?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study examines the impact of inbound and coupled open innovation (OI) strategies in single and complex innovators, whereby the former concerns firms that engage in either product or process innovation, while the latter encompasses firms that simultaneously engage in product and process innovations. Moreover, the relative performance effects of OI strategies in complex and single innovators are largely unexplored. Data are derived from the German innovation survey. It focuses on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in manufacturing sectors. Logit regression is used to measure the impact of breadth and depth of inbound OI and the breadth of coupled OI strategy on innovation performance of complex and single innovators. Empirical findings suggest that among single innovators, search depth is more effective in stimulating product than process innovations. Besides product innovators, complex innovators also benefit from search depth relative to single process innovators. With respect to other dimension of OI, search breadth has no differentiating effect among single and complex innovators, while cooperation breadth is more effective in complex innovators relative to single innovators, whether product or process.

1. Introduction

Firms develop innovations towards achieving competitive advantage as they are increasingly aware of the need to interact with their knowledge landscape to integrate their internal R&D efforts and of the importance of managing their outbound flows of knowledge and technology (Chesbrough Citation2006). The concept of open innovation (OI) introduced by Chesbrough fuelled the stream of research focusing on how firms’ interactions with the external environment affect their innovation activities. OI defined as ‘the use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation, and to expand the markets for external use of innovation, respectively’ (Chesbrough, Vanhaverbeke, and West Citation2006, 1). OI can be viewed as a distributed innovation process based on purposively managed knowledge flows across organisational boundaries, using financial and non-financial indicators in line with the organisation's business model (Chesbrough and Bogers Citation2014).

The OI literature has recognised that the adoption and effectiveness of OIs varies between small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and large firms. SMEs, due to their limited human and financial resources (and thus weaker absorptive capacity), might benefit more from accessing external knowledge than large firms (Parida, Westerberg, and Frishammar Citation2012). Moreover, there is a reverse causality between firms’ absorptive capacity and the use of external knowledge: external knowledge can enhance absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal Citation1990), but the extent of use and the effectiveness of external knowledge critically depend on the strength of absorptive capacity (Chesbrough Citation2006). Firms can adopt OI through one or more strategies: inbound OI, which focuses on firms’ use of external knowledge; outbound OI, which encompasses the external use of firms’ internal knowledge; and coupled OI, which refers to formal cooperative networking, such as strategic alliances and joint ventures (Gassmann and Enkel Citation2004). With respect to types of OI strategies, due to a limited absorptive capacity in SMEs, these firms are more likely to engage in informal linkages with economic actors in their innovation ecosystem than large firms (Parida, Westerberg, and Frishammar Citation2012; Van de Vrande, Vanhaverbeke, and Gassmann Citation2009). However, this does not mean that SMEs do not engage in formal cooperative partnerships (coupled OI) and that this type of OI strategy is less effective in promoting SME innovation performance.

Highlighting the gap in OI literature explicating open innovation, Chesbrough and Bogers (Citation2014) call for more research on the context of openness and its importance for SMEs, pointing out the necessity to go further beyond the typical scope of R&D and product innovation to fully address process innovation. More recently, Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll (Citation2021) examine how inbound OI in SMEs affect pure product innovation relative to pure process innovation. Their findings reveal that search strategies that are effective in stimulating pure product innovation are different from those effective in case of pure process innovations. The first contribution of this study is to extend the analysis by Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll (Citation2021) by identifying and analysing complex and pure innovators. With respect to types of innovation, most studies focus on product innovation, while other types of innovation are rather neglected (Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll Citation2021). This study not only examines product and process innovations separately, but also takes into account that some firms might solely focus on one type of innovation, while others might adopt both. This point of departure means that we identify firms that are complex innovators, as firms that simultaneously engage in product and process innovations and single (pure) innovators,Footnote1 as firms that engage either in product or process innovations (Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll Citation2021; Le Bas and Poussing Citation2014; Radicic Citation2020). In particular, it is interesting to identify whether open innovation strategies differ between complex and pure innovators. These insights might help managers in pure-innovators firms who wish to become complex innovators to focus on a particular aspect of open innovation that would speed up the process of transformation from a pure to a complex innovating firm.

The second contribution of the study is associated with the types of OI strategies that are examined. Most empirical studies examine the effectiveness of inbound OI on firms’ innovation performance, while coupled OI and in particular outbound OI are less investigated (Greco, Grimaldi, and Cricelli Citation2016). Our study examines the effectiveness of inbound OI, measured by search breadth and search depth, as well as coupled OI, measured as the breadth of cooperation for innovation with various partners.Footnote2 Finally, the third contribution is associated with the estimation of the three groups of relative effects of OI strategies, i.e. pure process versus pure product innovators, complex versus pure product innovators and complex versus process innovators. Therefore, our empirical findings relevel similarities and differences between complex and pure SME innovators with respect to the effectiveness of OI strategies.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The next section presents a theoretical framework on OI in SMEs and formulates hypotheses. Then, the methodology section describes the dataset and model specification. In the results section, we present empirical findings, which are followed by the discussion of results. Finally, we elaborate on the contributions of the study, practical and managerial implications and identify limitations and suggestions for future studies.

