ABSTRACT

Power issues are increasingly important for effective management in the networked business landscape. This article seeks to increase understanding of the power within buyer-supplier relationships. This study articulates a research framework that defines countervailing and contextual events as the drivers of relationship power dynamics on structural and behavioural power dimensions. This framework is implemented in two illustrative, longitudinal case studies of technology-intensive buyer-supplier dyads in the medical sector. For this focal study, the illustrative case studies provide a basis for exemplifying the interconnection of behavioural and structural power and actors’ perceptions thereof for articulating a perceptions-based framework. The key ideas of this framework are exemplified by a set of propositions and research questions that comprise an agenda for further research. This study contributes by introducing a holistic approach to the study of power dynamics in business relationships. For practitioners, the study explicates elements and principles for managing power in business relationships.

1. Introduction

The concept of power is deeply rooted in various streams of academic discourse. In terms of business relationships, the general focus of research has been on capturing how power shapes inter-organisational interaction and steers relationship development (Cowan, Paswan, and Van Steenburg Citation2015; Doorn, Raven, and Royakkers Citation2011). However, long-standing research on power in business relationships lacks a coherent picture of this concept and its role in buyer-supplier relationships (see, e.g. Hingley, Angell, and Campelo Citation2015). Integrative (see, e.g. Meehan and Wright Citation2012) and dynamic presentations, such as those by Lacoste and Johnsen (Citation2015), Pérez and Cambra-Fierro (Citation2015) or Oukes, von Raesfeld, and Groen (Citation2019), represent a scant minority. The global market environment demonstrates the importance of understanding and explicating power in relationships and ecosystems of various types. A parallel exists between the geopolitical status quo being questioned (e.g. the rise of Russia, China, and, more recently, Turkey) and the dynamics within global supply chains (e.g. Huawei and Alibaba). These changes have become prominent through the attention received from international broadcasting and social media, however only the effects of these changes are discussed. The rise of new powers from China was made possible by applying wide-ranging and centralised strategies that were embedded in the local mindset, but there is no proof that such global supply chain dynamics are specific to East Asian companies. Similar tensions can be expected in business relationships throughout many industries on various scales, and explaining these changes can increase knowledge of business-to-business power dynamics.

This article seeks to increase understanding of power dynamics in buyer-supplier relationships. Accordingly, we set two research questions. 1) What are the key elements of power dynamics in buyer-supplier relationships? 2) How do actor perceptions mediate the effects of these elements on power dynamics in buyer-supplier relationships?

The study builds and contributes to the literature on power and power dynamics in business relationships (see, e.g. Oukes, von Raesfeld, and Groen Citation2019; Lacoste and Johnsen Citation2015; Talay, Oxborrow, and Brindley Citation2020; Handley and Benton Citation2012; Munksgaard, Johnsen, and Patterson Citation2015). Previous research primarily depicts power dynamics as one-dimensional changes in structural power (i.e. potential to exercise power; see Oukes, von Raesfeld, and Groen Citation2019). Furthermore, research on business relationships’ power dynamics fail to focus on changes in behavioural power (i.e. intensity of using power). The study provides a two-dimensional perspective synthesising behavioural and structural power into a framework demonstrated by illustrative case research (see Yin Citation2009; Buganza, Trabucchi, and Pellizzoni Citation2020). It presents two longitudinal, dyadic buyer-supplier relationships that feature a balancing shift in power asymmetry over time. These cases feature technology-intensive buyer-supplier relationships in the medical sector, where a technology manufacturer supplies international distributors with orthopaedic surgery instruments and solutions for public and private hospitals. These cases enable recognition and discussion of behavioural and structural power elements. This is used to build a perceptions-based framework and articulate sets of propositions and research questions. This assists in proposing an agenda for further research and guiding managers in assessing and managing the elements of power asymmetry, increasing the value creation potential of key relationships.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Power in business relationships

Prior literature widely considers power as a function of dependency between parties (Meehan and Wright Citation2012; Ratinen and Lund Citation2016). It has chiefly adopted a focus on either the structural or the behavioural side of power (Meehan and Wright Citation2012). Structural power refers to structural elements that grant the power source the capacity for power behaviours (i.e. to use the power; Oukes, von Raesfeld, and Groen Citation2019), and actor dependency claims potential power (French and Raven Citation1959). In a business relationship, both actors are somewhat dependent on each other; dependency is difficult to determine as net dependence (i.e. the difference between the dependencies; Provan Citation1980), as the idea of net dependence fails to communicate whether both actors have significant or minor dependence on each other. This prevents the evaluation of potential substitutes for the relationships’ parties, which may be various in the case of minor dependencies and marginal in the case of extensive dependencies. The structural power of each actor is important to consider separately and cannot be replaced by the net structural power consideration.

