ABSTRACT

Strategic transformation is a driver for business model innovation. This study identifies key aspects and activities of business model innovation in a high-tech industry utilising strategic transformation. The study takes its departure in an aircraft engine manufacturer dominated by military products that evolves into a high-tech developing company competing on an open market. Findings support previous research on changes in the defence industry such as risk sharing, a need to identify core technologies, and the importance of efficiency related to profitability. The study contributes to a greater understanding of how business models develop under strategic transformation, and an understanding of the need for change and what capabilities are required to leave previous strategic development behind and undertake a new path to future development.

1. Introduction

The focus on business models is extensive in the literature, although definitions may vary (Foss and Saebi Citation2017; Wirtz et al. Citation2016). Foss and Saebi (Citation2017) state that ‘ … most current definitions are close to or consistent with Teece’s (Citation2010, 172) definition of BM as the “design or architecture of the value creation, delivery, and capture mechanisms” of a firm’ (Foss and Saebi Citation2017, 202). Thus, a business model constitutes ‘what the firm is and does’ (Mason and Spring Citation2011, 1039), and develops in interaction among actors at different levels (Mason and Spring Citation2011). However, there is ‘ … little knowledge of how firms adapt their business models in response to external threats and opportunities’ (Saebi, Lien, and Foss Citation2017, 567). Defence industry companies have for many years faced changes in government purchasing patterns and have been under pressure to adapt to changing business conditions. Collaborative projects offer one opportunity to make technology development affordable (Moravscik Citation1991). Consolidation is another long-term trend (DeVore Citation2015), including alliances, mergers, and acquisitions (Neal and Taylor Citation2001), downsizing, and diversification (Hartley and Sandler Citation2003). Therefore, a business model is ‘ … a consistent logical picture of how all the firm’s activities form a strategy’ (Richardson Citation2008, 143). Studying strategic transformation from a business model innovation perspective is therefore interesting (Demil and Lecocq Citation2010).

The defence industry has changed substantially over the past decades. A key aspect is that shrinking government spending, the traditional cost-plus model, has been replaced with more competitive market models (Dunne and Macdonald Citation2001). A market-oriented approach entails a broader range of customers through diversification and product support throughout product lifecycles or leasing alternatives (Hartley and Sandler Citation2003). This also leads to greater efficiency in product development and productivity (DeVore Citation2015), including using technologies and products developed for civil use also for military use and vice versa (Hartley and Sandler Citation2003). One consequence is that companies have moved ‘ … from being manufacturing companies … ’ (Dunne and Macdonald Citation2001, 14) to ‘ … specialise in technical niches … ’ (DeVore Citation2015, 572), resulting in a supply chain where end manufacturers have suppliers who are sub-suppliers specialised within specific niches. With increased globalisation, meeting new conditions and an ‘ … introduction of modern business practices’ (Hartley and Sandler Citation2003, 363), the defence industrial companies must adapt to other ways of interacting with other actors as well as acquire competence to strategically develop to this new and changing business environment, and reorientate their business over time (Tushman, Newman, and Romanelli Citation1986).

Changes in the business context have made strategic transformation necessary to review a company’s current strategic position to redefine the business itself and enable it to compete under new conditions (Pearce and Robbins Citation2008). The aim of this paper is to identify key aspects to business model innovation in a high-tech industry utilising strategic transformation to address changing business conditions. The empirical context is a high-tech industry where a company develops from a business model mainly related to defence material, to the opposite, where civil products dominate the business model. The study illustrates a transformation through business model innovation over time following strategic initiatives within the company.

The change is interesting from a theoretical perspective, where key challenges can be identified in applying strategy and business models (Pearce and Robbins Citation2008). This study fills a gap in the literature by taking a more business-oriented approach to change in a defence industry company’s strategic orientation. Theoretical implications add new insights into business model transformation of long-term changes in an industry with long product life cycles and lead times in product development and production processes. The study also has implications from a managerial perspective: understanding long-term change processes, identifying the need for change, and utilising this knowledge to develop the company (Linder and Cantrell Citation2001). The managerial implications emphasise the need for long-term strategic plans together with a profound understanding of change processes in addition to in-depth knowledge of competencies and capabilities to adapt to new industry prerequisites.