2. Theoretical background

Open innovation deals with firms’ innovation capabilities derived from the interaction with other firms (Chesbrough Citation2003). Although no single theory fully explains how and why firms open up their innovation processes, several economic and managerial conceptual frameworks yield insights into OI practices. These conceptual frameworks include the relational view of the firm, the resource-based theory and the concept of absorptive capacity. The relational view of the firm (Dyer and Singh Citation1998) suggests that firms can gain competitive advantage by combining complementary resources in a unique manner, which is consistent with the OI framework. The resource-based view of the firm (Barney Citation1996) constitutes a framework for understanding how firms create and configure internal and external activities to build their capabilities to innovate. External knowledge builds on internal capabilities, directly created by a firm's expertise, routines, market knowledge and technology and organisation systems (Volberda, Foss, and Lyles Citation2010). Interrelationships and synergies created from the joint integration of different sources of knowledge build up innovation capabilities. Moreover, OI is closely related to the concept of absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal Citation1990). Absorptive capacity, which is usually a result of firms’ internal R&D activities, is then complementary to OI practices (Chesbrough and Crowther Citation2006).

Firms can adopt OI through one or more strategies: inbound OI, which focuses on firms’ use of external knowledge sources; outbound OI, which encompasses the external use of firms’ internal knowledge; and coupled OI, which refers to R&D collaborations and technology alliances (West and Bogers Citation2014). In this study, we focus on two open innovation strategies (inbound and coupled), as our dataset does not provide information on outbound strategies. Inbound open innovation (often termed search strategy) refers to a one-way flow of knowledge from a firm's environment to the focal firm. In other words, inbound paths for open innovation explain how external knowledge sources contribute to value creation and value capture (West and Bogers Citation2014). This type of open innovation is often operationalised using the concepts of search breadth and search depth, first introduced by Laursen and Salter (Citation2006). These concepts will be explained in the next section. In contrast to inbound paths for open innovation, coupled strategy is associated with a two-way flow of knowledge between the focal firm and its collaborative partners (West and Bogers Citation2014). To operationalise this type of open innovation, we use the concept of cooperation breadth (which counts the number of cooperative partners, see Cricelli, Greco, and Grimaldi Citation2016; Greco, Grimaldi, and Cricelli Citation2016; Radicic et al. Citation2019).

The literature on OI has long recognised that SMEs should be studied separately from large firms, because the characteristics and effectiveness of OI might be different in SMEs relative to large firms (D’Angelo and Baroncelli Citation2020). The main disadvantages of SMEs regarding innovation activities are associated with limited financial and human resources. To compensate for weak or limited absorptive capacity, SMEs explore external opportunities and sources to compensate for the limitations in their own innovation capacity (see Chesbrough, Vanhaverbeke, and West Citation2006; Van de Vrande et al. Citation2009, Citation2010).

2.1. Hypothesis development

In this study, we divide SMEs into three categories: (i) complex innovators, which are firms that introduce both product and process innovations, (ii) pure product innovators and (ii) pure process innovators. Complex innovators might innovate differently than pure (simple) innovators (Le Bas and Poussing Citation2014; Radicic Citation2020). The distinction between technological product and process innovation is well described in the literature, although an understanding of an impact of external knowledge sources, in the case of SMEs, are under-researched (Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll Citation2021). Product innovation is strongly associated with R&D activity as a long-term oriented purpose; high fixed costs involved and the necessary large innovation capacity (a minimum threshold) for supporting a R&D based investment require the latter to be a long-term oriented and rather persistent process. On the other hand, process innovation is less formalised, requires less scientific infrastructure and is more short-term oriented than product innovation.

The literature on technological (product and process) innovation mainly focuses on product innovation, although there are arguments to suggest that product and process innovations are complementary (Reichstein and Salter Citation2006; Ayllón and Radicic Citation2019). The gains of complex innovators are twofold. With new products, they open new markets (and gain competitive advantages), and with cost-reducing process innovations they increase the level of demand for their products. The scale of the commercial success of complex innovators enables them to increase profitability. In turn, thanks to higher profits, they can increase the resources devoted to R&D activity and innovate continuously.

