, and Choi Citation2015; Koryak et al. Citation2015). The research on the role of leadership styles in driving innovation shares inconsistent findings. In this connection, some leadership styles are more capable of supporting, managing and implementing organisation’s innovation strategies. However, some scholars argue that generic leadership styles (e.g. transformational/transactional) may not be suitable in dealing with the complex innovation processes and driving employee innovative behaviour (Sharifirad Citation2013; Dóci, Stouten, and Hofmans Citation2015). Particularly, leaders associated with high-tech businesses, marshal substantial resources for scientific, and technological research and development activities. They need these resources to develop specific leadership competencies to successfully lead the innovation and opportunity recognition process in their businesses (Chen et al. Citation2014; Bagheri Citation2017). In this context, the evidence from numerous studies suggests that entrepreneurial leadership plays a positive role in fostering employees’ innovation and opportunity recognition in the growing competitive business world (Swiercz and Lydon Citation2002; Freeman and Siegfried Jr Citation2015; Karol Citation2015).

Entrepreneurial leaders and their team must be creative to generate innovative ideas to identify business opportunities in market or technology (Chen Citation2007). Damanpour (Citation1991) suggests that organisations of the current era witness multifaceted challenges due to growing workforce complexity and turbulent business environment. Therefore, the top management leadership style has become an enabling factor in directing organisational innovation. Since an individual or team of entrepreneurs create most new ventures, the role of the lead entrepreneur is a determining factor for organisational innovation in several ways. First, entrepreneurial leaders articulate the organisation vision and envisage the scenarios to followers. They convince their followers in achieving the goals through envisaging challenges, absorbing uncertainty, maintaining flexible behaviours and winning commitment (Ireland and Hitt Citation1999; Timmons Citation1999; Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie Citation2004). Second, entrepreneurial leaders with attributes of patience, enthusiasm, flexibility, communication and networking competence build an entrepreneurial culture in organisations (Timmons Citation1999). Third, entrepreneurial leaders with aggressive behaviour towards business opportunities, risk-taking, innovative propensity and proactive behaviour capitalise on business opportunities more quickly than their competitors (Lumpkin and Dess Citation1996). Fourth, entrepreneurial leaders are recognised as change agents and they facilitate creative problem solving and encourage team creativity. They empower the team member in improving their task and achieving superior goals (see, e.g. Chen Citation2007). Therefore, entrepreneurial leadership and its characteristics of innovativeness, risk-taking and proactiveness are essential for leaders at DIY labs in finding innovative solutions to their underlying problems to remain sustainable.

Discussion

The main purpose of this paper is to identify the challenges of DIY labs and to develop a competency model for entrepreneurial leaders in DIY labs. This paper by reviewing and synthesising existing literature on entrepreneurial leadership and DIY identified the challenges of DIY labs and proposed a competency model for entrepreneurial leaders in DIY labs. The proposed model comprises of six essential entrepreneurial leadership competences that entrepreneurial leaders need to develop in DIY labs namely, personal competencies, functional competencies, interpersonal competencies, technological competencies, ethical competencies and environmental competencies.

Although these competencies have been discussed in prior studies at an individual level, this paper aimed to advance entrepreneurial leadership competency literature by proposing a more comprehensive and integrated competency model. By integrating the various aspects of leadership capabilities, the model helps entrepreneurial leaders to play a diversified role in dealing with the challenges of the DIY labs and driving innovation. Prior studies highlighted that unstructured organisational format, lack of dedicated leadership, environmental and public safety are some of the major challenges that DIY confront today. Therefore, by adopting the proposed competency model, entrepreneurial leaders can identify and exploit business opportunities in a more effective manner.

Research and practical implications

The model offers several implications for research within leadership and the DIY arena. First, the model can be used as baseline for investigating the competencies of DIY entrepreneurial leaders. Second, the model enhances the understanding of entrepreneurial leadership competencies and facilitates future theory development. Finally, the researchers evaluating the different aspects of the proposed model, may add more components making it suitable for effective performance of DIY labs and other sectors.

The model proposed by this paper guides DIY entrepreneurial leaders in improving organisational performance and achieving sustainable innovation. Besides, by applying the competency model, DIY entrepreneurial leaders can build the trust of government and other regulatory bodies by ensuring public and environmental safety. As a result, they will be able to obtain more financial resources to expand their operations. The proposed competency model can be used as a tool by DIY leaders to understand the competencies and use it for self-improvement and achieving organisational vision. It can be applied by policy makers and other regulatory bodies in devising strategies for DIY labs.