2. Strategic reorientation through strategic transformation

Strategic transformation describes how a company develops over time to adapt to its business environment. Strategic transformation can be divided into organic growth, acquisitions, or different forms of collaborative strategies (Pearce and Robbins Citation2008).

Organic growth implies that companies must develop resources and capabilities by self-financing in-house development or by exploiting existing capacities to gain larger market shares (Achtenhagen, Brunninge, and Melin Citation2017). Characteristic for organic growth is a lower degree of dependency on others and that it takes a longer time to pursue than acquisitions.

Strategic transformation through acquisitions takes various forms to reach synergies. Horizontal acquisitions characterise ‘more of the same’, a potential to achieve economies of scale through coordinated resources, and increased efficiency in production and procurement (Pearce and Robbins Citation2008). Vertical acquisition can be integration forward through control over the next stage in the value chain; or backward through increased control over input resources. Conglomerate acquisitions can appear in different forms (Pearce and Robbins Citation2008): market extension that integrates companies with similar products but extends geographical markets; product extension that integrates companies on the same markets with related products; and a pure conglomerate that is unrelated to either products or markets.

Collaborative strategies ‘ … enable a firm to leverage its resources with those of its partners’ (Pearce and Robbins Citation2008, 126), which means that collaborations are in between ‘growth by yourself’ and ‘growth by acquisitions’. Therefore, contractual arrangements between the involved actors are necessary, although such agreements often are incomplete, and the actors must rely on trust (Das and Teng Citation2000). The degree of formal contractual arrangements can vary from joint ventures to strategic alliances (Pearce and Robbins Citation2008).

We use the concept of collaborations in a broader sense including strategic alliances (Barringer and Harrison Citation2000). Strategic alliances are formed with the intention of accessing other companies’ resources for increased utilisation of joint resources (Das and Teng Citation2000). The most common strategic alliances are technological or marketing alliances (Barringer and Harrison Citation2000). Technological alliances focus on R&D, manufacturing, and engineering activities for the purpose of ‘ … cost and risk sharing, product development, learning and increased speed to market’ (Barringer and Harrison Citation2000, 391). Marketing alliances focus on distribution channels to reach more customers (Barringer and Harrison Citation2000). The importance of strategic alliances is the aspect of learning, which results in the development of new knowledge when it is internalised within the company (Das and Teng Citation2000). Such new knowledge can benefit the company’s customers if the value proposition can be developed through collaborative agreements. To understand the process of adaptation, it is useful to recognise how such changes can have implications for the business model under which the company performs.

3. Business model innovation and strategic transformation

The dynamics of business model innovation is typically discussed in the literature as evolution, renewal, replication, learning, erosion, and lifecycle, all which describe change over time (Saebi, Lien, and Foss Citation2017). Other concepts, such as transformation and innovation, reflect more disruptive changes in market settings (Saebi, Lien, and Foss Citation2017). Thus, changes to business models are an adaptation to the business environment. The dynamics between business model components is vital to understand the consequences of strategic transformation for business model innovation (Demil and Lecocq Citation2010). Change is complex by nature (Greenwood and Hinings Citation1998), and the analysis of business model innovation across three strategic transformation constructs is important to understand the key challenges linked to this process. Change in this study is illustrated by the paths of a single entity’s change process following the emergent development of change.

The core components of a business model can be divided into more or less detailed fractions (Saebi, Lien, and Foss Citation2017), where Chesbrough (Citation2007) forwards a well-known framework for building business models around six elements: value proposition, market segment, value chain structure, streams of cost and revenues, value network position, and competitive strategy. This paper applies these elements as core components to analyse business model innovation under strategic transformation. We do not intend to discuss business model constituents (Aspara et al. Citation2013) but rather how strategic transformation affects various parts of a business model. A dynamic view of business model components (Demil and Lecocq Citation2010) produces the characteristics of business model architectural change under strategic transformation, see .

Table 1. Business model components and architectural change under strategic transformation.

Understanding the customer is necessary to be able to develop value proposition differentiators in comparison with competitors (Demil and Lecocq Citation2010). A dynamic value proposition relies on an understanding of underlying business conditions to utilise the benefits of strategic transformation. When a target market changes, the need to target new market segments is necessary (Foss and Saebi Citation2017), which is reflected through strategic transformation, e.g. via new markets, adding service through acquisition, or developing a niche or technology in cooperation with partners.