The behavioural perspective on power includes activities of countervailing power to create power dynamics (i.e. to balance the power asymmetry; Lacoste and Johnsen Citation2015; Talay, Oxborrow, and Brindley Citation2020; Handley and Benton Citation2012; Munksgaard, Johnsen, and Patterson Citation2015). Additionally, explicitly countervailing power actions, dynamics within the relationship or in the wider business network, may pose changes on these elements, specifically concerning how actors perceive each other’s resources and opportunities outside the relationship, and thus the dependence that merits structural power (Håkansson et al. Citation2009). This view is widely acknowledged in research on industrial relationships, where power is treated as embedded within a set of direct and indirect influences (Lacoste and Johnsen Citation2015) and may be out of reach for the relationship parties’ direct management actions. In this regard, power is a relativistic concept; it partly relates to the objective differences in both the power source and power target attributes (see Lacoste and Johnsen Citation2015) as well as both parties’ subjective perceptions and actions (Oukes, von Raesfeld, and Groen Citation2019).

The role of technology in business relationships may greatly associate with relationship functionalities and power (Pagani and Pardo Citation2017). Functionalities that technology offers the buyer may be largely at the mercy of the technology supplier. Information asymmetry exists between the technology supplier and the buyer regarding where the technological development is heading and what the cutting edge level of performance is; considering this, assumptions and beliefs regarding technology may play a large role in the business relationship and engagement with power (Makkonen and Vuori Citation2014). The social construction of technology in the relationship may comprise a strong element shaping the division of power in the relationship, affecting how the actors perceive the other elements that grant them structural and behavioural power (Pinch and Bijker Citation1984). Furthermore, technology or the technological frame of the relationship (i.e. socio-technical elements that steer actors’ sense-making and behaviours) may comprise a dominant share in the relationship among other power-related relationship elements, such as contracts, social bonds of trust and commitment associated with actors’ micro-political power strategies in interactions (see New Citation2004). The focal study aims to be inclusive of this socio-constructive nature of technology and its association with power. It seeks to provide a perspective that underlines the fast changing landscape of business relationships and networks of today with potential to grasp multi-level realities comprising a mixture of structure-action and intangible perceptions – tangible artefacts. For this reason, the following section posits our study on the concept of events, as business relationship events and actors’ perceptions of them are key in understanding structural and behavioural power in buyer-supplier relationships.

2.2. Theoretical framework

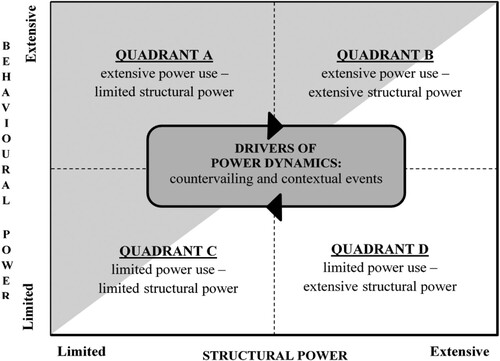

illustrates a theoretical framework focusing on the interplay between behavioural power and structural power (see Oukes, von Raesfeld, and Groen Citation2019; Meehan and Wright Citation2012). Behavioural power (i.e. power use) realises the potential of structural power (Oukes, von Raesfeld, and Groen Citation2019). The focal study abandons the tight linear connection between structural power and behavioural power by conceptualising overpowering and underpowering. The dark-shaded triangle at the upper part of the framework represents an area of overpowering, where the use of power exceeds the actor’s existing structural power. Concerning a particular action or event in the short term, an actor may be able to use power that exceeds its actual structural power (see Plouffe et al. Citation2016; Provan Citation1980). The light-shaded triangle represents an area of underpowering, where the use of power is lower than the potential for structural power. These asymmetries in structural and behavioural power may be enabled by the parties’ restricted or biased perceptions of their own structural power and that of the other actor (Rutherford and Holmes Citation2008).

Previous research has largely focused on structural power dynamics, while literature concerning behavioural power dynamics (i.e. how power use alters in the relationship) is non-existent. To articulate a balanced consideration, the framework defines power dynamics as a function of changes in both structural and behavioural power. Existing literature defines power dynamics largely as countervailing power (i.e. actors’ purposeful actions to alter the relationship’s structural power) (see Oukes, von Raesfeld, and Groen Citation2019; Lacoste and Johnsen Citation2015; Siemieniako and Mitręga Citation2018; Habib, Bastl, and Pilbeam Citation2015; Nyaga et al. Citation2013). However, Makkonen, Aarikka-Stenroos, and Olkkonen (Citation2012) categorise business relationship events into unpurposive events befalling actors and intentional, active events that actors complete. We use this categorisation to differentiate countervailing and contextual events. Countervailing events comprise activities that the actors purposefully undertake to cause power dynamics, whereas contextual events are actions and episodes that occur in the context (i.e. at the organisations, in the relationship or in the operating environments of actors) and cast their unintentional influence on structural and behavioural power in a relationship (see Makkonen, Aarikka-Stenroos, and Olkkonen Citation2012).

The central panel of the framework depicts countervailing and contextual events as the drivers of power dynamics. Accordingly, the framework builds a holistic perspective considering power as a function of structural and behavioural power and power dynamics driven by countervailing and contextual events. Articulating these dimensions as the framework’s cornerstones facilitates the explication of the widely-shared idea that power is a complex, dynamic phenomenon strongly based on the perspectives of business partners and embedded within a set of direct and indirect influences (Lacoste and Johnsen Citation2015).