In contrast to more innovative firms that engage in both types of technological innovations simultaneously, there are two categories of firms that exclusively develop a single type of innovation. The first group are pure process innovators, which are process-oriented SMEs mostly operating in low-tech industries. Innovation processes in these firms are characterised by a poor absorptive capacity, mainly relying on non-R&D innovation inputs (such as investments in training, know how, design etc.) (Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll Citation2021). Opposite are pure product innovators, which are more innovative firms relative to pure process innovators, as they have a higher absorptive capacity, and a high share of in-house R&D investment (Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll Citation2021).

The aim of this study is to explore how inbound and coupled open innovation strategies affect complex and pure innovating SMEs. Coupled open innovation is operationalised through cooperation breadth which measures the number of cooperative partners (see Greco, Grimaldi, and Cricelli Citation2016; Laursen and Salter Citation2006). In the literature on open innovation, informal networking can be regarded as inbound open innovation or the use of external knowledge search. It is considered to represent a ‘soft’ form of open innovation, because firms use external sources of knowledge, such as suppliers, customers, universities, etc. without entering into legally binding agreements (Laursen and Salter Citation2014). In contrast, formal cooperative relationships for innovation can be seen as a ‘hard’ form of open innovation. Different forms of openness enable firms to attain and absorb different types of knowledge. More specifically, external knowledge sources are likely to facilitate the exchange of standardised knowledge that is codified and easy to transfer (Tsinopoulos, Yan, and Sousa Citation2019). In contrast, formal cooperation relationships enable the exchange of less standardised knowledge that is often complex and tacit. Moreover, these cooperative ties entail a significant focus on managing and maintaining these relationships due to high transaction costs.

Due to their limited financial and human capital, SMEs are more likely to engage in informal networking than in formal networking (Parida, Westerberg, and Frishammar Citation2012; Van de Vrande et al. Citation2009). Consequently, those SMEs that have high and persistent absorptive capacity to engage in both product and process innovations will effectively use a wide network of cooperative partners, while pure product or process innovators would be more effective in exploring and exploiting external knowledge sources (inbound OI), rather than cooperative partnerships (coupled OI). In addition, cooperation for innovations, as a formal linkage, usually requires firms to use protection mechanisms, to minimise the risk of knowledge leakages and opportunistic behaviour of its partners (Radicic and Pugh Citation2017). As SMEs are less likely to use protection mechanisms, in particular formal such as patents and trademarks (Leiponen and Byma Citation2009), they will be prone to engage to a lower degree in formal linkages with cooperative partners than in informal linkages, such as knowledge sourcing.

H1: Cooperation breath is more effective in complex innovators, relative to both pure product and pure process innovators.

As noted above, inbound open innovation is associated with external knowledge flows or external search. These search strategies involve the use of a wide range of external actors and sources (Chesbrough Citation2003; Laursen and Salter Citation2006). Many firms had shifted to the practice of accessing external knowledge from a diverse typology of sources and actors that convey different knowledge to support the innovation process. Innovation can be viewed as a process that involves search for information and interaction with both market-based actors (i.e. customers, suppliers, competitors) and research institutions (i.e. universities and government) (D’Angelo and Baroncelli Citation2020; Sun, Liu, and Ding Citation2020; Zhao Citation2021).

Search breadth positively affects product innovation as it requires R&D-based investment to build high absorptive capacity. When firms continuously enhance their absorptive capacity, that means they will use a wide network of knowledge sources (Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll Citation2021). Process-oriented innovators, on the other hand, are characterised by poor absorptive capacity, that is meanly based on non-R&D innovation investment, such as in training, know how, machinery and equipment (Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll Citation2021). Because of limited absorptive capacity, these firms will not benefit from a wide search breadth (Reichstein and Salter Citation2006), but rather focus on accessing and exploiting knowledge from suppliers. Thus when looking at the effectiveness of search breadth in pure product innovators relative to pure process innovators, we expect search breadth to show a negative effect (as pure process innovators are category 1 in Model 1, while pure product innovators are category 0). In other models, where complex innovators are compared to pure innovators, we expect knowledge breadth to have a positive effect on complex innovators relative to pure process innovators, while we do not expect any significant difference between complex innovators and pure product innovators.

H2a: Search breadth is less effective in stimulating pure process innovation, than pure product innovation.

H2b: Search breadth is more effective in stimulating complex innovation, but only compared to pure process innovation.

H2c: There is no difference in the effectiveness of search breadth in complex innovation relative to pure product innovation.

H3a: Search depth is less effective in stimulating pure process innovation, than pure product innovation.

H3b: Search depth is more effective in stimulating complex innovation relative to pure process innovation.