Future research directions

Notwithstanding the significant implication of the entrepreneurial leadership competency model in leadership and entrepreneurship research and practice, there is a further need for empirical evidence to assess the reliability and validity of the DIY entrepreneurial leadership competency model. The model may be tested by considering the data from various geographical locations by cross-comparison to examine the cultural and contextual impact on the phenomenon. Further research on how DIY entrepreneurial leaders can learn and develop these capabilities, also enrich the research on entrepreneurship, leadership and DIY. More empirical investigation is required to assess which aspect of EL competency model is more influential on DIY performance. Future studies may apply the model on the context of new ventures and SMEs. Such studies may compare entrepreneurial leadership style with other leadership styles (e.g. transformational and transactional) as an antecedent of innovation in DIY labs.

Conclusion

The extant literature highlights that entrepreneurial leadership is an emerging phenomenon and there is paucity of discussion about entrepreneurial leadership assessment tools and its applicability in large and small organisations (Leitch and Volery Citation2017). However, the evidence from the literature supports the premise that entrepreneurial leadership is a leadership approach suitable for coping with the challenges of complex and uncertain business environments. In this regard, the research highlights that DIY labs experience various challenges such as unstructured leadership, environmental and public safety challenges and managing innovation and creativity. Therefore, DIY labs require a more flexible, risk-taking and opportunity driven leadership style that can facilitate swift opportunity identification and exploitation. For DIY labs to sustain their competitive advantage, they should adopt an entrepreneurial leadership style. This is important for long-term innovativeness. Given the multifaceted challenges of DIY labs, leaders within this context will need to develop their personal, functional, interpersonal, technological, environmental and ethical competencies to cope with the ever-growing challenges.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fida Ahmed

Mr Fida Ahmed is a PhD candidate at the University of the West of Scotland and conducting his research on entrepreneurial leadership with specific focus on the competencies of entrepreneurial leaders working as group at business incubation centres in context of Pakistan.

Christian Harrison

Dr Christian Harrison is the programme leader of the MSc Leadership and Management and MSc International Management in the School of Business and Creative Industries in the University of the West of Scotland. He is the author of numerous published peer-reviewed papers on Entrepreneurial Leadership which is his major research interest and serves as the Director of Studies of several doctoral students. He is also the Chair of the Leadership and Leadership Development Special Interest Group of the British Academy of Management. Christian works extensively as a consultant on leadership development within organisations. He is the founder of the NGO, The Leadership Mould Initiative International. The NGO supports students and moulds future leaders. He is also the author of the book entitled ‘Leadership Theory and Research: A Critical Approach to New and Existing Paradigms’, which is published by the globally renowned publishing company; Palgrave MacMillan.

References

- Baden, T., A. M. Chagas, G. Gage, T. Marzullo, L. L. Prieto-Godino, and T. Euler. 2015. “Open Labware: 3-D Printing Your Own Lab Equipment.” PLoS Biology 13 (3): e1002086.

- Bagheri, A. 2017. “The Impact of Entrepreneurial Leadership on Innovation Work Behavior and Opportunity Recognition in High-Technology SMEs.” The Journal of High Technology Management Research 28 (2): 159–166.

- Bagheri, A., and C. Harrison. 2020. “Entrepreneurial Leadership Measurement: A Multi-dimensional Construct.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 27 (4): 659–679.

- Bagheri, A., Z. A. Lope Pihie, and S. E. Krauss. 2013. “Entrepreneurial Leadership Competencies among Malaysian University Student Entrepreneurial Leaders.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 33 (4): 493–508.

- Bagheri, A., and Z. A. L. Pihie. 2011. “Entrepreneurial Leadership: Towards a Model for Learning and Development.” Human Resource Development International 14 (4): 447–463.

- Bagheri, A., and Z. A. L. Pihie. 2012. “Entrepreneurial Leadership Competencies Development among Malaysian University Students: The Pervasive Role of Experience and Social Interaction.” Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities 20 (2): 539–562.

- Bloom, P. N., and G. Dees. 2008. “Cultivate Your Ecosystem.” Stanford Social Innovation Review 6 (1): 47–53.

- BolíVar-Ramos, M. T., V. J. GarcíA-Morales, and E. García-Sánchez. 2012. “Technological Distinctive Competencies and Organizational Learning: Effects on Organizational Innovation to Improve Firm Performance.” Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 29 (3): 331–357.