3. Research methodology

3.1. Illustrative case study approach

This study uses two cases, Case Alpha and Case Beta, to illustrate the research framework for articulating a perceptions-based framework and to put forward a set of propositions and research questions for further research (for illustrative case method use, see Buganza, Trabucchi, and Pellizzoni Citation2020). Both cases, Case Alpha and Case Beta are connected to the same supplier but feature different buyers. The buyer in Case Alpha is simply referred to as Buyer Alpha and similarly the buyer in Case Beta is called Buyer Beta. Cases were produced via a longitudinal research project (Yin Citation2009; Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki, and Welch Citation2010) spanning the period of 2008-2021, providing opportunities to understand specific changes in behavioural and structural power as well as dynamics that are catalysed by countervailing and contextual events.

The research approach adopts critical realist stances for understanding power as being visible in buyer-supplier interactions (i.e. actions related to perceptions and reactions) and embedded into social structures and latent mechanisms (Bhaskar Citation1979; Easton Citation2000). Power is detected in the focal buyer-supplier relationship through events considered as outcomes of actors’ behaviours and related mechanisms and social structures. Thus, our approach is based on a retroductive mode of inference; we do not ask informants directly about power but aim at extracting dynamic interchange between actions and underlying structures, revealing the hidden generative mechanisms and behaviours that manifest power (Sayer Citation2004; Zadykowicz, Chmielewski, and Siemieniako Citation2020). Our approach to the study of power dynamics is guided by previous research on supply chain dynamics with stances in critical realism and respective methods (see Adamides, Papachristos, and Pomonis Citation2012).

3.2. Data gathering and analysis

Thematic interviews served as the main data gathering technique, enabling a gentle approach to the sensitive issue of power in buyer-supplier relationships (Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki, and Welch Citation2010). Interviewees were not asked directly about power asymmetry and dynamics. Rather, these elements were operationalised into smaller entities and made comprehensively accessible for informants. The interviews aimed to capture specific, time-bound information of all types of factors that influence relationship power dynamics. The final data includes 20 interviews (see in Appendix 1).

Table 1. Data gathering for the two longitudinal case studies.

To increase the validity of the research findings, each researcher analysed the interview transcripts separately and provided inductive and deductive codes and theoretical notes (Krippendorff Citation2004; Ritchie and Lewis Citation2003). To complement the deductive coding, we were open to identifying power asymmetry change factors in the informants’ language; therefore, some codes were also inductive. A reliability check was carried out via internal replication according to which two coders exchanged a sample of two interviews and provided alternative and independent coding. No substantial differences between the initial coding and the alternative coding existed, thereby indicating the reliability of the analysis (Krippendorff Citation2004).

For data triangulation, the interview data were supplemented by several data gathering methods and sources at various points in time (see Stavros and Westberg Citation2009). The researchers systematically took empirical and theoretical notes over the entire period. Direct observations were conducted during buyer-supplier meetings, during suppliers’ internal managerial meetings and at trade fair locations. To further supplement these data, we analysed various documents (Yin Citation2009), such as contractual agreements, buyer-supplier meeting memos, suppliers’ internal management meeting memos, email communications, supplier performance reports (e.g. sales reports, financial reports and CRM reports) and other documents (e.g. suppliers’ financial plans, strategic and marketing plans and annual plans of common buyers’ and suppliers’ sales and marketing actions). This approach allowed us to obtain a longitudinal picture of power dynamics and validate the information that was gathered from one source (i.e. interviews with selling companies’ employees) against information from other sources (e.g. interviews with buying companies’ employees, offline and online secondary sources and direct observation).

3.3. Limitations

Evidently, power is a multifaceted and challenging concept for a study to capture. However, our study benefited from various data sources and the longitudinal, dyadic case study. Our approach was thus largely based on researchers’ interpretations of power, not actors’ direct experiences of power. Thus, the levels of structural and behavioural power and power dynamics were researchers’ judgements based on the data. This approach is certainly open to critics, as an external party cannot have the same direct experience of structural and behavioural power nor of power dynamics as relationship actors. Thus, the presented levels of these elements are not exact measures; rather, they manifest if these elements remain stable, diminish or grow regarding the relationship and its previous power statuses.

To supplement the analysis, interpretations were presented to the key informants through open discussions. Based on these discussions, we ensured that our case studies’ general picture reflected reality. However, the role of some events or individual actions may have different emphasis regarding the participants and their subjective perceptions. Accordingly, further research should be open to this inherent challenge within the topic of power in buyer-supplier relationships; it should aim towards variety in dataset usage and researcher triangulation to verify interpretations. The transition of specific results in this study to other empirical contexts must be carefully made. However, this study aims at theoretical generalisations. The main target of the findings is to build a theoretical perspective rather than to pose assertions regarding causal-construct relations.