H3c: There is no difference in the effectiveness of search depth in complex innovation relative to pure product innovation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

The Mannheim Innovation Panel (MIP) dataset used in this study has been collected by the Centre of European Economic Research together with the Fraunhofer-Institute for System and Innovation Research and the Institute for Applied Social Sciences on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF). The MIP is an annual innovation survey based on a panel sample of German firms that constitutes the German contribution to the European Commission's Community Innovation Survey (CIS). Our study focuses on the wave conducted in 2013 and covering the period 2010–2012. We focus on manufacturing firms, as innovation processes in service sectors might be different from those in manufacturing sectors (Radicic Citation2020). In addition, our analysis is restricted to SMEs. We are unable to compare the results for SMEs and large firms, as the number of large firms is the effective sample is too small to provide credible results (for instance, 84 firms for Model 1 specified in ). The effective sample varies from 502 to 728 observations depending on the model (see ).

Table 2. Average marginal effects from logit models.

3.2. Model specification

3.2.1. Dependent variables

As mentioned above, the three dependent variables are binary indicators, thus we use logit estimators. The dependent variable in Model 1 is equal to 1 if a firm only introduced process innovation, and zero if a firm only introduced product innovation. In this model, we want to look at the relative effect of open innovation on simple innovators (that either introduced product or process innovation). In Model 2 the dependent variable is equal to 1 if a firm is a complex innovator that engaged in both product and process innovations, and equal to zero if a firm is a simple innovator engaged only in process innovation. Finally, in Model 3, the dependent variable is equal to 1 if a firm is a complex innovator, and zero if a firm is a simple innovator engaged only in product innovation.

3.2.2. Explanatory variables

Our models include three variables of interest that measure open innovation. The first is Coop. breadth, which is constructed to capture the number of partners that firms cooperate for innovation. This variable ranges from zero to seven, as there are seven cooperative partners: customers, suppliers, competitors, consultants, universities, government institutions and private research centres (Laursen and Salter Citation2006). A value of zero is assigned to a firm that did not cooperate with any of the cooperative partners, while a value of seven is assigned to a firm that cooperate with all seven cooperative partners. The second variable of interest is Search breadth, which is the number of external knowledge sources (Laursen and Salter Citation2006, Citation2014). As firms also reported the degree of importance for each source, we have taken into account two levels: high and medium (Criscuolo et al. Citation2018; Laursen and Salter Citation2014). Seven external knowledge sources were considered in the survey – suppliers, customers, competitors, universities, consultants, government institutions and research centres. For each source, respondents to questionnaire indicated whether the source has a high, medium, low, or no importance. Second, every source was coded as a binary variable on the basis of its importance where a value of zero reflects a source of no or low importance and a value of one indicates a source of medium or high importance. Finally, the seven resulting dummy variables representing seven search channels were summed up. The minimum value of the variable is zero and the maximum value is seven, if all seven dummy variables are equal to 1. The third variable of interest is Search depth which measures the intensity of the use of external knowledge sources (Laursen and Salter Citation2006; Hervas-Oliver et al. Citation2020).

3.2.3. Control variables

With respect to control variables which capture firm and market characteristics, we include the following variables. Firm size is the number of employees in 2010. Variable Labour productivity is measured as turnover divided by the number of employees in 2010 (Radicic Citation2020). Export intensity is measured as a percentage of firms’ total revenues that came from sales in foreign markets in 2010, while R&D intensity is measured as R&D expenditure divided by turnover (Laursen and Salter Citation2014; Love, Roper, and Bryson Citation2011). Because of a potentially limited role of R&D investment in SMEs, other, complementary innovation input activities should also be included in the model. Acquisition of technologically new equipment and machinery is particularly important for the introduction of process innovations (Abreu et al. Citation2010), thus our models include a dummy variable Machinery (Silva et al. Citation2014; Radicic Citation2020). Variable Training is equal to 1 if a firm invested in in-house and/or external training in the context of product or process innovation, and zero otherwise (Cainelli, De Marchi, and Grandinetti Citation2020). Another variable to capture the impact of input innovation activities is Market introduction (Silva et al. Citation2014). Design activities play a coordinating role, so we include a dummy variable Design, equal to 1 if a firm invested in in-house and/or external procured design activities in direct connection to product or process innovation, and zero otherwise (Love, Roper, and Bryson Citation2011). Finally, sector effects are captured by eleven dummies for each manufacturing sector in the sample (see for summary statistics).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

4. Empirical results

Given that we analyse a self-reported data, common method variance could bias the estimates. We conducted a regression-based marker technique, whereby a potential bias is assessed by including a marker variable in the original regression model. A marker variable is a variable that is theoretically unrelated to the variables of interest (Kock, Berbekova, and Assaf Citation2021). As a marker variable, we used a dummy variable West which is equal to 1 if a firm is located in West Germany, and zero if it is located in East Germany. The correlation coefficients between the variables of interest and the marker variable are −0.179, −0.119 and −0.056 respectively. In the models with the marker variable, there are no significant changes in the signs or magnitudes of the coefficients on the independent variablesFootnote3, which suggests that the comment method bias is unlikely to occur (Kock, Berbekova, and Assaf Citation2021).