- Chen, M. 2007. “Entrepreneurial Leadership and New Ventures: Creativity in Entrepreneurial Teams.” Creativity and Innovation Management 16 (3): 239–249.

- Chen, T., F. Li, and K. Leung. 2016. “When Does Supervisor Support Encourage Innovative Behavior? Opposite Moderating Effects of General Self-efficacy and Internal Locus of Control.” Personnel Psychology 69 (1): 123–158.

- Chen, Y., G. Tang, J. Jin, Q. Xie, and J. Li. 2014. “CEOs’ Transformational Leadership and Product Innovation Performance: The Roles of Corporate Entrepreneurship and Technology Orientation.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 31: 2–17.

- Clark, C. M., and C. Harrison. 2018. “Leadership: The Complexities and State of the Field.” European Business Review 30 (5): 514–528.

- Clark, C., and C. Harrison. 2019. “Entrepreneurship: An Assimilated Multi-perspective Review.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 31 (1): 43–71.

- Clark, C., C. Harrison, and S. Gibb. 2019. “Developing a Conceptual Framework of Entrepreneurial Leadership: A Systematic Literature Review and Thematic Analysis.” International Review of Entrepreneurship 17 (3): 347–384.

- Cogliser, C. C., and K. H. Brigham. 2004. “The Intersection of Leadership and Entrepreneurship: Mutual Lessons to be Learned.” The Leadership Quarterly 15 (6): 771–799.

- Cronin, P., F. Ryan, and M. Coughlan. 2008. “Undertaking a Literature Review: a Step-by-Step Approach.” British Journal of Nursing 17 (1): 38–43.

- Damanpour, F. 1991. “Organizational Innovation: A Meta-analysis of Effects of Determinants and Moderators.” Academy of Management Journal 34 (3): 555–590.

- De Jong, J., and D. den Hartog. 2010. “Measuring Innovative Work Behaviour.” Creativity and Innovation Management 19 (1): 23–36.

- Dóci, E., J. Stouten, and J. Hofmans. 2015. “The Cognitive-behavioral System of Leadership: Cognitive Antecedents of Active and Passive Leadership Behaviors.” Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1344–1344.

- Fernald, L. W., G. T. Solomon, and A. Tarabishy. 2005. “A new Paradigm: Entrepreneurial Leadership.” Southern Business Review 30 (2): 1–10.

- Ferretti, F. 2019. “Mapping do-it-Yourself Science. Life Sciences.” Society and Policy 15 (1): 1–23.

- Fiske, A., L. Del Savio, B. Prainsack, and A. Buyx. 2019. “Conceptual and Ethical Considerations for Citizen Science in Biomedicine.” In Personal Health Science, 195–217. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Fox, S. 2014. “Third Wave Do-It-Yourself (DIY): Potential for Prosumption, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship by Local Populations in Regions Without Industrial Manufacturing Infrastructure.” Technology in Society 39: 18–30.

- Frederick, H. H., D. F. Kuratko, and R. M. Hodgetts. 2007. Entrepreneurship: Theory, Process, Practice. Mason, OH: Thomson.

- Freeman, D., and R. L. Siegfried Jr. 2015. “Entrepreneurial Leadership in the Context of Company Start-Up and Growth.” Journal of Leadership Studies 8 (4): 35–39.

- Galvin, P., N. Burton, and R. Nyuur. 2020. “Leveraging Inter-Industry Spillovers Through DIY Laboratories: Entrepreneurship and Innovation in the Global Bicycle Industry.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 160: 120–235.

- Gorman, B. J. 2010. “Patent Office as Biosecurity Gatekeeper: Fostering Responsible Science and Building Public Trust in DIY Science.” John Marshall Review of Intellectual Property 10: 423–449.

- Grey, T., M. Dyer, and D. Gleeson. 2017. “Using Big and Small Urban Data for Collaborative Urbanism.” In Citizen Empowerment and Innovation in the Data-Rich City, 31–54. Cham: Springer.

- Guo, K. L. 2009. “Core Competencies of the Entrepreneurial Leader in Health Care Organizations.” The Health Care Manager 28 (1): 19–29.

- Gupta, V., I. C. MacMillan, and G. Surie. 2004. “Entrepreneurial Leadership: Developing and Measuring a Cross-cultural Construct.” Journal of Business Venturing 19 (2): 241–260.

- Guthrie, C. 2014. “Empowering the Hacker in Us: A Comparison of Fab lab and Hackerspace Ecosystems.” 5th LAEMOS (latin American and European meeting on organization studies) colloquium, Havana Cuba.