4. Research results

4.1. Research context – the supply of instruments and solutions for orthopaedic surgeries

Both cases are connected to an Eastern European supplier company manufacturing medical equipment. The supplier applies novel techniques and materials (e.g. biodegradability, 3D titanium printing and ultrasound usage) to attain superior quality and novel functionalities to serve various distributors and medical specialists. The supplier offers the resellers a wide array of support, including organising trainings and workshops, assisting surgeons’ operations and designing customised products. In the medical equipment industry, it is a typical practice to cooperate with the sole distributor in one country, which is also the policy of the analysed supplier. This case focuses on two buyer companies coded as Buyer Alpha and Buyer Beta, representing the supplier’s distributors in different countries.

Two types of hospitals can be distinguished as the buying organisations of the analysed medical equipment: public or private. Public hospitals generally use public tenders and a one-year contract between the distributor and hospital. Private hospitals in the analysed countries did not utilise tenders. Private hospitals order small volumes of products from distributors quite often and when needed. Eventually, there is a minute amount of inventory. Therefore, because of medical treatment requirements, it is important that distributors have a stock of these products to provide them on time. In Case Alpha and Case Beta, distributors sold the supplier’s medical equipment both to private and public hospitals.

4.2. Case alpha

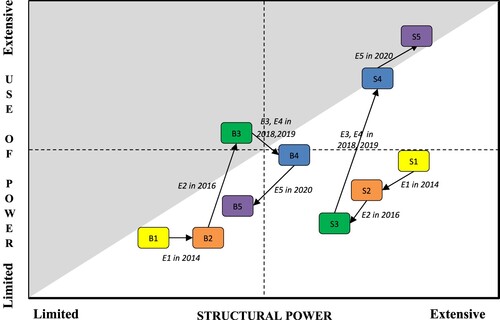

The relationship in Case Alpha features five events of power dynamics (E1, E2, E3, E4 and E5) influencing the structural and behavioural power shifts in the positions of Buyer Alpha (beginning from power position B1 to B5) and the supplier (beginning from power position S1 to S5) within this relationship’s analysed eight-year timeline ().

The relationship between Buyer Alpha and the supplier began in early 2013, when a one-year contract was signed. Initially, the newness of the supplier’s solutions caused buyer shortages in technical knowledge of supplier products and operational techniques. The contract provided the supplier with a clear advantage in contractual conditions, including explicit potential for sanctions to be implemented against Buyer Alpha for a contract violation.

This explains the power positions of B1 seen in . The position of the supplier (S1) with regards to extensive structural power is explained by Buyer Alpha’s and the supplier’s perceptions of substantial asymmetry regarding expertise connected to the supplier’s solutions. The new contract signed in early 2015 provided more balanced terms for the actors, meaning the conditions of potential penalties and sanctions were shared somewhat equally between both partners. For example, the minimum sales amount condition that the buyer was obliged to achieve in the first contract was cancelled. It was intentional from the buyer side to increase the structural power through achieving a balanced consecutive contract; according to interviewees from Buyer Alpha’s side, this was to improve the bargaining position with the supplier and build a position for acquiring increased value; it was expected to be co-created within a focal relationship in the future (e.g. regarding collaborative initiatives of market development and R&D adjustments to the local market for the supplier’s product). This event (E1) is related to the new contract that caused structural power shifts of both partners to positions B2 and S2, remaining in limited power use level.

A countervailing event (E2) was identified at the beginning of 2016. Buyer Alpha used power related to their knowledge of country-related features to make the supplier invest in their relationship and develop new products according to the local medical specialists’ requirements. Buyer Alpha refused to share information concerning medical specialists, which was conditioned on fulfilment by the supplier of their aforementioned requirements. The limitation of the supplier’s access to medical specialists was problematic for the supplier, as making it difficult to support knowledge transfer to the network of medical specialists associated with Buyer Alpha could discourage medical specialists from using the supplier’s products. The supplier conformed to Buyer Alpha’s requirements, improving trading conditions. It engaged in various promotional and educational activities with Buyer Alpha and associated medical specialists. This is why the buyer’s power position shifted to B3 via an intensive use of power; the structural power also increased due to gathering network information and not sharing with the supplier and acquiring from the supplier expertise of products’ technical knowledge and operational techniques. Further development of Buyer Alpha’s know-how was crucial in terms of providing medical specialists with appropriate level support services (e.g. ‘ … we engage a lot in increasing their expertise competencies and in building their brand reliability’ supplier, board member).

The supplier’s structural power and intensity of power use decreased (position S3) – influenced by E2 – due to the supplier’s desire to improve service quality by supporting medical specialists for market development. They needed Buyer Alpha’s support in gaining access to surgeons. Consequently, the supplier was limited in that period (2016) to using power in terms of pressuring the distributor to invest in new products being offered by the supplier; the supplier’s structural power was also limited as surgeon support services were not provided.