Value chain structure changes means that companies make ‘ … their value chains more elastic’ (Gottfredson, Puryear, and Philips Citation2005, 132). This affects how sourcing is organised on the supply side (Gottfredson, Puryear, and Philips Citation2005) and entails addressing new market segments (Chesbrough Citation2007) to develop a service organisation to support customers in extended offerings, which requires a resource base to organise and develop customer relationships (Kindström Citation2010). The company’s access to resources within the value chain for value creation is important (Teece, Citation2010). One strategic choice is therefore which activities to do and how they should be done (Gottfredson, Puryear, and Philips Citation2005). Changes can be achieved through strategic transformation with acquisitions along the value chain, collaboration with partners to position the company within a niche, or the organic growth of niche strategies.

Changes in revenue mechanisms entail the need to understand cost structure and cost drivers, and if changes in revenue mechanisms effect the distribution of risk. Changes in revenue mechanisms also involve pricing structure (Giesen et al. Citation2007) and what a customer is willing to pay (Mason and Spring Citation2011). Customer expectations can range from free basic services, to models with low-priced products together with higher price levels on aftermarket services (Teece, Citation2010). Revenue mechanisms under strategic transformation change through a diversified product base, broadened service, and maintenance by means acquisitions, or in collaborative activities through revenue-risk-sharing.

The value network includes external stakeholders’ relationships, and changes in the value network affect current relationships or trigger the development of new relationships (Demil and Lecocq Citation2010; Chesbrough Citation2007; Koen, Bertels, and Elsum Citation2011). These changes include the coordination of different actors and develop the value network to uncover the potential of other actors (Kindström Citation2010). Strategic transformation develops the value network differently; organic growth expands existing products to other markets. Acquisitions build a broader value-creating network with increased service-related businesses. Collaboration gives access to resources and contributes with knowledge within own relevant areas for increased opportunities.

Competitive strategy is the plan for how the business model components differentiate the company from its competitors (Chesbrough Citation2007; Teece, Citation2010). Changes in competitive strategies are delicate and should be pursued slowly through well-established customers (Kindström Citation2010). Understanding the business environment is also important for the company’s ability to manage change to remain competitive (Chesbrough Citation2007; Giesen et al. Citation2007) and to understand the potential of collaborative activities (Neu and Brown Citation2008) to facilitate competitive advantage through strategic transformation.

4. Method

The case study originates from a multi-year research programme focusing on the aeronautic industry. One objective of the programme was to study the role of system suppliers. Alfa, one of the companies in the programme, provided insights into strategic transformation over a long period with the opportunity to understand business processes (Siggelkow Citation2007) and the company’s transformation from one organisational archetype to another (Greenwood and Hinings Citation1998). A single case study offers the opportunity to study embedded events in a complex and changing context (Halinen, Törnroos, and Elo Citation2013) with the aim of gaining insight into a particular situation (Yin Citation2018). This approach provides both managerial and academic insights (Gibbert, Ruigrok, and Wicki Citation2008) into how a company utilises various development paths to adapt to changing industry conditions. Using Alfa for this purpose was threefold: the company provides insights into changes for long-term survival over a long period; it offers the opportunity to analyse different types of strategic transformations; and the company gives perspectives on changes in a high-tech industry.

4.1. The case

Alfa’s company management wanted to decrease the company’s dependence on military products. Diversification became one way to decrease vulnerability to industry changes. In the 1950s, a reduced need for military products led to a production of diesel engines for trucks that utilised current workforce and workshops. This strategy was abandoned when the production of aircraft engines required increased capacity. Alfa later expanded by acquiring the development and production of printing equipment. However, this business was later sold. This background shows that Alfa made efforts early on to avoid being too dependent on a narrow product range. The background also indicates that the company was not ready to reorientate its business.