To estimate the impact of variables of interest on the probability of simple and complex innovators, the following logit models were estimated.

(1)

(1) where subscript i indexes each firm in the sample 1 … n, where n is the number of firms; control variables include firm and market characteristics (as explained above in Section 3.2),

vector contains coefficients on control variables and

is the random error term.

To qualitatively interpret the results, we estimated average marginal effects shown in . First, we comment on the results for each open innovation strategy individually. Cooperation breadth has a positive impact in case of complex innovators relative to both process innovation (Model 2, p < 0.05) and product innovation (Model 3, p < 0.05). In Model 1, the impact is statistically insignificant at any conventional level, which suggests that cooperation breadth has no differentiated effect on pure process innovators relative to pure product innovators. Search breadth is uniformly statistically insignificant in all three models. These results suggest no differences between three SME categories regarding the effectiveness of the breadth of external knowledge sourcing. However, search depth exhibits differentiated effects across different types of innovators. In Model 1, the coefficient is negative and significant at the 5% level, implying that the depth of use of external sources is more effective in pure product innovators, than in pure process innovators. In Model 2, the estimated marginal effect on search depth shows that the intensity of use of external knowledge is more effective in promoting innovation activities in complex innovators than in pure process innovators. However, the marginal effect of search depth in Model 3 is not statistically significant at any conventional level, suggesting that the intensity of external search has no differentiated effect between complex innovators and pure product innovators.

We comment on two hypotheses H2a and H2b that are not supported by our empirical findings. In Section 2.1, we argue based on previous literature that process-oriented innovators have poor absorptive capacity and thus focus on non-R&D activities. This argument is confirmed in . However, it could be that using knowledge from external sources is not just beneficial for R&D activities, but also for non-R&D activities. More precisely, using multiple knowledge sources could enable SMEs to better develop know how, to inform firms on available physical capital, and provide information about market introduction of new produces and/or process and products’ design. Moreover, absorptive capacity, as a facilitator of open innovation, may need to be comprehensively defined to include R&D as well as non-R&D activities. According to Moilanen, Østbye, and Woll (Citation2014), previous employees’ experience through learning-by-doing and tacit knowledge often significantly contribute to absorptive capacity, but they are rarely considered as an element of absorptive capacity. Therefore, it might be that arguments previously noted in the literature that process-oriented innovators have poor absorptive capacity need to be revisited by taking into account not just R&D, but also non-R&D based firms’ activities.

We briefly comment on the marginal effects with respect to control variables, in particular R&D and non-R&D innovation activities. All innovation activities are more effective in facilitating innovation outcomes in complex innovators relative to process innovators (Model 2), while machinery and training are more effective in complex innovators relative to product innovators (Model 3).

5. Potential non-linear effects of openness

Using external knowledge either through formal cooperation or informal search might have a positive innovation effect up to a certain point, after which the returns become negative due to over-search (Laursen and Salter Citation2006; Radicic Citation2020). Following Koput (Citation1997), there are three potential problems that can result in over-search. First, ‘the absorptive capacity problem’ might arise, whereby firms might be overwhelmed with too many innovative ideas. In this case, the inverted-U shaped relationship between openness and innovation would suggest that initial positive relationship turns into a negative when the limit of absorptive capacity is reached (Radicic and Pugh Citation2017). Second, some innovative ideas might not be fully exploited because they come at the wrong time (‘the timing problem’). Third, ‘the attention allocation problem’ might occur, in which case managers are struggling to dedicate enough time and effort to too many innovative ideas, or in the case of openness, too many sources of external knowledge or too many cooperative partners (Kobarg, Strumpf-Wollersheim, and Welpe Citation2019; Radicic et al. Citation2019).

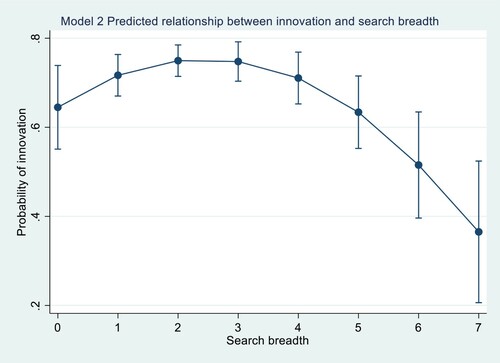

Concerning complex innovators that introduce both types of innovation, the problem of over-search might arise at a higher turning point in case of complex innovators relative to single innovators (Amara and Landry Citation2005). To check for potential non-linear effects of openness, models presented in are estimated with added squared terms of the variables of interest. These results are shown in . Looking at Model 1 that includes squared terms, the results show that search depth has a U-shaped effect on the introduction of single process innovation relative to single product innovation. This relationship, shown in , reveals that the turning point occurs when the intensity of knowledge search depth reaches two. This finding implies that single process innovators, when the intensity of knowledge search is low, do not benefit from openness relative to single product innovators. But when the intensity of knowledge usage increases beyond a relatively low level, these innovators exert more benefit from search depth than single product innovators.