Since we started working with surgeons in 2016, which was even more intense in the next few years, we expected from the distributor (Buyer Alpha) adequate actions (e.g. entering the new hospitals, promoting new types of our products, etc.). (supplier, CEO)

We were trying systematically to convince the distributor (Buyer Alpha) to take our other types of products. Well, they took them literally a few items in a manner of ‘get off my back. What do you want? After all, I took it’. This showed us that they don’t want to engage. (supplier, CEO)

In 2020, the supplier threatened to end the relationship following Buyer Alpha’s potential rejection of requirements to invest in introducing new types of products into the existing market (position S5). The supplier used the opportunity to move two key employees who cooperated with the supplier from Buyer Alpha to a competitive distributor (Buyer X) in the local market. Structural power was changed for both, as it caused an increase in the supplier’s structural power (S5) due to an alternative distributor. This situation impacted the decrease of Buyer Alpha’s structural power (B5), causing shortages in product and market knowledge. Buyer Alpha continued to reject the supplier’s requirements. The supplier ended the relationship with Buyer Alpha at the end of 2020 and began cooperating with Buyer X.

4.3. Case beta

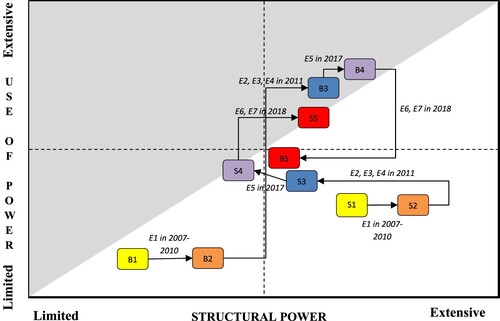

The relationships in Case Beta began in 2007. We identified seven power-related events (beginning from E1 to E7) and five power positions of the supplier and Buyer Beta ().

Upon entering the supplier contract, Buyer Beta possessed limited experience in distributing such medical equipment. This starting point explains the structural power differences regarding expert sources of power. The supplier’s previous distribution activities in Buyer Beta’s local market explain its high structural power position (S1). From the onset, the next four years of the relationship’s development could be characterised as systematic development of Buyer Beta’s expertise of wide ranges of supplier products and operational techniques. Over this period, the supplier significantly increased knowledge concerning medical specialists’ requirements. The structural power of both actors increased to B2 and S2 positions during 2007–2010 as a result of relationship developments, not as planned directed action. E1 in depicts the aforementioned contextual events of relationship development.

Following the first four years of cooperation, supplier sales levels to Buyer Beta rapidly increased by about 200% in 2011; Buyer Beta eventually accounted for 45% of the supplier’s global exports (among 50 foreign distributors). Such rapid Buyer Beta market expansion was caused by macro-environmental factors, including changes in government regulations of this distributor’s country-territory and influencing the improvement of Buyer Beta’s position among medical specialists. This contextual event (E2) significantly improved Buyer Beta’s structural power (B3). The supplier’s structural power decreased (S3) as access to and influence on medical specialists became increasingly limited.

Cooperation with Buyer Beta was very beneficial for the supplier. Buyer Beta emphasised timely delivery of a growing volume of orders from the supplier due to hospitals’ requirements. Buyer Beta made threats to switch to another supplier if orders were not delivered on time, recognised as a countervailing event (E3) which significantly influenced the dynamics of Buyer Beta’s power use (position B3). Buyer Beta’s claims were problematic for the supplier due to its limited production capacity. A supplier interviewee described this problematic situation: ‘This company (Buyer Beta) put pressure on us to be on time with order delivery, which we could not ignore because it could provoke the threat of losing this distributor’ (supplier, sales director). The supplier attempted in vain to utilise power by refusing to fulfil Buyer Beta’s requirements, as it could negatively cause delays in order completion for other distributors (position S3).

To enhance supplier motivation in late 2011, Buyer Beta periodically stopped recommending the supplier’s products among potential and new medical specialists in domestic markets, interpreted as a countervailing event (E4). The impact on the supplier was increased priority of timely order delivery and ensuring new, customised product development. This worked due to the supplier’s financial benefits, and it became the priority, ‘(…) to give them what they wanted first’ (supplier, sales director), in terms of order delivery and priority of ‘service support because their intensive market penetration meant there were more customer problems to be solved’ (supplier, sales director).

These examples show the dynamics of power use in terms of its frequency and intensity, explaining Buyer Beta’s power position shift from B2 to B3. This shift initialised Buyer Beta’s power advantages, as opposed to earlier in the relationship. The supplier’s problematic situation was related to a significantly lower structural power level (position S3), exposing the manufacturer to Buyer Beta’s further use of power.

A significant contextual event (E5) occurred in 2017, which was related to the appearance of intensive competition for the supplier offering lower prices and product quality. Having an alternative, Buyer Beta’s structural power increased, pressuring the supplier (position B4) to lower prices. Despite the supplier’s attempt to pressure Buyer Beta and disagree with lowering prices (position S4), it finally agreed with Buyer Beta’s requirements.

The supplier began involving Buyer Beta in more cooperative initiatives (e.g. collaborative, new technology product development and common workshops for medical specialists in Buyer Beta’s country location); such contextual events are described in E6. The supplier regained its irreplaceable status, increasing its structural power (position S5). Simultaneously, Buyer Beta’s structural power decreased (position B6) as new resources were required and some of the medical specialist network was extended to the supplier. Concurrently, we observed a countervailing event (E7) of the supplier’s power use (S5) by convincing medical specialists to use new models of products; surgeons pressured Buyer Beta to order new product models from the supplier to replace the old ones. Furthermore, the supplier was more effective in managing Buyer Beta’s order requests concerning volume and delivery time. Buyer Beta’s further trials of using coercive power were no longer as effective; the supplier treated this as bluffing instead of real threats, and Buyer Beta’s barrier of exit increased due to the supplier’s countervailing actions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key findings

The study aimed at holistically considering structural and behavioural power and power dynamics. It involved two business dyads where substantial shifts in power asymmetry occurred during relationship development. These cases played an illustrative role in providing a longitudinal account of structural and behavioural power dynamics launched by countervailing and contextual events. The next section integrates the findings into a perceptions-based framework, creating a set of propositions and research questions that comprise a research agenda.