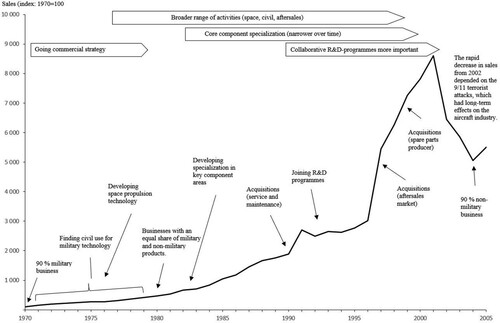

Long-term strategic plans had been a part of Alfa’s development since the mid-1950s, but it was not until under new ownership in the early 1970s that greater focus was on decreasing dependence on one single customer. gives a broad overview of the transformation from 90% military-related business towards 90% non-military business. Details in are discussed below in section five that analyse business model development under strategic transformation.

4.2. The research process

The context of the study is a single case from the defence industry sector illustrating key challenges of business model innovation under strategic transformation. The study is longitudinal with data collected retrospectively (Halinen, Törnroos, and Elo Citation2013), and data were mainly collected through interviews with Alfa representatives. Other material, such as company documents and annual reports, was used to understand the development and context of the company. Respondents to 10 interviews included key individuals with in-depth knowledge of Alfa’s development over the studied period, especially the director of R&D, the deputy CEO, and the director of production. Interviews were also conducted with the director of strategic planning and corporate strategy, the marketing director for new products, the director of strategy and technology management, the director of EU R&D, a manager from strategy and corporate development, and a purchasing manager. They had, to various extents, the potential to influence the company’s strategic development from their different positions (Siggelkow Citation2007). The interviews were semi-structured following an inquiry guide with the objective of covering central themes (Yin Citation2018); introduction and general information, change processes, customers, suppliers, competitors and market conditions, industry structure, business opportunities, future demand and supply, and time-related issues interrelated with the changes pursued. The interviews were recorded and transcribed to facilitate review and analysis (Gibbert, Ruigrok, and Wicki Citation2008).

The case was analysed by identifying and coding significant elements of the continuous development of the company’s business model. In this manner, uniting ‘ … theory with the empirical world’ (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002, 555) formed a base for analysing the case. The data were analysed by iterating relevant theories to cover the studied processes to be able to sharpen and develop the argument presented herein, starting with an initial understanding of the studied company, the specific industry, and its context.

5. Business model innovation through strategic transformation

Alfa had to address various business model components through strategic transformation to be able to create and capture value under changing business conditions. summarises major defence industry trends, and provides an overview of the key aspects of strategic transformation necessary to develop business model components, and it has links to the major trends described in . This will further be elaborated on in subsequent sections.

Table 2. Major defence industry trends.

Table 3. Business model innovation through strategic transformation.

5.1. Value proposition development

5.1.1. Value propositions and organic growth

Alfa initiated a civil-market programme, going commercial in the 1970s, using organic growth by finding civil use for military technology. One example was the hydraulic pumps and engines that were used in trucks, forest machines, and offshore winches, initiated in the 1960s, developed in the coming decades, and divested in the 1990s. Another example was heaters for cars, boats, and work vehicles, which were derived from Alfa’s knowledge of combustion technology. This production started in the late 1970s and was divested in 1997.

Alfa also expanded organically closer to its core business. During discussions on a new fighter aircraft for the Swedish Airforce in the late 1970s, Alfa had the intention of developing business related to civil aviation. Even though this fighter aircraft project did not materialise, Alfa’s intention led to participation in the development of three civil aircraft engines together with a major aircraft engine producer. In the beginning of the 1980s, the Swedish government decided to develop a new fighter aircraft. Alfa pursued the same strategy; a few civil projects that equalled the number of military projects in terms of product development. Alfa’s customer also wanted to change to more products for civil use but needed partners to share product development and financial risks. Alfa became a supplier to one of the most sold jet engines for passenger jetliners. Alfa’s willingness to participate in product development projects was important in its effort to balance military products with civilian products. Alfa not only strengthened its relationship with its customer but also with its customer’s customer, as Alfa could fulfil a broader range of needs.

Alfa was also involved in space propulsion, an area closely related to aircraft engine technology, from the mid-1970s. Alfa had acquired production technology and capabilities by being a supplier of components to the European space programme. Alfa was a components producer in the early space programmes, but it became more of a developer of space propulsion technology in the later programmes (1980–1990s).