- Harrison, C. 2018. Leadership Theory and Research: A Critical Approach to New and Existing Paradigms. Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Harrison, C., K. Burnard, and S. Paul. 2018. “Entrepreneurial Leadership in a Developing Economy: A Skill-based Analysis.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 25 (3): 521–548.

- Harrison, C., I. Omeihe, A. Simba, and K. Omeihe. 2020. “Leading the way: The Entrepreneur or the Leader?” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 1–17. doi:10.1080/08276331.2020.1840853.

- Harrison, C., S. Paul, and K. Burnard. 2016a. “Entrepreneurial Leadership in Retail Pharmacy: Developing Economy Perspective.” Journal of Workplace Learning 28 (3): 150–167.

- Harrison, C., S. Paul, and K. Burnard. 2016b. “Entrepreneurial Leadership: A Systematic Literature Review.” International Review of Entrepreneurship 14 (2): 235–264.

- Hatch, M. 2013. The Maker Movement Manifesto: Rules for Innovation in the New World of Crafters, Hackers, and Tinkerers. UK: McGraw Hill Professional.

- Hecker, S., M. Haklay, A. Bowser, Z. Makuch, and J. Vogel. 2018. Citizen Science: Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy. London: UCL Press.

- Howard, M. D., W. Boeker, and J. L. Andrus. 2019. “The Spawning of Ecosystems: How Cohort Effects Benefit New Ventures.” Academy of Management Journal 62 (4): 1163–1193.

- Ireland, R. D., and M. A. Hitt. 1999. “Achieving and Maintaining Strategic Competitiveness in the 21stcentury: The Role of Strategic Leadership.” Academy of Management Perspectives 13 (1): 43–57.

- Kang, J. H., G. T. Solomon, and D. Y. Choi. 2015. “CEOs’ Leadership Styles and Managers’ Innovative Behaviour: Investigation of Intervening Effects in an Entrepreneurial Context.” Journal of Management Studies 52 (4): 531–554.

- Karol, R. A. 2015. “Leadership in the Context of Corporate Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Leadership Studies 8 (4): 30–34.

- Kempster, S., and J. Cope. 2010. “Learning to Lead in the Entrepreneurial Context.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 16 (1): 5–34.

- Khalil, A. S., and J. J. Collins. 2010. “Synthetic Biology: Applications Come of Age.” Nature Reviews Genetics 11 (5): 367–379.

- Koryak, O., K. F. Mole, A. Lockett, J. C. Hayton, D. Ucbasaran, and G. P. Hodgkinson. 2015. “Entrepreneurial Leadership, Capabilities and Firm Growth.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 33 (1): 89–105.

- Landrain, T., M. Meyer, A. M. Perez, and R. Sussan. 2013. “Do-it-Yourself Biology: Challenges and Promises for an Open Science and Technology Movement.” Systems and Synthetic Biology 7 (3): 115–126.

- Leitch, C. M., C. McMullan, and R. T. Harrison. 2009. “Leadership Development in SMEs: An Action Learning Approach.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 6 (3): 243–263.

- Leitch, C. M., C. McMullan, and R. T. Harrison. 2013. “The Development of Entrepreneurial Leadership: The Role of Human, Social and Institutional Capital.” British Journal of Management 24 (3): 347–366.

- Leitch, C. M., and T. Volery. 2017. “Entrepreneurial Leadership: Insights and Directions.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 35 (2): 147–156.

- Lumpkin, G. T., and G. G. Dess. 1996. “Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It to Performance.” Academy of Management Review 21 (1): 135–172.

- Martin, L. 2015. “The Promise of the Maker Movement for Education.” Journal of Pre-College Engineering Education Research (J-PEER) 5 (1): 4–4.

- Million-Perez, H. R. 2016. “Addressing Duel-use Technology in an Age of Bioterrorism: Patent Extensions to Inspire Companies Making Duel Use Technology to Create Accompanying Countermeasures.” AIPLA QJ 44: 387–387.

- Ngigi, S., D. McCormick, and P. Kamau. 2018. “Entrepreneurial Leadership Competencies in the 21st Century: An Empirical Assessment.” DBA Africa Management Review 8 (2): 1–17.

- Okudan, G. E., and S. E. Rzasa. 2006. “A Project-based Approach to Entrepreneurial Leadership Education.” Technovation 26 (2): 195–210.