Both cases were rich in demonstrating countervailing power events through which the actors aimed at increasing their structural power, thus increasing the potential for behavioural power. Similarly, the cases exemplified contextual events. Regarding these concepts, the cases showcase the crucial role of actors’ perceptions (Rutherford and Holmes Citation2008) in realising countervailing and contextual events and their effects on structural power and potential for behavioural power (Oukes, von Raesfeld, and Groen Citation2019).

5.2. Implications to theory

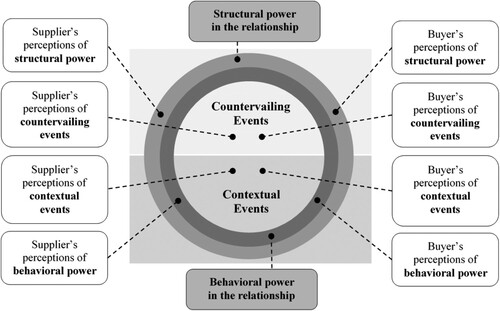

displays countervailing and contextual events as panels that are connected to structural and behavioural power via circles. Furthermore, these elements are meaningful and come into the relationship via supplier and buyer perceptions and reactions. Thus, the framework in focuses on supplier-buyer perceptions of these elements.

Figure 4. Perceptions-based framework of power in buyer-supplier relationship: areas for future research.

The left side of this framework presents the supplier’s perceptions; the right side represents the buyer’s perceptions. Perceived structural power refers to actors’ perceptions of its own structural power and that of the other party. Actor-perceived countervailing events refer to supplier perceptions of buyer actions that aim towards increasing the buyer’s structural power as well as the supplier’s perceptions of its actions to increase its structural power. Supplier-perceived contextual events comprise events that the supplier perceives as affecting its own or the buyer’s structural power. Supplier-perceived behavioural power refers to the supplier’s perception of its own and the buyer’s use of power in the relationship.

The cases exemplify perceptions as a means through which the objective state of power institutionalises the relationship’s power. First, the perceptual approach depicted in this framework underlines that power is a mixture of an objective entity (i.e. actual elements of using and possessing power and both actors’ subjective perceptions; Rutherford and Holmes Citation2008). To concretise the framework’s usability regarding structural power in a relationship, we propose the following (P1-P4):

P1: Structural power in a relationship is a function of a supplier’s/buyer’s actual structural power and the actors’ perceptions thereof (i.e. perceived structural power).

P2: The structural power of an actor is derived from the other actor’s dependency on that actor as a function of value co-creation opportunities within and outside the focal relationship for that actor.

P3: Actors’ perceptions may vary in accuracy; actors may ignore, understate or overstate their own or the other actor’s structural power.

P4: Structural power is not a zero-sum game; the level of each actor’s structural power may alter independently between being limited and extensive.

RQ1: How does structural power institutionalise in relationships?

RQ2: How does actual and perceived structural power interplay in the relationship?

RQ3: What elements drive an actor’s capacity to visualise actors’ dependency as a function of value co-creation opportunities within and outside the focal relationship?

P5: Perceived structural power in the relationship sets the range for behavioural power (i.e. power use in the relationship).

P6: The gap between perceived and actual structural power may allow for overuse of power.

P7: The overuse of power may be based on tolerance by the power target.

P8: A tolerant actor possesses motivation not to counter-use power.

P9: Increased structural power in the relationship diminishes the use of power and reinforces relational governance modes to nurture the relationship.

RQ4: How do short-/long-term motivations steer relationship power use and tolerance?

RQ5: How does power use affect perceived and actual structural power?

RQ6: For reverse use of power, how can the structural power of an actor guide the other party to adapt, even without the power source’s explicit power use?

P10: The effect of countervailing and contextual events on power dynamics may alternate regarding relationship development and business context dynamics.

P11: Actors’ perceptions of countervailing and contextual events may mirror or conflict with each other.

P12: Contextual events in the business context of an actor are partly hidden from the other actor.

RQ7: How do countervailing and contextual events in a relationship institutionalise in its structural power?

RQ8: How do firm-, relationship-, and business-context factors affect perceptions regarding countervailing and contextual events?