5.1.2. Value propositions and acquisitions

Alfa acquired service and maintenance companies in its transformation towards more civilian products. Alfa had organically developed its business within aircraft engine overhaul since the 1960s and had also acquired an aircraft engine overhaul workshop by the end of the 1980s. The civilian business was further strengthened through a jointly owned company with an airline company in which Alfa increased its ownership from 25% to 90% over a period of four years in the early 1990s.

Alfa also acquired a component producer for civil-aircraft engines in the 1990s. At that time, Alfa became involved in all the military- and civil-aircraft engine programmes in the western world. This enabled Alfa to establish contacts with new end-customers with whom to build future relationships. Alfa reached an agreement with Boeing in the late 1990s to handle the whole market for spare parts for the Boeing aircraft in use but no longer in production.

The acquisitions strengthened Alfa; the range of activities related to aircraft engines along the value chain from production to service increased. Service and maintenance increased in importance over time to become one of the major businesses of the company. With the inclusion of spare-parts sales at Alfa, capital tied up in inventory could be reduced, and the necessary spare parts were still delivered in time.

5.1.3. Value propositions and collaborations

Developing value propositions through collaboration can be illustrated with specialisation within certain areas of technology. Alfa became specialised in key components, such as complex structures and rotating engine components, from the beginning of the 1980s during the development of the new fighter aircraft engine for the Swedish Airforce. Limited resources, financial and competences, further narrowed the specialisation areas from initially five to three. The advantage with specialisation, relying on highly skilled resources, is that it creates a niche.

Developing a niche can create a position in which an actor becomes a necessary partner for quality reasons or development capabilities. This specialisation led to the possibility for Alfa to join European aircraft research programmes in the 1990s. An overall trend in the industry was increased concentration that meant fewer actors specialised in various niches. For aircraft producers, this meant that these specialised companies had to cooperate closer to develop a new aircraft.

Costly development of armament products has made it necessary for companies to collaborate. Aircraft producers require partners for long-term relationships, and sharing financial risks means that a sub-supplier must have a long-term view on their relationship for a return on the investment made. Strategically this meant that a company had to develop a specialised niche funded on its own. This emerged by the end of 1970s with the introduction of new engines for passenger jetliners. Payment came later when the aircrafts were sold. The strategic transformation developed the value proposition with a decreased dependence on one single customer for a more diverse customer base.

5.2. New target markets

Alfa found new markets and customers through early attempts at organic growth. The hydraulic pumps and engines were used in trucks, forest machines, and offshore winches, and the heaters attracted producers of cars, boats, and work vehicles and created a customer base outside the military sphere. The strategy for more civilian products strengthened the company’s relationship with engine producers since they also had customers on the commercial market. These opportunities expanded to include more customers in the space programmes from the mid-1970s. Thus, a value proposition expanded Alfa’s customer base to include new customers on different markets developed through organic growth.

Through the acquisitions in service, maintenance, and spare parts during the 1980s, Alfa managed to strengthen its relationships on the civilian market and reach a broader range of customers. This type of business increased in significance for Alfa. The acquisitions Alfa made in engine maintenance were a consolidation and implied a stronger relationship to both civilian and military customers. Alfa became a producer of parts and components for almost all military- and civil-aircraft engines produced in the western world through its acquisition of the spare parts producer in the 1990s.

The collaborative engagements in technology development research programmes strengthened Alfa in their areas of specialisation from the 1980s and into the 1990s. Reasons to participate in research programmes were twofold: develop new knowledge to implement in current and future product development; and to build trust with other participating organisations for the next aircraft engine programme. The importance of collaborative initiatives has increased over time. Product development has become more expensive, meaning that collaboration with others is necessary to finance development, share risks, and gain access to relevant knowledge.

5.3. Value chain changes

Its specialisation of technologies changed Alfa’s position in the value chain, a shift from having abilities within all aircraft engine technologies to becoming a specialised sub-supplier. This was a strategic choice made in the early 1970s and meant a narrower and more specialised resource base. However, specialisation made the value chain more elastic on the customer side, and Alfa gained a more diversified customer base through these developed relationships.