Figure 1. Predicted relationship between innovation and search depth in pure process innovators relative to pure product innovators.

Table 3. Logit estimates of models from with added squared terms of variables of interest.

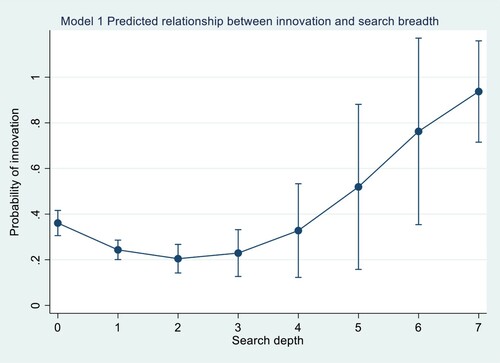

Another non-linear effect of openness is found concerning search breadth in Model 2. In this model, the effect of search breadth has an inverted U-shape, suggesting that over-search in the case of complex innovators occurs when the number of knowledge sources is above three (see ).

6. Discussion and conclusion

This study explores the impact of inbound and coupled open innovation strategies in two groups of SMEs, those that are complex innovators that engage in product and process innovations, and those that are single innovators that focus solely on product or process innovations. Overall, empirical evidence reveals rather heterogenous effects depending on the type of open innovations. Firstly, when comparing single innovators, our results show that the only differentiating effect is found with respect to search depth, that is more effective in single product innovators than in single process innovators. Secondly, when comparing complex innovators with single innovators, we found that complex innovators are more effective in utilising the breadth of cooperative partners. Therefore, coupled OI, proxied by cooperation breadth (Freitas et al. Citation2011) increases the probability of complex innovations relative to single innovations. Thirdly, complex innovators are more effective in exploiting search depth relative to simple process innovators.

This study provides several contributions to the existing literature: first, it distinguishes between single and complex innovators. This distinction has revealed some differences with respect to the relative effectiveness of inbound and coupled OI strategies in promoting innovation in SMEs. Second, the study encompasses two OI strategies, which are often investigated separately. In this respect, results show similarities and differences between the effectiveness of inbound and coupled OI strategies. Third, this is among first studies to report relative effects of OI strategies by comparing pure product innovators with pure process innovators, complex innovators with pure product innovations and with pure process innovators.

Concerning practical implications, this study points out the need for categorising firms into those that are product or process-oriented (Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll Citation2021) and those that engage in both types of innovation (Le Bas and Poussing Citation2014; Radicic Citation2020). Comparing product and process-oriented SMEs, the former is more effective in utilising the depth of search strategy, while other types of OI exhibit no differentiating effects. We extend the analysis and discover that the depth of search has a non-linear effect. More precisely, process-oriented SMEs do not benefit from search depth when it is at a relatively lower level, but do benefit after a certain threshold is reached.

When focusing on complex innovators in comparison to pure innovators, formal linkages through cooperation for innovation are more effectively used in stimulating product and process innovations. For managers, this study suggests that complex innovation activities require an effective use of coupled OI strategies through cooperation for innovation as a formal linkage with external partners. Moreover, our further analysis of potential non-linear effects reveals no such effects with respect to cooperation breadth, but we do find that search breadth has a curvilinear effect. This finding implies that complex innovators, relative to pure process innovators, might suffer from over-search of external knowledge sources.

Our study has certain limitations that can serve as suggestion for future research. First, we focus on a single country – Germany, that belongs to a group of European innovation leader countries. It would be insightful to explore how effective complex and simple SME innovators are in exploiting inbound and coupled open innovation strategies in less innovative countries. Second, SMEs are a heterogenous category of firms (Parrilli and Radicic Citation2021), and thus they might differ in the use of open innovation in promoting product and process innovations. Therefore, a firm size analysis by distinguishing micro, small and medium firms would reveal whether innovation patterns revealed in this study are homogenous across these categories. Finally, our study focuses on manufacturing SMEs. Behavioural characteristics of SMEs in service sectors could lead to different patterns of open innovation effectiveness in these firms (Radicic Citation2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dragana Radicic

Dragana Radicic is associate professor in economics at Lincoln International Business School. Her research interests include open innovation, R&D and innovation policy, environmental innovation and internationalisation of innovation.