5.3. Implications to practice

From the perspective of power for managers, this study provides a holistic picture for obtaining a strategic perspective on relationship management. The presented propositions can be used to define areas to sketch trajectories of power-related opportunities and objectives for supporting relationship purposes. Structural and behavioural power ideas can be used for gaining and unifying information from various sources to understanding opportunities and threats associated with a power source’s power use and being the power object that is under the power use in buyer-supplier relationships. Analysis should focus on implications and necessary modifications regarding company business models and resource bases, including what kind of collaboration and competition opportunities the trajectory offers and what strategic decisions are needed regarding changing the company’s resource base and business model. Managers should build a resource roadmap (i.e. resources the company needs to build, acquire and integrate to sense and seise value co-creation opportunities within and outside the focal relationship to occupy a relatively advantageous power position in both focal relationships and others). This framework can be used as a means for mutual development to build a shared mental model and language regarding a relationship’s power dynamics and power mechanisms.

6. Conclusions

This study offers three major contributions on power and power dynamics in business relationship research (Lacoste and Johnsen Citation2015; Talay, Oxborrow, and Brindley Citation2020; Handley and Benton Citation2012; Munksgaard, Johnsen, and Patterson Citation2015). First, it provides a balanced consideration of structural and behavioural power, continuing the work of recent researchers (Oukes, von Raesfeld, and Groen Citation2019). This study reveals how structural and behavioural power interplay and how countervailing and contextual events catalyse power dynamics. Thus, this study articulates a set of research directions that are inclusive of the buyer and supplier and their mutual relationship as an open system. Second, this focal study facilitates the recognition of structural power as a multifaceted element featuring both situational and enduring aspects; this relates to value creation opportunities for parties within and outside the mutual relationship, determining the actor’s ultimate co-dependence. Third, the study builds a perceptions-based framework and provides a set of propositions and research questions that comprise a further research agenda. This contributes to extant power literature that limitedly represents holistic perspectives to capture the dynamics between behavioural and structural power as well as dynamics within and outside the focal relationships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hannu Makkonen

Hannu Makkonen is Professor of Marketing at School of Marketing and Communication at the University of Vaasa. His research interests lie in the areas of innovation management, innovation ecosystems, and value creation logics in industrial networks and relationships. His previous work has been published in e.g. Industrial Marketing Management, Journal of Business Research, Marketing Theory, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Management Decision, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management Journal of Business Market Management, and Journal of Financial Services Marketing.

Dariusz Siemieniako

Dariusz Siemieniako is an Associate Professor at the Bialystok University of Technology and at the Kozminski University, both in Poland. He has been associated as an Adjunct in the Department of Marketing, Social Marketing @ Griffith, Griffith University, Australia, for the years 2013 - 2019. His research focuses on B2B relationship marketing including power issues and collaborative innovation development. Dariusz is also engaged in research on inter-organisational relationships versus social impact. He is interested in the research of strategy of organisations including dynamic capabilities issue. He published in quality journals including: Industrial Marketing Management, Journal of Marketing Management, Journal of Customer Behaviour, Journal of Social Marketing and Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal. He was awarded scholarships of University of Cambridge and Griffith University. Dariusz has also a many years of experiences in business practice in large manufacturing companies and retail real estate developers in international environment, as a CEO, Board Member, Director of Business Development and consultant.

Maciej Mitręga

Maciej Mitrega is Head of Organisational Relationship Management Department and Chair Professor of Management Science Board at the University of Economics in Katowice, and Full Visiting Professor at the Technical University of Ostrava (VSB). Devoted to high-quality research with research results published in Long Range Planning, International Journal of Operations & Production Management (Emerald), Industrial Marketing Management and Journal of Services Marketing (Emerald). Guest editor in quality academic journals, including Industrial Marketing Management, Journal of Business Research, International Marketing Review. Prior visiting professorship appointments in several universities in Europe and prior Marie Curie Research Fellow. The member of the editorial boards in Industrial Marketing and Management, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing (Emerald) and Oeconomia Copernicana. An interdisciplinary researcher with most of research conducted in the strategy area but with strong links to consumer research, marketing, operations management, and social psychology.

References

- Adamides, E. D., G. Papachristos, and N. Pomonis. 2012. “Critical Realism in Supply Chain Research.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 42 (10): 906–930.

- Bhaskar, R. 1979. The Possibility of Naturalism. Brighton: Harvester Press.

- Buganza, T., D. Trabucchi, and E. Pellizzoni. 2020. “Limitless Personalisation: the Role of Big Data in Unveiling Service Opportunities.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 32 (1): 58–70.

- Cowan, K., A. K. Paswan, and E. Van Steenburg. 2015. “When Inter-Firm Relationship Benefits Mitigate Power Asymmetry.” Industrial Marketing Management 48: 140–148.

- Doorn, N., R. Raven, and L. Royakkers. 2011. “Distribution of Responsibility in Socio-Technical Networks: the Promest Case.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 23 (4): 453–471.

- Easton, G. 2000. “Case Research as a Method for Industrial Networks: a Realist Apologia.” In Realist Perspectives on Management and Organisations, edited by S. Ackroyd, and S. Fleedwood, 205–214. London: Routledge.

- French, R. P., and B. Raven. 1959. “The Bases of Social Power.” In Studies in Social Power, edited by D. Cartwright, 155–164. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Habib, F., M. Bastl, and C. Pilbeam. 2015. “Strategic Responses to Power Dominance in Buyer-Supplier Relationships: a Weaker Actor’s Perspective.” International Journal of Physical Distribution and. Logistics Management 45 (1/2): 182–203.