- Omeihe, I., C. Harrison, A. Simba, and K. Omeihe. 2020. “The Role of the Entrepreneurial Leader: A Study of Nigerian SMEs.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business. https://www.inderscience.com/info/ingeneral/forthcoming.php?jcode=ijesb.

- Putsom, W., P. Suwannarat, and N. Songsrirote. 2019. “The Effect of Entrepreneurial Leadership, Value Creation and Automotive Parts Manufacturing Businesses Performance in Thailand.” Human Resource and Organization Development Journal 11 (2): 1–33.

- Revill, J., and C. Jefferson. 2014. “Tacit Knowledge and the Biological Weapons Regime.” Science and Public Policy 41 (5): 597–610.

- Sarpong, D., G. Ofosu, D. Botchie, and F. Clear. 2020. “Do-it-yourself (DiY) Science: The Proliferation, Relevance and Concerns.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 158: 120–127.

- Sarpong, D., and A. Rawal. 2020. “From the Open to DiY Laboratories: Managing Innovation Within and Outside the Firm.” In Innovating in the Open Lab: The New Potential for Interactive Value Creation Across Organizational Boundaries, 263–274. Germany: ISPIM.

- Seyfried, G., L. Pei, and M. Schmidt. 2014. “European do-it-Yourself (DIY) Biology: Beyond the Hope, Hype and Horror.” Bioessays 36 (6): 548–551.

- Sharifirad, M. S. 2013. “Transformational Leadership, Innovative Work Behavior, and Employee Well-being.” Global Business Perspectives 1 (3): 198–225.

- Simba, A., and M. T. T. Thai. 2019. “Advancing Entrepreneurial Leadership as a Practice in MSME Management and Development.” Journal of Small Business Management 57: 397–416.

- Songkünnatham, P. 2018. The parable of the poisoned arrow: Thailand. Retrieved on December. Vol.10, p.2018.

- Soriano, D. R., and J. M. C. Martínez. 2007. “Transmitting the Entrepreneurial Spirit to the Work Team in SMEs: The Importance of Leadership.” Management Decision 45 (7): 1102–1122.

- Stone, Z. 2015. The Maker Movement Is Taking Over America: Here’s How. US: The Hustle.

- Surie, G., and A. Ashley. 2008. “Integrating Pragmatism and Ethics in Entrepreneurial Leadership for Sustainable Value Creation.” Journal of Business Ethics 81 (1): 235–246.

- Swiercz, P. M., and S. R. Lydon. 2002. “Entrepreneurial Leadership in High-tech Firms: A Field Study.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 23 (7): 380–389.

- Tanenbaum, J. G., A. M. Williams, A. Desjardins, and K. Tanenbaum. 2013. “Democratizing Technology: Pleasure, Utility and Expressiveness in DIY and Maker Practice.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2013: 2603–2612.

- Thomas, A. S., and S. L. Mueller. 2000. “A Case for Comparative Entrepreneurship: Assessing the Relevance of Culture.” Journal of International Business Studies 31 (2): 287–301.

- Timmons, J. A. 1999. New Venture Creation: Entrepreneurship in the 21th Centuries. Homewood, IL: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

- Tung, F.-C., and T.-W. Yu. 2016. “Does Innovation Leadership Enhance Creativity in High-tech Industries?” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 37 (5): 579–592.

- Vecchio, R. P. 2003. “Entrepreneurship and Leadership: Common Trends and Common Threads.” Human Resource Management Review 13 (2): 303–327.

- Waldman, D. A., and B. M. Bass. 1991. “Transformational Leadership at Different Phases of the Innovation Process.” The Journal of High Technology Management Research 2 (2): 169–180.

- Wexler, A. 2016. “The Practices of do-it-Yourself Brain Stimulation: Implications for Ethical Considerations and Regulatory Proposals.” Journal of Medical Ethics 42 (4): 211–215.

- Wolinsky, H. 2005. “Do-it-Yourself Diagnosis: Despite Apprehension and Controversy, Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Tests Are Becoming More Popular.” EMBO Reports 6 (9): 805–807.

- Yoon, J., N. S. Vonortas, and S. Han. 2020. “Do-It-Yourself Laboratories and Attitude Toward Use: The Effects of Self-efficacy and the Perception of Security and Privacy.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 159: 120–192.

- You, W., W. Chen, M. Agyapong, and C. Mordi. 2020. “The Business Model of Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Laboratories – A Triple-layered Perspective.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 159 (December 2019): 120205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120205.