Fadi Alkaraan

Fadi Alkaraan is senior lecturer in accounting and finance. at Lincoln International Business School. His research interests include corporate governance, strategic investment decision-making, corporate Social Responsibility and open innovation.

Notes

2 As our dataset does not include measures for outbound open innovation, our focus is on inbound and coupled open innovation strategies.

3 For the sake of brevity, results are not reported but available upon request.

1 We use the terms ‘single’ and ‘pure’ innovators interchangeably. While Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll (Citation2021) refer to those firms as pure innovators, Le Bas and Poussing (Citation2014) and Radicic (Citation2020) refer to them as single innovators.

2 As our dataset does not include measures for outbound open innovation, our focus is on inbound and coupled open innovation strategies.

3 For the sake of brevity, results are not reported but available upon request.

References

- Abreu, M., V. Grinevich, M. Kitson, and M. Savona. 2010. “Policies to Enhance the ‘Hidden Innovation’ in Services: Evidence and Lessons from the UK.” The Service Industries Journal 30 (1): 99–118.

- Amara, N., and R. Landry. 2005. “Sources of Information as Determinants of Novelty of Innovation in Manufacturing Firms: Evidence from the 1999 Statistics Canada Innovation Survey.” Technovation 25 (3): 245–259.

- Ayllón, S., and D. Radicic. 2019. “Product Innovation, Process Innovation and Export Propensity: Persistence, Complementarities and Feedback Effects in Spanish Firms.” Applied Economics 51 (3): 3650–3664.

- Barney, J. B. 1996. “The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm.” Organization Science 7 (5): 469–592.

- Cainelli, G., V. De Marchi, and R. Grandinetti. 2020. “Do Knowledge-Intensive Business Services Innovate Differently?” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 29 (1): 48–65.

- Chesbrough, H. 2003. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Chesbrough, H. W. 2006. “Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology.” Academy of Management Perspectives 20: 86–88.

- Chesbrough, H., and M. Bogers. 2014. “Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an Emerging Paradigm for Understanding Innovation.” In New Frontiers in Open Innovation, edited by H. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, and J. West, 3–28. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chesbrough, H., and A. K. Crowther. 2006. “Beyond High-Tech: Early Adopters of Open Innovation in Other Industries.” R&D Management 36 (3): 229–236.

- Chesbrough, H., W. Vanhaverbeke, and J. West. 2006. Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm. London: Oxford University Press.

- Cohen, W., and D. Levinthal. 1990. “Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation.” Administrative Science Quarterly 35 (1): 128–152.

- Cricelli, L., M. Greco, and M. Grimaldi. 2016. “Assessing the Open Innovation Trends by Means of the Eurostat Community Innovation Survey.” International Journal of Innovation Management 20 (3): 1650039.

- Criscuolo, P., K. Laursen, T. Reichstein, and A. Salter. 2018. “Winning Combinations: Search Strategis and Innovativeness in the UK.” Industry and Innovation 25 (2): 115–143.

- D’Angelo, A., and A. Baroncelli. 2020. “An Investigation Over Inbound Open Innovation in SMEs: Insights from an Italian Manufacturing Sample.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 32 (5): 542–560.

- Dyer, J. H., and H. Singh. 1998. “The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage.” Academy of Management Review 23 (4): 660–679.

- Freitas, I. M. B., T. H. Clausen, R. Fontana, and B. Verspagen. 2011. “Formal and Informal External Linkages and Firms’ Innovative Strategies.” A Cross-Country Comparison. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 21: 91–119.

- Gassmann, O., and E. Enkel. 2004. “Towards a Theory of Open Innovation: Three Core Process Archetypes.” Proceedings of the R&D management conference (RADMA), 6 July 2004, Lisbon, Portugal.

- Greco, M., M. Grimaldi, and L. Cricelli. 2016. “An Analysis of the Open Innovation Effect on Firm Performance.” European Management Journal 34 (5): 501–516.

- Hervas-Oliver, J. L., F. Sempere-Ripoll, and C. Boronat-Moll. 2021. “Technological Innovation Typologies and Open Innovation in SMEs: Beyond Internal and External Sources of Knowledge.” Technological Forecasting & Social Change 162: 120338.

- Hervas-Oliver, J. L., F. Sempere-Ripoll, C. Boronat-Moll, and S. Estelles-Miguel. 2020. “SME Open Innovation for Process Development: Understanding Process-Dedicated External Knowledge Sourcing.” Journal of Small Business Management 58 (2): 409–445.

- Kobarg, S., J. Strumpf-Wollersheim, and I. M. Welpe. 2019. “More is not Always Better: Effects of Collaboration Breadth and Depth on Radical and Incremental Innovation Performance at the Project Level.” Research Policy 48 (1): 1–10.