The acquisitions made by Alfa over the years changed its position in the value chain and made it more elastic through addressing new market segments. The acquired businesses within service, maintenance, spare parts distribution, and aircraft engine parts production changed and strengthened Alfa’s position in relation to its current and future customers. The customer base became broader with customers along the value chain following the product lifecycle.

Changes in the value chain from collaborative activities strengthened Alfa’s relationship with its customers through specialised technological areas. Alfa was able to focus on fewer areas for technological development through collaborations. Thus, Alfa took a position in these specialised areas to capture value and to better fulfil customer expectations by being more competent within selective technological areas.

5.4. New revenue mechanisms

The strategic transformation influenced Alfa’s revenue mechanisms. Organic growth created a diversified customer base. The revenue streams came from other types of customers than government procurement, including civil-aircraft producers and space-engine programmes developed over time from the early 1970s. In this manner, Alfa developed methods for generating revenues through organic growth. This challenged the management mindset of how business had traditionally been conducted.

The acquisitions made during the 1980s and 1990s developed revenue mechanisms by adding more types of businesses. Acquiring companies along the value chain means that revenues come from more than selling products. Selling spare parts extends revenue streams throughout a product lifecycle. Changing the business structure influences revenue potential. The acquisitions broadened the scope of revenue streams for Alfa through new revenue-generating mechanisms.

The collaboration initiatives starting in the late 1970s changed the revenue streams. Alfa had to increase its level of self-financing and wait for revenues until its customers had sold its products. This was a change from being a cost-plus business to financing own participation and payment until the sale of the products.

5.5. Value network development

Value network changes are broader than value chain changes. Relationships originally centred around defence material procurement agencies, are affected by the industry change to include international networks of suppliers, customers, and technology developers. The organic growth path for Alfa’s value network development involved joint research programmes from the early 1990s funded by the companies themselves, the European Union, and a network of aircraft technology producers. Organic growth within space technology followed the path of value proposition development through production to technology development. A company’s importance grows in the value network owing to its increase in new knowledge and capabilities.

The acquisitions of service and maintenance and later aftersales during the 1980s and 1990s created a different position for Alfa in its value network. The company gained a broader range of potential contacts to work with to create future business. Not only did aircraft engine producers and aircraft producers become more important but also the airline companies gained in importance. Thus, Alfa developed a network to fulfil customer needs.

Alfa’s value network developed through collaborative activities such as the European Commission supported aeronautics research programmes. Such programmes typically involved several industry actors to develop and support an industry’s competitiveness. Thus, a company gains in value network through such collaboration activities. There is potential for the involved companies to take an integrative role when it comes to each company’s specialisation because the industry is rather specialised.

5.6. Competitive strategy development

Business model design differentiates a company from its competitors in strategic development, and Alfa developed its competitive advantages through strategic transformation. Organic growth developed the company from a component producer in the early European space programmes from the 1970s to an actor able to develop advanced technology by the 1990s. Technology development led to increased value-added activities beyond component production. Alfa developed a differentiated product programme through learning and product development.

Alfa developed its competitive strategy by expanding into service and maintenance and the aftersales market through acquisitions. Diversification to a more service-oriented business model developed the company’s competitive strategy including activities along the value chain. Alfa added business to its original activities and broadened its scope. This expansion created advantages such as increased customer contacts on different levels in customer companies along the value chain from the production of aircraft engines, service, and maintenance to the aftersales market.

Collaboration at Alfa meant participation in technology development programmes. This gave Alfa a competitive advantage since only a limited number of actors can be experts within each narrow technological area due to complexity and increasing development costs. One trend is that military and civil product development follow each other closely, which implies that the latest product developed also has the latest technology. This makes collaboration between different actors important.

6. Discussion and conclusions

The aim of this paper was to contribute to our understanding of business model innovation over time through the identification of the key aspects of business model innovation that address changing business conditions and strategic transformation. Key aspects of business model innovation in a high-tech industry have been identified by others (Teece, Citation2010). The studied company faced strategic transformation including organic growth, acquisitions, and collaborations in parallel. The industry specifics, with long product development times, long product life cycles, and a traditional relationship between government purchasing of armament products, and the producers, makes planning for and implementing changes a challenge. This paper gives insights into how to strategically develop a company under such conditions. Key aspects of business model innovation under strategic transformation were identified together with activities to consider in the analysis of business model components, see .