- Handley, S. M., and W. C. Benton Jr. 2012. “Mediated Power and Outsourcing Relationships.” Journal of Operations Management 30: 253–267.

- Håkansson, H., D. Ford, L.-G. Gadde, I. Snehota, and A. Waluszewski. 2009. Business in Networks. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hingley, M., R. Angell, and A. Campelo. 2015. “Introduction to the Special Issue on Power in Business, Customer, and Market Relationships.” Industrial Marketing Management 48: 101–102.

- Krippendorff, K. 2004. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

- Lacoste, S., and E. Johnsen. 2015. “Supplier–Customer Relationships: A Case Study of Power Dynamics.” Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 21: 229–240.

- Makkonen, H., L. Aarikka-Stenroos, and R. Olkkonen. 2012. “Narrative Approach in Business Network Process Research. Implications for Theory and Methodology.” Industrial Marketing Management 41 (2): 287–299.

- Makkonen, H., and M. Vuori. 2014. “The Role of Information Technology in Strategic Buyer-Supplier Relationships.” Industrial Marketing Management 43 (6): 1053–1062.

- Meehan, J., and G. Wright. 2012. “The Origins of Power in Buyer–Seller Relationships.” Industrial Marketing Management 41 (4): 669–679.

- Munksgaard, K. B., R. E. Johnsen, and C. M. Patterson. 2015. “Knowing me, Knowing you: Self-and Collective Interests in Goal Development in Asymmetric Relationships.” Industrial Marketing Management 48: 160–173.

- New, S. J. 2004. “Supply Chains: Construction and Legitimation.” In Understanding Supply Chains: Concepts, Critiques, and Futures, edited by S. New, and R. Westbrook, 69–108. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nyaga, G. N., D. F. Lynch, D. Marshall, and E. Ambrose. 2013. “Power Asymmetry, Adaptation and Collaboration in Dyadic Relationships Involving a Powerful Partner.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Chain Management 49 (3): 42–65.

- Oukes, T., A. von Raesfeld, and A. Groen. 2019. “Power in a Startup's Relationships with its Established Partners: Interactions Between Structural and Behavioural Power.” Industrial Marketing Management 80: 68–83.

- Pagani, M., and C. Pardo. 2017. “The Impact of Digital Technology on Relationships in a Business Network.” Industrial Marketing Management 67: 185–192.

- Pérez, L., and J. Cambra-Fierro. 2015. “Learning to Work in Asymmetric Relationships: Insights from the Computer Software Industry.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 20 (1): 1–10.

- Piekkari, R., E. Plakoyiannaki, and C. Welch. 2010. “‘Good’ Case Research in Industrial Marketing: Insights from Research Practice.” Industrial Marketing Management 39 (1): 109–117.

- Pinch, T. J., and W. E. Bijker. 1984. “The Social Construction of Facts and Artefacts: or how the Sociology of Science and the Sociology of Technology Might Benefit Each Other.” Social Studies of Science 14 (3): 399–441.

- Plouffe, C. R., W. Bolander, J. A. Cote, and B. Hochstein. 2016. “Does the Customer Matter Most? Exploring Strategic Frontline Employees’ Influence of Customers, the Internal Business Team, and External Business Partners.” Journal of Marketing 80 (1): 106–123.

- Provan, K. G. 1980. “Recognizing, Measuring, and Interpreting the Potential/Enacted Power Distinction in Organizational Research.” Academy of Management Review 5 (4): 549–559.

- Ratinen, M., and P. Lund. 2016. “Alternative View on Niche Development: Situated Learning on Policy Communities, Power and Agency.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 28 (1): 114–130.

- Ritchie, J., and J. Lewis. 2003. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London: Sage Publications.

- Rutherford, T., and J. Holmes. 2008. “The Flea on the Tail of the dog: Power in Global Production Networks and the Restructuring of Canadian Automotive Clusters.” Journal of Economic Geography 8 (4): 519–544.

- Sayer, A. 2004. “Foreword: why Critical Realism?” In Critical Realist Applications in Organisation and Management Studies, edited by S. Fleetwood, and S. Ackroyd, 6–20. London: Routledge.

- Siemieniako, D., and M. Mitręga. 2018. “Improving Power Position with Regard to non-Mediated Power Sources–the Supplier's Perspective.” Industrial Marketing Management 70: 90–100.

- Stavros, C., and K. Westberg. 2009. “Using Triangulation and Multiple Case Studies to Advance Relationship Marketing Theory.” Qualitative Market Research 12 (3): 307–320.

- Talay, C., L. Oxborrow, and C. Brindley. 2020. “How Small Suppliers Deal with the Buyer Power in Asymmetric Relationships Within the Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain.” Journal of Business Research 117: 604–614.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Zadykowicz, A., K. J. Chmielewski, and D. Siemieniako. 2020. Proactive customer orientation and joint learning capabilities in collaborative machine to machine innovation technology development: the case study of automotive equipment manufacturer. Oeconomia Copernicana, 11(3): 531–547.