- Kock, F., A. Berbekova, and G. Assaf. 2021. “Understanding and Managing the Threat of Common Method Bias: Detection, Prevention and Control.” Tourism Management 86: 104330.

- Koput, K. W. 1997. “A Chaotic Model of Innovative Search: Some Answers, Many Questions.” Organization Science 8 (5): 528–542.

- Laursen, K., and A. Salter. 2006. “Open for Innovation: The Role of Openness in Explaining Innovation Performance among UK Manufacturing Firms.” Strategic Management Journal 27 (2): 131–150.

- Laursen, K., and A. Salter. 2014. “The Paradox of Openness: Appropriability, External Search and Collaboration.” Research Policy 31 (8): 362–373.

- Le Bas, C., and N. Poussing. 2014. “Are Complex Innovations More Persistent Than Single Innovators? An Empirical Analysis of Innovation Persistence Drivers.” International Journal of Innovation Management 18 (1): 1450008.

- Leiponen, A., and J. Byma. 2009. “If You Cannot Block, You Better Run: Small Firms, Cooperative Innovation, and Appropriation Strategies.” Research Policy 38 (9): 1478–1488.

- Love, J. H., S. Roper, and J. R. Bryson. 2011. “Openness, Knowledge, Innovation and Growth in UK Business Services.” Research Policy 40 (10): 1438–1452.

- Moilanen, M., S. Østbye, and K. Woll. 2014. “Non-R&D SMEs: External Knowledge, Absorptive Capacity and Product Innovation.” Small Business Economics 43: 447–462.

- Parida, V., M. Westerberg, and J. Frishammar. 2012. “Inbound Open Innovation Activities in High Tech SMEs: The Impact on Innovation Performance.” Journal of Small Business Management 50 (2): 283–309.

- Parrilli, D., and D. Radicic. 2021. “STI and DUI Innovation Modes in Micro, Small, Medium and Large-Sized Firms: Distinctive Patterns Across Europe and the US.” European Planning Studies 29 (2): 346–368.

- Radicic, D. 2020. “Breadth of External Knowledge Search in Service Sectors.” Business Process Management Journal 27 (1): 230–252.

- Radicic, D., D. Douglas, G. Pugh, and I. Jackson. 2019. “Cooperation for Innovation and Its Impact on Technological and non-Technological Innovations: Empirical Evidence for European SMEs in Traditional Manufacturing Industries.” International Journal of Innovation Management 23 (5): 1950046.

- Radicic, D., and G. Pugh. 2017. “Performance Effects of External Search Strategies in European Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises.” Journal of Small Business Management 55 (S1): 76–114.

- Reichstein, T., and A. Salter. 2006. “Investigating the Sources of Process Innovation among UK Manufacturing Firms.” Industrial and Corporate Change 15 (4): 653–682.

- Silva, M. J. M., J. Simões, G. Sousa, J. Moreira, and E. W. Mainardes. 2014. “Determinants of Innovation Capacity: Empirical Evidence from Services Firms.” Innovation: Organization & Management 16 (3): 404–416.

- Sun, Y., J. Liu, and Y. Ding. 2020. “Analysis of the Relationship Between Open Innovation, Knowledge Management Capability and Dual Innovation.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 32 (1): 15–28.

- Terjesen, S., and P. C. Patel. 2017. “In Search of Process Innovations: The Role of Search Depth, Search Breadth, and the Industry Environment.” Journal of Management 43 (5): 1421–1446.

- Tsinopoulos, C., J. Yan, and C. P. Sousa. 2019. “Abandoning Innovation Activities and Performance: The Moderating Role of Openness.” Research Policy 48: 1399–1411.

- Van de Vrande, V., J. P. J. de Jong, W. Vanhaverbeke, and M. de Rochemont. 2009. “Open Innovation in SMEs: Trends.” Motives and Management Challenges. Technovation 29 (6–7): 423–437.

- Van de Vrande, V., W. Vanhaverbeke, and O. Gassmann. 2010. “Broadening the Scope of Open Innovation: Past Research, Current State and Future Directions.” International Journal of Technology Management 52 (3–4): 221–235.

- Volberda, H. W., N. J. Foss, and M. A. Lyles. 2010. “Absorbing the Concept of Absorptive Capacity: How to Realize its Potential in the Organization Field.” Organization Science 21 (4): 931–951.

- West, J., and M. Bogers. 2014. “Leveraging External Sources of Innovation: A Review of Research on Open Innovation.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 31 (4): 814–831.

- Zhao, J. 2021. “The Relationship Between Coupling Open Innovation and Innovation Performance: The Moderating Effect of Platform Openness.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, doi:10.1080/09537325.2021.1970129.