Table 4. Key aspects of business model innovation under strategic transformation.

We identified six characteristics of the changing defence industry derived from the activities and key aspects presented in . The first characteristic has to do with the importance of insights into ongoing changes and trends within the industry (DeVore Citation2015; Neal and Taylor Citation2001; Moravscik Citation1991). This is shown in the studied company through several decisions related to finding new customers (Hartley and Sandler Citation2003), by turning in-house technologies into commercial products and, by narrowing the scope of its business to fewer core technologies. This was done in parallel with acquiring businesses that extended the company’s value chain and broadened its value network. A second characteristic concerns changing business conditions. The transformation to focus a broader range of customers and a change from the cost-plus system to a more market-oriented system made significant change to the conditions under which businesses are made.

The shift from the cost-plus system added a third characteristic, risk sharing, which requires a financially stable company for a long-term commitment (Giesen et al. Citation2007; Mason and Spring Citation2011; Barringer and Harrison Citation2000). This step leads to an interest in distributing risk further down the value chain to involve sub-suppliers. This has major obstacles, however, if the sub-suppliers are relatively small companies with limited resources to finance a ‘what if’-type of business. Fourth, a greater focus on profitability and efficiency became important (DeVore Citation2015). Efficiency and capabilities in product development and production are important to consider in terms of increasing cost for product development. Profitability is also important in terms of potential income in relation to the cost structure for development and running costs.

Fifth, developing customer relationships emerged as an important characteristic, but it is challenging at the same time (Hartley and Sandler Citation2003; Wirtz et al. Citation2016; Kindström Citation2010). The study identified three specific attributes: participation in research programmes developing own specific technologies, contribute development resources in co-operation with the customer for product development, and focus on understanding customer needs. Finally, a sixth characteristic concerns technological areas. Technological development is costly and increasingly competitive (DeVore Citation2015); companies must make strategic choices on what to consider as core technologies that they can develop to maintain a superior competitive edge (Chesbrough Citation2007; Teece, Citation2010).

Related to the processes identified by DeVore (Citation2015) this study found that companies in the defence industry are under pressure due to rising costs, more globalised supply chains, increased industry concentration, and changing procurement patterns (Dunne and Macdonald Citation2001). This pressure includes difficult challenges such as the need to restructure. There are also opportunities such as gaining greater expertise within certain technological areas. From a managerial perspective, it is important that management has broad abilities to understand strategic and contextual change and the impact this change has on the company and on the industry in general. Further, the study also emphasises that changes take time to implement given industry-specific conditions (Greenwood and Hinings Citation1998). The field could benefit from further in-depth studies including R&D, new technological areas, types of capabilities currently needed, combined with what future capabilities will be required to participate in future industry changes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Johan Holtström

Johan Holtström is an assistant professor in Industrial Marketing at Linköping University. He received his Ph.D. from Linköping University. His research interest is in the field of mergers and acquisitions, synergies, business model innovation and strategy. He has previously published in Journal of Business Research, Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing and Journal of Strategy and Management.

References

- Achtenhagen, L., O. Brunninge, and L. Melin. 2017. “Patterns of Dynamic Growth in Medium-Sized Companies: Beyond the Dichotomy of Organic Versus Acquired Growth.” Long Range Planning 50: 457–471.

- Aspara, J., J.-A. Lamberg, A. Laukia, and H. Tikkanen. 2013. “Corporate Business Model Transformation and Inter-Organizational Cognition: The Case of Nokia.” Long Range Planning 46: 459–474.

- Barringer, B. R., and J. S. Harrison. 2000. “Walking a Tightrope: Creating Value Through Interorganizational Relationships.” Journal of Management 26 (3): 367–403.

- Chesbrough, H. 2007. “Business Model Innovation: It’s Not Just About Technology Anymore.” Strategy and Leadership 35 (6): 12–17.

- Das, T. K., and B.-S. Teng. 2000. “A Resource-Based Theory of Strategic Alliances.” Journal of Management 26 (1): 31–61.

- Demil, B., and X. Lecocq. 2010. “Business Model Evaluation: In Search of Dynamic Consistency.” Long Range Planning 43: 227–246.

- DeVore, M. R. 2015. “Defying Convergence: Globalisation and Varieties of Defence-Industrial Capitalism.” New Political Economy 20 (4): 569–593.

- Dubois, A., and L.-E. Gadde. 2002. “Systematic Combining: an Abductive Approach to Research.” Journal of Business Research 55 (7): 553–560.

- Dunne, P., and G. Macdonald. 2001. “Procurement in the Post Cold War World: A Case Study of the UK.” Accessed 13 February 2019. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266095082_Procurement_in_the_Post_Cold_War_World_A_Case_Study_of_the_UK.

- Foss, N., and T. Saebi. 2017. “Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation: How Far Have We Come, and Where Should We Go.” Journal of Management 43 (1): 200–227.

- Gibbert, M., W. Ruigrok, and B. Wicki. 2008. “Research Notes and Commentaries: What Passes as a Rigorous Case Study?” Strategic Management Journal 29 (13): 1465–1474.

- Giesen, E., S. J. Berman, R. Bell, and A. Blitz. 2007. “Three Ways to Successfully Innovate Your Business Model.” Strategy & Leadership 35 (6): 27–33.

- Gottfredson, M., R. Puryear, and S. Philips. 2005. “Strategic Sourcing – From Periphery to the Core.” Harvard Business Review, 132–139, February.

- Greenwood, R., and C. R. Hinings. 1998. “Orgaizational Design Types, Tracks and the Dynamics of Strategic Change.” Organization Studies 9 (3): 293–316.

- Halinen, A., J-Å Törnroos, and M. Elo. 2013. “Network Process Analysis: An Event-Based Approach to Study Business Network Dynamics.” Industrial Marketing Management 42: 1213–1222.

- Hartley, K., and T. Sandler. 2003. “The Future of the Defence Firm.” Kyklos 56 (3): 361–380.

- Kindström, D. 2010. “Towards a Service-based Business Model – Key Aspects for Future Competitive Advantage.” European Management Journal 28: 479–490.

- Koen, P. A., H. M. J. Bertels, and I. R. Elsum. 2011. “The Three Faces of Business Model Innovation: Challenges for Established Firms.” Research-Technology Management 54 (3): 52–59.

- Linder, J., and S. Cantrell. 2001. “Five Business-Model Myths that Hold Companies Back.” Strategy & Leadership 29 (6): 13–18.

- Mason, K., and M. Spring. 2011. “The Sites and Practices of Business Models.” Industrial Marketing Management 40 (6): 1032–1041.

- Moravscik, A. 1991. “Arms and Autarky in Modern European History.” Daedalus 120 (4): 23–45.

- Neal, D., and T. Taylor. 2001. “Globalisation in the Defence Industry: An Exploration of the Paradigm for US and European Defence Firms and the Implications for Being Global Players.” Defence and Peace Economics 12 (4): 337–338.

- Neu, W., and S. Brown. 2008. “Manufacturers Forming Successful Complex Business Services: Designing an Organization to Fit the Market.” International Journal of Service Industry Management 19 (2): 232–251.

- Pearce, J. A., and D. K. Robbins. 2008. “Strategic Transformation as the Essential Last Step in the Process of Business Turnaround.” Business Horizons 51: 121–130.

- Richardson, J. 2008. “The Business Model: And Integrative Framework for Strategy Execution.” Strategic Change 17: 133–144.

- Saebi, T., L. Lien, and N. Foss. 2017. “What Drives Business Model Adaptation? The Impact of Opportunities, Threats and Strategic Orientation.” Long Range Planning 50: 567–581.

- Siggelkow, N. 2007. “Persuasion with Case Studies.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (1): 20–24.

- Teece, D. J. 2010. “Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation.” Long Range Planning 43: 172–194.

- Tushman, M. L., W. H. Newman, and E. Romanelli. 1986. “Convergence and Upheaval: Managing the Unsteady Pace of Organizational Evolution.” California Management Review 29 (1): 29–44.

- Wirtz, B. W., A. Pistoia, S. Ullrich, and V. Göttel. 2016. “Business Models: Origin, Development and Future Research Perspectives.” Long Range Planning 49: 36–54.

- Yin, R. K. 2018. “Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods.” Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.